Submitted:

05 September 2023

Posted:

07 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

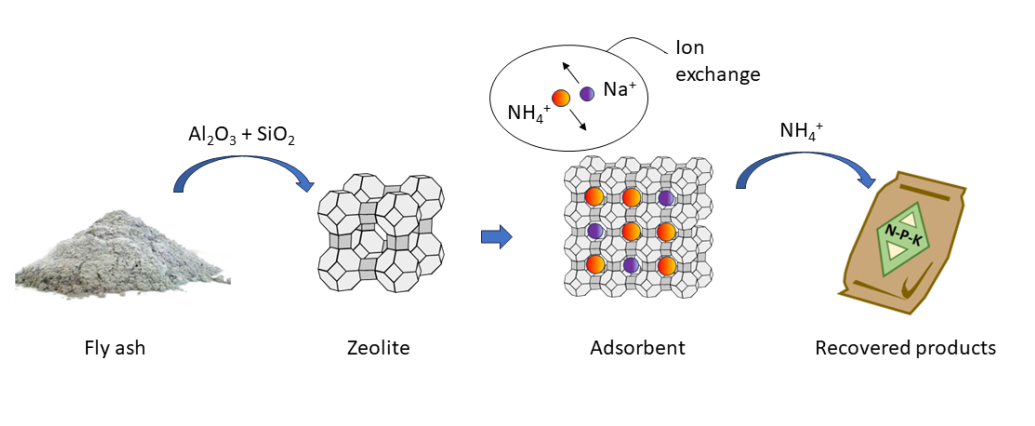

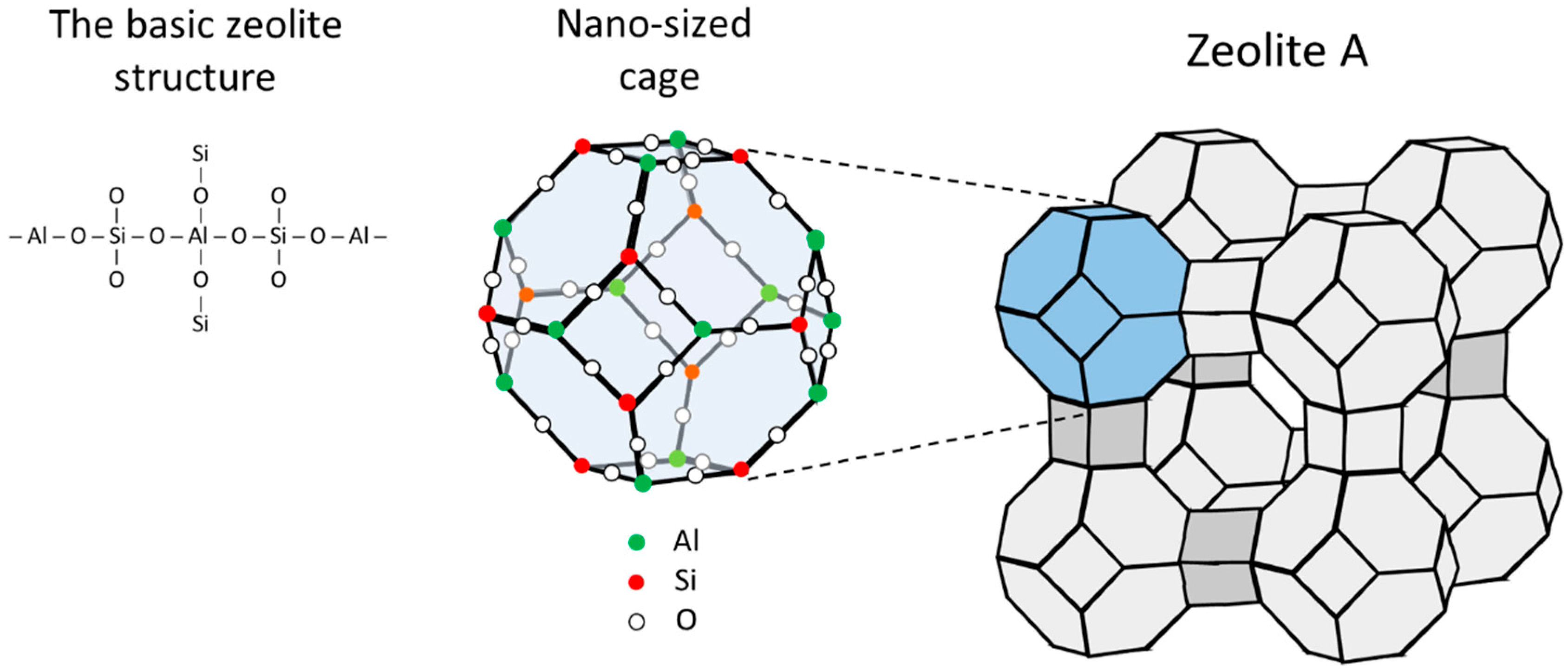

3. Zeolites

3.1. The crystalline structure of zeolites

3.2. Naturally and synthesized zeolites

3.3. Zeolite synthesis

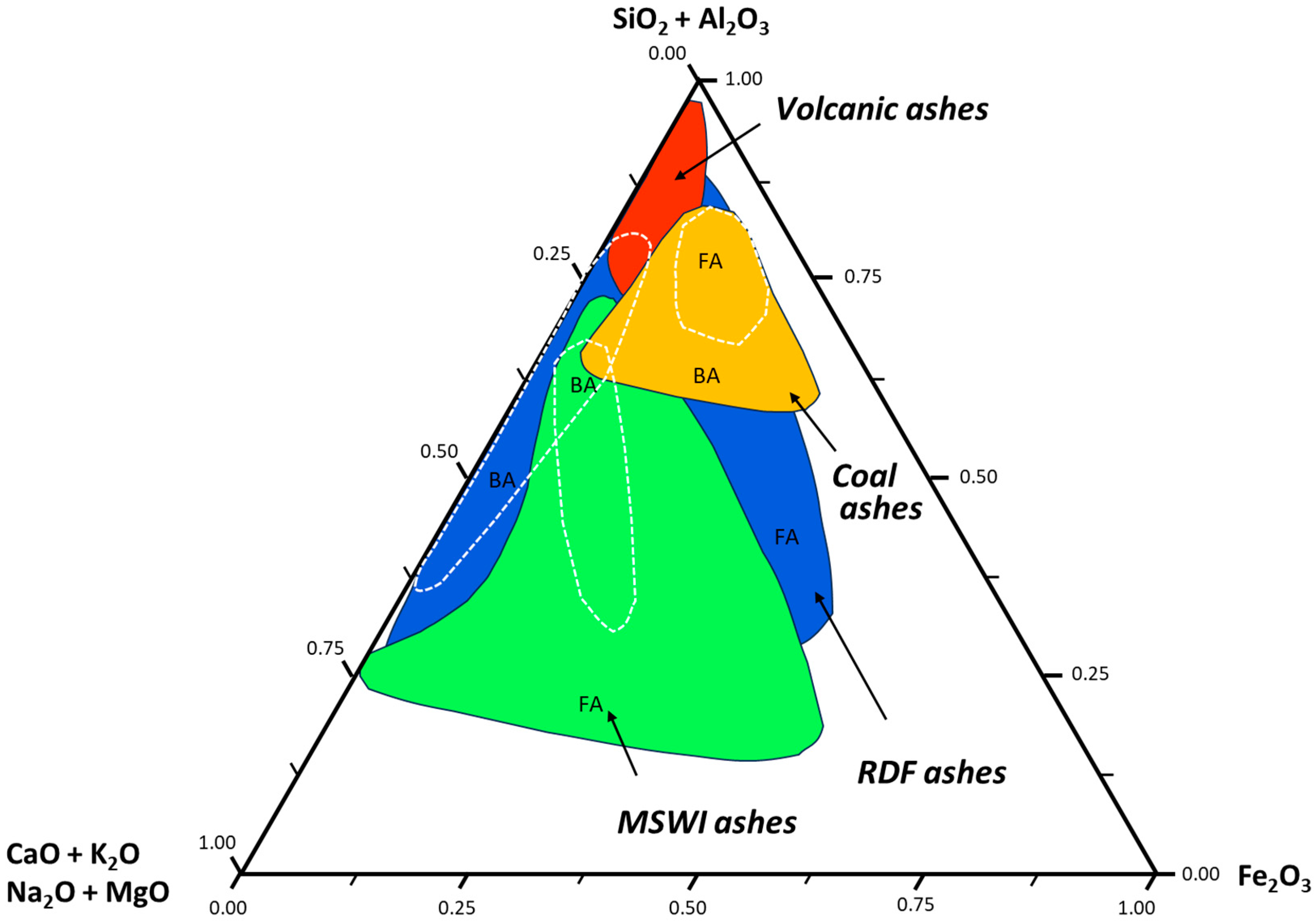

3.4. MSW-FA as source to silicate and alumina in zeolite synthesis

| Element | Unit | Fly ash/APC residues | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Median | ||

| Main elements | ||||

| Si | g/kg | 36 | 190 | - |

| Al | g/kg | 6.4 | 93 | - |

| Fe | g/kg | 0.76 | 71 | - |

| Ca | g/kg | 46 | 361 | - |

| Mg | g/kg | 1.1 | 19 | - |

| K | g/kg | 17 | 109 | - |

| Na | g/kg | 6.2 | 84 | - |

| Ti | g/kg | 0.7 | 12 | - |

| S | g/kg | 1.4 | 32 | - |

| Cl | g/kg | 45 | 380 | - |

| P | g/kg | 1.7 | 9.6 | - |

| Mn | g/kg | 0.2 | 1.7 | - |

| TOC | g/kg | 4.9 | 17 | - |

| LOI | g/kg | 11 | 120 | - |

| SiO2 | % | 11,5 | 41,4 | 19,1 |

| Al2O3 | % | 4,7 | 24,3 | 10,9 |

| CaO | % | 17 | 31,5 | 22,0 |

| SO3 | % | 3 | 10,2 | 6,4 |

| Na2O | % | 3,8 | 9,6 | 5,9 |

| K2O | % | 2 | 8,1 | 4,5 |

| Fe2O3 | % | 1,3 | 5,9 | 2,5 |

| MgO | % | 1,7 | 6,9 | 2,7 |

| Minor elements | ||||

| As | mg/kg | 18 | 960 | - |

| Cd | mg/kg | 16 | 1 660 | - |

| Cr | mg/kg | 72 | 570 | - |

| Cu | mg/kg | 16 | 2 220 | - |

| Hg | mg/kg | 0.1 | 51 | - |

| Ni | mg/kg | 19 | 710 | - |

| Pb | mg/kg | 254 | 27 000 | - |

| Zn | mg/kg | 4 308 | 41 000 | - |

3.5. Producing zeolite-like material from MSW fly ash

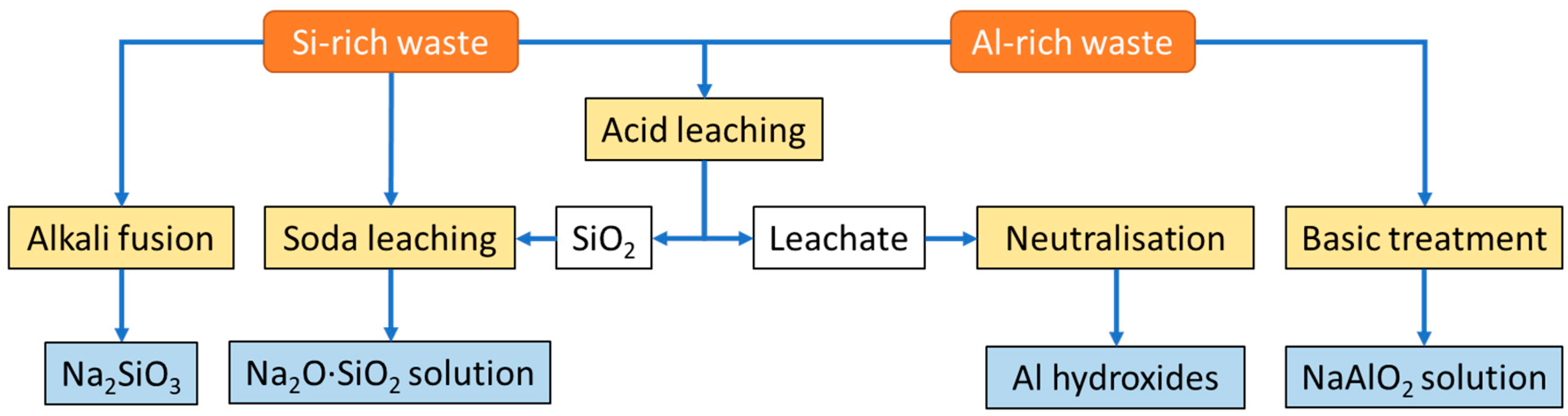

3.5.1. Generating Al- and Si-containing zeolite precursors

| Waste material | Al2O3 | SiO2 | CaO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminium scrap | Almet >90–99% | ||

| Aluminium dust | Altotal 25–40 Almet 15–25 |

6–11 | 1–4 |

| Black aluminium dross | 42–88 | 1.3–14 | 0.6–1 |

| White aluminium dross | 40–50 | ||

| Spent Fluid Catalytic Cracking catalysts | 40–50 | 40–50 | 0–1 |

| Coal combustion ashes | 15–40 | 40–60 | 3–15 |

| Aluminium salt slag | 20–30 Almet 5–10 |

2–10 | |

| Coal gasification ashes | 5–30 | 25–60 | 2–30 |

| Liquid Crystal Displays glass panel | 15–25 | 50–75 | 0–7 |

| MSW-FA | 5-24 | 12-41 | 15–50 |

| Electric furnace steel reduction slag | 15–20 | 15–20 | 50–60 |

| Lithium slag | 15–20 | 50–55 | 10–12 |

| Red mud from the Bayer process (dried) | 10–20 | 3–50 | 2–40 |

| Drilling and cutting muds (dried) | 5–20 | 30–70 | 2–30 |

| MSW-BA | 1–20 | 5–50 | 10–50 |

| Waste porcelain | 19 | 70 | 3 |

| Blast furnace iron slag | 10–15 | 30–40 | 40–50 |

| Wood ash | 0.5–15 | 10–70 | 10–70 |

| Waste foundry sand | 0–15 | 75–90 | 0–5 |

| Palm oil fuel ash (POFA) | 0.5–12 | 45–75 | 3–15 |

| Zinc slag | 7–10 | 15–20 | 15–20 |

| Electric furnace steel oxidation slag | 5–10 | 10–15 | 20–25 |

3.5.2. Specific leaching of salt and heavy metals

4. Targeted sorption of cations

4.1. Zeolites as cation exchange resins

| Structure | Chemistry | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zeolite | FTC | Window | Si/Al | Cation | CEC |

| Å | mol/mol | - | meq/g | ||

| Natural zeolites | |||||

| Clinoptilolite | HEU | 3.1x7.5 | 4.0-5.7 | Na, K, Ca | 2.0-2.6 |

| Chabazite | CHA | 3.8 | 1.4-4.0 | Na, K, Ca | 2.5-4.7 |

| Phillipsite | PHI | 3.8 | 1.1-3.3 | Na, K, Ca | 2.9-5.6 |

| Analcime | ANA | 1.6x4.2 | 1.5-2.8 | Na | 3.6-5.3 |

| Erionite | ERI | 3.6x5.1 | 2.6-3.8 | Na, K, Ca | 2.7-3.4 |

| Faujasite | FAU | 7.4 | 2.1-2.8 | Na, K, Mg | 3.0-3.4 |

| Ferrierite | FER | 4.2x5.4 | 4.9-5.7 | Ca | 2.1-2.3 |

| Heulandite | HEU | 3.1x7.5 | 4.0-6.2 | Na, K, Ca, Sr | 2.2-2.5 |

| Laumontite | LAU | 6.5x7.0 | 1.9-2.4 | Na, K, Mg | 3.8-4.3 |

| Synthetic zeolites | |||||

| X | FAU | 7.4 | 1.0-1.5 | - | 2.7-6.0 |

| Y | FAU | 7.4 | <3 | - | 3.9 |

| Mordenite 1 | MOR | 6.5x7.0 | 4.0-5.7 | Na, K, Ca | 2.0-2.4 |

| A | LTA | 4.1x4.5 | 1.0-3.2 | - | 3.9-5.3 |

| NaP1 | GIS | 2.9 | 1.7-3.9 | - | 2.0 |

4.2. Sorption mechanisms

4.2.1. Adsorption of heavy metals

4.2.2. Adsorption of ammonium

4.3. Factors affecting the sorption of cations

4.3.1. Framework type vs size of the cation

| Ion | Unhydrated radius |

Hydrated radius |

ΔhydG | Ion | Unhydrated radius |

Hydrated radius |

ΔhydG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Å | Å | kJ/mol | Å | Å | kJ/mol | ||

| Li+ | 0.60 | 3.82 | -475 | Cu2+ | 0.72 | 4.19 | -2010 |

| Na+ | 0.95 | 3.58 | -365 | Zn2+ | 0.74 | 4.30 | -1955 |

| K+ | 1.33 | 3.31 | -295 | Cd2+ | 0.97 | 4.26 | -1755 |

| Ca2+ | 0.99 | 4.12 | -1505 | Pb2+ | 1.32 | 4.01 | -1425 |

| NH4+ | 1.48 | 3.31 | -285 | Cr3+ | 0.64 | 4.61 | -4010 |

| NO3- | 2.64 | 3.35 | -300 | Ni2+ | 0.70 | 4.04 | -1980 |

| H2PO4- | - | 2.6 | - | ||||

| PO43- | - | 7.91 | -2765 |

| Zeolite | Origin | Si/Al | Selectivity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic zeolites | ||||

| FAU-type | Coal FA | 2.5 | Pb2+>Cu2+>Cd2+>Zn2+>Co2+ | [103] |

| NaP1 | Coal FA | 1.7 | Cr3+>Cu2+>Zn2+>Cd2+>Ni2+ | [100] |

| 4A | Coal FA | 1.32 | Cu2+>Cr3+>Zn2+>Co2+>Ni2+ | [99] |

| X | Egyptian kaolin and Na2Si2O5 | 1.15 | Pb2+>Cd2+>Cu2+>Zn2+>Ni2+ | [104] |

| A | Egyptian kaolin and Na2Si2O5 | 1.04 | Pb2+>Cd2+>Cu2+>Zn2+>Ni2+ | [104] |

| Natural zeolites | ||||

| Mordenite | Natural | 4.4-5.5 | Cu2+>Co2+≈Zn2+>Ni2+ | [105] |

| Clinoptilolite | Natural | 4.9 | Pb2+>Zn2+>Cu2+>Ni2+ | [106] |

| Clinoptilolite | Natural | 4.8 | Cu2+>Cr3+>Zn2+>Cd2+>Ni2+ | [100] |

| Clinoptilolite | Natural | 4.2 | Pb2+>Cd2+>Zn2+≈Cu2+ | [107] |

| Clinoptilolite | Natural | 2.7-5.3 | Pb2+>Ag+>Cd2+≈Zn2+>Cu2+ | [105] |

| Phillipsite | Natural | 2.4-2.7 | Pb2+>Cd2+>Zn2+>Co2+ | [107] |

| Chabazite | Natural | 2.2-2.6 | Pb2+>Cd2+>Cu2+>Zn2+>Co2+ | [107] |

| Scolecite | Natural | 1.56 | Cu2+>Zn2+>Pb2+>Ni2+>Co2+>Co2+ | [108] |

4.3.2. Cation concentration and competing ions

4.3.3. Purity of the zeolite

4.3.4. Hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity

4.3.5. Compensation cations

4.3.6. Available adsorption surface and size of the zeolite particles

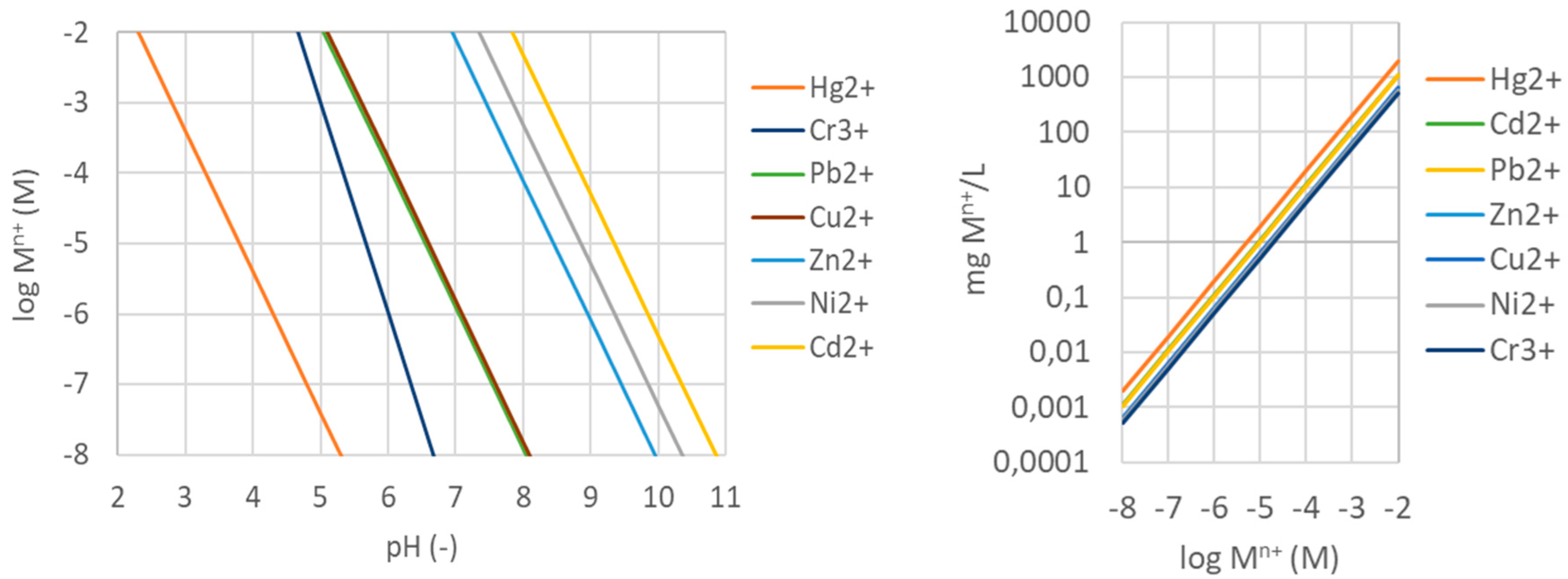

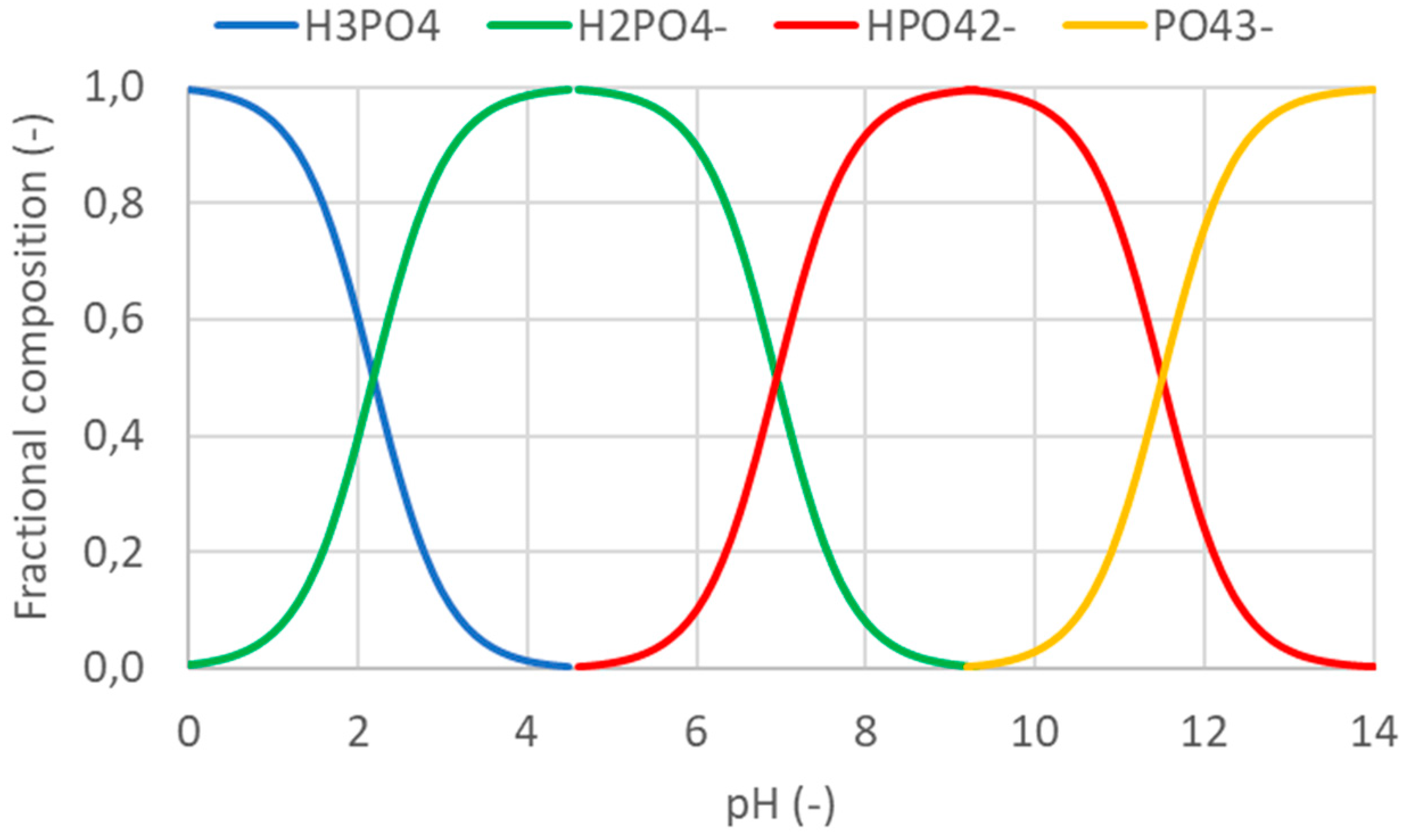

4.3.7. pH

4.3.8. Temperature

4.3.9. Contact time

5. Sorption of nitrate and phosphate using zeolites

- Lowering the pH to make the zeolite cationic

- Modifying the surface of the zeolite by cationic metal-doping or using surfactants.

5.1. pH-derived cationic zeolites

5.2. Modification of zeolites

5.2.1. Metal-doped zeolites

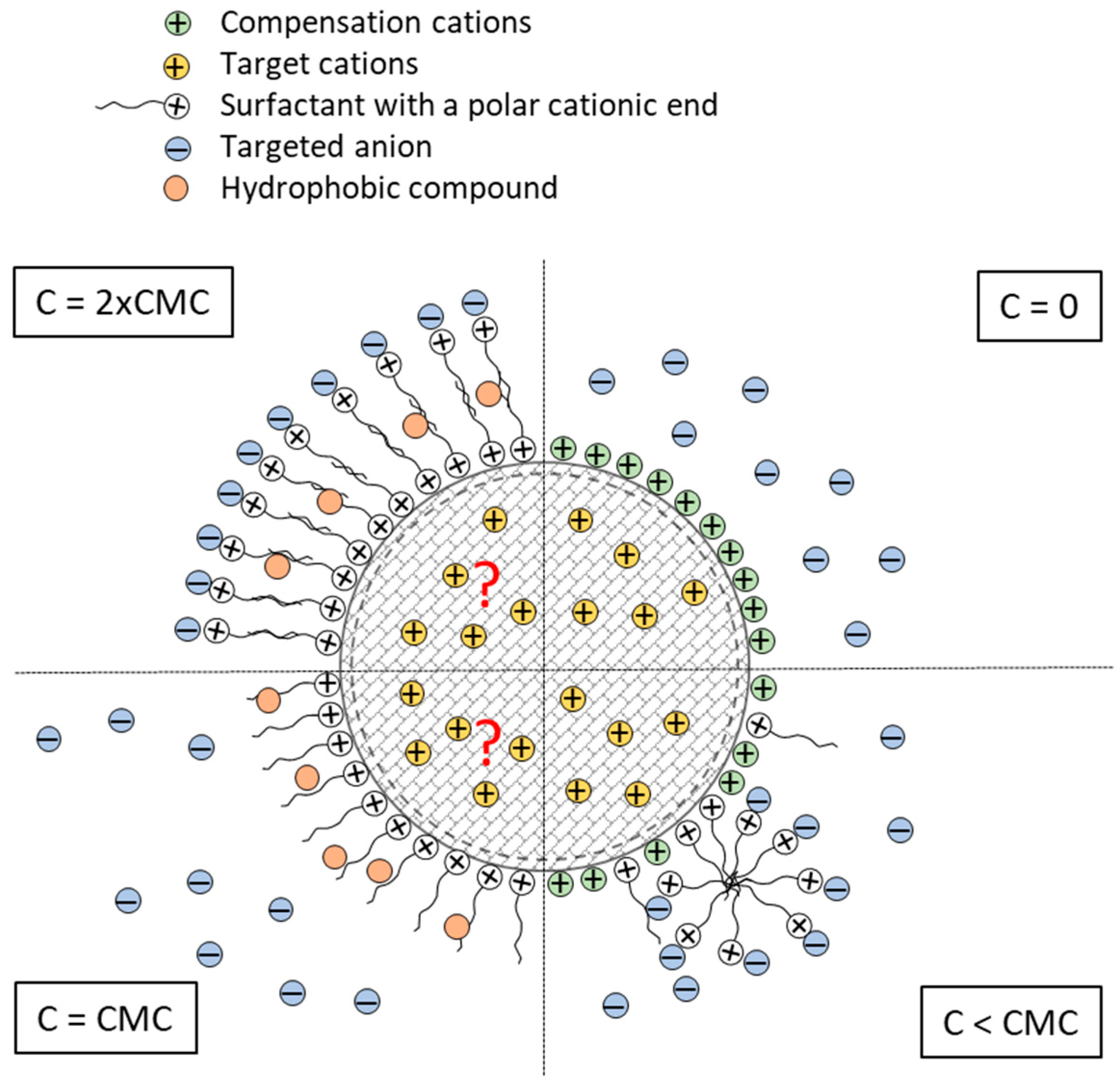

5.2.2. Surfactant-modified zeolites (SMZs)

5.2.3. Adsorption of phosphate by modified zeolites

| Zeolite | App. sorption capacity |

Conc. range |

S/L ratio | Contact time |

Temp. | pH | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg/g | mg P/L | g/L | h | oC | - | ||

| Non-modified zeolites | |||||||

| NaP1 | 11.4 | 12.5-200 | 1 | 24 | 25 | 5.3 | [125] |

| NaA | 15.7 | ||||||

| Clinoptilolite | 20.2 | ||||||

| A | 52.9 | 50-1000 | 6.6 | 4 | 70 | 5.5 | [129] |

| Clinoptilolite | 1.3 | 10-100 | 48 | 2 | 25 | 2 | [132] |

| Zeolite from coal-FA | 11.7-42.4 | 1000 | 10 | 24 | room | 3.5-9 | [127] |

| Clinoptilolite | 0.77 | 0.03-3.1 | 8 | 24 | room | 3.0 | [144] |

| NaP1-zeolite from coal-FA | 34.7 | 0.5-1000 | 10 | 24 | 18-22 | - | [126] |

| Salt-modified zeolites | |||||||

| LaP1 | 58.2 | 12.5-200 | 1 | 24 | 25 | 5.3 | [125] |

| LaA | 48.9 | ||||||

| La-clinoptilolite | 25.5 | ||||||

| TiO2-modified clinoptilolite | 34.2 | 10-100 | 20 | 2 | 25 | 2 | [132] |

| Ca-bearing K-zeolite | 142-250 | 100-16000 | 16.7 | 0.8-2.2 | 22 | 6-9 | [145] |

| Zr oxide merlinoite | 67.7 | 5-200 | 0.2-2 | 4 | 40 | <5 | [133] |

| CaP1-zeolite from coal-FA | 49.5 | 0.5-1000 | 10 | 24 | 18-22 | - | [126] |

| MgP1-zeolite from coal-FA | 31.3 | ||||||

| AlP1-zeolite from coal-FA | 29.9 | ||||||

| FeP1-zeolite from coal-FA | 30.9 | ||||||

| Cu-zeolite X | 87.7 | 10-200 | 1 | 24 | 25 | 5.0 | [146] |

| Surfactant-modified zeolites | |||||||

| HDTMA-Br clinoptilolite | 20.9 | 0.03-3.1 | 8 | 24 | room | 12.0 | [144] |

| HDP-Br clinoptilolite | 11.6 | ||||||

5.2.4. Adsorption of nitrate by surfactant-modified zeolites

| Zeolite | Surfactant | Amount adsorbed |

Conc. Range |

S/L ratio |

Contact time |

Temp. | pH | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg NO3/g | mg NO3/L | g/L | h | °C | - | |||

| Clinoptilolite | polydopamine | 2,47 | 150 | - | 0,30 | 10 | 3 | [149] |

| ZSM-5 nanocrystals | HDTMA-Br | 50 | 50-2500 | 0,5 | 24 | room | 6 | [34] |

| ZSM-5 nanosheets | HDTMA-Br | 120 | ||||||

| ZSM-5 nanosponges | HDTMA-Br | 132 | ||||||

| clinoptilolite-rich turf | HDTMA-Br | 4,96 | 124-1240 | 100 | 24 | room | - | [147] |

| Natural zeolite | HDTMA-Br | 2,42 | 5 | 0,91 | 2 | room | 7 | [150] |

| *BEA-type zeolite nanosponge | HDTMA-Br | 83 | 50-1500 | 2 | 2 min | room | 5,5 | [36] |

| *BEA-type zeolite nanocrystals | HDTMA-Br | 19 | 25 | 5 min | ||||

| Clinoptilolite-rich tuf | HDTMA-Br | 6,07 | 1-113 | 20-200 | 24 | room | 5-6 | [152] |

| Natural zeolite | CPB | 9,68 | 89 | 2 | 0,5 | 15 | 6 | [151] |

5.2.5. Leaching of surfactants – a potential setback

6. Reuse of adsorbed compounds

- Use them as they are, embedded in zeolite, typically as slow-release compounds, for instance in fertilizers.

- Recover them from the zeolite by controlled release.

6.1. Slow release of compounds from the zeolite during application

6.2. Controlled release of compounds of interest

6.2.1. Methods used to release the compounds from zeolites

| Compound | Zeolite | Release conditions | Important factors | Released compound | Desorption efficiency | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu2+ | Synthetic from FA | 0.1-0.8 M H2SO4 | High conc H2SO4 | CuSO4 | 96-102% (four cycles) | [165] |

| Ni2+ | Synthetic from FA | 0.1-0.8 M H2SO4 | High conc H2SO4 | NiSO4 | 84-98% (four cycles) | [165] |

| Cd2+ | Natural zeolites | 0.1 M HCl (54-80 bed volumes) | - | CdCl2 | 90% first cycle | [166] |

| Zn2+ | Natural zeolites | 0.1 M HCl (6-30 bed volumes) | - | ZnCl2 | 90% first cycle | [166] |

| Cr6+ | HDTMA-modified clinoptilolite-rich tuff | 0.28 M Na2CO3 and 0.5 M NaOH (L/S: 3 mL/g); regeneration with 3x 0.1 M HCl (L/S: 3 mL/g) | - | - | 90% first cycle (100% regeneration) | [158] |

| NH4+ | Alkali-treated clinoptilolite | 0.5 M HCl | - | NH4Cl | Adsorption unaffected after 12 cycles | [167] |

| NH4+ | Zeolite from FA | 1 M NaCl (3x25 mL/2 g zeolite) at 25°C for 1.25 h | - | NH4Cl | Ca. 10% loss in adsorbent capacity after one cycle | [168] |

| NH4+ | Clinoptilolite | 20 g NaCl/L for 15 h | High NaCl conc | NH4Cl | 100% (five cycles). Adsorption capacity increased from 9.2 mg/g to 10.9 mg/g (over first three cycles) | [169] |

| NH4+ | Clinoptilolite | 30 g NaCl/L (123-134 BV) | Low flow rate to get high conc | NH4Cl | 88-95% | [170] |

| NH4+ | Synthetic NaA | 30 g NaCl/L (43-46 BV) | 92-95% | |||

| NH4+ | Clinoptilolite | 10% NaCl and 0.6% NaOH | Increased desorption: 10-15% NaCl and 0-0.6% NaOH | NH3 | 100% | [164] |

| PO43- | La-doped zeolite from FA | 3 M NaOH (L/S ratio 80:1) at 250°C for 5 h | High conc NaOH (<4 M NaOH), high L/S ratio, high temp | Na3PO4 | 95% (five cycles) | [142] |

| NO3- | Polydopamin-coated clinoptilolite | 0.01 M and 0.05 M NaOH | - | NaNO3 | 59-71% (three cycles) | [149] |

| NO3- | HDTMA-modified clinoptilolite | 1 M NaBr (L/S: 5 mL/g) for 6 h | - | NaNO3 | Ca. 100% first cycle | [153] |

6.2.2. Downstream concentration and refinement

6.2.3. Regeneration of the zeolite’s adsorption capacity

7. Discussion and need for further studies

7.1. MSW-FA as a source for synthetic zeolites

7.2. Capturing efficiency

7.3. Acceptance and need of recovered end-products

8. Concluding remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoornweg, D.; Bhada-Tata, P. What a waste: a global review of solid waste management. 2012, The World Bank: Washington.

- Kaza, S.; Yao, L.; Bhada-Tata, P.; Van Woerden, F. What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050. Urban Development, 2018, Washington, DC.

- Chen, D.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Nie, Q.; Yang, Z.; Shenga, W.; Qian, G. Municipal solid waste incineration residues recycled for typical construction materials—a review. RSC Adv 2022, 12, 6279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindberg, D.; Molin, C.; Hupa, M. Thermal treatment of solid residues from WtE units: A review. Waste Management 2015, 37, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quina, M.J.; Bontempi, E.; Bogush, A.; Schlumberger, S.; Weibel, G.; Braga, R.; Funari, V.; Hyks, J.; Rasumssen, E.; Lederer, J. Technologies for the management of MSW incineration ashes from gas cleaning: New perspectives on recovery of secondary raw materials and circular economy. Sci Total Env 2018, 635, 526–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weibel, G.; Zappatini, A.; Wolffers, M.; Ringmann, S. Optimization of metal recovery from MSWI fly ash by acid leaching: findings from laboratory- and industrial-scale experiments. Processes 2021, 9, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanhar, A.H.; Chen, S.; Wang, F. Incineration fly ash and its treatment to possible utilization: A Review. Energies 2020, 13, 6681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millini, R.; Bellussi, G. Zeolite science and perspectives. In Zeolites in Catalysis: Properties and Applications, Cejka, J., Morris, R.E., Nachtigall, P. The Royal Society of Chemistry 2017; RSC Catalysis Series No. 28.

- Ray, R.L.; Sheppard, R.A. Occurrence of zeolites in sedimentary rocks: an overview, in Natural Zeolites: Occurrence, Properties, Applications. Rev. Miner. Geochem 2001, 45, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- MgBemere, H.E.; Ekpe, I.C.; Lawal, G.I. Zeolite synthesis, characterizations, and application areas - a review. Int. Res. J. Environ. Sci 2017, 6, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Khaleque, A.; Alam, M.M.; Hoque, M.; Mondal, S.; Haider, J.B.; Xuc, B.; Johir, M.A.H.; Karmakar, A.K.; Zhoud, J.L.; Ahmedb, M.B.; Moni, M.A. Zeolite synthesis from low-cost materials and environmental applications: a review. Environ. Adv 2020, 2, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, B.H.; Nam, B.H.; An, J.; Youn, H. Municipal Solid Waste Incineration (MSWI) Ashes as Construction Materials-A Review. Materials 2020, 13(14), 3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perego, C.; Bagatin, R.; Tagliabue, M.; Vignola, R. Zeolites and related mesoporous materials for multi-talented environmental solutions. Microp. Mesop. Mater 2013, 166, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlfeldt Fedje, K.; Rauch, S.; Cho, P.; Steenari, B.M. ; Element associations in ash from waste combustion in fluidized bed. Waste Manag 2010, 30(7), 1273–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witek-Krowiak, A.; Gorazda, K.; Szopa, D.; Trzaska, K.; Moustakas, K.; Chojnacka, K. Phosphorus recovery from wastewater and bio-based waste: an overview. Bioeng 2022, 13(5), 13474–13506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordell, D. Peak phosphorous and the role of P recovery in achieving food security. In: T.A. Larsen, K.M. Udert and J. Lienert (Eds.) Source Separation and Decentralization for Wastewater Management IWA Publishing, London, 2013, 29-44.

- Jenssen, T.K.; Kongshaug, G. Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Fertiliser Production. Proceeding No. 509, The International Fertilizer Society, 2003.

- European Commission Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL concerning urban wastewater treatment (recast) 541, 2022.

- van Eekert, M.; Weijma, J.; Verdoes, N.; de Buisonjé, F.; Reitsma, B.; van den Bulk, J.; van Gastel, J. Explorative research on innovative nitrogen recovery. STOWA Report 51 2012, Stichting Toegepast Onderzoek Waterbeheer, Amersfoort, The Netherlands.

- Ganrot Z.; Use of zeolites for improved nutrient recovery from decentralized domestic wastewater. Chapter 17 in Vassilis J.; Antonis, A.Z.; (Eds) Handbook of Natural Zeolites 2012, 410-435.

- Bandala, E.R.; Liu, A.; Wijesiri, B.; Zeidman, A.B.; Goonetilleke, A. Emerging materials and technologies for landfill leachate treatment: A critical review. Environ. Poll. 2021, 291, 118133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrel-Luna, R.; García-Arreola, M.E.; González-Rodríguez, L.M.; oredo-Cancino, M.; Escárcega-González, C.E.; de Haro-Del Río, D.A. Reducing toxic element leaching in mine tailings with natural zeolite clinoptilolite. Environ. Sci. Poll. Res 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helfferich, F. Ion Exchange. Dover Publishing, 1995, New York.

- Inglezakis, V.J. The concept of “capacity” in zeolite ion-exchange systems. J. Colloid. Inter. Sci 2005, 281, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs D.S.; Alberti A.; Armbruster T.; Artioli G.; Colella C.; Galli E.; Grice J.D.; Liebau F.; Mandarino J.A.; Minato H., Nickel E.H.; Passaglia E.; Peacor D.R.; Quartieri S.; Rinaldi R.; Ross M.; Sheppard R.A., Tillmans E. and Vezzalini G., Recommended nomenclature for zeolite minerals: Report of the subcommittee on zeolites of the international mineralogical association, commission on new minerals and mineral names. Can. Mineral., 1997, 35, 1571–1606.

- Barelocher, C.; McCuster, L.B.; Olson, H.D. Atlas of zeolite framework types, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 6th Ed. 2007.

- Yu, J. Synthesis of zeolites,” in (Eds.) J. Čejka, B. Hv, A. Corma, and F. Schüth, Introduction to zeolite science and practice. Vol. 2007, 168, Elsevier, 3rd Ed.

- Brännvall, E.; Kumpiene, J. Fly ash in landfill top covers – a review. Environ. Sci. Proc. Imp 2016, 18, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundy, C.S.; Cox, P.A. The hydrothermal synthesis of zeolites: Precursors, intermediates and reaction mechanism. Review. Microp. Mesop. Mater 2005, 82, 1–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, K.; Choi, M.; Ryoo, R. Recent advances in the synthesis of hierarchically nanoporous zeolites. Review. Microp. Mesop. Mater 2013, 166, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Ma Q.; Lin Q.; Chang J.; Bao W.; Ma M.; Combined modification of fly ash with Ca(OH)2/Na2FeO4 and its adsorption of Methyl orange. App. Surf. Sci. 2015, 359, 323–330. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Ramırez, J.; Verboekend, D.; Bonilla, A.; Abello, S. Zeolite catalysts with tunable hierarchy factor by pore-growth moderators. Adv. Funct. Mater 2009, 19, 3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova I.I.; Knyazeva E.E.; Micro–mesoporous materials obtained by zeolite recrystallization: synthesis, characterization and catalytic applications. Chem. Soc. Rev 2013, 42, 3671–3688. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanache, L.E.; Sundermann, L.; Lebeau, B.; Toufaily, J.; Hamieh, T.; Daou, T.J. Surfactant-modified MFI-type nanozeolites: Super-adsorbents for nitrate removal from contaminated water. Microp. Mesop. Mater 2019, 283, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schick, J.; Daou, T.J.; Caullet, P.; Paillaud, J.L.; Patarin, J.; Mangold-Callarec, C. Surfactant-modified MFI nanosheets: a high capacity anion-exchanger. Chem. Comm 2011, 47, 902–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanache, L.E.; Lebeau, B.; Nouali, H.; Toufaily, J.; Hamieh, T.; Daou, T.J. Performance of surfactant-modified *BEA-type zeolite nanosponges for the removal of nitrate in contaminated water: Effect of the external surface. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 364, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang W.; Jia M.; Che X.; Pretreatment of municipal solid waste incineration fly ash and preparation of solid waste source sulphoaluminate cementitious material. J. Hazard. Mater 2020, 385, 121580. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., R. Cui, T. Yang, Z. Zhai, and R. Li, Distribution characteristics of heavy metals in different size fly ash from a sewage sludge circulating fluidized bed incinerator. Energy & Fuels 2017, 31(2), 2044–2051.

- Fabricius A-L.; Renner M.; Voss M.; Funk M.; Perfoll A.; Gehring F.; Graf R.; Fromm S.; Duester L. Municipal waste incineration fly ashes: from a multi-element approach to market potential evaluation. Environ. Sci. Eur 2020, 32(1), 88.

- Bodénan, F.; Deniard, P. Characterization of flue gas cleaning residues from European solid waste incinerators: assessment of various Ca-based sorbent processes. Chemosphere 2003, 51(5), 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, K.-Y.; Jih J.-C.; Chien M-D.; The acid extraction of metals from municipal solid waste incinerator products. Hydrometallurgy 2008, 93(1), 16–22. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Hao, Q.; Chen, J.; Hu, M.; Tu, T.; Jiang, C. Distribution characteristics and comparison of chemical stabilization ways of heavy metals from MSW incineration fly ashes. Waste Manage. 2020, 113, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saakshy, K.; Singh, A.B.; Gupta, Sharma, A.K. Fly ash as low cost adsorbent for treatment of effluent of handmade paper industry-Kinetic and modelling studies for direct black dye. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1227–1240. [CrossRef]

- Wesche, K. Fly ash in concrete properties and performance. RILEM Report. Ed. Hall C.A. 1990, International Union of Testing and Research Laboratories, France: London.

- Weibel, G.; Eggenberger, U.; Schlumberger, S.; Mäder, U.K. Chemical associations and mobilization of heavy metals in fly ash from municipal solid waste incineration. Waste Manag. 2017, 62, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, D.A.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Deegan, D.; Cheeseman, C.R. Air pollution control residues from waste incineration: Current UK situation and assessment of alternative technologies. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 2279–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IAWG (International Ash Working Group), Chandler, A.J.; Eighmy, T.T.; Hartlén, J.; Hjelmar, O.; Kosson, D.S.; Sawell, S.E.; van der Sloot H.; Vehlow, J.; Municipal Solid Waste Incinerator Residues. Studies Environ. Sci 1997, 67, Elsevier.

- Zhao, Y.; Li, H. Understanding municipal solid waste production and diversion factors utilizing deep-learning methods. Utilities Policy 2023, 83, 101612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A.M.; Snellings, R.; van den Heede, P.; Matthys, S.; de Belie, N. The use of municipal solid waste incineration ash in various building materials: A Belgian Point of View. Materials 2018, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng L.; Xu Q.; Wu H.; Synthesis of zeolite-like material by hydrothermal and fusion methods using municipal solid waste fly ash. Proc. Environ. Sci 2016, 31, 662–667. [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.F.; Yuan, R.; Gan, M.; Ji, Z.; Sun, Z. Subcritical hydrothermal treatment of municipal solid waste incineration fly ash: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 865, 160745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eighmy, T.T.; Eusden, J.D.; Krzanowski, J.E.; Domiago, D.S.; Stampfli, D.; Martin, P.M.; Erickson, P.M. Comprehensive approach toward understanding element speciation and leaching behavior in municipal solid waste incineration electrostatic precipitator ash. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1995, 29, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelmar, O. Disposal strategies for municipal solid waste incineration residues. J. Hazard. Mater. 1996, 47, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forestier, L.L.; Libourel, G. Characterization of flue gas residues from municipal solid waste combustors. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1998, 32, 2250–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quina, M.J.; Bordado, J.C.; Quinta-Ferreira, R.M. Treatment and use of air pollution control residues from MSW incineration: An overview. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 2097–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.J.; Kim, K.; Seo, Y.; Kim, S. ; Characteristics of ashes from different locations at the MSW incinerator equipped with various air pollution control devices. Waste Manage. 2004, 24, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavva, C.; Voutsas, E.; Magoulas, K. Process development for chemical stabilization of fly ash from municipal solid waste incineration. Chem. Eng. Res. Des 2017, 125, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Tyrer, M.; Yu, Y. Stabilization of heavy metals in MSWI fly ash using silica fume. Waste Manage. 2014, 34, 2494–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlfeldt, K.; Steenari, B.-M. Assessment of metal mobility in MSW incineration ashes using water as the reagent. Fuel 2007, 86, 1983–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, N.; Gasso, S.; Lacorte, T.; Baldasano, J.M. Characterization of municipal solid waste incineration residues from facilities with different air pollution control systems. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 1997, 47, 1170–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, M.; Rincon, J.M., Rawlings, R.D., Boccaccini, A.R. Use of vitrified urban incinerator waste as raw material for production of sintered glass–ceramics. Mat. Res. Bull. 2001, 36, 383–395. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.W.; Chen, Y.S.; Characterisation of glass–ceramics made from incinerator fly ash. Ceram. Intern 2004, 30, 343–349. [CrossRef]

- Faust, S.D.; Aly, O.M. Chemistry of water treatment. CRC press, 1988, p. 224.

- Okada, K.; Arimitsu, N.; Kameshima, Y.; Nakajima, A.; MacKenzie, K.J.D.; Preparation of porous silica from chlorite by selective acid leaching. Appl. Clay Sci 2005, 30, 116–124. [CrossRef]

- Shoppert, A.A.; Loginova, I.V.; Chaikin, L.I.; Rogozhnikov, D.A.; Alkali fusion leaching method for comprehensive processing of fly ash. KnE Mater. Sci 2017, 2, 89–96. [CrossRef]

- Sayehi, M.; Tounsi, H.; Garbarino, G.; Riani, P.; Busca, G. Reutilization of silicon- and aluminum- containing wastes in the perspective of the preparation of SiO2-Al2O3 based porous materials for adsorbents and catalysts. Waste Manag. 2020, 103, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukerche, I.; Djerada, S.; Benmansoura, L.; Tifoutia, L.; Saleh, K. Degradability of aluminum in acidic and alkaline solutions. Corros. Sci 2014, 78, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenntech. Iron Removal by physical-chemical ways. Accessed from: https://www.lenntech.com/processes/iron-manganese/iron/iron-removal-physicalchemical-way.htm.

- Zaitsev, A.I.; Shelkova, N.E.; Lyakishev, N.P.; Mogutnov, B.M. Thermodynamic properties and phase equilibria in the Na2O-SiO2 system. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 1999, 1, 1899–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adans, Y.F.; Martins, A.R.; Coelho, R.E.; das Virgens, C.F.; Ballarini, A.D.; Carvalho, L.S. A simple way to produce c-alumina from aluminum cans by precipitation reactions. Mat. Res. 2016, 19, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajima T..; Ikegami Y. Synthesis of zeolitic materials from waste porcelain at low temperature via a two-step alkali conversion. Ceram. Int. 2007, 33(7), 1269–1274. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.-S.; Chiang, K.-Y.; Lin, K.-L.; Sun, C.-J. Effects of a water-extraction process on heavy metal behavior in municipal solid waste incinerator fly ash. Hydrometall. 2001, 62, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuai, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, G.; Cui, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Xiong, Z.; Zhang, J. Speciation and leaching characteristics of heavy metals from municipal solid waste incineration fly ash. Fuel 2022, 328, 125338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorovic, J.; Ecke, H.; Lagerkvist, A. Solidification with water as a treatment method for air pollution control residues. Waste Manage 2003, 23, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasser, F.P. Fundamental aspects of cement solidification and stabilisation. Journal of Hazardous Materials 1997, 52(2–3), 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weibel, G.; Eggenberger, U.; Dmitrii, A.K.; Hummel, W.; Schlumberger, S.; Klink, W.; Fisch, M.; Mäder, U.K. Extraction of heavy metals from MSWI fly ash using hydrochloric acid and sodium chloride solution. Waste Manage. 2018, 76, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AWEL, Office for Waste Management, Environmental Protection Agency of Canton Zurich (AWEL Zurich), 2013. Stand der Technik für die Aufbereitung von Rauchgasreinigungsrückständen (RGRR) aus Kehrichtverbrennungsanlagen.

- Vassilev, S.V.; Vassileva, C.G. A new approach for the classification of coal fly ashes based on their origin, composition, properties, and behaviour. Fuel 2007, 86(10), 1490–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colella, C.; Wise, W.S. The IZA Handbook of Natural Zeolites: A tool of knowledge on the most important family of porous minerals. Microp. Mesop. Mater 2014, 189, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Magalhães, L.F.; da Silva G.R.; Peres A.C.E.; Zeolite application in wastewater treatmen. Adsorp. Sci Techn. 2022, 4544104.

- Moshoeshoe, M.; Nadiye-Tabbiruka, M.S.; Obuseng, V.A. Review of the chemistry, structure, properties and applications of zeolites. Amer. J. Mater. Sci 2017, 7(5), 196–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumpton, F.A. La roca magica: Uses of natural zeolites inagriculture and industry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 3463–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baerlocher, C.; McCusker, L.B.; Olson, D.H. Atlas of zeolite framework types. 6th Ed. Elsevier, B.V. Amsterdam.

- Yue, B.; Liu, S.; Chai, Y.; Wu, G.; Guan, N.; Li, L. Zeolites for separation: Fundamental and application. J. Ener. Chem. 2022, 71, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Botella, E.; Palomino, M.; Valencia, S.; Rey, F. In: Nanoporous materials for gas storage, Springer-Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Singapore, 2019, 173–208.

- Lin, H.; Wu, X.; Zhu, J. Kinetics, equilibrium, and thermodynamics of ammonium sorption from swine manure by natural chabazite. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2015, 51(2), 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.D.; Zhu, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Zhao, J. Removal of lead from aqueous solution by hydroxyapatite/magnetite composite adsorbent. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 165, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmuir, I. The constitution and fundamental properties of solid sand liquids. Part-I. Solids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1916, 38, 2221–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundlich, H. Colloid and Capillary Chemistry, Metheum, London, 1926, 993.

- Millar, G.J.; Winnett, A.; Thompson, T.; Couperthwaite, S.J. Equilibrium studies of ammonium exchange with Australian natural zeolites. J. Water Proc. Eng. 2016, 9, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprynskyy, M.; Buszewski, B.; Terzyk, A.P.; Namieśnik, J. Study of the selection mechanism of heavy metal (Pb2+, Cu2+, Ni2+, and Cd2+) adsorption on clinoptilolite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006, 304(1), 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugurlu, M.; Karaoglu, M.H. Adsorption of ammonium from an aqueous solution by fly ash and sepiolite: Isotherm, kinetic and thermodynamic analysis. Microp. Mesop. Mater. 2011, 139, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.D.; Zhang, M.L.; Ke, Y.Y.; Song, Y.C. Simultaneous immobilization of ammonium and phosphate from aqueous solution using zeolites synthesized from fly ashes. Water Sci. Technol. 2013, 67, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makgabutlane, B.; Nthunya, L.N.; Musyoka, N.; Dladla, B.S.; Nxumalo, E.N.; Mhlanga, S.D. Microwave assisted synthesis of coal fly ash-based zeolites for removal of ammonium from urine. RSC Adv 2020, 10, 2416–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Xu, D.; Han, L.; Niu, D.; Zhang, L.; Wu, W. Tianm B. Ammonium removal from aqueous solution by zeolites synthesized from low-calcium and high-calcium fly ashes. Desalination 2011, 277, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beler-Baykal, B.; Allar, A.D. Upgrading fertilizer production wastewater effluent quality for ammonium discharges through ion exchange with clinoptilolite. Environ. Technol. 2008, 29, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, C.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhou, S. Synthesis of zeolite P1 from fly ash under solvent-free conditions for ammonium removal from water. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Li, Y.; Yu, Z.; Shen, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Ding, T.; Xu, L.; Lee, S.S. Ammonium removal using a calcined natural zeolite modified with sodium nitrate. J. Hazard Mater 2020, 393, 122481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui K.S.; Chao C.Y.; Kot S.; Removal of mixed heavy metal ions in wastewater by zeolite 4A and residual products from recycled coal fly ash. J. Hazard. Mater 2005, 127(1-3), 89–101. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Ayuso E.; Garcia-Sanchez A.; Querol X.; Purification of metal electroplating waste waters using zeolites. Water Res 2003, 37, 4855–4862. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nightingale E.R.; Phenomenological theory of ion solvation. effective radii of hydrated ions 1959, 1381-1387.

- Marcus, Y. Thermodynamics of solvation of ions. Part 5.—Gibbs free energy of hydration at 298.15 K. Trans. 1991, 87(18), 2995–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph I., V.; Tosheva, L.; Doyle, A.M. Simultaneous removal of Cd(II), Co(II), Cu(II), Pb(II), and Zn(II) ions from aqueous solutions via adsorption on FAU-type zeolites prepared from coal fly ash. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim H.S.; Jamil, T.S.; Hegazy E.Z.; Application of zeolite prepared from Egyptian kaolin for the removal of heavy metals: II. Isotherm models. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 182(1-3), 842–847.

- Kesraoui-Ouki S.; Cheeseman C.R.; Perry R.; Natural zeolite utilization in pollution-control—a review of applications to metals effluents. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol 1994, 59, 121–126. [CrossRef]

- Oter, O.; Akcay, H. Use of natural clinoptilolite to improve, water quality: sorption and selectivity studies of lead(II), copper(II), zinc(II), and nickel(II). Water Environ. Res 2007, 79, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, D.; Pepe, F. Experiments and data processing of ion exchange equilibria involving Italian natural zeolites: a review. Microp. Mesop. Mater 2007, 105(3), 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosso, S.T.; Enzweiler, J. Evaluation of heavy metal removal from aqueous solution onto scolecite. Water Res 2002, 36, 4795–4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Dhar, B.R.; Elbeshbishy, E.; Lee, H.S. Ammonium nitrogen removal from the permeates of anaerobic membrane bioreactors: economic regeneration of exhausted zeolite. Environ. Technol. 2014, 35, 2008–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, B.-B.; Ban, Z.; Byden, S. Nutrient recovery from human urine by struvite crystallization with ammonia adsorption on zeolite and wollastonite. Biores. Technol. 2000, 73, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Niu, Y.; Hu, X.; Xi, B.; Peng, X.; Liu, W.; Guan, W.; Wang, L. Removal of ammonium ions from aqueous solutions using zeolite synthesized from red mud. Desal. Water Treat 2016, 57(10), 4720–4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin, E.; Scapinello, J.; de Oliveira, M.; Rambo, C.L.; Franscescon, F.; Freitas, L.; Maria, J.; de Mello, M.; Fiori, M.A.; Oliveira, J.V.; Dal Magro, J. Adsorption of heavy metals from wastewater graphic industry using clinoptilolite zeolite as adsorbent. Proc. Safe. Environ. Prot 2017, 105, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Bosco, S.M.; Jimenez, R.S.; Carvalho, W. Removal of toxic metals from wastewater by Brazilian natural scolecite. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci 2005, 281(2), 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćurković, L.; Cerjan-Stefanović, Š.; Filipan, T. Metal ion exchange by natural and modified zeolites. Water Res 1997, 31(6), 1379–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margeta, K.; Zabukovec, N.; Siljeg, M.; Farkas, A. Natural zeolites in water treatment–how effective is their use. Water Treat 2013, Chapter 5.

- Haji, S.; Al-Buqaishi, B.A.; Bucheeri, A.A.; Bu-Ali, Q.; Al-Aseeri, M.; Ahmed, S. The dynamics and equilibrium of ammonium removal from aqueous solution by Na-Y zeolite. Desal. Water Treat 2016, 57(40), 18992–19001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, K.S.; Abney, M.B.; LeVan, M.D. ; CO2 adsorption in Y and X zeolites modified by alkali metal cation exchange. Micropor Mesopor Mater 2006, 91, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabo, J.A.; Schoonover, M.W. Early discoveries in zeolite chemistry and catalysis at Union Carbide, and follow-up in industrial catalysis. Appl. Catal. A 2001, 222, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujnova, A.; Lesny, J. Sorption characteristics of zinc and cadmium by some natural, modified, and synthetic zeolites. Electron. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol 2004, 59, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Inglezakis, V.J.; Loizidou, M.M.; Grigoropoulou, H.P. Ion exchange studies on natural and modified zeolites and the concept of exchange site accessibility. J. Colloid Inter. Sci 2004, 275(2), 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, A.H.; Kaya, A. Factors affecting adsorption characteristics of Zn2+ on two natural zeolites. J Hazard Mater 2006, 131(1-3), 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmulski, M. The pH dependent surface charging and points of zero charge. VII. Update. Adv. Colloid Inter. Sci 2018, 251, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmulski, M. The pH dependent surface charging and points of zero charge. VIII. Update. Adv. Colloid Inter. Sci 2020, 275, 102064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monhemius, A.J. Precipitation diagrams for metal hydroxides, sulphides, arsenates and phosphates. Trans. Inst. Min. Metall 1977, 6, 203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Goscianska, J.; Ptaszkowska-Koniarz, M.; Frankowski, M.; Franus, M.; Panek, R.; Franus, W. Removal of phosphate from water by lanthanum-modified zeolites obtained from fly ash. J. Colloid Inter. Sci 2018, 513, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.Y.; Zhang, B.H.; Li, C.J.; Zhang, Z.J.; Kong, H.N. Simultaneous removal of ammonium and phosphate by zeolite synthesized from fly ash as influenced by salt treatment. J. Colloid Inter. Sci 2006, 304(2), 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.G.; Kong, H.N.; Wu, D.Y.; Hu, Z.B.; Wang, Z.S.; Wang, Y.H. Removal of phosphate from aqueous solution by zeolite synthesized from fly ash. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006, 300(2), 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylward G.H.; Findlay T.J.V.; SI Chemical Data, 2nd Ed. 1974, John Wiley & Sons.

- Hamdi, N.; Srasra, E. Removal of phosphate ions from aqueous solution using Tunisian clays minerals and synthetic zeolite. J. Environ. Sci. 2012, 24(4), 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.H.; Wu, D.Y.; Wang, C.; He, S.B.; Zhang, Z.J.; Kong, H.N. Simultaneous removal of ammonium and phosphate by zeolite synthesized from coal fly ash as influenced by acid treatment. J. Environ. Sci. 2007, 19, 540–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kou, X.; Lu, H.; Lv, X. The feasibility of adopting zeolite in phosphorus removal from aqueous solutions. Desal. Water Treat. 2014, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshameri A.; Yan C.; Lei X.; Enhancement of phosphate removal from water by TiO2/Yemeni natural zeolite: Preparation, characterization and thermodynamic. Micropor. Mesopor Mater 2014, 196, 145–157. [CrossRef]

- Ciesla, J.; Franus, W.; Franus, M.; Kedziora, K.; Gluszczyk, J.; Szerement, J.; Jozefaciuk, G. Environmental-friendly modifications of zeolite to increase its sorption and anion exchange properties. Physicoch. Stud. Modi. Mater 2019, 12, 3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi, N.; Saffar-Dastgerdi, M.H. Zeolite nanoparticle as a superior adsorbent with high capacity: Synthesis, surface modification and pollutant adsorption ability from wastewater. Microchem. J 2019, 145, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiderska-Dabrowska R.; Schmidt R.; Sikora A. Effect of calcination temperature on chemical stability of zeolite modified by iron ions. In Polish Environ. Eng. 2012; Environmental Engineering Committee PAS, Ed.; Environmental Engineering Committee PAS: Lublin, Poland, 2012, 307–317.

- Glassman, H.N. ; Surface active agents and their application in bacteriology. Bacteriol. Rev. 1948, 12, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeve, P.J.; Fallowfield, H.J. Natural and surfactant modified zeolites: A review of their applications for water remediation with a focus on surfactant desorption and toxicity towards microorganisms. J. Environ. Manag 2018, 205, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivankovic, T.; Hrenovic, J. Surfactants in the environment. Arch. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol 2010, 61, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Sorption kinetics of hexadecyltrimethylammonium on natural clinoptilolite. Langmuir 1999, 15, 6438–6445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, R.S. Applications of surfactant-modified zeolites to environmental remediation. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater 2003, 61, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez-Alvarado, M.D.; Olguín, M.T. Surfactant-modified clinoptilolite-rich tuff to remove barium (Ba2+) and fulvic acid from mono- and bi-component aqueous media. Micropor. Mesopor Mater 2011, 139, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wang, Z.; Fang, D.; Li, C.; Wu, D. Green synthesis of a novel hybrid sorbent of zeolite/lanthanum hydroxide and its application in the removal and recovery of phosphate from water. J. Colloid Inter. Sci. 2014, 423, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellaoui, Y.; Oualid, H.A.; Hsini, A.; Ibrahimi, B.E.; Laabd, M.; Ouardi, M.E.; Giácoman-Vallejos, G.; Gamero-Melo, P. Synthesis of zirconium-modified Merlinoite from fly ash for enhanced removal of phosphate in aqueous medium: Experimental studies supported by Monte Carlo/SA simulations. Chem. Eng. Journ 2021, 404, 126600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghash, A.; Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, A. Comparison of the efficiency of modified clinoptilolite with HDTMA and HDP surfactants for the removal of phosphate in aqueous solutions. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 31, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermassi, M.; Valderrama, C.; Font, O.; Moreno, N.; Querol, X.; Batis, N.; Cortina, J. Phosphate recovery fromaqueous solution by K-zeolite synthesized from fly ash for subsequent valorisation as slow release fertilizer. Sci. Total Environ 2020, 731, 139002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokrzycki, J.; Fedyna, M.; Marzec, M.; Szerement, J.; Panek, R.; Klimek, A.; Bajda, T.; Mierzwa-Hersztek, M. Copper ion-exchanged zeolite X from fly ash as an efficient adsorbent of phosphate ions from aqueous solutions. J. Environ. Chem. Engin 2022, 10, 108567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Willims, C.; Roy, S.; Bowman, R.S. Desorption of hexadecyltrimethylammonium from charged mineral surfaces. Environ. Geosc 2017, 10(1), 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gennaro, B.; Catalanotti, L.; Bowman, R.S.; Mercurio, M. Anion exchange selectivity of surfactant modified clinoptilolite-rich tuff for environmental remediation. J. Colloid Inter. Sci 2014, 430, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouran-Orimi, R.; Mirzayi, B.; Nematollahzadeh, Al.; Tardast, A. Competitive adsorption of nitrate in fixed-bed column packed with bio-inspired polydopamine coated zeolite. J. Environ. Chem. Eng 2018, 6, 2232–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Huang, X.; Chang, J.; Li, B.; Bai, Y.; Su, B.; Shi, L.; Dong, Y. Improving sludge settling performance of secondary settling tank and simultaneously adsorbing nitrate and phosphate with surfactant modified zeolite (SMZ) ballasted flocculation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng 2023, 11, 109650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhu, Z. Removal of nitrate from aqueous solution using cetylpyridinium bromide (CPB) modified zeolite as adsorbent. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 186, 1972–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schick, J.; Caullet, P.; Paillaud, J.-L.; Patarin, J.; Mangold-Callarec, C. Batch-wise nitrate removal from water on a surfactant-modified zeolite. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 2010, 132, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schick, J.; Caullet, P.; Paillaud, J.-L.; Patarin, J.; Mangold-Callarec, C. Nitrate sorption from water on a Surfactant-Modified Zeolite. Fixed-bed column experiments. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 2011, 142, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Roy, S.J.; Zou, Y.; Bowman, R.S. Long-Term chemical and biological stability of surfactant-modified zeolite. Environ. Sci. Technol 1998, 32, 2628–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrenovic, J.; Rozic, M.; Sekovanic, L.; Anic-Vucinic, A. Interaction of surfactant-modified zeolites and phosphate accumulating bacteria, J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 156, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Chromate transport through surfactant-modified zeolite columns. Ground Water Monit. Rem 2006, 26, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hong, H. Retardation of chromate through packed columns of surfactant-modified zeolite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 162, 1487–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Bowman, R.S. Retention of inorganic oxyanions by organo-kaolinite. Wat. Res 2001, 35(16), 3771–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nye, J.V.; Guerin, W.F.; Boyd, S.A. Heterotrophic activity of microorganisms in soils treated with quaternary ammonium compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol 1994, 28, 944–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrenovic, J.; Ivankovic, T. Toxicity of anionic and cationic surfactant to Acinetobacter junii in pure culture Cent. Eur. J. Biol 2007, 2, 405–414. [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo, E.; Salvi, L.; Paoli, F.; Fucile, M.; Masciandaro, G.; Manzi, D.; Masini, C.M.; Mattii, G.B. Application of zeolites in agriculture and other potential uses: a review. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pond, W.G.; Mumpton, F.A. Zeo-agriculture - use of natural zeolites in agriculture and aquaculture. Westview Press, 1984, Brockport, New York.

- Li, Z. Use of surfactant-modified zeolite as fertilizer carriers to control nitrate release. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater 2003, 61, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Prigent, B.; Geißen, S.-U. Adsorption and regenerative oxidation of trichlorophenol with synthetic zeolite: Ozone dosage and its influence on adsorption performance. Chemosphere 2016, 154, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sireesha, S.; Agarwal, A.; Sopanrao, K.S.; Sreedhar, L.; Anitha, K.L. Modified coal fly ash as a low-cost, efficient, green, and stable adsorbent for heavy metal removal from aqueous solution. Biomass Conv Bioref 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batjargal, T.; Yang, J.-S.; Kim, D.-H.; Baek, K. Removal Characteristics of Cd(II), Cu(II), Pb(II), and Zn(II) by Natural Mongolian Zeolite through Batch and Column Experiments. Sep. Sci. Technol 2011, 46(8), 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan N.S., Mowatt C., Adriano D.C. and Blennerhassett J.D. Removal of ammonium ions from fellmongery effluent by zeolite. Comm. Soil Sci. Plant Anal 2003, 34, 1861–1872. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Xu, D.; Han, L.; Niu, D.; Tian, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Wu, W. Removal of ammonium from aqueous solutions using zeolite synthesized from fly ash by a fusion method. Desalination 2011, 271, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadag, D.; Tok, S.; Akgul, E.; Turan, M.; Ozturk, M.; Demir, A. Ammonium removal from sanitary landfill leachate using natural G¨ordes clinoptilolite. J. Hazard. Mater 2008, 153, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malovanyy, A.; Sakalova, H.; Yatchyshyn, Y.; Plaza, E.; Malovanyy, M. Concentration of ammonium from municipal wastewater using ion exchange process. Desalination 2013, 329, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorick, D.; Ahlström, M.; Grimvall, A.; Harder, R. Effectiveness of struvite precipitation and ammonia stripping for recovery of phosphorus and nitrogen from anaerobic digestate: a systematic review. Environ Evid 2020, 9(27), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang J.-C.; Shang C. Air stripping. In Handbook of Environmental Engineering. Vol. 4: Advanced Physicochemical Treatment Processes. Edited by: Wang, L.L.; Hung Y.-T.; Shammas N.K. The Humana Press Inc. 2006, Totowa, NJ.

- Katehis, D.; Diyamandoglu, V.; Fillos, J. Stripping and recovery of ammonia from centrate of anaerobically digested biosolids at elevated temperatures. Water Environ. Res. 1998, 70, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Değermenci, N.; Yildiz, E. Ammonia stripping using a continuous flow jet loop reactor: mass transfer of ammonia and effect on stripping performance of influent ammonia concentration, hydraulic retention time, temperature, and air flow rate. Environ. Sci. Poll. Res 2021, 28, 31462–31469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, H.; Xie, S.; Liu, S.; Xu, L. Physical and chemical regeneration of zeolitic adsorbents for dye removal in wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 2006, 65(1), 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvador, F.; Martin-Sanchez, N.; Sanchez-Hernandez, R.; Sanchez-Montero, M.J.; Izquierdo, C. Regeneration of carbonaceous adsorbents. Part I: Thermal Regeneration. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater 2015, 202, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Shi, T.B.; Jia, C.Z.; Ji, W.J.; Chen, Y.; He, M.Y. Adsorptive removal of aromatic organosulfur compounds over the modified Na-Y zeolites. App. Catal. B: Environ 2008, 82(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, H.; Izumi, J.; Sagehashi, M.; Fujii, T.; Sakoda, A. Decomposition of trichloroethene on ozone-adsorbed high silica zeolites. Water Res 2004, 38(1), 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-G.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, C.-H. ; Adsorption and thermal regeneration of acetone and toluene vapors in dealuminated Y-zeolite bed. Sep. Pur. Technol. 2011, 77(3), 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, L.; Catarino, A.S.; Eder, P.; Litten, D.; Luo, Z.; Villanueva, A. End-of-Waste Criteria. EUR – Scientific and Technical Research series, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research, Market Analysis Report: Zeolite Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Application (Catalyst, Adsorbent, Detergent Builder), By Product (Natural, Synthetic), By Region (North America, Europe, APAC, CSA, MEA), And Segment Forecasts, 2022 – 2030. Report 978-1-68038-601-1, pp. 114.

- Markets and Markets, Market Research report: Zeolites market by type (natural, synthetic), function (ion-exchange, catalyst, molecular sieve), synthetic zeolites application (detergent, catalyst), natural zeolites application, and regional-global forecast to 2026. Report CH 8006, 2021.

- Coherent Market Insights (2023) Nutrient Recycling Market. Report CM15972, 154.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).