1. Introduction

Interrupted aortic arch (IAA) is a rare, severe form of congenital heart defect (CHD) characterized by complete anatomical discontinuity between two adjacent segments of the aortic arch [

1]. IAA occurs in about 1% of CHD and is classified as type A, B and C based on the anatomic location of the interruption in relation to the brachiocephalic vessels, being rarely diagnosed in fetal series [

2].

Although clinically under-recognized, 22q11.2DS is the most common microdeletion syndrome with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 4000 live births [

3,

4]. The first description in the English literature of the constellation of findings now known to be due to this chromosomal difference was made in the 1960s in children with DiGeorge syndrome, who presented with the clinical triad of immunodeficiency, hypoparathyroidism and congenital heart disease [

5]. The phenotypic spectrum of the 22q11.2DS includes a wide variety of malformations and abnormalities occurring in different combinations and with widely differing severity [

4].

In 20% of malformations of the outflow tract and IAA type B 22q11.2DS occurs and this association is significantly predicted by the presence of associated ultrasound findings: thymic hypo/aplasia, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and additional aortic arch anomalies [

6]. This shows that IAA type A and type B are distinct entities and while in IAA type B in more than 50% of cases 22q11.2DS may be expected, type A is not commonly associated with 22q11 hemizygosity [

7].

Screening options for 22q11.2DS include noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) and imaging. NIPT has a 70-83% detection rate and a 40-50% positive predictive value and prenatal imaging, usually by ultrasound, aims to detect several physical features associated with the syndrome [

8]. Definitive diagnosis is made by genetic testing of chorionic villi or amniocytes using a chromosomal microarray. About 85-90% of 22q11.2 microdeletions arise as de novo events and, in contrast to trisomies, are not related to parental age. The 22q11.2 region of the human genome facilitates the potential for non-allelic unequal homologous crossover (recombination) during meiosis, which can result in microdeletions [

8].

2. Case Report

We present the case of a 34-years old IGIP who obtained a spontaneous pregnancy while starting diagnostic work-up for infertility and was examined in our department for the second trimester anomaly scan. The first trimester anomaly scan was reported as normal and she had a low-risk NIPT result for trisomies 21, 18 and 13. Her medical and family history was uneventful. At 22 weeks the ultrasound differential diagnosis of CHD was made between severe aortic coarctation and tubular hypoplasia with VSD and IAA. A dilated pulmonary artery was also revealed. The fetal echocardiography performed by a pediatric cardiologist established the final diagnosis as IAA type B with VSD, pulmonary valve dysplasia and ARSA.

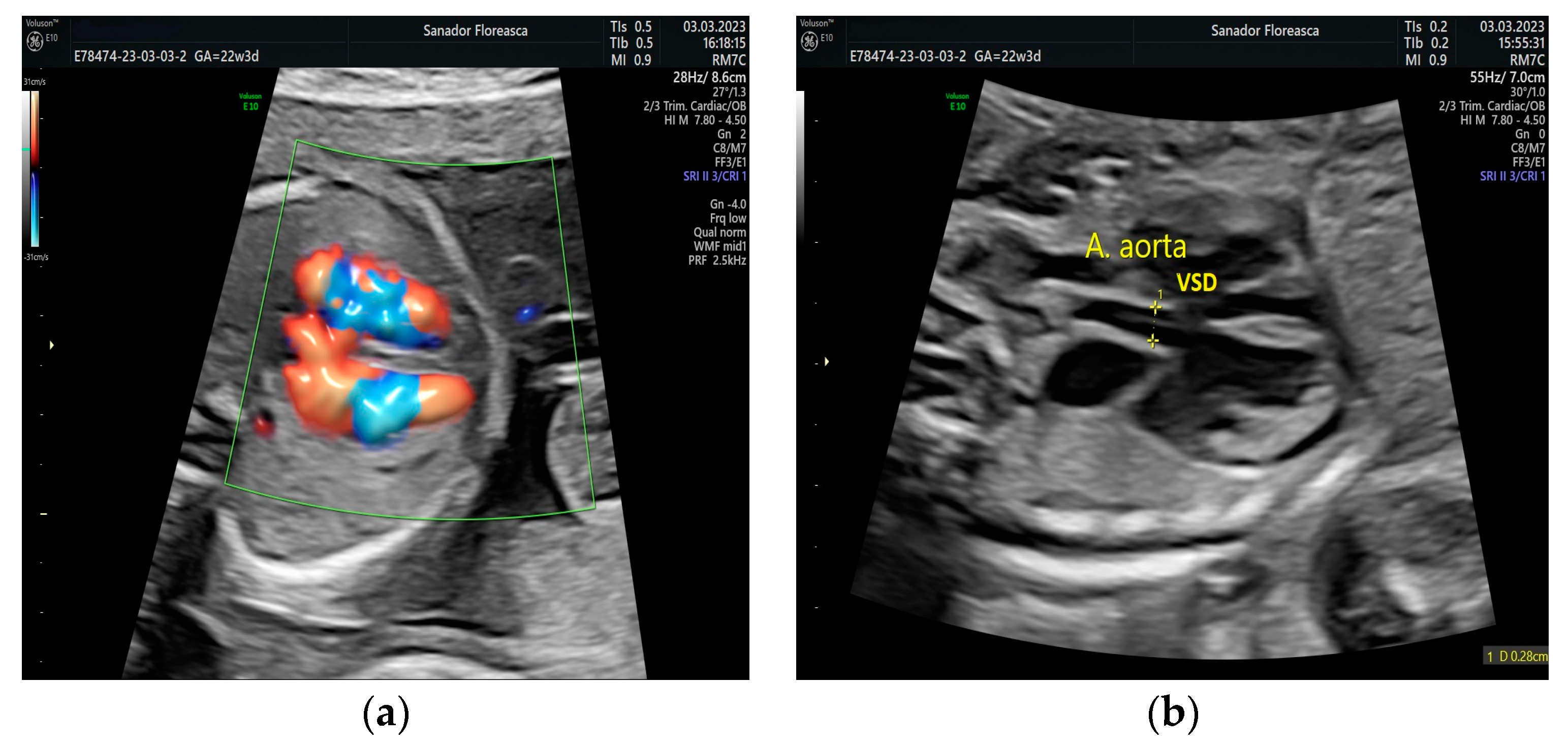

The four- chamber view showed a slightly ventricular disproportion with a narrow left ventricle when compared to the right ventricle, similar to findings in fetuses with aortic coarctation and the ventricular septal defect. The five-chamber view shows a VSD and a small descending aorta (

Figure 1).

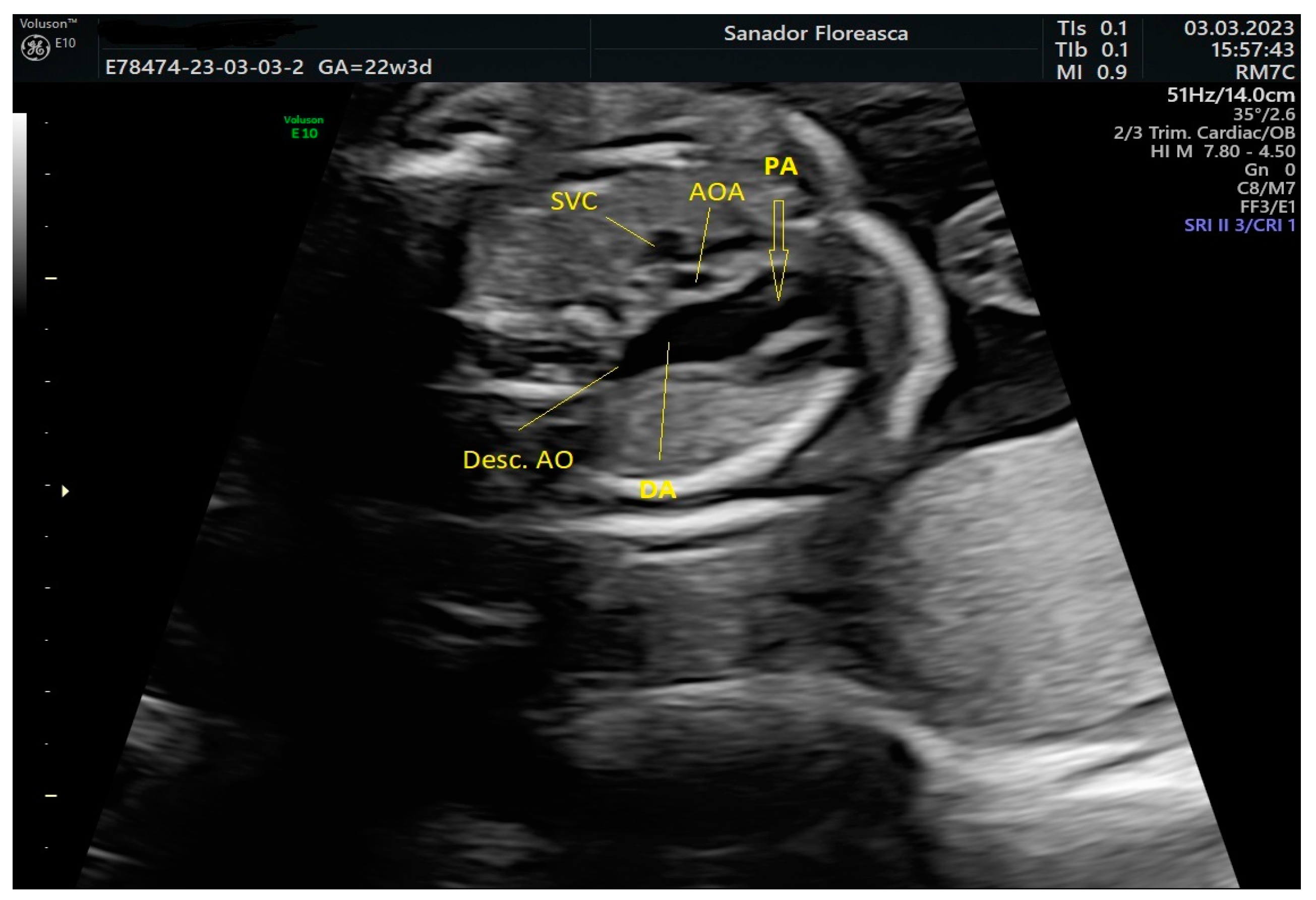

The three-vessel-trachea view revealed one of the main diagnostic features of IAA which is the lack of continuity of the aortic arch; moreover, the trachea appeared in close proximity with the pulmonary artery because of the absence of the medially located aortic arch and the pulmonary trunk was dilated (

Figure 2).

The thymus appeared to be at least hypoplastic and, in consequence, the pulmonary artery was noted to be in close proximity to the sternum anteriorly (

Figure 3). The thymic-to-thoracic ratio was 0.3.

Invasive genetic testing revealed 22q11.2 microdeletion and genetic counselling was offered to the patient who decided to continue the pregnancy. She had regular follow-ups with ultrasound scans every 2-3 weeks to monitor fetal growth and condition and amniotic fluid volume.

In the second half of gestation, we observed an enlarged cavum septum pellucidum (CSP) and polyhydramnios. Extracardiac findings included typical facial features, such as a bulbous nose (

Figure 4).

Although it is known that facial dysmorphism is typical in infants with this microdeletion, the prenatal ultrasound signs are not specific and can be subjective. The 3D reconstruction of fetal did not show any particular features throughout the gestation (

Figure 5).

The patient delivered vaginally at 40 weeks in a tertiary center with immediate availability of pediatric cardiology services. The female newborn weighed 3420 g and measured 48 cm. After 7 days the baby underwent complex cardiac surgery and biventricular circulation was maintained. She remained in the hospital under surveillance and the recovery was uneventful, so that after 2 weeks she was discharged.

At 7 weeks after birth the baby’s evolution is favorable and she is undergoing follow-up in a multidisciplinary team (pediatrician, pediatric cardiologist, genetics specialist, family physician).

3. Discussion

Despite widely available genetic testing for nearly 30 years, 22q11.2DS remains under-diagnosed, in part due to its multisystem nature and variable severity of associated features [5,8.9]. Although common, lack of recognition of the condition and/ or lack of familiarity with genetic testing options, together with the wide variability of clinical presentation, delays diagnosis. Early diagnosis, preferably established prenatally could improve outcome and prognosis, thus stressing the importance of universal screening.

Significant progress has been made in understanding the complex molecular genetic etiology of 22q11.2DS underpinning the heterogeneity of clinical manifestations. The deletion is caused by chromosomal rearrangements in meiosis and is mediated by non-allelic homologous recombination events between low copy repeats or segmental duplications in the 22q11.2 region. A range of genetic modifiers and environmental factors, as well as the impact of hemizygosity on the remaining allele contribute to the intricate genotype-phenotype relationships [

10].

For couples with no history of 22q11.2 microdeletion diagnosis in either parent, there are several possible routes to prenatal diagnostic testing that could identify a fetus with 22q11.2DS [

8]. Although the diagnosis of this microdeletion has been traditionally based on the recognition of clinical features and cytogenetic testing using the fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) technique, poor clinical accuracy, the low confirmatory rate in the screening of suspected microdeletions and failure to detect other than the targeted microdeletion are the major drawbacks of this method [

10]. So the golden standard method for detecting 22q11.2 microdeletions remains chromosomal microarray performed in invasively obtained prenatal samples, such as chorionic villi and amniotic fluid, as it was in our case.

A multicenter prospective observational study published recently evaluated the performance of single- nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)- based noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) for the 22q11.2 microdeletion in a large cohort of women. The results showed that noninvasive cell-free DNA prenatal screening can detect most affected cases, including smaller nested deletions, with a low false positive rate[

11]. Other studies revealed also that prenatal screening for 22q11.2 deletion has become clinically feasible[

12,

13].

The most frequent association is made between 22q11.2DS and congenital heart disease and cleft palate [

14]; moreover, cardiac anomalies reported include conotruncal anomalies such as interrupted aortic arch, common arterial trunk, absent pulmonary valve syndrome, pulmonary atresia with VSD, tetralogy of Fallot and conoventricular septal defects [

15,

16]. The presence of a right aortic arch, an aberrant right subclavian artery, especially in combination with a cardiac anomaly, a hypoplastic thymus or other extracardiac anomalies increases the risk for deletion of 22q11.2 [

17,

18].

We bring into discussion the case of a newborn with 22q11.2DS diagnosed prenatally with a complex cardiac anomaly who required postnatally major surgical repair in a tertiary center for pediatric cardiology. Our aim was to call attention to the paramount importance of a correct prenatal diagnosis which allows counselling of the patient, offering genetic testing and managing the case further in a multidisciplinary team.

In our case the final fetal cardiologic diagnosis was IAA type B with a large VSD, pulmonary valve dysplasia and ARSA. IAA is a rare form of critical neonatal heart disease and in the absence of prenatal diagnosis patients with IAA present in shock when the patent ductus arteriosus closes; thus, initiation of prostaglandin E1 infusion allows for adequate lower body perfusion prior to surgical repair [

19]. As a result of accurate prenatal diagnosis our patient was admitted to a tertiary pediatric cardiology unit where the surgical intervention was performed successfully.

It is rare for patients with isolated IAA to survive to adulthood without operation; still, cases of isolated IAA diagnosed using CT angiography have been reported in literature [

20,

21,

22,

23]. In a retrospective study published by Jiang et al. it was observed that in these cases the patients had extensive collateral vessels joining the descending aorta. Anti-hypertensive medical management with long-term follow-up appears to be a reasonable treatment option for these patients, although surgical intervention is a good choice [

20]. This is not applicable in our case report considering that the fetus was diagnosed with complex IAA and also a genetic syndrome, thus warranting immediate surgical correction.

The age of the newborn to undergo the operation was in our case 7 days, which is consistent to the study reported by Onalan et al. [

24]. Yet, 38% of their patients required reintervention due to aortic arch restenosis during the follow-up period. Preoperative aortic root size is a predictive factor for postoperative left ventricular outflow tract obstruction after single-stage repair of IAA with VSD [

25]; if we take into consideration the cut-off value of 6.5 mm for the aortic root size our patient falls into the high-risk group and will require a close follow-up in order to promptly identify progressive obstruction.

Furthermore, a case of middle cerebral artery aneurysm rupture occurring at 2 weeks after undergoing congenital heart anomaly repair in a neonate with IAA has been published [

26]. Also, another unusual complication following cardiac surgery for IAA was reported in an 8-year-old patient: giant aortic arch aneurysm [

27], pointing to the fact that an extended period of follow-up is essential.

As expected, our patient had an association between 22q11.2DS and IAA type B, whereas IAA type A is found rarely in combination with this genetic deletion [

28,

29,

30]; Paolo Volpe’s study confirms that IAA type B is usually syndromic (66.7% of the cases analyzed were associated with 22q11.2DS), this suggesting that IAA type A and type B could be two separate pathogenetic entities [

1]. One possible explanation might lie in the disparate embryological origin of the different segments composing the aortic arch.

5. Conclusions

22q11.2DS is quintessentially a multi-system syndrome with a remarkable variability in the severity and extent of expression in individuals, even in affected members of the same family [

3]. In consequence, treatment must be targeted to best suit the individual, age or developmental stage and the particular constellation of associated features, severity and need for treatment.

We presented in this paper an interesting case of prenatally diagnosed 22q11.2DS in a fetus with severe and complex cardiac anomalies and other syndromic ultrasound features (enlarged CSP, hypoplastic thymus, bulbous nose, polyhydramnios). We emphasize the importance of early diagnosis and increased awareness of prenatal extended screening which provides the best opportunity for affecting the course of the illness and optimizing outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Video S1: Characteristic appearance of IAA, VSD, dilated pulmonary artery, ARSA and severe thymus hypoplasia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.V and C.M; methodology, R.V., C.M., E.B.; investigation, C.M., ; resources, C.M., R.T., M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.; writing—review and editing, R.V., C.M., E.B.; visualization, C.M.; supervision, R.T., M.S.,E.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This paper was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of The Clinical Hospital of Obstetrics and Gynecology “Prof. Dr. Panait Sirbu“ (approval code 14/ 05.09.2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper .

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Volpe P, Tuo G, De Robertis V, et al. Fetal interrupted aortic arch: 2D- 4D echocardiography, associations and outcome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2010;35(3):302-9. [CrossRef]

- Riggs KW, Anderson RH, Spicer D, Morales DL. Coarctation and interrupted aortic arch. In: Wernovsky G, Anderson RH, Kumar K, Mussatto KA, Redington AN, Tweddell, eds. Anderson′s Pediatric Cardiology. Elsevier;2019:843-64.

- Bassett AS, McDonald-McGinn DM, Devriendt K, et al. Practical guidelines for managing patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. J Pediatr 2011;159(2):332-9.e1. [CrossRef]

- Oskarsdottir S, Vujic M, Fasth A. Incidence and prevalence of the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: a population-based study in Western Sweden. Arch Dis Child 2004;89(2):148-51. [CrossRef]

- McDonald-McGinn DM, Sullivan KE, Marino B, et al. 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015;1:15071. [CrossRef]

- Volpe P, Marasini M, Caruso G, et al. 22q11 deletions in fetuses with malformations of the outflow tracts or interruption of the aortic arch: impact of additional ultrasound signs. Prenat Diagn 2003;23(9):752-7. [CrossRef]

- Volpe P, Marasini M, Caruso G, Gentile M. Prenatal diagnosis of interruption of the aortic arch and its association with deletion of chromosome 22q11. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2002;20(4):327-31. [CrossRef]

- Blagowidow N, Nowakowska B, Schindewolf E, et al. Prenatal screening and diagnostic considerations for 22q11.2 microdeletions. Genes (Basel) 2023;14(1):160. [CrossRef]

- Palmer LD, Butcher NJ, Boot E, et al. Elucidating the Diagnostic Odyssey of 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2018;176:936-44. [CrossRef]

- Szczawinska-Poplonyk A, Schwartzmann E, Chmara Z, et al. Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: a comprehensive review of molecular genetics in the context of multidisciplinary clinical approach. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24(9):8317. [CrossRef]

- Dar P, Jacobsson B, Clifton R, et al. Cell-free DNA screening for prenatal detection of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022;227(1):79.e1-79.e11. [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua E, Jani C, Chaoui R, et al. Performance of a targeted cell-free DNA prenatal test for 22q11.2 deletion is a large clinical cohort. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2021;58(4):597-602. [CrossRef]

- Schmid M, Wang E, Bogard PE, et al. Prenatal screening for 22q11.2 deleletion using a targeted microarray-based cell-free DNA test. Fetal Diagn Ther 2018;44(4):299-304. [CrossRef]

- Schindewolf E, Khalek N, Johnson MP, et al. Expanding the fetal phenotype: prenatal sonographic findings and perinatal outcomes in a cohort of patients with confirmed 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2018;176(8):1735-41. [CrossRef]

- Karl H, Heling KS, Sarut Lopez A, et al. Thymic-thoracic ratio in fetuses with trisomy 21, 18 or 13. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2012;40:412-7. [CrossRef]

- Noel AC, Pelluard F, Delezoide AL, et al. Fetal phenotype associated with the 22q11 deletion. Am J Med Genet 2014;164:2724-31. [CrossRef]

- Rauch R, Rauch A, Koch A, et al. Laterality of the aortic arch and anomalies of the subclavian artery-reliable indicators for 22q11.2 deletion syndromes? Eur J Pediatr 2004;163:642-5. [CrossRef]

- Perolo A, De Robertis V, Cataneo I, et al. Risk of 22q11.2 deletion in fetuses with right aortic arch and without intracardiac anomalies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016;48:200-3. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, K. Preoperative physiology, imaging, and management of interrupted aortic arch. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2018;22(3):265-9. [CrossRef]

- Jian Y, Wang C, Jiang X, Chen Si. Is surgery necessary for adults with isolated interrupted aortic arch?: Case series with literature review. J Card Surg 2021;36(7):2467-75. [CrossRef]

- Gan Y, Zhang P, Liao R, Nie Y, Fu Y. Novel interrupted aortic arch: a case report. J Card Surg 2022;37(12);5639-42. [CrossRef]

- Jin X, Fan G, Zhang W, Liang H. Interrupted aortic arch in adulthood: a rare case report. Asian J Surg 2023;46(7):2976-7. [CrossRef]

- Chen GWn Li H, Pu H. Isolated interrupted of aortic arch diagnosed using CT angiography: a case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97(21):e10569. [CrossRef]

- Onalan MA, Temur B, Aydin S, et al. Management of interrupted aortic arch with associated anomalies: a single-center experience. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg 2021;12(6):706-14. [CrossRef]

- Chen PC, Cubberley A, Reyes K, et al. Predictors of reintervention after repair of interrupted aortic arch with ventricular septal defect. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;96(2):621-8. [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo J, Dickerson JC, Burnsed B, Luqman A, Shiflett JM. Middle cerebral artery aneurysm rupture in a neonate with interrupted aortic arch: case report. Childs Nerv Syst 2017;33(6):999-1003. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh A, Liu A, Mora B, Agarwala B. Giant aortic arch aneurysm after interrupted aortic arch repair. Pediatr Cardiol 2010;31(7):1104-6. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi K, Kuwahara T, Nagatsu M. Interruption of the aortic arch at the isthmus with DiGeorge syndrome and 22q11.2 deletion. Cardiol Young 1999;9:516-8. [CrossRef]

- Lewin MB, Lindsay EA, Jurecic V, Goytia B, Towbin J, Baldini A. A genetic aetiology for interruption of the aortic arch type B. Am J Cardiol 1997;80:493-7. [CrossRef]

- Rauch A, Hofbeck M, Leipold G, Klinge J, Trautmann U, Kirsch M, Singer H, Pfeiffer RA. Incidence and significance of 22q11.2 hemizygosity in patients with interrupted aortic arch. Am J Med Genet 1998;78:322-31.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).