Submitted:

30 August 2023

Posted:

01 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

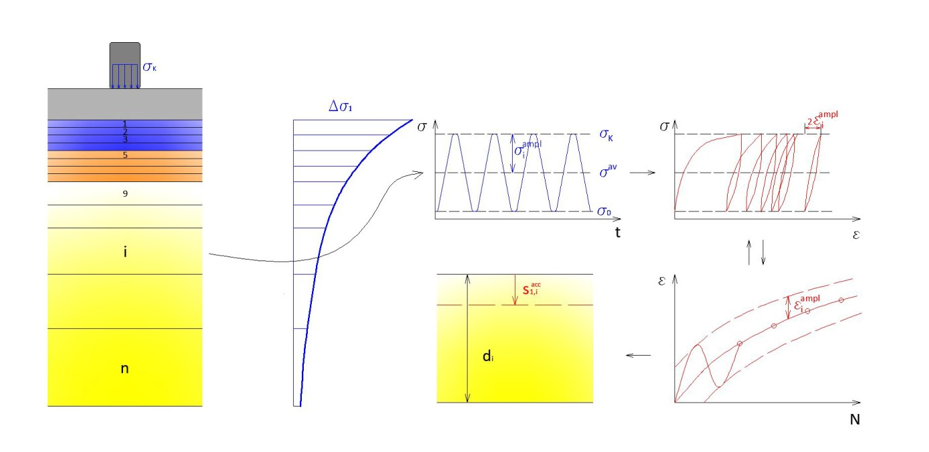

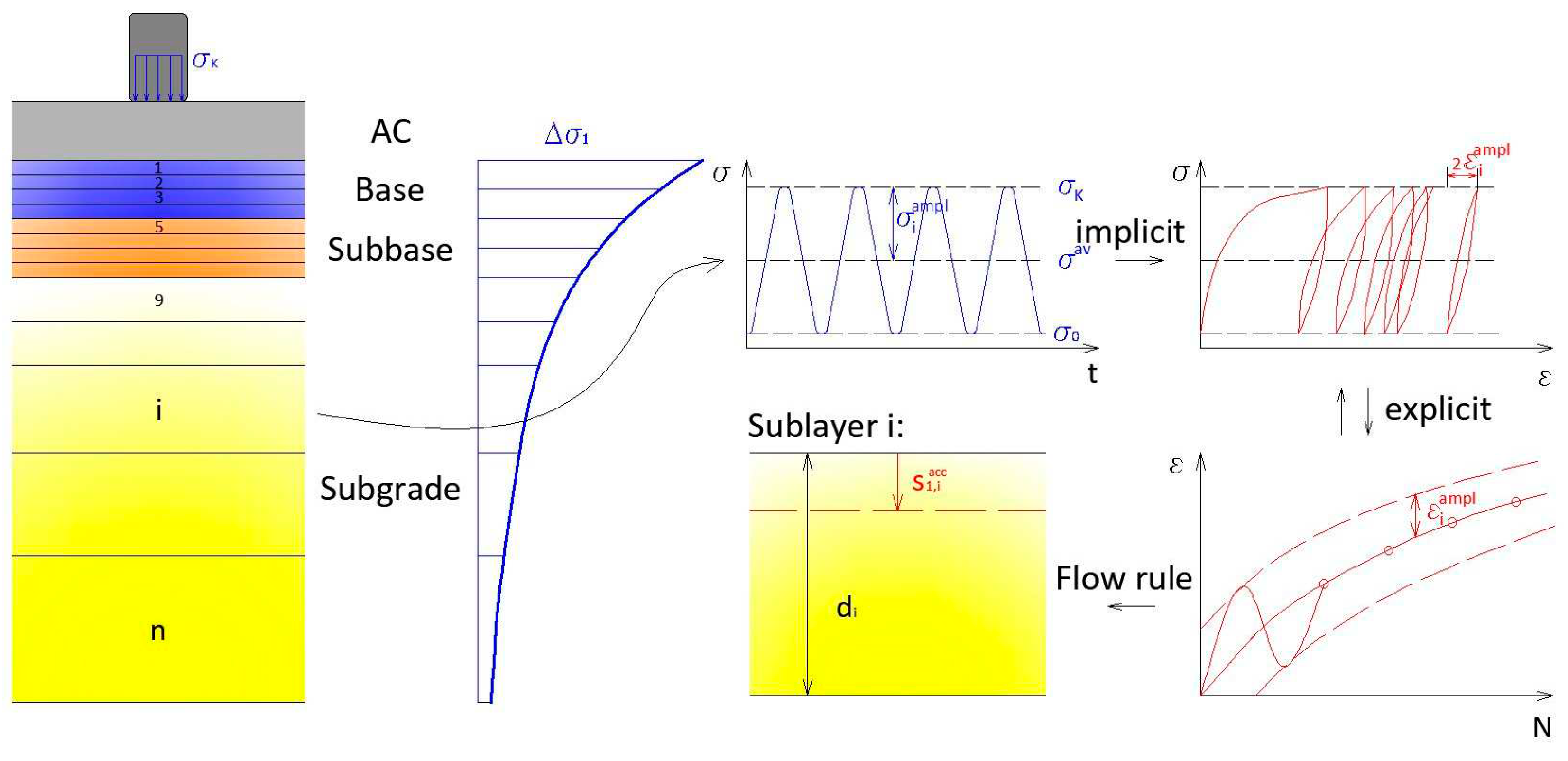

2. Explicit Calculation Method and HCA Model

2.1. Explicit and Implicit Methods

2.2. HCA Model

2.3. Direction of Accumulation

2.4. Determination and Calibration of the HCA Parameters

3. The Developed Layered Calculation Method

3.1. Basic Principles

3.2. Calculation Steps

- the vertical and horizontal stresses due to the own weight of the soil are determined:

- , where is the coefficient of earth pressure at rest by also considering overconsolidation;

- the additional vertical load in each sublayer due to the wheel load is determined as the function of the geometry and stiffness of the sublayer;

- the additional horizontal load is determined from the additional vertical load , where is the coefficient of earth pressure considering overconsolidation and the incremental loading;

- the additional vertical strain is calculated from the additional stresses, mean normal stress, relative density and strain-dependent stiffness: . Because the incremental strain is the function of stiffness, and stiffness is the function of strain, iteration shall be used to determine the strain increment;

- total vertical strain and strain amplitude are calculated as the sum of increments in each sublayer: ;

- total horizontal strain and strain amplitude are calculated from the vertical strain and the ratio of horizontal strains in each sublayer: = ;

- Then, the elastic strain amplitude εiampl is obtained using Equation (1).

- For the base and subbase courses, the above implicit calculation method is simplified to the extent that the stiffness is taken into account with the MR resilient modulus, which is independent of the void ratio and strain level.

- 11.

- the mean normal stress and stress state () is determined in the center line of sublayer „i” then factors independent of the number of cycles fp, fY and are calculated;

- 12.

- in the next step, factors of Equation (4) that depend on the number of cycle are obtained: fampl from the actual εiampl, from the actual gAk and fe from the actual e void ratio;

- 13.

- the accumulated strain rate is calculated using Equation (4). In the case of drained conditions, Equation (2) becomes ;

- 14.

- the strain increment due to cycles is determined by , then ;

- 15.

- calculating the rate of the preloading variable with the actual value of gAk;

- 16.

- the actual value of gAk is updated due to load cycles by ;

- 17.

- vertical strains are calculated using the flow rule , then compression of each sublayer by ;

- 18.

- volumetric strain increment is determined due to cycles, then the new void ratio is obtained by , ;

- 19.

- the characterizing a denser state results in a higher stiffness , thus points d)–g) of the implicit calculation are repeated;

- 20.

- steps b)–j) of the explicit calculation are repeated until the goal value of number of cycles.

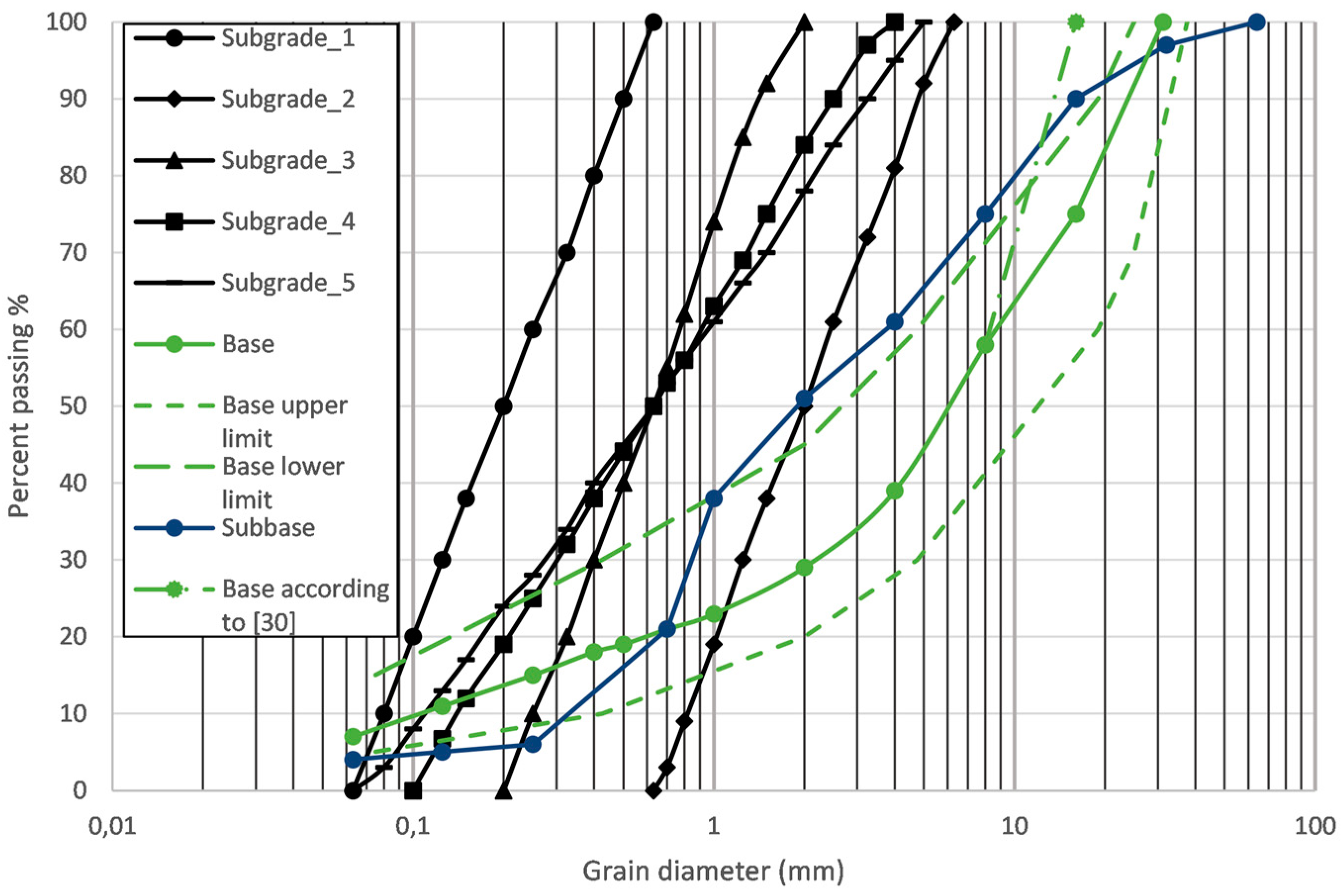

4. Analyzed Pavement Structures and Material Models

4.1. Analyzed Pavement Structures

4.2. Materials and Their Properties

| Layer | d50 (mm) | CU (-) | emin (-) | emax (-) | ρdmax (g/cm3) | e0 (-) | υ (-) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgrade 1 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 0.540 | 0.920 | 1.75 | 0.627 | 0.33–0.36 |

| Subgrade 2 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 0.491 | 0.783 | 1.81 | 0.577 | 0.33–0.36 |

| Subgrade 3 | 0.6 | 3.0 | 0.474 | 0.829 | 1.83 | 0.559 | 0.33–0.36 |

| Subgrade 4 | 0.6 | 5.0 | 0.394 | 0.749 | 1.93 | 0.478 | 0.35–0.38 |

| Subgrade 5 | 0.6 | 8.0 | 0.356 | 0.673 | 1.98 | 0.439 | 0.36–0.40 |

| Subbase | 2.0 | 11.9 | 0.364 | 0.513 | 2.06 | 0.340 | 0.40 |

| Base | 6.3 | 100.0 | 0.230 | 0.440 | 2.30 | 0.188 | 0.40 |

4.3. Material Model of the Implicit Calculation

5. Implicit Calculation Model and Comparative Study

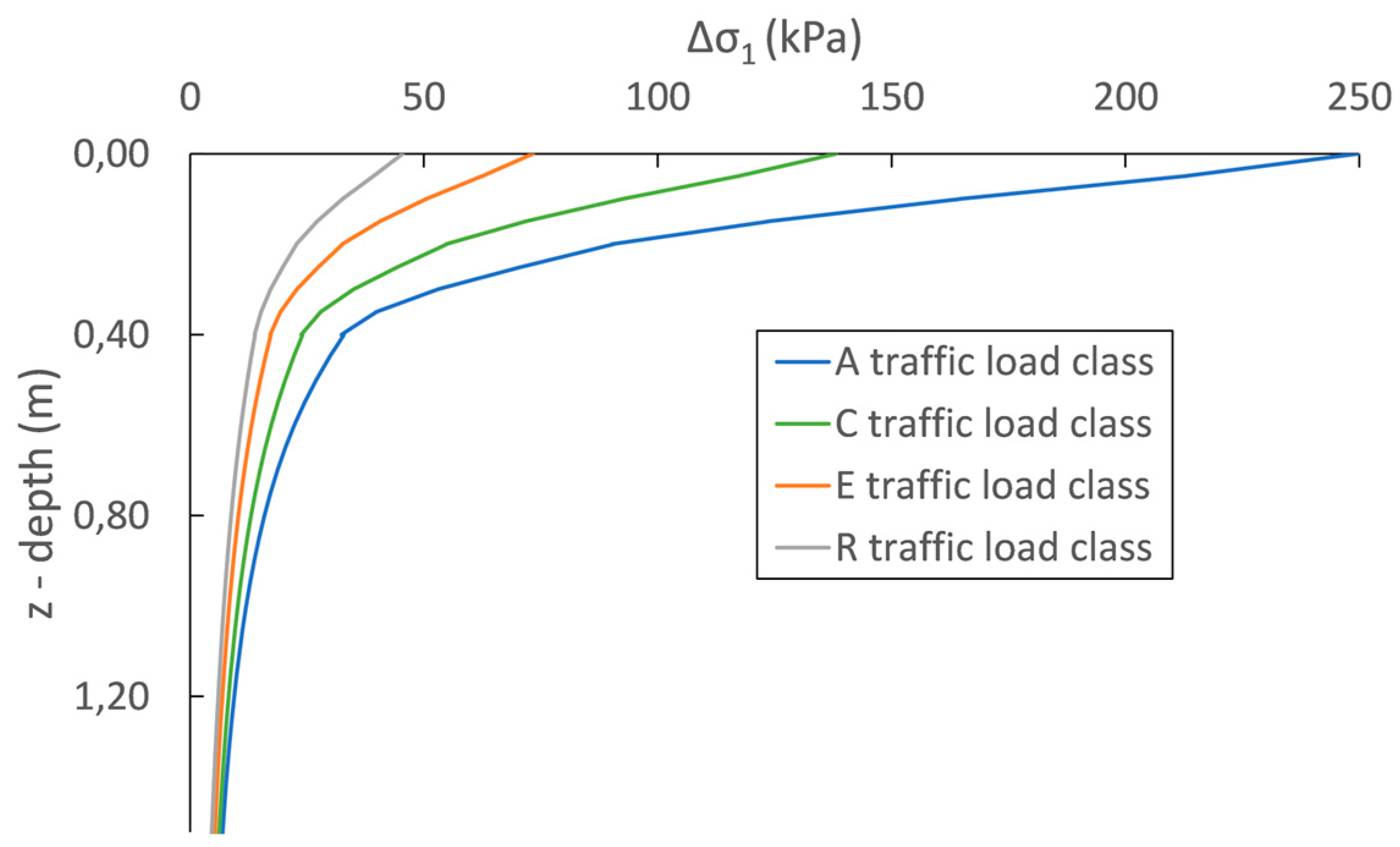

5.1. Vertical Stress Distribution

5.2. Horizontal Strain Ratio

5.3. Coefficient of Earth Pressure

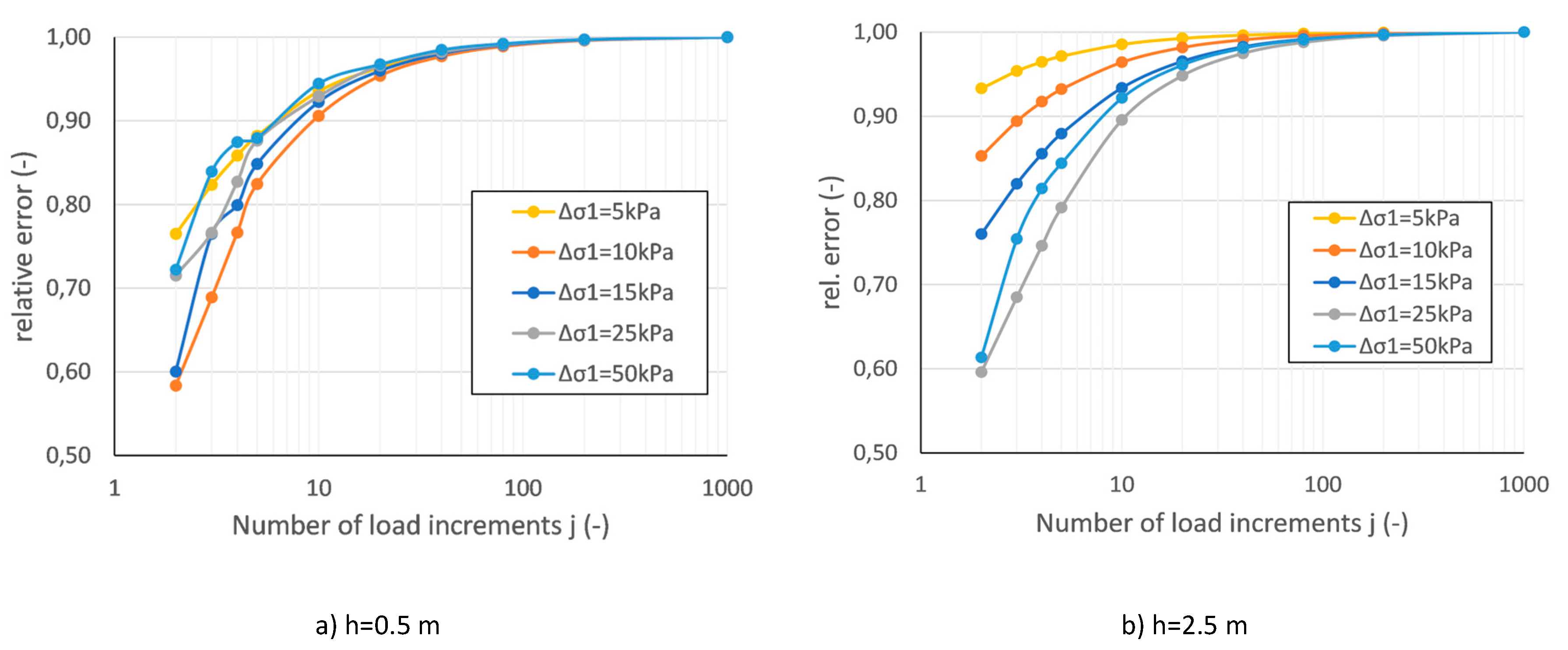

5.4. Number of Load Increments

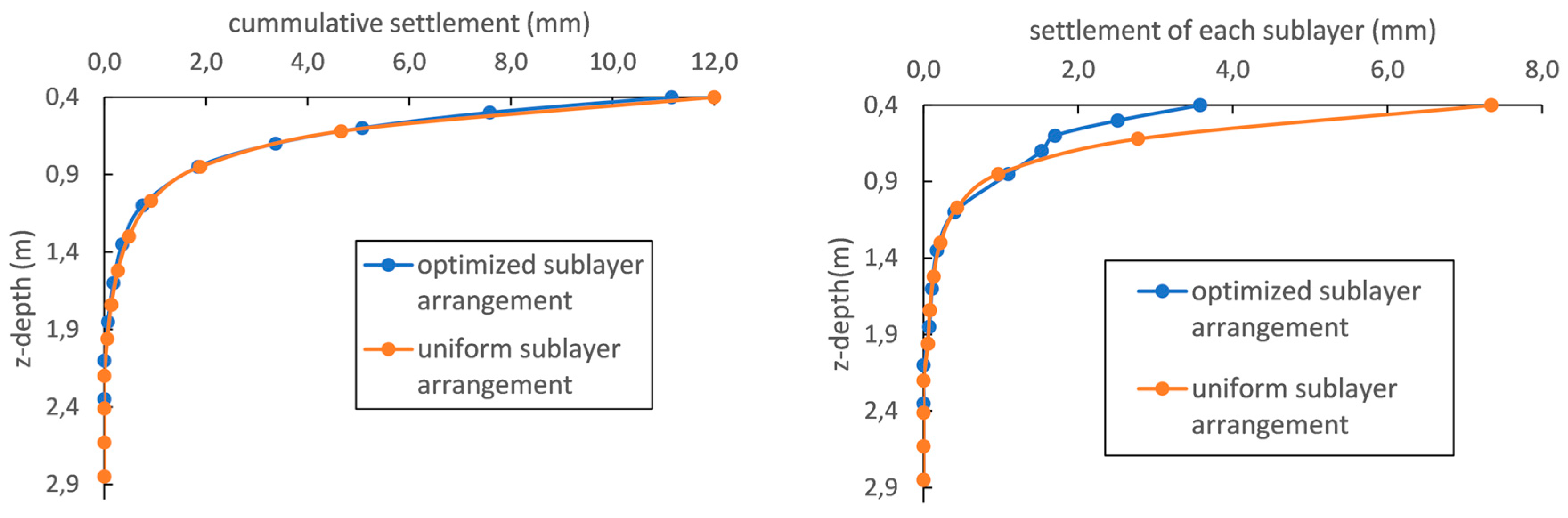

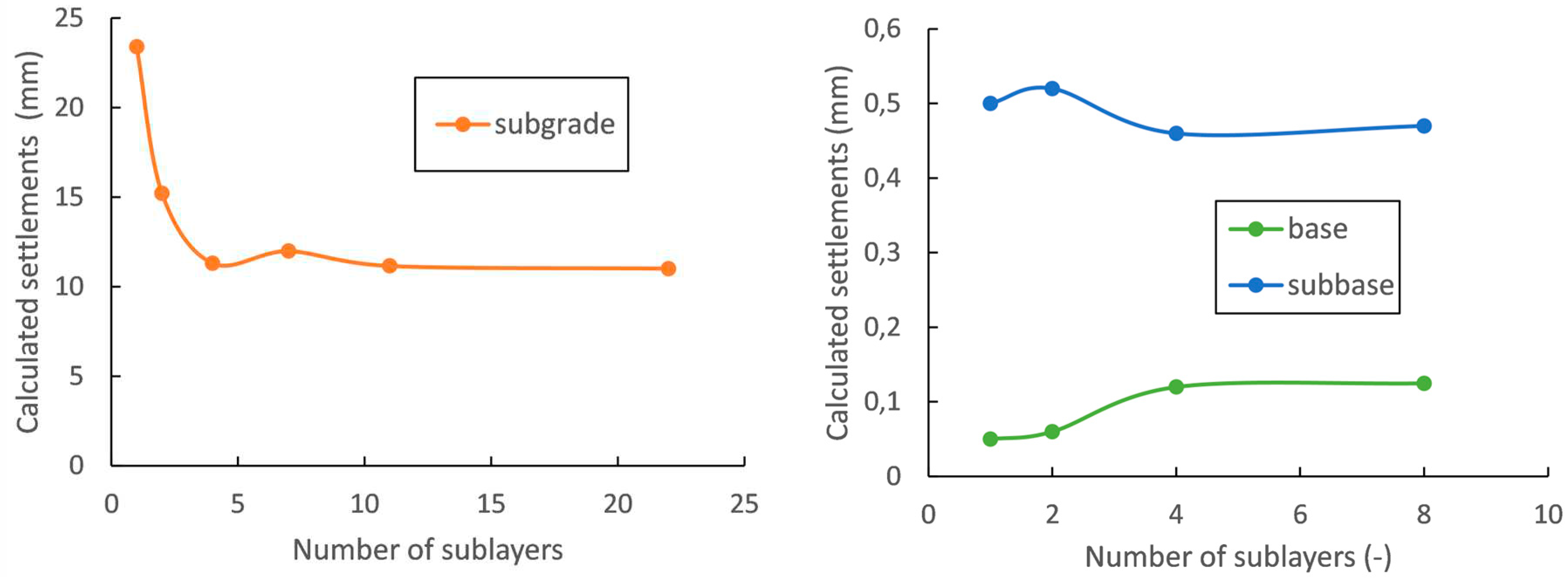

5.5. Number and Arrangement of Layers

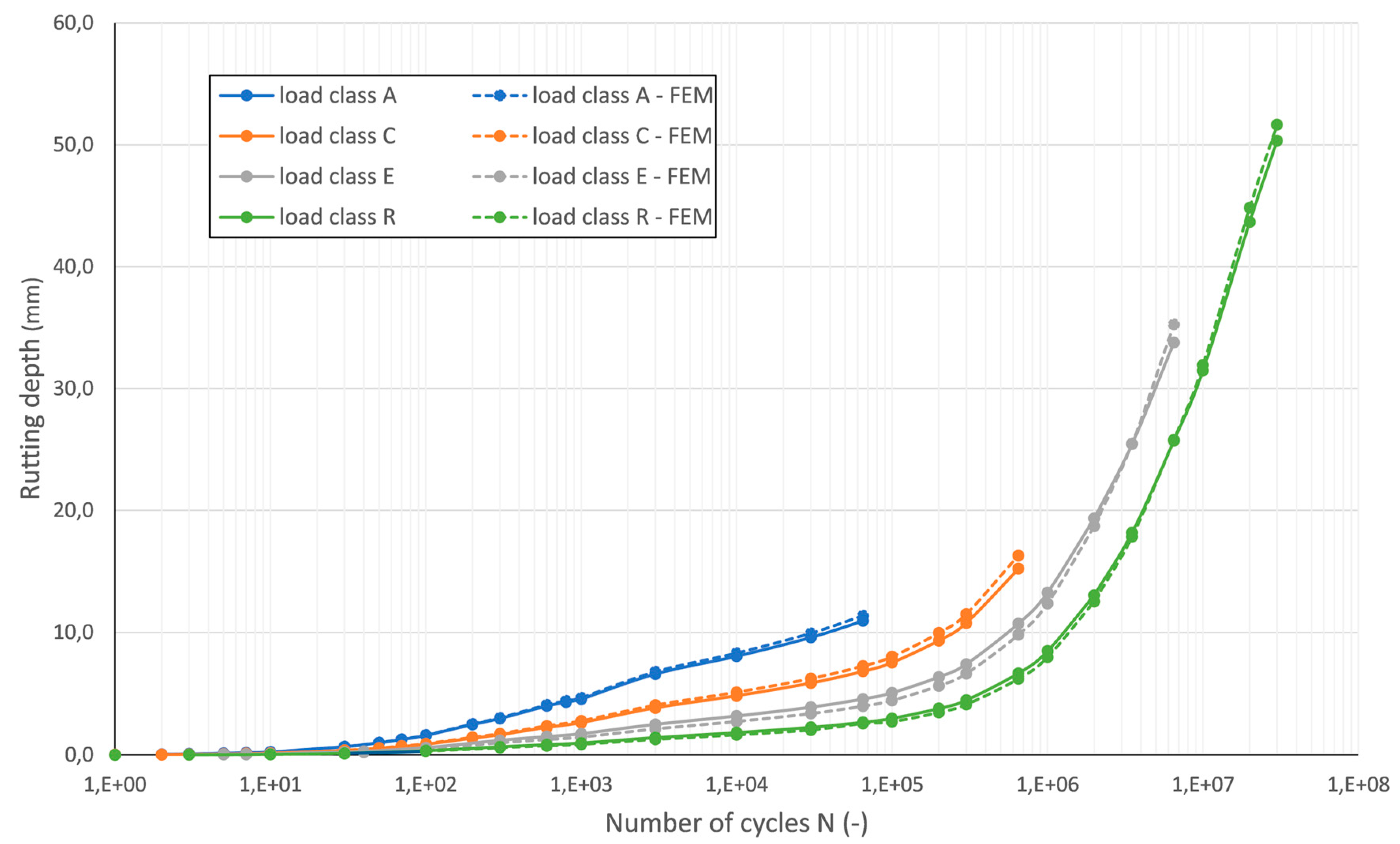

6. Discussion of Layered Model Results

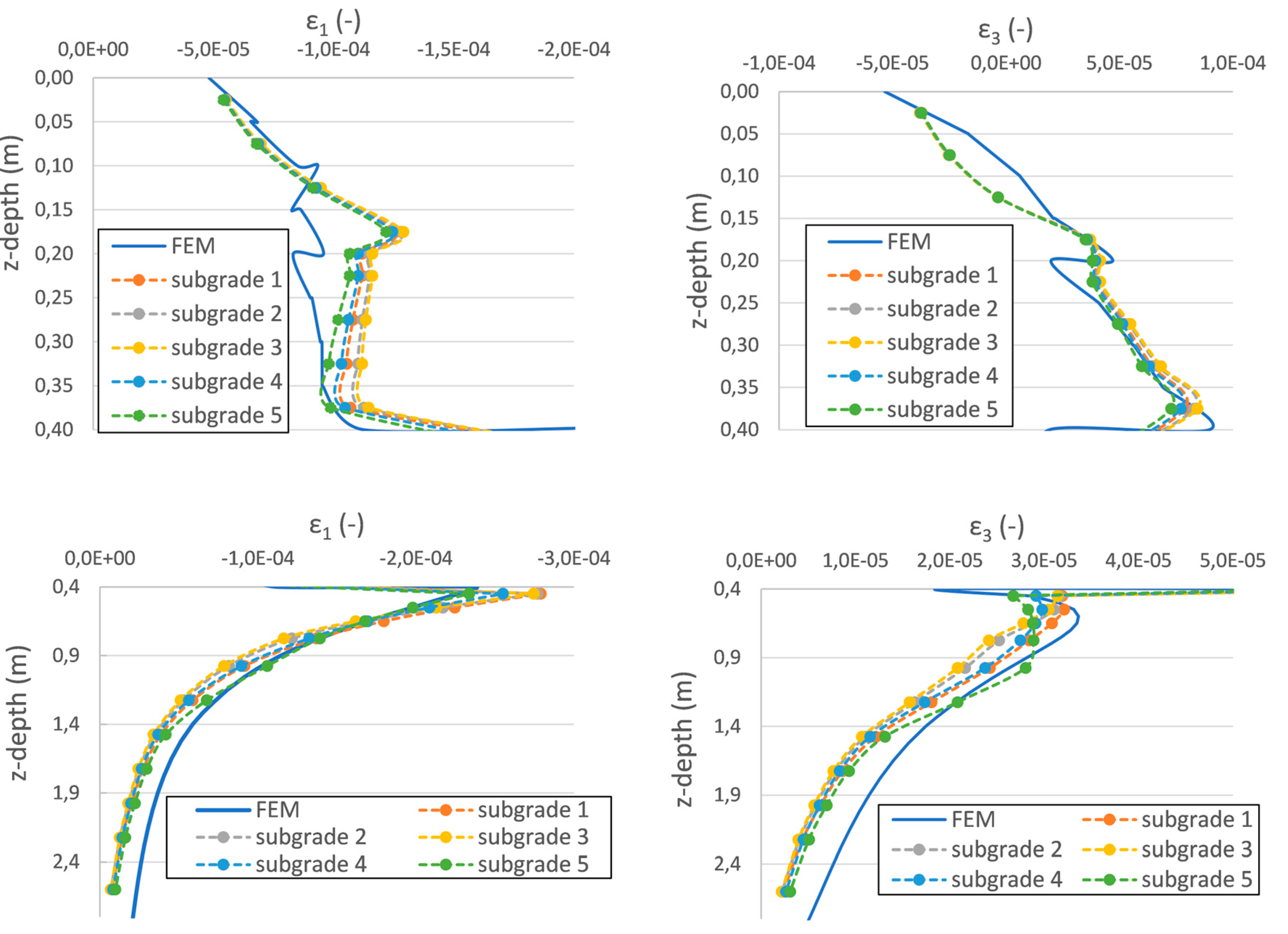

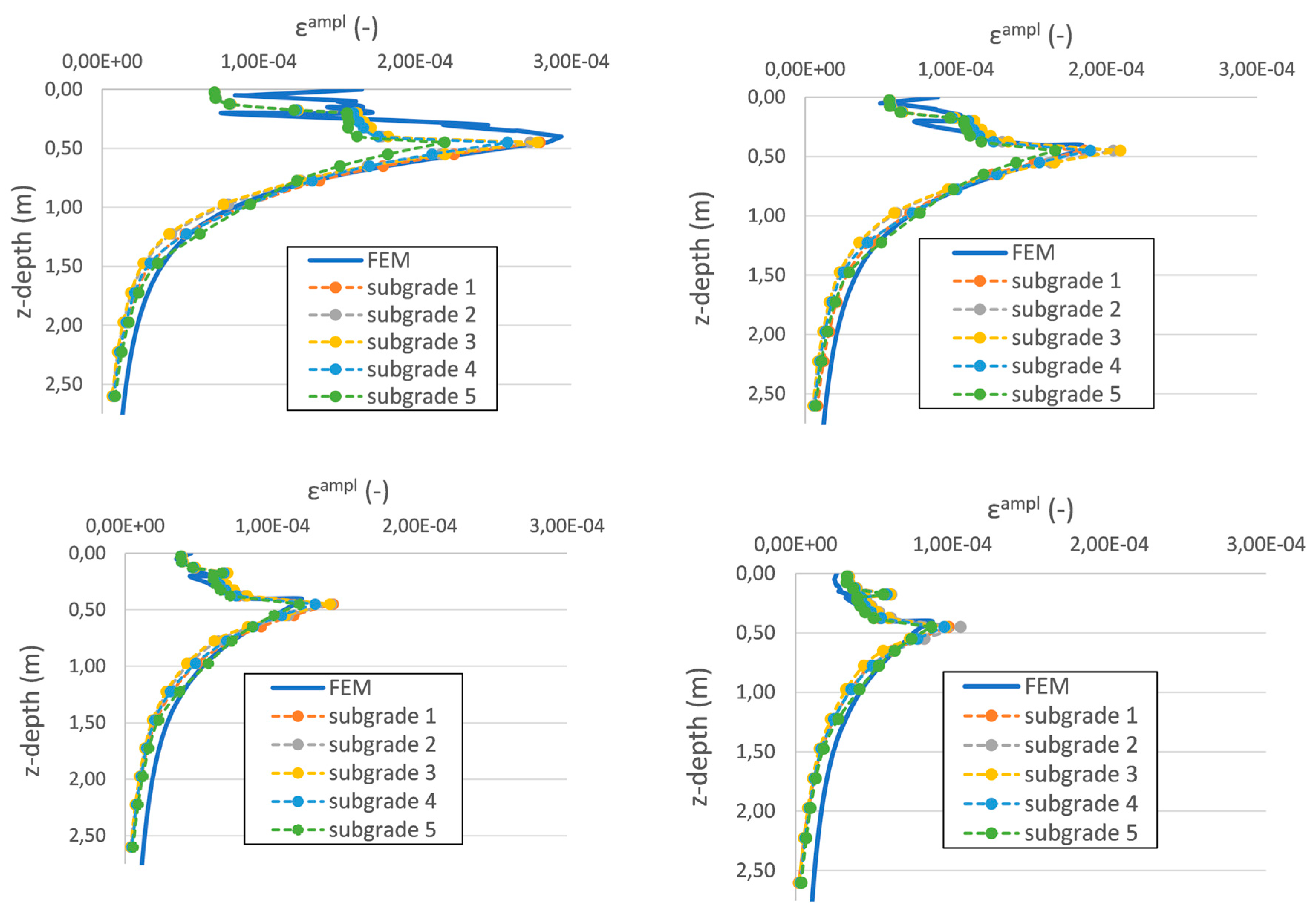

6.1. Implicit Calculation Results

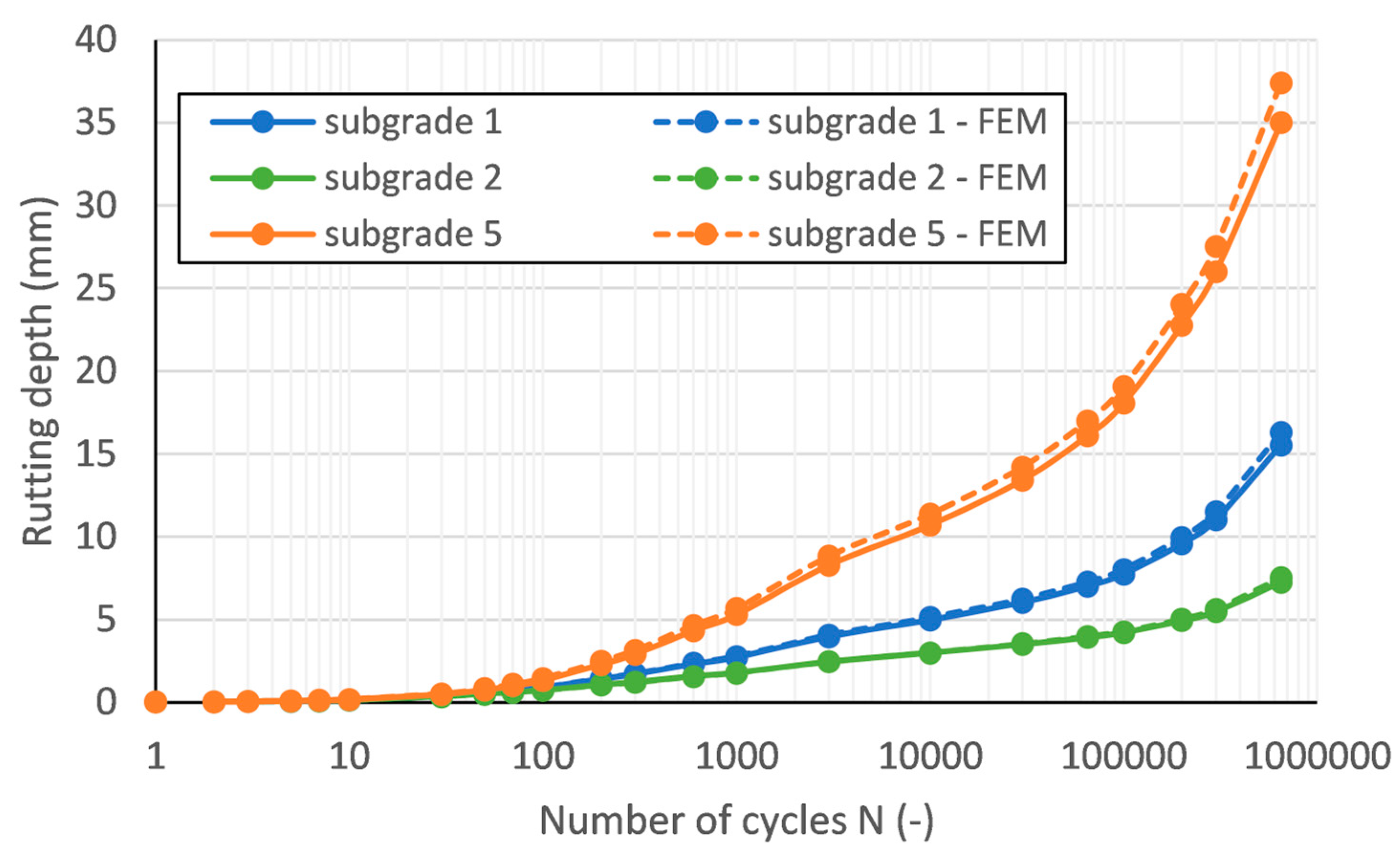

6.2. Comparison of Permanent Deformation Results between Layered and FE Model

6.3. Effect of Traffic Load Class on Permanent Deformations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- e-UT06.03.13 Aszfaltburkolatú Útpályaszerkezetek Méretezése És Megerősítése E-UT06.03.13 (ÚT 2-1.202), Útügyi Műszaki Előírás, (Design of Road Pavement Structures and Overlay Design with Asphalt Surfacing), Road Design and Specification Standard, Hungary, 2017.

- RStO Richtlinie für die Standardisierung des Oberbaues von Verkehrsflächen 2001.

- Powell, W.D.; Potter, J.F.; Mayhew, H.C.; Nunn, M.E. The structural design of bituminous roads. TRRL LABORATORY REPORT 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Shell. SHELL SPDM-PC User Manual. Shell Pavement Design Method for Use in a Personal Computer, Version 1994, Release 2.0; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Little, P.H. The Design of Unsurfaced Roads Using Geosynthetics. Ph.D. dissertation, Nottingham, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gidel, G.; Hornych, P.; Chauvin, J.; Breysse, D.; Denis, A. A New Approach for Investigating the Permanent Deformation Behaviour of Unbound Granular Material Using the Repeated Loading Triaxial Apparatus. BULLETIN DES LABORATOIRES DES PONTS ET CHAUSSEES 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Uzan, J. Permanent Deformation in Flexible Pavements. J. Transp. Eng. 2004, 130, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werkmeister, S. Permanent Deformation Behaviour of Unbound Granular Materials in Pavement Constructions. Ph.D. értekezés, TU Dresden, Drezda, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Niemunis, A.; Wichtmann, T.; Triantafyllidis, T. A High-Cycle Accumulation Model for Sand. Computers and Geotechnics 2005, 32, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichtmann, T. Explicit Accumulation Model for Non-Cohesive Soils under Cyclic Loading; Schriftenreihe des Institutes für Bodenmechanik der Ruhr-Universität Bochum; Bochum, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wichtmann, T.; Niemunis, A.; Triantafyllidis, T. Flow Rule in a High-Cycle Accumulation Model Backed by Cyclic Test Data of 22 Sands. Acta Geotech. 2014, 9, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichtmann, T.; Niemunis, A.; Triantafyllidis, T. On the Determination of a Set of Material Constants for a High-cycle Accumulation Model for Non-Cohesive Soils. International Journal for Numerical and Analytical Methods in Geomechanics 2010, 34, 409–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichtmann, T.; Niemunis, A.; Triantafyllidis, T. Simplified Calibration Procedure for a High-Cycle Accumulation Model Based on Cyclic Triaxial Tests on 22 Sands. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichtmann, T.; Niemunis, A.; Triantafyllidis, T. Strain Accumulation in Sand Due to Cyclic Loading: Drained Cyclic Tests with Triaxial Extension. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 2007, 27, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichtmann, T.; Niemunis, A.; Triantafyllidis, T. Experimental Evidence of a Unique Flow Rule of Non-Cohesive Soils under High-Cyclic Loading. Acta Geotechnica 2006, 1, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichtmann, T.; Triantafyllidis, T. An Experimental Database for the Development, Calibration and Verification of Constitutive Models for Sand with Focus to Cyclic Loading: Part I—Tests with Monotonic Loading and Stress Cycles. Acta Geotech. 2016, 11, 739–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemunis, A. Extended hypoplastic models for soils. habilitáció. INSTITUTES FÜR GRUNDBAU UND BODENMECHANIK DER RUHR-UNIVERSITÄT BOCHUM: Bochum, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wichtmann, T. Soil Behaviour under Cyclic Loading—Experimental Observations, Constitutive Description and Applications. habilitáció. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.S.; Whitman, R.V. Drained Permanent Deformation of Sand Due to Cyclic Loading. Journal of Geotechnical Engineering 1988, 114, 1164–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichtmann, T.; Niemunis, A.; Triantafyllidis, T. Flow Rule in a High-Cycle Accumulation Model Backed by Cyclic Test Data of 22 Sands. Acta Geotechnica 2014, 9, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichtmann, T.; Rondón, H.; Niemunis, A.; Triantafyllidis, T.; Lizcano, A. Prediction of Permanent Deformations in Pavements Using a High-Cycle Accumulation Model. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering 2010, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichtmann, T.; Niemunis, A.; Triantafyllidis, T. Improved Simplified Calibration Procedure for a High-Cycle Accumulation Model. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 2015, 70, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichtmann, T.; Niemunis, A.; Triantafyllidis, T.H. Validation and Calibration of a High-Cycle Accumulation Model Based on Cyclic Triaxial Tests on Eight Sands. Soils and Foundations 2009, 49, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichtmann, T.; Triantafyllidis, T. Inspection of a High-Cycle Accumulation Model for Large Numbers of Cycles (N=2 Million). Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 2015, 75, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukkezen, T. Implementation And Inspection Of A High-Cycle Accumulation Model. TU Delft, Delft, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Häcker, A. Erweiterung eines Lamellenmodells für zyklisch belastete Flachgründungen, (Extension of a Laminal Modell for Cyclic Loaded Foundations). Graduation Thesis, Karlsruher Institute für Technologie, Institute für Bodenmechanik und Felsmechanik, Karlsruhe, Germany, 2013. (In German). [Google Scholar]

- Wöhrle, T. Überprüfung und Entwicklung einfaher Ingenieurmodelle für Offshore-Windenerigealagen auf Bass eines Akkumulationsmodells. (Examination and Development of Simplified Engineering Oriented Model for Offshore Wind Turbins on the Basis of an Accumulation Modell). Graduation Thesis, Karlsruher Institute für Technologie, Institute für Bodenmechanik und Felsmechanik, 2012. (In German). [Google Scholar]

- Zachert, H. Zur Gebrauchstauglichkeit von Gründungen für Offshore-Windenergieanlagen. (On the Usability of Foundations for Offshore Wind Turbins). PhD Thesis, Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT), Karlsruhe, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Káli, A. Ipari Padlók Ágyazatként És Útépítési Védőrétegként Használt Durvaszemcsés Talaj Sajátmodulusának Numerikus Modellezése. (Numerical Analysis of the Bearing Capacity Modulus of Course Soils Used in Pavement and Industrial Slab Layers). BSc Thesis, Budapest University of Technology and Economics, (In Hungarian). 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rondón, H.A.; Wichtmann, T.; Triantafyllidis, T.; Lizcano, A. Hypoplastic Material Constants for a Well-Graded Granular Material for Base and Subbase Layers of Flexible Pavements. Acta Geotech. 2007, 2, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Útügyi Lapok. Kutatási Jelentés: Tervezési Útmutató: Aszfaltburkolatú Útpályaszerkezetek Méretezésének Alternatív Módszere; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vámos, M.J.; Szendefy, J. Overconsolidated Stress and Strain Condition of Pavement Layers as a Result of Preloading during Construction. Period. Polytech. Civil Eng. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichtmann, T.; Triantafyllidis, T. Effect of Uniformity Coefficient on G/Gmax and Damping Ratio of Uniform to Well-Graded Quartz Sands. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering 2013, 139, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichtmann, T.; Triantafyllidis, T. Influence of the Grain-Size Distribution Curve of Quartz Sand on the Small Strain Shear Modulus Gmax. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, ASCE 2009, 135, 1404–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllidis, T.; Niemunis, A.; Kudella, P.; Wichtmann, T.; Solf, O.; Wienbroer, H.; Zahert, H.; Chrisopoulos, S. Abschlussbericht 0327618 zum Verbundprojekt "Geotechnische Robustheit und Selbsteilung bei der Gründung von Offshore-Windenergieanlagen, technischer Bericht; Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT): Karlsruhe, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- AASHTO. AASHTO Guide for Design of Pavement Structures. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, 1993; ISBN 978-1-56051-055-0. [Google Scholar]

- Nübel, K.; Karcher, C.; Herle, I. Ein Einfaches Konzept Zur Abschätzung von Setzungen. Geotechnik 1999, 4, 251–258. [Google Scholar]

| Influencing parameter | Function | Material constants |

|---|---|---|

| Strain amplitude | ||

| Cyclic preloading | ||

| Average mean pressure | ||

| Average stress ratio | ||

| Void ratio |

| Traffic load class | Design traffic (million axles) | Thickness of Base course (cm) | Thickness of AC-layer (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.03–0.1 | 20 | 10 |

| B | 0.1–0.3 | 20 | 12 |

| C | 0.3–1.0 | 20 | 15 |

| D | 1.0–3.0 | 20 | 18 |

| E | 3.0–10.0 | 20 | 22 |

| K | 10.0–30.0 | 20 | 25 |

| R | Over 30 | 20 | 29 |

| Layer | Campl | Ce | Cp | CY | CN1 | CN2 | CN3 | fcc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgrade 1 (L26) | 1.70 | 0.513 | 0.47 | 2.26 | 5.49 10−3 | 1.30 10−2 | 2.38 10−5 | 32.76° |

| Subgrade 2 (L19) | 1.70 | 0.466 | 0.21 | 2.98 | 2.11 10−3 | 2.77 10−2 | 1.22 10−5 | 34.73° |

| Subgrade 3 (L12) | 1.70 | 0.450 | 0.41 | 2.60 | 3.88 10−3 | 1.54 10−2 | 2.05 10−5 | 33.20° |

| Subgrade 4 (L14) | 1.70 | 0.374 | 0.41 | 2.60 | 8.44 10−3 | 6.72 10−3 | 3.21 10−5 | 33.20° |

| Subgrade 5 (L16) | 1.70 | 0.338 | 0.41 | 2.60 | 1.53 10−2 | 5.67 10−3 | 4.53 10−5 | 33.20° |

| Base | 1.10 | 0.070 | -0.22 | 1.80 | 5.20 10−4 | 0.03 | 1.30 10−5 | 44° |

| Subbase | 1.10 | 0.204 | -0.22 | 1.80 | 5.20 10−4 | 0.03 | 1.30 10−5 | 42° |

| Layer | k1 (psi) | k1 (MPa) | k2 (-) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Granular base course | 3000–8000 | 20.6–55.2 | 0.5–0.7 |

| Granular subbase course | 2500–7000 | 17.2–48.3 | 0.4–0.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).