Submitted:

07 September 2023

Posted:

11 September 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant materials and experimental field

2.2. Experimental design

2.3. Soil sample collection

2.4. Measurement of soil physical and chemical properties

2.5. Data analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of integrated cultivation practices on soil nutrients in paddy field

3.2. Soil microbial diversity in paddy fields (Alpha diversity)

3.3. Correlation analysis of soil nutrients and microbial diversity index

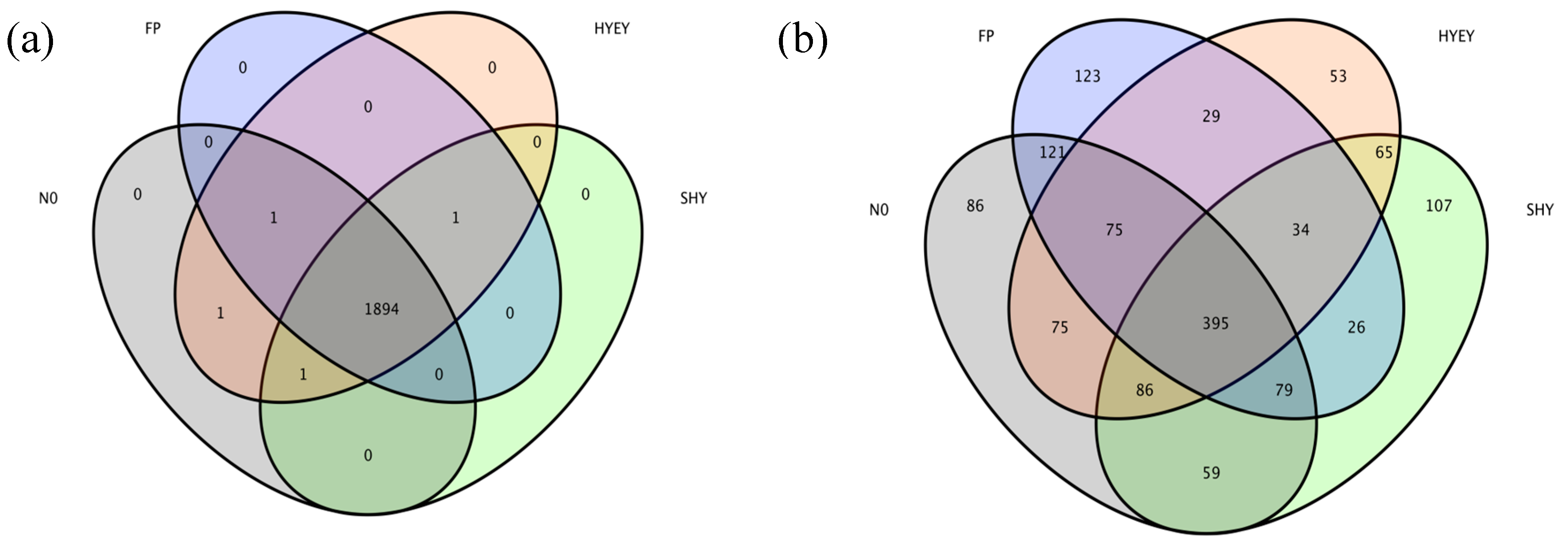

3.4. Wayne map of the OUT distribution of soil bacteria

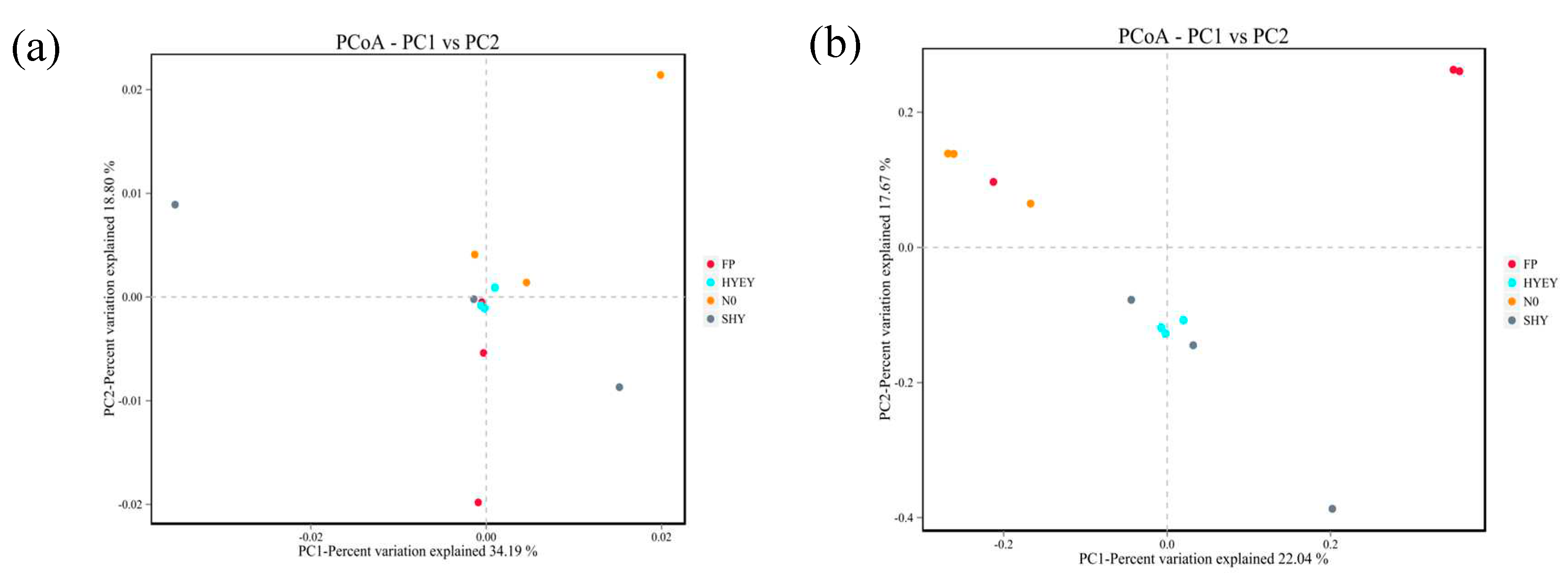

3.5. Principal component analysis of microbiology

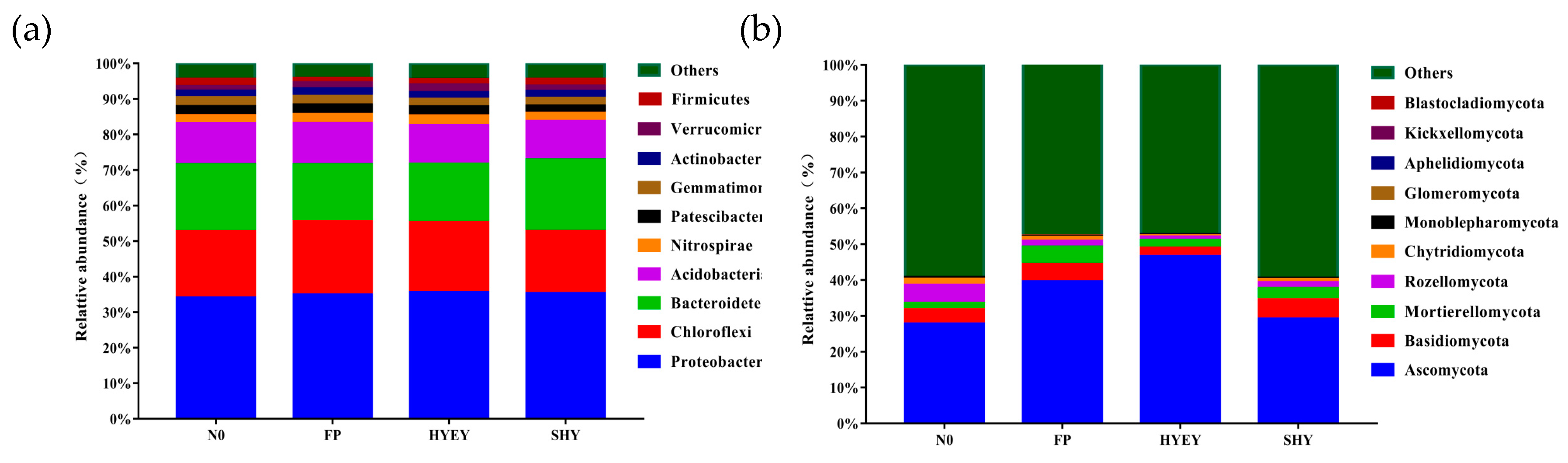

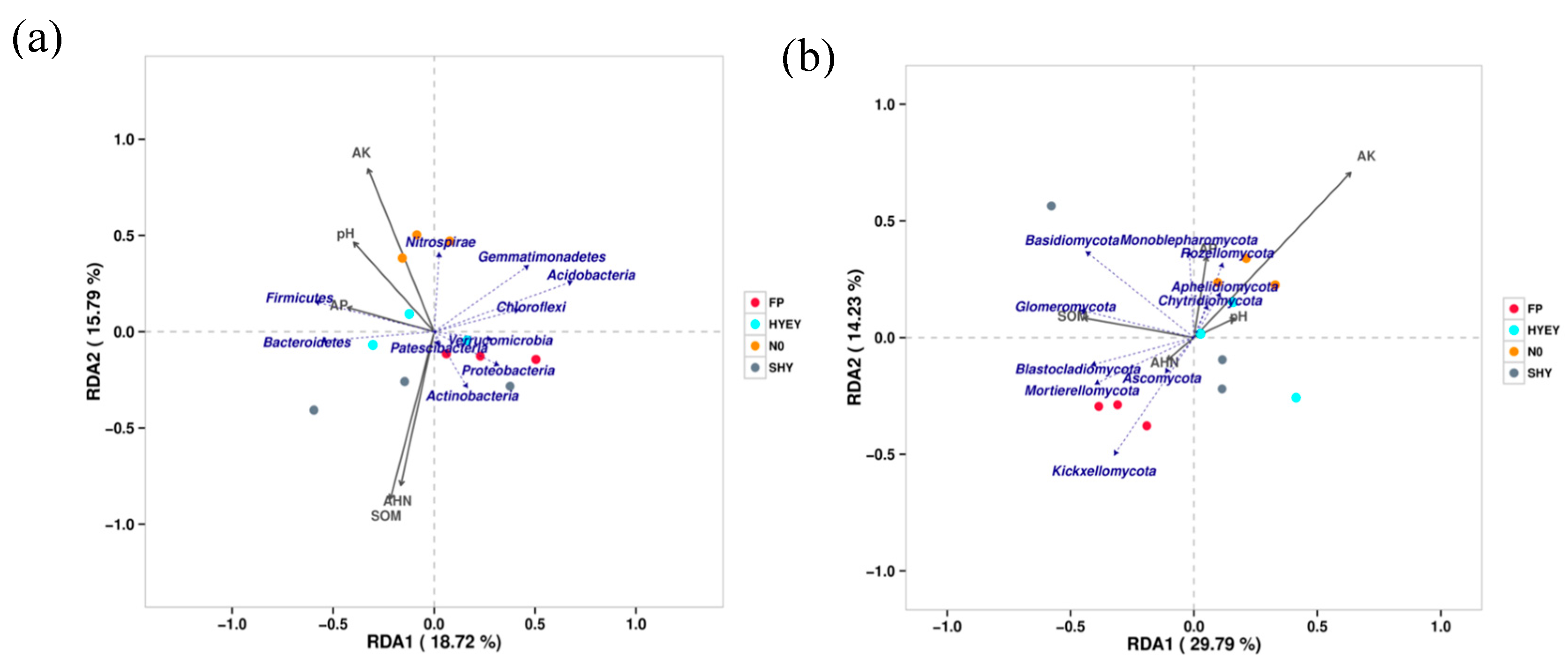

3.6. Composition structure of bacterial and fungal community at the phylum level

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of integrated cultivation practices on the Alpha diversity of soil microorganisms

4.2. Effect of integrated cultivation practices on the composition of soil microbial community

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vogel, T.M.; Simonet, P.; Jansson, J.K.; Hirsch, P.R.; Tiedje, J.M.; van Elsas, J.D.; Bailey, M.J.; Nalin, R.; Philippot, L. TerraGenome: a consortium for the sequencing of a soil metagenome. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2009, 7, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.W.; Wang, C.; Xue, R.; Wang, L.J. Effects of salinity on the soil microbial community and soil fertility. Journal of Integrative Agriculture. 2019, 18, 1360–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Huntley, J.; Fierer, N.; Owens, S.M.; Betley, J.; Fraser, L.; Bauer, M.; Gormley, N.; Gilbert, J.A.; Smith, G.; Knight, R. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. The ISME Journal. 2012, 6, 1621–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.M.; Liu, S.R.; Wang, H.; Hu, Z.D.; Li, Z.G.; You, Y.M. Changes of soil microbial biomass carbon and community composition through mixing nitrogen-fixing species with Eucalyptus urophylla in subtropical China. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2014, 73, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.F.; Li, Z.P.; Liu, M.; Jiang, C.Y.; Che, Y.P. Microbial community and functional diversity associated with different aggregate fractions of a paddy soil fertilized with organic manure and/or NPK fertilizer for 20years. Journal of Soils and Sediments. 2015, 15, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Shi, K.; Huang, Q.R.; Li, D.M.; Liu, M.Q.; Li, H.X.; Hu, F.; Jiao, J.G. The changes of microbial community structure in red paddy soil under long-term fertilization. Acta Pedologica Sinica. 2015, 52, 697–705. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Jorquera, M.A.; Martínez, O.A.; Marileo, L.G.; Acuña, J.J.; Saggar, S.; Mora, M.L. Effect of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilization on the composition of rhizobacterial communities of two Chilean Andisol pastures. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2014, 30, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Wu, M.N.; Wei, W.X. Effect of long-term application of nitrogen fertilizer on the diversity of nitrifying genes (amoA and hao) in paddy soil. Environment Science. 2011, 32, 1489–1496. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Grover, J.P. Predation, competition, and nutrient recycling: a stoichiometric approach with multiple nutrients. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 2004, 229, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.Q.; Ding, L.J.; Xue, K.; Yao, H.Y.; Quensen, J.; Bai, S.J.; Wei, W.X.; Wu, J.S.; Zhou, J.Z.; Tiedje, J.M.; Zhu, Y.G. Long-term balanced fertilization increases the soil microbial functional diversity in a phosphorus-limited paddy soil. Molecular Ecology. 2015, 24, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisner, A.; Jacquiod, S.; Snoek, B.L.; Ten, H.F.C.; van der Putten, W.H. Drought legacy effects on the composition of soil fungal and prokaryote communities. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2018, 9, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoni, S.; Schimel, J.P.; Porporato, A. Responses of soil microbial communities to water stress: results from a meta-analysis. Ecology. 2012, 93, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangi, S.R.; Zhang, H.H.; Wang, D.; Gerik, J.; Hanson, B.D. Soil microbial community composition in a peach orchard under different irrigation methods and postharvest deficit irrigation. Soil Science. 2016, 181, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, C.; Fang, B.H.; Liu, Y.; Kuang, W.; Chen, K.L.; Zhou, X.Q.; Wang, W.X.; Zhang, Y.Z. Effect of different irrigation modes in paddy soil on microbial community functional diversity. Genomics and Applied Biology. 2020, 39, 1632–1641. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Gil, S.V.; Meriles, J.; Conforto, C.; Basanta, M.; Radl, V.; Hagn, A.; Schloter, M.; March, G.J. Response of soil microbial communities to different management practices in surface soils of a soybean agroecosystem in Argentina. European Journal of Soil Biology. 2010, 47, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.M.; Xiao, X.P.; Li, C.; Cheng, K.K.; Shi, L.H.; Pan, X.C.; Li, W.Y.; Wen, L.; Wang, K. Tillage and crop residue incorporation effects on soil bacterial diversity in the double-cropping paddy field of southern China. Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science. 2021, 67, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.B.; Shi, H.; Wu, L.; Cheng, Y.H.; Cai, S.; Huang, S.S.; He, S.L.; Huang, Q.R.; Zhang, K. Effects of cultivation methods on soil microbial community structure and diversity in red paddy. Ecology and Environmental Sciences. 2020, 29, 2206–2214. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.G.; Dai, Y.Y. Analysis report of heilongjiang rice market in 2019. Heilongjiang Liangshi. 2020, 5, 23–27. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Y.D.; Yue Hu, Y.; Jiang, H.F.; Lan, Y.C.; Wang, H.Y.; Xu, L.Q.; Yin, D.W.; Zheng, G.P.; Guo, X. H.Agronomic practices affect rice yield and nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium accumulation, allocation and translocation. Agronomy journal. 2020, 112, 1238–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D. Soil Agrochemical Analysis (Third Edition); (in Chinese). China Agricultural Press: Beijing, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Grice, E.A.; Kong, H.H.; Conlan, S.; Deming, C.B.; Davis, J.; Young, A.C.; Bouffard, G.G.; Blakesley, R.W.; Murray, P.R.; Green, E.D.; Turner, M.L.; Segre, J.A. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science. 2009, 324, 1190–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadou, A.; Song, A.; Tang, Z.X.; Li, Y.L.; Wang, E.Z.; Lu, Y.Q.; Liu, X.D.; Yi, K.K.; Zhang, B.; .Fan, F.L. The effects of organic and mineral fertilization on soil enzyme activities and bacterial community in the below-and above-ground parts of wheat. Agronomy. 2020, 10, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.H.; Gu, T.; Wang, W.; Zhang, B.; Lin, X.G.; Huang, Q.R.; Shen, W.S. The effects of mineral fertilizer and organic manure on soil microbial community and diversity. Plant and Soil. 2010, 326, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Liu, X.J.; Song, L.; Lin, X.G.; Zhang, H.Y.; Shen, C.C.; Chu, H.Y. Nitrogen fertilization directly affects soil bacterial diversity and indirectly affects bacterial community composition. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2016, 92, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, N.; Chen, D.M.; Guo, H.; Wei, J.X.; Bai, Y.F.; Shen, Q.R.; Hu, S.J. Differential responses of soil bacterial communities to long-term N and P inputs in a semi-arid steppe. Geoderma. 2017, 292, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.M.; Su, W.Q.; Chen, H.H.; Barberán, A.; Zhao, H.C.; Yu, M.J.; Yu, L.; Brookes, P.C.; Schadt, C.W.; Chang, S.X.; Xu, J.M. Long-term nitrogen fertilization decreases bacterial diversity and favors the growth of Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria in agro-ecosystems across the globe. Global Change Biology. 2018, 24, 3452–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.E.; Wallenstein, M.D. Soil microbial community response to drying and rewetting stress: does historical precipitation regime matter? Biogeochemistry. 2012, 109, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, U.; Unger, M.; Makeschin, F. Impact of air-drying and rewetting on PLFA profiles of soil microbial communities. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science. 2007, 170, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.J. Effects of wetting and drying conditions on the abundance of anaerobic ammonium oxidation bacteria and ammonia oxidizing archaea in soil. Shanghai: Donghua University, 2017. (in Chinese).

- Zhao, J.; Ni, T.; Li, Y.; Xiong, W.; Ran, W.; Shen, B.; Shen, Q.R.; Zhang, R.F. Responses of bacterial communities in arable soils in a rice-wheat cropping system to different fertilizer regimes and sampling times. PloS ONE. 2014, 9, e85301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.H.; Song, J.; Kim, B.Y.; Kim, M.S.; Joa, J.H.; Weon, H.Y. Characterization of the bacterial and archaeal communities in rice field soils subjected to long-term fertilization practices. Journal of Microbiology. 2012, 50, 754–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.M.; Chen, X.M.; Liang, Y.J.; Huo, X.J.; Zhang, C.H.; Duan, Y.Q.; Yang, Y.H.; Yuan, L. Influence of crop rotation on soil nutrients,microbial activities and bacterial community structures. Acta Prataculturae Sinica 2015, 24, 56–65. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge, D.J.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Travers, S.K.; Val, J. , Oliver, L.; Hamonts, K.; Singh, B.K. Competition drives the response of soil microbial diversity to increased grazing by vertebrate herbivores. Ecology. 2017, 98, 1922–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.M.; Yuan, L.; Huang, J.G.; Ji, J.H.; Hou, H.Q.; Liu, Y.R. Influence of long-term fertilizations on nutrients and fungal communities in typical paddy soil of south China. Acta Agronomica Sinica. 2017, 43, 286–295 (in Chinese). (in Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.F.; Ni, K.; Ma, L.F.; Chen, Z.J.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Ruan, J.Y.; Guo, S.W. Effect of different fertilizer regimes on the fungal community of acidic tea-garden soil. Acta Ecologica Sinica. 2018, 38, 8158–8166. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Pan, F.J.; Han, X.Z.; Song, F.B.; Zhang, Z.M.; Yan, J.; Xu, Y.L. A comprehensive analysis of the response of the fungal community structure to long-term continuous cropping in three typical upland crops. Journal of Integrative Agriculture. 2020, 19, 866–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.G.; Ding, C.F.; Hua, K.; Zhang, T.L.; Zhang, Y.N.; Zhao, L.; Yang, Y.R.; Liu, J.G.; Wang, X.X. Soil sickness of peanuts is attributable to modifications in soil microbes induced by peanut root exudates rather than to direct allelopathy. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2014, 78, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Lv, J.L. Study on the enzyme activities and fertility change of soils by a long-term located utilization of different fertilizers. Chinese Journal of Eco-Agriculture. 2005, 13, 143–145. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, F.T.; Liiri, M.E.; Bjørnlund, L.; Bowker, M.A.; Christensen, S.; Setälä, H.M.; Bardgett, R.D. Land use alters the resistance and resilience of soil food webs to drought. Nature Climate Change. 2012, 2, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, R.L.; Osborne, C.A.; Firestone, M.K. Responses of soil bacterial and fungal communities to extreme desiccation and rewetting. The ISME Journal. 2013, 7, 2229–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.Z.; Li, Y.Y.; Han, J.G.; Yao, H.Y. Effects of changes in water status on soil microbes and their response mechanism: A review. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology. 2019, 30, 4323–4332. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Bapiri, A.; Bååth, E.; Rousk, J. Drying-rewetting cycles affect fungal and bacterial growth differently in an arable soil. Microbial Ecology. 2010, 60, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, S.N. , Rushton, S.P., Lanyon, C.V., Whiteley, A.S., Waite, L.S., Brookes, P.C., Kemmitt, S.; Evershed, R.P.; O’Donnell, A.G. Taxon-specific responses of soil bacteria to the addition of low level C inputs. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2010, 42, 1624–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celine, L.; Dimitris, P.; Sean, M.; Bernard, O.; Steven, S.; Safiyh, T.; Donald, Z.; Daniel, V.D.L. Elevated atmospheric CO2 affects soil microbial diversity associated with trembling aspen. Environmental Microbiology. 2008, 10, 926–941. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry, V.; Rehman, A.; Mishra, A.; Chauhan, S.P.; Nautiyal, C.S. Changes in bacterial community structure of agricultural lnd due to long-term organic and chemical amendments. Microbial Ecology. 2012, 64, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.L.M.; Pellizari, V.H.; Mueller, R.; Baek, K.; Jesus, E.D.C.; Paula, F.S.; Mirza, B.; Hamaoui, G.S.; Tsai, S.M.; Feigl, B.; Tiedje, J.M.; Bohannan, B.J.M.; Nüsslein, K. Conversion of the Amazon rainforest to agriculture results in biotic homogenization of soil bacterial communities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013, 110, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, Z.; Eisenlord, S.D.; Zak, D.R.; Xue, K.; He, Z.L.; Zhou, J.Z. Towards a molecular understanding of N cycling in northern hardwood forests under future rates of N deposition. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2013, 66, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Z.; Song, D.P.; Liang, S.H.; Dang, P.F.; Qin, X.L.; Liao, Y.C.; Siddique, K.H.M. Effect of no-tillage on soil bacterial and fungal community diversity: A meta-analysis. Soil and Tillage Research. 2020, 204, 104721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, H.H.; Sun, M.L.; Xu, N.; Sun, G.Y.; Zhao, M.C. Land use change from upland to paddy field in mollisols drives soil aggregation and associated microbial communities. Applied Soil Ecology. 2020, 146, 103351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podosokorskaya, O.A.; Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E.A.; Novikov, A.A.; Kolganova, T.V.; Kublanov, I.V. Ornatilinea apprima gen. nov. sp. nov. a cellulolytic representative of the class Anaerolineae. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2013, 63, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kragelund, C.; Levantesi, C.; Borger, A.; Thelen, K.; Eikelboom, D.; Tandoi, V.; Kong, Y.; van der Waarde, J.; Krooneman, J.; Rossetti, S.; Thomsen, T.R.; Nielsen, P.H. Identity, abundance and ecophysiology of filamentous Chloroflexi species present in activated sludge treatment plants. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2007, 59, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, M.L.; Zhang, H.H.; Xu, N.; Sun, G.Y. Use of mulberry-soybean intercropping in salt-alkali soil impacts the diversity of the soil bacterial community. Microbial Biotechnology. 2016, 9, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, Y.G.; Ma, R.; Yang, P.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, D.J.; Sun, F.J.; Zhang, F.H. Effects of microbial fertilizers on soil improvement and bacterial communities in saline-alkali soils of lycium barbarum. Journal of Agricultural Biotechnology. 2020, 28, 1499–1510. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Pascault, N.; Ranjard, L.; Kaisermann, A.; Bachar, D.; Christen, R.; Terrat, S.; Mathieu, O.; Lévêque, J.; Mougel, C.; Henault, C.; Lemanceau, P.; Péan, M.; Boiry, S.; Fontaine, S.; Maron, P.A. Stimulation of different functional groups of bacteria by various plant residues as a driver of soil priming effect. Ecosystems. 2013, 16, 810–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauber, C.L.; Strickland, M.S.; Bradford, M.A.; Fierer, N. The influence of soil properties on the structure of bacterial and fungal communities across land-use types. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2008, 40, 2407–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leff, J.W.; Jones, S.E.; Prober, S.M.; Barberán, A.; Borer, E.T.; Firn, J.L.; Harpole, W.S.; Hobbie, S.E.; Hofmockel, K.S.; Knops, J.M.H.; McCulley, R.L.; La, P.K.; Risch, A.C.; Seabloom, E.W.; Schütz, M.; Steenbock, C.; Stevens, C.J.; Fierer, N. Consistent responses of soil microbial communities to elevated nutrient inputs in grasslands across the globe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015, 112, 10967–10972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Feng, W.; Wang, X.J. Composition and diversity of soil fungi community under different sand-fixing plants in the Hulun Buir Desert. Science of Soil and Water Conservation. 2021, 19, 60–68. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Yelle, D.J.; Ralph, J.; Lu, F.C.; Hammel, K.H. Evidence for cleavage of lignin by a brown rot basidiomycete. Environmental Microbiology. 2008, 10, 1844–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, X.; Zhang, R.T.; Xu, N.; Liu, Y.N.; Chai, C.R.; Wang, J.F.; Fu, X.L.; Zhong, H.X.; Ni, H.W. Fungal community structure of different degeneration deyeuxia angustifolia wetlands in Sanjiang plain. Environmental Science. 2016, 37, 3598–3605. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

| Treatment | SRP | PP | IM | TNFA (ha−1) |

CF (ha−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nano-Silicon | Guifuji | |||||

| N0 | DBM | PW | SWF | 0 | - | - |

| FP | DBM | PW | SWF | 150 | - | - |

| HYEY | DBM | PW | AWD | 160 | 450 | - |

| SHY | PRM | AWNW | AWD | 180 | 450 | 15 |

| Treatments | AHN mg·kg−1 |

AP mg·kg−1 |

AK mg·kg−1 |

SOM g·kg−1 |

pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N0 | 144.06d | 39.00a | 192.48a | 33.03c | 8.44a |

| FP | 161.29c | 36.23a | 112.83d | 36.12b | 8.40a |

| HYEY | 184.70b | 39.16a | 156.10b | 37.21b | 8.36a |

| SHY | 206.55a | 38.90a | 130.82c | 41.50a | 8.33a |

| Microbial species | Samples | ACE | Chao1 | Shannon | Simpson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | N0 | 1885.72ab | 1890.88a | 6.72ab | 0.0026bc |

| FP | 1886.69ab | 1891.02a | 6.70ab | 0.0029ab | |

| HYEY | 1895.37a | 1897.22a | 6.78a | 0.0024c | |

| SHY | 1867.09b | 1871.71a | 6.63b | 0.0031a | |

| Fungus | N0 | 731.04a | 744.75a | 5.11ab | 0.0165b |

| FP | 511.07b | 520.88b | 5.59a | 0.0106b | |

| HYEY | 466.97c | 472.93c | 3.53c | 0.1563a | |

| SHY | 519.52b | 530.58b | 4.89b | 0.0202b |

| Microbial species | Parameters | AHN | AP | AK | SOM | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ACE | -0.221 | 0.002 | 0.145 | -0.583* | -0.080 |

| Chao1 | -0.226 | -0.074 | 0.153 | -0.583* | -0.113 | |

| Simpson | 0.36 | -0.169 | -0.538 | 0.545 | -0.16 | |

| Shannon | -0.256 | 0 | 0.317 | -0.423 | -0.082 | |

| Fungus | ACE | -0.661* | 0.066 | 0.743** | -0.633* | 0.39 |

| Chao1 | -0.651* | 0.068 | 0.732** | -0.623* | 0.369 | |

| Simpson | 0.258 | 0.114 | 0.153 | 0.032 | -0.122 | |

| Shannon | -0.353 | -0.15 | -0.166 | -0.122 | 0.154 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).