Submitted:

12 September 2023

Posted:

14 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets

3.2. Convolutional Nets

- Simplified high-speed CNN called SimConvNet; defined below;

- The commonly used EfficientNetB3 [39].

2.3. Adversarial Attacks

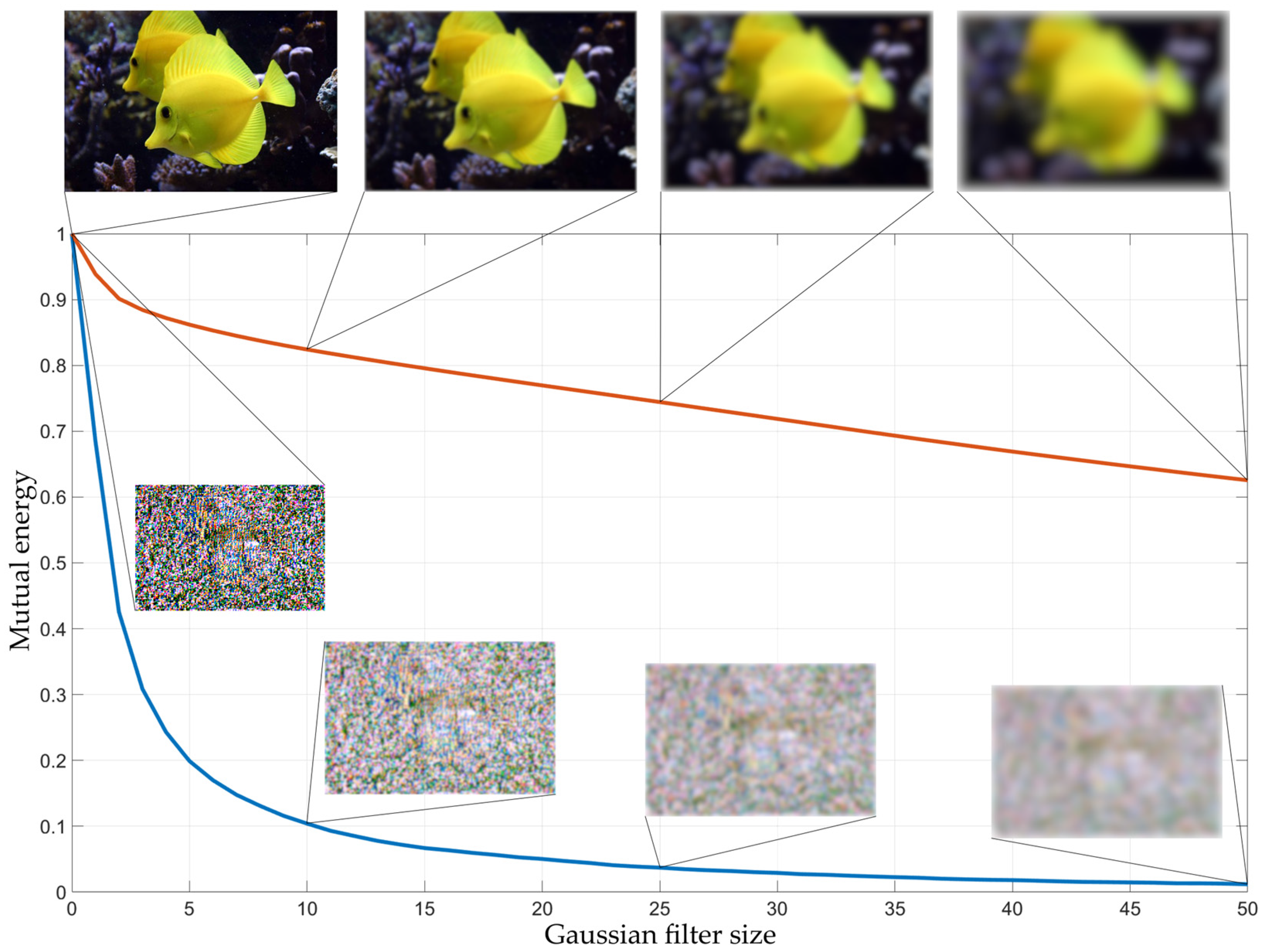

2.4. The theoretical approach to the problem solution

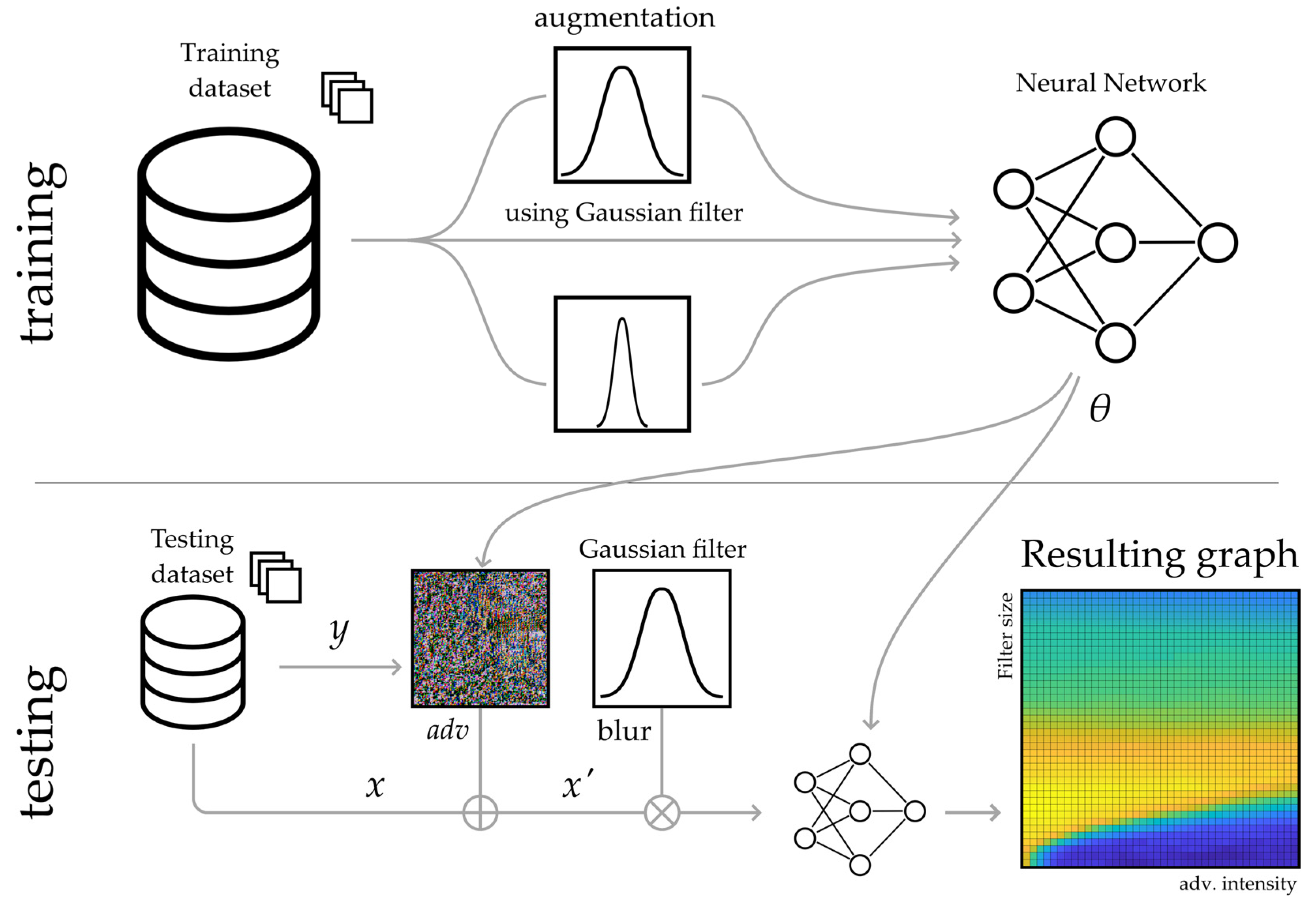

2.5. The proposed technique

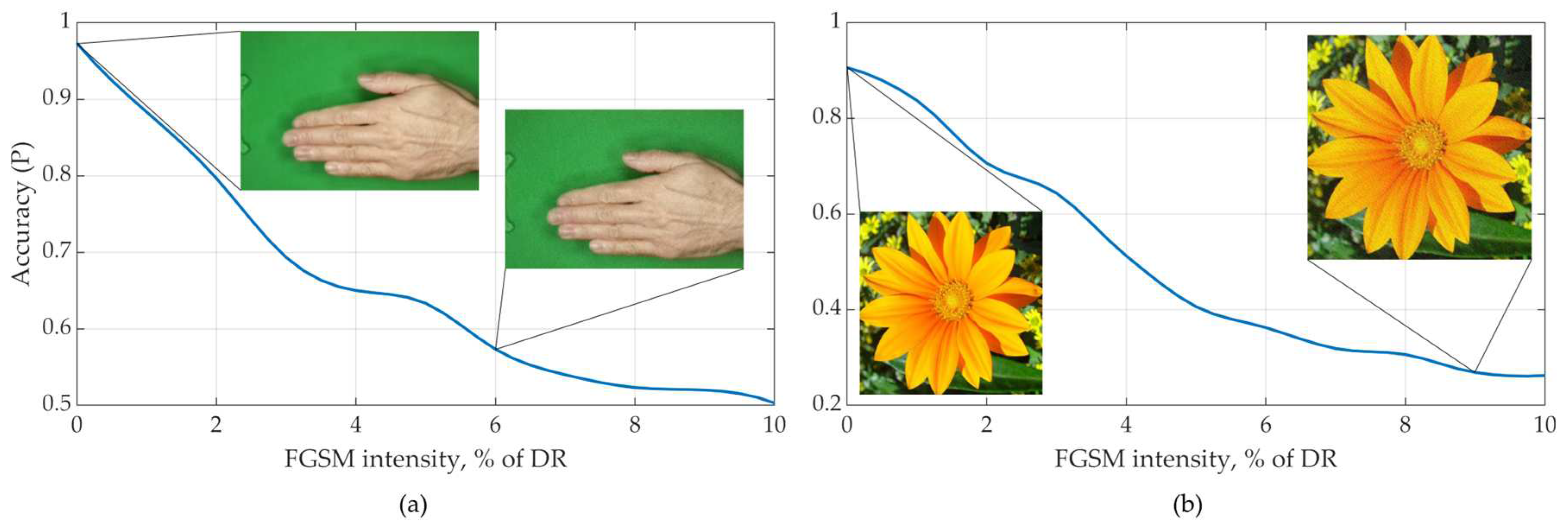

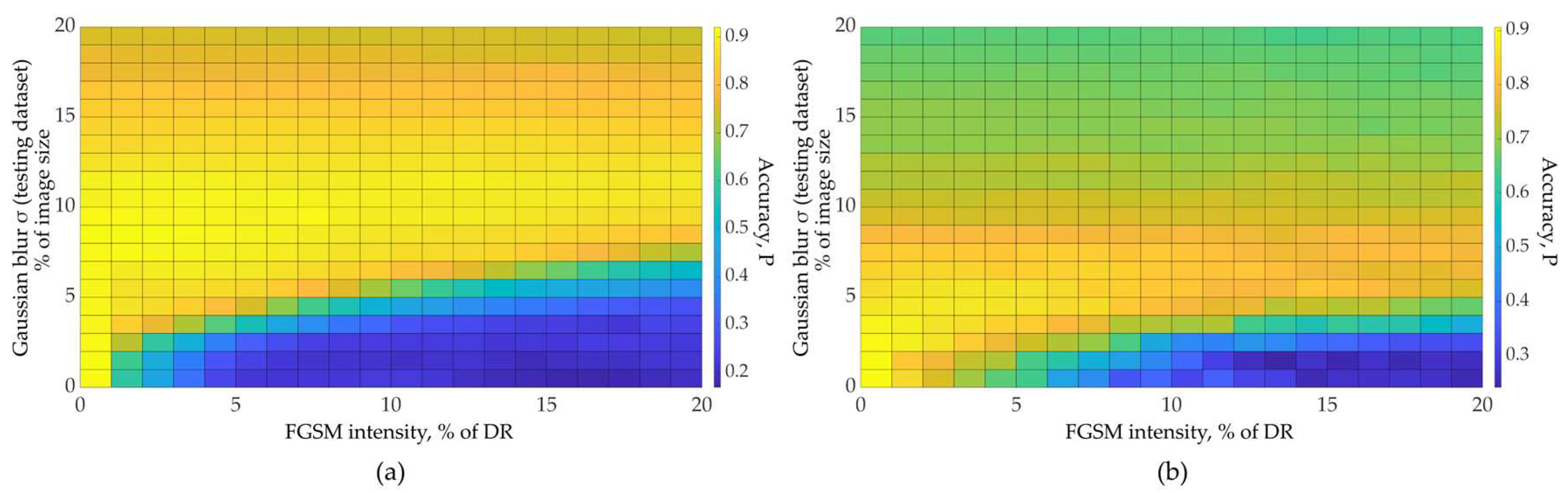

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ziyadinov, V.; Tereshonok, M. Noise Immunity and Robustness Study of Image Recognition Using a Convolutional Neural Network. Sensors 2022, 22, 1241. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22031241. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Lin, G.; Shen, C. CRF Learning with CNN Features for Image Segmentation. Pattern Recognition 2015, 48, 2983–2992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2015.04.019. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, R.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, L. Deep Location-Specific Tracking. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 25th ACM international conference on Multimedia; ACM: Mountain View California USA, October 19 2017; pp. 1309–1317.

- Ren, Y.; Yu, X.; Chen, J.; Li, T.H.; Li, G. Deep Image Spatial Transformation for Person Image Generation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Seattle, WA, USA, June 2020; pp. 7687–7696.

- Borji, A. Generated Faces in the Wild: Quantitative Comparison of Stable Diffusion, Midjourney and DALL-E 2. 2022. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2210.00586. [CrossRef]

- Jasim, H.A.; Ahmed, S.R.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Duru, A.D. Classify Bird Species Audio by Augment Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Congress on Human-Computer Interaction, Optimization and Robotic Applications (HORA); IEEE: Ankara, Turkey, June 9 2022; pp. 1–6.

- Mustaqeem; Kwon, S. A CNN-Assisted Enhanced Audio Signal Processing for Speech Emotion Recognition. Sensors 2019, 20, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20010183. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Erfani, S.M.; Gu, Q.; Bailey, J.; Ma, X. Exploring Architectural Ingredients of Adversarially Robust Deep Neural Networks. 2021. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2110.03825. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Chen, J.; Cai, D.; He, X.; Gu, Q. Do Wider Neural Networks Really Help Adversarial Robustness? 2020. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2010.01279. [CrossRef]

- Akrout, M. On the Adversarial Robustness of Neural Networks without Weight Transport. 2019. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1908.03560. [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Zaremba, W.; Sutskever, I.; Bruna, J.; Erhan, D.; Goodfellow, I.; Fergus, R. Intriguing Properties of Neural Networks 2014.

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples. 2014. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1412.6572. [CrossRef]

- Moosavi-Dezfooli, S.-M.; Fawzi, A.; Frossard, P. DeepFool: A Simple and Accurate Method to Fool Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Las Vegas, NV, USA, June 2016; pp. 2574–2582.

- Su, J.; Vargas, D.V.; Sakurai, K. One Pixel Attack for Fooling Deep Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Evol. Computat. 2019, 23, 828–841. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEVC.2019.2890858. [CrossRef]

- Papernot, N.; McDaniel, P.; Jha, S.; Fredrikson, M.; Celik, Z.B.; Swami, A. The Limitations of Deep Learning in Adversarial Settings. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P); IEEE: Saarbrucken, March 2016; pp. 372–387.

- Goodfellow, I.; Warde-Farley, D.; Mirza, M.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Maxout Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Machine Learning; Dasgupta, S., McAllester, D., Eds.; PMLR: Atlanta, Georgia, USA, June 17 2013; Vol. 28, pp. 1319–1327.

- Hu, Y.; Kuang, W.; Qin, Z.; Li, K.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Y.; Li, W.; Li, K. Artificial Intelligence Security: Threats and Countermeasures. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1145/3487890. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Alam, M.; Dey, V.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Mukhopadhyay, D. A Survey on Adversarial Attacks and Defences. CAAI Trans on Intel Tech 2021, 6, 25–45. https://doi.org/10.1049/cit2.12028. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Ma, Y.; Liu, H.-C.; Deb, D.; Liu, H.; Tang, J.-L.; Jain, A.K. Adversarial Attacks and Defenses in Images, Graphs and Text: A Review. Int. J. Autom. Comput. 2020, 17, 151–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11633-019-1211-x. [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, S.; Blitzer, J.; Crammer, K.; Pereira, F. Analysis of Representations for Domain Adaptation. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Schölkopf, B., Platt, J., Hoffman, T., Eds.; MIT Press, 2006; Vol. 19.

- Athalye, A.; Logan, E.; Andrew, I.; Kevin, K. Synthesizing Robust Adversarial Examples. PLMR 2018, 80, 284–293.

- Hendrycks, D.; Zhao, K.; Basart, S.; Steinhardt, J.; Song, D. Natural Adversarial Examples. 2019. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1907.07174. [CrossRef]

- Shaham, U.; Yamada, Y.; Negahban, S. Understanding Adversarial Training: Increasing Local Stability of Supervised Models through Robust Optimization. Neurocomputing 2018, 307, 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2018.04.027. [CrossRef]

- Samangouei, P.; Kabkab, M.; Chellappa, R. Defense-GAN: Protecting Classifiers Against Adversarial Attacks Using Generative Models 2018.

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. 2015. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1503.02531. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Evans, D.; Qi, Y. Feature Squeezing: Detecting Adversarial Examples in Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings 2018 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; 2018.

- Liao, F.; Liang, M.; Dong, Y.; Pang, T.; Hu, X.; Zhu, J. Defense Against Adversarial Attacks Using High-Level Representation Guided Denoiser. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); June 2018.

- Creswell, A.; Bharath, A.A. Denoising Adversarial Autoencoders. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learning Syst. 2019, 30, 968–984. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2018.2852738. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, N.; Maynor, J.; Gupta, B. Adversarial Machine Learning: Difficulties in Applying Machine Learning to Existing Cybersecurity Systems.; pp. 40–31.

- Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Jin, W.; Tang, J. Adversarial Attacks and Defenses: Frontiers, Advances and Practice. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; ACM: Virtual Event CA USA, August 23 2020; pp. 3541–3542.

- Rebuffi, S.-A.; Gowal, S.; Calian, D.A.; Stimberg, F.; Wiles, O.; Mann, T. Fixing Data Augmentation to Improve Adversarial Robustness 2021.

- Wang, D.; Jin, W.; Wu, Y.; Khan, A. Improving Global Adversarial Robustness Generalization With Adversarially Trained GAN 2021.

- Zhang, H.; Chen, H.; Song, Z.; Boning, D.; Dhillon, I.S.; Hsieh, C.-J. The Limitations of Adversarial Training and the Blind-Spot Attack 2019.

- Lee, H.; Kang, S.; Chung, K. Robust Data Augmentation Generative Adversarial Network for Object Detection. Sensors 2022, 23, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23010157. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Xu, J.; Zhao, D.; Shang, E.; Zhu, Q.; Dai, B. Adversarial and Random Transformations for Robust Domain Adaptation and Generalization. Sensors 2023, 23, 5273. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23115273. [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Xiong, K. Gaussian Filters for Nonlinear Filtering Problems. IEEE Trans. Automat. Contr. 2000, 45, 910–927. https://doi.org/10.1109/9.855552. [CrossRef]

- Blinchikoff, H.J.; Zverev, A.I. Filtering in the Time and Frequency Domains; Institution of Engineering and Technology, 2001; ISBN 978-1-884932-17-5.

- Ziyadinov, V.V.; Tereshonok, M.V. Neural Network Image Recognition Robustness with Different Augmentation Methods. In Proceedings of the 2022 Systems of Signal Synchronization, Generating and Processing in Telecommunications (SYNCHROINFO); IEEE: Arkhangelsk, Russian Federation, June 29 2022; pp. 1–4.

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning; Chaudhuri, K., Salakhutdinov, R., Eds.; PMLR, June 9 2019; Vol. 97, pp. 6105–6114.

- Krizhevsky, A. Learning Multiple Layers of Features from Tiny Images.; 2009.

- Roy, P.; Ghosh, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Pal, U. Effects of Degradations on Deep Neural Network Architectures 2023.

- Russakovsky, O.; Deng, J.; Su, H.; Krause, J.; Satheesh, S.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Karpathy, A.; Khosla, A.; Bernstein, M.; et al. ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. Int J Comput 2015, 115, 211–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-015-0816-y. [CrossRef]

- “Rock-Paper-Scissors Images | Kaggle.” URL: Https://Www.Kaggle.Com/Drgfreeman/Rockpaperscissors (Accessed Jun. 09, 2023).

- Madry, A.; Makelov, A.; Schmidt, L.; Tsipras, D.; Vladu, A. Towards Deep Learning Models Resistant to Adversarial Attacks. 2017. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1706.06083. [CrossRef]

- Tramèr, F.; Papernot, N.; Goodfellow, I.; Boneh, D.; McDaniel, P. The Space of Transferable Adversarial Examples 2017.

- Wang, J.; Yin, Z.; Hu, P.; Liu, A.; Tao, R.; Qin, H.; Liu, X.; Tao, D. Defensive Patches for Robust Recognition in the Physical World. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: New Orleans, LA, USA, June 2022; pp. 2446–2455.

- Andriushchenko, M.; Croce, F.; Flammarion, N.; Hein, M. Square Attack: A Query-Efficient Black-Box Adversarial Attack via Random Search. In Computer Vision – ECCV 2020; Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J.-M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; Vol. 12368, pp. 484–501 ISBN 978-3-030-58591-4.

- Carlini, N.; Wagner, D. Towards Evaluating the Robustness of Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); IEEE: San Jose, CA, USA, May 2017; pp. 39–57.

- Chen, P.-Y.; Zhang, H.; Sharma, Y.; Yi, J.; Hsieh, C.-J. ZOO: Zeroth Order Optimization Based Black-Box Attacks to Deep Neural Networks without Training Substitute Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 10th ACM Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Security; ACM: Dallas Texas USA, November 3 2017; pp. 15–26.

- Chen, J.; Jordan, M.I.; Wainwright, M.J. HopSkipJumpAttack: A Query-Efficient Decision-Based Attack. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); IEEE: San Francisco, CA, USA, May 2020; pp. 1277–1294.

- Wang, H.; Wu, X.; Huang, Z.; Xing, E.P. High-Frequency Component Helps Explain the Generalization of Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Seattle, WA, USA, June 2020; pp. 8681–8691.

- Bradley, A.; Skottun, B.C.; Ohzawa, I.; Sclar, G.; Freeman, R.D. Visual Orientation and Spatial Frequency Discrimination: A Comparison of Single Neurons and Behavior. Journal of Neurophysiology 1987, 57, 755–772. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.1987.57.3.755. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Hu, X.; Han, J.; Wang, L.; Duan, S. High Frequency Patterns Play a Key Role in the Generation of Adversarial Examples. Neurocomputing 2021, 459, 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2021.06.078. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jung, C.; Liang, X. Adversarial Defense by Suppressing High-Frequency Components 2019.

- Thang, D.D.; Matsui, T. Automated Detection System for Adversarial Examples with High-Frequency Noises Sieve. In Cyberspace Safety and Security; Vaidya, J., Zhang, X., Li, J., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; Vol. 11982, pp. 348–362 ISBN 978-3-030-37336-8.

- Ziyadinov, V.V.; Tereshonok, M.V.; Moscow Technical University of Communications and Informatics Mathematical Models And Recognition Methods For Mobile Subscribers Mutual Placement. T-Comm 2021, 15, 49–56. https://doi.org/10.36724/2072-8735-2021-15-4-49-56. [CrossRef]

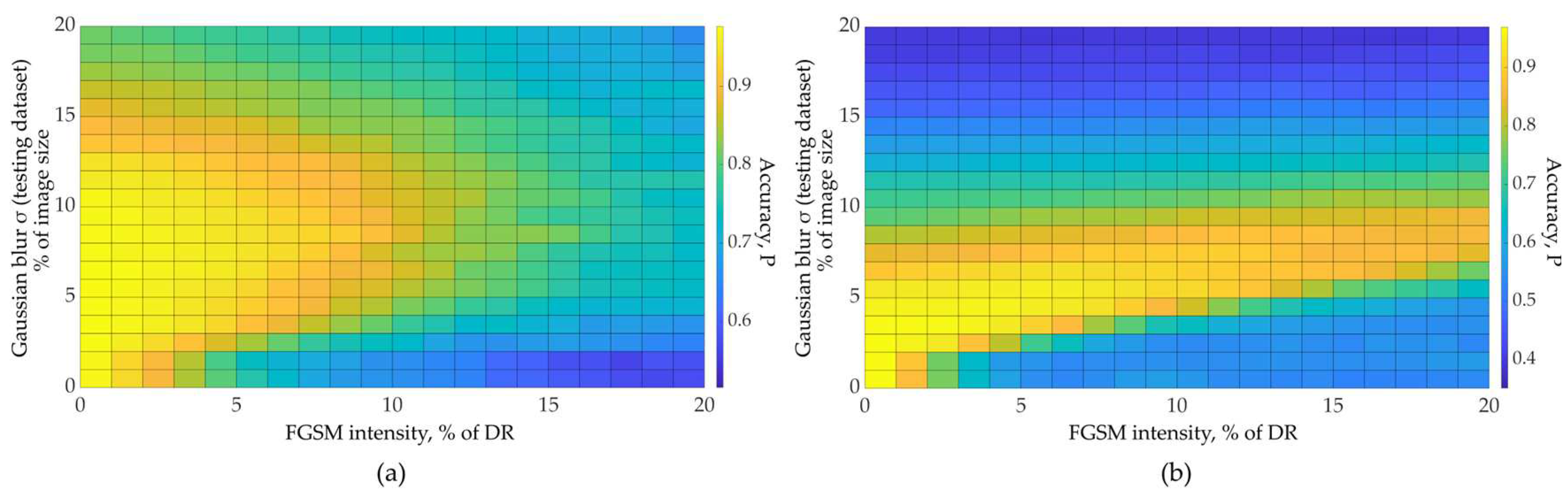

| FGSM intensity | FGSM intensity |

Optimal Low-pass filter size |

Accuracy gain G | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SimConvNet (Natural Dataset) |

5 | 0.206 | 0.913 | 10 | 9.1 |

| 10 | 0.206 | 0.9 | 7.9 | ||

| 20 | 0.1875 | 0.894 | 6.7 | ||

| SimConvNet (RPS) |

5 | 0.738 | 0.947 | 8 | 4.9 |

| 10 | 0.66 | 0.879 | 2.8 | ||

| 20 | 0.576 | 0.738 | 1.6 | ||

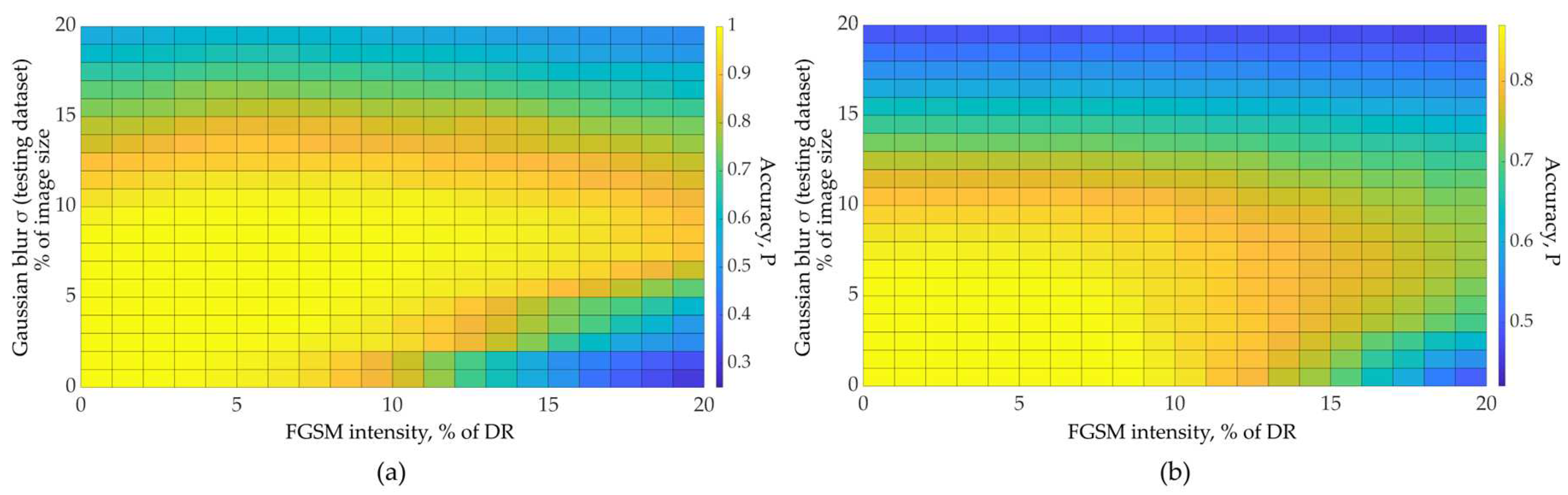

| EfficientNet (ImageNet) |

15 | 0.699 | 0.781 | 7 | 1.4 |

| 20 | 0.481 | 0.72 | 1.9 | ||

| EfficientNet (Natural Dataset) |

5 | 0.977 | 1 | 7 | ∞ |

| 10 | 0.814 | 0.996 | 46.5 | ||

| 20 | 0.25 | 0.881 | 6.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).