Submitted:

28 August 2023

Posted:

29 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. TS theory applied to oxygen-evolution step of PSII

2.2. Relation to ET theory

2.3. Origin of activation entropy and its relation to Marcus theory

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Junge, W. Oxygenic photosynthesis: History, status and perspective. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2019, 52, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, N.; Pantazis, D.A.; Lubitz, W. Current Understanding of the Mechanism of Water Oxidation in Photosystem II and Its Relation to XFEL Data. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2020, 89, 795–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dau, H.; Haumann, M. Eight steps preceding O-O bond formation in oxygenic photosynthesis--a basic reaction cycle of the Photosystem II manganese complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1767, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, R.; Kern, J.; Hattne, J.; Koroidov, S.; Hellmich, J.; Alonso-Mori, R.; Sauter, N.K.; Bergmann, U.; Messinger, J.; Zouni, A.; et al. The Mn4Ca photosynthetic water-oxidation catalyst studied by simultaneous X-ray spectroscopy and crystallography using an X-ray free-electron laser. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2014, 369, 20130324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyring, H. The activated complex in chemical reactions. J. Chem. Phys. 1935, 3, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.G.; Polanyi, M. Some applications of the transition state method to the calculation of reaction velocities, especially in solution. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1935, 31, 875–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, R.G.; Eyring, H. Elementary transition state theory of the Soret and Dufour effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1980, 77, 1728–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, R.A. On the Theory of Oxidation-Reduction Reactions Involving Electron Transfer. I. J. Chem. Phys. 1956, 24, 966–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, R.A.; Sutin, N. Electron transfers in chemistry and biology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1985, 811, 265–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

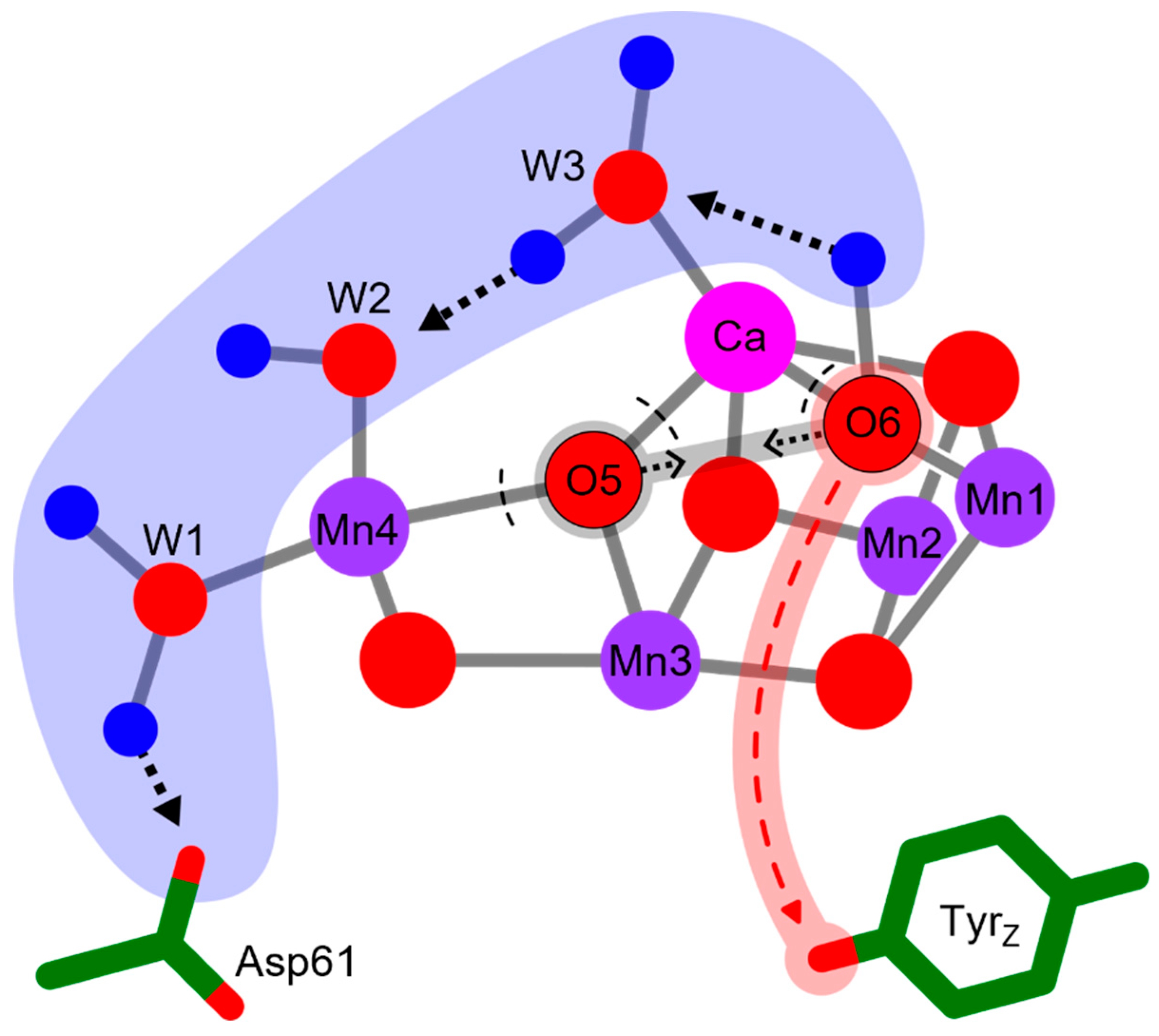

- Greife, P.; Schönborn, M.; Capone, M.; Assunção, R.; Narzi, D.; Guidoni, L.; Dau, H. The electron–proton bottleneck of photosynthetic oxygen evolution. Nature 2023, 617, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, A.; Hussein, R.; Bogacz, I.; Simon, P.S.; Ibrahim, M.; Chatterjee, R.; Doyle, M.D.; Cheah, M.H.; Fransson, T.; Chernev, P.; et al. Structural evidence for intermediates during O2 formation in photosystem II. Nature 2023, 617, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Sekharan, S.; Liu, J.; Batista, V.S.; Tully, J.C.; Yan, E.C.Y. Unusual kinetics of thermal decay of dim-light photoreceptors in vertebrate vision. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014, 111, 10438–10443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, H.; Burnap, R.L. Structural rearrangements preceding dioxygen formation by the water oxidation complex of photosystem II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015, 112, E6139–E6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assunção, R.; Zaharieva, I.; Dau, H. Ammonia as a substrate-water analogue in photosynthetic water oxidation: Influence on activation barrier of the O2-formation step. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2019, 1860, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, B.; Forbush, B.; McGloin, M. Cooperation of charges in photosynthetic O2 evolution - I. A linear four-step mechanism. Photochem. Photobiol. 1970, 11, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, J.; Chatterjee, R.; Young, I.D.; Fuller, F.D.; Lassalle, L.; Ibrahim, M.; Gul, S.; Fransson, T.; Brewster, A.S.; Alonso-Mori, R.; et al. Structures of the intermediates of Kok's photosynthetic water oxidation clock. Nature 2018, 563, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.; Miyazaki, N.; Hamaguchi, T.; Nakajima, Y.; Akita, F.; Yonekura, K.; Shen, J.R. High-resolution cryo-EM structure of photosystem II reveals damage from high-dose electron beams. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, R.; Ibrahim, M.; Bhowmick, A.; Simon, P.S.; Chatterjee, R.; Lassalle, L.; Doyle, M.; Bogacz, I.; Kim, I.S.; Cheah, M.H.; et al. Structural dynamics in the water and proton channels of photosystem II during the S2 to S3 transition. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegbahn, P.E. Mechanisms for proton release during water oxidation in the S2 to S3 and S3 to S4 transitions in photosystem II. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 4849–4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Askerka, M.; Brudvig, G.W.; Batista, V.S. Crystallographic Data Support the Carousel Mechanism of Water Supply to the Oxygen-Evolving Complex of Photosystem II. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 2299–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narzi, D.; Capone, M.; Bovi, D.; Guidoni, L. Evolution from S3 to S4 state of the oxygen evolving complex in Photosystem II monitored by QM/MM dynamics. Chem. Eur. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, M.; Isobe, H.; Shigeta, Y.; Nakajima, T.; Yamaguchi, K. Concerted Mechanism of Water Insertion and O2 Release during the S4 to S0 Transition of the Oxygen-Evolving Complex in Photosystem II. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 6491–6502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capone, M.; Guidoni, L.; Narzi, D. Structural and dynamical characterization of the S-4 state of the Kok-Joliot's cycle by means of QM/MM Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 742, 137111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allgöwer, F.; Gamiz-Hernandez, A.P.; Rutherford, A.W.; Kaila, V.R.I. Molecular Principles of Redox-Coupled Protonation Dynamics in Photosystem II. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 7171–7180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, H.; Shoji, M.; Suzuki, T.; Shen, J.-R.; Yamaguchi, K. Exploring reaction pathways for the structural rearrangements of the Mn cluster induced by water binding in the S3 state of the oxygen evolving complex of photosystem II. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2021, 405, 112905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, C.C.; Keske, J.M.; Warncke, K.; Farid, R.S.; Dutton, P.L. Nature of biological electron transfer. Nature 1992, 355, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerencser, L.; Dau, H. Water oxidation by Photosystem II: H2O−D2O Exchange and the influence of pH support formation of an intermediate by removal of a proton before dioxygen creation. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 10098–10106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klauss, A.; Haumann, M.; Dau, H. Alternating electron and proton transfer steps in photosynthetic water oxidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 16035–16040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losi, A.; Wegener, A.A.; Engelhard, M.; Braslavsky, S.E. Enthalpy−Entropy Compensation in a Photocycle: The K-to-L Transition in Sensory Rhodopsin II from Natronobacterium pharaonis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 1766–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guo, Q.-X. Isokinetic Relationship, Isoequilibrium Relationship, and Enthalpy−Entropy Compensation. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 673–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, A.; Gorski, J. Enthalpy-entropy compensation and cooperativity as thermodynamic epiphenomena of structural flexibility in ligand-receptor interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 2012, 417, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chodera, J.D.; Mobley, D.L. Entropy-enthalpy compensation: Role and ramifications in biomolecular ligand recognition and design. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2013, 42, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

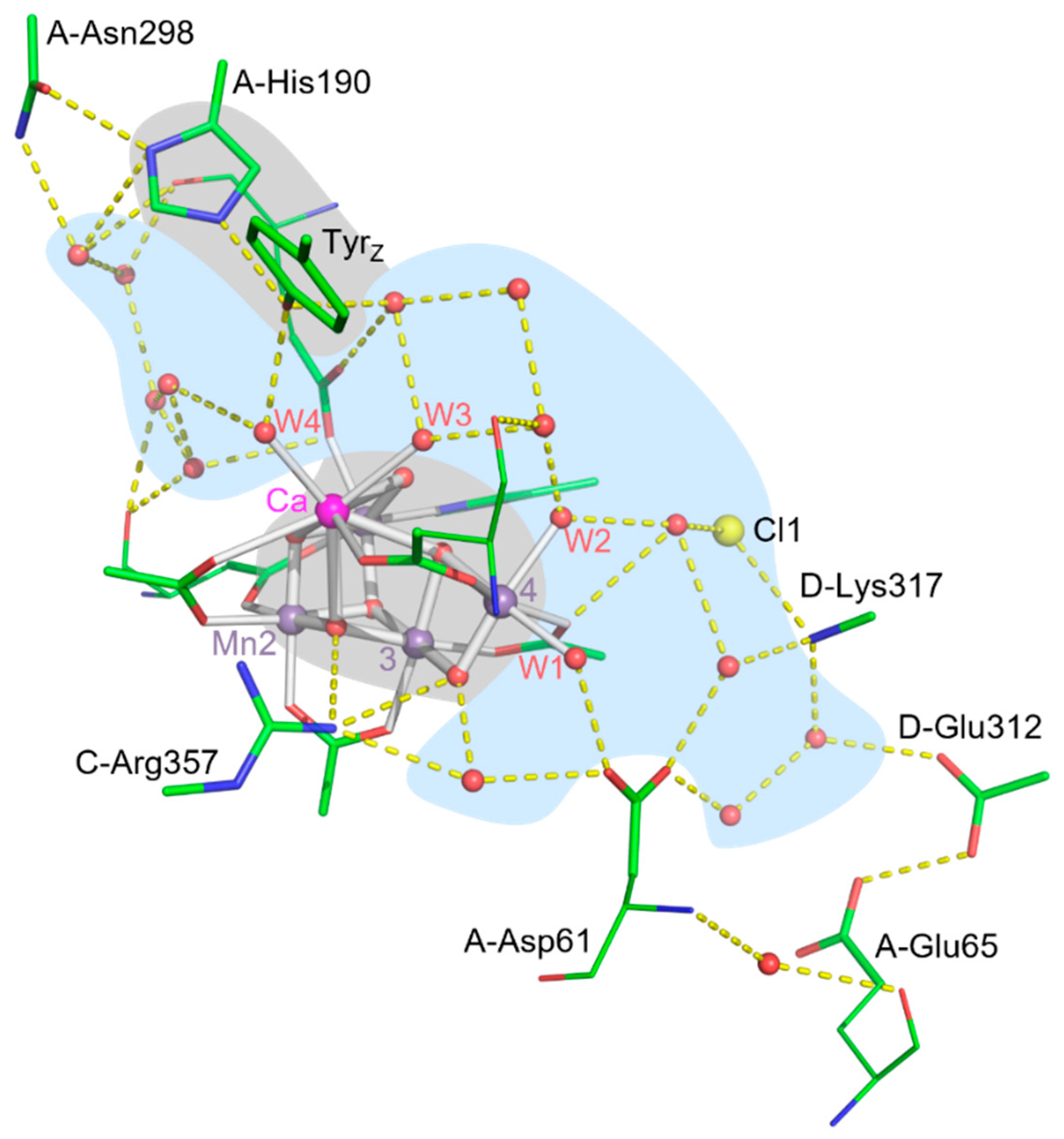

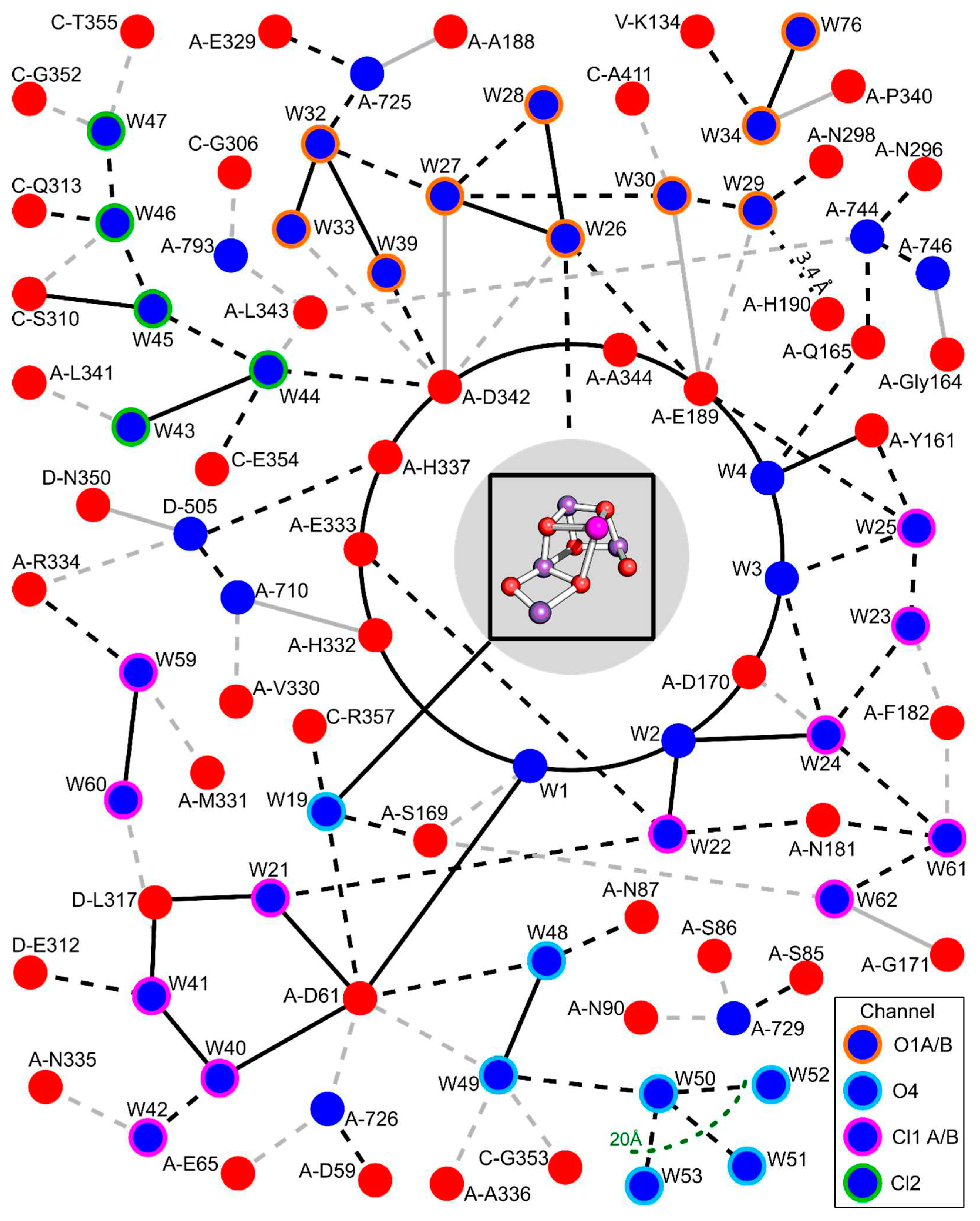

- Bondar, A.-N.; Dau, H. Extended protein/water H-bond networks in photosynthetic water oxidation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1817, 1177–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakashita, N.; Ishikita, H.; Saito, K. Rigidly hydrogen-bonded water molecules facilitate proton transfer in photosystem II. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 15831–15841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, F.; Siemers, M.; Mielack, C.; Bondar, A.N. Dynamics of Long-Distance Hydrogen-Bond Networks in Photosystem II. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 4625–4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

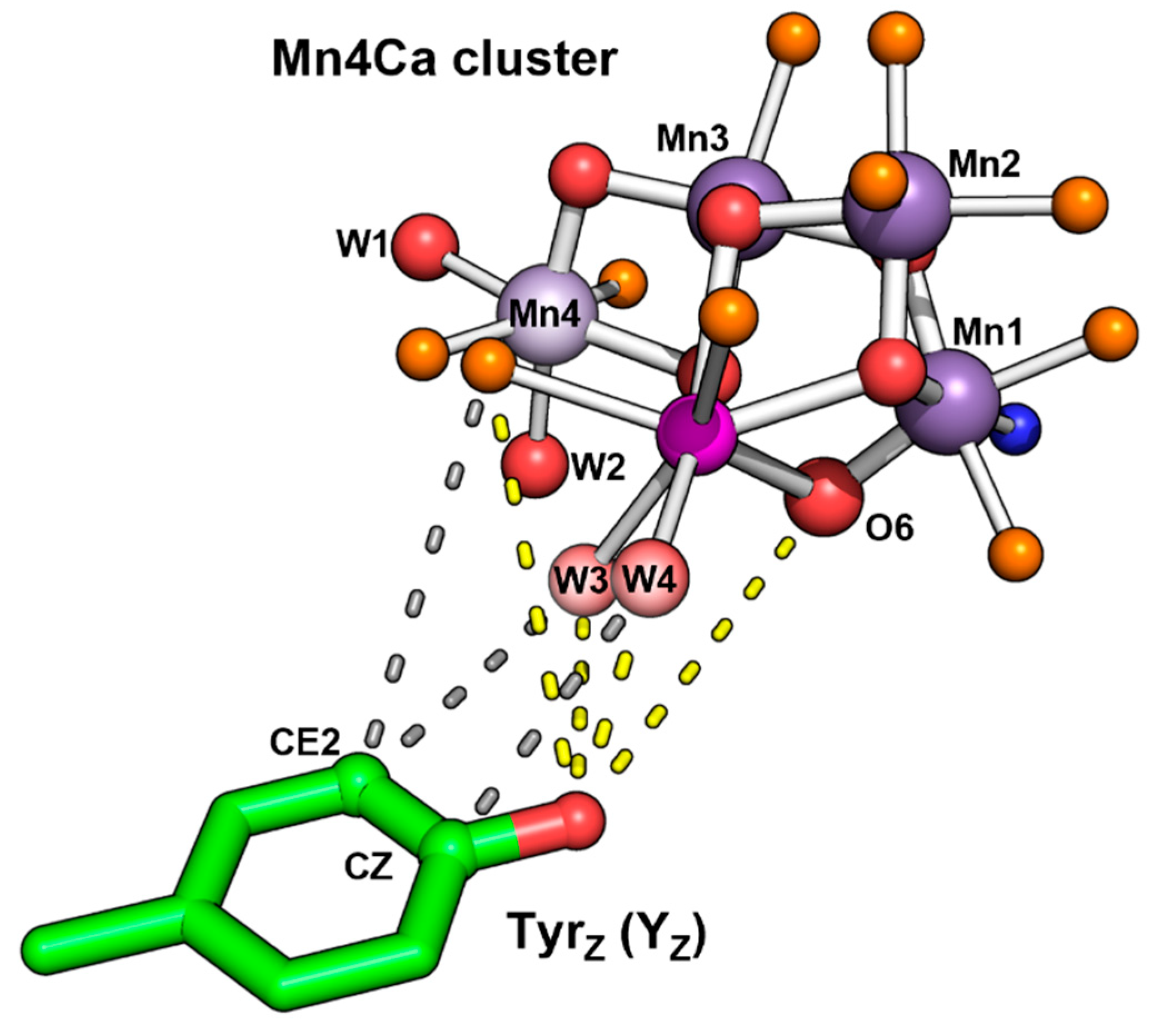

| Atom | Distance to YZO (Å) | |

| 8EZ5 | 6DHO | |

| W4 | 2.7 | 2.9 |

| 3.6 (to CZ Ring) | 3.7 | |

| W3 | 3.9 | 4 |

| 4.1 (to CE2 Ring) | 4.2 | |

| Ca | 4.6 | 4.7 |

| (CA1-Asp170) OD2 | 4.9 (to CE2 Ring) | 5.1 |

| 5.3 | 5.4 | |

| (CA1-Ala344) O | 5.6 | 5.7 |

| O6 | 5.7 | 5.7 |

| (Mn4-Asp170) OD1 | 5.8 (to CE2 Ring) | 5.8 |

| O1 | 6.1 | 6.2 |

| (Mn1-Glu189) OE2 | 6.2 | 6.1 |

| Mn1 | 7.0 | 7.1 |

| Mn4 | 7.4 | 7.4 |

| Mn2 | 7.7 | 7.7 |

| Mn3 | 8.0 | 8.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).