Submitted:

28 September 2023

Posted:

28 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Evaluation framework of adaptation measures for urban heat island

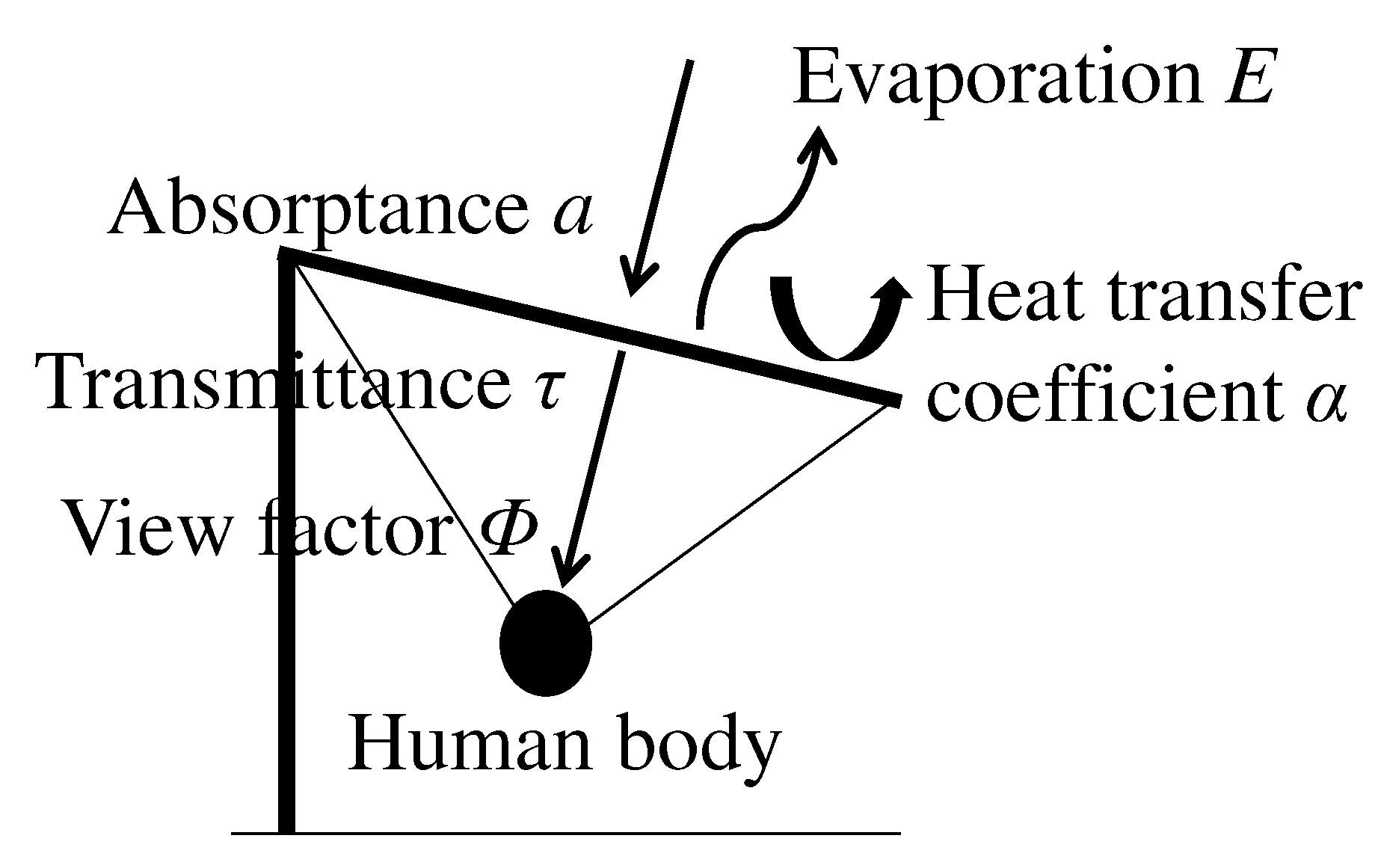

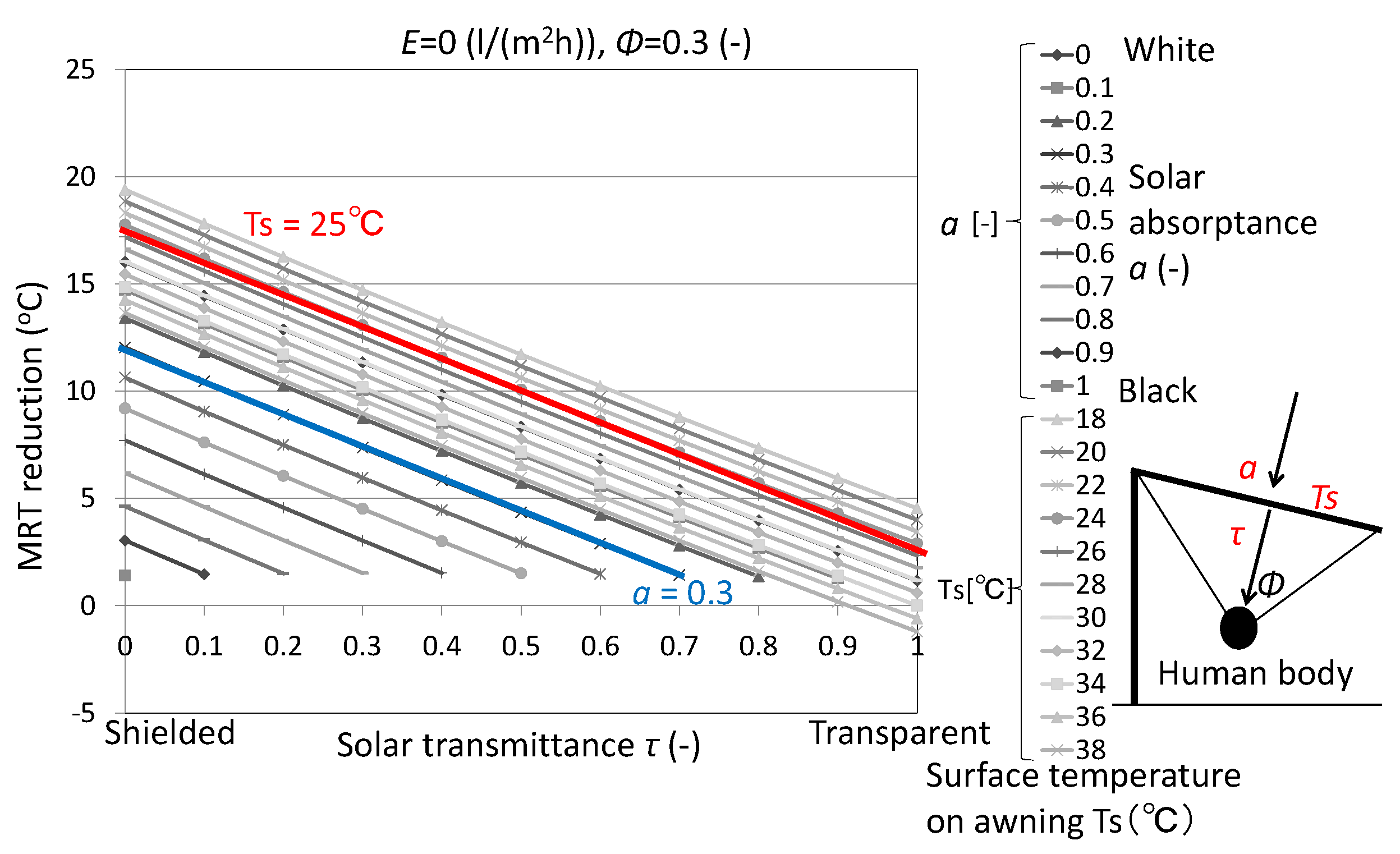

2.1. Measures to reduce solar radiation incident on the human body (tree shade, shading, awning, retroreflective facade, etc.)

- -

- Absorptance and transmittance of the solar radiation shield a, τ [-]

- -

- Evaporation flux E [g/(m2s)] or Evaporation efficiency β [-]

- -

- Convection heat transfer coefficient α [W/(m2K)]

- -

- View factor between human body and objective surface Φ [-]

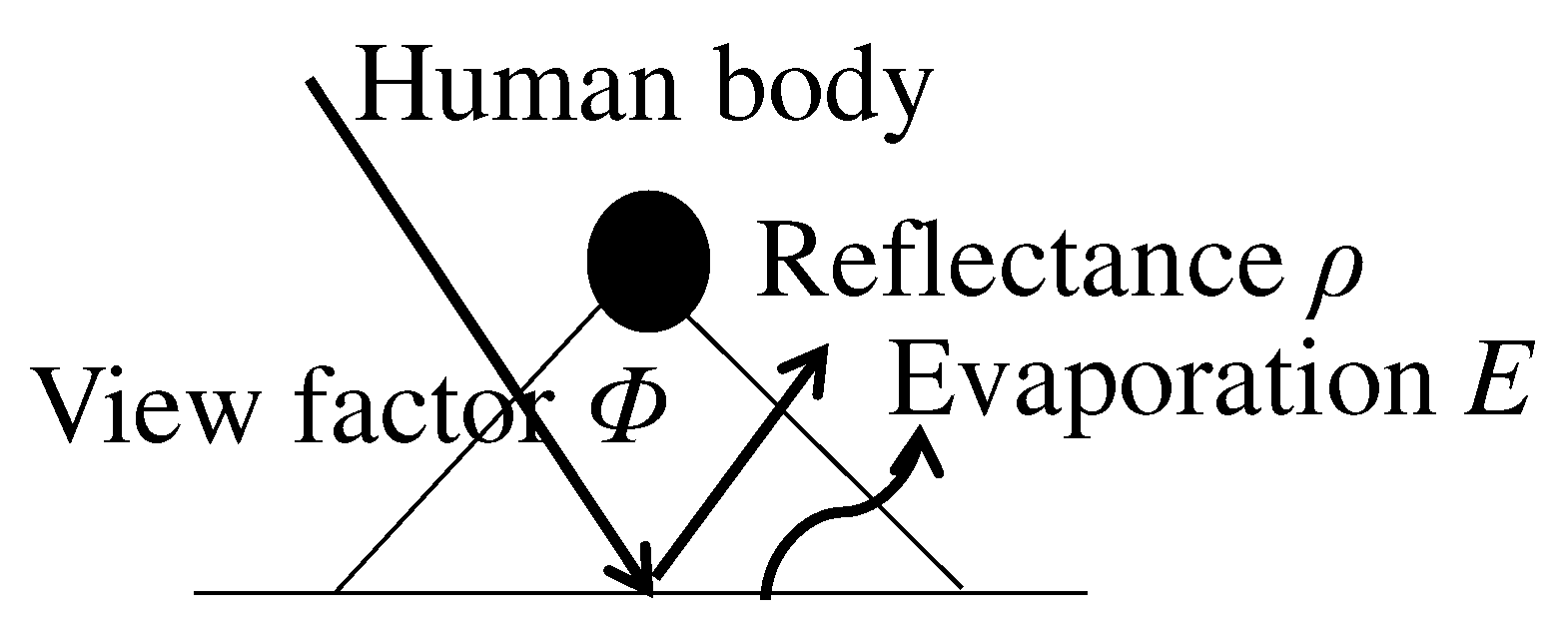

2.2. Measures to control and cool ground and wall surface temperature (water retention surface, reflection surface, greening, evaporative cooling louver, etc.)

- -

- Solar reflectance ρ [-]

- -

- Evaporation flux E [g/(m2s)] or Evaporation efficiency β [-]

- -

- View factor between human body and objective surface Φ [-]

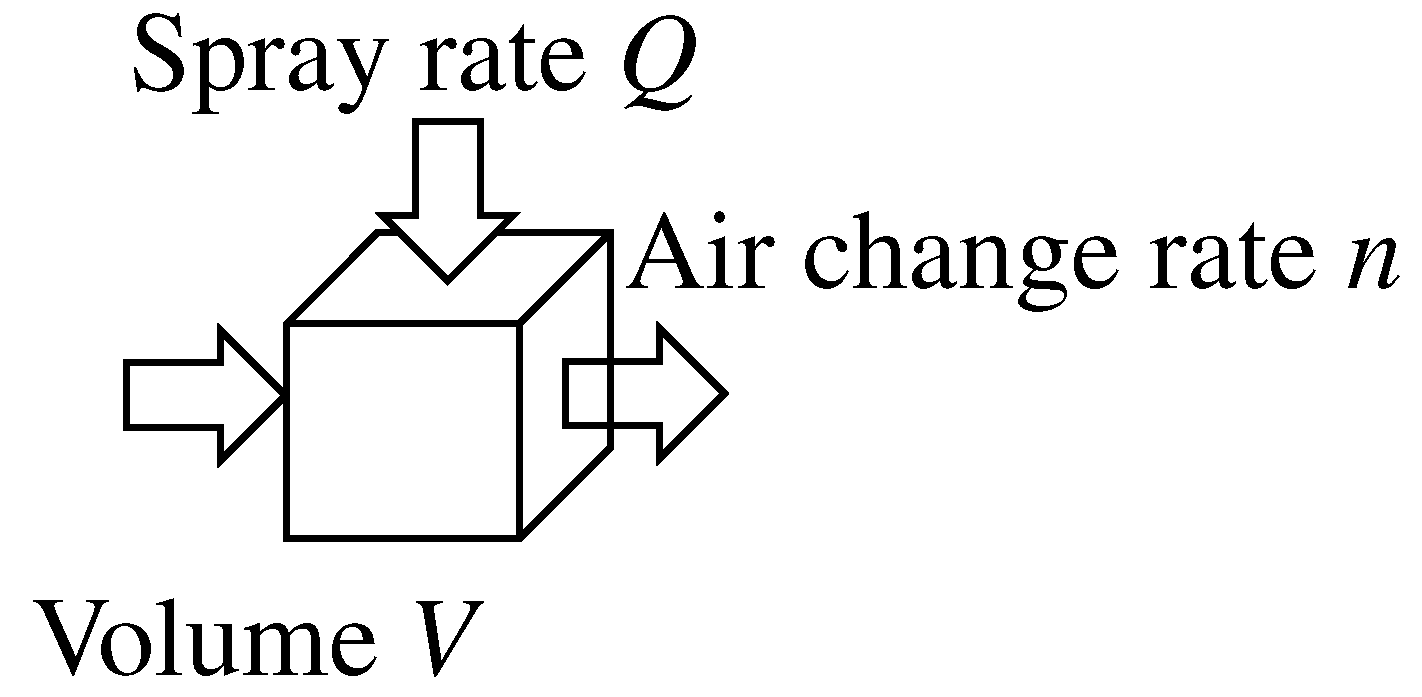

2.3. Measures to control and cool air temperature and human body (fine mist spray, airflow fan, outdoor cooling, cooling bench, etc.)

- -

- Spray rate Q [g/s]

- -

- Air change rate n [1/s]

- -

- Volume of air V [m3]

3. Case studies

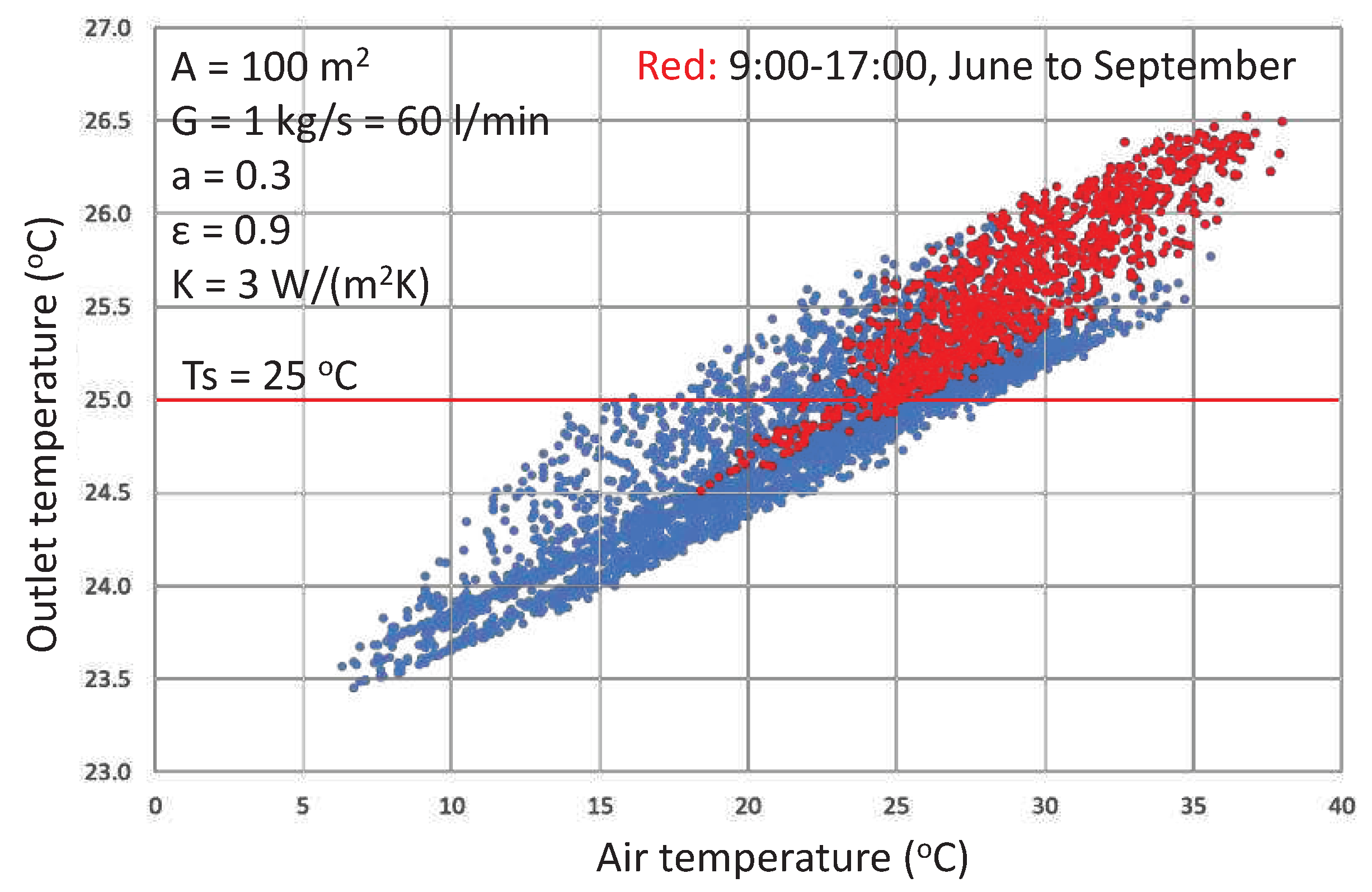

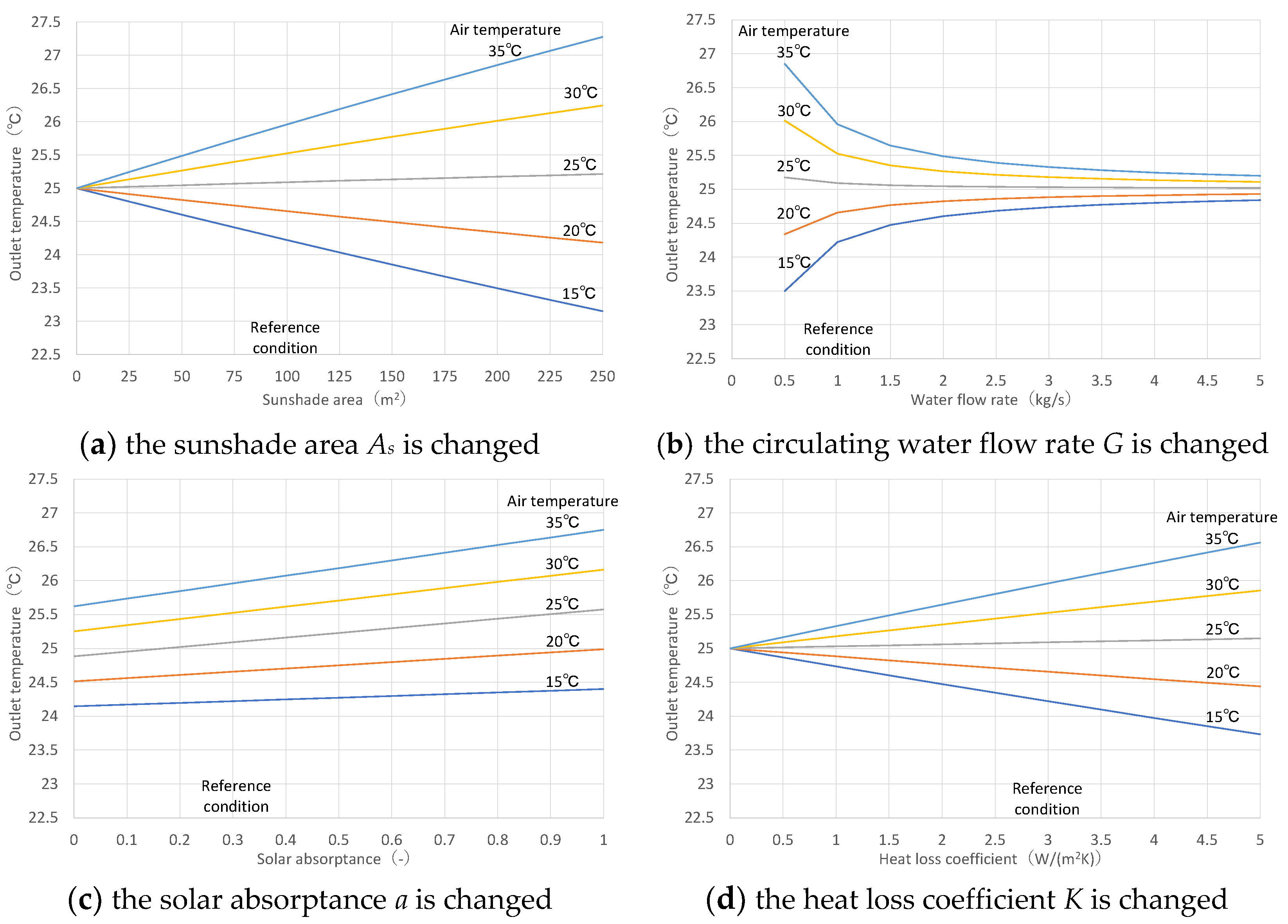

3.1. Cool water circulation sunshade

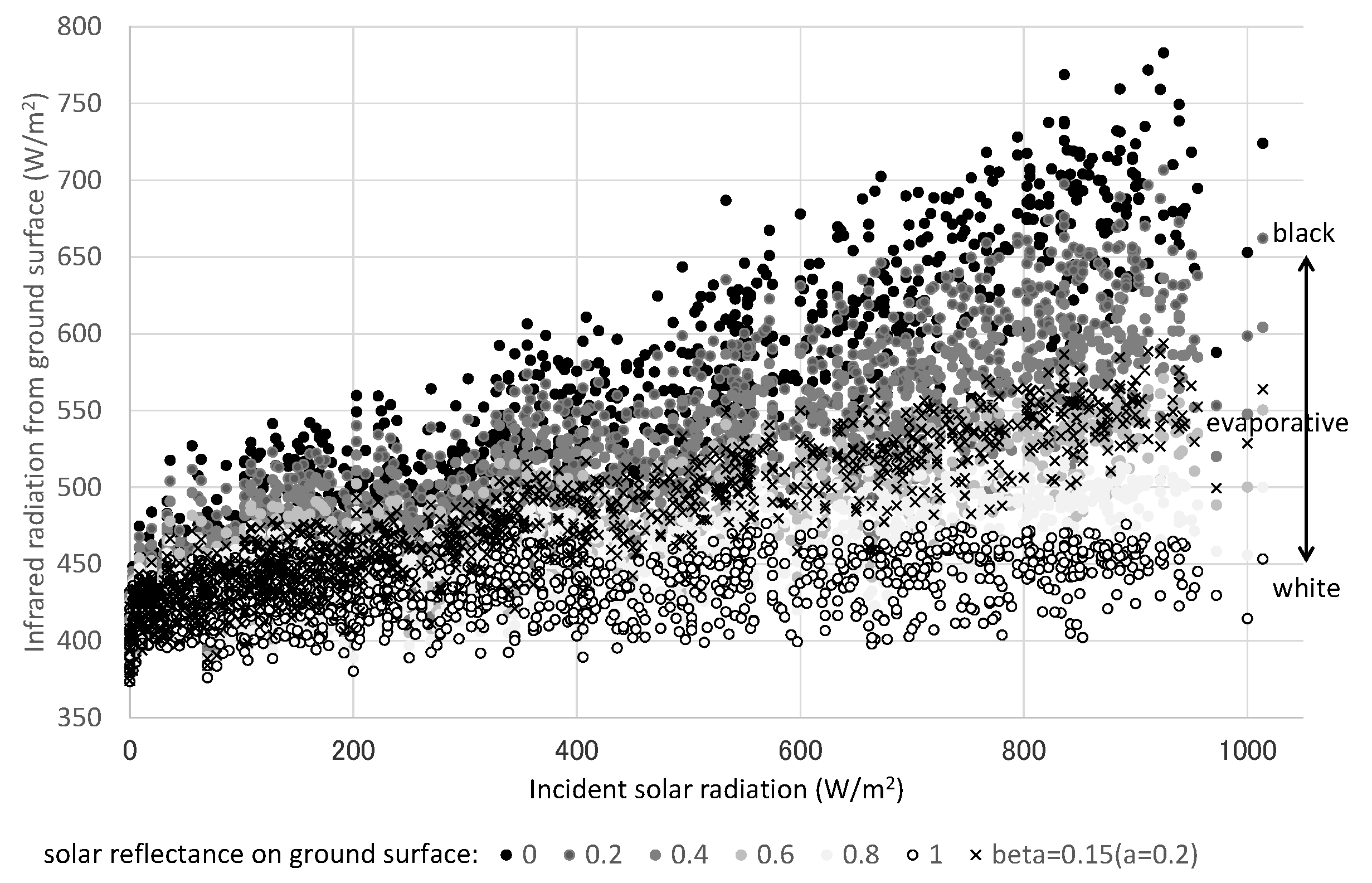

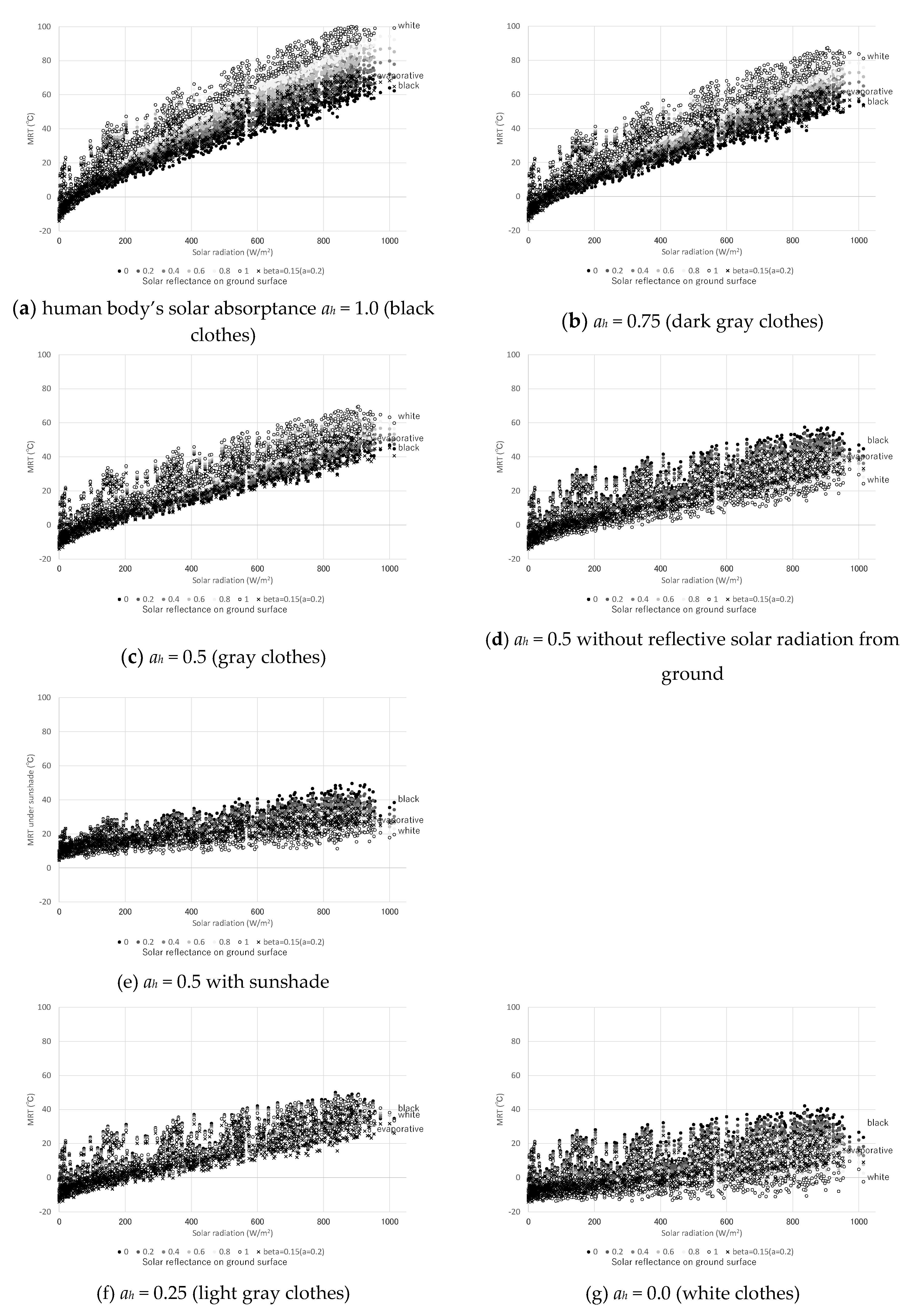

3.2. Adverse effects of reflective pavements on the human thermal environment

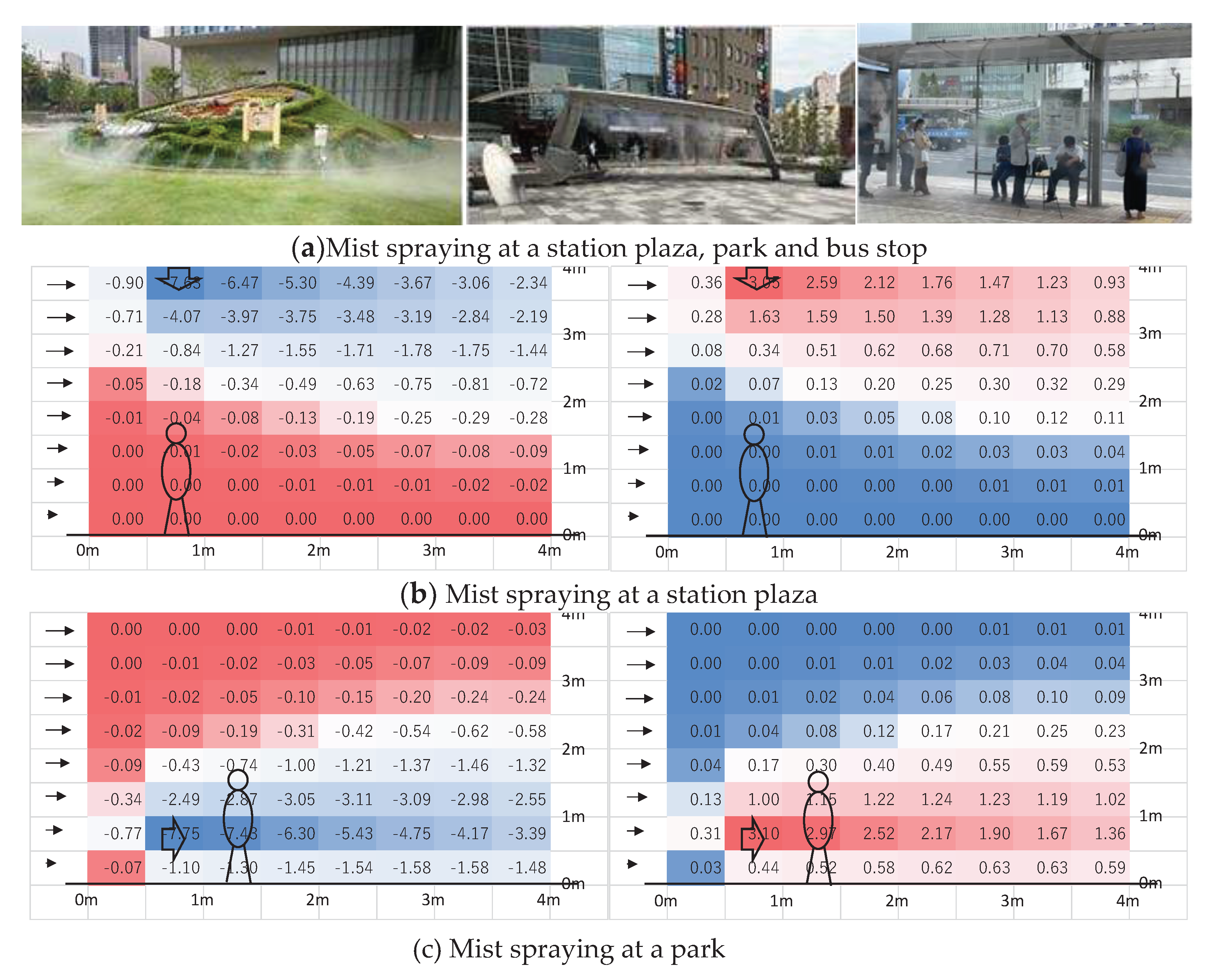

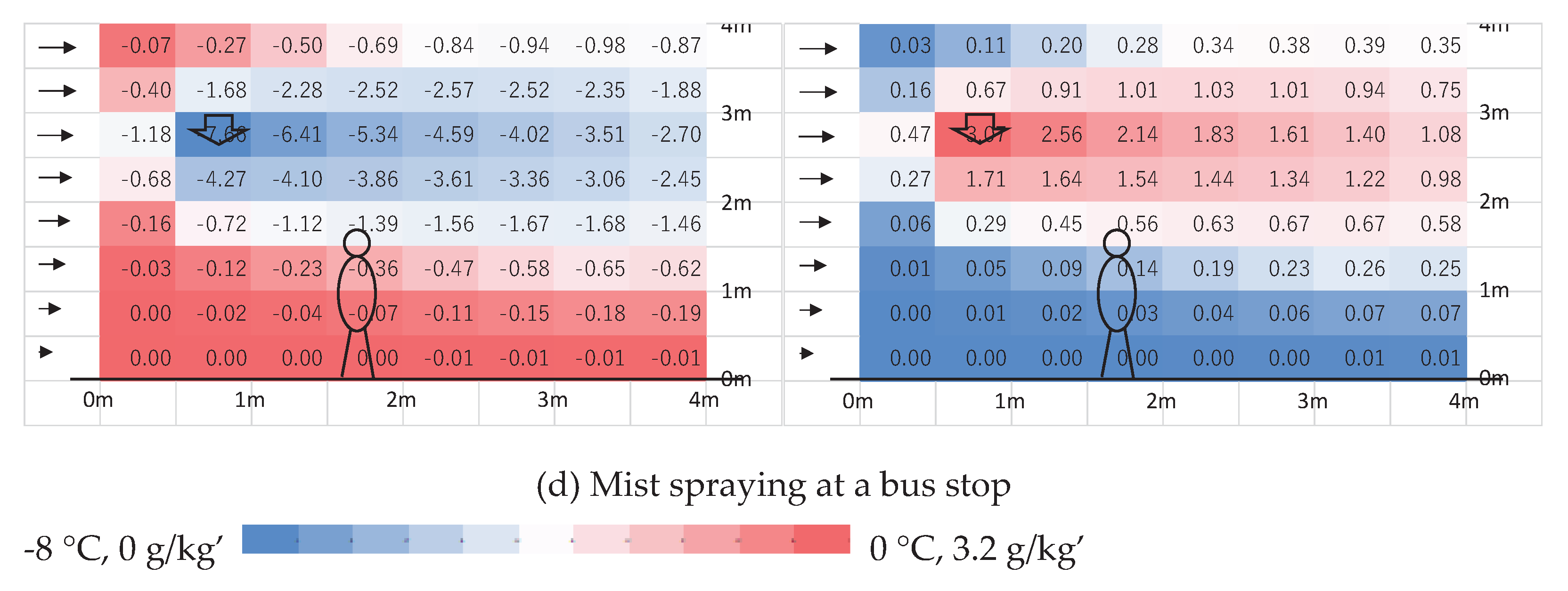

3.3. Mist splay effects on the human body

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- -

- Measures to reduce solar radiation incident on the human body

- -

- Measures to control and cool ground and wall surface temperature

- -

- Measures to control and cool air temperature and human body

- -

- Measures to reduce solar radiation incident on the human body: absorptance and transmittance of the solar radiation shield a, τ [-], evaporation flux E [g/(m2s)] or evaporation efficiency β [-], convection heat transfer coefficient α [W/(m2K)], view factor between human body and objective surface Φ [-]

- -

- Measures to control and cool ground and wall surface temperature: solar reflectance ρ [-], evaporation flux E [g/(m2s)] or evaporation efficiency β [-], view factor between human body and objective surface Φ [-]

- -

- Measures to control and cool air temperature and human body: spray rate Q [g/s], air change rate n [1/s], volume of air V [m3]

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rossi, F.; Cardinali, M.; Gambelli, A. M.; Filipponi, M.; Castellani, B.; Nicolini, A. Outdoor thermal comfort improvements due to innovative solar awning solutions: An experimental campaign. Energy and Buildings 2020, 225, 110341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Cardinali, M.; Giuseppe, A. D.; Castellani, B.; Nicolini, A. Outdoor thermal comfort improvement with advanced solar awnings: Subjective and objective survey. Building and Environment 2022, 215, 108967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, S.; Nakamura, M.; Furuya, K.; Amemura, N.; Onishi, M.; Iizawa, I.; Nakata, J.; Yamaji, K.; Asano, R.; Tamotsu, K. Sierpinski’s forest: New technology of cool roof with fractal shapes. Energy and Buildings 2012, 55, pp–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulpiani, G. Water mist spray for outdoor cooling: A systematic review of technologies, methods and impacts. Applied Energy 2019, 254, 113647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of the Environment Government of Japan, Heat Countermeasure Guideline in the City. Available online: https://www.wbgt.env.go.jp/pdf/city_gline/city_guideline_full.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Takebayashi, H.; Okubo, M.; Danno, H. Thermal Environment Map in Street Canyon for Implementing Extreme High Temperature Measures. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takebayashi, H.; Danno, H.; Tozawa, U. Study on appropriate heat mitigation technologies for urban block redevelopment based on demonstration experiments in Kobe city. Energy & Buildings 2021, 250. [Google Scholar]

- Takebayashi, H.; Danno, H.; Tozawa, U. Study on Strategies to Implement Adaptation Measures for Extreme High Temperatures into the Street Canyon. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyogoku, S.; Takebayashi, H. Experimental Verification of Mist Cooling Effect in Front of Air-Conditioning Condenser Unit, Open Space, and Bus Stop. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyogoku, S.; Takebayashi, H. Effects of Upward Reflective Film Applied to Window Glass on Indoor and Outdoor Thermal Environments in a Mid-Latitude City. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takebayashi, H.; Mori, H.; Tozawa, U. Study on An Effective Roadway Watering Scheme for Mitigating Pedestrian Thermal Comfort According to the Street Configuration. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takebayashi, H. A simple method to evaluate adaptation measures for urban heat island. Environments 2018, 5, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Nishioka, M.; Nabeshima, M.; Nakao, M.; Nakaso, Y.; Sakai, M.; Nakamura, K. Thermal energy storage air conditioning system utilizing aquifer, Performance study on air conditioning system combining direct use and heat source use with seasonal thermal energy storage. Journal of the Society of Heating, Air-Conditioning and Sanitary Engineers of Japan 2017, 248, pp–1. [Google Scholar]

- Nakao, M. Trends and practical scale demonstrations of aquifer thermal storage technology. District Heating and Cooling 2018, 120, pp–18. [Google Scholar]

- Nakao, M.; Nakai, M.; Nishioka, M.; Nabeshima, M.; Mori, N.; Yamochi, S. Use of thermal energy of bottom layer water in harbor during summer, Characteristics of vertical ocean water temperature distribution (part 1). Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Society of Heating, Air-Conditioning and Sanitary Engineers of Japan 2007, 1733–1736. [Google Scholar]

| Change of MRT, Ta, Xa | SET* reduction | WBGT reduction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sunshade | MRT -13°C | 2.7 °C | 1.0 °C |

| Watering road | MRT -2.4°C | 0.5 °C | 0.2 °C |

| Mist spray | Ta -2 °C, Xa +0.8 g/kg’ | 0.9 °C | 0.4 °C |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).