Submitted:

29 August 2023

Posted:

30 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (1)

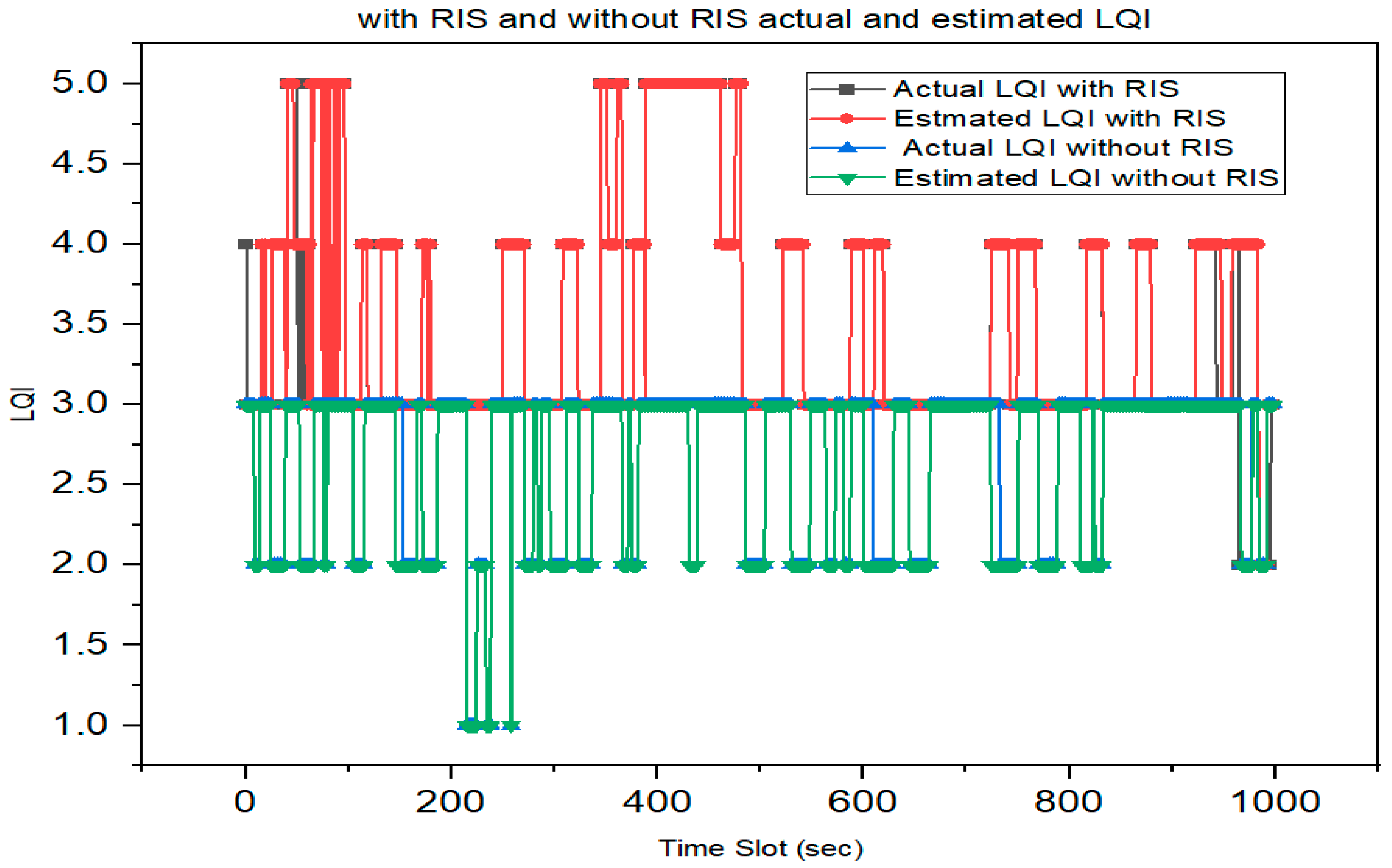

- Numerous studies in the literature assess the quality of links in communication systems that utilize UAVs [17,18,19]. This article accurately estimates link quality in UAV-based communication systems by considering slow fading and fast fading while integrating RIS. We have created a communication system for urban users integrating RIS and UAV. This system effectively addresses issues with signal propagation between UAV and users in urban environments, accounting for building blockage effects.

- (2)

- We have proposed a GRU-based model for estimating link quality in UAV-assisted wireless networks by leveraging the full capabilities of UAV and RIS, including considering UAV trajectory and RIS passive phase shift.

- (3)

- We provide numerical results that demonstrate the benefits of the RIS-assisted UAV communication system in terms of accurate estimates of the link quality of UAVs and GUs.

2. Related work

3. System Model

3.1. Channel Model

3.1.1. UAV- GU link

3.2.2. UAV-RIS-GU link

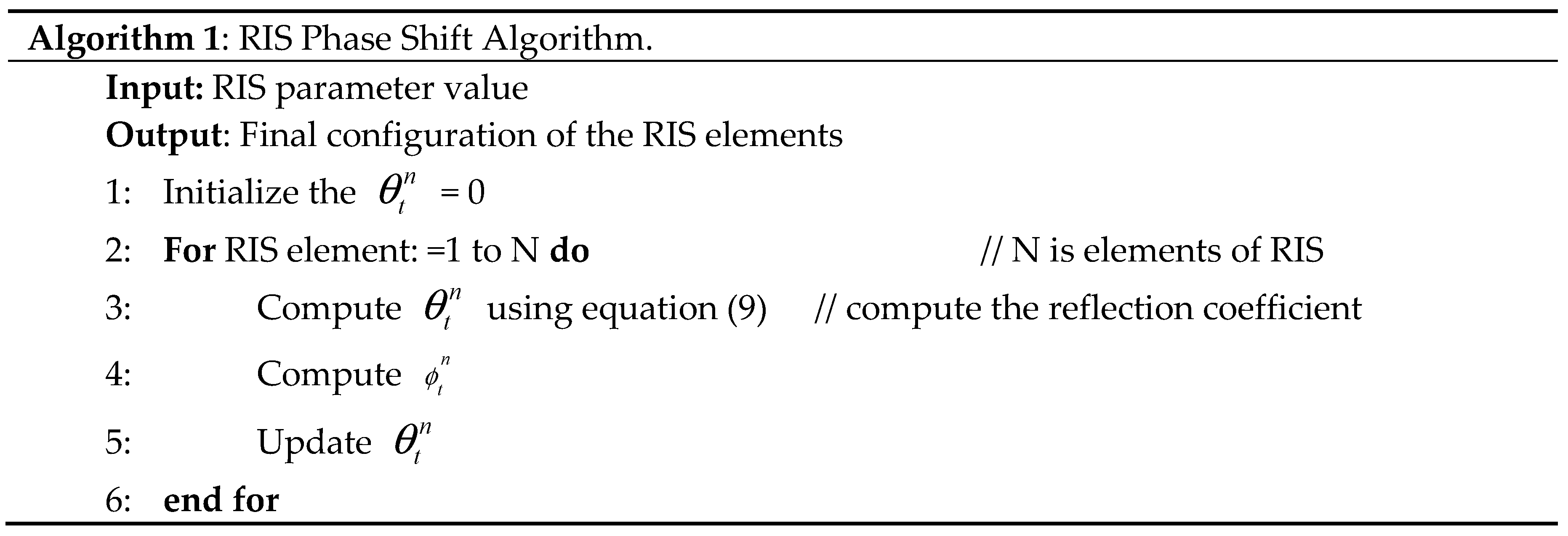

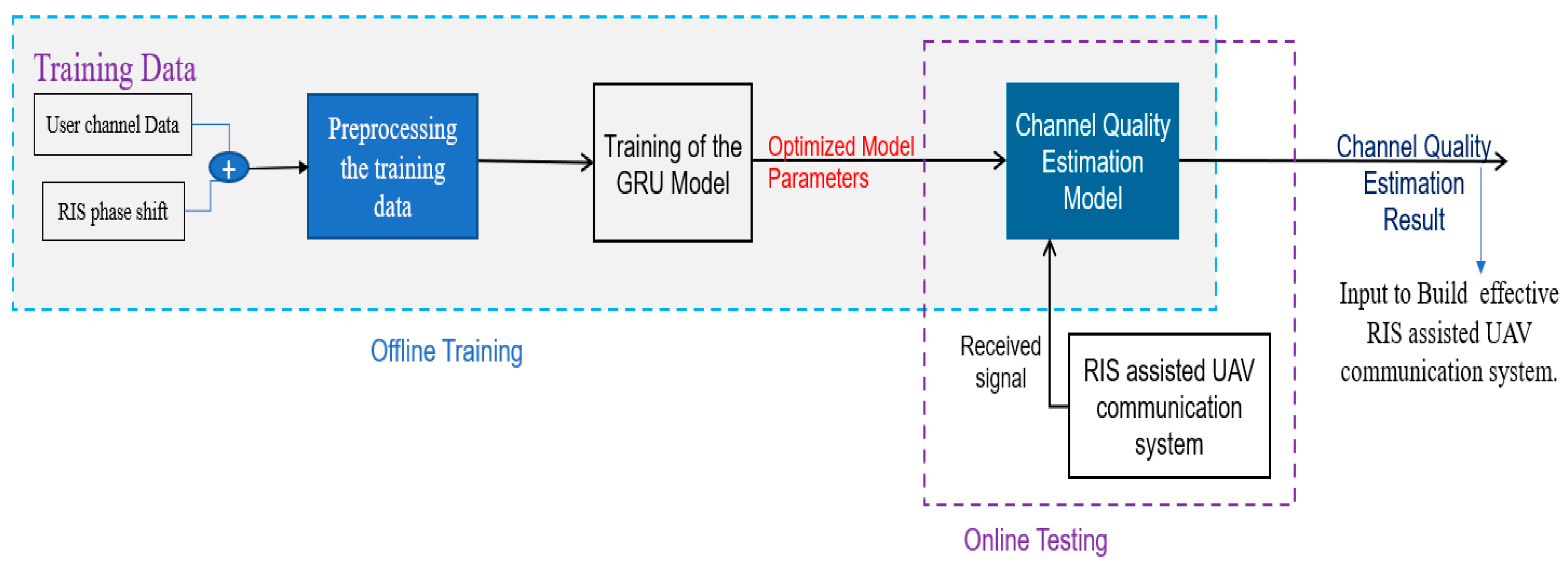

4. Proposed Method

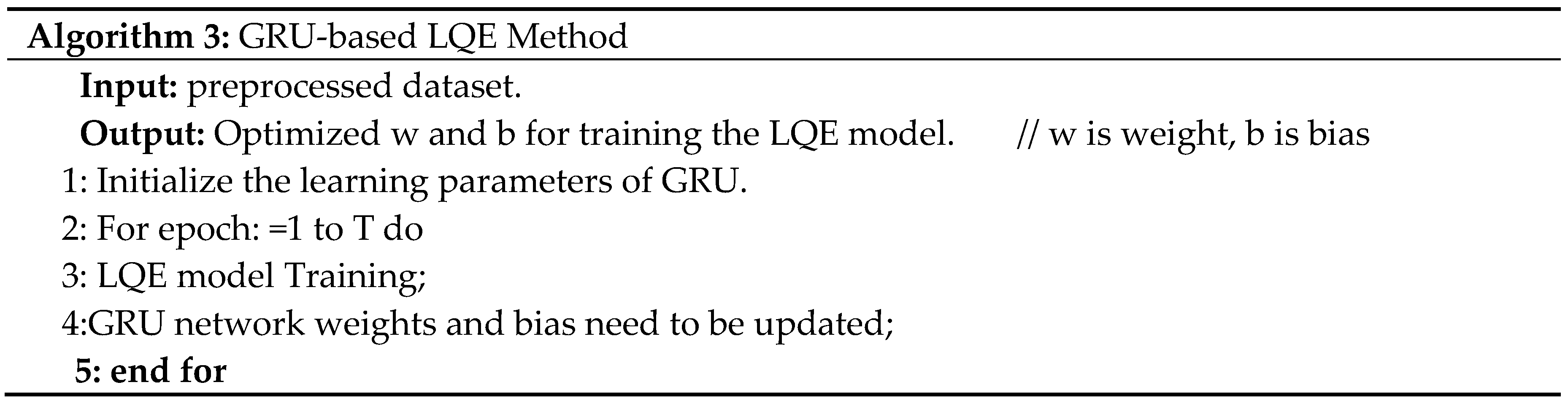

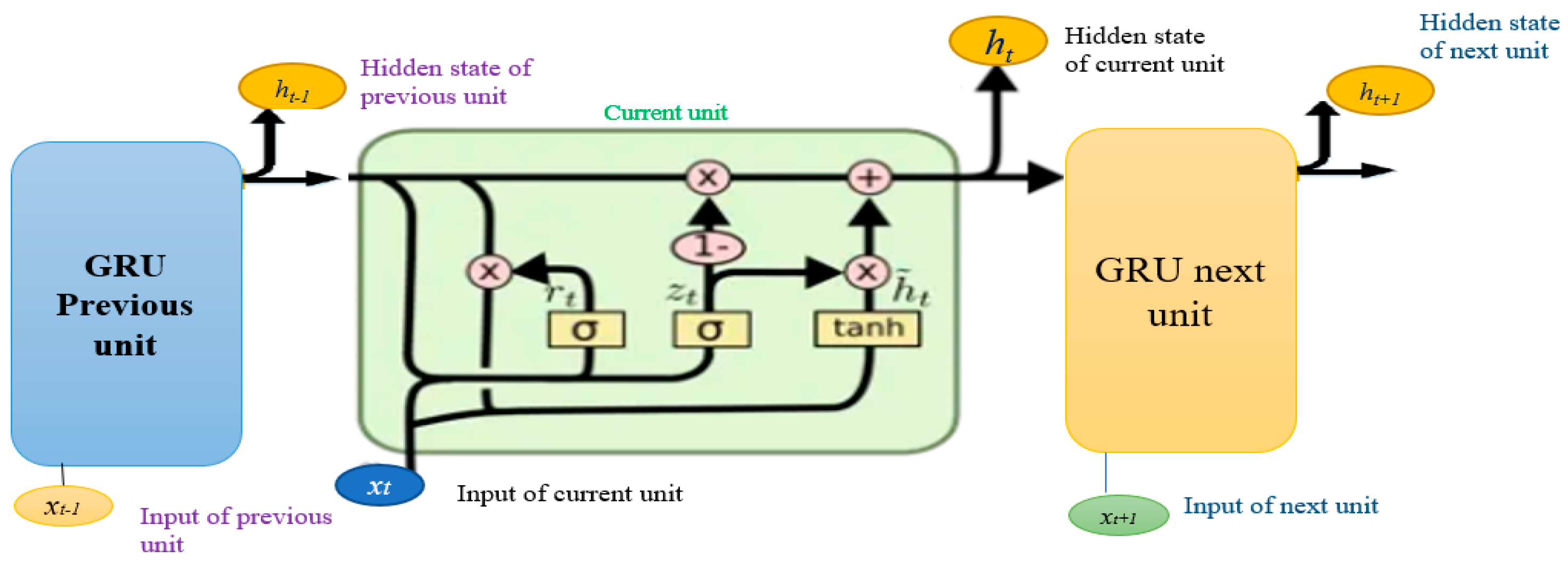

4.1. GRU-Based Link Quality Estimation Model

4.1.1. User Channel Data Simulation

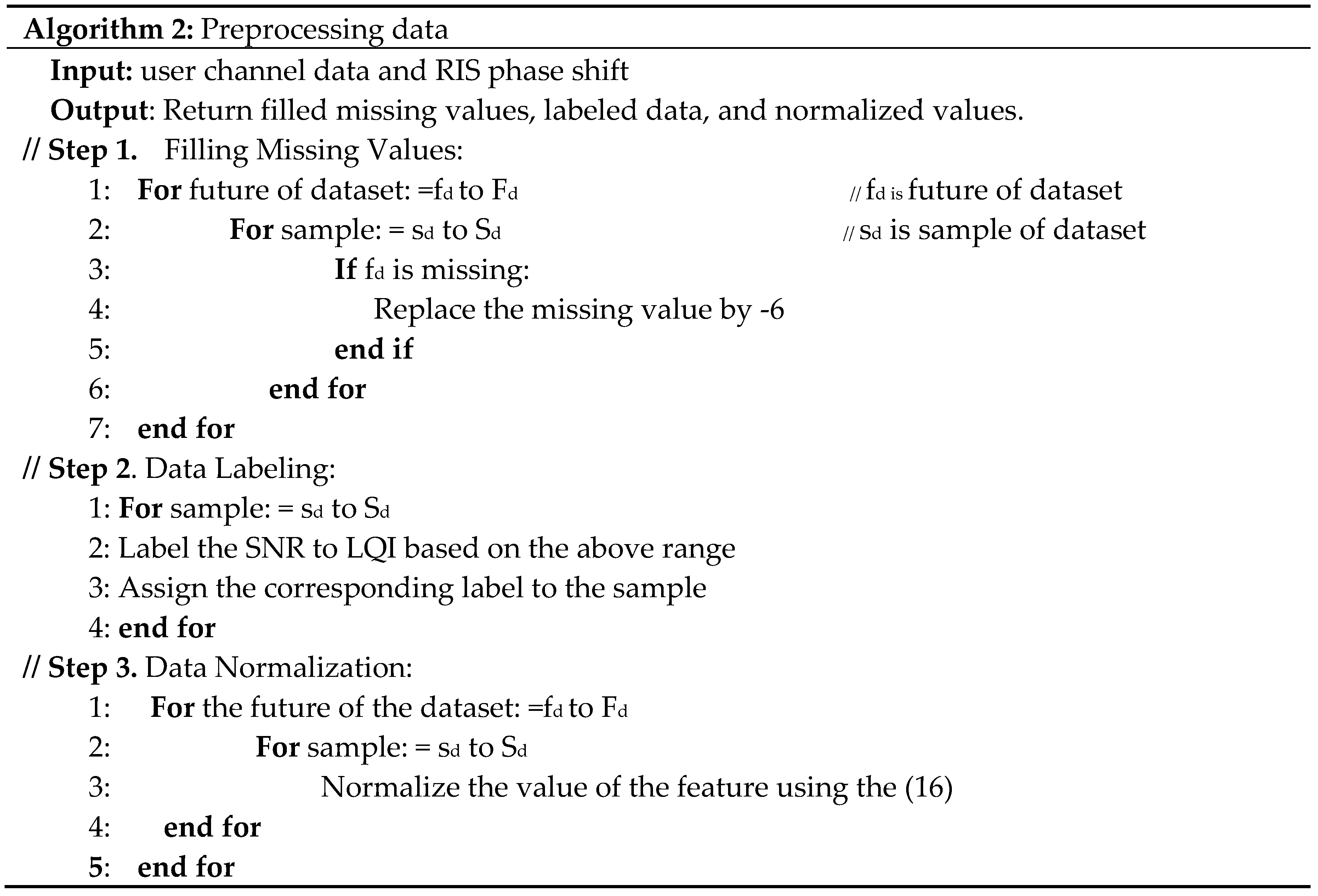

4.1.2. Data Preprocessing

4.1.3. Build Link Quality Estimation Model

5. Result

5.1. Simulation Setup

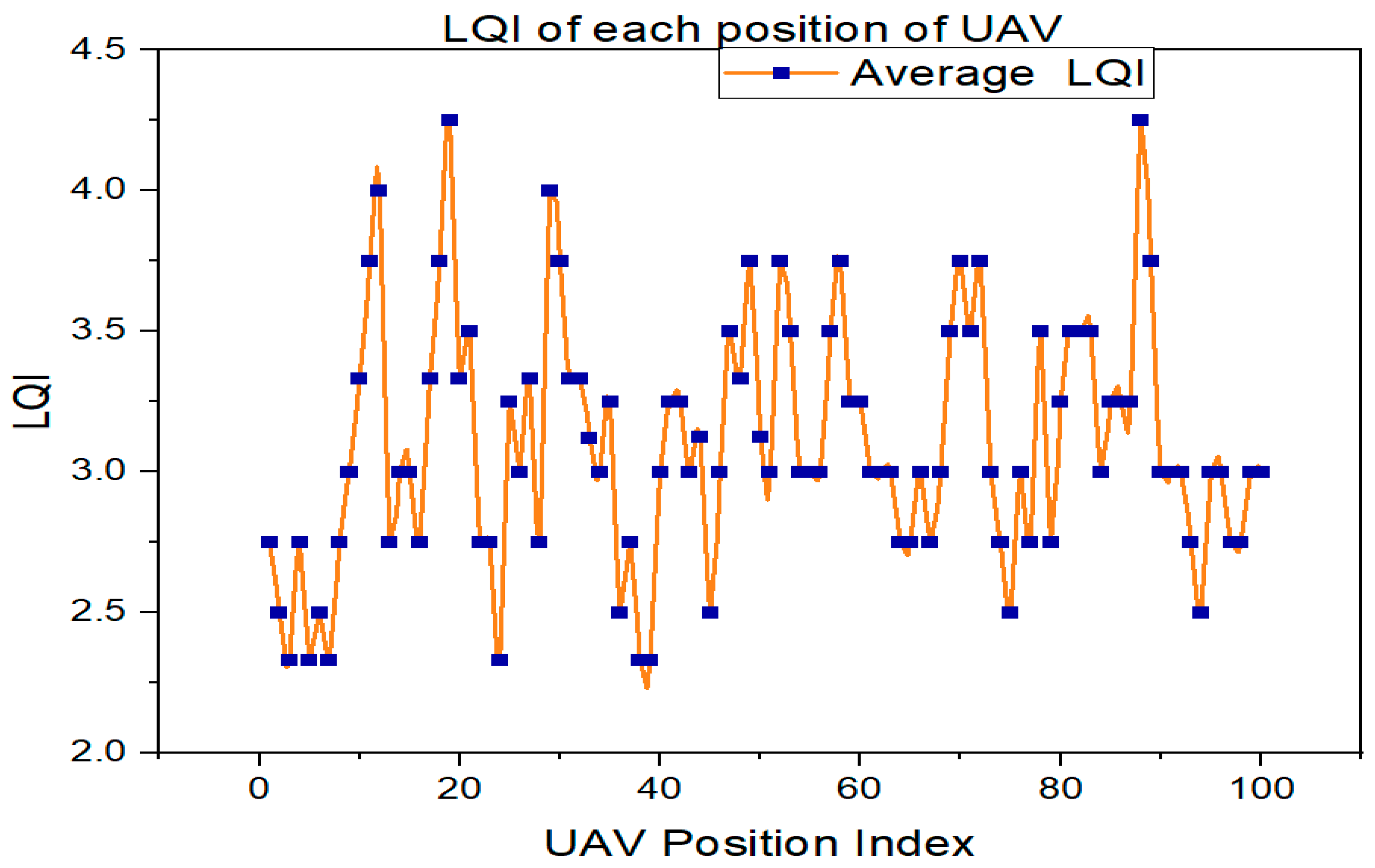

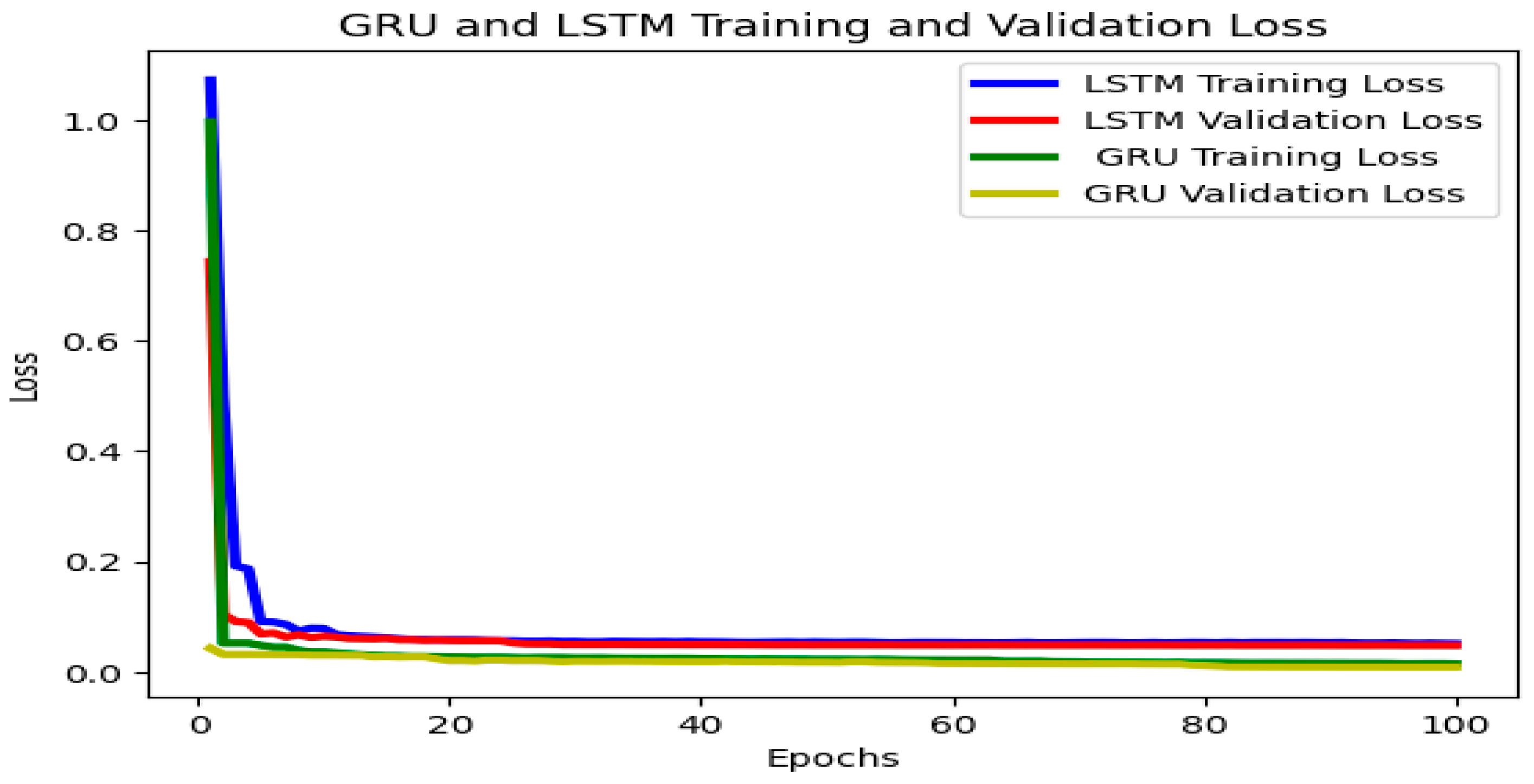

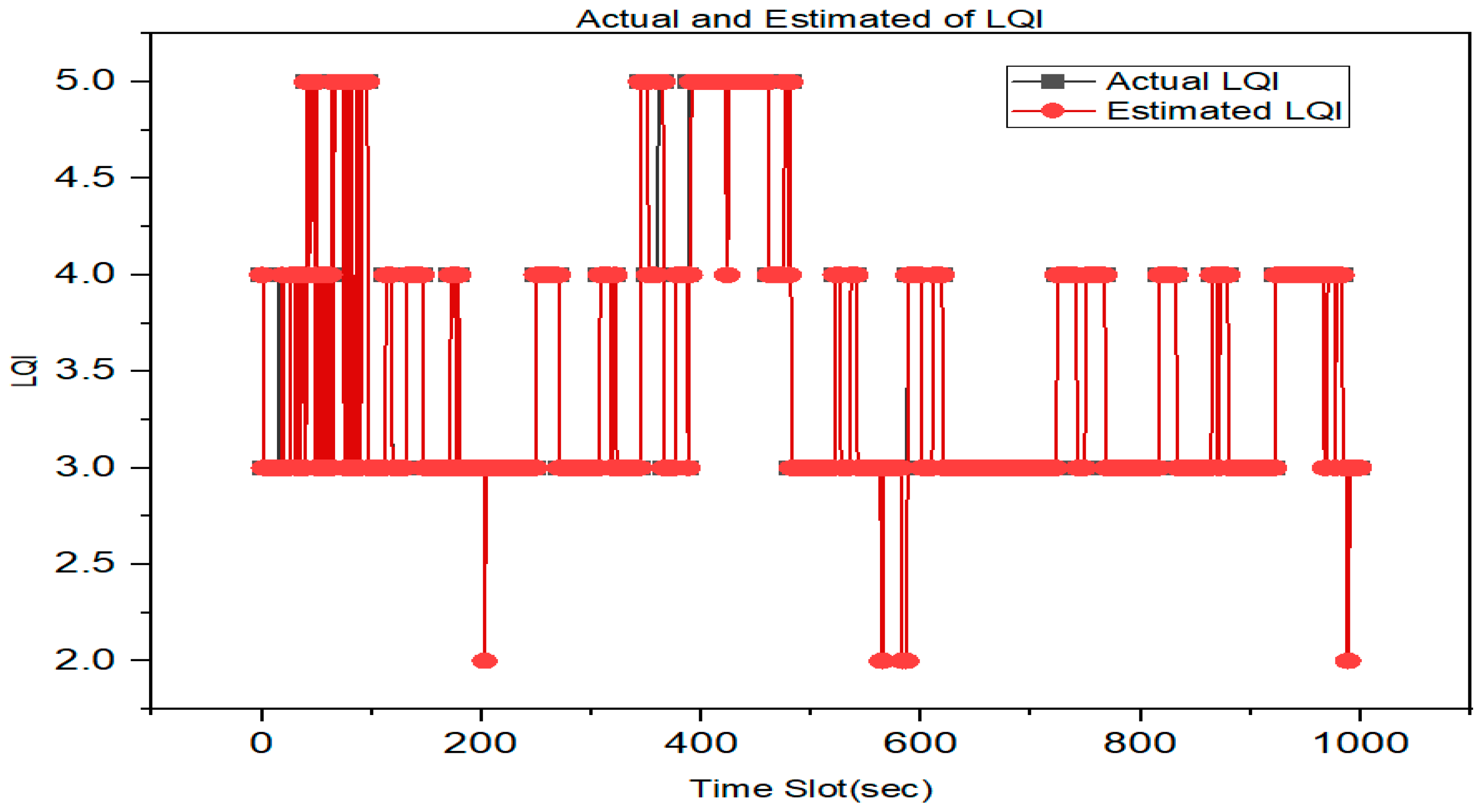

5.2. Result and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balador, A.; Kouba, A.; Cassioli, D.; Foukalas, F.; Severino, R.; Stepanova, D.; Agosta, G.; Xie, J.; Pomante, L.; Mongelli, M.; et al. Wireless Communication Technologies for Safe Cooperative Cyber Physical Systems. Sensors (Switzerland) 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Lim, T.J. Wireless Communications with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: Opportunities and Challenges. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telli, K.; Kraa, O.; Himeur, Y.; Ouamane, A.; Boumehraz, M.; Atalla, S.; Mansoor, W. A Comprehensive Review of Recent Research Trends on Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Systems 2023, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Lim, T.J. Wireless Communications with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: Opportunities and Challenges. IEEE Communications Magazine 2016, 54, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Liu, M.; Chen, Y.; Sun, S.; Li, Z.; Guo, X. RIS-Assisted UAV for Fresh Data Collection in 3D Urban Environments: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. IEEE Trans Veh Technol 2023, 72, 632–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElMossallamy, M.A.; Zhang, H.; Song, L.; Seddik, K.G.; Han, Z.; Li, G.Y. Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces for Wireless Communications: Principles, Challenges, and Opportunities. 2020.

- Park, K.W.; Kim, H.M.; Shin, O.S. A Survey on Intelligent-Reflecting-Surface-Assisted UAV Communications. Energies (Basel) 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogaku, A.C.; Do, D.T.; Lee, B.M.; Nguyen, N.D. UAV-Assisted RIS for Future Wireless Communications: A Survey on Optimization and Performance Analysis. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 16320–16336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, A.S.; Rahman, T.F.; Marojevic, V. UAVs with Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces: Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. 2020.

- Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers 2020 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC) : Proceedings : Dublin, Ireland, 7-11 June 2020. ISBN 9781728174402.

- Ren, H.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, Z.; Li, L.; Pan, C. Energy Minimization in RIS-Assisted UAV-Enabled Wireless Power Transfer Systems. IEEE Internet Things J 2023, 10, 5794–5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsan, S.A.H.; Othman, N.Q.H.; Li, Y.; Alsharif, M.H.; Khan, M.A. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): Practical Aspects, Applications, Open Challenges, Security Issues, and Future Trends. Intell Serv Robot 2023, 16, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Cai, W.; Lin, J.; Zhang, S.; Shi, W.; Yan, S.; Shu, F. STAR-RIS-UAV-Aided Coordinated Multipoint Cellular System for Multi-User Networks. Drones 2023, 7, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Ihsan, A.; Khan, W.U.; Ranjha, A.; Zhang, S.; Wu, S.X. Energy-Efficient Beamforming and Resource Optimization for AmBSC-Assisted Cooperative NOMA IoT Networks. 2022.

- Luo, X.; Liu, L.; Shu, J.; Al-Kali, M. Link Quality Estimation Method for Wireless Sensor Networks Based on Stacked Autoencoder. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 21572–21583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerar, G.; Yetgin, H.; Mohorčič, M.; Fortuna, C. On Designing a Machine Learning Based Wireless Link Quality Classifier. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dargie, W.; Wen, J. A Link Quality Estimation Model for a Joint Deployment of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Wireless Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings - International Conference on Computer Communications and Networks, ICCCN; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 1 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tarekegn, G.B.; Juang, R.T.; Lin, H.P.; Munaye, Y.Y.; Wang, L.C.; Jeng, S.S. Channel Quality Estimation in 3D Drone Base Station for Future Wireless Network. In Proceedings of the 2021 30th Wireless and Optical Communications Conference, WOCC 2021; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc, 2021; pp. 236–239. [Google Scholar]

- Tarekegn, G.B.; Juang, R.T.; Lin, H.P.; Munaye, Y.Y.; Wang, L.C.; Bitew, M.A. Deep-Reinforcement-Learning-Based Drone Base Station Deployment for Wireless Communication Services. IEEE Internet Things J 2022, 9, 21899–21915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Joung, J.; Kang, J. A Study on Probabilistic Line-of-Sight Air-to-Ground Channel Models.

- Van Brandt, S.; Van Thielen, R.; Verhaevert, J.; Van Hecke, T.; Rogier, H. Characterization of Path Loss and Large-Scale Fading for Rapid Intervention Team Communication in Underground Parking Garages. Sensors (Switzerland) 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Chen, Z.; Chen, W.; Li, Z.; Chi, Y.; Han, C.; Li, S. Joint Channel Estimation and Data Rate Maximization for Intelligent Reflecting Surface Assisted Terahertz MIMO Communication Systems. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 99565–99581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yu, H.; Kang, X.; Joung, J. Discrete Phase Shifts of Intelligent Reflecting Surface Systems Considering Network Overhead. Entropy 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Liu, L.; Shu, J.; Al-Kali, M. Link Quality Estimation Method for Wireless Sensor Networks Based on Stacked Autoencoder. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 21572–21583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Fu, J.; Liang, J. Residual Recurrent Neural Networks for Learning Sequential Representations. Information (Switzerland) 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarekegn, G.B.; Tai, L.C.; Lin, H.P.; Tesfaw, B.A.; Juang, R.T.; Hsu, H.C.; Huang, K.L.; Singh, K. Applying T-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding for Improving Fingerprinting-Based Localization System. IEEE Sens Lett 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tarekegn, G.B.; Juang, R.T.; Lin, H.P.; Tai, L.C.; Munaye, Y.Y.; Bitew, M.A. SRCLoc: Synthetic Radio Map Construction Method for Fingerprinting Outdoor Localization in Hybrid Networks. IEEE Sens J 2022, 22, 15574–15583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, S.; Benedens, T.; Schramm, D. Hyperparameter Optimization Techniques for Designing Software Sensors Based on Artificial Neural Networks. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Transmit power p | 0.1 W |

| Noise Power No | -80 dB |

| Path loss at 1m α | -20 dB |

| Path loss for LoS ηLoS | 0.2 dB |

| Path loss for NLoS ηNLoS | 21 dB |

| Carrier frequency fc | 2 GHz |

| Rician factor K1 | 3dB |

| Speed of light c | 3 × 108 m/s |

| Path loss RIS-GU link β | 2.8 |

| Number of RIS elements N | 9 |

| quantization bits b | 4 bits |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of hidden layers | 3(128,64,32 neurons) |

| Dropout | 0.2 |

| Batch size | 32 |

| Learning rate | 0.001 |

| Loss function | Cross-entropy |

| Optimization algorithm | Adam |

| Number of epochs | 100 |

| Performance Metrics | LSTM | GRU |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.95 | 0.96 |

| Cross-entropy | 0.12 | 0.062 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).