Submitted:

29 August 2023

Posted:

31 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

| Dataset | Q11 | Q21 |

|---|---|---|

| Yellowfin tuna | 0 | 0.435 |

| Albacore tuna | 0 | 0.833 |

| Bigeye tuna | 5 | 10.4 |

2.2. Data preprocess

2.3. Proposed method

3. Experiments

3.1. Preparation for evaluation

3.2. Environments

3.3. Results

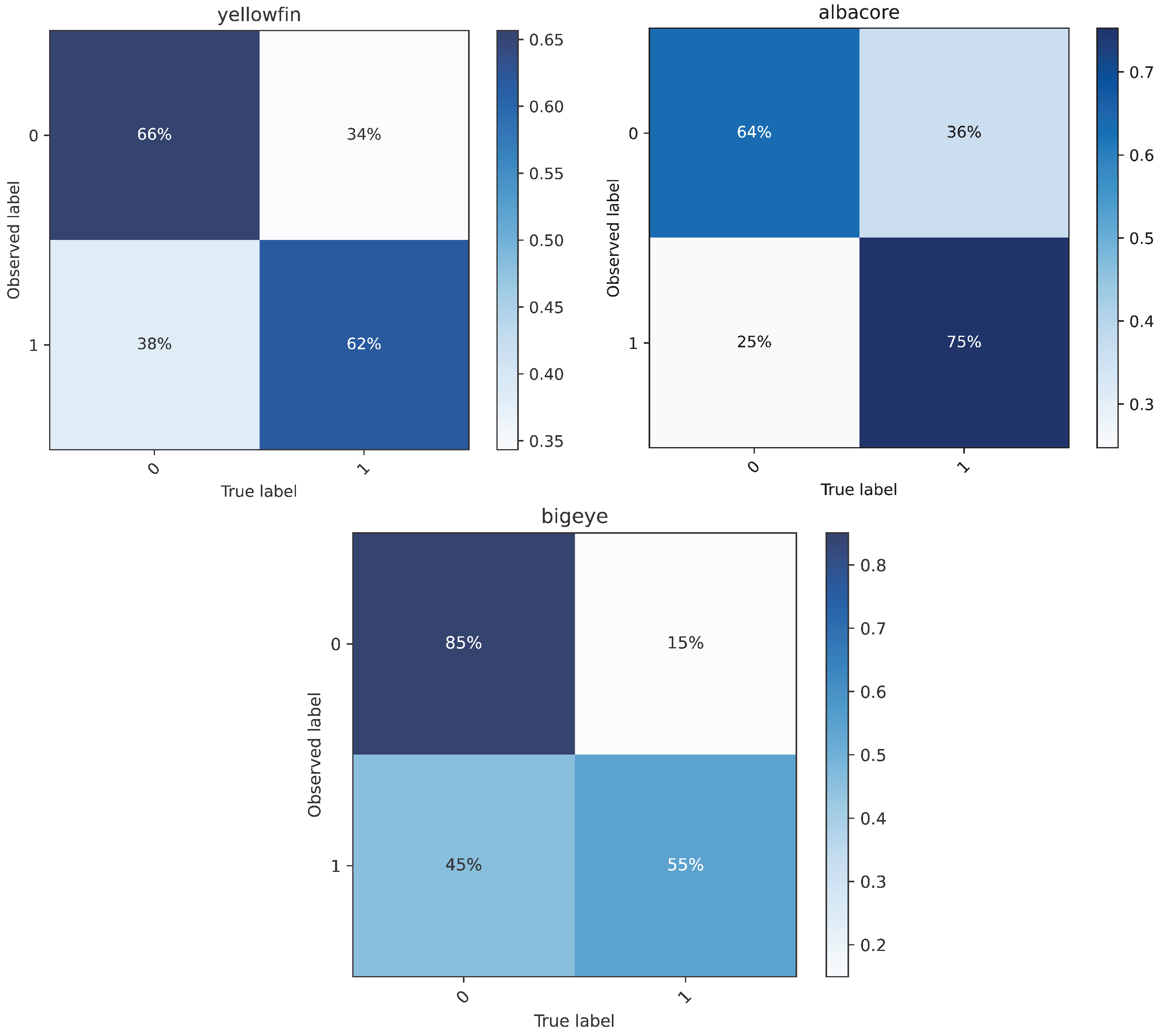

3.3.1. Anomalous samples analysis

| Dataset1 | Total number of zeros | Total number of noisy samples | Noisy samples in Zeros | Zeros in Noisy samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yellowfin tuna | 5712 | 2812 | 53.77% | 26.47% |

| Albacore tuna | 4652 | 2206 | 43.20% | 20.49% |

| Bigeye tuna | 569 | 1608 | 6.15% | 2.17% |

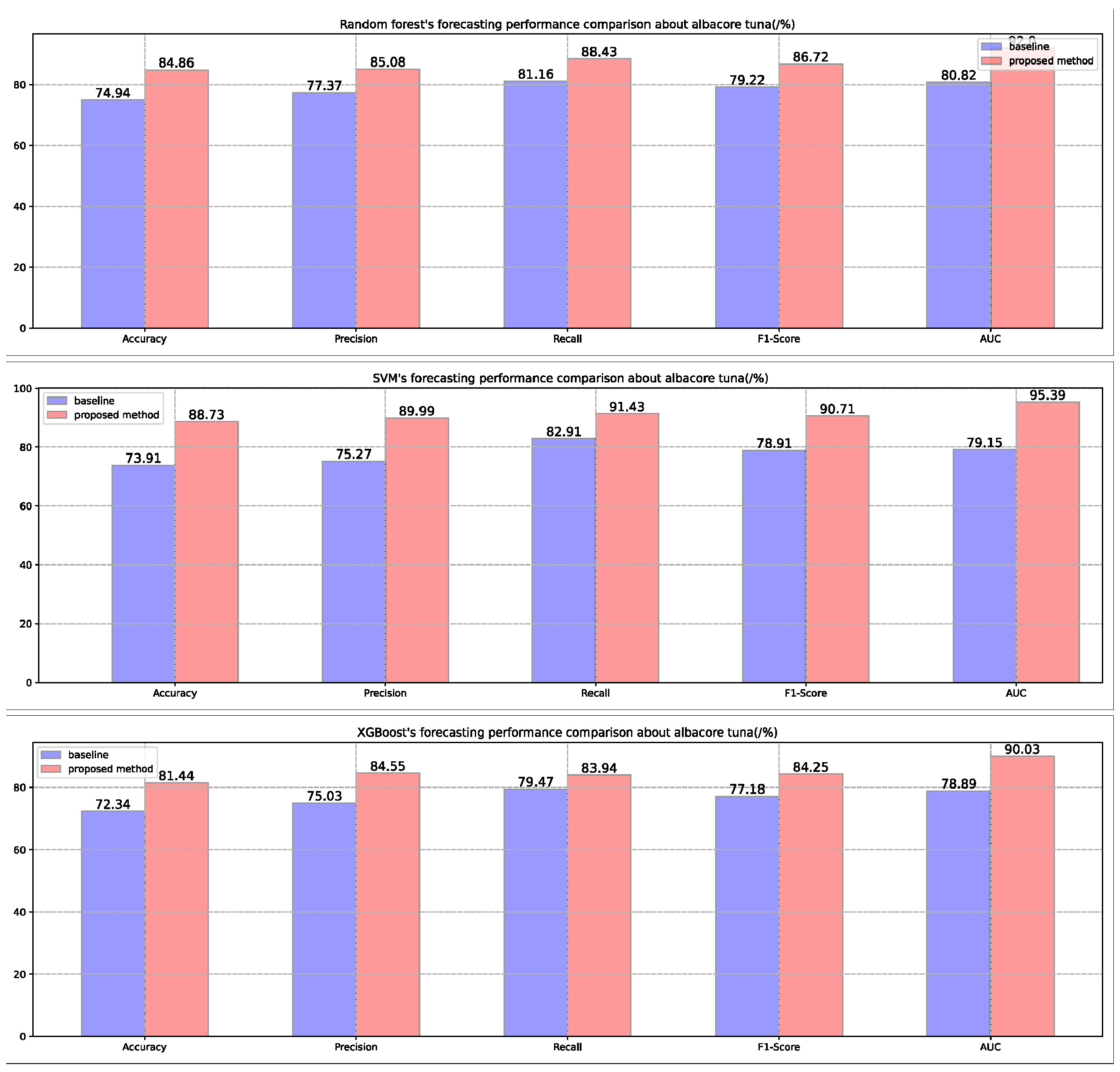

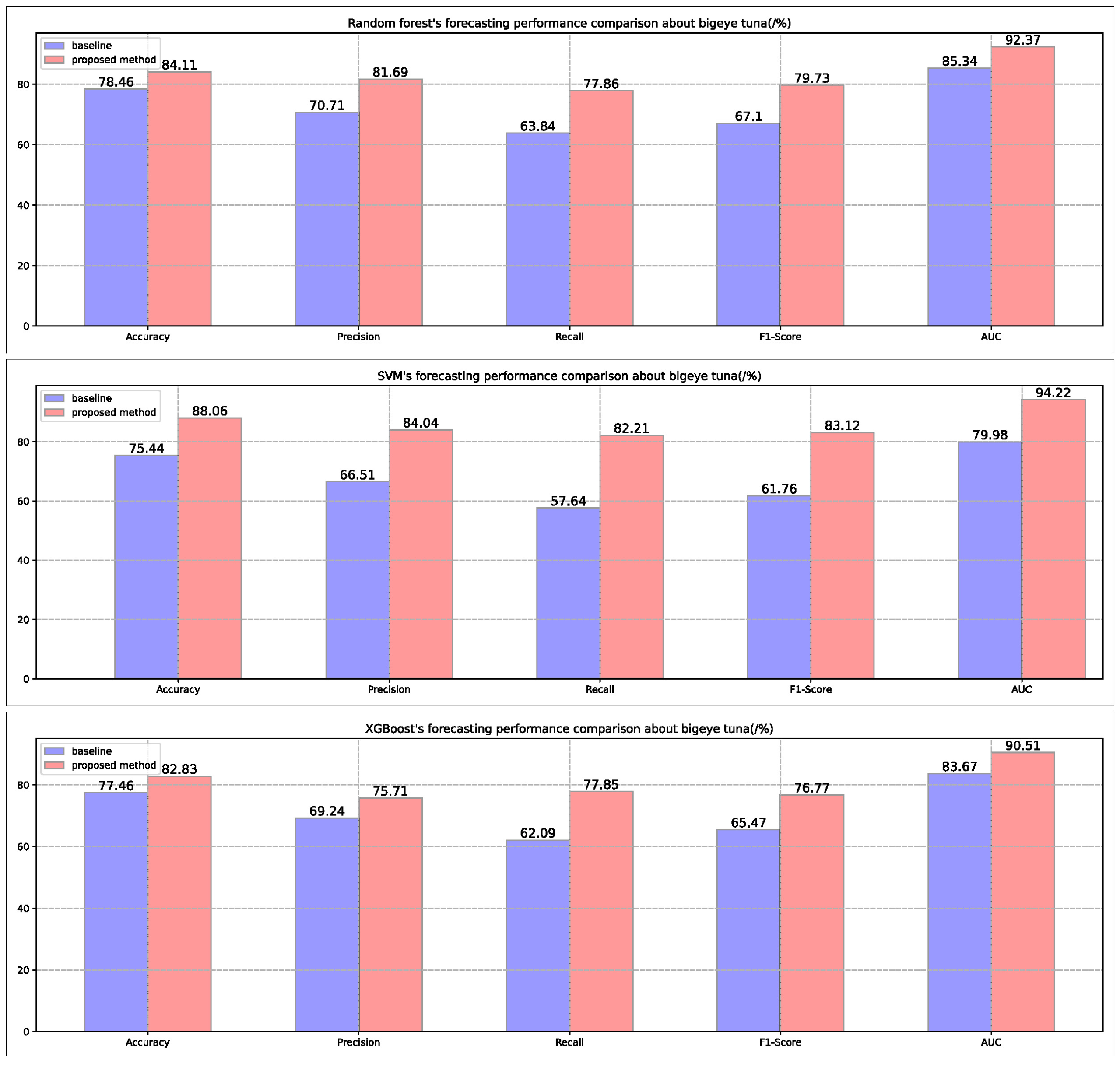

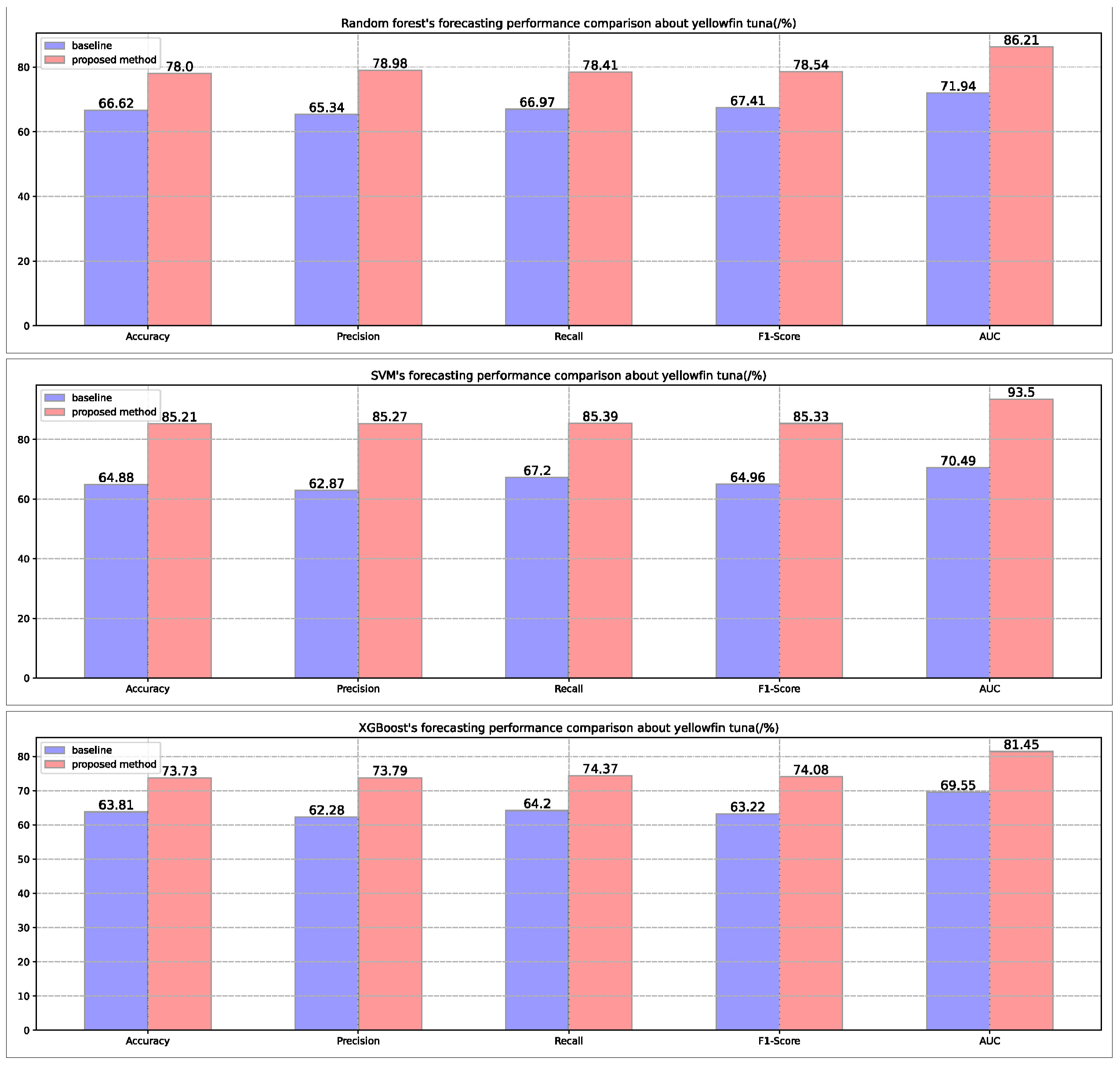

3.3.2. Forecasting performance

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maunder, N.; Punt, E. Standardizing catch and effort data: a review of recent approaches. Fish Res 2004, 70, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; et al. Impacts of spatial scales of fisheries and environmental data on CPUE standardization. Mar Freshwater Res 2009, 60, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A. CPUE standardizations and the construction of indices of stock abundance in a spatially varying fishery using general linear models. Fish Res 2004, 70, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.; Tuck, G.; Tsuji, S.; Nishida, T. Indices of abundance for southern blue-fin tuna from analysis of fine-scale catch and effort data. Working Paper SBFWS/96/16 Presented at the Second CCSBT Scientific Meeting, Hobart, Australia, August 26–September 6, 1996.

- Shono, H. Application of the Tweedie distribution to zero-catch data in CPUE analysis. Fish Res 2008, 93, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorson, T.; Ward, J. Accounting for space–time interactions in index standardization models Fish Res 2013, 147, 426–433. 147.

- Ralston, S.; Dick, J. The status of black rockfish (Sebastes melanops) off Oregon and northern Washington in 2003. Stock Assessment and Fishery Evaluation, Pacific Fishery Management Council, Portland, Oregon, America, 2003.

- Lambert, D. Zero-inflated Poisson regression, with an application to defects in manufacturing. Technometrics 1992, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakita, M.; Minami, M.; Eguchi, S.; Lennert, E. An introduction to the predictive technique AdaBoost with a comparison to generalized additive models. Fish Res 2005, 76, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northcutt, G.; Jiang, L.; Chuang, L. Confident learning: Estimating uncertainty in dataset labels. JAIR 2021, 70, 1373–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Li, T.; Zhang, T.; et al. Comparison of machine learning models within different spatial resolutions for predicting the bigeye tuna fishing grounds in tropical waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Fisheries Oceanography 2023, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northcutt, G.; Jiang, L.; Chuang, L. Feng, Y.; Chen, X.; Gao, F.; Liu, Y. Impacts of changing scale on Getis-Ord Gi* hotspots of cpue: A case study of the neon flying squid (ommastrephes bartramii) in the northwest pacific ocean. Acta Oceanologica Sinica 2018, 37, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Akinwande, O.; Dikko, G.; Samson, A. Variance inflation factor: As a condition for the inclusion of suppressor variable(s) in regression analysis. Open Journal of Statistics 2015, 5, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Chen, Z.; Luo, Y.; Yi, J.; Bailey, J. Symmetric cross entropy for robust learning with noisy labels. ICCV 2019, 322–330. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.; Yao, Q.; Yu, X.; Niu, G.; Xu, M.; Hu, W.; Tsang, I.; Sugiyama, M. Co-teaching: Robust training of deep neural networks with extremely noisy labels. NeurIPS 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Pleiss, G.; Sun, Y.; Weinberger, Q. On calibration of modern neural networks. ICML 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northcutt, C. G.; Athalye, A.; Mueller, J. Pervasive label errors in test sets destabilize machine learning benchmarks. ICLR 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support vector networks. Machine Learning 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. ACM SIGKDD 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Chen, Z.; Luo, Y.; Yi, J.; Bailey, J. Symmetric cross entropy for robust learning with noisy labels. ICCV 2019, 322–330. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).