Submitted:

25 August 2023

Posted:

29 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Assessment of gene expression analysis techniques

4. Gene expression changes in amniocytes and amniotic fluid

5. Gene expression changes in the placenta

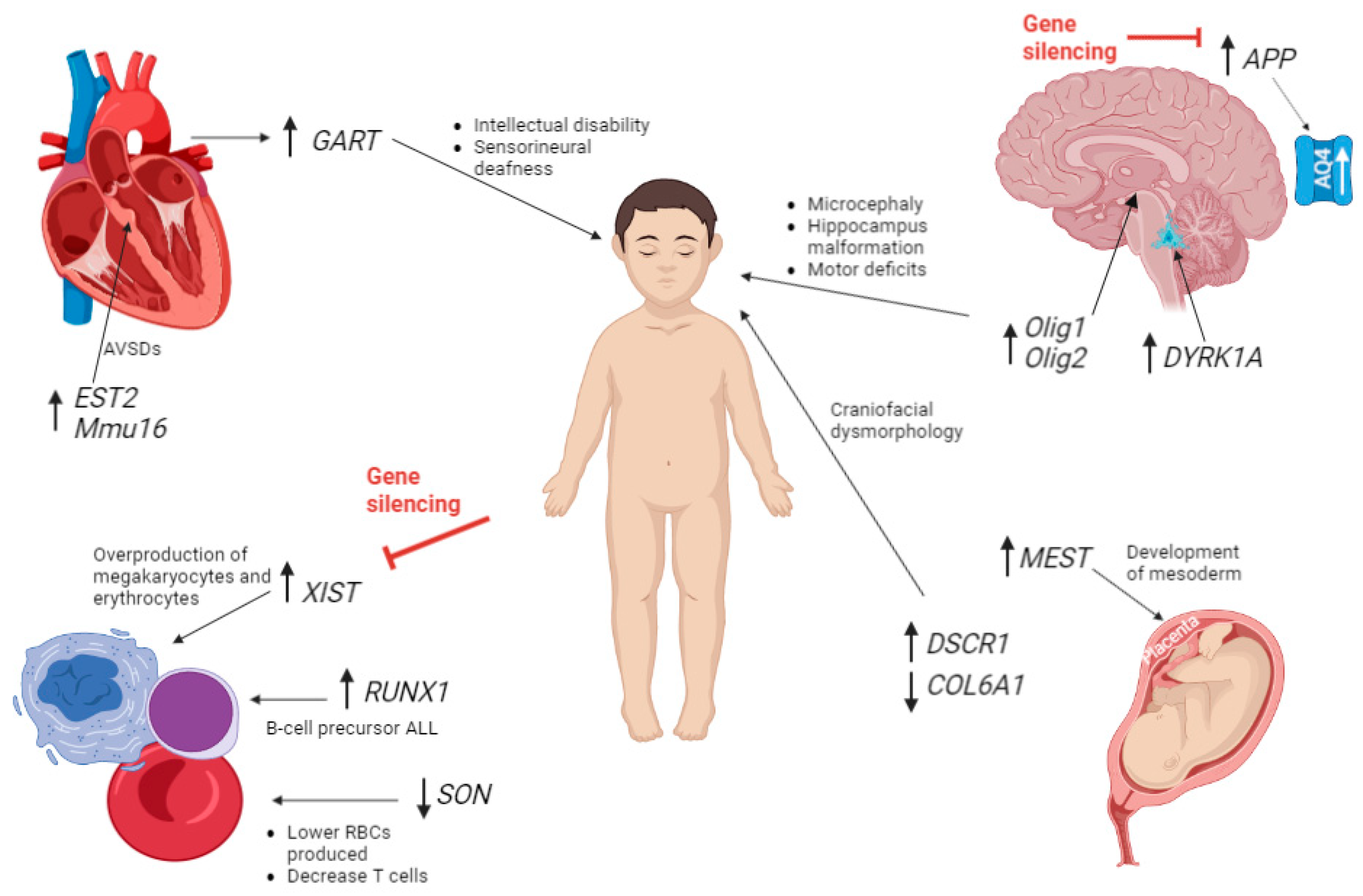

6. Gene expression changes affecting brain development.

7. Gene expression changes affecting cardiac tissues

8. Gene expression changes that lead to haematopoietic cells/myeloproliferative disease

9. Gene therapy for future implications

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carothers, A.D.; A Hecht, C.; Hook, E.B. International variation in reported livebirth prevalence rates of Down syndrome, adjusted for maternal age. J. Med Genet. 1999, 36, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Korenberg, J.R.; Chen, X.N.; Schipper, R.; Sun, Z.; Gonsky, R.; Gerwehr, S.; et al. Down syndrome phenotypes: the consequences of chromosomal imbalance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994, 91, 4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidman, R.L.; Rakic, P. Neuronal migration, with special reference to developing human brain: a review. Brain Res. 1973, 62, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, J.-C.; Jiang, J.; Newburger, P.E.; Lawrence, J.B. Trisomy silencing by XIST normalizes Down syndrome cell pathogenesis demonstrated for hematopoietic defects in vitro. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozovski, U.; Jonish-Grossman, A.; Bar-Shira, A.; Ochshorn, Y.; Goldstein, M.; Yaron, Y. Genome-wide expression analysis of cultured trophoblast with trisomy 21 karyotype. Hum. Reprod. 2007, 22, 2538–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.J.; Cho, H.Y.; Cha, D.H. The Amniotic Fluid Cell-Free Transcriptome Provides Novel Information about Fetal Development and Placental Cellular Dynamics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.E.; Lim, J.H.; Kim, M.H.; Park, S.Y.; Ryu, H.M. Novel Epigenetic Markers on Chromosome 21 for Noninvasive Prenatal Testing of Fetal Trisomy 21. J. Mol. Diagn. 2016, 18, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.-L.; Liu, Z.-Z.; Wang, H.-D.; Wu, D.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, H.; Chu, Y.; Hou, Q.-F.; Liao, S.-X. Integrated miRNA and mRNA expression profiling in fetal hippocampus with Down syndrome. J. Biomed. Sci. 2016, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.; Engel, J.; Teichmann, S.A.; Lönnberg, T. A practical guide to single-cell RNA-sequencing for biomedical research and clinical applications. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamoulis, G.; Garieri, M.; Makrythanasis, P.; Letourneau, A.; Guipponi, M.; Panousis, N.; Sloan-Béna, F.; Falconnet, E.; Ribaux, P.; Borel, C.; et al. Single cell transcriptome in aneuploidies reveals mechanisms of gene dosage imbalance. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdyukov, S.; Bullock, M. DNA Methylation Analysis: Choosing the Right Method. Biology 2016, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letourneau, A.; Santoni, F.A.; Bonilla, X.; Sailani, M.R.; Gonzalez, D.; Kind, J.; Chevalier, C.; Thurman, R.; Sandstrom, R.S.; Hibaoui, Y.; et al. Domains of genome-wide gene expression dysregulation in Down’s syndrome. Nature 2014, 508, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonaros, F.; Zenatelli, R.; Guerri, G.; Bertelli, M.; Locatelli, C.; Vione, B.; Catapano, F.; Gori, A.; Vitale, L.; Pelleri, M.C.; et al. The transcriptome profile of human trisomy 21 blood cells. Hum. Genom. 2021, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allyse, M.; Minear, M.; Rote, M.; Hung, A.; Chandrasekharan, S.; Berson, E.; Sridhar, S. Non-invasive prenatal testing: a review of international implementation and challenges. Int. J. Women's Heal. 2015, 7, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Practice Bulletin, No. 162: Prenatal Diagnostic Testing for Genetic Disorders. The American College of Obstet Gynecol 2016, 127, e108–e122. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, I.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Lee, K.-W.; Park, S.-H.; Cha, K.-Y.; Kim, N.-S.; Yoo, H.-S.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, S. Gene Expression Analysis of Cultured Amniotic Fluid Cell with Down Syndrome by DNA Microarray. J. Korean Med Sci. 2005, 20, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COL6A1 Gene - GeneCards | CO6A1 Protein | CO6A1 Antibody. https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=COL6A1. (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Altug-Teber, Ö.; Bonin, M.; Walter, M.; Mau-Holzmann, U.; Dufke, A.; Stappert, H.; Tekesin, I.; Heilbronner, H.; Nieselt, K.; Riess, O. Specific transcriptional changes in human fetuses with autosomal trisomies. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2007, 119, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, G.E.; Howard, C.M.; Farrer, M.J.; Coleman, M.M.; Bennett, L.B.; Cullen, L.M.; et al. Genetic variation in the COL6A1 region is associated with congenital heart defects in trisomy 21 (Down's syndrome). Ann Hum Genet 1995, 59, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anlar, B.; Atilla, P.; Çakar, A.N.; Kose, M.F.; Beksaç, M.S.; Dagdeviren, A.; Akçören, Z. Expression of adhesion and extracellular matrix molecules in the developing human brain. J. Child Neurol. 2002, 17, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftis, M.J.; Sexton, D.; Carver, W. Effects of collagen density on cardiac fibroblast behavior and gene expression. J. Cell. Physiol. 2003, 196, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, J.J.; Genescà, L.; Kingsbury, T.J.; Cunningham, K.W.; Pérez-Riba, M.; Estivill, X.; de la Luna, S. DSCR1, overexpressed in Down syndrome, is an inhibitor of calcineurin-mediated signaling pathways. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000, 9, 1681–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, L.E.; Richtsmeier, J.T.; Leszl, J.; Reeves, R.H. A Chromosome 21 Critical Region Does Not Cause Specific Down Syndrome Phenotypes. Science 2004, 306, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slonim, D.K.; Koide, K.; Johnson, K.L.; Tantravahi, U.; Cowan, J.M.; Jarrah, Z.; et al. Functional genomic analysis of amniotic fluid cell-free mRNA suggests that oxidative stress is significant in Down syndrome fetuses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009, 106, 9425–9429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhou, M.; Xiong, Z.; Peng, F.; Wei, W. The cAMP-PKA signaling pathway regulates pathogenicity, hyphal growth, appressorial formation, conidiation, and stress tolerance in Colletotrichum higginsianum. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, A.; Ahmed, M.; Dhanasekaran, A.R.; Tong, S.; Gardiner, K.J. Sex differences in protein expression in the mouse brain and their perturbations in a model of Down syndrome. Biol. Sex Differ. 2015, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Mo, J.; Zhao, G.; Lin, Q.; Wei, G.; Deng, W.; Chen, D.; Yu, B. Application of the amniotic fluid metabolome to the study of fetal malformations, using Down syndrome as a specific model. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 7405–7415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, S.J.; Ferreira, J.C.; Morrow, B.; Dar, P.; Funke, B.; Khabele, D.; Merkatz, I. Gene expression profile of trisomy 21 placentas: A potential approach for designing noninvasive techniques of prenatal diagnosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 187, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishita, Y.; Yoshida, I.; Sado, T.; Takagi, N. Genomic imprinting and chromosomal localization of the human MEST gene. Genomics 1996, 36, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lott, I.T. Neurological phenotypes for Down syndrome across the life span. 197. [CrossRef]

- El Hajj, N.; Dittrich, M.; Böck, J.; Kraus, T.F.J.; Nanda, I.; Müller, T.; Seidmann, L.; Tralau, T.; Galetzka, D.; Schneider, E.; et al. Epigenetic dysregulation in the developing Down syndrome cortex. Epigenetics 2016, 11, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, F.; Shao, B.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, R.; Liu, G.; Meng, L.; Hu, P.; Xu, Z. A De Novo Mutation in DYRK1A Causes Syndromic Intellectual Disability: A Chinese Case Report. Front. Genet. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, J. DNA methyltransferases and their roles in tumorigenesis. Biomark. Res. 2017, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmos-Serrano, J.L.; Kang, H.J.; Tyler, W.A.; Silbereis, J.C.; Cheng, F.; Zhu, Y.; Pletikos, M.; Jankovic-Rapan, L.; Cramer, N.P.; Galdzicki, Z.; et al. Down Syndrome Developmental Brain Transcriptome Reveals Defective Oligodendrocyte Differentiation and Myelination. Neuron 2016, 89, 1208–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, D.J.; Duka, T.; Stimpson, C.D.; Schapiro, S.J.; Baze, W.B.; McArthur, M.J.; Fobbs, A.J.; Sousa, A.M.M.; Šestan, N.; Wildman, D.E.; et al. Prolonged myelination in human neocortical evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 16480–16485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benes, F.M.; Turtle, M.; Khan, Y.; Farol, P. Myelination of a Key Relay Zone in the Hippocampal Formation Occurs in the Human Brain During Childhood, Adolescence, and Adulthood. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1994, 51, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, C.; Ma, D. MicroRNA-125b-2 overexpression represses ectodermal differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 36, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.H.; Lee, D.E.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, K.S.; Han, Y.J.; Kim, M.H.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, M.Y.; Ryu, H.M.; et al. MicroRNAs as potential biomarkers for noninvasive detection of fetal trisomy 21. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2015, 32, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, R.; Ishihara, K.; Kawashita, E.; Sago, H.; Yamakawa, K.; Mizutani, K.-I.; Akiba, S. Decrease in the T-box1 gene expression in embryonic brain and adult hippocampus of down syndrome mouse models. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 535, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Lian, G.; Zhou, H.; Esposito, G.; Steardo, L.; Delli-Bovi, L.C.; Hecht, J.L.; Lu, Q.R.; Sheen, V. OLIG2 over-expression impairs proliferation of human Down syndrome neural progenitors. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 2330–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G.; Imitola, J.; Lu, J.; De Filippis, D.; Scuderi, C.; Ganesh, V.S.; Folkerth, R.; Hecht, J.; Shin, S.; Iuvone, T.; et al. Genomic and functional profiling of human Down syndrome neural progenitors implicates S100B and aquaporin 4 in cell injury. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007, 17, 440–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moftakhar, P.; Lynch, M.D.; Pomakian, J.L.; Vinters, H.V. Aquaporin Expression in the Brains of Patients With or Without Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2010, 69, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandebroek, A.; Yasui, M. Regulation of AQP4 in the Central Nervous System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonarakis, S.E.; Skotko, B.G.; Rafii, M.S.; Strydom, A.; Pape, S.E.; Bianchi, D.W.; et al. Down syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.M.; Guo, M.; Salas, M.; Schupf, N.; Silverman, W.; Zigman, W.B.; et al. Cell type-specific over-expression of chromosome 21 genes in fibroblasts and fetal hearts with trisomy 21. BMC Med Genet 2006, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosman, A.; Letourneau, A.; Sartiani, L.; Del Lungo, M.; Ronzoni, F.; Kuziakiv, R.; Tohonen, V.; Zucchelli, M.; Santoni, F.; Guipponi, M.; et al. Perturbations of Heart Development and Function in Cardiomyocytes from Human Embryonic Stem Cells with Trisomy 21. STEM CELLS 2015, 33, 1434–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Morishima, M.; Jiang, X.; Yu, T.; Meng, K.; Ray, D.; Pao, A.; Ye, P.; Parmacek, M.S.; Yu, Y.E. Engineered chromosome-based genetic mapping establishes a 3.7 Mb critical genomic region for Down syndrome-associated heart defects in mice. Hum. Genet. 2013, 133, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izzo, A.; Manco, R.; de Cristofaro, T.; Bonfiglio, F.; Cicatiello, R.; Mollo, N.; De Martino, M.; Genesio, R.; Zannini, M.; Conti, A.; et al. Overexpression of Chromosome 21 miRNAs May Affect Mitochondrial Function in the Hearts of Down Syndrome Fetuses. Int. J. Genom. 2017, 2017, 8737649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, D.; Braidy, N.; De Rasmo, D.; Signorile, A.; Rossi, L.; Atanasov, A.; Volpicella, M.; Henrion-Caude, A.; Nabavi, S.; Vacca, R. Mitochondria as pharmacological targets in Down syndrome. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 114, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitzler, J.K.; Zipursky, A. Origins of leukaemia in children with Down syndrome. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, G.V. Transient leukemia in newborns with Down syndrome. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2004, 44, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasle, H.; Haunstrup Clemmensen, I.; Mikkelsen, M. Risks of leukaemia and solid tumours in individuals with Down’s syndrome. Lancet 2000, 355, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, Y.; Uryu, K.; Ito, T.; Seki, M.; Kawai, T.; Isobe, T.; Kumagai, T.; Toki, T.; Yoshida, K.; Suzuki, H.; et al. Integrated genetic and epigenetic analysis revealed heterogeneity of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Down syndrome. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 3358–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muskens, I.S.; Li, S.; Jackson, T.; Elliot, N.; Hansen, H.M.; Myint, S.S.; Pandey, P.; Schraw, J.M.; Roy, R.; Anguiano, J.; et al. The genome-wide impact of trisomy 21 on DNA methylation and its implications for hematopoiesis. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belmonte, R.L.; Engbretson, I.L.; Kim, J.-H.; Cajias, I.; Ahn, E.-Y.E.; Stachura, D.L. son is necessary for proper vertebrate blood development. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0247489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishihara, K.; Shimizu, R.; Takata, K.; Kawashita, E.; Amano, K.; Shimohata, A.; Low, D.; Nabe, T.; Sago, H.; Alexander, W.S.; et al. Perturbation of the immune cells and prenatal neurogenesis by the triplication of the Erg gene in mouse models of Down syndrome. Brain Pathol. 2019, 30, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taoudi, S.; Bee, T.; Hilton, A.; Knezevic, K.; Scott, J.; Willson, T.A.; Collin, C.; Thomas, T.; Voss, A.K.; Kile, B.T.; et al. ERG dependence distinguishes developmental control of hematopoietic stem cell maintenance from hematopoietic specification. Minerva Anestesiol. 2011, 25, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Koch, M.L.; Zhang, X.; Hamblen, M.J.; Godinho, F.J.; Fujiwara, Y.; Xie, H.; Klusmann, J.-H.; Orkin, S.H.; Li, Z. Reduced Erg Dosage Impairs Survival of Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells. STEM CELLS 2017, 35, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.-F.; Worley, L.; Rinchai, D.; Bondet, V.; Jithesh, P.V.; Goulet, M.; Nonnotte, E.; Rebillat, A.S.; Conte, M.; Mircher, C.; et al. Three Copies of Four Interferon Receptor Genes Underlie a Mild Type I Interferonopathy in Down Syndrome. J. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 40, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.T.; Jaenisch, R. Long-range cis effects of ectopic X-inactivation centres on a mouse autosome. Nature 1997, 386, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Jing, Y.; Cost, G.J.; Chiang, J.-C.; Kolpa, H.J.; Cotton, A.M.; Carone, D.M.; Carone, B.R.; Shivak, D.A.; Guschin, D.Y.; et al. Translating dosage compensation to trisomy 21. Nature 2013, 500, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, A.; Lohn, Z.; Austin, J.C.; Hippman, C. A “cure” for Down syndrome: What do parents want? Clin Genet 2014, 86, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czermiński, J.T.; Lawrence, J.B. Silencing Trisomy 21 with XIST in Neural Stem Cells Promotes Neuronal Differentiation. Dev. Cell 2020, 52, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wutz, A.; Jaenisch, R. A Shift from Reversible to Irreversible X Inactivation Is Triggered during ES Cell Differentiation. Mol. Cell 2000, 5, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.B.; Chang, K.-H.; Wang, P.-R.; Hirata, R.K.; Papayannopoulou, T.; Russell, D.W. Trisomy Correction in Down Syndrome Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 11, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amano, T.; Jeffries, E.; Amano, M.; Ko, A.C.; Yu, H.; Ko, M.S.H. Correction of Down syndrome and Edwards syndrome aneuploidies in human cell cultures. DNA Res. 2015, 22, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondal, J.A. From the lab to the people: major challenges in the biological treatment of Down syndrome. AIMS Neurosci. 2021, 8, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, T.G. Considerations for the use of transcriptomics in identifying the ‘genes that matter’ for environmental adaptation. J. Exp. Biol. 2015, 218, 1925–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacoma, T. Electrophoresis Process. Sciencing. Available online: https://sciencing.com/electrophoresis-process-5481819.html (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Wu, B. Immunohistochemistry stains. DermNet. 2015. Available online: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/immunohistochemistry-stains (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Marmiroli N and Maestri E. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). Science Direct. Food Toxicants Analysis: Techniques, Strategies and Developments, 2007. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/real-time-polymerase-chain-reaction#:~:text=Significant%20advantages%20of%20real%2Dtime,expensive%20than%20traditional%20PCR%20machines (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Cole, M. What are the advantages & disadvantages of flow cytometry? Sciencing. 2018. Available online: https://sciencing.com/calculate-cell-concentration-2788.html (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Luo, Q.; Zhang, H. Emergence of Bias During the Synthesis and Amplification of cDNA for scRNA-seq. Adv Exp Med Biol 2018, 1068, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, A.J.; Graham, C.; Bleskan, J.; Brodsky, G.; Patterson, D. Mutations in the Chinese hamster ovary cell GART gene of de novo purine synthesis. Gene 2009, 429, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.-J.; Lee, J.-G.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, S.-Y.; Huh, Y.H.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, K.-S.; Yu, K.; Lee, J.-S. Vascular defects of DYRK1A knockouts are ameliorated by modulating calcium signaling in zebrafish. Dis. Model. Mech. 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Hazen, S.L. Myeloperoxidase and Cardiovascular Disease. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005, 25, 1102–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly6c1 lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus C1 [Mus musculus (house mouse)] - Gene – NCBI. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/17067 (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Danopoulos, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Deutsch, G.; Nih, L.R.; Slaunwhite, C.; Mariani, T.J.; Al Alam, D. Prenatal histological, cellular, and molecular anomalies in trisomy 21 lung. J. Pathol. 2021, 255, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Technique | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Microarray analysis | • Results can be validated using real-time PCR High throughput method allowing expression levels of thousands of genes at once |

• Poor accuracy due to difficultly interpreting copy number variants of unknown significance7 Limited to genomic sequences Problems with probes cross-hybridization or sub-standard hybridization |

| DNA methylation analysis |

• Highly sensitive - can detect DNA methylation levels as low as 0.5% Very accurate in quantification Increase understanding of gene regulation and identify potential biomarkers33 |

• Multiple different ways of analysing DNA methylation with some disadvantages to each |

| Quantitative transcriptome map |

• Allows overview of changes in a whole organ Can be further validated by RT-PCR |

• Inappropriate for identifying genes with large impacts on adaptive responses to the environement68 mRNA abundance is an unreliable indicator of protein activity68 Standard practice in analysis is limited by prioritising highly differentially expressed genes over those who have moderate fold-changes and can’t be annotated68 |

| Western blot | • Sensitivity, able to detect 0.1 nanograms of protein, can be used in early diagnosis69 Specificity due to gel electrophoresis and the specificity of the antibody-antigen interaction69 |

• Time-consuming process Skilled analysts and laboratory equipment, minor error in the process can cause incorrect results, false negatives if proteins are not given enough incubation time69 It is non-quantitative Primary antibodies needed can be expensive. Antibodies can sometimes bind off-target. False-positive results due to antibodies reacting with a non-intended protein69 |

| Immunohistochemistry | • Relatively low cost70 Quick Can be done on fresh/frozen tissue samples70 Allows in-situ verification of various antibodies at the same time in organs, tissues and cells Can be done on fresh/frozen tissue samples70 |

• Not standardised worldwide70 The process is cheap, but the initial equipment to run it is expensive70 It is non-quantitative70 High chance of human error and relies on antibody staining optimization70 |

| Real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) | • Measure RNA concentrations over a large range Sensitive Process multiple samples simultaneously71 Provides immediate information71 |

• Requires optimization of good primers and correct reaction conditions |

| Flow cytometry analysis | • Fast single cell multiparametric analysis Very accurate and can be used on very small populations of cells72 Good at highlighting non-uniformity72 Produces very detailed data72 |

• Very slow analysis72 More expensive than alternate assays.72 It is non-quantitative; it provides average densities but not specific amounts72 • Relies on antibody staining optimization and requires very specialized instrumentation for the analysis |

| Single cell RNA sequencing | • Assess quantification and sequence of RNA using Next Generation Sequencing (NGS)73 Uses short reads of mRNA and reveal which genes are turned on73 Allows detection of novel transcripts and is quantifiable73 |

• Isolation of sufficient high quality RNA, low throughput73 RNA degrades rapidly. Subjected to amplification bias73 |

| Gene/miRNA | Chromosome position | Gene expression change | How this affects development | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nervous system | NRSF/REST23 | 4q12 | Downregulated | Transcriptional repressor represses neuronal genes in non-neuronal tissues.40 |

| Ngn135 | 14 | Downregulated | Neuronal cell death | |

| Ngn235 | 4 | Downregulated | ||

| Pax635 | 11 | Downregulated | ||

| DNMT3A23 | 2q23 | Downregulated | DNA methylation in late stage of embryonic development | |

| DNMT3B23 | 20q11.2 | Downregulated | DNA methylation in broader range of genes in early embryonic development.8 | |

| PCDHG23 | 5q31 | Downregulated | Reduction in dendrite arborization and growth in cortical neurons | |

| M4338 | Downregulated | Regulation of action potential and axon ensheathment, neocortex and hippocampus over development | ||

| TBX135 | HSA22q11 | Downregulated | Fetal brain development and postnatal psychiatric phenotypes in DS | |

| Hsa-miR-138 39 | 16q13 | Upregulated | Hippocampus development | |

| hsa-miR-40939 | 14 | Upregulated | ||

| hsa-miR-138 -5p39 | 3 and 13 | Upregulated | Intellectual disability | |

| miR-125b-2 42 | 21 | Upregulated | Cognitive impairment, promotes neuronal differentiation | |

| mir-197349 | 21 | Upregulated | Regulating CNS and nervous systems | |

| mir-319649 | 20 | Upregulated | ||

| Olig135 | Critical region 21 | Upregulated | Microcephaly, cortical dyslamination, hippocampus malformation, profound motor deficits. Promotes enhancer regions of Nfact4, Dscr1/Rcan1 and Dyrk1a > DS phenotype. |

|

| Olig235 | Critical region 21 | Upregulated | ||

| S100B45 | DSCR | Upregulated | Activate the stress response kinase pathways and upregulated aquaporin 4. | |

| APP45 | DSCR | Upregulated | ||

| DYRK1A23 | 21qq22.13 | Upregulated | Reduces NRSF/REST | |

| DNMT3L23 | 21q22.4 | Upregulated | De novo methylation in neuroprogenitors, persist in foetal DS brain | |

| Cardiac | miR-99a-5p 49 | 21q21.1 | Downregulated | Congenital heart defects |

| miR-155-5p49 | 21 | Downregulated | Mitochondrial dysfunction | |

| Let-7c-5p 49 | 21q21.1 | Downregulated | ||

| GART 45 | 21 | Upregulated | De novo purine synthesis > intellectual disability, hypotonia, increased sensorineural deafness.74 | |

| EST2 47 | 21q22 | Upregulated | Most likely cause 2nd heart field development, AVSDs. | |

| Mmu16 48 | Tiam1-Kcnj6 region of 16 | Triplication | AVSDs | |

| Blood | SON 56 | 21 | Downregulated | Lower RBCs produced, brain and spinal malformations, reduced thrombocytes and myeloid cells, significant decrease in T cells. |

| STAT1 75 | 2q32.2 | Downregulated | Low = reduced Enhanced cellular response to IFN | |

| XIST 4 | Xq | Upregulated | X-chromosome inactivation in females, Induction corrected over-production of megakaryocytes and erythrocytes |

|

| RUNX1 54,55 | 21 | Hypermethylation | Differentiation of blood cells, B cells. | |

| S100a857 | 1q21 | Upregulated | Abundant in neutrophils/monocytes | |

| S100a957 | 1q21 | Upregulated | ||

| MPO57 | 17q12-24 | Upregulated | Creates reactive oxidant species, part of innate immune response and contributes to tissue damage during inflammation.70 | |

| Ly6c157 | 15 | Upregulated | Part of inflammatory response in atherosclerosis, regulates endothelial adhesion of CD8 T cells.71 | |

| IFN-αR1 40,,75 | 21 | Upregulated | Expressed on surface of monocytes, EBV-transformed B-cells. Immunodeficiency. | |

| IFN-αR240,,75 | 21 | Upregulated | ||

| IFN-γR2 75 | 12 | Upregulated | ||

| ERG57 | 21 | Triplication | Self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells and haematopoiesis in liver during embryogenesis Dysregulation of homeostatic proportion of population of immune cells in embryonic brain and decreased prenatal cortical neurogenesis |

|

| SOX278 | 3q26.33 | Downregulated | Reduction in airway smooth muscle discontinuous in proximal airway | |

| Lung | DYRK1A78 | DSCR | Upregulated | Reduced incidence of solid tumours (neuroblastoma) and defects in angiogenesis of central arteries developing in hindbrain |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).