Submitted:

21 August 2023

Posted:

23 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 35R11; 91G29

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Merton’s Model, Vasicek, and Kealhofer

3.2. Brownian Motion Model (BM) and Power Law Brownian Motion Model

3.2.1. Introduction

3.2.2. Brownian Motion Model (BM)

3.2.3. Power Law Brownian Motion Model (PLBM)

3.3. The Bloomberg Corporate Default Risk Model (DRSK) for Public Firms

3.4. Modified Merton Model

3.4.1. Fractional and Conformable Derivatives

- , linearity

- =, product rule.

- , chain rule.

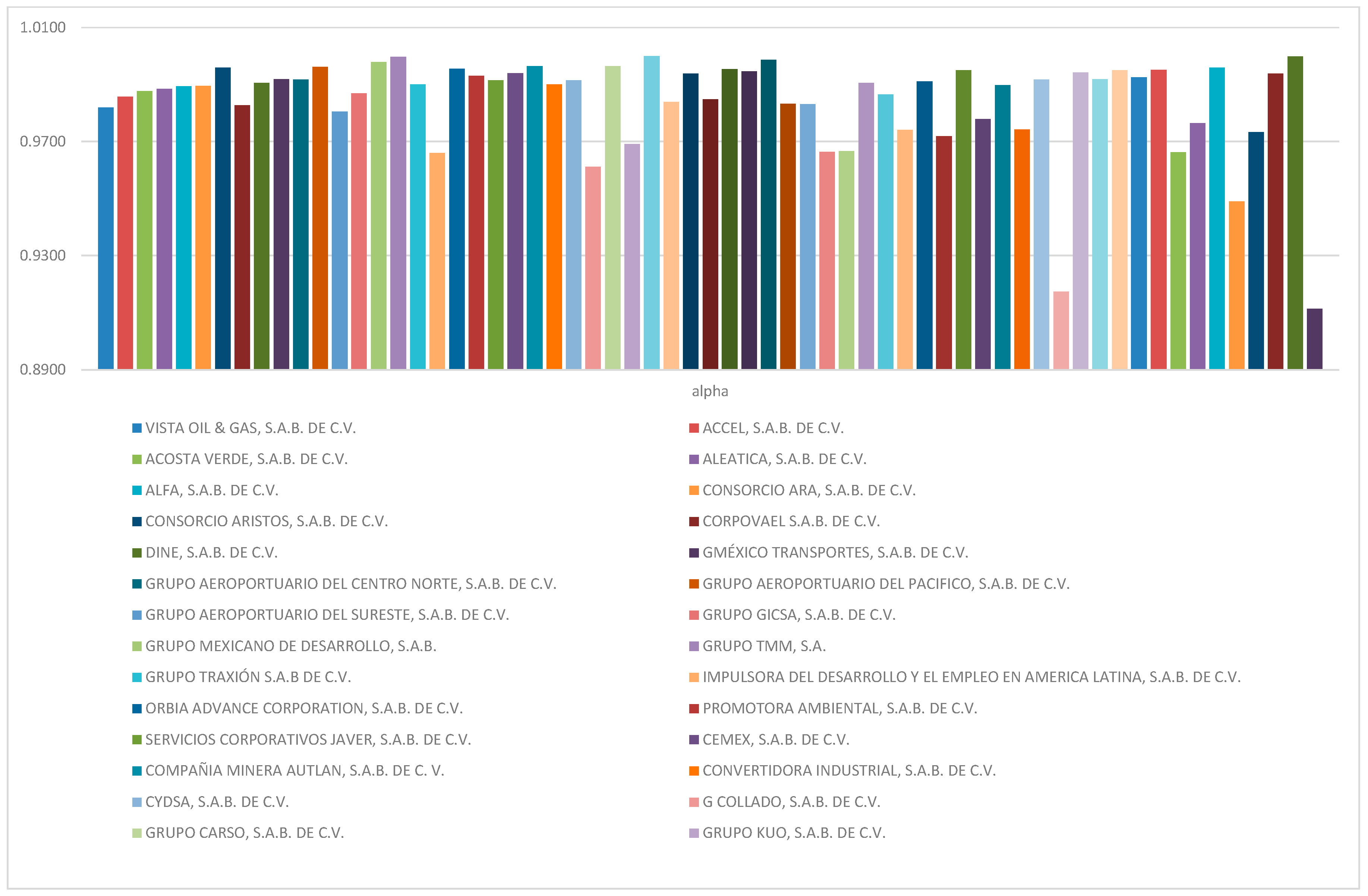

3.4.2. Proposed Model

Solving the Black, Scholes, and Merton Equation by conformable derivatives

3.4.3. Test Parameter

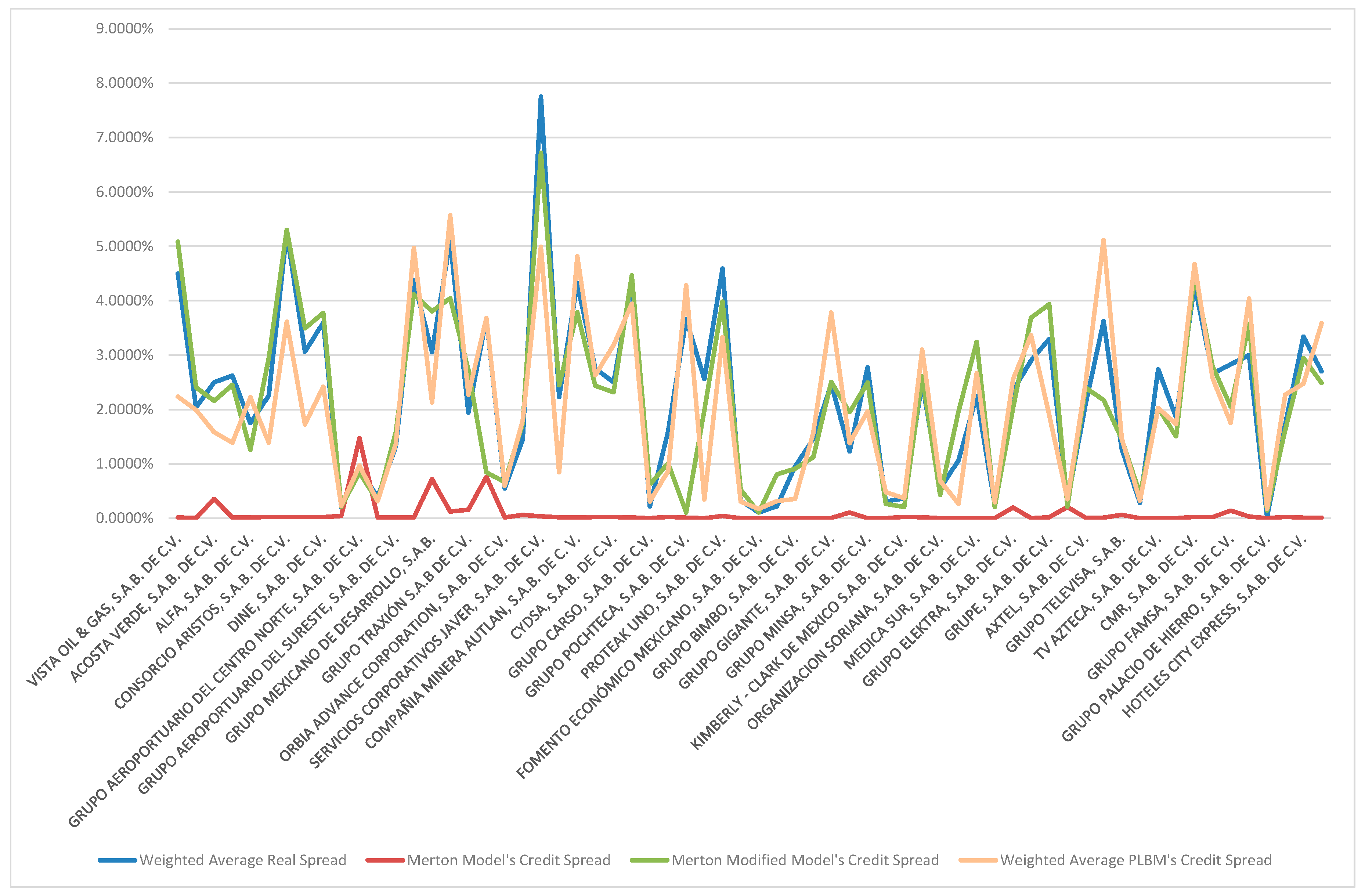

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Data collection

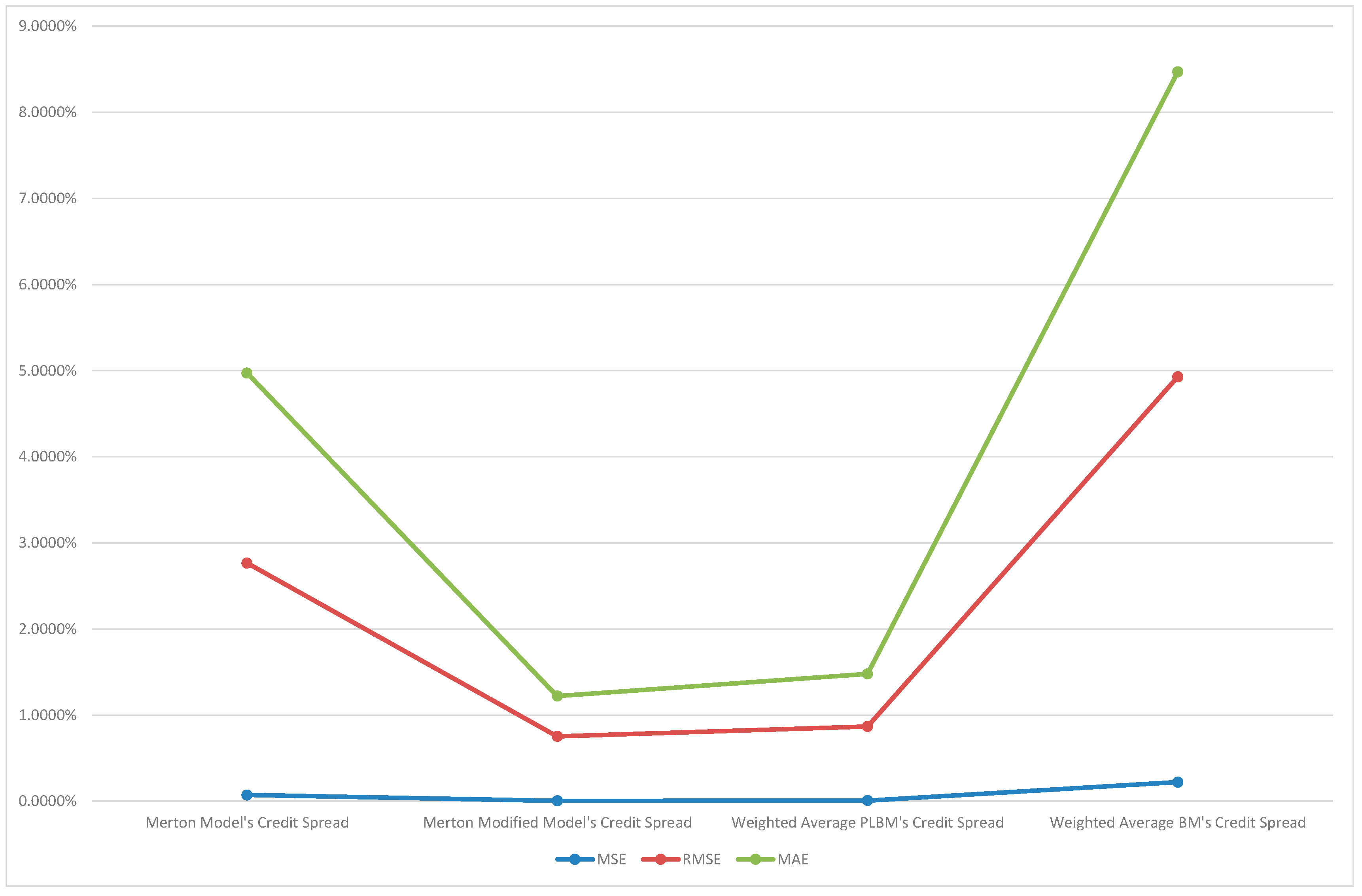

- In statistics, an estimator's mean squared error (MSE) measures the average of the squared errors, that is, the difference between the estimator and what is estimated. The MSE is a risk function corresponding to the expected value of the squared error loss or squared loss. The difference occurs because of randomness or because the estimator does not consider information that could produce a more accurate estimate. The MSE is the second moment (about the origin) of the error, and therefore incorporates both the estimator's variance and its bias. For an unbiased estimator, the MSE is the variance of the estimator. Like the variance, the MSE has the same units of measure as the square of the quantity estimated.

- In an analogy to the standard deviation, taking the square root of the MSE yields the root-mean-square error or root-mean-square deviation (RMSE or RMSD), which has the same units as the square of the quantity being estimated; for an unbiased estimator, the RMSE is the square root of the variance, known as the standard deviation.

- In statistic mean absolute error (MAE) is a measure of errors between paired observations expressing the same phenomenon. For example, Y versus X include comparisons of predicted versus observed. MAE is calculated as the sum of absolute errors (divided by the sample size:

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Merton, R. On Pricing of Corporate Debt: the Risk Structure of Interest Rates. J of Fin, 1974, 29, 449–469. [Google Scholar]

- Denzler, S.; Dacoronga, M.; Müller, U. and McNeil, A. From Default Probabilities to Credit Spreads: Credit Risk Models Do Explain Market Prices, Fin Res Lett. 2005, 3, 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Bañuelos, P. , Muriel, N. and Fernández-Anaya, G. A Modified Black-Scholes-Merton Model for Option Pricing. Mathem. 2022, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bondoli, M. , Goldberg, M., Hu, N. Li, C., Maalaoui, O., Stein, H. The Bloomberg Corporate Default Risk Model ((DRSK) for Public Firms. Quant R Anal, Bloomb, L.P 2021, 2–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kealhofer, S.; and Vasicek, O. Quantifying Credit Risk I: Default Prediction. Fin Ana J. 2003, 59, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, J. Options, Futures and Other Derivates. 7th. ed. Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008.

- Freeman, R.E.; Dmytriyev, S.D.; Phillips, R.A. Stkeholder theory and the resources -based view of the firm. J Manag. 2021, 47, 1757–1770. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, M.; Lazaroiu, G. Computer vision algorithms, remote sensing data fusión techniques, and mapping and navigatio in the Industry 4.0-based Slovak automotive sector. Mathem, 2022, 10, 3543. [Google Scholar]

- Stefko, R.; Horvathova, J. Mokrisova, M. The application of graphic methods and the DEA in predicting the risk of bankruptcy. J. Risk Financial Manag 2021, 14, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlicko, M.; Durica, M,; Mazanec, J. Ensamble Modelo f the Financial Distress Prediction in Visegrad Group Contries. Mathem 2021, 9, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Jumbe, G.; Gor, R. Credit Risk Modeling Using Default Models: A Review. J of Econ and Fina 2022, 13, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart, A. A comparison of Merton´s option pricing model of corporate debt valuation to use of book values. J of Corp Fina 2003, 11, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leland, H. Corporate Debt Value, Bonds Covenants, and Optimal Capital Structure. The J of Finan 1994, 45, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R, Sundaresan, S. A comparative study of structural models of corporate bond yields: An exploratory investigaion. J of Bank y Finan 2000, 24, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, J.; Reneby, J. The Valuation of Corporate Liabilities: Theory and Test. SSE/EFI. Working Paper Series in Econ and Finan 2002 submited.

- Eom, Y.; Helwege, J. ;Huang,J. Structural Models of Corporate Bonds Pricing: An Empirical Analysis. The Rev of Finan Stud 2008, 17, 499–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geske, R. The Valuation of Corporate Liabilities as Compound Options. J of Financ and Quanti Anal 1977, 12, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longstaff, F.; Schwartz, E. A Simple Approach to Valuing Risky Fixed and Floating Rate Debt. The J of Finan 1995, 50, 789–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leland, H.; Toft, K. Optimal Capital Structure, Endogenous Bankruptcy, and the Term Structure of Credit Spreads. J of Finan. 2001, 51, 987–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin-Dufresne, P.; Goldstein, R. Do Credit Spread Reflect Stationary Leverage Ratios? J of Finan, 2001, 56, 1929–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, J. Depressing Recoveries. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago in its J Emerg Issus 2020 1-13.

- Altman, E.; Kishore, V. Almost Everything You Wanted to Know About Recoveries of Default Bonds. Finan Analyst J. 1996 57-64.

- Acharya, V. V.; Bharath, S.T.; Srinivasan, A. Understanding the Recovery Rates of Indebtedness Securities. C.E.P.R. Working paper. 2004 London Business School, University of Michigan, University of Georgia.

- Hamilton, D.T. , Varma, S. Ou, S. y Cantor, R. (2005). Special Comment. Default and Recovery Rates of Corporate Bond Issuers, 1920-2004. Moody’s Investors Service, Global Credit Research. 2005 2-40.

- Black, F.; Scholes, M. (1973). The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities. J of Pol Econ, 1973, 81, 637–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J. An Empirical Analysis of Structural Models of Corporate Debt Pricing. J Finan Econ. 2007, 17, 1141–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzas, I.; Shreve, S. Brownian Motion and Stochastic Calculus. 2th. ed. Springer-Verlag. Berlin Heidelberg New York, 1988.

- Harrison, J. Brownian Motion and Stochastic Flow Systems 1first. Ed. John Wiley y Sohns, Inc., UK. 1985.

- Dixit, A. K. , Pindyck. R. Investment under Uncertainty, 1first. Ed. Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998.

- Kahlil, R.; Al Horani, M.; Yousef, A.; Sababheh, M. A new definition of factional derivate. J Comput. Appl. Math. 2014, 264, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glosten, L.; Jagannathan, R, Runkle, D. On the Relation between the Expected Value and the Volatility of the Nominal Excess Returns on Stocks. J of Finan. 1993, 1779–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R. , Camrud, E. and Ulness, D. On Nature of the Conformable Derivate and its Applications to Physics. J on Frac Calcul and Appl 2019, 10, 92–135. [Google Scholar]

- Katagumpola, U.N. A new fractional derivate with classical properties. arXiv:1410.6335.

- Katagumpola, U.N. A new approach to generalize fractional derivates. Bull. Math. Anal. Appl. 2016. 6, 1–15.

- Crosbie, P.; Bohn, J. Modeling Default Risk-Modeling Methodology. Moody’s K.M.V. Company LLC. 2003, 6-31.

- Gajdosikova, D.; Valaskova, K.; Kliestik, T.; Kovacova, M. Research on Corporate Indebtedness Determinants: A Case Study of Visegrad Group Countries. Mathem. 2023, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.; Siegel, A. Parsimonious Modeling of Yield Curves. J of Buss. 1997, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Porras, A. Globalización y proceso corporativo de los grandes grupos económicos en México. Rev Mex de Soc. 1992, 54, 133–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, E.; Brady, A.; Resti, A.; Sironi, A. The Link between Default and Recovery Rates: Implications for Credit Risk Models and Procyclicality. J of Bus, 2005, 78, 2203–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R. y Sundaresan, S. A comparative study of structural models of corporate bond yields: An exploratory investigation. J of Bank y Finan. 2000, 24, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomberg anywhere in 2023.

- (Risk Analytics, K.M.V. Moody’s 2023.

| Company | Sector | Currency | Total Amount of Debt | Weighted Average Duration | Number of Liabilities | Base Rate | Weighted Average Credit Spread | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VISTA OIL & GAS, S.A.B. DE C.V. | ENERGY | Mexican pesos | 374,433,035 | 1.56 | 1 | 1.29% | plus | 4.5000% |

| ACCEL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexicano pesos | 778,951,000 | 5.66 | 3 | 1.29% | plus | 2.0373% |

| ACOSTA VERDE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 3,056,401,729 | 7.34 | 17 | 4.63% | plus | 2.5000% |

| ALEATICA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 6,317,721,000 | 5.57 | 1 | 1.29% | plus | 2.6223% |

| ALFA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 50,000,000 | 2.36 | 1 | 4.,63% | plus | 1.7500% |

| CONSORCIO ARA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 507,034,000 | 5.49 | 7 | 4.63% | plus | 2.2571% |

| CONSORCIO ARISTOS, S.A.B. DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 62,160,150 | 4.89 | 7 | 4.63% | plus | 5.2459% |

| CORPOVAEL S.A.B. DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 3,091,729,000 | 1.59 | 22 | 4.63% | plus | 3.0629% |

| DINE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 210,000,000 | 2.08 | 1 | 4.63% | plus | 3.6000% |

| GMÉXICO TRANSPORTES, S.A.B. DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 64,021,251 | 0.76 | 3 | 4.63% | plus | 0.2000% |

| GRUPO AEROPORTUARIO DEL CENTRO NORTE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 2,700,000,000 | 1.91 | 3 | 4.63% | plus | 0.8937% |

| GRUPO AEROPORTUARIO DEL PACIFICO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 13,800,000,000 | 2.88 | 6 | 4.63% | plus | 0.3896% |

| GRUPO AEROPORTUARIO DEL SURESTE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 4,650,000 | 4.57 | 2 | 4.63% | plus | 1.3201% |

| GRUPO GICSA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 4,429,347,000 | 4.70 | 6 | 4.63% | plus | 4.3734% |

| GRUPO MEXICANO DE DESARROLLO, S.A.B. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 65,973,515,000 | 1.46 | 5 | 4.63% | plus | 3.0532% |

| GRUPO TMM, S.A. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 80,000,000 | 0.53 | 5 | 4.63% | plus | 5.1000% |

| GRUPO TRAXIÓN S.A.B DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 3,781,444,000 | 0.51 | 8 | 4.63% | plus | 1.9375% |

| IMPULSORA DEL DESARROLLO Y EL EMPLEO EN AMERICA LATINA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 12,794,493,000 | 8.94 | 7 | 4.63% | plus | 3.6730% |

| ORBIA ADVANCE CORPORATION, S.A.B. DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 985,533,730 | 0.50 | 1 | 4.63% | plus | 0.5500% |

| PROMOTORA AMBIENTAL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 2,254,589,000 | 0.48 | 4 | 4.63% | plus | 1.4400% |

| SERVICIOS CORPORATIVOS JAVER, S.A.B. DE C.V. | INDUSTRIAL | Mexican pesos | 2,521,292,000 | 2.49 | 1 | 4.63% | plus | 7.7500% |

| CEMEX, S.A.B. DE C.V. | MATERIALS | Mexican pesos | 1,480,846,434 | 3.76 | 4 | 4.63% | plus | 2.2268% |

| COMPAÑIA MINERA AUTLAN, S.A.B. DE C. V. | MATERIALS | Mexican pesos | 2,806,123 | 5.29 | 4 | 4.63% | plus | 4.3163% |

| CONVERTIDORA INDUSTRIAL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | MATERIALS | Mexican pesos | 364,600,000 | 1.70 | 16 | 4.63% | plus | 2.7500% |

| CYDSA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | MATERIALS | Mexican pesos | 2,750,722,965 | 10.19 | 1 | 4.66% | plus | 2.5000% |

| G COLLADO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | MATERIALS | Mexican pesos | 173,649,000 | 0.11 | 1 | 4.63% | plus | 4.3633% |

| GRUPO CARSO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | MATERIALS | Mexican pesos | 3,500,000,000 | 2.25 | 1 | 4.63% | plus | 0.2150% |

| GRUPO KUO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | MATERIALS | Mexican pesos | 711,462,018 | 1.59 | 2 | 4.66% | plus | 1.5997% |

| GRUPO POCHTECA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | MATERIALS | Mexican pesos | 1,975,000,000 | 2.46 | 2 | 4.63% | plus | 3.6651% |

| MINERA FRISCO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | MATERIALS | Mexican pesos | 7,350,086,000 | 2.81 | 1 | 4.66% | plus | 2.5590% |

| PROTEAK UNO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | MATERIALS | Mexican pesos | 775,096,000 | 1.39 | 3 | 1.29% | plus | 4.5918% |

| ARCA CONTINENTAL | PRODUCTS OF FREQUENT CONSUMPTION | Mexican pesos | 12,296,941 | 3.23 | 9 | 4.65% | plus | 0.3239% |

| FOMENTO ECONÓMICO MEXICANO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | PRODUCTS OF FREQUENT CONSUMPTION | Mexican pesos | 5,662,000,000 | 3.47 | 3 | 4.63% | plus | 0.1066% |

| GRUMA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | PRODUCTS OF FREQUENT CONSUMPTION | Mexican pesos | 1,049,585,100 | 0.54 | 2 | 4.63% | plus | 0.2195% |

| GRUPO BIMBO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | PRODUCTS OF FREQUENT CONSUMPTION | Mexican pesos | 35,499,743,281 | 3.04 | 2 | 4.63% | plus | 0.9500% |

| GRUPO COMERCIAL CHEDRAUI, S.A.B. DE C.V. | PRODUCTS OF FREQUENT CONSUMPTION | Mexican pesos | 17,567,538,000 | 3.25 | 6 | 4.63% | plus | 1.4558% |

| GRUPO GIGANTE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | PRODUCTS OF FREQUENT CONSUMPTION | Mexican pesos | 8,968,888 | 4.86 | 6 | 4.63% | plus | 2.4681% |

| GRUPO HERDEZ, S.A.B. DE C.V. | PRODUCTS OF FREQUENT CONSUMPTION | Mexican pesos | 3,500,000,000 | 0.54 | 7 | 4.66% | plus | 1.2300% |

| GRUPO MINSA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | PRODUCTS OF FREQUENT CONSUMPTION | Mexican pesos | 99,903,500 | 2.15 | 7 | 4.63% | plus | 2.7737% |

| INDUSTRIAS BACHOCO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | PRODUCTS OF FREQUENT CONSUMPTION | Mexican pesos | 1,500,000,000 | 3.44 | 1 | 4.63% | plus | 0.3100% |

| KIMBERLY - CLARK DE MEXICO S.A.B. DE C.V. | PRODUCTS OF FREQUENT CONSUMPTION | Mexican pesos | 6,000,000,000 | 3.20 | 2 | 4.63% | plus | 0.3653% |

| ORGANIZACIÓN CULTIBA, S.A.B. DE CV | PRODUCTS OF FREQUENT CONSUMPTION | Mexican pesos | 751,670,000 | 2.95 | 6 | 4.63% | plus | 2.4913% |

| ORGANIZACION SORIANA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | PRODUCTS OF FREQUENT CONSUMPTION | Mexican pesos | 8,537,500,000 | 1.82 | 4 | 4.63% | plus | 0.5487% |

| GENOMMA LAB INTERNACIONAL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | HEALTH | Mexican pesos | 97,789,821,693 | 2.01 | 20 | 4.63% | plus | 1.0621% |

| MEDICA SUR, S.A.B. DE C.V. | HEALTH | Mexican pesos | 1,200,082,766 | 1.60 | 2 | 4.63% | plus | 2.2481% |

| EL PUERTO DE LIVERPOOL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | NON-COMMODITY GOODS AND SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 1,500,000,000 | 0.67 | 1 | 4.63% | plus | 0.2500% |

| GRUPO ELEKTRA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | NON-COMMODITY GOODS AND SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 13,079,861,000 | 0.75 | 10 | 4.63% | plus | 2.3412% |

| GRUPO VASCONIA S.A.B. | NON-COMMODITY GOODS AND SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 144,825,000 | 1.30 | 1 | 4.63% | plus | 2.9000% |

| GRUPE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | NON-COMMODITY GOODS AND SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 1,365,019,000 | 7.32 | 3 | 4.63% | plus | 3.2957% |

| AMERICA MOVIL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | TELECOMMUNICATIONS SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 34,080,000,000 | 0.51 | 10 | 4.93% | plus | 0.3151% |

| AXTEL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | TELECOMMUNICATIONS SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 3,204,745,000 | 5.50 | 2 | 4.63% | plus | 2.0958% |

| GRUPO RADIO CENTRO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | TELECOMMUNICATIONS SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 711,445,000 | 5.45 | 6 | 4.63% | plus | 3.6212% |

| GRUPO TELEVISA, S.A.B. | TELECOMMUNICATIONS SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 17,935,404,000 | 0.47 | 4 | 4.63% | plus | 1.2643% |

| MEGACABLE HOLDINGS, S.A.B. DE C.V. | TELECOMMUNICATIONS SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 6,823,407,000 | 0.58 | 4 | 4.63% | plus | 0.2800% |

| TV AZTECA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | TELECOMMUNICATIONS SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 5,708,000,000 | 3.22 | 4 | 4.63% | plus | 2.7405% |

| ALSEA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | NON-COMMODITY GOODS AND SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 564,645,163 | 1.95 | 2 | 4.63% | plus | 1.8474% |

| CMR, S.A.B. DE C.V. | NON-COMMODITY GOODS AND SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 1,141,234,000 | 3.33 | 1 | 4.63% | plus | 4.2975% |

| CORPORACION INTERAMERICANA DE ENTRETENIMIENTO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | NON-COMMODITY GOODS AND SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 850,000,000 | 0.31 | 4 | 4.63% | plus | 2.6559% |

| GRUPO FAMSA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | NON-COMMODITY GOODS AND SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 4,528,800,000 | 0.66 | 7 | 4.63% | plus | 2.8286% |

| GRUPO HOTELERO SANTA FE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | NON-COMMODITY GOODS AND SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 343,148,000 | 2.95 | 2 | 4.63% | plus | 3.0000% |

| GRUPO PALACIO DE HIERRO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | NON-COMMODITY GOODS AND SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 1,430,000 | 0.86 | 2 | 4.63% | plus | 0.0209% |

| GRUPO SPORTS WORLD, S.A.B. DE C.V. | NON-COMMODITY GOODS AND SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 1,789,362 | 0.76 | 2 | 4.63% | plus | 1.7221% |

| HOTELES CITY EXPRESS, S.A.B. DE C.V. | NON-COMMODITY GOODS AND SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 5,101,196,000 | 3.42 | 18 | 4.63% | plus | 3.3372% |

| NEMAK, S.A.B. DE C.V. | NON-COMMODITY GOODS AND SERVICES | Mexican pesos | 3,788,000,000 | 7.10 | 1 | 4.63% | plus | 2.7000% |

| Company | DRSK 1 year | DRSK 2 years | Bloomberg Credit Spread | EDF 1 year | K.M.V. Moody's |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VISTA OIL & GAS, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.224800% | 0.972400% | 2.46% | 3.02% | B1.edf |

| ACCEL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.000000% | 0.000500% | 0.92% | 3.02% | B1.edf |

| ACOSTA VERDE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.5221% | 1.4000% | 2.75% | 1.98% | Ba3.edf |

| ALEATICA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.4825% | 2.1100% | 2.82% | 1.67% | Ba1.edf |

| ALFA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.2673% | 0.9893% | 2.67% | 2.02% | Baa3.edf |

| CONSORCIO ARA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0260% | 0.2586% | 2.24% | 1.67% | Ba2.edf |

| CONSORCIO ARISTOS, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 1.5500% | 3.3800% | 3.15% | 35.00% | Caa-C.edf |

| CORPOVAEL S.A.B. DE C.V. | 1.6600% | 4.5500% | 3.27% | 7.58% | B3.edf |

| DINE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0000% | 0.0003% | 0.71% | 3.02% | B1.edf |

| GMÉXICO TRANSPORTES, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.7874% | 2.3300% | 2.76% | 3.02% | B1.edf |

| GRUPO AEROPORTUARIO DEL CENTRO NORTE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0012% | 0.0504% | 1.47% | 6.71% | B3.edf |

| GRUPO AEROPORTUARIO DEL PACIFICO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0120% | 0.1699% | 1.83% | 0.37% | Baa1.edf |

| GRUPO AEROPORTUARIO DEL SURESTE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0008% | 0.0376% | 1.56% | 6.71% | B3.edf |

| GRUPO GICSA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 3.7100% | 5.9300% | 3.31% | 1.67% | Ba2.edf |

| GRUPO MEXICANO DE DESARROLLO, S.A.B. | 0.3472% | 1.1600% | 2.55% | 3.02% | B2.edf |

| GRUPO TMM, S.A. | 0.5808% | 1.9000% | 2.56% | 6.71% | B3.edf |

| GRUPO TRAXIÓN S.A.B DE C.V. | 0.2951% | 1.1800% | 2.38% | 3.02% | B1.edf |

| IMPULSORA DEL DESARROLLO Y EL EMPLEO EN AMERICA LATINA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0045% | 0.1157% | 1.66% | 4.35% | B2.edf |

| ORBIA ADVANCE CORPORATION, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.2143% | 0.8712% | 2.39% | 0.98% | Ba1.edf |

| PROMOTORA AMBIENTAL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0006% | 0.0262% | 1.37% | 1.67% | Ba2.edf |

| SERVICIOS CORPORATIVOS JAVER, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0000% | 0.0000% | 0.39% | 35.00% | Caa-C.edf |

| CEMEX, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.5300% | 1.7500% | 2.71% | 0.93% | Ba1.edf |

| COMPAÑIA MINERA AUTLAN, S.A.B. DE C. V. | 0.0057% | 0.1013% | 1.87% | 6.71% | B3.edf |

| CONVERTIDORA INDUSTRIAL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0000% | 0.0003% | 0.74% | 0.37% | Baa1.edf |

| CYDSA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0127% | 0.1903% | 2.17% | 3.52% | Ba2.edf |

| G COLLADO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0426% | 0.3397% | 2.33% | 6.71% | B3.edf |

| GRUPO CARSO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0325% | 0.3485% | 2.20% | 0.37% | Baa1.edf |

| GRUPO KUO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0001% | 0.0147% | 1.41% | 0.98% | Ba1.edf |

| GRUPO POCHTECA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0140% | 0.1857% | 1.79% | 3.02% | B3.edf |

| MINERA FRISCO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.3140% | 1.1300% | 2.48% | 0.37% | Baa1.edf |

| PROTEAK UNO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.9781% | 2.7900% | 2.69% | 6.71% | B3.edf |

| ARCA CONTINENTAL | 0.0005% | 0.0292% | 1.66% | 0.37% | Baa1.edf |

| FOMENTO ECONÓMICO MEXICANO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0001% | 0.0133% | 1.42% | 0.37% | Baa1.edf |

| GRUMA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0330% | 0.3536% | 2.39% | 0.37% | Baa1.edf |

| GRUPO BIMBO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0270% | 0.2851% | 2.34% | 0.38% | Baa2.edf |

| GRUPO COMERCIAL CHEDRAUI, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0131% | 0.1813% | 2.18% | 6.71% | B3.edf |

| GRUPO GIGANTE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0011% | 0.0505% | 1.60% | 3.02% | B1.edf |

| GRUPO HERDEZ, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.1376% | 0.7592% | 2.71% | 4.35% | B2.edf |

| GRUPO MINSA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0005% | 0.0444% | 1.57% | 1.98% | Ba3.edf |

| INDUSTRIAS BACHOCO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0001% | 0.0141% | 1.42% | 0.37% | Baa1.edf |

| KIMBERLY - CLARK DE MEXICO S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0000% | 0.0030% | 1.08% | 0.37% | Baa1.edf |

| ORGANIZACIÓN CULTIBA, S.A.B. DE CV | 0.0006% | 0.0671% | 1.62% | 0.37% | Baa1.edf |

| ORGANIZACION SORIANA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0029% | 0.0814% | 1.86% | 0.98% | Ba1.edf |

| GENOMMA LAB INTERNACIONAL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0431% | 0.3651% | 2.23% | 3.02% | B1.edf |

| MEDICA SUR, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.4348% | 1.7100% | 2.78% | 4.35% | B2.edf |

| EL PUERTO DE LIVERPOOL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0000% | 0.0040% | 1.06% | 0.37% | Baa1.edf |

| GRUPO ELEKTRA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0031% | 0.1278% | 1.50% | 3.02% | B1.edf |

| GRUPO VASCONIA S.A.B. | 2.4100% | 4.4300% | 3.21% | 3.02% | B1.edf |

| GRUPE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0000% | 0.0000% | 0.42% | 1.98% | Ba3.edf |

| AMERICA MOVIL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0133% | 0.1824% | 1.49% | 0.48% | Baa2.edf |

| AXTEL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 3.7300% | 6.5100% | 2.50% | 4.35% | B2.edf |

| GRUPO RADIO CENTRO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0000% | 0.0000% | 0.28% | 6.71% | B3.edf |

| GRUPO TELEVISA, S.A.B. | 0.6507% | 2.2900% | 1.99% | 1.98% | Ba3.edf |

| MEGACABLE HOLDINGS, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0072% | 0.1325% | 1.32% | 0.37% | Baa1.edf |

| TV AZTECA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 4.0800% | 5.7600% | 2.50% | 35.00% | Caa-C.edf |

| ALSEA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.1980% | 0.8646% | 2.70% | 3.02% | B1.edf |

| CMR, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 1.8000% | 3.0600% | 3.13% | 2.02% | Baa3.edf |

| CORPORACION INTERAMERICANA DE ENTRETENIMIENTO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0000% | 0.0032% | 0.91% | 3.02% | Baa3.edf |

| GRUPO FAMSA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 14.3000% | 16.0700% | 4.10% | 35.00% | Caa-C.edf |

| GRUPO HOTELERO SANTA FE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0378% | 0.3362% | 2.23% | 3.02% | B1.edf |

| GRUPO PALACIO DE HIERRO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.0000% | 0.0000% | 0.38% | 0.37% | Baa1.edf |

| GRUPO SPORTS WORLD, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 7.5300% | 10.5500% | 3.57% | 3.20% | B1.edf |

| HOTELES CITY EXPRESS, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.5782% | 2.1200% | 2.89% | 6.71% | B3.edf |

| NEMAK, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 0.2963% | 1.0000% | 2.68% | 3.20% | B1.edf |

| MAX BLOOMBERG Y MOODY'S ( FAMSA) | 14.300% | 16.070% | 4.100% | 35.000% | |

| MIN BLOOMBERG Y MOODY'S (PALACIO DE HIERRO) | 0.000% | 0.000% | 0.280% | 0.370% | |

| AVERAGE | 0.765% | 1.433% | 2.052% | 4.777% | |

| CORRELATION BETWEEN DRSK 1 YEAR VS.EDF I YEAR | 51% | ||||

| CORRELATION BETWEEN EDF 1 YEAR AND DEBT COST CALCULATED BY BLOOMBERG | 55% | ||||

| CORRELATION BETWEEN DRSK 1 YEAR AND DEBT COST CALCULATED BY BLOOMBERG | 20% |

| Bloomberg | Merton | BM | PLBM | Modified Merton |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G Value | -0.174 | -2.16 | -13.105 | 0.504 | 0.767 |

| Market Value of Equity multiplied by the proportion of debts referenced to a base rate. | Merton's Modified Model Value of Firm | Traditional Merton's Model Value of Firm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VISTA OIL & GAS, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 3,204,369,379 | 4,094,440,938 | 4,108,397,401 |

| ACCEL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 70,795,633 | 1,515,398,832 | 1,510,882,175 |

| ACOSTA VERDE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 4,174,491,988 | 5,359,702,736 | 5,390,721,949 |

| ALEATICA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 4,412,626,304 | 19,198,159,763 | 18,777,304,633 |

| ALFA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 16,888,265 | 82,834,452 | 75,975,063 |

| CONSORCIO ARA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 376,566,920 | 1,215,757,837 | 1,463,895,025 |

| CONSORCIO ARISTOS, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 336,223,889 | 647,612,247 | 565,460,656 |

| CORPOVAEL S.A.B. DE C.V. | 5,621,705,400 | 10,211,457,528 | 10,024,864,591 |

| DINE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 366,936,262 | 681,112,143 | 685,448,591 |

| GMÉXICO TRANSPORTES, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 9,573,368 | 86,825,181 | 86,468,867 |

| GRUPO AEROPORTUARIO DEL CENTRO NORTE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 1,084,426,658 | 4,713,813,946 | 4,679,892,238 |

| GRUPO AEROPORTUARIO DEL PACIFICO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 52,297,228,499 | 91,120,045,883 | 90,885,409,863 |

| GRUPO AEROPORTUARIO DEL SURESTE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 27,154,255 | 50,608,933 | 50,682,460 |

| GRUPO GICSA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 2,307,649,642 | 14,836,771,752 | 14,590,502,079 |

| GRUPO MEXICANO DE DESARROLLO, S.A.B. | 659,782,574 | 85,512,291,351 | 79,304,549,758 |

| GRUPO TMM, S.A. | 11,962,738 | 149,367,099 | 119,400,933 |

| GRUPO TRAXIÓN S.A.B DE C.V. | 6,750,049,962 | 16,585,294,238 | 12,408,855,277 |

| IMPULSORA DEL DESARROLLO Y EL EMPLEO EN AMERICA LATINA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 74,218,739,600 | 210,947,833,546 | 202,277,465,837 |

| ORBIA ADVANCE CORPORATION, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 13,675,282,346 | 15,380,978,496 | 15,391,528,072 |

| PROMOTORA AMBIENTAL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 1,012,278,749 | 3,884,407,934 | 3,664,320,211 |

| SERVICIOS CORPORATIVOS JAVER, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 1,663,862,470 | 5,510,378,938 | 5,572,151,511 |

| CEMEX, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 9,573,046,550 | 17,441,427,463 | 17,412,842,226 |

| COMPAÑIA MINERA AUTLAN, S.A.B. DE C. V. | 194,162,679 | 16,021,317,720 | 332,679,524 |

| CONVERTIDORA INDUSTRIAL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 90,424,438 | 511,035,949 | 511,617,569 |

| CYDSA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 1,262,474,450 | 12,890,929,557 | 12,522,098,956 |

| G COLLADO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 993,957,189 | 1,178,758,084 | 1,179,043,858 |

| GRUPO CARSO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 7,265,439,986 | 16,021,317,720 | 16,021,317,720 |

| GRUPO KUO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 210,958,856 | 1,364,007,530 | 1,218,098,575 |

| GRUPO POCHTECA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 145,109,485 | 19,001,717,935 | 2,778,199,366 |

| MINERA FRISCO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 5,218,340,679 | 17,726,200,951 | 17,425,021,074 |

| PROTEAK UNO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 1,630,292,378 | 3,080,664,077 | 2,977,257,083 |

| ARCA CONTINENTAL | 25,948,655 | 53,678,868 | 52,858,416 |

| FOMENTO ECONÓMICO MEXICANO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 4,845,019,144 | 14,962,279,256 | 14,694,998,128 |

| GRUMA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 36,743,809,015 | 39,699,333,879 | 39,706,627,231 |

| GRUPO BIMBO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 41,978,149,087 | 106,304,630,890 | 102,354,542,194 |

| GRUPO COMERCIAL CHEDRAUI, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 6,614,018,439 | 34,076,733,248 | 34,134,335,048 |

| GRUPO GIGANTE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 9,928,029 | 30,357,513 | 30,526,314 |

| GRUPO HERDEZ, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 5,976,931,305 | 12,087,429,492 | 10,722,916,842 |

| GRUPO MINSA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 173,333,533 | 328,648,774 | 321,952,993 |

| INDUSTRIAS BACHOCO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 3,695,120,296 | 7,325,738,731 | 7,349,128,005 |

| KIMBERLY - CLARK DE MEXICO S.A.B. DE C.V. | 13,287,374,553 | 36,864,413,917 | 28,910,749,020 |

| ORGANIZACIÓN CULTIBA, S.A.B. DE CV | 389,146,248 | 1,575,794,781 | 1,563,252,455 |

| ORGANIZACION SORIANA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 1,553,836,356 | 12,284,054,074 | 11,843,481,628 |

| GENOMMA LAB INTERNACIONAL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 11,525,792,193 | 21,166,453,135 | 20,833,698,941 |

| MEDICA SUR, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 3,135,268,077 | 4,942,545,502 | 4,873,866,279 |

| EL PUERTO DE LIVERPOOL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 1,750,533,577 | 3,497,437,585 | 3,497,560,759 |

| GRUPO ELEKTRA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 14,129,648,854 | 28,042,057,105 | 28,060,114,726 |

| GRUPO VASCONIA S.A.B. | 119,639,220 | 307,458,765 | 303,848,523 |

| GRUPE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 874,786,166 | 4,191,961,636 | 3,827,468,979 |

| AXTEL, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 2,605,355,905 | 12,246,999,368 | 12,106,684,412 |

| GRUPO RADIO CENTRO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 303,409,575 | 2,223,974,452 | 1,982,372,196 |

| GRUPO TELEVISA, S.A.B. | 9,937,231,783 | 29,043,072,558 | 30,864,849,971 |

| MEGACABLE HOLDINGS, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 43,799,145,112 | 53,770,289,727 | 53,756,011,475 |

| TV AZTECA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 2,175,351 | 7,853,857,310 | 7,864,508,956 |

| ALSEA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 236,297,064 | 909,368,794 | 966,182,735 |

| CMR, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 342,786,454 | 1,899,382,295 | 1,783,612,196 |

| CORPORACION INTERAMERICANA DE ENTRETENIMIENTO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 730,475,438 | 1,629,356,797 | 1,628,826,733 |

| GRUPO FAMSA, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 137,096,822 | 9,160,107,202 | 6,937,247,893 |

| GRUPO HOTELERO SANTA FE, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 210,334,518 | 1,117,108,020 | 919,304,660 |

| GRUPO PALACIO DE HIERRO, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 1,095,540 | 2,739,388 | 2,728,061 |

| GRUPO SPORTS WORLD, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 9,626,767 | 13,643,775 | 12,575,700 |

| HOTELES CITY EXPRESS, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 1,382,992,127 | 10,005,621,965 | 9,696,004,717 |

| NEMAK, S.A.B. DE C.V. | 1,067,967,384 | 7,028,423,000 | 8,060,551,072 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).