Submitted:

18 September 2023

Posted:

20 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Governing Equations

2.1.1. Reynolds Averaging

2.1.2. Reynolds Averaging

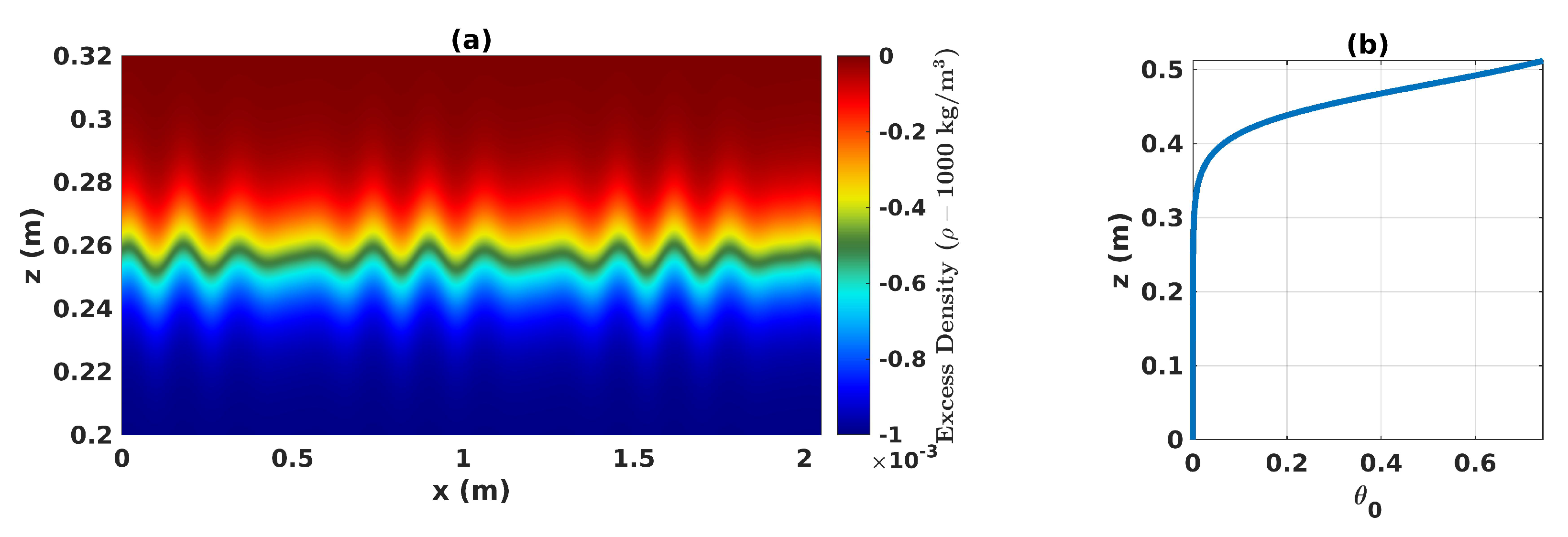

2.2. Numerical Simulation Ensemble Setup

3. Results

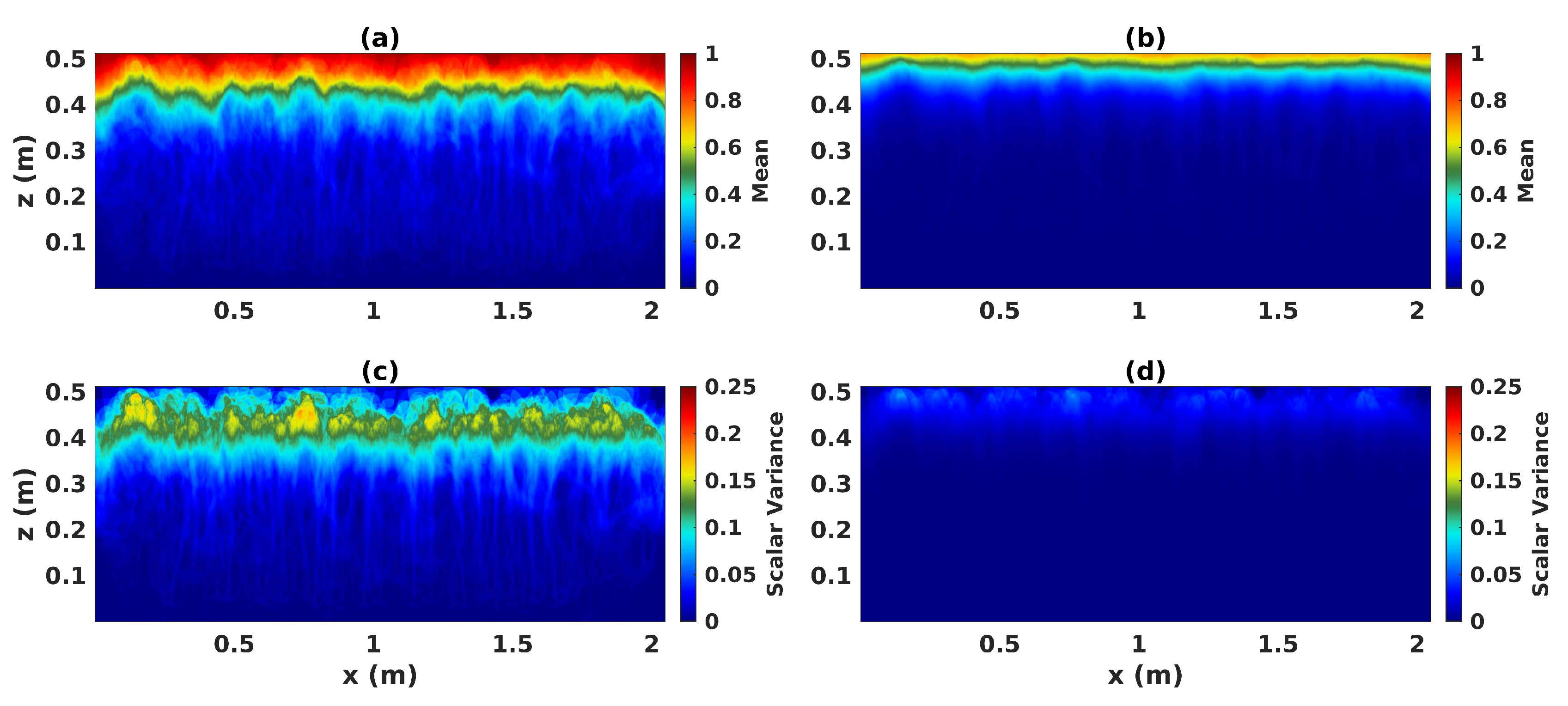

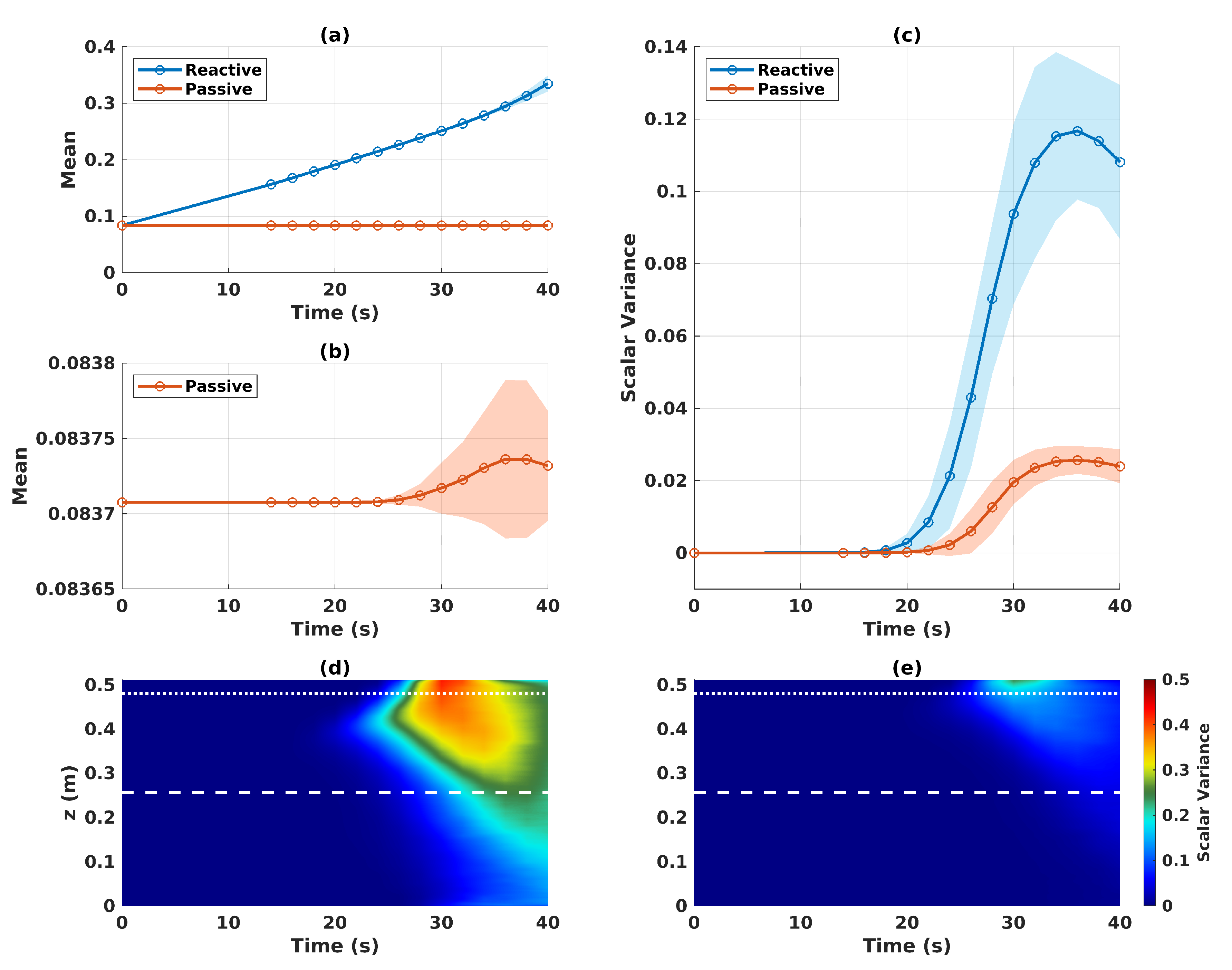

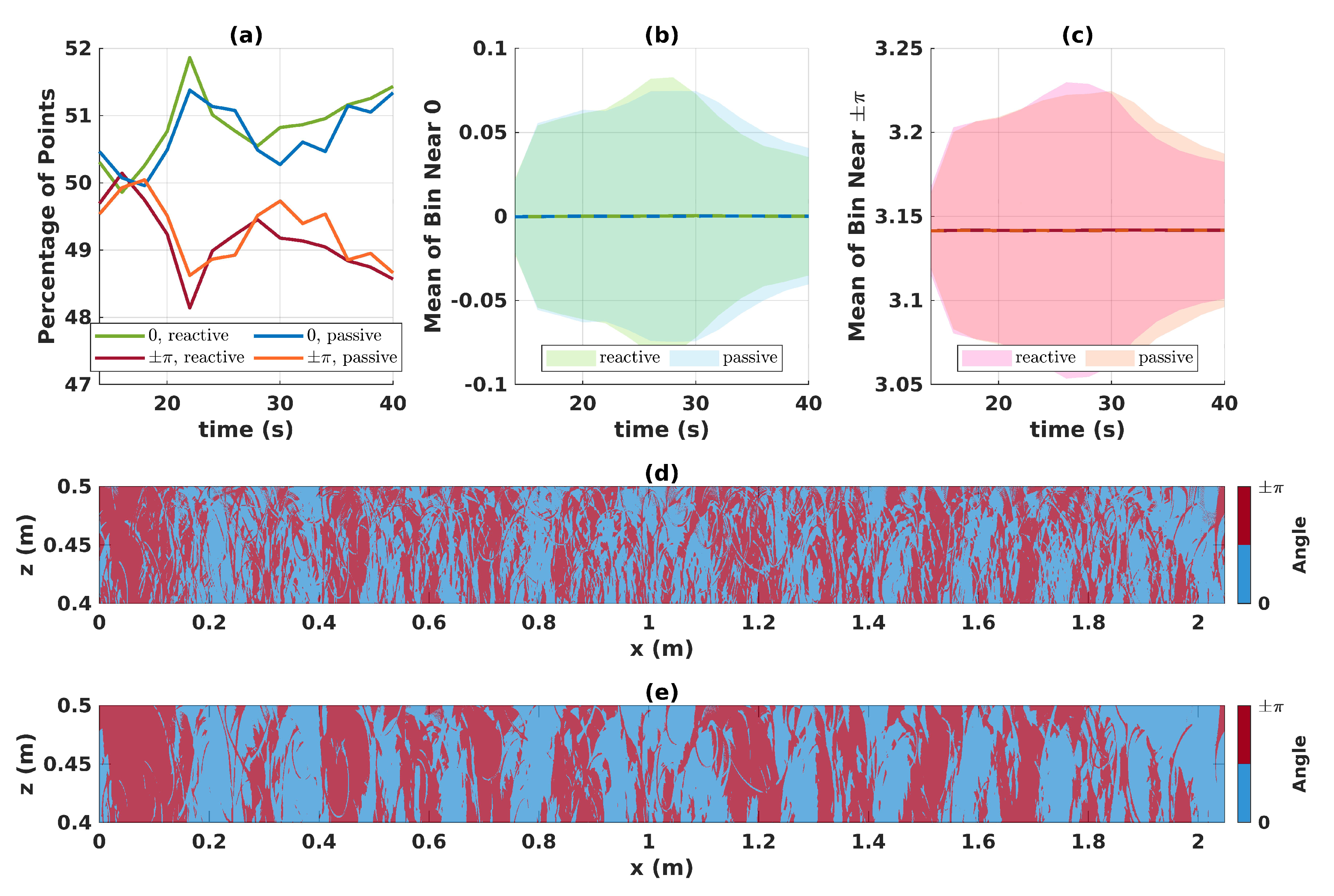

3.1. Tracer Mean and Scalar Variance

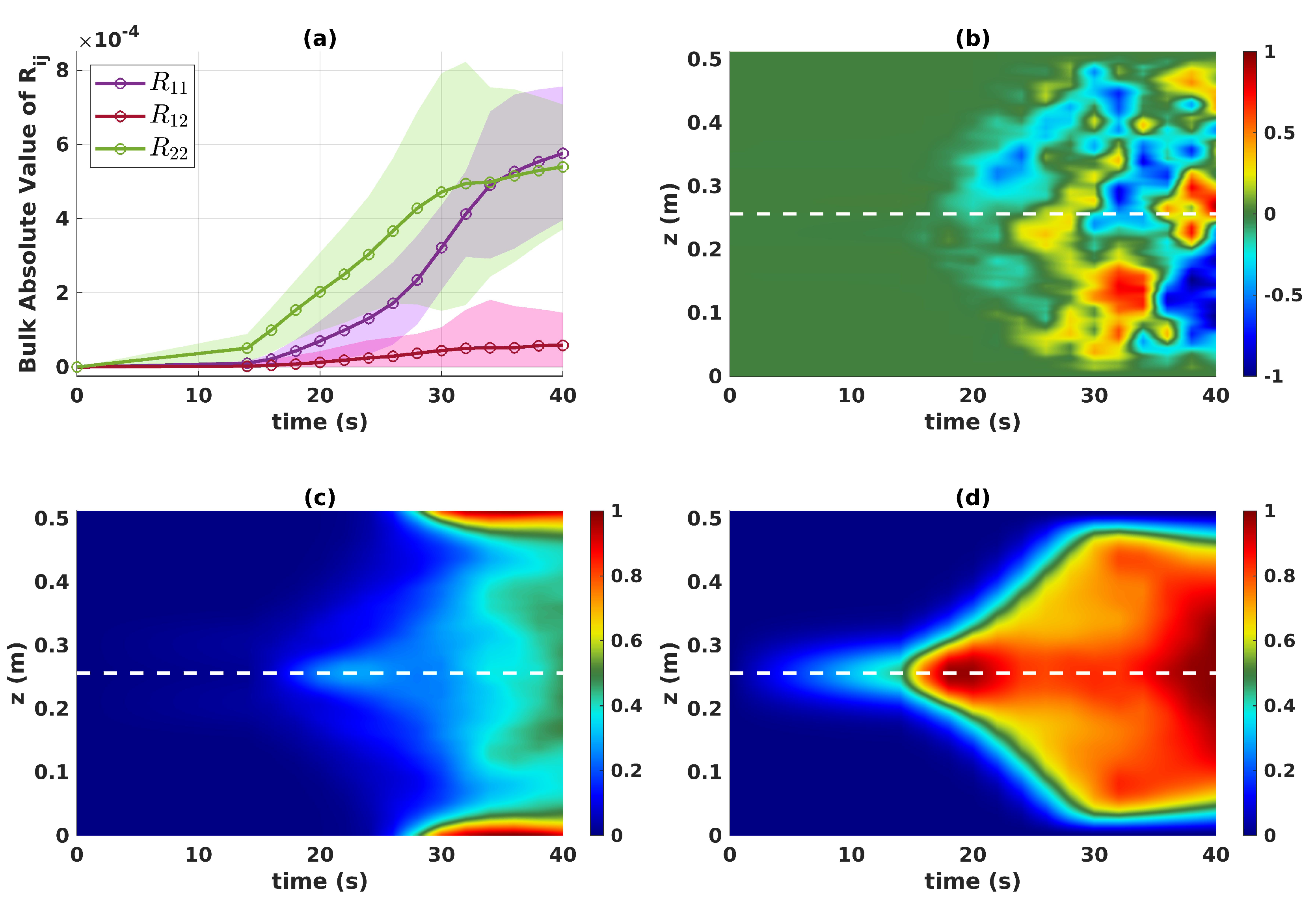

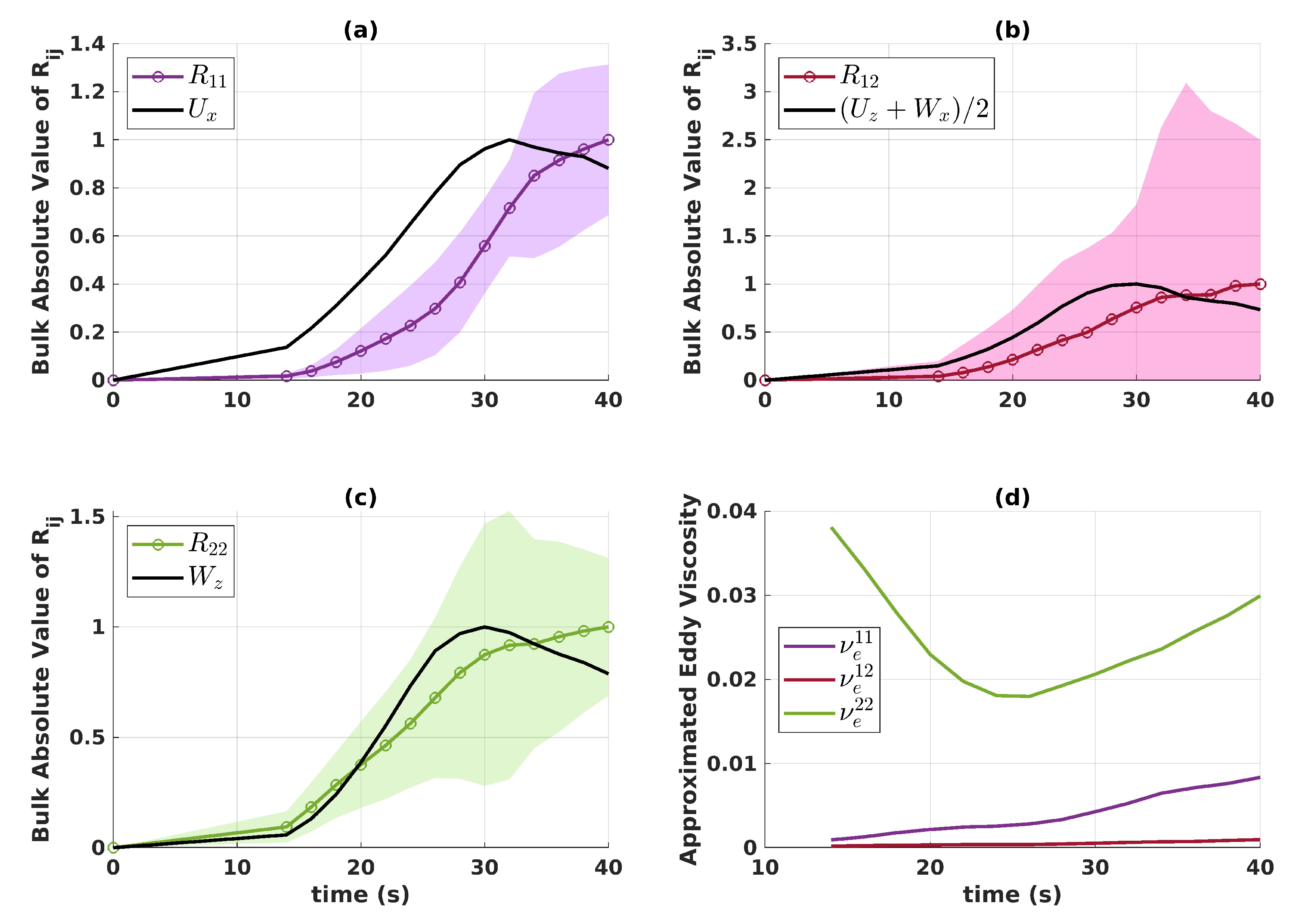

3.2. Reynolds Stresses

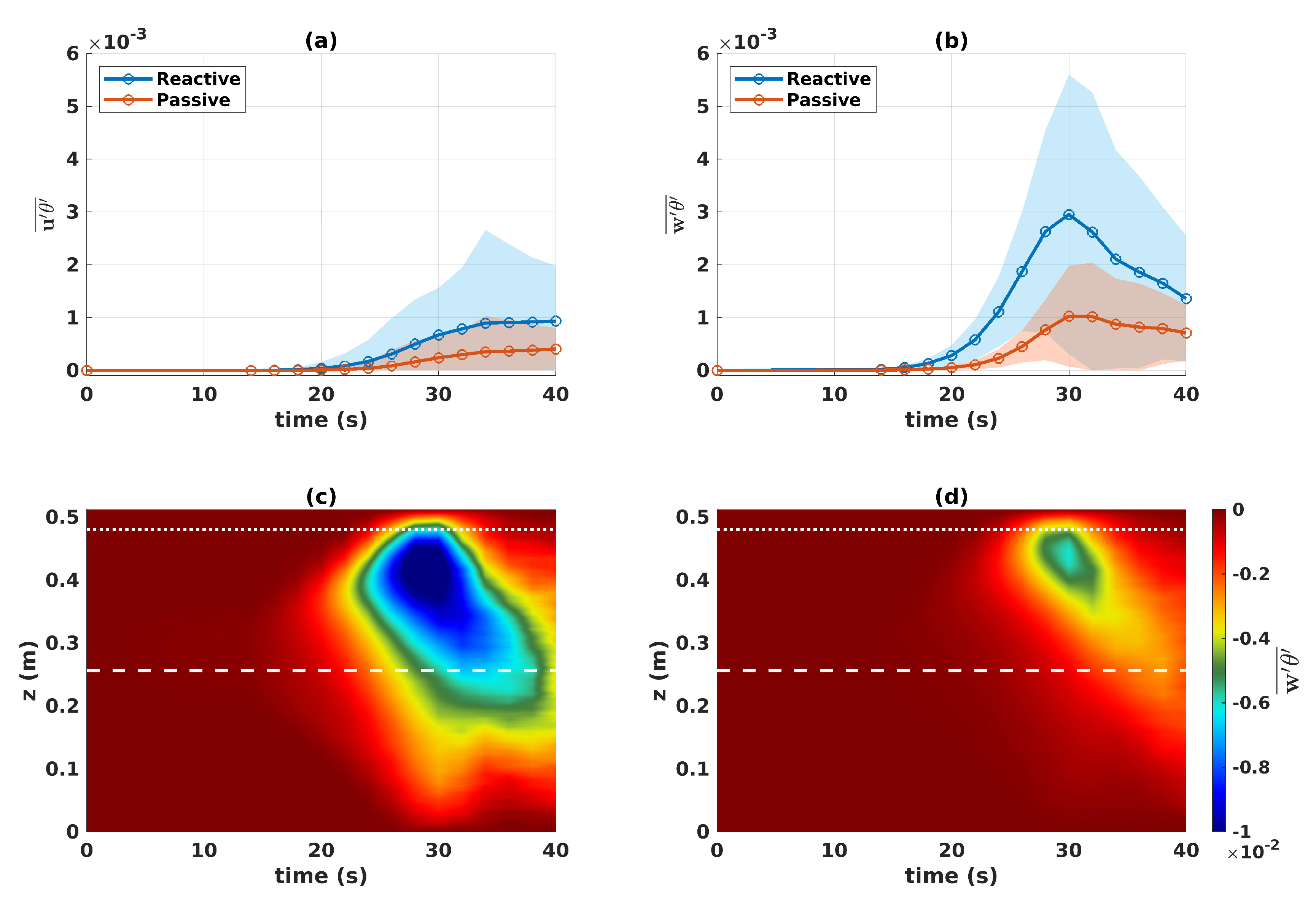

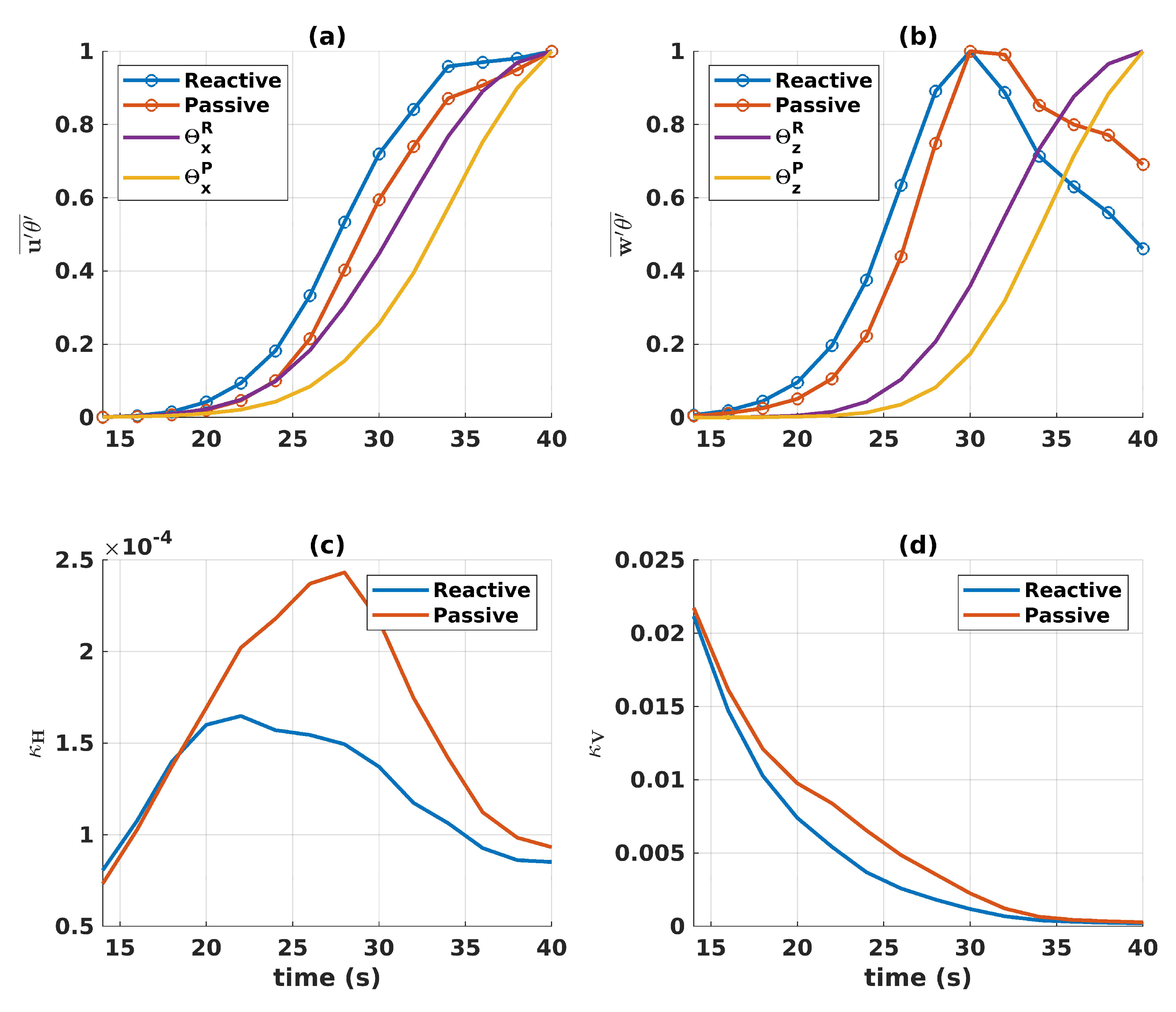

3.3. Eddy Fluxes

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADR | Advection-reaction-diffusion |

| RANS | Reynolds-averaged Navier Stokes |

| RT | Rayleigh-Taylor |

References

- Triantafyllou, G.; Yao, F.; Petihakis, G.; Tsiaras, K.; Raitsos, D.; Hoteit, I. Exploring the Red Sea seasonal ecosystem functioning using a three-dimensional biophysical model. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2014, 119, 1791–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KAMYKowski, D. A preliminary biophysical model of the relationship between temperature and plant nutrients in the upper ocean. Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers 1987, 34, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resplandy, L.; Lévy, M.; McGillicuddy Jr, D.J. Effects of eddy-driven subduction on ocean biological carbon pump. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 2019, 33, 1071–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, E.D.; Pirtle, J.L.; Duffy-Anderson, J.T.; Stockhausen, W.T.; Zimmermann, M.; Wilson, M.T.; Mordy, C.W. Eddy retention and seafloor terrain facilitate cross-shelf transport and delivery of fish larvae to suitable nursery habitats. Limnology and Oceanography 2020, 65, 2800–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baustian, M.M.; Meselhe, E.; Jung, H.; Sadid, K.; Duke-Sylvester, S.M.; Visser, J.M.; Allison, M.A.; Moss, L.C.; Ramatchandirane, C.; van Maren, D.S.; others. Development of an Integrated Biophysical Model to represent morphological and ecological processes in a changing deltaic and coastal ecosystem. Environmental Modelling & Software 2018, 109, 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, A.; Fennel, K.; Kuhn, A. An observation-based evaluation and ranking of historical Earth system model simulations in the northwest North Atlantic Ocean. Biogeosciences 2021, 18, 1803–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidvogel, D.B.; Arango, H.; Budgell, W.P.; Cornuelle, B.D.; Curchitser, E.; Di Lorenzo, E.; Fennel, K.; Geyer, W.R.; Hermann, A.J.; Lanerolle, L.; others. Ocean forecasting in terrain-following coordinates: Formulation and skill assessment of the Regional Ocean Modeling System. Journal of computational physics 2008, 227, 3595–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higdon, R.L.; Bennett, A.F. Stability analysis of operator splitting for large-scale ocean modeling. Journal of Computational Physics 1996, 123, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchepetkin, A.F.; McWilliams, J.C. The regional oceanic modeling system (ROMS): a split-explicit, free-surface, topography-following-coordinate oceanic model. Ocean modelling 2005, 9, 347–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ROMS Wiki Vertical Mixing Parameterizations. https://www.myroms.org/wiki/Vertical_Mixing_Parameterizations. Accessed: 2023-08-18.

- Burchard, H.; Rennau, H. Comparative quantification of physically and numerically induced mixing in ocean models. Ocean Modelling 2008, 20, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, C.E.; Bianucci, L.; Fennel, K. Sensitivity of northwest North Atlantic shelf circulation to surface and boundary forcing: A regional model assessment. Atmosphere-Ocean 2016, 54, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Li, J.; Hedstrom, K.; Babanin, A.V.; Holland, D.M.; Heil, P.; Tang, Y. Intercomparison of Arctic sea ice simulation in ROMS-CICE and ROMS-Budgell. Polar Science 2021, 29, 100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Sheng, J.; Tang, D.; Xing, J. Study of storm-induced changes in circulation and temperature over the northern South China Sea during Typhoon Linfa. Continental Shelf Research 2022, 249, 104866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, S.B. Turbulent flows; Cambridge university press, 2000.

- Dimotakis, P.E. Turbulent mixing. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2005, 37, 329–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, K.R. Turbulent mixing: A perspective. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 18175–18183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, P.K.; Cohen, I.M.; Dowling, D.R. Fluid mechanics; Academic press, 2015.

- Alfonsi, G. Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes equations for turbulence modeling 2009.

- Xiao, H.; Cinnella, P. Quantification of model uncertainty in RANS simulations: A review. Progress in Aerospace Sciences 2019, 108, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozorski, J.; Minier, J.P. Modeling scalar mixing process in turbulent flow. First Symposium on Turbulence and Shear Flow Phenomena. Begel House Inc., 1999.

- Abernathey, R.P.; Marshall, J. Global surface eddy diffusivities derived from satellite altimetry. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2013, 118, 901–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.T.; Wortham, C.; Kunze, E.; Owens, W.B. Eddy stirring and horizontal diffusivity from Argo float observations: Geographic and depth variability. Geophysical Research Letters 2015, 42, 3989–3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.; Shuckburgh, E.; Jones, H.; Hill, C. Estimates and implications of surface eddy diffusivity in the Southern Ocean derived from tracer transport. Journal of physical oceanography 2006, 36, 1806–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallée, J.; Speer, K.; Morrow, R.; Lumpkin, R. An estimate of Lagrangian eddy statistics and diffusion in the mixed layer of the Southern Ocean. Journal of Marine Research 2008, 66, 441–463.

- Ferrari, R.; Nikurashin, M. Suppression of eddy diffusivity across jets in the Southern Ocean. Journal of Physical Oceanography 2010, 40, 1501–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, G. Estimation of oceanic eddy transports from satellite altimetry. Nature 1986, 323, 243–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargett, A.E. Vertical eddy diffusivity in the ocean interior. Journal of Marine Research 1984, 42, 359–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenkovich, I.; Berloff, P.; Haigh, M.; Sun, L.; Lu, Y. Complexity of mesoscale eddy diffusivity in the ocean. Geophysical Research Letters 2021, 48, e2020GL091719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.M.; Hamlington, P.E.; Fox-Kemper, B. Effects of submesoscale turbulence on ocean tracers. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2016, 121, 908–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radko, T. Double-diffusive convection; Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Bachman, S.D.; Fox-Kemper, B.; Bryan, F.O. A tracer-based inversion method for diagnosing eddy-induced diffusivity and advection. Ocean Modelling 2015, 86, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquero, C. Differential eddy diffusion of biogeochemical tracers. Geophysical research letters 2005, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tergolina, V.B.; Calzavarini, E.; Mompean, G.; Berti, S. Effects of large-scale advection and small-scale turbulent diffusion on vertical phytoplankton dynamics. Physical Review E 2021, 104, 065106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, K.J.; Brentnall, S.J. The impact of diffusion and stirring on the dynamics of interacting populations. Journal of theoretical biology 2006, 238, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lévy, M.; Martin, A.P. The influence of mesoscale and submesoscale heterogeneity on ocean biogeochemical reactions. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 2013, 27, 1139–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tejada-Martínez, A.E.; Zhang, Q. Developments in computational fluid dynamics-based modeling for disinfection technologies over the last two decades: A review. Environmental modelling & software 2014, 58, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tejada-Martínez, A.E.; Zhang, Q.; Lei, H. Evaluating hydraulic and disinfection efficiencies of a full-scale ozone contactor using a RANS-based modeling framework. Water Research 2014, 52, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeloudis, A.; Stoesser, T.; Gualtieri, C.; Falconer, R.; others. Effect of three-dimensional mixing conditions on water treatment reaction processes. Proceedings of the 36th IAHR World Congress. The Netherlands: The Hague, 2015.

- Weerasuriya, A.U.; Zhang, X.; Tse, K.T.; Liu, C.H.; Kwok, K.C. RANS simulation of near-field dispersion of reactive air pollutants. Building and Environment 2022, 207, 108553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubagnac-Karkar, D.; Michel, J.B.; Colin, O.; Vervisch-Kljakic, P.E.; Darabiha, N. Sectional soot model coupled to tabulated chemistry for Diesel RANS simulations. Combustion and Flame 2015, 162, 3081–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltram Tergolina, V.; Calzavarini, E.; Mompean, G.; Berti, S. Surface light modulation by sea ice and phytoplankton survival in a convective flow model. arXiv e-prints 2022, pp. arXiv–2211.

- Kelley, D.E. Convection in ice-covered lakes: effects on algal suspension. Journal of Plankton Research 1997, 19, 1859–1880.

- Cabot, W. Comparison of two-and three-dimensional simulations of miscible Rayleigh-Taylor instability. Physics of Fluids 2006, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinakis, I.W.; Drikakis, D.; Youngs, D.L. Modeling of Rayleigh-Taylor mixing using single-fluid models. Physical Review E 2019, 99, 013104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarzhi, S.I. Review of theoretical modelling approaches of Rayleigh–Taylor instabilities and turbulent mixing. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2010, 368, 1809–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalziel, S.; Linden, P.; Youngs, D. Self-similarity and internal structure of turbulence induced by Rayleigh–Taylor instability. Journal of fluid Mechanics 1999, 399, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q. Temporal evolution and scaling of mixing in two-dimensional Rayleigh-Taylor turbulence. Physics of Fluids 2013, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subich, C.J.; Lamb, K.G.; Stastna, M. Simulation of the Navier–Stokes equations in three dimensions with a spectral collocation method. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids 2013, 73, 103–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracco, A.; Clayton, S.; Pasquero, C. Horizontal advection, diffusion, and plankton spectra at the sea surface. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2009, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyngaard, J.C. Turbulence in the Atmosphere; Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Trefethen, L.N. Spectral methods in MATLAB, volume 10 of Software, Environments, and Tools. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics (SIAM), Philadelphia, PA 2000, 24, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Harnanan, S.; Soontiens, N.; Stastna, M. Internal wave boundary layer interaction: A novel instability over broad topography. Physics of Fluids 2015, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepwell, D.; Stastna, M.; Carr, M.; Davies, P.A. Interaction of a mode-2 internal solitary wave with narrow isolated topography. Physics of Fluids 2017, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prend, C.J.; Flierl, G.R.; Smith, K.M.; Kaminski, A.K. Parameterizing eddy transport of biogeochemical tracers. Geophysical Research Letters 2021, 48, e2021GL094405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, J.E.; Palmer, M.R.; Poulton, A.J.; Hickman, A.E.; Sharples, J. Control of a phytoplankton bloom by wind-driven vertical mixing and light availability. Limnology and Oceanography 2021, 66, 1926–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, K.; Fennel, K.; Atamanchuk, D.; Wallace, D.; Thomas, H. A modelling study of temporal and spatial pCO 2 variability on the biologically active and temperature-dominated Scotian Shelf. Biogeosciences 2021, 18, 6271–6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Simulation Parameter | Value | Dimensionless Number | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.048m | |||

| 0.512m | |||

| 4096 | |||

| 1024 | |||

| g | 9.81 m/s | ||

| 1000kg/m | |||

| m/s | |||

| m/s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).