Introduction

The kipping handstand push-up (kHSPU) is an exercise unique to CrossFit, and is hotly debated in terms of usefulness and safety. This exercise consists of first performing a back-facing handstand against a wall. The athlete then lowers their body until their head lands on the floor (typically on a pad). The legs are flexed into an upside-down squat position, and then forcibly pushed upwards to gather vertical momentum (this is called the "kip"). The kip is coordinated with pressing or pushing the body vertically back into the handstand position. Videos of kHSPUs are readily available on the internet by searching "kipping handstand push-up."

While there is much controversy about the safety of kHSPUs, there are no data to support whether the exercises are safe or not. Because the exercises involve the head impacting the floor on each repetition, the chief concern is the neck. However, there has been no study of the forces involved in kHSPUs, or the symptoms, if any, secondary to performing them. The incidence of neck injuries in CrossFit is reported to be 3-10% of all injuries,1-4 but there are no published details regarding the type or severity of the neck injuries that occur secondary to CrossFit training.

There are limited data on forces to the head during headstands and possible short- or long-term effects of this loading. Hector and Jensen measured the forces on the head during headstands (Sirsasana pose) and reported that participants placed 40-48% of their body weight on their heads when stable.5 The only other possibly relevant data come from studies of people who carried loads on their heads for employment.6-9 Not surprisingly, these studies show that chronic load bearing on the head leads to premature cervical spinal degeneration, and that it seems independent of the weight carried (10-100 Kg).7

There are more than 5 million CrossFit participants worldwide, thus safety information could potentially affect a large population. In this paper we provide the first analysis of the forces exerted on the head during kSHPUs.

Materials and Methods

The primary outcome of this study was to characterize the axial forces on the head during kHSPUs. These forces were directly measured using force platforms (described below). To assess factors that may contribute to neck injury, video recordings were made of the head during the exercises. The number of final participants was not set until the variability of the data was known. We stopped recruitment when the data appeared representative of the population performing kHSPUs.

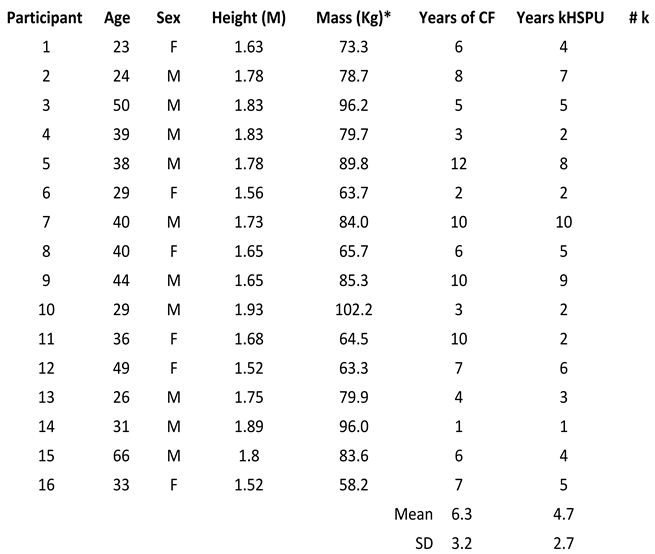

The protocol for this study was approved by the Bove Consulting Institutional Review Board (#2022-01). We recruited 16 participants from a single CrossFit gym by word of mouth and by notices placed in the gym. Inclusion criteria included the willingness to participate, being at least 18 years old, and having the ability to perform at least 2 kHSPUs. Participants included 6 female and 10 male adults, ranging from 23 to 66 years old (

Table 1). Most participants were advanced in terms of how long they had been attending any CrossFit gym, how long they had been able to perform kHSPUs, and how many they could perform. The investigator explained the procedures to each participant, and gave each an approved consent form to read and sign prior to beginning participation. Questions were asked about performance of kHSPUs and other exercises, and if they had neck pain or headaches associated with kHSPUs.

Two force platforms (PASPORT, PASCO, USA) and one plywood platform were covered with 5 cm thick foam cushions and covered with heavy polyester fabric. The density of the foam and the covering were similar to the exercise mats used by most athletes when performing this exercise. The platforms were positioned to measure the forces experienced by the head and by the right hand. Platforms were placed level and in the same plane, slightly offset so that the head and hands would land close to their centers. The force platforms were connected to a bridge amplifier (SPARKlink® Air, PASCO, USA), which was connected to a computer running Capstone software (PASCO, USA). The accuracy and precision of the measurements were confirmed using manufacturer's instructions. Video recordings focused on the head of each participant were made using the camera of an iPhone 10 to track movement of the head during the kHSPUs. The device was placed on a tripod 20 cm from the floor and took 30 frames per second.

Participants were asked to warm up as they felt was appropriate, before starting. When ready, the participant stood on the middle platform for at least 5 seconds to measure their weight. Then the participant went into a handstand for at least 5 seconds to obtain a stable force measurement. They then to descended into a headstand for at least 5 seconds to obtain a stable force measurement. The subjects then returned to standing. When ready, the participants performed 3 sets of up to 7 kHSPUs (maximum 21 repetitions), with rests between sets as desired. Data were collected at 1kHz and saved for offline analysis.

We imported data into Spike 2 (CED, UK) for analysis. The peak forces exerted by the head on the force platforms and the event times were collected for each kHSPU using the cursors supplied with the program (

Figure 1A). Because the more detailed methods of data extraction used were largely developed while analyzing the data, they are considered results and are presented in that section. We imported video recordings into Kinovea 0.9.5

10 for analysis. Statistical analyses and graphing were performed using Prism 9.5 using statistical tests appropriate for the form of the data, and included ANOVA, Spearman t-tests, Spearman r, Fisher’s exact tests, and Mann-Whitney tests. Because the purpose of this report does not include statistical comparison of participants, post-hoc tests are not reported with the ANOVA analyses. For all comparisons, 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

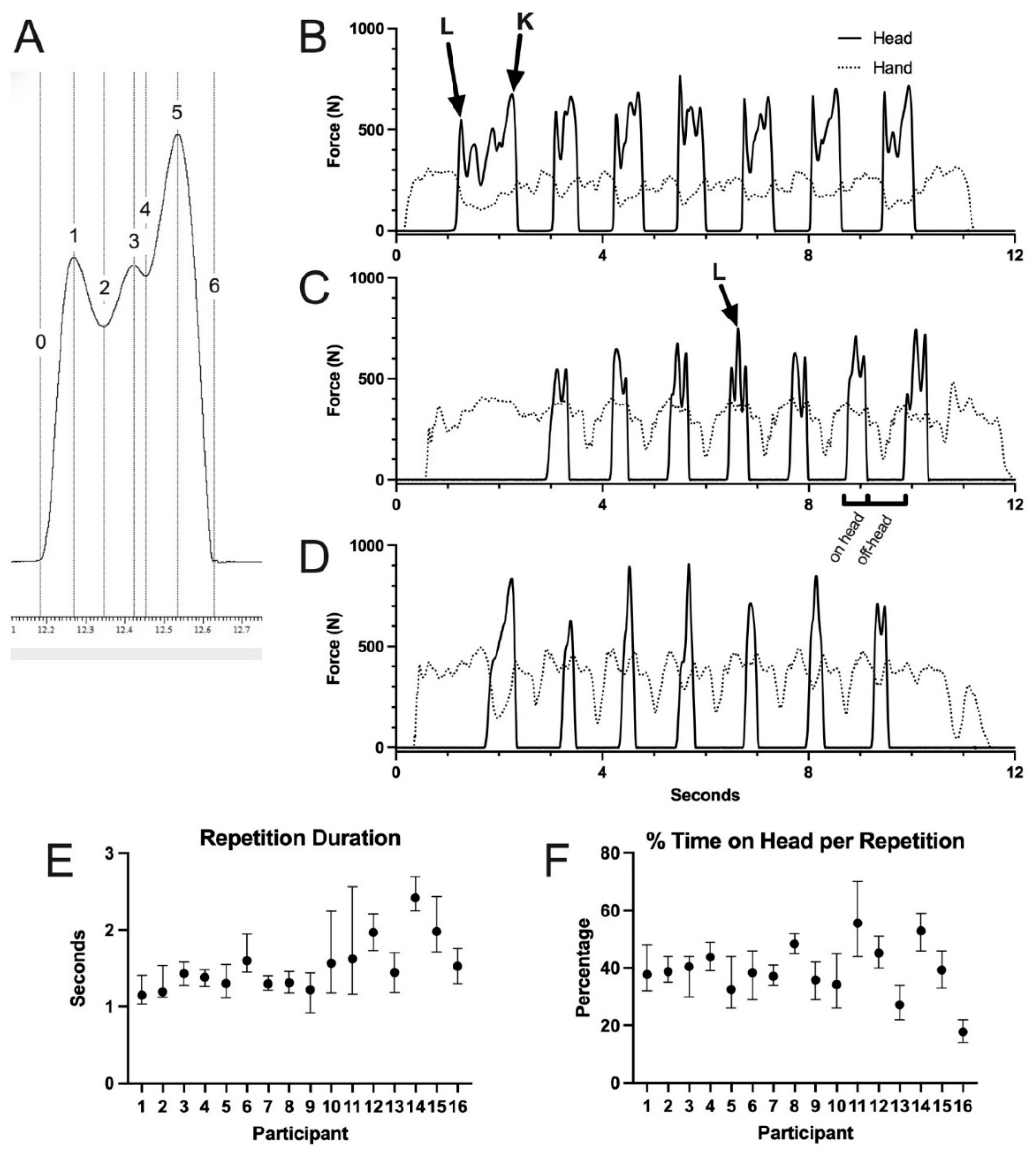

Twelve participants completed 21 kHSPU repetitions, with the others completing 15, 17, 18, and 20 repetitions. We recorded the force profiles of 322 kHSPUs. The force profiles were surprisingly complex (

Figure 1). The first force peak occurred when the head initially contacted the pad (

Figure 1A, arrow "L"), which we called the "landing force." The last force peak was when the participant "kipped," the process by which the legs were actively drawn towards the chest (reducing the force on the head) and then forcibly pushed upwards for momentum (increasing the force on the head;

Figure 1A, arrow "K"). We called this peak the "kip force." In 60% of the recordings, more peaks could be seen (

Figure 1 A-B). These peaks were more pronounced in participants who were more deliberately bringing their legs into kipping position to ready themselves for the kip (confirmed using other full body video recordings). When present, the higher of the two was recorded as the landing force (

Figure 1B, arrow "L"). Peaks also occurred due to rebound of the entire body or more mobile parts of the body, and if later in the repetition, could occur because of unloading some weight from the wall (while on the head, the posterior pelvis rests against the wall) or because of impact of the heels on the wall before the unloading was complete. These forces were not reported. When only two clear peaks were discernable (30% of recordings), they were recorded as the landing and kip forces. When only one peak was discernable (10% of the recordings), as in

Figure 1C for 6 of 7 repetitions, it was recorded as the kip force. Repetition durations were calculated by combining one duration on the head and one adjacent duration off the head (see

Figure 1B). Most participants showed consistent total repetition durations and percent of that duration on the head (

Figure 1D-E), but there were significant differences between participants (total repetition durations F

(15, 69) = 52.8,

p < 0.001; % repetition duration on head F

(15,100) = 70.1,

p < 0.001).

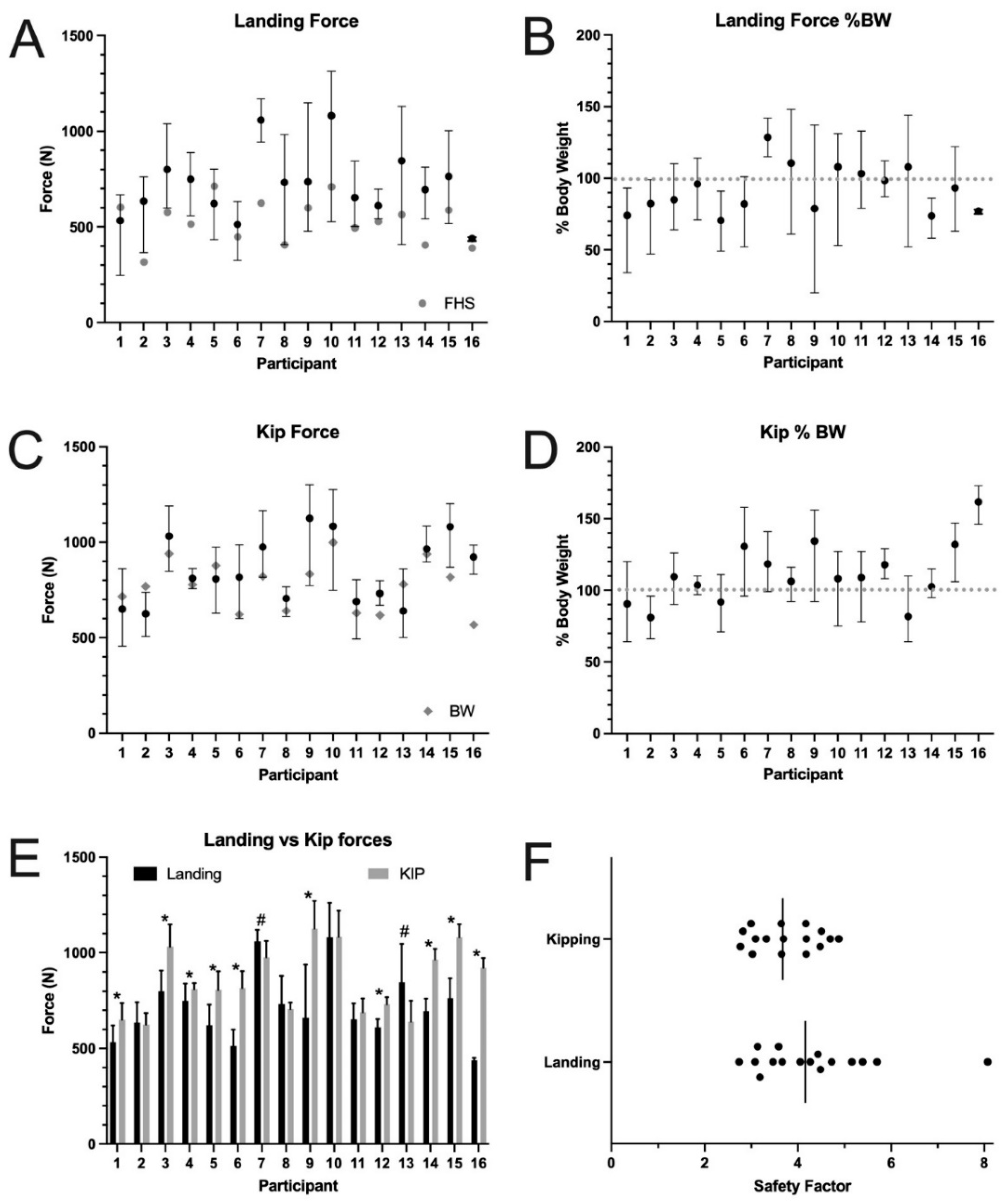

Participants placed 69% (12.5 SD) of their body weight on their head during the headstand performed prior to the kHSPUs. The mean landing forces, with ranges to show the maximum and minimum forces, are shown for each participant in

Figure 2A, and are expressed as a percentage of body weight in

Figure 2B. The landing forces were more than the measured headstand force, but typically less than their body weight. The mean peak landing force (n = 16, Fig 2A, top of range bars) was 896 kN (SD = 232 kN). There was a statistically significant difference in mean landing force between participants by non-parametric ANOVA (F

(15, 137) = 37.7,

p < 0.001). The mean landing forces were positively correlated to body weight (Spearman r = 0.67,

p <0.05).

The kipping forces are similarly depicted (

Figure 2C-D). The kipping forces were typically higher than the body weight. The mean kipping forces were statistically significantly higher than the landing forces for 10, lower for 2, and not different for 4 participants (Spearman t-tests;

Figure 2E). The mean peak kipping force (n = 16,

Figure 2C, top of range bars) was 991 kN (SD = 189 kN). Kipping forces differed between participants (F

(15,189) = 81.4,

p < 0.001), and were also positively correlated to body weight (r = 0.57,

p <0.05).

The published literature taken together support that 3.6 - 4kN is the tolerance of the healthy young male cervical spine to catastrophic injury

11,12 (but see discussion below). To estimate safety factors for this exercise in terms of cervical spine damage, we calculated the ratio of the mean peak forces to 3.6 kN. The mean safety factor was 4.3 (SD 1.3) for landing and 3.8 (SD 0.7) for kipping (

Figure 2F).

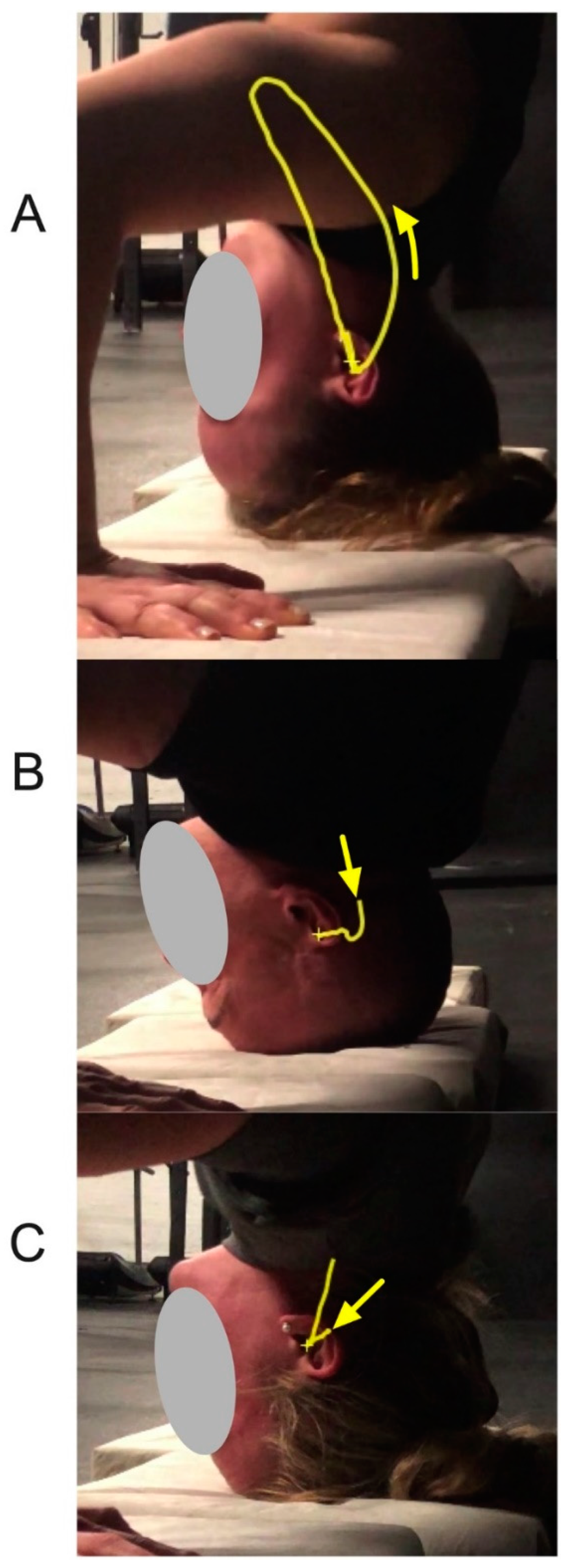

During at least two repetitions, the path of the external acoustic meatus was tracked, paying particular attention to the path during the weight-bearing phase of the exercise. Most participants (n = 10) had minimal to no head movement during the load-bearing part of the kHSPU, and showed a characteristic elliptical movement of the head (as indicated by the external acoustic meatus) during each repetition (

Figure 3A). None of these participants reported pain related to kHSPUs. However, the other 6 participants showed movement into extension during loadbearing (4 during the landing impact (

Figure 3B) and 2 during the kip (

Figure 3C)).

Five of the 16 participants (31%) reported having neck stiffness, pain, and/or headaches following kHSPUs. All 5 showed neck movement during the head load-bearing phase (

Figure 3 B-C). A Fisher’s exact test showed a significant association between the report of pain and movement during the loadbearing phase (

p = 0.001) with a positive predictive value of 0.83. There was no relationship between the presence or absence of reported pain and mean duration on the head (Mann-Whitney test,

p = 0.712). The participants were separated into groups by the presence (n=5) or absence (n=11) of symptoms after performing kHSPUs, and the force data were compared. There were no statistically significant differences between these groups in landing or kip forces (raw or %BW), or duration on the head.

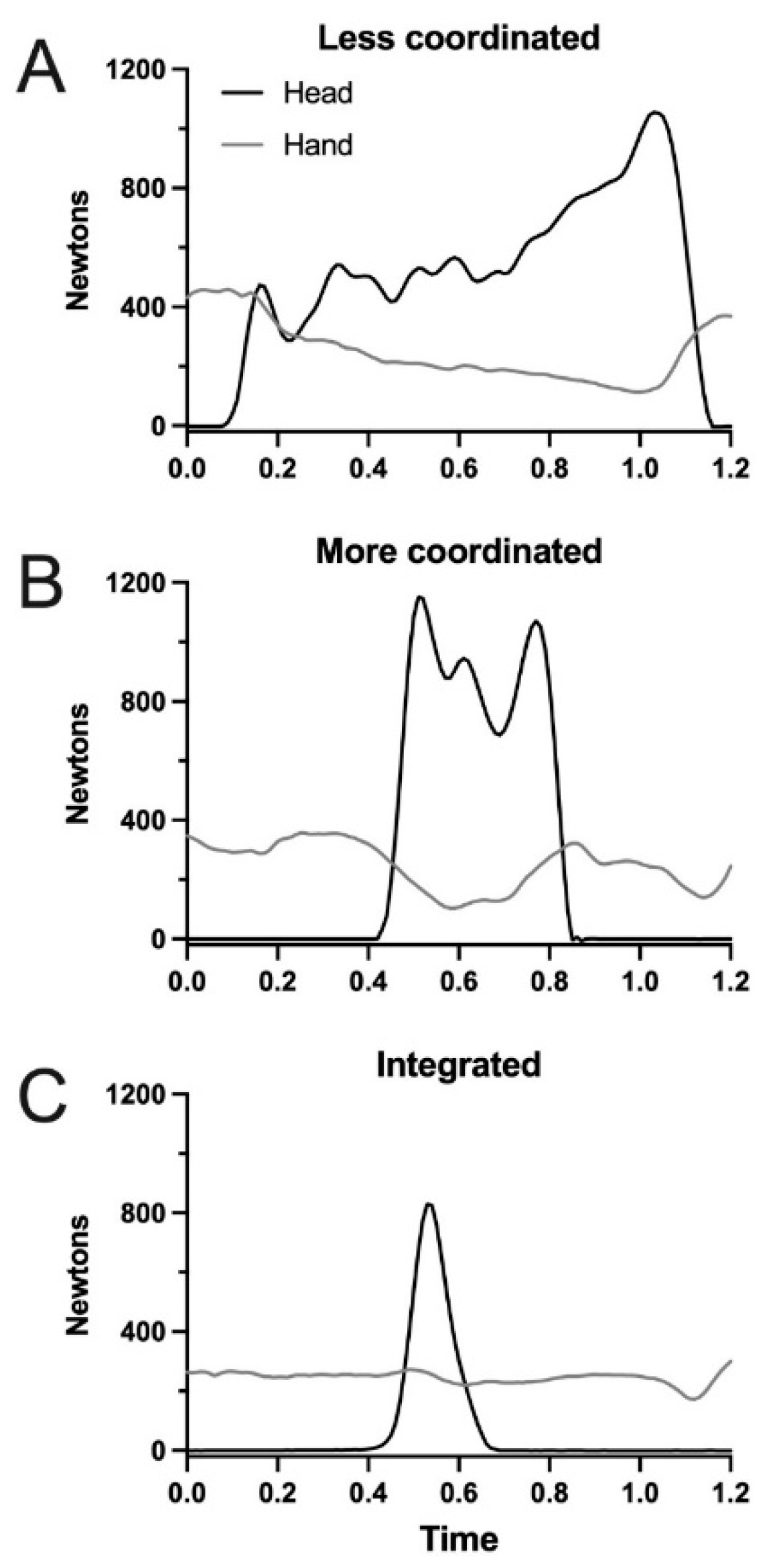

Comparisons were made to quantify and qualify participant skill and fatigue, which may be related to safety. The mean duration on the head was strongly statistically correlated to the sum of the number of peaks per participant (from all repetitions; Spearman r = 0.78,

p = 0.001), which seemed to be related to coordination of the movements. Traces were subjectively evaluated for smoothness (

Figure 4A-C), with the intent to judge relative coordination. As can be appreciated in

Figure 4A, the longer duration on the head also showed a higher variability of the forces on the head. This reflects the gradual lowering of the legs in preparation for the kip. A more coordinated movement is represented in

Figure 4B, where the trace is smooth and the force exerted by the hand increased with the head leaving the force platform. The seemingly most integrated pattern is seen in

Figure 4C (participant 16), where there is almost constant force by the hand, a short time on the head, and one peak. For each participant, simple linear regression of the repetition speed, duration on and off the head, and landing and kip forces were performed. None of these changed with the number of repetitions (data not shown), which was interpreted as indicating that the participants did not fatigue enough during the sets to alter their movement patterns.

Discussion

In this report we describe the forces borne by the head during kHSPUs. The forces ranged from 0.5 - 1.300 kN, which are well below the reported threshold for catastrophic failure predicted for young males with healthy spines (3.6 - 4 kN; however, see discussion below). An important observation was that the forces were higher during the kip than during the landing. Head movement during the load-bearing phase of the exercise was strongly correlated with self-reports of post-exercise neck pain and/or headache.

It is unethical to prospectively study forces that cause damage in living humans, which is reflected in the relative lack of literature to which direct comparisons can be made to the observations of this study. While forces in the range here reported seem precariously close to those shown to cause severe injury in some experiments,

11,13-17 as stated above the published literature taken together support that 3.6 - 4kN is the tolerance of the healthy young male cervical spine to catastrophic injury.

11,12 While the safety factors shown in

Figure 2F may seem acceptable for most healthy participants it must be stressed that the tolerance forces were proposed for young male cervical spines without degeneration, and are the limits at which

catastrophic injuries occur. Older and female spines can be expected to have a lower tolerance for injury.

18 Cervical spinal degeneration occurs secondary to injuries, occurs in most individuals as they age,

19 and reduces the strength of the spinal holding elements,

20 all of which render individuals more susceptible to compressive injuries.

21

In this study there were at least 4 individuals where the safety factors would be predicted to be much lower than calculated as in

Figure 2F. Participant 12, a 49 year old female, experienced a 0.8 kN kip force on their head, which can be compared to the reported 1.68 kN tolerance for older females

11 to give a safety factor of 2.1. A similar comparison can be made for participant 15, a 66 year old male who experienced a 1.1 kN kip force. Compared to the mean value leading to catastrophic injury in older males, 3 kN,

11 the safety factor is 2.7. Although data on previous injuries were not collected, two of the participants, both <30 years old, stated that they had suffered multiple concussions during sports, and thus attempted to land relatively gently on their heads (which they did). One of them (participant 2) had among the lowest peak kip forces, but the other (participant 6) had a much higher peak kip force (0.98 kN) compared to their peak landing force (0.63 kN). These examples suggest that evaluations of safety may need to be estimated for each athlete.

We observed a high rate of post-kHSPU symptoms (31%), and show that movement of the head during these exercises is a positive predictor for neck pain and/or headaches. While there is no way to strengthen the neck to withstand compression, it is possible to strengthen and train towards greater stability. Modeled as a column, the cervical spine is stiffest and thus more capable of withstanding axial loading when the force vector passes through the occipital condyles and the T1 vertebral body.22,23 Any bending compromises the stiffness of the cervical spine, and renders it more susceptible to injury.20 All who perform these exercises should be taught to keep their neck as stiff as possible, and to position their head so that their vertex contacts the floor (or pad).

There has been no report, including case studies, of injuries following kHSPUs. Some participants in our study had been performing kHSPUs regularly for up to 12 years with no reported negative effect. We cannot explain this apparent disparity, and presents more difficulty with making a blanket statement about safety. However, since a history of head and neck injury, degenerative changes, and age are known to reduce neck load bearing capability, such athletes should be dissuaded from performing kHSPUs. The motions of the head (and likely the neck) observed in this study, which were associated with post-kHSPU pain, were not readily appreciated, but were apparent using slow motion video. It is recommended that coaches perform this relatively easy analysis on athletes, especially those who suffer post-kHSPU symptoms. Athletes and coaches should also know that more padding will cause more force to be translated to the neck.11,23

Kipping HSPUs are unique, quirky, and fun, and require strength and coordination. As in American football, where concussions occur regularly, kHSPUs will likely remain an exercise performed by many thousands of people. The participants in this study had all received similar coaching, where proper head posture during these exercises was stressed. These exercises are typically performed while a clock is running, and technique can become secondary to performing the maximum number of repetitions, at the discretion of the athlete. It is hoped that further study into the incidence of post-kSPHU symptoms will be performed to allow better coaching towards kHSPU safety.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study involved human participants and IRB approval was obtained.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the owner of CrossFit Rising Tide for allowing the study to be performed within their facility, and thanks each athlete who volunteered to be part of this study. There was no external funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no financial or other conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Feito Y, Burrows EK, Tabb LP. A 4-Year Analysis of the Incidence of Injuries Among CrossFit-Trained Participants. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(10):1-8.

- Szeles PRQ, da Costa TS, da Cunha RA, et al. CrossFit and the Epidemiology of Musculoskeletal Injuries: A Prospective 12-Week Cohort Study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8(3):1-9.

- Mehrab M, de Vos RJ, Kraan GA, Mathijssen NMC. Injury Incidence and Patterns Among Dutch CrossFit Athletes. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(12):1-13. [CrossRef]

- Montalvo AM, Shaefer H, Rodriguez B, Li T, Epnere K, Myer GD. Retrospective Injury Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Injury in CrossFit. J Sports Sci Med. 2017;16(1):53-59.

- Hector R, Jensen JL. Sirsasana (headstand) technique alters head/neck loading: Considerations for safety. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2015;19(3):434-441. [CrossRef]

- Dave BR, Krishnan A, Rai RR, Degulmadi D, Mayi S. The Effect of Head Loading on Cervical Spine in Manual Laborers. Asian Spine J. 2021;15(1):17-22. [CrossRef]

- Jäger HJ, Gordon-Harris L, Mehring UM, Goetz GF, Mathias KD. Degenerative change in the cervical spine and load-carrying on the head. Skeletal Radiol. 1997;26(8):475-481. [CrossRef]

- Levy LF. Porter's Neck. Br Med J. 1968;2(5596):16-19.

- Joosab M, Torode M, Rao PV. Preliminary findings on the effect of load-carrying to the structural integrity of the cervical spine. Surg Radiol Anat. 1994;16(4):393-398. [CrossRef]

- Charmont J. Kinovea (0.9.5). 2021.

- Nightingale RW, McElhaney JH, Camacho DL, Kleinberger M, Winkelstein BA, Myers BS. The dynamic responses of the cervical spine: buckling, end conditions, and tolerance in compressive impacts. SAE Transactions. 1997;106:3968-3988. [CrossRef]

- Nightingale RW, McElhaney JH, Richardson WJ, Myers BS. Dynamic responses of the head and cervical spine to axial impact loading. J Biomech. 1996;29(3):307-318. [CrossRef]

- Nusholtz GS, Melvin JW, Huelke DF, Alem NM, Blank JG. Response of the Cervical Spine to Superior—inferior Head Impact. SAE Transactions. 1981;90:3144-3162. [CrossRef]

- Alem NM, Nusholtz GS, Melvin JW. Head and neck response to axial impacts. SAE Transactions. 1984;93:927-940. [CrossRef]

- Yoganandan N, Sances A, Jr., Maiman DJ, Myklebust JB, Pech P, Larson SJ. Experimental spinal injuries with vertical impact. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1986;11(9):855-860. [CrossRef]

- Alem NM, Nusholtz GS, Melvin JW. Superior-inferior head impact tolerance levels. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute; 1982.

- Yoganandan N, Pintar FA, Humm JR, Maiman DJ, Voo L, Merkle A. Cervical spine injuries, mechanisms, stability and AIS scores from vertical loading applied to military environments. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(7):2193-2201.

- Pintar FA, Yoganandan N, Voo L. Effect of age and loading rate on human cervical spine injury threshold. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998;23(18):1957-1962. [CrossRef]

- Tao Y, Galbusera F, Niemeyer F, Samartzis D, Vogele D, Wilke HJ. Radiographic cervical spine degenerative findings: a study on a large population from age 18 to 97 years. Eur Spine J. 2021;30(2):431-443. [CrossRef]

- Maiman DJ, Sances A, Jr., Myklebust JB, et al. Compression injuries of the cervical spine: a biomechanical analysis. Neurosurgery. 1983;13(3):254-260. [CrossRef]

- Yoganandan N, Chirvi S, Voo L, Pintar FA, Banerjee A. Role of age and injury mechanism on cervical spine injury tolerance from head contact loading. Traffic Inj Prev. 2018;19(2):165-172. [CrossRef]

- Cusick JF, Yoganandan N. Biomechanics of the cervical spine 4: major injuries. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2002;17(1):1-20. [CrossRef]

- Pintar FA, Yoganandan N, Voo L, Cusick JF, Maiman DJ, Sances A. Dynamic Characteristics of the Human Cervical Spine. 1995. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).