Submitted:

02 October 2023

Posted:

03 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

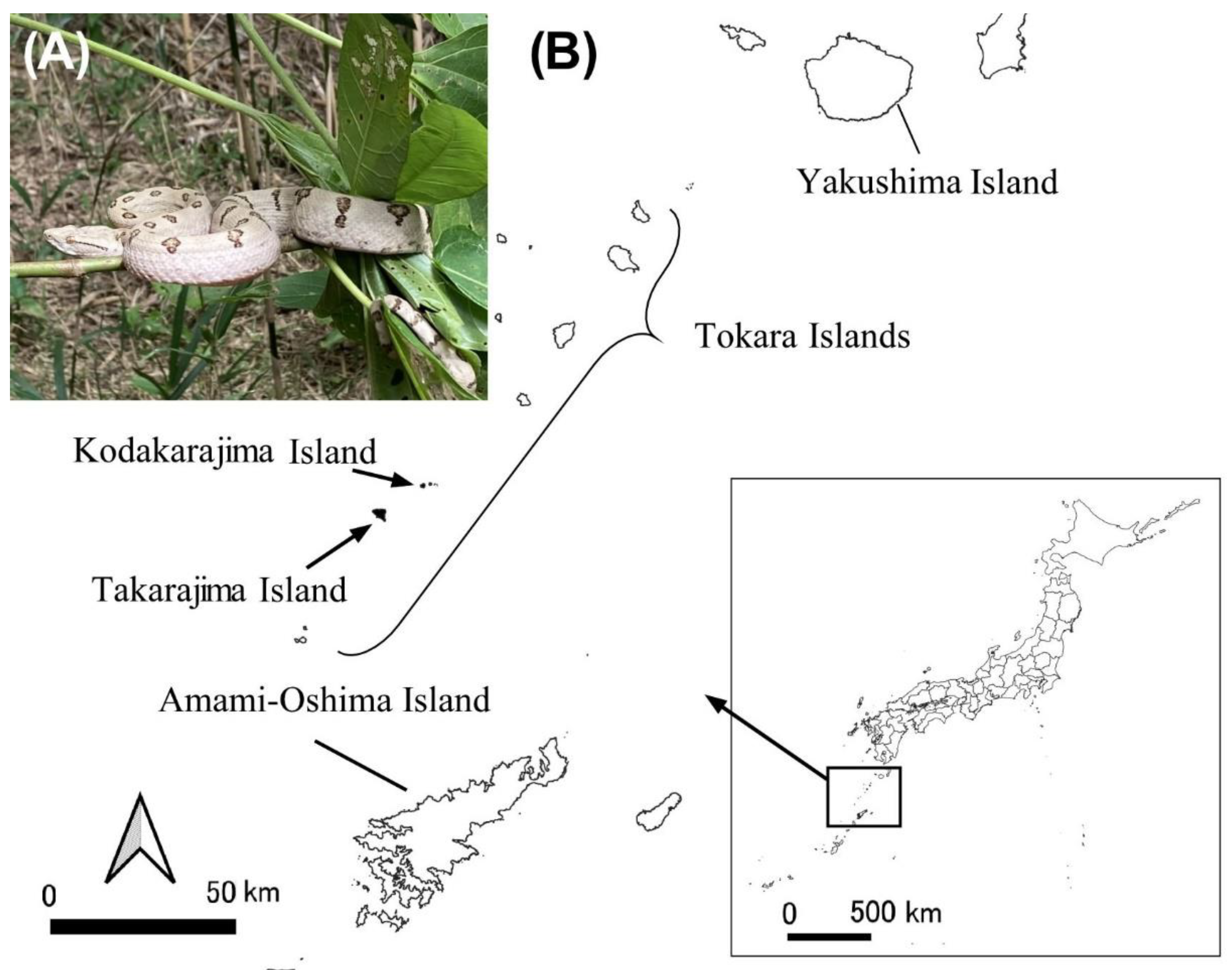

2.1. Sampling location

2.2. Ethics approval

2.3. Substances and Reagents

2.4. Functional study

2.5. Nitric Oxide Quantification Using Fluorescence

2.6. Statistical analysis

2.7. Field research

3. Results

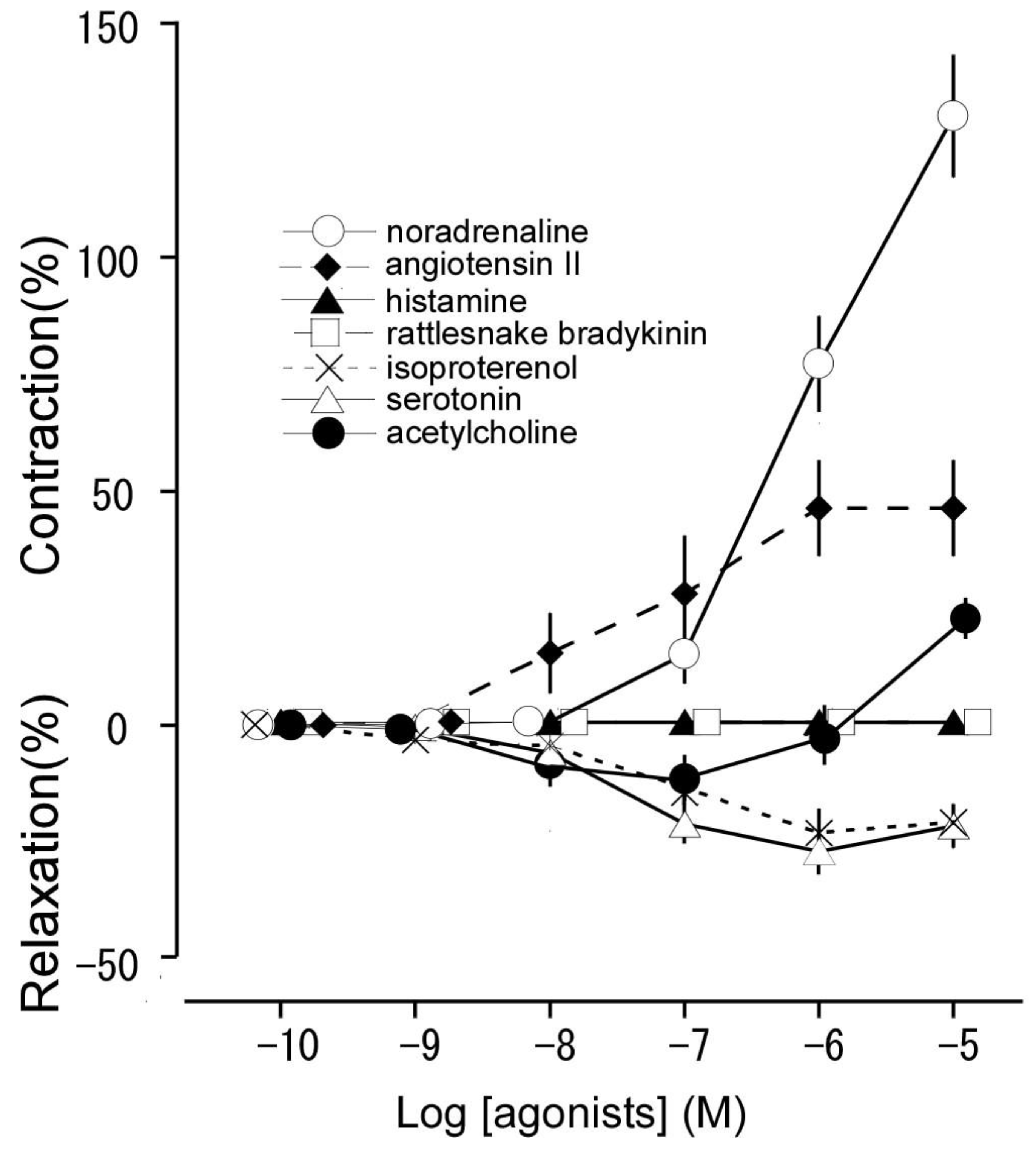

3.1. Responsiveness to noradrenaline, angiotensin II, histamine, rattlesnake bradykinin, isoproterenol, serotonin, and acetylcholine

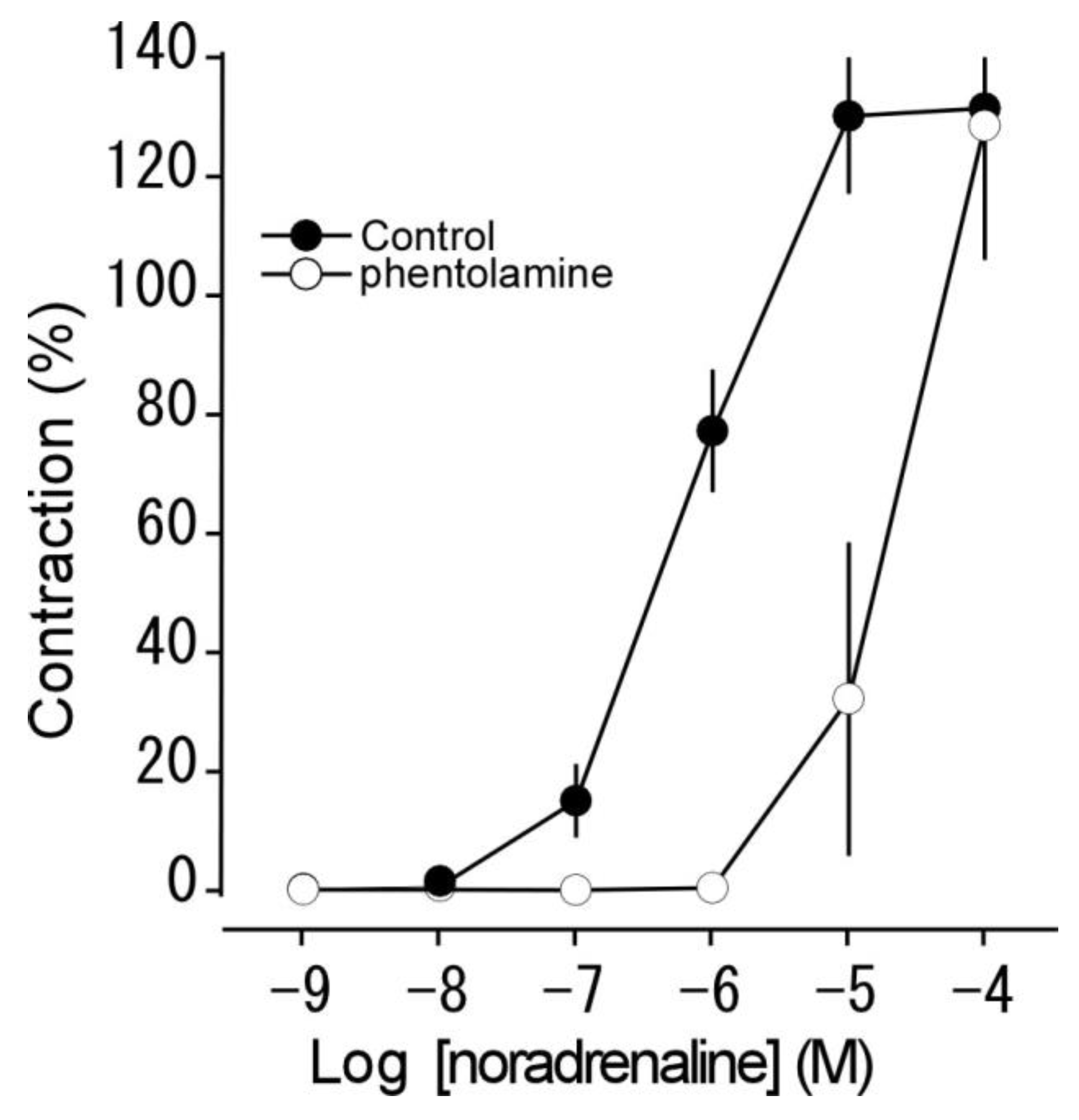

3.2. Effect of phentolamine on noradrenaline-induced contraction

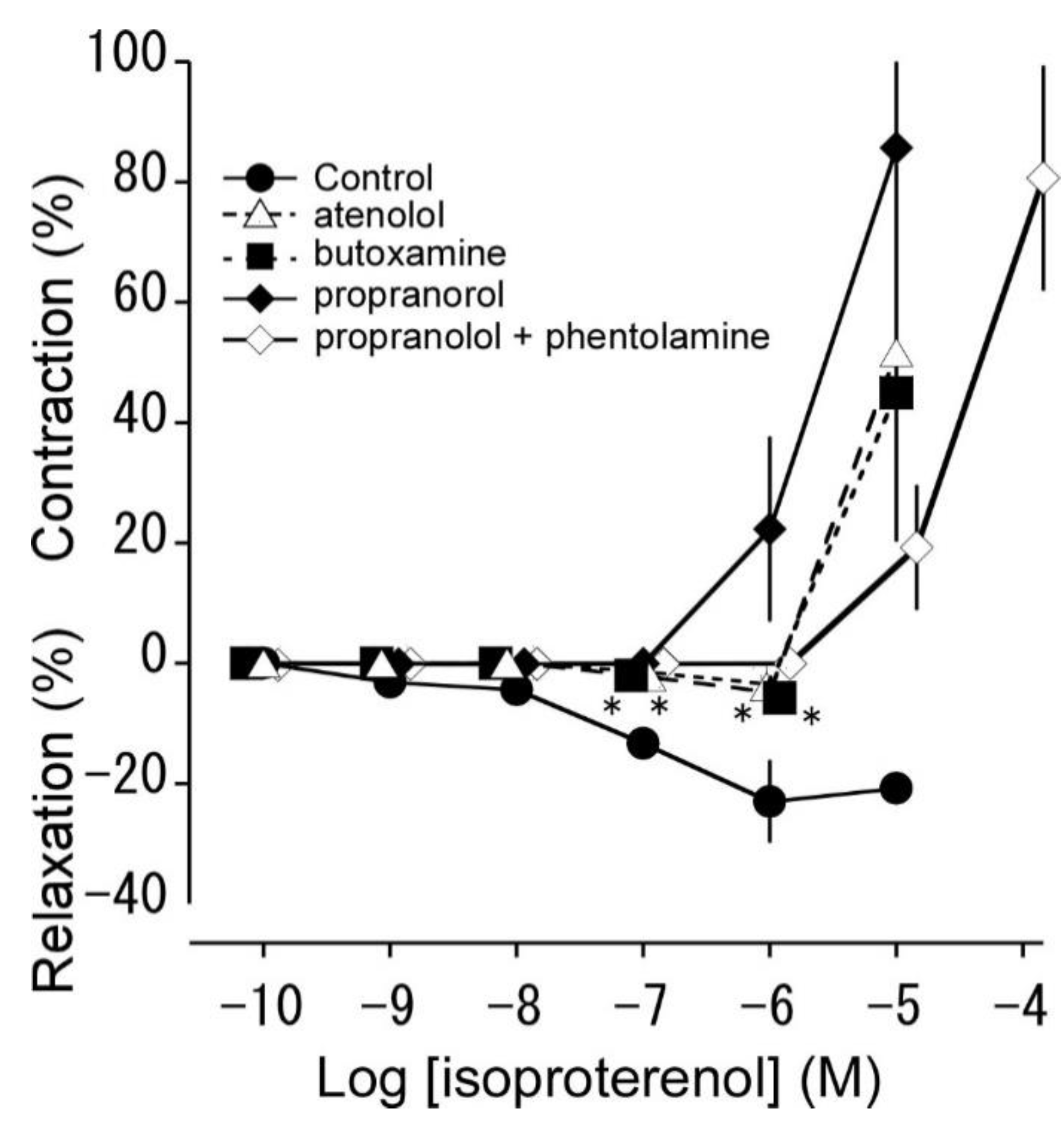

3.3. Effects of β adrenoceptor antagonists on isoproterenol-induced relaxation

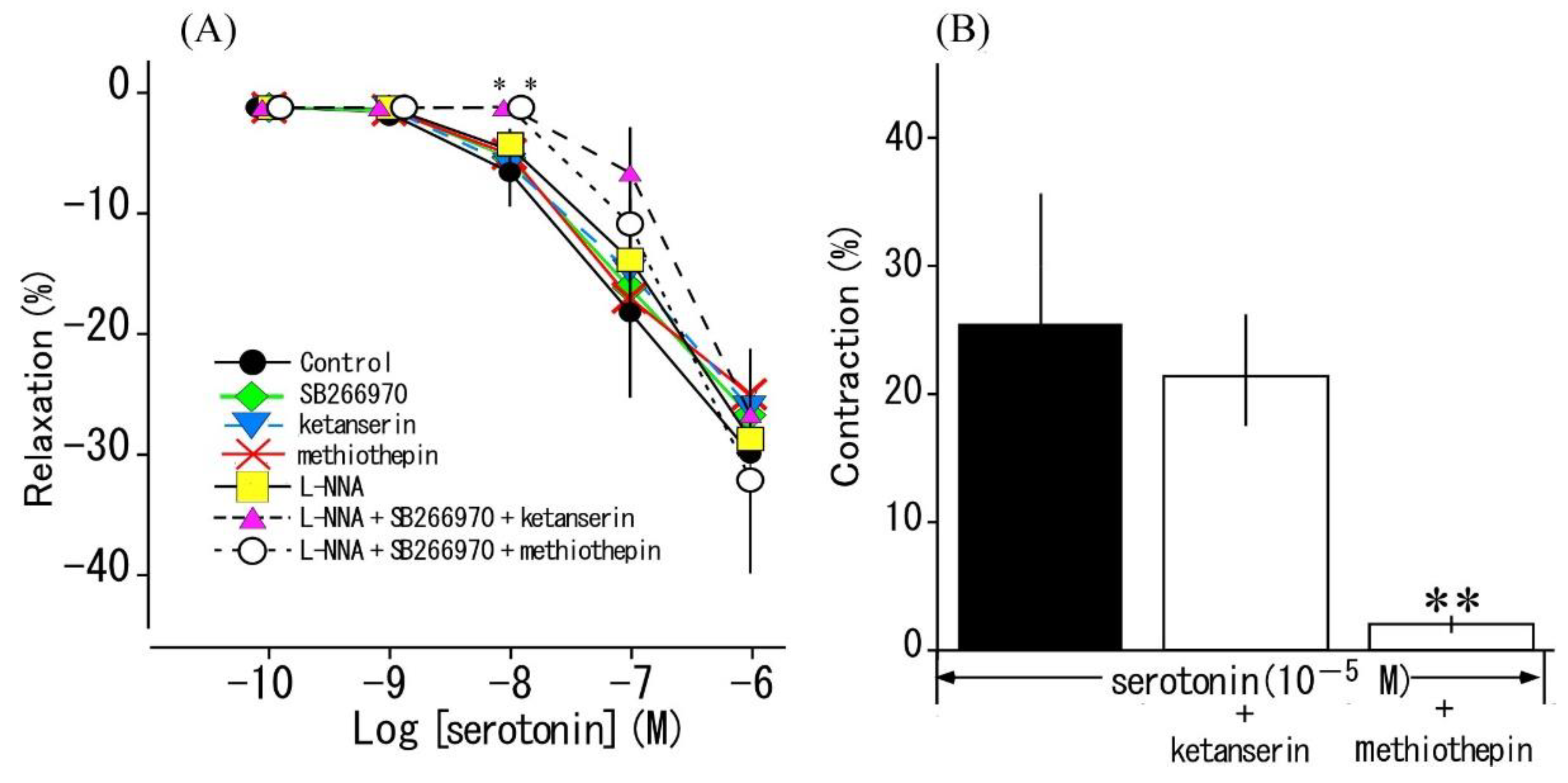

3.4. Effects of serotonin receptor antagonists and L-NNA on serotonin-induced responses

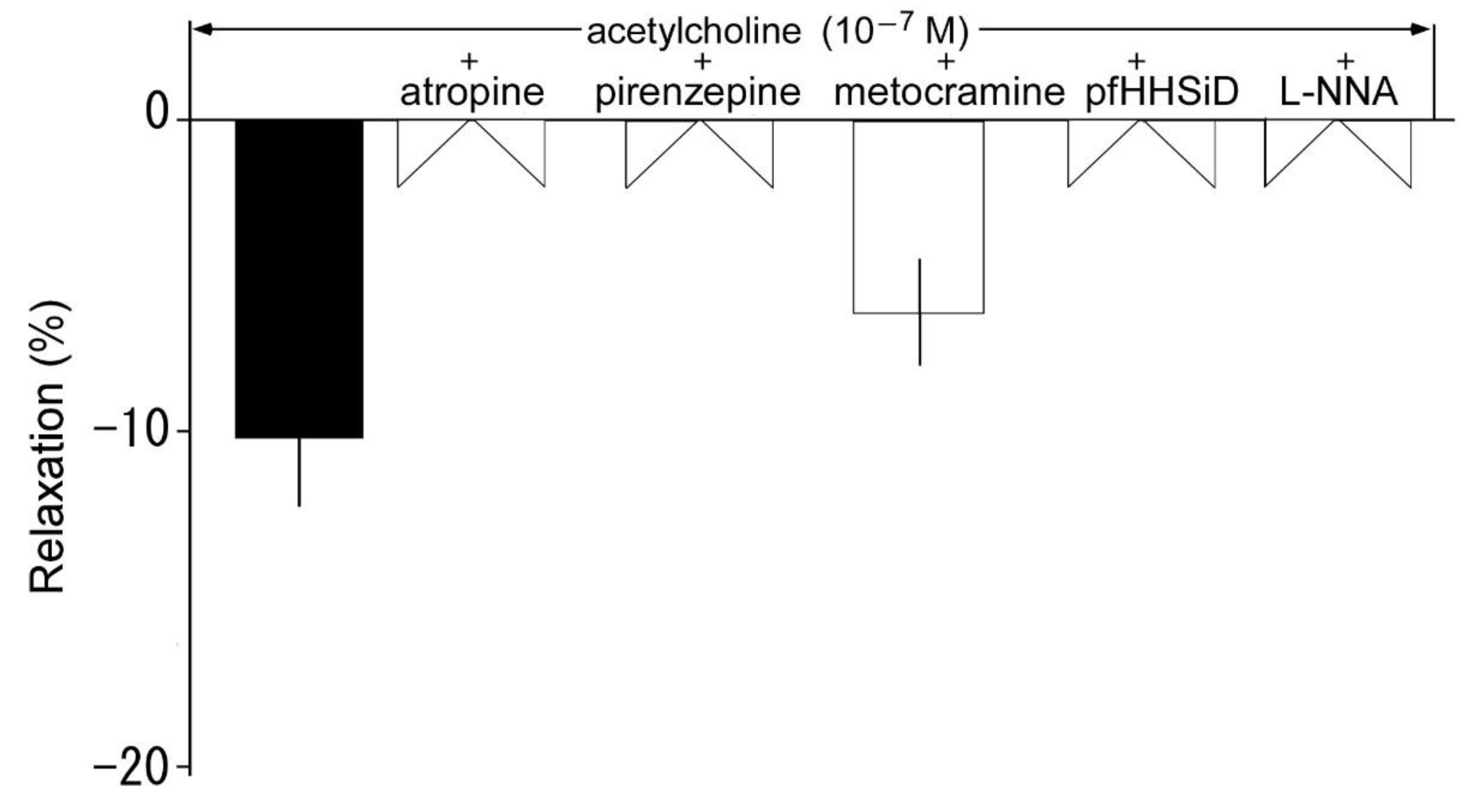

3.5. Effects of muscarine receptor antagonists on acetylcholine-induced relaxation

3.6. Effects of muscarine receptor antagonists on acetylcholine-induced contraction in the presence of L-NNA

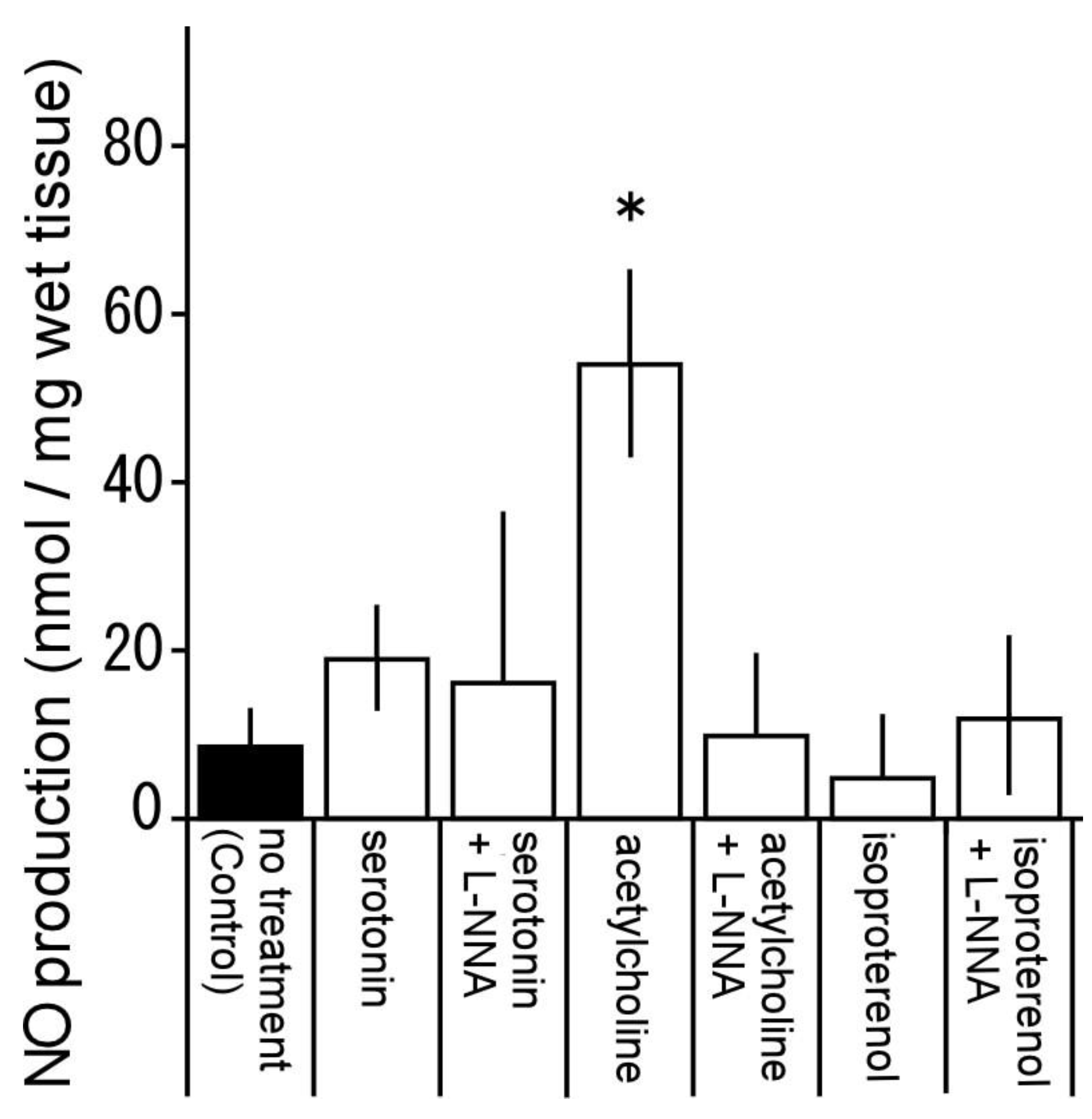

3.7. Nitric oxide production by serotonin, acetylcholine and isoproterenol

3.8. Result of field observation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caldwell, M.W.; Nydam, R.L.; Palci, A.; Apesteguía, S. The oldest known snakes from the Middle Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous provide insights on snake evolution. Nat. Comun. 2015, 6, 5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, D.; Sheehy III, C.M.; Lillywhite, H.B. Variation of organ position in snakes. J. Morphol. 2019, 280, 1798–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, K.; Koutsouris, D.; Zaravinos, A.; Lambrou, G.I. Gravitational influence on human living systems and the evolution of species on earth. Molecules 2021, 26, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seymour, R.S.; Hargens, A.R.; Pedley, T.J. The heart works against gravity. Am. J. Physiol.: Regul., Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1993, 265, R715–R720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, C.R.; Seymour, R.S. The role of gravity in the evolution of mammalian blood pressure. Evol. 2014, 68, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteves, C.A.; Burckhardt, P.L.; Breno, M.C. Presence of functional angiotensin II receptor and angiotensin converting enzyme in the aorta of the snake Bothrops jararaca. Life Sci. 2012, 91, 944–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, W.; Chiu, K. Contractile response of the isolated dorsal aorta of the snake to angiotensin II and norepinephrine. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1985, 60, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, G.E.; Burnstock, G. Acetylcholine induces relaxation via the release of nitric oxide from endothelial cells of the garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis parietalis) aorta. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C: Pharmacol., Toxicol. Endocrinol. 1993, 106, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanouye, N.; Picarelli, Z. Characterization of postjunctional alpha-adrenoceptors in the isolated aorta of the snake Bothrops jararaca. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C: Pharmacol., Toxicol. Endocrinol. 1992, 615–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, D.J.; Lillywhite, H.B.; Olson, K.R.; Ballard, R.E.; Hargens, A.R. Blood vessel adaptation to gravity in a semi-arboreal snake. J. Comp. Physiol. B 1996, 165, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, M. Red Data Book 2014.-Threatened Wildlife of Japan -: Reptilia /Amphibia; Ministry of Environment (ed.); GYOSEI Corporation: Tokyo, Japan, 2014; p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Shibata, H.; Chijiwa, T.; Hattori, S.; Terada, K.; Ohno, M.; Fukumaki, Y. The taxonomic position and the unexpected divergence of the Habu viper, Protobothrops among Japanese subtropical islands. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016, 101, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tashiro, Y.; Goto, A.; Kunisue, T.; Tanabe, S. Contamination of habu (Protobothrops flavoviridis) in Okinawa, Japan by persistent organochlorine chemicals. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 1018–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. Maps & Geospatial Information. 2023. Available online: https://www.gsi.go.jp/ENGLISH/page_e30031.html (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Perry, S.F.; Capaldo, A. The autonomic nervous system and chromaffin tissue: neuroendocrine regulation of catecholamine secretion in non-mammalian vertebrates. Auton. Neurosci. 2011, 165, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravhe, I.S.; Krishnan, A.; Manoj, N. Evolutionary history of histamine receptors: early vertebrate origin and expansion of the H3–H4 subtypes. Mol. Phylogent. Evol. 2021, 154, 106989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Filogonio, R.; Joyce, W. Evolution of the cardiovascular autonomic nervous system in vertebrates. In Primer on the autonomic nervous system, 4th ed.; Biaggioni, I., Browning, K., Fink, G., Jordan, J., Low, P.A., Paton, J.F.R., Eds.; Elsevier Inc./Academic Press: San Diego, USA, 2023; pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinaga, N.; Okuno, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Shiraishi, M.; Obi, T.; Yabuki, A.; Miyamoto, A. Vasomotor effects of noradrenaline, acetylcholine, histamine, 5-hydroxytryptamine and bradykinin on snake (Trimeresurus flavoviridis) basilar arteries. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C: Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2007, 146, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Ootawa, T.; Sekio, R.; Smith, H.; Islam, M.Z.; Uno, Y.; Shiraishi, M.; Miyamoto, A. Involvement of beta3-adrenergic receptors in relaxation mediated by nitric oxide in chicken basilar artery. Poultry Sci. 2023, 102, 102633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, S.M.; De Haan, J.M.; Shapiro, L.; Ruane, S. Habits and characteristics of arboreal snakes worldwide: arboreality constrains body size but does not affect lineage diversification. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2018, 125, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.Z.; Van Dao, C.; Miyamoto, A.; Shiraishi, M. Rho-kinase and the nitric oxide pathway modulate basilar arterial reactivity to acetylcholine and angiotensin II in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Naunyn-Schmiedeb’rg's Arch. Pharmacol. 2017, 390, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, F.; Watanabe, Y.; Obi, T.; Islam, M.; Yamazaki-Himeno, E.; Shiraishi, M.; Miyamoto, A. Characterization of 5-hydroxytryptamine-induced contraction and acetylcholine-induced relaxation in isolated chicken basilar artery. Poult. Sci. 2012, 91, 1158–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalkjær, C.; Wang, T. The Remarkable Cardiovascular System of Giraffes. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2021, 83, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, G.; Skinner, J.D. An allometric analysis of the giraffe cardiovascular system. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2009, 154, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.T.; Stefanescu, A.; He, J. The global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillywhite, H.B. Snakes, blood circulation and gravity. Sci. Am. 1988, 259, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillywhite, H.B.; Albert, J.S.; Sheehy, C.M.; Seymour, R.S. Gravity and the evolution of cardiopulmonary morphology in snakes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2012, 161, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, B.J.; Dyer, D.C. Pharmacological characterization of α-adrenoceptors in the bovine median caudal artery. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997, 339, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgheresi, R.A.; Dalle Lucca, J.; Carmona, E.; Picarelli, Z.P. Isolation and identification of angiotensin-like peptides from the plasma of the snake Bothrops jararaca. Comp. Biochem. Physiol., Part B: Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1996, 113, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A. Comparative physiology of the renin-angiotensin system. In Federation Proceedings,; 1977; Volume 36, pp. 1776–1780. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Y.; Horinouchi, T.; Koike, K. New insights into β-adrenoceptors in smooth muscle: Distribution of receptor subtypes and molecular mechanisms triggering muscle relaxation. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2005, 32, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardou, M.; Loustalot, C.; Cortijo, J.; Simon, B.; Naline, E.; Dumas, M.; Esteve, S.; Croci, T.; Chalon, P.; Frydman, R.; et al. Functional, biochemical and molecular biological evidence for a possible β3-adrenoceptor in human near-term myometrium. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000, 130, 1960–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flacco, N.; Segura, V.; Perez-Aso, M.; Estrada, S.; Seller, J.; Jiménez-Altayó, F.; Noguera, M. ’ D'Ocon, P.; Vila, E.; Ivorra, M. Different β-adrenoceptor subtypes coupling to cAMP or NO/cGMP pathways: implications in the relaxant response of rat conductance and resistance vessels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 169, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, J.; Hoyer, D. Molecular biology of 5-HT receptors. Behav. Brain Res. 2008, 195, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, J.; Lillywhite, H. Adrenergic nerves and 5-hydroxytryptamine-containing cells in the pulmonary vasculature of the aquatic file snake Acrochordus granulatus. Cell Tissue Res. 1989, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodelsson, M.; Törnebrandt, K.; Arneklo-Nobin, B. Endothelial relaxing 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors in the rat jugular vein: similarity with the 5-hydroxytryptamine1C receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993, 264, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ellis, E.S. , Byrne, C., Murphy, O.E., Tilford, N.S., Baxter, G.S. Mediation by 5-hydroxytryptamine2B receptors of endothelium-dependent relaxation in rat jugular vein. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995, 114, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glusa, E.; Pertz, H.H. Further evidence that 5-HT-induced relaxation of pig pulmonary artery is mediated by endothelial 5-HT2B receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000, 130, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jähnichen, S.; Glusa, E.; Pertz, H.H. Evidence for 5-HT2B and 5-HT7 receptor-mediated relaxation in pulmonary arteries of weaned pigs. Naunyn-Schmiedeb’rg's Arch. Pharmacol. 2005, 371, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obit, T.; Kabeyama, A.; Nishio, A. Equine coronary artery responds to 5-hydroxytryptamine with relaxation in vitro. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 1994, 17, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovgaard, N.; Møller, K.; Gesser, H.; Wang, T. Histamine induces postprandial tachycardia through a direct effect on cardiac H2-receptors in pythons. Am. J. Physiol.: Regul., Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2009, 296, R774–R785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovgaard, N.; Abe, A.S.; Taylor, E.W.; Wang, T. Cardiovascular effects of histamine in three widely diverse species of reptiles. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2018, 188, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, G.L.; Skovgaard, N.; Abe, A.S.; Taylor, E.W.; Conlon, J.M.; Wang, T. Cardiovascular actions of rattlesnake bradykinin ([Val1, Thr6] bradykinin) in the anesthetized South American rattlesnake Crotalus durissus terrificus. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul., Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2005, 288, R456–R465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Agonists | pEC50 | Emax (%) (reactivity) |

|---|---|---|

| Resting condition (2.4 mN) | ||

| Noradrenaline | 6.04 ± 0.14 | 130.2 ± 13.0 (contraction a) |

| Angiotensin II | 7.39 ± 0.06 | 46.4 ± 10.3 (contraction a) |

| Histamine | − | 0 (no response) |

| Rattlesnake bradykinin | − | 0 (no response) |

| Isoproterenol | 7.11 ± 0.07 | 22.9 ± 0.3 (relaxation b) |

| Serotonin | 7.41 ± 0.28 | 27.6 ± 4.9 (relaxation b) |

| Acetylcholine | 8.25 ± 0.19 | 10.2 ± 3.1 (relaxation b) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).