Submitted:

20 September 2023

Posted:

22 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

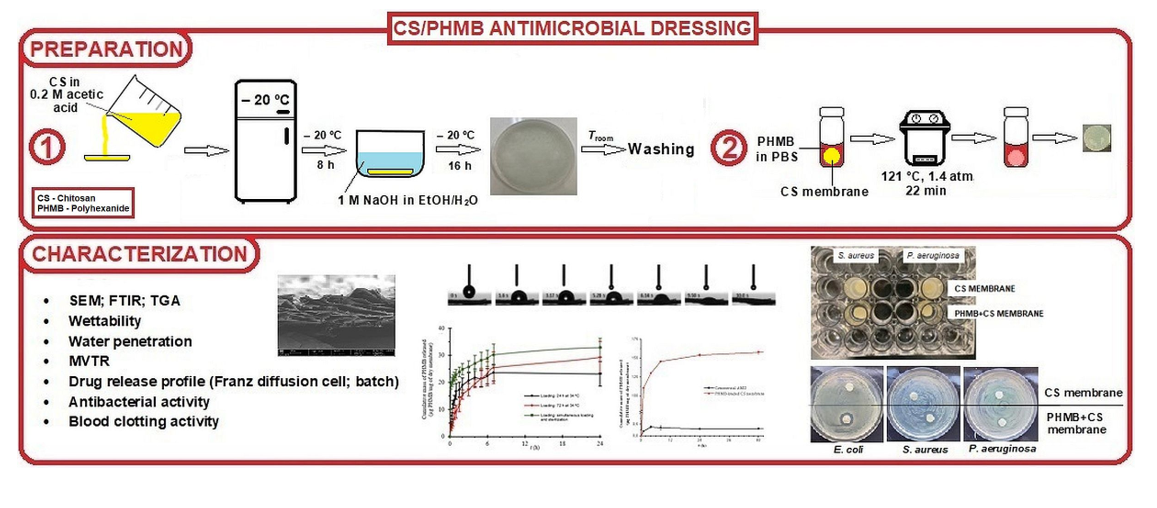

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of CS membranes

2.2. PHMB loading

2.3. PHMB quantification

2.4. Physicochemical characterization of the prepared membranes

2.4.1. Morphology of cross-sections

2.4.2. Membrane thickness and swelling capacity

2.4.3. Contact angle goniometry and drop penetration rate

2.4.4. Moisture vapor transmission rate

2.4.5. Thermogravimetric analysis

2.4.6. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

2.5. PHMB release

2.5.1. PHMB release from a single face

2.5.2. PHMB release in batch

2.6. Biological characterization

2.6.1. Antibacterial activity

2.6.2. Blood clotting activity

2.7. Statistical analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical characterization

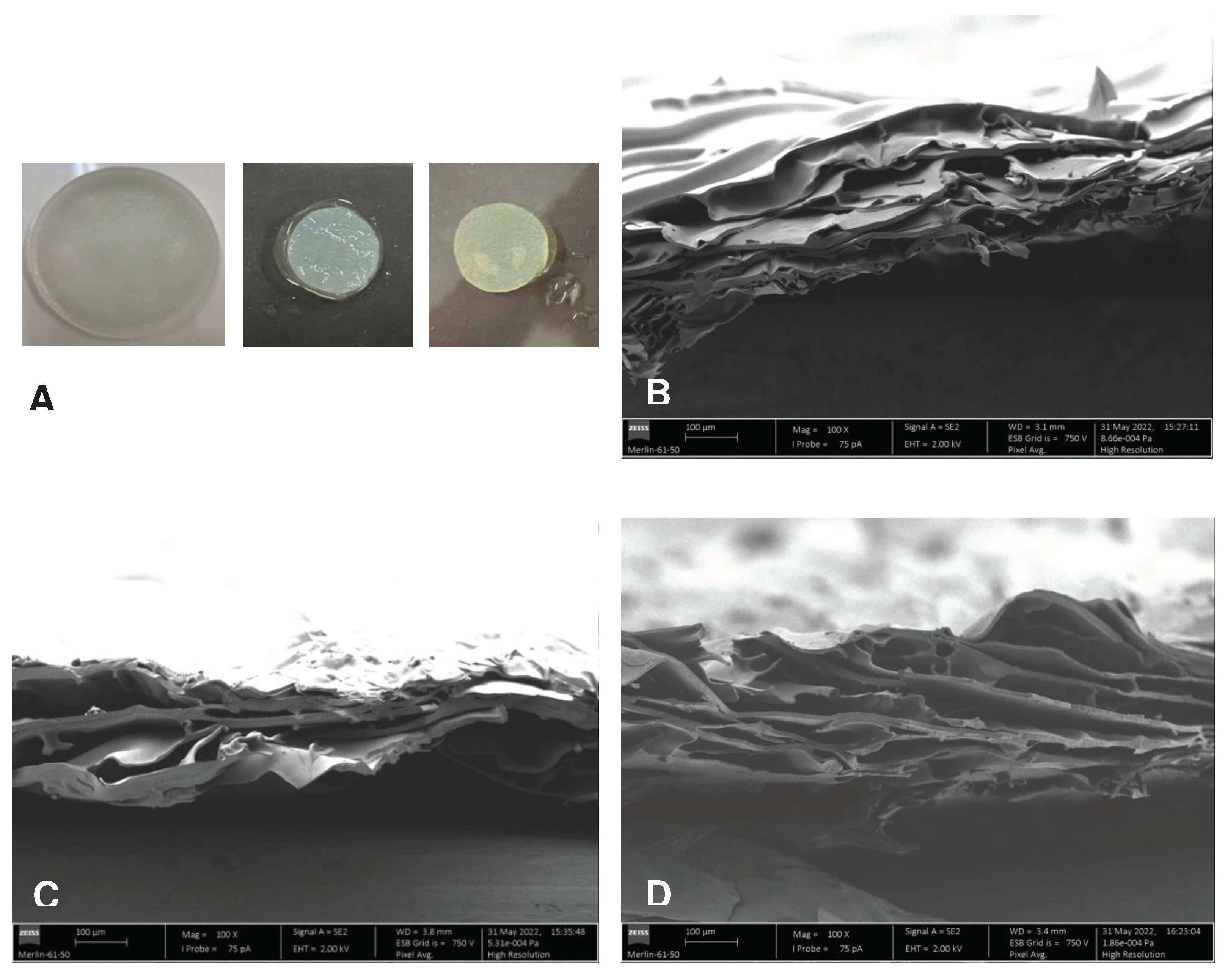

3.1.1. Morphology

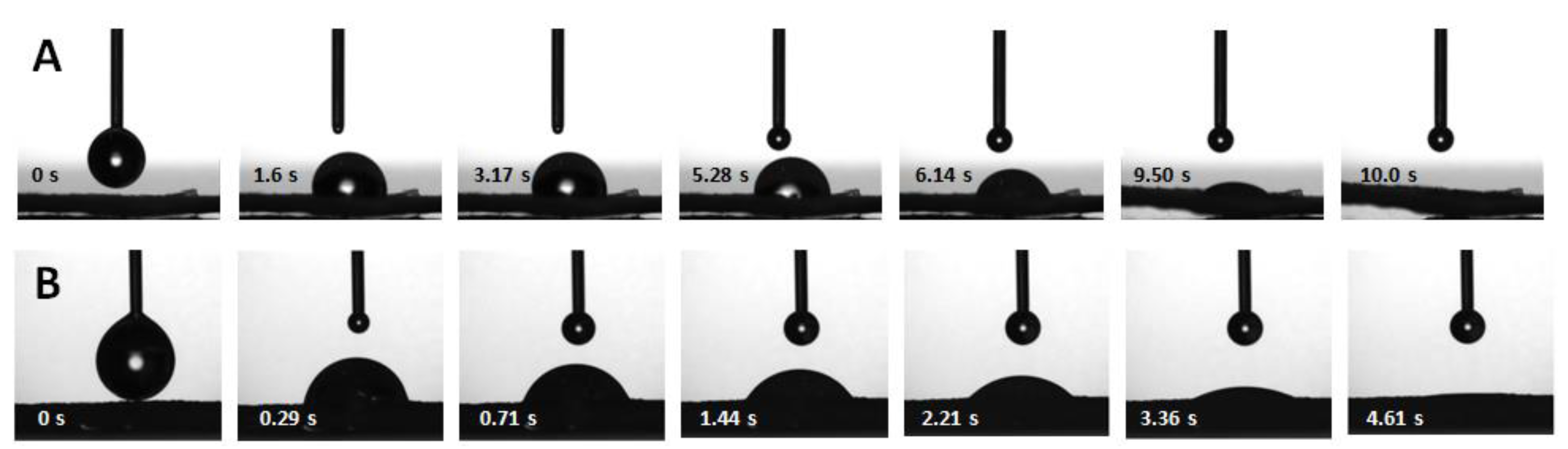

3.1.2. Wettability

3.1.3. Water penetration

3.1.4. MVTR

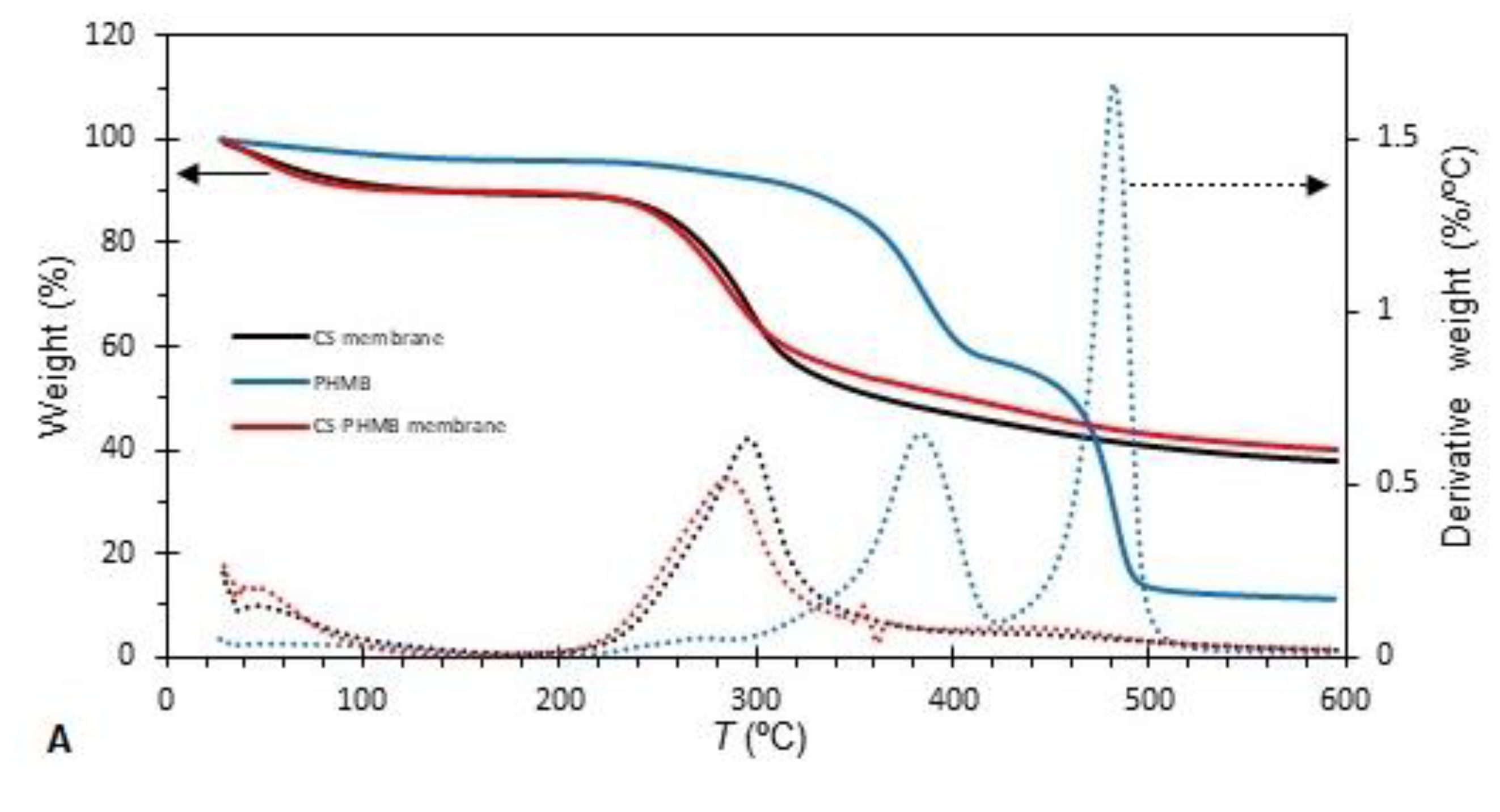

3.1.5. TGA

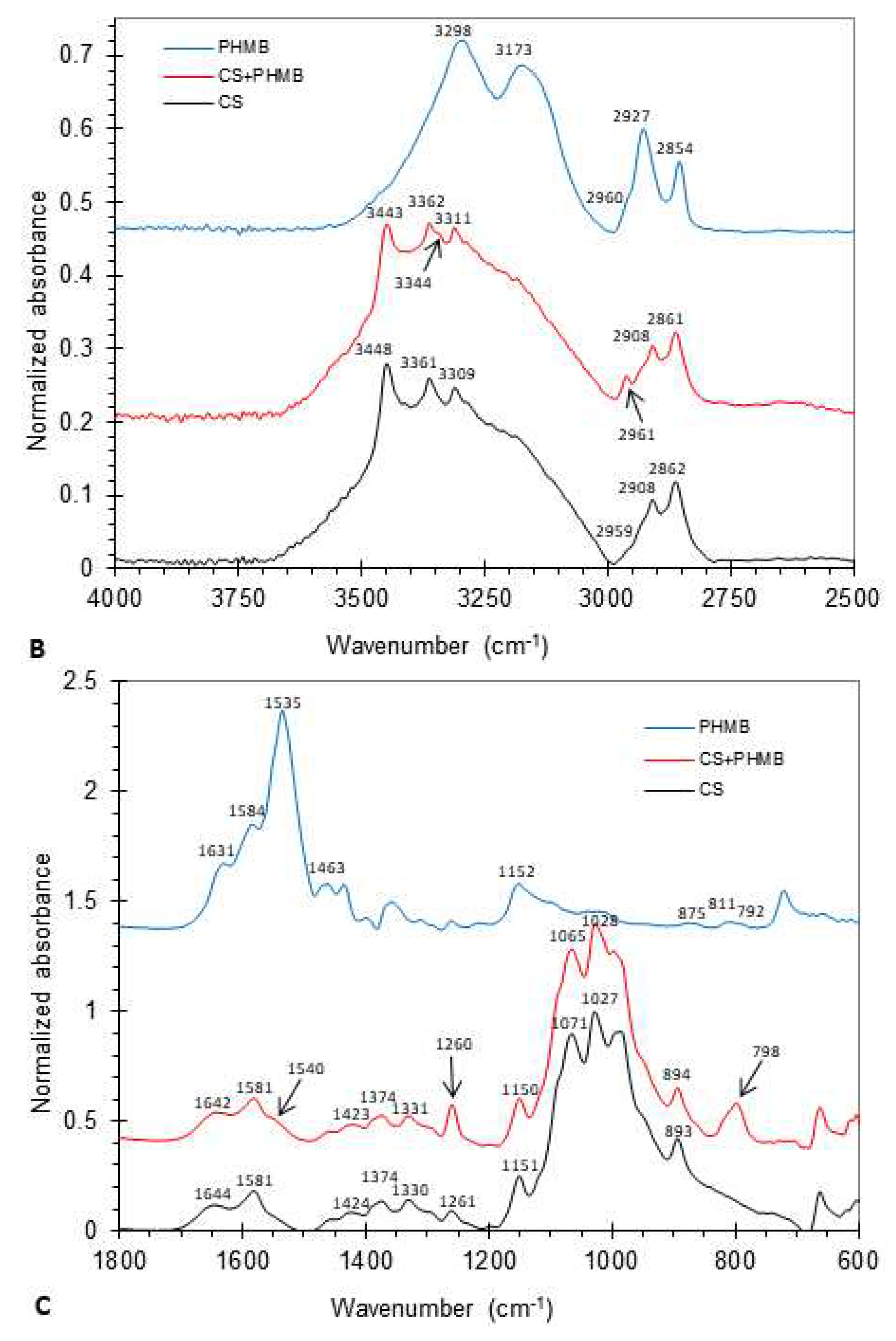

3.1.6. FTIR

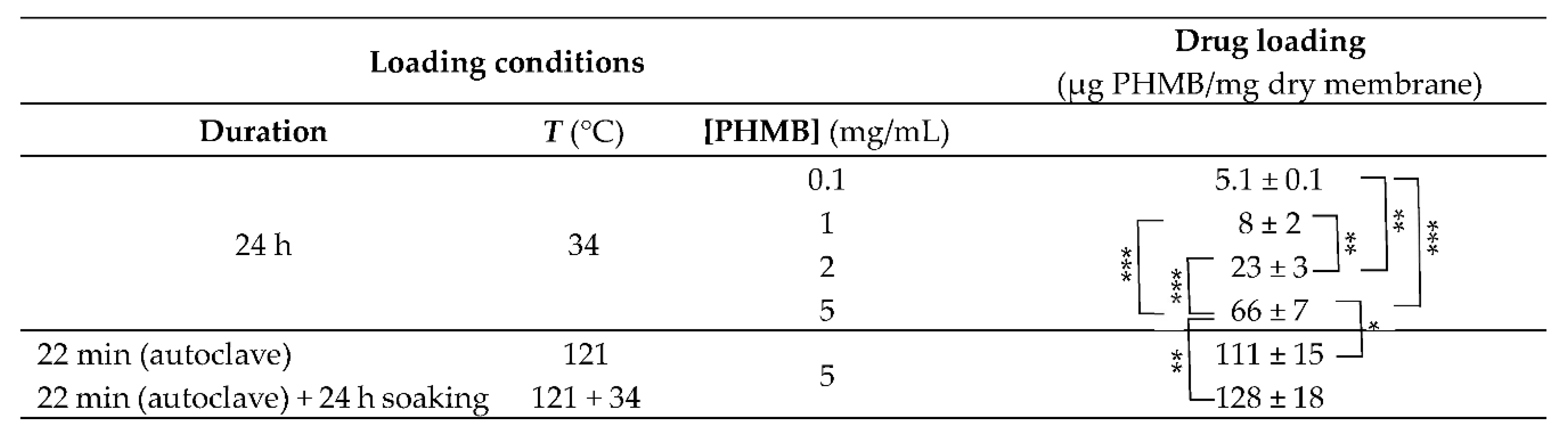

3.1.7. PHMB loading

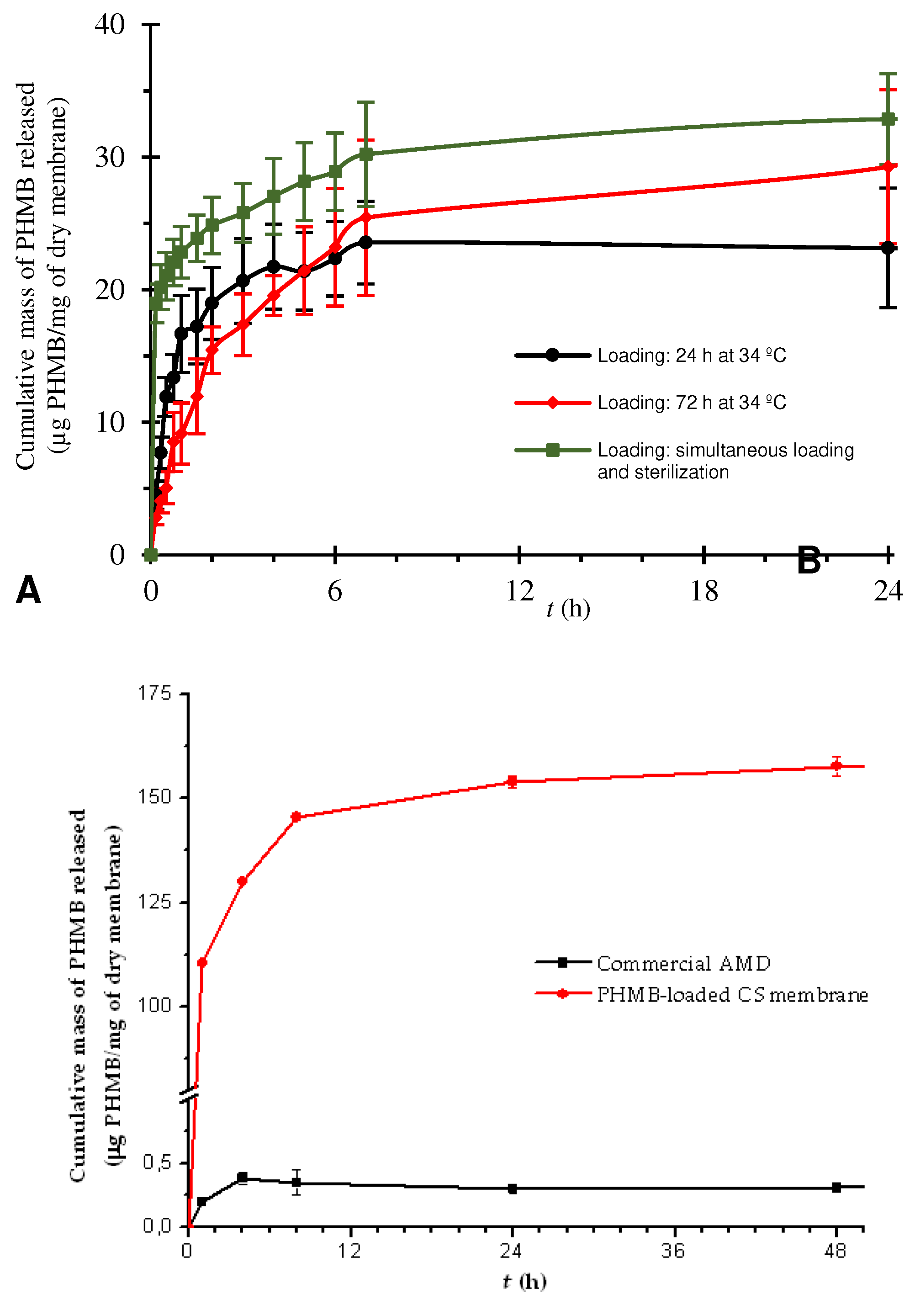

3.1.8. PHMB release

3.1.9. Assay of a commercial PHMB-releasing AMD

3.2. Biological characterization

3.2.1. Antibacterial activity of PHMB in solution

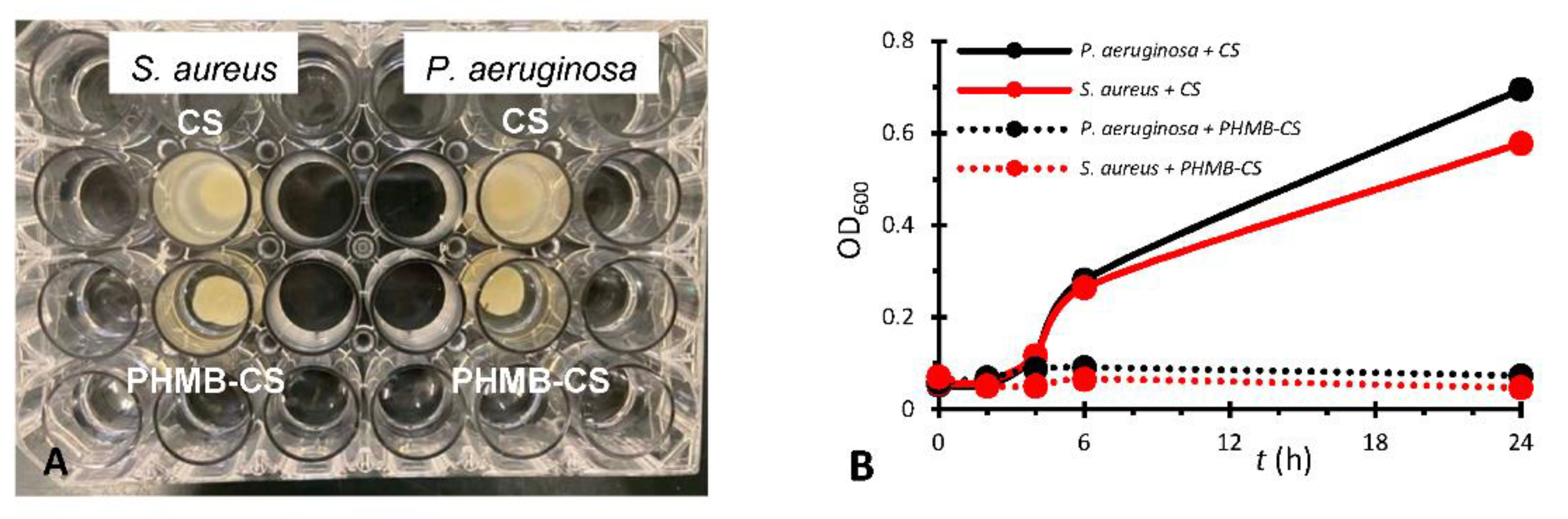

3.2.2. Antibacterial activity of the membranes on bacterial suspensions

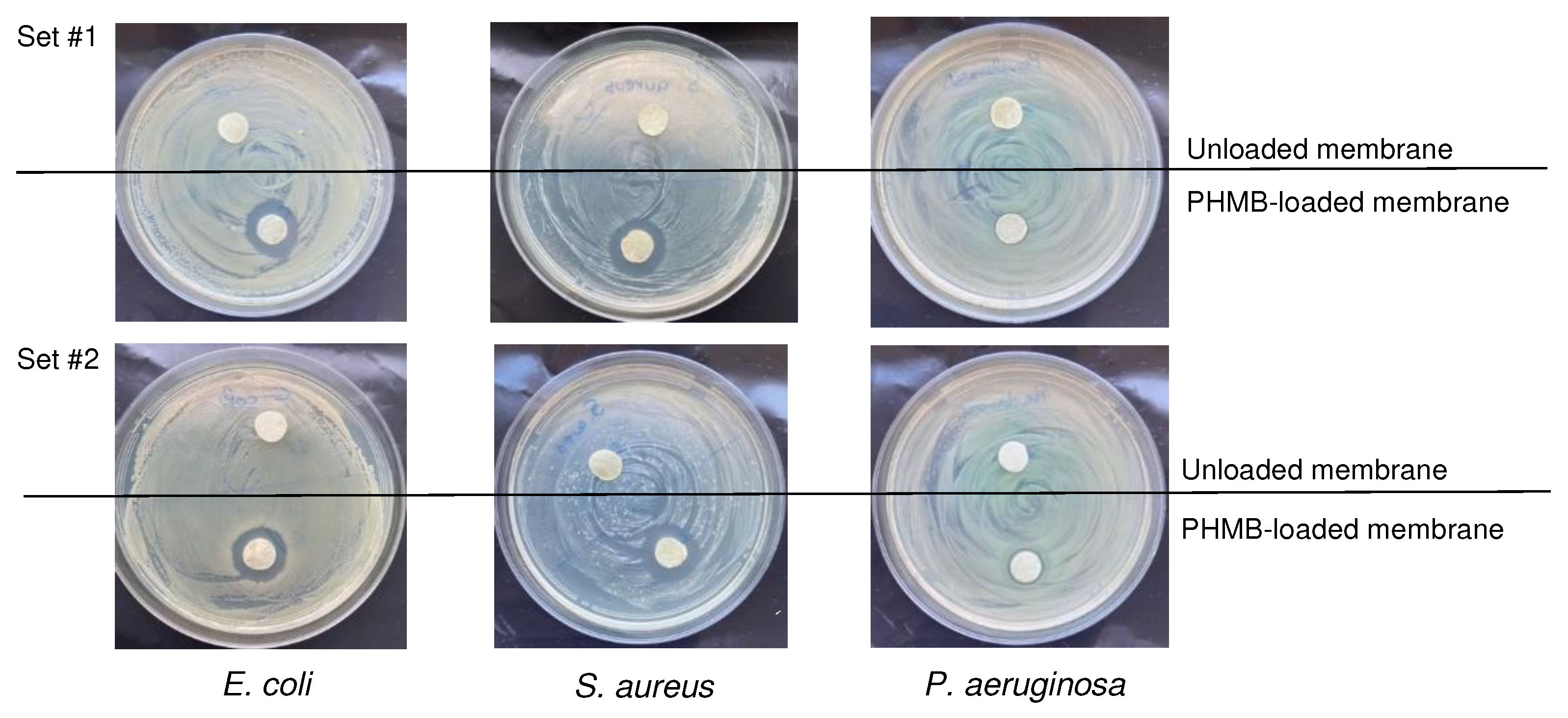

3.2.4. Antibacterial activity of the membranes on bacterial cultures on agar

3.2.5. Blood clotting activity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lazarus, G.S.; Cooper, D.M.; Knighton, D.R.; Margolis, D.J.; Pecoraro, R.E.; Rodeheaver, G.; Robson, M.C. Definitions and guidelines for assessment of wounds and evaluation of healing. JAMA Dermatol. 1994, 130, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Kosaric, N.; Bonham, C.A.; Gurtner, G.C. Wound healing: A cellular perspective. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 665–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, H.N.; Hardman, M.J. Wound healing: Cellular mechanisms and pathological outcomes. Open. Biol. 2020, 10, 200223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velnar, T.; Bailey, T.; Smrkolj, V. The wound healing process: An overview of the cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Int. Med. Res. 2009, 37, 1528–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, C.K. Human wound and its burden: Updated 2020 compendium of estimates. Adv. Wound Care 2021, 10, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunjikuttan, R.V.P.; Jayasree, A.; Biswas, R.; Jayakumar, R. Recent developments in drug-eluting dressings for the treatment of chronic wounds. Exp. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2016, 13, 1645–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.R.; Wang, Y. Drug delivery systems for wound healing. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2015, 16, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Settipalli, S. A robust market rich with opportunities: Advanced wound dressings. Available online: https://www.pm360online.com/a-robust-market-rich-with-opportunities-advanced-wound-dressings/ (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- WoundSource. Woundsource: The kestrel wound product sourcebook. Available online: https://www.woundsource.com/ (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Ji, M.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, F.; Man, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Peng, S.; Wang, S. Advances in chitosan-based wound dressings: Modifications, fabrications, applications and prospects. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 297, 120058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhi, R. Drug delivery applications of chitin and chitosan: A review. Environm. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercy, H.E.; Halim, A.M.A.; Hussein, A.A. Chitosan-derivatives as hemostatic agents: Their role in tissue regeneration. Regen. Res. 2012, 1, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, S.; Peters, L.; Mucalo, M. Chitosan: A review of molecular structure, bioactivities and interactions with the human body and micro-organisms. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 282, 119132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maliki, S.; Sharma, G.; Kumar, A.; Moral-Zamorano, M.; Moradi, O.; Baselga, J.; Stadler, F.J.; García-Peñas, A. Chitosan as a tool for sustainable development: A mini review. Polymers 2022, 14, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhuang, S. Antibacterial activity of chitosan and its derivatives and their interaction mechanism with bacteria: Current state and perspectives. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 138, 109984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, Y.; Yano, R.; Miyatake, K.; Tomohiro, I.; Shigemasa, Y.; Minami, S. Effects of chitin and chitosan on blood coagulation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2003, 53, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrulea, V.; Ostafe, V.; Borchard, G.; Jordan, O. Chitosan as a starting material for wound healing applications. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015, 97, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, T.; Tanaka, M.; Huang, Y.Y.; Hamblin, M.R. Chitosan preparations for wounds and burns: Antimicrobial and wound-healing effects. Expert. Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2011, 9, 857–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-Y.; Tsai, S.-P.; Ho, M.-H.; Wang, D.-M.; Liu, C.-E.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Tseng, H.-C.; Hsieh, H.-J. Analysis of freeze-gelation and cross-linking processes for preparing porous chitosan scaffolds. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 67, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaehn, K. Polihexanide: A safe and highly effective biocide. Skin. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2010, 23, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, A.; Dissemond, J.; Kim, S.; Willy, C.; Mayer, D.; Papke, R.; Tuchmann, F.; Assadian, O. Consensus on wound antisepsis: Update 2018. Skin. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2018, 31, 28–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernauer, U.; Bodin, L.; Celleno, L.; Chaudhry, Q.; Coenraads, P.-J.; Dusinska, M.; Duus-Johansen, J.; Ezendam, J.; Gaffet, E.; Galli, C.L.; et al. SCCS Opinion on Polyaminopropyl Biguanide (PHMB)—Submission III, SCCS/1581/16, Preliminary Version of 23 December 2016; Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety—European Commission: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Cranston, R. Recent advances in antimicrobial treatments of textiles. Text. Res. J. 2008, 78, 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Magina, S.; Santos, M.D.; Ferra, J.; Cruz, P.; Portugal, I.; Evtuguin, D. High pressure laminates with antimicrobial properties. Materials 2016, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chivu, A.; Chindera, K.; Mendes, G.; An, A.; Davidson, B.; Good, L.; Song, W. Cellular gene delivery via poly(hexamethylene biguanide)/pDNA self-assembled nanoparticles. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2021, 158, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.-Y.; Chiou, J.-C.; Chen, W.-X.; Yu, J.-L.; Kan, C.-W. A salt-free, zero-discharge and dyebath-recyclable circular coloration technology based on cationic polyelectrolyte complex for cotton fabric dyeing. Cellulose 2022, 29, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanskiy, N.L.; Butt, M.A.; Khonina, S.N. Carbon dioxide gas sensor based on polyhexamethylene biguanide polymer deposited on silicon nano-cylinders metasurface. Sensors 2021, 21, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koburger, T.; Hübner, N.-O.; Braun, M.; Siebert, J.; Kramer, A. Standardized comparison of antiseptic efficacy of triclosan, PVP–iodine, octenidine dihydrochloride, polyhexanide and chlorhexidine digluconate. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 1712–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.; Gray, D. Using PHMB antimicrobial to prevent wound infection. Wounds UK 2007, 3, 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Hübner, N.O.; Kramer, A. Review on the efficacy, safety and clinical applications of polihexanide, a modern wound antiseptic. Skin. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2010, 23 (suppl 1), 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, D.F.; Kilvington, S.; Dart, J.K. Treatment of acanthamoeba keratitis with polyhexamethylene biguanide. Ophthalmology 1992, 99, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valluri, S.; Fleming, T.P.; Laycock, K.A.; Tarle, I.S.; Goldberg, M.A.; Garcia-Ferrer, F.J.; Essary, L.R.; Pepose, J.S. In vitro and in vivo effects of polyhexamethylene biguanide against herpes simplex virus infection. Cornea 1997, 16, 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, F.C.; Miller, S.R.; Ferguson, M.L.; Labib, M.; Rando, R.F.; Wigdahl, B. Polybiguanides, particularly polyethylene hexamethylene biguanide, have activity against human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2005, 59, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F.; Maillard, J.-Y.; Denyer, S.P.; McGeechan, P. Polyhexamethylene biguanide exposure leads to viral aggregation. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 108, 1880–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, A.; Roth, B.; Müller, G.; Rudolph, P.; Klöcker, N. Influence of the antiseptic agents polyhexanide and octenidine on fl cells and on healing of experimental superficial aseptic wounds in piglets. A double-blind, randomised, stratified, controlled, parallel-group study. Skin. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2004, 17, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, P.; Moore, L.E. Cationic antiseptics: Diversity of action under a common epithet. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 99, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glukhov, E.; Stark, M.; Burrows, L.L.; Deber, C.M. Basis for selectivity of cationic antimicrobial peptides for bacterial versus mammalian membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 33960–33967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chindera, K.; Mahato, M.; Sharma, A.K.; Horsley, H.; Kloc-Muniak, K.; Kamaruzzaman, N.F.; Kumar, S.; McFarlane, A.; Stach, J.; Bentin, T.; et al. The antimicrobial polymer PHMB enters cells and selectively condenses bacterial chromosomes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23121–23121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wessels, S.; Ingmer, H. Modes of action of three disinfectant active substances: A review. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2013, 67, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- East, G.C.; McIntyre, J.E.; Shao, J. Polybiguanides: Synthesis and characterization of polybiguanides containing hexamethylene groups. Polymer 1997, 38, 3973–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küsters, M.; Beyer, S.; Kutscher, S.; Schlesinger, H.; Gerhartz, M. Rapid, simple and stability-indicating determination of polyhexamethylene biguanide in liquid and gel-like dosage forms by liquid chromatography with diode-array detection. J. Pharm. Anal. 2013, 3, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiomar, A.J.; Urbano, A.M. Polyhexanide-releasing membranes for antimicrobial wound dressings: A critical review. Membranes 2022, 12, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paula, G.F.; Netto, G.I.; Mattoso, L.H.C. Physical and chemical characterization of poly(hexamethylene biguanide) hydrochloride. Polymers 2011, 3, 928–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilamian, M.; Montazer, M.; Masoumi, J. Antimicrobial electrospun membranes of chitosan/poly(ethylene oxide) incorporating poly(hexamethylene biguanide) hydrochloride. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 94, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, C.Z.; Moraes, A.M. Influence of the incorporation of the antimicrobial agent polyhexamethylene biguanide on the properties of dense and porous chitosan-alginate membranes. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2018, 93, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abri, S.; Ghatpande, A.A.; Ress, J.; Barton, H.A.; Leipzig, N.D. Polyionic complexed antibacterial heparin–chitosan particles for antibiotic delivery. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2019, 2, 5848–5858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Y.; Qian, Z.; Yin, Y.; Yuan, W.; Wu, F.; Jin, T. Polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan/polyhexamethylene biguanide phase separation system: A potential topical antibacterial formulation with enhanced antimicrobial effect. Molecules 2020, 25, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, I.S.; Ooi, C.W.; Liu, B.L.; Peng, C.T.; Chiu, C.Y.; Chang, Y.K. Antibacterial efficacy of chitosan- and poly(hexamethylene biguanide)-immobilized nanofiber membrane. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 154, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massarelli, E.; Silva, D.; Pimenta, A.F.R.; Fernandes, A.I.; Mata, J.L.G.; Armes, H.; Salema-Oom, M.; Saramago, B.; Serro, A.P. Polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan wound dressings loaded with antiseptics. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 593, 120110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.J.; Chien, B.Y.C.; Lee, Y.H. Injectable and thermoresponsive hybrid hydrogel with antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, oxygen transport, and enhanced cell growth activities for improved diabetic wound healing. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.A.; Zhang, J.; Feng, X.J.; Du, Z.G.; Jiang, Y.Z.; Shi, Y.D.; Yang, G.H.; Tan, L. Polyhexamethylene biguanide chemically modified cotton with desirable hemostatic, inflammation-reducing, intrinsic antibacterial property for infected wound healing. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 2975–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Lin, S.J. Chitosan/PVA hetero-composite hydrogel containing antimicrobials, perfluorocarbon nanoemulsions, and growth factor-loaded nanoparticles as a multifunctional dressing for diabetic wound healing: Synthesis, characterization, and in vitro/in vivo evaluation. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EN 13726-2:2002; Test Methods for PrimaryWound Dressings. Part 2—Moisture Vapour Transmission Rate of Permeable Film Dressings. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2002.

- Franz, T.J. Percutaneous absorption on the relevance of in vitro data. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1975, 64, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, Y.; Nose, Y. A new method for evalution of antithrombogenicity of materials. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1972, 6, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groth, T.; Derdau, K.; Strietzel, F.; Foerster, F.; Wolf, H. The haemocompatibility of biomaterials in vitro: Investigations on the mechanism of the whole-blood clot formation test. Altern. Lab. Anim. 1992, 20, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minsart, M.; Van Vlierberghe, S.; Dubruel, P.; Mignon, A. Commercial wound dressings for the treatment of exuding wounds: An in-depth physico-chemical comparative study. Burns Trauma 2022, 10, tkac024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, P.E.; Neilson, G.W.; Enderby, J.E.; Saboungi, M.-L.; Dempsey, C.E.; MacKerell, A.D.; Brady, J.W. The structure of aqueous guanidinium chloride solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 11462–11470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, R.S.; Harvey, A.; Kettle, L.L.; Payne, J.D.; Russell, S.J. Sorption of poly(hexamethylenebiguanide) on cellulose: Mechanism of binding and molecular recognition. Langmuir 2006, 22, 5636–5644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogler, E.A. On the origins of water wetting terminology. In Water in biomaterials surface science; Morra, M., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK,, 2001; pp. 149–182. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Pan, X.; Ling, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, R. Facile fabrication of chitosan active film with xylan via direct immersion. Cellulose 2014, 21, 1873–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, R.N. Resistance of solid surfaces to wetting by water. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1936, 28, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassie, A.B.D.; Baxter, S. Wettability of porous surfaces. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1944, 40, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Elimelech, M.; Lin, S. Environmental applications of interfacial materials with special wettability. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 2132–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainbridge, P.; Browning, P.; Bernatchez, S.F.; Blaser, C.; Hitschmann, G. Comparing test methods for moisture-vapor transmission rate (MVTR) for vascular access transparent semipermeable dressings. J. Vasc. Access 2021, 11297298211050485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehrer, C.L.; Holm, D.; Solfest, S.E.; Walters, S.-A. A comparison of the in vitro moisture vapour transmission rate and in vivo fluid-handling capacity of six adhesive foam dressings to a newly reformulated adhesive foam dressing. Int. Wound J. 2014, 11, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Wang, F.-Y.; Mao, C.-F.; Yang, C.-H. Studies of chitosan. I. Preparation and characterization of chitosan/poly(vinyl alcohol) blend films. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 105, 1086–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, V.; Salvo, P.; Janowska, A.; Di Francesco, F.; Barbini, A.; Romanelli, M. Correlation between wound temperature obtained with an infrared camera and clinical wound bed score in venous leg ulcers. Wounds 2015, 27, 274–278. [Google Scholar]

- Hellgren, L.; Vincent, J. Degradation and liquefaction effect of streptokinase-Streptodornase and stabilized trypsin on necroses, crusts of fibrinoid, purulent exudate and clotted blood from leg ulcers. J. Int. Med. Res. 1977, 5, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamke, L.O.; Nilsson, G.E.; Reithner, H.L. The evaporative water loss from burns and the water-vapour permeability of grafts and artificial membranes used in the treatment of burns. Burns 1977, 3, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Osman, O.; Mahmoud, A.A. Spectroscopic analyses of cellulose and chitosan: FTIR and modeling approach. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 2011, 8, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauricio-Sanchez, R.A.; Salazar, R.; Luna-Barcenas, J.G.; Mendoza-Galvan, A. Ftir spectroscopy studies on the spontaneous neutralization of chitosan acetate films by moisture conditioning. Vib. Spectrosc. 2018, 94, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, S.; Muthusamy, S.; Nagarajan, S.; Nath, A.V.; Savarimuthu, J.S.; Jayaprakash, J.; Gurunadhan, R.M. Fabrication of collagen with polyhexamethylene biguanide: A potential scaffold for infected wounds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2022, 110, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheela, N.R.; Muthu, S.; Krishnan, S.S. Ftir, ft raman and uv-visible spectroscopic analysis on metformin hydrochloride. Asian J. Chem. 2010, 22, 5049–5056. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, A.M.; Silva, S.Y.S.; Oliveira, M.N.; de Oliveira, G.C.A.; Novais, A.L.F.; de Paula, G.F.; Souza, D.N.; Belo, E.A.; Gester, R.; Andrade-Filho, T. Prediction of electronic and vibrational properties of poly(hexamethylene biguanide) hydrochloride: A combined theoretical and experimental investigation. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1246, 131176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, L.J. Alkanes. In The infra-red spectra of complex molecules, 3rd ed.; Chapman & Hall: London, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Nga, N.K.; Chinh, H.D.; Hong, P.T.T.; Huy, T.Q. Facile preparation of chitosan films for high performance removal of reactive blue 19 dye from aqueous solution. J. Polym. Environ. 2017, 25, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsley, A.; Vassileva, K.; Tsui, J.; Song, W.H.; Good, L. Polyhexamethylene biguanide:Polyurethane blend nanofibrous membranes for wound infection control. Polymers 2019, 11, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrie, G.; Keen, I.; Drew, B.; Chandler-Temple, A.; Rintoul, L.; Fredericks, P.; Grøndahl, L. Interactions between alginate and chitosan biopolymers characterized using ftir and xps. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 2533–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, S.; Tanıs, E. Toxic potential of poly-hexamethylene biguanide hydrochloride (PHMB): A dft, aim and nci analysis study with solvent effects. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2022, 1212, 113709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens, E.; Calderon, S.; del Valle, L.J.; Puiggali, J. Polybiguanide (PHMB) loaded in PLA scaffolds displaying high hydrophobic, biocompatibility and antibacterial properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2015, 50, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baynes, J.W. The Maillard reaction: Chemistry, biochemistry and implications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 14527–14528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leceta, I.; Guerrero, P.; de la Caba, K. Functional properties of chitosan-based films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 93, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gethin, G.; Ivory, J.D.; Sezgin, D.; Muller, H.; O'Connor, G.; Vellinga, A. What is the "normal" wound bed temperature? A scoping review and new hypothesis. Wound Repair Regen. 2021, 29, 843–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, S.; Imai, R.; Ida, Y.; Shibata, D.; Komiya, T.; Matsumura, H. Increased wound pH as an indicator of local wound infection in second degree burns. Burns 2015, 41, 820–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Union of Wound Healing Societies (WUWHS). Consensus Document. Wound Exudate: Effective Assessment and Management; Wounds International: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Pharmacopoeia 6.0. Dissolution Test for Solid Dosage Forms (01/2008:20903); European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & Health Care, Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2008; pp. 266–275. [Google Scholar]

- Steffansen, B.; Herping, S.P.K. Novel wound models for characterizing ibuprofen release from foam dressings. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 364, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health, C. Cardinal Health™ Telfa™ AMD antimicrobial non-adherent dry dressings. Available online: https://www.cardinalhealth.com/en/product-solutions/medical/skin-and-wound-management/traditional-wound-care/non-adherent-dry-dressings/telfa-amd-dressings.html (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Cutting, K.F. Wound exudate: Composition and functions. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2003, 8, suppl 4-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.T. Testing dressings and wound management materials. In Advanced textiles for wound care; Rajendran, S., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Limited:: Cambridge, U.K., 2009; pp. 20–47. [Google Scholar]

- WoundSource. Woundsource product guide - telfa amd antimicrobial dressings. Available online: https://www.woundsource.com/product/telfa-amd-antimicrobial-dressings (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Puca, V.; Marulli, R.Z.; Grande, R.; Vitale, I.; Niro, A.; Molinaro, G.; Prezioso, S.; Muraro, R.; Di Giovanni, P. Microbial species isolated from infected wounds and antimicrobial resistance analysis: Data emerging from a three-years retrospective study. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, P.A. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. R. Soc. Med. 2002, 95, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fabry, W.H.K.; Kock, H.J.; Vahlensieck, W. Activity of the antiseptic polyhexanide against Gram-negative bacteria. Microb. Drug. Resist. 2014, 20, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabry, W.; Kock, H.J. In-vitro activity of polyhexanide alone and in combination with antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus. J. Hosp. Infect. 2014, 86, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Property | Dry membrane | Hydrated membrane |

|---|---|---|

| Thickness (µm, n = 3) After autoclaving |

220 ± 24 –* |

1200 ± 235 770 ± 100 |

| Swelling capacity (%; n = 3) | 748 ± 23 | –* |

| Water contact angle (°; n = 3) | 97 ± 2 | 82 ± 6 |

| Drop penetration time (s; n = 3) | 11 ± 4 | 4.1 ± 0.6 |

| Drop penetration rate(s) (mm/s; n = 4–5) | 0.02 ± 0.01; 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.05 |

| MVTR (g H2O/m2/24 h) | ||

| Contact with water vapor (n = 6) | 7470 ± 393 | –* |

| Contact with water (n = 6) | 34400 ± 5400 | –* |

| Sample | Main transition | Secondary transition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To (°C) | Ti (°C) | Te (°C) | To (°C) | Ti (°C) | Te (°C) | |

| Unloaded CS membrane | 263 | 296 | 333 | –* | –* | –* |

| PHMB | 469 | 482 | 491 | 357 | 383 | 401 |

| PHMB-loaded CS membrane | 250 | 285 | 308 | 420 | 449 | 476 |

| Band position (cm–1) | Assignment* | References* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | CS+PHMB | PHMB | ||

| 3448 | 3443 | – | OH stretching | [71,72] |

| 3361 | 3362 | |||

| – | 3344 | – | NH stretching | [73] |

| 3309 | 3311 | [72] | ||

| – | – | 3298 | [74,75] | |

| – | – | 3173 | Symmetric NH stretching | [74] |

| 2960 | 2961 | 2959 | CH asymmetric stretching in CH3 | [76] |

| 2908 | 2908 | – | CH stretching in CH3, CH2 and CH | [72,77]; [73,78] |

| – | – | 2927 | ||

| 2862 | 2861 | 2854 | ||

| 1644 | 1642 | 1631 | Amide I (CS); NH deformation or C=N stretching (PHMB) | [77,79]; [74] |

| 1581 | 1581 | 1584 | Amide II (CS); NH+ bending (PHMB) | [72]; [80] |

| – | 1540 | 1535 | NH bending | [81] |

| – | 1463 | C=N stretching | [81] | |

| 1424 | 1423 | – | CH2 bending | [72] |

| 1374 | 1374 | CH3 symmetric bending | [79] | |

| 1330 | 1331 | – | Amide III and CH2 wagging | [72] |

| 1261 | 1260 | NHCO vibration | [77] | |

| 1151 | 1150 | 1152 | C–O stretching in C–O–C vibrations and C–N stretching (CS); C–N stretching and H–N–C bending (PHMB) | [71,77,79]; [75,80] |

| 1065 | 1065 | – | ||

| 1027 | 1028 | |||

| 893 | 894 | – | CN vibration and vibration of the saccharide structure | [71,77] |

| – | 798 | 811+792 | NH2 rocking and NH wagging | [74] |

|

| Bacteria | MIC | Inhibition halo diameter (cm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHMB solution sterilized by membrane filtration (μg/mL) | PHMB solution sterilized by autoclaving (μg/mL) |

||

| E. coli | 3.1a | 3.1a | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

| S. aureus | 3.1a | 3.1a | 1.9 ± 0.1 |

| P. aeruginosa | 12.5a | 12.5a | 1.2a |

| Membrane type | Thrombosis degree (%) |

|---|---|

| Unloaded | 54 ± 14* |

| Loaded with PHMB by soaking/autoclaving | 28 ± 2* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).