1. Introduction

No wadays antivirus software is one of the primary tools that the computer world uses to defend their computer and network systems. Actual combat results between antivirus and various malware show that antivirus software protects computer systems from malware attacks. When an antivirus engine detects a malicious program, it terminates and informs the system of the attacks. As the wars between antivirus and malware continue, both sides find a way to defeat each other. One of the effective strategies malware makers adopt is to find a way to bypass antivirus detection. In other words, they try to make their malware stealth to antivirus. In other words, they try to make their malware stealth to antivirus. Due to the limited resources that an IoT has, allow lists, instead of antivirus engines, are commonly used by IoT devices to prevent the execution of malware. Linux is widely used by IoT devices. But fileless malware can be injected into a process in an allow list first and then be executed without be detected in a Linux system. Hence, fileless malware is very dangerous for IoTs and facilities using Linux. Therefore, it is a critical issue to develop a solution to protect a Linux system against fileless malware.

One of the stealth techniques that malware makers have utilized most frequently recently is fileless malware. Even though fileless malware is not a novel attack vector, there has been an increasing trend in using this technique in the recent year [

5] due to its high success rate. According to a 2017 report, 77% of the successful attack cases[

2] used fileless virus attack techniques. The report shows that traditional antivirus software cannot provide comprehensive protection to computer systems. Besides, an account [

3] published in 2020 shows that fileless malware rates in 2020 increased by 888% over 2019. Plenty of Ransomware and crypto-miners use fileless malware to spread malware to hosts nowadays.

Fileless malware resides in the address space of a legal process. However, traditional signature-based antivirus detects malware based on the malicious code stored in a file. Because signature-based antivirus cannot obtain the malicious code stored in physical memory, signature-based antivirus cannot detect related attacks. Initially, the most common targets of fileless malware are Windows hosts. Along with the popularity of Linux-based servers (such as web servers), desktops, IoT devices, and so on, lately, fileless malware on Linux platforms also emerges [

4], and the number of Linux fileless malware continues to increase. The methods utilized for generating fileless malware on Windows systems differ from those [

5] used for creating fileless malware on Linux systems. The reason for this is that the mechanisms and interfaces for inserting code into the memory of a process from a different approach are different on Windows and Linux platforms. For example, macros of Windows Office, PDF, PowerShell, and system management tools, such as Windows Management Interface Command (WMIC) and CertUtil, are frequently used in Windows fileless malware. However, Linux fileless malware has seldom utilized them [

6]. However, the targets of both Windows-based fileless malware and Linux-based fileless malware are the same. They all want to store malicious code in the address space of a legal process executing at the target host.

In this paper, we provide a fileless malware detection Checkon- Execute (CoE) is the mechanism for Linux to prevent the execution of fileless malware on a Linux platform. Patent applications [

7], [

8] for CoE are under review. CoE suspends the execution of code stored in a writable memory area. Then CoE checks and analyzes related code to see whether the code is malicious or not through VirusTotal. If the intercepted code is malicious, CoE terminates the related process immediately. Hence, CoE protects a system from attacks. Experimental results show that CoE can significantly enhance the ability of a system to defense against fileless malware even using the signature databases of various antivirus engines, which alone are not able to defend a system against fileless malware currently. Experimental results show that CoE is a potential defense tool to protect a system from shell code injection attacks, such as buffer and heap overflow attacks. It can handle malware that has been compressed using different packing utilities.

The first section of this paper is an introduction that describes the basic concepts and inspirations of this paper. The second section is the background which introduces the background knowledge. The third section is related research that focuses on the defense mechanisms provided by the current antivirus software. Section IV presents the system structure and implementation details of CoE, while Section V reports the evaluation results of CoE. The limitations of CoE are discussed in Section VI, and the final section summarizes the paper, highlighting the contributions of CoE and outlining directions for future work.

2. Background

This section introduces the relevant background knowledge of Linux fileless malware. Even though the way to inject malicious code into a process in a Windows system differs from the track used in a Linux system, their purposes are the same. These methods want to insert malicious code into the address space of a process. In other words, these methods want to put the code in physical memory, not a file in permanent storage.

2.1. Fileless Malware

Fileless malware is an attack vector and also an attack technique. Unlike traditional malware, whose code is stored in a file at the permanent storage of a victim host, the code of fileless malware is stored at the address space of a process running in a victim host. Antivirus software must obtain the file to analyze whether a file is malware. Because the code of fileless malware is stored in the physical memory of a victim host and current antivirus software has not been designed to retrieve code from memory whose content may change, it is challenging to detect fileless malware. As a result, more and more malware makers use fileless malware to dispatch their malicious code.

2.2. Approaches to inject code into a process

There are two main approaches to injecting code into the address space of a Linux process. The first one utilizes the buffer overflow vulnerability [

9] of a strategy to inject shell code into the address space of the vulnerable process. This injection can be completed through a cycle inside/outside the target process. Stack-smashing attacks [

10]and heap overflow attacks [

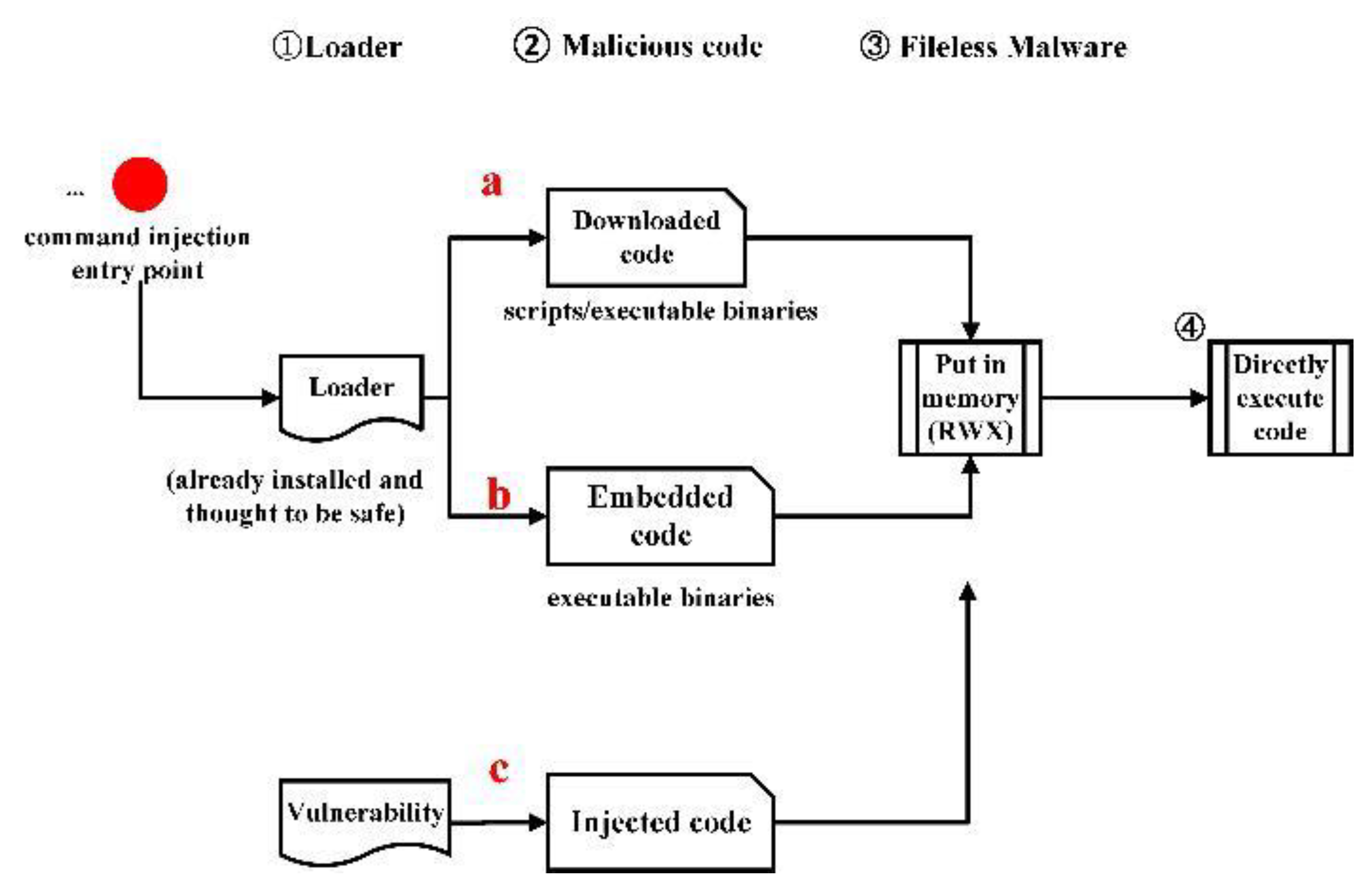

11] are launched this way. Path c in

Figure 1 shows this route.

The second approach [

12] needs the cooperation of a process inside the target host to perform code injection. This process is executed through command injection attacks [

13] launched outside the target host. This process, usually a Linux shell, may become the loader of

Figure 1. Or this process may invoke the execution of other loaders. Other loaders include Python, Perl interpreters, and so on, which Linux distributions usually have pre-installed in a Linux system. In addition, PHP on hosting platforms is also frequently used as a loader.

In summary, a loader could be either a Linux shell process or a process executed by a Linux shell. A loader is responsible for downloading malicious code to a target host from an external host. When a loader is a Linux shell, malicious scripts or executable binaries are downloaded, injecting malicious code into a process, and executing the malicious code occurs in memory. No file is touched. For example, the following

shell commands

$ curl http://attacker/evil.pl | perl downloads a malicious Perl script from a remote host and invokes a Perl interpreter to execute it. All the above operations happen in memory only. In this case, the shell is the loader.

Malicious code could be either a script or an executable binary, as shown in path a of

Figure 1. When an executable binary belonging to this type is executed, the related process can inject malicious code into a different process using a system called

ptrace(). The process can also use a system called

memfd_create() to allocate a memory area in the address space itself. Then the process injects a malicious ELF file into the allocated memory area. Finally, the process executes the malicious ELF directly without touching any other file in the permanent storage of the target host. If the downloaded code is malicious, the script could use a system called

memfd_create() to do the same thing described above. The malicious code shown in path b of

Figure 1 is also an executable binary. But its data area contains malicious machine code already. By transferring execution flow to the malicious machine code in the data area, a process belonging to this type can execute the malicious machine code directly. After any of the above process types is created and malicious code is executed, all related files are deleted from their storage. Using the

ptrace() system, an injecting process can inject code into a different process (injected process). However, to do so, the injecting process must first collect the PID and memory layout of the injected process on the target host. As a result, it is often more practical, easier, and less detectable to create fileless malware at the target host using the

memfd_create() system call.

2.3. An Execution Example of Fileless Malware

In this subsection, we give an example to show how fileless malware is spread into a host and executed.

Figure 2 shows this example. The target host in this figure has a command injection vulnerability; hence, an attacker can use command injection to execute a shell in the target host. Suppose the target host contains Perl or Python interpreters, commonly pre-installed software in various distributions nowadays. In that case, an attacker can use the shell to execute the following commands

$ curl http://attacker/evil.pl | perl or the following commands

$ curl http://attacker/evil.py | python. Either command downloads a script to the target host from a remote host, and then invokes an interpreter to execute the script. The above operations do not create a file in the permanent storage of the target host.

In the Perl script case, the Perl interpreter creates a process to execute the downloaded Perl script, evil_elf.pl first executes the system call memfd_create() to configure an anonymous file in the process’s address space, then writes a malicious ELF binary into this anonymous file, and finally executes the malicious binary. The malicious ELF still resides in the memory of the process, not in a file at the permanent storage of the target host. As a result, the download operation, injection operation, and execution operation occur in the target host’s memory. Because the system called memfd_create() first appeared in Linux version 3.17 in October 2014, this example can work only on a Linux distribution with a Kernel version that is 3.17 or newer than 3.17.

The function of memfd_create() is similar to malloc(). The difference is that malloc() returns an indicator that points to an allocated memory. memfd_create() creates an anonymous file in the memory and returns its file descriptor. memfd_create() was initially designed to allow various programs to share a memory and exchange messages through file descriptors. This kind of file is similar to a regular file function, with the write and read functions, and can also be loaded into memory for execution. However, only the link file can be seen in the file system. This anonymous file does not exist on a physical hard disk. A link file is a particular file that points to another file.

3. Related Work

This section introduces the current defense methods and characteristics of antivirus software, analyzes the defense effect against fileless attacks, and points out their shortcomings. Currently, in the industry, antivirus software that can detect fileless malware usually are designed for Windows. Finding such antivirus software in a Linux system is rare, if not impossible.

3.1. Fileless Malware Collections, Creation, and Analyses

Antivirus software that detects fileless malware is usually developed for Windows in the industry. Finding such antivirus software in a Linux system is rare, if not impossible. Hence, the major effort for Linux fileless malware is to analyze the behaviors of Linux fileless malware. Fan Dang et al. [

14] deploy hardware and software IoT honeypots to collect fileless attacks on Linux-based IoT devices in the wild. They also analyze the collected samples to get their prevalence, exploits, environments, and impacts. B.N. Sanjay et al. [

15] conducted a details survey on fileless malware, especially Windows fileless malware. Sherif Saad et al. [

16] designed and implemented a fileless malware by using new features in JavaScript and HTML5. They tested their proposed fileless malware with several free and commercial malware detection tools that apply static and dynamic analysis. Experimental results show that their fileless malware bypassed all the anti-malware detection tools used in their study. In a 2021 malware survey about diverse notorious malware made by [

17], Caviglione et al. concluded, “... standard mechanisms such as system monitoring, firewalling, and proxying, restricted access to command prompts, website analysis, whitelisting, and user education could be ineffective. Thus, research is needed to detect and counteract fileless threats efficiently.”

3.2. Static Analysis

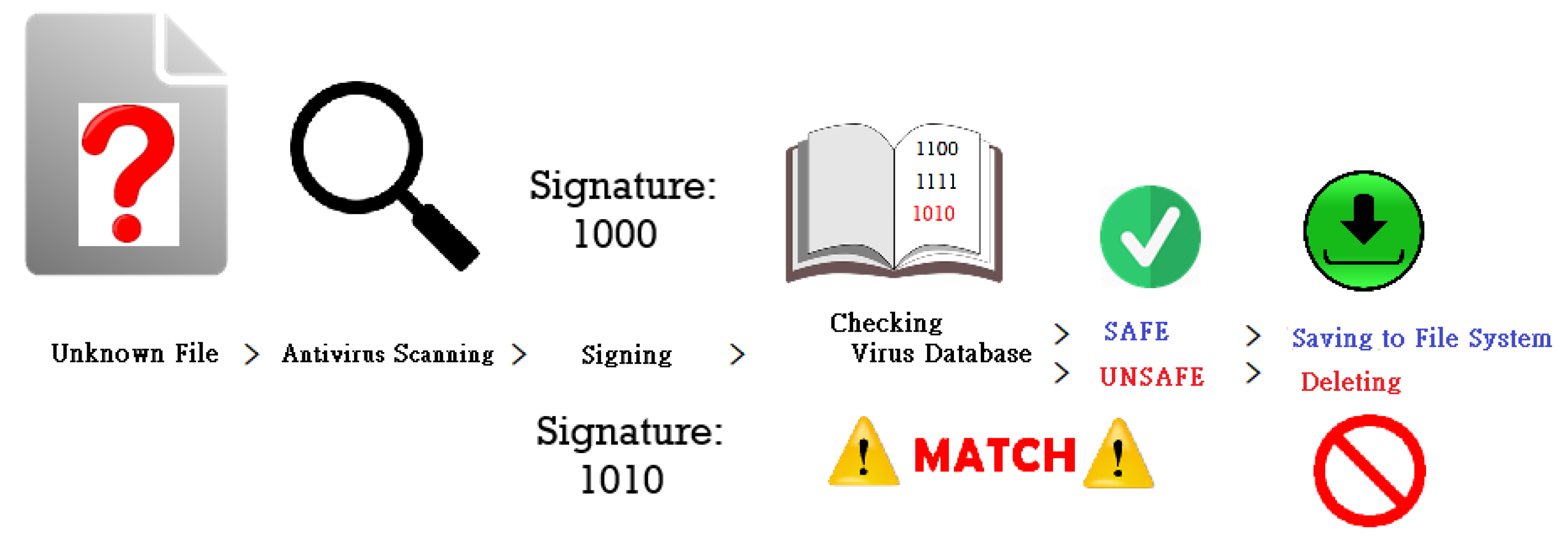

One of the static analysis techniques antivirus software uses is signature-based technology, which most antivirus software adopts. As shown in

Figure 3, this type of antivirus software scans a file to generate its signature. Then it looks up the virus signature database to see whether the file's signature matches the virus's signature in its virus signature database. The file is deemed a virus file if there is a match. Otherwise, it is deemed as a normal file. Antivirus software destroys the virus file and issue a warning message to the computer users. Each antivirus software company maintains its virus signature database. The quality of the virus signature database determines the detection precision of an antivirus. Because virus signature databases are the signatures of zero-day viruses, static analysis-based antivirus cannot detect zero-day viruses. Because new viruses continue emerging, antivirus software companies must collect new virus signatures persistently and update their virus signature database continuously to mitigate the influence time of zero-day viruses.

This time-consuming job requires experienced professionals to maintain the virus signature database. Besides, to avoid being detected by antivirus software, virus makers develop various approaches to change the forms of their viruses. Encryption and compression are the most used transformation methods [

18]. An antivirus must obtain the file before applying static analysis to check whether a file is a virus file. However, the fileless malware’s code resides in a host’s memory, not the host’s file. Thus, it is challenging for static analysis-based antivirus software to detect fileless malware. After all, current static analysis-based antivirus software cannot retrieve malicious code stored in memory.

3.3. Dynamic Analysis

Dynamic analysis is the other virus detection method. Researchers have found that most viruses have some special behavior patterns. These behavior patterns are relatively rare in normal programs. Hence, dynamic analysis-based antivirus software uses these special behavior patterns to determine whether a running process is a virus. For example, normal programs call graphics APIs to draw interfaces first, but viruses usually start reading and writing a hard drive directly and download other malicious programs. Dynamic analysis-based antivirus can detect the existence of fileless malware. Dynamic analysis-based antivirus software usually creates an isolated virtual environment first and then executes the program it wants to check in this virtual environment.

Meanwhile, when the program is executed in an isolated environment, dynamic analysis-based antivirus collects behaviors generated by the program. Finally, based on the behaviors that the antivirus software contains, the antivirus software determines whether the program is a virus. For example, McAfee utilizes behavior and dynamic analysis to detect whether a program runs simultaneously with PowerShell.

Compared with static analysis-based virus detection approaches, dynamic analysis-based virus detection approaches usually use more resources and may create more false alarms. Besides, it is not tricky for malware makers to change the behaviors of their malware while completing the same work. And malware makers may add some operations to bypass detection. For instance, a virus can elude detection by introducing a delay of 100 to 200 milliseconds to a harmful command. Moreover, some malware will first detect whether they are in an isolated virtual environment, such as a virtual machine or sandbox. It does not execute malicious code if it finds it is in a remote virtual environment.

3.4. Security Settings to Block Fileless Malware Execution

Security settings can turn off some functions that may be abused by fileless malware to dispatch it to various hosts. Usually, they are radical solutions and may influence users’ usage experience of some programs. This defense method is not recommended if a user needs a more open environment. Two examples utilize security settings to protect a system against fileless malware. First, Microsoft Office users can turn off the macros to avoid fileless malware that is spread through macros. Second, Web browser users can turn off the JavaScript execution capability of their browsers to prevent related attacks. However, this may make most websites work abnormally.

Provide users with setting security policies of a Linux system, which can achieve fine-grained access restrictions and can be set to prohibit the execution of fileless malware. Besides, because fileless malware may utilize the directories used by shared memory, such as /tmp or /dev/shm/, some administrators may mark these directories as non-executable to protect their systems from fileless malware that uses these directories. But a super user can still execute the programs in these directories.

4. Goals, Principles, and System Structure

This section describes the goals, principles, system structure, and major components of CoE. Unlike the approaches adopted by system settings (subsection 3.4.) which may disable some system functions, CoE does not turn off any function provided by a system while protecting the system from fileless malware. Besides, the influence on the performance of normal processes created by CoE is trivial. Here, a normal process means a process that does not execute code stored in a writable memory area. For legal processes that need to execute code stored in a writable area, such as a heap, if a system maintains the hash value of the code confirmed to be benign, then only the performance of the first execution of the processes will increase.

4.1. Design Principles

CoE is designed based on the following principle. For security reasons, a writable page of a process is usually not executable. However, due to different special purposes, sometimes a writable area, such as a heap area, still must be writable and executable simultaneously. Meanwhile, writable process areas are often injected with fileless malware. Hence, we can identify and stop the execution of harmful code injected into a process if we can pause the execution stored in a writable region, collect the code, and determine if the managed code is a virus. In other words, we can protect a system from fileless malware. Meanwhile, legal processes can still use a writable memory to store their code and then execute the code if we let the suspended process continues running when analysis results show that the code is not a virus.

4.2. System Structure

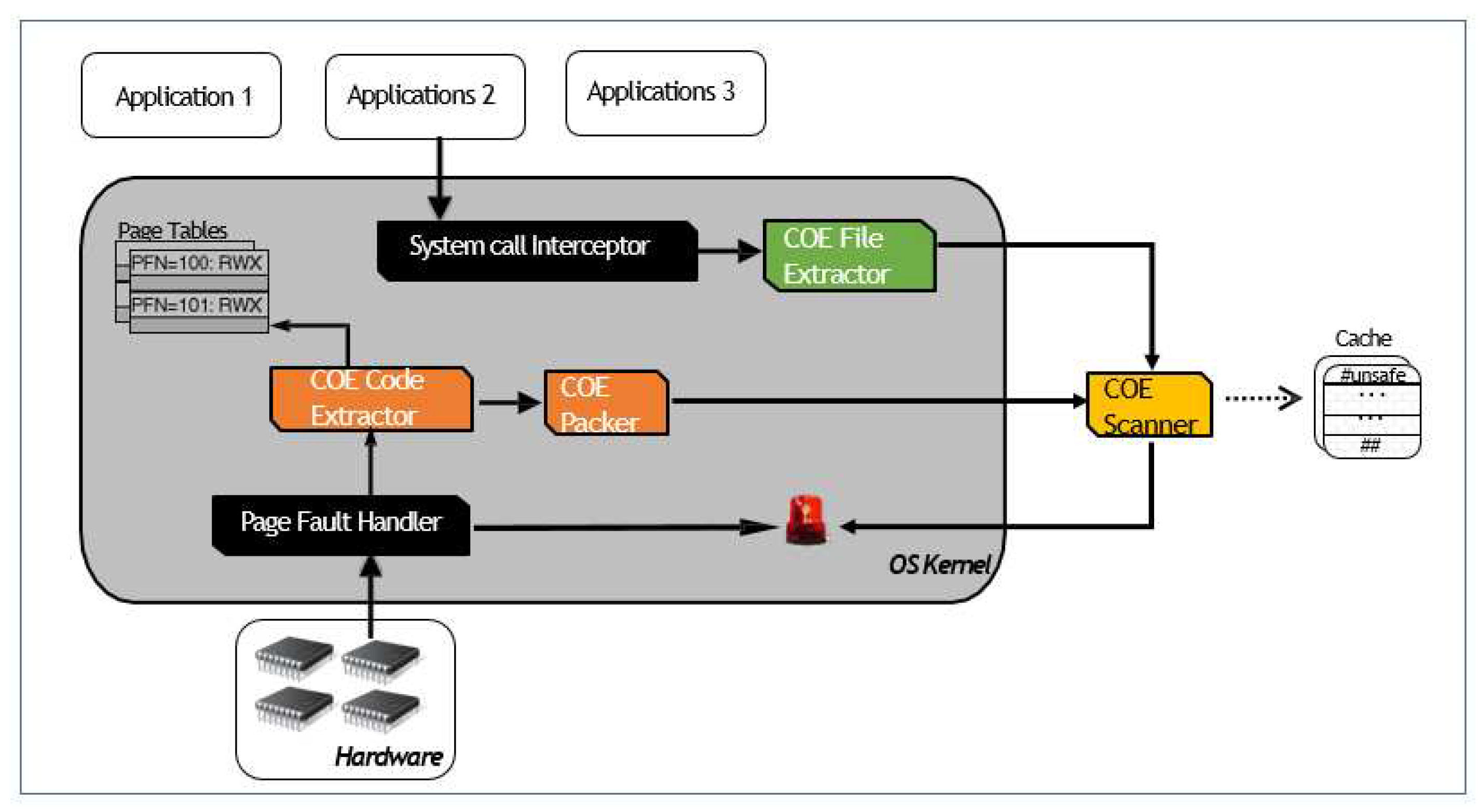

Figure 4 shows the system structure of CoE. CoE consists of the following major components:

CoE System Call Interceptor,

textitCoE Page Fault Handler,

CoE Scanner,

CoE File Extractor,

CoE Code Extractor, and

CoE Packer, except for component

CoE Scanner, which is in a user space process. The Linux kernel address space contains all the remaining components. The primary element within the

CoE System Call Interceptor is the

CoE File Extractor. Meanwhile, the

CoE Page Fault Handler is constructed upon the foundations of the Linux Page Fault Handler, but with the addition of two extra components: the

CoE Code Extractor and

CoE Packer. As mentioned in subsection 2.2, there are different approaches for fileless malware to inject code into the address space of a process. We use component

CoE System Call Interceptor and component

CoE Page Fault Handler to intercept and catch the code stored or stored in a process’s memory.

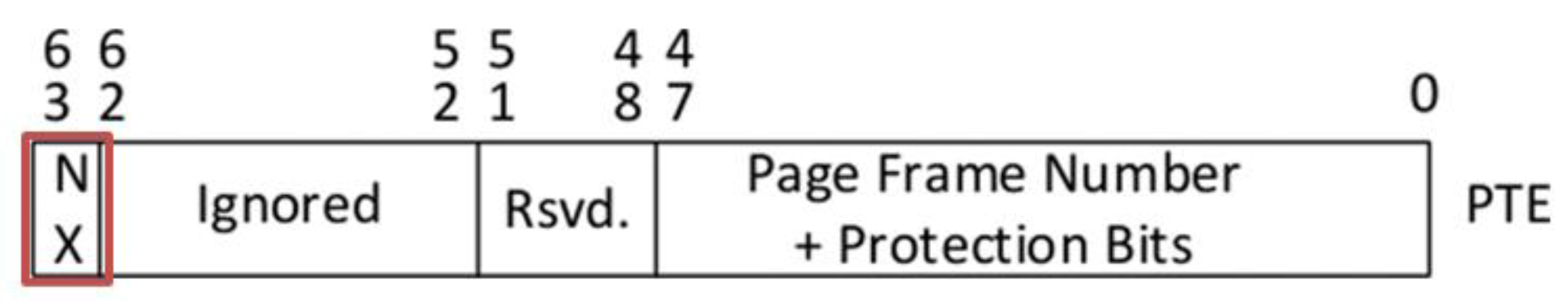

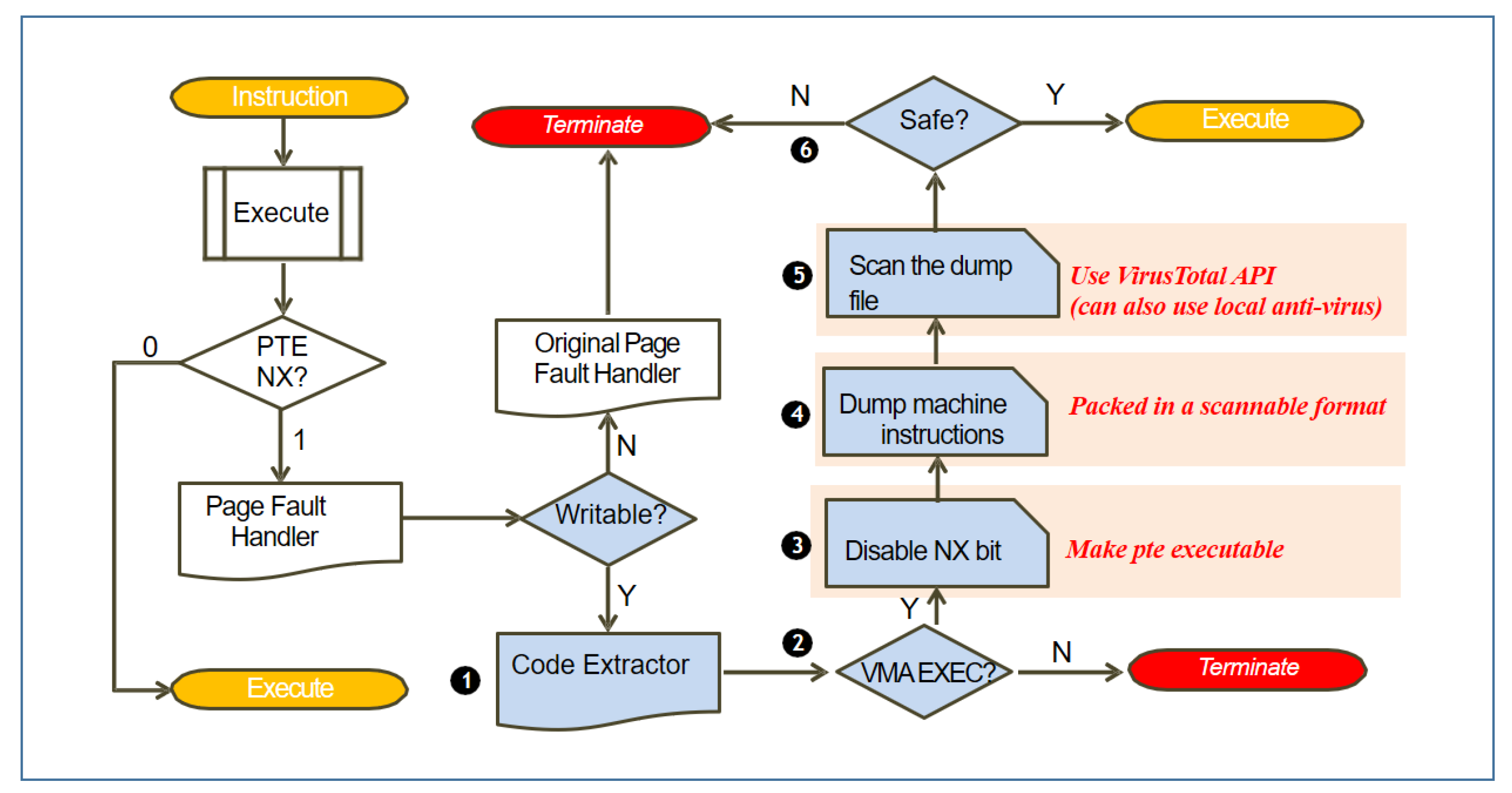

CoE Code Extractor: CoE Code Extractor: The main function of the CoE Code Extractor is to extract code from memory. CoE Code Extractor uses the

NX bit (No eXecute bit) provided by AMD 64-bit CPU or the

ND bit (execute disable) provided by Intel 64-bit CPU and supported by Linux to trigger its execution.

Figure 5 shows the layout of a Page Table Entry (PTE) and the position of the

NX bit in a

PTE. When the

NX bit of a PTE of a page frame is set to 1, it means the page frame is not executable. In other words, if a CPU retrieves the content of the page frame as code and tries to execute it, a Page Fault Exception [

19] will be triggered. CoE Code Extractor inside CoE Page Fault Handler will be executed. CoE sets the

NX bits of all

PTEs whose corresponding page frames are writable and executable to 1 in advance. CoE utilizes hardware to assist it in checking whether a CPU is trying to execute code stored in a writable page frame. As a result, CoE does not need to spend time in software to make the above check.

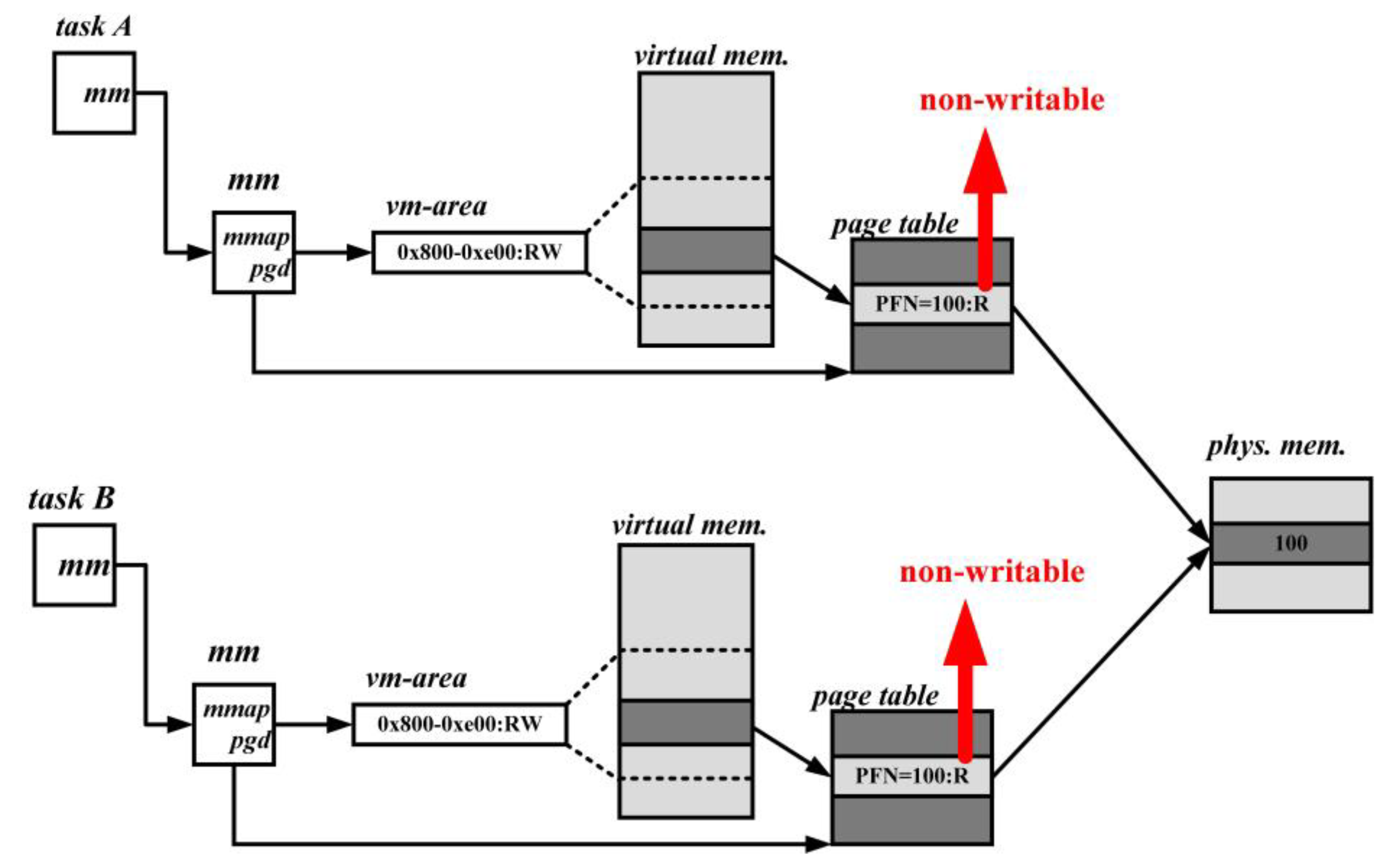

Copy-on-write [

20] mechanism adopted by most modern OSes, including Linux, inspires our design of the execution triggering mechanism of the CoE Code Extractor.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 explain how copy-on-write works. As shown in

Figure 6, there are two tasks (i.e., processes),

task A and

task B, sharing a physical page frame. The

PTE in t

ask A for the page frame, called

PTEA, will be marked as non-writable. Similarly, The

PTE in

task B for the same page frame will be marked as non-writable too. When

task A wants to write some data into this page frame, a Page Fault Exception will occur because the permission setting on the

PTE is non-writable. Suppose the Page Fault Handler discovers that the virtual memory area assigned to task A designates the page frame as writable. In that case, it recognizes that the copy-on-write mechanism triggers the fault. Consequently, the handler gives a new page frame to

task A, updates

PTEA to point to this new page frame, and sets the new page frame as writable in

PTEA.

Figure 7 shows the result.

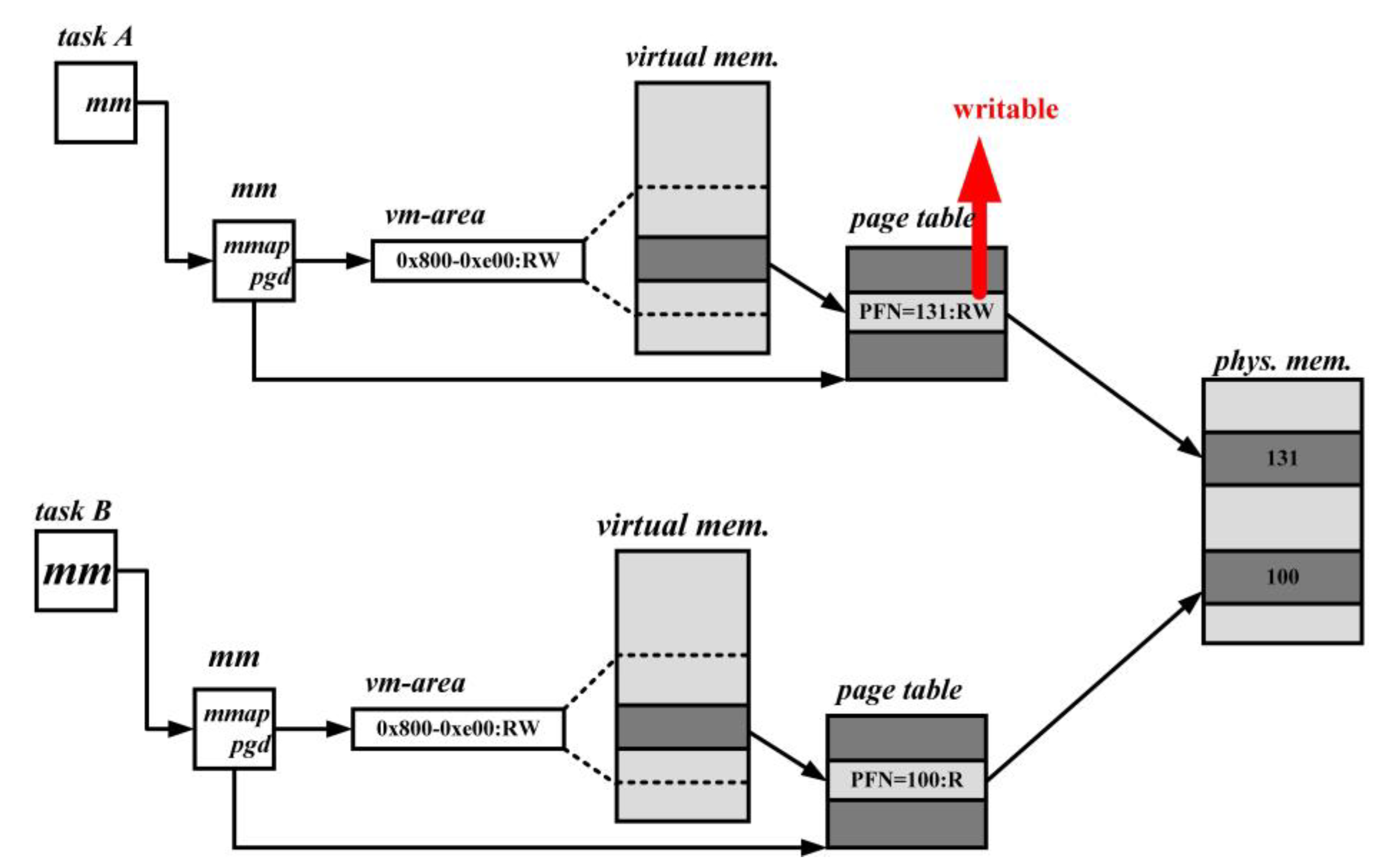

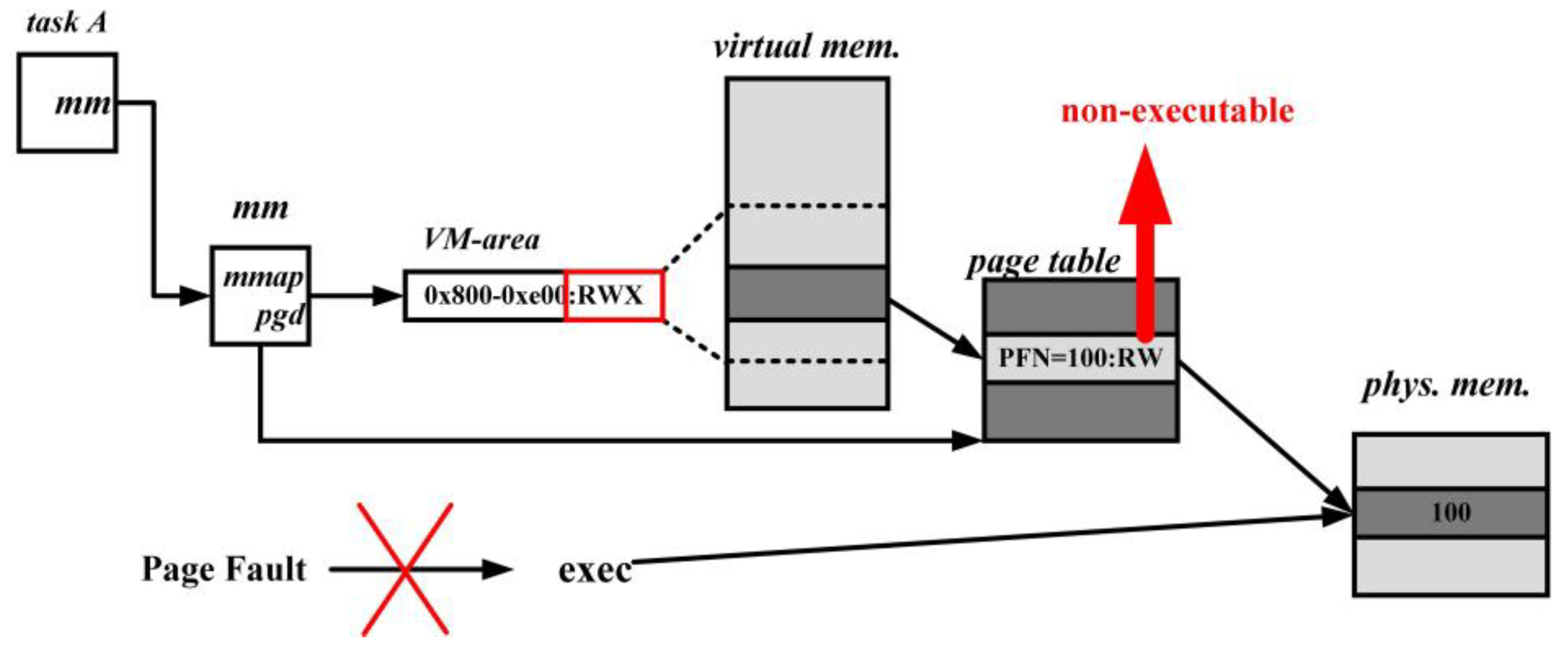

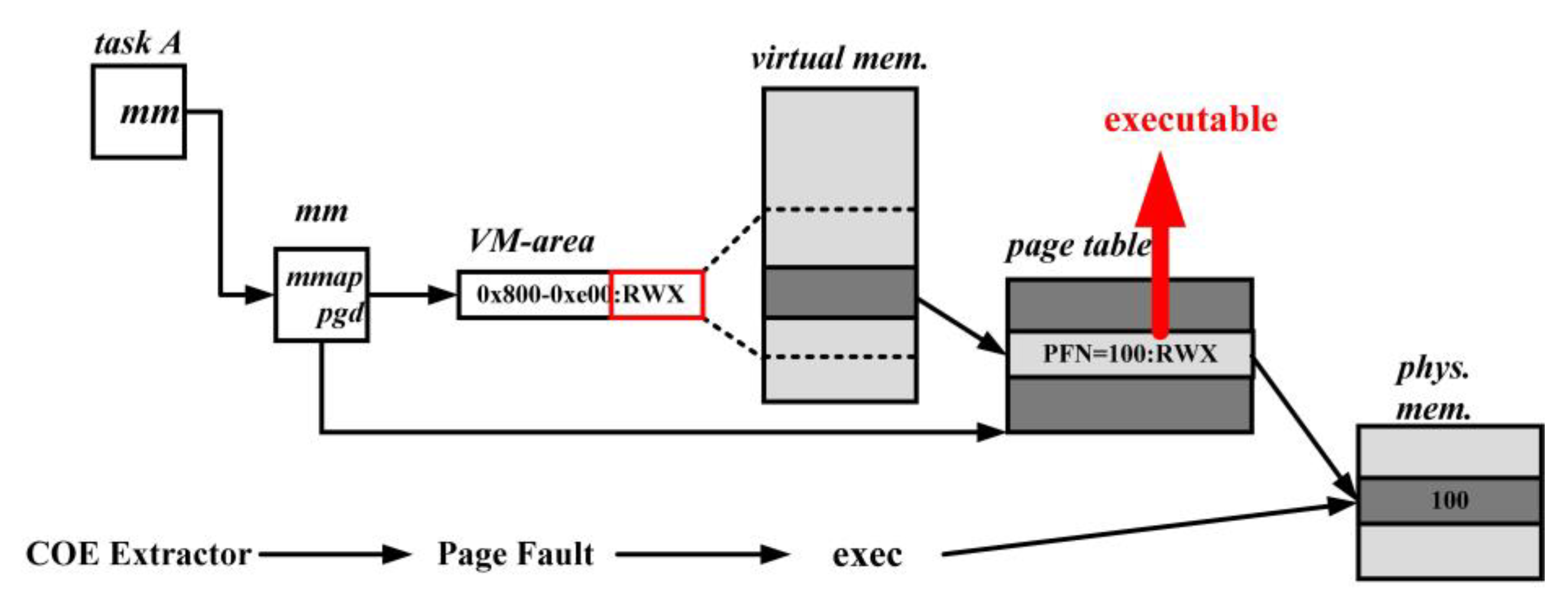

CoE uses

NX bit and a mechanism similar to

copy-onwrite to trigger the execution of the CoE Code Extractor. The page frame with the number 100 in the rightmost square of

Figure 8 represents a page frame that is readable, writable, and executable.

task A’s corresponding vm-area will retain a record of these permissions. Because it is writable and executable, CoE will first set the

PTE for this page frame as non-executable. As a result, when

task A tries to executable code stored in this page frame, a page fault is issued, CoE Code Extractor is executed, and CoE checks the executable permission of the page frame in the related vm-area. If the page frame is not executable, CoE Code Extractor terminates the execution of

task A. If the page frame is executable, CoE collects the code in the page frame and sends the code to other CoE components for analysis. If the code is malicious, CoE terminates

task A; otherwise, CoE sets the page frame as executable in its PTE and lets

task A resume its execution (as shown in

Figure 9).

- 2.

CoE Packer: The main function of the CoE Packer is to pack the code extracted from the memory into ELF format. Once the CoE Code Extractor recognizes the necessity of verifying a code segment stored in a writable region, it directs the CoE Packer to retrieve the code and bundle it into an ELF file. The CoE Packer accomplishes this by appending the corresponding ELF header [

21] and setting the ELF header’s entry point field to the assembled code’s starting point. CoE transfers the code into an ELF file is that CoE uses VirueTotal [

22] to check whether a piece of code is malicious or benign. And VIrutTotal only accepts and analyzes data in a file form.

- 3.

CoE Scanner: The main function of the CoE Scanner is to scan a packed ELF file. After CoE Code Packer packs a piece of code into an ELF file, it hands it over to CoE Scanner to check whether the code is malware. The current version of CoE Scanner uses VirusTotal’s APIs to ask VirusTotal to help CoE Scanner check whether a piece of code is malware. VirusTotal [

22] provides a free/pay malware analysis service and has assembled over 60 antivirus engines to analyze input files.

- 4.

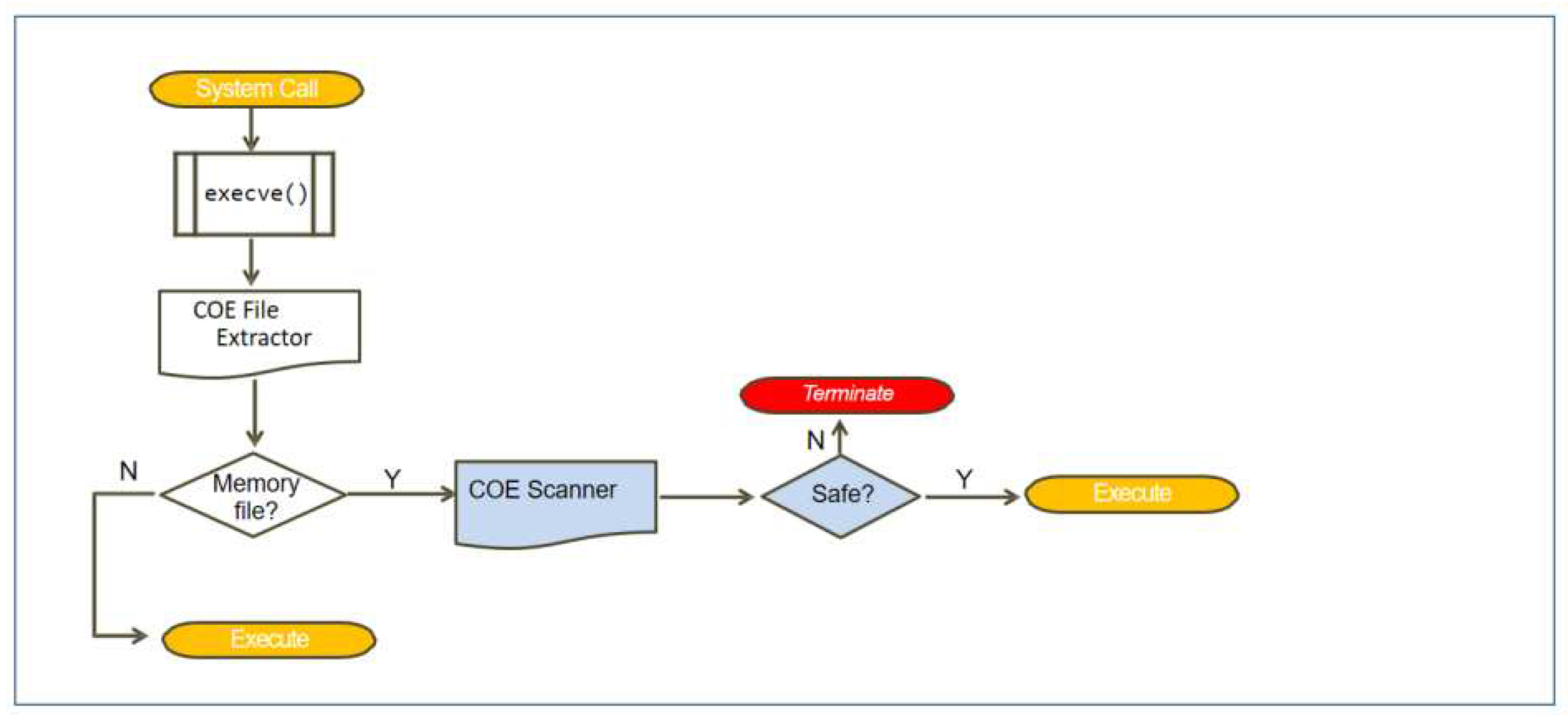

CoE File Checker: As described in subsection 2.2, files malware may use system call memfd_create() to create an anonymous area to inject a malware file and then use system call execve() to execute the file hidden inside the address space of a process. CoE File Checker intercepts and collects files executed this way. When a program uses system call execve(), CoE File Checker checks the location of the file that is going to be executed and determines whether the file is in memory. If it is in the memory, CoE File Checker pauses the execution first, retrieves the file, and then submits it to CoE Scanner for further analysis. CoE File Checker only allows benign programs to continue their execution.

4.3. Execution Paths of CoE

There are two execution paths, called file path and text path, that CoE uses to handle fileless malware. ComponentsCoE File Checker and CoE Scanner consist of the file path to handle fileless malware created by the operating system calls memfd_create() and execve(). As described in subsection II-B, fileless malware created this way is more common, more accessible, and more stealthier to use. After all, compared with fileless malware created operating system call ptrace(), this kind of fileless malware does not need to collect information of an injected process, such as PID and memory layout of collect injected process, from an injecting process at a target host. Components CoE Code Extractor, CoE Packer, and CoE Scanner comprise the text path to handle fileless malware, which only has machine code residing in an attack process. The machine code may be stored in a writable and executable memory area of the process or injected into the process using a system call sptrace().

Execution Flows of the File Path: When CoE learns that a process uses a system called

execve() to execute a program, CoE File Extractor first checks whether the file is in the memory, as shown in

Figure 10. CoE File Extractor allows the process to execute the file if the file is not stored in the memory. But if the file is stored in memory, CoE File Extractor retrieves the file and gives the file to CoE Scanner. Then CoE Scanner utilizes VirusTotal to check whether the file is malicious. The CoE File Extractor allows the system to handle a file normally unless it is determined to be malicious, in which case the execution of the file is prevented, and the process is terminated promptly.

Execution Flows of the Text Path: When the execution of an instruction, the CPU hardware checks the

NX bit in the

PTE of the corresponding page frame, as shown in

Figure 11. If the

NX bit is 0, the instruction is allowed to execute. However, if the

NX bit is 1, the hardware triggers a Page Fault Exception. The exception then verifies whether the permission in the vm-area of the page frame is writable. If it is writable, execution is transferred to CoE Code Extractor to determine whether the permission in the vm-area is marked as executable. The Page Fault Handler terminates the related process if the permission is marked as non-executable. CoE Code Extractor restores the NX bit to 0 if the permission is marked as executable. And then, CoE Packer retrieves the code from memory and packs the code with an ELF header to transform the code into an ELF file. Later on, the ELF file is sent to CoE Scanner. CoE Scanner scans the file using VirusTotal to determine whether the code is malicious or benign. If the file is harmless, CoE Scanner resumes the execution of the code; otherwise, it terminates the execution of the code. The size of a page frame is 4K.

5. Evaluation and Analysis

This section describes the results of various experiments which were made to evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of CoE and analyzes the experimental results to check whether CoE can protect a Linux system from the attacks of various fileless malware.

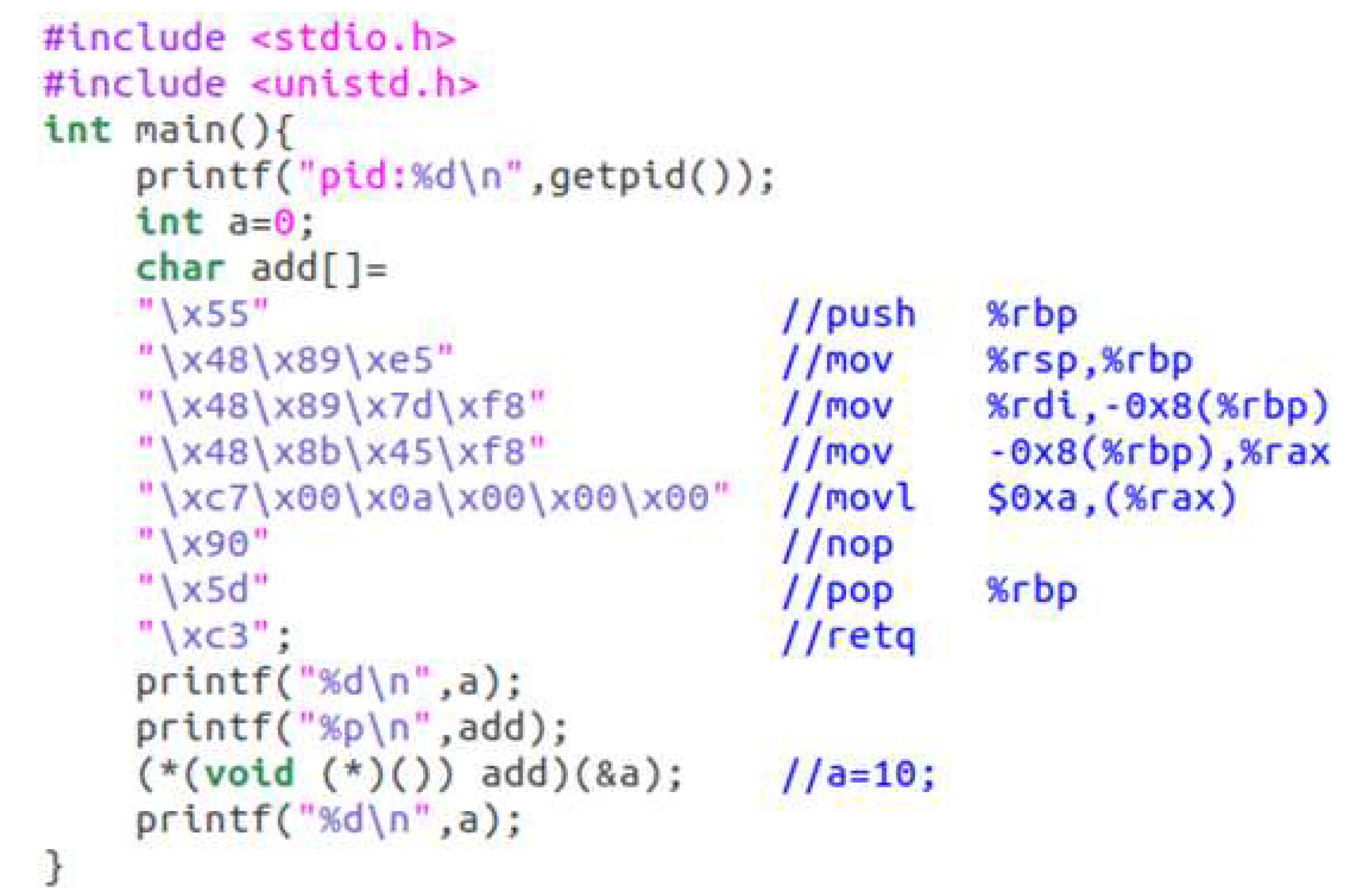

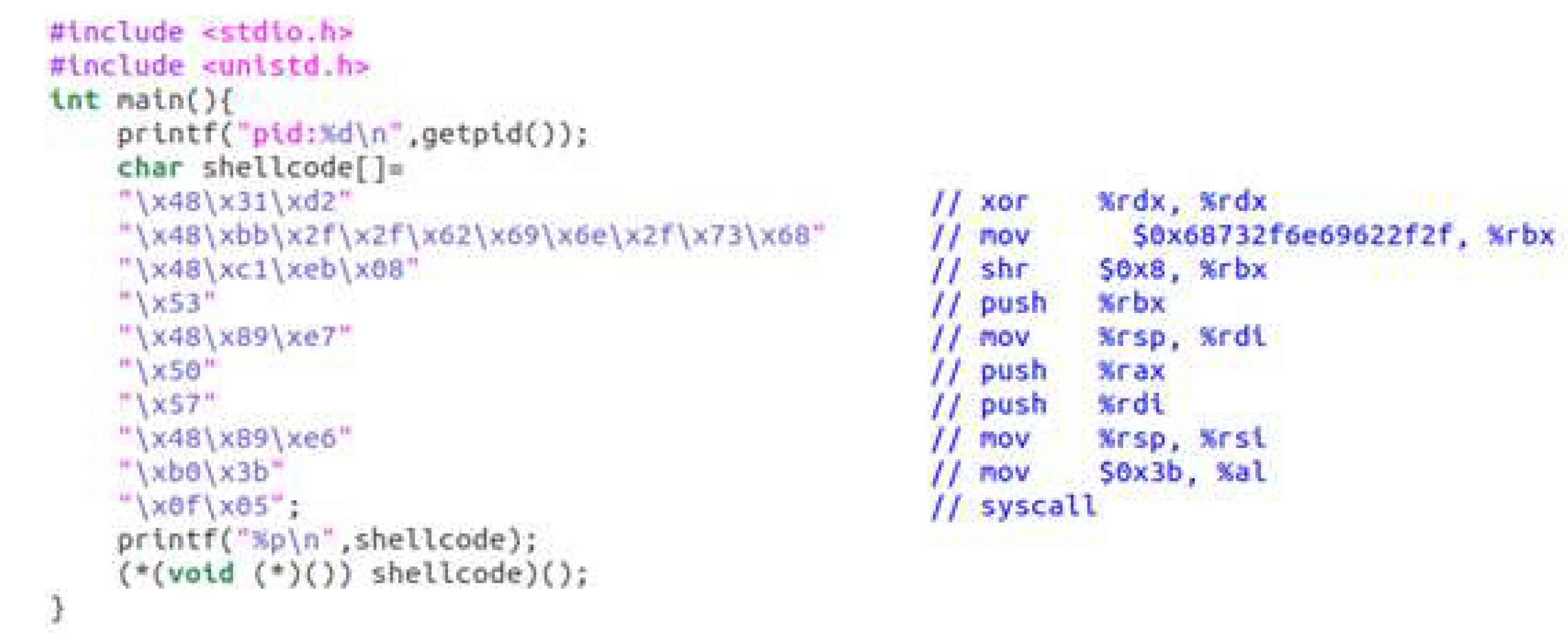

5.1. Effectiveness Tests for Code Stored in the Stack Segment

The host, OS, and Linux kernel we used to do our experiments in this subsection have the specifications in

Table 1. To determine if CoE can pause the running of code saved in a writable memory area, we created two programs,

unsafe_code.c (displayed in

Figure 12) and

unsafe_code.c (displayed in

Figure 13). These programs contain machine code stored in a local array variable, and the execution is then transferred to the stored machine code. To test this ability, we retrieved the code, packed it into an

ELF file, and sent it to VirusTotal. In

safe_code.c, the machine code in this file changes the value of a local variable a to 10. In

unsafe_code.c, the machine code in this file is a piece of shell code. Shell code is often used in buffer overflow attacks. When executing the above programs, we allow a test process stack to be executable.

safe_code.c to be executed successfully and disables the execution of program safe_code.c. Besides, program safe_code.c has the same pattern as a traditional buffer overflow attack. The experimental results show that CoE not only can protect a system from fileless malware but also can protect a system from buffer overflow attacks and heap overflow attacks. But this paper only focuses on fileless malware.

In addition to the previous experiments, we conducted further tests to assess the current efficacy of antivirus engines against fileless malware. Clam AntiVirus (ClamAV) [

23] is a popular open-source Linux antivirus engine. We randomly picked up some viruses that ClamAV can detect to make further tests first. Then we transferred the viruses into fileless malware form and provided the newly created fileless malware to ClamAV to examine. But ClamAV cannot find that the fileless malware contains viruses. The results show that it is still difficult for an antivirus engine to detect fileless malware. The results match Caviglione et al.’s conclusions about fileless malware, see subsection 3.1.

5.2. Effectiveness Evaluation

To evaluate the effectiveness of CoE, we use three different kinds of malware obtained from diverse sources to conduct our experiments. The three types of malware used in our experiments were sourced from other locations. The first type was obtained from VirusShare [

26], the second consisted of shell code collected from the Shell-storm Database [

24], and the third was packed malware. We use the following steps to create packed malware that we will use in our experiments. We chose some pieces of malware from the first kind of malware first. For each desired piece of malware, we retrieved its text segment only and added our ELF header and entry point to form a new file, and finally, we used a packing tool to pack the new file. When the execution of the three types of malware, whether directly or indirectly through a process, CoE was able to identify and halt their execution. CoE also generated or retrieved relevant ELF files for scanning. The detection effectiveness of CoE relied entirely on the virus signature databases we utilized. We rely on VirusTotal [

22] to determine if a file is malicious.

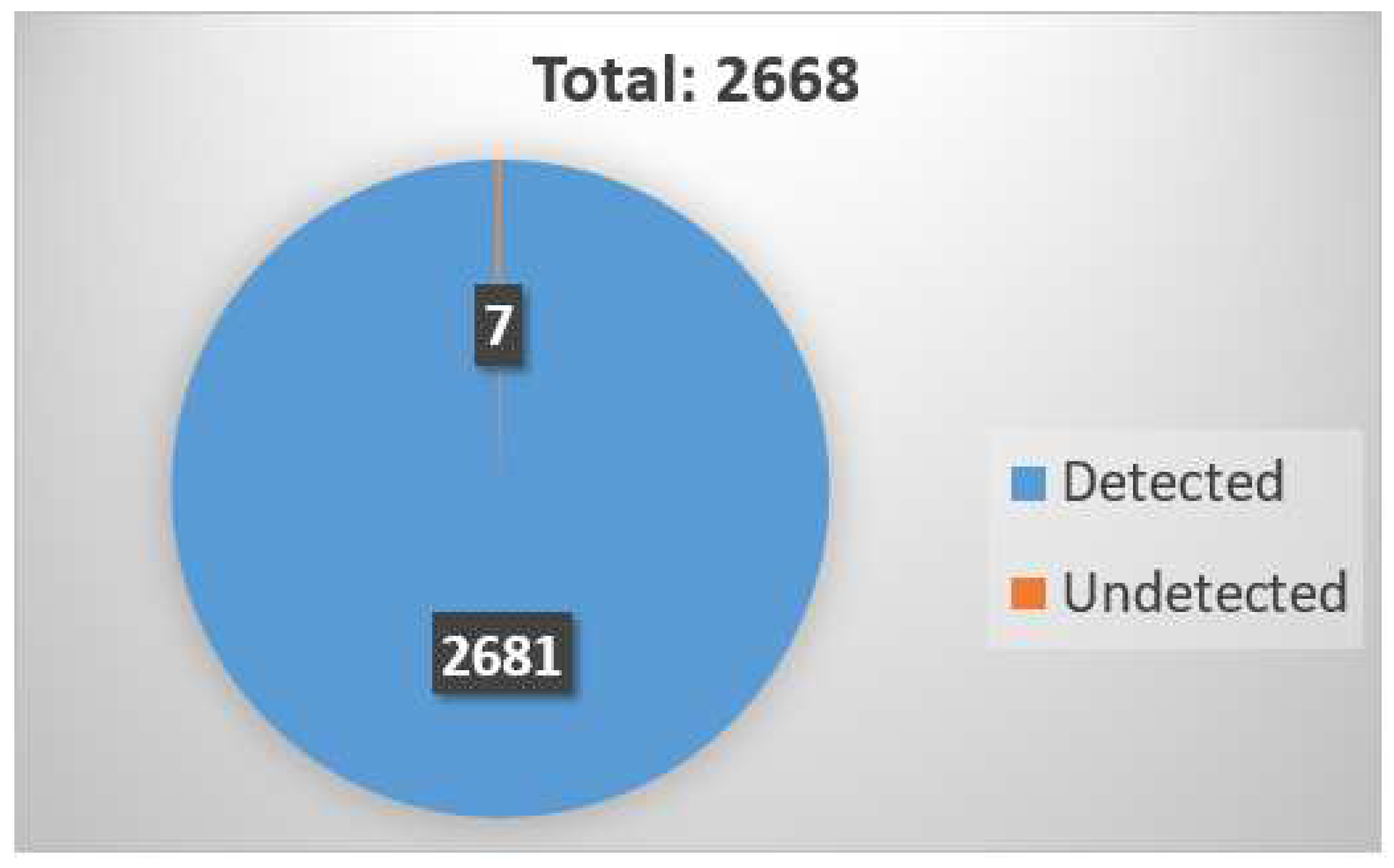

Case 1: In this case, we selected 2668 malware samples from VirusShare first, transferred these malware samples into fileless malware, and then executed these 2668 pieces of fileless malware. CoE’s file path was triggered to handle the fileless malware. Among these 2668 malware samples, CoE correctly recognized 2661 samples as malware and identified seven fileless malware samples as benign files. The detection rate is 99:73%, as show in

Figure 14. Out of the seven identified malware samples that were classified as harmless files, five of them were unable to be executed. One malware sample only printed a message. The rest tried to execute a program in the directory

tmp. All seven malware samples did not show malicious behaviors; hence, they should not be deemed malware.

[Result analysis]: Experimental results show that CoE can effectively detect fileless malware.

Case 2: We collected 15 pieces of Linux x86-64 shell code from Shell-storm Database [

24] to form 15 pieces of fileless malware. CoE’s text path was triggered to handle these pieces of fileless malware. CoE could suspend the execution of all these 15 pieces of fileless malware and obtain the related ELF files. But 8 of these 15 pieces of fileless malware are detected as viruses by VirusTotal. The detection rate is53:33% in this case.

Table 2 shows the types of shell code samples used in our experiments. And the detection rates of each kind of shell code.

[Result analysis]: As mentioned above, CoE could suspend the execution of all these 15 pieces of fileless malware and obtain the related ELF files. Hence, all CoE components functioned well. As a result, CoE can potentially protect a system against shell code attacks, even though CoE is designed to protect a system against fileless malware, not shell code attacks. Suppose the virus signature databases that CoE uses can add more shell code signatures, or we can create our own CoE shell code signature database. In that case, CoE’s shell code detection accuracy should be able to be improved a lot.

Case 3: Packing [

25] is a technique that compresses or encrypts malware samples to change the signatures of malware samples. Attackers often pack existing malware samples to create mutations of these malware samples to bypass antivirus engines’ detection. When a packed malware is executed, the related decompression or decryption code is first applied to the compressed/encrypted code. Then the decompressed/encrypted code is stored in a writable and executable area. Hence, executing packed malware will trigger the execution of CoE. CoE’s text path was triggered to handle these pieces of fileless malware. Our experiments use one hundred twelve pieces of the third kind of malware. As shown in

Figure 15, CoE can detect 70 packed malware samples among the 112 pieces. Hence, the detection rate is 62:5%.

[Result analysis]: The malware used in case 3’s experiments is the same as in case 1’s. Case 1’s experiments show that CoE can detect almost all tested fileless malware. But in case 3’s, the detection rate of CoE is only 62:5%. The reason is explained as follows. For a file called filetest, retrieved from VirusShare, case 1 used it directly. But case 3 changed its ELF header. So in case 1, CoE sent a complete filetest to VirusTotal. But in case 3, even the packed file received by VirusTotal has the same code segment as filetest, but the packed file has a different ELF header. The results show that some antivirus engines also use the ELF header of a file, instead of its code only, to determine whether a file is malware. Hence, similar to the conclusion we obtained in case 2’s result analysis (shell code case), adding signatures created by malicious machine code can only increase CoE’s detection rate for packed malware.

5.3. Efficiency Evaluation

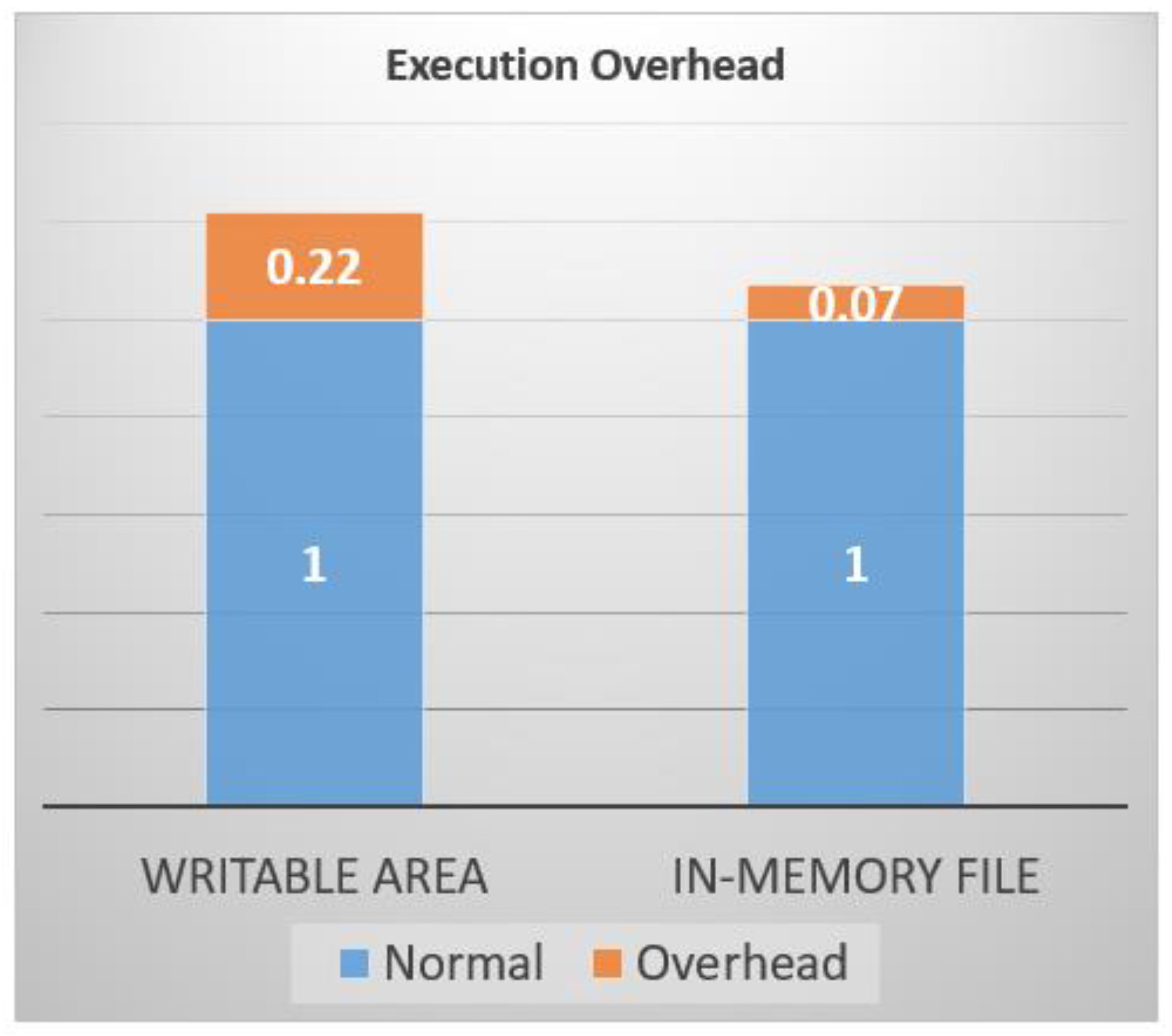

We made some experiments to get the execution overhead introduced by CoE. Since CoE influences the execution time of code stored in a writable and executable area and CoE memory area created by a system called

memfd_create(), we evaluated the performance overhead of executed code in these two areas.

Figure 16 shows that the performance overhead of executing code stored in a writable and executable area is 22%. However, for security and reliability reasons, a program’s code section is usually non-writable; hence, this overhead should not influence most programs.

Figure 16 also shows that the performance overhead of executing a file stored in the memory area created by a system called

memfd_create() is 7%, which is trivial.

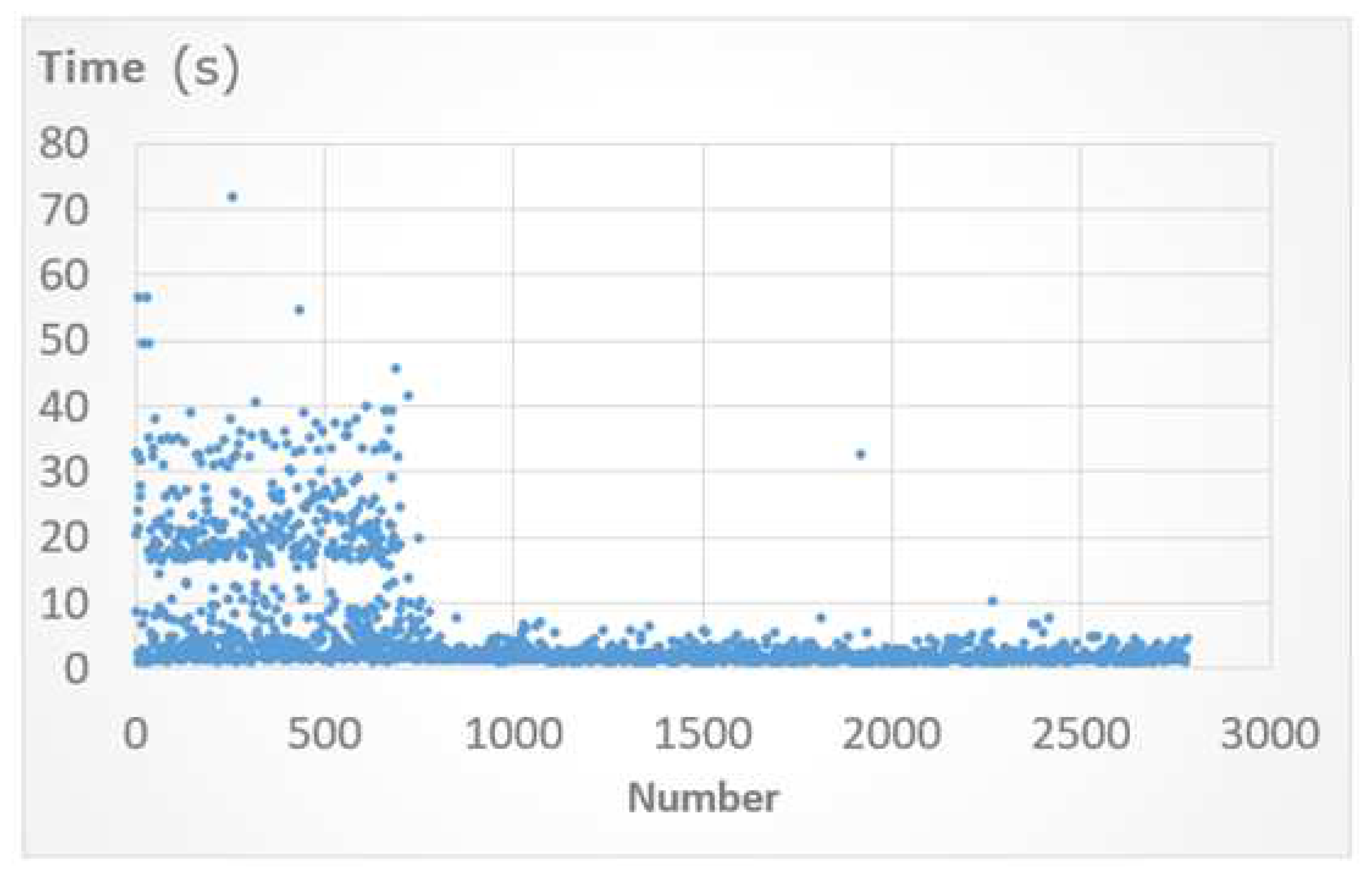

5.4. File Scanning Time Evaluation

The major performance overhead introduced by CoE comes from file scanning time, which includes the time that VirusTotal uses to analyze whether a file is malicious or benign and the time to transmit a file between a host and VirusTotal. When VirusTotal receives an analyzed file, it immediately sends back previous scanning results. When VirusTotal receives a file that VirusTotal did not analyze before, it analyzes the file first and sends back the scanning results. The latter case takes longer, but a person rarely encounters this situation. In the first type of experiment, we sent the same file that VirusTotal analyzed at different times and calculated the average file scanning time. As

Figure 17 shows, the average file scanning time is 4.71 seconds. In the second type of experiment, we sent different files that VirusTotal did not analyze before at other times and calculated the average file scanning time. As

Figure 18 shows, the average file scanning time is 80.1 seconds. The results show that file scanning time is a significant overhead. However, if we can cache the previous file scanning results, we only need to scan once for each file. We even can trigger the scan of related files when we install a program to solve this non-trivial file scanning time problem. Besides, instead of sending files to VirusTotal for scanning, using a local antivirus engine may also decrease the file scanning overhead.

6. Discussion

The CoE employs CPU hardware to initiate its execution when code is about to be executed from a memory area that is both writable and executable. From a logical standpoint, this is reasonable because it would be challenging for an attacker to inject code into a memory area that is not designated as writable. Usually, this is right. However, suppose an attacker utilizes a ptrace() system to complete code injection. In that case, code may be injected into a non-writable but executable memory area because ptrace() injects code in the kernel address space, and kernel address space code can write code into any part of the process's address space. But if we hook system call ptrace(), and whenever the system calls ptrace(), writes something into a non-writable but executable memory area, we can change the permissions in related vm-area as writable and executable to solve this problem. Besides, we plan to implement this function in the future, as experimental results show that CoE can extend its capability to protect a system against packed malware, even though CoE is designed to protect a system against fileless malware, not packed malware.

7. Conclusion

This paper proposes a solution to fileless malware called Check-on-Execution (CoE) in the Linux Kernel. Research shows that fileless malware has recently broken through the defense lines built by various antivirus engines to spread diverse malware, including notorious ransomware and malware used by crypto miners, to plenty of hosts. A traditional static analysis antivirus engine maintains a virus signature database. The engine must obtain the file first to check whether a file is malware. Then the engine abstracts the file’s signature and finally looks up its virus signature database to see whether the database contains the file’s signature. The file is malware if there is a match; otherwise, it is a normal program. Because after being installed, fileless malware only exists in the memory of a process which usually is a normal process providing services to users, traditional static analysis antivirus engines cannot handle it. After all, currently, antivirus engines even cannot obtain the code of fileless malware, let alone analyze the fileless malware. Besides, the memory content of a process changes continuously. Hence, it is important for a fileless malware detection solution to find the right time to collect the right data, i.e., the code of fileless malware. CoE uses CPU hardware and PTE entries in page tables to trigger its execution. Not only can this reduce work time, but also it is accurate. CoE is the kernel-based solution; hence, it does not need to worry its execution will be turned off by attackers, as what attackers do on antivirus engines [

27]. Experimental results show that CoE can effectively defend a system against fileless malware. Experimental results also show that even though CoE is not designed to protect a system against shell code attacks or packed malware attacks, after adding more malicious code-based signatures, CoE can potentially become an effective solution to these two dangerous, dangerous, and troublesome security threats.

References

- A. Alzuri, D. C. Andrade, Y. N. Escobar, and B. M. Zamora, “The growth of fileless malware,” 2019.

- A. D. Rayome. “Report: Fileless malware attacks 10x more likely to infect your machine than others (2017),” [Online]. Available: https://www.techrepublic.com/article/report-fileless-malware-attacks-10xmore-likely-to-infect-your-machine-than-others/, [Accessed: 20-Aug-2021].

- WatchGudrd, “New Research: Fileless Malware Attacks Surge by 900% and Cryptominers Make a Comeback, While Ransomware Attacks Decline,” [Online]. Available: https://www.globenewswire.com/en/newsrelease/2021/03/30/2201173/0/en/New-Research-Fileless-Malware-Attacks-Surge-by-900-and-Cryptominers-Make-a-Comeback-While-Ransomware-Attacks-Decline.html, [Accessed: 20-Aug-2021].

- Ben Nick, “Fileless attack detection for Linux in preview,” [Online]. Available: URL: https://azure.microsoft.com/zh-tw/blog/filelessattack-detection-for-linux-in-preview/, [Accessed: 20-Aug-2021].

- Stuart. In-memory-only elf execution (without tmpfs). (2017), [Online]. Available: https://magisterquis.github.io/2018/03/31/in-memory-only-elfexecution.html, [Accessed: 20-Aug-2021].

- Simon Floreza, Donald Castillo, and Mark Manahan, “Security101: Defending Against Fileless Malware,” [Online]. Available: https://www.trendmicro.com/vinfo/us/security/news/securitytechnology/security-101-defending-against-filelessmalware# documentexploits, [Accessed: 20-Aug-2021].

- I. Kara, "Fileless malware threats: Recent advances, analysis approach through memory forensics and research challenges," Expert Systems with Applications, p. 119133, 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. Khalid et al., "An insight into the machine-learning-based fileless malware detection," Sensors, vol. 23, no. 2, p. 612, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Karapetyants and D. Efanov, "A practical approach to learning Linux vulnerabilities," Journal of Computer Virology and Hacking Techniques, pp. 1-10, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Butt, Z. Ajmal, Z. I. Khan, M. Idrees, and Y. Javed, "An in-depth survey of bypassing buffer overflow mitigation techniques," Applied Sciences, vol. 12, no. 13, p. 6702, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lee, J. Kwak, J. Kang, Y. Jeon, and B. Lee, "Pspray: Timing {Side-Channel} based Linux Kernel Heap Exploitation Technique," in 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23), 2023, pp. 6825-6842.

- F. CyberSecurity. Elf in-memory execution. (2018), [Online]. Available: https://blog.fbkcs.ru/elf-in-memory-execution/, [Accessed: 30-Aug-2021].

- Sinha S., “Finding Command Injection Vulnerabilities. In: Bug Bounty Hunting for Web Security,” Apress, Berkeley, CA. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4842-5391-5 9, [Accessed: 20-Aug-2021]. [CrossRef]

- Fan Dang, Zhenhua Li, Yunhao Liu, Ennan Zhai, Qi Alfred Chen, Tianyin Xu, Yan Chen, Jingyu Yang, “Understanding Fileless Attacks on Linux-based IoT Devices with HoneyCloud,” Proceedings of the 17th Annual International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Services, June 2019.

- B.N. Sanjay, D.C. Rakshith, R.B. Akash, Dr.Vinay V. Hegde, “An Approach to Detect Fileless Malware and Defend its Evasive mechanisms, ” 2018 3rd International Conference on Computational Systems and Information Technology for Sustainable Solutions (CSITSS),” Bengaluru, India, 20-22 Dec. 2018.

- Sherif Saad, Farhan Mahmood, William Briguglio, Haytham Elmiligi, “JSLess: A Tale of a Fileless Javascript Memory-Resident Malware,” 15th International Conference, ISPEC 2019, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, November 26–28, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Luca Caviglione, Michał Chora´s, Igino Corona, Artur Janicki, Wojciech Mazurczyk, Marek Pawlicki, Katarzyna Wasielewska, ”Tight Arms Race: Overview of Current Malware Threats and Trends in Their Detection,”IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 5371-5396, 2021.

- R. Sihwail, K. Omar, and K. A. Zainol Ariffin, “Malware detection approach based on artifacts in memory image and dynamic analysis,” Applied Sciences, vol. 9, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- O. C. bookshelf, “Page fault exception handler.” (2020), [Online]. Available: https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man2/memfd create.2.html, [Accessed: 20-Aug-2021].

- S. Eranian and D. Mosberger. “How copy-onwrite really works.” (2002), [Online]. Available: https://www.informit.com/articles/article.aspx?p=29961&seqNum=5, [Accessed: 20-Aug-2021].

- S. Ninja. “Complete tour of pe and elf: Section headers.(2016),”[Online]. Available: https://resources.infosecinstitute.com/complete-tourof-pe-and-elf -part-5/, [Accessed: 20-Aug-2021].

- VirusTotal, Virustotal. (2019), [Online]. Available: https://www.virustotal.com/, [Accessed: 20-Aug-2021].

- Clam AntiVirus (ClamAV), [Online]. Available: Available https://www.clamav.net/, [Accessed: 20-Aug-2021].

- Shell-Storm, “Shellcodes database for study cases (2019)”, [Online]. Available: http://shell-storm.org/shellcode/, [Accessed: 20-Aug-2021].

- Abhijit Mohanta and Anoop Saldanha (2020), “Malware Analysis and Detection Engineering,” Springer. [CrossRef]

- VirusShare.com. Virusshare.com. (2019), [Online]. Available: https://virusshare.com/, [Accessed: 20-Aug-2021].

- Fu-Hau Hsu, Min-Hao Wu, Chang-Kuo Tso, Chi-Hsien Hsu, Chieh-Wen Chen, “Antivirus Software Shield against Antivirus Terminators,” IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, VOL. 7, NO.5, Pages 1439 - 1447, October 2012.

Figure 1.

Possible injection and execution flows of fileless malware. a, b, and c above related arrows represent paths a, b, and c, respectively.

Figure 1.

Possible injection and execution flows of fileless malware. a, b, and c above related arrows represent paths a, b, and c, respectively.

Figure 2.

Fileless malware attack example.

Figure 2.

Fileless malware attack example.

Figure 3.

Execution steps of static analyses.

Figure 3.

Execution steps of static analyses.

Figure 4.

System structure of CoE.

Figure 4.

System structure of CoE.

Figure 5.

NX bit of a PTE.

Figure 5.

NX bit of a PTE.

Figure 6.

Before copy-on-write.

Figure 6.

Before copy-on-write.

Figure 7.

After copy-on-write.

Figure 7.

After copy-on-write.

Figure 8.

Before the Execution of CoE Code Extractor.

Figure 8.

Before the Execution of CoE Code Extractor.

Figure 9.

After the execution of CoE Code Extractor, if the page is both executable and executable, the code that will be executed is benign.

Figure 9.

After the execution of CoE Code Extractor, if the page is both executable and executable, the code that will be executed is benign.

Figure 10.

Flowchart of the file path.

Figure 10.

Flowchart of the file path.

Figure 11.

Flowchart of the text path.

Figure 11.

Flowchart of the text path.

Figure 12.

Content of file safe_code.c.

Figure 12.

Content of file safe_code.c.

Figure 13.

Content of file unsafe_code.c.

Figure 13.

Content of file unsafe_code.c.

Figure 14.

Detection accuracy of CoE for fileless malware.

Figure 14.

Detection accuracy of CoE for fileless malware.

Figure 15.

The detection rate of packed malware samples.

Figure 15.

The detection rate of packed malware samples.

Figure 16.

Execution performance overhead introduced by CoE.

Figure 16.

Execution performance overhead introduced by CoE.

Figure 17.

Average file scanning time for a file that VirusTotal has analyzed.

Figure 17.

Average file scanning time for a file that VirusTotal has analyzed.

Figure 18.

Average file scanning time for files that were not analyzed by VirusTotal before.

Figure 18.

Average file scanning time for files that were not analyzed by VirusTotal before.

Table 1.

CPU, OS, AND LINUX KERNE SPEICFICATIONS.

Table 1.

CPU, OS, AND LINUX KERNE SPEICFICATIONS.

| CPU |

3.4GHZ AMD Ryzen 7 1700X CPU with 8 cores |

| OS |

Ubuntu 18.04 |

| Kernel |

Linux Kernel 4.20.3 |

Table 2.

Detection rates of fileless malware created by shell code.

Table 2.

Detection rates of fileless malware created by shell code.

| Shell code form |

# of detected shell code samples |

# of total shell code samples |

detection rate |

| Execute("/bin/sh") |

2 |

4 |

50% |

| Connect Back Shell |

3 |

7 |

42.85% |

| Execute("shutdown -h now") |

1 |

2 |

50% |

| Add users with passwd |

1 |

1 |

100% |

| Execute("/sbin/pagetables -F") |

1 |

1 |

100% |

| Total |

8 |

15 |

53.33% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).