Submitted:

22 August 2023

Posted:

23 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. SPFC model and simulations

2.2. Simulation detail

3. Results and Discussion

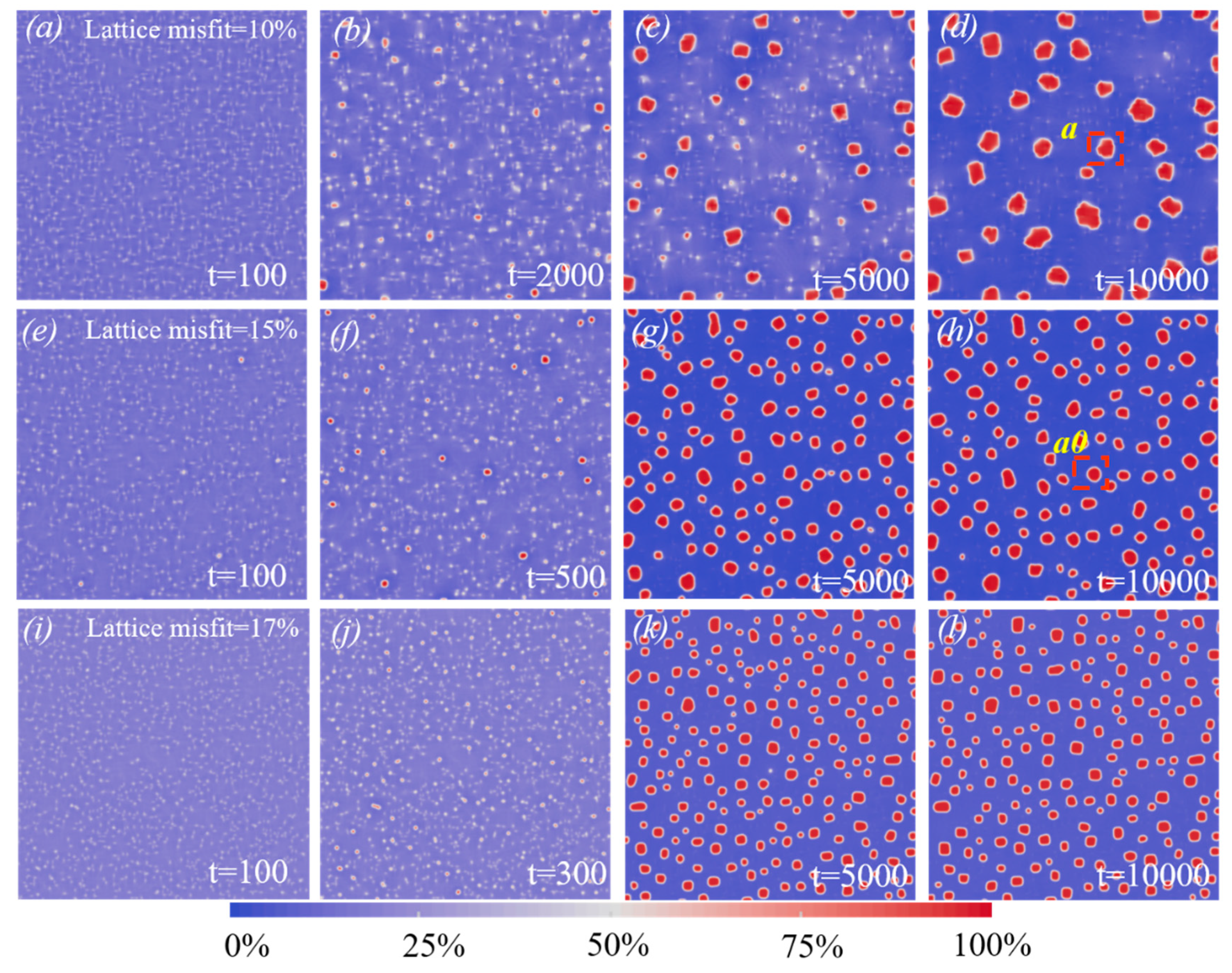

3.1. Precipitation simulations

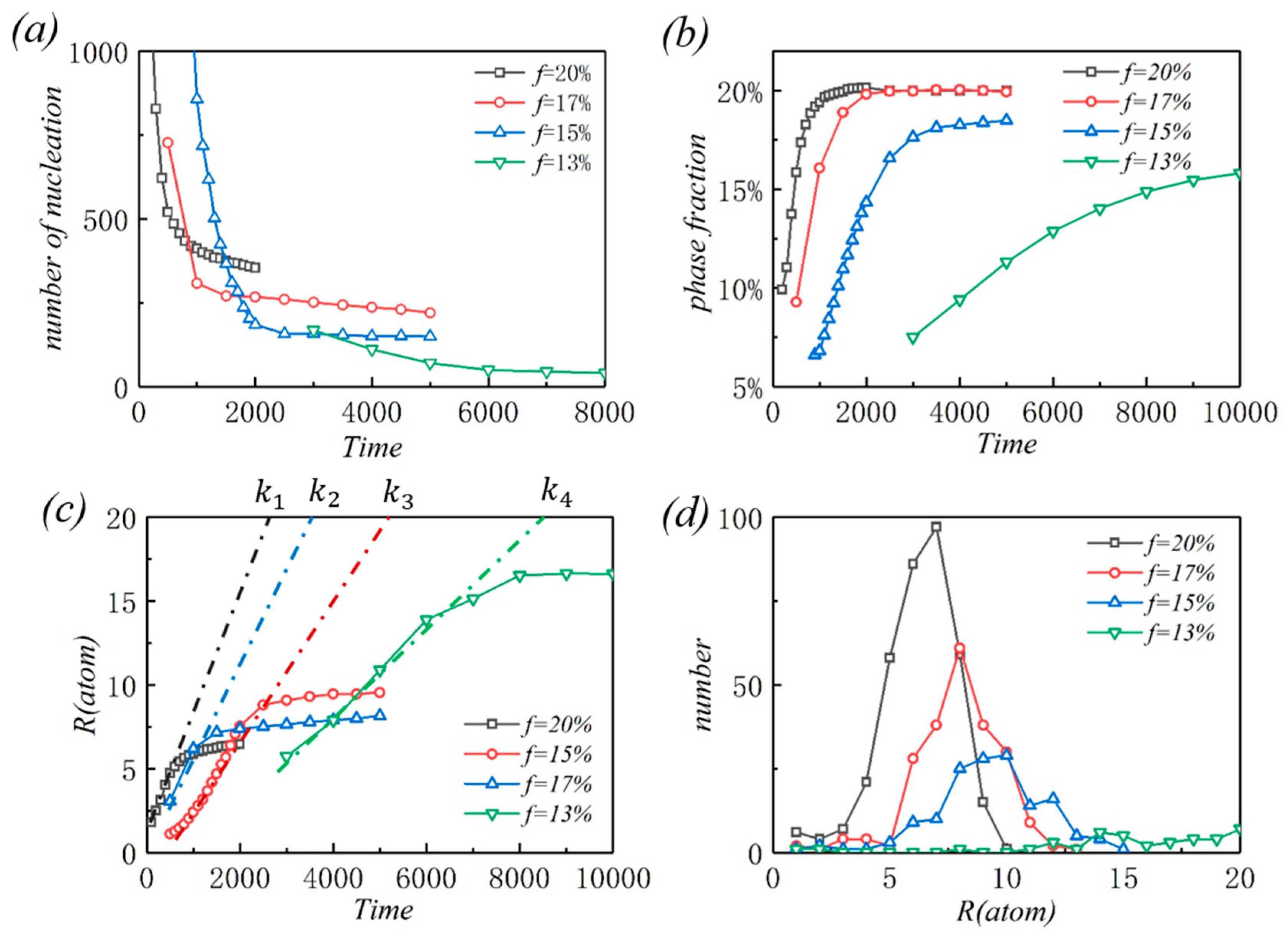

3.2. Kinetic analyses

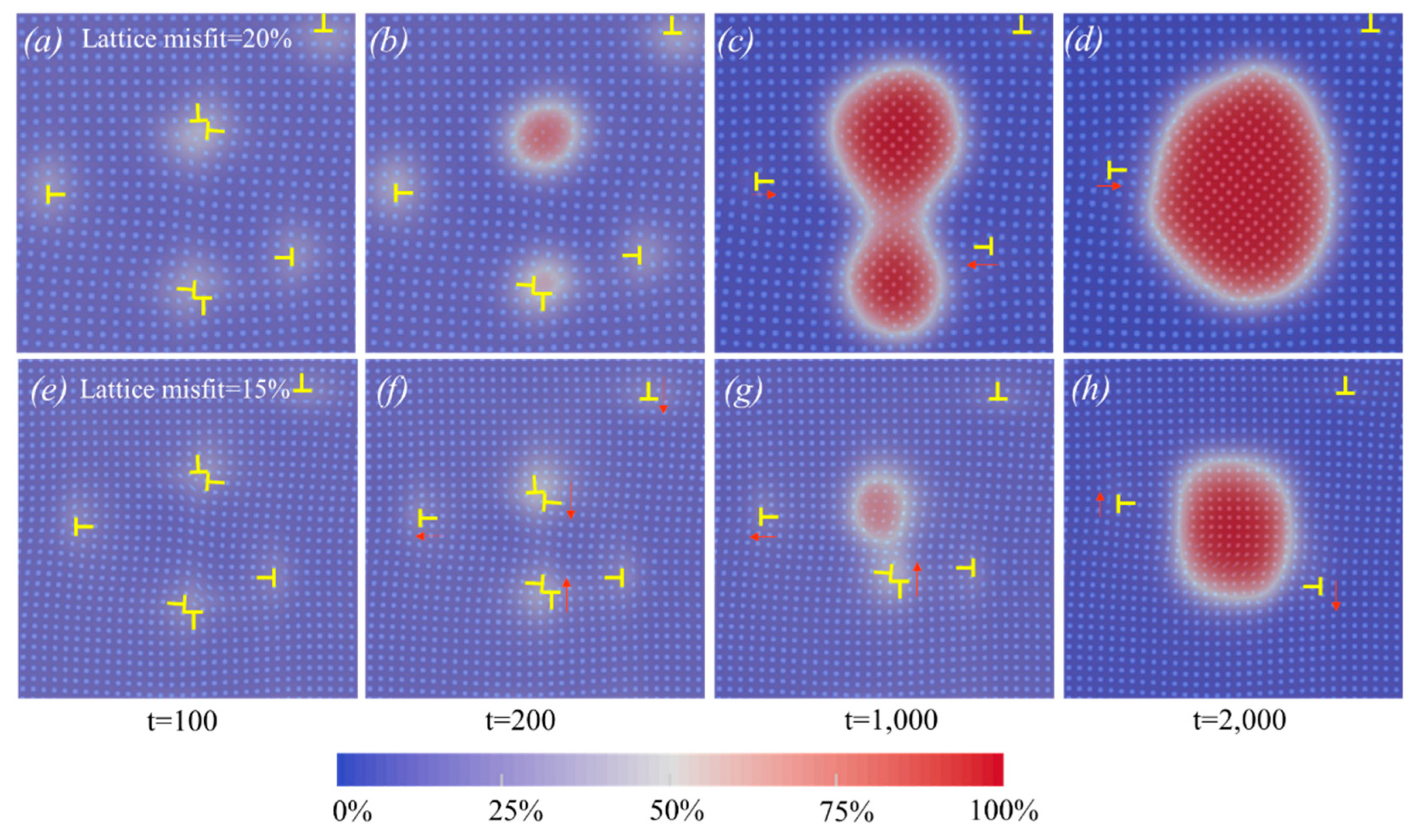

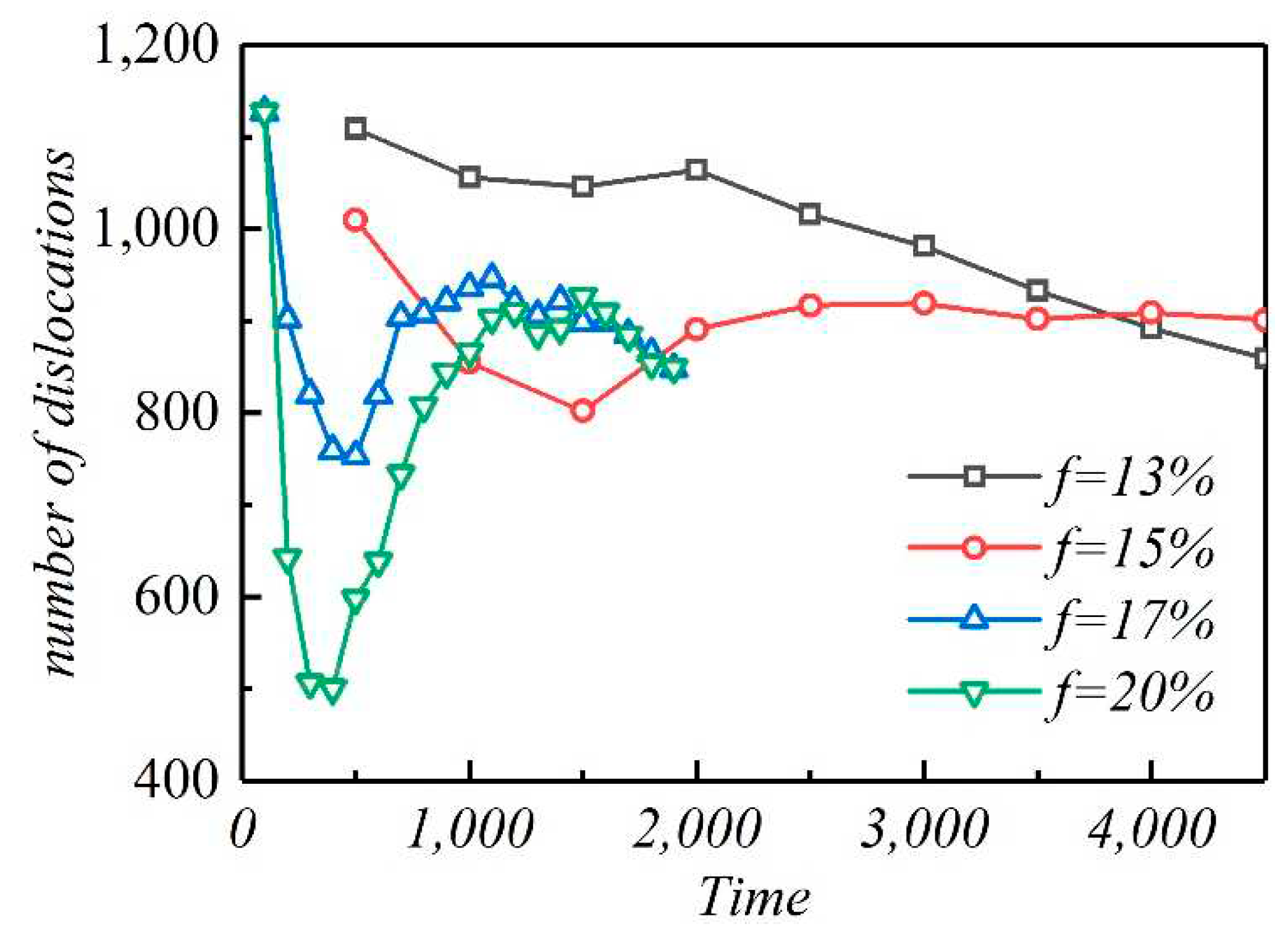

3.3. The interaction between dislocation and solute

4. Conclusions

- During the dislocation precipitation process, the high lattice misfit can significantly increase the concentration rate of solute atoms around dislocations and induce nucleation in a short time.

- The increasing misfit leads to decreased critical nucleation radius, making more small precipitation continue to grow. However, the total amount of solutes is limited, and more precipitates mean a smaller size.

- Dislocation precipitation can act as pinning and hinder dislocation motion. In addition, the aggregation of dislocations can accelerate dislocation precipitation. A relatively high lattice misfit will produce many precipitates during the early stage of aging, and the subsequent coarsening process will lead to the dissolution of some precipitates and the formation of dislocations.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tandon, R.; Mehta, K.K.; Manna, R.; Mandal, R.K. Effect of Tensile Straining on the Precipitation and Dislocation Behavior ofAA7075T7352 Aluminum Alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 163942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-Y.; Gao, Y.-J.; Deng, Q.-Q.; Li, Y.-X.; Huang, Z.-J.; Liao, K.; Luo, Z.-R. A nanoscale study of nucleation and propagation of Zener types cracks at dislocations: Phase field crystal model. Computational Materials Science 2020, 179, 109640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Dai, W.J.; Chen, Y.; Qi, Z.X.; Zheng, G.; Cao, Y.D.; Zhang, J.P.; Bu, C.C.; Chen, G. Control of dislocation density maximizing precipitation strengthening effect. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Ye, C.; Gao, H.; Kim, B.-J.; Suslov, S.; Stach, E.A.; Cheng, G.J. Dislocation pinning effects induced by nano-precipitates during warm laser shock peening: Dislocation dynamic simulation and experiments. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zhao, E.; Hu, C.; An, Y.; Chen, W. Precipitation behavior of silicide and synergetic strengthening mechanisms in TiB-reinforced high-temperature titanium matrix composites during multi-directional forging. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 867, 159051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.L.M.; Rezende, J.; Senk, D.; Kundin, J. Phase-field simulation of peritectic steels solidification with transformation-induced elastic effect. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2020, 9, 3805–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motazedian, F.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Z.; Jiang, D.; Sarkar, S.; Martyniuk, M.; Yan, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, H. Achieving ultra-large elastic strains in Nb thin films on NiTi phase-transforming substrate by the principle of lattice strain matching. Materials & Design 2021, 197, 109257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Zhao, B.; Dong, X.; Sun, F.; Zhang, L. Preferential growth of coherent precipitates at grain boundary. Mater. Lett. 2020, 261, 126984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Zhang, K.; Yeli, G.; Tong, Y.; Wei, D.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Kai, J.-J. Anomalous effect of lattice misfit on the coarsening behavior of multicomponent L12 phase. Scripta Mater. 2020, 183, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; Pang, S.; Li, X.; Dong, C.; Liaw, P.K. Coherent Precipitation and Strengthening in Compositionally Complex Alloys: A Review. Entropy (Basel) 2018, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Jiang et al. Nature 544, 460(2017).

- Zhou, C.L.W.L.; Xie, P.; Niu, F.J.; Ming, W.Q.; Du, K.; Chen, J.H. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 75, 126(2021).

- W. Chrominski and M. Lewandowska Materials Science and Engineering: A 793, 139903(2020).

- G. Brauer Anorg. Allg. Chem. 242, 1(1939).

- N. C. P. Norby Acta Chem. Scand. Ser. A 40, 157(1986).

- P. B. D. S.Srinivasan, R.B. P. B. D. S.Srinivasan, R.B.Schwarz Scripta Metallurgica et Materialia 25, 2513(1991).

- Shuai, X.; Mao, H.; Tang, S.; Kong, Y.; Du, Y. Growth modes of grain boundary precipitate in aluminum alloys under different lattice misfits. Journal of Materials Science 2022, 57, 2744–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-L.; Wen, Y.-H. Phase-field model of precipitation processes with coherency loss. npj Computational Materials 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, R.; Abinandanan, T.A.; Gururajan, M.P. Phase field study of precipitate growth: Effect of misfit strain and interface curvature. Acta Mater. 2009, 57, 3947–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadak, B.; Sankarasubramanian, R.; Choudhury, A. Phase-Field Modeling of Equilibrium Precipitate Shapes Under the Influence of Coherency Stresses. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 2018, 49, 5705–5726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trybula, M.E.; Szafrański, P.W.; Korzhavyi, P.A. Structure and chemistry of liquid Al–Cu alloys: molecular dynamics study versus thermodynamics-based modelling. Journal of Materials Science 2018, 53, 8285–8301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, X.; Mao, H.; Kong, Y.; Du, Y. Phase field crystal simulation of the structure evolution between the hexagonal and square phases at elevated pressures. Journal of Mining and Metallurgy, Section B: Metallurgy 2017, 53, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Tang, J. Wang, J. Li, Z. Wang, Y. Guo, C. Guo, and Y. Zhou Physical Review E 95(2017).

- N. P. Joel Berry, J¨org Rottler, Chad W. Sinclair PHYSICAL REVIEW B 86, 241142(2012).

- Fallah, V.; Ofori-Opoku, N.; Stolle, J.; Provatas, N.; Esmaeili, S. Simulation of early-stage clustering in ternary metal alloys using the phase-field crystal method. 2013, 61, 3653–3666. [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, M.; Rottler, J.; Provatas, N. Phase-field-crystal methodology for modeling of structural transformations. Physical Review E 2011, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallah, V.; Korinek, A.; Ofori-Opoku, N.; Provatas, N.; Esmaeili, S. Atomistic investigation of clustering phenomenon in the Al–Cu system: Three-dimensional phase-field crystal simulation and HRTEM/HRSTEM characterization. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 6372–6386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Todorova, T.Z.; Zwanziger, J.W. Temperature dependent lattice misfit and coherency of Al3X (X = Sc, Zr, Ti and Nb) particles in an Al matrix. Acta Mater. 2015, 89, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.Q.; Shen, J. Applications of semi-implicit Fourier-spectral method to phase field equations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1998, 108, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendiratta, M.G.; Ehlers, S.K.; Lipsitt, H.A. DO3-B2-α phase relations in Fe-Al-Ti alloys. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 1987, 18, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallybrass, C.; Sauthoff, G. Ferritic Fe–Al–Ni–Cr alloys with coherent precipitates for high-temperature applications. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2004, 387-389, 985–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreirós, P.A.; Alonso, P.R.; Rubiolo, G.H. Effect of Ti additions on phase transitions, lattice misfit, coarsening, and hardening mechanisms in a Fe2AlV-strengthened ferritic alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 806, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).