Submitted:

10 October 2023

Posted:

11 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Commercial Diet and Tea Composition

2.2. General Experimental Procedures

2.3. Preparation of Experimental Feed

2.4. General Experimental Procedures

2.5. Measurement of Growth Performance Parameters

2.6. Tissue fixation and processing

2.7. The micronucleus assay (MN)

2.8. Statistical analysis

2.8.1. Growth Performance Parameters

2.8.2. Plant Metabolite Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of plant metabolites

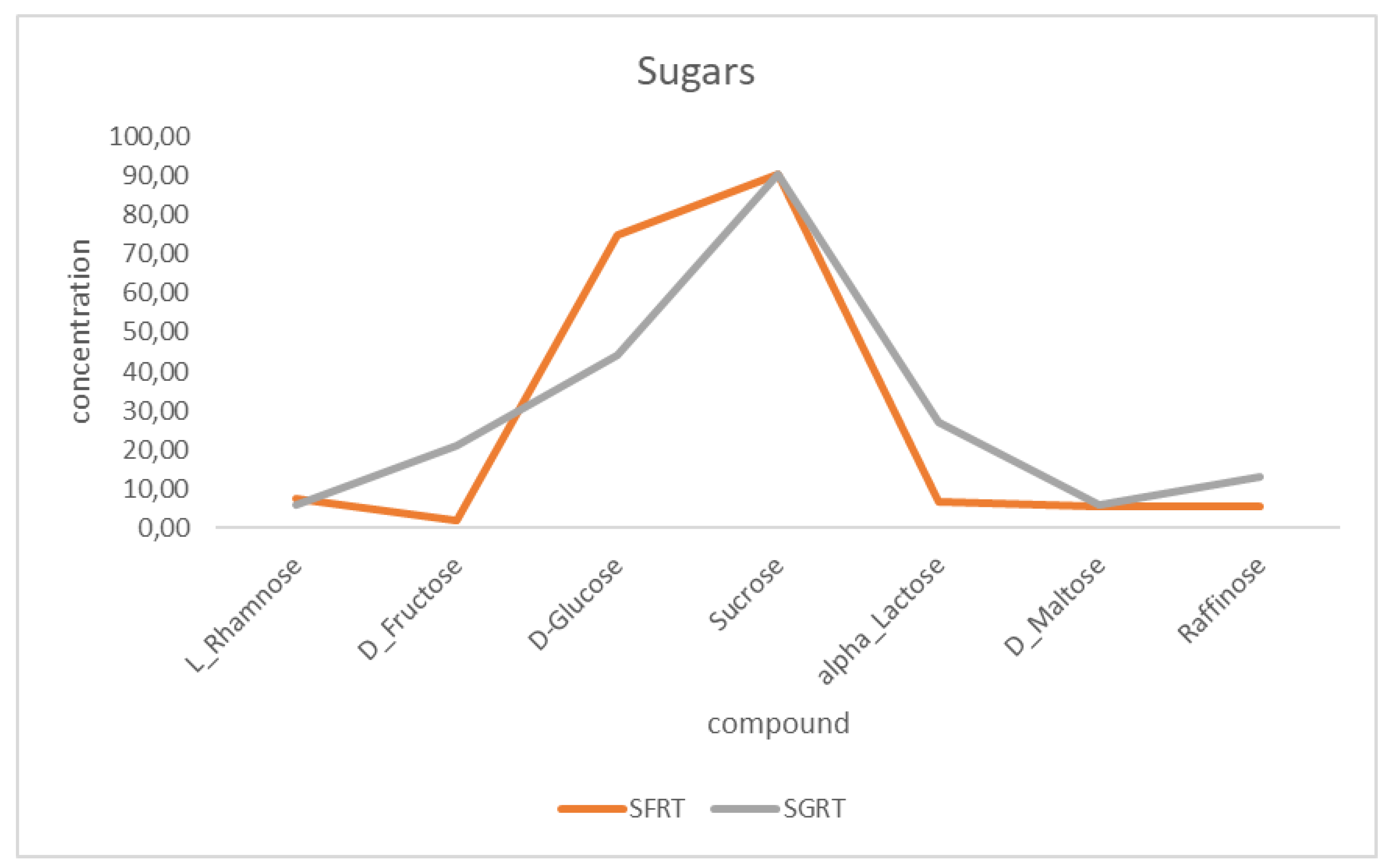

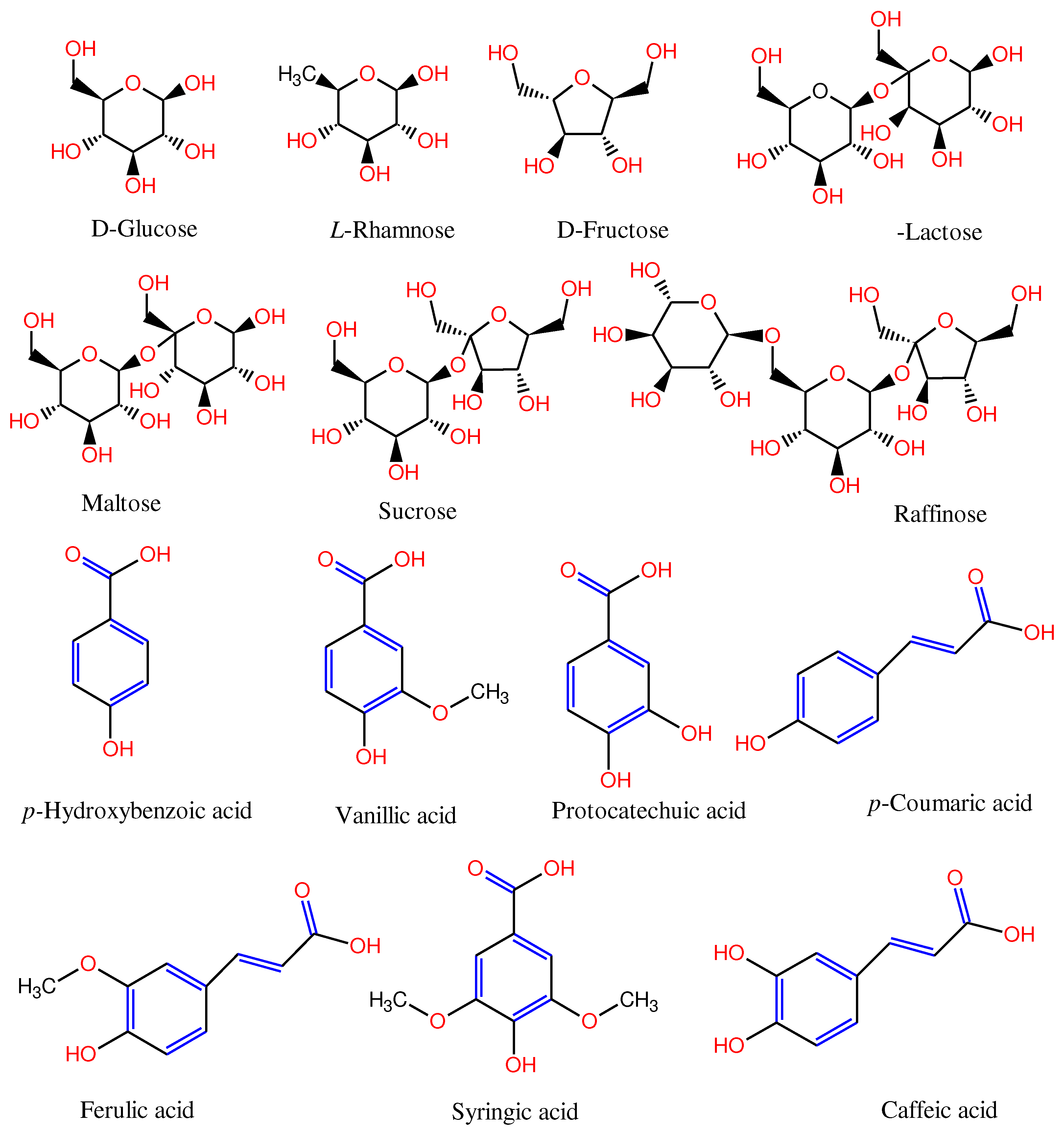

3.1.1. Sugars in GRT and FRT

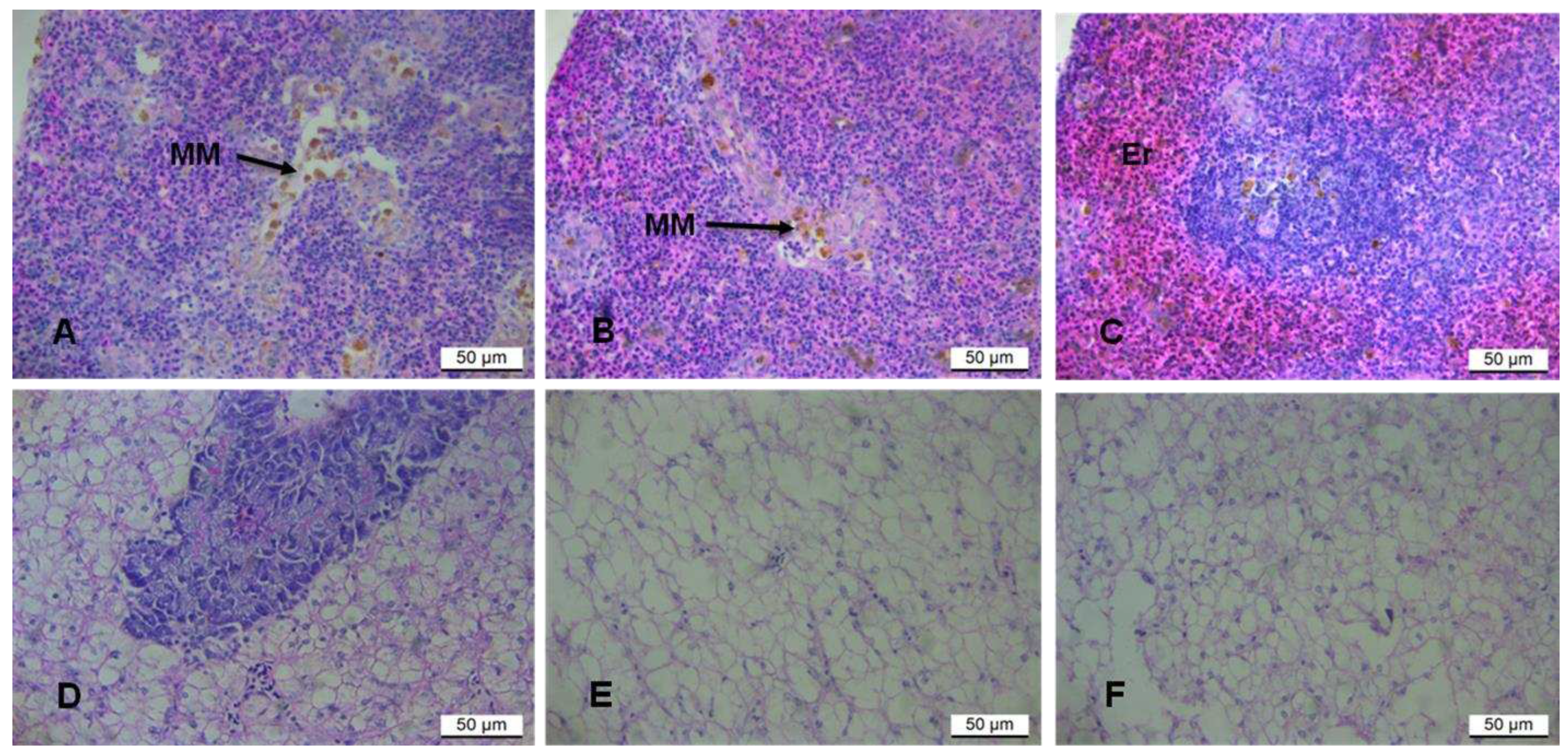

3.2.2. Liver and spleen histopathology

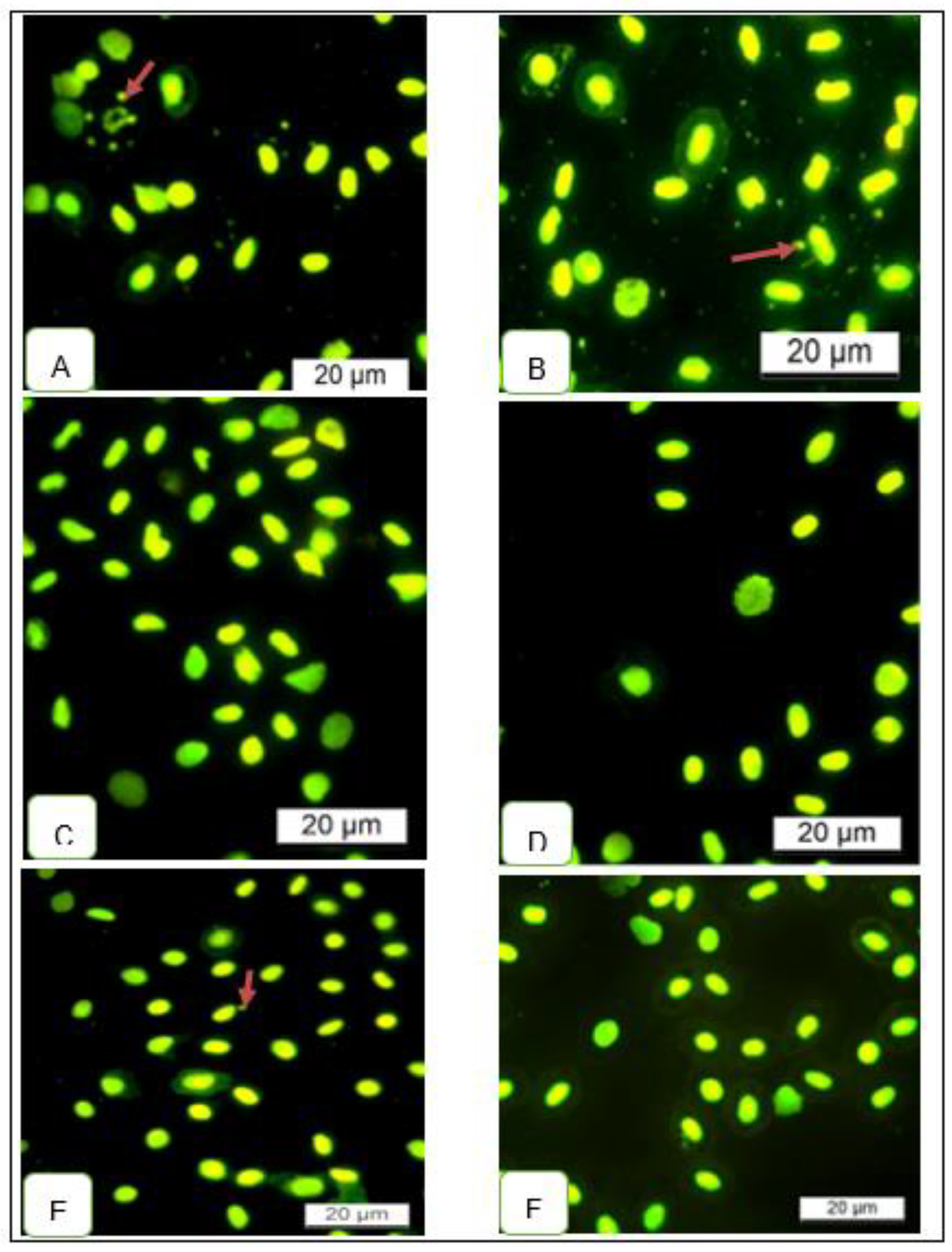

3.2.3. The Micronucleus (MN) Assay

4. Discussion

4.1. Larval fish growth response to FRT- and GRT extract-supplemented diets

4.2. Micronucleus (MN) assay

4.3. Histopathology

5. Conclusions

6. Ethics statement

References

- FAO, Cultured aquatic species information programme, Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2010.

- Fisheries, F., et al., FAO Yearbook: FAO Annuaire. Statistiques Des Pêches Et de L'aquaculture. Fishery and aquaculture statistics. 2009: FAO.

- Miao, W. and W. Wang, Trends of aquaculture production and trade: Carp, tilapia, and shrimp. Asian Fisheries Science, 2020. 33(S1): p. 1-10.

- Stankus, A., State of world aquaculture 2020 and regional reviews: FAO webinar series. FAO aquaculture newsletter, 2021(63): p. 17-18.

- Cai, J., et al., Improving the performance of tilapia farming under climate variation: perspective from bioeconomic modelling. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper, 2018(608): p. I-64.

- FAO, I., The state of food and agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction. FAO, Rome, 2019: p. 2-13.

- Kobayashi, M., et al., Fish to 2030: the role and opportunity for aquaculture. Aquaculture economics & management, 2015. 19(3): p. 282-300. [CrossRef]

- Pauly, D. and D. Zeller, Comments on FAOs state of world fisheries and aquaculture (SOFIA 2016). Marine Policy, 2017. 77: p. 176-181. [CrossRef]

- Department, A.O.o.t.U.N.F., The state of world fisheries and aquaculture. 2014: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Waltz, E., First genetically engineered salmon sold in Canada. Nature, 2017. 548(7666): p. 148-148. [CrossRef]

- New, M.B. and U.N. Wijkström, Use of fishmeal and fish oil in aquafeeds: further thoughts on the fishmeal trap. FAO Fisheries Circular (FAO), 2002.

- Naylor, R.L., et al., A 20-year retrospective review of global aquaculture. Nature, 2021. 591(7851): p. 551-563. [CrossRef]

- Makkar, H., G. Francis, and K. Becker, Bioactivity of phytochemicals in some lesser-known plants and their effects and potential applications in livestock and aquaculture production systems. animal, 2007. 1(9): p. 1371-1391. [CrossRef]

- Okocha, R.C., I.O. Olatoye, and O.B. Adedeji, Food safety impacts of antimicrobial use and their residues in aquaculture. Public health reviews, 2018. 39(1): p. 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.B. and C. Hancz, Application of phytochemicals as immunostimulant, antipathogenic and antistress agents in finfish culture. Reviews in Aquaculture, 2011. 3(3): p. 103-119. [CrossRef]

- Citarasu, T., Herbal biomedicines: a new opportunity for aquaculture industry. Aquaculture International, 2010. 18(3): p. 403-414. [CrossRef]

- Faggio, C., et al., Oral administration of Gum Arabic: effects on haematological parameters and oxidative stress markers in Mugil cephalus. 2015.

- Lee, K.W., H.S. Jeong, and S.H. Cho, Dietary inclusion effect of yacon, ginger, and blueberry on growth, body composition, and disease resistance of juvenile black rockfish (Sebastes schlegeli) against Vibrio anguillarum. Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 2020. 23: p. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Sutili, F.J., et al., Plant essential oils as fish diet additives: benefits on fish health and stability in feed. Reviews in Aquaculture, 2018. 10(3): p. 716-726. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., et al., The effect of partial replacement of fish meal by soy protein concentrate on growth performance, immune responses, gut morphology and intestinal inflammation for juvenile hybrid grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus♀× Epinephelus lanceolatus♂). Fish & shellfish immunology, 2020. 98: p. 619-631.

- Wang, W., et al., Application of immunostimulants in aquaculture: current knowledge and future perspectives. Aquaculture Research, 2017. 48(1): p. 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Z., et al., Effects of a natural antioxidant, polyphenol-rich rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) extract, on lipid stability of plant-derived omega-3 fatty-acid rich oil. LWT, 2018. 89: p. 210-216. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.B., P. Horn, and C. Hancz, Application of phytochemicals as growth-promoters and endocrine modulators in fish culture. Reviews in Aquaculture, 2014. 6(1): p. 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Rawling, M.D., D.L. Merrifield, and S.J. Davies, Preliminary assessment of dietary supplementation of Sangrovit® on red tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) growth performance and health. Aquaculture, 2009. 294(1-2): p. 118-122. [CrossRef]

- Shaban, A. and R.P. Sahu, Pumpkin seed oil: an alternative medicine. International journal of pharmacognosy and phytochemical research, 2017. 9(2).

- Shaban, H.H., S.L. Nassef, and G.S. Elhadidy, Utilization of garden cress seeds, flour, and tangerine peel powder to prepare a high-nutrient cake. Egyptian Journal of Agricultural Research, 2023. 101(1): p. 131-142.

- Arts, I.C. and P.C. Hollman, Polyphenols and disease risk in epidemiologic studies. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 2005. 81(1): p. 317S-325S.

- Li, X., et al., The effects of five types of tea solutions on epiboly process, neural and cardiovascular development, and locomotor capacity of zebrafish. Cell biology and toxicology, 2019. 35: p. 205-217. [CrossRef]

- Musial, C., A. Kuban-Jankowska, and M. Gorska-Ponikowska, Beneficial properties of green tea catechins. International journal of molecular sciences, 2020. 21(5): p. 1744. [CrossRef]

- Koch, W., W. Kukula-Koch, and Ł. Komsta, Black tea samples origin discrimination using analytical investigations of secondary metabolites, antiradical scavenging activity and chemometric approach. Molecules, 2018. 23(3): p. 513.

- Chandrasekara, A. and F. Shahidi, Herbal beverages: Bioactive compounds and their role in disease risk reduction-A review. Journal of traditional and complementary medicine, 2018. 8(4): p. 451-458. [CrossRef]

- Joubert, E. and D. de Beer, Rooibos (Aspalathus linearis) beyond the farm gate: From herbal tea to potential phytopharmaceutical. South African Journal of Botany, 2011. 77(4): p. 869-886. [CrossRef]

- Joubert, E., et al., South African herbal teas: Aspalathus linearis, Cyclopia spp. and Athrixia phylicoides—A review. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 2008. 119(3): p. 376-412. [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, B.-E., B.v. Oudtshoorn, and N. Gericke, Medicinal Plants of South Africa. 1997: Briza.

- Joubert, E., et al., Effect of species variation and processing on phenolic composition and in vitro antioxidant activity of aqueous extracts of Cyclopia spp.(honeybush tea). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2008. 56(3): p. 954-963.

- Shimamura, N., et al., Phytoestrogens from Aspalathus linearis. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 2006. 29(6): p. 1271-1274. [CrossRef]

- Bramati, L., et al., Quantitative characterization of flavonoid compounds in rooibos tea (Aspalathus linearis) by LC− UV/DAD. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 2002. 50(20): p. 5513-5519. [CrossRef]

- Joubert, E., HPLC quantification of the dihydrochalcones, aspalathin and nothofagin in rooibos tea (Aspalathus linearis) as affected by processing. Food Chemistry, 1996. 55(4): p. 403-411. [CrossRef]

- Volkoff, H., L.J. Hoskins, and S.M. Tuziak, Influence of intrinsic signals and environmental cues on the endocrine control of feeding in fish: potential application in aquaculture. General and Comparative Endocrinology, 2010. 167(3): p. 352-359. [CrossRef]

- Syed, R., et al., Growth performance, haematological assessment and chemical composition of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758) fed different levels of Aloe vera extract as feed additives in a closed aquaculture system. Saudi journal of biological sciences, 2022. 29(1): p. 296-303. [CrossRef]

- Bureau, D.P., J. Gibson, and A. El-Mowafi, Use of animal fats in aquaculture feeds. Avances en Nutrición Acuicola, 2002.

- Vivas, M., et al., Dietary self-selection in sharpsnout seabream (Diplodus puntazzo) fed paired macronutrient feeds and challenged with protein dilution. Aquaculture, 2006. 251(2-4): p. 430-437. [CrossRef]

- Fortes-Silva, R., I.G. Guimaraes, and E.d.F.F. Martíns, Feeding Practices and Their Determinants in Tilapia. Biology and Aquaculture of Tilapia, 2021: p. 86.

- Hasanpour, S., et al., Effects of dietary green tea (Camellia sinensis L.) supplementation on growth performance, lipid metabolism, and antioxidant status in a sturgeon hybrid of Sterlet (Huso huso♂× Acipenser ruthenus♀) fed oxidized fish oil. Fish Physiology and Biochemistry, 2017. 43: p. 1315-1323.

- Nootash, S. Nootash, S., et al., Green tea (Camellia sinensis) administration induces expression of immune relevant genes and biochemical parameters in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Fish & shellfish immunology, 2013. 35(6): p. 1916-1923. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., et al., The effect of green tea waste on growth and health of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus). Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 2016. 16(3): p. 679-689.

- McKay, D.L. and J.B. Blumberg, A review of the bioactivity of South African herbal teas: rooibos (Aspalathus linearis) and honeybush (Cyclopia intermedia). Phytotherapy Research: An International Journal Devoted to Pharmacological and Toxicological Evaluation of Natural Product Derivatives, 2007. 21(1): p. 1-16.

- Shahidi, F., Antioxidant properties of food phenolics. Phenolics in food and nutraceuticals, 2004.

- Kay, C.D., P.A. Kroon, and A. Cassidy, The bioactivity of dietary anthocyanins is likely to be mediated by their degradation products. Molecular nutrition & food research, 2009. 53(S1): p. S92-S101. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y., et al., Antiglycative effects of protocatechuic acid in the kidneys of diabetic mice. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 2011. 59(9): p. 5117-5124. [CrossRef]

- Tan, X., J. Zhu, and M. Wakisaka, Effect of protocatechuic acid on Euglena gracilis growth and accumulation of metabolites. Sustainability, 2020. 12(21): p. 9158. [CrossRef]

- Mahfuz, S., Q. Shang, and X. Piao, Phenolic compounds as natural feed additives in poultry and swine diets: A review. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, 2021. 12(1): p. 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Tánori-Lozano, A., et al., Influence of ferulic acid and clinoptilolite supplementation on growth performance, carcass, meat quality, and fatty acid profile of finished lambs. Journal of Animal Science and Technology, 2022. 64(2): p. 274. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N. and N. Goel, Phenolic acids: Natural versatile molecules with promising therapeutic applications. Biotechnology reports, 2019. 24: p. e00370. [CrossRef]

- Mountzouris, K., et al., Assessment of a phytogenic feed additive effect on broiler growth performance, nutrient digestibility and caecal microflora composition. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2011. 168(3-4): p. 223-231. [CrossRef]

- Viveros, A., et al., Effects of dietary polyphenol-rich grape products on intestinal microflora and gut morphology in broiler chicks. Poultry science, 2011. 90(3): p. 566-578. [CrossRef]

- Christaki, E., et al., Innovative uses of aromatic plants as natural supplements in nutrition, in Feed additives. 2020, Elsevier. p. 19-34.

- Shakerdi, L.A., et al., Determination of the lactose and galactose content of common foods: Relevance to galactosemia. Food Science & Nutrition, 2022. 10(11): p. 3789-3800. [CrossRef]

- Craig, S.R., et al., Understanding fish nutrition, feeds, and feeding. 2017.

- Tedesco, M., et al., Assessment of the antiproliferative and antigenotoxic activity and phytochemical screening of aqueous extracts of Sambucus australis Cham. & Schltdl.(ADOXACEAE). Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 2017. 89: p. 2141-2154. [CrossRef]

- Barka, S., et al., Monitoring genotoxicity in freshwater microcrustaceans: A new application of the micronucleus assay. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis, 2016. 803: p. 27-33. [CrossRef]

- Polard, T., et al., Giemsa versus acridine orange staining in the fish micronucleus assay and validation for use in water quality monitoring. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety, 2011. 74(1): p. 144-149. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, M. and M. Santos, Induction of EROD Activity and Genotoxic Effects by Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Resin Acids on the Juvenile Eel (Anguilla anguillaL.). Ecotoxicology and environmental safety, 1997. 38(3): p. 252-259. [CrossRef]

- Grisolia, C.K., A comparison between mouse and fish micronucleus test using cyclophosphamide, mitomycin C and various pesticides. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis, 2002. 518(2): p. 145-150. [CrossRef]

- Minissi, S., E. Ciccotti, and M. Rizzoni, Micronucleus test in erythrocytes of Barbus plebejus (Teleostei, Pisces) from two natural environments: a bioassay for the in situ detection of mutagens in freshwater. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology, 1996. 367(4): p. 245-251. [CrossRef]

- Araldi, R.P., et al., Using the comet and micronucleus assays for genotoxicity studies: A review. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 2015. 72: p. 74-82. [CrossRef]

- Zapata, A., et al., Ontogeny of the immune system of fish. Fish & shellfish immunology, 2006. 20(2): p. 126-136. [CrossRef]

- Fraga, C.G., et al., Basic biochemical mechanisms behind the health benefits of polyphenols. Molecular aspects of medicine, 2010. 31(6): p. 435-445.

- Khan, A.-u. and A.H. Gilani, Selective bronchodilatory effect of Rooibos tea (Aspalathus linearis) and its flavonoid, chrysoeriol. European journal of nutrition, 2006. 45: p. 463-469. [CrossRef]

- Marnewick, J.L., et al., Effects of rooibos (Aspalathus linearis) on oxidative stress and biochemical parameters in adults at risk for cardiovascular disease. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 2011. 133(1): p. 46-52. [CrossRef]

- Opuwari, C. and T. Monsees, In vivo effects of A spalathus linearis (rooibos) on male rat reproductive functions. Andrologia, 2014. 46(8): p. 867-877.

- Sanderson, M., et al., Effects of fermented rooibos (Aspalathus linearis) on adipocyte differentiation. Phytomedicine, 2014. 21(2): p. 109-117. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, M. and E. Stevens, Size and hematological impact of the splenic erythrocyte reservoir in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Fish Physiology and Biochemistry, 1991. 9: p. 39-50. [CrossRef]

- Graf, R. and J. Schlüns, Ultrastructural and histochemical investigation of the terminal capillaries in the spleen of the carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). Cell and Tissue Research, 1979. 196: p. 289-306. [CrossRef]

- Chiller, J., H. Hodgins, and R. Weiser, Antibody response in rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri) II. Studies on the kinetics of development of antibody-producing cells and on complement and natural hemolysin. The Journal of Immunology, 1969. 102(5): p. 1202-1207.

- Whyte, S.K., The innate immune response of finfish–a review of current knowledge. Fish & shellfish immunology, 2007. 23(6): p. 1127-1151. [CrossRef]

- Espenes, A., et al., Immune-complex trapping in the splenic ellipsoids of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Cell and tissue research, 1995. 282: p. 41-48. [CrossRef]

- Raida, M.K. and K. Buchmann, Development of adaptive immunity in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum) surviving an infection with Yersinia ruckeri. Fish & shellfish immunology, 2008. 25(5): p. 533-541. [CrossRef]

- Torrealba, D., et al., Innate immunity provides biomarkers of health for teleosts exposed to nanoparticles. Frontiers in immunology, 2019. 9: p. 3074. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A.R., et al., Effect of different dietary vitamin E levels on growth, fish composition, fillet quality and liver histology of meagre (Argyrosomus regius). Aquaculture, 2017. 468: p. 175-183.

- Rašković, B., et al., Histological methods in the assessment of different feed effects on liver and intestine of fish. Journal of Agricultural Sciences (Belgrade), 2011. 56(1): p. 87-100. [CrossRef]

- Bilen, A.M. and S. Bilen, Effect of diet on the fatty acids composition of cultured sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) liver tissues and histology compared with wild sea bass caught in Eagean Sea. Marine Science and Technology Bulletin, 2013. 2(1): p. 15-21.

- Coz-Rakovac, R., et al., Blood chemistry and histological properties of wild and cultured sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) in the North Adriatic Sea. Veterinary research communications, 2005. 29: p. 677-687. [CrossRef]

- Spisni, E., et al., Hepatic steatosis in artificially fed marine teleosts. Journal of Fish Diseases, 1998. 21(3): p. 177-184.

| FRT* | GRT* | |

|---|---|---|

| Essential amino acids (Concentration mg/L) | ||

| Alanine | 23.58 | 26.95 |

| Glycine | 16.6 | 19.69 |

| Valine | 15.25 | 17.64 |

| Leucine | 30.44 | 36.21 |

| Isoleucine | 11.9 | 13.89 |

| Proline | 24.98 | 31.02 |

| Methionine | 6.59 | 7.07 |

| Serine | 11.09 | 12.95 |

| Threonine | 22.79 | 25.16 |

| Phenylalanine | 17.28 | 20.48 |

| Aspartic acid | 30.21 | 44.27 |

| Glutamic acid | 41.43 | 47.95 |

| Asparagine | 10.64 | 12.43 |

| Tyrosine | 10.87 | 12.77 |

| Phenolic acids (Concentration ppb:µg/L) | ||

| FRT* | GRT* | |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic_acid | 183.93 | 71.72 |

| Vanillic acid | 752.47 | 161.62 |

| Protocatechuic acid | 1243 | 920.2 |

| m-coumaric acid | − | − |

| p-coumaric acid | 129.43 | 77.75 |

| Syringic acid | 1404.98 | 135.83 |

| Ferulic acid | 3572.69 | 833.71 |

| Caffeic acid | 490.83 | 88.36 |

| Diets | CBD* | FRT* | GRT* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proximate Composition % | |||

| Dry matter | 95.28 | 95.29 | 95.32 |

| Moisture | 4.72 | 4.71 | 4.68 |

| Protein | 32.99 | 32.8 | 33.17 |

| Fat | 4.94 | 4.75 | 4.81 |

| Ash | 7.03 | 6.98 | 7.03 |

| Fibre | 3.32 | 2.69 | 3.87 |

| Carbohydrates | 50.01 | 50.73 | 50.31 |

| Growth parameters | Basal diet | FRT* | GRT* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial number of fish - NI | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| Initial body weight (g) - IBL | 0.55 ± 0.02a | 0.55 ± 0.02a | 0.54 ± 0.03a |

| Initial body length (cm) - IBL | 2.22 ± 0.41a | 2.24 ± 0.30a | 2.21 ± 0.45a |

| Final body weight (cm) - FBW | 2.86 ± 0.60a | 4.01 ± 0.88b | 4.13 ± 0.75b |

| Final body length (cm) - FBL | 5.25 ± 0.51a | 5.51 ± 0.50ab | 5.84 ± 0.46bc |

| SGR (%) | 3.65 ± 0.40 a | 4.38 ± 0.44 b | 4.48 ± 0.42 b |

| Condition factor (%) - CF | 13.14 ± 4.87 a | 6.92 ± 2.45 b | 6.70 ± 2.53 b |

| Growth (%) | 5.15 ± 1.32 a | 7.69 ± 1.95 b | 7.98 ± 1.65 b |

| HIS (%) | 6.59 ± 1.91a | 6.75± 1.96a | 7.02 ± 2.10a |

| VSI (%) | 21.06 ± 7.10a | 22.91 ± 11.87b | 26.64 ± 12.52c * |

| Rate of weight gain (g) - RWG | 2.32 ± 0.59 a | 3.46 ± 0.88 b | 3.59 ± 0.74 b |

| Food conversion ratio (%) – FCR | 2.32± 0.57a | 1.50± 0.25b | 1.41± 0.07b |

| Survival Rate (%) - SR | 95.30 | 96.70 | 96.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).