1. Introduction

Cashmere fiber is an important product of cashmere goats, which is produced by secondary hair follicles in the skin. Cashmere fiber is characterized by cyclical and seasonal growth, which begins to appear and grow on the body surface in summer, continues to grow in autumn to early winter, stops growing in winter, and naturally sheds from the body surface in spring [

1]. Therefore, the growth cycle of cashmere fiber is divided into a non-growing period (from late spring to late summer) and a growing period (from late summer to winter) [

2,

3]. Cashmere yield is determined by the length, diameter, and number of cashmere fibers [

4,

5]. Therefore, it is an important way to increase cashmere production performance by increasing cashmere length and number, i.e., promoting the initiation of cashmere growth in the cashmere non-growing period and accelerating the growth in cashmere growing period [

6], and increasing the population of active secondary hair follicles [

7].

Numerous studies have shown that cashmere production performance can be significantly improved by appropriately increasing the nutritional level during the cashmere growing period. Increasing the dietary protein level of Liaoning cashmere goats during the cashmere growing period significantly increased cashmere staple length and yield, however, the addition of protein did not increase cashmere staple length when the protein level was increased to a certain level [

8]. Feeding Liaoning cashmere goats with high nutrient levels throughout the year significantly increased cashmere yield [

9]. The cashmere staple length was significantly higher in all the year-round housing cashmere goats than in grazed cashmere goats [

10]. Results of previous studies suggested that appropriately increasing diet and nutritional levels during the cashmere growing period could significantly improve cashmere production performance, however, further increasing nutritional levels could not change cashmere production performance when nutritional levels increased to meet the growth demand of cashmere fiber. Currently, previous studies focus on the effect of nutritional level during the cashmere growing period on cashmere production performance, however, little attention was paid to the effect of nutrition level during the cashmere non-growing period on cashmere production performance. It was reported that, under natural light conditions from May to October, there were no significant differences in cashmere yield, staple length, diameter, and secondary hair follicle activity for cashmere goats with body weight gain of 8-10 kg [

11]. Because body weight gain reflects the nutrition level to a certain extent [

12,

13], it is feasible to investigate the effects of nutritional level on cashmere production performance and metabolic activity of secondary hair follicles in cashmere goats by determining body weight gain during cashmere non-growing period.

It is generally believed that secondary hair follicles in the skin of cashmere goats are in the anagen phase from March to September, in the catagen phase from September to December, and in the telogen phase from December to March [

14]. Although cashmere fiber does not grow during the cashmere non-growing period, secondary hair follicles in the skin are in the transition stage from telogen to anagen and in the process of structure reconstruction, which determines the numbers of cashmere fiber. Therefore, we make a hypothesis that the high nutrient level during the cashmere non-growing period may increase secondary hair follicle activity and cashmere production performance. In the present study, we measured the body weight gain of cashmere goats during the cashmere non-growing period, then investigated the correlation between body weight gain and cashmere production performance and secondary hair follicle activity, and further studied the effects of body weight gain on cashmere production performance and secondary hair follicle activity. This study will provide a theoretical basis for the practice of supplementary feeding of cashmere goats during cashmere non-growing periods to increase cashmere production performance.

2. Materials and Methods

All experimental procedures in the present study were performed following the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Agricultural Animals in Research and Teaching and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanxi Agricultural University (Taigu, China). The experimental ewe goats were reared on a commercial farm of YiWei White Cashmere Goat Farm located in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China, 39°06′ N, 107°59′ E.

2.1. Animals, experimental design, and management

A total of 50 adult ewe goats with single kids were randomly selected from a flock of 230 Inner Mongolian cashmere goats, including 20 two-year-old goats, 15 three-year-old goats, and 15 four-year-old goats. The experimental ewe goats were weighed in May and September 2019 respectively and were divided into two groups ranging from 0 to 5.0 kg (n=30) and 5.0 to 10.0 kg (n=20) according to the body weight gain between the two weights. Throughout the year, all goats were on pasture from 0800 to 1700 h daily and housed in an open barn from 1800 to 0700 h under natural photoperiodic conditions. Additional supplementary concentrates were provided to goats from January to June, at a dose of 0.275 kg/d per goat in January, gradually increasing to 0.4 kg/d in April and subsequently to 0.55 kg/d in May and June to meet nutrient requirements of animals during gestation and subsequent lactation. The supplementary concentrate consisted of 70% corn and 30% feed concentrate and was purchased from a local feed company (Baotou Jiuzhoudadi Biotech Company, Baotou, China). Ewe goats were mated in October, kidded in March, and weaned in July. The experimental cashmere goats were combed on April 30, 2020.

2.2. Sample collection

Skin biopsies were excised from the right mid-side flank region in January 2020 by using a trephine (1 cm diameter). The circular skin specimens were placed flat on tissue processing cassettes, then soaked in 4% neutral formalin solution for 24 hours of fixation, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol solutions, and finally embedded in paraffin wax for transverse sections. Before combing in April 2020, fleece samples within an area of 10 cm × 10 cm were shorn from the left mid-side flank region of each goat for the measurement of fiber staple length and diameter. The total cashmere weight of each goat was recorded after combing in April 2020.

2.3. Cashmere fibre measurements

Before washing, cashmere fibers were manually separated from fleece samples containing a mixture of coarse hairs and cashmere fibers and then washed with carbon tetrachloride and distilled water, and finally air dried in a draught cupboard. Cashmere fiber staple length was measured using the ruler method as described by Yang et al.,[

15]. The staple length of each sample was determined as the mean value of 100 fibers. Cashmere fiber diameter was measured by an optical microscopic projection method as described by Peterson and Gherardi (1996) [

16] using an automated analyzer (Optic Fiber Diameter Analyzer, CU-6, Beijing United Vision Technical Company, Beijing, China). The diameter of each sample was determined as the mean value of 200 fibers.

2.4. Determination of indicators related to hair follicle population

Skin transverse sections were prepared as described by Yang et al. (2019) [

15]. Briefly, transverse sections were serially sectioned at 5 µm thick parallel to the skin surface using a rotary microtome (Leica RM2235, Leica, Germany). Meanwhile, the hair follicle structure was continuously observed. Transverse sections were collected until 5-10 primary follicles with a sebaceous gland appeared. Skin transverse sections were stained by a modified Sacpic method (Nixon, 1993) [

17]. Images of hair follicles were captured by a microscope camera (Leica ICC 50 W, Leica, Germany). For each sample, 10 microscopic fields from sections within the sebaceous gland were obtained. Hair follicles in each counting area were counted plus all of those intercepting the top and left margins of the counting area; any that were intercepted by the bottom and right margins were not included in the count. There are two types of hair follicles in the skin of cashmere goats: primary hair follicle and secondary hair follicle, and they are easily distinguished from each other based on their specific characteristics. Briefly, the primary hair follicles are greater than the secondary hair follicles in size, and the primary hair follicles contain large fibers with a narrow cortex and a very large medulla in a transverse section; while the secondary hair follicles contain only a small medulla or none. The primary hair follicles are arranged in line on one side and the secondary hair follicles surround the primary hair follicles on the other side in a follicle group. In addition, the primary hair follicles are accompanied by accessory structures such as the sebaceous gland and arrector pili muscle. Active and inactive hair follicles were distinguished from each other using the method described by Nixon [

17] and counted separately. Briefly, follicles were considered active if they contained a fiber or a fiber canal and were considered inactive if there was no fiber canal or they were filled with root sheath cells. The mean number of hair follicles in 10 fields was determined as the final number of follicles for the defined area of 1.11 square mm. To eliminate any effects of changes in live weight or body surface area on hair follicle density, the ratio of secondary follicles to primary follicles (S:P) [

18], the hair follicle density index (DI) [

19], and the hair follicle number (FN) [

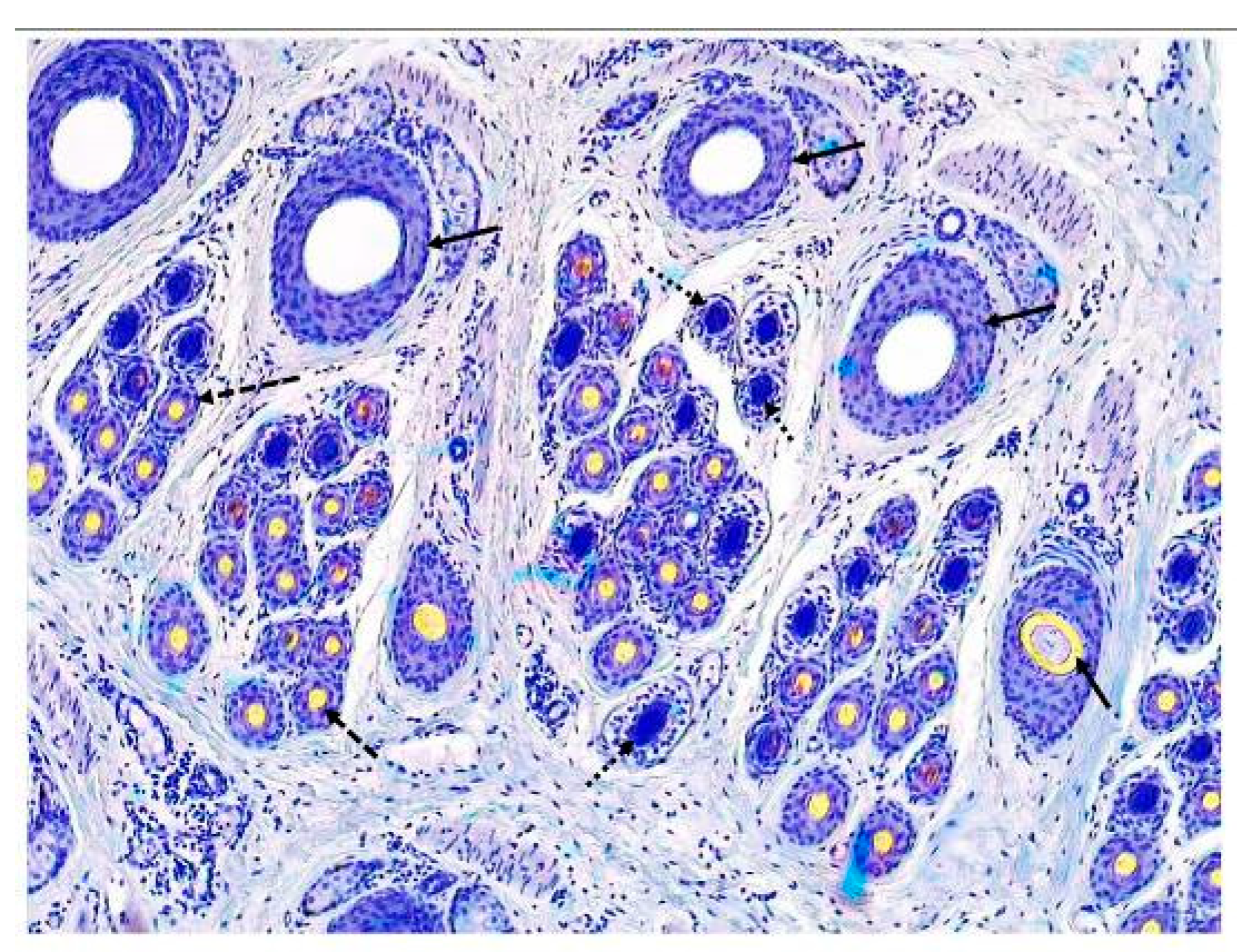

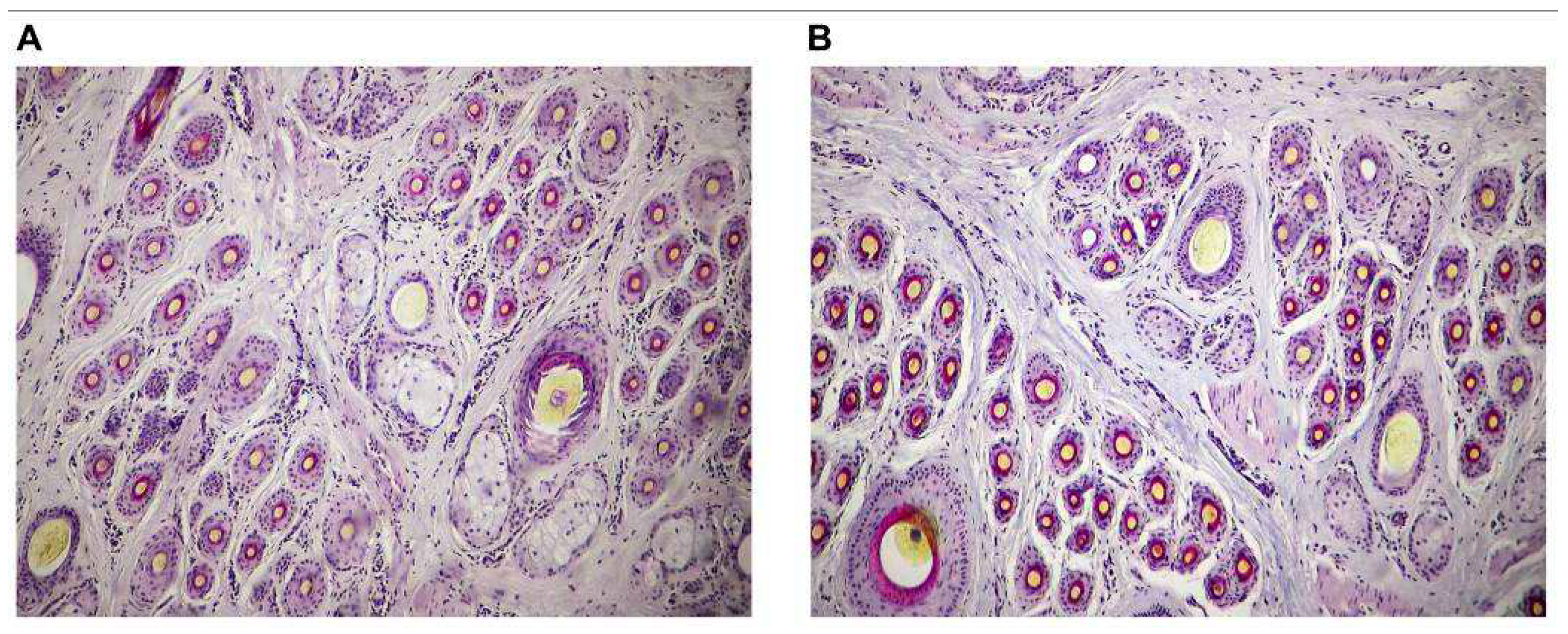

20] were calculated for indicators of follicle population. Therefore, indicators related to the primary hair follicle population include primary hair follicle density index (PFDI) and primary hair follicle number (PFN). Indicators related to the secondary hair follicle population include secondary hair follicle density index (SFDI), secondary hair follicle number (SFN), and the ratio of secondary follicles to primary follicles (S:P). Since the activity of primary hair follicles is not synchronized and the research focus is not on primary hair follicles and coarse hairs, indicators of primary hair follicle activity are not calculated in the present study. Indicators related to the active secondary hair follicle population include active secondary hair follicle density index (ASFDI), active secondary hair follicle number (ASFN), the ratio of active secondary follicles to primary follicles (Sf:P), and the percentage of active secondary follicles (PASF). The typical structure of hair follicles in the skin of cashmere goats is shown in

Figure 1.

2.5. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed on SAS 9.2 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Pearson correlation analysis between body weight gain and cashmere production performance (cashmere yield, cashmere fiber staple length, cashmere fiber diameter), indicators related to active secondary hair follicle population (ASFDI, ASFN, Sf:P, PASF) were performed using the CORR procedure. The correlation is defined as follows: the correlation coefficient |r|≥0.5 is strongly correlated, 0.3≤|r| < 0.5 is moderately correlated, 0.1≤|r|<0.3 is weakly correlated, and |r|<0.1 is not correlated [

21]. Variance in cashmere production performance (cashmere yield, cashmere fiber staple length, cashmere fiber diameter), indicators related to primary hair follicle population (PFDI, PFN), indicators related to secondary hair follicle population (SFDI, SFN, S:P), indicators related to active secondary hair follicle population (ASFDI, ASFN, Sf:P, PASF) were measured using the two independent sample t-test procedures. The data are expressed as mean and standard deviation (Mean ± SD) and were considered statistically significant and highly significant at

P < 0.05 and

P < 0.01, respectively.

4. Discussion

Cashmere fiber is characterized by cyclical and seasonal growth, which does not grow during the period from the fall of cashmere (late April and early May) to the re-growth of the body surface (late July and early August). Therefore, the growth cycle of cashmere fiber is divided into a non-growing period (from late spring to late summer) and a growing period (from early autumn to late winter) [

2,

3]. At present, the research on the effects of nutrient levels on cashmere production performance mainly focuses on the growing period of cashmere fiber. However, little attention was paid to the effect of nutrient levels during the cashmere non-growing period on cashmere production performance. Because body weight gain reflects nutrition levels of high and low levels to a certain extent [

12,

13], we studied the effects of body weight gain during the cashmere non-growing period on cashmere production performance and secondary hair follicle activity. The results showed that the body weight gain during the cashmere non-growing period had a positive correlation with cashmere production performance and secondary hair follicle activity. Furthermore, cashmere goats with a body weight gain of 5.0-10.0 kg during the cashmere non-growing period had a higher cashmere production performance and secondary hair follicle activity than those with a body weight gain of 0-5.0 kg.

Previous studies showed that dietary coated methionine supplementation during the cashmere growing period significantly improved cashmere staple length and cashmere yield of Inner Mongolian Cashmere goats [

22] and Shanbei White Cashmere goats [

23]. To a certain extent, increasing dietary nutrition level increased cashmere staple length and cashmere yield; however, when the nutrient level was increased to exceed the need for cashmere growth, increasing the nutrient level did not affect cashmere production performance [

8]. It was reported that the cashmere staple length of house-fed cashmere goats all year round was 0.36 cm longer than that of grazing cashmere goats [

10]. Feeding diets with high nutrient levels throughout the year significantly increased the body weight, cashmere yield, and cashmere staple length of Liaoning cashmere goats [

9]. Based on a comprehensive analysis of the above research results, supplementary feeding during the cashmere non-growing period may contribute to the increase in cashmere staple length and cashmere yield of cashmere goats given high nutrient-level diets throughout the year. The results of this present experiment preliminarily support the above inference. In the present study, the cashmere yield and staple length of cashmere goats with body weight gain of 5.0-10.0 kg were significantly higher than those of cashmere goats with body weight gain of 0-5.0 kg during the cashmere non-growing period. Since body weight gain reflects dietary nutrient level to a certain extent [

13], the results of this experiment suggested that increasing dietary nutrient levels during cashmere non-growing periods could significantly improve cashmere yield and cashmere staple length of cashmere goats. Cashmere yield is determined by cashmere staple length, cashmere diameter, and cashmere number [

24]. In the present study, the cashmere yield and staple length of cashmere goats with body weight gain of 5.0-10.0 kg were 17.10% and 8.09% higher than those of cashmere goats with body weight gain of 0-5.0 kg, respectively. However, there was no difference in cashmere diameter between the two groups. Since the increase in cashmere yield is not proportional to the increase in cashmere staple length, it suggests an increase in cashmere number. During the cashmere growing period, the number of cashmere fibers is equal to the population of active secondary hair follicles. Therefore, it is necessary to study the effect of body weight gain during the cashmere non-growing period on the population of active secondary hair follicles in the skin of cashmere goats.

It has been confirmed that the morphogenesis of primary hair follicles and secondary hair follicles in the skin of cashmere goats begins from the fetal stage, and primary hair follicles are fully developed at birth and their populations do not change thereafter [

25]. Only part of secondary hair follicles matures at birth and produces cashmere fibers, and most of them mature at 3-6 months after birth, and populations of secondary hair follicles do not change thereafter [

26]. Previous studies showed that feeding high levels of crude protein during the cashmere-growing period had no significant effect on populations of primary hair follicles in cashmere goats [

27]. Similar results were obtained in the present study. In the present study, there was no significant difference in populations of primary hair follicles in the skin of cashmere goats with body weight gain of 0-5.0 kg and 5.0-10.0 kg, which was consistent with results of Denny et al. [

28]. The results of this study and previous studies showed that populations of primary hair follicles in the skin of cashmere goats were not affected by dietary nutrition levels. In the present study, there was no significant difference in populations of secondary hair follicles in the skin of cashmere goats with body weight gain of 0-5.0 kg and 5.0-10.0 kg, indicating that nutritional level did not affect populations of secondary hair follicles in adult cashmere goats, which was consistent with the results of Zhao et al. [

27]. It was reported that feeding high protein level diets to Longdong cashmere goats during the cashmere growing period did not change populations of secondary hair follicles [

27]. The results of the present study and previous studies showed that, for adult cashmere goats, the dietary nutrient level during cashmere growing and non-growing period did not change populations of secondary hair follicles in the skin of cashmere goats, indicating that populations of secondary hair follicles in the skin of cashmere goats do not change throughout their life once they are mature. Meanwhile, the results of this study showed that the hair follicle sectioning technique in the present study was reliable, which provided a reliable condition for counting populations of active secondary hair follicles in the subsequent analysis.

The morphogenesis of secondary hair follicles in the skin of cashmere goats initiates in the fetal period, only part of secondary hair follicles is mature at birth, and most secondary hair follicles mature at the age of 3–6 months after birth [

29]. Once secondary hair follicles are mature, the populations do not change, go through a complete growth period, and then enter a cyclical change process, that is, continuously undergo catagen, telogen, and anagen [

30]. Due to the influence of breed, age, sex, nutritional level, experimental operation, and other factors, the periodic change time of secondary hair follicles in the skin of cashmere goats is slightly different. It is generally believed that the secondary hair follicles in the skin of cashmere goats are in the anagen phase from March to September, in the catagen phase from September to December, and in the telogen phase from December to March [

14]. Previous studies showed that body weight gain of cashmere goats fed high energy level and low energy level diets ranged from 8 to 10 kg under natural light conditions from May to October, and there was no significant difference in secondary hair follicle activity between the two groups [

11]. Similar results were obtained in the present study. In this study, there was a strong positive correlation between body weight gain during the cashmere non-growing period and populations of active secondary hair follicles in the skin of cashmere goats. The populations of active secondary hair follicles in the skin of cashmere goats with a body weight gain of 5.0–10.0 kg was significantly higher than those in the skin of cashmere goats with a body weight gain of 0–5.0 kg. The results of this experiment suggested that improving the nutritional level of cashmere goats during the cashmere non-growing period could significantly increase the metabolic activity of secondary hair follicles, increase the populations of active secondary hair follicles, and then improve cashmere production performance. However, combined with the results of this experiment and Zhang et al. [

11], the metabolic activity of secondary hair follicles could not be further improved when the dietary nutrient level was increased to a certain limit. It was reported that different levels of crude protein supplementation during the cashmere growing period had no significant effect on populations of active secondary hair follicles in Longdong cashmere goats, indicating that secondary hair follicle activity had been determined after completion of the reconstruction of the secondary hair follicle structure and then increasing the nutritional level could not change populations of active secondary hair follicles [

27]. Although cashmere fiber does not grow during the cashmere non-growing period, secondary hair follicles in the skin are in the transition stage from telogen to anagen and in the process of structure reconstruction [

14,

31], which determines populations of cashmere fiber. The results of this study suggested that nutritional manipulations such as supplementary feeding during the cashmere non-growing period could significantly increase the activity of secondary hair follicles and then increase cashmere production performance. However, specific nutritional manipulations during the cashmere non-growing period need further research to increase cashmere production performance.

This symbol indicates the primary hair follicle;

This symbol indicates the primary hair follicle;  This symbol indicates the inactive secondary hair follicle;

This symbol indicates the inactive secondary hair follicle;  This symbol indicates the active secondary hair follicle.

This symbol indicates the active secondary hair follicle.

This symbol indicates the primary hair follicle;

This symbol indicates the primary hair follicle;  This symbol indicates the inactive secondary hair follicle;

This symbol indicates the inactive secondary hair follicle;  This symbol indicates the active secondary hair follicle.

This symbol indicates the active secondary hair follicle.