Submitted:

27 September 2023

Posted:

28 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Variables

2.2. Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Dementia. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (Accessed 27 December 2022; Updated 20 September 2022).

- GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022;7:e105-e125.

- Shon C, Yoon H. Health-economic burden of dementia in South Korea. BMC Geriatr 2021;21:549-558. [CrossRef]

- Jylh¨a M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc Sci Med 2009;69;307-316.

- Mavaddat N, Valderas JM, van der Linde R, Khaw KT, Kinmonth AL. Association of self-rated health with multimorbidity, chronic disease and psychosocial factors in a large middle-aged and older cohort from general practice: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:185. [CrossRef]

- Sargent-Cox K, Cherbuin N, Morris L, Butterworth P, Anstey KJ. The effect of health behavior change on self-rated health across the adult life course: a longitudinal cohort study. Prev Med 2014;58:75-80. [CrossRef]

- Harris SE, Hagenaars SP, Davies G, David Hill W, Liewald DCM, Ritchie SJ, Marioni RE; METASTROKE Consortium, International Consortium for Blood Pressure Genome-Wide Association Studies; International Consortium for Blood Pressure Genome-Wide Association Studies; CHARGE Consortium Aging and Longevity Group; CHARGE Consortium Cognitive Group; Sudlow CLM, Wardlaw JM, McIntosh AM, Gale CR, Deary IJ. Molecular genetic contributions to self-rated health. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:994-1009.

- Stephan Y, Sutin AR, Bayard S, Kriˇzan Z, Terracciano A. Personality and sleep quality: evidence from four prospective studies. Health Psychol 2018;37:271-281. [CrossRef]

- Park JH, Lee KS. Self-rated health and its determinants in Japan and South Korea. Public Health 2013;127:834-843. [CrossRef]

- Weisen SF, Frishman WH, Aronson MK, Wassertheil-Smoller S. Self-rated health assessment and development of both cardiovascular and dementing illnesses in an ambulatory elderly population: a report from the Bronx Longitudinal Aging Study. Heart Dis 1999;1:201-205.

- Yip AG, Brayne C, Matthews FE; MRC Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. Risk factors for incident dementia in England and Wales: The Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. A population-based nested case-control study. Age Ageing 2006;35:154-160. [CrossRef]

- Montlahuc C, Soumar’e A, Dufouil C, Berr C, Dartigues JF, Poncet M, Tzourio C, Alp´erovitch A. Self-rated health and risk of incident dementia: a community based elderly cohort, the 3C study. Neurology 2011;77:1457-1464.

- St John P, Montgomery P. Does self-rated health predict dementia? J Geriatr Psychiatr Neurol 2013;26:41-50.

- Aschwanden D, Aichele S, Ghisletta P, Terracciano A, Kliegel M, Sutin AR, Brown J, Allemand M. Predicting cognitive impairment and dementia: a machine learning approach. J Alzheimers Dis 2020;75:717-728. [CrossRef]

- Lee KS, Park KW. Social determinants of the association among cerebrovascular disease, hearing loss and cognitive impairment in a middle-aged or older population: recurrent neural network analysis of the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (2014-2016). Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19:711-716.

- Pillemer SC, Holtzer R. The differential relationships of dimensions of perceived social support with cognitive function among older adults. Aging Ment Health 2016;20:727-735. [CrossRef]

- Oh DJ, Yang HW, Kim TH, Kwak KP, Kim BJ, Kim SG, Kim JL, Moon SW, Park JH, Ryu SH, Youn JC, Lee DY, Lee DW, Lee SB, Lee JJ, Jhoo JH, Bae JB, Han JW, Kim KW. Association of low emotional and tangible support with risk of dementia among adults 60 years and older in South Korea. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e2226260. [CrossRef]

- Murata C, Saito T, Saito M, Kondo K. The Association between social support and incident dementia: a 10-year follow-up study in Japan. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:239. [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi OJ, Gill TL, Paul R, Huber LB. Evaluating the association of self-reported psychological distress and self-rated health on survival times among women with breast cancer in the U.S. PLoS One 2021;16:e0260481. [CrossRef]

- Giltay EJ, Vollaard AM, Kromhout D. Self-rated health and physician-rated health as independent predictors of mortality in elderly men. Age Ageing 2012;41:165-171. [CrossRef]

- Panda C, Mishra AK, Dash AK, Nawab H. Predicting and explaining severity of road incident using artificial intelligence, SHAP and feature analysis. International Journal of Crashworthiness 2022. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Count | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables (in 2018) | ||||

| Comorbidity | ||||

| NNa | 4244 | 71.2 | ||

| YNb | 84 | 27.3 | ||

| NYc | 5 | 0.1 | ||

| YYd | 1628 | 1.4 | ||

| Subjective/Self-Rated Health | ||||

| Very Good | 81 | 1.4 | ||

| Good | 1471 | 24.7 | ||

| Middle (Neither Good nor Poor) | 2697 | 45.2 | ||

| Poor | 1332 | 22.3 | ||

| Very Poor | 380 | 6.4 | ||

| Dementia | ||||

| Yes | 89 | 1.5 | ||

| No | 5872 | 98.5 | ||

| Subjective/Self-Rated Health (in 2016 Hereafter) | ||||

| Very Good | 56 1587 |

0.9 | ||

| Good | 1587 | 26.2 | ||

| Middle (Neither Good nor Poor) | 2720 | 45.6 | ||

| Poor | 1307 | 21.9 | ||

| Very Poor | 291 | 4.9 | ||

| Householder | ||||

| Yes | 3378 | 56.7 | ||

| No | 2583 | 43.3 | ||

| Relationship - Householder | ||||

| Spouse | 5553 | 93.2 | ||

| Parents | 32 | 0.5 | ||

| Children not Married | 75 | 1.3 | ||

| Children Married | 276 | 4.6 | ||

| Brothers/Sisters | 9 | 0.2 | ||

| Grandchildren | 1 | 0 | ||

| Grandparents | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other | 15 | 0.3 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 2489 | 41.8 | ||

| Female | 3472 | 58.2 | ||

| Marriage | ||||

| Married | 4536 | 76.1 | ||

| Separated | 35 | 0.6 | ||

| Divorced | 121 | 2 | ||

| Widowed | 1228 | 20.6 | ||

| Unmarried | 41 | 0.7 | ||

| Grandchildren under Care, Aged Less than 10 | ||||

| Yes | 242 | 4.1 | ||

| No | 5719 | 95.9 | ||

| Grandchildren under Care, Aged Less than 10 (Last Year) | ||||

| Yes | 66 | 1.1 | ||

| No | 5895 | 98.9 | ||

| Parents Alive | ||||

| Father & Mother | 230 | 3.9 | ||

| Father | 93 | 1.6 | ||

| Mother | 886 | 14.9 | ||

| None | 4752 | 79.7 | ||

| Parents Cohabiting | ||||

| Yes | 170 | 2.9 | ||

| No | 5791 | 97.1 | ||

| Father Not Cohabiting | ||||

| Not Cohabiting with Other Children | 5921 | 99.3 | ||

| Cohabiting with Other Children | 38 | 0.6 | ||

| Other | 2 | 0 | ||

| Mother Not Cohabiting | ||||

| Not Cohabiting with Other Children | 5683 | 95.3 | ||

| Cohabiting with Other Children | 227 | 3.8 | ||

| Other | 51 | 0.9 | ||

| Health Insurance | ||||

| Health Insurance | 5673 | 95.2 | ||

| Medicare | 288 | 4.8 | ||

| Economic Activity | ||||

| Employed | 2210 | 37.1 | ||

| Unemployed | 3751 | 63 | ||

| Religion | ||||

| Non | 3412 | 57.2 | ||

| Protestant | 1011 | 17 | ||

| Catholic | 414 | 6.9 | ||

| Buddhist | 1082 | 18.2 | ||

| Won-Buddhist | 13 | 0.2 | ||

| Other | 29 | 0.5 | ||

| Drinker | ||||

| Current | 1931 | 32.4 | ||

| Former | 984 | 16.5 | ||

| Non | 3046 | 51.1 | ||

| Smoker | ||||

| Non | 4132 | 69.3 | ||

| Former | 1210 | 20.3 | ||

| Current | 619 | 10.4 | ||

| Education | ||||

| Elementary or Below | 2559 | 42.9 | ||

| Junior High | 1059 | 17.8 | ||

| Senior High | 1737 | 29.1 | ||

| College or Above | 606 | 10.2 | ||

| a | NN for | Subjective Health very good, good or middle | Dementia No | |

| b | YN for | Subjective Health poor or very poor | Dementia No | |

| c | NY for | Subjective Health very good, good or middle | Dementia Yes | |

| d | YY for | Subjective Health poor or very poor | Dementia Yes | |

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | 25% | 50% | 75% | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 69 | 9 | 55 | 61 | 68 | 76 | 100 |

| Meeting - Friendship | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 10 |

| Activity - Religious | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 |

| Activity - Friendship | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 16 |

| Activity - Leisure | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 |

| Activity - Association | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 |

| Body Mass Index | 23 | 3 | 12 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 42 |

| # Chronic Diseases | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| # Children Alive | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 9 |

| Income (Last Year) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| # Children Cohabiting | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| # Children Cohabiting, Single | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| # Children Living Nearby* | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| # Children Meeting Often** | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| # Children Contacting Often** | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 9 |

| # Grandchildren | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 34 |

| # Grandchildren Under Care | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| # Grandchildren Under Care (Last Year) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| # Brothers/Sisters Alive | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 11 |

| # Brothers/Sisters Cohabiting | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| # Cohabiting Months with Father | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| # Cohabiting Months with Mother | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 12 |

| Distance to Father*** | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Monthly Frequency - Meeting Father | 7 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 9 |

| Monthly Frequency - Contacting Father | 4 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Distance to Mother*** | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Monthly Frequency - Meeting Mother | 7 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 10 |

| Monthly Frequency - Contacting Mother | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 10 |

| Life Satisfaction - Health | 59 | 19 | 0 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 100 |

| Life Satisfaction - Economic | 56 | 19 | 0 | 50 | 70 | 70 | 100 |

| Life Satisfaction - Overall | 63 | 16 | 0 | 50 | 70 | 70 | 100 |

| Subjective Class (1-6 Scale) | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Variable | Imputation | Deletion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | AUC | Accuracy | AUC | |||||

| LR | RF | LR | RF | LR | RF | LR | RF | |

| Subjective Health | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.82 | 0.80 |

| Dementia | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.30 | 0.27 |

| Comorbidity | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.8 | 0.83 | 0.84 |

| Comorbidity | Subjective Health | Dementia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective Health - Previous Period | 0.1185 | Subjective Health - Previous Period | 0.0843 | Body Mass Index | 0.1013 |

| Life Satisfaction - Health | 0.0820 | Body Mass Index | 0.0738 | Age | 0.0903 |

| Age | 0.0746 | Income | 0.0732 | Income | 0.0847 |

| Body Mass Index | 0.0661 | Age | 0.0720 | # Grandchildren | 0.0646 |

| Income | 0.0645 | Life Satisfaction - Health | 0.0577 | Life Satisfaction - Health | 0.0490 |

| # Chronic Diseases | 0.0532 | # Grandchildren | 0.0456 | Life Satisfaction - Economic | 0.0484 |

| Life Satisfaction - Economic | 0.0497 | Life Satisfaction - Economic | 0.0454 | Meeting - Friendship | 0.0481 |

| Life Satisfaction - Overall | 0.0446 | Meeting - Friendship | 0.0416 | Life Satisfaction - Overall | 0.0469 |

| # Grandchildren | 0.0440 | # Brothers/Sisters Alive | 0.0409 | # Children Alive | 0.0461 |

| Meeting - Friendship | 0.0402 | # Chronic Diseases | 0.0403 | # Chronic Diseases | 0.0450 |

| # Brothers/Sisters Alive | 0.0334 | Life Satisfaction - Overall | 0.0388 | Subjective Health - Previous Period | 0.0433 |

| Subjective Class | 0.0316 | Subjective Class | 0.0327 | # Brothers/Sisters Alive | 0.0382 |

| # Children Alive | 0.0309 | # Children Alive | 0.0322 | # Children Contacting | 0.0299 |

| Activity - Friendship | 0.0282 | Activity - Friendship | 0.0315 | Subjective Class | 0.0280 |

| Education | 0.0264 | Education | 0.0265 | Religion | 0.0237 |

| # Children Contacting | 0.0233 | # Children Contacting | 0.0262 | Activity - Friendship | 0.0204 |

| Religion | 0.0206 | Religion | 0.0252 | Drinker | 0.0193 |

| Drinker | 0.0168 | Drinker | 0.0199 | Relationship - Householder | 0.0190 |

| Economic Activity | 0.0143 | Smoker | 0.0164 | Smoker | 0.0179 |

| Marriage | 0.0138 | Marriage | 0.0134 | Education | 0.0177 |

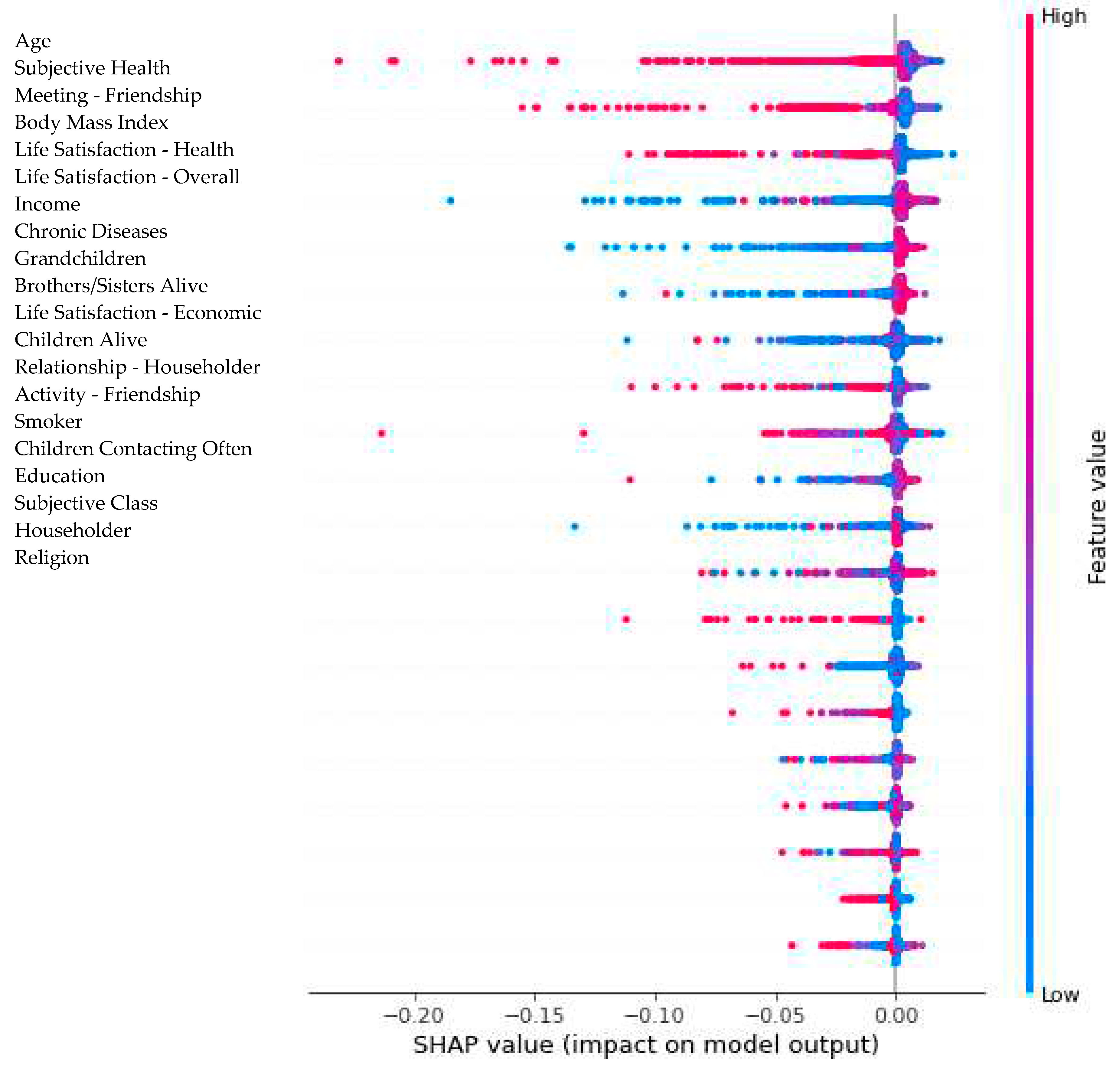

| Predictor/Dependent Variable | Comorbidity | Self-Rated Health | Dementia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Min | Max | Min | Max | |

| # Chronic Diseases | -0.0062 | 0.0024 | -0.1060 | 0.0811 | -0.0964 | 0.0107 |

| Subjective Health | -0.0079 | 0.0026 | -0.1788 | 0.2099 | -0.1336 | 0.0155 |

| Religion | -0.0008 | 0.0008 | -0.0172 | 0.0633 | -0.0297 | 0.0063 |

| Meeting - Friendship | -0.0017 | 0.0010 | -0.0646 | 0.0441 | -0.0966 | 0.0169 |

| Activity - Religious | -0.0005 | 0.0001 | -0.0320 | 0.0317 | -0.0468 | 0.0042 |

| Activity - Friendship | -0.0041 | 0.0017 | -0.0472 | 0.0910 | -0.0244 | 0.0077 |

| Activity - Leisure | -0.0003 | 0.0000 | -0.0278 | 0.0440 | -0.0105 | 0.0019 |

| Activity - Association | -0.0015 | 0.0031 | -0.0363 | 0.0961 | -0.1373 | 0.0014 |

| Householder | -0.0008 | 0.0011 | -0.0150 | 0.0148 | -0.0219 | 0.0063 |

| Relationship - Householder | -0.0006 | 0.0001 | -0.0239 | 0.0233 | -0.0509 | 0.0123 |

| # Children Alive | -0.0016 | 0.0039 | -0.0331 | 0.0378 | -0.0690 | 0.0100 |

| # Children Cohabiting | -0.0006 | 0.0001 | -0.0136 | 0.0254 | -0.0752 | 0.0031 |

| # Children Cohabiting, Single | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.0071 | 0.0282 | -0.0094 | 0.0009 |

| # Children Living Nearby | -0.0014 | 0.0017 | -0.0214 | 0.0615 | -0.0295 | 0.0039 |

| # Children Meeting Often | -0.0008 | 0.0001 | -0.0103 | 0.0608 | -0.0440 | 0.0016 |

| # Children Contacting Often | -0.0008 | 0.0011 | -0.0435 | 0.0399 | -0.0382 | 0.0048 |

| # Grandchildren | -0.0011 | 0.0036 | -0.0478 | 0.0424 | -0.2100 | 0.0167 |

| Grandchildren Under Care | -0.0003 | 0.0000 | -0.0183 | 0.0180 | -0.0109 | 0.0013 |

| # Grandchildren Under Care | -0.0005 | 0.0000 | -0.0099 | 0.0056 | -0.0171 | 0.0020 |

| Grandchildren Under Care (Last Year) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.0099 | 0.0239 | -0.0003 | 0.0005 |

| # Grandchildren Under Care (Last Year) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.0006 | 0.0052 | -0.0002 | 0.0010 |

| # Brothers/Sisters Alive | -0.0008 | 0.0005 | -0.0271 | 0.0652 | -0.1114 | 0.0077 |

| # Brothers/Sisters Cohabiting | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.0009 | 0.0031 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Parents Alive | -0.0002 | 0.0002 | -0.0248 | 0.0384 | -0.0024 | 0.0023 |

| # Cohabiting Months with Father | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.0335 | 0.0129 | -0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| # Cohabiting Months with Mother | -0.0002 | 0.0001 | -0.0124 | 0.0284 | -0.0011 | 0.0010 |

| Parents Cohabiting | -0.0002 | 0.0000 | -0.0227 | 0.0183 | -0.0003 | 0.0003 |

| Father Cohabiting with Other Children | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.0005 | 0.0137 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 |

| Distance to Father | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.0180 | 0.0362 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Monthly Frequency - Meeting Father | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.0257 | 0.0235 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Monthly Frequency - Contacting Father | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.0254 | 0.0233 | -0.0001 | 0.0003 |

| Mother Cohabiting with Other Children | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.0230 | 0.0204 | -0.0002 | 0.0008 |

| Distance to Mother | -0.0001 | 0.0001 | -0.0146 | 0.0330 | -0.0002 | 0.0002 |

| Monthly Frequency - Meeting Mother | -0.0002 | 0.0000 | -0.0151 | 0.0694 | -0.0006 | 0.0001 |

| Monthly Frequency - Contacting Mother | -0.0004 | 0.0001 | -0.0336 | 0.0501 | -0.0003 | 0.0003 |

| Education | -0.0022 | 0.0017 | -0.0416 | 0.0753 | -0.0463 | 0.0074 |

| Gender | -0.0011 | 0.0007 | -0.0130 | 0.0196 | -0.0108 | 0.0058 |

| Age | -0.0016 | 0.0028 | -0.1215 | 0.1101 | -0.2239 | 0.0176 |

| Marriage | -0.0034 | 0.0011 | -0.0434 | 0.0252 | -0.0166 | 0.0092 |

| Body Mass Index | -0.0015 | 0.0065 | -0.0510 | 0.0817 | -0.1325 | 0.0136 |

| Smoker | -0.0014 | 0.0014 | -0.0217 | 0.0376 | -0.0318 | 0.0042 |

| Drinker | -0.0010 | 0.0011 | -0.0146 | 0.0353 | -0.0321 | 0.0064 |

| Health Insurance | -0.0012 | 0.0000 | -0.0308 | 0.0224 | -0.0264 | 0.0022 |

| Economic Activity | -0.0018 | 0.0014 | -0.0159 | 0.0375 | -0.0101 | 0.0029 |

| Income | -0.0011 | 0.0018 | -0.0467 | 0.0961 | -0.0827 | 0.0162 |

| Life Satisfaction - Health | -0.0040 | 0.0017 | -0.0948 | 0.0935 | -0.0769 | 0.0101 |

| Life Satisfaction - Economic | -0.0029 | 0.0009 | -0.0699 | 0.0635 | -0.1263 | 0.0125 |

| Life Satisfaction - Overall | -0.0028 | 0.0042 | -0.0345 | 0.0558 | -0.0428 | 0.0074 |

| Subjective Class | -0.0019 | 0.0037 | -0.0636 | 0.0720 | -0.0389 | 0.0087 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).