Submitted:

25 September 2023

Posted:

25 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

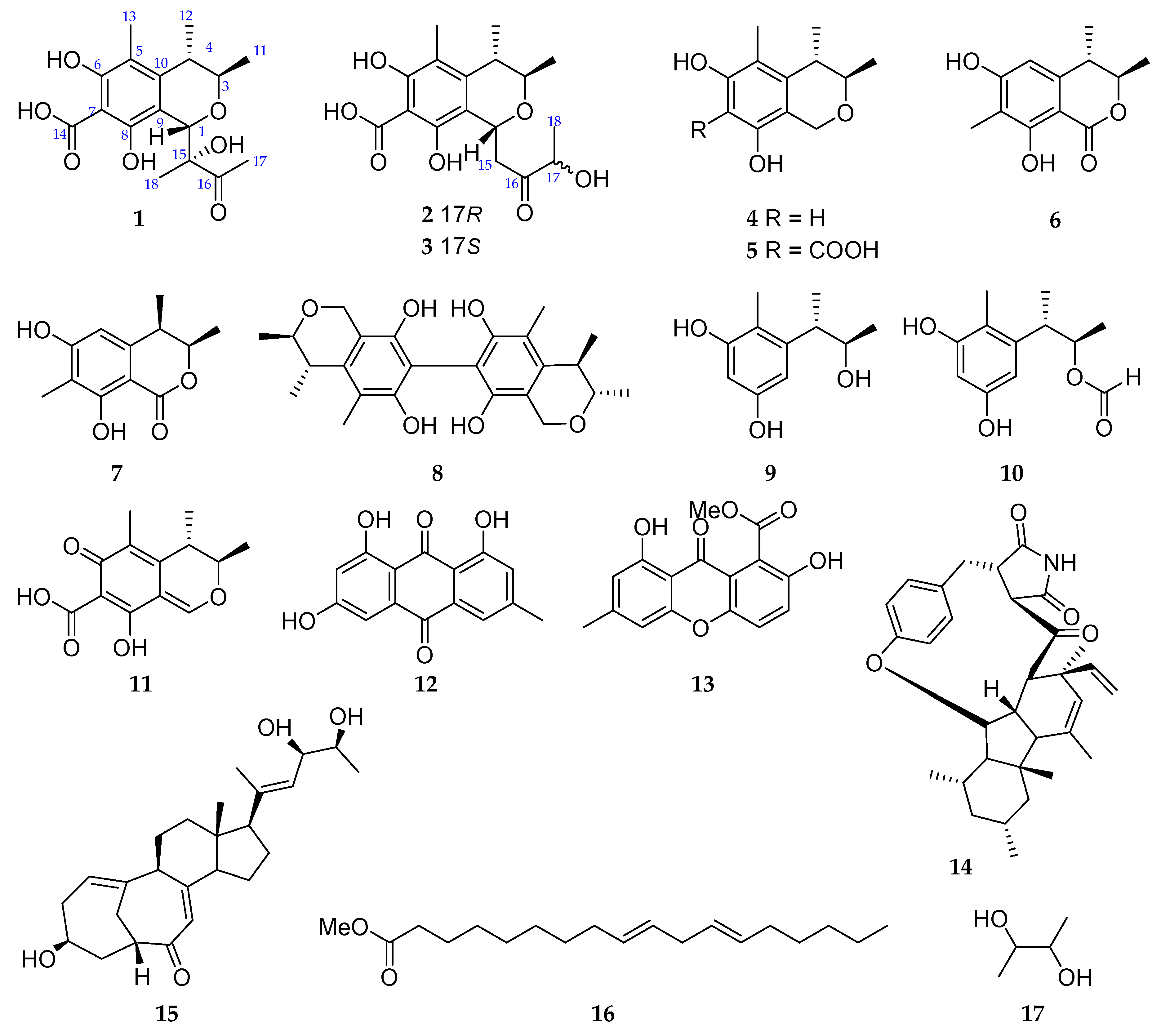

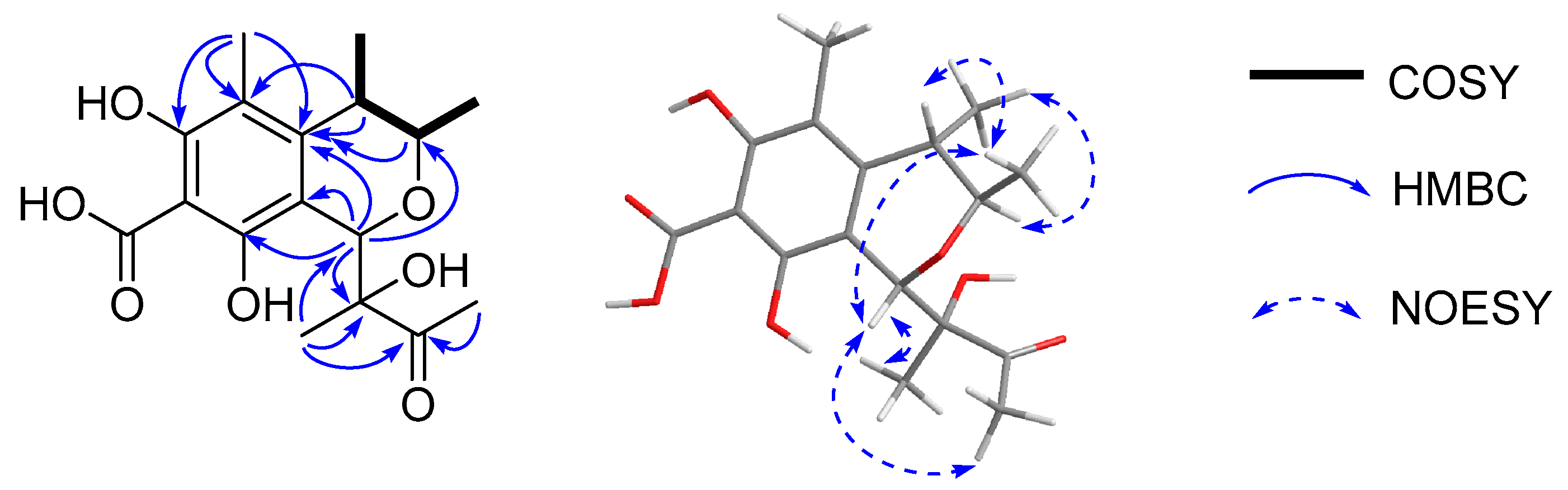

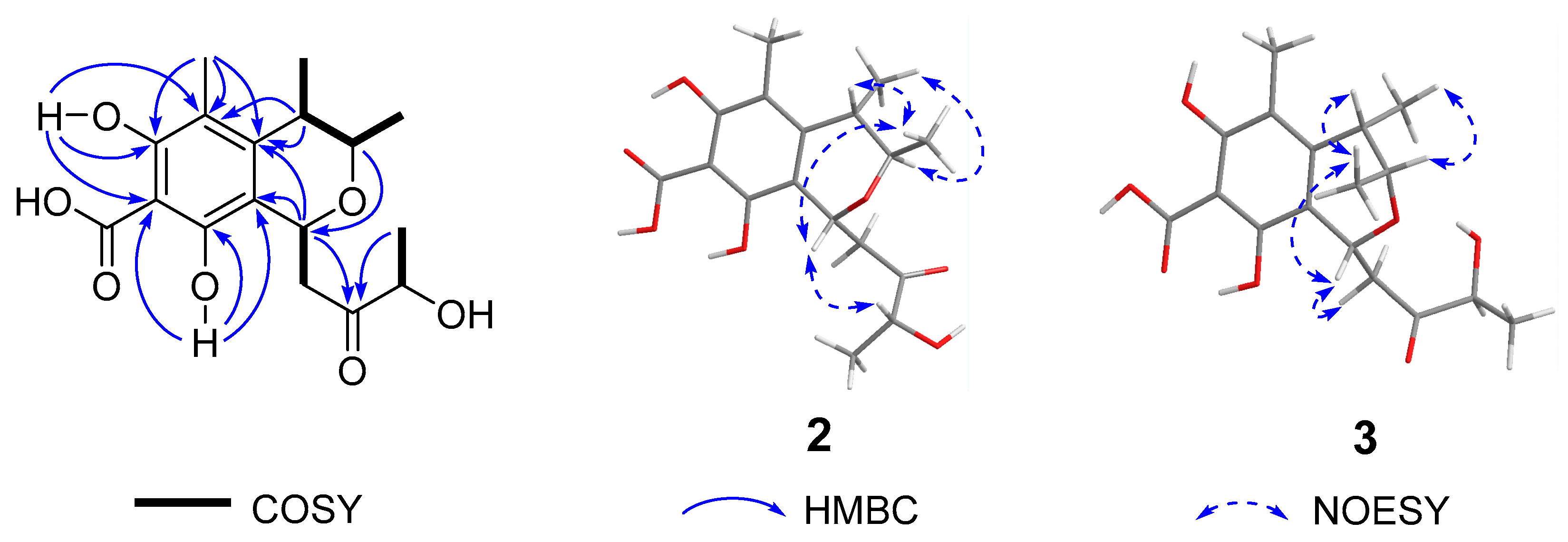

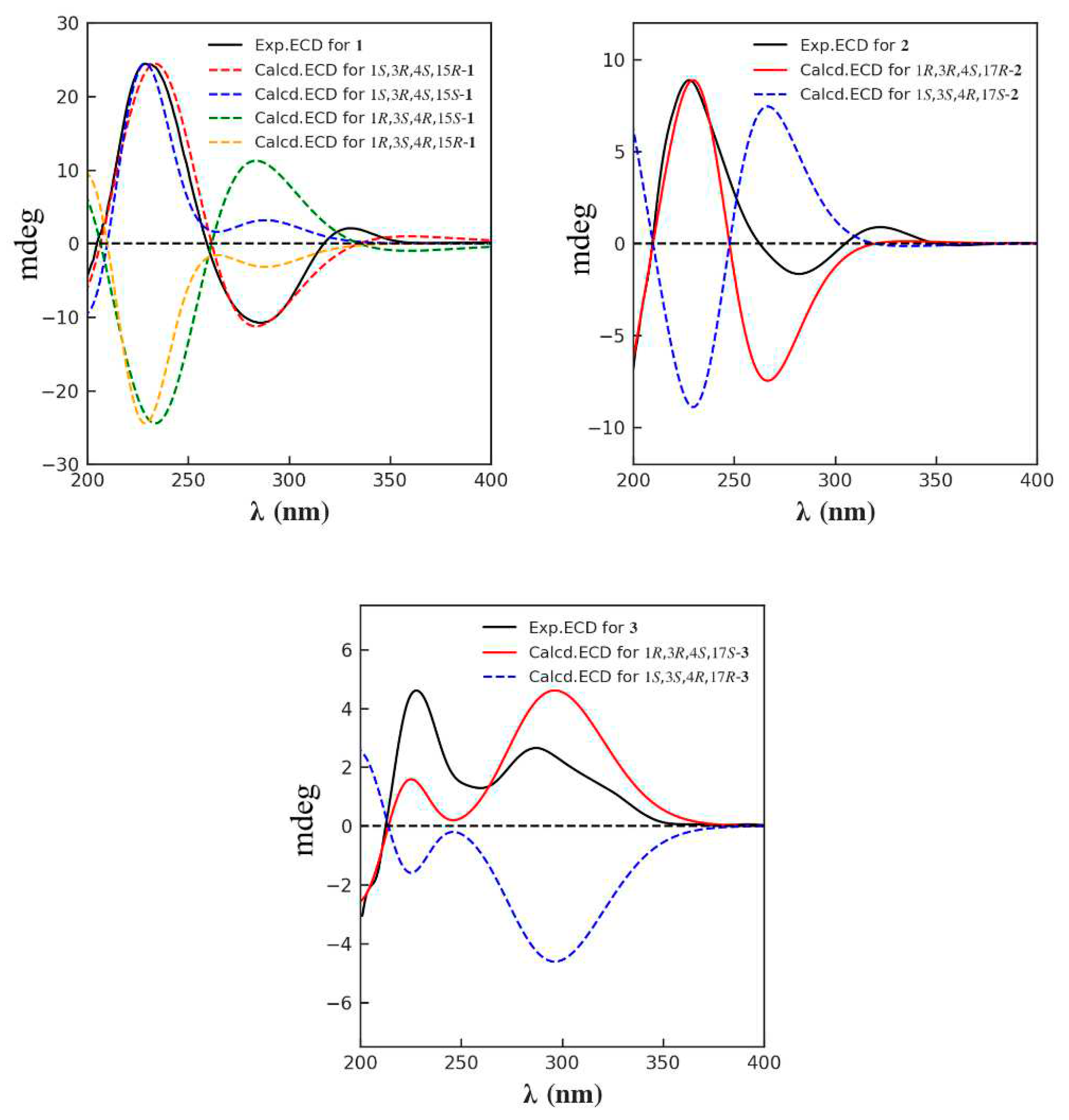

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

3.2. Fungal Identification, Fermentation, and Extraction

3.3. Isolation and Purification

3.4. ECD Calculation

3.5. BV-2 Cell Culture and Compounds Treatment

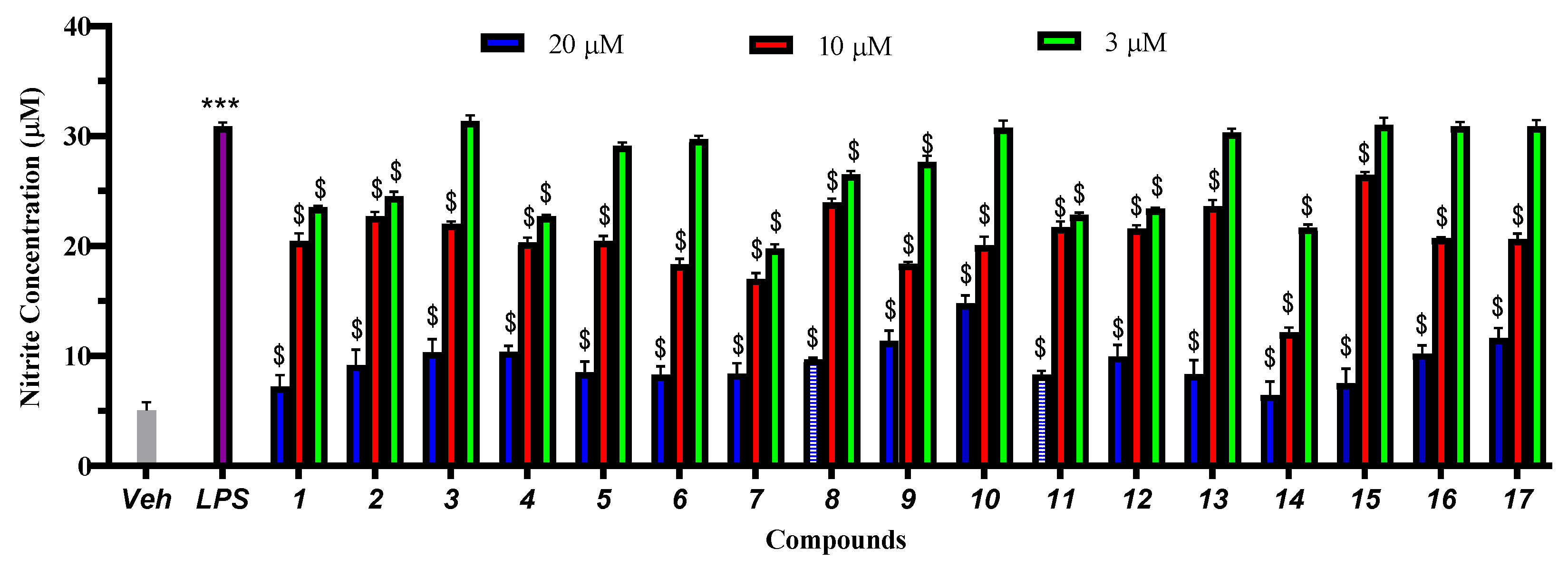

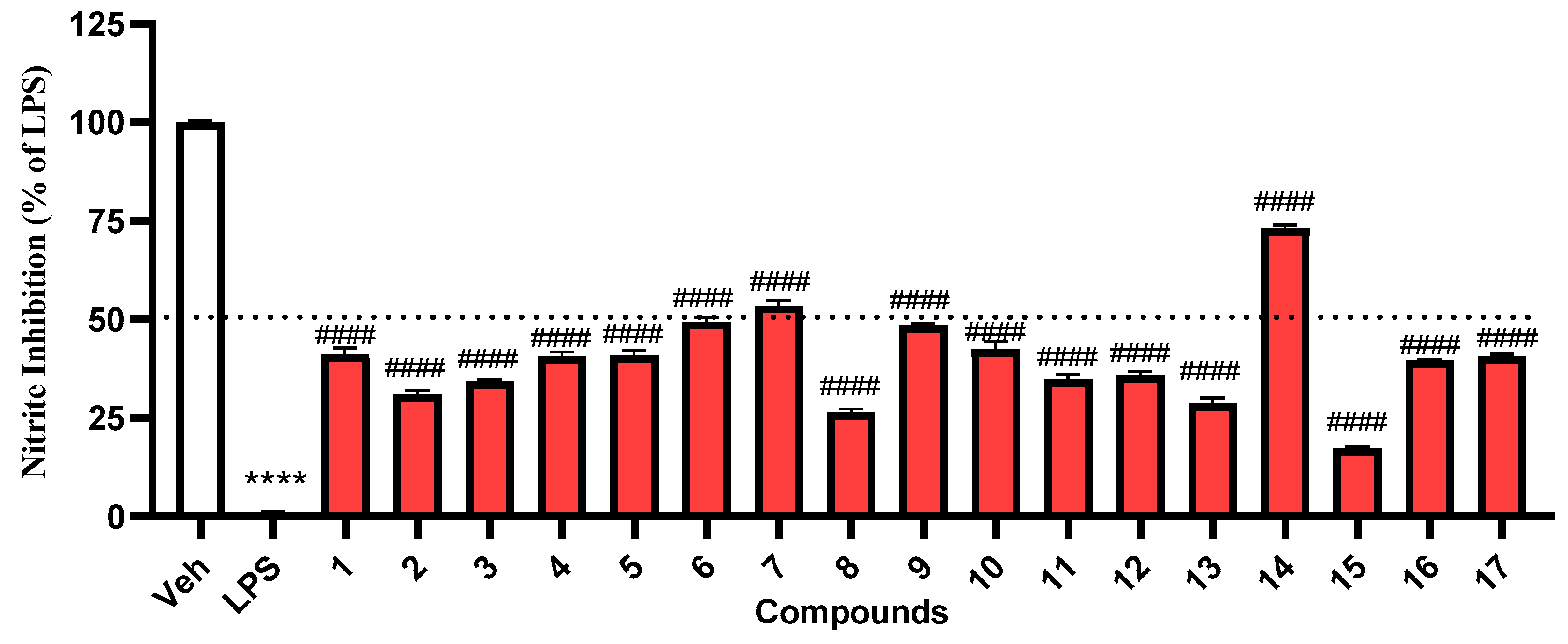

3.6. Quantification of Nitrite Levels

3.7. Cell Extraction and Culture

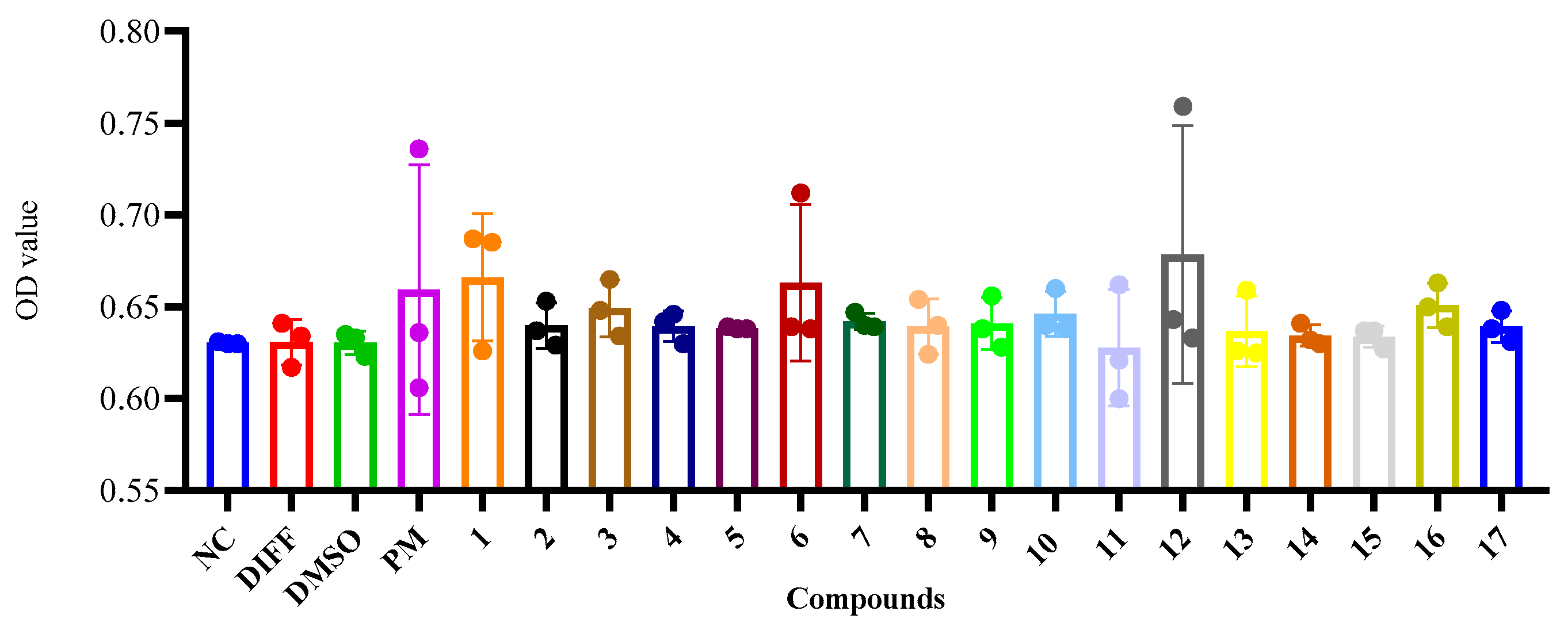

3.8. CCK-8 Assay

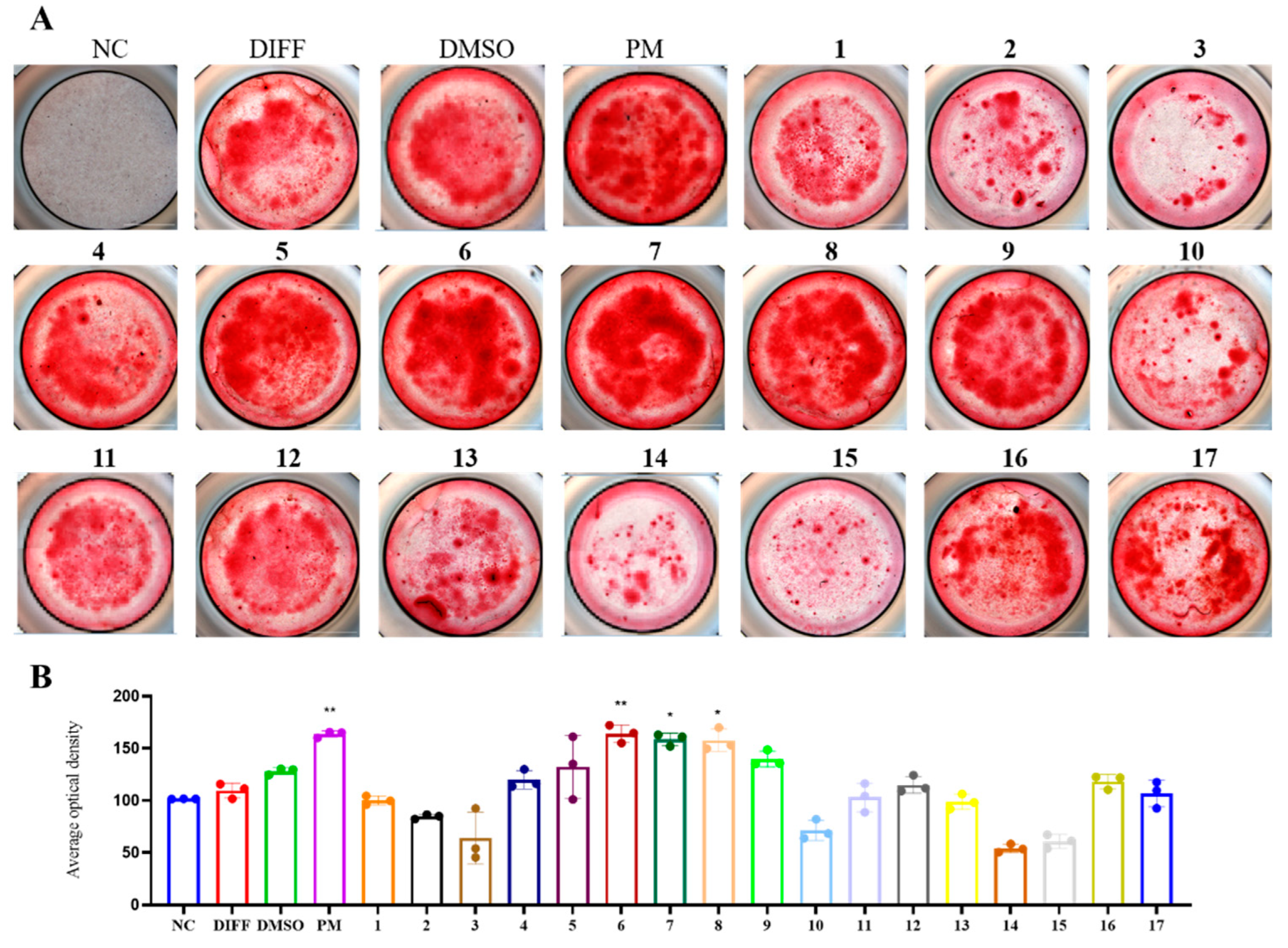

3.9. Osteoblast Differentiation and Mineralization

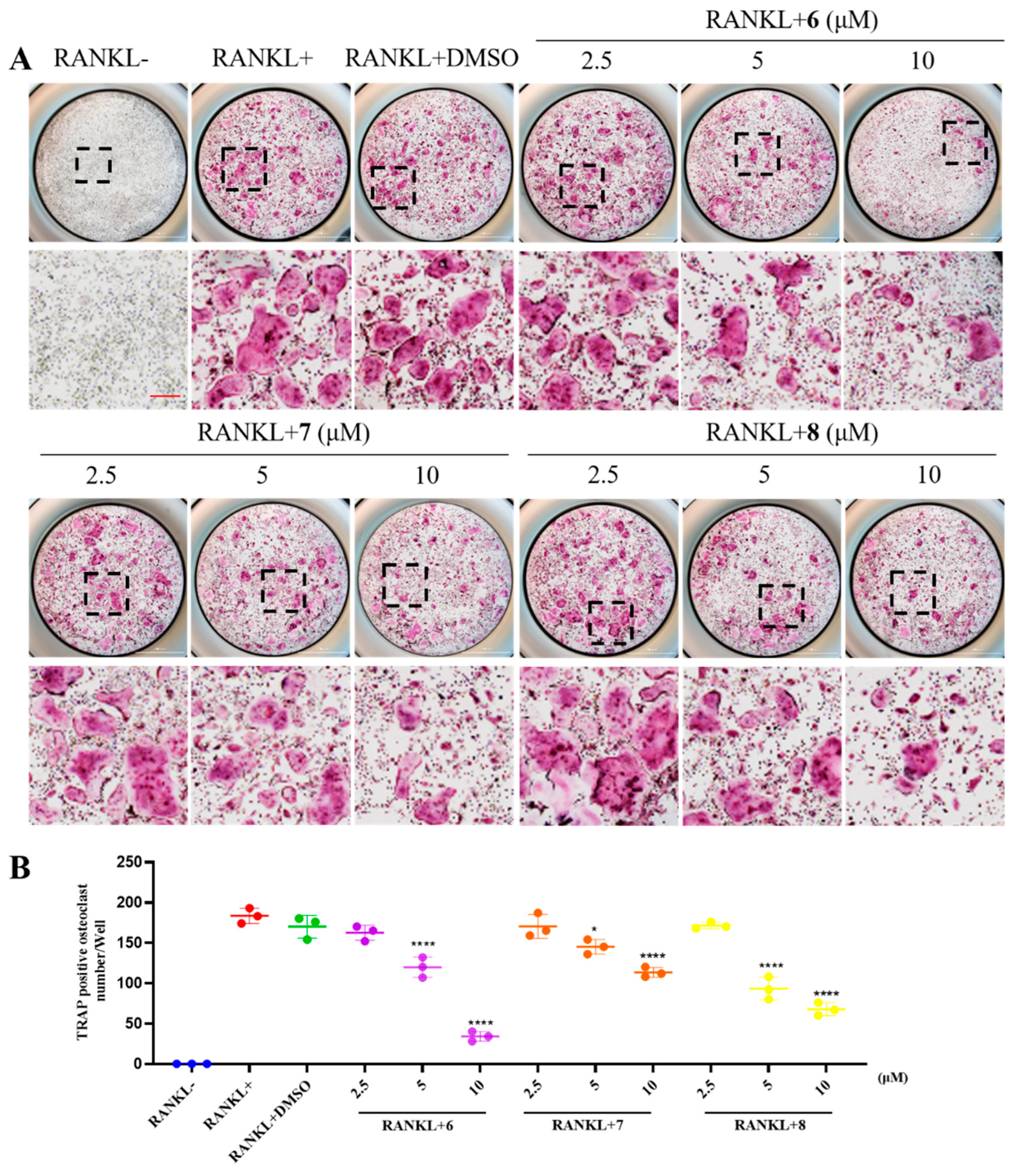

3.10. Osteoclast Differentiation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carroll, A.R.; Copp, B.R.; Davis, R.A.; Keyzers, R.A.; Prinsep, M.R. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2023, 40, 275–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voser, T.M.; Campbell, M.D.; Carroll, A.R. How different are marine microbial natural products compared to their terrestrial counterparts? Nat. Prod. Rep. 2022, 39, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, A.R.; Copp, B.R.; Davis, R.A.; Keyzers, R.A.; Prinsep, M.R. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2022, 39, 1122–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skropeta, D.; Wei, L. Recent advances in deep-sea natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 999–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Mudassir, S.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, Y.; Chang, Y.; Che, Q.; Gu, Q.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, G.; Li, D. Secondary metabolites from deep-sea derived microorganisms. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 6244–6273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chooi, Y.H.; Tang, Y. Navigating the fungal polyketide chemical space: From genes to molecules. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 9933–9953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Tang, X.X.; Fan, Z.; Xia, J.M.; Xie, C.L.; Yang, X.W. Fusarisolins A-E, polyketides from the marine-derived fungus Fusarium solani H918. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojer, F.; Ferrer, J.L.; Richard, S.B.; Nagegowda, D.A.; Chye, M.L.; Bach, T.J.; Noel, J.P. Structural basis for the design of potent and species-specific inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA synthases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 11491–11496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pascale, G.; Nazi, I.; Harrison, P.H.; Wright, G.D. β-Lactone natural products and derivatives inactivate homoserine transacetylase, a target for antimicrobial agents. J. Antibiot. 2011, 64, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feling, R.H.; Buchanan, G.O.; Mincer, T.J.; Kauffman, C.A.; Jensen, P.R.; Fenical, W. Salinosporamide A: A highly cytotoxic proteasome inhibitor from a novel microbial source, a marine bacterium of the new genus salinospora. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Zhang, Y.H.; Shao, C.L.; Cao, F.; Wang, C.Y. Microketides A and B, polyketides from a gorgonian-derived Microsphaeropsis sp. fungus. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 1300–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, M.H.; Hsiao, G.; Chang, C.H.; Yang, Y.L.; Ju, Y.M.; Kuo, Y.H.; Lee, T.H. Polyketides with anti-neuroinflammatory activity from Theissenia cinerea. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 1898–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Chen, Z.Q.; Shen, N.X.; Shen, L.; Zhang, F.M.; Zhou, X.J.; Wang, C.Y. NaBr-induced production of brominated azaphilones and related tricyclic polyketides by the marine-derived fungus Penicillium janthinellum HK1-6. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Xia, G.; Huang, H.; Li, H.; Ma, L.; Lu, Y.; He, L.; Xia, X.; She, Z. Polyketides with α-glucosidase inhibitory activity from a mangrove endophytic fungus, Penicillium sp. HN29-3B1. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 1816–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Chen, L.; Zhu, T.; Kurtán, T.; Mándi, A.; Zhao, Z.; Li, J.; Gu, Q. Chloctanspirones A and B, novel chlorinated polyketides with an unprecedented skeleton, from marine sediment derived fungus Penicillium terrestre. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 7913–7918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.H.; Xie, C.L.; Wu, T.; Yue, Y.T.; Wang, C.F.; Xu, L.; Xie, M.M.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, Y.J.; Xu, R.; Yang, X.W. Tetracyclic steroids bearing a bicyclo[4.4.1] ring system as potent antiosteoporosis agents from the deep-sea-derived fungus Rhizopus sp. W23. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.J.; Zou, Z.B.; Xie, M.M.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Yu, H.Y.; Ma, H.B.; Yang, X.W. Ferroptosis inhibitory compounds from the deep-sea-derived fungus Penicillium sp. MCCC 3A00126. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.H.; Xie, C.L.; Wu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, Z.B.; Xie, M.M.; Xu, L.; Capon, R.J.; Xu, R.; Yang, X.W. Neotricitrinols A-C, unprecedented citrinin trimers with anti-osteoporosis activity from the deep-sea-derived Penicillium citrinum W23. Bioorg. Chem. 2023, 139, 106756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, C.L.; Zhang, D.; Guo, K.Q.; Yan, Q.X.; Zou, Z.B.; He, Z.H.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.K.; Chen, H.F.; Yang, X.W. Meroterpenthiazole A, a unique meroterpenoid from the deep-sea-derived Penicillium allii-sativi, significantly inhibited retinoid X receptor (RXR)-α transcriptional effect. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 2057–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Xie, C.L.; Xia, J.M.; Liu, Q.M.; Peng, G.; Liu, G.M.; Yang, X.W. Botryotins A–H, tetracyclic diterpenoids representing three carbon skeletons from a deep-sea-derived Botryotinia fuckeliana. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 580–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakana, D.; Hosoe, T.; Itabashi, T.; Okada, K.; de Campos Takaki, G.M.; Yaguchi, T.; Fukushima, K.; Kawai, K. New citrinin derivatives isolated from Penicillium citrinum. J. Nat. Med. 2006, 60, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deruiter, J.; Jacyno, J.M.; Davis, R.A.; Cutler, H.G. Studies on aldose reductase inhibitors from fungi. I. Citrinin and related benzopyran derivatives. J. Enzyme. Inhib. 1992, 6, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Mei, W.; Zhao, Y.; Deng, Y.; Dai, H. A new cytotoxic isocoumarin from endophytic fungus Penicillium SP. 091402 of the mangrove plant Bruguiera sexangula. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2010, 45, 805–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramata, M.; Fujioka, S.; Shimada, A.; Kawano, T.; Kimura, Y. Citrinolactones A, B and C, and sclerotinin C, plant growth regulators from Penicillium citrinum. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007, 71, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.J.; Ouyang, M.A.; Tan, Q.W. New asperxanthone and asperbiphenyl from the marine fungus Aspergillus sp. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2009, 65, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, M.; Menta, A.B.; Yoneyama, K.; and Kitabatake, N. A major decomposition product, citrinin H2, from citrinin on heating with moisture. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2002, 66, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.J.; Cui, C.B.; Li, C.W.; Wu, C.J.; Tian, C.K.; Hua, W. Activation of the dormant secondary metabolite production by introducing gentamicin-resistance in a marine-derived Penicillium purpurogenum G59. Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 559–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.F.; Di, Y.T.; Wang, Y.H.; Tan, C.J.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.T.; Li, L.; He, H.P.; Li, S.L.; Hao, X.J. Anthraquinones and Lignans from Cassia occidentalis. Helv. Chim. Acta 2010, 93, 1795–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Le, T.C.; Han, S.A.; Hillman, P.F.; Hong, A.; Hwang, S.; Du, Y.E.; Kim, H.; Oh, D.C.; Cha, S.S.; Lee, J.; Nam, S.J.; Fenical, W. Saccharobisindole, neoasterric methyl ester, and 7-chloro-4(1H)-quinolone: Three new compounds isolated from the marine bacterium Saccharomonospora sp. Mar. Drugs 2021, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oilawa, H. Biosynthesis of structurally unique fungal metabolite GKK1032A2: Indication of novel carbocyclic formation mechanism in polyketide biosynthesis. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 3552–3557. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.M.; Yang, J.K.; Zhu, H.J.; Cao, F. Bioactive steroids from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus flavus JK07-1. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2020, 56, 945–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Sharma, B.K.; Willett, J.L.; Erhan, S.Z.; Cheng, H.N. Room-temperature self-curing ene reactions involving soybean oil. Green Chem. 2008, 10, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, Y.; Sugimoto, S.; Matsunami, K.; Otsuka, H.; Takeda, Y.; Kawahata, M.; Yamaguchi, K. Microtropins A-I: 6'-O-(2''S,3''R)-2''-ethyl-2'',3''-dihydroxybutyrates of aliphatic alcohol β-D-glucopyranosides from the branches of Microtropis japonica. Phytochemistry 2013, 87, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dheen, S.T.; Kaur, C.; Ling, E.A. Microglial activation and its implications in the brain diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2007, 14, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawji, K.S.; Mishra, M.K.; Michaels, N.J.; Rivest, S.; Stys, P.K.; Yong, V.W. Immunosenescence of microglia and macrophages: Impact on the ageing central nervous system. Brain 2016, 139, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, T.; Fernandez-Villalba, E.; Izura, V.; Lucas-Ochoa, A.M.; Menezes-Filho, N.J.; Santana, R.C.; de Oliveira, M.D.; Araujo, F.M.; Estrada, C.; Silva, V.; Costa, S.L.; Herrero, M.T. Combined 1-deoxynojirimycin and ibuprofen treatment decreases microglial activation, phagocytosis and dopaminergic degeneration in MPTP-treated mice. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2021, 16, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, T.; Chen, M.; Ge, Z.W.; Chai, W.; Li, X.C.; Zhang, Z.; Lian, X.Y. Bioactive penicipyrrodiether A, an adduct of GKK1032 analogue and phenol A derivative, from a marine-sourced fungus Penicillium sp. ZZ380. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 13395–13401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Desoky, A.H.H.; Tsukamoto, S. Marine natural products that inhibit osteoclastogenesis and promote osteoblast differentiation. J. Nat. Med. 2022, 76, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Q.F.; Yan, J.; Hu, R.; Jiang, H. Isoflurane preconditioning promotes the survival and migration of bone marrow stromal cells. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 36, 1331–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, M.; Yao, W.; Liu, R.; Lam, K.S.; Nolta, J.; Jia, J.; Panganiban, B.; Meng, L.; Zhou, P.; Shahnazari, M.; Ritchie, R.O.; Lane, N.E. Directing mesenchymal stem cells to bone to augment bone formation and increase bone mass. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.H.; Ou-Yang, H.; Yan, X.; Tang, B.W.; Fang, M.J.; Wu, Z.; Chen, J.W.; Qiu, Y.K. Open-ring butenolides from a marine-derived anti-neuroinflammatory fungus Aspergillus terreus Y10. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, S.; Yang, L.; Zhang, G.; Chen, T.; Hong, B.; Pei, S.; Shao, Z. Phenolic bisabolane and cuparene sesquiterpenoids with anti-inflammatory activities from the deep-sea-derived Aspergillus sydowii MCCC 3A00324 fungus. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 105, 104420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | 1 a | 2 b | 3 b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC | δH | δC | δH | δC | δH | |

| 1 | 75.4 CH | 5.17 s | 64.8 CH | 5.08 (d, 9.7) | 64.8 CH | 5.08 (d, 9.2) |

| 3 | 74.0 CH | 3.98 (qd, 6.9, 1.8) | 71.7 CH | 3.82 (qd, 6.6, 1.5) | 71.7 CH | 3.82 (qd, 6.6, 1.5) |

| 4 | 36.9 CH | 2.62 (qd, 6.7, 1.8) | 35.1 CH | 2.52 m | 35.2 CH | 2.51 m |

| 5 | 114.0 C | 109.5 C | 109.6 C | |||

| 6 | 160.0 C | 158.5 C | 158.5 C | |||

| 7 | 102.2 C | 101.8 C | 101.8 C | |||

| 8 | 156.7 C | 155.8 C | 155.8 C | |||

| 9 | 110.3 C | 110.7 C | 110.9 C | |||

| 10 | 143.8 C | 139.7 C | 139.8 C | |||

| 11 | 18.3 CH3 | 1.11 (d, 6.4) | 18.2 CH3 | 1.01 (d, 6.5) | 18.3 CH3 | 0.99 (d, 6.5) |

| 12 | 20.1 CH3 | 1.28 (d, 6.9) | 20.1 CH3 | 1.17 (d, 6.8) | 20.2 CH3 | 1.17 (d, 7.2) |

| 13 | 10.2 CH3 | 2.04 s | 9.5 CH3 | 1.93 s | 9.6 CH3 | 1.92 s |

| 14 | 178.2 C | 175.6 C | 175.7 C | |||

| 15 | 83.2 C | 43.1 CH2 | 2.66 m 3.23 m | 43.0 CH2 | 2.72 m 3.16 m | |

| 16 | 211.3 C | 211.9 C | 212.1 C | |||

| 17 | 25.0 CH3 | 2.30 s | 72.2 CH | 4.11 m | 72.8 CH | 4.02 m |

| 18 | 20.7 CH3 | 1.10 s | 19.2 CH3 | 1.21 (d, 7.0) | 19.0 CH3 | 1.15 (d, 7.2) |

| 6-OH | 14.64 s | 14.62 s | ||||

| 8-OH | 15.16 s | 15.13 s | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).