1. Introduction

Milk proteins are frequently preferred in the development of biological characters of foods because of their high digestibility feature, abundant essential amino acid content [

1]. They are also considered as a fundamental dietary component due to its balanced and adequate nutrient content. In addition to the superior bioactive properties they provide, milk proteins also enable technological characters such as emulsion, oil-water retention capacity and texture [

2,

3].

In recent years, the importance of healthy and functional ingredients has become more widely accepted, leading to an increased demand for improving the functional characteristics of frequently consumed nutrients. This demand generated the food products with peptides containing much more biologically qualified and active components. Enriching food items with low protein content, such as bakery products, especially bread, with milk protein and its hydrolysates can significantly increase their nutritional value [

4]. Enzymatic hydrolysis-based modification of milk proteins has significant potential as a tool in food protein processing to optimize the technofunctional, biological and nutritional properties of proteins [

5]. Casein hydrolyzed formulations have been sold for many years due to their exceptional nutritional content, amino acid composition, commercial availability in huge numbers, and affordable price [

6]. Casein hydrolysates can be used to enhance the nutritional value, stability, shelf life, and many other characteristics of various food products as well as protein supplements [

7].

The use of frozen dough in bread and bakery products has been increasingly used. Basic factors like shelf life and bakery quality may be regulated with the use of frozen dough, at the same time, it enables the production of huge quantities of dough, ease of storage and transportation, and the production of fresh products in small and medium-sized enterprises [

8]. It is known that the freezing and thawing process in the production of frozen bread damages the gluten network [

9] and prevents the bread from rising, thus causing low volume, harder crumb formation [

10,

11]. Some proteins and their hydrolysates have been used by several studies to eliminate these quality deteriorations. Effects of milk protein [

12], pigskin gelatin [

13] and sweet potato protein hydrolysates [

14] on the quality of breads made from frozen dough were investigated. In a study of Zhou et al. [

15] desalted egg white and gelatin mixture system provided a positive effect on the quality of frozen dough by slowing down the increase of the freezable water content and the loss tangent (tanδ) value. Also, cryo-protective effect of ice-binding peptides derived from collagen hydrolysates was reported by Cao et al. [

16].

Additionally, casein hydrolysate could be an alternative for frozen dough quality improvements thanks to its inexpensive and efficient production. Therefore, it was aimed to investigate the contributions of casein hydrolysates produced from savinase to frozen dough and corresponding breads quality in this study. To perform this aim, the rheological, thermal and protein analysis (SDS-PAGE and secondary structure) were studied beside the quality of breads made by frozen dough.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Wheat flour (13.5% moisture, 0.73% ash, 10.8% protein and 58% water absorption) was purchased from Eksun Food Industry Co., Ltd (Tekirdağ, Turkey). Dry yeast (Pakmaya) and salt (Billur) were purchased from a local market. The bovine casein (NaCas) was obtained from a local brand (Milkon, Çallı Food Food Industry and Trade Inc., İstanbul, Turkey). The savinase enzyme (protease from Bacillus sp., 16 U/g), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), acrylamide, and all other chemicals and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

2.2. Preparation casein hydrolysate

For the production of casein hydrolysates, casein was first dissolved with distilled water and kept at +4°C for 10 h. so that the casein could absorb water better. The pH of the casein solutions was adjusted to pH 9, which is optimum for the savinase enzyme using 0.1 N NaOH. Then, the volume of casein solution was completed with distilled water to 5g protein/100mL.Savinase was added to the casein solutions (enzyme:substrate, 1:100) and hydrolyzed for 180 min. in a water bath set at 50°C. During the hydrolysis period, the pH of the solution was adjusted to 9 by using 0.1 N NaOH every 15 min., and the hydrolysis degree (HD) of casein was determined according to the total amount of base consumed and the principle of the pH-stat method [

17]. At the end of the hydrolysis period, enzyme inactivation of the casein solutions was achieved by keeping them in boiling water for 15 min. It was centrifuged at 6500 rpm for 15 min. and the supernatant fraction was freeze-dried.

2.3. Preparation of bread dough and baking

Bread dough formulation (control) consisted of 100 g wheat flour, 2 g dry yeast, 1.5 g salt and 58 g water. The wheat flour was replaced by casein savinase hydrolysate (CSH) at the concentrations of 1%, 1.5% and 2% wheat flour dry basis (w/w) to produce hydrolysate added dough (HD). All ingredients were kneaded in a dough mixer (Kitchen aid, USA) for 5 min. After complete mixing, the dough was sheeted, molded and panned. The unfrozen dough samples were fermented at 30°C and 85% relative humidity (RH) for 2 hours and baked at 235°C for 25 min. in an electrical oven (Maksan, Turkey). The frozen dough samples were directly stored at −35°C for 28 days after shaping. The thawing process was performed at 4 °C for 3 h. After fermentation (30°C and 85% RH for 2 h) of the thawed dough, the same baking procedure was applied.

2.4. Rheological measurements

Unfrozen and thawed dough samples were subjected to dynamic rheological tests by using stress and temperature controlled rotational rheometer (Antonpaar MCR 302, Austria). Frequency sweep test were conducted between 0.1 rad/s and 100 rad/s with a fixed strain of 0.1% in the linear viscoelastic region at 25°C with a 2 mm gap. Two replications of each samples were carried out.

2.5. Freezable water (FW) content

FW content of dough samples was determined by the differential scanning calorimeter (DSC; TA instrument Q20, USA) by using the method of Chen et al. [

14]. 10 mg of dough sample was sealed hermetically in an aluminum tray and an empty aluminum tray was used as the reference. The following heating programme was applied : cooling from 20 °C to − 40 °C at a rate of 5 °C /min and keeping it constant for 5 min, and then heating from − 40 °C to 10 °C at a rate of 5 °C /min. The enthalpy (ΔH) of melting peak was determined during the heating process and FW content (%) was calculated according to equation (1) :

where, ΔH is the enthalpy (J/g) of melting peak of the endothermic curve; ΔHo is the enthalpy (334 J/g) of melting peak of pure water; Wc represents the total water content (%) of the dough, which was measured using a moisture analyzer (Radwag MR50, Poland).

2.6. Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis

SDS-PAGE analyzes of all dough samples were carried out according to the method described by Laemmli [

18]. First, the freeze-dried dough samples were powdered via a grinder. Powder dough samples were mixed with sample buffer at 10 mg/mL and kept in a boiling water bath for 5 min. The samples were added to each loading well as 20 µL and sorted according to their molecular weights by running under 20 mA/gel electric current in the separation gel (7.5% and 20% acrylamide) using a vertical electrophoresis system (Mini-PROTEAN®System, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). After the electrophoresis process, the bands stained with staining solution (comassie brillant blue:methanol:acetic acid:water; 0.25%:50%:10%:39.75%) were removed from excess dye by keeping them in the destaining solution (methanol:acetic acid:water; 50%:10%:40%) and then visualized with the Biorad Gel Doc EZ imaging system.

2.7. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

Secondary structure of dough samples were determined by using a Bruker Tensor 27 spectrometer equipped with a DLa TGS detector (Bremen, Germany). FT-IR spectra of hydrolysates were obtained of wave number from 400 to 4000 cm

-1 during 16 scans per spectra, with 2 cm

− 1 resolution. Deconvolution was applied to all spectra by interpretation of changes in the overlapping amide I band (1600–1700 cm

− 1) using Origin 2020b software [

19].

2.8. Determination of bread quality

2.8.1. Specific volume (SV)

Volume (mL) of bread was measured by using rapeseed displacement method (Method 10-05, AACC 2000). SV of breads was calculated by dividing of volume to the weight (g) of bread.

2.8.2. Texture

Each bread sample was cut into slices that were 1.25 mm thick after cooling for 2h at room temperature. Texture Profile Analysis (TPA) was performed by using texture analyzer (SMS TA.XT2 Plus, UK) equipped with 5 kg load cell and 36 mm diameter cylindrical compression probe. The TPA test was conducted 50% compression, 5.0 mm/s test speed and 5 s delay time between the two compression cycles. Dublicate measurement was performed.

2.8.3. Color

The crust and crumb color of bread samples were measured by using Chromameter (CR-100 Konica Minolta, Japan) recording the lightness ( L*), redness (a*) and yellowness (b* ) values.]. All determinations were carried out in triplicate.Three measurements were taken from each sample. The color differences (

) were determined by using the following equation (2) :

where, L

0*, a

0* and b

0* belong to control bread which is a reference sample while L*, a* and b* belong to bread containing CSH.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan's multiple range tests was used to determine any significant differences (p < 0.05) between the mean values. SPSS version 19.0 software (SSPS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA) was used.

3. Results and Discussion

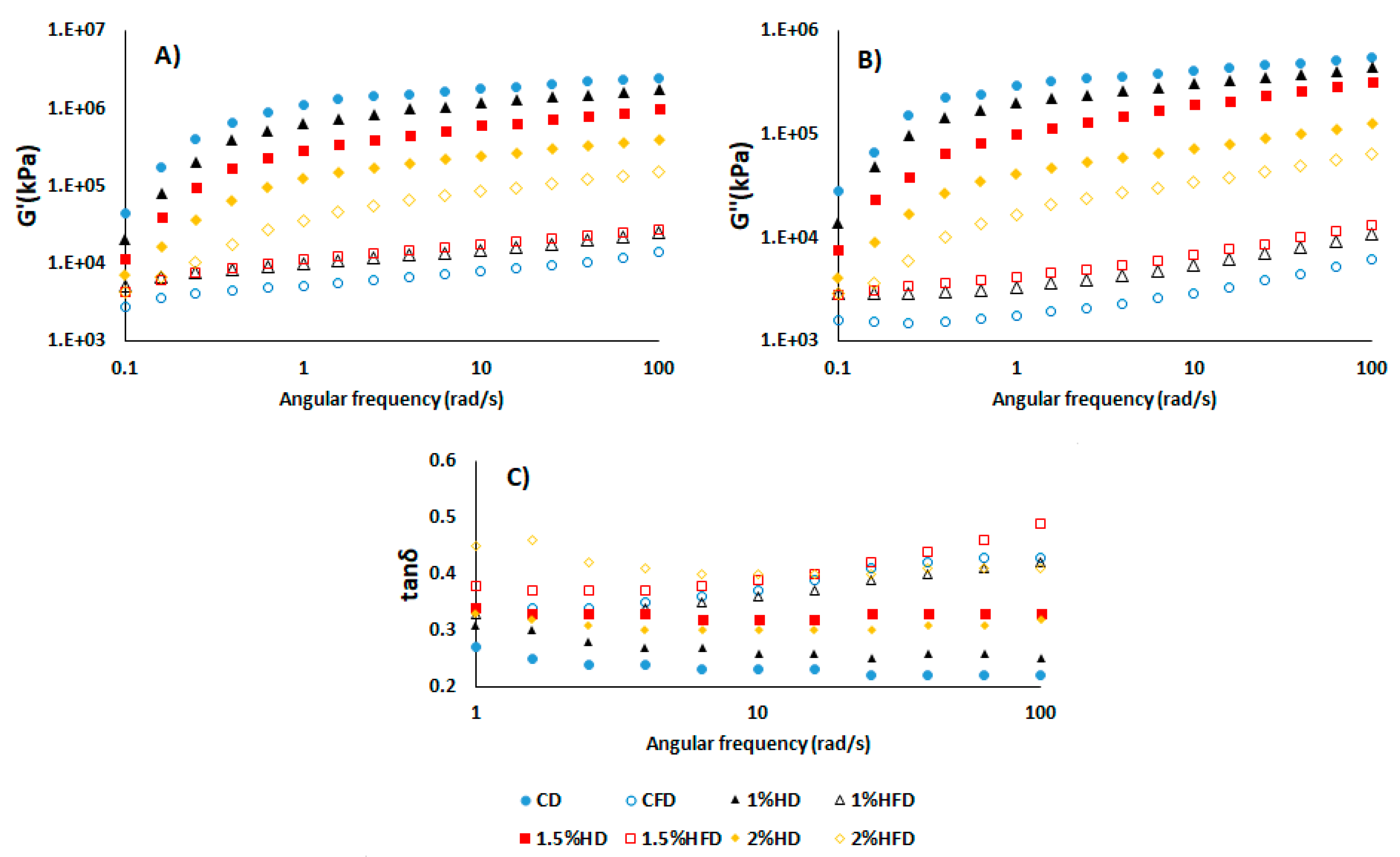

3.1. Dynamic rheological properties of dough

Figure 1 exhibits the storage (Gʹ) and loss (Gʹʹ) modulus of dough samples indicating the elastic and viscous properties, respectively. Loss factor, tan δ, was also shown to reflect the viscoelasticity of samples. For all samples, the G′ was greater than Gʹʹ, showing that the dough was more elastic and exhibits solid-like behaviour [

20]. CSH addition into dough led to a reduction of Gʹ and Gʹʹ values, but a similar trend wasn’t observed in frozen dough samples. Frozen storage decreased the Gʹ and Gʹʹ values of all dough samples and control dough (CD) had the lowest value. Same behaviour were shown in Gʹʹ values. Also, the decreasing effect of frozen storage on dough containing 2% was lower than those of other doughs with CSH (1% HD and 1.5% HD) (

Figure 1B). These results indicated that CSH addition cause a detrimental effect due to lowering Gʹ and Gʹʹ and increasing tan δ values in fresh dough system. According to the study of Khatkar et al. [

21], the flour from wheat showing good bread quality had higher Gʹ value and lower tan δ. On the other hand, addition of CSH improved the gluten strength of frozen dough when compared to control frozen dough (CFD), as a result of elevated Gʹ and Gʹʹ values [

22]. Similar observation reported by Zhou et al. [

15] for a frozen dough system containing desalted egg white and gelatin mixture. In the dynamic rheological measurement of frozen dough system, tan δ value (Gʹʹ/Gʹ) is considered as an important parameter to monitor the viscoelasticity of dough [

22]. The tan δ values obtained in this study were lower than 1, indicating that the elasticity of the samples was greater than the viscosity [

15]. Frozen storage resulted in a remarkable increase of tan δ for all samples (

Figure 1C). The increment of tan δ value during freezing was previously reported by many studies [

14,

15]. This was attributed to the gradual increase of ice crystals during freezing, causing damage to gluten network and subsequently resulting in an increased viscosity of the dough. The rise of tan δ in dough with CSH was lower than CD after frozen storage (

Figure 1C). This can be explained by slowing the ice crystals growth due to the addition of CSH.

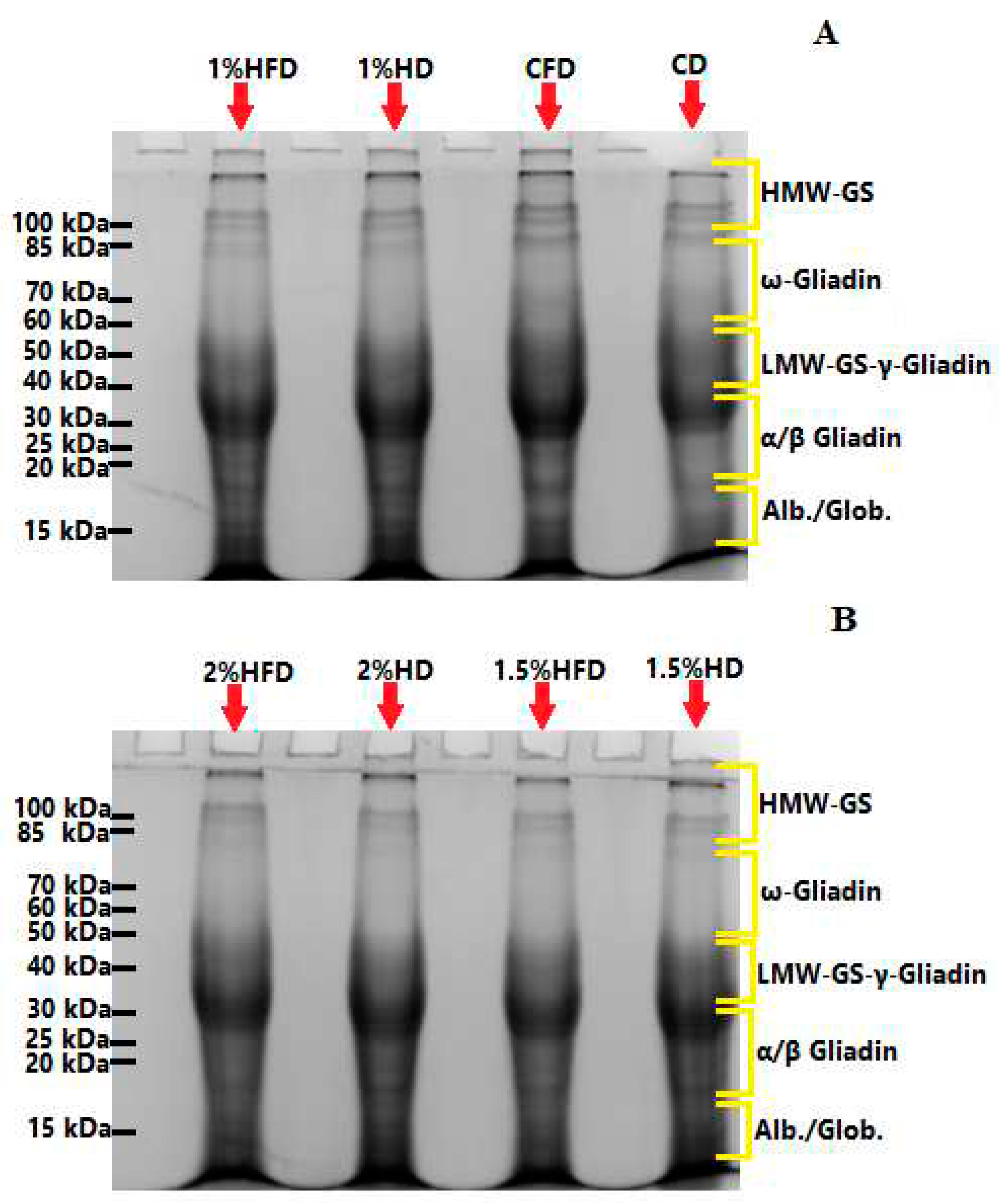

3.2. SDS- PAGE analysis

The changes of SDS-PAGE patterns of proteins with the incorporation of casein hydrolyzate during frozen storage were presented in

Figure 2. Formation of new bands and/or changes of band intensities show polymerization/depolymerization behaviour of gluten network [

23,

24,

25]. Depolymerization exists in the protein matrix of wheat dough when exposed to frozen conditions [

26]. The increase of protein band intensity was observed for control dough (CD) after frozen storage (CFD), indicating that depolymerization of high molecular weigh glutenin subunits (HMW-GS) region occured. Similar results were previously reported by numerous studies for wheat dough under frozen conditions [

13,

26,

27]. As for the samples including casein hydrolyzate, no depolymerization was observed due to frozen storage as there was no increases in band intensities except for 2% HD sample (

Figure 2B). 2% casein hydrolyzate addition increased the band intensity after frozen storage, showing that this level of addition may inhibit the crosslinking of SDS-insoluble proteins and interact with SDS-soluble proteins [

13]. Incorporation of unhydrolyzed pigskin gelatin at 1% level also resulted in an increase of band intensity corresponding to ω-gliadins region in a study of Yu et al. [

13] who suggested that pigskin gelatin contributed to the formation of aggregates through non-covalent interactions. Inclusion of casein hydrolyzate into wheat dough matrix led to a decrease of band intensities in HMW-GS region when compared to CD. It can show that new intreaction between glutenin, casein hydrolyzate and water were formed during dough processing since band intensity increment was observed at low molecular weight glutenin subunit (LMW-GS), γ-gliadin and α/β gliadin region. Another possible explanation of this can be formation of protein polymers with larger size, which were unable to migrate into the resolving gel [

23]. Also, new band formation due to addition of casein hydrolyzate into wheat dough wasn’t observed in the present study, indicating that the absence of new protein interactions. Similar results were reported in a study of Yu et al. [

13] who incorporate the pigskin gelatin into frozen dough, and a study which investigated the effect of natural inulin on frozen dough [

27].

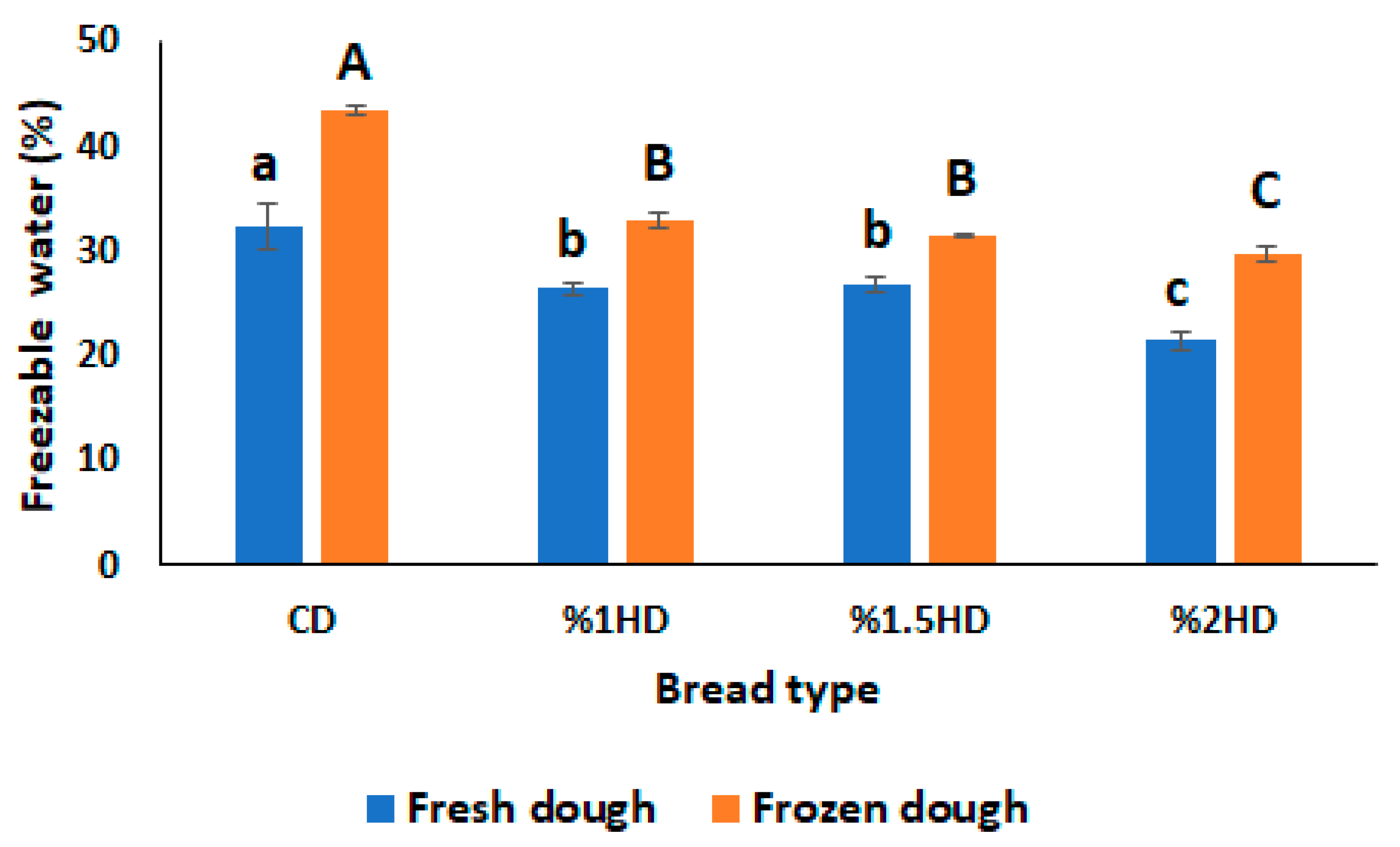

3.3. Freezable water content

Freezable water (FW) in dough produces ice crystals when subjected to freezing. The crystallization amount of ice is directly attributed to FW content in dough and cause the weakening of gluten structure. Therefore, it is important to measure FW content to monitor the quality of dough during frozen storage [

15,

22]. As shown in

Figure 3, FW(%) content of dough samples increased after frozen storage (-30 °C, 28 days) due to formation of ice crystals. The rheological properties of dough is also influenced by FW content since ice crystals disrupted gluten network. This was supported by tan δ value of dough samples after frozen storage (

Figure 1C) due to showing increasing trend. CSH incorporation gradually decreased the FW(%) content of fresh dough. It can be due to binding of water molecules to CSH as stated in a study of Bekiroglu et al. [

7]. Also, the increasing effect of frozen storage on FW(%) was suppressed by the addition of CSH depended on concentration (

Figure 3). 2%HD sample exhibited the lowest FW(%) value, suggesting that 2% CSH substitution level could change the moisture distribution within the dough [

27]. These results are in line with the study carried out by Chen et al. [

14] who investigated the effect of sweet potato protein hydrolysates on the quality of frozen dough. Conversation of bound water to freezable water was also inhibited when desalted egg white and gelatin mixture were added into frozen dough in a study of Zhou et al. [

15].

3.4. Analysis of secondary structure of protein

The secondary structures of gluten proteins corresponding to amides I region (1700 – 1600 cm-1) was shown in

Table 1. Absorption peaks were ascribed as β-sheets (1682-1696 cm-1), β-turns (1662-1681 cm-1), α-helices (1650–1660 cm−1) and random coils (1640–1650 cm−1) based on the reports of Yang et al. [

28] and Zhou et al. [

15]. It was reported that α-helices and β-sheets were relatively orderly and stable, while β-turns and random coils were disordered [

24]. Incorporation of CSH into wheat dough formulation significantly affect the secondary structure of proteins except for β-sheets structure of Day 0. Frozen storage (-30 °C, 28 days) caused a notable reduction in α-helices structure of CD sample (p<0.05) while no significant variation was observed for the samples containing CSH (p>0.05). This can be due to the inhibition of recrystallization by CSH addition in the frozen storage state. The structure of β-turns increased after frozen storage significantly, indicating that transformation of α-helices into β-turns structure during frozen storage [

15]. Reduction of α-helices and increment of β-turns were higher in CD than the doughs with CSH. Random coils structure was not changed during frozen storage (p>0.05), similar with the study of Yu et al. [

13] who investigated the effect of pigskin gelation frozen dough.

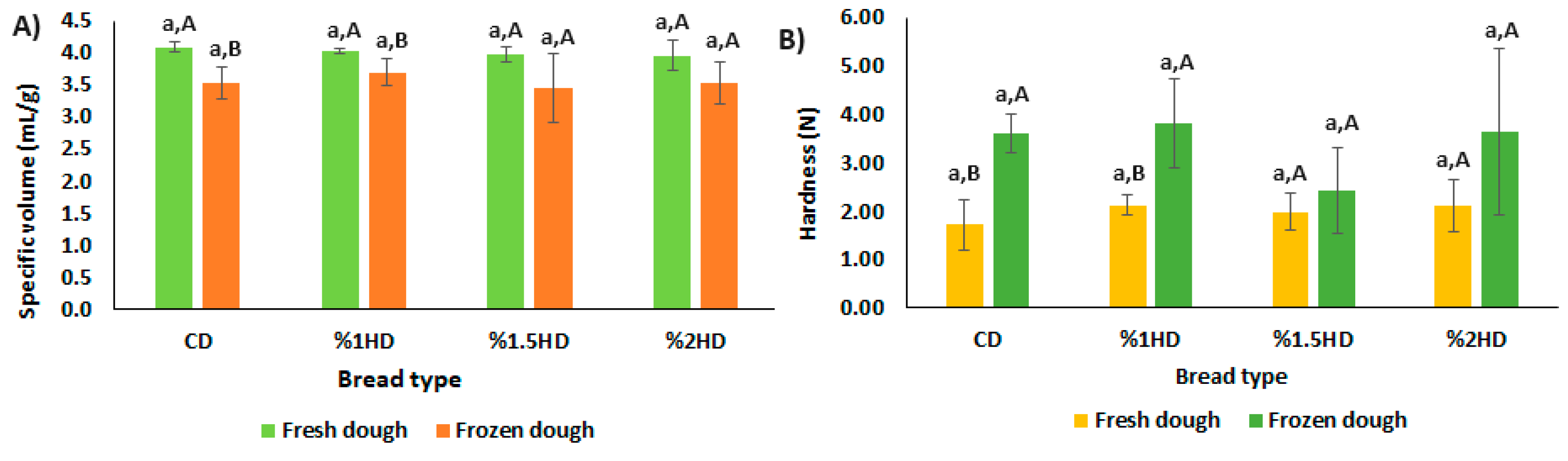

3.5. Specific volume, hardness and color of breads

The quality of breads is mostly evaluated in terms of specific volume (SV), hardness (N) and color characteristics. These criteria are also important indicators that used for monitoring the frozen dough quality.

Figure 4 presents the SV (mL/g) and hardness (N) of bread samples. CSH addition into bread formulation had no remarkable effect on bread quality (p>0.05). The primary impact of frozen storage at -30°C for 28 days on the breads was a reduction in SV values and an increase in hardness. These phenomena, which was previously reported in many studies, suggested that ice crystals during frozen storage lead to decrease the gas-holding capacity of the dough by destroying the structure of gluten [

14,

15]. Also, Cao et al. [

16] noted that the fermentation capacity of the dough was influenced by the growth of ice crystals which decreased the survival of yeast cells. However, the significant effect was shown only in CD and 1%HD after frozen storage (p<0.05). Lowest SV reduction and hardness increment were observed for the breads containing 1.5% and 2% CSH. This can be attributed that FW (%) content of 1.5%HD and 2%HD samples were also lower than CD sample (

Figure 3). Mao et al. [

29] reported that reduction of FW content in frozen dough protect the gluten network by preventing the formation of ice crystals.

The effect of CSH addition and frozen storage (-30 °C, 28 days) on the crust and crumb color of bread samples was shown in

Table 2. CSH addition decreased L* value of the bread crust and significant reduction was observed for the breads containing 1.5% and 2% CSH when compared to control (p<0.05). Browning of the bread crust (decreasing of L* value) with the addition of CSH as a protein source shows intensive Maillard reaction products than control. In a study which investigate the effect of pigskin gelatin in frozen bread, it was indicated the browning of bread crust due to the addition of pigskin gelatin [

13]. Frozen storage caused a significant reduction on b* value of bread crust (p<0.05) while no significant effect was observed for L* and a* value during frozen storage (p > 0.05). Similar result for b* value of bread crust was also reported by Sharadanant and Khan [

30]. In terms of color differences (ΔE), frozen storage had no significant effect on ΔE value of crust color, but the ΔE value of 1.5% HFD and 2% HFD were higher than those of other samples (e.g. CFD and 1% HFD). As for the crumb color, frozen storage resulted in the reduction of L* value of the crumb (p<0.05). Similar trend was also stated by Yu et al. [

13] at the end of 60 days of frozen storage (-18 °C). On the other hand, Shon et al. [

12] reported that no significant effect was observed for crumb L* value during frozen storage (-20 °C, 60 days). Incorporation of CSH into fresh bread increased the b* value of bread crumb (p<0.05). While frozen storage increases crumb b* value of control fresh bread (p<0.05), the breads with CSH were not affected by frozen storage (p > 0.05) in terms of crumb b* value. Color differences (ΔE) in bread crumb was higher in CFD than the frozen dough samples containing CSH (p<0.05).

4. Conclusions

In this study, casein hydrolysate prepared with savinase (CSH) was used to improve the quality of frozen dough. The frozen dough with CSH did not lead to any notable alteration in the structure of α-helices following frozen storage at -30°C for 28 days. The results obtained from dynamic rheological measurement and freezable water content showed that incorporation of CSH into frozen wheat dough slowed down the ice crystals growth. These findings resulted in amelioration in the bread quality of 1.5% and 2% CSH containing samples since lowest specific volume reduction and hardness increment were exhibited. In summary, casein hydrolysate obtained from savinase can be considered as an alternative bakery ingredient for frozen dough system.

Author Contributions

Hatice Bekiroglu : Investigation, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, and writing – original draft. Gorkem Ozulku : Conceptualization, investigation, data curation, and writing – original draft. Osman Sagdic : Supervision, writing – review & editing.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study will be made available upon request.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not‒for‒profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no known conflict of interest.

References

- Gani: A., Broadway, A. A., Masoodi, F. A., Wani, A. A., Maqsood, S., Ashwar, B. A., ... & Gani, A. Enzymatic hydrolysis of whey and casein protein-effect on functional, rheological, textural and sensory properties of breads. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2015; 52, 7697-7709.

- Abd El-Salam, M. H., & El-Shibiny, S. Preparation, properties, and uses of enzymatic milk protein hydrolysates. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 2017; 57(6), 1119-1132. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, G., Nongonierma, A. B., O'Regan, J., & FitzGerald, R. J. Functional properties of bovine milk protein isolate and associated enzymatic hydrolysates. International Dairy Journal, 2018; 81, 113-121. [CrossRef]

- Tang, T., Wu, N., Tang, S., Xiao, N., Jiang, Y., Tu, Y., & Xu, M. Industrial application of protein hydrolysates in food. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2023; 71(4), 1788-1801. [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M. E., Côrrea, A. P. F., Canales, M. M., Daroit, D. J., Brandelli, A., & Risso, P. Biological and physicochemical properties of bovine sodium caseinate hydrolysates obtained by a bacterial protease preparation. Food Hydrocolloids, 2015; 43, 510-520. [CrossRef]

- Clemente, A. Enzymatic protein hydrolysates in human nutrition. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 11(7), 254-262, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Bekiroglu, H., Bozkurt, F., Karadag, A., Ahhmed, A. M., & Sagdic, O. The effects of different protease treatments on the techno-functional, structural, and bioactive properties of bovine casein. Preparative Biochemistry & Biotechnology, 2022; 52(10), 1097-1108. [CrossRef]

- Phimolsiripol, Y., Siripatrawan, U., Tulyathan, V., & Cleland, D. J. Effects of freezing and temperature fluctuations during frozen storage on frozen dough and bread quality. Journal of Food Engineering, 2008; 84(1), 48-56. [CrossRef]

- Berglund, P. T., Shelton, D. R., & Freeman, T. P. by Duration of Frozen Storage and Freeze-Thaw Cycles'. Cereal Chem, 1991; 68(1), 105-107.

- Naito, S., Fukami, S., Mizokami, Y., Ishida, N., Takano, H., Koizumi, M., & Kano, H. Effect of freeze-thaw cycles on the gluten fibrils and crumb grain structures of breads made from frozen doughs. Cereal chemistry, 2004; 81(1), 80-86. [CrossRef]

- Aibara, S., Nishimura, K., & Esaki, K. Effects of shortening on the loaf volume of frozen dough bread. Food Science and Biotechnology, 2001; 10(5), 54-61.

- Shon, J., Yun, Y., Shin, M., Chin, K. B., & Eun, J. B. Effects of milk proteins and gums on quality of bread made from frozen dough. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2009; 89(8), 1407-1415. [CrossRef]

- Yu, W., Xu, D., Zhang, H., Guo, L., Hong, T., Zhang, W., ... & Xu, X. Effect of pigskin gelatin on baking, structural and thermal properties of frozen dough: Comprehensive studies on alteration of gluten network. Food Hydrocolloids, 2020; 102, 105591. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Xiao, J., Tu, J., Yu, L., & Niu, L. The alleviative effect of sweet potato protein hydrolysates on the quality deterioration of frozen dough bread in comparison to trehalose. LWT, 2023; 175, 114505. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B., Dai, Y., Guo, D., Zhang, J., Liang, H., Li, B., ... & Wu, J. Effect of desalted egg white and gelatin mixture system on frozen dough. Food Hydrocolloids, 2022; 132, 107889. [CrossRef]

- Cao, H., Zheng, X., Liu, H., Yuan, M., Ye, T., Wu, X., ... & Xu, F. Cryo-protective effect of ice-binding peptides derived from collagen hydrolysates on the frozen dough and its ice-binding mechanisms. Lwt, 2020; 131, 109678. [CrossRef]

- Adler-Nissen, J. Enzymic hydrolysis of food proteins. Elsevier applied science publishers, 1986.

- Laemmli, U. K. Cleavage of Structural Proteins during the Assembly of the Head of Bacteriophage T4. Nature, 1970; 227, 680–685. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Su, Y., Jia, F., & Jin, H. (2013). Characterization of casein hydrolysates derived from enzymatic hydrolysis. Chemistry Central Journal, 2013; 7, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T. W., Zhang, X., Li, B., & Wu, H. Effect of interesterified blend-based fast-frozen special fat on the physical properties and microstructure of frozen dough. Food chemistry, 2019; 272, 76-83. [CrossRef]

- Khatkar, B. S., Bell, A. E., & Schofield, J. D. The dynamic rheological properties of glutens and gluten sub-fractions from wheats of good and poor bread making quality. Journal of Cereal Science, 1995; 22(1), 29-44. [CrossRef]

- Lu, P., Guo, J., Fan, J., Wang, P., & Yan, X. Combined effect of konjac glucomannan addition and ultrasound treatment on the physical and physicochemical properties of frozen dough. Food Chemistry, 2023; 411, 135516. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Y., Guo, X. N., & Zhu, K. X. Polymerization of wheat gluten and the changes of glutenin macropolymer (GMP) during the production of Chinese steamed bread. Food Chemistry, 2016; 201, 275-283. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Li, Y., Sun, F., Li, X., Wang, P., Sun, J., ... & He, G. Tannins improve dough mixing properties through affecting physicochemical and structural properties of wheat gluten proteins. Food Research International, 2015; 69, 64-71. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P., Lee, T. C., Xu, X., & Jin, Z. The contribution of glutenin macropolymer depolymerization to the deterioration of frozen steamed bread dough quality. Food Chemistry, 2016; 211, 27-33. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P., Chen, H., Mohanad, B., Xu, L., Ning, Y., Xu, J., ... & Xu, X. Effect of frozen storage on physicochemistry

of wheat gluten proteins: Studies on gluten-, glutenin-and gliadin-rich fractions. Food

hydrocolloids, 2014; 39, 187-194. [CrossRef]

- Lou, X., Yue, C., Luo, D., Li, P., Zhao, Y., Xu, Y., ... & Bai, Z. Effects of natural inulin on the rheological, physicochemical and structural properties of frozen dough during frozen storage and its mechanism. LWT, 2023; 114973. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., Xu, D., Zhou, H., Wu, F., & Xu, X. Rheological, microstructure and mixing behaviors of frozen dough reconstituted by wheat starch and gluten. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2022; 212, 517-526. [CrossRef]

- Mao, X., Liu, Z., Ma, J., Pang, H., & Zhang, F. Characterization of a novel β-helix antifreeze protein from the desert beetle Anatolica polita. Cryobiology, 2011; 62(2), 91-99. [CrossRef]

- Sharadanant, R., & Khan, K. Effect of hydrophilic gums on the quality of frozen dough: II. Bread characteristics. Cereal Chemistry, 2003; 80(6), 773-780. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).