Submitted:

11 September 2023

Posted:

14 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

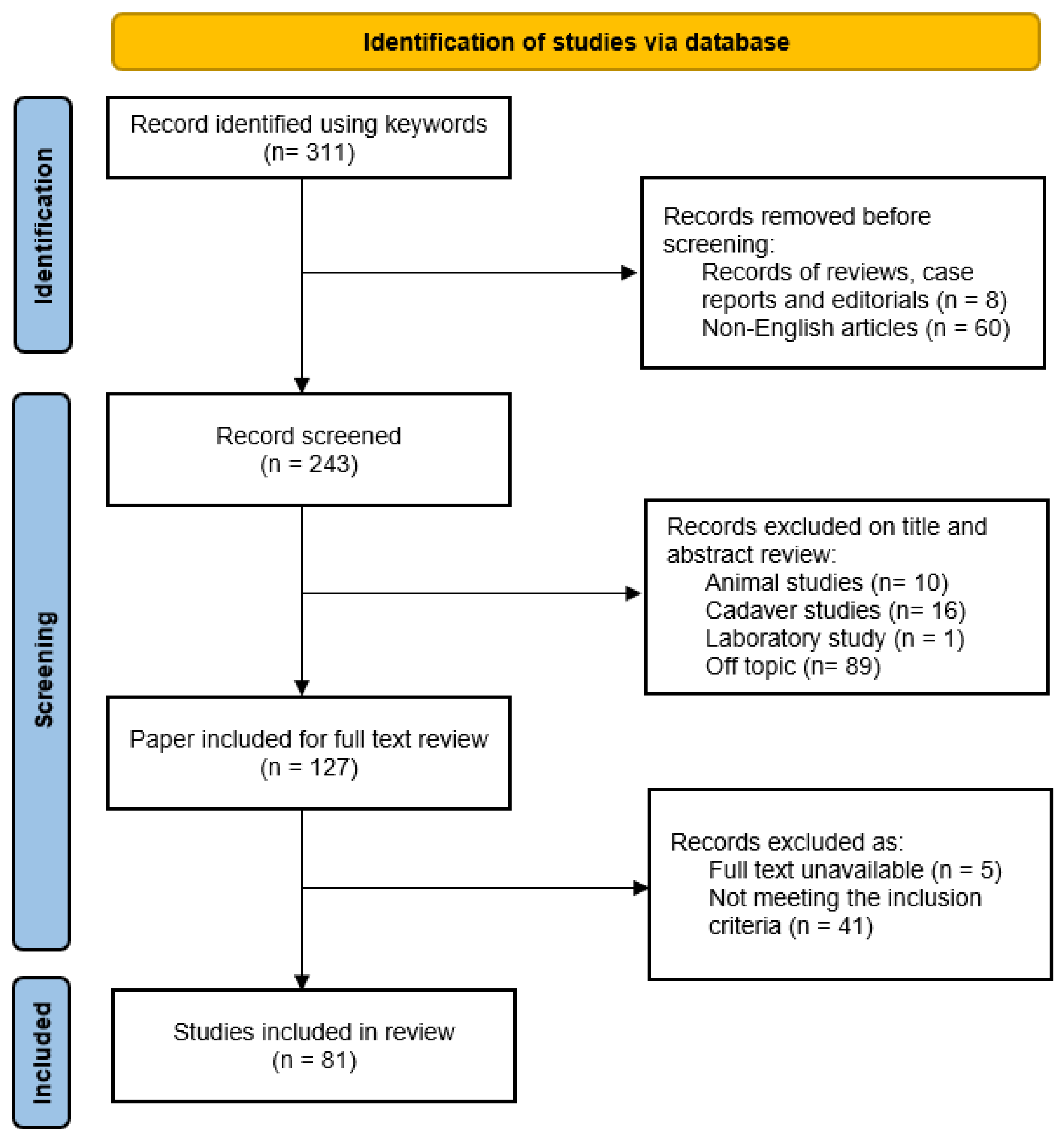

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Slade, K.; Plack, C.J.; Nuttall, H.E. The effects of age-related hearing loss on the brain and cognitive function. Trends Neurosci 2020, 43, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avan, P.; Giraudet, F.; Büki, B. Importance of binaural hearing. Audiol Neurootol 2015, 20 Suppl 1, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canzi, P.; Avato, I.; Beltrame, M.; Bianchin, G.; Perotti, M.; Tribi, L.; Gioia, B.; et al. Retrosigmoidal placement of an active transcutaneous bone conduction implant: surgical and audiological perspectives in a multicentre study. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2021, 41, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canzi, P.; Berrettini, S.; Albera, A.; Barbara, M.; Bruschini, L.; Canale, A.; Carlotto, E.; et al. Current trends on subtotal petrosectomy with cochlear implantation in recalcitrant chronic middle ear disorders. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2023, 43, S67–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potsangbam, D.S.; Akoijam, B.A. Endoscopic transcanal autologous cartilage ossiculoplasty. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019, 71, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beutner, D.; Hüttenbrink, K.B. Passive and active middle ear implants. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009, 8, Doc09. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kortebein, S.; Russomando, A.C.; Greda, D.; Cooper, M.; Ledbetter, L.; Kaylie, D. Ossicular chain reconstruction with titanium prostheses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otol Neurotol 2023, 44, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Song, J.; Wang, H. Results of tympanoplasty with titanium prostheses. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999, 121, 606–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalchow, C.V.; Grün, D.; Stupp, H.F. Reconstruction of the ossicular chain with titanium implants. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2001, 125, 628–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, W.W.; Feghali, J.G.; Shelton, C.; Green, J.D.; Beatty, C.W.; Wilson, D.F.; Thedinger, B.S.; Barrs, D.M.; McElveen, J.T. Preliminary ossiculoplasty results using the Kurz titanium prostheses. Otol Neurotol 2002, 23, 836–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, T.A.; Shelton, C. Ossicular chain reconstruction: titanium versus plastipore. Laryngoscope 2003, 113, 1731–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, S.Y.; Battista, R.A.; Wiet, R.J. Early results with titanium ossicular implants. Otol Neurotol 2003, 24, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, B.A.; Rizer, F.M.; Schuring, A.G.; Lippy, W.H. Tympano-ossiculoplasty utilizing the Spiggle and Theis titanium total ossicular replacement prosthesis. Laryngoscope 2003, 113, 1525–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, A.; Schultz-Coulon, H.J.; Jahnke, K. Type III tympanoplasty applying the palisade cartilage technique: A study of 61 cases. Otol Neurotol 2003, 24, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisch, U.; May, J.; Linder, T.; Naumann, I.C. A new L-shaped titanium prosthesis for total reconstruction of the ossicular chain. Otol Neurotol 2004, 25, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, E.K.; Jackson, C.G.; Kaylie, D.M. Results with titanium ossicular reconstruction prostheses. Laryngoscope 2004, 114, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.D.; Harner, S.G. Ossicular reconstruction with titanium prosthesis. Laryngoscope 2004, 114, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez-Colino, L.M.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M.; Alobid, I.; Traserra-Coderch, J. Preliminary functional results of tympanoplasty with titanium prostheses. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004, 131, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnerdt, G.; Van Delden, A.; Lautermann, J. Management of an “Ear Camp” for children in Namibia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2005, 69, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, C.; Gersdorff, M.; Gérard, J.M. Prognostic factors in ossiculoplasty. Otol Neurotol 2006, 28, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassbotn, F.S.; Møller, P.; Silvola, J. Short-term results using Kurz titanium ossicular implants. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2007, 264, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmerber, S.; Troussier, J.; Dumas, G.; Lavieille, J.P.; Nguyen, D.Q. Hearing results with the titanium ossicular replacement prostheses. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2006, 263, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hales, N.W.; Shakir, F.A.; Saunders, J.E. Titanium middle ear prostheses in staged ossiculoplasty: does mass really matter? Am J Otolaryngol 2007, 28, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiq, M.A.; Raut, V.V. Early results of titanium ossiculoplasty using the Kurz titanium prosthesis - A UK perspective. J Laryngol Otol 2007, 121, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truy, E.; Naiman, A.N.; Pavillon, C.; Abedipour, D.; Lina-Granade, G.; Rabilloud, M. Hydroxyapatite versus titanium ossiculoplasty. Otol Neurotol 2007, 28, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey CS, Lee F, Lambert PR. Titanium versus nontitanium prostheses in ossiculoplasty. Laryngoscope 2008, 118, 1650–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, P.; Fong, J.; Raut, V. Kurz titanium prostheses in paediatric ossiculoplasty- short term results. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2008, 72, 1329–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redaelli De Zinis, L.O. Titanium vs hydroxyapatite ossiculoplasty in canal wall down mastoidectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008, 134, 1283–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaani, A.; Raut, V.V. Alaani A, Raut V V. Kurz titanium prosthesis ossiculoplasty — Follow-up statistical analysis of factors affecting one year hearing results. Auris Nasus Larynx 2010, 37, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colletti, V.; Carner, M.; Colletti, L. TORP vs round window implant for hearing restoration of patients with extensive ossicular chain defect. Acta Otolaryngol 2009, 129, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, J.A.; Pandit, S.R.; Soma, M.; Kertesz, T.R. Ossicular chain reconstruction with a titanium prosthesis. J Laryngol Otol 2009, 123, 1082–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, O.; Fata, E.l.; Saliba, I. Ossicular reconstruction: incus versus universal titanium prosthesis. Auris Nasus Larynx 2009, 36, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, J.C.; Michael, P.; Raut, V. Titanium versus autograft ossiculoplasty. Acta Otolaryngol 2010, 130, 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñiguez-Cuadra, R.; Alobid, I.; Borés-Domenech, A.; Menéndez-Colino, L.M.; Caballero-Borrego, M.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M. Type III tympanoplasty with titanium total ossicular replacement prosthesis: anatomic and functional results. Otol Neurotol 2010, 31, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luers, J.C.; Huttenbrink, K.B.; Mickenhagen, A.; Beutner, D. A modified prosthesis head for middle ear titanium implants- experimental and first clinical results. Otol Neurotol 2010, 31, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praetorius, M.; Kirchenbauer, S.S.; Buss, S.; Klingmann, C.; Plinkert, P.K.; Baumann, I. First experiences with a new adjustable length titanium ossicular prosthesis (ALTO). Acta Otolaryngol 2010, 130, 1237–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesnel, S.; Teissier, N.; Viala, P.; Couloigner, V.; Van Den Abbeele, T. Long term results of ossiculoplasties with partial and total titanium Vario Kurz prostheses in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2010, 74, 1226–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yung, M.; Smith, P. Titanium versus nontitanium ossicular prostheses-a randomized controlled study of the medium-term outcome. Otol Neurotol 2010, 31, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babighian, G.; Albu, S. Stabilising total ossicular replacement prosthesis for ossiculoplasty with an absent malleus in canal wall down tympanomastoidectomy - a randomised controlled study. Clin Otolaryngol 2011, 36, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardassi, A.; Deveze, A.; Sanjuan, M.; Mancini, J.; Parikh, B.; Elbedeiwy, A.; Magnan, J.; Lavieille, J.P. Titanium ossicular chain replacement prostheses: prognostic factors and preliminary functional results. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2011, 128, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevoux, J.; Moya-Plana, A.; Chauvin, P.; Denoyelle, F.; Garabedian, E.N. Total ossiculoplasty in children: predictive factors and long-term follow-up. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2011, 137, 1240–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berenholz, L.P.; Burkey, J.M.; Lippy, W.H. Short- and long-term results of ossicular reconstruction using partial and total plastipore prostheses. Otol Neurotol 2013, 34, 884–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostian, A.O.; Pazen, D.; Luers, J.C.; Huttenbrink, K.B.; Beutner, D. Titanium ball joint total ossicular replacement prosthesis - Experimental evaluation and midterm clinical results. Hear Res 2013, 301, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess-Erga, J.; Møller, P.; Vassbotn, F.S. Long-term hearing result using Kurz titanium ossicular implants. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 2013, 270, 1817–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meulemans, J.; Wuyts, F.L.; Forton, G.E. Middle ear reconstruction using the titanium Kurz Variac partial ossicular replacement prosthesis: functional results. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013, 139, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.D.; Bradoo, R.A.; Joshi, A.A.; Sapkale, D.D. The efficiency of titanium middle ear prosthesis in ossicular chain reconstruction: our experience. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013, 65, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birk, S.; Brase, C.; Hornung, J. Experience with the use of a partial ossicular replacement prosthesis with a ball-and-socket joint between the plate and the shaft. Otol Neurotol 2014, 35, 1248–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayad, J.N.; Ursick, J.; Brackmann, D.E.; Friedman, R.A. Total ossiculoplasty: short- and long- term results using a titanium prosthesis with footplate shoe. Otol Neurotol 2014, 35, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Órfão, T.; Júlio, S.; Ramos, J.F.; Dias, C.C.; Silveira, H.; Santos, M. Audiometric outcome comparison between titanium prosthesis and molded autologous material. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014, 151, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, M.B.; Sunkaraneni, V.S.; Tann, N. Is cartilage interposition required for ossiculoplasty with titanium prostheses? Otol Neurotol 2014, 35, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.B.; O’Connell, B.P.; Nguyen, S.A.; Lambert, P.R. Ossiculoplasty with titanium prostheses in patients with intact stapes: comparison of TORP versus PORP. Otol Neurotol 2015, 36, 1676–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boleas-Aguirre, M.S.; Ruiz de Erenchun-Lasa, I.; Bulnes-Plano, M.D. Audiological results after total ossicular reconstruction for stapes fixation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2015, 272, 3123–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.I.; Yoo, S.H.; Lee, C.W.; Song, C.l.; Yoo, M.H.; Park, H.J. Short-term hearing results using ossicular replacement prostheses of hydroxyapatite versus titanium. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2015, 272, 2731–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocak, E.; Beton, S.; Meço, C.; Dursun, G. Titanium versus Hydroxyapatite prostheses: comparison of hearing and anatomical outcomes after ossicular chain reconstruction. Turk Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2015, 53, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, A.; Bakhos, D.; Villeneuve, A.; Hermann, R.; Suy, P.; Lescanne, E.; Truy, E. Does checking the placement of ossicular prostheses via the posterior tympanotomy improve hearing results after cholesteatoma surgery? Otol Neurotol 2015, 36, 1499–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter, N.E.; Holler, T.; Cushing, S.L.; Chadha, N.K.; Gordon, K.A.; James, A.L.; Papsin, B.C. Pediatric ossiculoplasty with titanium total ossicular replacement prosthesis. Laryngoscope 2015, 125, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramarzi M, Jahangiri R, Roosta S. Comparison of Titanium vs. Polycel total ossicular replacement prosthesis. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 28(2), 89–97.

- Gostian, A.O.; Kouame, J.M.; Bremke, M.; Ortmann, M.; Hüttenbrink, K.B.; Beutner, D. Long term results of the titanium clip prosthesis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2016, 273, 4257–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gostian, A.O.; Kouamé, J.M.; Bremke, M.; Ortmann, M.; Hüttenbrink, K.B.; Beutner, D. Long-term results of the cartilage shoe technique to anchor a titanium total ossicular replacement prosthesis on the stapes footplate after type III tympanoplasty. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016, 142, 1094–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, B.P.; Rizk, H.G.; Hutchinson, T.; Nguyen, S.A.; Lambert, P.R. Long-term outcomes of titanium ossiculoplasty in chronic otitis media. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016, 154, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amith N, RS M. Autologous incus versus titanium partial ossicular replacement prosthesis in reconstruction of Austin type A ossicular defects: A prospective randomised clinical trial. J Laryngol Otol 2017, 131, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govil, N.; Kaffenberger, T.M.; Shaffer, A.D.; Chi, D.H. Factors influencing hearing outcomes in pediatric patients undergoing ossicular chain reconstruction. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2017, 99, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMullen, K.P.; Harris, M.S.; Dodson, E.E. Use of 2-Octyl cyanoacrylate in cartilage Interposition adherence during ossiculoplasty. Laryngoscope 2017, 127, 731–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulazimoglu, S.; Saxby, A.; Schlegel, C.; Linder, T. Titanium incus interposition ossiculoplasty: audiological outcomes and extrusion rates. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2017, 274, 3303–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.S.; Shin, S.O. Results of hearing outcome according to the alloplastic ossicular prosthesis materials. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2018, 70, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahue, C.N.; O’Connnell, B.P.; Dedmon, M.M.; Haynes, D.S.; Rivas, A. Short and Long-Term Outcomes of Titanium Clip Ossiculoplasty. Otol Neurotol 2018, 39, e453–e460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Jeong, C.; Shim, M.; Kim, W.; Yeo, S.; Park, S. Comparative study of new autologous material, bone-cartilage composite graft, for ossiculoplasty with Polycel® and Titanium. Clin Otolaryngol 2018, 43, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Yadav, K.; Ojha, T.; Sharma, A.; Singhal, A.; Gakhar, S. To evaluate and compare the result of ossiculoplasty using different types of graft materials and prosthesis in cases of ossicular discontinuity in chronic suppurative otitis media cases. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2018, 70, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahlou, G.; Sonji, G.; De Seta, D.; Mosnier, I.; Russo, F.Y.; Sterkers, O.; Bernardeschi, D. Anatomical and functional results of ossiculoplasty using titanium prosthesis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2018, 38, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba I, Sabbah V, Poirier JB. Total ossicular replacement prosthesis: a new fat interposition technique. Clin Med Insights Ear Nose Throat 2018, 11, 117955061774961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.M.; Chi, F.L. Titanium ossicular chain reconstruction in single stage canal wall down tympanoplasty for chronic otitis media with mucosa defect. Am J Otolaryngol 2019, 40, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haidar, H; Abu Rajab Altamimi, Z. ; Larem, A.; Aslam, W.; Elsaadi, A.; Abdulkarim, H.; Al Duhirat, E.; et al. The benefit of trans-attic endoscopic control of ossicular prosthesis after cholesteatoma surgery. Laryngoscope 2019, 129, 2754–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.B. , Yawn, R.; Lowery, A.S.; O’Connell, B.P.; Haynes, D.; Wanna, G.B. Long-term hearing outcomes following total ossicular reconstruction with titanium prostheses. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019, 161, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantsopoulos, K.; Thimsen. V.; Taha, L.; Eisenhut, F.; Müller, S.K.; Sievert, M.; Iro, H.; Hornung, J. Comparative analysis of titanium clip prostheses for partial ossiculoplasty. Am J Otolaryngol 2021, 42, 103062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baazil AHA, Ebbens FA, Van Spronsen E, De Wolf MJF, Dikkers FG. Comparison of long-term microscopic and endoscopic audiologic results after total ossicular replacement prosthesis surgery. Otol Neurotol 2022, 43, 1189–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmad F, Perdigão AG. Titanium prostheses versus stapes columella type 3 tympanoplasty: a comparative prospective study. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2022, 88, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, E.M.; Russell, G.B.; Allen, S.J.; Pearson, S.A. Long-term hearing results of endoskeletal ossicular reconstruction in chronic ears using titanium prostheses having a helical coil: Part 1 - Kraus K-Helix Crown, incus to stapes. Otol Neurotol 2022, 43, 1056–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lim, K.H.; Lim, S.J.; Park, D.H.; Rah, Y.C.; Choi, J. Functional outcomes of single-stage ossiculoplasty in chronic otitis media with or without cholesteatoma. J Int Adv Otol 2022, 18, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plichta, L.; Dabkowska, A.; Wawszczyk-Frohlich, S.; Skarzynski, H.; Skarzynski, P.H. Titanium prostheses for treating posttraumatic ossicular chain disruption. J Int Adv Otol 2022, 18, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoolst, A.; Wuyts, F.L.; Forton, G.E.J. Total ossicular chain reconstruction using a titanium prosthesis: functional results. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2022, 279, 5615–5621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, C.; Tai, S.; Chan, L.P.; Wang, H.M.; Chang, N.C.; Wang, L.F.; Ho, K.Y.; Li, K.H. Predictive factors and audiometric outcome comparison between titanium prosthesis and autologous incus in traumatic ossicular injury. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2023, 34894231181746, Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramarzi, M.; Roosta, S.; Faramarzi, A.; Kherad, M. Comparison of partial vs. total ossicular chain reconstruction using titanium prosthesis: a retrospective cohort study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2023, 280, 3567–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gülşen S, Çıkrıkcı S. A novel technique in treatment of advanced tympanosclerosis: results of malleus replacement and loop prostheses combination; pure endoscopic transcanal approach. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2023, 280, 3601–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kálmán, J.; Horváth, T.; Dános, K.; Tamás, L.; Polony, G. Primary ossiculoplasties provide better hearing results than revisions: a retrospective cohort study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2023, 280, 3177–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Ha, J.; Choo, O.S.; Park, H.; Choung, Y.H. Which is better for ossiculoplasty following tympanomastoidectomy: Polycel® or Titanium? Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2023, 23, 34894231159969, Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, A.; Benatti, A.; Velardita, C.; Favaro, D.; Padoan, E.; Severi, D.; Pagliaro, M.; et al. Aging, cognitive decline and hearing loss: effects of auditory rehabilitation and training with hearing aids and cochlear implants on cognitive function and depression among older adults. Audiol Neurootol 2016, 21 Suppl 1, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bönitz, H.; Lunner, T.; Finke, M.; Fiedler, L.; Lyxell, B.; Riis, S.K.; Ng, E.; et al. How do we allocate our resources when listening and memorizing speech in noise? A pupillometry study. Ear Hear 2021, 42, 846–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.D.; Driscoll, C.L.W.; Wood, C.P.; Felmlee, J.P. Safety evaluation of titanium middle ear prostheses at 3.0 tesla. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005, 132, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danti, S.; Stefanini, C.; D’Alessandro, D.; Moscato, S.; Pietrabissa, A.; Petrini, M.; Berrettini, S. Novel biological/biohybrid prostheses for the ossicular chain: fabrication feasibility and preliminary functional characterization. Biomed Microdevices 2009, 11, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanna, M.; Hiroshi, S.; Mancini, F.; Russo, A.; Taibah, A.; Falcioni, M. Middle ear and mastoid microsurgery; Thieme: Stuttgart, Germany, 2018; pp. 187–244. [Google Scholar]

| Authors, year | Pts | Ears | PORP | TORP | Age at surgery (range) | Middle ear disorder |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. 1999[8] | 113 | 124 | 86 | 38 | n.a. | 59 CCOM, 54 COM, 2 CA, 9 TS |

| Dalchow et al. 2001[9] | 1304 | 1304 | 647 | 657 | 5- 82y | 1304 COM + CCOM |

| Krueger et al. 2002[10] | 31 | 31 | 16 | 15 | n.a. | 31 CCOM + COM |

| Hillman and Shelton. 2003[11] | 53 | 53 | 30 | 23 | 34.8y | n.a. |

| Ho et al. 2003[12] | 25 | 25 | 14 | 11 | 45y (14–74) | 15 CCOM, 6 COM, 4 CA |

| Neff et al. 2003[13] | 18 | 18 | 0 | 18 | 37y (8 - 80) | 11 CCOM, 7 COM+TS |

| Neumann et al. 2003[14] | 59 | 61 | 27 | 34 | 36y (7-81) | 32 CCOM, 11 COM, 16 AT, 2 TS |

| Fisch et al. 2004[15] | 46 | 46 | 0 | 46 | 44.8y (22-65) | 19 CCOM, 20 COM, 7 CA + TR |

| Gardner et al. 2004[16] | 149 | 149 | 111 | 38 | 32.5 y (3-75) | 77 CCOM, 40 COM, 32 n.a. |

| Martin et al. 2004[17] | 68 | 68 | 30 | 38 | 39y (6-74) | 68 CCOM+ COM |

| Menéndez-Colino et al. 2004[18] | 23 | 23 | 0 | 23 | 37y (8-65) | 17 CCOM, 3 COM, 1 AT, 2 CA |

| Lehnerdt et al. 2005[19] | 15 | 15 | 14 | 1 | 12y (n.a.) | 15 CCOM + COM |

| De Vos et al. 2006[20] | 129 | 140 | 65 | 75 | 37y (3-73) | 72 CCOM, 12 COM, 17 AT, 16 TS, 23 n.a. |

| Vassbotn et al. 2006[21] | 71 | 73 | 38 | 35 | 31.5 y | 40 CCOM, 4 COM. 29 CA |

| Schmerber et al. 2006[22] | 111 | 111 | 61 | 50 | 38.4 y (7 – 76) | 82 CCOM, 16 COM, 4 AT, 5 CA, 1 OTO, 3 TR |

| Hales et al. 2007[23] | 34 | 34 | 24 | 10 | 26y (4-59) | 29 CCOM, 5 n.a. |

| Siddiq and Raut. 2007[24] | 33 | 33 | 20 | 13 | 35.9 y (7 - 64) | 15 CCOM, 18 COM |

| Truy et al. 2007[25] | 62 | 62 | 27 | 35 | 37.5y (n.a.) | 38 CCOM, 24 n.a. |

| Coffey et al. 2008[26] | 80 | 80 | 29 | 51 | 28.8y (n.a.) | 35 CCOM, 36 COM, 3 CA, 4 OTO, 2 TR |

| Michael et al. 2008[27] | 14 | 14 | 9 | 5 | 11y (7-14) | 6 CCOM, 4 COM, 3 AT, 1 n.a. |

| Redaelli de Zinis. 2008[28] | 26 | 26 | 12. | 14. | 49y (17-78) | 26 CCOM |

| Alaani and Raut. 2009[29] | 97 | 97 | 65 | 32 | 39.6 y (5 –75) | 40 CCOM, 10 COM, 38 AT, 9 n.a. |

| Colletti et al. 2009[30] | 19 | 19 | 0 | 19 | 50 y (19 - 76) | 19 COM |

| Roth et al. 2009[31] | 54 | 54 | 32 | 22 | 34y (6-74) | 36 CCOM, 9 COM, 4 CA, 5 TR |

| Woods et al. 2009[32] | 70 | 70 | 40 | 30 | 34.1y (11-76) | 33 CCOM, 12 COM, 10 AT, 15 n.a. |

| Fong et al. 2010[33] | 51 | 51 | 34 | 17 | 38 y (7 – 69) | 20 CCOM, 31 COM |

| Inũiguez-Cuadra et al. 2010[34] | 85 | 94 | 0 | 94 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Luers et al. 2010[35] | 70 | 70 | 0 | 70 | 43.6y (6-66) | 40 CCOM, 30 COM |

| Praetorius et al. 2010[36] | 14 | 14 | 14 | 0 | 50.4y (13–74) | 14 CCOM |

| Quesnel et al. 2010[37] | 74 | 74 | 27 | 47 | 11.3y (n.a.) | n.a. |

| Yung and Smith. 2010[38] | 49 | 49 | 19 | 30 | 44y (n.a.) | 14 CCOM, 35 COM |

| Babighian and Albu. 2011[39] | 125 | 125 | 0 | 125 | 43.7 (n.a.) | 125 CCOM |

| Beutner et al. 2011[6] | 18 | 18 | 18 | 0 | 44.4y (8-69) | 12 CCOM, 6 COM |

| Quaranta et al. 2011[37] | 57 | 57 | 19 | 38 | 38 y (6 – 67) | 57 CCOM |

| Mardassi et al. 2011[40] | 70 | 70 | 37 | 33 | 43y (5-77) | 47 CCOM, 23 COM |

| Nevoux et al. 2011[41] | 114 | 116 | 0 | 116 | 9.8y (n.a) | 116 CCOM |

| Berenholz et al. 2013[42] | 152 | 152 | 84 | 68 | 47.3y (n.a.) | 92 CCOM, 56 COM, 4 n.a. |

| Gostian et al. 2013[43] | 12 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 42y (9 - 73) | 8 CCOM, 4 COM |

| Hess-Erga et al. 2013[44] | 76 | 76 | 44 | 32 | 33y (6-78) | 40 CCOM, 5 COM, 31 TR |

| Meulemans et al 2013[45] | 83 | 89 | 89 | 0 | n.a. (7-85) | 51 CCOM, 21 COM, 17 n.a. |

| Shah et al. 2013[46] | 19 | 19 | 15 | 4 | 14–50y (n.a.) | 19 CCOM + COM |

| Birk et al. 2014[47] | 60 | 62 | 62 | 0 | 38y (4 - 83) | n.a. |

| Fayad et al. 2014[48] | 62 | 62 | 0 | 62 | 38.4y (3 - 82) | 60 COM, 2 n.a. |

| Órfão et al. 2014[49] | 43 | 43 | 26 | 17 | 39y (7- 70) | 14 CCOM, 17 COM, 12 n.a. |

| Pringle et al. 2014[50] | 73 | 73 | 36 | 37 | 32.9y (6 - 64) | n.a. |

| Baker et al. 2015[51] | 79 | 83 | 56 | 27 | 37.3y (6–79) | 74 CCOM+ COM, 9 n.a. |

| Boleas-Aguirre et al. 2015[52] | 16 | 16 | 0 | 16 | 56y (57–40) | 8 CCOM+COM, 5 TS, 3 OTO |

| Lee et al. 2015[53] | 27 | 27 | 18 | 9 | 54y (14 - 76) | 17 CCOM, 10 COM |

| Ocak et al. 2015[54] | 18 | 18 | 8 | 10 | 35.2y (13 - 57) | 18 CCOM+ COM |

| Roux et al. 2015[55] | 68 | 68 | 32 | 36 | 34.5y (13-56) | 68 CCOM |

| Wolter et al. 2015[56] | 71 | 75 | 0 | 75 | 14.3 y (7 - 18) | 66 CCOM, 2 CA, 7 n.a. |

| Faramarzi et al. 2016[57] | 45 | 45 | 0 | 45 | n.a. | 10 CCOM, 3 COM, 11 TS, 21 n.a. |

| Gostian et al. 2016[58] | 47 | 47 | 47 | 0 | 43y (7–73) | 17 CCOM, 30 COM |

| Gostian et al. 2016[59] | 42 | 42 | 0 | 42 | 42.8y (6-78) | 26 CCOM, 16 COM |

| O’Connell et al. 2016[60] | 149 | 149 | 56 | 93 | 30.1y (n.a.) | 80 CCOM, 69 COM |

| Amith and Rs. 2017[61] | 20 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 25 y (12 - 52) | 10 CCOM, 10 COM |

| Govil et al. 2017[62] | 101 | 101 | 47 | 54 | 9.8y (3.4-17.3) | n.a. |

| McMullen et al. 2017[63] | 71 | 71 | 23 | 48 | 26y (6-73) | n.a. |

| Mulazimoglu et al. 2017[64] | 126 | 126 | 126 | 0 | 37 y (7 –72) | 86 CCOM, 11 COM, 13 CHL, 11 TR, 3 TS, 2 TU |

| Choi and Shin. 2018[65] | 45 | 45 | 20 | 25 | n.a. | 45 CCOM + COM |

| Kahue et al. 2018[66] | 130 | 130 | 130 | 0 | 36 y (n.a.) | 121 COM, 9 TR |

| Kong et al. 2017[67] | 20 | 20 | 9 | 11 | 49 y (n.a.) | n.a. |

| Kumar et al. 2017[68] | 37 | 37 | 31 | 6 | 31.6 y (13-48) | 37 CCOM+ COM |

| Lahlou et al. 2018[69] | 256 | 280 | 163 | 117 | 44y (17 - 74) | 125 CCOM, 85 COM, 40 AT, 4 CA, 11 OTO, 12 TR, 3 TU |

| Saliba et al. 2018[70] | 158 | 158 | 0 | 158 | 29.7y (n.a.) | 103 CCOM, 25 COM, 19 CA, 11 n.a. |

| Gu and Chi. 2019[71] | 206 | 206 | 134 | 72 | 46y (12-70) | 206 CCOM + COM |

| Haidar et al. 2019[72] | 129 | 133 | 88 | 45 | 33 y (7 – 74) | 34 COM, 10 AT, 24 GR, 65 n.a. |

| Potsangbam and Akoijam. 2019[5] | 20 | 20 | 14 | 6 | 30y (8 - 64) | 20 CCOM |

| Wood et al. 2019[73] | 153 | 153 | 0 | 153 | 40y (6-89) | 120 CCOM, 10 COM, 23 n.a. |

| Mantsopoulos et al. 2021[74] | 274 | 274 | 274 | 0 | 38 y (6 – 67) | 168 CCOM, 62 COM, 37 TS, 6 TR, 1 TU |

| Baazil et al. 2022[75] | 106 | 106 | 0 | 106 | 35y (6.6–75.3) | 105 CCOM+ COM, 1 CA |

| Bahmad and Perdigão. 2022[76] | 13 | 13 | 0 | 13 | 44y (n.a.) | 7 CCOM, 6 COM |

| Kraus et al. 2022[77] | 36 | 38 | 38 | 0 | 40.4y (6-81) | 18 CCOM, 20 COM |

| Park et al. 2022[78] | 135 | 135 | 86 | 49 | n.a. | 94 CCOM, 41 COM |

| Plichta et al. 2022[79] | 24 | 24 | 12 | 12 | 38.33 y (4-62) | 24 TR |

| Van Hoolst et al. 2022[80] | 99 | 113 | 0 | 113 | n.a. (8 - 87) | 74 CCOM, 15 COM, 24 CA |

| Chien et al. 2023[81] | 8 | 8 | 8 | 0 | n.a. (27-48) | 8 TR |

| Faramarzi et al. 2023[82] | 248 | 248 | 115 | 133 | 33 y (n.a.) | 248 CCOM+COM+TS |

| Gülşen and Çıkrıkcı. 2023[83] | 21 | 21 | 0 | 21 | n.a. (28-44) | 21 TS |

| Kálmán et al. 2023[84] | 130 | 130 | 84 | 46 | n.a. | 130 CCOM+ COM |

| Kim et al. 2023[85] | 130 | 130 | 78 | 52 | 49.2y (n.a.) | 71 CCOM, 59 COM |

| Authors, year | Surgery | Staging | Pre-op ABG | Post-op ABG | Extrusions and dislocations/ears (%) | Onset | Treatment | Follow-up | ||

| PORP | TORP | PORP | TORP | |||||||

| Wang et al. 1999[8] | 11 CWD, 48 CWU, 65 OPL | 0 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 2/124 (1.6%) | n.a. | n.a. | 12-46 mo |

| Dalchow et al. 2001[9] | n.a. | 1100 | n.a. | n.a. | 14 | 15 | 29/1304 (2.2%) | n.a. | n.a. | 6-72 mo |

| Krueger et al. 2002[10] | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 14.1 | n.a. | 0/31 (0%) | / | / | 16 mo - 2 y |

| Hillman and Shelton. 2003[11] | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 2/53 (3.8%) | 12 mo | surgical | 3mo- n.a. |

| Ho et al. 2003[12] | 9 CDW, 15 CWU, 1 OPL | 20 | 38.7 | 42.8 | 18.1 | 21.5 | 1/25 (4%) | n.a. | surgical | 6 mo |

| Neff et al. 2003[13] | 16 OPL, 2 n.a. | 6 | n.a. | 33.9 | n.a. | 16.9 | 0/ 18 (0%) | / | / | 8 mo |

| Neumann et al. 2003[14] | n.a. | 0 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 0/61 (0%) | / | / | 38 mo |

| Fisch et al. 2004[15] | 21 CWD, 25 CWU | 46 | / | 41.9 | / | 20.7 | 0/46 (0%) | / | / | 1-7 y |

| Gardner et al. 2004[16] | 13 CWD,68 CWU, 21 OPL, 47 n.a. | 13 | 26 | 40 | 18.8 | 21.7 | 1/149 (0.7%) | n.a. | n.a. | 1.5y |

| Martin et al. 2004[17] | 14 CWD, 7 CWU, 47 OPL | 4 | 34 | 34 | 17 | 25 | 1/68 (1.5%) | n.a. | surgical | 3 mo- 2.5y |

| Menéndez-Colino et al. 2004[18] | 16 CWD, 7 CWU | 0 | / | n.a. | / | n.a. | 0/23 (0%) | / | / | 18 mo |

| Lehnerdt et al. 2005[19] | n.a. | 0 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 1/15 (6.6%) | n.a. | n.a. | 6 mo |

| De Vos et al. 2006[20] | 8 CWD, 65 CWU, 67 OPL | 24 | 32.7 | 42.5 | 18.1 | 19.8 | 11/140 (7.9%) | 22 mo | surgical | 11.8 mo |

| Vassbotn et al. 2006[21] | 20 CWD, 53 CWU | 0 | 28 | 38 | 9 | 19 | 4/73 (5.5%) | n.a. | 2 surgical, 2 n.a. | 14.2 mo |

| Schmerber et al. 2006[22] | 18 CWD, 93 CWU | 65 | n.a. | n.a. | 15 | 26.5 | 14/111 (12.6%) | 1: 17 mo, 1: 20 mo, 12 n.a. | 13 surgical, 1 refused | 20.5 mo |

| Hales et al. 2007[23] | 4 CWD, 30 CWU | 34 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 2/34 (5.9%) | n.a. | n.a. | 19 mo |

| Siddiq and Raut. 2007[24] | 5 CWD, 14 CWU, 14 n.a. | n.a. | 25.1 | 23.3 | 15.3 | 13.4 | 0/33 (0%) | / | / | 6 - 18 mo |

| Truy et al. 2007[25] | n.a. | n.a. | 30.9 | 28 | 19.4 | 18.3 | 2/62 (3.2%) | 2 mo | surgical | 12 mo |

| Coffey et al. 2008[26] | 22 CDW, 22 CWU, 30 OPL | 34 | n.a. | n.a. | 14.3 | 16.0 | 3/80 (3.8%) | n.a. | n.a. | 14.9 mo |

| Michael et al. 2008[27] | 7 CWD, 3 CWU, 4 OPL | 7 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 0/7 (0%) | / | / | 12 mo |

| Redaelli de Zinis. 2008[28] | 26 CWD | 0 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 0/ 14 (0%) | / | / | 12 mo |

| Alaani and Raut. 2009[29] | 57 CWD, 40 CWU+ OPL | 29 | 26.3 | 32.1 | 10.6 | 14.8 | 2/97 (2.1%) | 1 y | 1 surgical, 1 n.a. | 1 y |

| Colletti et al. 2009[30] | 19 CWU | n.a. | / | 40.7 | / | 21.5 | 3/19 (15.8%) | n.a. | 2 surgical, 1 n.a. | 36 mo |

| Roth et al. 2009[31] | 11 CWD, 27 CWU, 16 OPL | 29 | 31.0 | 38.2 | 13.3 | 16.4 | 1/54 (1.8%) | / | surgical | 1-5 y |

| Woods et al. 2009[32] | n.a. | 3 | 32.2 | 39.2 | 26.9 | 29.2 | 11/70 (15.7%) | n.a. | n.a. | 6 mo |

| Fong et al. 2010[33] | 4 CWD, 47 CWU | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 1/51 (2%) | n.a. | n.a. | 12 mo |

| Inũiguez-Cuadra et al. 2010[34] | 56 CWD, 38 CWU | n.a. | / | 23.8 | / | 15.4 | 8/94 (8.5%) | n.a. | n.a. | 38 mo |

| Luers et al. 2010[35] | 33 CWD, 37 CWU | 0 | / | 33.9 | / | 19.7 | 0/70 (0%) | / | / | 2 mo |

| Praetorius et al. 2010[36] | n.a. | n.a. | 26.6 | / | 15.2 | / | 0/14 (0%) | / | / | 8 mo |

| Quesnel et al. 2010[37] | n.a. | 49 | 30.2 | 36.6 | 20.8 | 22 | 5/74 (6.8%) | n.a. | n.a. | 33 mo |

| Yung and Smith. 2010[38] | n.a. | 7 | 29.2 | 32.5 | 16.2 | 20.7 | 8/49 (16.3%) | n.a. | n.a. | 2y |

| Babighian and Albu. 2011[39] | 125 CWD | 125 | / | 44.9 | / | 22.3 | 2/125 (1.6%) | n.a. | n.a. | 12 mo |

| Beutner et al. 2011[6] | 11 CWD, 7 CWU | 0 | 26.8 | / | 18.2 | / | 0/18 (0%) | / | / | 6 mo |

| Quaranta et al. 2011[37] | 57 CWU | 57 | 36.7 | 45.3 | 24.1 | 27.2 | 6/57 (10.5%) | n.a. | surgical | 24 mo |

| Mardassi et al. 2011[40] | 70 CWU+ OPL | 24 | 27.2 | 32.8 | 15 | 19.5 | 4/70 (5.7%) | n.a. | surgical | 9.8 mo |

| Nevoux et al. 2011[41] | 116 CWU | 116 | / | 41 | / | 22.4 | 17/116 (14.7%) | 2: 1y, 6: 2 y, 5: 5y, 1: >5y, 3: n.a. | surgical | 34 mo |

| Berenholz et al. 2013[42] | 15 CWD, 50 CWU, 87 n.a. | 16 | 32.5 | 30.6 | 11.9 | 15.8 | 10/152 (6.6%) | n.a. | surgical | 4.3 y |

| Gostian et al. 2013[43] | 1 CWD, 11 CWU | n.a. | / | 26.6 | / | 18.8 | 0/12 (0%) | / | / | 32 mo |

| Hess-Erga et al. 2013[44] | 31 OPL, 40 n.a. | n.a. | 28 | 37 | 15 | 20 | 4/76 (5%) | <1y | 2 surgical | 5.2y |

| Meulemans et al 2013[45] | 7 CWD, 65 CWU, 17 OPL | 0 | 26.2 | / | 15.6 | / | 3/89 (3.4%) | / | surgical | 13 mo |

| Shah et al. 2013[46] | 19 CWU | 0 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 0/19 (0%) | / | / | 11.1y |

| Birk et al. 2014[47] | n.a. | n.a. | 26.9 | / | 15.4 | / | 1/62 (1.6%) | n.a. | n.a. | 7 mo |

| Fayad et al. 2014[48] | 8 CWD, 21 CWU, 30 OPL, 3 n.a. | 23 | / | 35.1 | / | 18 | 1/62 (1.6%) | 1 y | n.a. | 21.7 mo |

| Órfão et al. 2014[49] | 1 CWD, 11 CWU, 31 OPL | 0 | 32.8 | 37.1 | 21.9 | 25.7 | 1/43 (2%) | n.a. | n.a. | 20 mo |

| Pringle et al. 2014[50] | 9 CWD, 47 CWU, 17 OPL | 52 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5/73 (6.8%) | n.a. | surgical | 6 - 96 mo |

| Baker et al. 2015[51] | n.a. | 38 | 28.2 | 30.3 | 16.5 | 20.6 | 5/ 83 (6.0%) | n.a. | surgical | 41.8 mo |

| Boleas-Aguirre et al. 2015[52] | 2 CWD, 2 CWU, 12 OPL | n.a. | / | 34 | / | 16.4 | 0/ 16 (0%) | / | / | 12 mo |

| Lee et al. 2015[53] | 15 CWD, 11 CWU, 1 OPL | n.a. | 23 | 28 | 12 | 15 | 0/27 (0%) | / | / | 6 mo |

| Ocak et al. 2015[54] | 15 CWU, 3 OPL | n.a. | 33.7 | 38 | 8.6 | 19 | 1/18 (5.5%) | 12 mo | n.a. | 38.5 mo |

| Roux et al. 2015[55] | 68 CWU | 19 | 23.5 | 31 | 19.5 | 26 | 0/68 (0%) | / | / | 23 mo |

| Wolter et al. 2015[56] | n.a. | n.a. | / | 44 | / | 30 | 1/75 (1.3%) | 3.9 y | surgical | 2.7 y |

| Faramarzi et al. 2016[57] | 45 OPL | 45 | / | 36 | / | 24.7 | 2/45 (4.4%) | n.a. | n.a. | 6-12 mo |

| Gostian et al. 2016[58] | 15 CWD, 32 CWU | n.a. | 25.7 | n.a. | 16.8 | n.a. | 1/47 (2%) | / | / | 6.5y |

| Gostian et al. 2016[59] | 18 CWD, 24 CWU | 0 | / | 33 | / | 22 | 2/42 (4.8%) | 6 mo | surgical | 6.8y |

| O’Connell et al. 2016[60] | n.a. | 77 | 30.9 | 37.9 | 17.6 | 21.8 | 5/149 (3.2%) | n.a. | surgical | 51.6 mo |

| Amith and Rs. 2017[61] | 3 OPL, 17 n.a. | 3 | 44.4 | / | 31.3 | / | 3/20 (15%) | n.a. | n.a. | 12 mo |

| Govil et al. 2017[62] | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 29/101 (29%) | 1.3 y | surgical | 2.2y |

| McMullen et al. 2017[63] | n.a. | 50 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 1/71 (1.4%) | 8 mo | conservative | 10.2 mo |

| Mulazimoglu et al. 2017[64] | 33 OPL, 93 n.a. | 33 | / | 28.2 | / | 22.3 | 30/126 (23.8%) | 26 mo | 12 surgical, 18 n.a. | 4.5 y |

| Choi and Shin. 2018[65] | n.a. | 8 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 2/45 (4.4%) | / | / | 12 mo |

| Kahue et al. 2018[66] | 5 CWD, 77 CWU, 48 OPL | 10 | 29 | / | 18 | / | 3/130 (2.3%) | 25 mo | surgical | 37 mo |

| Kong et al. 2017[67] | n.a. | n.a. | 27.6 | 28.5 | 26 | 29 | 4/20 (20%) | n.a. | n.a. | 27 mo |

| Kumar et al. 2017[68] | n.a. | 0 | 32.1 | 37.5 | 26.3 | 21.6 | 1/37 (2.7%) | n.a. | n.a. | 6 mo |

| Lahlou et al. 2018[69] | 46 CWD, 74 CWU, 160 OPL | 0 | 26 | 30 | 15 | 20 | 17/280 (6.1%) | n.a. | surgical | 12 mo |

| Saliba et al. 2018[70] | 36 CWD, 122 CWU | 62 | / | 38 | / | 26.3 | 24/158 (15%) | n.a. | surgical | 18 mo |

| Gu and Chi. 2019[71] | 206 CWD | 0 | 27.8 | 28 | 16.4 | 18.4 | 2/206 (1.0%) | / | / | 30 mo |

| Haidar et al. 2019[72] | 133 CWU | 8 | 29.6 | 33.3 | 12.9 | 18.7 | 5/133 (2.3%) | n.a. | n.a. | 6 mo |

| Potsangbam and Akoijam. 2019[5] | 20 OPL | 20 | 37.1 | 40.3 | 17.6 | 22.5 | 7/20 (35%) | 4- 8y | n.a. | 3y |

| Wood et al. 2019[73] | 24 CWD, 114 CWU, 15 OPL | 14 | / | 37.5 | / | 24.9 | 1/153 (0.6%) | n.a. | surgical | 44 mo |

| Mantsopoulos et al. 2021[74] | n.a. | n.a. | 22.7 | / | 15.7 | / | 8/274 (2.9%) | n.a. | n.a. | 4 mo |

| Baazil et al. 2022[75] | 3 CWD, 33 CWU, 70 OPL | 74 | / | 38.1 | / | 27.6 | 8/106 (7.5%) | n.a. | n.a. | 11.7 mo |

| Bahmad and Perdigão. 2022[76] | 13 CWD | n.a. | / | 35.1 | / | 20.7 | 0/13 (0%) | / | / | 6 mo |

| Kraus et al. 2022[77] | n.a. | 0 | 21.8 | / | 10.5 | / | 2/38 (5.3%) | n.a. | n.a. | 1-9 y |

| Park et al. 2022[78] | 113 CWD, 22 CWU | 0 | 28.1 | 28.1 | 18.4 | 23.5 | 1/135 (0.7%) | n.a. | n.a. | 8.1 mo |

| Plichta et al. 2022[79] | 24 OPL | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 1/24 (4.1%) | n.a. | surgical | 24 mo |

| Van Hoolst et al. 2022[80] | 28 CWD, 23 OPL, 62 n.a. | n.a. | / | 32.7 | / | 21.7 | 17/113 (15.0%) | n.a. | surgical | 39 mo |

| Chien et al. 2023[81] | 8 OPL | 0 | 25.9 | / | 10.8 | / | 0/8 (0%) | / | / | 3.58 mo |

| Faramarzi et al. 2023[82] | 248 OPL | 248 | 34 | 37.6 | 21.2 | 24.6 | 7/248 (2.8%) | n.a. | n.a. | 12.5 mo |

| Gülşen and Çıkrıkcı. 2023[83] | 21 OPL | 0 | / | 37.1 | / | 14.5 | 1/21 (4.8%) | n.a. | surgical | 12 mo |

| Kálmán et al. 2023[84] | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 11/130 (8.5%) | n.a. | surgical | 8.8 mo |

| Kim et al. 2023[85] | 130 OPL | 130 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 10/130 (7.7%) | n.a. | n.a. | 22.7 mo |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).