Lack of rigorous negative control

The random collisions of two halves of reporter protein fragments are the main source of BiFC background signals, as well as other PCA-based methods. Thus, in a high-throughput BiFC scan, the negative control is important to non-specific signal removal and subsequent candidate validation. Unlike the loss-of-function screens that the paired negative controls are well defined and integrated in the whole genetic library, such as gRNA or shRNA library, the BiFC negative control is more flexible and very study-dependent. Even for individual BiFC, a rigorous control is not always available, not to speak of a genome-wide BiFC screening. Though sometimes the gain-of function or overexpression screening shares the same hORFeome library with BiFC screening, the control using function-free and fluorescent proteins are not compatible with BiFC. To address this point, four types of negative controls are widely recruited in the BiFC screening: (a) N- and C-terminal FP fragments without fusion to the POI; (b) N-terminal FP fragment fused to POI with the unfused C-terminal FP fragment; (c) C-terminal FP fragment fused to POI with the unfused N-terminal FP fragment. (d) One FP fragment fused to POI alone. As reported, at least one, or up to 3 of the above mentioned controls are used in BiFC screenings (Xia et al., 2018; Yue et al., 2017). Unfortunately, all of these controls fall into the inappropriate controls (Kudla and Bock, 2016).

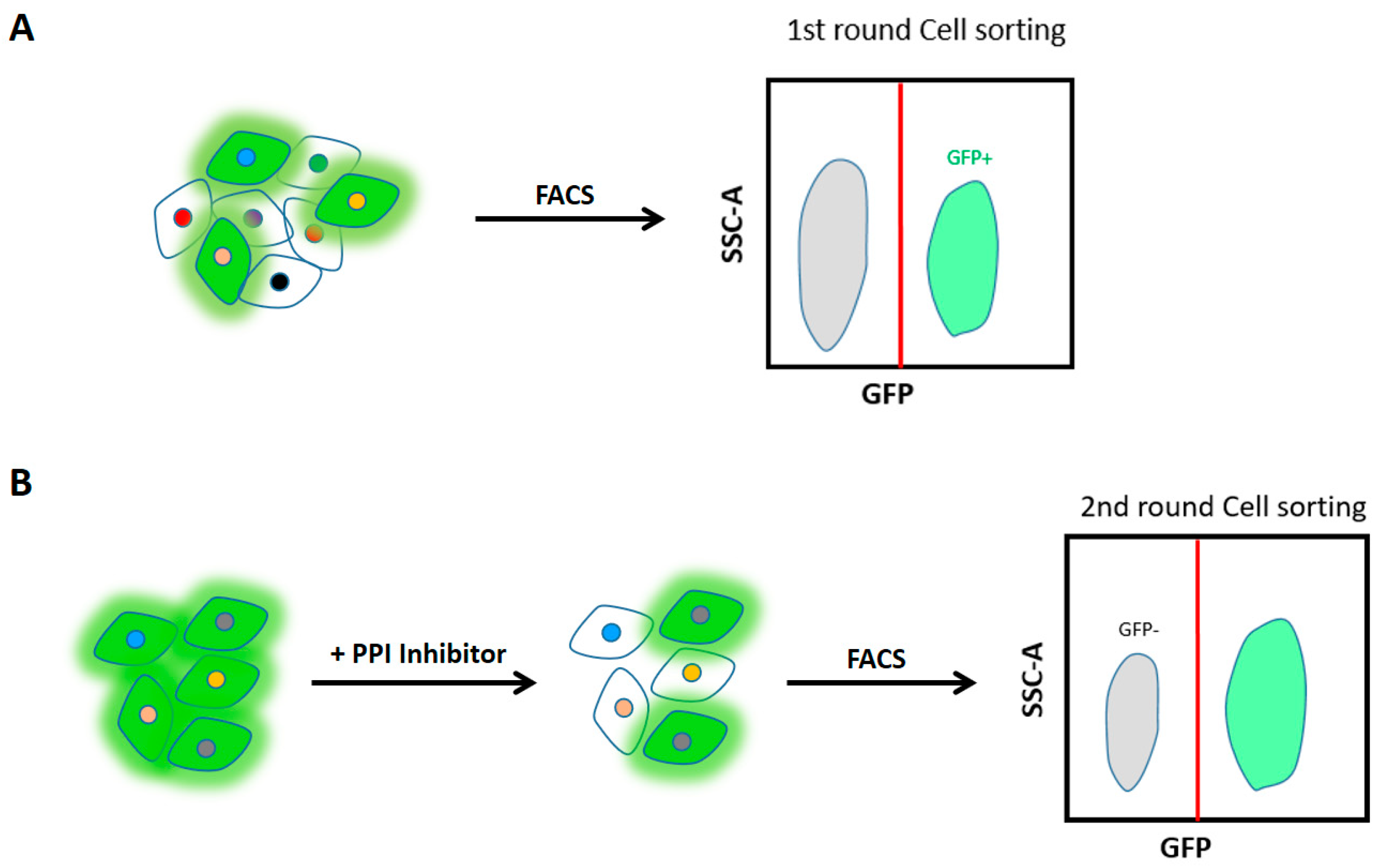

The splitFAST approach could constitute a promising alternative to FP-based BiFC

(Tebo and Gautier, 2019). Indeed, splitFAST is reversible and can therefore be used for selecting interactions that will be specifically affected by a given inhibitor to test. In contrast to FP-based BiFC, where the inhibitor has to be mixed with the fusion proteins for a long time incubation before BiFC signal detection, splitFAST allows testing the inhibitor directly on the fluorescent complexes in real time (

Figure 3). This strategy could be suitable for a conventional genome-wide PPI screening (e.g. to know the potential range of action of a therapeutic molecule), and could also be amenable to conduct a TF functional domain screening with a known corresponding inhibitor, as well as drug screening for fitness genes within potential PPIs in human cell lines. Finally, given the reversibility of splitFAST, it allows having access to the PPI dynamics, a key molecular parameter that conventional FP-based BiFC could not approach.

Multicolor BiFC screening

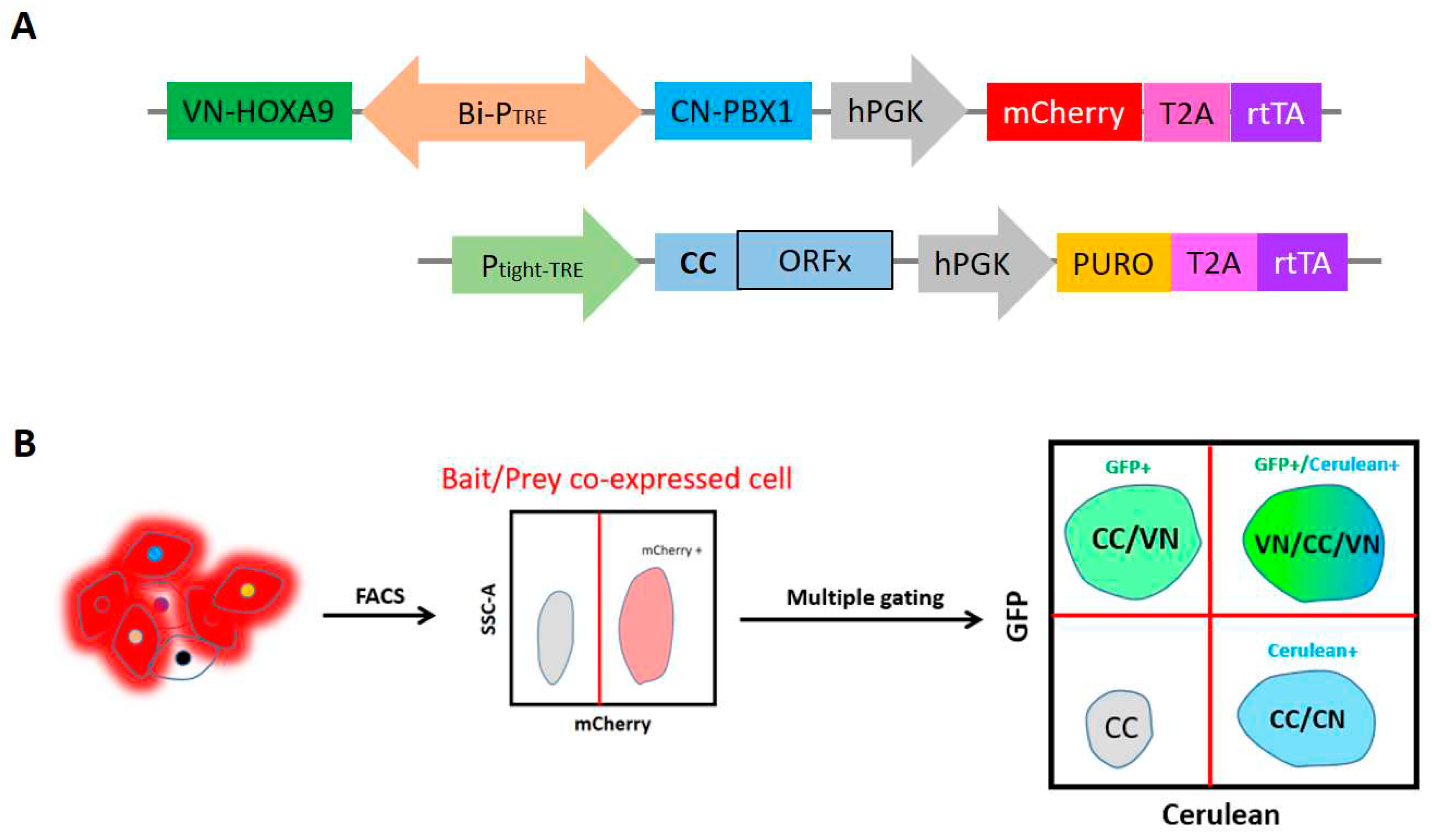

Growing concern regarding the rise in protein complex-specific interactome, the split-BioID was reported as a promising and powerful method to investigate the proximal binding partners of a given binary protein complex, as well as our new developed BibID approach. Likewise, multicolor BiFC analysis provides an effective assay to compare the subcellular distributions of protein complexes formed with different binding partners. Furthermore, this method can be regarded as one single-scale method to verify the binay protein complex-specific cofactors. Although its utility in high-throughput manner is theoretically feasible, multicolor BiFC assay applied for high-throughput screen is as yet unpublished. Owing to the availability of Bi-PTRE, two baits can be easily cloned into the same plasmid, keeping the same system complexity as single bait screening. Here I propose a strategy of high-throughput multicolor BiFC screening, which will break the limit of conventional single target BiFC screening, empowering it with a protein complex-compatible screening, in addition to single bait protein screening (

Figure 4).

In principle, split-FP fragments will be used and derived from two different fluorophores, mVenus and mCerulean, with distinct spectra. Either VC155 or CC155 could achieve mVenus-like BiFC with VN173 fragment

(Jia et al., 2021). In addition, the CC155 fragment can complement with the CN173 for making mCerulean-like BiFC. This property allows visualizing two different PPIs simultaneously by doing mVenus- and mCerulean-like BiFC with three fusion proteins. The CN173/CC155/VN173 has proven to be the best combination for multicolor BiFC

(Shyu et al., 2006). Based on these versatile FP fragments, VN-HOXA9/CN-PBX1 bait proteins were used in plasmid construction (

Figure 4A), and the rationale of high-throughput multicolor BiFC was detailed in

Figure 4B. Depending on the needs, the double baits are not necessary to be coexpressed. This system can easily be used as conventional single-bait BiFC screening, if keeping one of Bi-PTRE flanks empty. Collectively, proposed high-throughput multicolor BiFC screening enables two interactions to be examined simultaneously, facilitating the detection of binary protein complex-specific partners, as a cost-effective and time-saving method.

The tag effect

There are two main concerns, when applying a tag-based method. One is the biotechniques used for tagged fusion protein introduced into a live context, such as the classical methods, including transfection, transformation or virus-mediated transduction, and advanced approaches, for example, CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene tagging (Lackner et al., 2015). Though the side effect of tag was largely improved, especially the steric hindrance of interactions caused by overexpression of tagged bait protein, on the other hand, the tag per se, can result in non-native folding of fusion proteins and further influencing the stoichiometry of the complex.

However, the split-FP fragment as tags of tested proteins, is the basis of BiFC principle. The tag is an integral part of the BiFC system, unlike the antibody-based methods such AP-MS or Co-IP, in which alternative tag-free procedure can be performed via endogenous protein-specific antibody. Given that large and bulky fragments impair BiFC fragment solubility and folding, consequently leading to high background signals (Y and Cd, 2010), several efforts have been addressed on the tag minimization, for instance, the micro-tagging system based on tripartite split-GFP (Cabantous et al., 2013).

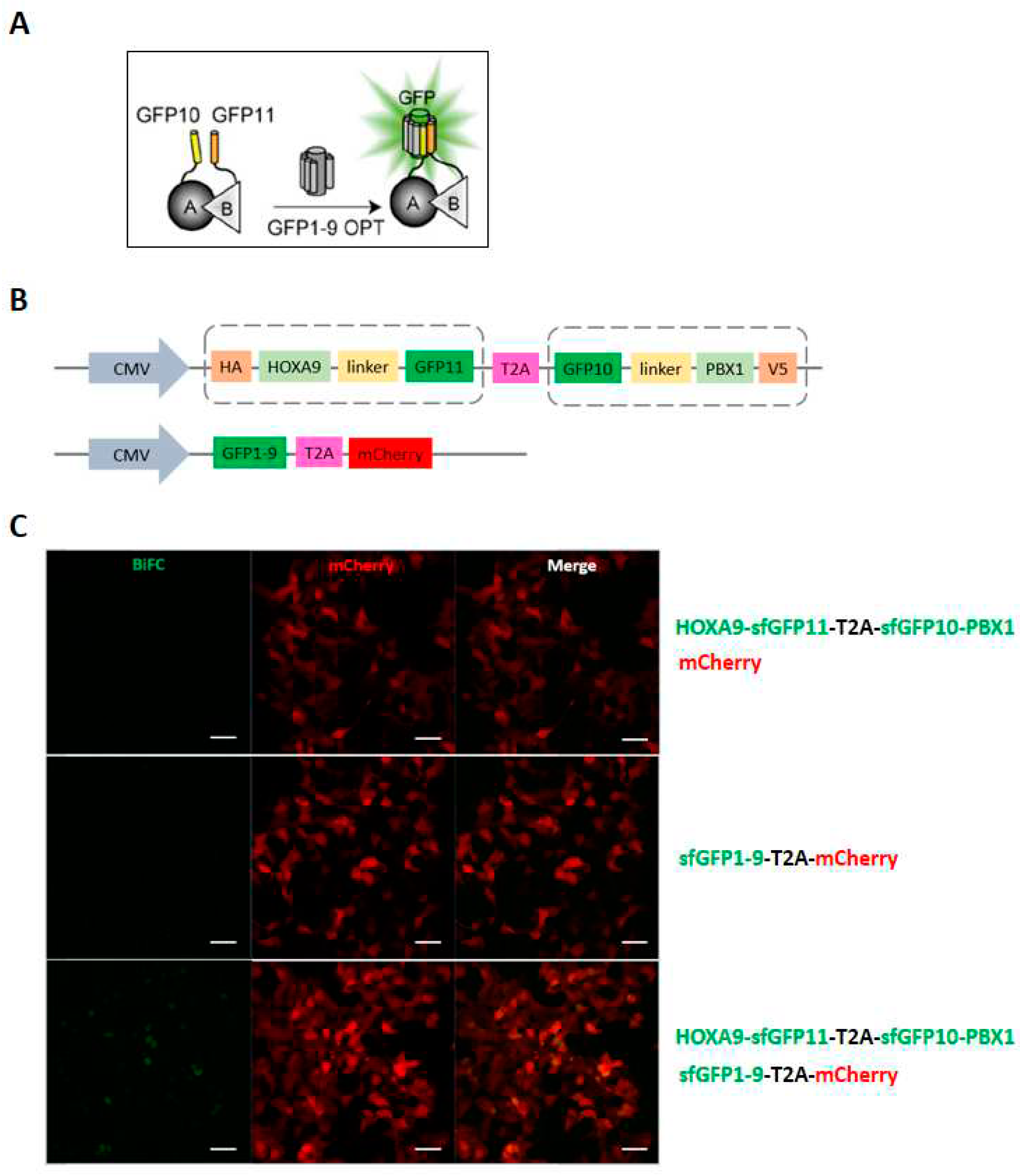

Concerning our BiFC system, generic and large fragments were used in a large-scale screen, which is potentially aggregation-prone and of high backgrounds from self-assembly. I should still emphasize here that (i) only 1-2% of cells were fluorescent in the HOX screen and (ii) different partners were found with the different HOX proteins, thus making the BiFC background of low incidence for capturing specific signals. In any case, to know whether other BiFC systems could be performed with a minimum background, I tested a tripartite split-GFP system, also known as TriFC (

Tripartite

Fluorescence

Complementation) assay (

Figure 5A). As showcase, I generated sfGFP10-HOXA9 and sfGFP11-PBX1 functional fusions in a single pcdna3 plasmid, with a ready-to-use detector plasmid containing sfGFP1-9 fragment fused to mCherry reporter (

Figure 5B). The test was performed in HEK cells by transfection. Each plasmid was individually transfected to check the background signals. Preliminary results showed that the TriFC worked properly in a two-plasmid transfection system, comparable to our routine 3-plasmid system. The HOXA9/PBX1 interaction localized in the nucleus as expected (

Figure 5C). Only requiring attention is that the reconstituted GFP signal is seemingly much weaker than CC/VN refolded fluorescence, which needs a further evaluation.

Furtherly, upon this verified advanced TriFC method, I present here its applicability in a high-throughput system. There is no difference for the tagged bait protein and prey library preparation (with a small GFP tag in both cases). One more step should be considered is how to introduce the big GFP1-9 detector fragment into the cells. On this point, making a GFP1-9 stable cell line will be best to subsequently be used to generate GFP10 or GFP11-tagged prey cell libraries. The resulting endogenous GFP1-9-expressed prey cell library will function similarly as that used in our previous Cell-PCA. Hopefully, this micro-tagged TriFC screening could minimize the unexpected protein interference and aggregation.

Convoluted polyclonal prey cell library

The heterogeneity of cells is mostly resulting from genome instability and cellular division during culturing and passaging, especially in the case of immortalized model cell lines. As such, the cell-to-cell variability is of wide concern for proteomics. However, the cell-based PPI studies have commonly been performed in bulk, with substantial materials that can largely compensate this intrinsic variance, obtaining a global and acceptable proteome profile. Since the emergence of high-throughput screening, the pooled cell library was frequently used in different screening-based approaches. The lentiviruses are frequently used to make the well-known one-ORF-per-Cell library. Due to the random lentiviral insertion of ORF, genetic interruption and insertional mutagenesis were often observed in stable cells. Moreover, the expression of integrated genes will depend on the transcriptional activity of the surrounding sequences at the integration site. Taken altogether, the random insertion will aggravate the library inner variance, which will further influence the screen performance.

Therefore, knock-in at the identical target genomic locus is highly demanded. Generally, there are two well-documented methods to introduce the target DNA sequence to a predefined genome site. First is the Flp-In system that involves introduction of a Flp Recombination Target (FRT) site into the genome of the mammalian cell line of choice (O’Gorman et al., 1991). Once the biotic-resistant Flp-In cell line is established, the subsequent generation of isogenic stable line is rapid and efficient. Consequently, this method was frequently used in function gene stable cell line generation. As the probability of obtaining stable integrants containing a single FRT site or multiple FRT sites, with subsequent chromosomal position effect, this method is as yet not reported to be used in high-throughput study. Second, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9)-based techniques have transformed our ability to genetically manipulate mammalian genomes. Knock-in method with Cas9 RNPs (Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoproteins) mediated homology directed repair template (HDRT) permits alteration of the endogenous sequence or insertion of an exogenous sequence at the target locus. More recently, a method for pooled knockin screens was developed which combines simultaneous delivery of a library of dsDNA HDRTs and Cas9 RNPs by electroporation. The HDRTs are integrated into a single locus (endogenous TCR-α locus), specified by the sgRNA to generate a T cell population expressing on average one insert per cell. The delivery of the library is followed by assays to evaluate the impact of each construct on T cells (Roth et al., 2020). This impactful attempt sheds light on the generation of a pooled and BiFC-compatible tagged prey cell library in means of a unique single integration site. The resulting pooled tagged ORF knock-in involves the same locus being targeted in every cell, however the identity of the genetic modification at this locus differs between the cells in the edited population.

After all, the future pooled prey cell library with identical ORF insert sites will largely decrease the side effects caused by the transcriptional activity of the surrounding sequences for the cell population harboring the same ORF. Given the same ORF flanking sequence, it will further improve the PCR efficiency and bias of target region amplification during the NGS library preparation process. Moreover, the less convoluted cell library will benefit the ORF representation throughout the BiFC screening. In addition, during the sequential gating procedure, the cells with less variance will generate more concentrated cell populations, which could further increase the precision of cell sorting.

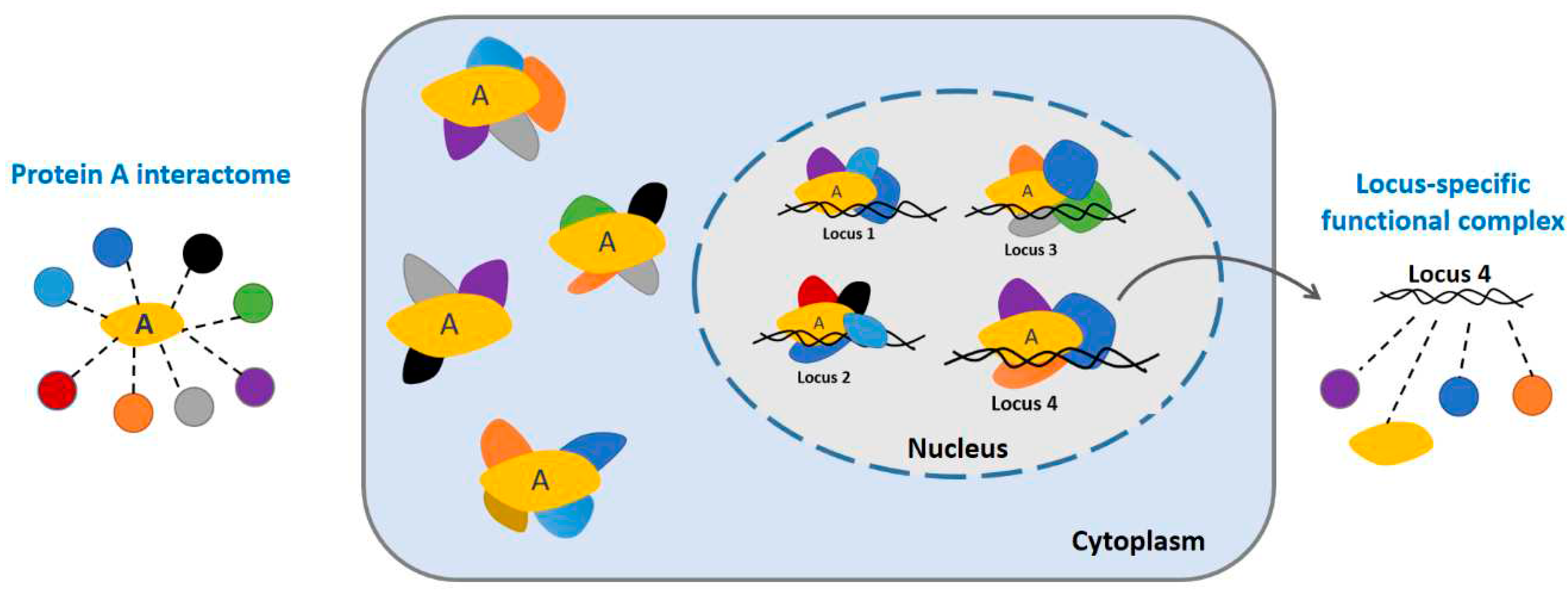

A bulk interactome investigation instead of single functional complex

Proteins participate in most cellular processes and fulfil most of their biological tasks in complexes through interaction with other proteins

(Alberts, 1998). Protein complexes that are composed of more than one component are found in many different classes of proteins. Like that cell is the fundamental structural and functional unit of all living organisms, the protein complex is the functional unit of cellular biological processes in which proteins involve (

Figure 7,

center). However, the PPI detection methods are generally performed in bulk manner, which measures only the global interactome of target proteins across a large population of input cells, resulting in a pool of potential interacting candidates regardless of the protein complex integrity (

Figure 7,

left). For example, BioID-like AP-MS investigates the whole complexome of target protein. In turn, our Cell-PCA generates a collection of possible binary PPIs. These methods do not allow the analysis of specific complexes but rather give an overview of all possible PPIs of a given protein, resulting in one of the most representative interactomes by smoothie-like PPI analysis.

Regarding the growing concern about the intra-tissue heterogeneity as well as the cell-to-cell variability in bulk analysis, single-cell omics gained widespread popularity since 2014 (Kharchenko et al., 2014; Picelli et al., 2014), along with more accessible protocols and lower sequencing costs. Following the first whole-transcriptome analysis of a single cell (Tang et al., 2009), more than 100 different single cell sequencing methods have been published (Wikipedia, 2021). These substantial advances have led to the transition from initial scRNA-seq to single-cell multi-omics, allowing multimodal measurements and integration of transcriptome, proteome, and spatial localization from the same cell. For example, the commercial 10X Genomics Visium solution combines whole transcriptome spatial analysis with immunofluorescence protein detection in the same tissue section, which empowers a deeper, more holistic understanding of tissue organization. Moreover, the classical large-scale genetic perturbation screens stand to benefit from single-cell sequencing. Recently, screens combining genetic perturbations with scRNA-seq readouts have emerged as promising and scalable alternatives over traditional screens, enabling direct readout of transcriptomic changes from the final fitness-responded cell population. As example, Maehr and colleagues combined single-cell RNA-seq with parallel CRISPR perturbations to comprehensively define the loss-of-function phenotype of those factors in definitive endoderm development (Genga et al., 2019). Innovatively, barcoded genome-scale ORF expression libraries were used by Mali lab, to systematically overexpress a pooled library of TFs in hPSCs, coupling scRNA-seq and fitness screen (Parekh et al., 2018). While other groups have demonstrated different scRNA-seq-based screens, notably, scRNA-seq based PPI screens have yet to be demonstrated.

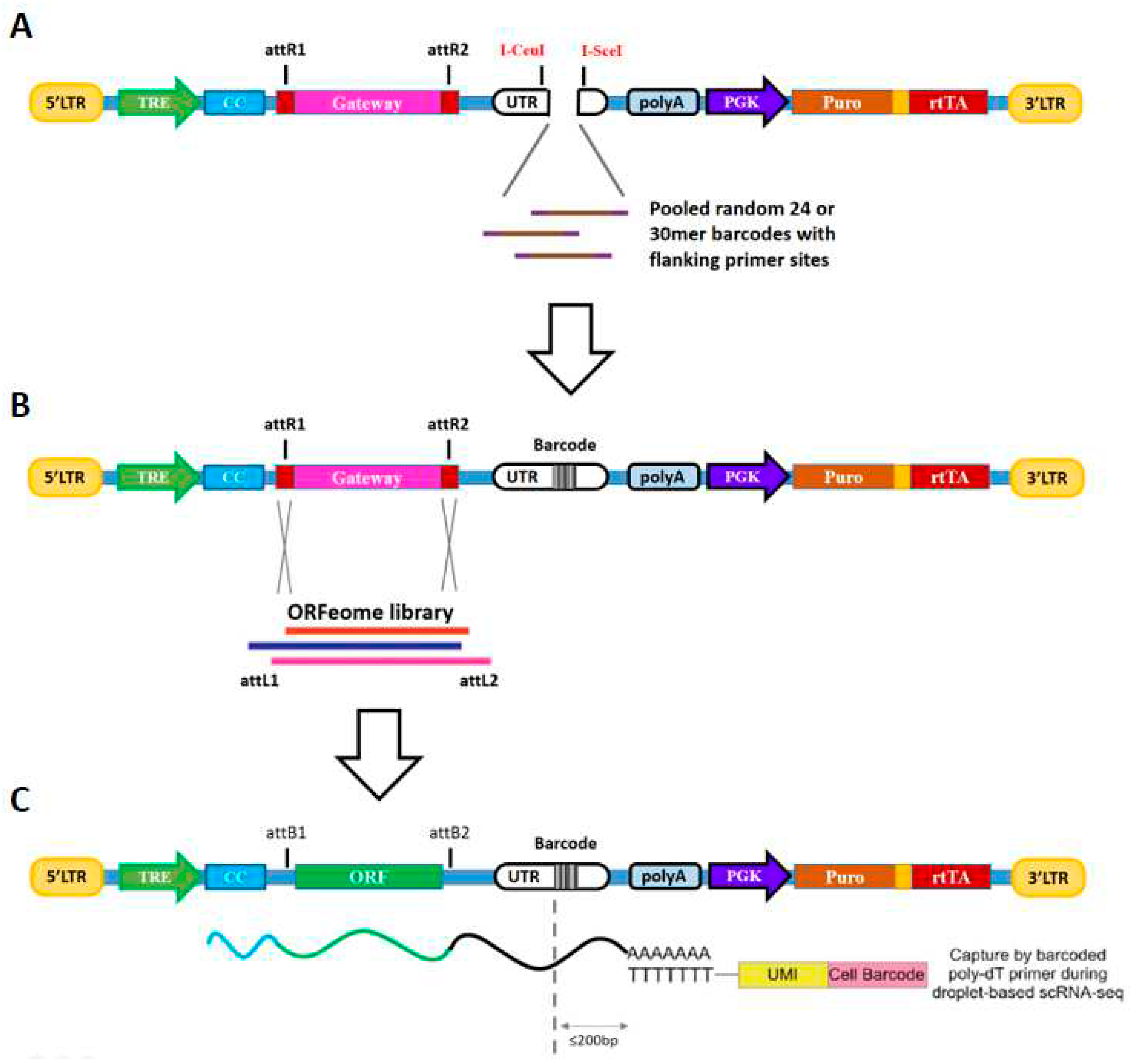

Thanks to the well-performed barcoded ORFeome library

(Parekh et al., 2018; Sack et al., 2018) and scRNA-seq (Chromium Single Cell 3’ library)

(Genga et al., 2019), herein I present a parallel scRNA-seq BiFC screening method, enabling pooled BiFC screens with single-cell transcriptome resolution (

Figure 8). In contrast to the genetic perturbation screens that pooled shRNAs and gRNAs themselves can serve as specific barcodes because they consist of uniquely identifiable DNA sequences, ORF sequences vary substantially in length, introducing bias during PCR recovery, as longer templates are recovered less efficiently by PCR. Thus, pairing ORFs uniquely with DNA BCs of uniform length will provide a marked improvement in screen fidelity, in which the BCs serve as the surrogate reporter to monitor ORF abundance. Moreover, this scRNA-seq-based BiFC screen method, at the time of deconvolution, is based on RNA-seq using a single cell 3’ gene expression library. The resulting CC-ORF was paired with a unique length barcode sequence located 200 bp upstream of the PolyA region (

Figure 8C). This yields a polyadenylated transcript bearing the barcode proximal to the 3’ end, facilitating efficient detection in scRNA-seq. Consequently, scRNA-seq based BiFC screening simultaneously assays both bait interacting ORF candidates and PPI-coupled cell-specific changes in transcriptome, more significantly, making a place for high-throughput PPI screening method in this new single-cell era.

As a long-term issue that pooled BiFC screening is restricted to apply in only cell lines or single-cell organisms, the multi-cell self-organized organoid is a potential model to be used in high-throughput BiFC screening. Recent progress in stem cell biology led to a strong revival of the organoid field. Organoid technology can therefore be used to model human organ development and various human pathologies ‘in a dish’’, reflecting key structural and functional properties of organs (Lancaster and Knoblich, 2014). To date, many genetic manipulations have already performed in organoids, such as transfection (Laperrousaz et al., 2018), transduction (Maru et al., 2016) and even CRISPR/Cas9 precision genome editing (Artegiani et al., 2020). In addition, single-cell analyses of matched organoids by FACS was also widely used in different studies (Fujimichi et al., 2019; Rosenbluth et al., 2020). Accordingly, the current achievements have shown that an organoid-based pooled BiFC screening is very promising to be conceived and carried out in the near future. This feasibility opens new perspectives for pooled BiFC screening, as well as high-throughput genetic screening and functional genomic applications, further giving precise and valuable insight into gene function and PPIs in a more human-like context.

Given the applicability of single-cell-based or/and organoid-based pooled PPI screening, it will permit measuring expression levels for each interacting candidate across a population of cells and allow studying new biological questions in which PPI-affected cell-specific changes in transcriptome. However, this single cell-based binary protein complex analysis is still far from a real functional protein complex. To fill this gap, a reverse-ChIP method, named CLASP (Cas9 locus-associated proteome), was reported to capture functionally relevant gene-specific regulators targeted to the gene locus of interest (Tsui et al., 2018). By using purified recombinant catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9)–guide RNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, CLASP does not require specialized cell lines and can be easily prepared with different guide RNAs to target multiple loci in any cell line or tissue. By fusing dCAS9 to PL enzyme, a new attempt was to fuse dCAS9 with BirA* to create a novel technology CASID, which was applied to analyze binding proteins in the direct vicinity of specific loci (Schmidtmann et al., 2016). Whereas dCAS9-based method enables a single genome locus-proximal proteome analysis, in which may include dozens of functional protein complexes instead of a single functional complex, it still provides insight into the real-time binding activities of these proteins at a specific DNA locus and uncovers the identities of these proteins simultaneously. However, one mentionable caveat is that the dCAS9-based method is designed to focus on only the nuclear protein activities depending on the DNA binding and its highly nucleus-restricted. Referring to the huge number of non-nucleus-localized protein complexes, a global non-compartment-specific detection method is needed, which enables a whole protein complexome analysis, like single transcript-based transcriptome analysis via RNA-seq.

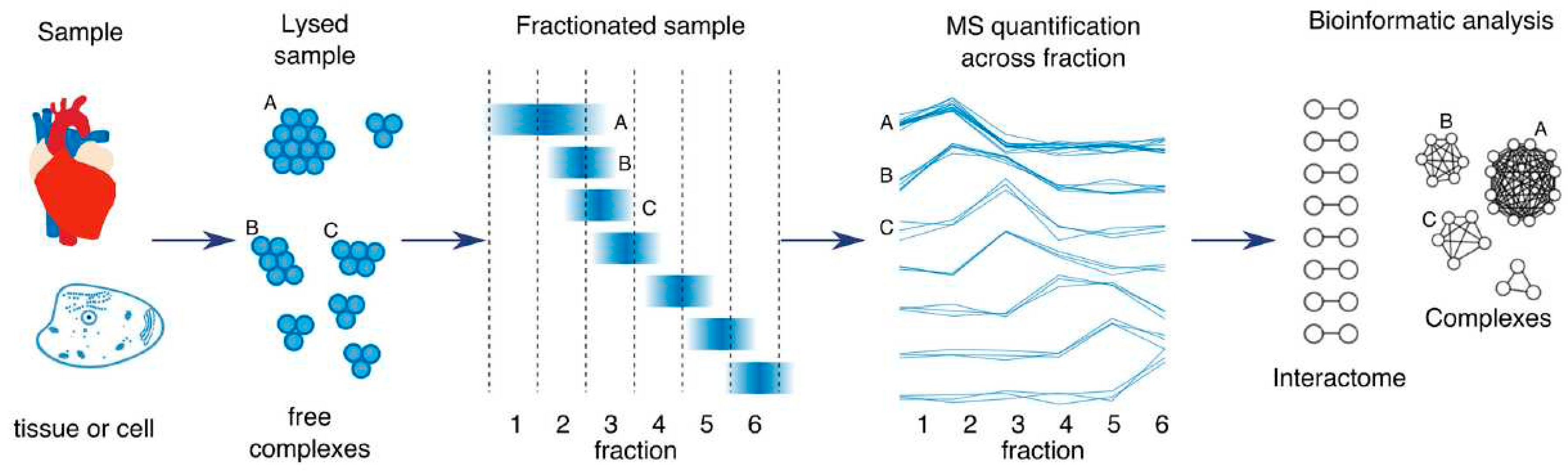

To close this gap, co-elution or co-fractionation (CoFrac) approaches are collectively a global approach used to simultaneously study the whole interactome

(Havugimana et al., 2012; Kristensen et al., 2012). They all rely on separation of protein complexes under native conditions, with the fact that proteins belonging to the same complex co-elute or migrate together during separation, showing the same migration profile (

Figure 9). As such, hundreds to thousands of protein complexes can be simultaneously and rapidly analyzed by co-elution in a single experiment, enabling the all-to-all protein analysis at single-protein-complex resolution. An added attraction of co-elution is, to date, that generated interactome does not rely on the genetic manipulation of cells or organisms, co-elution has thus been able to predict endogenous and unmanipulated protein complexes on a considerably large scale and in more physiologically relevant manner, as opposed to the results involving the tagged or overexpressed bait proteins. Nonetheless, one main drawback of co-elution that enslaves its popularity, is requirement of sophisticated bioinformatics analyses, facing million pairs of proteins quantified in a sample. However, co-elution is a powerful tool for next-generation interactomics, and it provides higher dimensional data information over existing high-throughput PPI screen methods. Looking forward, co-elution methods will progress toward increasing separation resolution and maximizing quantitation accuracy, along with miniaturization of sensitive MS measurement, and guide future single-cell interactomics.