Submitted:

13 September 2023

Posted:

15 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition and Processing

2.2. Data Analysis

2.2.1. Phylogeny

2.2.2. Population Genetic Analysis

2.2.3. Recombination and Linkage Disequilibrium

2.2.4. Mitochondria to Nuclear Genome Comparison

3. Results

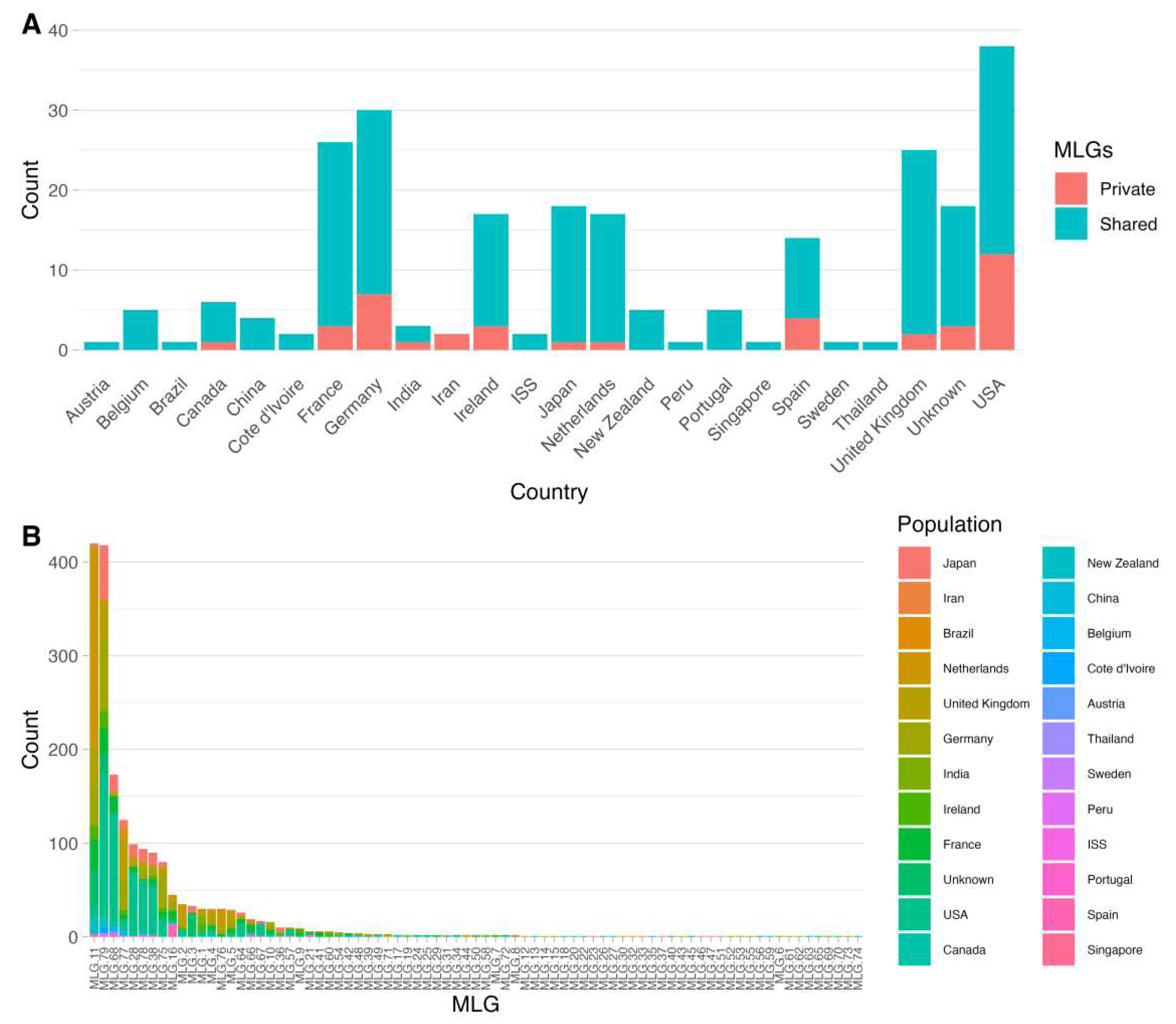

3.1. Distribution of Multilocus Genotypes Based on Mitogenome SNPs

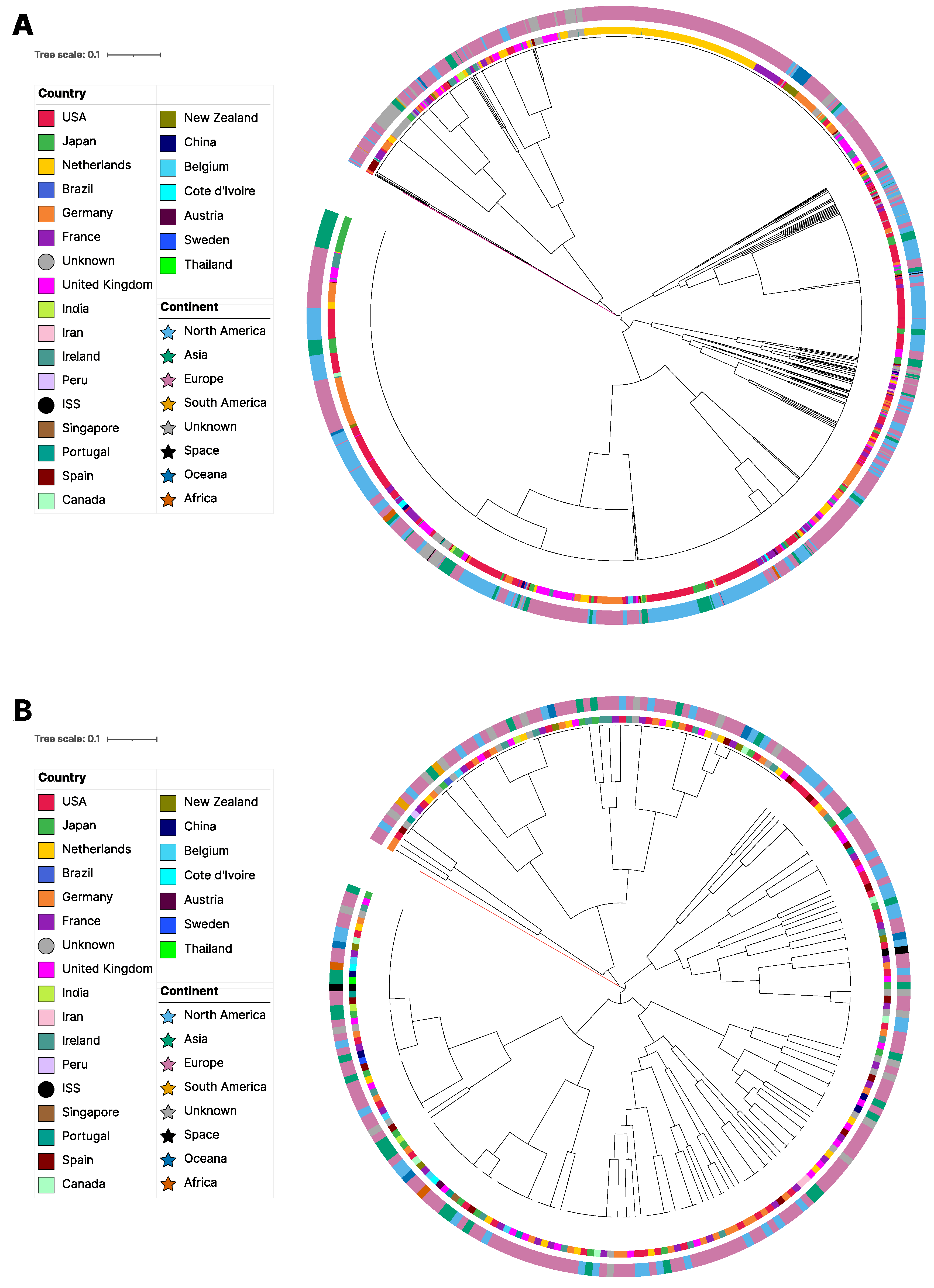

3.2. Phylogenetic Relationships among Strains and MLGs Based on Mitogenome SNPs

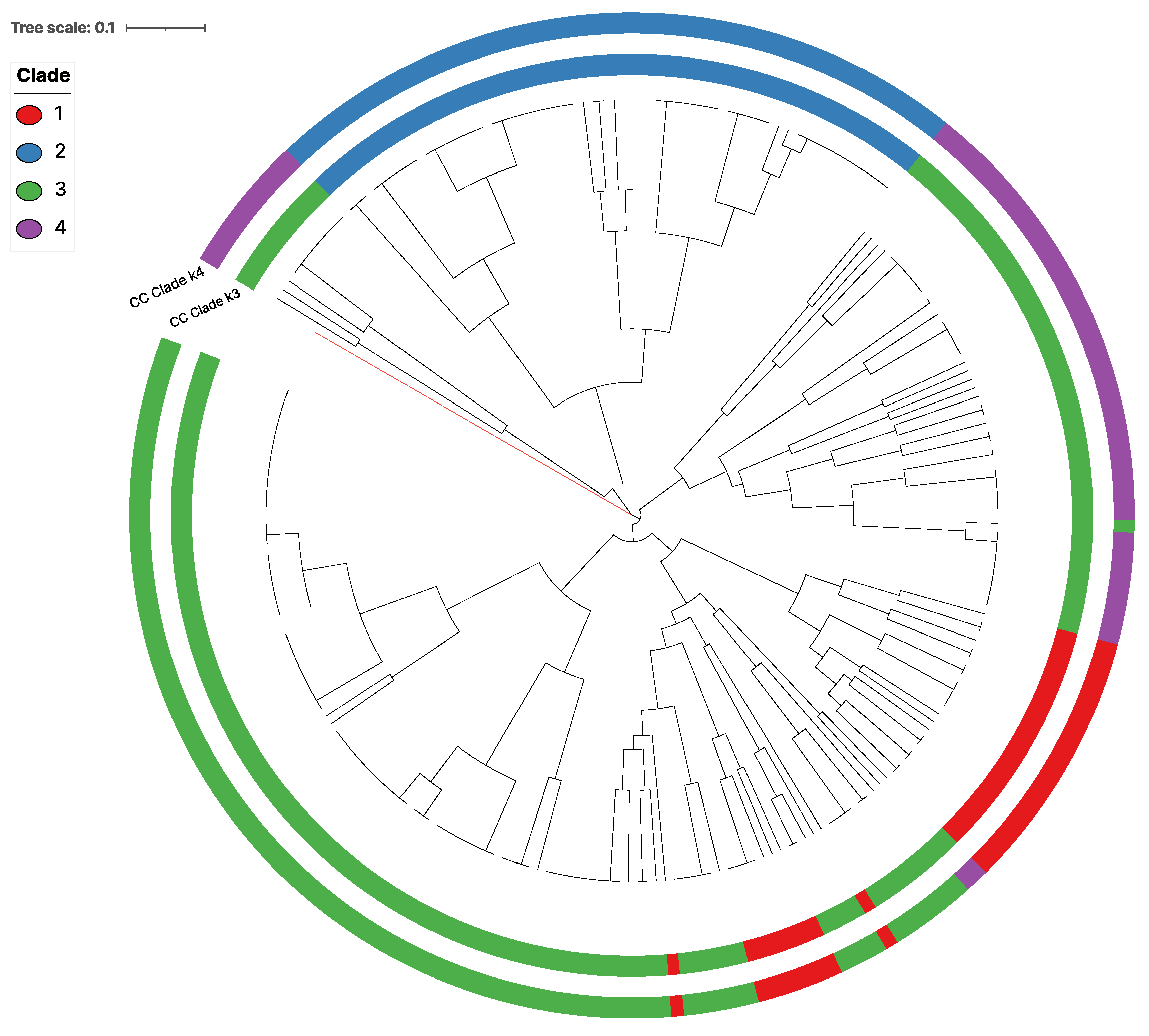

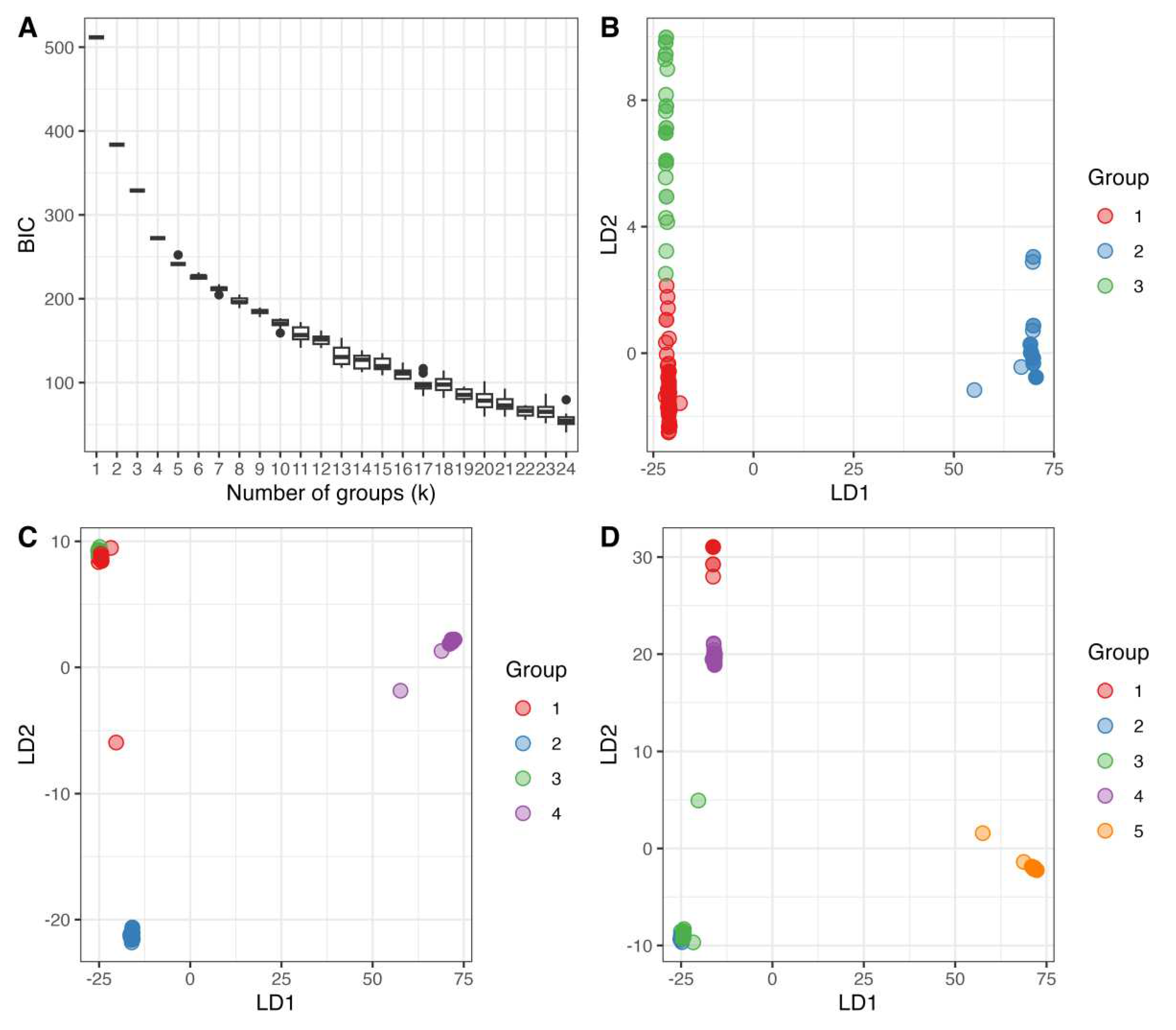

3.3. Genetic Clusters of the Global Mitogenome MLGs

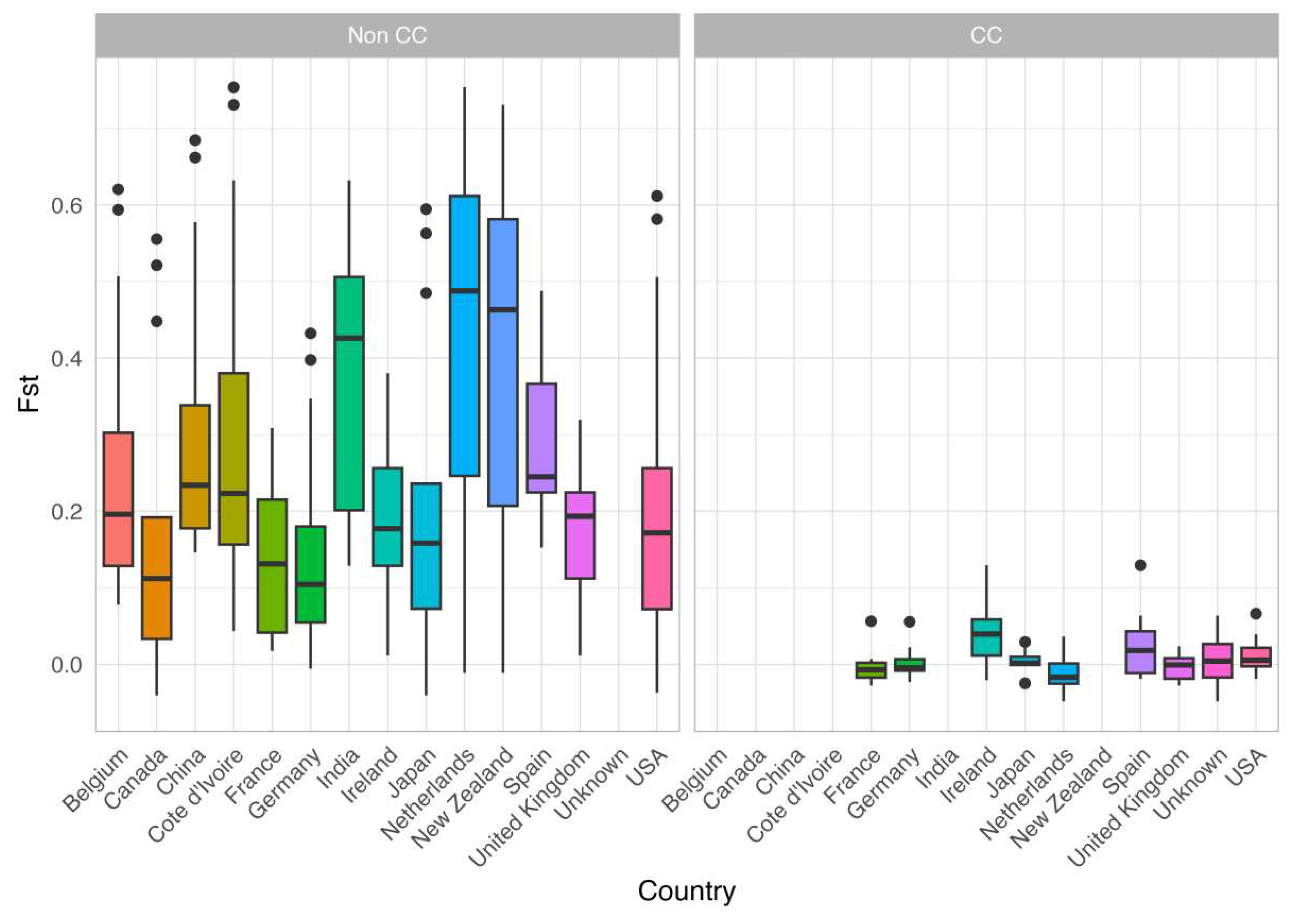

3.4. Geographic Structure

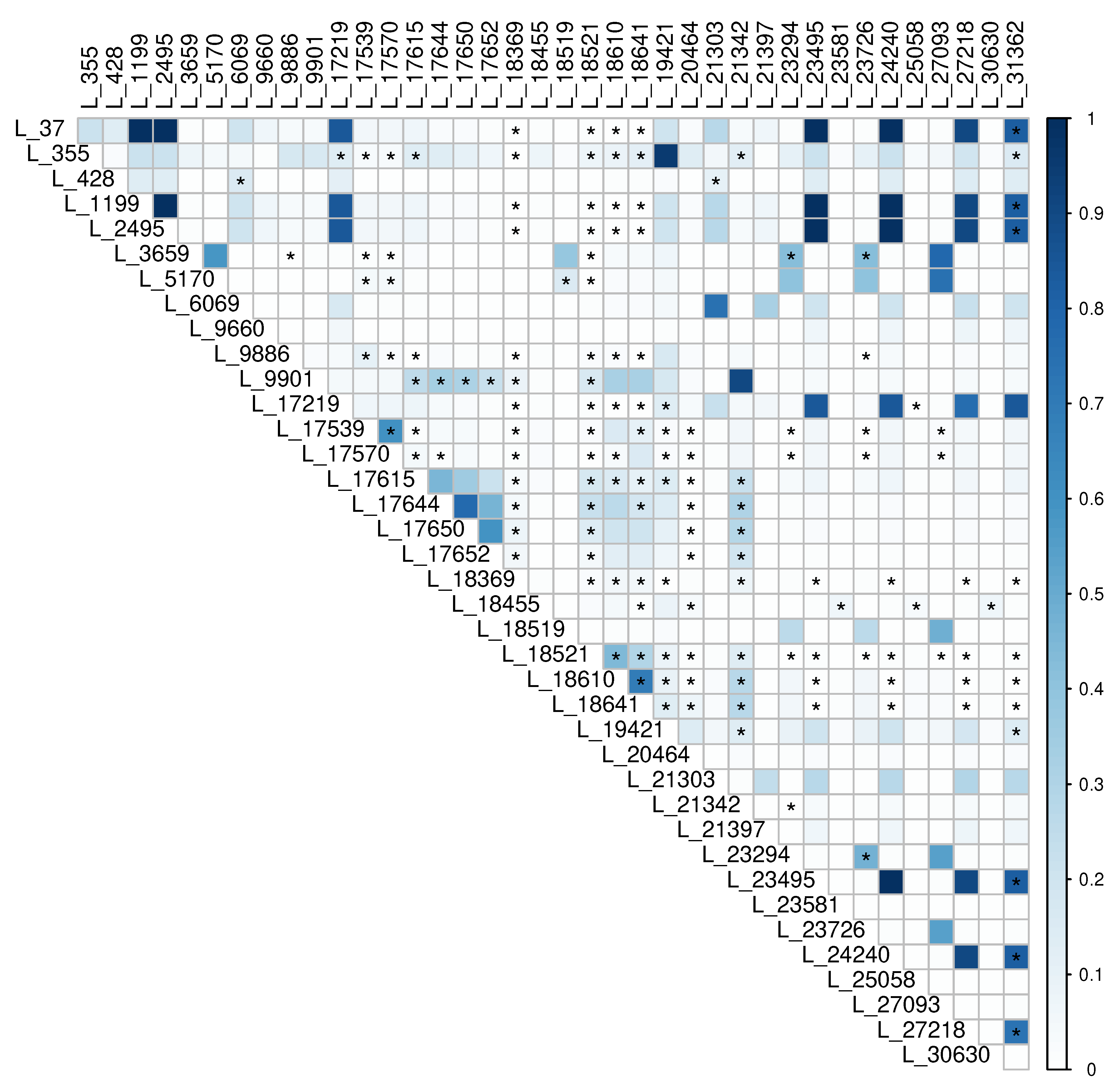

3.5. Recombination and Phylogenetic Incompatability

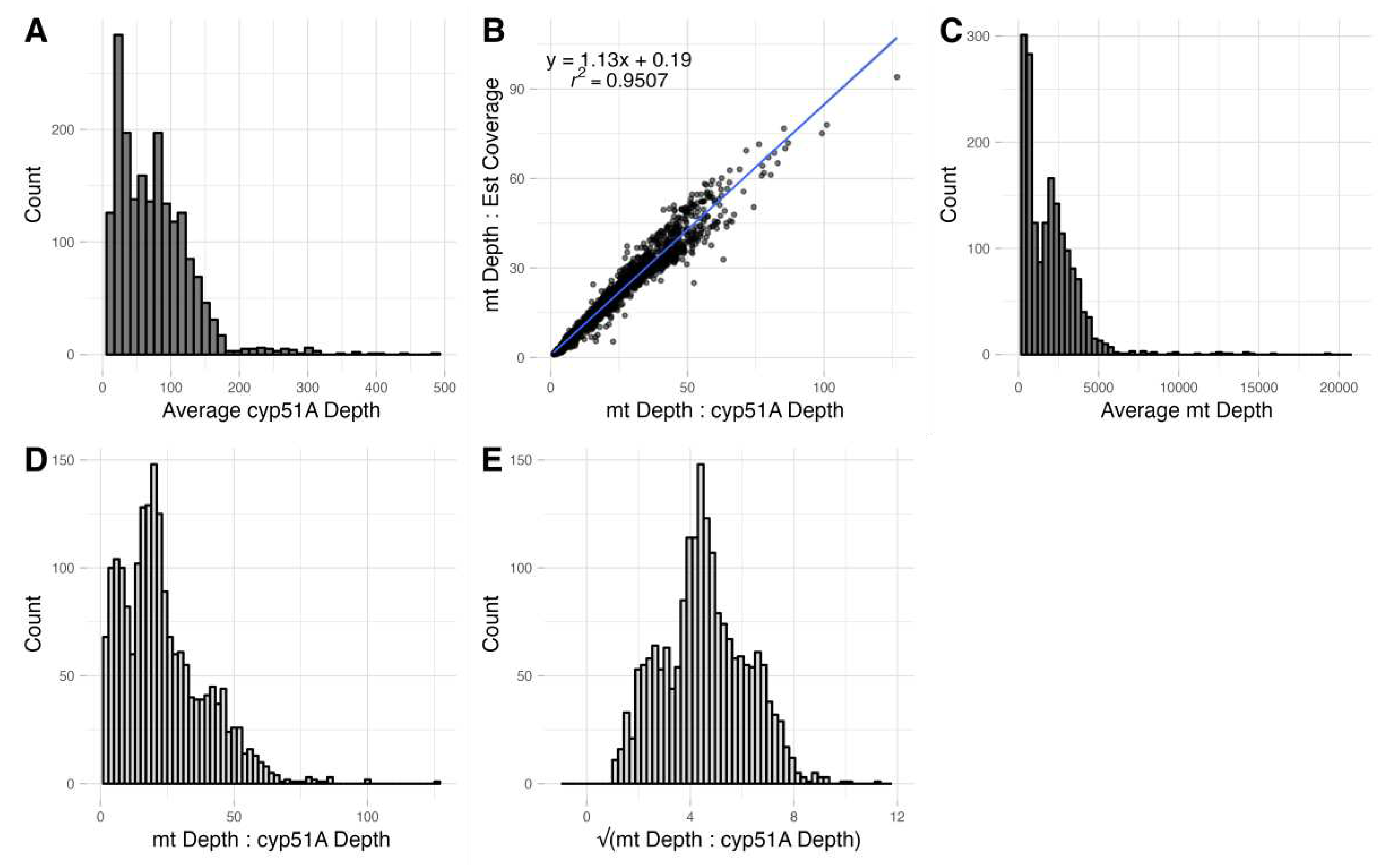

3.6. Reletive Mitogenome to Nuclear Genome Copy Number Ratio

4. Discussion

4.1. Geographic Structuring

4.2. Recombination

4.3. Relative Copy Number Ratios of Mitogenome to Nuclear Genome

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, J. Assessing Global Fungal Threats to Humans. mLife 2022, 1, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latgé, J.-P.; Chamilos, G. Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillosis in 2019. Clin Microbiol Rev 2019, 33, e00140-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knox, B.P.; Blachowicz, A.; Palmer, J.M.; Romsdahl, J.; Huttenlocher, A.; Wang, C.C.C.; Keller, N.P.; Venkateswaran, K. Characterization of Aspergillus fumigatus Isolates from Air and Surfaces of the International Space Station. mSphere 2016, 1, e00227-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulussen, C.; Hallsworth, J.E.; Álvarez-Pérez, S.; Nierman, W.C.; Hamill, P.G.; Blain, D.; Rediers, H.; Lievens, B. Ecology of Aspergillosis: Insights into the Pathogenic Potency of Aspergillus fumigatus and Some Other Aspergillus Species. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 296–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nywening, A.V.; Rybak, J.M.; Rogers, P.D.; Fortwendel, J.R. Mechanisms of Triazole Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Environmental Microbiology 2020, 22, 4934–4952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagenais, T.R.T.; Keller, N.P. Pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus in Invasive Aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2009, 22, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization WHO Fungal Priority Pathogens List to Guide Research, Development and Public Health Action 2022.

- Barber, A.E.; Sae-Ong, T.; Kang, K.; Seelbinder, B.; Li, J.; Walther, G.; Panagiotou, G.; Kurzai, O. Aspergillus fumigatus Pan-Genome Analysis Identifies Genetic Variants Associated with Human Infection. Nat Microbiol 2021, 6, 1526–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalewski, D.A.; Hinrichs, V.S.; Zinniel, D.K.; Barletta, R.G. The Pathogenicity of Aspergillus fumigatus, Drug Resistance, and Nanoparticle Delivery. Can. J. Microbiol. 2018, 64, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, B.; Lee, C.; Horianopoulos, L.C.; Jung, W.H.; Kronstad, J.W. Respiring to Infect: Emerging Links between Mitochondria, the Electron Transport Chain, and Fungal Pathogenesis. PLOS Pathogens 2021, 17, e1009661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahl, N.; Dinamarco, T.M.; Willger, S.D.; Goldman, G.H.; Cramer, R.A. Aspergillus fumigatus Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain Mediates Oxidative Stress Homeostasis, Hypoxia Responses and Fungal Pathogenesis. Molecular Microbiology 2012, 84, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Hagen, F.; Stekel, D.J.; Johnston, S.A.; Sionov, E.; Falk, R.; Polacheck, I.; Boekhout, T.; May, R.C. The Fatal Fungal Outbreak on Vancouver Island Is Characterized by Enhanced Intracellular Parasitism Driven by Mitochondrial Regulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 12980–12985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnani, T.; Soriani, F.M.; Martins, V. de P.; Policarpo, A.C. de F.; Sorgi, C.A.; Faccioli, L.H.; Curti, C.; Uyemura, S.A. Silencing of Mitochondrial Alternative Oxidase Gene of Aspergillus fumigatus Enhances Reactive Oxygen Species Production and Killing of the Fungus by Macrophages. J Bioenerg Biomembr 2008, 40, 631–636. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misslinger, M.; Lechner, B.E.; Bacher, K.; Haas, H. Iron-Sensing Is Governed by Mitochondrial, Not by Cytosolic Iron–Sulfur Cluster Biogenesis in Aspergillus fumigatus. Metallomics 2018, 10, 1687–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, R. Mitochondria-Mediated Azole Drug Resistance and Fungal Pathogenicity: Opportunities for Therapeutic Development. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basse, C.W. Mitochondrial Inheritance in Fungi. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2010, 13, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandor, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J. Fungal Mitochondrial Genomes and Genetic Polymorphisms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2018, 102, 9433–9448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Xu, J. Fungal mitochondrial inheritance and evolution. In Evolutionary Genetics of Fungi; Horizon bioscience: Wymondham, 2005; pp. 221–252. ISBN 978-1-904933-15-1. [Google Scholar]

- Joardar, V.; Abrams, N.F.; Hostetler, J.; Paukstelis, P.J.; Pakala, S.; Pakala, S.B.; Zafar, N.; Abolude, O.O.; Payne, G.; Andrianopoulos, A.; et al. Sequencing of Mitochondrial Genomes of Nine Aspergillus and Penicillium Species Identifies Mobile Introns and Accessory Genes as Main Sources of Genome Size Variability. BMC Genomics 2012, 13, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.-N.; Tang, P.; Wei, S.-J.; Chen, X.-X. Comparative and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Mitochondrial Genomes in Basal Hymenopterans. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 20972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, R. The Unmasking of Mitochondrial Eve. Science 1987, 238, 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, J. Mitochondrial Genome Polymorphisms in the Human Pathogenic Fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yan, Z.; Guo, H. Divergence, Hybridization, and Recombination in the Mitochondrial Genome of the Human Pathogenic Yeast Cryptococcus gattii. Molecular Ecology 2009, 18, 2628–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Pun, N. Mitochondrial Recombination in Natural Populations of the Button Mushroom Agaricus bisporus. Fungal Genetics and Biology 2013, 55, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebert, P.D.N.; Cywinska, A.; Ball, S.L.; deWaard, J.R. Biological Identifications through DNA Barcodes. Proc Biol Sci 2003, 270, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J. Fungal DNA Barcoding. The 6th International Barcode of Life Conference 2017, 01, 913–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlowski, M.; Stepien, P.P. Restriction Enzyme Analysis of Mitochondrial DNA of Members of the Genus Aspergillus as an Aid in Taxonomy. Microbiology 1982, 128, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yokoyama, K.; Miyaji, M.; Nishimura, K. The Identification and Phylogenetic Relationship of Pathogenic Species of Aspergillus Based on the Mitochondrial Cytochrome b Gene. Med Mycol 1998, 36, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yokoyama, K.; Miyaji, M.; Nishimura, K. Mitochondrial Cytochrome b Gene Analysis of Aspergillus fumigatus and Related Species. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2000, 38, 1352–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Iglesias, V.; Mosquera-Miguel, A.; Cerezo, M.; Quintáns, B.; Zarrabeitia, M.T.; Cuscó, I.; Lareu, M.V.; García, Ó.; Pérez-Jurado, L.; Carracedo, Á.; et al. New Population and Phylogenetic Features of the Internal Variation within Mitochondrial DNA Macro-Haplogroup R0. PLOS ONE 2009, 4, e5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H. Phylogenetic Analysis and Characterization of Mitochondrial DNA for Korean Native Cattle. 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, J.S.M.; Arasappan, D.; Bahieldin, A.; Abo-Aba, S.; Bafeel, S.; Zari, T.A.; Edris, S.; Shokry, A.M.; Gadalla, N.O.; Ramadan, A.M.; et al. Whole Mitochondrial and Plastid Genome SNP Analysis of Nine Date Palm Cultivars Reveals Plastid Heteroplasmy and Close Phylogenetic Relationships among Cultivars. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e94158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Gao, P.; Liu, S.; Amanullah, S.; Luan, F. Comparative Analysis of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in the Nuclear, Chloroplast, and Mitochondrial Genomes in Identification of Phylogenetic Association among Seven Melon (Cucumis Melo L.) Cultivars. Breeding Science 2016, 66, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, A.E.; Riedel, J.; Sae-Ong, T.; Kang, K.; Brabetz, W.; Panagiotou, G.; Deising, H.B.; Kurzai, O. Effects of Agricultural Fungicide Use on Aspergillus fumigatus Abundance, Antifungal Susceptibility, and Population Structure. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagiwara, D.; Takahashi, H.; Watanabe, A.; Takahashi-Nakaguchi, A.; Kawamoto, S.; Kamei, K.; Gonoi, T. Whole-Genome Comparison of Aspergillus fumigatus Strains Serially Isolated from Patients with Aspergillosis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2014, 52, 4202–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofgren, L.A.; Ross, B.S.; Cramer, R.A.; Stajich, J.E. The Pan-Genome of Aspergillus Fumigatus Provides a High-Resolution View of Its Population Structure Revealing High Levels of Lineage-Specific Diversity Driven by Recombination. PLOS Biology 2022, 20, e3001890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, J.; Abdolrasouli, A.; Dunne, K.; Sewell, T.R.; Zhang, Y.; Ballard, E.; Brackin, A.P.; van Rhijn, N.; Chown, H.; Tsitsopoulou, A.; et al. Population Genomics Confirms Acquisition of Drug-Resistant Aspergillus fumigatus Infection by Humans from the Environment. Nat Microbiol 2022, 7, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, D.J.; Weir, B.S.; Glare, T.; Rhodes, J.; Perrott, J.; Fisher, M.C.; Stajich, J.E.; Digby, A.; Dearden, P.K.; Cox, M.P. A Single Fungal Strain Was the Unexpected Cause of a Mass Aspergillosis Outbreak in the World’s Largest and Only Flightless Parrot. iScience 2022, 25, 105470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An Ultra-Fast All-in-One FASTQ Preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Aligning Sequence Reads, Clone Sequences and Assembly Contigs with BWA-MEM. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve Years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 2021, 10, giab008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.; et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce Framework for Analyzing Next-Generation DNA Sequencing Data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, E.M. Vcf2phylip v2.0: Convert a VCF Matrix into Several Matrix Formats for Phylogenetic Analysis. 2019.

- Gkanogiannis, A. fastreeR: Phylogenetic, Distance and Other Calculations on VCF and Fasta Files 2023.

- Paradis, E.; Schliep, K. Ape 5.0: An Environment for Modern Phylogenetics and Evolutionary Analyses in R. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 526–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: An Online Tool for Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamvar, Z.N.; Tabima, J.F.; Grünwald, N.J. Poppr : An R Package for Genetic Analysis of Populations with Clonal, Partially Clonal, and/or Sexual Reproduction. PeerJ 2014, 2, e281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jombart, T.; Devillard, S.; Balloux, F. Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components: A New Method for the Analysis of Genetically Structured Populations. BMC Genet 2010, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.H.D.; Feldman, M.W.; Nevo, E. Multilocus structure of natural populations of Hordeum spontaneum. Genetics 1980, 96, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.M.; Smith, N.H.; O’Rourke, M.; Spratt, B.G. How Clonal Are Bacteria? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1993, 90, 4384–4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Simko, V. R Package “Corrplot”: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix 2021.

- Xu, J. Fundamentals of Fungal Molecular Population Genetic Analyses. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2006, 8, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, A.; Baker, D.M.; Platt, J.L.; Wares, J.P.; Latgé, J.P.; Taylor, J.W. Cryptic Speciation in the Cosmopolitan and Clonal Human Pathogenic Fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Evolution 2005, 59, 1886–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, C.H.W.; Gibbons, J.G.; Fedorova, N.D.; Meis, J.F.; Rokas, A. Evidence for Genetic Differentiation and Variable Recombination Rates among Dutch Populations of the Opportunistic Human Pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Molecular Ecology 2012, 21, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashu, E.E.; Hagen, F.; Chowdhary, A.; Meis, J.F.; Xu, J. Global Population Genetic Analysis of Aspergillus fumigatus. mSphere 2017, 2, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Shakya, V.P.S.; Idnurm, A. Exploring and Exploiting the Connection between Mitochondria and the Virulence of Human Pathogenic Fungi. Virulence 2018, 9, 426–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, H. Current Perspectives on Mitochondrial Inheritance in Fungi. Cell Health and Cytoskeleton 2015, 7, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korfanty, G.; Stanley, K.; Lammers, K.; Fan, Y.Y.; Xu, J. Variations in Sexual Fitness among Natural Strains of the Opportunistic Human Fungal Pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2021, 87, 104640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, P.; Rao, W.; Hou, B.; Zhang, Y. Genetic Differentiation and Widespread Mitochondrial Heteroplasmy among Geographic Populations of the Gourmet Mushroom Thelephora Ganbajun from Yunnan, China. Genes 2022, 13, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, H.; Liu, C.; Mi, F.; Wang, R.; Mo, M.; Xu, J. Evidence for Persistent Heteroplasmy and Ancient Recombination in the Mitochondrial Genomes of the Edible Yellow Chanterelles from Southwestern China and Europe. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 699598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, M.D.; Rattray, A.M.J.; Gow, N.A.R.; Odds, F.C.; Shaw, D.J. Mitochondrial Haplotypes and Recombination in Candida albicans. Medical Mycology 2008, 46, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, J. Population Genomic Analyses Reveal Evidence for Limited Recombination in the Superbug Candida auris in Nature. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2022, 20, 3030–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, A.J.; Turner, G.; Croft, J.H.; Dales, R.B.G.; Lazarus, C.M.; Lünsdorf, H.; Küntzel, H. High Frequency Transfer of Species-Specific Mitochondrial DNA Sequences between Members of the Aspergillaceae. Curr Genet 1981, 3, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, R.T.; Turner, G. Three-Marker Extranuclear Mitochondrial Crosses in Aspergillus nidulans. Molec. Gen. Genet. 1975, 141, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, Z.; Tóth, B.; Beer, Z.; Gácser, A.; Kucsera, J.; Pfeiffer, I.; Juhász, Á.; Kevei, F. Interpretation of Intraspecific Variability in mtDNAs of Aspergillus niger Strains and Rearrangement of Their mtDNAs Following Mitochondrial Transmissions. FEMS Microbiology Letters 2003, 221, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nierman, W.C.; Pain, A.; Anderson, M.J.; Wortman, J.R.; Kim, H.S.; Arroyo, J.; Berriman, M.; Abe, K.; Archer, D.B.; Bermejo, C.; et al. Genomic Sequence of the Pathogenic and Allergenic Filamentous Fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Nature 2005, 438, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, M.; Zhu, Z.; Penka, M.; Helmschrott, C.; Wagener, N.; Wagener, J. Mitochondrial Dynamics in the Pathogenic Mold Aspergillus fumigatus: Therapeutic and Evolutionary Implications. Molecular Microbiology 2015, 98, 930–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Region | N | % | Private MLG | Total MLG | Region | N | % | Private MLG | Total MLG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 9 | 0.46% | 0 | 2 | Europe | 1036 | 53.43% | 20 | 56 |

| Cote d'Ivoire | 9 | 0.46% | 0 | 2 | Austria | 2 | 0.10% | 0 | 1 |

| Asia | 181 | 9.33% | 4 | 24 | Belgium | 10 | 0.52% | 0 | 5 |

| China | 10 | 0.52% | 0 | 4 | France | 161 | 8.30% | 3 | 26 |

| India | 12 | 0.62% | 1 | 3 | Germany | 262 | 13.51% | 7 | 30 |

| Iran | 2 | 0.10% | 2 | 2 | Ireland | 72 | 3.71% | 3 | 17 |

| Japan | 155 | 7.99% | 1 | 18 | Netherlands | 282 | 14.54% | 1 | 17 |

| Singapore | 1 | 0.05% | 0 | 1 | Portugal | 8 | 0.41% | 0 | 5 |

| Thailand | 1 | 0.05% | 0 | 1 | Spain | 28 | 1.44% | 4 | 14 |

| Oceania | 24 | 1.24% | 0 | 5 | Sweden | 1 | 0.05% | 0 | 1 |

| New Zealand | 24 | 1.24% | 0 | 5 | United Kingdom | 210 | 10.83% | 2 | 25 |

| North America | 573 | 29.55% | 13 | 39 | South America | 2 | 0.10% | 0 | 2 |

| Canada | 10 | 0.52% | 1 | 6 | Brazil | 1 | 0.05% | 0 | 1 |

| USA | 563 | 29.33% | 12 | 38 | Peru | 1 | 0.05% | 0 | 1 |

| Space | 2 | 0.10% | 0 | 2 | Unknown | 112 | 5.78% | 3 | 18 |

| ISS | 2 | 0.10% | 0 | 2 | Grand Total | 1939 | 100.00% | 40 | 79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).