1. Introduction

In recent years, e-commerce, as a product of information technology for business operations, has been applied in many ways.This is especially true since the outbreak of COVID-19 in early 2020. Since then, Internet channels have played an important role in confronting the supply chain challenges imposed by the pandemic, stimulating consumption recovery and maintaining both the global supply chain and industrial chain.According to an e-commerce trading platform survey released by China’s National Bureau of Statistics, Chinese annual e-commerce transactions rose by 4.5 per cent, reaching CNY37.21 trillion in 2020,compared to 2019 (Zhu et al. 2023).To avoid the risk of a single channel, many suppliers have opened up their own online channels to sell the same products as offline retailers, which is known as supplier encroachment. Companies such as Apple, Huawei, and Samsung, have established their direct channels, helping them to implement self-operated distribution channels (Xia & Niu, 2019).The convenience of an Internet channel also provides consumers with more shopping options. In fact, some consumers may first visit the brick-and-mortar store to experience the retail service, but finally purchase the product from an online store at a lower price(Mehra et al., 2018).

By opening up direct online sales channels, it brings negative impact on retailers' sales from two aspects. The first is the cannibalization effect. When demand is constant, due to the existence of two types of sales channels in the market, the sales of products in the online channel will crowd out some of the sales originally belonging to the retail channel. Considering the price advantage of online channel sales, when the product substitution degree in both channels is high, retailers will lose potential consumers due to the supplier's channel invasion (Zhang et al. 2022). The second is the service spillover effect. Retailers provide sales services to consumers to promote product sales, but consumers who receive the services are ultimately influenced by various factors and make purchases through online sales channels. Obviously, the service spillover effect has narrowed the service gap between the two channels, promoted the improvement of online channel profitability, and physical stores are gradually regarded as "exhibition halls" of online sales channels. This worsens cooperative relationship between the supply chain members(Bernstein et al., 2009). Moreover, there is a view that even if the supplier establishes an inactive direct channel, retailers will be worse off as a result of supplier encroachment(Yang et al., 2018).Thus, retailers often regard the direct channel as an enormous threat, and the conflicts in a dual channel system can grow serious(Cai, 2010; Huang et al., 2018).

On the other hand, as environmental and energy-related problems have become more and more prominent, many organizations seek to achieve sustainable development by curbing emissions.In March 2021, the People’s Bank of China held a forum on optimizing and adjusting the credit structure of twenty-four major banks, preparing to set up carbon emission reduction support tools to further bolster the investment in carbon abatement programs. In this context, some corporations are taking actions to enhance their environmental protection efforts.For instance, multinational companies including Microsoft, Nike, Starbucks, and Unilever have formed a new consortium called Transformto Net Zero, which is devoted to sharing information and resources for reducing carbon emissions.Yet, here as well – although the significance of sustainable development has been widely recognized –the suppliers’ green strategies may encourage free riding. If only emission reduction in production is considered, a retailer can expand their market share and gain a greater competitive advantage without paying any emission abatement-related costs(Hong & Guo, 2019). In other words,low-carbon product distribution in a dual-channel supply chain may involve a bidirectional free riding question, which raises additional questions regarding the relationship between green supply chain members.

In the offline market, brick-and-mortar stores cannot only provide customers with immediate product acquisition but also offer show rooms with product demonstration, the ability to sample products,the presence of a sales clerk, etc.(Mehra et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2018).This provides consumers with a more engaging consumption experience.Low-carbon promotions in this offline channel may improve the sales of products and therefore contribute to carbon emission reductions. However, the current literature on the sale and channel selection of products focuses almost exclusively on pricing and emission reduction decision-making in dual-channel supply chains, neglecting the effect of service spillovers. To our knowledge, there is no prior study that has studied its effect one mission reduction strategies and channel decisions, which we might expect to differ from conventional, dual-channel chains.With this study, we hope to provide a theoretical reference for these phenomena by exploring the following issues:

- (1)

How do consumers' low-carbon preferences and service sensitivity affect suppliers' emission reduction and channel selection decisions?

- (2)

Under a dual-channel structure, how do service spillovers affect the decision-making of supply chain members?

- (3)

Do retailers need to minimize their service costs when suppliers encroach by opening an Internet channel?

- (4)

What effect do carbon cap-and-trade (CCT) mechanisms and/or low-carbon policies have on the optimal decision of service levels and emission abatement levels? Do low-carbon policies motivate supplier encroachment?

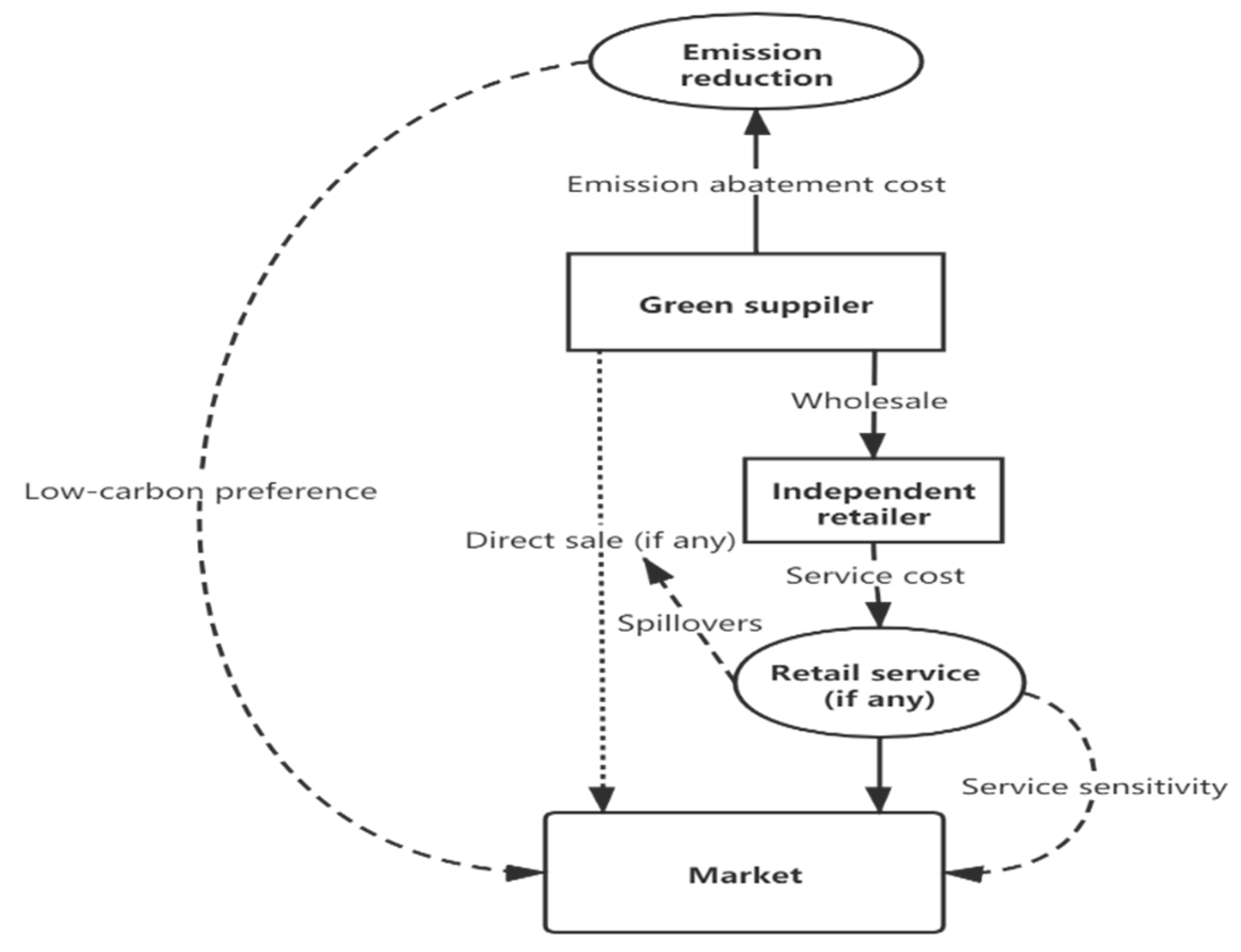

To answer these questions, this paper considers a two-echelon supply chain consisting of one supplier who plans to slash emissions and one retailer who can provide services for consumers.The supplier also has the option to sell products directly to consumers by opening an Internet channel;under the dual-channel structure, the retailer's inputs on services to customers may spillover to and benefit the direct channel,as shown in

Figure 1. On this basis,we develop four models based on different channel structures and service strategies.

Our research contributes to the literature in five ways. First, this paper studies the strategies of channel selection and emission reduction in a supply chain with consideration for the retail service and its spillover effects.Second,we deduce that under encroachment,the supplier is better off, and the level of emission reductions is improved, and consumer low-carbon preferences can offset some of the adverse effects of supplier encroachment on retailers Third, contrary to popular belief, the greater the service spillovers, the more likely a retailer is to get returns from supplier encroachment.However,supplier encroachment does lead to a decline in the service level provided by the retailer, and retailer profits,when the spillover effect is relatively weak.Finally, based on an extended discussion of equilibrium outcomes under a CCT mechanism,we establish the theoretical relationship between the carbon price and supplier encroachment.

Our research is presented as follows:

Section 2 reviews relevant studies, and

Section 3describes the model and related assumptions. Then, Section4provides the optimal decision and equilibrium analysis for four scenarios. In Section5, we further discuss the channel decision and service strategy with a numerical analysis, andSection6 presents an extended discussion on our models under a CCT mechanism. Finally, we summarize our study and offer insights into possible avenues for future research in Section7. In addition, we attach proofs of our conclusions in

Appendix A, and provide variable annotations in

Appendix B.

2. Literature review

This research addresses issues of consumers' low-carbon awareness, channel decisions in a supply chain, and the spillover effect of retail services. Here,we review relevant literature and discuss current research problems to emphasize our contributions.

2.1. Consumers’ low-carbon awareness

As consumer awareness of environmental matters increases, more and more enterprises are devoted to providing and promoting ‘green’ products(Liu et al., 2012).Many studies have highlighted the effect of consumers' low-carbon preference on generating market demand for green products. Adaman et al. (2011), using a face-to-face questionnaire of 2422 respondents, finds that young and educated people are relatively more willing to purchase low-carbon products compared with the general population. Xia et al. (2018) incorporates social preferences and environmental consciousness into carbon emission reduction decision research in the context of a two-echelon supply chain. They find that the strong environmental awareness of consumers plays a positive role in motivating the enterprise to provide more environmentally-friendly products.

From the standpoint of sustainable management, the requirement of low-carbon operations will necessarily influence operational decisions and supply chain coordination.Thus, a large body of literature examines pricing and emission reduction strategies of supply chains which distribute green products. Ghosh and Shah (2012) examines a fashion supply chain model under different carbon emission abatement modes and analyze the impact of channel power structure on price, profit, and emission reduction levels. Beyond emission abatement in production,green strategies in other operating stages have been considered by some scholars, such as in green product design(Hong & Guo, 2019; Zhao & Zhu, 2018), inventory strategy (Benjaafar et al., 2013; Hua et al., 2011),and consumer purchase behavior(Amit Kumar, 2021; Feng et al., 2017). Moreover, some scholars have tried to motivate an increase in emission reductions by coordinating activities across the supply chain. Wang et al. (2016)proposes a cost-sharing versus whole sale price premium contract to coordinate a two-echelon supply chain and achieve a higher carbon emission reduction rate. Similarly, Peng et al.(2018)discusses the performance of a green supply chain with a quantity discount contract and a conventional revenue-sharing contract, and design a new revenue-sharing contract based on an emission reduction subsidy to coordinate across the supply chain. However, this research is mostly restricted to distributing green products through the traditional, brick-and-mortar channel.In this paper, we take consumers' low-carbon preference and service sensitivity into account and explore the impact of supplier encroachment on emission reduction strategies in a supply chain.

2.2. Channel decisions in a supply chain

Since the rapid growth of e-commerce, it is increasingly important to explore whether the launch of direct channels benefits members of the supply chain. Some scholars have proposed that supplier encroachment not only enhances supplier profits, but that retailers could also benefit from the increase in marginal profit(Arya & Mittendorf, 2013; Chiang et al., 2003; Yoon, 2016). However, another view has been raised that considers more specific factors in the competition between channels, such as product quality(Jamali & Rasti-Barzoki, 2018) and bargaining power(Yang et al., 2018), which indicates that supplier encroachment definitely can hurt retailers.

The discussion of this issue has also appeared in research on green supply chains. Li et al. (2016)examines the pricing and emission reduction strategies of dual-channel supply chains their models and explore the necessary conditions for the existence of a dual-channel green supply chain.Further, Ji et al. (2017) compares the manufacturer's emission abatement strategy with a joint emission reduction strategy in both single-channel and dual-channel supply chains.They report that if the degree of consumers' low-carbon sensitivity is relatively high, a joint emission reduction strategy in both channels is beneficial for both the supplier and the retailer. In addition, Ranjan and Jha(2019) explores pricing and green decisions in a dual-channel supply chain and coordination through a surplus profit-sharing mechanism. Zhang et al. (2020)investigates carbon emission abatement and encroachment decisions under three different decision sequences. Their results indicate that with supplier encroachment,the retailer is always worse off unless consumer's low-carbon preference is sufficiently high.Our work is most related to Ranjan and Jha(2019), which considers the retailer's efforts in sales strategies, including customer services, in the competition between channels.However,they assume that the retail channel only distributes non-green products and therefore ignores the cross-channel effect of the sales effort. Our study examines the spillover effect of retail services and its impact on emission reduction and channel decisions.

2.3. Service spillovers

Our study also involves multi-channel competition subject to the service spillover effect. Previous research has extensively discussed the impact of service spillovers on the traditional sales channel. Shin(2007)indicates that service spillover benefits both service providers and “free riders”, which is a win-win result.In contrast, Zhou et al. (2018)investigates the pricing and service strategy of dual-channel supply chains, but concludes that “free riding” always has a negative impact on the retailer's profits. Xia and Niu(2019) integrates the two views presented above and explores the equilibrium results of the retailer as the leader and follower respectively. The results show that strong service spillovers could lead to Pareto improvement(Pareto improvement means that make at least one person better without making anyone's situation worse.) if the retailer is not the leader. Furthermore, some studies have proposed solutions to reduce the negative effect of service spillovers. Chen et al. (2012)proposes a compensation agreement to coordinate a dual-channel supply chain subject to service spillovers. Mehra et al.(2018), based on a comparative analysis between service strategies, demonstrates that retailers can pursue service differentiation as a long-term strategy to offset the impact of product display strategy in a physical space.In recent studies,some scholars hold that cross-channel consumers are driven by different motivations,and so they combine the influence of "offline show rooming" and "online web rooming" in sales channel research(Flavián et al., 2020; Jing, 2018). The studies discussed above have mostly focused on exploring retailers’ strategies under service spillover effects.There is scant literature on the strategies of the supplier(including strategies for carbon emission reductions) in the case they are subject to the service spillover effect. Hence, here we mainly focus on the supplier-dominant case and try to determine whether service spillovers motivate suppliers’ greening strategies.These results can offer managerial insights for decision-makers to implement sustainable development strategies in the context of e-commerce.

Our study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, we establish a two-echelon supply chain,in which the supplier is a Stackelberg leader and the retailer a follower, differing from the model of a follower-supplier and a dominant-retailer.Second, we combine emission reduction and channel decisions in our model, in contrast to the current literature in which emission reduction and channel decisions are analyzed separately. Third, our study investigates the impact of service spillovers on emission reduction and channel decisions.To the best of our knowledge,our paper is the first to combine service spillovers in decisions of emission reduction and channel options.

3. The Model

We consider a supply chain consisting of a supplier (she) and an independent retailer(he). The supplier, as the Stackelberg leader of the green supply chain,needs to first determine the emission reduction level

and wholesale price

at first. Meanwhile, if a direct channel is established(with the fixed cost

),the supplier must also decide her output quantity

. After that, the retailer buys at wholesale with the order quantity

, and decides his service levels

(if any).Ultimately, consumers buy the product through either the direct channel (if it exists) or the retail channel. The related variables are summarized in

Table 1.

This paper analyzes the influence of retail services and the service spillover effect on emission reduction and channel decisions. Hence, we ignore the model of single direct channel, where the retailer is not involved in the supply chain. On this basis, we discuss four different scenarios: a setting with and without retail services under a single-channel and a setting with and without retail services under a dual-channel structure. To establish ou model, we make the following assumptions, with reference to the literature:

Assumption 1. The unit production cost

is a non negative constant, and the inventory cost is ignored. The total carbon emission of unit production is related to

, and a higher amount of emission reduction

will increase the unit cost of carbon abatement(Du et al., 2013). Thus, the cost function of emission reduction is denoted as

(Peng et al., 2018), where

represents the cost coefficient of emission abatement. In order to ensure the profit functions are concave, we assume that

(see

Appendix B), which followsWang et al. (2016) and Hong and Guo(2019). The service cost function is denoted by

, where

represents the retail service level, and

is the cost coefficient of services which is normalized in the model to emphasize the impact of the emission reduction cost.

Assumption 2. The potential demand of the market is sufficient, and consumers not only have low-carbon awareness but are also glad to receive the consumer services from the retailer. Meanwhile, consumers are able to learn about a product's degree of carbon abatement through a low-carbon label system (Yalabik & Fairchild, 2011). In the presence of an Internet channel, some consumers may first experience retail services in brick-and-mortar stores,but eventually choose cheaper products from an online store. On this basis, we follow Xia and Niu (2019)in assuming that the service activities in the retail channel may spill over to the Internet channel with a certain spillover degree (). Furthermore, we assume that and can be observed by the supplier.

Assumption 3. The substitution degree also indicates the degree of competition between the retail channel and the direct online channel, and we assume that one channel cannot be completely replaced by the other ().

Assumption 4. When a dual-channel coexists in the market, the utility function for consumers is

, where

and

represent consumers' low-carbon preference and service sensitivity respectively (

). On this basis, consumer demand for the low-carbon product can be captured by the inverse demand function as follows:

4. Equilibrium solutions and discussions in four scenarios

4.1. Single-channel structure

We consider a benchmark setting in which the product only sells via the traditional retail channel. At first, the supplier determines her green level

and the whole sale price

for the retail channel. Subsequently, the retailer decides his order quantity

and services level

(if any). Under the single-channel structure, the profit function of the retailer and the supplier are:

We use "

" to denote no retail services. In this scenario, the retailer's optimizes decisions through the following objective function:

The optimization of Eq (5) yields the following optimal order quantity:

. Then, substituting

into Eq (3)leads to the supplier's objective function as follows:

The first-order condition of Eq (6) yields the optimal wholesale price and the optimal emission reduction level as follows:

;

.Then,substituting(

,

) into

, Eq (5), and Eq (6), leading to the equilibrium outcomes of scenario

as shown in

Table 2.

Second, we use "

"to denote a setting with retail services. In scenario

,the retailer needs to decide the order quantity

and the service level

to maximize his profits. On this basis, the objective function of the retailer is determined as follows:

The first-order condition of Eq (7)yields the optimal order quantity and the optimal service level as follows:

. Substituting

and

into Eq (3) leads to the supplier's objective function as follows:

Similarly, we can deriveand from Eq (8), and then the equilibrium outcomes of scenariocan obtained by substituting (,) into ,, Eq(7), and Eq (8).

Lemma1. When the supplier only distributes through the direct channel, the equilibrium outcomes are shown in

Table 2.

Proposition1. Under the single-channel structure, both the retailer and the supplier will be better off from the presence of retail services. The equilibrium outcomes of the two scenarios are compared as follows:; ;; .

Proposition1indicates that the optimal emission reduction level and profits of supply chain members are positively affected by the presence of services under a single-channel structure. Specifically, the sales growth in brick-and-mortar stores also sees the supplier benefit from the increase in orders in the retail market(i.e.,). On this basis, the retailer can compensate for the emission abatement investment of the supplier by attracting more consumers to buy green products. This compensation fully encourages green production, even if suppliers are not directly involved in providing services, and still promote the improvement of the optimal emission reduction level (i.e.,). Ultimately, retail services further expands the retail market when consumers have both a low-carbon preference and service sensitivity, resulting in a win-win outcome.

Corollary 1.(i),,,;

(ii),,..

Corollary 1states that the retailer will take the degree of greenness as the major selling point for the promotion of low-carbon products when consumers have a strong environmental consciousness. As increases, the retailer has more incentive to make their services available for customers, thus promoting the green product more effectively through pre-sale services under the single-channel structure (i.e., ). However, if consumers are more sensitive to product prices(i.e., decreases and approaches 0),the retailer will order less and reduce service costs to adjust retail price. This is also the reason that the optimal service level decreases with the rising unit costs of emission abatement (i.e., ). With a shrinking green products market,the supplier decreases their investment in emission reductions, which eventually leads to a decline in the optimal emission reduction level.

A direct managerial implication from Proposition 1 and Corollary 1 is that according to different market requirements,the supplier and the retailer in the green supply chain can improve or reduce the added value of products through carbon reduction and service activities, respectively. This cooperation between supply chain members enables them to focus on their core business, thereby improving the efficiency of green production and distribution.

4.2. Dual-channel structure

The Internet and e-commerce enables consumers to search, compare, and purchase products on electronic devices.While online shopping can offer consumers greater convenience and variety, there is greater unpredictability in product quality, as the consumer cannot physically see or interact with the product before purchase. As a result, some customers intuitively evaluate products and receive pre-sale services in brick-and-mortar stores, before choosing to buy cheaper products from online stores(Chen et al., 2012).That is,retail services offered through the traditional channel may spill over to the Internet channel when the supplier encroaches on the market.Here, we investigate the impact of the service spillover effect on emission abatement by comparing the models in settings with and without retail services. When a dual-channel coexists in the market,the supplier needs to first determine the output quantity of the direct channel

, unit wholesale price

, and the carbon emission abatement level

. Afterwards, the retailer decides the order quantity of retail channel

and the retail service level

(if any). Hence, under the dual-channel structure, the profit function of the retailer and the supplier are:

4.2.1. No service spillovers

We use"

"to denote no service offerings under supplier encroachment. Substituting

into Eq (9) leads to the retailer's objective function in scenario

as follows:

The optimization of Eq (11) yields the following optimal quantity:

,Then, substituting

into Eq (10) leads to the supplier's objective function as follows:

The first-order condition of Eq(12) yields the optimal wholesale price, the optimal emission reduction level, and optimal output quantity as follows:

Substituting (

,

) into

, Eq(11) and (12),leads to the equilibrium outcomes of scenario

as shown in

Table 3.

Lemma2. In the context of no retail services offered, the supplier prefers to encroach through opening a direct channel, given that the fixed cost of establishing the direct channel is below a threshold (i.e.,

). However, when the fixed cost of establishing the direct channel is above the threshold, the supplier will distribute through the retail channel only. The equilibrium outcomes of the model are concluded in

Table 3.

Where .

Lemma 2 shows that with the increase of consumers' low-carbon awareness, the supplier is more willing to encroach through opening a direct channel (). However, when emission reduction costs are significantly high, or supplier encroachment may lead to intensive channel competition, the supplier will choose to maintain the single-channel structure(;). Moreover, if the retailer is ordering in the context of no retail services, there is no difference between the wholesale and retail purchase from online stores under a dual-channel structure(i.e., ), which also means that the supplier can get the maximum price advantage in the channel competition.In other words, the supplier can gain a competitive edge and expand her market share by providing price concessions to consumers. On this basis, we further analyze whether supplier encroachment necessarily results in a margins loss for the retail channel,as shown in Proposition 2.

Proposition 2. (i),,;(ii) if,otherwise ;(iii)and if ; while and if.

Where, and .

Proposition 2 indicates that under encroachment, the supplier's profits and the optimal emission reduction level are both better off. In addition, it seems reasonable that the supplier will set a higher wholesale price with the improvement of emission reductions. But, in fact, an increase in the wholesale price is not due to only the increasing investment in green production, but also corresponds to the aforementioned channel competition. We can observe that with the strategy of no retail services, the retailer lacks effective measures to cope with potential channel competition, which often leads to a squeeze on the retail market under supplier encroachment. As a result,the induced channel competition by supplier encroachment lowers the retailer's optimal profits, unless the low-carbon preference of consumers is sufficiently high. On the other hand, when consumers have a strong sense environmental consciousness, the retailer's marginal revenue under a dual-channel structure is higher than that under a single-channel structure(i.e.,, when). This means that in the dual-channel supply chain, the supplier can create enough of a margin from their enhanced investment in emission abatement, because consumers are willing to pay a higher price for low-carbon products. Thus, in the setting without retail services, the retailer can benefit from supplier encroachment if and only if .

Corollary 2. (i),,;

(ii),,.

Corollary 2demonstrates that the increasing low-carbon preference of consumers promotes emission reduction investments from the supplier, which is conducive to achieving a win–win outcome under supplier encroachment. However,neither the supplier nor the retailer would benefit from encroachment if the competition between both channels intensifies. In other words, the benefits brought by green production may be completely lost in channel competition, and,therefore, the supplier will prefer to adopt a single-channel strategy in this context.

As reported in Proposition 2 and Corollary 2, the retailer's free riding of emission reductions could eventually lead to a decline in his marginal revenue when the supplier adopts an aggressive channel competition strategy. But, when products are distributed through the retail channel, retailers often have service advantages with which they can win more consumer trust,through in-person interaction. Moreover, the services offered in the offline channel also helps maintain customer relationships, market products, and advertise the greenness of their products, thus eventually promoting sales also in the direct channel. On this basis, both upstream and downstream firms can complete the cross-enterprise division of emission reductions in the dual-channel supply chain. We elaborate on this in the following section on the service spillover effect.

4.2.2. Service spillover

In the scenario of the presence of retail services under supplier encroachment, we consider both the output quantity of direct channel

and the retail service level

. In the scenario

, the objective function of the retailer is:

The optimization of Eq(14) yields the optimal order quantity and the optimal service level as follows:

Then, substituting

and

into Eq(13) leads to the supplier's objective function as follows:

The first-order condition of Eq (14) yields the optimal wholesale price, the optimal emission reduction level, and the optimal output quantity as follows:

where

and

are shown in Appendix 2.

Substituting (

,

) into

,

Eq(13) and(14), respectively, we obtain the equilibrium outcomes of scenario

as shown in

Table 4.

Lemma 3. In the setting with retail services,the supplier prefers to encroach on the market if the fixed cost of the direct channel is relatively low (i.e.,

); otherwise, the supplier will still distribute through the retail channel only. The equilibrium outcomes of the model are concluded in

Table 4.

Where .

Different from , as given in Lemma 2, the selling price of the direct channel is higher than the wholesale price when retail services are available(i.e., ).More specifically, the supplier's optimal profits will be affected due to the decreased service level if the supplier squeezes the retailer's margins by raising the wholesale price. Hence, the supplier not only keeps the price advantage of the direct channel by offering a relatively low price but will also provide wholesale discounts to the retail channel under service spillovers. In this framework, supplier distribution through a dual-channel structure expands total demand by way of service spillovers. When the supplier encroaches on the market, the resultant change caused by the service spillover effect is summarized in Proposition 3.

Proposition3. The comparison of equilibrium outcomes between Scenario and Scenarioare as follows: ;; ; .

Proposition 3 directly reflects the influence of the spillover effect, in that the quantity of sales in both the retail and direct channels increases with higher total demand for green products, under the dual-channel structure.When services spillovers occur, the supplier can increase investment in emission abatement to pursue further growth in the green product market, which is also beneficial for the retailer, who will gain more profits under supplier encroachment. On this basis, it can be demonstrated from the comprehensive analyses of Proposition 1 and Proposition 3 that to cope with the changes of the channel environment and compensate for the supplier's emission abatement investment, the retailer should correspondingly maintain a certain level of retail services,regardless of whether the supplier distributes the low-carbon product through her direct channel. In addition, the retailer,as the follower in the supply chain, makes service level decisions affected by the supplier's emission abatement and channel decisions. One may expect that the optimal service levelchanges in the same direction as the optimal emission reduction decision. However, the optimal service level does not always increase with the improvement of supplier’s emission reduction levels under supplier encroachment. We explain this phenomenon further in Proposition 4.

Proposition 4. The comparison of equilibrium outcomes between Scenario and Scenario are as follows:

(i);

(ii)if,otherwise ;

(iii)and if ,whileand if.

Where .

Proposition 4 shows that on the one hand, supplier encroachment is more likely to occur when the service spillover effect is strong (). On the other hand, the increasing degree of spillover also promotes increasing investment in carbon emission abatement under the dual-channel structure.From the retailer’s perspective, consumers' attitudes towards green products determines whether she can benefit from an improvement in optimal emission reduction levels. Hence, the retailer is willing to provide a higher level of retail services only when consumers' low-carbon preference increases markedly and reaches a tipping point (i.e.,, when ); otherwise, he will be worse off from supplier encroachment, leading to a decline in the optimal service level (i.e.,and , when ). In addition, it can be concluded from that the spillover effect enhances the retailer's ability to gain more revenue from supplier encroachment when consumers have a strong awareness of environmental protection ). The reason is that service spillovers have increased the level of emission reduction With service spillover, the supplier, who gains more profits from increased demand, will increase her emission reduction level (i.e.,for all ). Accordingly, the retailer can get returns from the rising sales in brick-and-mortar stores and therefore provide improved retail services to consumers.

Corollary 3. (i),,,

;

(ii),,,;

(iii)for all , however if , andif , especially when .

Where .

From Corollary 3(i) and (ii), we know that on the one hand, consumers’ growing environmental awareness effectively promotes the cooperation of emission abatement strategies between supply chain members, which is similar to the conclusion of Corollary 2. On the other hand, as increases approaching1,the retailer's price disadvantage becomes more significant. Hence, intensive channel competition decreases order quantity and service inputs from the retailer, ultimately resulting in a lower emission reduction level. A high degree of competition between both channels may lead to the reduction in Pareto improvement;this perspective has been widely explored in many studies on the channel selection of supply chains(Yoon, 2016; Zhang et al., 2020).

Furthermore, in Corollary 3(iii), we discuss the impact of service spillovers on the emission reduction strategy and the service strategy. We offer that a higher degree of service spillover contributes to an increase in the direct channel's demand. Therefore, the supplier is more willing to enhance her emission reduction level and achieve a higher output quantity in a direct channel. However, we find that the service level decreases with a higher degree of service spillover when the spillover degree is below a certain threshold (i.e.,, when). In contrast, the service level of the retailer increases with a higher degree of service spillover when the spillover degree is above a certain threshold(i.e.,, when ).

One explanation for this result is that in the relationship between the two firms, the supplier has the price superiority and the service disadvantage in the competition between channels. When the service spillover degree is sufficiently high, the service disadvantage has no effect on the channel competition. Therefore, the supplier is more willing to reduce the wholesale price as a compensation for the retailer's service inputs. Although the retailer is limited by the price competition, he finally obtains a higher marginal revenue from a lower wholesale price(i.e.,, when ). In contrast, when the spillover degree is relatively low, the supplier's service disadvantage becomes even more pronounced and therefore she needs to ensure a distinct price advantage to attract consumers buying online. As a result, the retailer would actually get a lower marginal revenue due to the spillover effect even when a certain wholesale discount is provided by the supplier, in this situation(i.e.,,when ). Further considering the costs of retail services, it is difficult for the retailer to make up the disadvantage of the selling price, and finally he has to cut his order quantity as well as his inputs in retail services.

Another possible explanation is that with an increase in emission reduction levels, the promotion of green products in the retail market finally makes up for the loss of sales under supplier encroachment, when the spillover degree is sufficiently high (i.e., , if ). Hence, the retailer has a greater incentive to enhance the service level to further expand the demand for green products.

From the above analyses, we find that a higher degree of service spillover is beneficial for the retailer in getting greater returns under supplier encroachment, and thus gives rise to a Pareto improvement.Although this result differs from the conventional view of service spillovers,there is also a perspective that retailers’ efforts towards emission abatement would improve the performance of a green supply chain(Ji et al., 2017). This conclusion complements our research, because when retail services attract more consumers to buy green products from the direct channel also, and improves the optimal emission abatement level, the retailer's service inputs also can be regarded as a joint effort towards emission reduction.

5. Service strategy

In this section, we analyze the interactions that influence consumers' low-carbon preference and service sensitivity to the retailer's service strategy, to obtain managerial insights. According to and, the retailer can always get returns from the setting with retail services. This implies that when a dual-channel coexists in the market, the retailers have higher profits in the case of providing services.

5.1. Channel decision

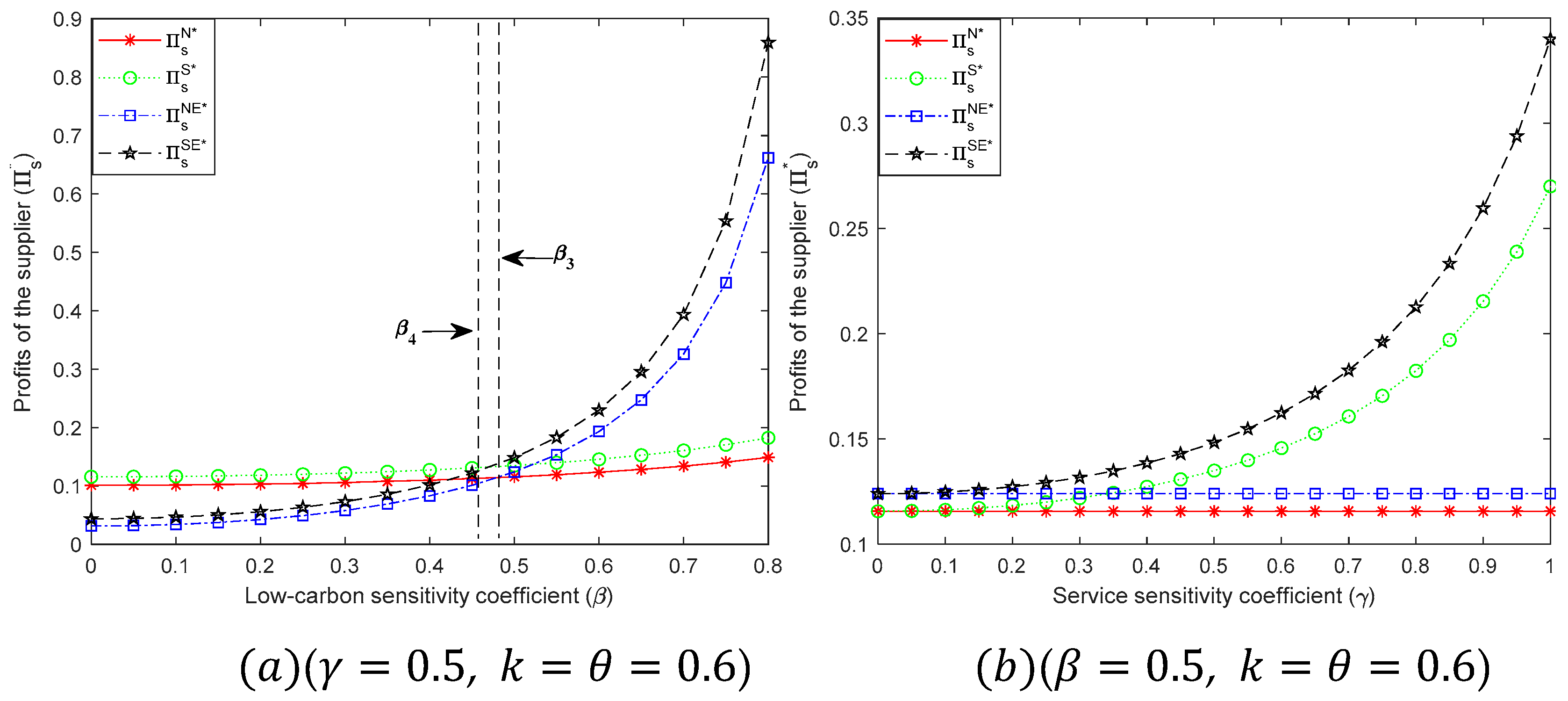

Different from the impact on retailer service strategy, both the increasing low-carbon awareness of consumers and their service sensitivity will motivate supplier encroachment, as shown in

Figure 2and

Figure 2. On the one hand, a higher consumer low-carbon sensitivity coefficient increases the margins of the green product's direct sales, thus providing suppliers with a market development opportunity. On the other hand, with the service spillover effect, the supplier also benefits from the increasing service sensitivity of consumers. In addition,

Figure 2and

Figure 2 show that the supplier would open an Internet direct sales channel as long as the cost coefficient of emission abatement is modest, or supplier encroachment would not cause an intense competition between channels. However, when the channel competition is too fierce, or the emission reduction costs are sufficiently high, supplier encroachment is unprofitable. In a market environment, the channel substitution degree can be influenced by a multiplicity of product and specific channel conditions, which is not discussed in this section. Thus, we assume that the substitution degree between the direct channel and retail channel is a constant. On this basis, we summarize the equilibrium results of service strategy and channel decisions, as shown in

Table 5.

5.2. Service strategy

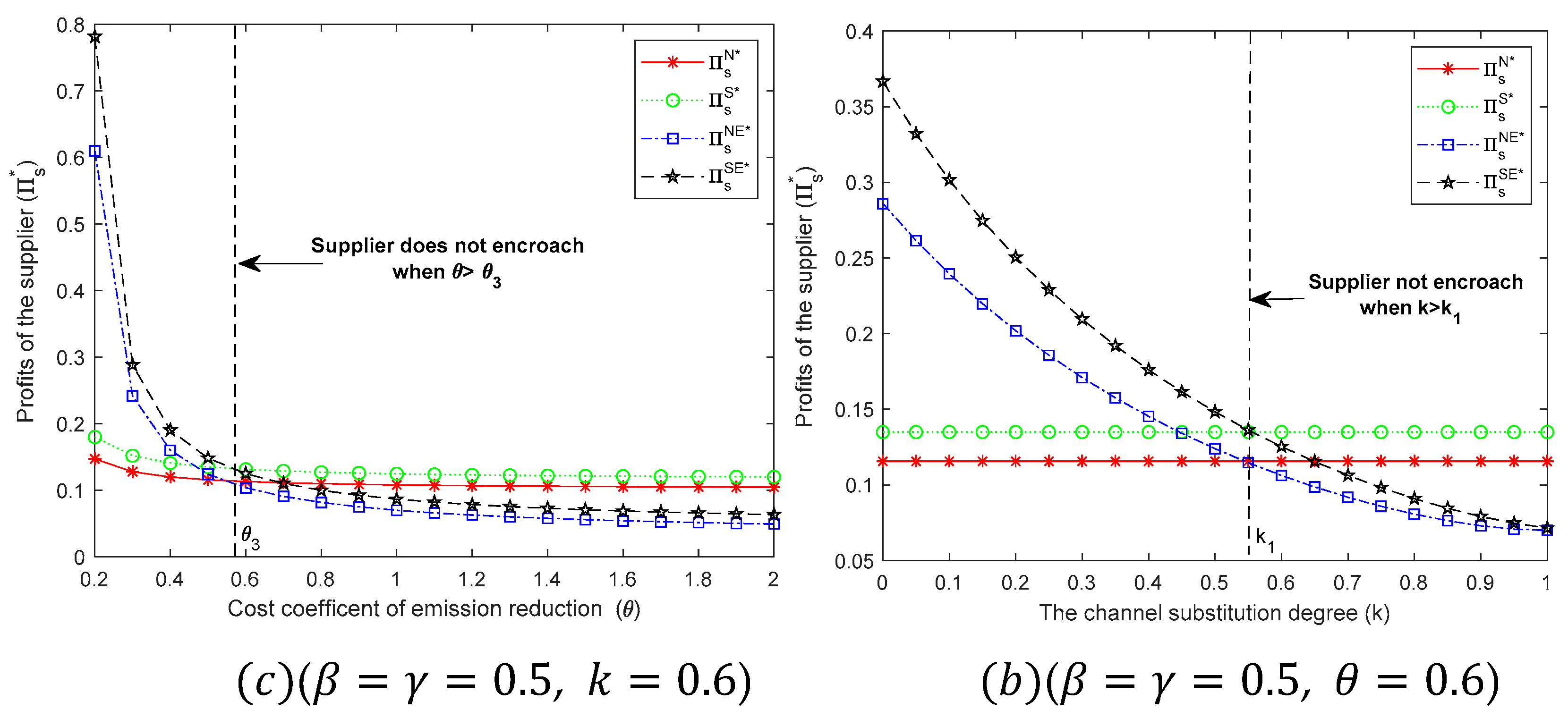

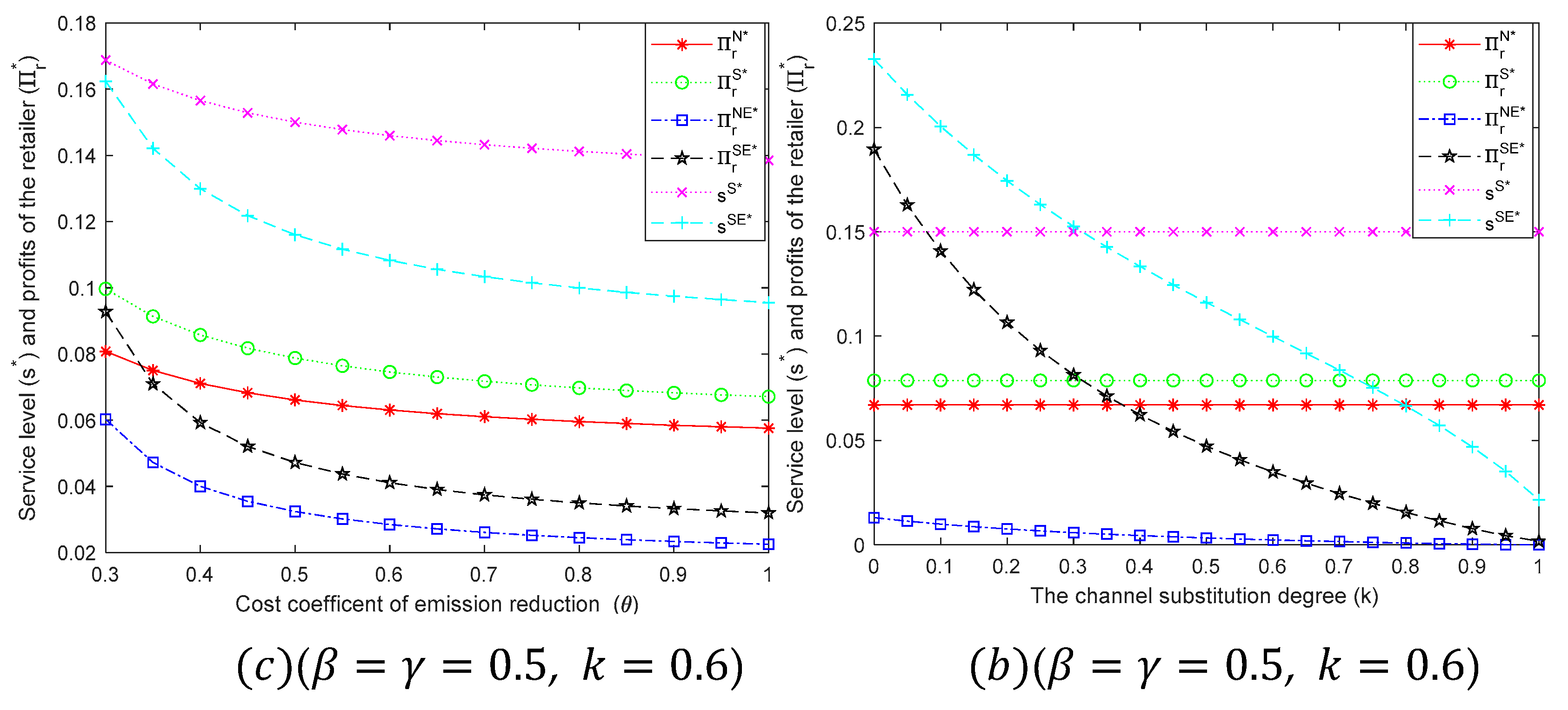

Under the dual-channel structure, consumer preference has a different impact on the retailer's optimal service level, as shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 3. When the low-carbon preference is relatively high(i.e.,

), the retailer benefits from supplier encroachment and then provides services to consumers more efficiently. However, even if consumers are more sensitive to retail services (i.e., as

increases and approaches 1), supplier encroachment still leads to a decline in the retailer's profits.In other words, due to supplier encroachment and the service spillover effect, the benefit from the growth in sales brought by the increasing consumer service sensitivity is largely shifted to the supplier. Thus, the mere proliferation of retail services, in the absence of consumers' low-carbon awareness, will not realize a Pareto improvement for the whole supply chain. On this basis, it can be concluded that compared with the service sensitivity of consumers, their low-carbon preference is the more important factor influencing the retailer's service strategy under supplier encroachment.

On the other hand, with higher emission reduction costs or product substitution, supplier encroachment will give rise to a decline in service level, as shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 3. When the cost of emission reduction is significantly high, in order to keep the price advantage of the direct channel,the supplier has to share the cost of emission reduction through increasing wholesale prices (see Proposition 2). In this scenario, the distribution of green products through both channels at the same time may put greater price pressure on the retailer channel, and also lead to bidirectional free riding between retailer's service inputs and supplier's emission reduction investments.Therefore, the cost coefficient of emission reduction and the channel substitution degree is the main factor that affects emission abatement cooperation between supply chain members, which we discuss in the following analysis of the supplier's channel decision.

6. Extended discussion

In this section, we investigate equilibrium solutions under a CCT mechanism to verify the robustness of the above analysis and its conclusions. Referring to the description of a CCT mechanism by Yi and Li (2018) and Yuan et al. (2020), the profit function of the retailer and the supplier in the dual-channel supply chain are described as follows (relevant variables are marked with '~'):

Similar to the analysis in

Section 4, if the product distributes through the retail channel only, then let

, and if retail services are unavailable, then let

. Using backward induction, we can obtain the equilibrium solutions of different scenarios, as shown in

Table 6.

Where are shown in Appendix 2.

Proposition 5. Under a CCT mechanism, when the fixed cost is below a certain threshold (i.e., ), we reach the following conclusions:

(i)and ;

(ii) and ;

(iii) and if , whileand , if.

Where.

Proposition 5 demonstrates even if we consider the influence of low-carbon policies, the supplier still prefers to invest in emission reduction under the dual-channel structure rather than a single-channel structure. Interestingly, the retailer is more likely to benefit from supplier encroachment under a CCT mechanism. This is because on the one hand, if carbon is priced, the unit carbon priceeffectively motivates the supplier to reduce carbon emissions (i.e., for all scenarios in a CCT mechanism). On the other hand, when consumers' low-carbon awareness is sufficiently high (i.e., ), the increased demand for the green product allows the retailer to earn more profits from the increase in his contribution margin per unit (similar to Proposition 2). As a result, the implementation of a CCT mechanism gives rise to a win–win outcome when the supplier encroaches on the market. The practical significance of this conclusion is that when consumers are environmentally conscious, the low carbon policy would enable a partial indirect transfer in the benefits from supplier encroachment to the retailer, thereby keeping stability in a dual-channel green supply chain system.

In fact, with the government constructing carbon policies to promote carbon emission abatement, the supplier always has more incentive to encroach on the market, especially faced with a high unit carbon price (i.e., ). One explanation might be that with the increased carbon price, those extra costs of production are undertaken by the supplier. This could push her to capture a bigger margin per unit through encroachment (). Furthermore, in contrast with a single-channel structure, the optimal emission reduction level always improves when the supplier encroaches on the market in a dual-channel structure (i.e.,and); thus, she can benefit in the form of cost reductions.

7. Conclusion

In this paper, we investigate emission reduction and supply chain channel decisions under service spillovers by introducing retail services into the green supply chain model. We consider a green supply chain system with one supplier as the Stackelberg leader that can distribute the green product through dual channels, with one retailer as the follower that can provide retail services for customers. On this basis,we fully analyze each firm's optimal decisions in different channel structures (i.e., single-channel and dual-channel) and service situations (i.e., retail services are available or not). Moreover, to verify our conclusions, we further explore equilibrium outcomes under a CCT mechanism. The main findings of this paper are briefly summarized as follows:

(1) The channel decisions of the supplier primarily depend on the costs of the direct channel. The supplier prefers to encroach on the market when the cost of opening a direct channel is relatively low; otherwise, she will employ the single-channel strategy, which only distributes through the retail channel. Furthermore, a higher degree of service spillovers motivates supplier encroachment when retail services are available.

(2) When consumers have both low-carbon preference and service sensitivity,the purpose of dual-channel distribution is not to eliminate the traditional channel, but to increase total demand by taking advantage of service spillovers and green production. Thus, if the retailer decides to provide retail services in the dual-channel supply chain, the supplier always has the incentive to reduce emissions.

(3) By comparing the optimal service strategies of the retailer in the single-channel and dual-channel supply chains, we reach three interesting conclusions. Firstly, supplier encroachment could motivate the retailer to enhance her service level and help her get more returns from providing retail services, as long as the degree of service spillovers is above a threshold. Secondly, compared with service sensitivity, consumers' low-carbon preference plays a more decisive role for the retailer's service strategies under a dual-channel structure. Thirdly, if supplier encroachment induces intensive channel competition, although the emission reduction level of the supplier is still better than that under the single-channel structure, the retailer's margins and service inputs will diminish. Therefore, the optimal levels of emission abatement and retail services are not positively correlated under supplier encroachment.

(4) Motivated by CCT regulation, the supplier is more willing to encroach on the market through the direct channel and increase her investment in the emission reduction level. Meanwhile, if consumers have low-carbon preference, the increase of unit carbon price contributes to a win-win outcome under the dual-channel structure.

This research can be extended in many directions. First, in this paper we explore the emission reduction decision in a two-echelon supply chain by the usage of a Stackelberg game theoretical approach, whereas the bargaining model is wildly used in studies on united price or differential price problems with the ‘show rooming effect.’ Thus, this provides an opportunity to investigate emission reduction decisions in different service strategies based on the bargaining model. Second, we suppose that the effects on market demand from the supplier's emission reduction level and the retailer's retail service level are linearly separable, while ignoring the non-linear situation. Third, our research assumes that information in the supply chain is symmetrical, but the supplier may not be able to fully grasp the complete service information in practice. On this basis, the decision-making and coordination of supply chain members under asymmetric information should also be studied.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by the Youth Project of Applied Basic Research Project of Shanxi Province (201801D221403), Chongqing Social Science Planning Project(2022NDYB77), Scientific and Technological Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission(KJZD-K202300305), the Science and Technology Innovation Project of University in Shanxi Province(2019L0440), the Soft Science Project of Shanxi Province (2019041002-4), and the Shanxi Intelligent Logistics Management Service Industry Innovation Science Group Project.

A.1. Proof of Lemma1. According to the Eq (6) we can get the Hessian matrix of scenario as .Similarly, the Eq (8)derived the Hessian matrix of scenario as . Hence, when, we can obtain .

A.2. Proof of Proposition 1. At first, we compare supplier’s optimal decision in different scenarios as follows:;. In the same way, we can prove that . Meanwhile, the supplier's profits under different scenarios is:, adjust the function as:,thus we can obtain that . Accordingly, we can conclude that both enterprises will be better off when retail services are available.

A.3. Proof of Corollary1. (i),,; (ii),,

,where,and ; (iii),,.

A.4. Proof of Lemma2. According to Eq(12) we can get the Hessian matrix of scenario

as:

. According to

,

and

, we can prove that

, thus

. Where

and

. In addition, based on the direct channel's output quantity

, we need to guarantee that

is non negative. According to

and

, we can obtain that

. Hence, substituting

,

and

into Eq (11) and Eq (12) the relevant results are given in

Table 3. Finally, we can obtain that

, thus there is no difference between wholesale price and direct price. Moreover, from

, because of

, the supplier will make the direct channel open when

, otherwise, the green product will still be sold only through the retail channel as shown in scenario

of

Table 3.

A.5. Proof of Proposition2. At first, we consider , thus if . Similarly, the wholesale price in different scenarios is compared as:. Let, from , we can obtain that if , otherwise,. Finally, set the marginal profit of the retailer under scenario and as: , , thus the comparison of marginal profit under two scenarios is: , which means if , then , otherwise, .

A.6. Proof of Corollary 2. (i) According to Proof of Proposition2, the proof of Corollary 2(i)is intuitive, so we omit it.

(ii),, and according to , when , we have . Thus,.

A.7. Proof of Lemma 3. According to Eq (14) we can get the Hessian matrix of scenario as , when we can obtain that . Similar to the analysis in Lemma 2, we also need to ensure that and is non negative. According to, and , we can obtain that .Meanwhile, . Hence, the dual-channel structure is feasible.

A.8. Proof of Proposition 3.According to, it is directly that, and due to the proof in Lemma 2 we have:,thus.On this basis, we can obtain that . Meanwhile, the comparison of the optimal emission reduction level between scenarioand is: , let , from and , thus we can obtain that. Employing the same process, we can easily show that holds.

A.9. Proof of Proposition 4. (i). (ii), from we can obtain thatif ; (iii) and . According to if . Hence, we can obtain that and if. The discussion of and if are evidenced the same way.

A.10. Proof of Corollary 3. The proofs of Corollary 3(i) and (ii) are the same as the proofs in Corollary 2, so we omit it. (iii);, where . Thus, if , while if .

A.11. Proof of Proposition 5., when , we can get. And according to, we can obtain that, if.

; ;,

; ;;

,

,

,

; ;,

,

;;;

;;

,

;;; ;;;

;.

References

- Adaman, F., Karalı, N., Kumbaroğlu, G., Or, İ., Özkaynak, B., Zenginobuz, Ü., 2011. What determines urban households’ willingness to pay for CO2 emission reductions in Turkey: A contingent valuation survey. Energy Policy 39(2), 689-698. [CrossRef]

- Amit Kumar, G., 2021. Framing a model for green buying behavior of Indian consumers: From the lenses of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production 295. [CrossRef]

- Arya, A., Mittendorf, B., 2013. The changing face of distribution channels: partial forward integration and strategic investments. Production and Operations Management, 1077-1088. [CrossRef]

- Benjaafar, S., Li, Y., Daskin, M., 2013. Carbon footprint and the management of supply chains: insights from simple models. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 10(1), 99-116. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, F., Song, J.-S., Zheng, X., 2009. Free riding in a multi-channel supply chain. Naval Research Logistics (NRL) 56(8), 745-765. [CrossRef]

- Cai, G., 2010. Channel Selection and Coordination in Dual-Channel Supply Chains. Journal of Retailing 86(1), 22-36. [CrossRef]

- Che, Y.-K., Hausch, D.B., 1999. Cooperative investments and the value of contracting. American Economic Review. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Zhang, H., Sun, Y., 2012. Implementing coordination contracts in a manufacturer Stackelberg dual-channel supply chain. Omega 40(5), 571-583. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, W.-y., Chhajed, D., Hess, J.D., 2003. Direct Marketing, Indirect Profits: A Strategic Analysis of Dual-Channel Supply-Chain Design. Management Science 49(1), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Du, S., Zhu, L., Liang, L., Ma, F., 2013. Emission-dependent supply chain and environment-policy-making in the ‘cap-and-trade’ system. Energy Policy 57, 61-67. [CrossRef]

- Feng, L., Govindan, K., Li, C., 2017. Strategic planning: Design and coordination for dual-recycling channel reverse supply chain considering consumer behavior. European Journal of Operational Research 260(2), 601-612. [CrossRef]

- Flavián, C., Gurrea, R., Orús, C., 2020. Combining channels to make smart purchases: The role of webrooming and showrooming. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 52. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z., Guo, X., 2019. Green product supply chain contracts considering environmental responsibilities. Omega 83, 155-166. [CrossRef]

- Hua, G., Cheng, T.C.E., Wang, S., 2011. Managing carbon footprints in inventory management. International Journal of Production Economics 132(2), 178-185. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., Guan, X., Chen, Y.-J., 2018. Retailer Information Sharing with Supplier Encroachment. Production and Operations Management 27(6), 1133-1147. [CrossRef]

- Jamali, M.-B., Rasti-Barzoki, M., 2018. A game theoretic approach for green and non-green product pricing in chain-to-chain competitive sustainable and regular dual-channel supply chains. Journal of Cleaner Production 170, 1029-1043. [CrossRef]

- Ji, J., Zhang, Z., Yang, L., 2017. Carbon emission reduction decisions in the retail-/dual-channel supply chain with consumers' preference. Journal of Cleaner Production 141, 852-867. [CrossRef]

- Jing, B., 2018. Showrooming and webrooming: information externalities between online and offline sellers. Marketing Sci. 24(1), 89-109. [CrossRef]

- Li, B., Zhu, M., Jiang, Y., Li, Z., 2016. Pricing policies of a competitive dual-channel green supply chain. Journal of Cleaner Production 112, 2029-2042. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Anderson, T.D., Cruz, J.M., 2012. Consumer environmental awareness and competition in two-stage supply chains. European Journal of Operational Research 218(3), 602-613. [CrossRef]

- Mehra, A., Kumar, S., Raju, J.S., 2018. Competitive strategies for brick-and-mortar stores to counter “showrooming”. Management Science 64(7), 3076-3090. [CrossRef]

- Peng, H., Pang, T., Cong, J., 2018. Coordination contracts for a supply chain with yield uncertainty and low-carbon preference. Journal of Cleaner Production 205, 291-302. [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, A., Jha, J.K., 2019. Pricing and coordination strategies of a dual-channel supply chain considering green quality and sales effort. Journal of Cleaner Production 218, 409-424. [CrossRef]

- Shin, J., 2007. How does free riding on customer service affect competition? Marketing Sci. 26(4), 488-503. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Zhao, D., He, L., 2016. Contracting emission reduction for supply chains considering market low-carbon preference. Journal of Cleaner Production 120, 72-84. [CrossRef]

- Xia, J., Niu, W., 2019. Adding clicks to bricks: An analysis of supplier encroachment under service spillovers. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 37(C), 100876. [CrossRef]

- Xia, L., Hao, W., Qin, J., Ji, F., Yue, X., 2018. Carbon emission reduction and promotion policies considering social preferences and consumers' low-carbon awareness in the cap-and-trade system. Journal of Cleaner Production 195, 1105-1124. [CrossRef]

- Yalabik, B., Fairchild, R.J., 2011. Customer, regulatory, and competitive pressure as drivers of environmental innovation. International Journal of Production Economics 131(2), 519-527. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Luo, J., Zhang, Q., 2018. Supplier encroachment under nonlinear pricing with imperfect substitutes: bargaining power versus revenue-sharing. European Journal of Operational Research 267(3), 1089-1101. [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y., Li, J., 2018. The effect of governmental policies of carbon taxes and energy-saving subsidies on enterprise decisions in a two-echelon supply chain. Journal of Cleaner Production 181, 675-691. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.-H., 2016. Supplier encroachment and investment spillovers. Production and Operations Management 25(11), 1839-1854. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K., Wu, G., Dong, H., He, B., Wang, D., 2020. Differential Pricing and Emission Reduction in Remanufacturing Supply Chains with Dual-Sale Channels under CCT-Mechanism. Sustainability 12(19). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-H., Yao, J., Xu, L., 2020. Emission reduction and market encroachment: Whether the manufacturer opens a direct channel or not? Journal of Cleaner Production 269. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S., Zhu, Q., 2018. A risk-averse marketing strategy and its effect on coordination activities in a remanufacturing supply chain under market fluctuation. Journal of Cleaner Production 171, 1290-1299. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.-W. Zhou, Y.-W., Guo, J., Zhou, W., 2018. Pricing/service strategies for a dual-channel supply chain with free riding and service-cost sharing. International Journal of Production Economics 196, 198-210. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).