1. Introduction

Over the years, detection and identification of damage in structures by inspection of modal quantities has proven to be a very effective strategy for structural health monitoring [

1]. Indeed, literature in this field covers a wide range of applications ranging from mechanical to aerospace and civil structures. Applications to rotating machinery, roller bearings, large-span bridges, aqueducts and monuments are present [

2,

3,

4,

5].

The accuracy of the identification procedure depends on several factors, among which are the quality of measurements, the effectiveness of the mathematical representation of the damaged structure, and the adequacy of the means used to find the descriptive parameters of damage [

6]. The former has driven researchers to search for the modal quantities which are the least sensitive to environmental effects, as it may not always be possible to perform the tests in laboratory conditions [

7]. A review of different techniques and new developments in vibration-based identification studies may be found in [

8].

Among the different modal quantities used in damage identification procedures, natural frequencies are universally recognized as easily and reliably measurable, although they have limited sensitivity to damage at an early stage. In fact, temperature and humidity can affect frequencies with changes of the same order of magnitude as those due to damage. Modal curvatures have recently attracted a great deal of interest from researchers who claimed curvatures are a very good option because of their limited sensitivity to environmental factors. Indeed, it has been shown that they can be used successfully in real engineering structures to localize damage in operational conditions [

9,

10,

11,

12]. In fact, they are local quantities which have remarkable sensitivity to damage [

9,

13], especially in the vicinity of the damage itself. However, employing curvatures for full damage identification (i.e. define location and quantification) poses a number of problems, among which is the need for a high density of sensors to assure measurement in close proximity to damage [

14,

15]. This is because the curvature variation can spread to undamaged parts, especially in the case of non-localized damage [

16,

17]. This calls for an investigation of how to better exploit their properties, while minimizing their drawbacks [

18]. Indeed, contrasting views are presented in the literature concerning the use of modal curvatures to quantify damage. On the one hand, according to some researchers modal curvatures are not a reliable quantity [

19], and it is argued that identification and quantification of damage should be treated separately, since an index of localization may not perform well in quantification and viceversa [

20]. On the other hand, theoretical evidence on the possibility of using modal curvatures for quantifying damage has been reported [

21].

Another crucial aspect of damage identification and quantification procedures is the solution of the related inverse problem. The most established approaches rely on the minimization of an objective function which measures the difference between the chosen modal quantities and the same quantities provided by a mathematical or numerical model, which are, in their turn, functions of descriptive damage parameters. In an ideal case, with the necessary and sufficient number of observations, free of any type of experimental errors and a perfect numerical model, a unique solution for the set of damage parameters is expected, as it is demonstrated in many instances [

22,

23]. However, in case of applications to real structures, not only the uniqueness of the inverse solution can be lost, but also the estimated damage parameters may be highly misleading due to different uncertainties. Therefore, application of a robust estimator (or processor) to the data obtained experimentally may improve the quality of the solution to the inverse problem, especially when in the presence of disturbance due to operating and environmental conditions, noisy data and modelling errors.

A beamformer is an operator which enables comparison of a set of data received by an array of sensors to model data, called replica vector. In ocean acoustics, the operation is named acoustic beamforming, in short beamforming, and is used to spatially filter the data set to estimate the location of the source of the signal, providing the look direction. Dating back to the end of the first half of 20th century, beamforming received much attention and has been applied to many different fields, from neurology to diagnostics in mechanics [

24]. Interested readers can refer to review papers [

25,

26], which cover the history and evolution of beamforming algorithms. In this paper, our focus is the application of beamformers, which have been successfully used in ocean acoustics, to identify damage using modal curvatures. This is because these algorithms were formulated to detect sources in space, which makes them good candidates to be applied in solving problems where local response changes have to be detected.

Despite its success in a variety of applications, beamforming has received limited attention to date in the field of structural identification, apart from the seminal work by Turek and Kuperman [

27]. In the present work, we look for possible enhancements in accuracy of damage localization and quantification in beam-type structures by applying beamforming algorithms, using modal longitudinal strains on the surface of the beam. These response quantities directly relate to curvatures and do not require the use of finite differences in calculating curvatures, which is one of the main sources of errors, especially in quantification problems. In this paper we do not address issues related to the number and location of sensors, which are distributed uniformly along the beam axis and in a fixed number of seven.

We compare the performance of beamformers against a traditional algorithm used in damage identification, based on the minimization of an objective function. The beamforming algorithms considered will be Bartlett and Minimum Variance Distorsionless Response (MVDR), and are introduced in

Section 2. We utilize a finite element method (FEM) software package to build a data set of replica vectors, and to investigate the sensitivity of modal quantities to damage. Determination of modal quantities is referred to as direct or forward problem. An investigation of the changes due to damage is addressed in

Section 3, with a comparison between numerical and experimental frequencies, mode shapes and modal curvatures. In

Section 4, by means of a numerical study we will show that the MVDR processor is superior in sensitivity to damage parameters when compared to estimators based on the simple minimization of the difference between model and measured data. In particular, this applies when dealing with critical cases, such as slight damage and damage located between two sensors. To further validate the present approach, we carried out a series of experiments on free-free beams with different damage intensities and locations, including cases of damage below a sensor and in-between two sensors.

5. Conclusions

This paper has presented an approach to damage identification based on the use of modal curvatures as observed response quantity. Three different estimators have been compared: the classical objective function, based on comparison between numerical and experimental measurements, and two beamformers, which are Bartlett and MVDR, based on projection of measurements onto the replica vector. To date, these two beamformers have been primarily applied to inverse problems concerning source identification in acoustics. Instead, we applied them to structural vibration problems in beams.

Modal curvatures are highly reputed for being locally sensitive to damage, especially at an early stage. In fact, it was shown here that the use of curvatures also has some drawbacks. These include small variations away from the damaged area, and the use of accelerometers in measurements, to enable curvature normalization and subsequent comparison between analytical and experimental results. We considered cases of free-free beams with different damage depths and locations (i.e. below a sensor and in-between two sensors), either numerical and experimental. In all the cases, the pattern of experimental curvature was quite similar to the numerical one, although the experimental variations below the cut appeared to be smaller than the numerical ones, similarly to what was observed for frequency variation, which hints at a possible overestimate of the effect of damage with the model presently in use.

All the three processors have provided a unique solution even when using one single modal curvature, both using experimental and pseudo-experimental data. All the processors showed high sensitivity to damage location but lower sensitivity to damage depth, with MVDR showing sensitivity with regard to both paramaters. This is particularly relevant for early-stage identification of damage. It was also evident that MVDR can determine damage depth and location with an accuracy comparable to methods based on frequency variation.

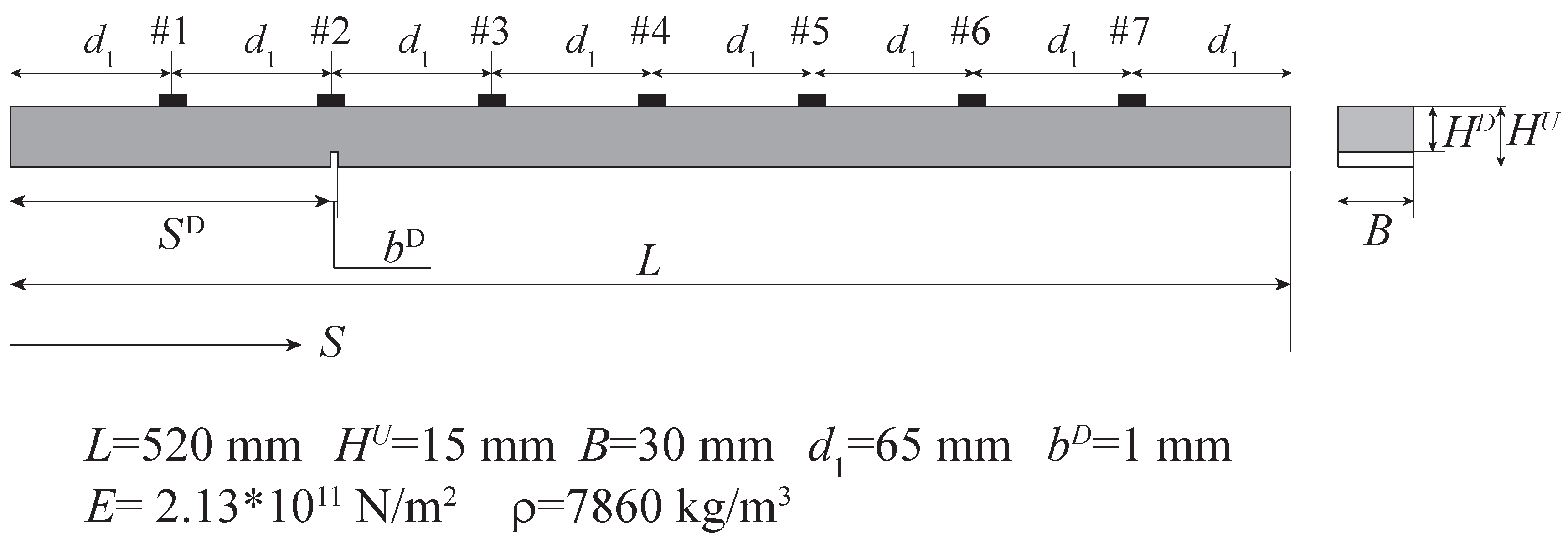

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the beam longitudinal view (left) and of its cross section (right).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the beam longitudinal view (left) and of its cross section (right).

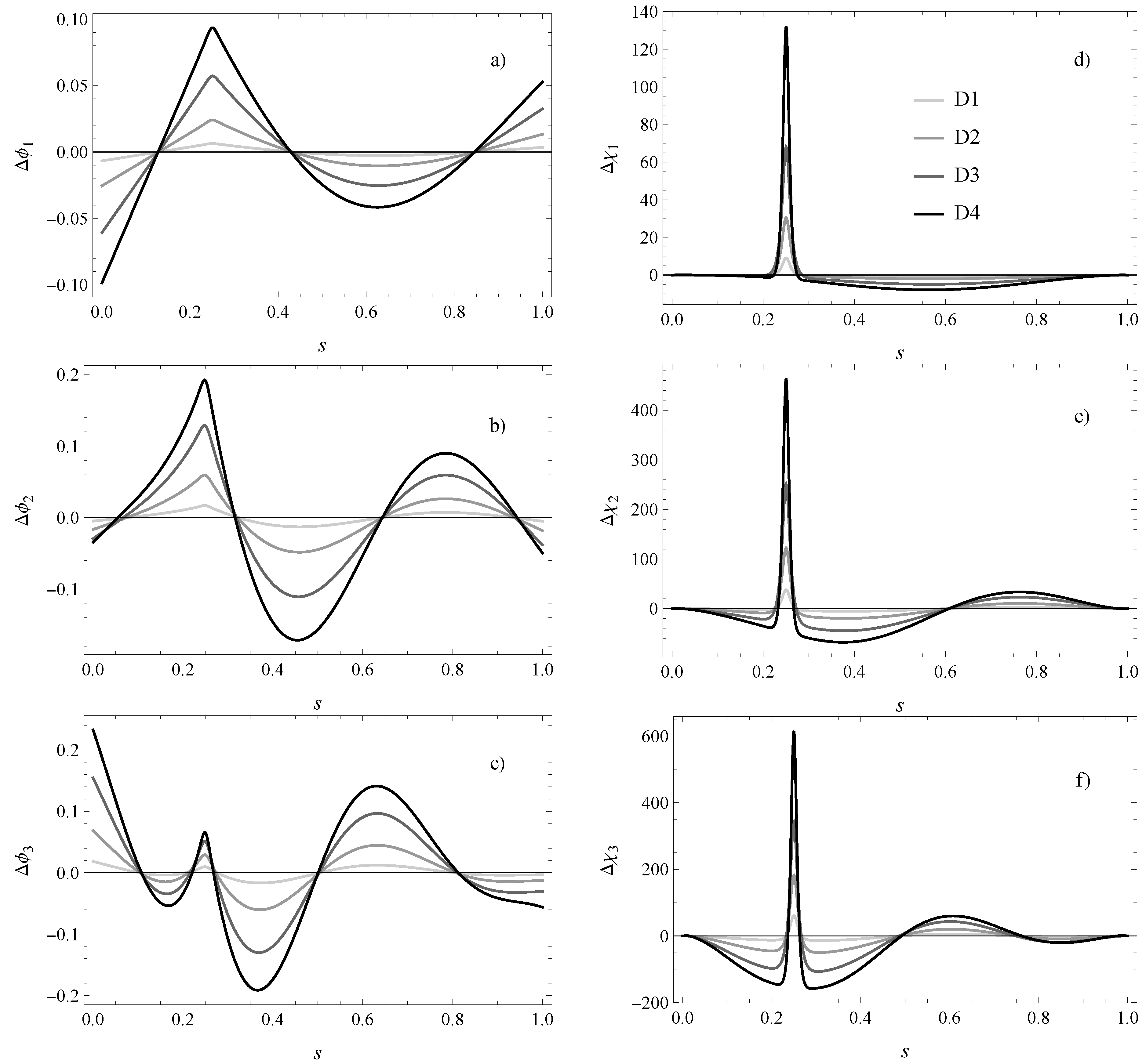

Figure 2.

Variation of modal displacements (a,b,c) and modal curvatures (d,e,f) in the four damage scenarios of location A, for the first (a,d), second (b,e) and third (c,f) mode.

Figure 2.

Variation of modal displacements (a,b,c) and modal curvatures (d,e,f) in the four damage scenarios of location A, for the first (a,d), second (b,e) and third (c,f) mode.

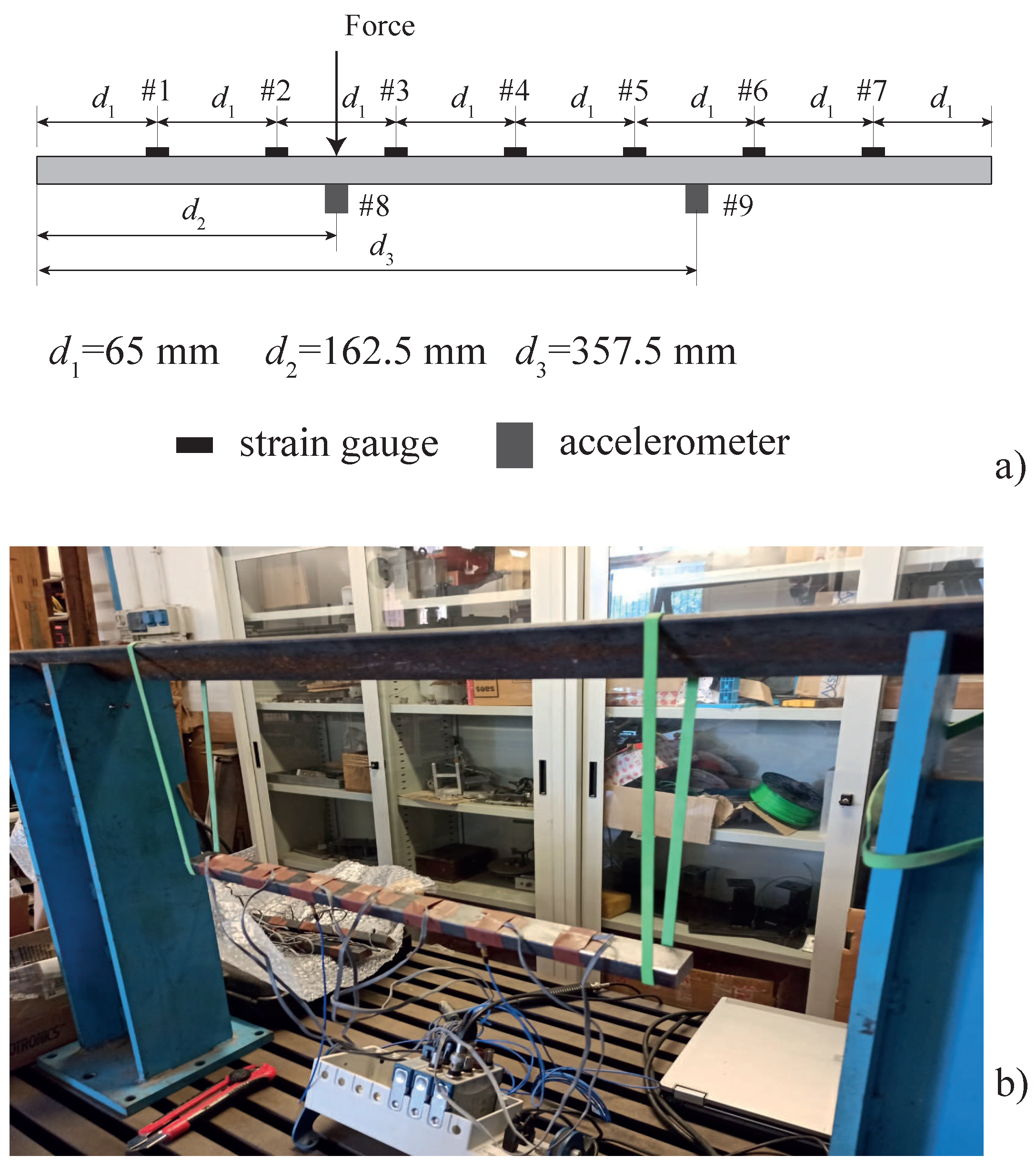

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the experimental setup (a) and image of the beam in laboratory conditions (b).

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the experimental setup (a) and image of the beam in laboratory conditions (b).

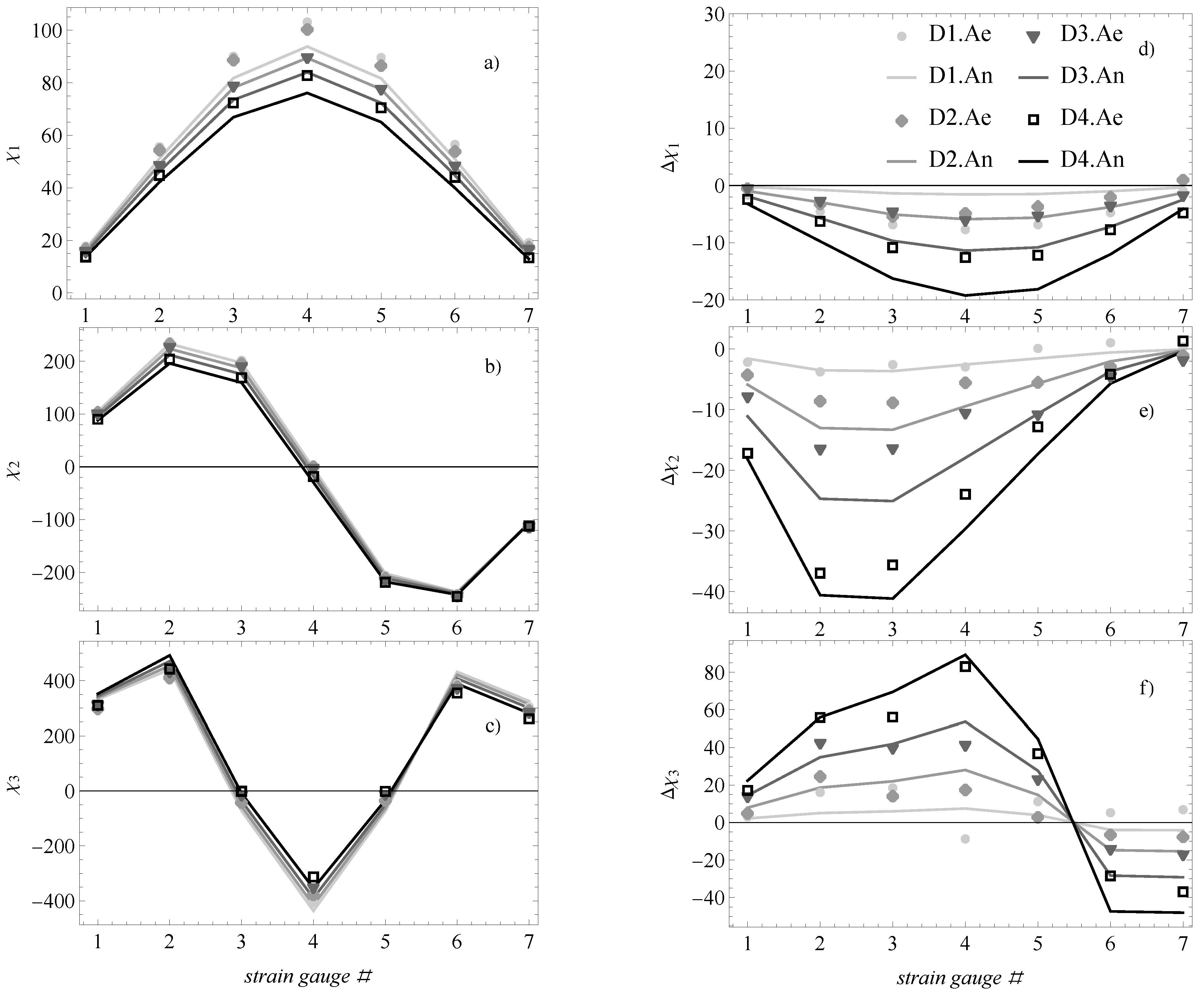

Figure 4.

Cases A: experimental (e) and numerical (n) modal curvatures (first (a), second (b) and third (c) mode) and their variations due to damage (first (d), second (e) and third (f) mode).

Figure 4.

Cases A: experimental (e) and numerical (n) modal curvatures (first (a), second (b) and third (c) mode) and their variations due to damage (first (d), second (e) and third (f) mode).

Figure 5.

Cases B: experimental (e) and numerical (n) modal curvatures (first (a), second (b) and third (c) mode) and their variations (first (d), second (e) and third (f) mode) due to damage.

Figure 5.

Cases B: experimental (e) and numerical (n) modal curvatures (first (a), second (b) and third (c) mode) and their variations (first (d), second (e) and third (f) mode) due to damage.

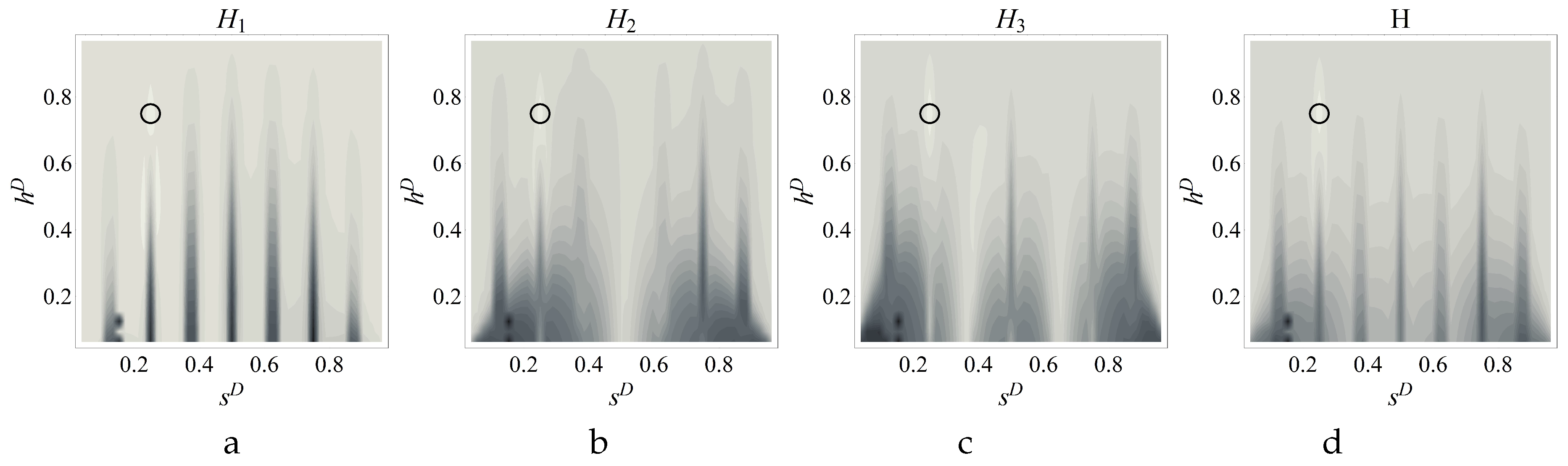

Figure 6.

Contour plots of the objective function including one (a i=1, b i=2, c i=3) and three numerical modal curvatures (i=1,2,3) (coordinates of the circle are and for D2.A).

Figure 6.

Contour plots of the objective function including one (a i=1, b i=2, c i=3) and three numerical modal curvatures (i=1,2,3) (coordinates of the circle are and for D2.A).

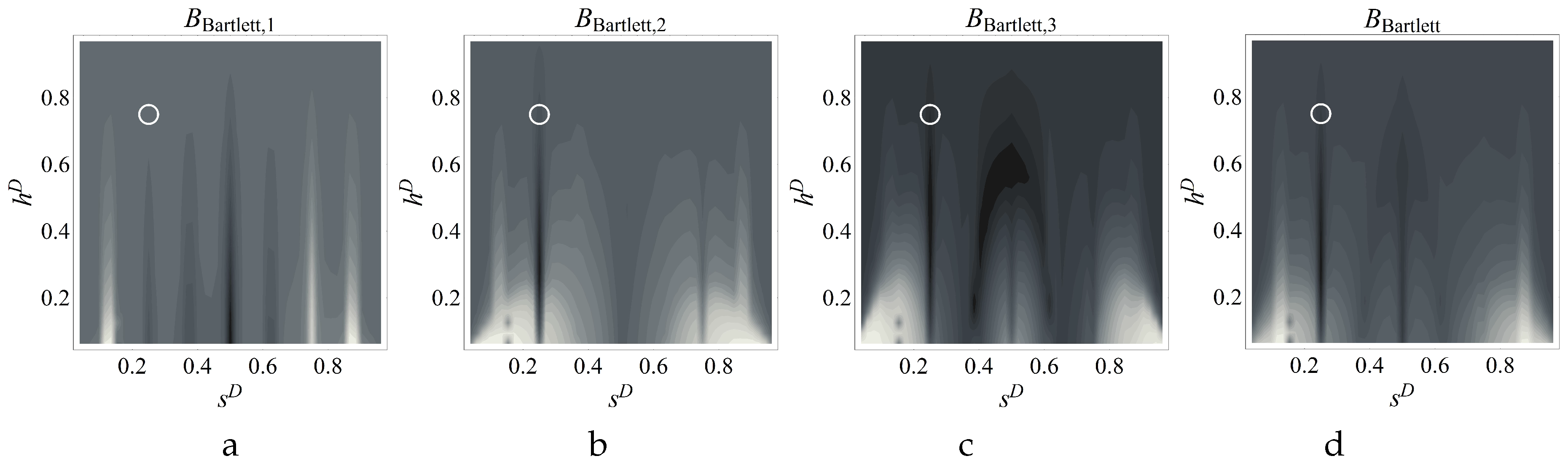

Figure 7.

Contour plots of the Bartlett beamformer including one (a i=1, b i=2, c i=3) and three numerical modal curvatures (i=1,2,3) (coordinates of the circle are and for D2.A).

Figure 7.

Contour plots of the Bartlett beamformer including one (a i=1, b i=2, c i=3) and three numerical modal curvatures (i=1,2,3) (coordinates of the circle are and for D2.A).

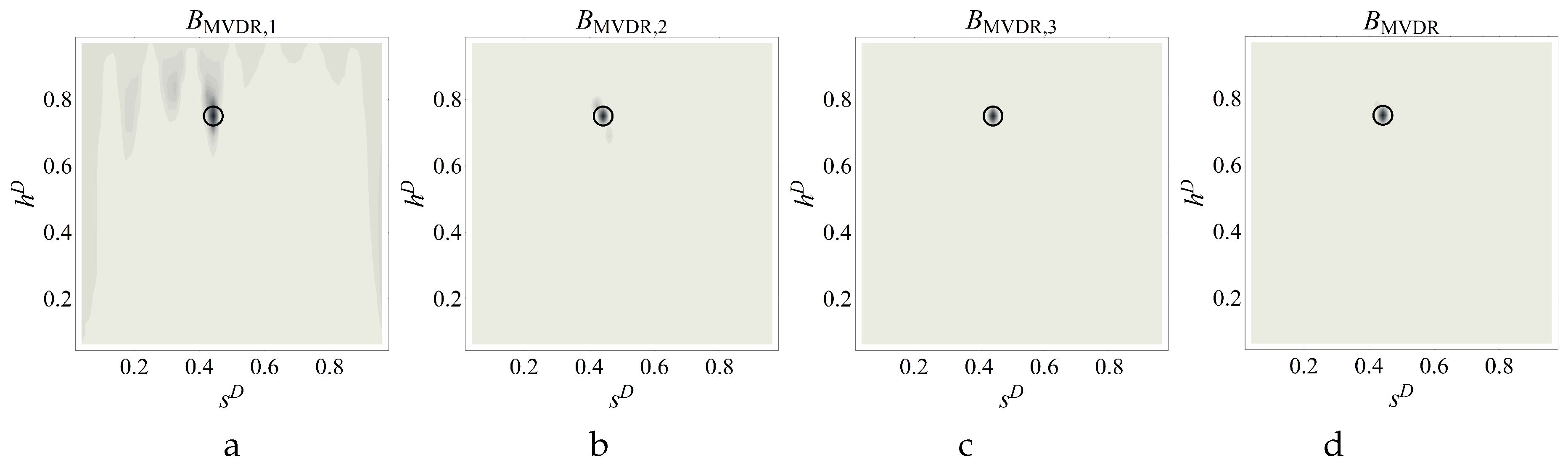

Figure 8.

Contour plots of the MVDR beamformer including one (a i=1, b i=2, c i=3) and three numerical modal curvatures (i=1,2,3) (coordinates of the circle are and for D2.A).

Figure 8.

Contour plots of the MVDR beamformer including one (a i=1, b i=2, c i=3) and three numerical modal curvatures (i=1,2,3) (coordinates of the circle are and for D2.A).

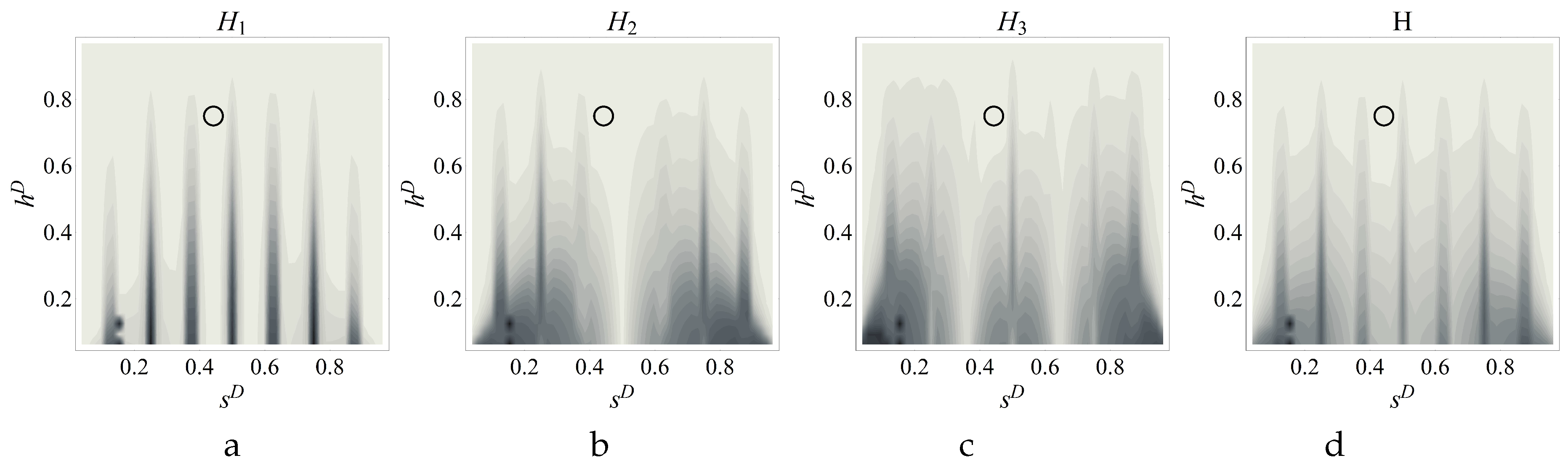

Figure 9.

Contour plots of the objective function including one (a i=1, b i=2, c i=3) and three numerical modal curvatures (i=1,2,3) (Circle: Correct damage parameters).

Figure 9.

Contour plots of the objective function including one (a i=1, b i=2, c i=3) and three numerical modal curvatures (i=1,2,3) (Circle: Correct damage parameters).

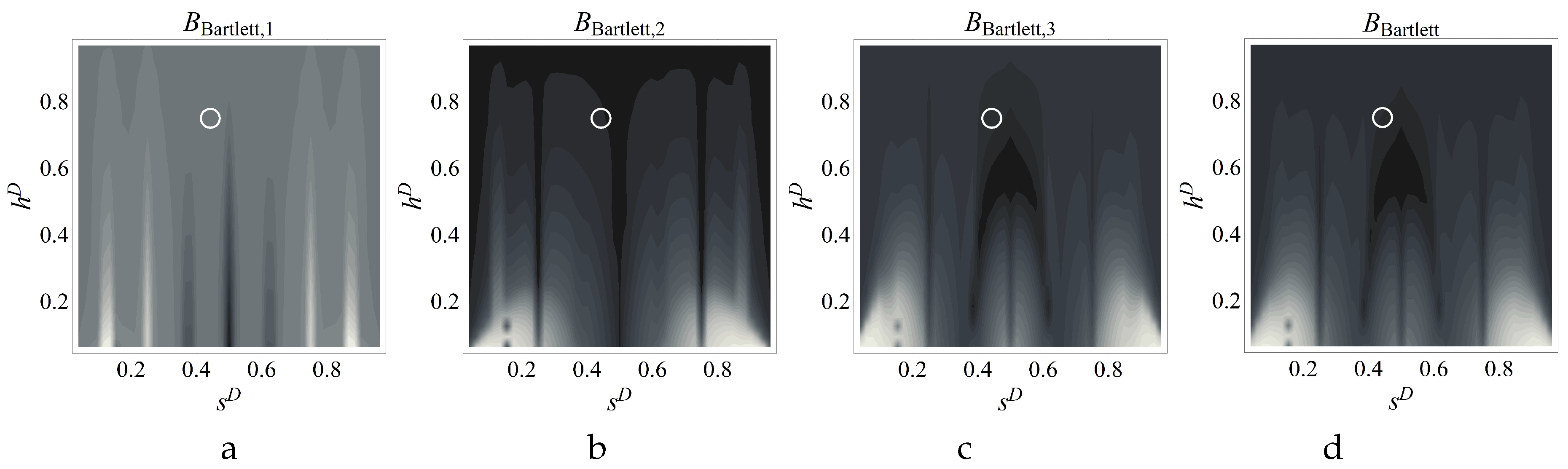

Figure 10.

Contour plots of the Bartlett beamformer including one (a i=1, b i=2, c i=3) and three numerical modal curvatures (i=1,2,3) (Circle: Correct damage parameters).

Figure 10.

Contour plots of the Bartlett beamformer including one (a i=1, b i=2, c i=3) and three numerical modal curvatures (i=1,2,3) (Circle: Correct damage parameters).

Figure 11.

Contour plots of the MVDR beamformer including one (a i=1, b i=2, c i=3) and three numerical modal curvatures (i=1,2,3) (Circle: Correct damage parameters).

Figure 11.

Contour plots of the MVDR beamformer including one (a i=1, b i=2, c i=3) and three numerical modal curvatures (i=1,2,3) (Circle: Correct damage parameters).

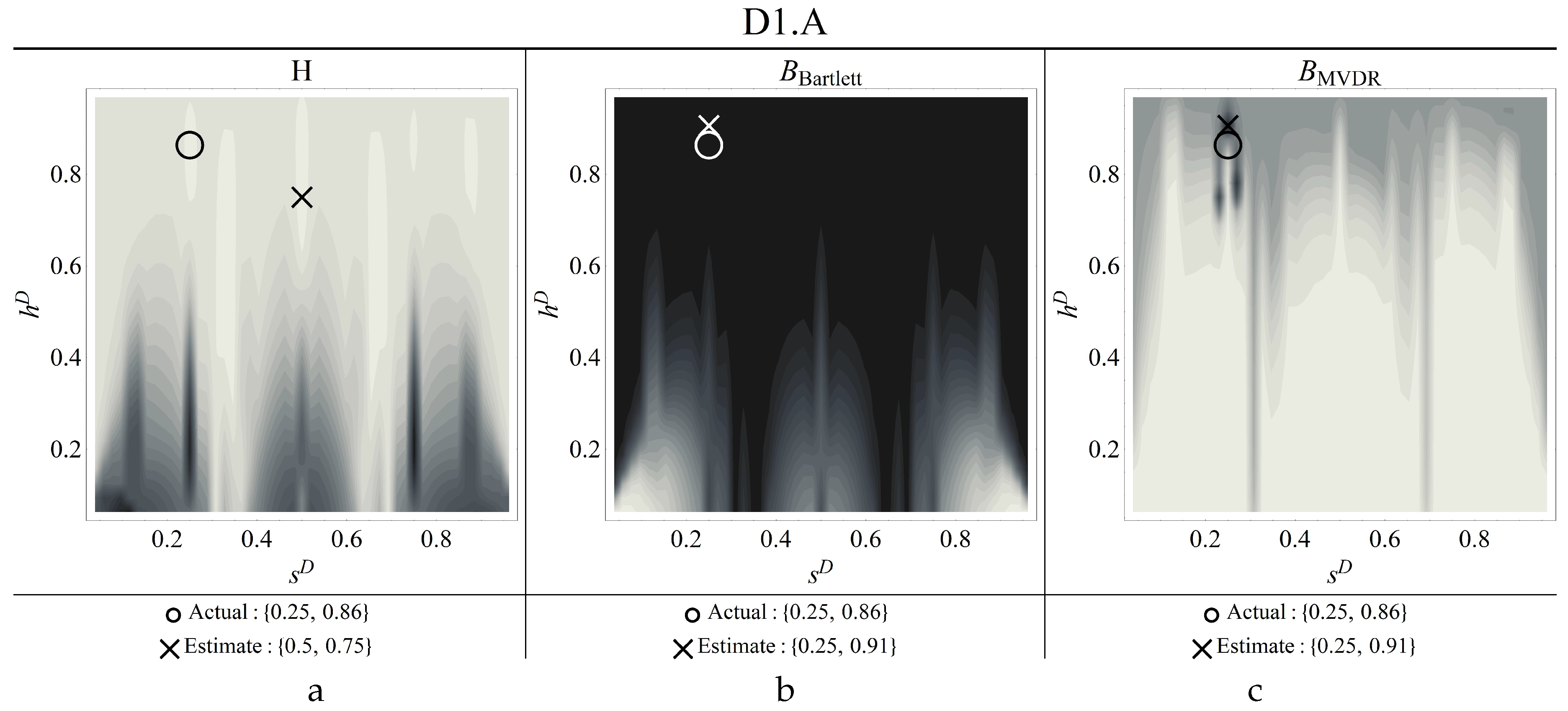

Figure 12.

Contour plots of the estimators for damage scenario D1.A (a) objective function, b) Bartlett, c) MVDR) (Circle: Correct damage parameters, Cross: identified parameters).

Figure 12.

Contour plots of the estimators for damage scenario D1.A (a) objective function, b) Bartlett, c) MVDR) (Circle: Correct damage parameters, Cross: identified parameters).

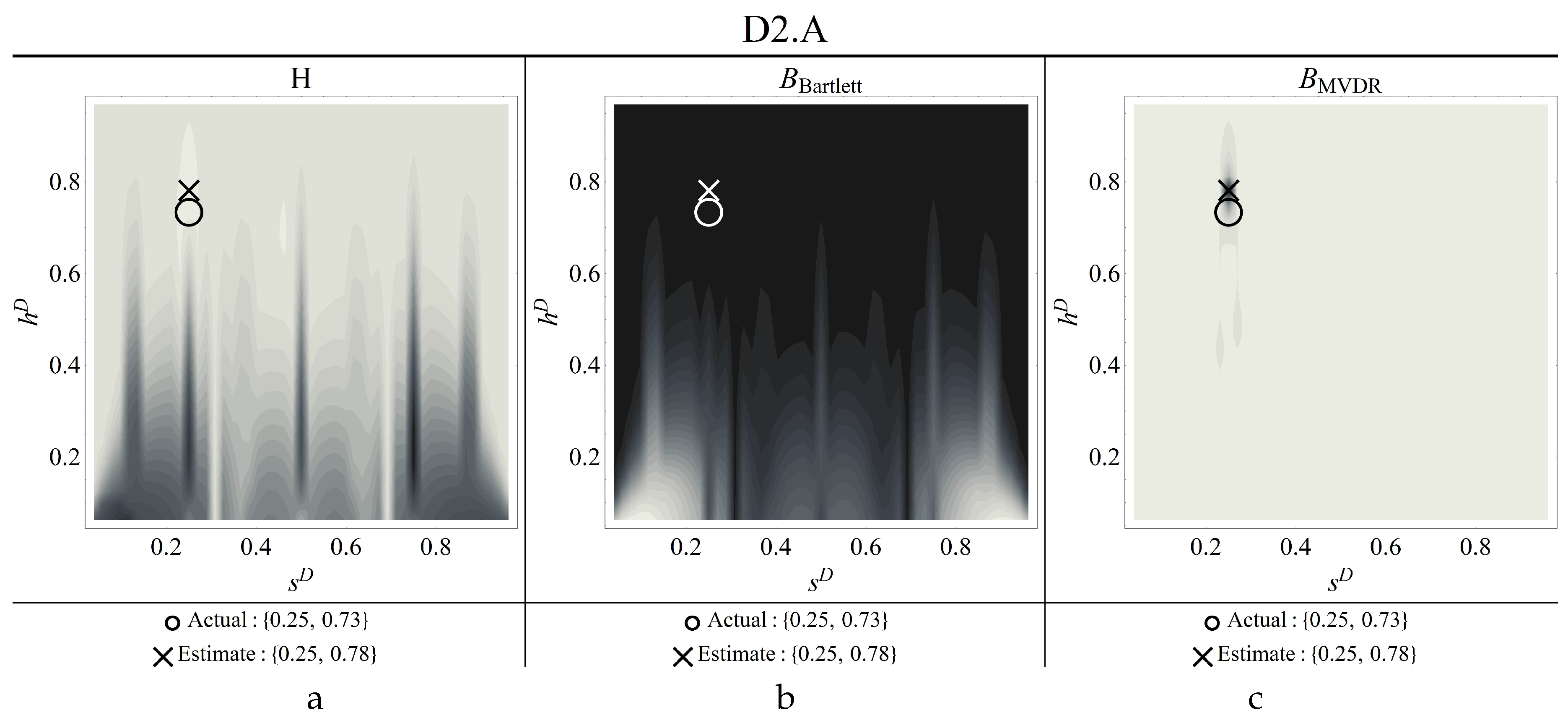

Figure 13.

Contour plots of the estimators for damage scenario D2.A (a) objective function, b) Bartlett, c) MVDR) (Circle: Correct damage parameters, Cross: identified parameters).

Figure 13.

Contour plots of the estimators for damage scenario D2.A (a) objective function, b) Bartlett, c) MVDR) (Circle: Correct damage parameters, Cross: identified parameters).

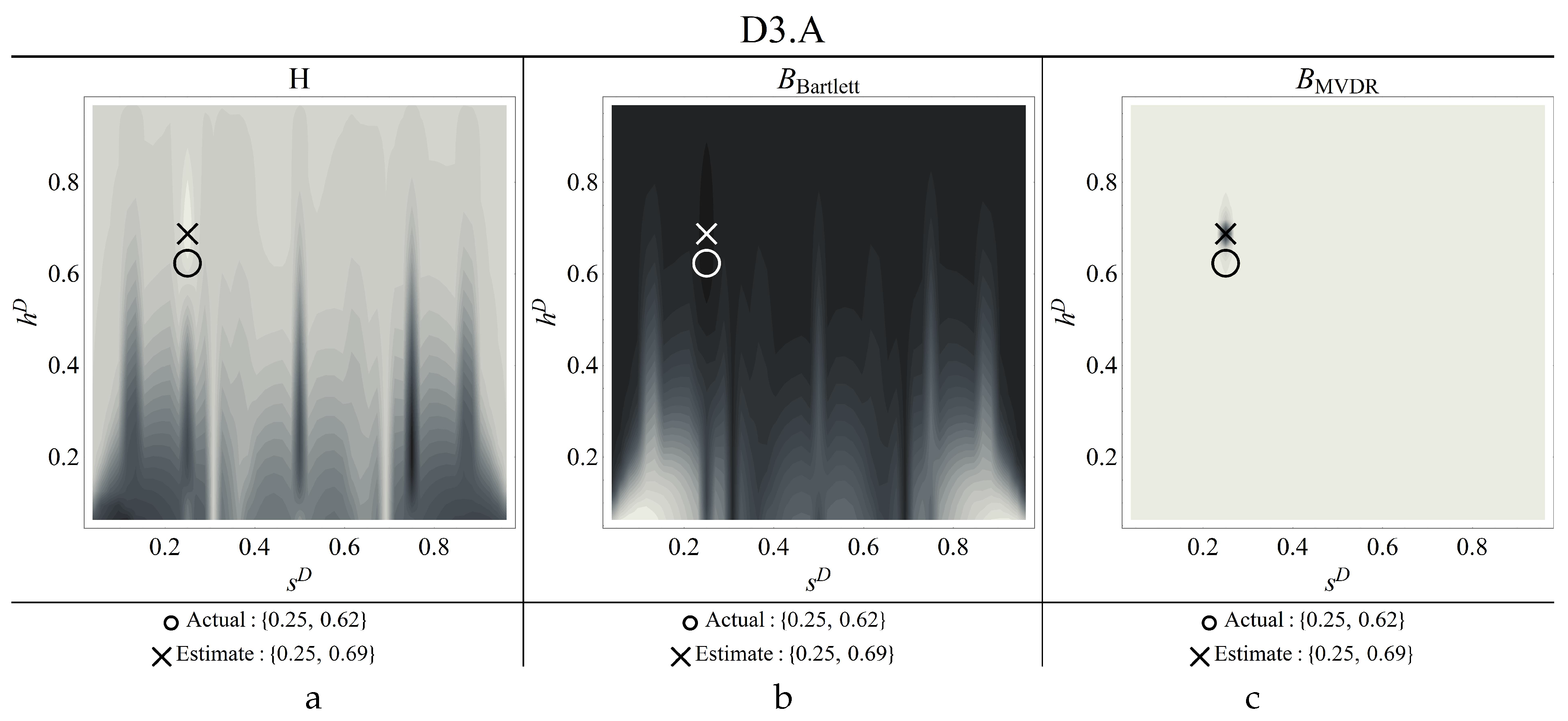

Figure 14.

Contour plots of the estimators for damage scenario D3.A (a) objective function, b) Bartlett, c) MVDR) (Circle: Correct damage parameters, Cross: identified parameters).

Figure 14.

Contour plots of the estimators for damage scenario D3.A (a) objective function, b) Bartlett, c) MVDR) (Circle: Correct damage parameters, Cross: identified parameters).

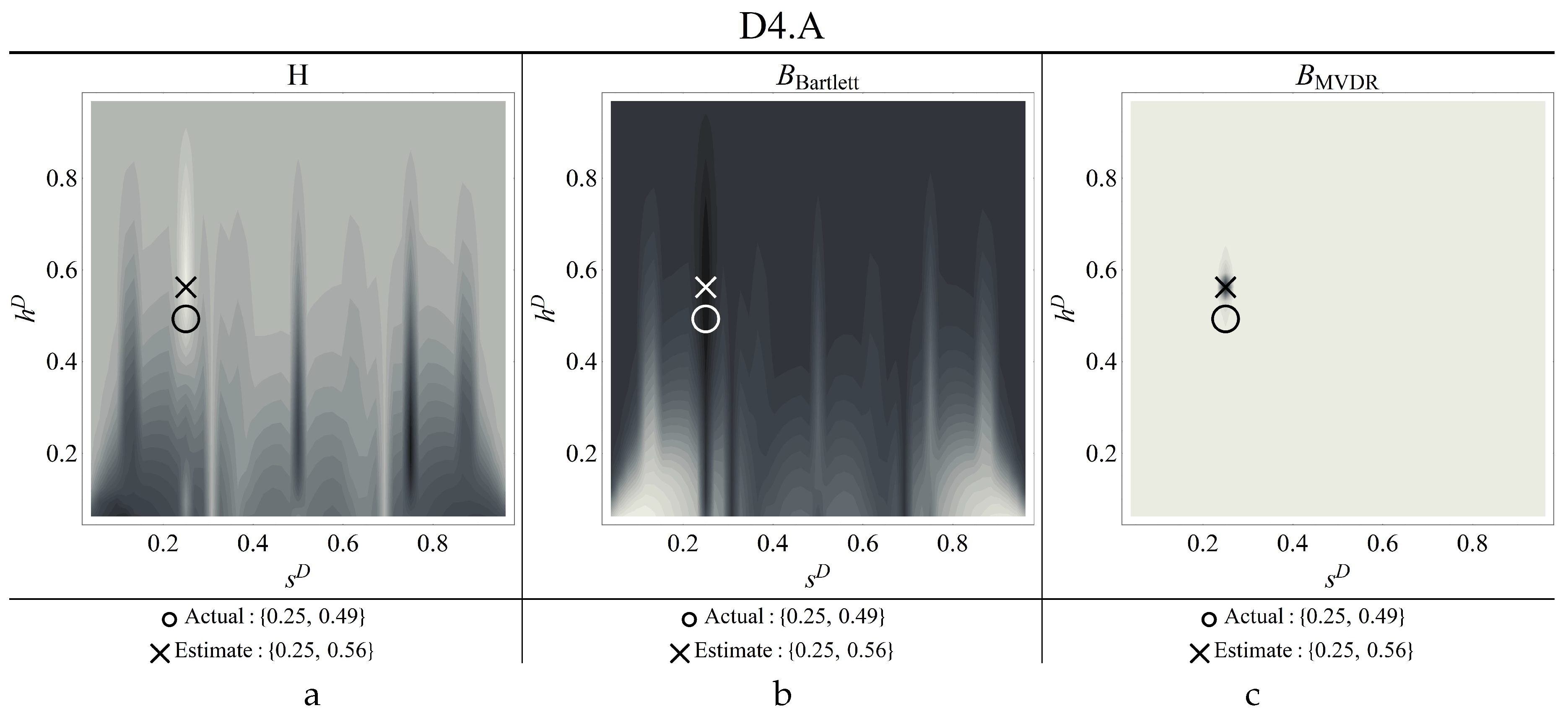

Figure 15.

Contour plots of the estimators for damage scenario D4.A (a) objective function, b) Bartlett, c) MVDR) (Circle: Correct damage parameters, Cross: identified parameters).

Figure 15.

Contour plots of the estimators for damage scenario D4.A (a) objective function, b) Bartlett, c) MVDR) (Circle: Correct damage parameters, Cross: identified parameters).

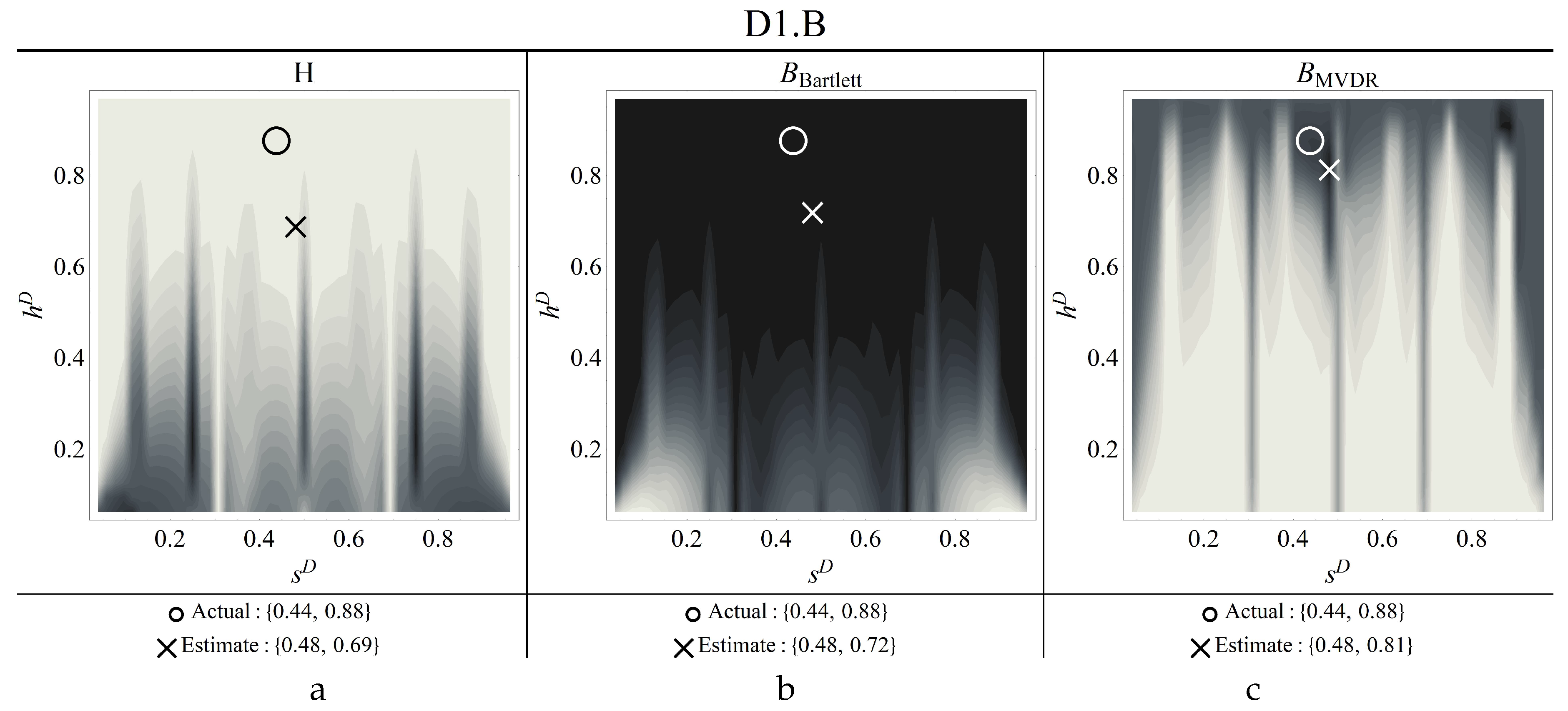

Figure 16.

Contour plots of the estimators for damage scenario D1.B (a) objective function, b) Bartlett, c) MVDR) (Thick circle: Correct damage parameters, Cross: identified parameters).

Figure 16.

Contour plots of the estimators for damage scenario D1.B (a) objective function, b) Bartlett, c) MVDR) (Thick circle: Correct damage parameters, Cross: identified parameters).

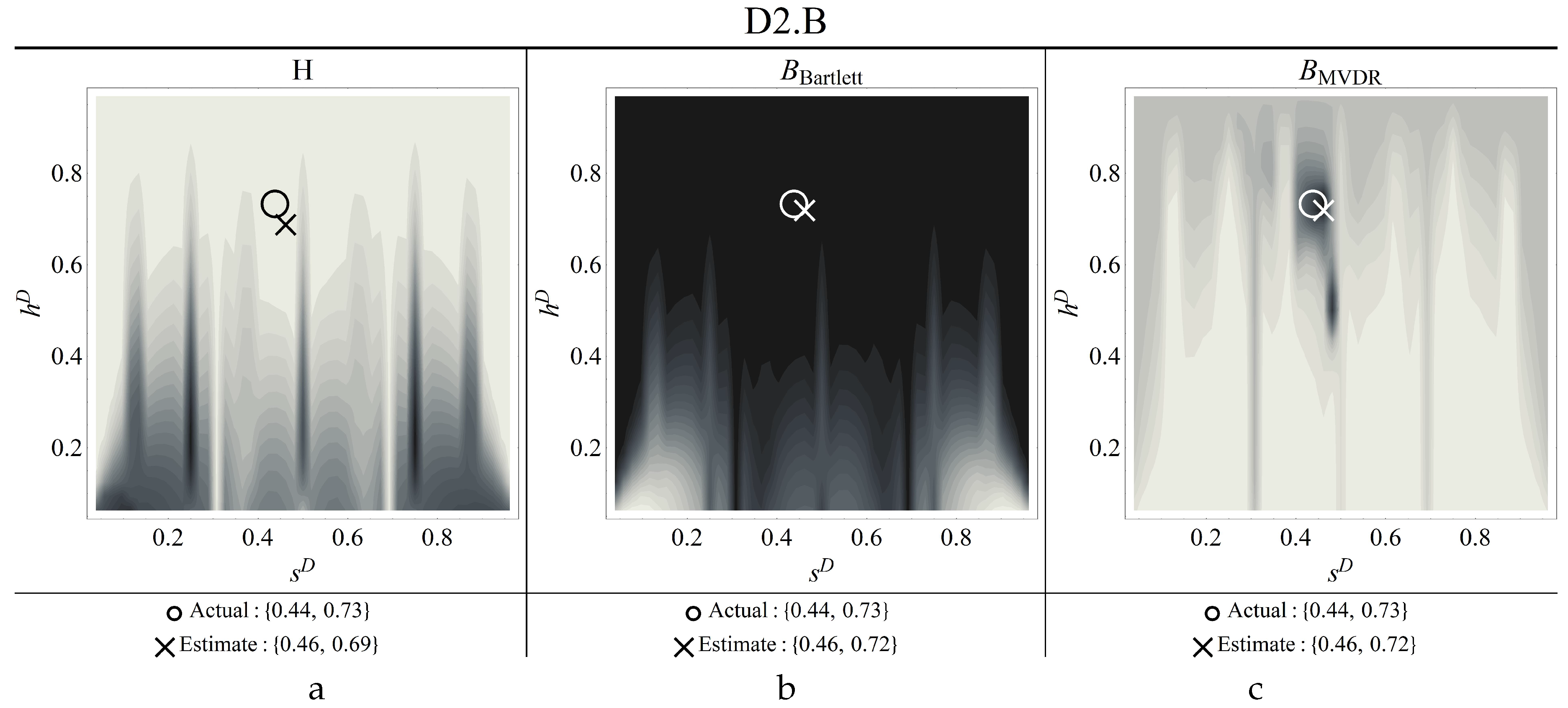

Figure 17.

Contour plots of the estimators for damage scenario D2.B (a) objective function, b) Bartlett, c) MVDR) (Thick circle: Correct damage parameters, Thin concentric circles: identified parameters).

Figure 17.

Contour plots of the estimators for damage scenario D2.B (a) objective function, b) Bartlett, c) MVDR) (Thick circle: Correct damage parameters, Thin concentric circles: identified parameters).

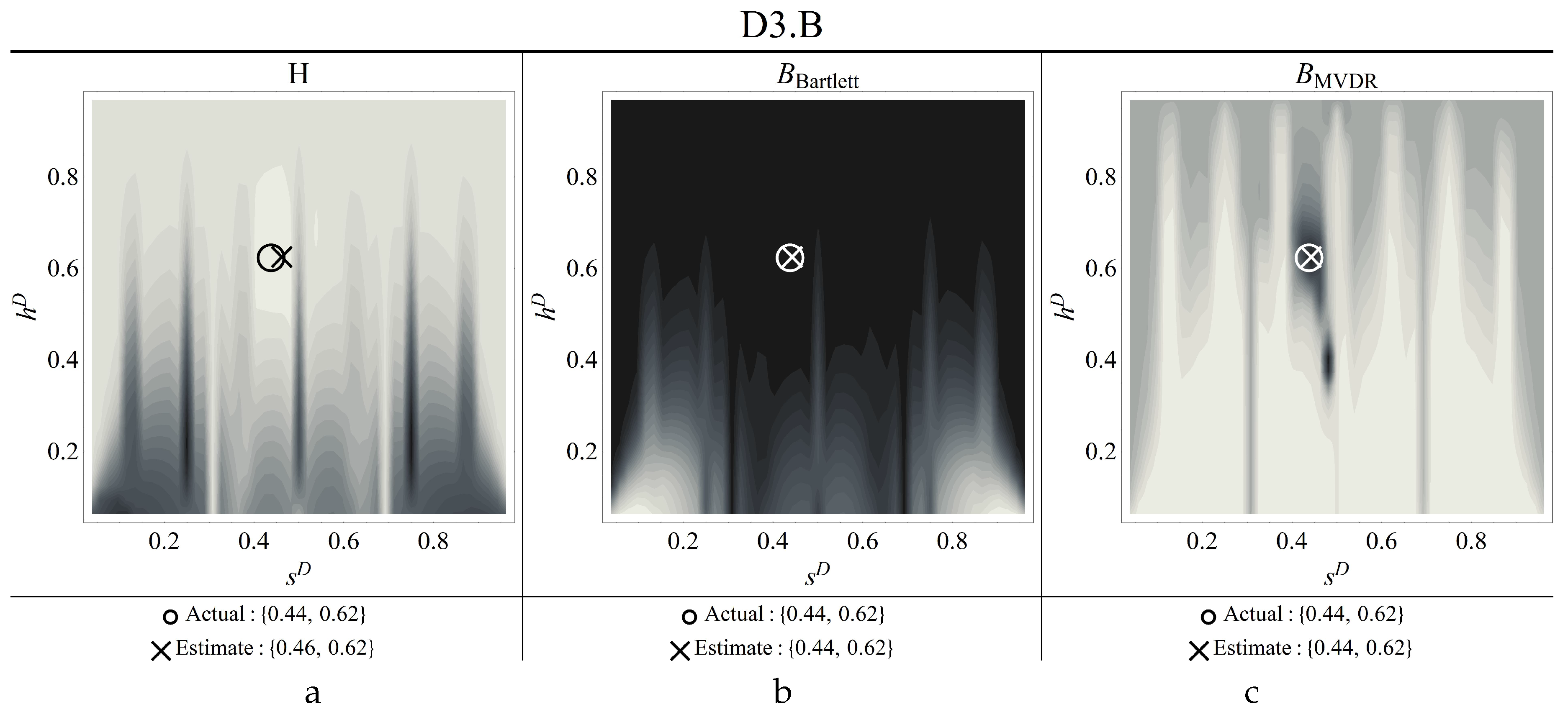

Figure 18.

Contour plots of the estimators for damage scenario D3.B (a) objective function, b) Bartlett, c) MVDR) (Thick circle: Correct damage parameters, Thin concentric circles: identified parameters).

Figure 18.

Contour plots of the estimators for damage scenario D3.B (a) objective function, b) Bartlett, c) MVDR) (Thick circle: Correct damage parameters, Thin concentric circles: identified parameters).

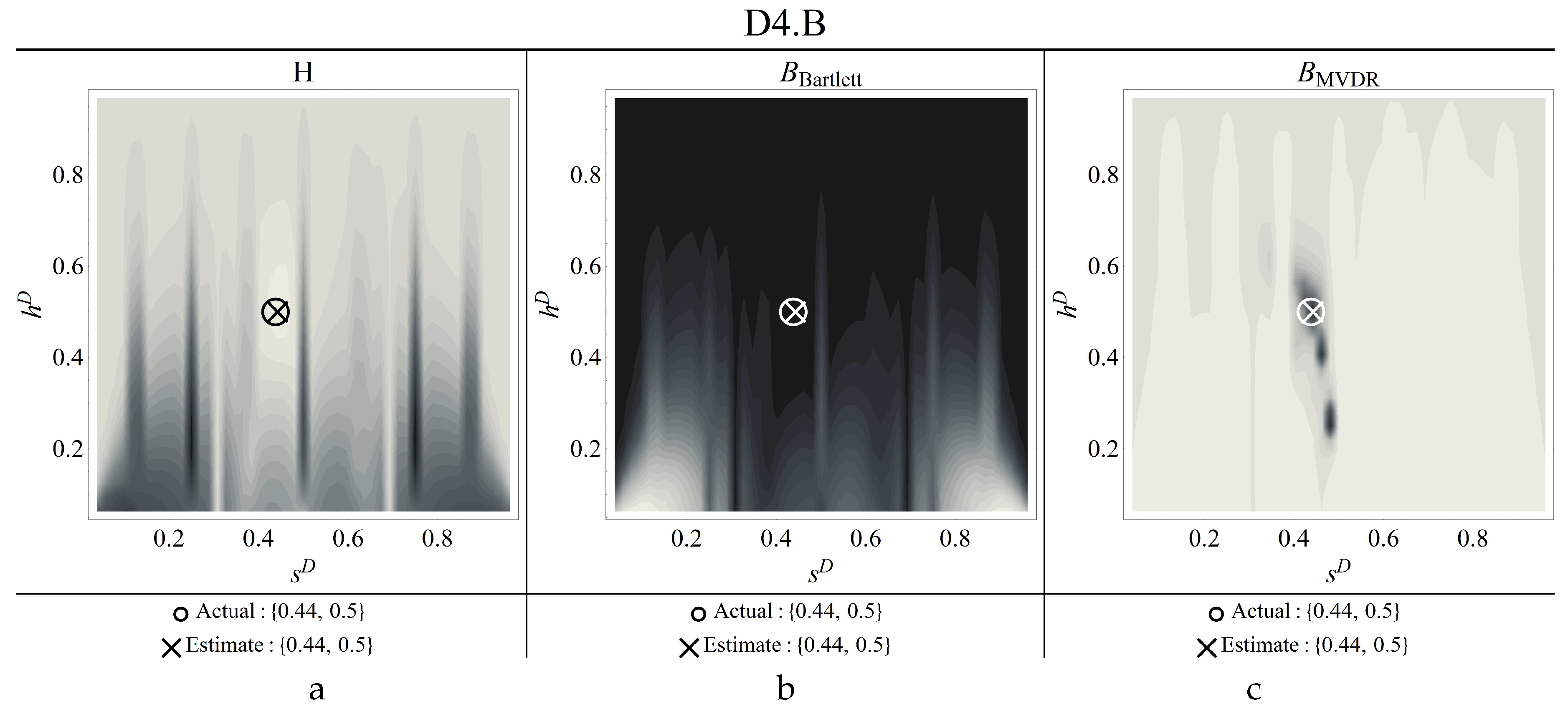

Figure 19.

Contour plots of the estimators for damage scenario D4.B (a) objective function, b) Bartlett, c) MVDR) (Circle: Correct damage parameters, Cross: identified parameters).

Figure 19.

Contour plots of the estimators for damage scenario D4.B (a) objective function, b) Bartlett, c) MVDR) (Circle: Correct damage parameters, Cross: identified parameters).

Table 1.

Labels of the damage scenarios with location (), nominal height of the damaged cross-section (), and percent stiffness reduction ().

Table 1.

Labels of the damage scenarios with location (), nominal height of the damaged cross-section (), and percent stiffness reduction ().

| |

D1.A |

D2.A |

D3.A |

D4.A |

D1.B |

D2.B |

D3.B |

D4.B |

|

0.25 |

0.25 |

0.25 |

0.25 |

0.4375 |

0.4375 |

0.4375 |

0.4375 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

33.0 |

57.8 |

75.6 |

87.5 |

33.0 |

57.8 |

75.6 |

87.5 |

Table 2.

Numerical natural frequencies () [Hz] of the first three modes () and their percent variation () due to damage.

Table 2.

Numerical natural frequencies () [Hz] of the first three modes () and their percent variation () due to damage.

| |

U |

D1.A |

D2.A |

D3.A |

D4.A |

|

|

298.96 |

298.23 |

296.12 |

292.06 |

284.09 |

|

|

|

0.25 |

0.95 |

2.31 |

4.98 |

|

|

817.12 |

811.67 |

796.67 |

769.99 |

725.52 |

|

|

|

0.67 |

2.50 |

5.77 |

11.21 |

|

|

1582.02 |

1572.86 |

1549.21 |

1512.15 |

1546.32 |

|

|

|

0.58 |

2.07 |

4.23 |

7.39 |

|

| |

U |

D1.B |

D2.B |

D3.B |

D4.B |

|

|

298.96 |

295.28 |

290.78 |

279.95 |

261.29 |

|

|

|

1.23 |

2.73 |

6.36 |

12.60 |

|

|

817.12 |

810.97 |

809.69 |

800.44 |

785.54 |

|

|

|

0.75 |

0.91 |

2.04 |

3.87 |

|

|

1582.02 |

1570.62 |

1568.89 |

1552.45 |

1525.23 |

|

|

|

0.72 |

0.83 |

1.87 |

3.59 |

|

Table 3.

Damage scenarios with measured heights of the damaged cross-section ( [mm]), and percent stiffness reduction ().

Table 3.

Damage scenarios with measured heights of the damaged cross-section ( [mm]), and percent stiffness reduction ().

| |

D1.A |

D2.A |

D3.A |

D4.A |

D1.B |

D2.B |

D3.B |

D4.B |

|

13.3 |

11.3 |

9.6 |

7.6 |

13.2 |

11.0 |

9.4 |

7.5 |

|

30.3 |

57.2 |

73.8 |

87.0 |

31.9 |

60.6 |

75.4 |

87.5 |

Table 4.

Geometrical and mechanical properties of the beams used in cases A and B.

Table 4.

Geometrical and mechanical properties of the beams used in cases A and B.

| |

H [mm] |

B [mm] |

[mm] |

E [GPa] |

[kg/m] |

| A |

15.40 |

30.12 |

130.0 |

206.5 |

7504.5 |

| B |

15.40 |

30.20 |

227.5 |

209.0 |

7656.8 |

Table 5.

Cases A: experimental () and numerical () natural frequencies [Hz] of the first three modes (), and their percent variation (,) due to damage.

Table 5.

Cases A: experimental () and numerical () natural frequencies [Hz] of the first three modes (), and their percent variation (,) due to damage.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| U |

298.8 |

|

813.52 |

|

1589.8 |

|

|

| D1.A |

298.2 |

0.21 |

810.5 |

0.38 |

1584.6 |

0.32 |

|

| D2.A |

296.8 |

0.68 |

797.8 |

1.98 |

1561.3 |

1.79 |

|

| D3.A |

294.1 |

1.58 |

784.5 |

3.57 |

1540.3 |

3.11 |

|

| D4.A |

288.7 |

3.40 |

753.2 |

7.41 |

1497.6 |

5.80 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| U |

298.8 |

|

814.5 |

|

1588.3 |

|

|

| D1.A |

298.2 |

0.17 |

810.6 |

0.47 |

1581.8 |

0.41 |

|

| D2.A |

296.5 |

0.75 |

798.1 |

2.00 |

1561.6 |

1.68 |

|

| D3.A |

293.7 |

1.69 |

779.1 |

4.34 |

1533.5 |

3.45 |

|

| D4.A |

288.0 |

3.61 |

744.3 |

8.62 |

1489.4 |

6.23 |

|

Table 6.

Cases B: experimental () and numerical () natural frequencies [Hz] of the first three modes (), and their percent variation (,) due to damage.

Table 6.

Cases B: experimental () and numerical () natural frequencies [Hz] of the first three modes (), and their percent variation (,) due to damage.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| U |

297.7 |

|

809.8 |

|

1584.5 |

|

|

| D1.B |

295.5 |

0.73 |

808.3 |

0.19 |

1579.0 |

0.35 |

|

| D2.B |

287.8 |

3.33 |

803.5 |

0.78 |

1564.1 |

1.29 |

|

| D3.B |

282.1 |

5.23 |

799.0 |

1.34 |

1549.6 |

2.20 |

|

| D4.B |

267.6 |

10.12 |

790.0 |

2.45 |

1521.5 |

3.97 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| U |

297.5 |

|

811.2 |

|

1582.6 |

|

|

| D1.B |

295.1 |

0.83 |

808.9 |

0.28 |

1578.7 |

0.26 |

|

| D2.B |

288.1 |

3.16 |

802.6 |

1.06 |

1567.5 |

0.96 |

|

| D3.B |

279.1 |

6.19 |

794.9 |

2.01 |

1553.5 |

1.85 |

|

| D4.B |

265.7 |

10.68 |

784.3 |

3.32 |

1534.2 |

3.06 |

|

Table 7.

% errors on the identified damage parameters for damage cases A.

Table 7.

% errors on the identified damage parameters for damage cases A.

| |

D1.A |

D2.A |

D3.A |

D4.A |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| H |

100 |

-12.7 |

0.0 |

6.9 |

0.0 |

11.3 |

0.0 |

14.3 |

| Bartlett |

0.0 |

5.8 |

0.0 |

6.9 |

0.0 |

11.3 |

0.0 |

14.3 |

| MVDR |

0.0 |

5.8 |

0.0 |

6.9 |

0.0 |

11.3 |

0.0 |

14.3 |

Table 8.

% errors on the identified damage parameters for damage cases B.

Table 8.

% errors on the identified damage parameters for damage cases B.

| |

D1.B |

D2.B |

D3.B |

D4.B |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| H |

9.1 |

-21.6 |

4.6 |

-5.5 |

4.6 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Bartlett |

9.1 |

-18.2 |

4.6 |

-1.4 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| MVDR |

9.1 |

-8.0 |

4.6 |

-1.4 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |