Submitted:

28 September 2023

Posted:

03 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Breaking down the complexity – three principles to protect the climate and promote health

3. Examples for common domains of health promotion and climate protection

4. From policy to practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. COP26 special report on climate change and health: the health argument for climate action. Geneva: World Health Organization 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Prüss-Ustün, A.; Wolf, J.; Corvalán, C.; Bos, R.; Neira, M. Preventing disease through healthy environments: a global assessment of the burden of disease from environmental risks. Geneva: World Health Organization 2016. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565196 (accessed on 25 09 2023).

- World Health Organization. Geneva Charter for Well-Being. Geneva: World Health Organization 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/the-geneva-charter-for-well-being (accessed on 25 09 2023).

- Romanello, M.; Di Napoli, C.; Drummond, P.C.; et al. The 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels. Lancet 2021, 397, 129–170.

- United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development-17981 (accessed on 25 09 2023).

- World Health Organization. Fast Facts on Climate Change and Health. Technical Document, Geneva: World Health Organization, 8 Sep 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/fast-facts-on-climate-change-and-health (accessed on 25 09 2023).

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; de Souza Dias, B.F.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P.; et al. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation—Lancet Commission on planetary health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. Working on a warmer planet. The impact of heat stress on labour productivity and decent work. Geneva: International Labour Organization. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_711919.pdf (accessed on 25 09 2023).

- World Health Organization. Achieving well-being. A global framework for integrating well-being into public health utilizing a health promotion approach. WHA 76, Geneva: World Health Organization 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/wha-76---achieving-well-being--a-global-framework-for-integrating-well-being-into-public-health-utilizing-a-health-promotion-approach (accessed on 25 09 2023).

- World Health Organization. The Ottawa charter for health promotion. Geneva: World Health Organization 1987. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WH-1987 (accessed on 25 09 2023).

- Lee, I.M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lobelo, F.; Puska, P.; Blair, S.N.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012, 380, 219–229. [CrossRef]

- Kardan, O.; Gozdyra, P.; Misic, B.; Moola, F.; Palmer, L.J.; Paus, T.; Berman, M.G. Neighborhood greenspace and health in a large urban center. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11610. [CrossRef]

- Gascon, M.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Martínez, D.; Dadvand, P.; Rojas-Rueda, D.; Plasència, A.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Residential green spaces and mortality: A systematic review. Environ. Int. 2016, 86, 60–67. [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change cobenefits of dietary change. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 4146–4151. [CrossRef]

- Borowy, I. Defining Sustainable Development: the World Commission on Environment and Development (Brundtland Commission). London: Routledge, 2013.

- Moore, J.E.; Mascarenhas, A.; Bain, J.; Straus, S.E. Developing a comprehensive definition of sustainability. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Bodkin, A.; Hakimi, S. Sustainable by design: a systematic review of factors for health promotion program sustainability. BMC Public Heal. 2020, 20, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C. Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change.. Psychotherapy 1982, 19, 276–288. [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, G.; Whitehead, M. Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Stockholm, Sweden: Institute for Futures Studies, 1991.

- Gnadinger, T. Health policy brief: The relative contribution of multiple determinants to health outcomes. Health Affairs Blog, 22 August 2014, Accessible at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20140822.040952/full/ (accessed on 25 09 2023).

- Hood, C.M.; Gennuso, K.P.; Swain, G. R.; Catlin, B.B. County health rankings: Relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2016 50, 129–135. [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M.; Allen, J.; Bell, R.; Bloomer, E.; Goldblatt, P.; Consortium for the European Review of Social Determinants of Health and the Health Divide. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet 2012, 380, 1011-1029. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.; Adger, W.N.; Lorenzoni, I.; Abrahamson, V.; Raine, R. Social capital, individual responses to heat waves and climate change adaptation: An empirical study of two UK cities. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 44–52. [CrossRef]

- Belay, D.; Fekadu, G. Influence of social capital in adopting climate change adaptation strategies: empirical evidence from rural areas of Ambo district in Ethiopia. Clim. Dev. 2021, 13, 857–868. [CrossRef]

- Saptutyningsih, E.; Diswandi, D.; Jaung, W. Does social capital matter in climate change adaptation? A lesson from agricultural sector in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Land Use Policy 2019, 95, 104189. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Shanghai declaration on promoting health in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Ninth Global Conference on Health Promotion, Shanghai, 21–24 November 2016. Geneva: World Health Organization 2016. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-PND-17.5 (accessed on 25 09 2023).

- Ferrer, L. Engaging patients, carers and communities for the provision of coordinated/integrated health services: Strategies and tools. Working Document. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe 2015.

- Stein, K.V.; Amelung, V.E. Refocussing Care - What Does People-Centredness Mean? In Handbook Integrated Care. Amelung, V.E.; Stein, K.V.; Suter, E.; Goodwin, N.; Nolte, E.; Balicer, R., Eds.; Springer Nature, 2021.

- World Health Organization. Framework on integrated, people-centred health services. Report by the Secretariat, 69th World Health Assembly. Geneva: World Health Organisation 2016.

- van Ede, A.F.T.M.; Minderhout, R.N.; Stein, K.V.; Bruijnzeels, M.A. How to successfully implement population health management: a scoping review. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Steenkamer, B.M.; Drewes, H.W.; Heijink, R.; Baan, C.A.; Struijs, J.N.; Msc; D, P.; Slabaugh, S.L.; Shah, M.; Zack, M.; et al. Defining Population Health Management: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Popul. Heal. Manag. 2017, 20, 74–85. [CrossRef]

- Chastonay, P.; Zybach, U.; Simos, J.; Mattig, T. Climate change: an opportunity for health promotion practitioners? Int J Public Health. 2015, 60, 763-764. [CrossRef]

- OECD. Adult health literacy. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/education/innovation-education/adultliteracy.htm (accessed on 25 09 2023).

- Nutbeam, D.; Muscat, D.M. Health Promotion Glossary 2021. Heal. Promot. Int. 2021, 36, 1578–1598. [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D.; Lloyd, J.E. Understanding and Responding to Health Literacy as a Social Determinant of Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 159–173. [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D.; McGill, B.; Premkumar, P. Improving health literacy in community populations: A review of progress. Health Promot. Int. 2018, 33, 901–911. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Global Change Research Program. Climate Literacy: The Essential Principles of Climate Science. Washigton DC 2009. Available at: https://downloads.globalchange.gov/Literacy/climate_literacy_highres_english.pdf (accessed on 25 09 2023).

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling The Mystery of Health - How People Manage Stress and Stay Well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1987.

- Frumkin, H.; Hess, J.; Luber, G.; Malilay, J.; McGeehin, M. Climate Change: The Public Health Response. Am. J. Public Heal. 2008, 98, 435–445. [CrossRef]

- Limaye, V.S.; Grabow, M.L.; Stull, V.J.; Patz, J.A. Developing A Definition Of Climate And Health Literacy: Study seeks to develop a definition of climate and health literacy. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020, 39, 2182-2188. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of health and Human Services. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/PAG_Advisory_Committee_Report.pdf (accessed on 25 09 2023).

- Leyk, D. Health Risks and Interventions in Exertional Heat Stress. Dtsch. Aerzteblatt Online 2019, 116, 537–+. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, J.W.; Kark, J.A.; Karnei, K.; Sanborn, J.S.; Gastaldo, E.; Burr, P.; Wenger, C.B. Risk factors predicting exertional heat illness in male Marine Corps recruits. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1996, 28, 939–944. [CrossRef]

- Reis, C.; Lopes, A. Evaluating the Cooling Potential of Urban Green Spaces to Tackle Urban Climate Change in Lisbon. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2480. [CrossRef]

- Dorner, T.E.; Haider, S.; Lackinger, C.; Kapan, A.; Titze, S. Determinants of Exercise, Fulfilling the Recommendations for Aerobic Physical Activity and Health Status: Results of a Correlation Study in the Federal States of Austria. Gesundheitswesen 2020, 82, S207-S216.. [CrossRef]

- Obradovich, N.; Fowler, J.H. Climate change may alter human physical activity patterns. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2017, 1. [CrossRef]

- Frühauf, A.; Niedermeier, M.; Kopp, M. Intention to Engage in Winter Sport in Climate Change Affected Environments. Front. Public Heal. 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Omar, K.; Gelius, P.; Messing, S. Physical activity promotion in the age of climate change. F1000Res. 2020, 9, 349. [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Clark, M. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature 2014, 515, 518–522. [CrossRef]

- Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 2018, 360, 987–992. [CrossRef]

- Hayek, M.N.; Harwatt, H.; Ripple, W.J.; Mueller, N.D. The carbon opportunity cost of animal-sourced food production on land. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 4, 21–24. [CrossRef]

- FAO. One health. Available at: https://www.fao.org/one-health/en (accessed on 25 09 2023).

- Wallace, T.C.; Bailey, R.L.; Blumberg, J.B.; Burton-Freeman, B.; Chen, C.-Y.O.; Crowe-White, K.M.; Drewnowski, A.; Hooshmand, S.; Johnson, E.; Lewis, R.; et al. Fruits, vegetables, and health: A comprehensive narrative, umbrella review of the science and recommendations for enhanced public policy to improve intake. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2174–2211. [CrossRef]

- Angelino, D.; Godos, J.; Ghelfi, F.; Tieri, M.; Titta, L.; Lafranconi, A.; Marventano, S.; Alonzo, E.; Gambera, A.; Sciacca, S.; et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and health outcomes: an umbrella review of observational studies. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 70, 652–667. [CrossRef]

- Fanzo, J.; Rudie, C.; Sigman, I.; Grinspoon, S.; Benton, T. G.; Brown, M.E.; Covic, N.; Fitch, K.; Golden, C.D.; Grace, D.; Hivert, M.F.; Huybers, P.; Jaacks, L.M.; Masters, W.A.; Nisbett, N.; Richardson, R.A.; Singleton, C.R.; Webb, P.; Willett, W.C. Sustainable food systems and nutrition in the 21st century: a report from the 22nd annual Harvard Nutrition Obesity Symposium. Am J Clin Nutr. 2022, 115, 18-33. [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, S.J.; Campbell, B.M.; Ingram, J.S.I. Climate Change and Food Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 195–222. [CrossRef]

- Duchin, F. Sustainable Consumption of Food: A Framework for Analyzing Scenarios about Changes in Diets. J. Ind. Ecol. 2005, 9, 99–114. [CrossRef]

- Stehfest, E. Food choices for health and planet. Nature 2014, 515, 501–502. [CrossRef]

- Salm, L.; Nisbett, N.; Cramer, L.; Gillespie, S.; Thornton, P. How climate change interacts with inequity to affect nutrition. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Binns, C.W.; Lee, M.K.; Maycock, B.; Torheim, L.E.; Nanishi, K.; Duong, D.T.T. Climate Change, Food Supply, and Dietary Guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021, 42, 233-255. [CrossRef]

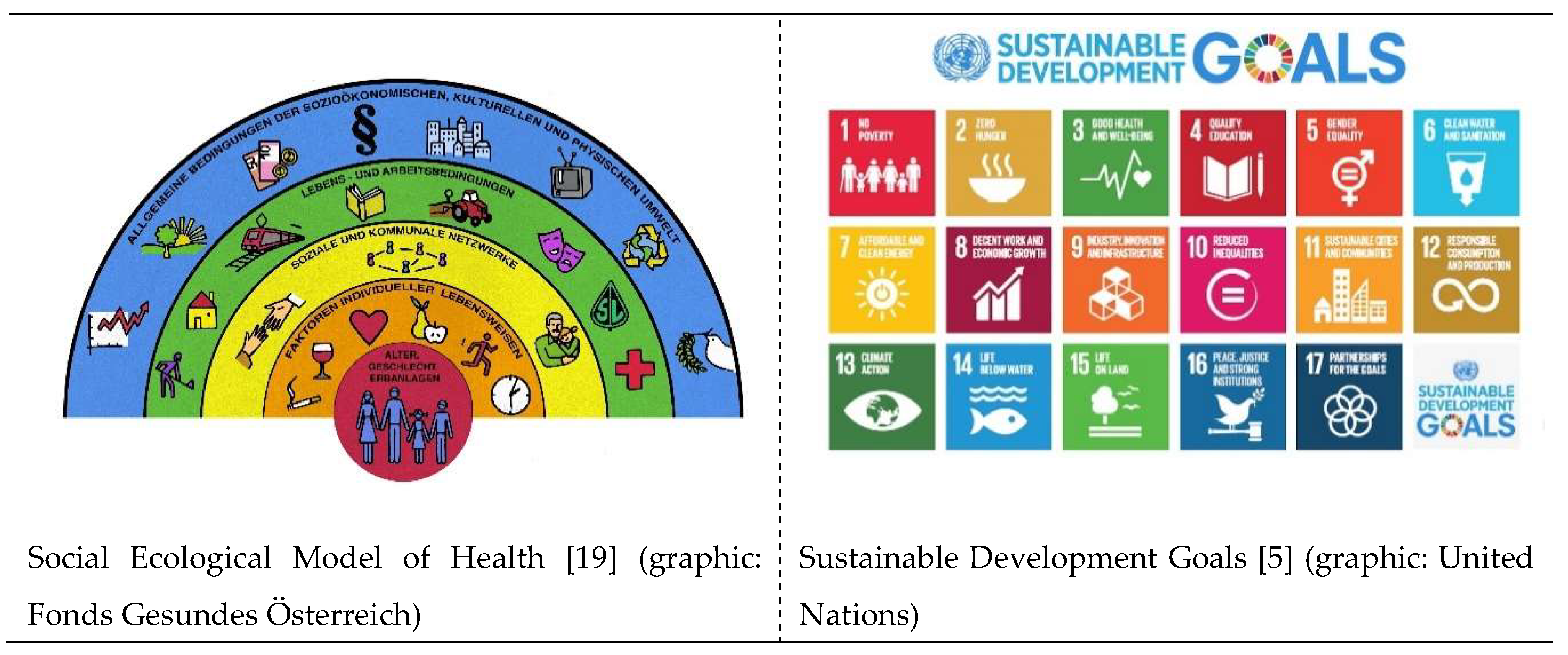

| SEM1 | SDG2 |

|---|---|

| Environmental conditions | Affordable and clean energy (7), sustainable cities and communities (11), climate action (13), life below water (14), life on land (15) |

| Agriculture and food production | Zero hunger (2), responsible consumption and production (12) |

| Education | Quality education (4) |

| Work environment | Decent work and economic growth (8) |

| Unemployment | No poverty (1) |

| Water and sanitation | Clean water and sanitation (6) |

| Health care services | Good health and wellbeing (3) |

| Social and community networks | Social and community networks |

| Sex | Gender equality (5) |

| Conditional factors | Industry innovation and infrastructure (9), reduced inequalities (10), peace, justice and strong institutions (16) |

| Sustainability | Determinants | Individual and community approaches |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Literacy | Adaptation of the dimensions of the sense of coherence, as a prerequisite for salutogenesis (comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness) can also be seen as a prerequisite for sustainability in the genesis of climate protection. | Social determinants, especially education play a key part in the levels of health and climate literacy. Easy access to evidence-based information in lay language is another important determinant. Facilitating these levers through active policies in education and health and climate promotion can mitigate negative impact of determinants. | Address individuals, patients, health professionals and the whole society to increase health literacy and climate literacy. Furthermore, the people, patients and the public must be seen as important and equal partners for health promotion and climate protection. Including comprehensive education on health and climate from kindergarden, continuing to geriatric care, would establish a baseline understanding across society. |

| Physical activity | Bottom-up instead of top-down approaches and orientation on individual stages of change can promote a change in physical activity behavior towards sustainable, active mobility. | The orientation of policies and strategies towards social, economic, cultural, individual and health and fitness-related determinants is an important prerequisite for the promotion of active mobility. |

Encourage individuals towards physically active transportation as alternative for daily distances and create the conditions for it like green spaces and a traffic system, which is safe and inviting for physically active transportation. |

| Nutrition and dietary habits | A sustainable change and maintenance of healthy eating habits is very difficult for many people. The best results can be achieved by considering all established pillars of health promotion (empowerment, participation, orientation towards determinants, personal needs and believes, and stages of change, etc.). | Social, economic, individual and cultural determinants of eating habits must be taken into account for a healthy and climate-friendly change in diet. | Develop sustainable nutrition guidelines for healthy nutrition with focus on local, organic, and plant-based food and communicate them to individuals, to stakeholders and the public. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).