1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized pathologically by neuronal loss and aggregation of Aβ and tau proteins, and clinically by a gradual loss of memory and impairment of cognitive ability. The predominant form of AD is late-onset (LOAD, age onset over 65 years), which can be familial (15% to 20%) or sporadic. The pathophysiology of the disease is complex and, although several genomic loci and risk-enhancing genetic variants have been determined, the ε4 allele of apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene and increasing age remain two of the most important known risk factors for the disease development.

Affecting millions of people worldwide, LOAD represents one of the commonest causes of dementia in the elderly and a serious public health problem [

1]. So, understanding of the underlying bio-pathological factors and biomarkers with prognostic significance is warranted.

Telomeres are complex nucleoprotein structures at the tip of chromosomes that protect the ends of chromosomes from fusion and degradation, thus preserving the genome stability of the cells.

Accumulating evidence revealed that leukocyte telomere length (LTL) reduction can be regarded as a critical cellular hallmark of biological aging, being telomere shortening associated with overall mortality and increased rates of age-related disorders [

2], including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cancers [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Several studies examined the association between LTL and LOAD, although with controversial results. While some case-control and meta-analysis studies found significantly shorter telomeres in individuals with LOAD than in healthy controls [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17], others have not found such association [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Also, a long-term longitudinal study by Fani and co-workers [

22] reported a U-shaped association, suggesting both short and long LTL as risk factor for AD. A non-linear association was also found between LTL and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [

23].

In addition, it was reported that subjects with mild cognitive impairment that evolved into AD have longer LTL than those with stable mild cognitive impairment [

21].

Overall, these results indicate that the association between LTL and LOAD is complex and requires additional investigation to untangle, also considering the importance that LTL may have as biomarker with potential diagnostic and prognostic value in the assessment of patients with LOAD.

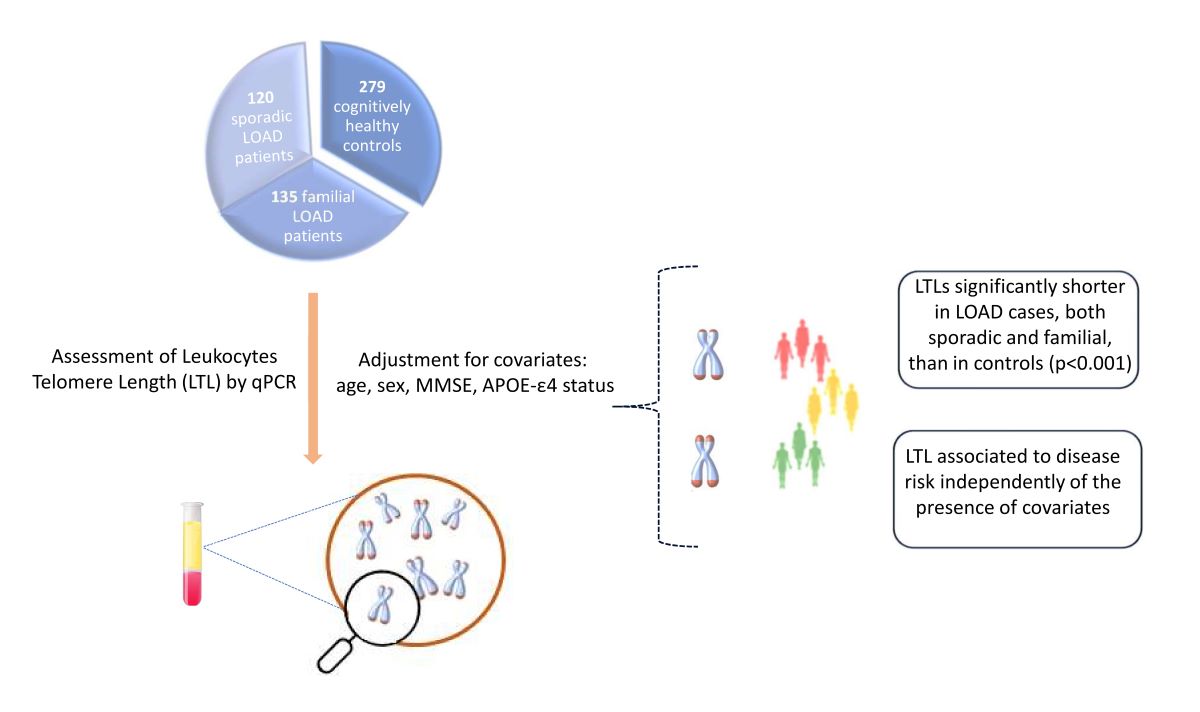

Thus, in this study we measured and compared LTL among two groups of patients clinically diagnosed as LOAD, sporadic cases and patients who had a positive family history for LOAD, and a group of age-matched cognitively healthy control subjects to better elucidate the relationship between LTL and AD risk.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

The sample analyzed was composed by 534 subjects from Calabria (Southern Italy) including 255 patients with LOAD (95 men and 160 women; mean ages 77.41±2.80) and 279 unrelated healthy controls (147 men and 132 women; mean ages 73.67±5.49). To avoid population stratification effects, only subjects with at least two generations of ancestors from the Calabria region were included in this study.

The control subjects were recruited during several campaigns focused on monitoring the quality of aging in Calabria as previously reported [

24]. Attention was paid to match cases and controls for age, ethnicity, and origin in the area. All subjects were carefully assessed using a rigorous clinical history evaluation and a general/neurological examination, to include/exclude the presence of any neurological disorder. Cognitive status was investigated through Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) [

25].

MMSE scores were adjusted for age and educational level according to procedure reported by Magni and coworkers [

26].

The patients were recruited at the Regional Neurogenetics and clinically diagnosed as having LOAD based on the criteria of the National Institute on Aging, and the Alzheimer’s Association workgroup were used to perform the clinical diagnosis for AD [

27]. McKeith criteria [

28], clinical and neuropathological criteria for frontotemporal dementia [

29], and NINDSAIREN criteria [

30] were used to differentiate Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and vascular dementia from AD.

The LOAD sample was further subdivided into sporadic (N = 120 subjects) and familial (N = 135 subjects) cases: if LOAD was diagnosed in one patient without further members of the family affected, the case was defined as “sporadic”. On the contrary, if LOAD was diagnosed in a subject who had a positive family history for LOAD, the case was defined as “familial”. In such a case, a sole affected subject per family was randomly selected for the study.

2.2. Ethics statement.

Investigation has been conducted in accordance with the ethical standards established in the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the authors’ institutional review board. Before the visit, each subject or, where appropriate, a relative or legal representative signed an informed consent for the permission to usage of register-based information, and to collect blood samples from which extract genomic DNA for research purposes.

2.3. Leukocyte telomere length (LTL)

The average length of telomeres was measured by RealTime PCR quantitative analysis (qPCR), by using an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio3 device in 96-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). This method allows to measure the number of copies of telomeric repeats (T) compared to a single copy gene (S) used as a quantitative control [

31]. We applied the modified protocol described by Testa and colleagues [

32]. For the PCR reaction, 5 µl of DNA with a concentration of 3 ng/µl (15 ng in total) and 15µl of mix was added in each well. Using the concentrations reported by Testa et al. [

32] two mixes were prepared: one containing the PCR reagents, the SYBR green dye for the detection of the fluorescence and the specific primers for telomeres (T) and another containing the PCR reagents, the SYBR green dye and the specific primers for 36B4, used as control gene (S). In addition, two standard curves (one for 36B4 and one for telomere reactions) were prepared for each plate by using a reference DNA sample (Roche, Milano, Italy) diluted in series by 1.68-fold per dilution to produce 6 concentrations of DNA ranging from 30 to 2 ng in 5µl. A calibrator sample (Roche, Milano, Italy) (5 µl of 3ng/µl) was included in each plate for both telomere and 36B4. The thermal cycle profile was the one reported by Testa [

32]. To reduce inter-assay variability the telomere and single-copy gene (36B4) were analyzed on the same plate. R2 and amplification efficiencies varied between 0.984 and 0.997, and 94.8 to 107.5%, respectively. More than 20% of samples were blindly replicated on different plates to assess T/S measurement reproducibility. The inter assay coefficient of variation was < 7.8%. Measurements were performed in triplicate and reported as T⁄S ratio relative to the calibrator sample to allow comparison across runs.

2.4. APOE genotyping

The two missense SNPs in exon 4, i.e., rs429358 at codon 112 and rs7412 at codon 158, which determine the genotype of APOE for ε2, ε3, and ε4 protein isoforms, were genotyped according to the protocol described in Carrieri et al. [

33].

2.5. Statistical analyses

Kolmogrov-Simirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were used to verify the normal distribution of variables. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SDs while categorical variables as percentages. Differences between groups were evaluated using Mann-Whitney U test and Pearson’s chi-square test, for continuous and categorical values, respectively. Statistical comparisons among groups were performed by using one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s test.

Linear regression analysis was run to assess any significant associations between telomere length and individual predictors, including age, age at onset, sex, MMSE score and APOE status. Association between telomere length and LOAD was then assessed by forward stepwise multivariate logistic regression analyses while considering potential confounders.All statistical data were analyzed by the SPSS software version 28.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

3. Results

To investigate the contribution of leucocytes telomere length (LTL) to the risk of late-onset Alzheimer disease (LOAD), LTL, expressed as T/S ratio, was measured in a cohort of 255 unrelated patients with sporadic (sLOAD, 120 subjects) or familial (fLOAD, 135 patients) LOAD, and a similarly aged cohort of 279 cognitively normal controls. Characteristics of the samples are given in

Table 1.

As shown in

Figure 1 the mean log-transformed LTL (logT/S ratio) in controls (-0.089, SE 0.016) was significantly higher than that in sLOAD patients (-0.32, SE 0.017, P < 0.001), a difference that equates to about 48 % decrease in the T/S ratio. Similarly, the mean logT/S ratio in controls was significantly higher than in fLOAD patients (-0.32, SE 0.019, P < 0.001), a difference that equates to a 41 % decrease in the T/S ratio. No difference was observed in mean LTL between the two group of patients (P=0.05.

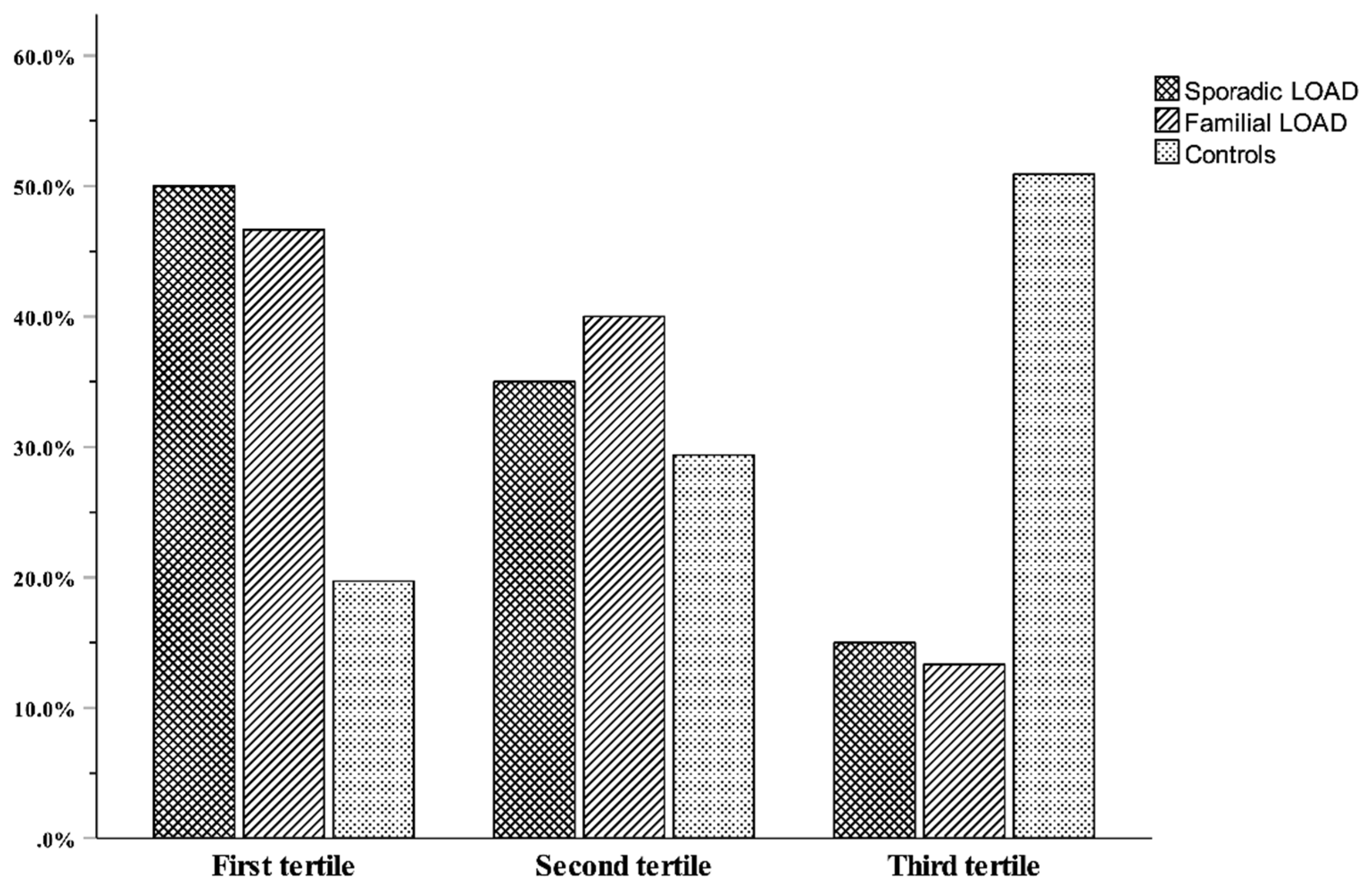

To better illustrate the telomere-LOAD relationship, the distributions of the logT/S ratio were categorized into tertiles constructed using the combined case–control group with the age adjustment made within the separate groups. First and third tertiles represent the shortest and longest telomeres, respectively. The range and mean values of logT/S ratio in each tertile group are shown in

Figure 2, which also shows the proportion of cases and controls across tertiles. As this Figure shows, with respect to controls, a significantly higher proportion of LOAD patients were in the first tertile, while, on the contrary, a lower proportion were in third tertile (p <0.001).

Linear regression analyses were performed, within each of the LOAD and control groups separately, to investigate the potential contribution of parameters reported in

Table 1 to variation in LTL. We found a significant negative relationship between logT/S ratio and age in the control group (β = -0.133, p = 0.027), while no significant relationship was observed between LTL and age in either subgroup of patients (β = -0.032, p=0.73 for sLOAD and β = -0.014, p=0.87 for fLOAD). No significant association with sex, age of disease onset, disease severity (as measured by MMSE score), or presence of the APOE-ε4 allele was found in any of the groups analyzed.

Next, we performed logistic regression analyses through a stepwise procedure to better evaluate the link between LTL and disease including confounders in

Table 1. The best model, reported in

Table 2, included all the variables except sex.

The results confirmed that shorter telomeres were significantly associated with increased risk of LOAD, both sporadic and familial LOAD (p<0.001 for both), and that LTL was an independent risk factor for LOAD not confounded by the other risk indicators of disease. Overall, these independent risk factors explained more than 70 percent (see Nagelkerke R2 values in

Table 2) of the total variance in the predictive model performance.

4. Discussion

Telomere shortening is considered a marker of cellular aging, yet its association with dementia, and more specifically with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology, is debated, with mixed results from different studies ranging from no association, negative or positive association, as well as non-linear association [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. These controversial results highlight the need for further investigation to fully understand the role that telomere length variability plays in AD risk. Towards this end, we analyzed a clinical-based series of sporadic and familial unrelated late-onset patients (sLOAD and fLOAD) and a cohort of cognitively normal subjects, all from a region of southern Italy (Calabria).

Our findings agree with studies that associate telomere shortening to increasing risk of AD; leukocyte telomere length (LTL) was in fact shorter in LOAD patients, both sLOAD and fLOAD cases, than in controls.

Establishing a causal link between shorter LTL and LOAD risk is particularly challenging. Many of the factors that induce accelerated telomere shortening, such as inflammation, oxidative stress, and immune function, have been implicated in LOAD. It is likely that all are in a vicious cycle, and one feeds the other. The link between telomere shortening and LOAD has also, in part, been explained by connecting telomere shortening to the mechanisms controlling telomere maintenance. Wang and co-workers [

34] have evidenced that aggregated β-amyloid could inhibit telomerase activity causing telomere shortening. In addition, Spilsbury et al. [

35] reported that neurons expressing high levels of pathological tau did not express TERT protein, which expression has an impact on telomere length.

One additional finding of our study is that LTL was a significant independent risk factor for LOAD after multivariate adjustments for cognition-related confounders such as age, sex, MMSE score, and APOE status. The extant literature to this regard is inconclusive. Takata et al. [

20] found that patients that are homozygous for APOE-ε4 have significantly shorter LTL than those with only one or no copies of APOE-ε4, a finding like that of Dhillon et al. [

36] who reported telomeres significantly shorter in APOE-ε4 carriers compared with non-APOE-ε4 carriers. On the other hand, Hackenhaar and co-workers [

37] reported the association between short TL and a higher risk of AD in APOE non- ε4 carriers only, while Wikgren et al. [

16] found that nondemented APOE-ε4 carriers had longer telomeres but a higher attrition rate compared to non-carriers. Differing from these studies, we did not detect any significant relationship between LTL and the presence of the APOE-ε4 allele in none of the analysed cohorts. We also did not find significant correlation between cognitive performance (MMSE) and LTL, which agrees with some [

38,

39] but differs from other published studies [

40,

41,

42] which report both shorter and longer telomeres associated with cognitive decline or increased rate of conversion to dementia in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a condition that can be a precursor to AD.

The lack of consistency across studies, regarding both the association between LTL with the disease and its relationship with other disease risk factors, likely arises from variability in methodologies (study design, inclusion criteria, in cell/tissue type examined and measurement techniques), as well as differences in the ancestry of the populations studied. We want to point out that the three cohort of subjects evaluated in the present study have some important homogeneity features. First, all subjects were collected in a population (Calabria, a region from south Italy) characterized by a high level of genetic homogeneity due to the geographical and historical isolation of the region until recent years, and therefore population stratification, which is a significant confounding factor and potential source of spurious associations, is limited. Second, a team of specialists like neurologists, neuropsychologists, and geriatricians carried out a huge effort to exactly define homogeneous phenotypes (for example, the distinction between sporadic and familial LOAD). Third, the group of controls was matched with cases for ethnicity, genetic origin, sex, and age, and, most importantly, the same neuropsychological tests used for cases were applied to the whole control sample to exclude the presence of latent forms of dementia. We are therefore confident that the hint emerging from our data that shorter telomeres per se could be a risk factor for the development of LOAD, or in any case a biomarker of the disease, is quite robust. We considered two alternative interpretations of the independent effect of LTL on LOAD: LTL may be associated with other risk factors for LOAD development not considered in this report; those persons with shorter telomers may be more prone to develop the disease. It is interesting to underline on this regard that a finding from our study was a significant inverse correlation between LTL and chronological age in the control group but no correlation with patient age in both LOAD cohorts’, although mean age was comparable across groups. This could indicate that individuals who develop LOAD inherently have shorter LTL that predisposes them to the disease in these individuals, further physiological telomere shortening would lead to the death of cells with excessively short telomeres, thus reducing age-related LTL variability in these subjects. Alternatively, it could be that in patients the rate of telomere attrition caused by the disease status, for instance the LOAD-related increased oxidative stress and inflammation, which are among the main factors favoring telomere attrition, is significant enough to mask the contribution of the gradual shortening of telomeres that normally occurs during aging.

The limitations of our study must be considered when assessing our findings. First, we measured telomere length in leukocytes in blood, which may not be representative of telomere length in the brain although some studies reported that telomere length in leukocytes is strongly correlated with that in the cerebellum of AD patients [

43]. Second, its retrospective design, unlike the longitudinal design, does not allow to figure out whether shorter telomeres in LOAD are a cause or rather a consequence of the disease as well as determining whether there is a relationship between LTL and disease progression. Third, we did not collect additional information about variables, both biological and environmental (e.g., Aβ levels, unhealthy lifestyle factors), that could prove relevant to the results.

5. Conclusions

Using two groups of LOAD patients, familial and sporadic cases, in comparison with cognitively healthy controls this study found a significant association between shorter telomere length in leukocytes and the development of LOAD. Thus, our results further support the possibility that LTL may be important in the pathogenesis of this clinical entity. However, further investigations, possibly with a longitudinal design, are needed to recognize shorter LTL as good predictive or diagnostic markers in the assessment of the disease.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.R. and P.C.; methodology, P.C., S.D., and R.L.G.; formal analysis, G.R., and F.D.R.; writing—original draft preparation, G.R.; writing—review and editing, G.R., P.C., F.D.R., S.D., R.L.G., R.M., A.C.B., and G.P.; visualization, G.R.; funding acquisition, G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by “SI.F.I.PA.CRO.DE.–Sviluppo e industrializzazione farmaci innovativi per terapia molecolare personalizzata PA.CRO.DE.” PON ARS01_00568 granted by MIUR (Ministry of Education, University and Research) Italy to G.P.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the local Ethical Committee (Comitato Etico Regione Calabria-Sezione Area Nord) on 2017–10-31 (code n. 25/2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the study participants or, where appropriate, a relative or legal representative.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge co-funding from Next Generation EU, in the context of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan, Investment PE8 – Project Age-It: “Ageing Well in an Ageing Society”. This resource was co-financed by the Next Generation EU [DM 1557 11.10.2022]. The views and opinions expressed are only those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them. The work has been made possible by the collaboration with Gruppo Baffa (Sadel Spa, Sadel San Teodoro srl, Sadel CS srl, Casa di Cura Madonna dello Scoglio, AGI srl, Casa di Cura Villa del Rosario srl, Savelli Hospital srl, Casa di Cura Villa Ermelinda).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang, X.X.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Z.T.; Ma, Y.H.; Tan, L.; Yu, J.T. The Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s Disease Modifiable Risk Factors and Prevention. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2021, 8, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossiello, F.; Jurk, D.; Passos, J.F.; d’Adda di Fagagna, F. Telomere dysfunction in ageing and age-related diseases. Na Cell Biol 2022, 24, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawthon, R.M.; Smith, K.R.; O’Brien, E.; Sivatchenko, A.; Kerber, R.A. Association between telomere length in blood and mortality in people aged 60 years or older. Lancet 2003, 361, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aviv, A.; Shay, J.W. Reflections on telomere dynamics and ageing-related diseases in humans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2018, 373, 20160436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Ezquerro, J.D.; Rodríguez-Castañeda, A.; Ortiz-Ramírez, M.; Sánchez-García, S.; Rosas-Vargas, H.; Sánchez-Arenas, R.; García-De la Torre, P. Oxidative Stress, Telomere Length, and Frailty in an Old Age Population. Rev Invest Clin 2020, 71, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Wang, S.; Jiao, F.; Kong, Q.; Liu, C.; Wu, Y. Telomere Length: A Potential Biomarker for the Risk and Prognosis of Stroke. Front Neurol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkiadaki, P.; Nikitovic, D.; Kalliantasi, K.; Sarandi, E.; Thanasoula, M.; Stivaktakis, P.; Nepka, C.; Spandidos, D.; Theodoros, T.; Tsatsakis, A. Telomere length and telomerase activity in osteoporosis and osteoarthritis (Review). Exp Ther Med 2019, 19, 1626–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, K.; Seimiya, H. Revisiting Telomere Shortening in Cancer. Cells 2019, 8, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, B.; Gispert, J.D.; Guigo, R.; Navarro, A.; Vilor-Tejedor, N.; Crous-Bou, M. Genetically predicted telomere length and its relationship with neurodegenerative diseases and life expectancy. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2022, 20, 4251–4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Guo, C.; Kong, J. Oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen Res 2012, 7, 376–385. [Google Scholar]

- Boccardi, V.; Arosio, B.; Cari, L.; Bastiani, P.; Scamosci, M.; Casati, M.; Ferri, E.; Bertagnoli, L.; Ciccone, S.; Rossi, P.D.; Nocentini, G.; Mecocci, P. Beta-carotene, telomerase activity and Alzheimer’s disease in old age subjects. Eur J Nutr 2020, 59, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forero, D.A.; González-Giraldo, Y.; López-Quintero, C.; Castro-Vega, L.J.; Barreto, G.E.; Perry, G. Meta-analysis of Telomere Length in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016, 71, 1069–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honig, L.S.; Schupf, N.; Lee, J.H.; Tang, M.X.; Mayeux, R. Shorter telomeres are associated with mortality in those with APOE ϵ4 and dementia. Ann Neurol 2006, 60, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panossian, L.; Porter, V.R.; Valenzuela, H.F.; Zhu, X.; Reback, E.; Masterman, D.; Cummings, J.L.; Effros, R.B. Telomere shortening in T cells correlates with Alzheimer’s disease status. Neurobiol Aging 2003, 24, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarabino, D.; Broggio, E.; Gambina, G.; Corbo, R.M. Leukocyte telomere length in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease patients. Exp Gerontol 2017, 98, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikgren, M.; Karlsson, T.; Nilbrink, T.; Nordfjall, K.; Hultdin, J.; Sleegers, K.; Van Broeckhoven, C.; Nyberg, L. , Roos, G.; Nilsson, L.G.; Adolfsson, R.; Norrback, K.F. APOE epsilon4 is associated with longer telomeres, and longer telomeres among epsilon4 carriers predicts worse episodic memory. Neurobiol Aging 2012, 33, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, S.; Blasco, M.A.; Siedlak, S.L.; Harris, P.L. R.; Moreira, P.I.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A. Telomeres and telomerase in Alzheimer’s disease: Epiphenomena or a new focus for therapeutic strategy? Alzheimers Dement 2006, 2, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zekry, D.; Herrmann, F.R.; Irminger-Finger, I.; Ortolan, L.; Genet, C.; Vitale, A.M.; Michel, J.P.; Gold, G.; Krause, K.H. Telomere length is not predictive of dementia or MCI conversion in the oldest old. Neurobiol Aging 2010, 31, 719–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zekry, D.; Herrmann, F.R.; Irminger-Finger, I.; Graf, C.; Genet, C.; Vitale, A.M.; Michel, J.P.; Gold, G.; Krause, K.H. Telomere length and ApoE polymorphism in mild cognitive impairment, degenerative and vascular dementia. J Neurol Sci 2010, 299, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, Y.; Kikukawa, M.; Hanyu, H.; Koyama, S.; Shimizu, S.; Umahara, T.; Sakurai, H.; Iwamoto, T.; Ohyashiki, K.; Ohyashiki, J.H. Association Between ApoE Phenotypes and Telomere Erosion in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2012, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movérare-Skrtic, S.; Johansson, P.; Mattsson, N.; Hansson, O.; Wallin, A.; Johansson, J.O.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Svensson, J. Leukocyte Telomere Length (LTL) is reduced in stable mild cognitive impairment but low LTL is not associated with conversion to Alzheimer’s Disease: A pilot study. Exp Gerontol 2012, 47, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fani, L.; Hilal, S.; Sedaghat, S.; Broer, L.; Licher, S.; Arp, P.P.; van Meurs, J.B. J.; Ikram, M.K.; Ikram, M.A. Telomere Length and the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease: The Rotterdam Study. J Alzheimers Dis 2020, 73, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, R.O.; Boardman, L.A.; Cha, R.H.; Pankratz, V.S.; Johnson, R.A.; Druliner, B.R.; Christianson, T.J. H.; Roberts, L.R.; Petersen, R.C. Short and long telomeres increase risk of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Mech Ageing Dev 2014, 141–142, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocco, P.; Barale, R.; Rose, G.; Rizzato, C.; Santoro, A.; de Rango, F.; Carrai, M.; Fogar, P.; Monti, D.; Biondi, F.; Bucci, L.; Ostan, R.; Tallaro, F.; Montesanto, A.; Zambon, C.-F.; Franceschi, C.; Canzian, F.; Passarino, G.; Campa, D. Population-specific association of genes for telomere-.

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. Mini-mental state. J Psychiatric Res 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magni, E.; Binetti, G.; Bianchetti, A.; Rozzini, R.; Trabucchi, M. Mini-Mental State Examination: a normative study in Italian elderly population. Eur J Neurol 1996, 3, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKhann, G.M.; Knopman, D.S.; Chertkow, H.; Hyman, B.T.; Jack, C.R.; Kawas, C.H.; Klunk, W.E.; Koroshetz, W.J.; Manly, J.J.; Mayeux, R.; Mohs, R.C.; Morris, J.C.; Rossor, M.N.; Scheltens, P.; Carrillo, M.C.; Thies, B.; Weintraub, S.; Phelps, C.H. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011, 7, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeith, I.G.; Galasko, D.; Kosaka, K.; Perry, E.K.; Dickson, D.W.; Hansen, L.A.; Salmon, D.P.; Lowe, J.; Mirra, S.S.; Byrne, E.J.; Lennox, G.; Quinn, N.P.; Edwardson, J.A.; Ince, P.G.; Bergeron, C.; Burns, A.; Miller, B.L.; Lovestone, S.; Collerton, D.; Jansen, E.N.; Ballard, C.; de Vos, R.A.; Wilcock, G.K.; Jellinger, K.A.; Perry, R.H. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology 1996, 47, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englund, B.; Brun, A.; Gustafson, L.; Passant, U.; Mann, D.; Neary, D.; Snowden, J.S. Clinical and neuropathological criteria for frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994, 57, 416–418. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, G.C.; Tatemichi, T.K.; Erkinjuntti, T.; Cummings, J.L.; Masdeu, J.C.; Garcia, J.H.; Amaducci, L.; Orgogozo, J.M.; Brun, A.; Hofman, A.; Moody, D.M.; O’Brien, M.D.; Yamaguchi, T.; Grafman, J.; Drayer, B.P.; Bennett, D.A.; Fisher, M.; Ogata, J.; Kokmen, E.; Bermejo, F.; Wolf, P.A.; Gorelick, P.B.; Bick, K.L.; Pajeau, A.K.; Bell, M.A.; DeCarli, C.; Culebras, A.; Korczyn, A.D.; Bogousslavsky, J.; Hartman, A.; Scheinberg, P. Vascular dementia: Diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN InternationalWorkshop. Neurology 1993, 43, 250–260. [Google Scholar]

- Cawthon, R.M. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 2002, 30, 47e–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, R.; Olivieri, F.; Sirolla, C.; Spazzafumo, L.; Rippo, M.R.; Marra, M.; Bonfigli, A.R.; Ceriello, A.; Antonicelli, R.; Franceschi, C.; Castellucci, C.; Testa, I.; Procopio, A.D. Leukocyte telomere length is associated with complications of Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 2011, 28, 1388–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrieri, G.; Bonafè, M.; de Luca, M.; Rose, G.; Varcasia, O.; Bruni, A.; Maletta, R.; Nacmias, B.; Sorbi, S.; Corsonello, F.; Feraco, E.; Andreev, K.F.; Yashin, A.I.; Franceschi, C.; de Benedictis, G. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroups and APOE4 allele are non-independent variables in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Genet 2001, 108, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, A.; Li, M.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. New Insights in Amyloid Beta Interactions with Human Telomerase. J Am Chem Soc 2015, 137, 1213–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilsbury, A.; Miwa, S.; Attems, J.; Saretzki, G. The Role of Telomerase Protein TERT in Alzheimer’s Disease and in Tau-Related Pathology In Vitro. J Neurosci 2015, 35, 1659–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhillon, V.S.; Deo, P.; Chua, A. , Thomas, P.; Fenech, M. Shorter Telomere Length in Carriers of APOE-ε4 and High Plasma Concentration of Glucose, Glyoxal and Other Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2020, 75, 1894–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackenhaar, F.S.; Josefsson, M.; Adolfsson, A.N.; Landfors, M.; Kauppi, K.; Hultdin, M.; Adolfsson, R.; Degerman, S.; Pudas, S. Short leukocyte telomeres predict 25-year Alzheimer’s disease incidence in non-APOE ε4-carriers. Alzheimers Res Ther 2021, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes, A.M.; Deary, I.J.; Gardner, J.; Kimura, M.; Lu, X.; Spector, T.D.; Aviv, A.; Cherkas, L.F. Leukocyte telomere length is associated with cognitive performance in healthy women. Neurobiol Aging 2010, 31, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochstrasser, T.; Marksteiner, J.; Humpel, C. Telomere length is age-dependent and reduced in monocytes of Alzheimer patients. Exp Gerontol 2012, 47, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Huo, Y.R.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, S.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Ji, Y. Telomere Shortening in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2016, 46, 260–265. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, E.R.; Dumitrescu, L.; Seto, M.; Nudelman, K.N. H.; Buckley, R.F.; Gifford, K.A.; Saykin, A.J.; Jefferson, A.J.; Hohman, T.J. Telomere length associations with cognition depend on Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Alzheimers Dement 2019, 5, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, S.-H.; Choi, S.H.; Jeong, J.H.; Jang, J.W.; Park, K.W.; Kim, E.J.; Kim, H.J.; Hong, J.Y.; Yoon, S.J.; Yoon, B.; Kang, J.H.; Lee, J.M.; Park, H.H.; Ha, J.; Suh, Y.J.; Kang, S. Telomere shortening reflecting physical aging is associated with cognitive decline and dementia conversion in mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease. Aging 2020, 12, 4407–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukens, J.N.; van Deerlin, V.; Clark, C.M.; Xie, S.X.; Johnson, F.B. Comparisons of telomere lengths in peripheral blood and cerebellum in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimes Dement 2009, 5, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).