1. Introduction:

A common musculoskeletal condition in adults, mechanical neck pain (MNP), is characterised by nonspecific discomfort at the cervicothoracic junction that may or may not radiate to the upper extremity (UE) [

1,

2,

3]. The possibility of persistent symptoms in nearly half of MNP patients greatly increases overall disability and places a tremendous burden on society [

1,

3]. A study looking at the causes of upper quadrant pain revealed that adults' neck pain increased with prolonged computer and mobile device use without physical activity [

4].

MNP and its associated symptoms are commonly treated conservatively with electrical modalities, manual therapy, and exercise [

3,

5]. According to a systematic review, cervical mobilization and manipulation have comparable benefits on pain, function, and patient satisfaction. A review has reported that several cervical manipulations over time may reduce pain and improve function compared with drugs and has also shown that cervical mobilisation (CM) is equally effective as manipulation [

6]. Given the correlation between reduced thoracic spine mobility and neck pain as well as the increased risk of cervical manipulation, thoracic manipulation (TM) and CM were preferred in the usual care group in this study [

7]. In addition, it has not been sufficiently shown through research whether therapeutic exercises (TEs) are beneficial for those with neck discomfort [

8]. Although the plausible cause of cervicobrachial pain is mechanosensitive neural tissue, a study stated that only 19.9% of cases are neurogenic and implied that not all "positive tension tests" indicate negative neurodynamics [

9,

10].

According to studies, there are myofascial expansions (ME) where the deep fascia (DF) joins the various muscles of the upper quarter region (UQR), which may result in cervicobrachial discomfort and nociceptive pain [

11]. The upper extremities, neck and head are interconnected by the ME of the deep lamina of the deep cervical fascia (DCF), thus forming the myofascial continuum (MC) of the UQR [

12]. The proprioceptors have the potential to develop into nociceptors, converting mechanical inputs into pain signals [

12]. Also, an alteration in the hyaluronan’s viscosity leads to adhesions resulting in altered activation of the mechanoreceptors inducing pain [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Thus, dysfunctions of DCF may be a plausible causative factor of nonspecific pain in the UQR associated with MNP. The restricted movement of collagen and elastin fibres due to the increased viscosity of the ground substance is restored by fascial manipulation (FM). The flexibility of myofascial structures may be increased by manipulating the points at the densified centre of coordination (CC) and centre of fusion (CF), which would improve fascial mobility and reduce symptoms [

17,

18]. Sequential yoga poses (SYP) restore fluid flow and improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the muscles by reducing the thixotropy of the ground substances [

19,

20,

21]. The patient-specific functional scale (PSFS) and the numeric pain rating scale (NPRS), respectively, were employed in this study to evaluate function and pain [

22].

The management of MNP normally demands an extensive course of treatment without a discernible benefit. Concomitant symptoms of the upper quarter region may develop as a result of the DCF’s anatomical MC being impaired. This mandates a carefully planned study that makes use of DCF manipulation in MNP. Thus, this study intended to compare the effectiveness of FM of DCF and SYP to the usual care, which included home-based therapeutic exercises (TE), thoracic manipulation (TM), cervicothoracic manipulation (CTM), and cervical mobilization (CM), in patients with subacute and chronic MNP.

2. Materials and Methods:

2.1.

A total of 125 participants aged 18-45 years with subacute or chronic MNP for three weeks or more were screened. Patients with inflammatory conditions, skin infections, bony lesions, vestibular balance issues, sensory or motor deficiencies of the upper quadrant, UQR surgical/traumatic history within the past year were excluded from the study. The Institutional Research (IRC) and Ethics Committees (IEC) of Kasturba Medical College (KMC) and Kasturba Hospital (KH) (ECR/146/Inst/KA/2013/RR-19), MAHE, Manipal, Karnataka, India, gave their approval for the study. The trial was registered on January 24, 2020, at ClinicalTrials.gov (CTRI/2020/01/022934), with approval ID 790/2019 IEC.

2.2. Study design:

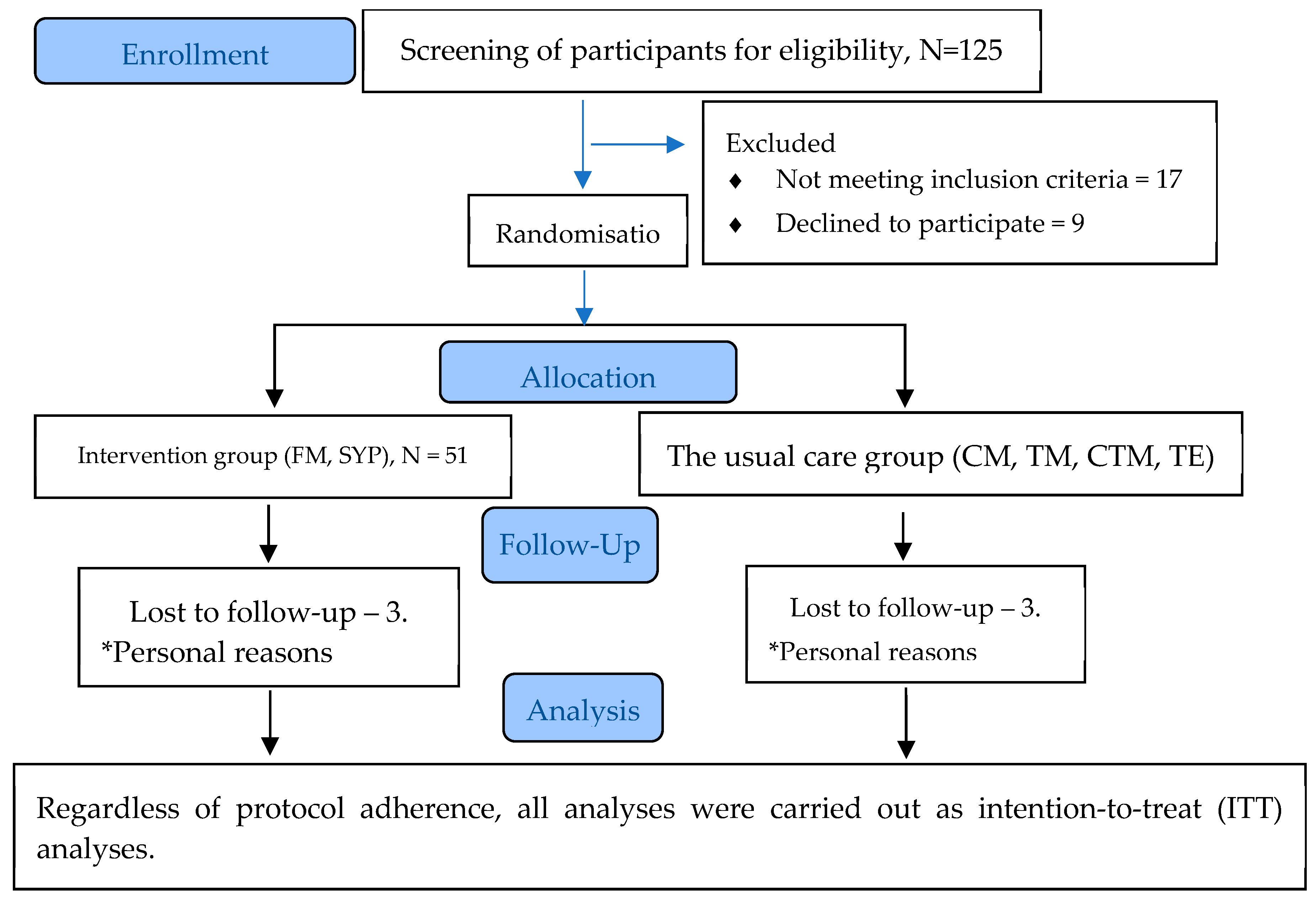

Two parallel groups were used in this pragmatic, outcome assessor-blinded, randomised controlled trial. Ninety-nine participants were recruited for this study. The flow of the study is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.3. Interventions:

CM, TM, CTM and TE were delivered to the patients in the usual care group (UCG), whereas the participants in the intervention group (IG) received FM. Both groups received treatment during day one and the subsequent three treatment sessions with a minimum of 4 days between the sessions. The instructions pertaining to the home-based TE for the UCG and SYP for the IG were provided during the first treatment session and were monitored during the subsequent treatment sessions.

Usual care group (CM, CTM, TM and TE)

Mobilization includes oscillatory movements with a larger amplitude (for treating pain) and a smaller amplitude movement at the end of the range (for treating stiffness). For the treatment of muscle spasm, a sustained position was maintained at a point where movement was restricted by muscle spasm and was interspersed with oscillatory mobilisation. Manipulation (unidirectional thrust movement) includes cervicothoracic and upper thoracic manipulation (rotation gliding C7–T3) and thoracic manipulation (rotation gliding T4–T9) [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

Therapeutic exercises (TE):

TE includes flexibility, craniocervical flexion (CCF) re-education, deep neck flexor/extensor and axio-scapular muscle training [

3,

8].

Intervention group (FM and SYP)

The intervention group received fascial manipulation® (FM) and sequential yoga poses (SYP).

Fascial Manipulation®:

Fascial manipulation® (FM) includes locating the densified points, also known as the centre of coordination (CC) and centre of fusion (CF), on the deep fascia and applying manipulation (deep friction massage) for 5-8 minutes at each densified point using knuckles or elbows [

16,

17,

27]. High reliability was shown for the validity of movement as well as palpation verifications in coxarthrosis patients using the FM approach, even when carried out by inexperienced FM practitioners [

27]. The exact locations of the CC and CF points and the treatment procedures are depicted in detail in the study protocol [

28].

Sequential yoga poses:

The details of the sequences of SYP and the methods of postures are clearly illustrated in the study protocol [

28]. Each posture was initially held for five breath cycles and progressed by increasing the number of breath cycles [

20,

28].

Intervention adherence:

The effectiveness of rehabilitation exercises is increased by strict adherence to them. Few authors have reported that back pain patients may obtain better benefits from strong exercise adherence [

29,

30]. The significance of the proper execution of TE and SYP was emphasised to the patients.

2.4. Outcomes

Primary outcome measure

Secondary outcome measures

Patient-specific functional scale (PSFS)

Fear-avoidance belief questionnaire – physical activity (FABQ-PA)

Elbow extension range of motion during upper limb neurodynamics test 1 (ULNT1).

Numeric Pain Rating Scale:

The NPRS is a valid and reliable scale used for MNP patients with moderate reliability (ICC = 0.67; [0.27 to 0.84]) [

22]. A reduction of 2 points in the NPRS is usually regarded as the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain [

31]. NPRS values were collected during baseline and before the 2

nd, 3

rd, and 4

th treatment sessions. Principal analysis was performed for changes in the mean between the groups from baseline to the 2

nd, 3

rd, and 4

th treatment sessions.

Patient-Specific Functional Scale:

In the PSFS, patients' three most difficult activity limitations are quantified. The overall score is calculated by dividing the total number of activities by the sum of all activity scores. The minimum detectable change (MDC) is 2 points for average ratings and 3 points for single activity scores [

32]. The data are shown as the mean difference between groups. Analysis was conducted to identify changes between the baseline and the last treatment session as well as between the groups.

Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire- physical activity (FABQ-PA)

The fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire (FABQ-PA) examines patients' dread of pain and subsequent avoidance of physical activity as a consequence of that fear [

33]. More significant fear-avoidance beliefs are indicated by FABQ-PA scores above 15 [

34]. FABQ-PA results contain a total score, and when it is 15 or higher, it can be regarded as elevated. Lee et al. have demonstrated that the FABQ-PA questionnaire is reliable with an ICC value of 0.81 and a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.90 [

35]. Principal analyses were performed to determine changes between the baseline and during the final treatment session and the results are presented as the mean difference between groups.

Elbow extension ROM during the upper limb neurodynamic test:

The elbow extension ROM (EEROM) is the region of the elbow range during ULNT1, where the patient feels discomfort measured with a universal goniometer [

36]. The EEROM during ULNT1 correlates with the instant of submaximal pain in neck pain that can be quantified with accuracy in clinical setting [

37]. The analysis was performed for changes from baseline to every treatment session and between the groups.

2.5. Recruitment, allocation, and implementation:

The patients underwent physical and radiographic assessments by the orthopedician. Patients with MNPs who had any alarming signs for manual therapy were excluded. Participants were randomly assigned to either the control group or the intervention group using a 1:1 allocation ratio. The sequence was computer-generated using the

www.randomiser.org website. Sixteen blocks of 10 people (5 in the CG and 5 in the IG) were used. Using sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes, the participants were divided into groups. The participants who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and consented to participate in the trial were randomised. The outcome assessor was blinded, and the same outcome assessors performed all post allocation assessments.

2.6. Statistical methods:

Repeated measures ANOVA was used for all continuous primary and secondary outcomes. All statistical tests were carried out at a 5% (two-sided) significance level using the IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp). The mean scores are reported for all the outcomes measured between different time points of measurement. The differences in all outcomes between the interventional and control groups are reported. Regardless of the protocol's adherence, all significant analyses—including all individuals who were randomly assigned—were carried out as intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics:

Three patients from the IG and three patients from the UCG withdrew during the follow-up period; as a result, 48 patients in the CG and 45 patients in the UCG completed the study, as shown in

Figure 1. The participant’s demographic characteristics are shown in

Table 1.

3.2.

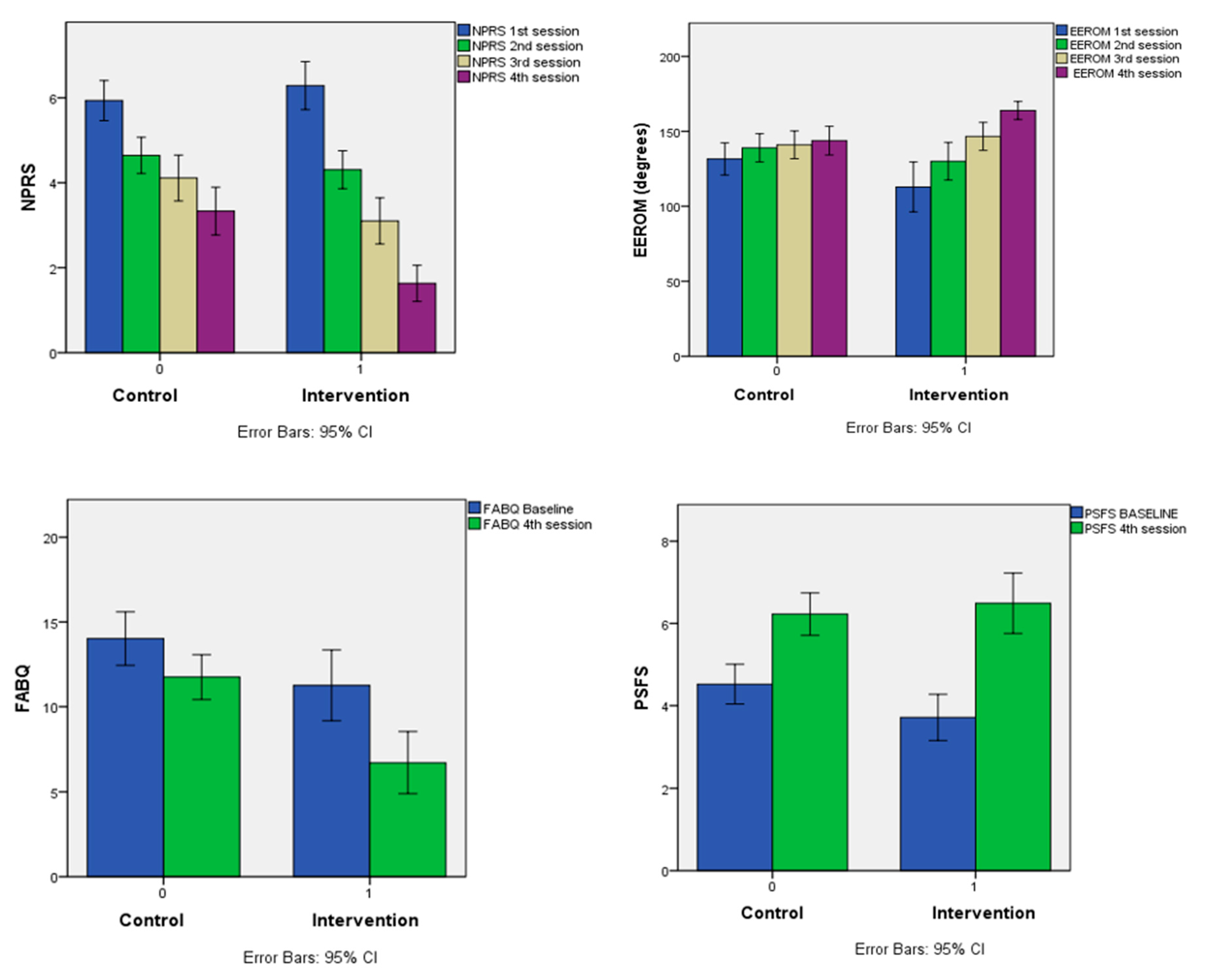

A repeated-measures ANOVA was performed to determine the effect of the IG (FM and SYP) compared to the CG (CM, TM, CTM and TE) on NPRS and EEROM (over four measurement time points) and FABQ-PA and PSFS (over two measurement time points). The means and the standard deviations for all the dependent variables are reported in

Table 2.

3.2.1. NPRS

The Wilke lambda was statistically significant, Wilke lambda = 0.16, F (3, 90) = 156.98, P<0.01, partial η

2 = 0.840, indicating a change in the NPRS score across the time frame with consecutive sessions. Additionally, there was a significant difference in the NPRS score with the group interaction, Wilke Lamda = 0.699, F (3, 90) =156.98, P<0.01, partial η

2 = 0.301, indicating that the variation in the means of NPRS over repeated measurement occasions varied as a function of the group, as shown in

Table 3.

Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated, χ

2 (5) = [32.483], p< 0.001; therefore, degrees of freedom were corrected using Huynh-Feldt estimates of sphericity (ε = 0.823). The within-subjects’ effects on the NPRS score were statistically significant, Hyunh-Feldt F (2.469, 227.17) = 270.58, P< 0.001, partial η

2 = 0.746. Additionally, the group had a significant interaction effect on NPRS, Hyunh – Feldt F (2.469, 227.17) = 22.48, P< 0.001. Partial η

2 = 0.196 showing an interaction between the NPRS measurement occasions and the treatment groups. Additionally, the difference in the repeated measures of the NPRS over time differed between the treatment groups. The mean differences between the IG and CG in the NPRS 3rd and 4

th sessions were -1.009 (p< 0.05) and -1.701 (p< 0.001), respectively, suggesting a significant reduction in pain in the IG when compared to the CG at the 3

rd and 4

th sessions, as depicted in

Table 4.

3.2.2. EEROM

The Wilke lambda was statistically significant, Wilke lambda = 0.58, F (3, 90) = 21.697, P<0.001, partial η

2 = 0.420, indicating a change in the EEROM across the sessions. Additionally, there was a significant difference in the EEROM with the group interaction, Wilke Lamda = 0.744, F (3, 90) =10.33, P<0.01, partial η

2 = 0.256, indicating that the variation in the EEROM means during the subsequent measurements varied as a function of the group, as shown in

Table 3.

Mauchly’s test (P< 0.001) implied that the sphericity assumption was not met, whereas the Greenhouse‒Geisser Epsilon value was 0.491, suggesting the use of Greenhouse‒Geisser adjustment. The within-subjects effects on EEROM were statistically significant, Greenhouse‒Geisser, F (1.472, 135.439) = 53.897, P< 0.001, partial η

2 = 0.369. Additionally, there was a significant treatment group interaction effect on EEROM, Greenhouse‒Geisser F (1.472, 135.439) = 21.46, P< 0.001, partial η

2 = 0.189. These results showed an interaction between the EEROM measurement occasions and the treatment groups. Additionally, the differences in the repeated measures of EEROM over the subsequent sessions differed across the treatment groups. These results are presented in

Table 3.

The Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparison of each group's average EEROM between the sessions within subjects indicates a difference that is statistically significant (p<0.001). There were no statistically significant differences between the IG and CG between the baseline and first 3 sessions. The mean difference between the IG and CG in EEROM in the 4

th session was 20.120 (p< 0.001), suggesting a considerable improvement in EEROM in the IG compared to the CG from baseline to the 4

th session, as shown in

Table 4.

3.2.3. FABQ-PA

The Wilke lambda is statistically significant, Wilke lambda = 0.565, F (1, 91) =70.023, P<0.01, partial η

2 = 0.435, indicating a change in the FABQ-PA in the 4

th session compared to the baseline. Additionally, there is a significant difference in the FABQ-PA score with the group interaction, Wilke Lamda = 0.921, F (1, 91) =7.806, P=0.06, partial η

2 = 0.079, indicating that the variation in the means of FABQ-PA measurements on different occasions varies as a function of the group. Mauchly’s test of sphericity (P< 0.001) indicated that the assumption of sphericity was not met, whereas the Greenhouse‒Geisser Epsilon value was > 0.75, suggesting the use of Huynh-Feldt adjustment. The within-subject effects on FABQ-PA were statistically significant, Huynh-Feldt F (1, 91) = 70.023, P< 0.001. Additionally, there was a significant difference in the between-group interaction effect, Huynh-Feldt F (1, 91) = 7.806, P=0.006. These results, as reported in

Table 3, demonstrated an interaction between the FABQ-PA measurement occasions and the treatment groups. Additionally, the differences in the measurement of EEROM from baseline to follow-up differed across the treatment groups. The mean difference between the IG and CG of the FABQ-PA during the follow-up was -5.036 (p<0.001), indicating a difference that is statistically significant in the FABQ-PA during the follow-up compared to the baseline score and is reported in

Table 4.

3.2.4. PSFS

The Wilke lambda was statistically significant, Wilke lambda = 0.535, F (1, 91) =79.023, P<0.01, indicating a change in the PSFS from baseline to follow-up. Additionally, there is a significant difference in the PSFS with the group interaction, Wilke Lamda = 0.953, F (1, 91) =4.517, P=0.36, indicating that the variation in the means of PSFS measurement during the follow-up varies as a function of the group.

Mauchly’s test (P< 0.001) indicated that the sphericity assumption was not met. The Greenhouse‒Geisser Epsilon value is > 0.75, suggesting the use of Huynh--Feldt adjustment with the univariate test of the mean difference. The within-subject effects on PSFS are statistically significant, Huynh-Feldt F (1, 91) = 79.043, P< 0.001. Additionally, there was a substantial difference in the between-group interaction effect, Huynh-Feldt F (1, 91) = 4.517, P< 0. 001, as indicated in

Table 3.

The Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparison of each group's average PSFS scores (averaged across the sessions) was not statistically significant, p= 0.412. The mean difference in PSFS between the IG and CG during follow-up was 0.263 (p=0.566), suggesting no statistically significant difference in the PSFS value in the IG compared to the CG, as specified in

Table 4. The comparison of effects between the CG and IG on all the outcomes at different timepoints of measurement is shown in

Figure 2

4. Discussion

The results indicate that there is a reduction in pain and fear avoidance beliefs (FAB), as well as improvement in function and EEROM, during the subsequent treatment sessions in both the IG (FM and SYP) and CG (CM, TM, CTM and TE). The results demonstrated that there was a significant reduction in pain (third & fourth sessions) and FAB as well as improvement in function and EEROM (fourth session) in the IG compared to the CG.

The reduction in pain as measured by the NPRS was statistically significant. The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for chronic persistent musculoskeletal pain is considered to be 2 (i.e., patients are usually considered improved when there is a reduction in NPRS by 2) [

31]. Few authors have reported that the cut-off values for the change in NPRS for the moderate (4–6), severe pain (7–10), and moderate plus severe pain (4–10) groups were 1.3, 1.8, and 1.5, respectively, based on the pretreatment pain score. Therefore, it was suggested that, for practical purposes, MCID values for change in the NPRS scale can be rounded up to 1 regardless of the degree of pain severity prior to the treatment [

38]. Given this, there was a noticeable decrease in pain in the third and fourth sessions in the IG compared to the CG. Considering the partial eta squared (η

2p) values of 0.07 (third session) and 0.207 (final session), there were moderate and large effect sizes in the 3

rd and 4

th sessions, respectively, between the IG and CG. This study's findings are consistent with those of a recent study, where subsequent therapy sessions saw a significant reduction in pain using standard FM, whereas there was a substantial pain reduction in the 3

rd session and 1-month follow-up while using the modified FM method. [

39].

The EEROM during the ULNT1 data indicated that there was a substantial improvement in the EEROM in all subsequent sessions compared to the previous sessions in both the intervention and control groups. Few studies have reported that an improvement of approximately 7·5° in EEROM can be considered the minimal important difference [

36,

37] In this study, the mean difference between the IG and CG in EEROM in the 4

th session was 20°, suggesting a considerable improvement in EEROM in the IG compared to the CG from baseline to the 4

th session. Additionally, the η2p value of 0.126 in the last session showed a larger effect size in the EEROM during ULNT1 when the IG was compared with the CG. Costello M et al reported greater immediate improvements in EEROM during ULNT1 following soft tissue mobilisation in patients with cervicobrachial pain [

36]. Patients with reduced neural extensibility in their upper limbs, as indicated by decreased EEROM during ULNT1, showed a decreased length of the upper trapezius, thus showing that restrictions in the soft tissues that surround the nerves may impair neural mobility [

40]. Few authors have discussed the plausible involvement of deep fascia in fascial entrapment neuropathy which presents a difficult diagnostic problem [

41]. Considering the rich innervation of the deep fascia and the presence of tender taut bands on the soft tissues of the UQR associated with myofascial dysfunctions, may also give nociceptive input to the nervous system, thus contributing to the MNP perceived by the patient [

42,

43,

44]. Thus, in this study, although the treatment in the IG targets the soft tissues of the UQR, there is a profound improvement in neural extensibility, as indicated by an increase in the EEROM during ULNT1.

The mean difference between the IG and CG on the FABQ during the follow-up was -5.036 (p<0.001). suggesting a statistically significant difference in FABQ scores in the IG compared to the CG. A change of 4 points on the FABQ-PA is considered MCID, which seems to accurately identify meaningful changes in fear-avoidance beliefs [

45]. There was a reduction of approximately 5 points in the IG compared to the change of just 2 points in the CG. Additionally, there was a larger effect size (η

2p= 0.17) in the IG during the 4

th session compared to the baseline. Thus, the IG can be considered clinically significant in reducing the FAB compared with the CG in this study. A study that explored the effectiveness of myofascial release also demonstrated a substantial decrease in the FAB score in patients with chronic low back pain [

46].

The PSFS data showed that there was a change in the PSFS value from baseline to follow-up in both the IG and CG. The mean difference in PSFS between the IG and CG during follow-up was 0.263 (p=0.566), suggesting no statistically significant difference. Similarly, there was a very small effect size (η

2p= 0.04) when comparing the 4

th session with the baseline between the control and intervention groups. However, a study has reported that the minimum detectable change (MDC) for PSFS is 2 points for average ratings [

32]. The mean change in the PSFS score from baseline (4.52± 1.592) to follow-up (6.23±1.696) in the CG was < 2, whereas the mean change from baseline (3.71±1.958) to follow-up (6.49 ± 2.55) in the IG was > 2, which is above the MDC, thus clinically showing that the IG may be better at improving the PSFS than the CG. The positive influence of FM in restoring function was also reported in a recent study by Kamani et al. in patients with chronic ankle instability [

18].

5. Conclusions

The fascia-directed approach, such as FM and SYP, can be considered an effective tool in the effective treatment of patients with MNP, reducing pain and fear avoidance behavior as well as improving the function and extensibility of the upper quarter region. Future studies are needed in order to investigate the long-term efficacy of FMs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, P.R., S.B., R.G., C.F., AND A.P.; methodology, P.R., S.B., R.G., A.P.; formal analysis, P.R., S.B., R.G., A.P.; investigation, P.R, S.B., R.G., A.P., C.P., C.F. AND A.S.; resources, P.R.; data curation, P.R.; writing—original draft preparation, P.R., S.B., R.G., A.P.; writing—review and editing, P.R., S.B., R.G., A.P., C.P., C.F., V.J., and A.S.; visualisation, P.R. AND S.B.; supervision, P.R., S.B., A.P.; project administration, P.R., S.B.

Funding

This study did not receive any external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to the Declaration of Helsinki, the study was carried out. The Institutional Research (IRC) and Ethics Committees (IEC) of Kasturba Medical College (KMC) and Kasturba Hospital (KH) (ECR/146/Inst/KA/2013/RR-19), MAHE, Manipal, Karnataka, India, gave their approval for the study. The trial was registered on January 24, 2020, at ClinicalTrials.gov (CTRI/2020/01/022934), with approval ID 790/2019 IEC.

Informed Consent Statement

Before taking part in the study, each subject gave their informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

On request, the corresponding author will provide access to the data used in this work. Due to ethical constraints, the data are not publicly accessible.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Muñoz-García, D.; Gil-Martínez, A.; López-López, A.; Lopez-de-Uralde-Villanueva, I.; La Touche, R.; Fernández-Carnero, J. Chronic Neck Pain and Cervico-Craniofacial Pain Patients Express Similar Levels of Neck Pain-Related Disability, Pain Catastrophizing, and Cervical Range of Motion. Pain Res Treat 2016, 2016, 7296032. [CrossRef]

- Guzman, J.; Hurwitz, E.L.; Carroll, L.J.; Haldeman, S.; Côté, P.; Carragee, E.J.; Peloso, P.M.; van der Velde, G.; Holm, L.W.; Hogg-Johnson, S.; et al. A New Conceptual Model of Neck Pain: Linking Onset, Course, and Care: The Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008, 33, S14-23. [CrossRef]

- Dennison, Bryan; Leal, Micheal Neck and Arm Pain Syndromes. Evidence-Informed Screening, Diagnosis, and Management.; 1st ed.; Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone, 2011;

- Yeun, Y.-R.; Han, S.-J. Factors Associated with Neck/Shoulder Pain in Young Adults. Biomedical Research-tokyo 2017.

- Ayoub, L.J.; Seminowicz, D.A.; Moayedi, M. A Meta-Analytic Study of Experimental and Chronic Orofacial Pain Excluding Headache Disorders. Neuroimage Clin 2018, 20, 901–912. [CrossRef]

- Gross, A.; Langevin, P.; Burnie, S.J.; Bédard-Brochu, M.-S.; Empey, B.; Dugas, E.; Faber-Dobrescu, M.; Andres, C.; Graham, N.; Goldsmith, C.H.; et al. Manipulation and Mobilisation for Neck Pain Contrasted against an Inactive Control or Another Active Treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015, CD004249. [CrossRef]

- Cleland, J.A.; Childs, J.D.; Fritz, J.M.; Whitman, J.M.; Eberhart, S.L. Development of a Clinical Prediction Rule for Guiding Treatment of a Subgroup of Patients with Neck Pain: Use of Thoracic Spine Manipulation, Exercise, and Patient Education. Phys Ther 2007, 87, 9–23. [CrossRef]

- Gross, A.; Kay, T.M.; Paquin, J.-P.; Blanchette, S.; Lalonde, P.; Christie, T.; Dupont, G.; Graham, N.; Burnie, S.J.; Gelley, G.; et al. Exercises for Mechanical Neck Disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015, 1, CD004250. [CrossRef]

- Gangavelli, R.; Nair, N.S.; Bhat, A.K.; Solomon, J.M. Cervicobrachial Pain - How Often Is It Neurogenic? J Clin Diagn Res 2016, 10, YC14-16. [CrossRef]

- Butler, D. Mobilisation of the Nervous System; 1st ed.; Churchill Livingstone: Melbourne, 1991;

- Purslow, P.P. Muscle Fascia and Force Transmission. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2010, 14, 411–417. [CrossRef]

- The Tensional Network of the Human Body; Schleip, Robert, Findley, T., Chaitow, L., Huijing, P., Eds.; Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone, 2012;

- Raja G, P.; Fernandes, S.; Cruz, A.M.; Prabhu, A. The Plausible Role of Deep Cervical Fascia and Its Continuum in Chronic Craniofacial and Cervicobrachial Pain: A Case Report. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04560. [CrossRef]

- Bordoni, B.; Zanier, E. Clinical and Symptomatological Reflections: The Fascial System. J Multidiscip Healthc 2014, 7, 401–411. [CrossRef]

- Mathew, N.P.; Raja G, P.; Davis, F. Effect of Fascial Manipulation on Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit in Overhead Athletes A Randomized Controlled Trial – MLTJ.

- Stecco, A.; Cowman, M.; Pirri, N.; Raghavan, P.; Pirri, C. Densification: Hyaluronan Aggregation in Different Human Organs. Bioengineering (Basel) 2022, 9, 159. [CrossRef]

- Stecco, L. Fascial Manipulation for Musculoskeletal Pain; 1st ed.; Piccin, 2004;

- Kamani, N.C.; Poojari, S.; Prabu, R.G. The Influence of Fascial Manipulation on Function, Ankle Dorsiflexion Range of Motion and Postural Sway in Individuals with Chronic Ankle Instability. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2021, 27, 216–221. [CrossRef]

- Myers, T.W. Anatomy Trains: Myofascial Meridians for Manual and Movement Therapists; 3rd ed.; Churchill Livingstone;

- Joanne, A. Yoga: Fascia, Form, and Functional Movement; 3rd ed.; Handspring Publishing, 2015;

- Scaravelli, V. Awakening the Spine: Yoga for Health, Vitality, and Energy; 2nd ed.; HarperOne, 2015;

- Cleland, J.A.; Childs, J.D.; Whitman, J.M. Psychometric Properties of the Neck Disability Index and Numeric Pain Rating Scale in Patients with Mechanical Neck Pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008, 89, 69–74. [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, P.; Tehan, P. Manipulation of the Spine, Thorax and Pelvis; 4th ed.; Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone, 2016;

- Basmajian, J.V.; Nyberg, R. Rational Manual Therapies: Manipulation, Spinal Motion and Soft Tissue Mobilization; Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 1993;

- Hengeveld, E.; Banks, K. Maitland’s Vertebral Manipulation Management of Neuromusculoskeletal Disorders; 8th ed.; Elsevier, 2013; Vol. 1;

- Evans, D.W.; Breen, A.C. A Biomechanical Model for Mechanically Efficient Cavitation Production during Spinal Manipulation: Prethrust Position and the Neutral Zone. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2006, 29, 72–82. [CrossRef]

- Boyling, J.D.; Jull, G.A. Grieve’s Modern Manual Therapy: The Vertebral Column; 3rd ed.; Elsevier, 2004;

- Raja G, P.; Bhat N, S.; Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Gangavelli, R.; Davis, F.; Shankar, R.; Prabhu, A. Effectiveness of Deep Cervical Fascial Manipulation and Yoga Postures on Pain, Function, and Oculomotor Control in Patients with Mechanical Neck Pain: Study Protocol of a Pragmatic, Parallel-Group, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Trials 2021, 22, 574. [CrossRef]

- Bollen, J.C.; Dean, S.G.; Siegert, R.J.; Howe, T.E.; Goodwin, V.A. A Systematic Review of Measures of Self-Reported Adherence to Unsupervised Home-Based Rehabilitation Exercise Programmes, and Their Psychometric Properties. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e005044. [CrossRef]

- Argent, R.; Daly, A.; Caulfield, B. Patient Involvement With Home-Based Exercise Programs: Can Connected Health Interventions Influence Adherence? JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e47. [CrossRef]

- Salaffi, F.; Stancati, A.; Silvestri, C.A.; Ciapetti, A.; Grassi, W. Minimal Clinically Important Changes in Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain Intensity Measured on a Numerical Rating Scale. Eur J Pain 2004, 8, 283–291. [CrossRef]

- Stratford, P.; Gill, C.; Westaway, M.; Binkley, J. Assessing Disability and Change on Individual Patients: A Report of a Patient Specific Measure. Physiotherapy Canada 1995, 47, 258–263. [CrossRef]

- Fritz, J.M.; George, S.Z. Identifying Psychosocial Variables in Patients With Acute Work-Related Low Back Pain: The Importance of Fear-Avoidance Beliefs. Physical Therapy 2002, 82, 973–983. [CrossRef]

- George, S.Z.; Stryker, S.E. Fear-Avoidance Beliefs and Clinical Outcomes for Patients Seeking Outpatient Physical Therapy for Musculoskeletal Pain Conditions. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2011, 41, 249–259. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-C.; Chiu, T.T.W.; Lam, T.-H. Psychometric Properties of the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire in Patients with Neck Pain. Clin Rehabil 2006, 20, 909–920. [CrossRef]

- Costello, M.; Puentedura, E. “Louie” J.; Cleland, J.; Ciccone, C.D. The Immediate Effects of Soft Tissue Mobilization versus Therapeutic Ultrasound for Patients with Neck and Arm Pain with Evidence of Neural Mechanosensitivity: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Man Manip Ther 2016, 24, 128–140. [CrossRef]

- Coppieters, M.; Stappaerts, K.; Janssens, K.; Jull, G. Reliability of Detecting “onset of Pain” and “Submaximal Pain” during Neural Provocation Testing of the Upper Quadrant. Physiother Res Int 2002, 7, 146–156. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Aono, S.; Inoue, S.; Imajo, Y.; Nishida, N.; Funaba, M.; Harada, H.; Mori, A.; Matsumoto, M.; Higuchi, F.; et al. Clinically Significant Changes in Pain along the Pain Intensity Numerical Rating Scale in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0229228. [CrossRef]

- Pawlukiewicz, M.; Kochan, M.; Niewiadomy, P.; Szuścik-Niewiadomy, K.; Taradaj, J.; Król, P.; Kuszewski, M.T. Fascial Manipulation Method Is Effective in the Treatment of Myofascial Pain, but the Treatment Protocol Matters: A Randomised Control Trial—Preliminary Report. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 4546. [CrossRef]

- Edgar, D.; Jull, G.; Sutton, S. The Relationship between Upper Trapezius Muscle Length and Upper Quadrant Neural Tissue Extensibility. Aust J Physiother 1994, 40, 99–103. [CrossRef]

- Fascial Entrapment Neuropathy - Stecco - 2019 - Clinical Anatomy - Wiley Online Library Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ca.23388 (accessed on 11 September 2023).

- Cleland, J.A.; Childs, J.D.; Fritz, J.M.; Whitman, J.M. Interrater Reliability of the History and Physical Examination in Patients with Mechanical Neck Pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2006, 87, 1388–1395. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Alonso-Blanco, C.; Miangolarra, J.C. Myofascial Trigger Points in Subjects Presenting with Mechanical Neck Pain: A Blinded, Controlled Study. Man Ther 2007, 12, 29–33. [CrossRef]

- Stecco, C.; Pirri, C.; Fede, C.; Fan, C.; Giordani, F.; Stecco, L.; Foti, C.; De Caro, R. Dermatome and Fasciatome. Clin Anat 2019, 32, 896–902. [CrossRef]

- Monticone, M.; Frigau, L.; Vernon, H.; Rocca, B.; Giordano, A.; Simone Vullo, S.; Mola, F.; Franchignoni, F. Reliability, Responsiveness and Minimal Clinically Important Difference of the Two Fear Avoidance and Beliefs Questionnaire Scales in Italian Subjects with Chronic Low Back Pain Undergoing Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2020, 56, 600–606. [CrossRef]

- Arguisuelas, M.D.; Lisón, J.F.; Sánchez-Zuriaga, D.; Martínez-Hurtado, I.; Doménech-Fernández, J. Effects of Myofascial Release in Nonspecific Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Spine 2017, 42, 627. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).