1. Introduction and Significance

1.1. The Pathway for Green House Gas (GHG) Emissions Reduction for the State of Kuwait

In 2021, the State of Kuwait emitted 25 tons of CO2 per capita, which was the third highest in the world after its neighbors Qatar and Bahrain (36 and 27 tons of CO2 per capita respectively). This pushes Kuwait to have carbon emissions to be more than four times higher than the average of 28 European Union countries (6.1 tons of CO2 per capita) [

1,

2,

3]. The State of Kuwait has pledged as vital contributions to United Nations to reduce GHG emissions by adopting a "low carbon equivalent emission economy." In its first NDC submitted in April 2018, Kuwait outlined its action plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions through the opening of the Shayaya Renewable Energy Park, 3.2 GWe solar power and wind energy complex, and the creation of a mass transit (metro) system that has yet to be realized 5 years later. There are some issues of consistency and clarity for Kuwaiti government's pledge to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and its action plan as "there is no discussion of what this pledge entails or how it should be implemented." [

4,

5] The largest emitting sector is electricity generation (58 percent), which is primarily used for air cooling through the use of air conditioning and desalination of saline water in the world's hottest and driest climate conditions. The oil and gas sector responsible for 11% of GHG emissions, whereas the transport segment of economy is accountable for 18% GHG emissions [

6,

7]. This paper aims to provide a visible path for GHG reduction by greening the transportation sector, specifically by switching from Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicles to electric vehicles (EVs).[

8]

1.2. Lowering GHG Emission via in the transportation sector

Only 0.2% of transportation in Kuwait is via public transport, primarily due to lack of bus infrastructure, cultural conventions, and extreme climate conditions. There have been no campaigns or other government initiatives to promote or encourage the general public to utilize public transportation. [

9] Private automobiles are predominantly utilized by the majority of Kuwaiti citizens and hence appear to be the most prevalent mode of transportation. Only about 600,000 of the 2,3 million vehicles registered in Kuwait belong to expats, who account for 70% of residents versus 30% of citizens [

10]. In addition, approximately 90 percent of the 295 EVs registered in Kuwait between 2019 and March 2023 are owned by Kuwaitis [

11]. One of the reasons that explains why expats in Kuwait do not purchase electric vehicles is the lack of fast charging stations and the refusal of landlords to enable tenants to install EV charging wall boxes in rented properties. Kuwaiti citizens tend to live in their own houses as a result of various government programs, whereas expats are prohibited from owning real estate in Kuwait and as a result most expatriates are forced to rent apartments and must obtain approval from their landlords for the installation of charging equipment which is typically denied [

12].

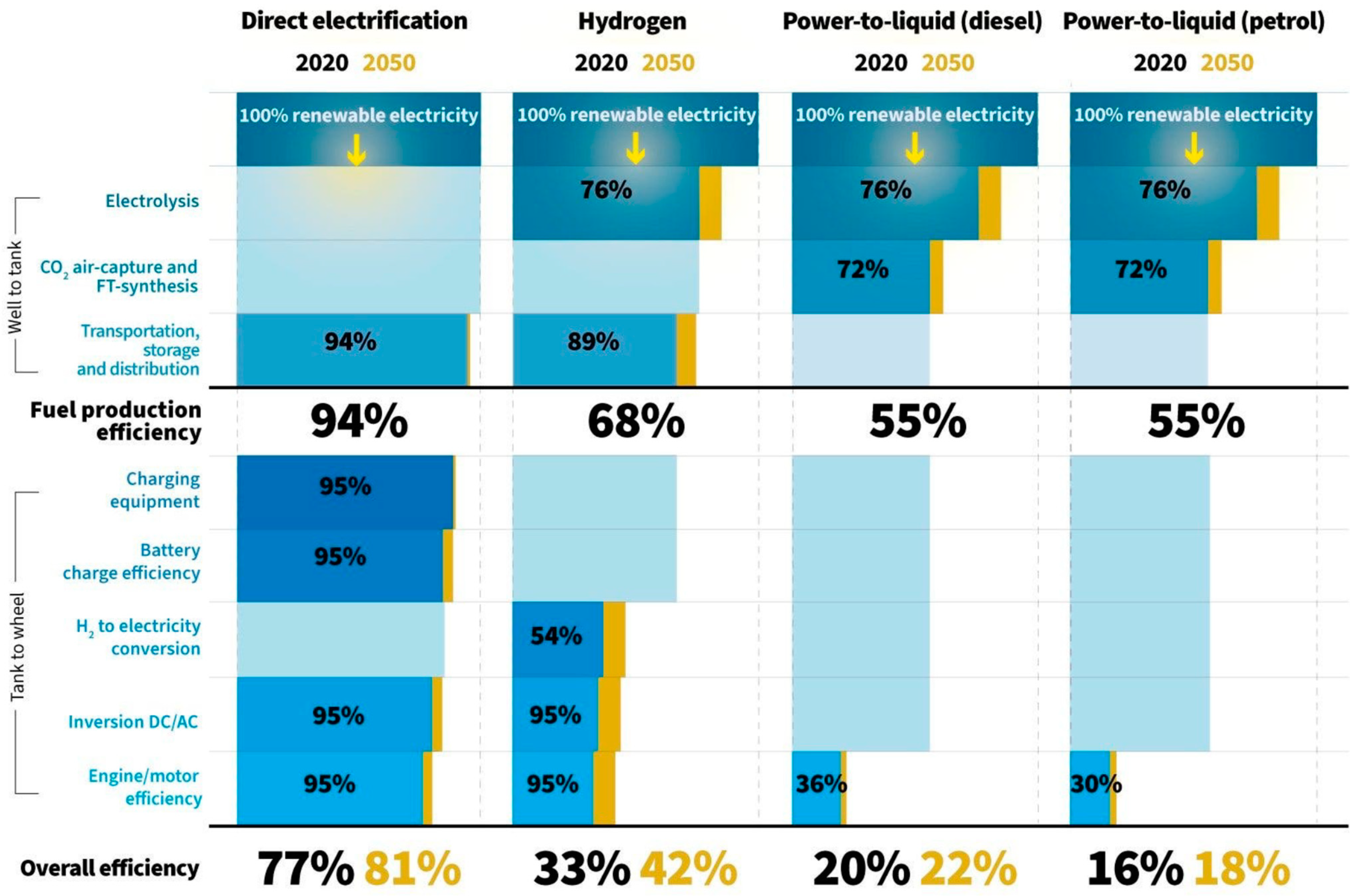

1.3. The Reason for Electric Vehicle to be the optimal for Zero Emission Transportation

In terms of vehicle efficiency, electric vehicles are best adapted to reduce carbon footprint and have the lowest operating expenses [

13]. Mr. Abu Dagga, the director of Powerid Germany, believes that e-mobility is the key to sustainability and the high ground against climate change. The primary reasons why e-mobility is superior to ICE transportation, regardless of whether the fuel source is petroleum, diesel, or natural gas, particularly when energy losses are considered. Front-end Well-to-Tank investigations reveal that EVs lose approximately 6% of their energy compared to 45% in the petroleum industry [

14,

15]. Additionally, rear end Tank-Wheels studies reveal an additional 17% energy loss compared to 35% energy loss for diesel-powered vehicles and 39% energy loss for gasoline-powered vehicles, where the majority of energy is lost as excess heat that is not converted into energy for the wheel. EVs are up to five times more effective than gasoline-powered internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, proving their superiority in reducing greenhouse gas emissions (See

Figure 1). Efficiency of EV over ICE is today 3 times more but will be 4 times more efficient in 20 years as EV batteries will become lighter and more efficiency in terms of energy story and transfer with new technologies such as the solid-state batteries and EV batteries having a second live after as energy storage for wind and solar farms [

16]. Where EV batteries are generally exposed of with the car or replaced after their charging capacity goes below 65%, but present a cheap option in made up battery pack in a container system as they are repurposed to store solar energy overnight when the sun is not shining. Perfect example of that is the 25MWH grid scale energy storage system in California where approximately 1300 disposed EVs Honda and Nissan batteries are strung together in the B2U SEPV Sierra hybrid solar storage facility which uses slower charging time than the high performance EVs [

17,

18]. The cost of installing such a system is USD 200 per kilowatt hour to install as the batteries do not need refurbishing. [

19] Lithium recycling factories are also fast coming online like the Li Cycle Rochester facility where the company claims to be able to recapture up to 95% of the battery resources for recycling using closed system water-based solution where the minerals are captured in a “black mass” which is then re-separated into battery grade lithium and cobalt, nickel as as well as other materials to be reused [

20]. However, according to Powerid [

13], hydrogen is not as suitable for smaller vehicles as it is for heavy-duty transport or construction vehicles, large sea vessels, or even aircraft due to its lack of energy efficiency, storage and transportation complications, and flame speed that is 10 times that of methane gas and thus more explosive [

21,

22]. This view is in stark contrast to that of Toyota and other Japanese automakers, who favor hydrogen as the primary source of zero-emission technology due to its rapid charging and long range as they appear to be losing the EV world market. [

23]

1.4. The Oil Savings for Each Electric Vehicle

With each transition from internal combustion engines (ICE) to EV, oil that would have been used for combustion is saved. This equates to approximately 10 barrels of oil equivalent (BOI) per year for a midsize car, one barrel for a motorcycle, 244 barrels for an A-class vehicle, and 274 barrels for a bus [

24]. By 2022's end, over 20 million electric vehicles will have been sold.[

25] The transition from ICE to EV is anticipated to conserve 2.5m petrol barrels per day by 2025 which is roughly equivalent to the everyday petrol production of Kuwait, the tenth largest oil producer [

26,

27]. BloombergNEF predicts that the demand for oil will plateau in 2026 and started to decline in 2027 as a result of the transition from internal combustion engines (ICE) to EVs for all vehicle types. The Tesla Model-Y just surpassed Toyota Corolla as the world's sales record breaking automobile for the first quarter for year 2023, with 267,200 vehicles sold compared to 256,400 for Toyota Corolla [

28].

1.5. Low Maintenance of Electric Vehicles

EVs have lower maintenance costs than internal combustion engines (ICE) vehicles due to the factors listed below. EVs have significantly fewer mechanical components or moving parts than ICE vehicles, with approximately 20 moving parts for EVs compared to approximately 2,000 for ICE vehicles [

29]. Fewer components translate to fewer items that can fail or wear out over time, resulting in lower maintenance costs. The US Energy Department (Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy) determined in 2021 that maintenance costs for EVs were only 6.1 cents per mile (4 cents per kilometer) compared to ICE costs of 10.1 cents per mile. [

30] Following are the EERE study's explanations for this disparity: A) Unlike ICE vehicles, EVs do not require regular lubricant replacements. B) Electric vehicles utilize regenerative braking, which pauses the vehicle by converting the electric motor into a generator to recharge the battery. This reduces the frequency of replacing brake pads and rotors by minimizing system wear and tear. EVs lack exhaust systems, which are susceptible to corrosion and other damage in ICE vehicles. D) ICE vehicles require regular battery maintenance or replacement, whereas EV batteries are designed to last a very long time, often the life of the vehicle. E) ICE vehicles require more frequent flushing of the refrigerant and other maintenance on the refrigeration system. EVs typically have less stringent cooling requirements, which further reduces their maintenance needs. F) EVs have no gasoline pumps, fuel injectors, or fuel containers to maintain and replace. G) Due to their simplicity and lack of moving parts, electric motors are exceptionally durable and can outlast the rest of the vehicle with minimal or no maintenance. H) EVs have a gearless powertrain and, as a result, no (Automatic) Transmission (AT), which in ICE vehicles often requires costly maintenance. Altogether, these factors can save a substantial amount of money over the tenure of an EV versus an ICE vehicle.

1.6. The Durability of the EV Battery Dependence

Evidently, while routine maintenance on EVs is typically much less expensive, replacing the EV battery after the warranty expires after 8-10 years can be quite costly (Kia/Hyundai and Mercedes offer 10 years and lifetime for the Hyundai Ioniq). The battery replacement cost (5,000-15,000 USD) may determine the vehicle's lifespan, which is approximately 13 years for ICE vehicles [

31]. EV resale value depreciation versus ICE resale value depreciation may represent the greatest operational cost if the battery does not last. Fortunately, the majority of studies indicate that EV batteries will outlive the vehicle, with over 70% of their charging capacity remaining after 13 years of use. One can anticipate a loss of 2.3% of range per charge for every year driven, which equates to approximately 13 years or 240,000 km driven before the charging capacity falls below 70% of its initial capacity [

32]. According to industry sources, if the original battery is large enough, 50% charge may suffice for the majority of usage, extending the EV's lifespan to 20 years. Nissan Leaf has been on the market for thirteen years, and a significant number of original vehicles are still on the road. Tesla also reports empirical data of average EV utilization of 300,000 km in the United States and 244,000 km in Europe [

33]. Tony Seba, a Stanford technology forecaster, states in a recent report by RethinkX from March 2023 that the longevity and autonomy of EVs will be such that sales of new automobiles will plummet 75% over the next 20 years, giving some hope that EV depreciation will not outweigh ICE and that operational costs (OPEX) will be lower. [

34] He also predicts that the EVs will over the ICE much faster than predicted base on his S-curve cost lowering predictions for emerging technology and a Chinese made EV will take over as the mainstream consumer choice in the very near future because of value for money and technology and quality improvements while lowering cost per MW of charging capacity in production of the EV battery.

On the other hand, it is a known fact that EV batteries degrade more quickly, and the majority of studies on the durability of EV batteries are conducted in Europe or North America. The Kuwait Institute of Scientific Research (KISR), the national laboratory of Kuwait, has conducted its own research with promising results [

35,

36]. However, due to the lack of years that EVs have existed in Kuwait, real-world empirical data is still deficient and does not provide conclusive evidence regarding how long EV batteries will last in extreme heat conditions. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) recently bought a controlling stake in US Lucid Motors with the intention of producing quarter of the production in KSA or total of half a million vehicles by 2030 and first car by 2025. Similarly, the Investment Promotion Agency Qatar is exploring if the country can be EV manufacturing hub for the Middle East and North Africa-MENA- region in cooperation with German Volkswagen and Chinese Gaussin and Yutong, with whom the Qatari government has already partner up with [

37]. It is clear that the issue of EV driving with atmospheric heat reaching above 50 C degrees has to be dealt with both in terms of battery cooling and durability of the battery.

2. Literature Review

In general, the existing literature suggests that successful transformations and transitions are required to increase the adoption of sustainable e-mobility and surmount barriers to its adoption. While practitioners, academics and researchers have studied the EV phenomenon on an international scale and country-specific evidence [

38], however, limited evidence has been conducted from an emerging market of Kuwait. Apparently, there is insufficient research that has been conducted among drivers of ICE vehicles which aim to know their future stated preferences for EVs. This study had three goals: (i) to examine Kuwaiti ICE vehicle drivers indicated perceptions of EV attitudes; (ii) to identify their preferable EV features; and (iii) to determine their prospective EV purchase requirements and conditions. Prominently, this research is part of a larger initiative entitled "Breaking the ICE reign: a mixed-method study of attitudes toward purchasing and using EVs in Kuwait." [

39,

40]

In a summary, the recent EVs literature reviews emphasized on the following stated attributes for EVs:

1) upfront purchasing prices, maintenance and repairs cost, protection, and insurance cost, charging costs [

41,

42], guarantees costs. [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]

2) Technology characteristics: battery, range, top speed, and acceleration. [

48,

49,

50,

51]

3) Infrastructure characteristics, including sluggish and rapid charge networks, commercial and charging public infrastructures, and home recharging infrastructures. [

52]

4) Financial, non-financial and social attributes: free parking spots, price reduction, government subsidies policies- health policy and safety policy [

53], taxes discount policies, and penalty policy for petrol-fueled vehicles [

54,

55]

5) Design, brand reputation, and credibility are brand attributes [

56]

Interestingly, the existing reviews of work aimed to investigate these aforementioned attributes were dispersed. In the following respects, the present study complements the current work of literature as follows: firstly, current study applies five categories of attributes, including economic, technical, infrastructure, brand, and financial and non-financial policy attributes, collectively and exhaustively on a single set of options for EVs preferences. Importantly, the attributes have not been investigated collectively in a single study; rather, they have been analyzed in various existing studies. Secondly, indeed, the present investigation focused on conventional automobile drivers that have never been investigated. Lastly, the current research closes a void in work of literature and EV trend in terms of demographics and stated preferences through a large sample survey collected from Kuwait. As these six gulf countries share the same society, culture, economy, government policies, climate, and geography, the present study contributes to the growing body of knowledge that can be applied to consumers in other GCC countries-Oman, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates- markets and the stated preferences for EVs. The most studies focused on markets in developed nations such as Europe, the United States, and Australia. For instance, Guerra and Daziano analyzed a large sample of respondents' EV purchase motivations in the United States. Consumers are generally willing to pay more for a longer range, shortened recharging periods, reduced operating costs, and shorter parking search times, according to their findings. [

57]

In contrast, ICE vehicles continue to be perceived as more comfortable in terms of design and appearance than EVs, particularly among senior consumers. Moreover, women were discovered to be more environmentally conscious than males. Ziemba discovered that in Poland, consumer EV acceptability is most strongly influenced by technological standards. [

58] For instance, Vilchez conducted a large-scale survey among vehicle owners in a number of European nations, including Italy, France, Germany, Spain, Poland as well as UK, and found that 50 percent of the respondents did not prefer EVs due to the higher initial cost—higher cost than conventional automobiles. [

59] Fortunately, a recent study conducted by Temple found that the production of new batteries (lithium-metal batteries) could make EVs as affordable and convenient as gasoline-powered vehicles, indicating an anticipated increase in the adoption rates among car drivers worldwide as a result of technological development. [

60]

Kowalska-Pyzalska examined consumer preferences for alternative fuel vehicles or electric vehicles (EVs) in Central and Eastern European nations and found that safety attributes are one of the most sought-after characteristics of excellent EVs, followed by price, range, and brand [

61]. Their findings require automakers and policymakers to actively promote electric vehicles in order to increase their adoption rates. Chao Ma analyzed the preferences of Chinese consumers for electric vehicles and found that purchase price, vehicle category, and fast-charging batteries were the most influential factors. Government policy plays a crucial role in promoting the adoption of electric vehicles. [

62]

3. Methods

This study employed a quantitative descriptive approach consisting of mainly closed-ended questions to accomplish its research objectives by designing a large-scale questionnaire survey to provide a comprehensive, all-inclusive perspective on EVs in Kuwait. The first section of the extensive survey centered on demographic information about respondents, such as their gender, age, level of education, income ranges, occupation, ethnicity, and vehicle ownership. In order to measure the extent of stated preferences approach to willingness-to-buy or pay, the second section of the extensive survey consists of exhaustive questionnaires about EVs features, factors and attributes that have been intensively discussed by the majority of the existing and updated strands of the literature. In addition, the large-scale survey was evaluated and distributed to 50 full-time instructors and part-time educators’ views and recommendations. The assessment phase comprised inquiries regarding objective, content, and layout of the questionnaire. We received 30 completed evaluations in total as part of the validation process. The overall response rate was near 60%. We subsequently incorporated the suggested modifications and revised the questionnaire's format and overall design proposed mainly from AOU instructors. To make the questionnaire easier to complete, we omitted several sections and treated it as a unit. In addition, we added the response option "I don't know" in order to collect honest responses and permit the free expression of opinions. The evaluation revealed that approximately 96% of the questionnaire's content is unambiguous, informative, and simple to understand. Similarly, 93 percent of questionnaire objectives are clearly specified, the content is relevant, and the order is logical. While 90 percent of respondents indicated that the content is correct and complete and the layout is workable, the86 percent agreed that structure is straightforward. We developed two variants of the questionnaire; a version was written in Arabic language and another in English language. Google Forms was used to create the questionnaire because it is one of the commonly used, validated tools for data collection. The questionnaire is then disseminated to diverse groups in Kuwait, including the general public, faculty members, students, and tutors. Participants must be a Kuwait citizen and 18 years of age and also own driver's license and a car in their own or family name in order to be eligible for the survey. We proposed this condition as many Kuwaitis use private drivers to get around and do not possess driving license. We believe that purchasing behavior for a car that is driven by a driven are different than purchasing behavior that is driven by the owner. We started data collection-phase from February2022 to the month of May of 2022. Then a technique of random sampling was utilized during the data collection phase [

63]. The researchers distributed the survey links by randomly selecting the target audience from diverse groups of individuals nationals in Kuwait inclusive of mature students, instructors, professionals, and others. Moreover, the study sample included few Kuwait individuals with temporary or permanent contracts such as rental or were provided a company car. Those were contractual employees who were provided with ICE automobiles from their employer companies with petrol paid privileges. These participants were included in the sample.

Initially, we collected a large sample size (604) in order to obtain comprehensive demographic data representative of the population in Kuwait and to draw actionable conclusions about the population. Subsequently, we eliminated 132 questionnaires (i.e., those who did not have or drive a car), we ended up with a total of 472 questionnaires that were analyzed, and this data was used for priory published paper. However, after observing how Kuwaiti national had fundamentally different EV purchasing behavior than the expat population, due to difference in purchasing power, the strict rules and restriction expats have to adhere to obtain driver’s license within the State of Kuwait as well as expats are not allowed to own real estate and landlords do not permit installation of home charging for EVs, as the result almost all EVs buyers to date have been Kuwaiti nationals. After careful selection our sample we isolated the Kuwait nationals as the result we obtained a reduced sample of 227 Kuwaiti nationals who owned and drove conventional vehicles.

At the beginning of the data-collection phase, the purpose and aims of the study is introduced to the participants and thoroughly explained. Additionally, instructions are written on the front page to prevent confusion. Then, we invited participants to complete the survey online. Finally, descriptive statistics-frequencies and percentages- were computed using SPSS 19, applying t-test and AVOVA tables for depth analysis and standard error analysis. Despite the needed efforts yielded to complete the present study for the time constraint, this particular endeavor has certain limitations. Because the sample for was gathered from a single location Arab-Open-University in Kuwait, the limitation precludes us from generalizing to the context of all Kuwaiti drivers. In fact, additional research with a larger sample size is required on this specific topic. For Example, depth investigations are necessary to uncover concealed insights regarding the acceptance and the favorites associated with EVs use among EVs owners. One of the requirements for participation in the survey was automobile ownership. In 2021, approximately 3 million vehicles will be registered in the country [

64]. Excluding company-owned and expat-registered vehicles, we estimate that approximately 1.6 million registered vehicles by Kuwaiti citizens. Here, we sampled ‘Early-Majority’ prospective customers, which we estimated as forty percent of population as a total, or 6400000 viewed as Early Majority Kuwaiti drivers. The sample consisted of 227 Kuwaiti drivers and vehicle proprietors, or approximately 0.04 percent of the total representative population, which is modest and, if not for our resource limitations, would have ideally included at least 1,000 participants. Consequently, our margin of error is approximately +/ 7percent, assuming 95% a confidence level [

65].

4. Findings

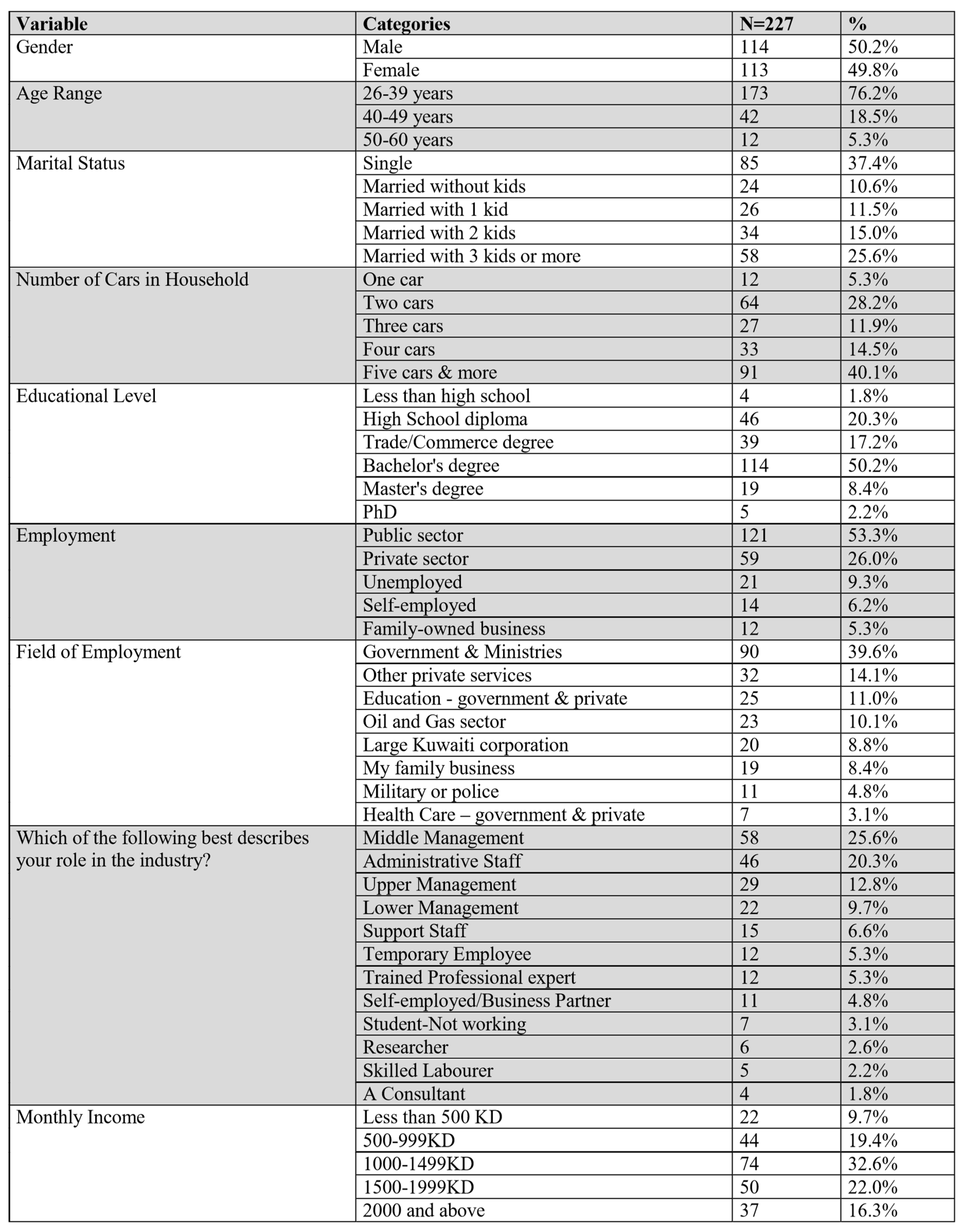

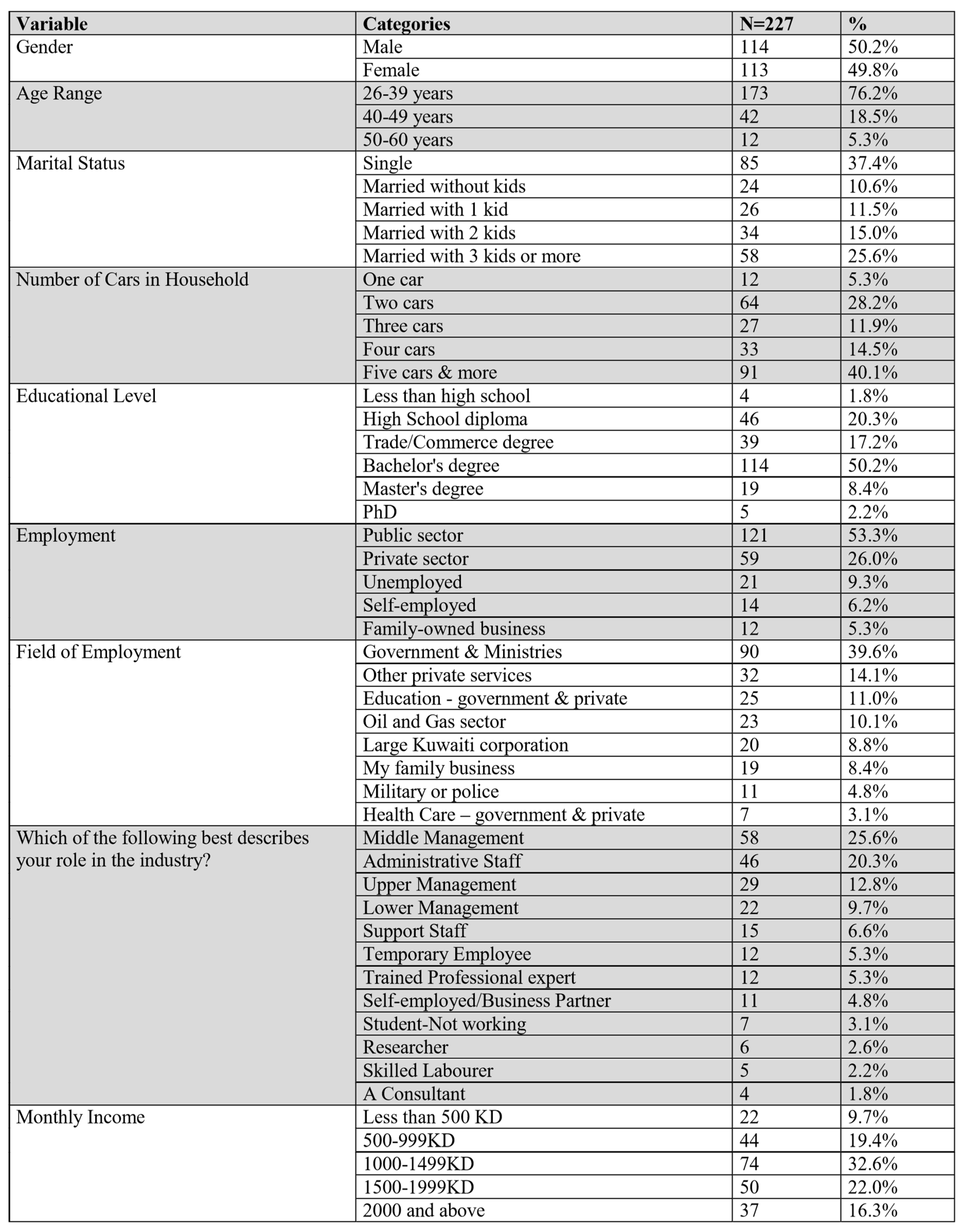

This investigation included the participation of two hundred twenty-seven Kuwaiti ICE owners and possess driving license. Table 1 provides demographic characteristics summary. The questionnaire was completed equally by men (50.2%) and women (49.8%). More than three-quarters of sample were between 26years old and 39 years old (76.2%). Over one third were unmarried (37.4%), while 25.6% were married with at least three children. Over fifty percent held bachelor degrees. More than a fourth of respondents owned five or more automobiles (40.1%), and more than a quarter of them owned two automobiles (28.2%). More than half of the participants (53.3%), versus alightly above quarter (26%) were working with the public sector. Over a third of the participants (39.6%) are employed in the public and government ministries sector, and a quarter (25.6%) were intermediate managers. 32.6% of participants have a monthly income of between 1,000 and 1,499 KD.

Table 2 displays the participants' perspectives on EVs. More than forty percent of respondents (41.8%), as shown in the table, stated that they would be willing to pay an extra 6-20%, while one third (33.5%) stated that they would pay no more than 5% more. More than one third of participants (37.8%) would pay 6-20% extra for EVs which they viewed as significantly faster than a corresponding ICE vehicle (0-100 in 4 seconds), while approximately one-fifth (19.4%) declare that they would pay nothing extra. More than 42% of participants (42.7% to be exact) would indicate that they were seriously contemplating purchasing EVs if gas/fuel prices increased by 50-199%, while about 18.5 % were not so concern about EVs. Over than 50% or (54.7%) indicated that they would contemplate purchasing EV if and only if the government control the prices of EVs vehicles and offor a price reduction of 10-30% less expensive than gasoline vehicles, whereas roughly one-fifth of them (18.9%) suggested that they would alter their minds if the prices were comparable to gasoline vehicles. A third of participants (29.1%) apparently would consider purchasing EVs under a condition of the availability of free rapid re-charging points and spaces on every 10-25 km, and a quarter of them (24.2%) would consider purchasing EVs if there were re-charging stations every 26-50 km.

Almost over 50% or (57.7%) responded that they would reconsider purchasing an electric vehicle under the condition availibility of dedicated express lane located on the main/major highways. Almost over 50% or (53.3%) indicated that they would reconsider purchasing an EV under a condition of the availability of free public parking spaces as many as handicapped spaces. Also, 56% apparently would purchase an EV within the next three years. Of these, 14.1% suggested that they would definitely purchase the item, while 41.9% said that they would likely do so. 46.2 percent cared for security of EVs regarding fire and accidents, while 43.2% concerned about being able to re-charge their EVs around their residential areas, whereas 30.8 percent that they would not be able to do so. Please see Table 1: The Demographic Characteristics Summary

The following scale shows:

Highly agreement: calculated Mean (M ≥ 2.33)

Medium agreement: calculated Mean (1.67 ≥ M < 2.33)

Low agreement: calculated Mean (M <1.67)

The most favorable characteristics as perceived among participants (Table 3), participants agreed strongly on three characteristics: environmental friendliness and less CO2 that leads to better air quality (M=2.43), significantly low petrol price (M=2.35), and silent engine (M=2.33). Features with moderate agreement included improved fire and collision safety(M=2.31), quicker and a better A/C conditioning (M=2.30), significantly faster acceleration(0-100 km) (M=2.20), and significantly reduced maintenance costs (M=2.19). Please see Table 3: The Most Favorable Features (N=227)

| Types of attributes (features) |

To what extent do you Agree/ Disagree about the most favorable features of electric cars? |

Mean |

SD |

| Environmental attributes |

Environmental friendliness; less CO2 that leads to better air quality |

2.43 |

.780 |

| Financial or economic attributes |

Much lower fuel price than gasoline |

2.35 |

.797 |

| Technological attributes |

Soundless engine |

2.33 |

.810 |

| Technological attributes |

Increased safety in terms of fire and crash tests |

2.31 |

.788 |

| Technological attributes |

Faster and more powerful air condition |

2.30 |

.781 |

| Technological attributes |

Much faster acceleration (from 0-100 km) |

2.20 |

.804 |

| Financial or economic attributes |

Much lower maintenance and associated cost |

2.19 |

.856 |

Regarding the requirements to purchase EVs as perceived by participants (see

Table 4), participants strongly agreed on the following five conditions: if the range (how far they can drive) per full charge would be at least 400 km (M=2.40), if the battery guarantee would last at least 10 years or 150.000 km (M=2.39), if there was a fast charging station within 5 km of almost all of Kuwait (M=2.38), if they were cool and had unique designs (M=2.38), and Other requirements had moderate agreement, such as if they begin to notice a change in air quality as a result of people driving EVs (M=2.32), the price was the same or lower than an equivalent gasoline car (M=2.31), gasoline would increase threefold (M=2.28), there was a special EVs lane on major highways (M=2.26), and the majority of their friends or family would purchase an EV (M=2.02).

5. Discussion

The proposed study investigated the attitudes, favorites, and needs of fuel vehicle drivers regarding EVs. Intriguingly, the study discovered that nearly more than half suggested that they would buy an EV in the next three years. Respondents provided the following four conditions: i) the policy makers and government should regulate and mitigate the cost of electric vehicles by 10 to 30 percent to make them more affordable than gasoline vehicles; ii) free public fast recharging points and facility should be accessible and spread out within 10 to 50 kilometers; iii) specific EVs fast lanes must be available on the major highways; and iv) handicapped free public-parking- spaces should be existed.

Consequently, this finding suggests that potential EVs drivers viewed Kuwaiti regulators as playing a crucial role in promoting the EVs reputation and recognition by planning appropriate EVs transportation infrastructure and establishing their policies for setting-up prices. Intriguingly, the outcome is coherently equaling the prior research conducted for various nations [

43,

53]. In addition, nearly 40 percent of respondents suggested that they contemplated purchasing EVs if gasoline prices increased by 50 to 199 percent in the future, recognizing that EVs are still safer during fires and accidents.

Furthermore, more than a third of respondents suggested that they were willing to pay 6 to 20 percent more for EVs than for petroleum vehicles, believing that EVs are more environmentally friendly and speedier than gasoline vehicles. This intriguing finding suggests that people in Kuwait prefer EVs to petroleum vehicles because EVs offer greater environmental, economic, and technological benefits. [

44,

46,

48] have found similar results in various countries. However, only about a third of residents (mainly expats) in Kuwait's residential locations are unable to charge electric vehicles. This implies that infrastructure for charging EVs must be nearby and readily existed in all Kuwaiti inhabited zones. In addition, drivers favored three distinct types of EV attributes, including environmental (i.e., ecological; low CO2 that improves the air-quality), financial or economic (i.e., much cheaper fuel price than gasoline), and technological (i.e., soundless engine) concur with this intriguing finding.

In contrast, current Kuwaiti ICE drivers’ sample apparently would be willing to acquire EVs within near future because they believe that EVs technological attributes (i.e., driving-range might be at least 400 km), financial or economic attributes (i.e., battery guarantee lasts 10 years or more, 150.000 km; resale EV value should be similar or higher than fueled vehicles), and infrastructure attributes (rapid-recharging points within 5km). This finding suggested that in the future, current Kuwaiti ICE drivers’ sample might be able to acquire an EVs for the nearby future if four criteria were met: the batteries affordability and resale value, the infrastructure's proximity of fast-charging stations, the technological features' range, and the brands with coolest and attractive designs. These findings are consistent with previous cases from various nations [

43,

53]

While the current study provides a broader perspective on the EV phenomenon in Kuwait, it does have some limitations. Because of lacking emphasis on empirical testing to provide clearer conclusions about the population, the findings are primarily descriptive and furthermore based on stated (rather than revealed) preferences. Therefore, future research should employ hypothesis testing to reach a definitive general inference in Kuwait. Second, additional research must employ in-depth investigations with existing EV possessors to investigate any obstacles, identify any future opportunities, and identify favorable EV characteristics and preferred designs. One suggestion is to use a focus group to obtain a more complete image of the desired features and services, as well as to determine the most effective incentives for purchasing EVs in Kuwait and the MENA region. In addition, comparative studies from various GCC regions may be of interest because the regions operate under a similar legal and economic umbrella. Lastly, additional research should investigate the management perspectives of car dealerships in Kuwait in order to examine the obstacles that are delaying the adoption and sustained mobility models for electric vehicles (EVs), clarify ambiguity surrounding EVs adoptions in Kuwait, and provide a better explanation and rationale for the reluctance to replace conventional vehicles.

6. Conclusion and Implications

Other than eliminating all government subsidies for water, electricity, and petroleum, the mass transition from ICE to EVs is the most effective strategy for reducing Kuwait's carbon footprint if EVs are charged from renewable energy sources producing the electricity consumed. However, since total lack of rapid charging EV stations (Direct Current to Direction Current DC2DC) and Kuwaiti landlords do not permit the installation of EV charging wall receptacles, ICE to EV transition is only an option for Kuwaiti citizens who own their homes. Due to backlog orders and formal tendering processes in Kuwait, it will take up to four years to construct an effective fast-charging station network. This study has therefore focused predominantly on Kuwaiti nationals stated preferences and attitudes toward electric vehicles. The current study presented substantial evidence and diversified stakeholder perspectives for the emerging market of Kuwait. The primary objective is to investigate the sustainability of EVs. The results showed that potential Kuwaiti customers anticipate purchasing an EV within the nearby future- three years-, but only under specified criteria, such as availability and readiness appropriate infrastructure such as recharging facilities, rapid roads, and free-public-parking. In addition, they were willing purchase EVs and strongly preferred EVs for their ecological, economical, and technologies attributes, but only under four conditions: battery cost and resale value, availability of the infrastructure in terms of nearby fast-charging stations, technological features in terms of range per full charge, and brand value and appealing design.

In light of the preceding findings, the existing investigation has both theory and practice implications. Theoretically, the present research supports the scant literatures on sustainable mobility in developing nations, particularly MENA-GCC-and Kuwait. The findings could facilitate broader comparisons and more accurate assessments for developing nations, including those in the MENA-GCC region. In practice, the results of this study indicated that Kuwaitis prefer EVs over petroleum vehicles because EVs offer environmental advantages, economic benefits, and technological advantages. Consequently, vehicle dealership-marketing campaigns should emphasize the utility of electric vehicles (EVs) when promoting EVs to their target markets, vehicle commuters and vehicle proprietors. In addition, the results indicated that Kuwaitis may be prepared to purchase EVs if and only if infrastructure relating to the availability of rapid recharging stations and facilities, fast traffic lanes, and free parking spaces is in place. Hence, policymakers and government regulators are encouraged to initiate the construction of infrastructure to facilitate the rapid acceptance of electric vehicles in the country.

EVs offer substantial environmental benefits that contributed to promoting the use of renewable energy, reducing both urban air pollution and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and thereby reducing human health hazards associated with GHG exposure. Therefore, we propose that the government execute knowledge policies and awareness plans and initiatives to better educate consumers on environmental issues and promote sustainability. In addition, we propose for the policymakers in Kuwait to provide sponsorship and funding programs along with other financial assistance to EV purchasers to prevent the high price of EVs. Moreover, the government should construct an accessible and appropriate infrastructure, including a wide EVs network and recharging facilities. Thus, consumers could refuel their EVs from renewable sources of energy and prevent their EVs from running out of electricity. Additionally, highways should be enhanced and better developed for EV drivers than previously.

In contrast, the study indicated that Kuwaitis might purchase EVs in the future if infrastructure regarding rapid recharging stations were readily available and easily accessible. Therefore, policymakers must construct and provide these stations to promote the adoption of electric vehicles. Kuwaitis apparently would purchase EVs for economic reasons, particularly regarding battery life and resale value. Therefore, manufacturers of electric vehicles should develop heat-tolerant longer-lasting batteries. As Kuwaitis apparently would purchase EVs for technological attributes relating to range per complete charge and brand attributes, manufacturers should attempt to design EVs with these characteristics. Because EVs are energy-efficient and reduce greenhouse gas emissions and pollution, the automobile industry should gradually shift toward their implementation.

Author Contributions

A.O. is the project's Principal Investor (PI) and is responsible for its conception, methodology, and editing, as well as the acquisition and administration of funds. S.B. and B.A. were accountable for the literature review, conceptualization, synthesis, methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing preparation of the original document, and editing. All authors have read and approved the version of the manuscript that has been published.

Funding

This paper is a component of a larger study entitled "Breaking the ICE reign: a mixed-method study of attitudes toward purchasing and using EVs in Kuwait." The study was supported by the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences, administered by the Middle East Center of the London School of Economics and Political Science, and approved by the LSE Research Ethics Committee.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study has been approved by the London School of Economics and Political Science Ethics Committee (00558000004KJE9AAO, dated 24 November 2021). Consent Form Statement: As directed by the LSE Ethics Committee, an informed statement about the utilization and purpose of the study was included in the questionnaire.

References

- Ottesen, A.; Toglaw, S.; Al Quaoud, F.; Simovic, V. How to Sell Zero Emission Vehicles when the Petrol is almost for Free: Case of Kuwait. J. Manag. Sci. 2022, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottesen, A.; Banna, S.; Alzougool, B. Damrah, S. A Greener Kuwait - How Electric Vehicles Can Lower CO2 Emissions, LSE Middle East Center Kuwait Programme Paper Series 18, 1-21 – in Press.

- Ottesen, A; Thom, D; Bhagat, R; Mourdaa, R. Learning from the Future of Kuwait: Scenarios as a Learning Tool to Build Consensus for Actions Needed to Realize Vision 2035. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djoundourian, S.S. Response of the Arab world to climate change challenges and the Paris agreement. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2021, 21, 469–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, D.S; Alshamari, A; Hameed, K. LSE, Middle East Center Kuwait Programme Paper Series 13. October 2021 Available online chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/112491/3/The_Quiet_Emergency.pdf (accessed on 6 of June 2023).

- New Kuwait (2019) Kuwait National Development Plant 2020-2025 available at https://media.gov.kw/assets/img/Ommah22_Awareness/PDF/NewKuwait/Revised%20KNDP%20-%20EN.pdf (accessed 26th August 2023).

- Energy Strategy: Technical Paper Summary, in ‘4th Kuwait Master Plan: 2040 Toward A Smart State’, Municipality of Kuwait (Kuwait City, January 2021), p. 65. 20. 20 January.

- Ottesen, A.; Banna, S. Why so few EVs are in Kuwait and how to amend it. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2021, 10, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottesen, A.; Banna, S.; Alzougool, B. Attitudes of Drivers towards Electric Vehicles in Kuwait. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Statistical Bureau 2021. Kuwait Number of Register Vehicles in Use. Available online https://www.ceicdata.com/en/kuwait/number-of-registered-vehicles/no-of-registered-vehicles-in-use#:~:text=The%20data%20reached%20an%20all,Global%20Database's%20Kuwait%20%E2%80%93%20Table%20KW. (accessed 6 June 2023).

- Automotive Union of Kuwait Regitry– Collected by Mohammed Naval, automotive industry expert in March 28 2023 via in person interview Kuwait city. 28 March.

- Ottesen, A.; Banna, S.; Alzougool, B. How to Cross the Chasm for the Electric Vehicle World’s Laggards—A Case Study in Kuwait. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Dagga, Naser 2023, E-Mobility – Electric Vehicles Technology and Innovation. Presentation at Australian University 8 May 2023.

- Anagnostopoulou, E.; Bothos, E.; Magoutas, B.; Schrammel, J.; Mentzas, G. Persuasive technologies for sustainable mobility: State of the art and emerging trends. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolaki-Iosifidou, E.; Codani, P.; Kempton, W. Measurement of power loss during electric vehicle charging and discharging. Energy 2017, 127, 730–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Gao, S.; Sun, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, F.; Hao, H. Potential of electric vehicle batteries second use in energy storage systems: The case of China. Energy 2022, 253, 124159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electrek 2023, This solar + storage system is made up of 1300 second life EV batteries. Available online from https://electrek.co/2023/02/07/this-solar-storage-system-is-made-up-of-1300-second-life-ev-batteries/ (Accessed on 26. August 2023).

- McKinsey&Company 2022. ESG Report – Creating a more sustainable, inclusive and growing future for all. Available online from https://www.mckinsey.com/about-us/social-responsibility/esg-report-overview (accessed on 26th of August 2023).

- Cole, W; Frazier, A.W; Augustine C (National Reenable Energy Laboratory),2021 Cost projection for utility-scale battery storage battery. 2021 Update. Available online https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy21osti/79236.pdf (accessed on 26th of August 2023).

- Li-Cycle Company webpage 2023 – A unique and dependable approach to solving the global battery cycling problem. Available online https://li-cycle.com/technology/ (accessed on 26th of August 2023).

- Koestner, Jeff. 6 Thing to Remembr about Hydrogen vs Natural Gas. Power Engineers. Available online: https://www.powereng.com/library/6-things-to-remember-about-hydrogen-vs-natural-gas (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Conti, M., Kotter, R., Putrus, G. (2015). Energy Efficiency in Electric and Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles and Its Impact on Total Cost of Ownership. In: Beeton, D., Meyer, G. (eds) Electric Vehicle Business Models. Lecture Notes in Mobility. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Economist 2023. How the Japan is losing the global electric-vehicle race. Available online https:www.economist.com/asia/2023/04/how-japan-is-losing-the-global-eletric-vehicle-race (accessed 8 June 2023).

- American Public Transportation. Public Transportation Fact Book 2022. Available online: https://www.apta.com/research-technical-resources/transit-statistics/public-transportation-fact-book/ (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- IEA 2023 Global EV Outlook 2023 Available online https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2023 (access on June 2023).

- BloombergNEF 2022 Electric Vehicle Outlook 2022 Available online https://bnef.turtl.co/story/evo-2022/page/7/1 (accessed June 6 2023).

- Central Statistical Bureau 2021. Kuwait Number of Register Vehicles in Use. Available online https://www.ceicdata.com/en/kuwait/number-of-registered-vehicles/no-of-registered-vehicles-in-use#:~:text=The%20data%20reached%20an%20all,Global%20Database's%20Kuwait%20%E2%80%93%20Table%20KW. (accessed 6 June 2023).

- JATO 2023 (compiled for Motor1) Tesla Model Y World best-selling car for q1 2023. Available online from https://www.motor1.com/news/669135/tesla-model-y-worlds-best-selling-car-q1-2023/ (accessed on 27th of August 2023).

- Poornesh, K; Nivya K. P. and Sireesha, K. A Comparative study on Electric Vehicle and Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles," 2020 International Conference on Smart Electronics and Communication (ICOSEC), Trichy, India, 2020, pp. 1179-1183. [CrossRef]

- Energy.gov 2021 (Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy) Battery Electric Vehicles Have Lower Scheduled Maintenance Cost than other Light-Duty Vehicles. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/vehicles/articles/fotw-1190-june-14-2021-battery-electric-vehicles-have-lower-scheduled (accessed 27th of August 2023).

- Forbes – By The Numbers> Comparing Electric Car Warranties 2022 retrieved 14.02.2023 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/jimgorzelany/2022/10/31/by-the-numbers-comparing-electric-car-warranties/?sh=4c832c553fd7.

- J.D. Power 2022. How Long Do Electric Battery Last? Available online: https://www.jdpower.com/cars/shopping-guides/how-long-do-electric-car-batteries-last#:~:text=Generally%2C%20electric%20vehicle%20batteries%20last,not%20pair%20well%20with%20EVs. (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- EVBox 2022. How long do electric car battery last? Available online:. Available online: https://blog.evbox.com/uk-en/ev-battery-longevity#:~:text=According%20to%20current%20industry%20expectations,is%20nearly%20imperceptible%20to%20drivers. (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- RethinkX 2023 Rethinking Transportation – Cost and Speed of Adoption. Available online https://www.rethinkx.com/fullsummary (accessed 17 June 2023).

- Hamwi, H.; Alasseri, R.; Aldei, S.; Al-Kandari, M. A Pilot Study of Electrical Vehicle Performance, Efficiency, and Limitation in Kuwait’s Harsh Weather and Environment. Energies 2022, 15, 7466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamwi, H.; Rushby, T.; Mahdy, M.; Bahaj, A.S. Effects of High Ambient Temperature on Electric Vehicle Efficiency and Range: Case Study of Kuwait. Energies 2022, 15, 3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Official Website of the International Trade Administration 2022, Qatar electric vehicles challenges and opportunities. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/market-intelligence/qatar-electric-vehicles-challenges-and-opportunities#:~:text=Qatar's%20EV%20strategy%20aims%20to,in%20motion%20in%20September%202021. (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Contestabile, M., & Turrentine, T. (2020). Introduction: Understanding the Development of the Market for Electric Vehicles. Who’s Driving Electric Cars: Understanding Consumer Adoption and Use of Plug-in Electric Cars, 1-8.

- Ottesen, A.; Banna, S.; Alzougool, B.; Simovic, V. Driving factors for women’s switch to electric vehicles in conservative Kuwait. J. Women’s Entrep. Educ. 2022, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottesen, A.; Banna, S.; Alzougool, B. Women Will Drive the Demand for EVs in the Middle East over the Next 10 Years—Lessons from Today’s Kuwait and 1960s USA. Energies 2023, 16, 3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, H.; Zhu, L.; Campana, P.E.; Lu, H.; Wallin, F.; Sun, Q. Factors influencing the economics of public charging infrastructures for EV—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bai, X.; Shang, J. Is subsidized electric vehicles adoption sustainable: Consumers’ perceptions and motivation toward incentive policies, environmental benefits, and risks. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 192, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colak, M.; Kaya, I. providing the spark: Impact of financial incentives on battery electric vehicle adoption. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2020, 98, 102255. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Long, R.; Chen, H.; Geng, J. A review of factors influencing consumer intentions to adopt battery electric vehicles. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 78, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lia, F.; Molina ETimmermans, H.; Wee, B.V. Consumer preferences for business models in electric vehicle adoption. Transp. Policy 2019, 73, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, F.; Molin, E.; Wee, B.V. Consumer preferences for electric vehicles: A literature review. Transp. Rev. 2017, 37, 252–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Wu, W. Why people want to buy electric vehicle: An empirical study in first-tier cities of China. Energy Policy 2018, 112, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archsmith, J.; Muehlegger, E.; Rapson, D. Future Paths of Electric Vehicle Adoption in the United States: Predictable Determinants, Obstacles and Opportunities. Environ. Energy Policy Econ. 2022, 3, 71–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongklaew, C.; Phoungthong, K.; Prabpayak, C.; Chowdhury, M.S.; Khan, I.; Yuangyai, N.; Yuanngyai, C.; Techato, K. Barriers to electric vehicle adoption in Thailand. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.W.; Zhuang, G.; Ali, S. Identifying and bridging the attitude behavior gap in sustainable transportation adoption. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2019, 10, 3723–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choi, J.; Yi, Y.; Kim, H. Analysis of Influencing Factors in Purchasing Electric Vehicles Using a Structural Equation Model: Focused on Suwon City. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardman, S.; Jenn, A.; Tal, G.; Axsen, J.; Beard, G.; Daina, N.; Figenbaum, E.; Jakobsson, N.; Jochem, P.; Kinnear, N.; Plötz, P.; Pontes, J.; Refa, N.; Sprei, F.; Turrentine, T.; Witkamp, B. A review of consumer preferences of and interactions with electric vehicle charging infrastructure. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 62, 508–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albawab, M.; Ghenai, C.; Bettayeb, M.; Janajreh, I. Sustainability performance index for ranking energy storage technologies using multi-criteria decision-making model and hybrid computational method. J. Energy Storage 2020, 32, 101820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashari, Z.A.; Ko, J.; Jang, J. Consumers’ intention to purchase electric vehicles: Influences of user attitude and perception. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.; Burke, M.; Cui, J.; Perl, A. Fuel price changes and their impacts on urban transport—A literature review using bibliometric and content analysis techniques, 1972–2017. Transp. Rev. 2018, 39, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Kaa, G.; Scholten, D.; Rezaei, J.; Milchram, C. The battle between battery and fuel cell Powered electric vehicles: A BMW approach. Energies 2017, 10, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, E.; Daziano, R.A. Electric vehicles and residential parking in an urban environment: Results from a stated preference experiment. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 2020, 79, 102222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemba, P. Multi-criteria approach to stochastic and fuzzy uncertainty in the selection of electric vehicles with high social acceptance. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 173, 114686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilchez, J., Harrison, G., Kelleher, L., Smyth, A. and Thiel, C. (2017). Quantifying the factors influencing people’s car type choices in Europe. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, p.18.

- Temple, J. (2021). Lithium-metal batteries for electric vehicles. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/02/24/1018102/lithium-metal-batteries-electric-vehicle-car/. 2021.

- Kowalska-Pyzalska, A.; Michalski, R.; Kott, M.; Skowrońska-Szmer, A. Consumer preferences towards alternative fuel vehicles. Results from the conjoint analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 155, 111776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.C.; Fan, Y.; Guo, J.F.; Xu, J.H.; Zhu, J. Analyzing online behavior to determine Chinese consumers’ preferences for electric vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, E., Bryman, A., & Harley, B. (2018). Business research methods. Oxford University Press.

- CEIC. Kuwait Number of Registered Vehicles.2021. Available online: https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/kuwait/numberof-registered-vehicles (accessed on 8 of July 2023).

- Hunter, Pamila, Margin of Error and Confidence Levels Made Simple. 2010. Available online: https://www.isixsigma.com/sampling-data/margin-error-and-confidence-levels-made-simple/ (accessed on 7 July 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).