1. Introduction

Estrogen is a major class of female gonad hormones, which include estrone, estradiol (E2), estriol and estetrol, which are mainly secreted by the ovary, and less by the liver, adrenal cortex and mammary gland. E2 is not only the most potent endogenous estrogen in regulating the physiological phenomena of female characteristics, it has also been found to play an extremely important role in neuroprotection in the central nervous system (CNS), neuromodulator in synaptic function and memory [1-4]. However, when women enter menopause (between the ages of 45-55 years), estrogen levels in the body drop, the estrous cycle becomes irregular and begins to taper off. Furthermore, research has also shown that women are twice as likely as men to develop late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a neurodegenerative disease [

5,

6]. Postmenopausal estrogen deficiency may contribute to benign cognitive decline and the etiology of AD in women [

7]. Young surgical menopause women (age less than 43) tended to develop cognitive decline earlier than natural menopause women, and earlier age at menopause was also associated with increased neuropathology of AD, especially neuritic plaques [

8] These observations suggest depletion of E2 in the brain may play an important role in AD development, while retaining normal brain E2 can prevent AD progression [9-11]. Furthermore, lower estrogen levels in postmenopausal women are associated with the development of dementia [

12].

Animal behavioral performance related to learning and memory formation or cognitive function is performed mainly by information integration in the hippocampus region of the brain. Pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus are responsible for the output of integrated information [

13]. Dendritic spines are widely distributed on the dendritic surface of pyramidal neurons and these dendritic spines are believed to be the site of excitatory synaptic connections [

14]. Therefore, the number of dendritic spines is closely related to the function of the hippocampus and animal behavior. Our published data have indicated that periodic fluctuations or estrogen secretion deficiency dynamically alter the spine density in pyramidal neurons of the sensorimotor cortex and hippocampal CA1 region. Such estrogen variation further affects learning and memory formation or cognitive function of animals [

2,

4]. In addition, innervation of the septo-hippocampal cholinergic system is another important factor that clearly affects the function of the hippocampus. Cholinergic fibers in the hippocampus are mainly projected from the medial septal nucleus (MS nucleus), which regulate the activity of pyramidal neurons through the transmission of acetylcholine [

15]. Our studies have also found that in rat models of AD and fetal alcohol spectrum syndrome, the function of the hippocampus is clearly associated with cholinergic transmission of septo-hippocampal projection [

16,

17]. Many studies found that E2 also directly affects the performance of the cholinergic system, such as reducing high-affinity choline uptake, choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) activity and ChAT mRNA levels in ovariectomized animals [

18,

19].

Although exogenous E2 has an associated risk of breast cancer and cardiovascular disease [

20,

21], hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is still widely used to improve the clinical symptoms of menopausal women, such as hot flushes, night sweats, mood swings, vaginal dryness, and reduced sexual drive, and could also help prevent osteoporosis [

22,

23]. HRT may also provide patients who have lost estrogen with a strategy to prevent or improve learning, memory loss, and cognitive dysfunction. Our preliminary studies have shown that dendritic spines of pyramidal neurons in sensorimotor cortex and hippocampal CA1 region are significantly decreased in ovariohysterectomy (OHE) rats which also clearly show poorer spatial learning and memory performance. These negative changes can be improved by supplementation with E2 or genistein (one of the most abundant isoflavones in soybean) [

3,

4]. This indicates that E2 or similar derivative can modulate learning and memory deficit due to loss of estrogen. Given the risk of diseases derived from exogenous E2 supplementation, we must develop another effective and safer therapeutic option.

The delivery of free E2 to the brain is the key factor in restoring recognition and memory. Hyaluronic acid-17β-Estradiol conjugate (HA-E2) is a novel hyaluronic acid (HA) conjugated with estradiol compound that can pass through blood-brain barrier (BBB) and deliver E2 to the CNS. The novelty of HA drug conjugates is that the biological polymer HA is a major component of the synaptic plasticity and neuronal extracellular micro-environment, and HA biosynthesis is related to de-novo formation of new inhibitory synapses and synaptic remodeling [

24]. Recent studies show that HA could protect and facilitate estradiol entry into brain in an effective form: (1) HA as a carrier can help estradiol cross the BBB [

25]; (2) HA-E2 can prolong E2 effects and sustain long-term activity through steric hindrance by the HA polymer to protect E2 from degradation until it slowly cleaves from the HA conjugate [

26]; (3) HA conjugated to E2 can protect the 17β-hydroxyl group of E2 from oxidation to estrone, thus reducing the risk of breast cancer and related cardiovascular disease [

20,

21].

In this study, we investigate the efficacy of HA-E2 treatment for cognitive deficit in OHE rats, the changes in pattern of cholinergic septo-hippocampal innervation and spine density in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Animals

Seventy-five female Sprague-Dawley rats, about 200 g body weight, were obtained from BioLASCO Taiwan Co., Ltd. and all procedures for the care and feeding of experimental animals were in accordance with the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Chung-Hsing University. All animals were individually caged (43 × 23 × 20 cm

3) at constant temperature (24 ± 1℃), humidity (60 ± 5%) and light-controlled room (12 h light-dark cycle) and provided with sufficient food and water. Normal rats treated with vehicle were the control group (Cont+Veh, n = 17). The surgical protocol for OHE was described previously [

3,

4] and the OHE surgical rats were divided into OHE rats treated with HA (OHE+HA, n = 11), OHE rats treated with E2 (OHE+E2, n = 23) and OHE rats treated with HA-E2 (OHE+HA-E2, n = 24), respectively. The administration of drugs is described below. Before sacrifice vaginal smears were performed on the experimental animals to determine their estrous cycles and confirm that the control animals were in proestrus stage.

2.2. Experiment schedule

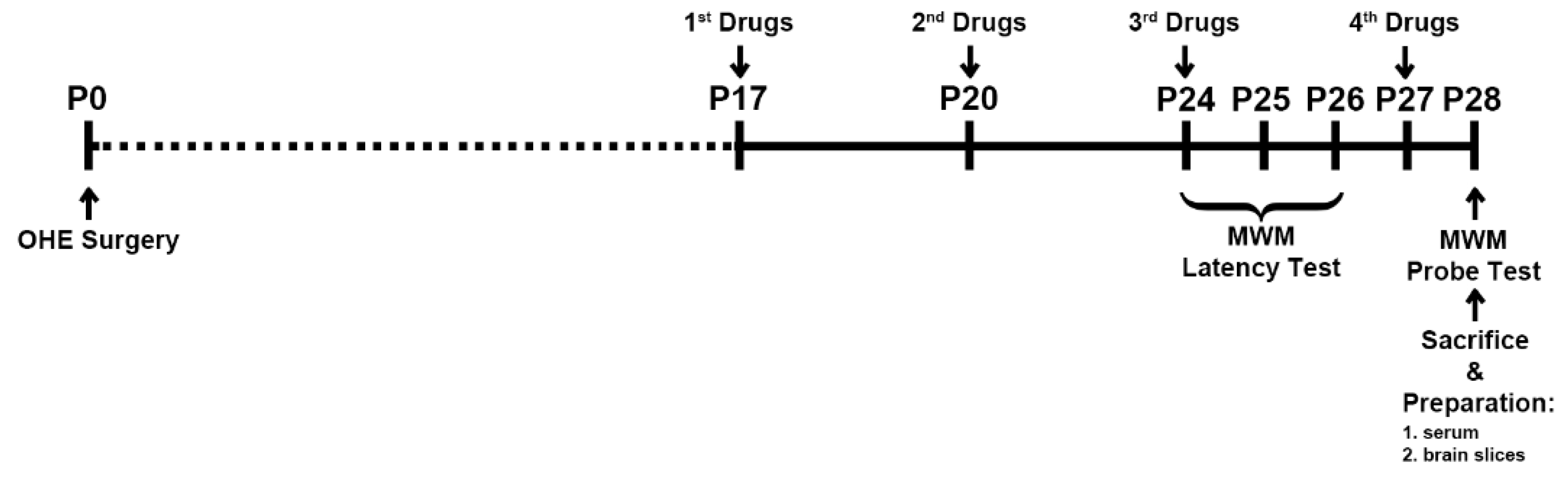

Figure 1 shows the experiment schedule. The animals underwent the OHE surgery on day 0 (P0). Animals were treated with either vehicle, HA, E2 or HA-E2 on days P17, P20, P24, and P27 according to their group. The latency trial of Morris water maze (MWM) was started on P24 and continued for three days of training. The probe trial of MWM was carried out on day P28. After this, all animals were sacrificed for subsequent histological and morphological analysis.

2.3. Drug administration

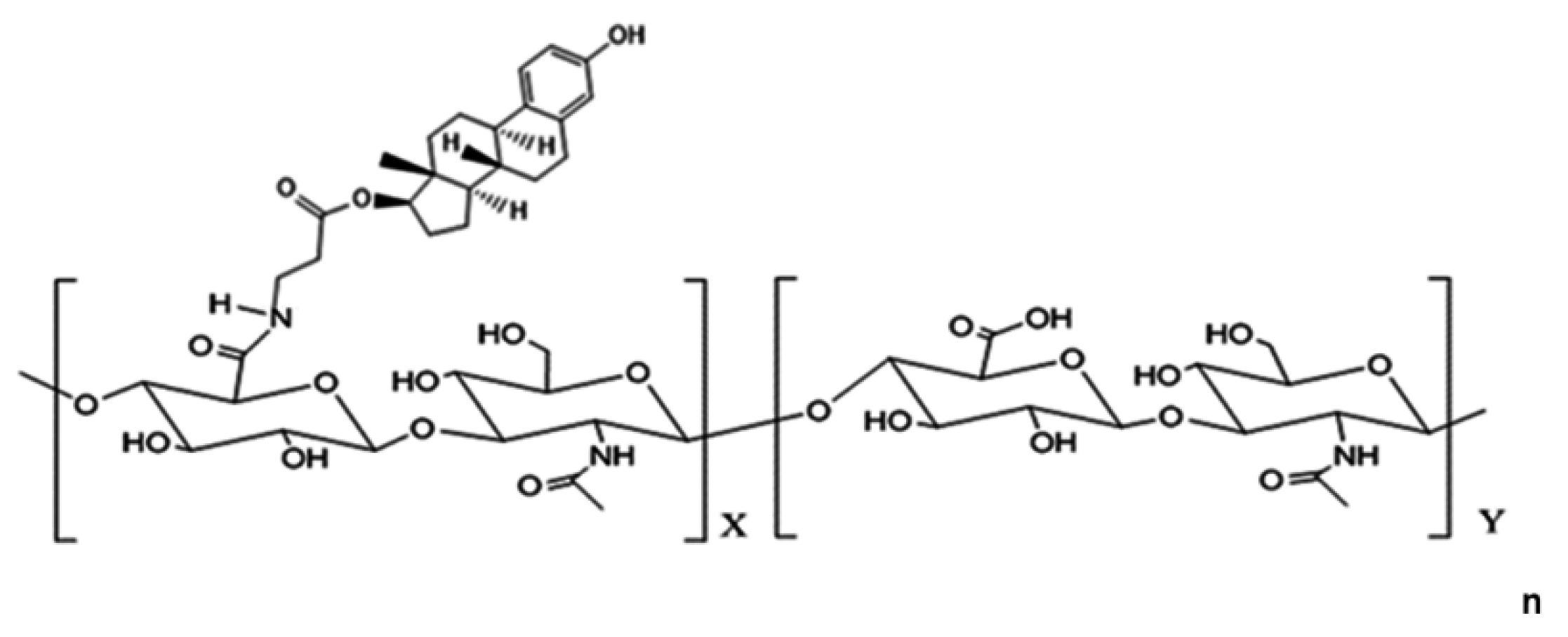

HA (molecular weight 360 kDa, Freda Biopharm) and HA-E2 was provided by Holy Stone Healthcare (Taipei, Taiwan). The structure of HA-E2 is illustrated in

Figure 2 and was confirmed by

1H NMR spectrum. In our preliminary data, we referred to previously published articles [

27] to determine the E2 dosage and evaluated the effectiveness of E2 treatment regimens at doses of 280 and 350 ng/kg, with the latter showing a significant therapeutic effect (data not shown). Similarly, we evaluated HA-E2 treatment regimens at doses of 140, 210, 280, and 350 ng/kg and found that the dose of 210 ng/kg began to have a significant therapeutic effect (data not shown). Test articles were prepared as follows. HA, 2.1 mg was dissolved in 20 mL 1X PBS and stirred for 3 hours at room temperature as stock, and then diluted with 1X PBS to a concentration of 52.5 µg/mL. 17β-estradiol, 2 mg, (E2, Sigma-Aldrich, Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in 1 mL absolute ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, Louis, MO, USA) and then diluted to 100 times in PBS as stock. Furthermore, E2 stock was diluted with 1X PBS (Sigma-Aldrich, Louis, MO, USA) to a concentration of 350 ng/mL. HA-E2, 2 mg was dissolved in 2 mL 1X PBS and stirred for 3 hours at room temperature as stock, and then diluted with 1X PBS to a concentration of 52.5 µg/mL. Animals were treated with the same volume (1 mL/kg) of vehicle (1X PBS), HA, E2 (350 ng/kg body weight) or HA-E2 (210 ng/kg E2) according to the schedule defined in

Figure 1 by intravenous injection via the tail vein at 9 am on the day of treatment.

2.4. MWM task

Behavioral tests were conducted at 10 am on test days. A modified MWM task was used to assess the spatial learning and memory of the animals [

3,

16,

17]. The maze consisted of a black circular pool 145 cm in diameter and 23 cm deep. A round transparent platform 20 cm in diameter was placed 3 cm under the water. One visual cue (star cardboard) was located at the edge of the pool, which was on the opposite side of the platform. Animal behavioral performances were recorded with a video camera and analyzed with the SMART video tracking system (SMART 3.0V, Panlab, Harvard Apparatus, Cambridge, UK). The MWM task was divided into Escape latency test and Spatial probe test.

2.4.1. Escape latency test

To assess escape latency, rats were tested with two trials per day for 3 consecutive days. Rats facing the wall of the pool were randomly placed in different quadrants of the pool. Rats were allowed to remain on the platform for 60 seconds if they located it (escaped) within 180 seconds or alternatively were placed on the platform for 60 seconds if they failed to locate the underwater platform within 180 seconds. A recovery period of 10 minutes was allowed between the two trials conducted each day. The escape latencies of the two trials each day were averaged for subsequent analyzes.

2.4.2. Spatial probe test

To run the spatial probe test, the platform in the pool was removed. A fan-shaped virtual target quadrant was defined according to the previous position of the platform. After the final escape latency task and one day of rest, the rat facing the wall of the pool was placed in the opposite quadrant of the target quadrant. The rat was allowed to swim for 30 seconds and the swimming path was analyzed.

2.5. Sacrifice and preparation of serum and brain tissues.

The rats were weighed and deeply anesthetized with 7% chloral hydrate and 0.02% xylazine (5 mL/kg body weight) and fixed on the table. Then, blood samples were taken following cardiac puncture blood collection with plasma separation tubes (lithium heparin, BD Vacutainer). The blood sample was centrifuged at 2880 g for 20 minutes, and then the serum was separated. The samples of serum were sent to the Union Reference Laboratory (Taichung, Taiwan) to measure E2 level (The detected limit of estrogen was 11.8 pg/mL. When the detected value was less than the limit, it was recorded as 0 pg/mL).

Tissue preparation for intracellular dye injection and immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was described previously [2-4,16,17]. Briefly, rats were transcardially perfused with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) for 30 minutes. Brains were carefully removed and sectioned with vibratome (Technical Products International, St. Louis, MO) into three parts: (1) 2000-µm-thick coronal slices contained MS nucleus for IHC staining; (2) two pieces of 350-μm-thick coronal slices contain hippocampus for intracellular dye injection and (3) 2000-μm-thick coronal slices contain hippocampus for IHC staining.

2.6. IHC staining

The 2000-µm-thick coronal slices for IHC staining were postfixed in 4% PFA (in 0.1 M PB) for 1 day. Postfixed thick slices were cryoprotected by 30% sucrose (in 0.1 M PB) and sectioned into 30-µm-thick sections with a cryostat (Leica Biosystems Division of Leica Microsystems, Inc., USA) for subsequent IHC staining. The cryosections were processed for IHC staining for ChAT antibody to reveal the distribution of ChAT+ neuron in MS nucleus and ChAT+ fiber in hippocampus. The sections were first incubated with 1% H2O2 (Kento chemical, co., Inc., Japan) and 0.2% Triton X-100 (Fisher scientific, Inc., USA) in 0.1 M PB for 1 h to remove endogenous peroxidase activity. Then, the sections were reacted with goat anti-ChAT (1:500, Merck Millipore, USA) for 18 h at 4°C. Biotinylated rabbit anti-goat (1:200, Vector laboratories, Inc., USA) immunoglobulin was used as the secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. They were then incubated with standard avidin-biotin HRP reagent (Vector laboratories, Inc., USA) for 1 h at room temperature. They were reacted with 0.05% 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., USA) and 0.01% H2O2 in 0.05 M Tris buffer. Reacted sections were mounted on slides, air-dried, and coverslipped with Permount (Fisher scientific, Inc., USA) for subsequent analysis.

2.7. Intracellular dye injection and immunoconversion

Methods of intracellular dye injection and immunoconversion followed previously published reports [2-4,16,17]. The 350-μm-thick coronal slices for intracellular dye injection were treated with 10-7 M 4',6-diamidino-2-phenyl-indole (DAPI, Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., USA) in 0.1 M PB to label nuclei in hippocampal CA1 region and were then placed on the stage of a fixed-stage fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan). A 20X long-working distance objective lens under filter set (390–420 nm, FT 425, LP 450) was used to monitor hippocampal CA1 pyramidal layer. 4% Lucifer yellow (LY) solution (diluted with water) was filled in a glass micropipette. A three-axial hydraulic micromanipulator (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) was used to move the glass micropipette and an intracellular amplifier (Axoclamp–IIB, Axon, Foster city, California) was used to release LY into the selected neuron via generating 3 minutes of negative current. Then, the slices were postfixed in 4% PFA (in 0.1 M PB) for 1 day. The slices were then cryoprotected by 30% sucrose (in 0.1 M PB) and sectioned into 60-µm-thick serial sections with a cryostat.

The previous serial sections were first incubated with 1% H2O2 and 1% triton X-100 in 0.1 M PB for 30 minutes to remove endogenous peroxidase activity, and then incubated with biotinylated rabbit anti-LY (1:200, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., USA) in PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., USA) for 18 h at 4°C and then incubated with standard avidin-biotin HRP reagent for 1 h at room temperature. They were reacted with 0.05% DAB and 0.01% H2O2 in 0.05 M tris buffer. Finally, reacted sections were mounted on slides, air-dried, and coverslipped with Permount for subsequent analysis.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Six sections containing MS nucleus per rat were chosen to count the ChAT+ soma area and relative IOD ratio via Image-Pro Plus 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Inc., USA). ChAT+ neurons in the MS nucleus of the above slice were circled and filter ranges (area to a range of 50-300 μm2) were set. To determine the density of dendritic spines in the hippocampal CA1 region, distal apical and distal basal dendrites of pyramidal neurons were analyzed. Five independent cells of the hippocampal CA1 region and 3 segments from each dendrite were observed by 100X objective lens and randomly counted the spine density per 10 μm.

IBM SPSS statistics 20 (International Business Machines, Co. USA) was used for statistical analysis. In order to confirm whether the data conforms to normality, all data were observed for their distribution and subjected to Shapiro-Wilk normality test. The statistical significance of the escape latency test and spatial probe test of MWM were determined with Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) of the nonparametric method followed by Dunn post hoc comparisons to find the differences between the groups, and the data were expressed as median (interquartile range, IQR = Q1-Q3). The statistical significance of the body weight, E2 level in serum, swimming distance in spatial probe test of MWM, soma area and relative IOD ratio of ChAT+ neuron in MS nucleus, spine density of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neuron were determined with one-way ANOVA of the parametric method followed by Tukey's post hoc comparisons to find the differences between groups and the data were expressed as mean ± SEM. p < 0.05 was considered significantly different.

3. Results

3.1. Exogenous HA-E2 treatment for animal body weight and serum E2 level in OHE rats

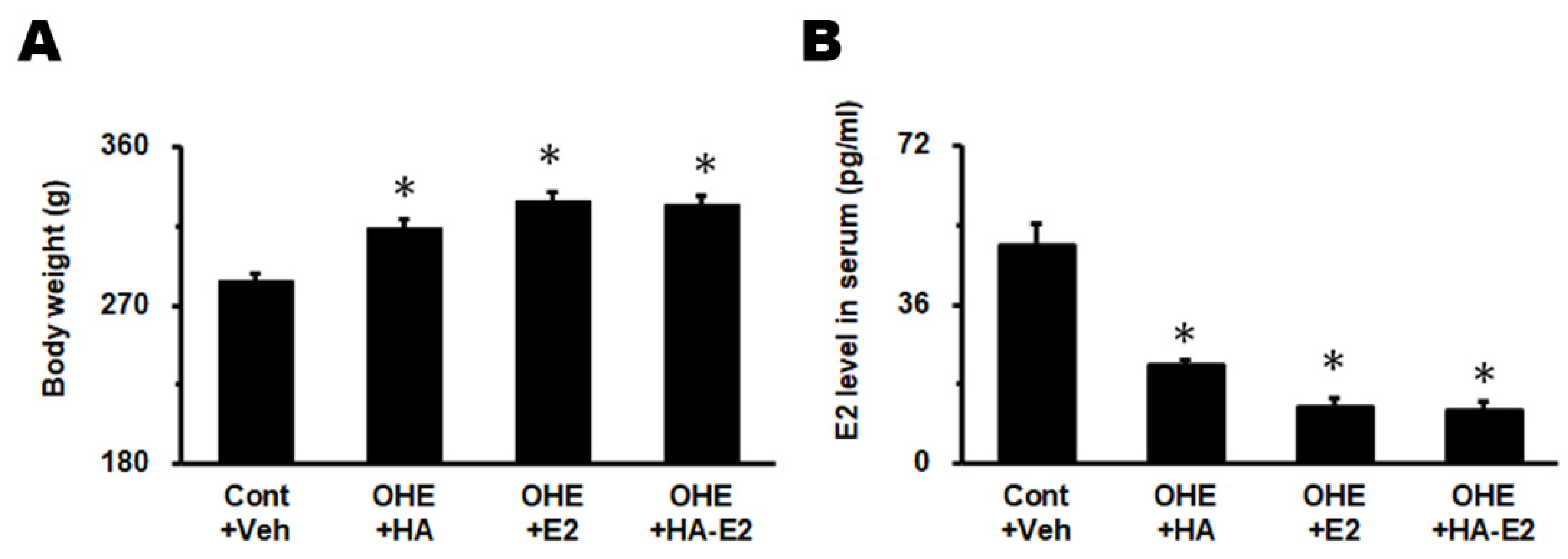

All rats survived throughout the testing period without exhibiting abnormalities related to the test article and no obvious gross pathological signs were found in the study. The experimental animals were measured for body weight and E2 level in serum before sacrificing. Body weights (

Figure 3A) in Cont+Veh, OHE+HA, OHE+E2 and OHE+HA-E2 groups were 283.4 ± 4.7, 313.4 ± 5.1, 329.2 ± 5.0 and 326.8 ± 5.5 g, respectively (F =15.29, p < 0.001). The body weight of the experimental animals after OHE surgery was significantly higher than Cont+Veh group regardless of test article treatment (p = 0.008, OHE+HA vs. Cont+Veh; p < 0.001, OHE+E2 or OHE+HA-E2 vs. Cont+Veh). The serum E2 level (

Figure 3B) in Cont+Veh, OHE+E2 and OHE+HA-E2 groups were 49.2 ± 5.1, 22.3 ± 1.2, 12.9 ± 1.9 and 11.9 ± 2.0 pg/mL, respectively (F = 35.76, p < 0.001). The serum E2 level after OHE surgery was significantly lower than Cont+Veh group (

Figure 3B, p < 0.001, OHE+HA, OHE+E2 or OHE+HA-E2 vs. Cont+Veh).

3.2. Exogenous HA-E2 treatment for spatial learning and memory in OHE rats

3.2.1. Escape latency test

We assessed the spatial learning of the animals treated with HA-E2 via escape latency test of MWM (

Figure 4A and

Table 1). Observing the swimming tracks for three consecutive days, all rats could reduce escape time and swimming distance with training days, but OHE+HA rats were unable to swim directly to the target after entering the pool even by Day 3 (

Figure 4A). There was no significant difference in swimming speed among the groups in each day (

Table 1). For the 3

rd day, there were significant increases in the escape time (p = 0.018, OHE+HA vs. Cont+Veh) and swimming distances (p = 0.010, OHE+HA vs. Cont+Veh) in OHE+HA group compared to Cont+Veh group. On 3

rd day, OHE rats treated with E2 had decreased escape time (p = 0.057, OHE+E2 vs. OHE+HA) and swimming distances (p = 0.041, OHE+E2 vs. OHE+HA), compared to OHE+HA group. OHE rats treated with HA-E2 had a significantly decreased escape time (p = 0.005, OHE+HA-E2 vs. OHE+HA) and swimming distances (p = 0.003, OHE+HA-E2 vs. OHE+HA) compared to OHE+HA rats on 3

rd day.

3.2.2. Spatial probe task

The spatial memory of the animals was investigated by MWM spatial probe test (

Figure 4B and

Table 2). The pattern of swimming track indicated that OHE+HA rats did not spend more distance in the target quadrant (p = 0.027 and 0.006 in swimming distance and distance ratio, OHE+HA vs. Cont+Veh); however, the swimming distance measured in the target quadrant was increased after OHE rats treated with E2 or HA-E2 compared to OHE+HA group (p = 0.025 and 0.043 in swimming distance and distance ratio, OHE+E2 vs. OHE+HA; p = 0.014 and 0.006 in swimming distance and distance ratio, OHE+HA-E2 vs. OHE+HA). The time that rats spend in a target quadrant was also dependent on the distance traveled, which was showed that swimming time was decreased in OHE+HA rats (p = 0.004 and 0.004 in swimming time and time ratio, OHE+HA vs. Cont+Veh), whereas the swimming time in the target quadrant was increased after OHE rats treated with E2 or HA-E2 (p = 0.009 and 0.008 in swimming time and time ratio, OHE+E2 vs. OHE+HA; p = 0.004 and 0.004 in swimming time and time ratio, OHE+HA-E2 vs. OHE+HA). Therefore, in OHE rats, the time spent swimming in the target quadrant decreased, but this effect was reversed by treatment with either E2 or HA-E2.

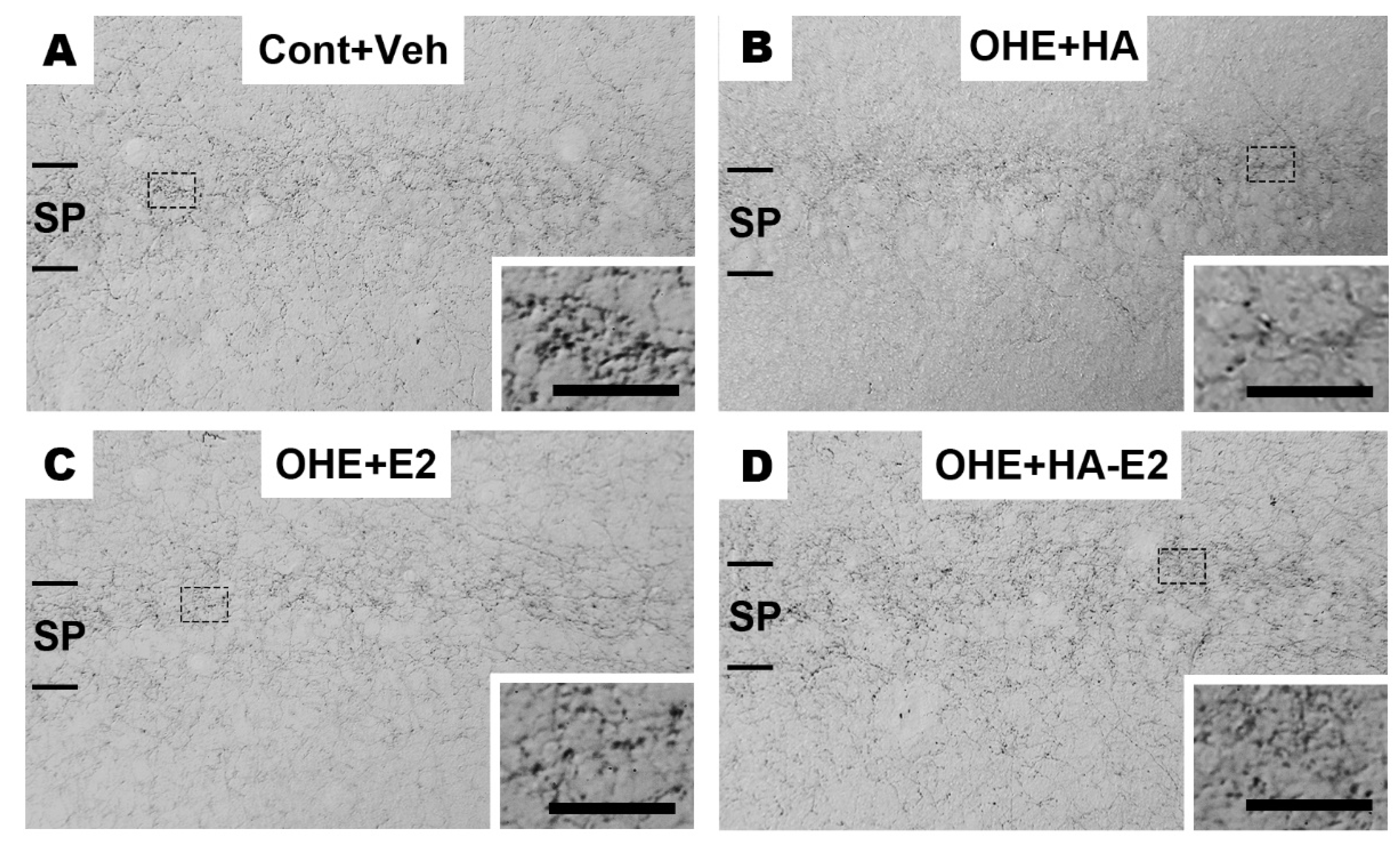

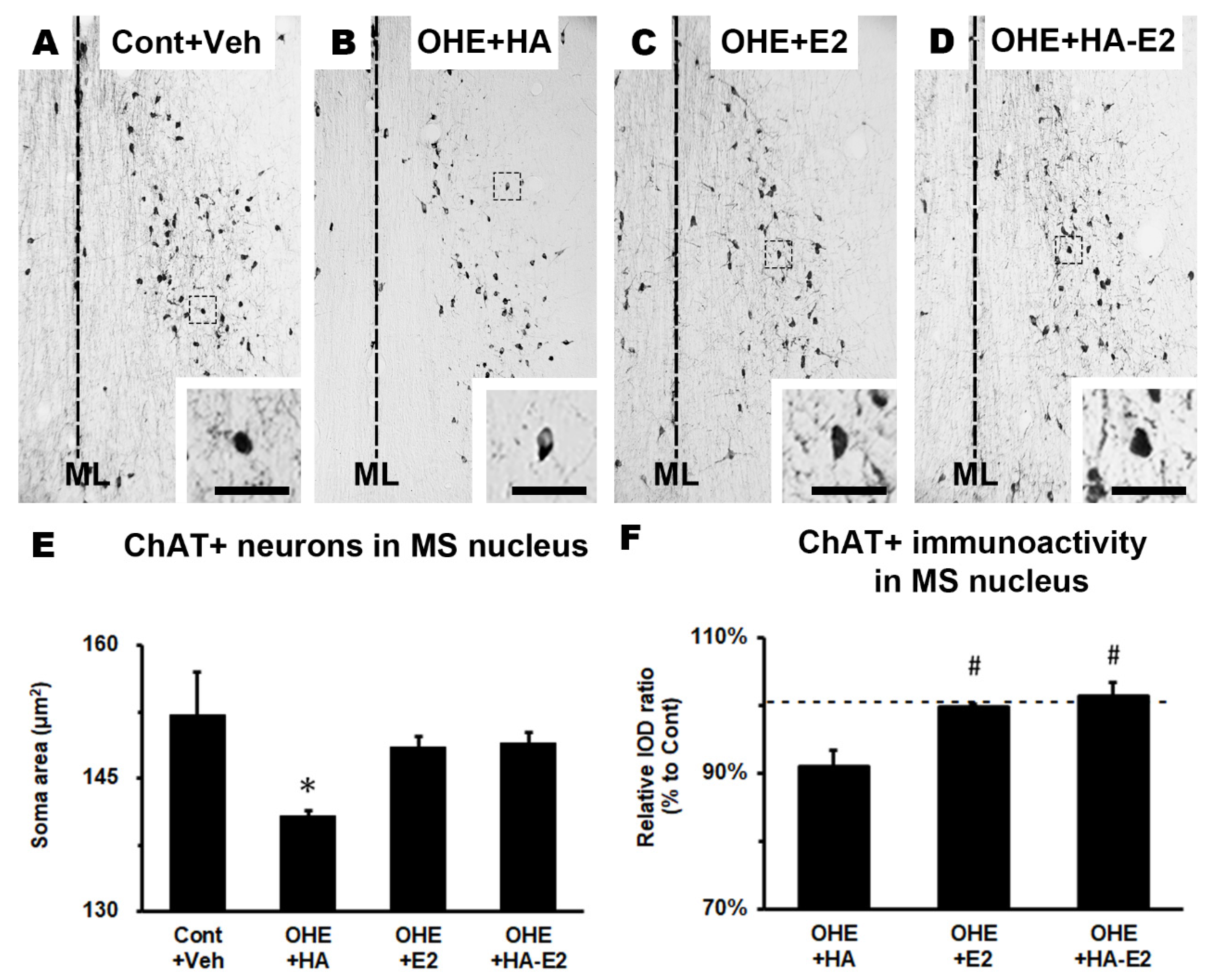

3.3. Exogenous HA-E2 treatment on cholinergic septo-hippocampal innervation in OHE rats

IHC staining was used to observe cholinergic septo-hippocampal innervation, containing ChAT+ fiber in hippocampal CA1 region (

Figure 5) and ChAT+ neurons in MS nucleus (

Figure 6). After OHE surgery, the distribution pattern of ChAT+ fiber in hippocampal CA1 region clearly decreased, and it could not be restored by HA treatment (

Figure 5B). However, in OHE rats receiving E2 or HA-E2 therapy (

Figure 5C, and D), it was more similar to Cont+Veh.

Similar results were observed in the cholinergic neuron of the MS nucleus. ChAT expression in the MS nucleus was investigated by the soma area of ChAT+ neurons and their relative IOD ratio. The soma area and relative IOD ratio (normalization to Cont+Veh group) of ChAT+ neurons in the MS nucleus are presented separately in

Figure 6E (F = 3.36, p = 0.055) and 6F (F = 8.79, p = 0.008). The soma area of ChAT+ neurons was significantly decreased in OHE+HA group (

Figure 6E; Cont+Veh: 152.1 ± 4.9 μm

2/cell, OHE+HA: 140.8 ± 0.6 μm

2/cell; p = 0.043, OHE+HA vs. Cont+Veh), whereas OHE rats treated with either E2 or HA-E2 would both recover the area, without significant differences between the E2 and HA-E2 groups (OHE+E2: 148.4 ± 1.2 μm

2/cell, OHE+HA-E2: 148.9 ± 1.3 μm

2/cell; p = 0.221, OHE+E2 vs. OHE+HA; p = 0.184, OHE+HA-E2 vs. OHE+HA). It should be noted that the relative IOD ratio of ChAT+ neuron of MS nucleus was decreased in OHE+HA group. Furthermore, the OHE rats after E2 or HA-E2 treatment could enhance the expression of ChAT (

Figure 6F; OHE+HA: 91.0 ± 2.4%, OHE+E2: 99.8 ± 0.5%, OHE+HA-E2: 101.3 ± 2.1%; p = 0.022, OHE+E2 vs. OHE+HA; p = 0.009, OHE+HA-E2 vs. OHE+HA).

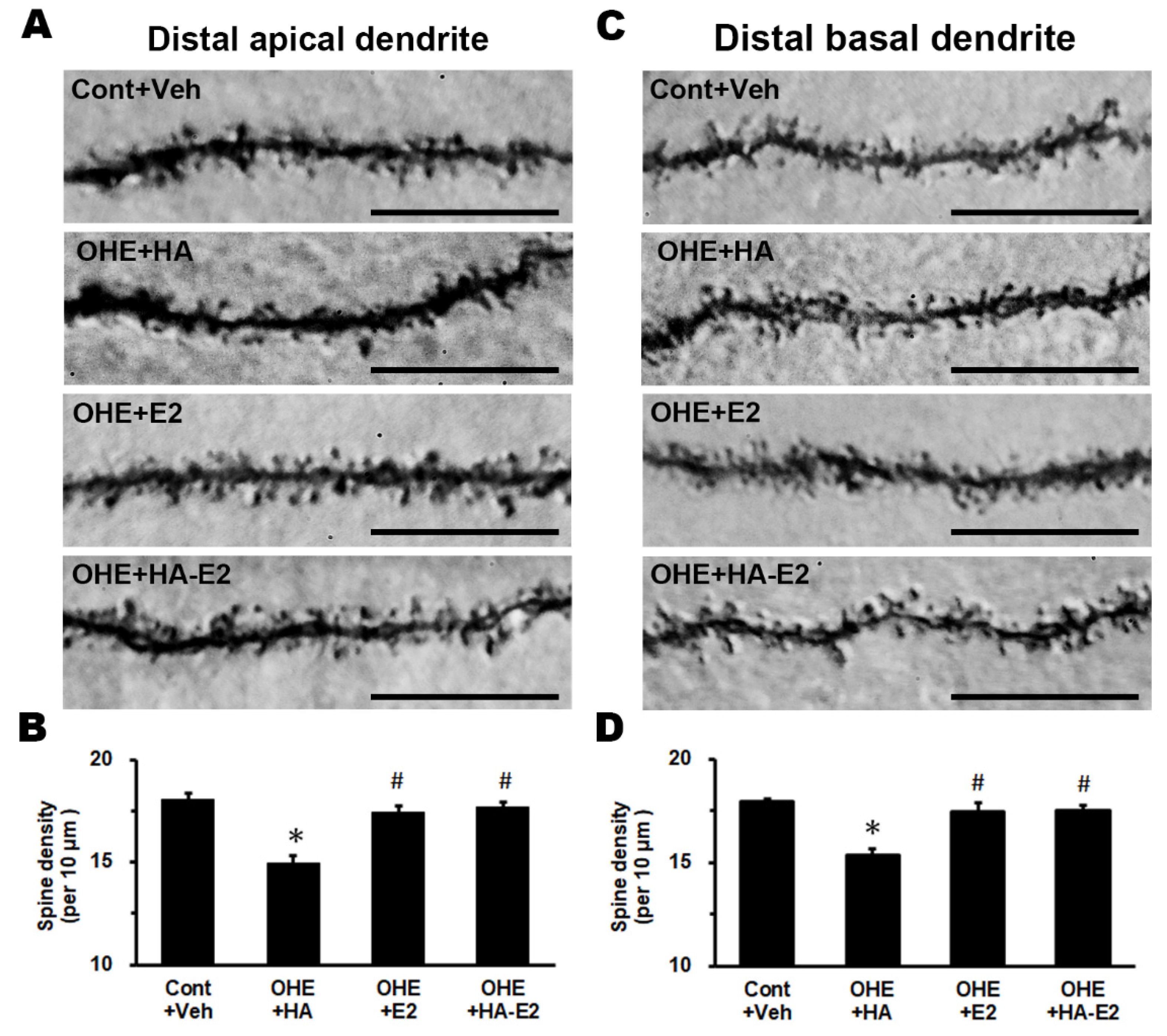

3.4. Exogenous HA-E2 on dendritic spine of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons

To investigate the relevance of estrogen to synaptic transmission in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons, we used intra-cellular dye injection to show their dendritic structures and analyzed changes in spine density (

Figure 7). The spine densities on distal apical dendrite and distal basal dendrite of CA1 pyramidal neurons are illustrated in

Figure 7B (F = 14.11, p < 0.001) and 7D (F = 21.44, p < 0.001). Even with HA treatment, E2 deficiency resulted in a 14-17% reduction in the spine density of CA1 pyramidal neurons (Cont+Veh: 18.1 ± 0.3 spines/10 μm in distal apical dendrite and 18.0 ± 0.2 spines/10μm in distal basal dendrite, OHE+HA: 14.9 ± 0.4 spines/10 μm in distal apical dendrite and 15.4 ± 0.3 spines/10 μm in distal basal dendrite; p < 0.001 in both dendrites, OHE+HA vs. Cont+Veh). OHE rats after E2 treatment showed a 14-16 % increase in the spine density of CA1 pyramidal neurons (OHE+E2: 17.4 ± 0.3 spines/10 μm in distal apical dendrite and 17.5 ± 0.5 spines/10 μm in distal basal dendrite; p = 0.002 in distal apical dendrite and p < 0.001 in distal basal dendrite, OHE+E2 vs. OHE+HA). Furthermore, HA-E2 treatment also increased the spine density of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons by 14-18% in OHE rats (OHE+HA-E2: 17.7 ± 0.2 spines/10 μm in distal apical dendrite and 17.5 ± 0.2 spines/10 μm in distal basal dendrite; p = 0.002 in distal apical dendrite and p < 0.001 in distal basal dendrite, OHE+HA-E2 vs. OHE+HA).

4. Discussion

This study used OHE surgery to induce estrogen-deficient Alzheimer’s-like disease in a rat model. Following OHE surgery and subsequent survival for 2 weeks, the animals were then treated with exogenous E2 or HA-E2 twice a week for 2 weeks. We compared the characteristics of the E2 supplemented group to evaluate the effect of HA-E2 in the treatment of animals with cognitive impairment caused by estrogen-deficiency. The main finding of this study is that HA-E2 is potent in improving ChAT expression in the MS nucleus, the pattern of ChAT+ fibers in hippocampal CA1 region, and density of dendritic spine on hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons, as well as E2. Furthermore, both HA-E2 and E2 treatment can improve spatial learning and memory deficits of OHE animals in Morris water maze. It is worth to note that the dose of HA-E2 is only approximately 60% of E2, which could be considered by two possible: (1) HA, as a vehicle, provides a higher BBB penetration rate, which can make HA-E2 enter the brain more efficiently to exert its effect [

25]; (2) HA-E2 can maintain prolonged and sustained activity by protecting E2 from degradation through steric hindrance provided by the HA polymer until it is slowly cleaved from the HA conjugate [

26].

4.1. Exogenous E2 or HA-E2 treatment did not alter serum E2 level and body weight

In this study, all rats survived to the end of the experiment and no abnormalities were observed either after the rats underwent surgery or after they were treated with E2 or HA-E2. After the rats underwent OHE surgery and survived for four weeks, it was predictable that endogenous E2 level in the serum would be depleted (below measurement limit) or maintained at a very low level, and that an accelerated increase in body weight was observed in these OHE rats. These findings were consistent with results published in the past [

3,

4,

28]. However, a small amount of E2 could be detected in the serum of some OHE rats, which could be produced by other organs, such as the liver, adrenal cortex, and mammary gland. When OHE rats received exogenous E2 or HA-E2 treatment, there were no detectable increases in blood E2 concentration before sacrifice. However, other experimental results in this study could show that E2 or HA-E2 did significantly influence other experimental parameters in OHE rats.

4.2. Exogenous E2 or HA-E2 treatment modulated cholinergic innervation

Many studies have linked E2 to changes in cholinergic neurotransmission in the brain [

18,

19,

29]. Another notable point was that studies also indicated that nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) mRNA levels appeared to increase or decrease with the presence or absence of E2, and there was a positive relationship [18,29-31]. In this study, we observed that the expression of ChAT in cholinergic neurons in the MS nucleus was significantly reduced after estrogen deficiency, decreasing by 9%, whereas these changes could be reversed by treatment with exogenous E2 or HA-E2. Some studies indicate that E2 differentially regulates the expression of neurotrophin receptors (including tropomyosin receptor kinase (Trk) A, TrkB, and p75 in basal forebrain cholinergic neurons, mediated via ERα, with an improvement in cholinergic function and survival [

18].

Estrogen receptor (ER) ERα was expressed in the cholinergic neurons of the basal forebrain and hippocampus, suggesting that cholinergic transmission might participate in modulating the spine plasticity in the hippocampal neuron [

3,

32,

33]. Recent studies also suggested that E2 could increase acetylcholine signaling in the hippocampus by stimulating G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 30 (GPR30) on cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain [

18,

34,

35]. In our study, our IHC staining showed the pattern of ChAT+ fibers in hippocampal CA1 region was reduced after estrogen deficiency, that these changes could be reversed by treatment with exogenous E2 or HA-E2 and that these changes were consistent with the MS nucleus. Research previously discovered that cholinergic depletion of the forebrain caused a decrease in complexity and spine density of CA1 pyramidal neurons, and a change in the glutamatergic synaptic transmission of the hippocampus, which in turn leads to impaired hippocampal-dependent learning and memory [16,36-38]. Most of the drugs currently approved by the FDA for AD patients, such as Donepezil, Galantamine, Rivastigmine…, increase the residence time of acetylcholine in the synaptic cleft, while HA-E2 and E2 treatment (increasing the expression of ChAT) have the same effect, and E2 has additional functions that increase the survival of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons [

39,

40].

4.3. Exogenous E2 or HA-E2 treatment repopulated the spine density of CA1 pyramidal neuron

As our previous report had shown that estrogen can modulate spine density in layer III and layer V somatosensory cortical pyramidal neurons and in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons, while exogenous E2 restored the lost dendritic spines after estrogen deficiency [2-4]. Exogenous E2 or HA-E2 significantly increased the spine density of pyramidal neurons in the hippocampal CA1 region of OHE rats, thereby increasing spatial learning ability. Notably, HA-E2 was found to be more effective than the equivalent dose of E2 in maintaining dendritic spines. In addition to the estrogen-cholinergic pathway mentioned above, some scholars have also proposed other possible mechanisms for how estrogen modulates dendritic spines on hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. The main ER on hippocampal pyramidal neurons were ERα and GPR30 [

33,

41,

42]. Many studies suggested that the expression of ERα in the hippocampus of middle-aged rats appears to decrease, while it increases after supplementation with exogenous E2 [43-45]. Although E2 appeared to act directly on pyramidal cells, due to excitatory neurotransmission required for synaptogenesis. Furthermore, research indicated that exogenous E2 also increased the expression of

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neuron, which can lead the way in generation of new dendritic spines [

41,

46]. E2 could also regulate the generation of synaptic structures through processes including, activation of NMDARs or metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), downstream phosphorylation cascades, dynamic changes in postsynaptic membrane expression of a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors (AMPARs), cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein (CREB)-mediated activation of transcription, microtubule dependent transport of mRNA, local translation of mRNA at the active synapses, and dynamic changes in actin cytoskeleton [

46,

47]. E2 also increased the expression of CREB/BDNF pathway in the hippocampus and the amygdala particularly [

48]. Up-regulation of BDNF could activate TrkB receptors and their downstream pathways to increase CREB transcription to modulate synaptic connectivity by increasing the number of synaptic structures [

49,

50]. These are obviously helpful in increasing the spine density of pyramidal neurons. While some studies suggest that the biological polymer HA may play a role in the formation and stability of inhibitory synapses and synapse remodeling [

24,

51]. Their research indicates that the HA receptor, CD44, plays a crucial role in promoting HA retention and inhibiting excitatory synapse formation by regulating Rho GTPase signaling. As a result, an increase in the level of HA between neurons results in a decrease in excitatory synapse formation, an increase in inhibitory synapse formation, and inhibition of action potential formation. Recently, HA has been extensively studied as a drug delivery vehicle for neurotrophins, including BDNF and NGF, in the treatment of CNS injuries and diseases, and has demonstrated remarkable efficacy [52-54]. However, studies that have investigated the use of HA treatment alone have not yielded sufficient benefits to animal models of neurological diseases. In our study, HA treatment alone did not improve the cognitive deficits and failed to increase dendritic spine (excitatory synapse) on hippocampal pyramidal neurons in our OHE rat model.

Based on our results, we aim to show that estrogen deficiency leads to a significant decrease in cholinergic neuron function in the basal forebrain nucleus, which can be reversed by exogenous treatment with E2 or HA-E2 treatment. Restoration of cholinergic neuron function can increase acetylcholine levels between neurons in the brain (similar to the mechanism of most FDA-approved Alzheimer's drugs), thus improving excitatory synaptic connections between pyramidal neurons (increased number of dendritic spines in pyramidal neurons) [

55]. Assuredly, we cannot rule out the possibility that E2 or HA-E2 directly act on E2 receptors in hippocampal pyramidal neurons to regulate dendritic spine formation. It is the increase in excitatory synaptic transmission between pyramidal neurons that improves animal cognitive deficits.

E2 therapy has been repeatedly shown to alleviate many symptoms caused by hypogonadism in recent years, and there is no doubt about its effectiveness. However, excessive use of E2 may put patients at risk for more severe diseases. Therefore, we are committed to developing a new approach to treat cognitive dysfunction. This study confirmed that lower dose of HA-E2 treatment had the same effective as E2 treatment in improving estrogen-deficiency-induced decreased cholinergic septo-hippocampal innervation, spine loss in CA1 pyramidal neurons, spatial learning and memory deficit. Novel compound design, using hyaluronic acid as a carrier, not only allows E2 to be released more precisely and lastingly in the brain, but also reduces the total amount of E2 administered which consequently reduces the risk of other E2 related disease in patients taking the drug. Therefore, HA-E2 has great potential as a new drug for estrogen-deficiency-induced cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.-H.C., V.S.-Y.L., C.-L.H. and J.-R.C.; Methodology, M.-H.C., H.-C.L., T.C., V.S.-Y.L., C.-L.H., T.-J.W. and J.-R.C.; Validation, M.-H.C. and H.-C.L.; Investigation, M.-H.C., H.-C.L. and T.C.; Resources, V.S.-Y.L., C.-L.H., T.-J.W. and J.-R.C.; Data Curation, M.-H.C.; Writing - Original Draft, M.-H.C.; Writing - Review & Editing, V.S.-Y.L., C.-L.H., T.-J.W. and J.-R.C.; Visualization, M.-H.C. and H.-C.L.; Supervision, J.-R.C.; Project Administration, J.-R.C.; Funding Acquisition, T.-J.W. and J.-R.C.

Funding

This work was supported by research grants from the National science and Technology Council of Taiwan to Chen, JR (MOST 109-2313-B-005-016) and grants from the NUTC to Wang, T-J (111109F) and NCHU to Chen, J-R (111D570).

Acknowledgments

We thank Holy Stone Healthcare Co., Ltd. for providing HA and HA-E2.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures for the care and feeding of experimental animals were in accordance with the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Chung-Hsing University (IACUC No. 108-036, period of Protocol: valid from 05/13/2019 to 05/13/2020).

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest with the organizations that sponsored the research.

1. Abbreviations

AD, Alzheimer’s diseases; AMPARs, a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors; BBB, blood-brain barrier; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; ChAT, choline acetyltransferase; CNS, central nervous system; CREB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein; DAB, 3,3'-diaminobenzidine; DAPI, 4',6-diamidino-2-phenyl-indole; E2, estradiol; ER, estrogen receptor; GPR30, G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 30; HA, hyaluronic acid; HA-E2, hyaluronic acid-17β-Estradiol conjugate; IHC, immunohistochemistry; LY, lucifer yellow; mGluRs, metabotropic glutamate receptors; MS nucleus, medial septal nucleus; MWM, Morris water maze; NGF, nerve growth factor; NMDARs, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors; OHE, ovariohysterectomy; one-way ANOVA, one-way analysis of variance; P0, day 0; PB, phosphate buffer; PFA, paraformaldehyde; Trk, tropomyosin receptor kinase.

References

- Choi, H.J.; Lee, A.J.; Kang, K.S.; Song, J.H.; Zhu, B.T. 4-hydroxyestrone, an endogenous estrogen metabolite, can strongly protect neuronal cells against oxidative damage. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.R.; Lim, S.H.; Chung, S.C.; Lee, Y.F.; Wang, Y.J.; Tseng, G.F.; Wang, T.J. Reproductive experience modified dendritic spines on cortical pyramidal neurons to enhance sensory perception and spatial learning in rats. Exp. Anim. 2017, 66, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.J.; Chen, J.R.; Wang, W.J.; Wang, Y.J.; Tseng, G.F. Genistein partly eases aging and estropause-induced primary cortical neuronal changes in rats. PloS One 2014, 9, e89819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.R.; Yan, Y.T.; Wang, T.J.; Chen, L.J.; Wang, Y.J.; Tseng, G.F. Gonadal hormones modulate the dendritic spine densities of primary cortical pyramidal neurons in adult female rat. Cereb. Cortex 2009, 19, 2719–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jett, S.; Malviya, N.; Schelbaum, E.; Jang, G.; Jahan, E.; Clancy, K.; Hristov, H.; Pahlajani, S.; Niotis, K.; Loeb-Zeitlin, S.; et al. Endogenous and exogenous estrogen exposures: how women's reproductive health can drive brain aging and inform alzheimer's prevention. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 831807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viña, J.; Lloret, A. Why women have more Alzheimer's disease than men: gender and mitochondrial toxicity of amyloid-beta peptide. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2010, 20 Suppl 2, S527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadesus, G.; Rolston, R.K.; Webber, K.M.; Atwood, C.S.; Bowen, R.L.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A. Menopause, estrogen, and gonadotropins in Alzheimer's disease. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2008, 45, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, R.; Secor, E.; Chibnik, L.B.; Barnes, L.L.; Schneider, J.A.; Bennett, D.A.; De Jager, P.L. Age at surgical menopause influences cognitive decline and Alzheimer pathology in older women. Neurology 2014, 82, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, V.W.; Benke, K.S.; Green, R.C.; Cupples, L.A.; Farrer, L.A. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and Alzheimer's disease risk: interaction with age. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2005, 76, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Breitner, J.C.; Whitmer, R.A.; Wang, J.; Hayden, K.; Wengreen, H.; Corcoran, C.; Tschanz, J.; Norton, M.; Munger, R.; et al. Hormone therapy and Alzheimer disease dementia: new findings from the Cache County Study. Neurology 2012, 79, 1846–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Soto, M.; Branigan, G.L.; Rodgers, K.; Brinton, R.D. Association between menopausal hormone therapy and risk of neurodegenerative diseases: Implications for precision hormone therapy. Alzheimers Dement. 2021, 7, e12174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalal, P.K.; Agarwal, M. Postmenopausal syndrome. Indian J. Psychiatry 2015, 57, S222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, J.M. Pyramidal neurons. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, R975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, M.B.; Trommald, M.; Andersen, P. An increase in dendritic spine density on hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells following spatial-learning in adult-rats suggests the formation of new synapses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1994, 91, 12673–12675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles-Grilo Ruivo, L.M.; Mellor, J.R. Cholinergic modulation of hippocampal network function. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2013, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.H.; Hong, C.L.; Wang, Y.T.; Wang, T.J.; Chen, J.R. The effect of astaxanthin treatment on the rat model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). Brain Res. Bull. 2022, 183, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.H.; Wang, T.J.; Chen, L.J.; Jiang, M.Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Tseng, G.F.; Chen, J.R. The effects of astaxanthin treatment on a rat model of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. Bull. 2021, 172, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newhouse, P.; Dumas, J. Estrogen-cholinergic interactions: Implications for cognitive aging. Horm. Behav. 2015, 74, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luine, V.N.; Renner, K.J.; McEwen, B.S. Sex-dependent differences in estrogen regulation of choline acetyltransferase are altered by neonatal treatments. Endocrinology 1986, 119, 874–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincze, B.; Kapuvári, B.; Udvarhelyi, N.; Horváth, Z.; Mátrai, Z.; Czeyda-Pommersheim, F.; Kőhalmy, K.; Kovács, J.; Boldizsár, M.; Láng, I.; et al. Serum estrone concentration, estrone sulfate/estrone ratio and BMI are associated with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and progesterone receptor status in postmenopausal primary breast cancer patients suffering invasive ductal carcinoma. Springerplus 2015, 4, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halake, K.; Lee, J. Functional hyaluronic acid conjugates based on natural polyphenols exhibit antioxidant, adhesive, gelation, and self-healing properties. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017, 54, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Kimmig, R. [The benefits and risks of hormonal replacement therapy--an update]. Gynakol. Geburtshilfliche Rundsch. 2006, 46, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.K.; Imthurn, B.; Zacharia, L.C.; Jackson, E.K. Hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease. Hypertension 2004, 44, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, A.; Sherman, L.S. Diverse roles for hyaluronan and hyaluronan receptors in the developing and adult nervous system. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curcio, M.; Cirillo, G.; Rouaen, J.R.C.; Saletta, F.; Nicoletta, F.P.; Vittorio, O.; Iemma, F. Natural polysaccharide carriers in brain delivery: challenge and perspective. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriarca, M.T.; Barbosa de Moraes, A.R.; Nader, H.B.; Petri, V.; Martins, J.R.; Gomes, R.C.; Soares, J.M., Jr. Hyaluronic acid concentration in postmenopausal facial skin after topical estradiol and genistein treatment: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial of efficacy. Menopause 2013, 20, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siiteri, P.K.; Murai, J.T.; Hammond, G.L.; Nisker, J.A.; Raymoure, W.J.; Kuhn, R.W. The serum transport of steroid hormones. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 1982, 38, 457–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wronski, T.J.; Schenck, P.A.; Cintrón, M.; Walsh, C.C. Effect of body weight on osteopenia in ovariectomized rats. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1987, 40, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, E.J.; Choi, Y.; Park, D. Improvement of cognitive function in ovariectomized rats by human neural stem cells overexpressing choline acetyltransferase via secretion of NGF and BDNF. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Meyer, E.M.; Millard, W.J.; Simpkins, J.W. Ovarian steroid deprivation results in a reversible learning impairment and compromised cholinergic function in female Sprague-Dawley rats. Brain Res. 1994, 644, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Meyer, E.M.; Simpkins, J.W. The effect of ovariectomy and estradiol replacement on brain-derived neurotrophic factor messenger ribonucleic acid expression in cortical and hippocampal brain regions of female Sprague-Dawley rats. Endocrinology 1995, 136, 2320–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shughrue, P.J.; Scrimo, P.J.; Merchenthaler, I. Estrogen binding and estrogen receptor characterization (ERalpha and ERbeta) in the cholinergic neurons of the rat basal forebrain. Neuroscience 2000, 96, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solum, D.T.; Handa, R.J. Localization of estrogen receptor alpha (ER alpha) in pyramidal neurons of the developing rat hippocampus. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 2001, 128, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, R.B.; Nelson, D.; Hammond, R. Role of GPR30 in mediating estradiol effects on acetylcholine release in the hippocampus. Horm. Behav. 2014, 66, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, R.; Nelson, D.; Gibbs, R.B. GPR30 co-localizes with cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain and enhances potassium-stimulated acetylcholine release in the hippocampus. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011, 36, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanju, P.M.; Parameshwaran, K.; Sims-Robinson, C.; Uthayathas, S.; Josephson, E.M.; Rajakumar, N.; Dhanasekaran, M.; Suppiramaniam, V. Selective cholinergic depletion in medial septum leads to impaired long term potentiation and glutamatergic synaptic currents in the hippocampus. PloS One 2012, 7, e31073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, R.T.; Gallardo, K.A.; Claytor, K.J.; Ha, D.H.; Ku, K.H.; Yu, B.P.; Lauterborn, J.C.; Wiley, R.G.; Yu, J.; Gall, C.M.; et al. Neonatal treatment with 192 IgG-saporin produces long-term forebrain cholinergic deficits and reduces dendritic branching and spine density of neocortical pyramidal neurons. Cereb. Cortex 1998, 8, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fréchette, M.; Rennie, K.; Pappas, B.A. Developmental forebrain cholinergic lesion and environmental enrichment: behaviour, CA1 cytoarchitecture and neurogenesis. Brain Res. 2009, 1252, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, S.H.; Liu, Z.; Kecojevic, A.; Merchenthaler, I.; Koliatsos, V.E. Direct, complex effects of estrogens on basal forebrain cholinergic neurons. Exp. Neurol. 2005, 194, 506–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahám, I.M.; Koszegi, Z.; Tolod-Kemp, E.; Szego, E.M. Action of estrogen on survival of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons: promoting amelioration. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34 Suppl 1, S104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.; Akama, K.; Alves, S.; Brake, W.G.; Bulloch, K.; Lee, S.; Li, C.; Yuen, G.; Milner, T.A. Tracking the estrogen receptor in neurons: Implications for estrogen-induced synapse formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001, 98, 7093–7100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, K.; Sakamoto, H.; Mori, H.; Hosokawa, K.; Kawamura, A.; Itose, M.; Nishi, M.; Prossnitz, E.R.; Kawata, M. Expression and intracellular distribution of the G protein-coupled receptor 30 in rat hippocampal formation. Neurosci. Lett. 2008, 441, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, R.D.; Sharma, K.; Nyakas, C.; Vij, U. Estrogen receptor alpha and beta immunoreactive neurons in normal adult and aged female rat hippocampus: a qualitative and quantitative study. Brain Res. 2005, 1056, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, M.M.; Fink, S.E.; Shah, R.A.; Janssen, W.G.; Hayashi, S.; Milner, T.A.; McEwen, B.S.; Morrison, J.H. Estrogen and aging affect the subcellular distribution of estrogen receptor-alpha in the hippocampus of female rats. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 3608–3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohacek, J.; Daniel, J.M. The ability of oestradiol administration to regulate protein levels of oestrogen receptor alpha in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex of middle-aged rats is altered following long-term ovarian hormone deprivation. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2009, 21, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cersosimo, M.G.; Benarroch, E.E. Estrogen actions in the nervous system: Complexity and clinical implications. Neurology 2015, 85, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargin, D.; Mercaldo, V.; Yiu, A.; Higgs, G.; Han, J.-H.; Frankland, P.; Josselyn, S. CREB regulates spine density of lateral amygdala neurons: Iimplications for memory allocation. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2013, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, H.; Cohen, R.S.; Pandey, S.C. Effects of estrogen treatment on expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and cAMP response element-binding protein expression and phosphorylation in rat amygdaloid and hippocampal structures. Neuroendocrinology 2005, 81, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galasso, C.; Orefice, I.; Pellone, P.; Cirino, P.; Miele, R.; Ianora, A.; Brunet, C.; Sansone, C. On the Neuroprotective role of astaxanthin: New perspectives? Mar. Drugs 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, W.W.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, B.Y.; Jia, H.; Xu, L.-j.; Liu, A.-l.; Du, G.-h. DL0410 ameliorates cognitive disorder in SAMP8 mice by promoting mitochondrial dynamics and the NMDAR-CREB-BDNF pathway. Acta. Pharmacol. Sin. 2021, 42, 1055–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochlamazashvili, G.; Henneberger, C.; Bukalo, O.; Dvoretskova, E.; Senkov, O.; Lievens, P.M.; Westenbroek, R.; Engel, A.K.; Catterall, W.A.; Rusakov, D.A.; et al. The extracellular matrix molecule hyaluronic acid regulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity by modulating postsynaptic L-type Ca(2+) channels. Neuron 2010, 67, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, D.; Ren, Y.; Guo, S.; Li, J.; Ma, S.; Yao, M.; Guan, F. Injectable hyaluronic acid hydrogel loaded with BMSC and NGF for traumatic brain injury treatment. Mater. Today Bio. 2022, 13, 100201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djoudi, A.; Molina-Peña, R.; Ferreira, N.; Ottonelli, I.; Tosi, G.; Garcion, E.; Boury, F. Hyaluronic acid scaffolds for loco-regional therapy in nervous system related disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, D.J.; Nguyen, C.; Chun, H.N.; I, L.L.; Chiu, A.S.; Machnicki, M.; Zarembinski, T.I.; Carmichael, S.T. Hydrogel-delivered brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes tissue repair and recovery after stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017, 37, 1030–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherren, N.; Pappas, B.A. Selective acetylcholine and dopamine lesions in neonatal rats produce distinct patterns of cortical dendritic atrophy in adulthood. Neuroscience 2005, 136, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Experiment design Experimental schedule for ovariohysterectomy (OHE) surgery, test article administration and behavioral assessment. The OHE surgery was performed on day 0 (P0). MWM, Morris water maze.

Figure 1.

Experiment design Experimental schedule for ovariohysterectomy (OHE) surgery, test article administration and behavioral assessment. The OHE surgery was performed on day 0 (P0). MWM, Morris water maze.

Figure 2.

Structure of hyaluronic acid-17β-Estradiol conjugate (HA-E2) HA-E2 is a conjugate of the biological polymer HA in its sodium salt form, sodium hyaluronate and E2. X = number of hyaluronate carboxyl groups substituted with estradiol; Y = number of unsubstituted hyaluronate disaccharides.

Figure 2.

Structure of hyaluronic acid-17β-Estradiol conjugate (HA-E2) HA-E2 is a conjugate of the biological polymer HA in its sodium salt form, sodium hyaluronate and E2. X = number of hyaluronate carboxyl groups substituted with estradiol; Y = number of unsubstituted hyaluronate disaccharides.

Figure 3.

Body weight and E2 level in serum The body weight and E2 level in serum were analyzed in A and B, respectively. The animal numbers were as follows: 17 in Cont+Veh, 11 in OHE+HA, 23 in OHE+E2, and 24 in OHE+HA-E2. *, p < 0.05 between the marked and Cont+Veh.

Figure 3.

Body weight and E2 level in serum The body weight and E2 level in serum were analyzed in A and B, respectively. The animal numbers were as follows: 17 in Cont+Veh, 11 in OHE+HA, 23 in OHE+E2, and 24 in OHE+HA-E2. *, p < 0.05 between the marked and Cont+Veh.

Figure 4.

The swimming tracks of MWM task The swimming tracks of the MWM latency test for three consecutive days and probe test were shown in A and B. Bar = 40 cm in A and B.

Figure 4.

The swimming tracks of MWM task The swimming tracks of the MWM latency test for three consecutive days and probe test were shown in A and B. Bar = 40 cm in A and B.

Figure 5.

The distribution pattern of choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)+ fibers in hippocampal CA1 region Micrographs of the ChAT+ fibers in hippocampal CA1 region of the four groups were illustrated in A-D. The inset shows a higher magnification view of each micrograph. SP, stratum pyramidale. Bar = 100 µm for all micrographs; 25 µm for inserts.

Figure 5.

The distribution pattern of choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)+ fibers in hippocampal CA1 region Micrographs of the ChAT+ fibers in hippocampal CA1 region of the four groups were illustrated in A-D. The inset shows a higher magnification view of each micrograph. SP, stratum pyramidale. Bar = 100 µm for all micrographs; 25 µm for inserts.

Figure 6.

The expression of ChAT in the MS nucleus Micrographs of the ChAT+ neurons in MS nucleus of the four groups were illustrated in A-D. The soma area and relative IOD ratio of ChAT+ neurons in the MS nucleus were analyzed in E and F, respectively. The number of animals in each group was 4. *, p < 0.05 between the marked and Cont+Veh; #, p < 0.05 between the marked and OHE+HA. ML, midline. Bar = 200 µm for all micrographs; 50 µm for inserts. Dotted lines in F indicated 100%.

Figure 6.

The expression of ChAT in the MS nucleus Micrographs of the ChAT+ neurons in MS nucleus of the four groups were illustrated in A-D. The soma area and relative IOD ratio of ChAT+ neurons in the MS nucleus were analyzed in E and F, respectively. The number of animals in each group was 4. *, p < 0.05 between the marked and Cont+Veh; #, p < 0.05 between the marked and OHE+HA. ML, midline. Bar = 200 µm for all micrographs; 50 µm for inserts. Dotted lines in F indicated 100%.

Figure 7.

The spine density of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons Representative micrographs of the distal apical dendrites (A) and distal basal dendrites (C) of the hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons from each group were illustrated. The number of animals in each group was 4. Spine density per 10 μm of distal apical and distal basal dendrites was analyzed and plotted individually in B and D. *, p < 0.05 between the marked and Cont+Veh; #, p < 0.05 between the marked and OHE+HA. Bar = 10 µm for all micrographs.

Figure 7.

The spine density of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons Representative micrographs of the distal apical dendrites (A) and distal basal dendrites (C) of the hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons from each group were illustrated. The number of animals in each group was 4. Spine density per 10 μm of distal apical and distal basal dendrites was analyzed and plotted individually in B and D. *, p < 0.05 between the marked and Cont+Veh; #, p < 0.05 between the marked and OHE+HA. Bar = 10 µm for all micrographs.

Table 1.

Behavioral performance of the Morris water maze (MWM) latency test.

Table 1.

Behavioral performance of the Morris water maze (MWM) latency test.

| |

Groups |

| Con+Veh |

OHE+HA |

OHE+E2 |

OHE+HA-E2 |

| Animal numbers |

17 |

11 |

23 |

24 |

| Escape latency (second) |

| Day1 (p = 0.172) |

62.9 (IQR = 41.4-77.5) |

60.1 (IQR = 25.3-78.6) |

40.5 (IQR = 22.3-73.9) |

34.0 (IQR = 20.2-58.6) |

| Day2 (p = 0.210) |

8.7 (IQR = 5.2-15.3) |

9.4 (IQR = 7.2-22.9) |

16.5 (IQR = 6.0-22.2) |

9.6 (IQR = 6.2-27.1) |

| Day3 (p = 0.007) |

6.6 (IQR = 5.0-10.1) |

11.6 (IQR = 10.9-21.9)*

|

7.7 (IQR = 5.1-10.8) |

6.0 (IQR = 4.4-9.4)#

|

| Swimming distance (meter) |

| Day1 (p = 0.170) |

11.6 (IQR = 8.5-14.0) |

11.5 (IQR = 4.9-16.2) |

8.2 (IQR = 4.4-13.4) |

6.8 (IQR = 4.4-11.7) |

| Day2 (p = 0.257) |

1.6 (IQR = 1.0-2.5) |

2.4 (IQR = 1.4-5.5) |

3.7 (IQR = 1.2-4.9) |

2.0 (IQR = 1.3-5.4) |

| Day3 (p = 0.004) |

1.2 (IQR = 0.9-1.7) |

2.9 (IQR = 2.0-4.1)*

|

1.5 (IQR = 1.0-2.4) #

|

1.2 (IQR = 0.9-1.7)#

|

| Swimming speed (cm/s) |

| Day1 (p = 0.811) |

19.2 (IQR = 16.8-21.2) |

19.6 (IQR = 18.9-21.7) |

20.0 (IQR = 17.9-21.1) |

19.4 (IQR = 17.7-21.9) |

| Day2 (p = 0.711) |

21.9 (IQR = 18.5-23.9) |

22.2 (IQR = 19.3-25.4) |

20.0 (IQR = 18.2-24.3) |

21.0 (IQR = 21.0-22.9) |

| Day3 (p = 0.728) |

19.2 (IQR = 16.8-23.2) |

20.4 (IQR = 18.5-23.0) |

20.9 (IQR = 18.3-24.5) |

19.3 (IQR = 17.4-23.6) |

Table 2.

Behavioral performance of the Morris water maze (MWM) probe test.

Table 2.

Behavioral performance of the Morris water maze (MWM) probe test.

| |

Groups |

| Con+Veh |

OHE+HA |

OHE+E2 |

OHE+HA-E2 |

| Animal numbers |

17 |

11 |

23 |

24 |

| Swimming distance in target quadrant |

| Distance value (meter) (p = 0.011) |

1.8 (IQR = 1.6-2.3) |

1.3 (IQR = 0.8-1.4)*

|

1.9 (IQR = 1.3-2.4)#

|

1.9 (IQR = 1.4-2.3)#

|

| Distance ratio (%) (p = 0.006) |

31.1 (IQR = 28.3-41.4) |

23.8 (IQR = 17.0-25.9)*

|

31.3 (IQR = 21.1-39.8)#

|

32.3 (IQR = 24.0-39.4)#

|

| Swimming time in target quadrant |

| Time value (second) (p = 0.002) |

9.4 (IQR = 8.0-13.1) |

5.6 (IQR = 3.9-8.0)*

|

9.6 (IQR = 6.4-13.5)#

|

10.1 (IQR = 7.2-12.9)#

|

| Time ratio (%) (p = 0.002) |

31.2 (IQR = 26.7-43.6) |

18.7 (IQR = 13.1-26.8)*

|

31.9 (IQR = 21.3-45.0)#

|

33.7 (IQR = 24.1-43.1)#

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).