1. Introduction

The sense of taste plays a pivotal role in determining our preferences and responses to various food components, and it is to associated specific organisms and survival needs [

1]. For instance, the bitter taste acts as a protective mechanism against potentially toxic substances, although not all bitter compounds are inherently harmful. Intriguingly, research has revealed the presence of bitter ingredients in diverse sources such as clinical drugs, fruits, and vegetables [

2]. On the other hand, sweeteners have the ability to enhance the perception of sweetness by interacting with specific receptors. However, excessive consumption of sweeteners can have adverse health effects, including the development of type-2 diabetes, heart disease, and other obesity-related conditions [

3].

Taste prediction, a vital area of molecular study within food chemistry, encompasses the analysis and understanding of fundamental senses such as sweetness, bitterness, umami, acidity, and saltiness. It plays a crucial role in identifying and analyzing various factors, including condiments, sweet substitutes, and the underlying causes of bitterness in food [

4].

Machine learning algorithms can be trained on existed datasets of molecular structures and associated taste properties to uncover intricate patterns and relationships. One of the key factors that significantly influences the accuracy and reliability of results is the molecular representation. Most commonly used are sets of physicochemical properties and various fingerprinting methods, which are applied in various of previous studies [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

For example, Cristian Rojas et al. proposed a Quantitative Structure-Taste Relationship (QSTR) expert system to predict the sweetness of molecules based on conformation-independent extended-connectivity fingerprints (ECFPs) and molecular descriptors [

9]. This QSTR model can better understand the relationship between molecular structure and sweetness, which can be used for the design of new sweeteners. Suqing Zheng's team trained machine learning models named e-bitter and e-sweet based on ECFPs and 2-D Dragon descriptors to predict sweeteners and bitterants, respectively [

10,

11]. Further, Rudraksh Tuwani et al. combined more than five kinds of fingerprints and proposed taste predicting system named Bittersweet in 2019 [

12]. In 2022, Weichen Bo et al established a regression-based model that can predict the structure-taste relationship. They used trained deep learning algorithms based on neural networks based on RDKit Fingerprints, molecular descriptors and molecular images respectively [

13].

Recently, advancements in deep learning have further enhanced the power and flexibility of molecular representations. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and graph neural networks (GNNs), have been extensively utilized in diverse applications like drug target interaction prediction [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], molecular property prediction [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23] and genetic biology [

24,

25]. However, the comparison of performance of deep learning in taste prediction is lacking. Given the transformative impact of deep learning across multiple domains, there is a promising potential for its application in advancing the realm of in silico taste prediction. This data-centric methodology possesses the capability to complement empirical assays and yield invaluable insights into the molecular factors dictating various taste perceptions.

In this manuscript, we present a comprehensive investigation into the performance of established and recently proposed molecular feature representations in the context of taste prediction. The research primarily focuses on evaluating the efficacy of various molecular feature representations, with the aim of pinpointing the most suitable neural network architecture that can provide improved accuracy and versatility in the context of datasets centered around small molecules. Through this endeavor, we hope to provide valuable insights into the extent to which these representations encapsulate taste-related details and their suitability for different taste prediction tasks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data preparation

The dataset used in this study is sourced from ChemTastesDB [

4], an extensive database comprising 2,944 organic and inorganic tastants. The dataset includes essential information such as the name, PubChem CID, CAS registry number, canonical SMILES, taste category, and reference literature, providing a comprehensive foundation for our research. These tastants are classified into nine categories, encompassing five basic taste types (sweet, bitter, sour, umami, and salty) and four additional categories (tasteless, non-sweet, multi-taste, and miscellaneous). Specifically, the dataset consists of 977 sweet molecules, 1,183 bitter molecules, 98 umami molecules, 38 sour molecules, 12 salty molecules, 113 multi-taste molecules, 203 tasteless molecules, 233 non-sweet molecules, and 87 miscellaneous molecules.

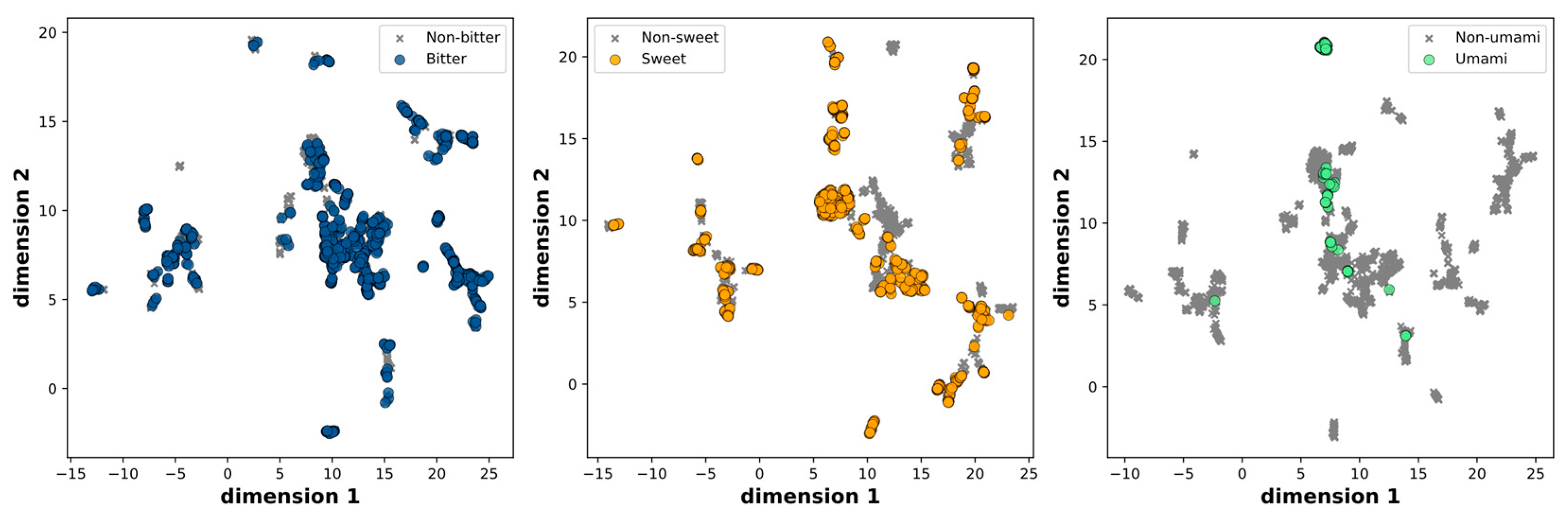

To ensure data quality and avoid redundancies, we initially excluded the multi-taste and miscellaneous molecules, resulting in a dataset of 2,744 molecules. Subsequently, we removed duplicate entries, resulting in a final dataset of 2,601 molecules. These molecules were further classified into three categories based on their taste characteristics: sweet and non-sweet, bitter and non-bitter, and fresh and non-fresh. The distribution across these categories is as follows: 906 sweet and 1,695 non-sweet molecules, 1,126 bitter and 1,475 non-bitter molecules, and 98 umami and 2,503 non-umami molecules, respectively. The chemical space was visualized by evaluating molecular similarity and diversity using UMAP, which compressed the 166-dimensional binary vectors in the MACCS keys into a 2D representation. This mapping effectively portrays the distribution of positive and negative samples, both of which are uniformly spread within the chemical space.

To conduct our analysis, we randomly split the dataset into a training set, validation set, and test set, following a ratio of 7:1:2, ensuring that the distribution of molecules across the different taste categories remained representative in each subset.

Table 1.

The sweet, bitter and umami data sets used in this study.

Table 1.

The sweet, bitter and umami data sets used in this study.

| Category |

Training |

Validation |

Test |

Total |

| Sweet |

637 |

91 |

178 |

906 |

| Nonsweet |

1184 |

169 |

342 |

1695 |

| Bitter |

769 |

118 |

239 |

1126 |

| Nonbitter |

1052 |

142 |

281 |

1475 |

| Umami |

71 |

8 |

19 |

98 |

| Nonumami |

1750 |

252 |

501 |

2503 |

Figure 1.

Scatter plot of the UMAP dimensions. Molecules are colored on the basis of bitter, sweet and umami.

Figure 1.

Scatter plot of the UMAP dimensions. Molecules are colored on the basis of bitter, sweet and umami.

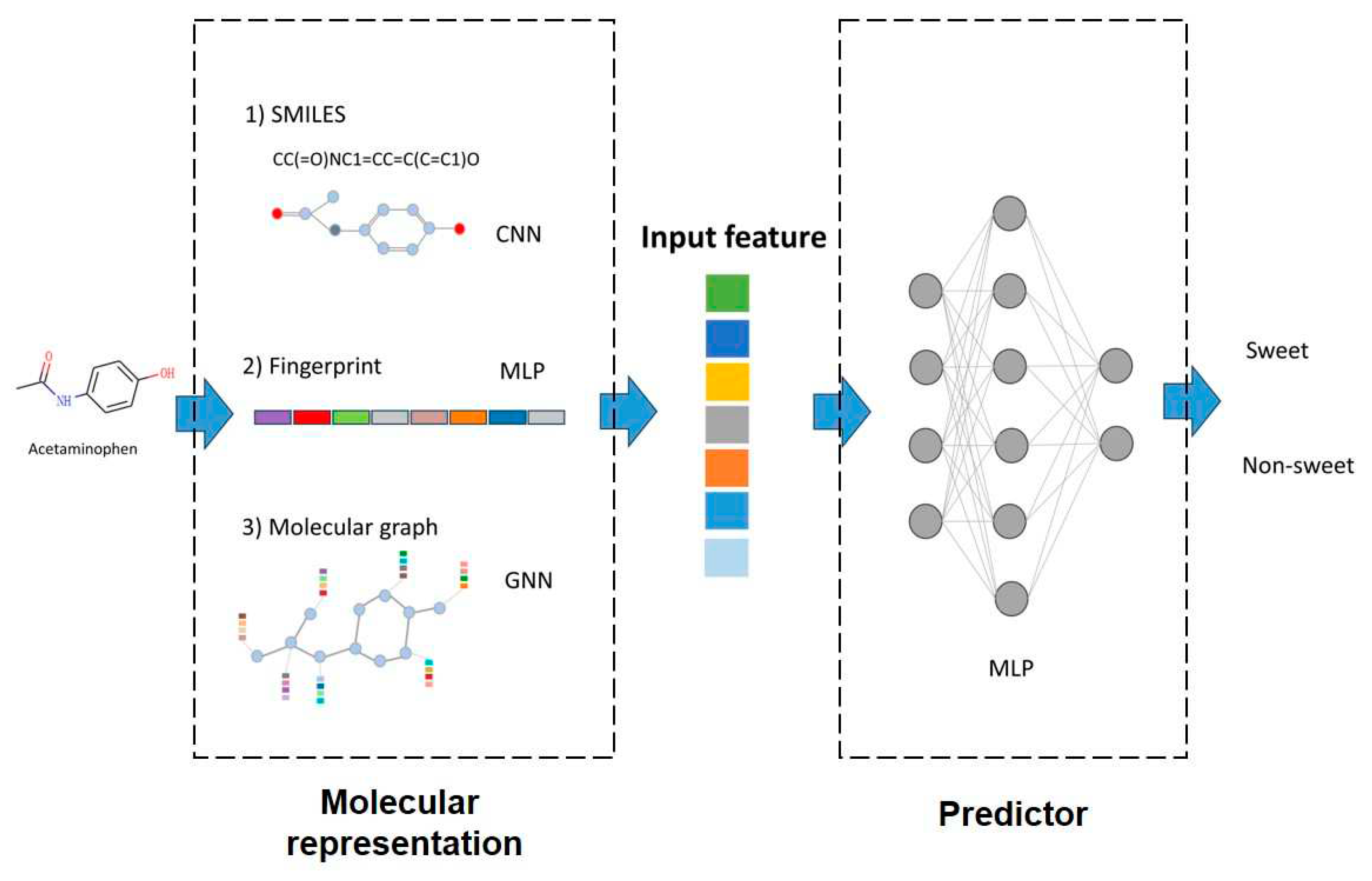

2.2. Molecular representation

Fingerprints, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), and Graph Neural Networks (GNN) are most widely used molecular representation strategies in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) studies [

26]. These methods have indeed demonstrated their effectiveness in various molecular modeling tasks. In this study, we considered choose these methods of these strategies, and evaluate their applicability to the taste prediction tasks. The implementation is assisted by DeepPurpose package, which is a molecular modeling and prediction toolkit integrating numerous molecular representation methods [

17]. The inputs, outputs and model interpretation are summarized in

Figure 2.

2.2.1. Fingerprint

Molecular fingerprints encode structural patterns of molecules into binary vector as the input of followed predictor. Six distinct molecular fingerprints or descriptors were used for comparison with deep-learning based representation. These molecular representations capture different aspects of chemical structures, which are briefly described as following:

- (1)

Morgan fingerprint [

27]: A circular fingerprint encoding structural information by considering substructures at different radii around each atom.

- (2)

PubChem fingerprint [

28]: A binary fingerprint derived from the PubChem Compound database, representing molecular structural features based on predefined chemical substructures.

- (3)

Daylight fingerprint: A descriptor developed by the Daylight Chemical Information Systems, encoding chemical features by identifying fragments and substructures within a molecule.

- (4)

RDKit fingerprint: A fingerprinting method integrated by RDKit package. It is a dictionary with one entry per bit set in the fingerprint, the keys are the bit IDs, the values are tuples of tuples containing bond indices.

- (5)

ESPF fingerprint [

29]: An explainable substructure partition fingerprint capturing extended connectivity patterns within a molecule, representing the presence of specific atom types and their surrounding environments.

- (6)

ErG fingerprint [

30]: A novel fingerprinting method, which is presented that uses pharmacophore-type node descriptions to encode the relevant molecular properties.

2.2.2. Convolutional neural network

Convolutional neural network (CNN) based molecular embedding take molecular SMILES strings as input. These strings are treated similarly to natural language, being converted into one-hot encoding, after which convolutional layers are utilized to generate numerical representations. Three kinds of models were used for comparison, which are briefly described as following:

The CNN model takes the Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System(SMILES), a notation system used to represent the structure of a molecule using ASCII characters, as input, which is previously used in drug-target prediction [

32]. One-hot strategy is used for transforming the strings into two-dimensional array. Three one-way convolutional layers followed by max pooling layers to extract meaningful features from the input SMILES string. The architecture includes ReLU activation functions to introduce non-linearity in the neural network so as to fit more complex data distributions. We have carefully chosen 32, 64 and 96 as the number of filters; 4, 6, 8 as the kernel sizes; 1 as the stride as hyperparameters to optimize performance.

- (2)

The CNN_LSTM model incorporates LSTM layers following the CNN layers. The LSTM layer is a widely utilized recurrent neural network structure that effectively captures long sequence dependencies. In contrast to regular RNNs, LSTM employs forget gate, input gate, and output gate mechanisms, enabling selective retention and omission of input and historical information. Consequently, it excels in modeling lengthy sequences by preserving essential information. In this model, bidirectional LSTM layers are employed with the parameter bidirectional=True. Additionally, the model includes two LSTM units with num_layers=2. By leveraging bidirectional LSTM, the model can encode contextual information and comprehend semantic dependencies within the input.

- (3)

The CNN_GRU model merges the CNN and GRU architectures. The CNN component utilizes one-dimensional convolution to extract relevant features from the sequence, while the GRU component captures long-term dependencies within the sequence. Specifically, the GRU consists of two hidden layers, each containing 64 hidden units. By adjusting the parameters, we configure it to be a bidirectional GRU. Compared to LSTM, GRU has a simpler structure, featuring only an update gate and a reset gate. The reset gate enables control over the retention of past states, while the update gate governs the extent to which the new state replicates the old state.

2.2.3. Graph neural networks

In this study, we employ five distinct graph neural network (GNN) models integrated with Life [

34] and DeepPurpose for comparative analysis. GNN models collectively treat molecules as graph data and extract information from the molecular structure using diverse methodologies. Here's a brief description of each approach:

The GCN model utilizes graph convolutional neural networks (GCN) to extract features. Initially, the input SMILES strings are transformed into molecular graphs, which is a graphical representation of molecule where atoms are represented as nodes and bonds between atoms are represented as edges. From these graphs, features are extracted with GCN. The model comprises three GCN layers, each consisting of 64 hidden units. To ensure stable training, residual connection layers and batch normalization layers are incorporated. Following the three GCN layers, aggregation layers are employed to consolidate node features into graph-level features. Lastly, fully connected layers are used to map the features into a 256-dimensional space.

- (2)

NeuralFP is a variation of GCN that introduces multiple layers of message passing to capture higher-order neighbor information of nodes. It takes into account both 'left neighbors' and 'right neighbors' in two directions during the message passing process. Following each layer of the graph neural network, batch normalization layers are applied to accelerate model convergence and enhance its stability. Various parameter configurations were explored. To avoid excessive model complexity while considering left and right neighbors of nodes, we set the maximum degree to 10. The dimension of graph features is set to 128, influencing the representation of the graph. Additionally, the activation function tanh is employed to enhance the model's non-linear capabilities. By appropriately setting these parameters, effective optimization of the model can be achieved.

- (3)

The GIN-AttrMasking model utilizes graph isomorphic networks (GIN) as its underlying architecture. Initially, node features and edge features are embedded. Subsequently, five GIN layers are applied, with each layer comprising two fully connected layers activated by ReLU functions. Following this, 300-dimensional embeddings are assigned to different edge types. A normalization layer is then introduced, and average pooling is performed on the nodes to obtain the graph's overall representation. To mitigate overfitting, a dropout rate of 0.1 is applied between the fully connected layers.

- (4)

The GIN-ContextPred model is similar to GIN-AttrMasking model. In the GIN layers, the central node's representation is concatenated with the representations of its neighboring nodes. This incorporation of contextual information allows the model to capture a more comprehensive representation, enhancing its ability to learn node representations effectively.

- (5)

AttentiveFP is a graph neural network enhanced with an attention mechanism. It first obtains initial context representations of nodes and edges through the GetContext layer. Internally, it uses an Attentive GRU module that performs weighted summation of edge representations based on attention scores to update the context node representations. The subsequent GNNLayer is the basic layer for message passing and node representation updating. It also uses Attentive GRU internally. Finally, the AttentiveFP readout module, which contains two GlobalPool layers with LeakyReLU activation functions, extracts graph-level representations from the node representations.

2.3. Predictor

After feature representation, the molecules are embedded into vectors, a predictor is used for classification. Commonly used classifiers such as multilayer perceptron (MLP) random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM) and naive Bayes are also compared, of which results are summarized in

Tables S1–S3. Since MLP are almost ranked as top, and it can be seamless joint with CNN and GNN molecular embedders, MLP is taken as the unitive predictor in the following procedures.

In the MLP predictor, dropout layers are then incorporated into the model, randomly deactivating some neurons with a dropout rate of 0.1. This is done to prevent overfitting and enhance the model's generalization capabilities. Following the Dropout layer, a fully connected layer called the predictor is added, consisting of two linear layers. The first layer transforms the 256-dimensional features into 512 dimensions, while the second layer further transforms them into the output layer. The output consists of the probabilities indicating whether a molecule possesses the specific taste or not.

Binary cross-entropy is employed as the loss function to calculate the error between the predicted probability and the true label. The Adam optimization algorithm is utilized to optimize the model parameters which adjusts the learning rate based on the historical and current gradients of the parameters. During the training process, the classifier is initially constructed by encoding the molecules with an initial learning rate of 0.001 and optimized using the Adam optimizer. The training consists of 20 epochs, with each epoch updating the parameters using a batch size of 64 from the training set. The model's performance is evaluated by monitoring indicators on the validation set to save the optimal model.

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation metrics

The performance of the models was assessed using multiple evaluation metrics, including accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, F1 score, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), and area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC). Each metric provides valuable insights into different aspects of the model's performance.

Precision measures the proportion of predicted positive samples that actually belong to the positive class. It quantifies the model's ability to accurately identify positive compounds. Sensitivity, represents the true positive rate, indicating the number of positive compounds correctly predicted as positive. Specificity indicates the number of negative compounds correctly predicted as negative. It evaluates the model's ability to correctly identify negative compounds. F1 score combines precision and sensitivity, providing a balanced measure of the model's performance. It is especially valuable for evaluating classification models and considering the trade-off between false positives and false negatives.

AUROC evaluates the overall discriminative power and balanced prediction performance of the model. Additionally, auxiliary indicators such as accuracy (ACC), AUPRC, and F1 score were employed to provide supplementary information. AUPRC, similar to AUROC, serves as a balanced prediction evaluation metric, particularly in scenarios with highly imbalanced data. It is particularly effective in assessing models' performance when dealing with imbalanced datasets.

The calculation formulas for the aforementioned metrics are as follows:

Here, TP represents true positives, TN represents true negatives, FP represents false positives, and FN represents false negatives.

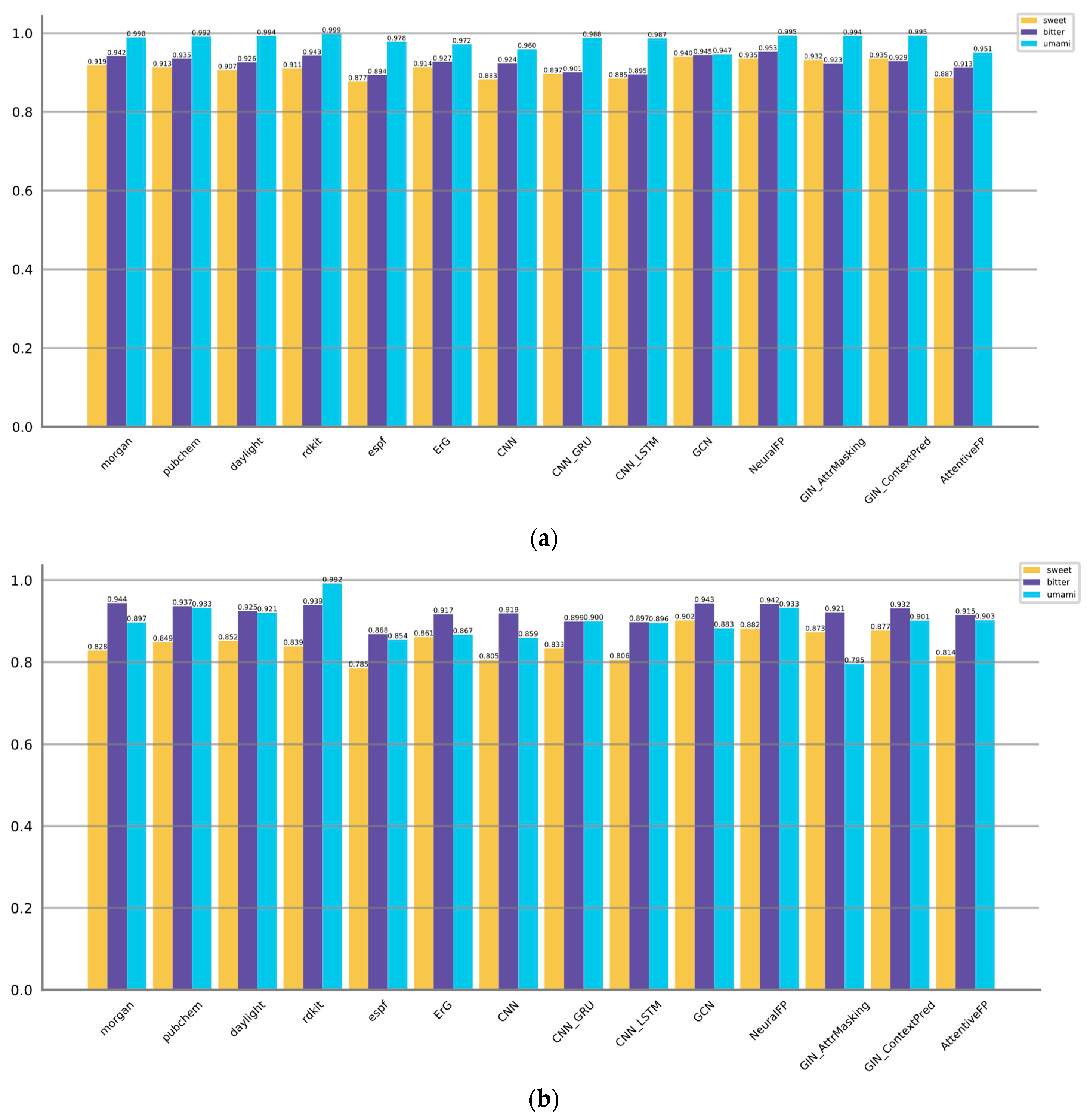

3.2. Comparison of model performance

First, we evaluated the performance of the three types of 14 representation models on predicting the molecular tastes. The results are summarized in

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4.

Figure 3 displayed the AUROC and AUPRC values. Metrics of model complexity are summarized in

Table S4. Metrics of training stages are provided in

Tables S5–S7.

For predicting sweet taste, the GNN-based models (GCN, NeuralFP) and fingerprint-based models (Morgan, PubChem, ErG) exhibit better performance metrics compared to the CNN-based models. Notably, GCN and NeuralFP stand out by achieving high accuracies of 0.869 and 0.896, respectively. Moreover, these models showcase great F1 scores of 0.813 and 0.812, underscoring their efficacy in accurately predicting the sweetness of molecules. Furthermore, these models showcase satisfactory precision, sensitivity, and specificity, suggesting a balanced ability to correctly identify both positive and negative samples. It can also be proved by AUROC and AUPRC values, GCN and NeuralFP are also listed at Top 2.

When it comes to predicting bitter taste, both GNN-based models (GCN, NeuralFP) and fingerprint-based models (Morgan, PubChem, RDKit) consistently outperform the CNN-based models. However, it is important to note that the GNN-based models do not have a significant advantage over the fingerprint-based models in predicting bitter molecules. NeuralFP remains the top performer GNN category, achieving the highest accuracy of 0.896 and F1 score of 0.885. On the other hand, the fingerprint-based models, specifically Pubchem and RDKit, achieve comparable results. Pubchem achieves an accuracy of 0.879 and an F1 score of 0.865, while RDKit achieves an accuracy of 0.869 and an F1 score of 0.857. AUROC and AUPRC values of NeuralFP, GCN, Morgan, PubChem and RDKit are also listed at Top 5. These results suggest that these models achieve a strong precision-recall trade-off and perform well across various threshold levels. This implies that these models are effective in accurately predicting the target outcomes while achieving a balance between precision and recall.

Regarding the umami taste, the majority of methods exhibit satisfactory performance with accuracy levels generally surpassing 0.97, while the F1 scores typically exceed 0.70. This may be attributed to the relatively simpler nature of the prediction task compared to the aforementioned ones. Pubchem, AttentiveFP, GCN, Morgan, ErG, and CNN_GRU exhibit slightly superior performance compared to the other methods, as they achieve higher accuracies and F1 scores. The notably high precision and specificity values suggest that these models have a low rate of false positives, which could potentially be influenced by the presence of an imbalance in the training data.

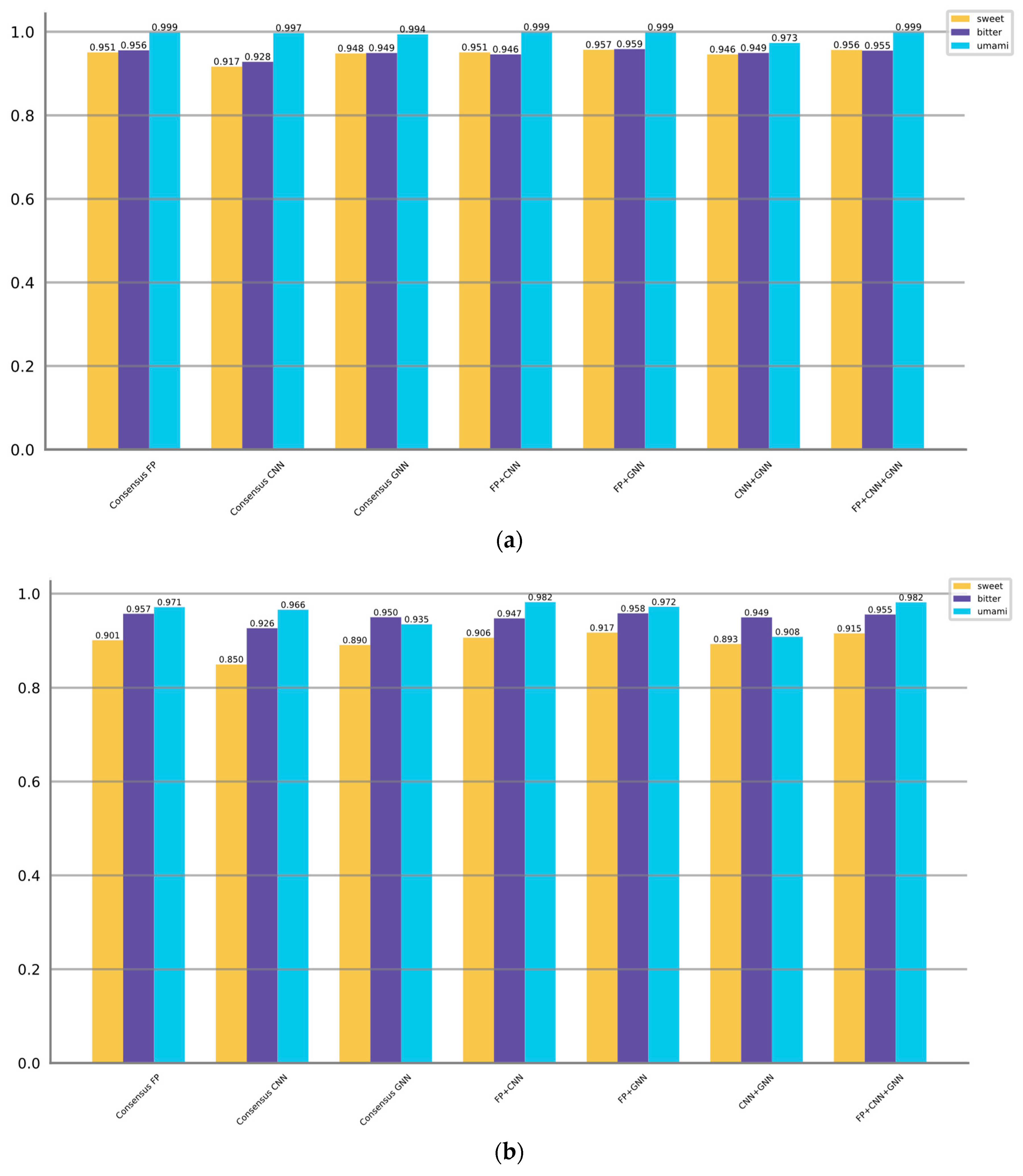

3.3. Voting/consensus model performance

Following that, we proceed with a voting/consensus strategy to investigate the potential enhancement in taste prediction performance through consensus. In this approach, we utilize the average predicting probabilities obtained from multiple models as the final decision, referred to as the "Ensemble score". Various types of consensus approaches are employed, including:

(1) Consensus FP: The ensemble score is obtained by voting from 6 molecular fingerprint methods.

(2) Consensus CNN: The ensemble score is obtained by voting from 3 CNN methods.

(3) Consensus GNN: The ensemble score is obtained by voting from 5 GNN methods.

(4) FP + CNN: This approach combines the top 2 molecular fingerprint methods and the top 2 CNN methods based on their best F1 scores.

(5) FP + GNN: This approach combines the top 2 molecular fingerprint methods and the top 2 GNN methods based on their best F1 scores.

(6) CNN + GNN: This approach combines the top 2 CNN methods and the top 2 GNN methods based on their best F1 scores.

(7) FP + CNN + GNN: This approach combines the top 2 molecular fingerprint methods, the top 2 CNN methods, and the top 2 GNN methods based on their best F1 scores.

In the above descriptions, "top x" refers to selecting the x models with the best F1 scores. The evaluating results of the ensemble approaches are presented in

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7. Additionally,

Figure 4 display the AUROC and AUPRC values corresponding to the different ensemble strategies.

When predicting sweet taste, Consensus FP, Consensus CNN, and Consensus GNN demonstrate superior performance compared to their individual models within the fingerprint, CNN, and GNN categories, as indicated by higher F1 scores, AUROC values, and AUPRC values. The enhanced performance can be attributed to various factors inherent in the consensus strategy such as combining diverse information, mitigating individual model biases, robustly handling variability, and aggregating complementary information. Moreover, the consensus models that combine multiple categories (FP + GNN, FP + CNN + GNN) can exhibit superior performance compared to the consensus model within a single category. However, the CNN + GNN and FP + CNN combinations are not as good as Consensus GNN and Consensus FP, which takes into account the initially poor performance of the CNN-based models. Among all the models, the FP + GNN model demonstrates superior performance in predicting sweet taste with optimal F1, AUROC, and AUPRC scores of 0.852, 0.957, and 0.917, respectively.

The same trend persists when predicting bitter taste, where the FP + GNN model achieves the highest F1 (0.882), AUROC (0.959) and AUPRC (0.958), followed by FP + CNN + GNN. However, when it comes to umami taste prediction, the performance among models is relatively comparable. Consensus models show either no improvement or only slight improvements.

Based on the aforementioned comparisons, we can deduce that incorporating global chemical information through molecular fingerprints, which capture molecular composition, along with topological information obtained from graph structures, enables more comprehensive feature learning. This comprehensive feature learning leads to improved performance in taste prediction tasks.

3.4. In-silicon compound taste database

As application of molecular taste prediction, in-silico compound taste database is built based on the FP + GNN model, which performs best in the test tasks. In order to provide a comprehensive collection of molecular structures associated with various tastes, FooDB (

https://foodb.ca/downloads) as employed to access a vast array of compound structures. Within this website lies a rich repository of chemical information on food components, facilitating the exploration of the molecular basis of taste perception by researchers.

The prediction process encompassed the conversion of the molecular structures obtained from the database into appropriate input representations for FP + GNN model. The predicted compounds with taste characteristics, namely sweet, bitter, and umami are collected. We believe the result will facilitate to find potential additives, determine consumer preferences and/or enhance the flavor of food product. This in-silicon database is available in the

Tables S8–S10 of the Supplementary Materials.

4. Discussion

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive comparison of various molecular representation methods for three taste prediction tasks. The primary objective was to ascertain the applicability of deep learning-driven molecular representation techniques and to identify the optimal approaches for addressing taste prediction tasks, an aspect that has been notably absent in previous research endeavor. To achieve this, we meticulously examined the performance of various methods across different taste categories and employed a robust set of metrics to gauge their effectiveness.

To summarize, umami taste prediction is relatively straightforward as most methods perform similarly well overall. However, when it comes to sweet and bitter prediction, the top-performing methods typically fall within the GNN category. This observation suggests that the graph structure built from atoms and bonds effectively captures the key molecular characteristics associated with taste. Furthermore, the success of GNN-based models in taste prediction implies that specific molecular features encoded in the graph structure, such as functional groups, aromatic systems, or spatial arrangements, have a strong influence on the perception of sweetness and bitterness.

Consensus model of FP + GNN outperforms other consensus models indicates the complementary strengths of the two different representation approaches: GNN and molecular fingerprints. The GNN models excel in capturing the inherent spatial and connectivity information of molecules by considering the relationships between atoms and their neighbors in the molecular graph. This allows them to learn and represent complex structural patterns that are crucial for taste prediction. On the other hand, molecular fingerprints provide a concise representation of the overall molecular composition, encoding key structural features and substructures. They are efficient in capturing global molecular characteristics and can be useful in encoding higher-level properties related to taste perception.

By combining the strengths of GNN and molecular fingerprints through the consensus model, the predictive model can leverage both the fine-grained structural details learned by GNN and the overall molecular features captured by fingerprints. GNNs excel at capturing fine-grained structural details of molecules by recursively aggregating information from neighboring atoms and bonds. This makes GNNs particularly effective at learning local patterns, spatial relationships, and molecular interactions that contribute to the overall behavior of the molecule. Molecular fingerprints are compact binary or numerical representations of molecules that encode information about their chemical structure. They capture global molecular features, such as presence/absence of specific substructures or chemical properties. Molecular fingerprints are efficient for representing overall molecular characteristics. By combining both representations, the consensus model can capture both fine-grained structural information and global molecular features, leading to a more comprehensive representation of the molecule. This hybrid approach enables a more comprehensive understanding of molecular attributes related to taste, resulting in improved predictive performance. The utilization of this voting/consensus methodology presents a source of inspiration for other predictive modeling tasks in the realm of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR). In scenarios where diverse molecular facets contribute in a synergistic manner, this approach has the potential to enhance model performance and facilitate well-informed decision-making. This is particularly suggested when a solitary model fails to yield a satisfactory prediction.

Ultimately, we hope our study not only to contribute to the understanding of taste prediction within the realm of molecular representation but also to offer valuable insights into the broader landscape of predictive modeling in the field of food science.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Tables S1-S3: Performance metrics of different classifier with Pubchem fingerprint for sweet, bitter and umami taste, respectively; Table S4: Complexity of the utilized models; Tables S5-S7: Performance on training set of 14 models for sweet, bitter and umami taste; Tables S8-S10: In-silicon molecular database of sweet, bitter and umami taste, respectively.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.J., W.P and L.F.; methodology, Y.S.; formal analysis: Y.S.; investigation: L.F.; resources: H.J. and Y.S.; data curation: Y.S., S.C., J.T.; writing—original draft preparation: Y.S.; writing—review and editing, H.J., W.P. and L.F; visualization: Y.S.; supervision: H.J. and LF; project administration, H.J.

Funding

This work is financially supported by Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (Grant No. RCBS20210609103157070).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all members of the group for their encouragement and support of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chandrashekar, J.; Hoon, M.A.; Ryba, N.J.P.; Zuker, C.S. The Receptors and Cells for Mammalian Taste. Nature 2006, 444, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewnowski, A.; Gomez-Carneros, C. Bitter Taste, Phytonutrients, and the Consumer: A Review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 1424–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.J.; Segal, M.S.; Sautin, Y.; Nakagawa, T.; Feig, D.I.; Kang, D.-H.; Gersch, M.S.; Benner, S.; Sánchez-Lozada, L.G. Potential Role of Sugar (Fructose) in the Epidemic of Hypertension, Obesity and the Metabolic Syndrome, Diabetes, Kidney Disease, and Cardiovascular Disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 86, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, C.; Ballabio, D.; Pacheco Sarmiento, K.; Pacheco Jaramillo, E.; Mendoza, M.; García, F. ChemTastesDB: A Curated Database of Molecular Tastants. Food Chemistry: Molecular Sciences 2022, 4, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, P.; Preissner, R. BitterSweetForest: A Random Forest Based Binary Classifier to Predict Bitterness and Sweetness of Chemical Compounds. Front. Chem. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, M.; Sharma, A.; Chilwal, A.S.; Kumari, S.; Kumar, A.; Bagler, G. Machine Learning Models to Predict Sweetness of Molecules. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 152, 106441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, F.; Preissner, R.; Banerjee, P. VirtualTaste: A Web Server for the Prediction of Organoleptic Properties of Chemical Compounds. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W679–W684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Chang, W.; Xu, W.; Xu, Y.; Lin, F. E-Sweet: A Machine-Learning Based Platform for the Prediction of Sweetener and Its Relative Sweetness. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, C.; Todeschini, R.; Ballabio, D.; Mauri, A.; Consonni, V.; Tripaldi, P.; Grisoni, F. A QSTR-Based Expert System to Predict Sweetness of Molecules. Front. Chem. 2017, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Jiang, M.; Zhao, C.; Zhu, R.; Hu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Lin, F. E-Bitter: Bitterant Prediction by the Consensus Voting From the Machine-Learning Methods. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Chang, W.; Xu, W.; Xu, Y.; Lin, F. E-Sweet: A Machine-Learning Based Platform for the Prediction of Sweetener and Its Relative Sweetness. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuwani, R.; Wadhwa, S.; Bagler, G. BitterSweet: Building Machine Learning Models for Predicting the Bitter and Sweet Taste of Small Molecules. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bo, W.; Qin, D.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Ding, B.; Li, Y.; Liang, G. Prediction of Bitterant and Sweetener Using Structure-Taste Relationship Models Based on an Artificial Neural Network. Food Res. Int. 2022, 153, 110974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.; Keum, J.; Nam, H. DeepConv-DTI: Prediction of Drug-Target Interactions via Deep Learning with Convolution on Protein Sequences. PLoS Comput Biol 2019, 15, e1007129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Ru, X.; Song, R. Application of Machine Learning for Drug–Target Interaction Prediction. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 680117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, M.; Zhang, Z.; Niu, S.; Sha, H.; Yang, R.; Yun, Y.; Lu, H. Deep-Learning-Based Drug-Target Interaction Prediction. J. Proteome Res. 2017, 16, 1401–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Fu, T.; Glass, L.M.; Zitnik, M.; Xiao, C.; Sun, J. DeepPurpose: A Deep Learning Library for Drug–Target Interaction Prediction. Bioinformatics 2021, 36, 5545–5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Zhang, X.; Lin, X. Drug–Target Interaction Prediction via Multiple Classification Strategies. BMC Bioinf. 2022, 22, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldeghi, M.; Coley, C.W. A Graph Representation of Molecular Ensembles for Polymer Property Prediction. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 10486–10498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Liu, L.; Lei, J.; He, D.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, J.; Wang, F.; Wu, H.; Wang, H. Geometry-Enhanced Molecular Representation Learning for Property Prediction. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2022, 4, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Gao, K.; Nguyen, D.D.; Chen, X.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, G.-W.; Pan, F. Algebraic Graph-Assisted Bidirectional Transformers for Molecular Property Prediction. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, D.; Wu, J.; Wang, L. FP-GNN: A Versatile Deep Learning Architecture for Enhanced Molecular Property Prediction. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbac408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Ji, H.; Lu, H.; Zhang, Z. Prediction of Liquid Chromatographic Retention Time with Graph Neural Networks to Assist in Small Molecule Identification. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 2200–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohani, A.; Mamarabadi, M. Free Alignment Classification of Dikarya Fungi Using Some Machine Learning Methods. Neural Comput. Appl. 2019, 31, 6995–7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; El Mekkaoui, K.; Reinvall, J.; Havulinna, A.S.; Marttinen, P.; Kaski, S. Gene–Gene Interaction Detection with Deep Learning. Commun Biol 2022, 5, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Park, S.; Min, D.; Kim, W. Comprehensive Survey of Recent Drug Discovery Using Deep Learning. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, D.; Hahn, M. Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 742–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Thiessen, P.A.; Bolton, E.E.; Bryant, S.H. PUG-SOAP and PUG-REST: Web Services for Programmatic Access to Chemical Information in PubChem. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, W605–W611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Xiao, C. Explainable Substructure Partition Fingerprint for Protein, Drug, and More.

- Stiefl, N.; Watson, I.A.; Baumann, K.; Zaliani, A. ErG: 2D Pharmacophore Descriptions for Scaffold Hopping. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2006, 46, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Commun. Acm 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubaki, M.; Tomii, K.; Sese, J. Compound–Protein Interaction Prediction with End-to-End Learning of Neural Networks for Graphs and Sequences. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.; van Merriënboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning Phrase Representations Using RNN Encoder–Decoder for Statistical Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); Association for Computational Linguistics: Doha, Qatar, October 2014; pp. 1724–1734.

- Li, M.; Zhou, J.; Hu, J.; Fan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, Y.; Karypis, G. DGL-LifeSci: An Open-Source Toolkit for Deep Learning on Graphs in Life Science. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 27233–27238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, D.; Tang, J.; Luo, B. Semi-Supervised Learning With Graph Learning-Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); June 2019. pp. 11305–11312.

- Duvenaud, D.; Maclaurin, D.; Aguilera-Iparraguirre, J.; Gómez-Bombarelli, R.; Hirzel, T.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; Adams, R.P. Convolutional Networks on Graphs for Learning Molecular Fingerprints. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems - Volume 2; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, December 7 2015; pp. 2224–2232.

- Hu, W.; Liu, B.; Gomes, J.; Zitnik, M.; Liang, P.; Pande, V.; Leskovec, J. Strategies for Pre-Training Graph Neural Networks 2020.

- Xiong, Z.; Wang, D.; Liu, X.; Zhong, F.; Wan, X.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Luo, X.; Chen, K.; Jiang, H.; et al. Pushing the Boundaries of Molecular Representation for Drug Discovery with the Graph Attention Mechanism. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 8749–8760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).