Submitted:

19 September 2023

Posted:

21 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

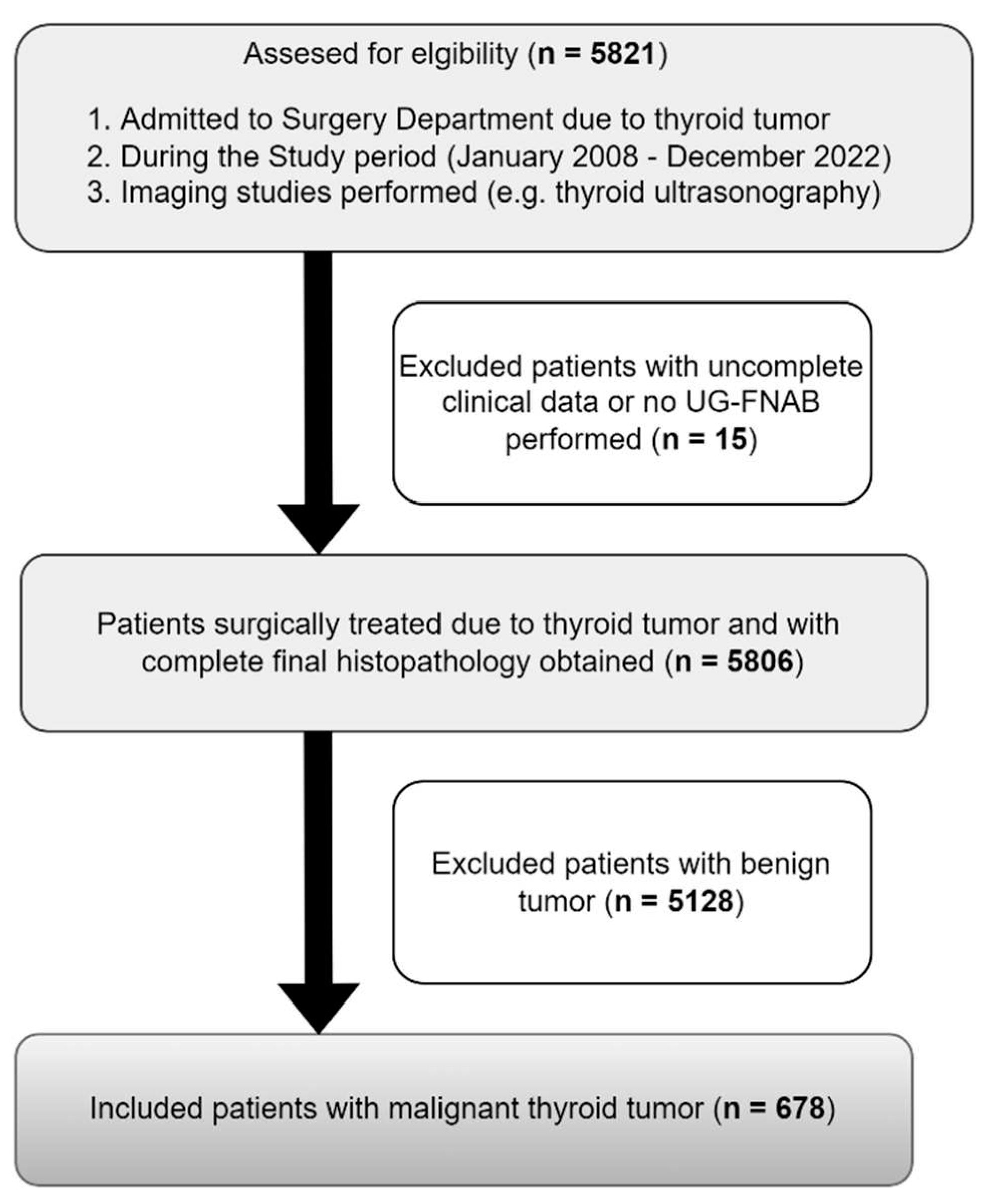

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chmielik, E.; Rusinek, D.; Oczko-Wojciechowska, M.; Jarzab, M.; Krajewska, J.; Czarniecka, A.; Jarzab, B. Heterogeneity of thyroid cancer. Pathobiology 2018, 85, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Devesa, S.S.; Sosa, J.A.; Check, D.; Kitahara, C.M. Trends in thyroid cancer incidence and mortality in the United States, 1974-2013. JAMA 2017, 317, 1338–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haymart, M.R.; Banerjee, M.; Reyes-Gastelum, D.; Caoili, E.; Norton, E.C. Thyroid ultrasound and the increase in diagnosis of low-risk thyroid cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albi, E.; Cataldi, S.; Lazzarini, A.; Codini, M.; Beccari, T.; Ambesi-Impiombato, F.; Curcio, F. Radiation and thyroid cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cibas, E.S.; Ali, S.Z. The Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2009, 132, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibas, E.S.; Ali, S.Z. The 2017 Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology. J. Am. Soc. Cytopathol. 2017, 6, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krane, J.F.; Nayar, R.; Renshaw, A.A. ypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance. In The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology: Definitions, criteria, and explanatory notes, 2nd ed.; Ali, S.Z., Cibas, E.S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Switzerland, 2017; pp. 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Dong, Y.; Hu, S.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, B.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, G.; et al. Risk factors for high-volume lymph node metastases in cN0 papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Gland Surg. 2019, 8, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Xia, Y.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, G.; Liu, N.; Shang, Z.; Yang, J.; et al. Ultrasonography for the prediction of high-volume lymph node metastases in papillary thyroid carcinoma: Should surgeons believe ultrasound results? World J. Surg. 2020, 44, 4142–4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzato, M.; Li, M.; Vignat, J.; Laversanne, M.; Singh, D.; La Vecchia, C.; Vaccarella, S. The epidemiological landscape of thyroid cancer worldwide: GLOBOCAN estimates for incidence and mortality rates in 2020. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliszewski, K.; Diakowska, D.; Wojtczak, B.; Migoń, J.; Kasprzyk, A.; Rudnicki, J. The occurrence of and predictive factors for multifocality and bilaterality in patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Medicine 2019, 98, e15609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schopper, H.K.; Stence, A.; Ma, D.; Pagedar, N.A.; Robinson, R.A. Single thyroid tumour showing multiple differentiated morphological patterns and intramorphological molecular genetic heterogeneity. J. Clin. Pathol. 2017, 70, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gospodarowicz, M.; Mackillop, W.; O'Sullivan, B.; Sobin, L.; Henson, D.; Hutter, R.V.; Wittekind, C. Prognostic factors in clinical decision making. Cancer 2001, 91, 1688–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliszewski, K. Does every classical type of well-differentiated thyroid cancer have excellent prognosis? A case series and literature review. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 2441–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eustatia-Rutten, C.F.A.; Corssmit, E.P.M.; Biermasz, N.R.; Pereira, A.M.; Romijn, J.A.; Smit, J.W. Survival and death causes in differentiated thyroid carcinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzaferri, E.L.; Kloos, R.T. Clinical review 128: Current approaches to primary therapy for papillary and follicular thyroid cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 1447–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, R.; Sasaki, J.; Kurihara, H.; Suzuki, K.; Iida, Y.; Kawaoi, A. Multiple thyroid involvement (intraglandular metastasis) in papillary thyroid carcinoma. A clinicopathologic study of 105 consecutive patients. Cancer 1992, 70, 1585–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, E.; Teller, L.; Piana, S.; Rosai, J.; Merino, M.J. Different clonal origin of bilateral papillary thyroid carcinoma, with a review of the literature. Endocr. Pathol. 2012, 23, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Teng, X.; Wang, H.; Mao, C.; Teng, R.; Zhao, W.; Cao, J.; Fahey, T.J.; Teng, L. Clonal analysis of bilateral, recurrent, and metastatic papillary thyroid carcinomas. Hum. Pathol. 2010, 41, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shattuck, T.M.; Westra, W.H.; Ladenson, P.W.; Arnold, A. Independent clonal origins of distinct tumor foci in multifocal papillary thyroid carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 2406–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasko, V.; Hu, S.; Wu, G.; Xing, J.C.; Larin, A.; Savchenko, V.; Trink, B.; Xing, M. High prevalence and possible de novo formation of BRAF mutation in metastasized papillary thyroid cancer in lymph nodes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 5265–5269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/thyro.html.

- Kaliszewski, K.; Diakowska, D.; Wojtczak, B.; Rudnicki, J. Cancer screening activity results in overdiagnosis and overtreatment of papillary thyroid cancer: A 10-year experience at a single institution. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0236257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, B.R.; Alexander, E.K.; Bible, K.C.; Doherty, G.M.; Mandel, S.J.; Nikiforov, Y.E.; Pacini, F.; Randolph, G.W.; Sawka, A.M.; Schlumberger, M.; et al. 2015 American thyroid association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: The American thyroid association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2016, 26, 1–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.B.; Xu, H.X.; Zhang, Y.F.; Guo, L.H.; Xu, S.H.; Zhao, C.K.; Liu, B.J. Comparisons of ACR TI-RADS, ATA guidelines, Kwak TI-RADS, and KTA/KSThR guidelines in malignancy risk stratification of thyroid nodules. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2020, 75, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Londero, S.C.; Krogdahl, A.; Bastholt, L.; Overgaard, J.; Pedersen, H.B.; Hahn, C.H.; Bentzen, J.; Schytte, S.; Christiansen, P.; Gerke, O.; et al. Papillary thyroid carcinoma in Denmark, 1996–2008: Outcome and evaluation of established prognostic scoring systems in a prospective national cohort. Thyroid 2015, 25, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leboulleux, S.; Tuttle, R.M.; Pacini, F.; Schlumberger, M. Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: Time to shift from surgery to active surveillance? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, Y.; Miyauchi, A.; Kihara, M.; Higashiyama, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Miya, A. Patient age is significantly related to the progression of papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid under observation. Thyroid 2014, 24, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Miyauchi, A. Active surveillance as first-line management of papillary microcarcinoma. Annu. Rev. Med. 2019, 70, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Miyauchi, A.; Kudo, T.; Oda, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Sasai, H.; Masuoka, H.; Fukushima, M.; Higashiyama, T.; Kihara, M.; et al. Trends in the implementation of active surveillance for low-risk papillary thyroid microcarcinomas at Kuma hospital: Gradual increase and heterogeneity in the acceptance of this new management option. Thyroid 2018, 28, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; Oh, H.-S.; Kim, M.; Park, S.; Jeon, M.J.; Kim, W.G.; Kim, W.B.; Shong, Y.K.; Song, D.E.; Baek, J.H.; et al. Active surveillance for patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: A single center’s experience in Korea. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 1917–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinaro, E.; Campopiano, M.C.; Pieruzzi, L.; Matrone, A.; Agate, L.; Bottici, V.; Viola, D.; Cappagli, V.; Valerio, L.; Giani, C.; et al. Active surveillance in papillary thyroid microcarcinomas is feasible and safe: Experience at a single Italian center. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, e172–e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saravana-Bawan, B.; Bajwa, A.; Paterson, J.; McMullen, T. Active surveillance of low-risk papillary thyroid cancer: A meta-analysis. Surgery 2020, 167, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russ, G.; Bonnema, Steen J. ; Erdogan, Murat F.; Durante, C.; Ngu, R.; Leenhardt, L. European thyroid association guidelines for ultrasound malignancy risk stratification of thyroid nodules in adults: The EU-TIRADS. Eur. Thyroid J. 2017, 6, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caulley, L.; Johnson-Obaseki, S.; Luo, L.; Javidnia, H. Risk factors for postoperative complications in total thyroidectomy. Medicine 2017, 96, e5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, N.; Mathonnet, M. Complications after total thyroidectomy. J. Visc. Surg. 2013, 150, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chahardahmasumi, E.; Salehidoost, R.; Amini, M.; Aminorroaya, A.; Rezvanian, H.; Kachooei, A.; Iraj, B.; Nazem, M.; Kolahdoozan, M. Assessment of the early and late complication after thyroidectomy. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2019, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuya-Kanamori, L.; Bell, K.J.L.; Clark, J.; Glasziou, P.; Doi, S.A.R. Prevalence of differentiated thyroid cancer in autopsy studies over six decades: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 3672–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugen, N.; Sloot, Y.J.E.; Netea-Maier, R.T.; van de Water, C.; Smit, J.W.A.; Nagtegaal, I.D.; van Engen-van Grunsven, I.C.H. Divergent metastatic patterns between subtypes of thyroid carcinoma results from the nationwide dutch pathology registry. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, e299–e306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Miyauchi, A.; Oda, H. Low-risk papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid: A review of active surveillance trials. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 44, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, R.M.; Fagin, J.A.; Minkowitz, G.; Wong, R.J.; Roman, B.; Patel, S.; Untch, B.; Ganly, I.; Shaha, A.R.; Shah, J.P.; et al. Natural history and tumor volume kinetics of papillary thyroid cancers during active surveillance. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017, 143, 1015–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, T. Fetal cell carcinogenesis of the thyroid: A modified theory based on recent evidence. Endocr. J. 2014, 61, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerashchenko, T.S.; Denisov, E.V.; Litviakov, N.V.; Zavyalova, M.V.; Vtorushin, S.V.; Tsyganov, M.M.; Perelmuter, V.M.; Cherdyntseva, N.V. Intratumor heterogeneity: Nature and biological significance. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2013, 78, 1201–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsutake, N.; Iwao, A.; Nagai, K.; Namba, H.; Ohtsuru, A.; Saenko, V.; Yamashita, S. Characterization of side population in thyroid cancer cell lines: Cancer stem-like cells are enriched partly but not exclusively. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 1797–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugolini, C.; Basolo, F.; Proietti, A.; Vitti, P.; Elisei, R.; Miccoli, P.; Toniolo, A. Lymphocyte and immature dendritic cell infiltrates in differentiated, poorly differentiated, and undifferentiated thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid 2007, 17, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryder, M.; Ghossein, R.A.; Ricarte-Filho, J.C.M.; Knauf, J.A.; Fagin, J.A. Increased density of tumor-associated macrophages is associated with decreased survival in advanced thyroid cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2008, 15, 1069–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Matsuzuka, F.; Yoshida, H.; Morita, S.; Nakano, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Yokozawa, T.; Hirai, K.; Kakudo, K.; Kuma, K.; et al. Encapsulated anaplastic thyroid carcinoma without invasive phenotype with favorable prognosis: Report of a case. Surg. Today 2003, 33, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibelius, G.; Mehra, S.; Clain, J.B.; Urken, M.L.; Wenig, B.M. Noninvasive anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: Report of a case and literature review. Thyroid 2014, 24, 1319–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.V.; Osamura, R.Y.; Kioppel, G.; Rosai, J. International Agency for Research on Cancer. WHO Classification of Tumours of Endocrine Organs; IARC Who Classification of Tumours: Lyon, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforov, Y.E.; Seethala, R.R.; Tallini, G.; Baloch, Z.W.; Basolo, F.; Thompson, L.D.; Barletta, J.A.; Wenig, B.M.; Al Ghuzlan, A.; Kakudo, K.; et al. Nomenclature revision for encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: A paradigm shift to reduce overtreatment of indolent tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canini, V.; Leni, D.; Pincelli, A.I.; Scardilli, M.; Garancini, M.; Villa, C.; Di Bella, C.; Capitoli, G.; Cimini, R.; Leone, B.E.; et al. Clinical-pathological issues in thyroid pathology: Study on the routine application of NIFTP diagnostic criteria. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallini, G.; Tuttle, R.M.; Ghossein, R.A. The history of the follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, Y.P.; Barletta, J.A. A user's guide to non-invasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP). Histopathology 2017, 72, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seethala, R.R.; Baloch, Z.W.; Barletta, J.A.; Khanafshar, E.; Mete, O.; Sadow, P.M.; LiVolsi, V.A.; Nikiforov, Y.E.; Tallini, G.; Thompson, L.D.R. Noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features: A review for pathologists. Mod. Pathol. 2018, 31, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Maso, L.D.; Vaccarella, S. Global trends in thyroid cancer incidence and the impact of overdiagnosis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pigac, B.; Masic, S.; Hutinec, Z.; Masic, V. Rare occurrence of incidental finding of noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features in hurthle cell adenoma. Med. Arch. 2018, 72, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gartland, R.M.; Lubitz, C.C. Reply to “impact of noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP) on the outcomes of lobectomy”. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 26, 307–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosario, P.W. Long-term outcomes of patients with noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP) ≥4 cm treated without radioactive iodine. Endocr. Pathol. 2017, 28, 367–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.D.R. Ninety-four cases of encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: A name change to Noninvasive Follicular Thyroid Neoplasm with Papillary-like Nuclear Features would help prevent overtreatment. Mod. Pathol. 2016, 29, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canberk, S.; Montezuma, D.; Taştekin, E.; Grangeia, D.; Demirhas, M.P.; Akbas, M.; Tokat, F.; Ince, U.; Soares, P.; Schmitt, F. “The other side of the coin”: Understanding noninvasive follicular tumor with papillary-like nuclear features in unifocal and multifocal settings. Hum. Pathol. 2019, 86, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LiVolsi, V.A. Papillary carcinoma tall cell variant (TCV): A review. Endocr. Pathol. 2010, 21, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akslen, L.A.; LiVolsi, V.A. Prognostic significance of histologic grading compared with subclassification of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer 2000, 88, 1902–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, Z.W.; Mandel, S.; LiVolsi, V.A. Combined tall cell carcinoma and hürthle cell carcinoma (collision tumor) of the thyroid. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2001, 125, 541–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaliszewski, K.; Diakowska, D.; Wojtczak, B.; Forkasiewicz, Z.; Pupka, D.; Nowak, Ł.; Rudnicki, J. Which papillary thyroid microcarcinoma should be treated as “true cancer” and which as “precancer”? World J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 17, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baloch, Z.; LiVolsi, V.A.; Tondon, R. Aggressive variants of follicular cell derived thyroid carcinoma; the so called ‘Real Thyroid Carcinomas’. J. Clin. Pathol. 2013, 66, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, Y.J.; Lee, J.S.; Park, S.Y.; Park, H.J.; Cho, B.Y.; Park, S.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Kang, K.-H.; Ryu, H.S. Histomorphological factors in the risk prediction of lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Histopathology 2013, 62, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, R.M.; Zhang, L.; Shaha, A. A clinical framework to facilitate selection of patients with differentiated thyroid cancer for active surveillance or less aggressive initial surgical management. Expert Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 13, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanocco, K.A.; Hershman, J.M.; Leung, A.M. Active surveillance of low-risk thyroid cancer. JAMA 2019, 321, 2020–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J.; Kim, S.G.; Tan, J.; Shen, X.; Viola, D.; Elisei, R.; Puxeddu, E.; Fugazzola, L.; Colombo, C.; Jarzab, B.; et al. BRAF V600E status may facilitate decision-making on active surveillance of low-risk papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 124, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, T.; Sugitani, I.; Ebina, A.; Fukuoka, O.; Toda, K.; Mitani, H.; Yamada, K. Active surveillance for T1bN0M0 papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid 2019, 29, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Total TC patients (n=678) |

PTC patients (n=579) |

Other types of TC (n=99) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) or mean + SD |

N (%) or mean + SD |

N (%) or mean + SD |

||

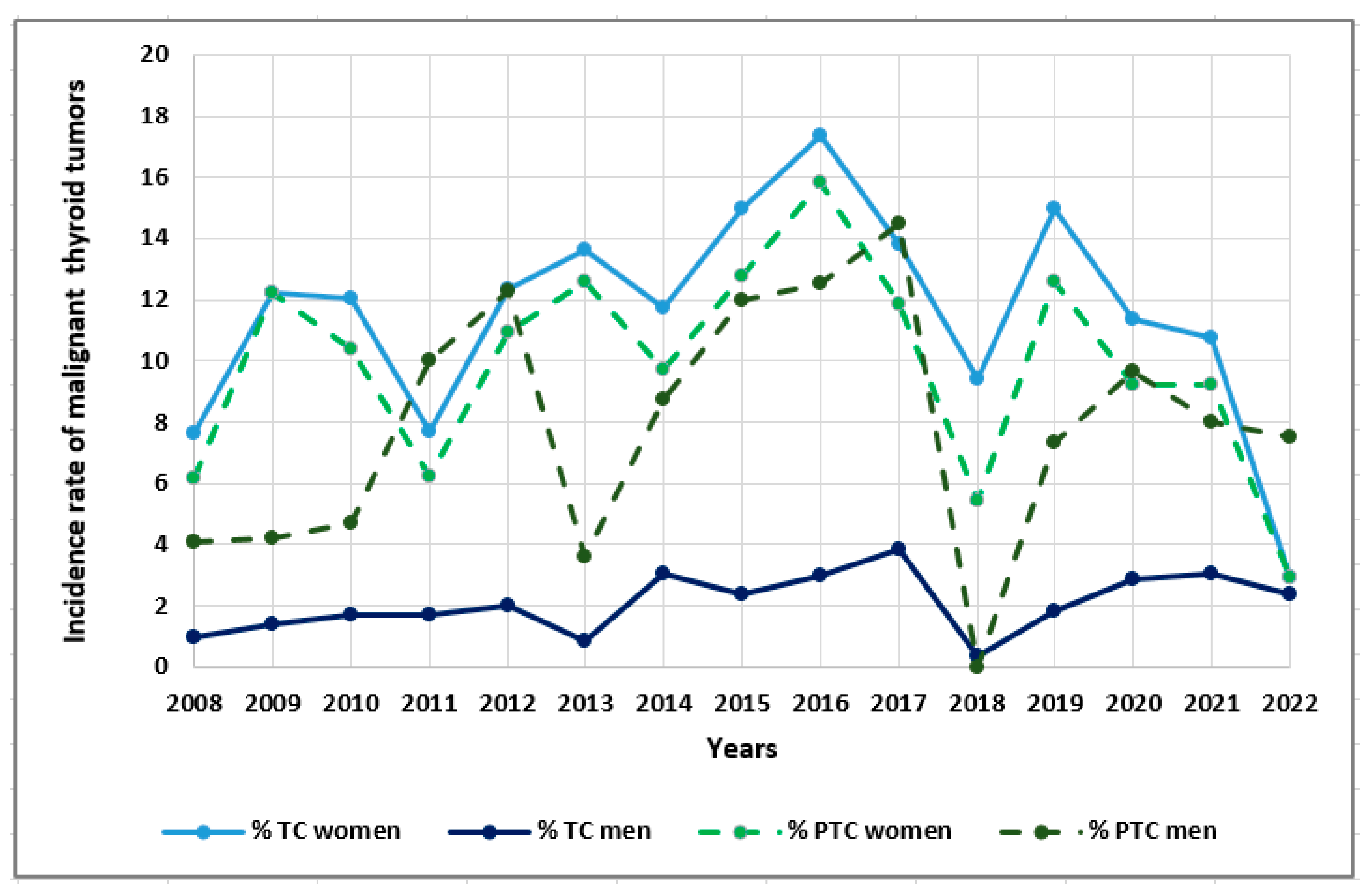

| Sex Female Male |

581 (85.69) 97 (14.30) |

501 (86.53) 78 (13.47) |

80 (80.81) 19 (19.19) |

0.133 |

| Age (years) |

51.66 + 15.98 | 50.25 + 15.20 | 59.92 + 17.95 | <0.0001* |

| Age: <55 years old >55 years old |

385 (56.78) 293 (43.21) |

355 (61.31) 224 (38.69) |

30 (30.30) 69 (69.70) |

<0.0001* |

| Type of surgery: Total No total |

474 (69.91) 204 (30.09) |

426 (73.58) 153 (26.42) |

48 (48.48) 51 (51.52) |

<0.0001* |

| Reoperation needed: No Yes |

503 (74.04) 176 (25.95) |

441 (76.17) 138 (23.83) |

61 (61.62) 38 (38.38) |

0.002* |

| Histological type of cancer: Papillary (PTC) Follicular (FTC) Medullary (MTC) Undifferentiated Sarcoma Secondary Lymphoma Squamous cell carcinoma Myeloma |

579 (85.39) 31 (4.57) 24 (3.53) 14 (2.06) 3 (0.44) 10 (1.47) 12 (1.76) 4 (0.58) 1 (0.14) |

579 (100.00) |

- 31 (31.31) 24 (24.24) 14 (14.14) 3 (3.03) 10 (10.10) 12 (12.12) 4 (4.04) 1 (1.01) |

- |

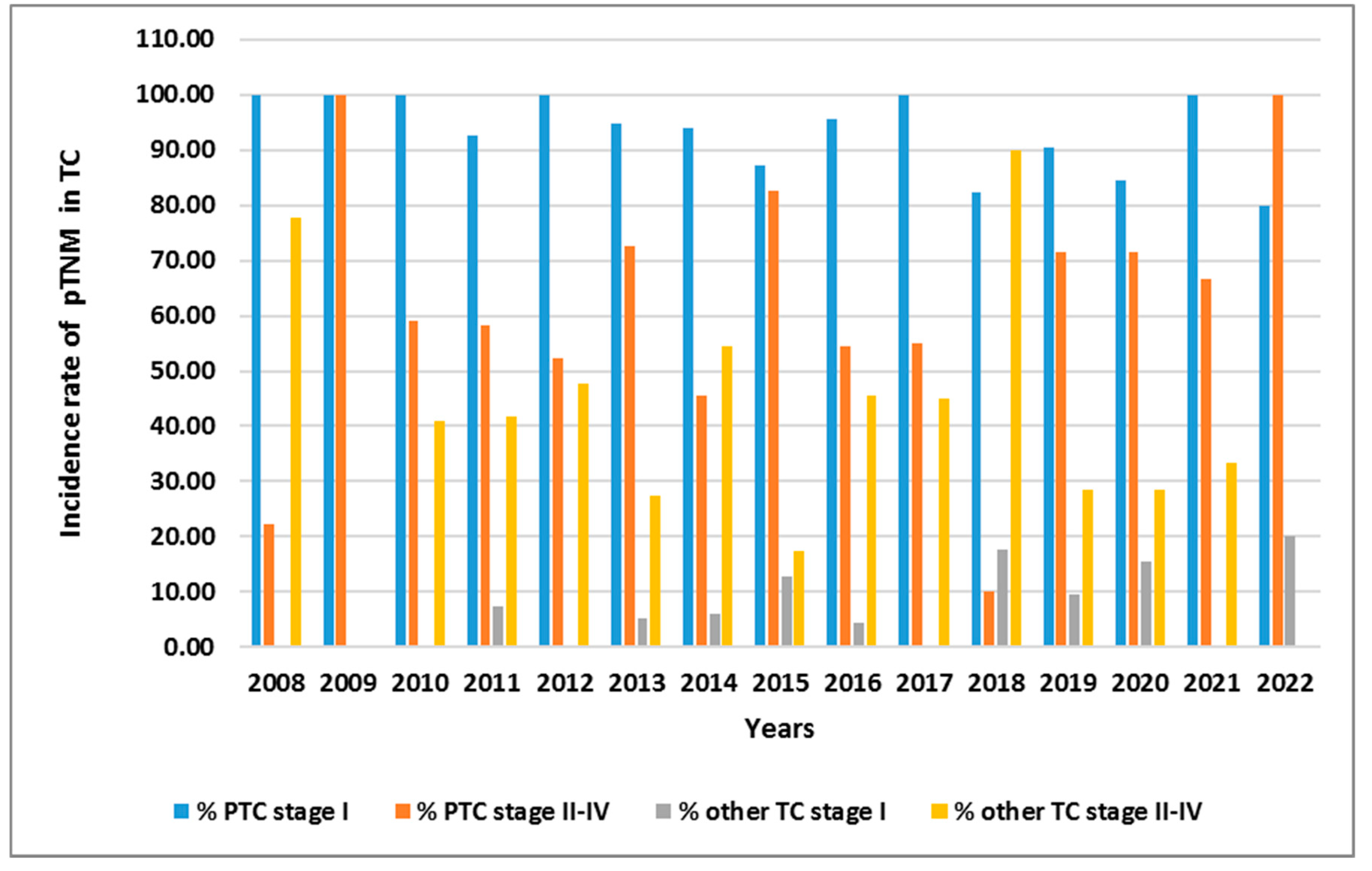

| pTNM: I II III IV |

501 (73.89) 90 (13.27) 42 (6.19) 45 (6.63) |

473 (81.69) 74 (12.78) 24 (4.15) 8 (1.38) |

27 (27.55) 16 (16.33) 18 (18.37) 37 (37.76) |

<0.0001* |

| pT: pT1a pT1b pT2 pT3 pT4a pT4b pTm |

256 (37.75) 276 (40.70) 78 (11.50) 24 (3.54) 16 (2.36) 26 (3.83) 2 (0.29) |

245 (42.76) 245 (42.76) 61 (10.65) 13 (2.27) 3 (0.52) 5 (0.87) 1 (0.17) |

9 (9.09) 29 (29.29) 15 (15.15) 11 (11.11) 13 (13.13) 21 (21.21) 1 (1.01) |

<0.0001* |

| pN: pN0 pN1a pN1b pNx |

427 (62.97) 184 (27.14) 35 (5.16) 32 (4.72) |

386 (66.67) 158 (27.29) 13 (2.25) 22 (3.80) |

41 (41.41) 26 (26.26) 22 (22.22) 10 (10.10) |

<0.0001* |

| pM: pM0 pM1 pMx |

568 (83.78) 46 (6.78) 64 (9.43) |

506 (87.39) 20 (3.45) 53 (9.15) |

61 (62.24) 26 (26.53) 11 (11.22) |

<0.0001* |

| Parameters | Total TC patients (n=678) |

PTC patients (n=579) |

Other types of TC (n=99) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

||

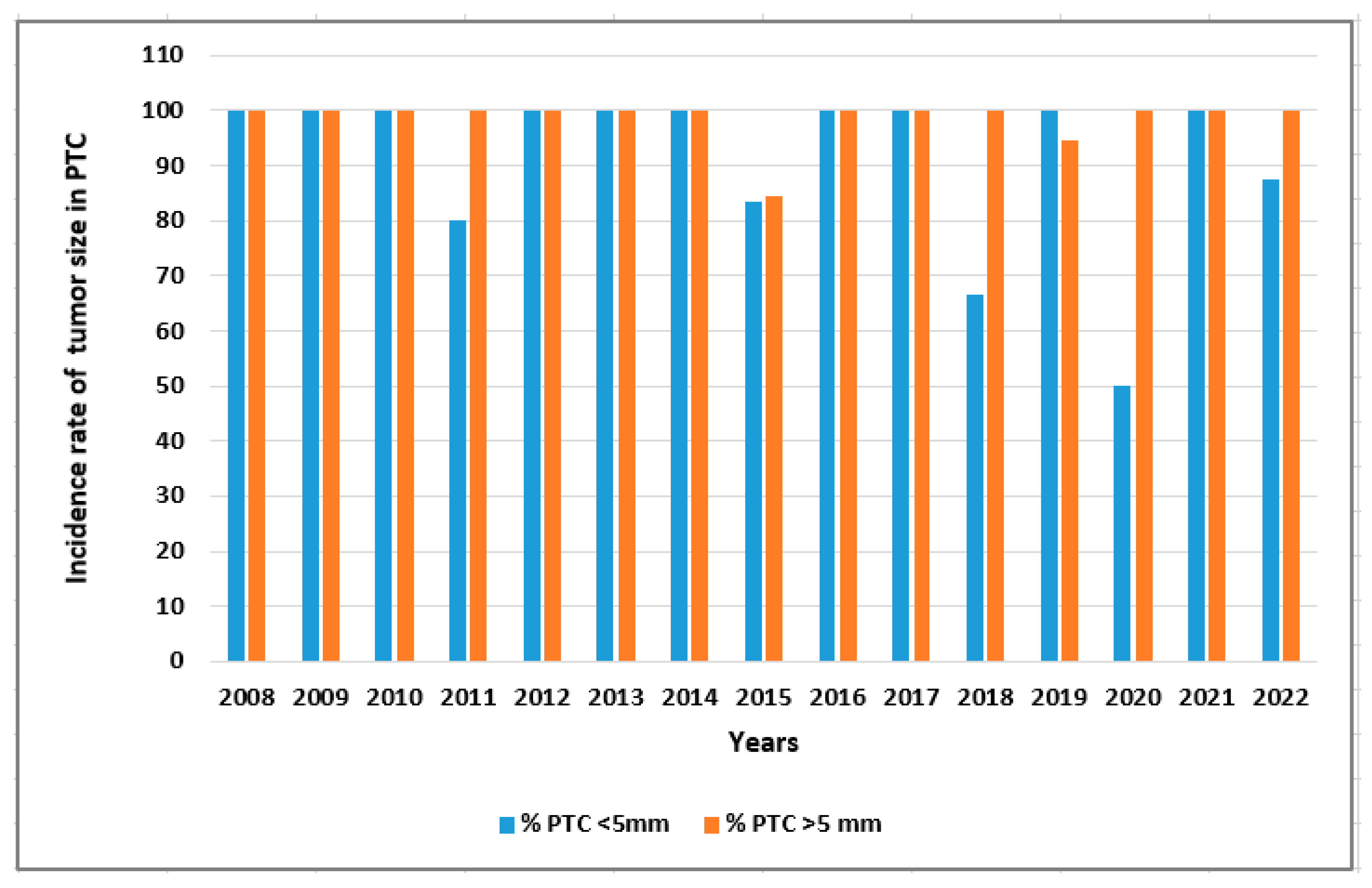

| Tumor size: <5 mm >5 mm |

294 (43.36) 384 (56.64) |

225 (38.89) 354 (61.11) |

69 (70.00) 30 (30.00) |

0.049* |

| Tumor shape: Regular Irregular |

294 (43.36) 384 (56.61) |

284 (49.13) 295 (50.87) |

10 (10.20) 89 (89.80) |

<0.0001* |

| Echogenicity: Hyperechoic Hypoechoic |

120 (17.69) 557 (82.15) |

116 (20.03) 463 (79.97) |

4 (4.08) 95 (95.92) |

0.0001* |

| Microcalcifications: No Yes |

275 (40.56) 403 (59.43) |

259 (44.73) 320 (55.27) |

16 (16.16) 83 (83.84) |

<0.0001* |

| Vascularity: Low High |

307 (45.28) 371 (54.71) |

295 (51.04) 283 (48.96) |

12 (12.24) 87 (87.76) |

<0.0001* |

| Type of tumor: Solitary Multifocal |

488 (71.96) 190 (28.02) |

423 (73.01) 156 (26.99) |

65 (65.66) 34 (34.34) |

0.132 |

| Bilateral: No Yes |

626 (92.32) 52 (7.67) |

529 (91.52) 49 (8.48) |

96 (96.97) 3 (3.03) |

0.060 |

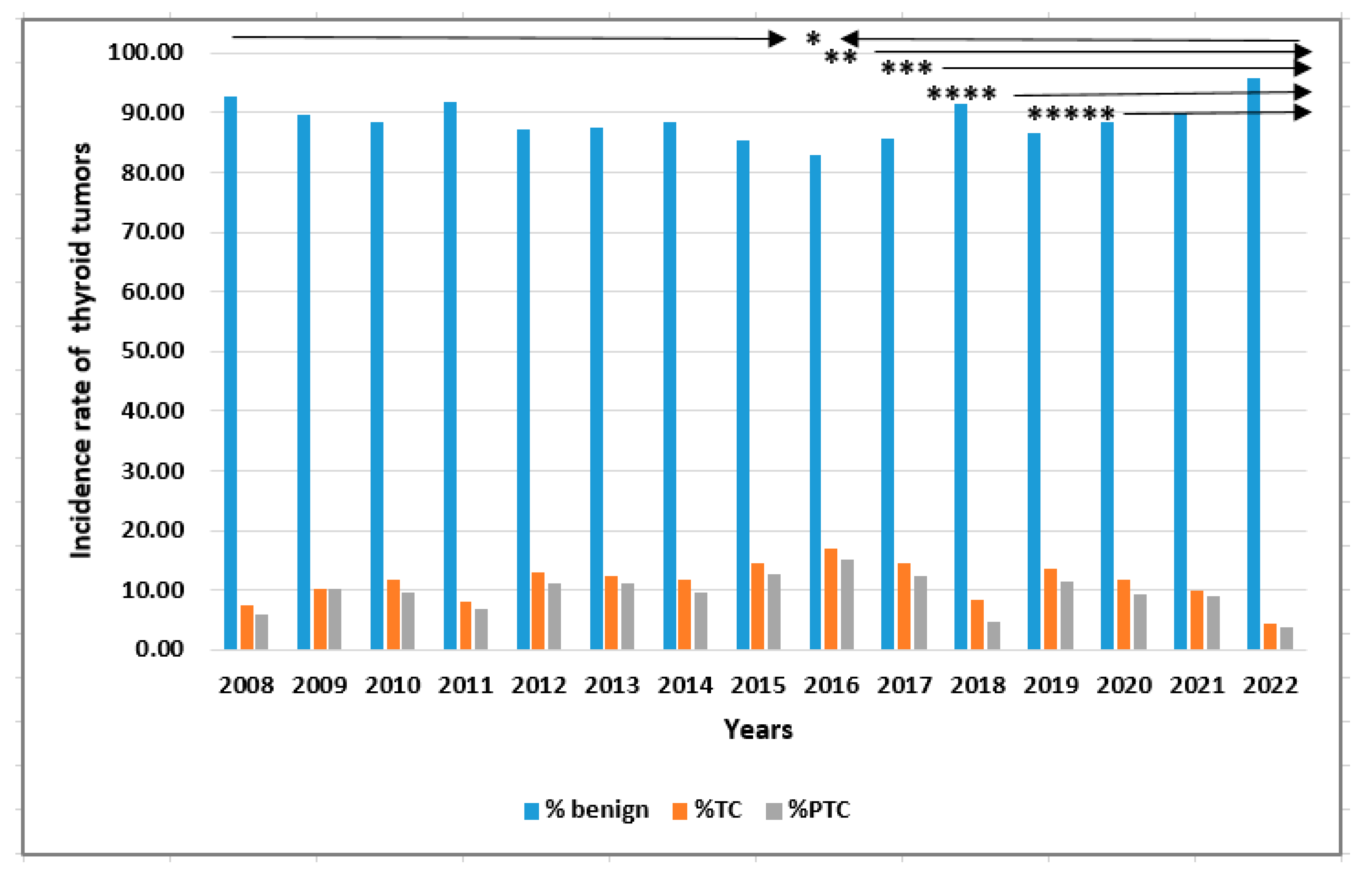

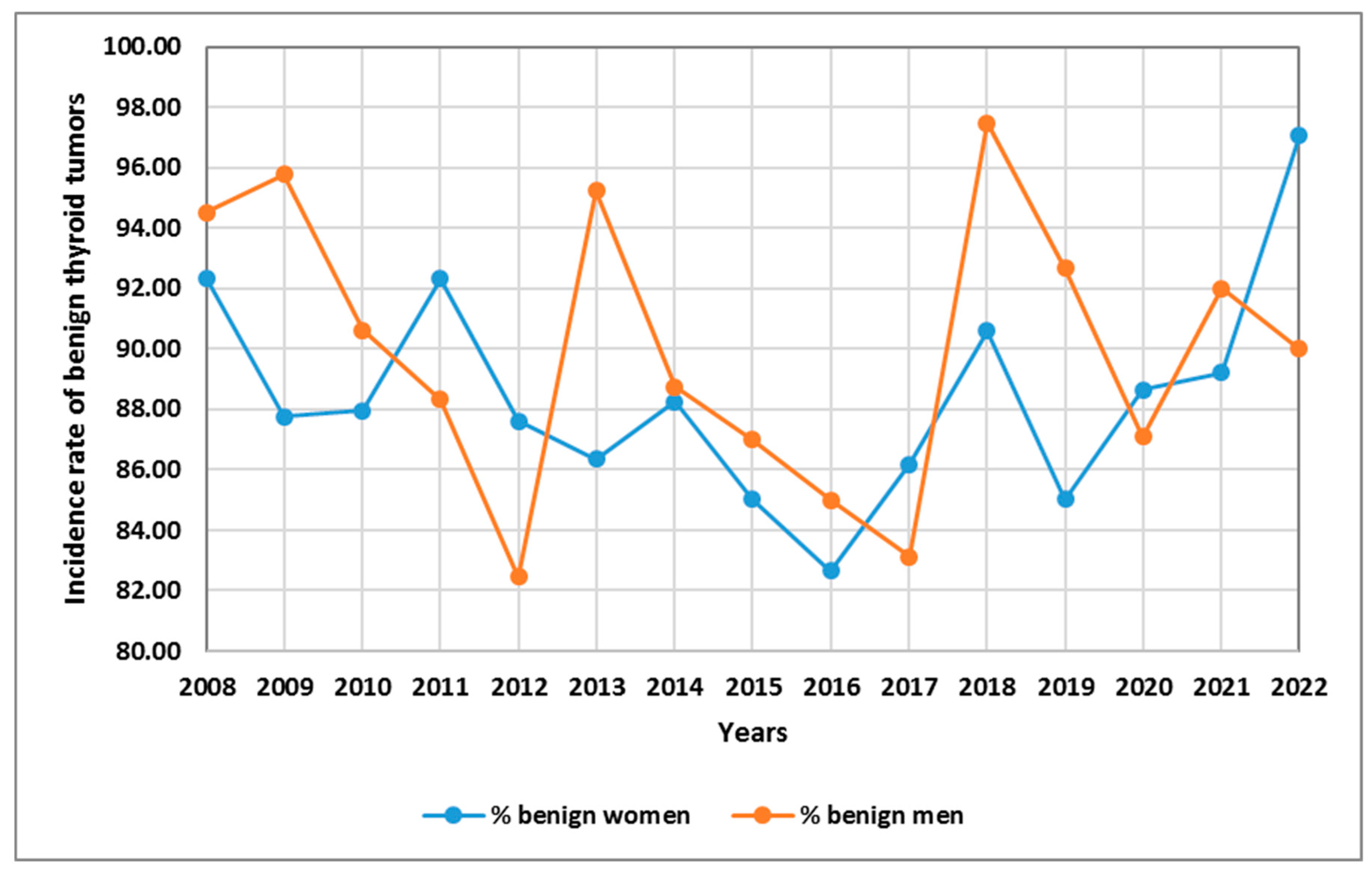

| Year | Benign tumors | Thyroid cancers | All patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 443 (8.64) | 35 (5.15) | 478 (8.23) |

| 2009 | 342 (6.67) | 39 (5.74) | 381 (6.56) |

| 2010 | 372 (7.26) | 49 (7.22) | 421 (7.25) |

| 2011 | 438 (8.54) | 39 (5.74) | 477 (8.22) |

| 2012 | 479 (9.34) | 71 (10.46) | 549 (9.46) |

| 2013 | 491 (9.58) | 69 (10.16) | 560 (9.65) |

| 2014 | 334 (6.50) | 44 (6.63) | 378 (6.51) |

| 2015 | 547 (10.67) | 94 (13.84) | 641 (11.04) |

| 2016 | 397 (7.74) | 81 (11.93) | 478 (8.23) |

| 2017 | 381 (7.43) | 64 (9.43) | 445 (7.67) |

| 2018 | 290 (5.66) | 27 (3.98) | 317 (5.46) |

| 2019 | 180 (3.51) | 28 (4.12) | 208 (3.58) |

| 2020 | 152 (2.96) | 20 (2.95) | 172 (2.96) |

| 2021 | 81 (1.58) | 9 (1.33) | 90 (1.55) |

| 2022 | 201 (3.92) | 9 (1.33) | 210 (3.62) |

| N (%) for groups | 5128 (100.00) | 678 (100.00) | 5806 (100.00) |

| N (%) for total | 5128 (88.32) | 678 (11.68) | 5806 (100.00) |

| Year | PTC | FTC | MTC | Undifferentiated | Sarcoma | Secondary TC | Lymphoma | SCC | Myeloma | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 28 (4.84) | 1 (3.23) | 1 (4.17) | 1 (7.14) | 1 (33.33) | 1 (10.00) | 2 (16.67) | - | - | 35 (5.16) |

| 2009 | 39 (6.74 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 39 (5.75) |

| 2010 | 40 (6.91) | 2 (6.45) | 2 (8.33) | 4 (28.57) | - | - | 1 (8.33) | - | - | 49 (7.23) |

| 2011 | 32 (5.53) | 3 (9.68) | 2 (8.33) | 1 (7.14) | - | 1 (10.00) | - | - | - | 39 (5.75) |

| 2012 | 61 (10.54) | 4 (12.90) | 1 (4.17) | 1 (7.14) | 1 (33.33) | 2 (20.00) | 1 (8.33) | - | - | 71 (10.47) |

| 2013 | 63 (10.88) | 3 (9.68) | - | 1 (7.14) | - | 2 (20.00) | - | - | - | 69 (10.18) |

| 2014 | 36 (6.22) | 2 (6.45) | 2 (8.33) | - | 1 (33.33) | 1 (10.00) | 2 (16.67) | - | - | 44 (6.49) |

| 2015 | 81 (13.99) | 5 (16.13) | 7 (29.17) | - | - | - | 1 (8.33) | - | - | 94 (13.86) |

| 2016 | 73 (12.61) | - | 3 (12.50) | 2 (14.29) | - | 3 (30.00) | - | - | - | 81 (11.95) |

| 2017 | 55 (9.50) | - | 1 (4.17) | 1 (7.14) | - | - | 3 (25.00) | 3 (75.00) | 1 (100.00) | 64 (9.44) |

| 2018 | 15 (2.59) | 6 (19.35) | 2 (8.33) | 2 (14.29) | - | - | 1 (8.33) | 1 (25.00) | - | 27 (3.98) |

| 2019 | 24 (4.15) | 1 (3.23) | 2 (8.33) | 1 (7.14) | - | - | - | - | - | 28 (4.13) |

| 2020 | 16 (2.76) | 4 (12.90) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20 (2.95) |

| 2021 | 8 (1.38) | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (8.33) | - | - | 9 (1.33) |

| 2022 | 8 (1.38) | - | 1 (4.17) | - | - | - | 0 (0.00) | - | - | 9 (1.33) |

| N (%) for subgroups | 579 (100.00) | 31(100.00) | 24(100.00) | 14(100.00) | 3(100.00) | 10(100.00) | 12(100.00) | 4(100.00) | 1(100.00) | 678 (100.00) |

| N (%) for total | 579 (85.40) | 31(4.57) | 24(3.54) | 14(2.06) | 3(0.44) | 10(1.47) | 12(1.77) | 4(0.59) | 1(0.15) | 678 (100.00) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).