Submitted:

28 August 2023

Posted:

30 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

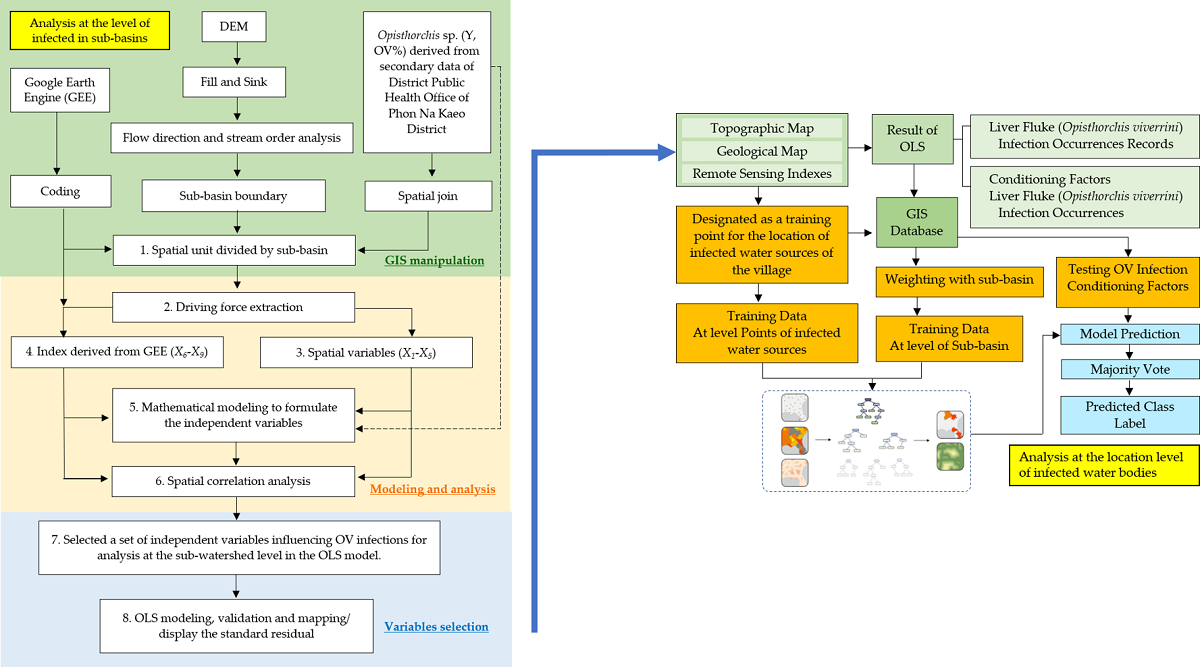

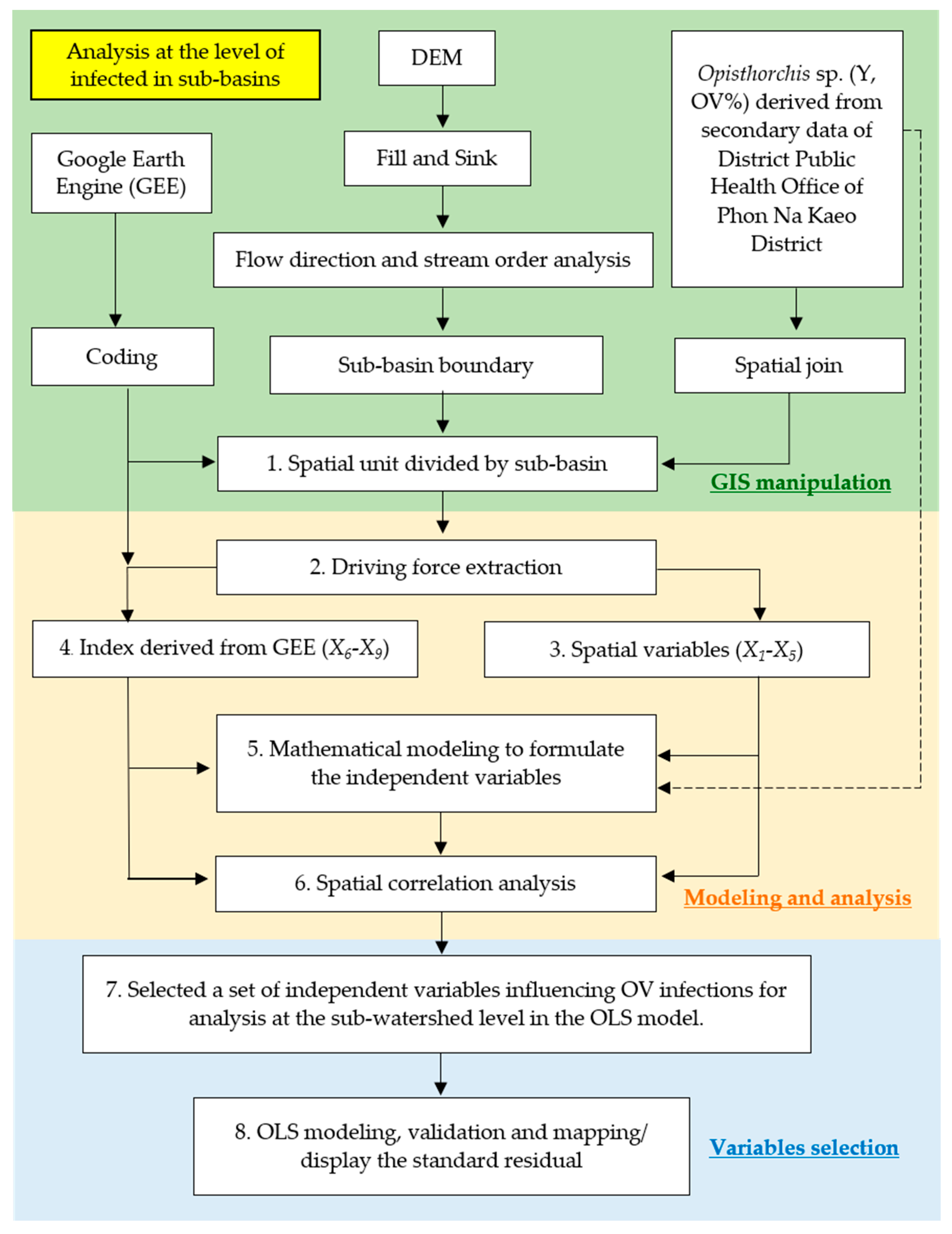

2. Materials and Methods

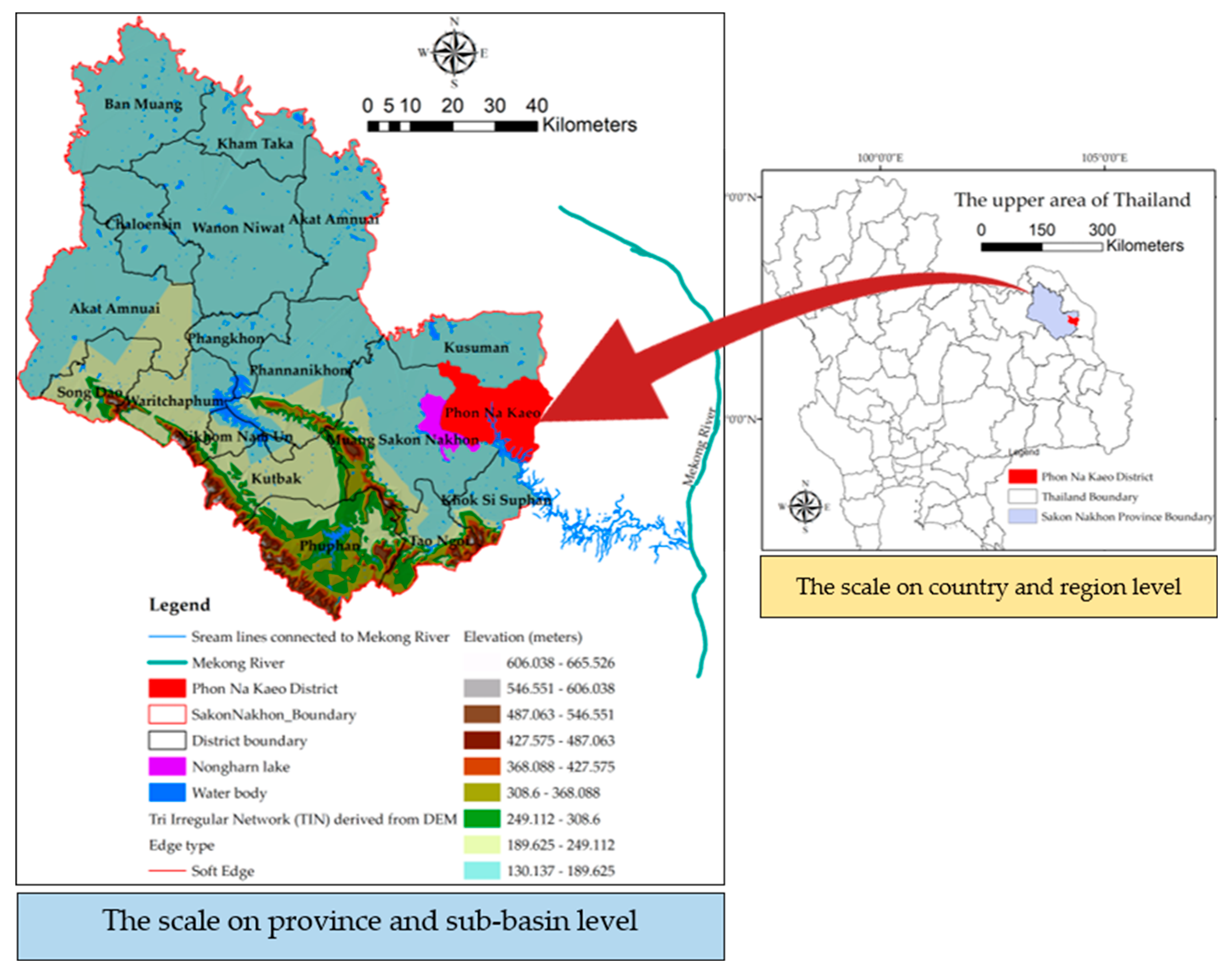

2.1. The Study Area

2.2. Datasets and Analyses

2.3. Independent variable modeling

2.4. Ordinary Least Square (OLS) approach for spatial modeling (analysis at the level of infected in sub-basins)

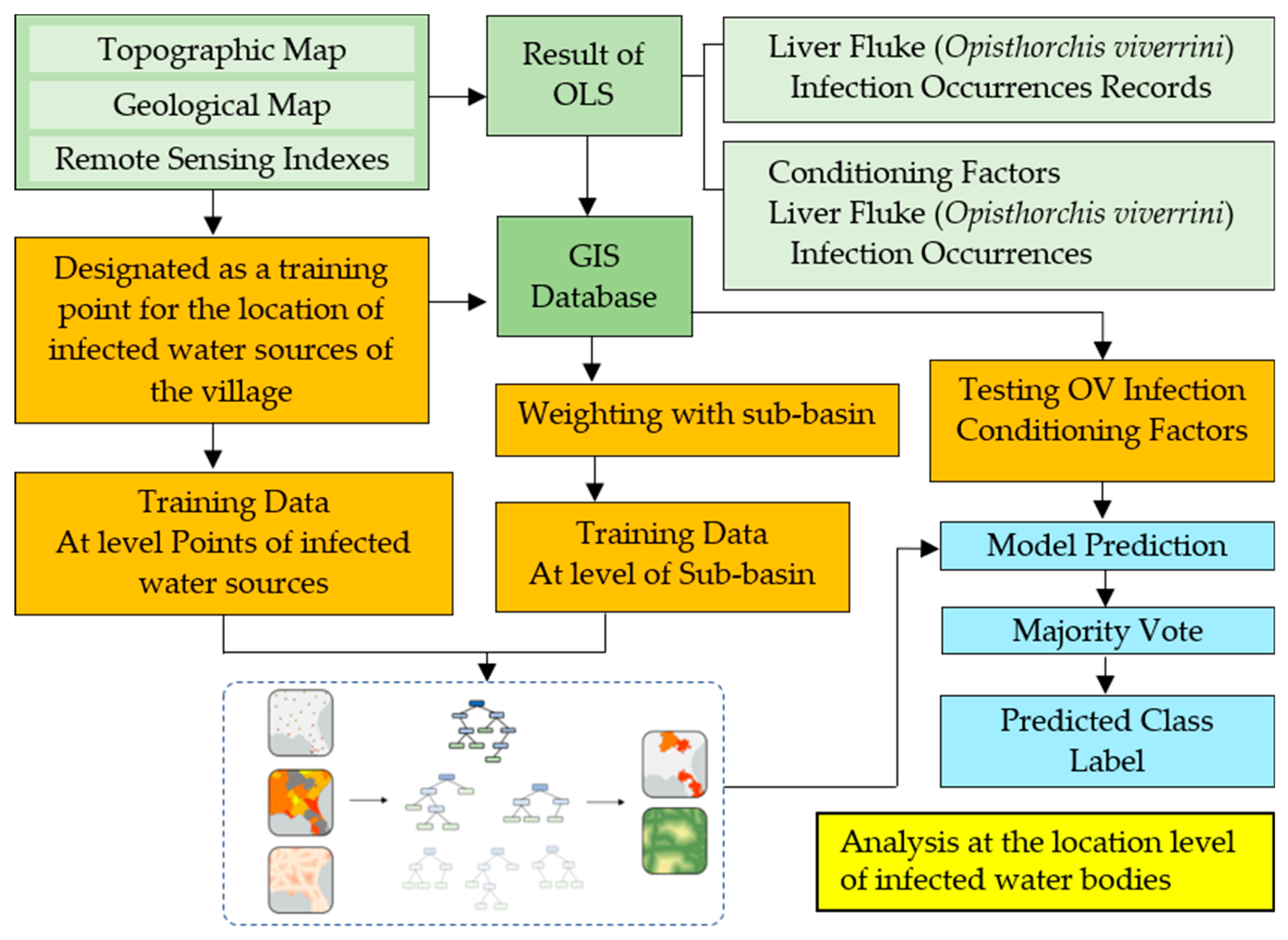

2.5. Forest-Based Classification and Regression (Analysis at the location level of infected water bodies)

3. Results

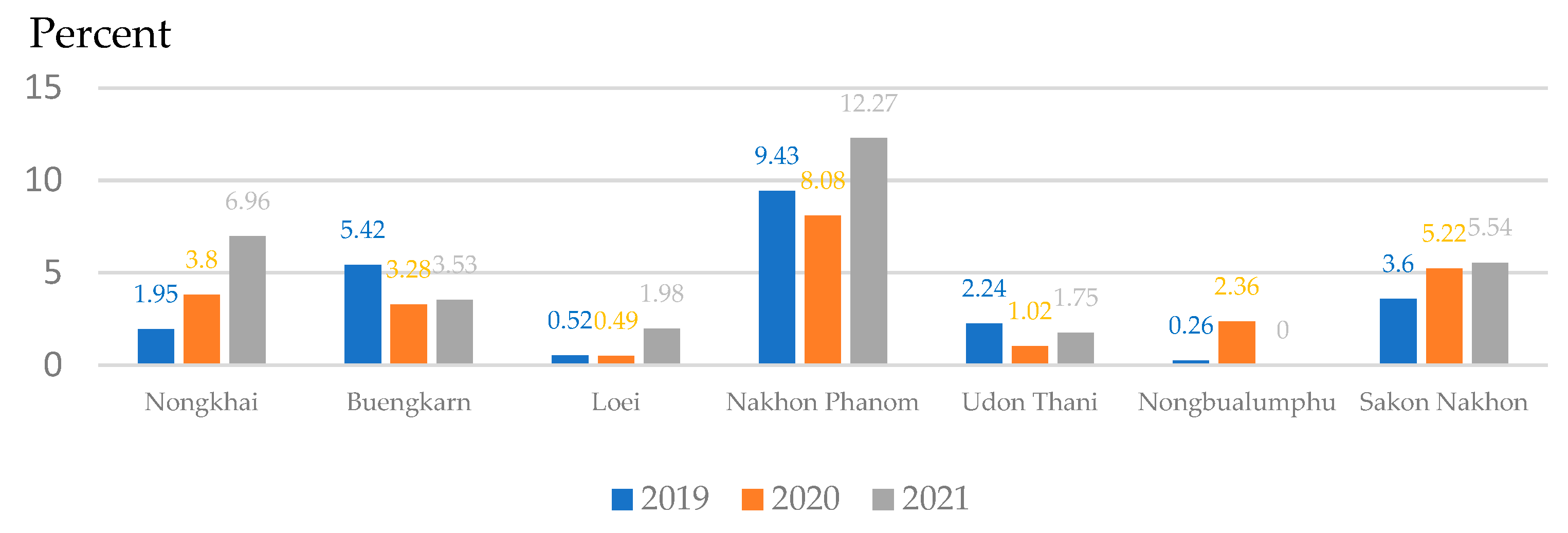

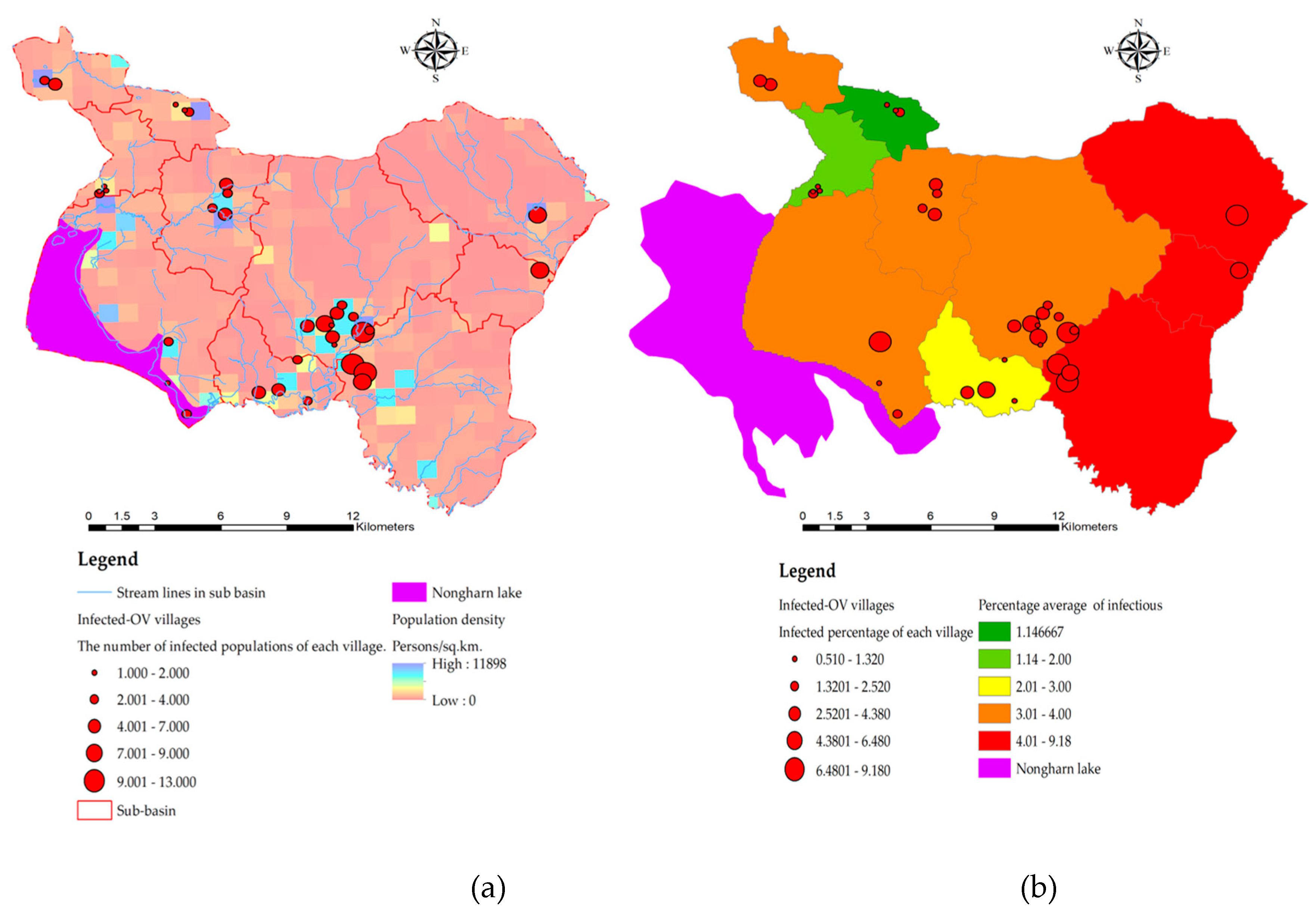

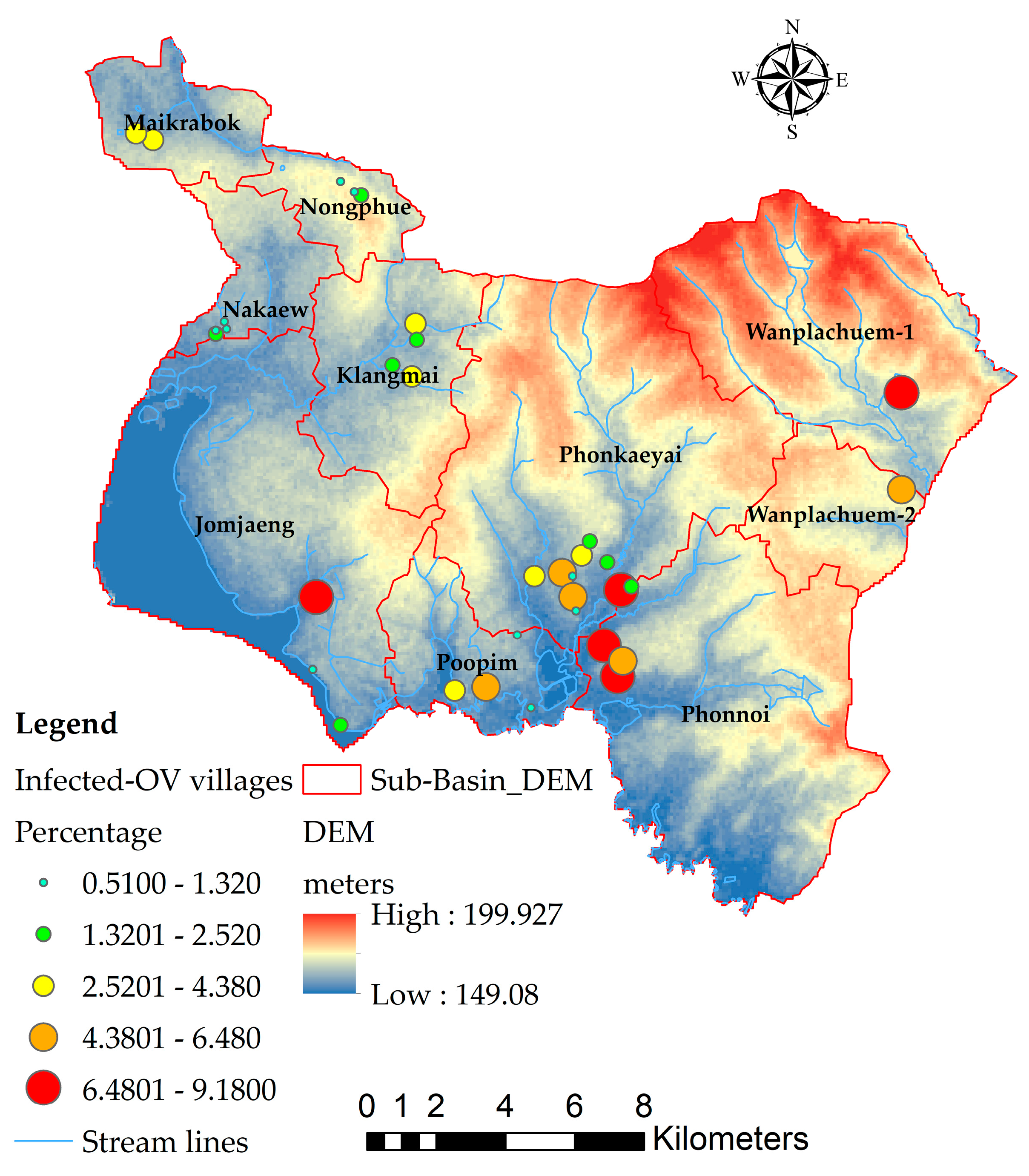

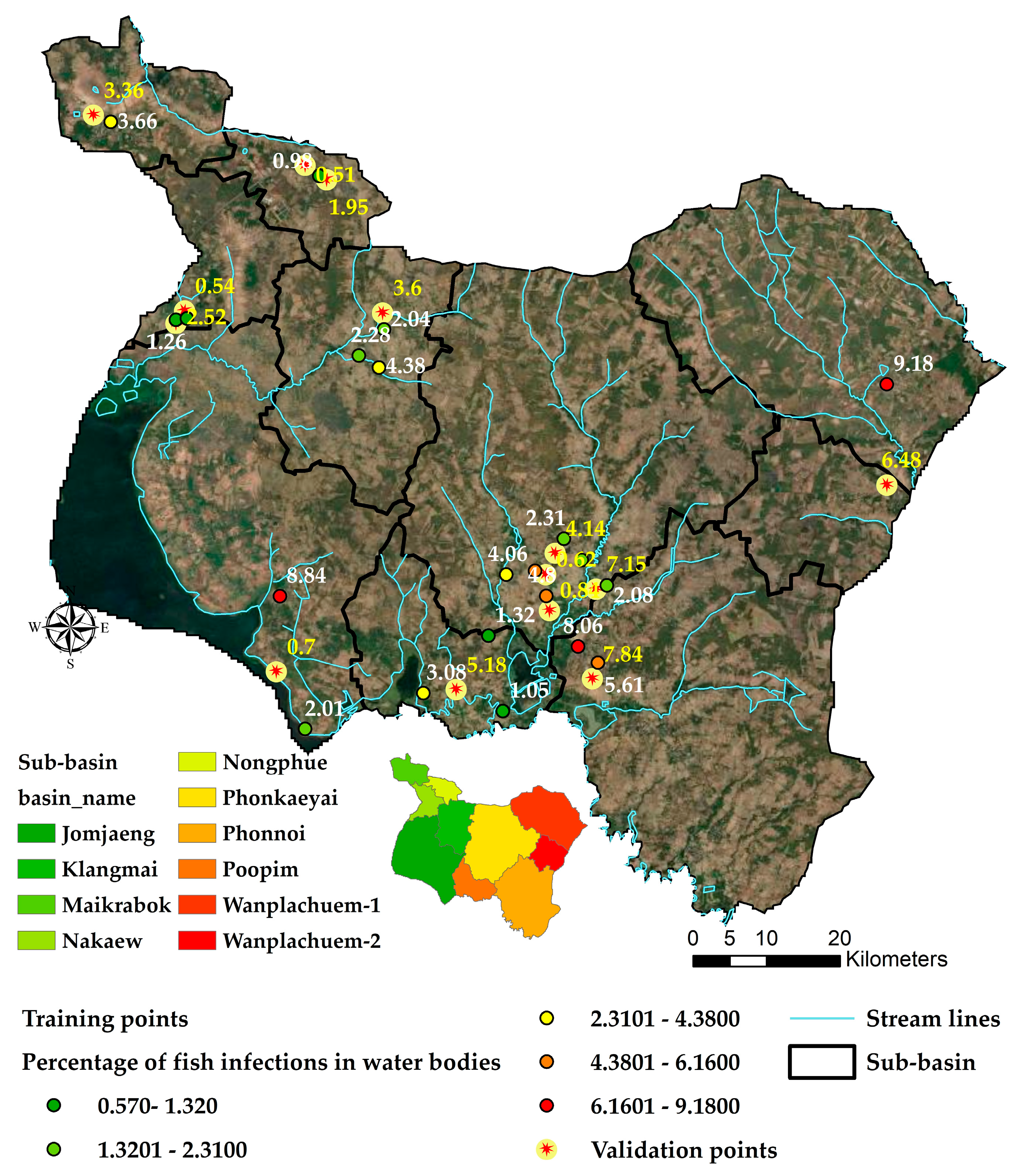

3.1. Mapping of The Spatial OV Infection (Y, Dependent Variable)

3.2. Mapping of The Independent Variables

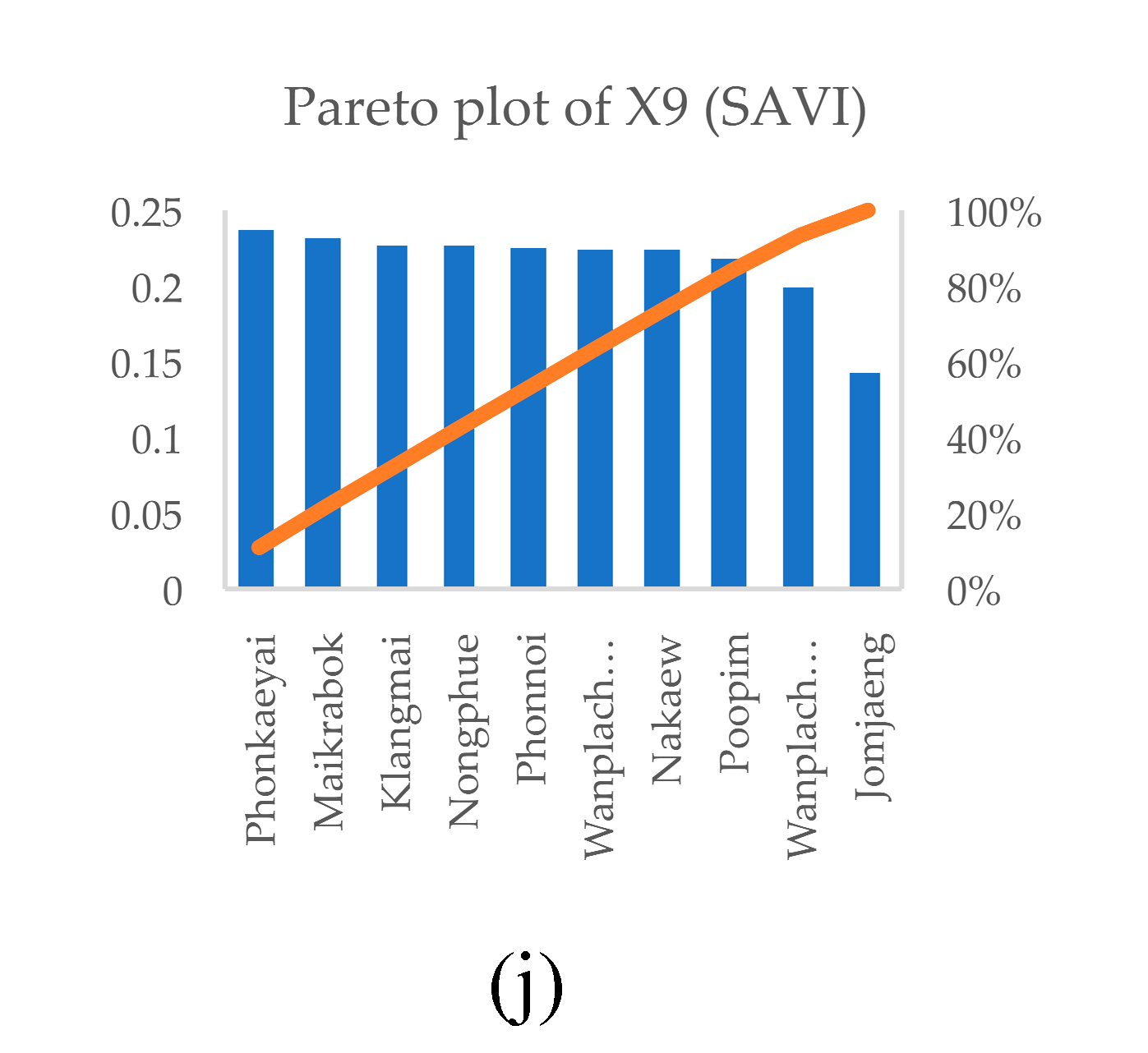

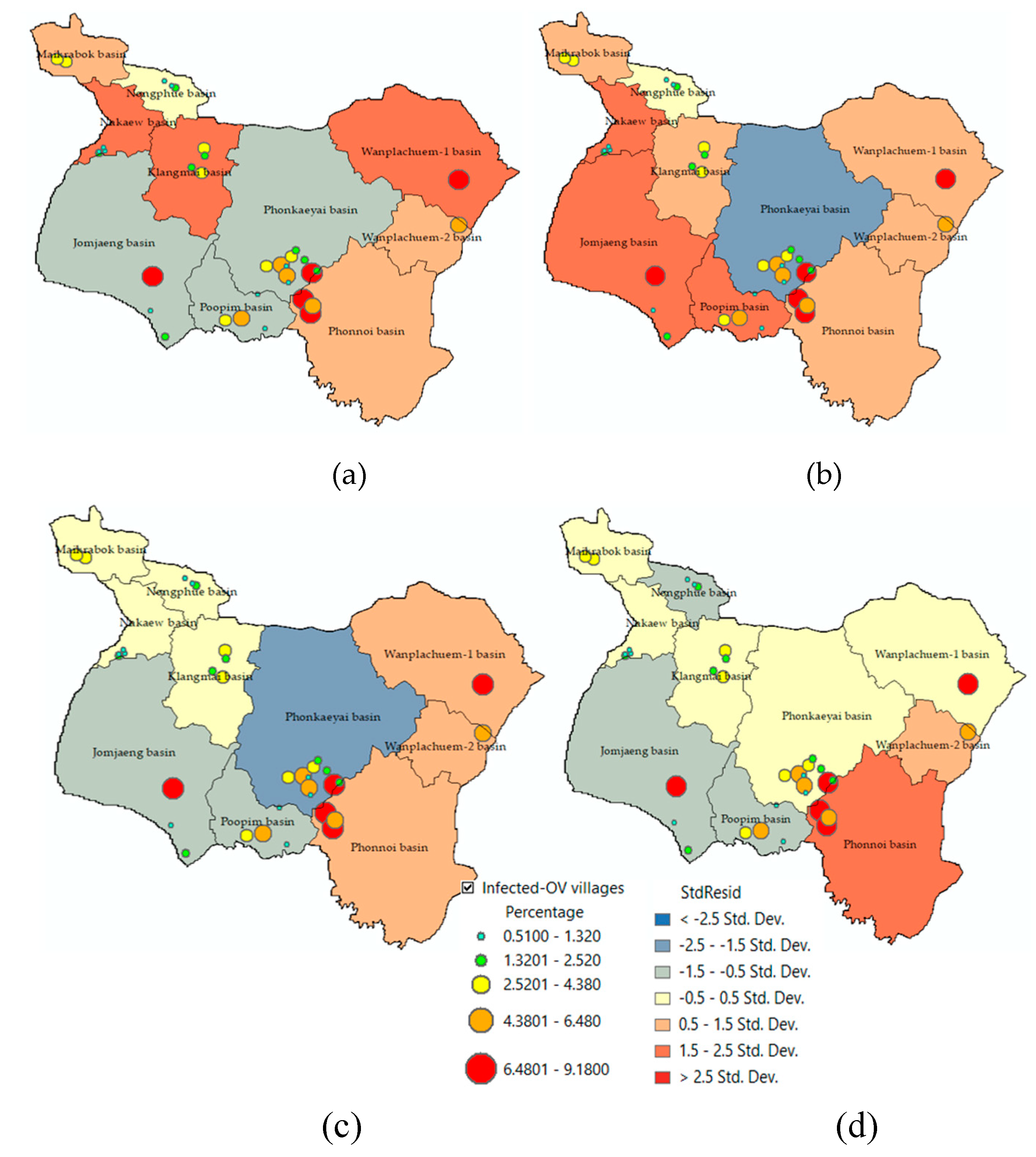

3.3. Spatial Analysis of Factors Associated with Spatial Liver Fluke (Opisthorchis viverrini) Infection

3.4. Optimal OLS Model for Predicted with Liver Fluke (Opisthorchis viverrini) Infection (Watershed level)

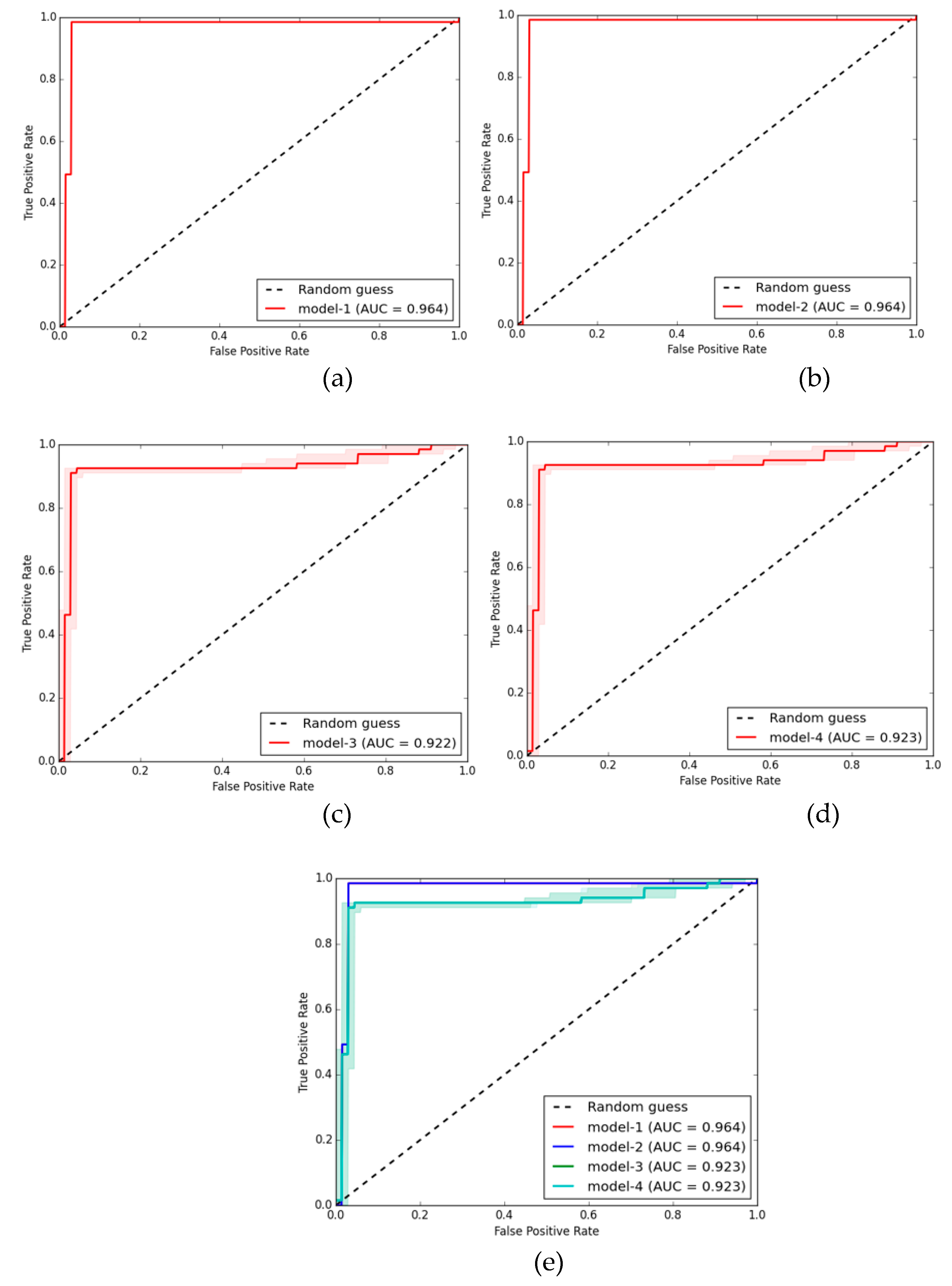

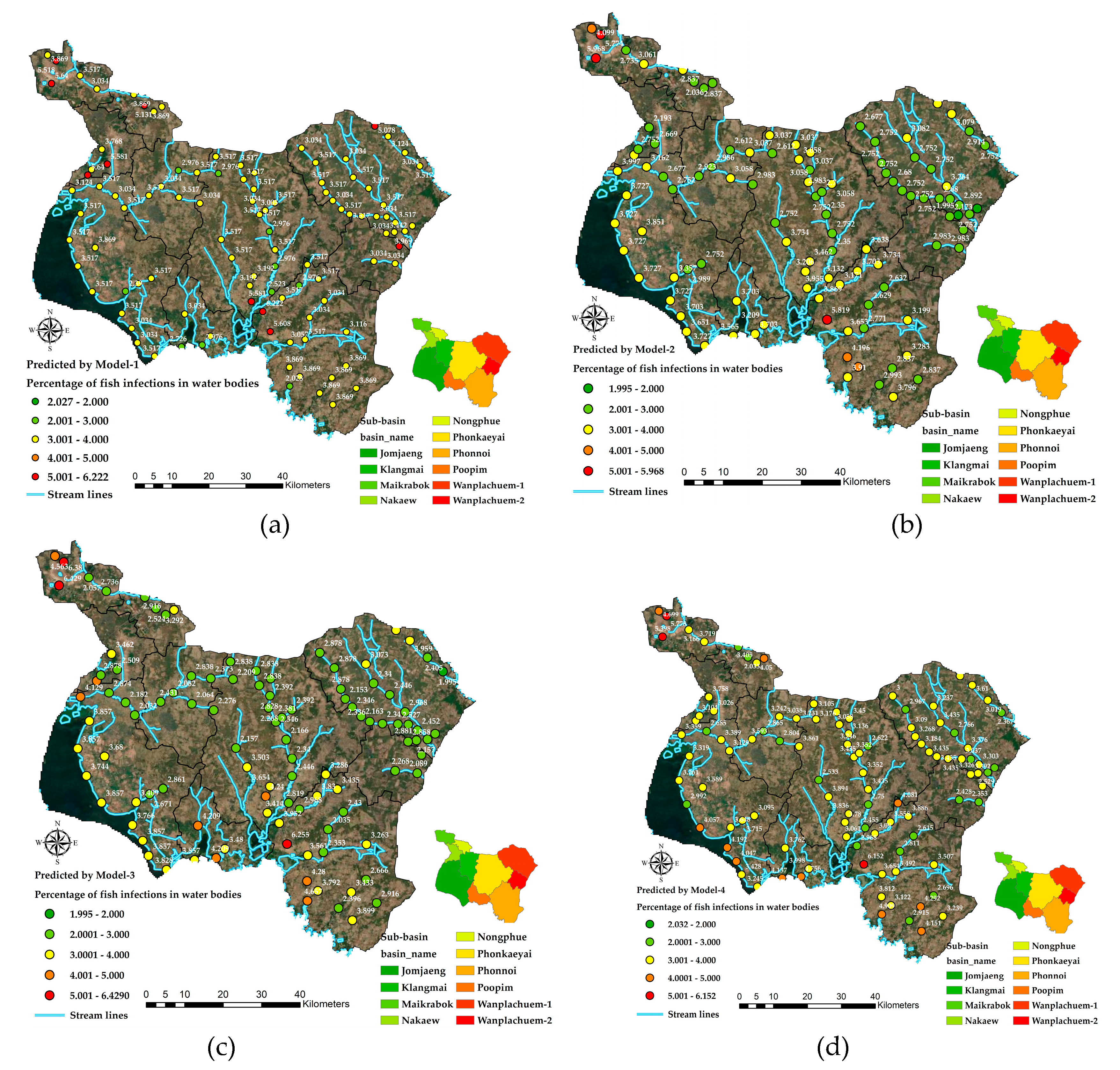

3.5. Spatial prediction of OV-Infection using Forest-based Classification and Regression (FCR) (Location level)

3.6. Spatial Prediction of OV-infected

| Training Data: Regression Diagnostics | Model-1 | Model-2 | Model-3 | Model-4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-Squared | 0.775 | 0.853 | 0.859 | 0.849 |

| p-value | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Standard Error | 0.053 | 0.06 | 0.043 | 0.051 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Redundancy of Independent Variable Sets

4.2. Limitations of Spatial OLS Model

4.3. FCR Improvement Approach for Spatial Prediction

5. Conclusions

- An OLS model was developed in this study to track liver fluke infection. This spatial statistical model is suitable for analysis at the local process level, and the results were compared to confirm that Model-3 was more accurate and more appropriate than Model-1, Model-2, and Model-4. However, to make full use of the model, the spatial unit data layer should first be designed to separate the variables accordingly and independently [97,98,99]. Often, OLS models provide low coefficients of decision because subarea unit assignments are not suitable. In this study, it could be used as a prototype of a method for analyzing spatial relationships with liver fluke infections by creating sub-basin units with continuous adjacent boundaries. Local fluke case data should be continuously collected so that a curve can be created between the percentage of infected people and an independent set of variables. The factors used in this study are only prototypes of OLS model testing; in more advanced studies, spatial survey factors such as soil moisture in the field where mollusks are found should be used. Mathematical modeling is used to adjust database measures so that they can be measured together as an alternative approach to optimizing the prediction of the model [22]. Finally, the results of this study can guide the creation of spatial models at the scale of small watersheds to track spatial infections of liver fluke in other areas with similar watershed characteristics.

- Improving prediction at the position level with machine learning of the FCR method. To improve performance when extracting values from explanatory training raster and calculating distances using explanatory training distance features, consider training the model on 100 percent of the data without excluding data for validation, and choose to create output trained features [27,44]. Although the default number of trees parameter value is 100, this number is not data driven. The number of trees needed increases with the complexity of relationships between the explanatory variables, size of the dataset, and the variable to predict, in addition to the variation of these variables. Increase the number of trees in the forest value and keep track of the (out-of-bags) OOB or classification error [100]. It is recommended that model increase the number of trees value at least 3 times up to at least 500 trees to best evaluate model performance. Tool execution time is highly sensitive to the number of variables used per tree. Using a small number of variables per tree decreases chances of overfitting [27]; however, be sure to use many trees if model is using a small number of variables per tree to improve model performance. To create a model that does not change in every run, a seed can be set in the random number generator environment setting. There will still be randomness in the model, but that randomness will be consistent between runs.

- Guidelines for the prevention and control of liver fluke and bile duct cancer of the Sakon Nakhon Provincial Public Health Office are also included [72,75]: Organizing sanitation systems, managing sewage to break the parasite cycle; teaching and learning in schools and encouraging health literacy; screening for liver fluke in people aged 15 years and over; bile duct cancer screening in people aged 40 years and over with a history of risk and undergone ultrasound; systematic management of referral of suspected cholangiocarcinoma to diagnosis and treatment; safe food and a parasite-free fish campaign; and having a system for receiving and referring patients from hospitals to communities and reporting their performance through the reporting system of the Ministry of Public Health or the Isan Cohort database [18]. An examination of prevention and control practices revealed that this spatial model study approach can be used to support sanitation and sewage management policies to break the parasite cycle [2]. In addition, by continuously collecting data on the number of infected people, it is possible to analyze trends using the OLS model of infected people.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geadkaew-Krenc, A.; Krenc, D.; Thanongsaksrikul, J.; Grams, R.; Phadungsil, W.; Glab-ampai, K.; Chantree, P.; Martviset, P. Production and Immunological Characterization of ScFv Specific to Epitope of Opisthorchis Viverrini Rhophilin-Associated Tail Protein 1-like (OvROPN1L). Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 160. [CrossRef]

- Perakanya, P.; Ungcharoen, R.; Worrabannakorn, S.; Ongarj, P.; Artchayasawat, A.; Boonmars, T.; Boueroy, P. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Opisthorchis Viverrini Infection in Sakon Nakhon Province, Thailand. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 6–8. [CrossRef]

- Sadaow, L.; Rodpai, R.; Janwan, P.; Boonroumkaew, P.; Sanpool, O.; Thanchomnang, T.; Yamasaki, H.; Ittiprasert, W.; Mann, V.H.; Brindley, P.J.; et al. An Innovative Test for the Rapid Detection of Specific IgG Antibodies in Human Whole-Blood for the Diagnosis of Opisthorchis Viverrini Infection. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7. [CrossRef]

- Boonjaraspinyo, S.; Boonmars, T.; Ekobol, N.; Artchayasawat, A.; Sriraj, P.; Aukkanimart, R.; Pumhirunroj, B.; Sripan, P.; Songsri, J.; Juasook, A.; et al. Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Intestinal Parasitic Infections: A Population-Based Study in Phra Lap Sub-District, Mueang Khon Kaen District, Khon Kaen Province, Northeastern Thailand. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8. [CrossRef]

- Sripa, B.; Bethony, J.M.; Sithithaworn, P.; Kaewkes, S.; Mairiang, E.; Loukas, A.; Mulvenna, J.; Laha, T.; Hotez, P.J.; Brindley, P.J. Opisthorchiasis and Opisthorchis-Associated Cholangiocarcinoma in Thailand and Laos. Acta Trop. 2011, 120 Suppl, S158-68. [CrossRef]

- Prasongwatana, J.; Laummaunwai, P.; Boonmars, T.; Pinlaor, S. Viable Metacercariae of Opisthorchis Viverrini in Northeastern Thai Cyprinid Fish Dishes--as Part of a Rational Program for Control of O. Viverrini-Associated Cholangiocarcinoma. Parasitol. Res. 2013, 112, 1323–1327. [CrossRef]

- Sripa, B.; Kaewkes, S.; Sithithaworn, P.; Mairiang, E.; Laha, T.; Smout, M.; Pairojkul, C.; Bhudhisawasdi, V.; Tesana, S.; Thinkamrop, B.; et al. Liver Fluke Induces Cholangiocarcinoma. PLOS Med. 2007, 4, e201.

- Sripa, B.; Brindley, P.J.; Mulvenna, J.; Laha, T.; Smout, M.J.; Mairiang, E.; Bethony, J.M.; Loukas, A. The Tumorigenic Liver Fluke <em>Opisthorchis Viverrini</Em> – Multiple Pathways to Cancer. Trends Parasitol. 2012, 28, 395–407. [CrossRef]

- Sripa, B.; Tangkawattana, S.; Laha, T.; Kaewkes, S.; Mallory, F.F.; Smith, J.F.; Wilcox, B.A. Toward Integrated Opisthorchiasis Control in Northeast Thailand: The Lawa Project. Acta Trop. 2015, 141, 361–367. [CrossRef]

- HASWELL-ELKINS, M.R.; SATARUG, S.; ELKINS, D.B. Opisthorchis Viverrini Infection in Northeast Thailand and Its Relationship to Cholangiocarcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1992, 7, 538–548. [CrossRef]

- MAIRIANG, E.; ELKINS, D.B.; MAIRIANG, P.; CHAIYAKUM, J.; CHAMADOL, N.; LOAPAIBOON, V.; POSRI, S.; SITHITHAWORN, P.; HASWELL-ELKINS, M. Relationship between Intensity of Opisthorchis Viverrini Infection and Hepatobiliary Disease Detected by Ultrasonography. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1992, 7, 17–21. [CrossRef]

- Pumhirunroj, B.; Aukkanimart, R. LIVER FLUKE-INFECTED CYPRINOID FISH IN NORTHEASTERN THAILAND ( 2016-2017 ). Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2017, 51, 1–7.

- Pinlaor, S.; Onsurathum, S.; Boonmars, T.; Pinlaor, P.; Hongsrichan, N.; Chaidee, A.; Haonon, O.; Limviroj, W.; Tesana, S.; Kaewkes, S.; et al. Distribution and Abundance of Opisthorchis Viverrini Metacercariae in Cyprinid Fish in Northeastern Thailand. Korean J. Parasitol. 2013, 51, 703–710. [CrossRef]

- Suwannatrai, A.T.; Thinkhamrop, K.; Clements, A.C.A.; Kelly, M.; Suwannatrai, K.; Thinkhamrop, B.; Khuntikeo, N.; Gray, D.J.; Wangdi, K. Bayesian Spatial Analysis of Cholangiocarcinoma in Northeast Thailand. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, S.; Ikai, I.; Fujii, H.; Hatano, E.; Shimahara, Y. Surgical Resection of Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: Analysis of Survival and Postoperative Complications. World J. Surg. 2007, 31, 1258–1265. [CrossRef]

- Thinkhamrop, K.; Suwannatrai, A.T.; Chamadol, N.; Khuntikeo, N.; Thinkhamrop, B.; Sarakarn, P.; Gray, D.J.; Wangdi, K.; Clements, A.C.A.; Kelly, M. Spatial Analysis of Hepatobiliary Abnormalities in a Population at High-Risk of Cholangiocarcinoma in Thailand. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16855. [CrossRef]

- Pratumchart, K.; Suwannatrai, K.; Sereewong, C.; Thinkhamrop, K.; Chaiyos, J.; Boonmars, T.; Suwannatrai, A.T. Ecological Niche Model Based on Maximum Entropy for Mapping Distribution of Bithynia Siamensis Goniomphalos, First Intermediate Host Snail of Opisthorchis Viverrini in Thailand. Acta Trop. 2019, 193, 183–191. [CrossRef]

- Suwannatrai, A.T.; Thinkhamrop, K.; Clements, A.C.A.; Kelly, M.; Suwannatrai, K.; Thinkhamrop, B.; Khuntikeo, N.; Gray, D.J.; Wangdi, K. Bayesian Spatial Analysis of Cholangiocarcinoma in Northeast Thailand. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14263. [CrossRef]

- Martviset, P.; Phadungsil, W.; Na-Bangchang, K.; Sungkhabut, W.; Panupornpong, T.; Prathaphan, P.; Torungkitmangmi, N.; Chaimon, S.; Wangboon, C.; Jamklang, M.; et al. Current Prevalence and Geographic Distribution of Helminth Infections in the Parasitic Endemic Areas of Rural Northeastern Thailand. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 448. [CrossRef]

- Littidej, P.; Buasri, N. Built-up Growth Impacts on Digital Elevation Model and Flood Risk Susceptibility Prediction in Muaeng District, Nakhon Ratchasima (Thailand). Water (Switzerland) 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Littidej, P.; Uttha, T.; Pumhirunroj, B. Spatial Predictive Modeling of the Burning of Sugarcane Plots in Northeast Thailand with Selection of Factor Sets Using a GWR Model and Machine Learning Based on an ANN-CA. Symmetry (Basel). 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Prasertsri, N.; Littidej, P. Spatial Environmental Modeling for Wildfire Progression Accelerating Extent Analysis Using Geo-Informatics. Polish J. Environ. Stud. 2020, 29, 3249–3261. [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Charlton, M.; Fotheringham, A.S. Geographically Weighted Regression Using a Non-Euclidean Distance Metric with a Study on London House Price Data. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2011, 7, 92–97. [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Charlton, M.; Harris, P.; Fotheringham, A.S. Geographically Weighted Regression with a Non-Euclidean Distance Metric: A Case Study Using Hedonic House Price Data. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2014, 28, 660–681. [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, A.; Charlton, M. Geographically Geographically Weighted Weighted Regression Regression A Stewart Fotheringham. 2014.

- Hussain, M.A.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Shoaib, M.; Shah, S.U.; Ali, N.; Afzal, Z. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Machine Learning Algorithm Validated by Persistent Scatterer In-SAR Technique. Sensors 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Achour, Y.; Pourghasemi, H.R. How Do Machine Learning Techniques Help in Increasing Accuracy of Landslide Susceptibility Maps? Geosci. Front. 2020, 11, 871–883. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Anbalagan, R. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) in Tehri Reservoir Rim Region, Uttarakhand. J. Geol. Soc. India 2016, 87, 271–286. [CrossRef]

- Tengtrairat, N.; Woo, W.L.; Parathai, P.; Aryupong, C.; Jitsangiam, P.; Rinchumphu, D. Automated Landslide-Risk Prediction Using Web GIS and Machine Learning Models. Sensors (Basel). 2021, 21, 1–32. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Choi, C.; Kim, B.; Kim, J. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Frequency Ratio, Analytic Hierarchy Process, Logistic Regression, and Artificial Neural Network Methods at the Inje Area, Korea. Environ. Earth Sci. 2013, 68, 1443–1464. [CrossRef]

- Tien Bui, D.; Pradhan, B.; Lofman, O.; Revhaug, I. Landslide Susceptibility Assessment in Vietnam Using Support Vector Machines, Decision Tree, and Naïve Bayes Models. Math. Probl. Eng. 2012, 2012, 974638. [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Mandal, K. Modeling and Mapping Landslide Susceptibility Zones Using GIS Based Multivariate Binary Logistic Regression (LR) Model in the Rorachu River Basin of Eastern Sikkim Himalaya, India. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2018, 4, 69–88. [CrossRef]

- Pourghasemi, H.R.; Rahmati, O. Prediction of the Landslide Susceptibility: Which Algorithm, Which Precision? CATENA 2018, 162, 177–192. [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.M.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Pourtaghi, Z.S.; Al-Katheeri, M.M. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Random Forest, Boosted Regression Tree, Classification and Regression Tree, and General Linear Models and Comparison of Their Performance at Wadi Tayyah Basin, Asir Region, Saudi Arabia. Landslides 2016, 13, 839–856. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Guzzetti, F.; Reichenbach, P.; Mondini, A.C.; Peruccacci, S. Optimal Landslide Susceptibility Zonation Based on Multiple Forecasts. Geomorphology 2010, 114, 129–142. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, J. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Based on Random Forest and Boosted Regression Tree Models, and a Comparison of Their Performance. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Sevgen, E.; Kocaman, S.; Nefeslioglu, H.A.; Gokceoglu, C. Photogrammetric Techniques for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping with Logistic Regression ,. Sensors 2019, 19, 3940. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Díaz, P.; Martín-Dorta, N.; Gutiérrez-García, F.J. Construction Labour Measurement in Reinforced Concrete Floating Caissons in Maritime Ports. Civ. Eng. J. 2022, 8, 195–208. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.A.; Chen, Z.; Wang, R.; Shoaib, M. Ps-Insar-Based Validated Landslide Susceptibility Mapping along Karakorum Highway, Pakistan. Remote Sens. 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Taalab, K.; Cheng, T.; Zhang, Y. Mapping Landslide Susceptibility and Types Using Random Forest. Big Earth Data 2018, 2, 159–178. [CrossRef]

- Conoscenti, C.; Ciaccio, M.; Caraballo-Arias, N.A.; Gómez-Gutiérrez, Á.; Rotigliano, E.; Agnesi, V. Assessment of Susceptibility to Earth-Flow Landslide Using Logistic Regression and Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines: A Case of the Belice River Basin (Western Sicily, Italy). Geomorphology 2015, 242, 49–64. [CrossRef]

- Felicísimo, Á.M.; Cuartero, A.; Remondo, J.; Quirós, E. Mapping Landslide Susceptibility with Logistic Regression, Multiple Adaptive Regression Splines, Classification and Regression Trees, and Maximum Entropy Methods: A Comparative Study. Landslides 2013, 10, 175–189. [CrossRef]

- Vorpahl, P.; Elsenbeer, H.; Märker, M.; Schröder, B. How Can Statistical Models Help to Determine Driving Factors of Landslides? Ecol. Modell. 2012, 239, 27–39. [CrossRef]

- Ghasemian, B.; Shahabi, H.; Shirzadi, A.; Al-Ansari, N.; Jaafari, A.; Kress, V.; Renoud, S.; Ramadhan, A.; Geertsema, M. A Robust Deep-Learning Model for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping. Sensors 2022, 22, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Niu, X.; Jiang, S.; Liu, Z. A Comparative Study of Mutual Information-Based Input Variable Selection Strategies for the Displacement Prediction of Seepage-Driven Landslides Using Optimized Support Vector Regression. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2022, 36, 3109–3129. [CrossRef]

- Kalantar, B.; Pradhan, B.; Naghibi, S.A.; Motevalli, A.; Mansor, S. Assessment of the Effects of Training Data Selection on the Landslide Susceptibility Mapping: A Comparison between Support Vector Machine (SVM), Logistic Regression (LR) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN). Geomatics, Nat. Hazards Risk 2018, 9, 49–69. [CrossRef]

- Pham, B.T.; Tien Bui, D.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Indra, P.; Dholakia, M.B. Landslide Susceptibility Assesssment in the Uttarakhand Area (India) Using GIS: A Comparison Study of Prediction Capability of Naïve Bayes, Multilayer Perceptron Neural Networks, and Functional Trees Methods. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2017, 128, 255–273. [CrossRef]

- Pham, B.T.; Pradhan, B.; Tien Bui, D.; Prakash, I.; Dholakia, M.B. A Comparative Study of Different Machine Learning Methods for Landslide Susceptibility Assessment: A Case Study of Uttarakhand Area (India). Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 84, 240–250. [CrossRef]

- Techniques, M.; Mehrabi, M.; Pradhan, B.; Moayedi, H. Optimizing an Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System for Spatial Prediction of Landslide Susceptibility Using Four State-of-the-Art. 2007.

- Dehnavi, A.; Aghdam, I.N.; Pradhan, B.; Morshed Varzandeh, M.H. A New Hybrid Model Using Step-Wise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis (SWARA) Technique and Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) for Regional Landslide Hazard Assessment in Iran. CATENA 2015, 135, 122–148. [CrossRef]

- Aghdam, I.N.; Varzandeh, M.H.M.; Pradhan, B. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using an Ensemble Statistical Index (Wi) and Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) Model at Alborz Mountains (Iran). Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 553. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Anbalagan, R. Landslide Susceptibility Zonation in Part of Tehri Reservoir Region Using Frequency Ratio, Fuzzy Logic and GIS. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 124, 431–448. [CrossRef]

- Charandabi, S.E.; Kamyar, K. Prediction of Cryptocurrency Price Index Using Artificial Neural Networks: A Survey of the Literature. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2021, 6, 17–20. [CrossRef]

- Roshani, M.; Sattari, M.A.; Muhammad Ali, P.J.; Roshani, G.H.; Nazemi, B.; Corniani, E.; Nazemi, E. Application of GMDH Neural Network Technique to Improve Measuring Precision of a Simplified Photon Attenuation Based Two-Phase Flowmeter. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2020, 75, 101804. [CrossRef]

- Moayedi, H.; Abdolreza, O.; Bui, D.T.; Foong, L.K. Spatial Landslide Susceptibility Assessment Based On. Sensors (Switzerland) 2019, 19. [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.T.; Moayedi, H.; Kalantar, B.; Osouli, A.; Pradhan, B.; Nguyen, H.; Rashid, A.S.A. A Novel Swarm Intelligence—Harris Hawks Optimization for Spatial Assessment of Landslide Susceptibility. Sensors (Switzerland) 2019, 19. [CrossRef]

- Arnone, E.; Francipane, A.; Scarbaci, A.; Puglisi, C.; Noto, L. V Effect of Raster Resolution and Polygon-Conversion Algorithm on Landslide Susceptibility Mapping. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 84, 467–481. [CrossRef]

- Aditian, A.; Kubota, T.; Shinohara, Y. Comparison of GIS-Based Landslide Susceptibility Models Using Frequency Ratio, Logistic Regression, and Artificial Neural Network in a Tertiary Region of Ambon, Indonesia. Geomorphology 2018, 318, 101–111. [CrossRef]

- Kornejady, A.; Ownegh, M.; Bahremand, A. Landslide Susceptibility Assessment Using Maximum Entropy Model with Two Different Data Sampling Methods. CATENA 2017, 152, 144–162. [CrossRef]

- Park, N.-W. Using Maximum Entropy Modeling for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping with Multiple Geoenvironmental Data Sets. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 73, 937–949. [CrossRef]

- Dang, V.H.; Hoang, N.D.; Nguyen, L.M.D.; Bui, D.T.; Samui, P. A Novel GIS-Based Random Forest Machine Algorithm for the Spatial Prediction of Shallow Landslide Susceptibility. Forests 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ren, F.; Niu, R. Landslide Susceptibility Assessment Using Object Mapping Units, Decision Tree, and Support Vector Machine Models in the Three Gorges of China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 71, 4725–4738. [CrossRef]

- Merghadi, A.; Yunus, A.P.; Dou, J.; Whiteley, J.; ThaiPham, B.; Bui, D.T.; Avtar, R.; Abderrahmane, B. Machine Learning Methods for Landslide Susceptibility Studies: A Comparative Overview of Algorithm Performance. Earth-Science Rev. 2020, 207, 103225. [CrossRef]

- Sahin, E.K. Comparative Analysis of Gradient Boosting Algorithms for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping. Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 2441–2465. [CrossRef]

- Nohani, E.; Moharrami, M.; Sharafi, S.; Khosravi, K.; Pradhan, B.; Pham, B.T.; Lee, S.; Melesse, A.M. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Different GIS-Based Bivariate Models. Water (Switzerland) 2019, 11, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Pourghasemi, H.R.; Gayen, A.; Panahi, M.; Rezaie, F.; Blaschke, T. Multi-Hazard Probability Assessment and Mapping in Iran. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 692, 556–571. [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Zhang, Q.; Ye, S.; Ren, B. A Novel Hybrid Approach for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Integrating Analytical Hierarchy Process and Normalized Frequency Ratio Methods with the Cloud Model. Geomorphology 2019, 327, 170–187. [CrossRef]

- Suwannahitatorn, P.; Webster, J.; Riley, S.; Mungthin, M.; Donnelly, C.A. Uncooked Fish Consumption among Those at Risk of Opisthorchis Viverrini Infection in Central Thailand. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211540. [CrossRef]

- Sripa, B.; Kaewkes, S.; Intapan, P.M.; Maleewong, W.; Brindley, P.J. Chapter 11 - Food-Borne Trematodiases in Southeast Asia: Epidemiology, Pathology, Clinical Manifestation and Control. In Important Helminth Infections in Southeast Asia: Diversity and Potential for Control and Elimination, Part A; Zhou, X.-N., Bergquist, R., Olveda, R., Utzinger, J.B.T.-A. in P., Eds.; Academic Press, 2010; Vol. 72, pp. 305–350 ISBN 0065-308X.

- Qian, M.-B.; Utzinger, J.; Keiser, J.; Zhou, X.-N. Clonorchiasis. Lancet 2016, 387, 800–810. [CrossRef]

- Brindley, P.J.; Bachini, M.; Ilyas, S.I.; Khan, S.A.; Loukas, A.; Sirica, A.E.; Teh, B.T.; Wongkham, S.; Gores, G.J. Cholangiocarcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- (SKKO), S.N.P.P.H.O. Annual Report 2023; 2023;

- Dao, T.T.H.; Bui, T. Van; Abatih, E.N.; Gabriël, S.; Nguyen, T.T.G.; Huynh, Q.H.; Nguyen, C. Van; Dorny, P. Opisthorchis Viverrini Infections and Associated Risk Factors in a Lowland Area of Binh Dinh Province, Central Vietnam. Acta Trop. 2016, 157, 151–157. [CrossRef]

- Ruantip, S.; Eamudomkarn, C.; Kopolrat, K.Y.; Sithithaworn, J.; Laha, T.; Sithithaworn, P. Analysis of Daily Variation for 3 and for 30 Days of Parasite-Specific IgG in Urine for Diagnosis of Strongyloidiasis by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay. Acta Trop. 2021, 218, 105896. [CrossRef]

- .

- Honjo, S.; Srivatanakul, P.; Sriplung, H.; Kikukawa, H.; Hanai, S.; Uchida, K.; Todoroki, T.; Jedpiyawongse, A.; Kittiwatanachot, P.; Sripa, B.; et al. Genetic and Environmental Determinants of Risk for Cholangiocarcinoma via Opisthorchis Viverrini in a Densely Infested Area in Nakhon Phanom, Northeast Thailand. Int. J. cancer 2005, 117, 854–860. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.-T.; Feng, Y.-J.; Doanh, P.N.; Sayasone, S.; Khieu, V.; Nithikathkul, C.; Qian, M.-B.; Hao, Y.-T.; Lai, Y.-S. Model-Based Spatial-Temporal Mapping of Opisthorchiasis in Endemic Countries of Southeast Asia. Elife 2021, 10, e59755. [CrossRef]

- Reza, M.; Miri, S.; Javidan, R. A Hybrid Data Mining Approach for Intrusion Detection on Imbalanced NSL-KDD Dataset. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2016, 7, 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Ludmila I. Kuncheva Classifier Selection. In Combining Pattern Classifiers; 2004; pp. 189–202 ISBN 9780471660262.

- Ho, T.K. Random Decision Forests. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition; 1995; Vol. 1, pp. 278–282 vol.1. [CrossRef]

- Kleinberg, E.M. Stochastic Discrimination. Ann. Math. Artif. Intell. 1990, 1, 207–239. [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [CrossRef]

- Dang, V.-H.; Dieu, T.B.; Tran, X.-L.; Hoang, N.-D. Enhancing the Accuracy of Rainfall-Induced Landslide Prediction along Mountain Roads with a GIS-Based Random Forest Classifier. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2019, 78, 2835–2849. [CrossRef]

- Choubin, B.; Abdolshahnejad, M.; Moradi, E.; Querol, X.; Mosavi, A.; Shamshirband, S.; Ghamisi, P. Spatial Hazard Assessment of the PM10 Using Machine Learning Models in Barcelona, Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 701, 134474. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Xie, X.; Wang, J.; Pradhan, B.; Hong, H.; Bui, D.T.; Duan, Z.; Ma, J. A Comparative Study of Logistic Model Tree, Random Forest, and Classification and Regression Tree Models for Spatial Prediction of Landslide Susceptibility. CATENA 2017, 151, 147–160. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Xie, X.; Peng, J.; Shahabi, H.; Hong, H.; Bui, D.T.; Duan, Z.; Li, S.; Zhu, A.-X. GIS-Based Landslide Susceptibility Evaluation Using a Novel Hybrid Integration Approach of Bivariate Statistical Based Random Forest Method. CATENA 2018, 164, 135–149. [CrossRef]

- Trigila, A.; Iadanza, C.; Esposito, C.; Scarascia-Mugnozza, G. Comparison of Logistic Regression and Random Forests Techniques for Shallow Landslide Susceptibility Assessment in Giampilieri (NE Sicily, Italy). Geomorphology 2015, 249, 119–136. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Han, J. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery; 2021; ISBN 9780387098227.

- Bonissone, P.; Cadenas, J.M.; Carmen Garrido, M.; Andrés Díaz-Valladares, R. A Fuzzy Random Forest. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2010, 51, 729–747. [CrossRef]

- Forrer, A.; Sayasone, S.; Vounatsou, P.; Vonghachack, Y.; Bouakhasith, D.; Vogt, S.; Glaser, R.; Utzinger, J.; Akkhavong, K.; Odermatt, P. Spatial Distribution of, and Risk Factors for, Opisthorchis Viverrini Infection in Southern Lao PDR. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e1481. [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Jiang, S.; Peng, H.-J. Association between Liver Fluke Infection and Hepatobiliary Pathological Changes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132673. [CrossRef]

- Brunton, L.A.; Alexander, N.; Wint, W.; Ashton, A.; Broughan, J.M. Using Geographically Weighted Regression to Explore the Spatially Heterogeneous Spread of Bovine Tuberculosis in England and Wales. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2017, 31, 339–352. [CrossRef]

- Rujirakul, R.; Ueng-arporn, N.; Kaewpitoon, S.; Loyd, R.J.; Kaewthani, S.; Kaewpitoon, N. GIS-Based Spatial Statistical Analysis of Risk Areas for Liver Flukes in Surin Province of Thailand. 2015, 16, 2323–2326. [CrossRef]

- Brunsdon, C.; Fotheringham, S.; Charlton, M. Geographically Weighted Regression-Modelling Spatial Non-Stationarity. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. D (The Stat. 1998, 47, 431–443.

- Comber, A.; Brunsdon, C.; Charlton, M.; Dong, G.; Harris, R.; Lu, B.; Lü, Y.; Murakami, D.; Nakaya, T.; Wang, Y.; et al. A Route Map for Successful Applications of Geographically Weighted Regression. 2023, 155–178. [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Hu, Y.; Murakami, D.; Brunsdon, C.; Comber, A.; Charlton, M.; Harris, P. High-Performance Solutions of Geographically Weighted Regression in R. Geo-spatial Inf. Sci. 2022, 25, 536–549. [CrossRef]

- Leong, Y.Y.; Yue, J.C. A Modification to Geographically Weighted Regression. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2017, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Isazade, V.; Qasimi, A.B.; Dong, P.; Kaplan, G.; Isazade, E. Integration of Moran’s I, Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR), and Ordinary Least Square (OLS) Models in Spatiotemporal Modeling of COVID-19 Outbreak in Qom and Mazandaran Provinces, Iran. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Düzgün, H.S.; Kemeç, S. Spatial and Geographically Weighted Regression BT - Encyclopedia of GIS. In; Shekhar, S., Xiong, H., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2008; pp. 1073–1077 ISBN 978-0-387-35973-1.

- ESRI Forest-Based Classification and Regression (Spatial Statistics) Available online: https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/latest/tool-reference/spatial-statistics/forestbasedclassificationregression.htm.

| Provinces | Number of people with | Number of people with |

|---|---|---|

| cholangiocarcinoma in 2019 | cholangiocarcinoma in 2020 | |

| Nongkhai | 22 | 37 |

| Buengkarn | 8 | 7 |

| Loei | 54 | 84 |

| Nakhon Phanom | 7 | 10 |

| Udon Thani | 50 | 88 |

| Nongbualumphu | 19 | 12 |

| Sakon Nakhon | 161 | 130 |

| Y(% of OV) | X1(lu) | X2(soil) | X3(road) | X4(water) | X5(stream) | X6(Temp) | X7(ndmi) | X8(ndvi) | X9(savi) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y(% of OV) | 1.000 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| X1 | -0.167 | 1.000 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| X2 | -0.437 | 0.826 | 1.000 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| X3 | -0.189 | 0.992 | 0.813 | 1.000 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| X4 | -0.402 | 0.599 | 0.739 | 0.635 | 1.000 | - | - | - | - | - |

| X5 | -0.226 | 0.985 | 0.838 | 0.984 | 0.612 | 1.000 | - | - | - | - |

| X6 | 0.173 | 0.116 | 0.184 | 0.106 | 0.109 | 0.067 | 1.000 | - | - | - |

| X7 | 0.395 | 0.060 | -0.143 | -0.061 | -0.258 | -0.193 | 0.243 | 1.000 | - | - |

| X8 | 0.082 | 0.092 | 0.227 | 0.095 | 0.134 | 0.062 | 0.969 | 0.171 | 1.000 | - |

| X9 | 0.079 | 0.097 | 0.242 | 0.103 | 0.144 | 0.074 | 0.950 | 0.150 | 0.997 | 1.000 |

| Alternative OLS models for OV-predicted in watershed level |

Independent variables |

Coefficients | t-Stat | p-Valuea |

R2 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y(%OV1) | Intercept | 0.465 | 4.373*** | 0.000*** | 0.524 | |

| X8(ndvi) | -1.534 | -0.878 n/s | 0.226 n/s | |||

| X9(savi) | -6.032 | -2.212 n/s | 0.125 n/s | |||

| Y(%OV2) | Intercept | 4.528 | 1.975*** | 0.000*** | 0.672 | |

| X7(ndmi) | 1.125 | 0.769 *** | 0.044 *** | |||

| X8(ndvi) | -3.116 | -0.890 *** | 0.023 *** | |||

| X9(savi) | -9.852 | -2.326 n/s | 3.024 n/s | |||

| Y(%OV3) | Intercept | 62.042 | 3.031*** | 0.000*** | 0.713 | |

| X5(stream) | -5.047 | -2.068*** | 0.048*** | |||

| X7(ndmi) | 4.246 | 1.875 *** | 0.034 *** | |||

| X8(ndvi) | -9.874 | -2.661*** | 0.021*** | |||

| Y(%OV4) | Intercept | 57.410 | 0.979*** | 0.000*** | 0.681 | |

| X5(stream) | -0.0350 | -3.462*** | 0.031*** | |||

| X6(temp) | 20.210 | 0.734 n/s | 1.263 n/s | |||

| X7(ndmi) | 7.220 | 0.540 *** | 0.044 *** | |||

| X8(ndvi) | -1524.360 | -0.548 *** | 0.026 *** | |||

| X9(savi) | -2732.160 | -2.356 n/s | 0.895 n/s | |||

| Model Out of Bag Errors | Model-1 | Model-2 | Model-3 | Model-4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Trees | 50 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 50 | 100 |

| MSE | 10.203 | 8.98 | 7.298 | 7.074 | 9.075 | 8.93 | 10.203 | 8.98 |

| % of variation explained | -46.689 | -29.111 | -5.511 | -2.267 | -33.117 | -31.003 | -46.689 | -29.111 |

| Top Variable Importance | Model-1 | Model-2 | Model-3 | Model-4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Importance | % | Importance | % | Importance | % | Importance | % | |

| distance to stream lines | 105.09 | 100 | 52.72 | 47 | 34.91 | 37 | 23.18 | 22 | |

| distance to water | 58.75 | 53 | 32.32 | 34 | 39.7 | 37 | |||

| ndmi | 27.89 | 29 | 20.32 | 19 | |||||

| ndvi | 22.79 | 22 | |||||||

| Explanatory Variable Range Diagnostics | Training | Validation | Share | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | Minimum | Maximum | Traininga | Validationb | |

|

Model-1 distance to stream lines |

0.48 |

1055.51 |

133.04 |

610.29 |

1 |

0.45* |

|

Model-2 distance to stream lines |

0.48 | 1055.51 | 594.64 | 610.29 | 1 | 0.01* |

| distance to water resource | 108.65 | 6054.45 | 970.21 | 1604.04 | 1 | 0.11* |

|

Model-3 distance to stream lines |

0.48 | 1055.51 | 195.81 | 527.24 | 1 | 0.31* |

| distance to water resource | 108.65 | 6054.45 | 1319.44 | 1756.75 | 1 | 0.07* |

| ndmi | -0.13 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.20* |

|

Model-4 distance to stream lines |

0.48 | 928.08 | 610.29 | 1055.51 | 0.88* | 0.34* |

| distance to water resource | 108.65 | 6054.45 | 1243.77 | 1604.04 | 1 | 0.06* |

| ndmi | -0.13 | 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.85* | 0.10* |

| ndvi | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.82* | 0.00* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).