Submitted:

16 August 2023

Posted:

18 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1)

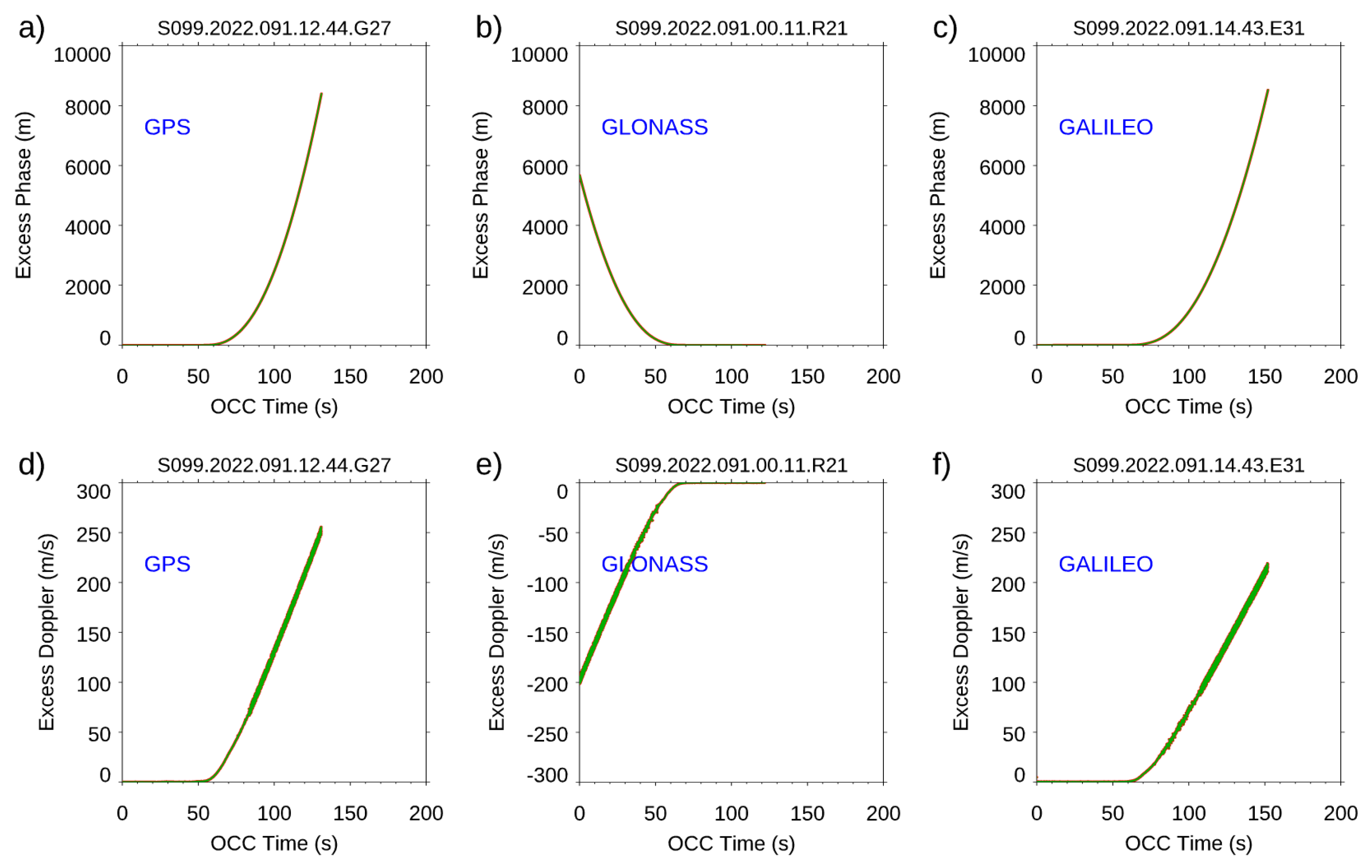

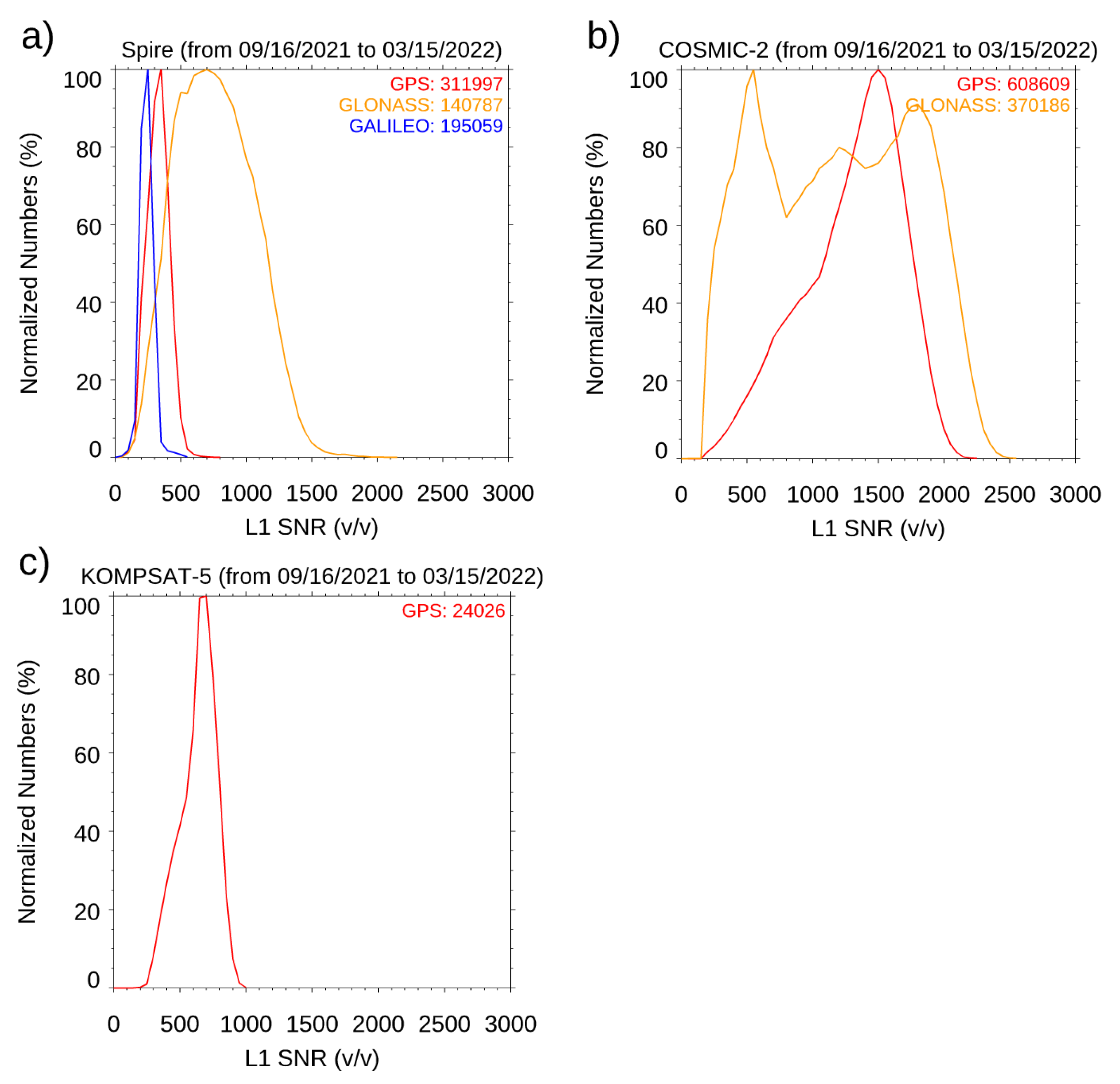

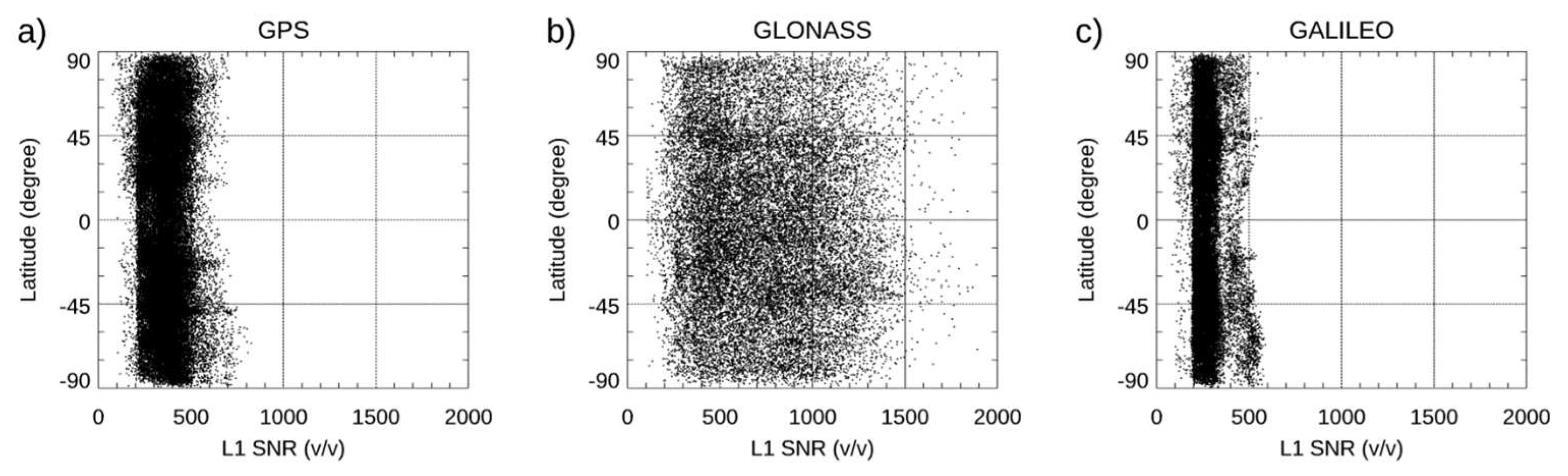

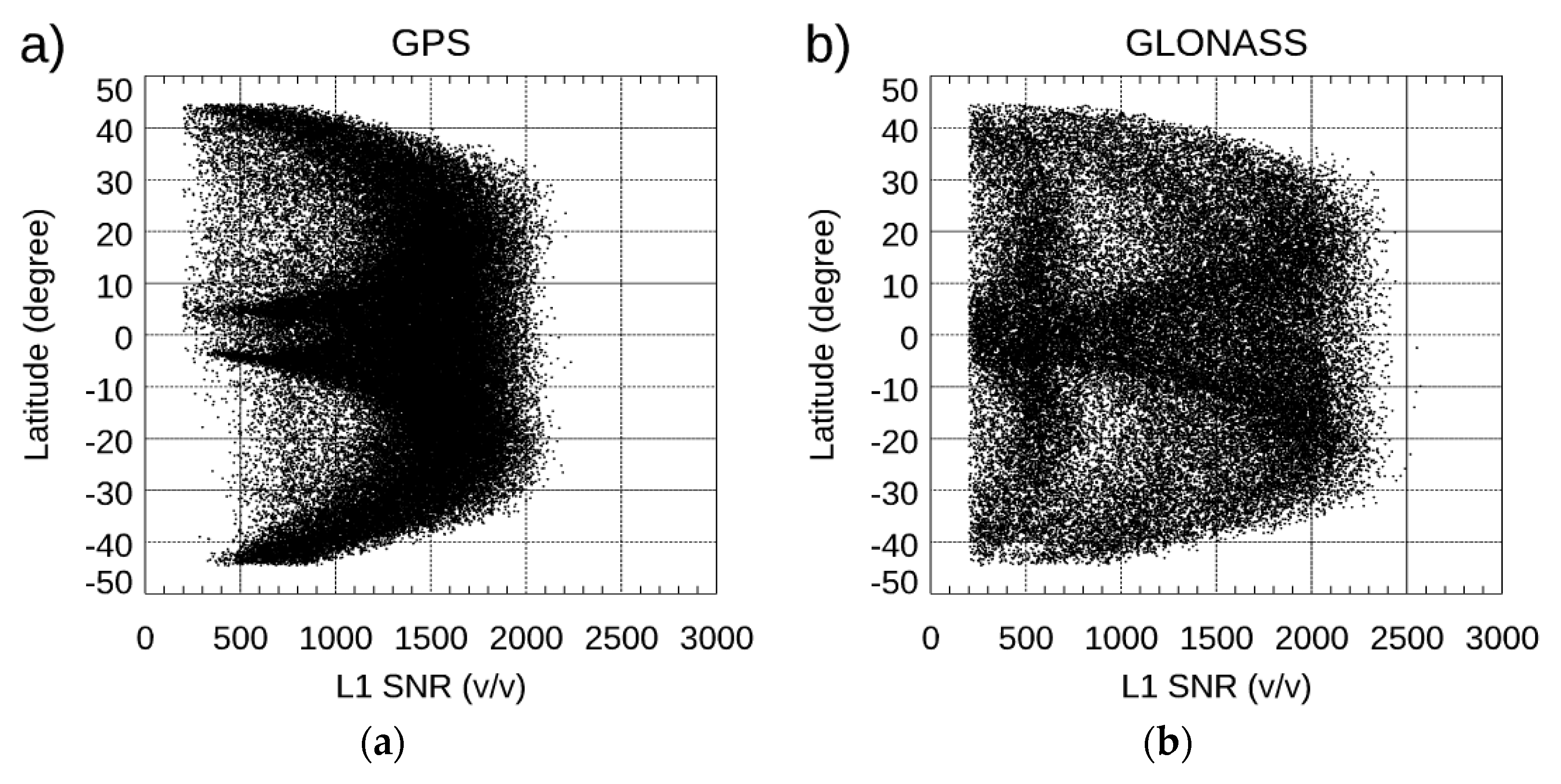

- Does lower Signal-Noise-Ratio (SNR) commercial CubeSats RO data lead to lower precision and more significant observation errors? The SNR is defined as the magnitude of the RO signals divided by the noise level from that receiver in the voltage-to-voltage unit (V/V). The SNR of the RO signal is one of the critical parameters to indicate the quality of RO measurements (i.e., time delay and excess phases) and L2 data products (i.e., bending angle (BA), refractivity, temperature, and moisture profiles). When RO signals are stronger, or the noise level is smaller, the magnitude of the SNR will be larger, which may indicate an improved observation quality. While Formosa Satellite Mission 3–Constellation Observing System for Meteorology, Ionosphere, and Climate (COSMIC-1 hereafter) and COSMIC-2 used an antenna of 2 feet, the antenna from CubeSat is only 1 foot. Figure 1 depicts the SNR histogram of Spire, COSMIC-2, and KOMPSAT-5 for the corresponding emitters. The sample numbers are normalized to the maximum number of the SNR bin. With the TGRS receiver, COSMIC-2 has a larger mean SNR than Spire and KOMPSAT-5. The mean COSMIC-2 L1 SNR ranges from 250 to 2500 V/V [31,32], and the L1 SNR for Spire ranges from 200 V/V to 1500 V/V, lower than those from COSMIC-2 (Figure 1). The mean L1 SNR for KOMPAST-5 is 570 V/V. With higher SNR than other RO missions, COSMIC-2 is expected to penetrate deeper into the lower troposphere [30]. With such a smaller antenna size for the Spire, one might expect the detected SNR to be much smaller than those from a larger antenna, which may lead to higher measurement and retrieval uncertainty. The antenna’s geometry may also influence the SNR distribution (see Section 2). The RO signals received from different receivers may also introduce extra retrieval uncertainty [31,32,33].

- 2)

- Does lower SNR Spire RO data lead to less accurate retrieval results? Whether the RO data products derived from lower SNR signals obtained from the commercial CubeSats are as accurate as those from high SNR signals is a significant concern for the RO community and climate and atmospheric scientists. The causes of the retrieval uncertainty may include receiver quality, antenna geometry, the accuracy of Precise Orbit Determination (POD) estimation, L0 to L1a processing, L1a-L1b (excess phase) processing, and L1b-L2 (bending angle and refractivity profiles) processing [33]. Because RO data quality and retrieval uncertainty may also be affected by atmospheric conditions, especially in the lower troposphere, assessing RO data accuracy and identifying the accuracy uncertainty from different RO missions is still a significant challenge.

- 3)

- How to optimize Spire RO data in the NWP system through data assimilation? As mentioned above, because RO bending angle and refractivity uncertainty, especially in the lower troposphere, are highly related to the atmospheric condition, we must carefully examine the observation uncertainty for each RO mission to use RO data optimally in the NWP through data assimilation (DA). An accurate estimate of retrieval uncertainty is also critical for optimizing the RO impacts in the NWP through the data assimilation system [1,2].

2. Data

2.1. Spatial and Local Time Distribution of Spire and Other RO Missions

2.2. Spire Signal-to-Noise (SNR) Latitudinal Distribution

2.3. STAR processed Spire data, Global Radiosonde data, and Reanalysis Data

3. SRO Methodology

4. Assessment of Spire Data Characteristics

4.1. The Lowest Penetration Height

4.2. Precision

4.3. Stability

5. Quantify the Spire Retrieval Accuracy and Uncertainty

5.1. Initial Comparison of UCAR Spire Products with STAR Spire Retrievals

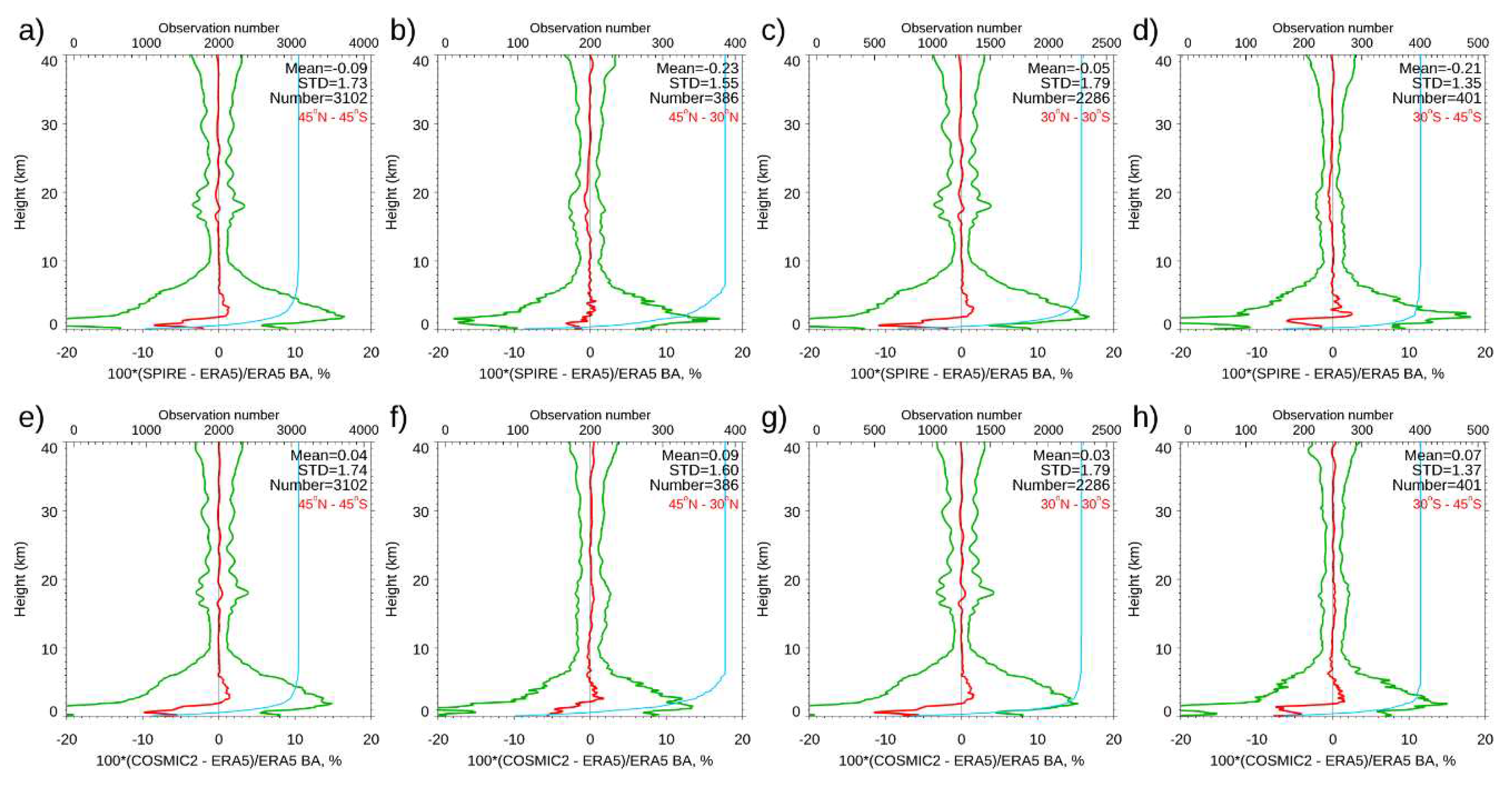

5.2. Assessment of the Spire Bending Angle Accuracy by Comparing ERA-5

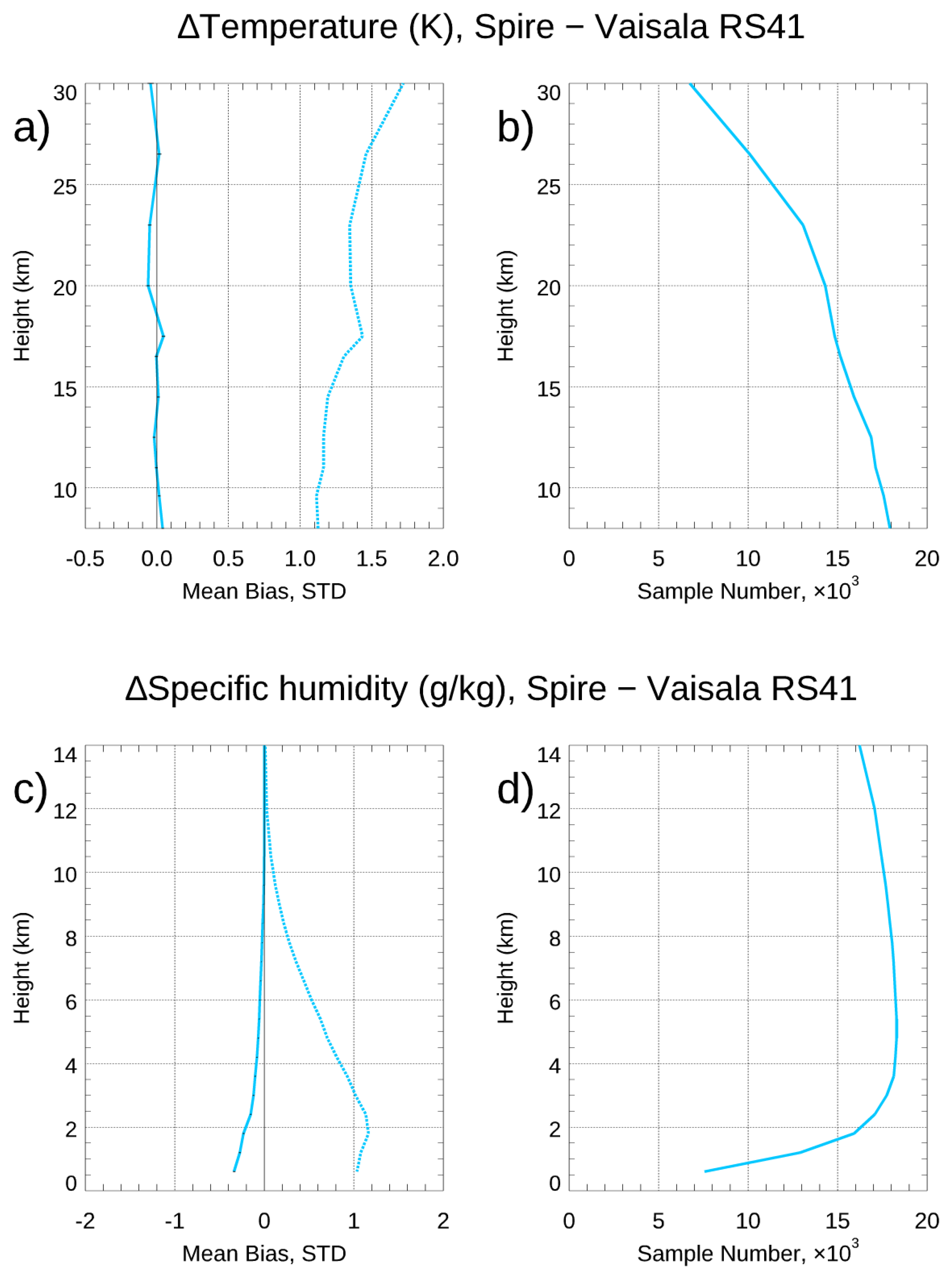

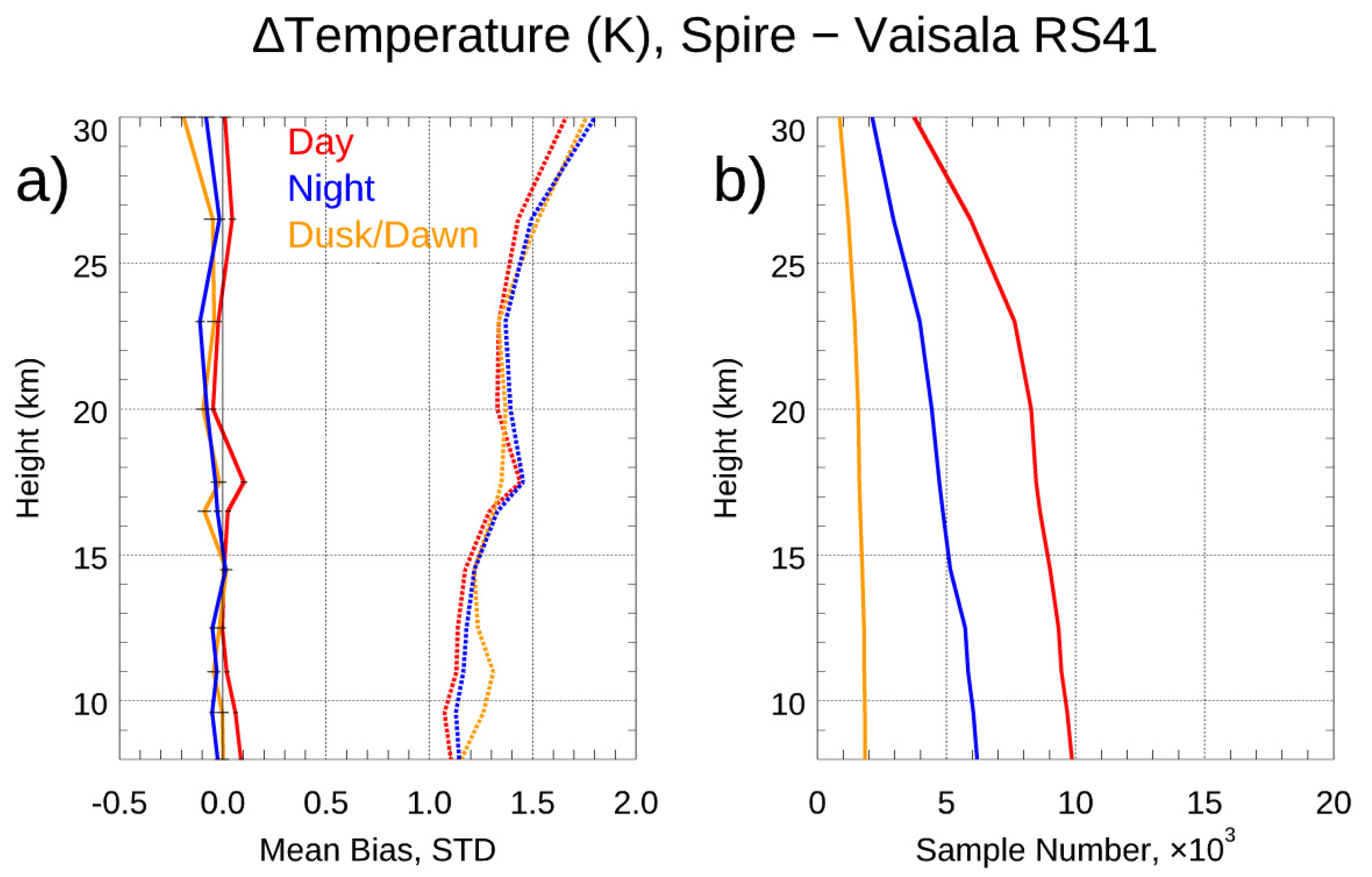

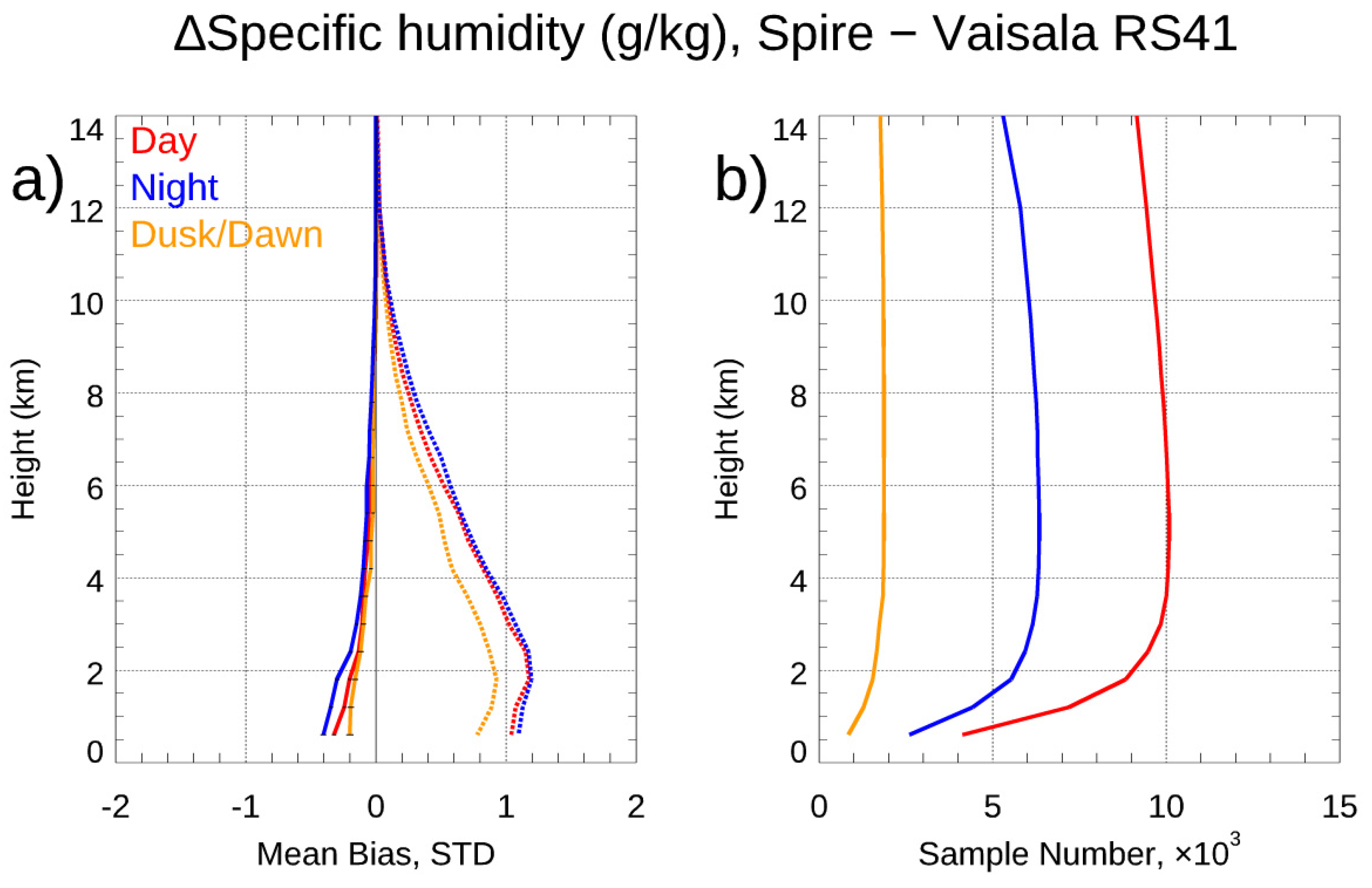

5.3. Assessment of Spire Temperature and Water Vapor Accuracy by Comparing to RS41 Radiosonde Observation

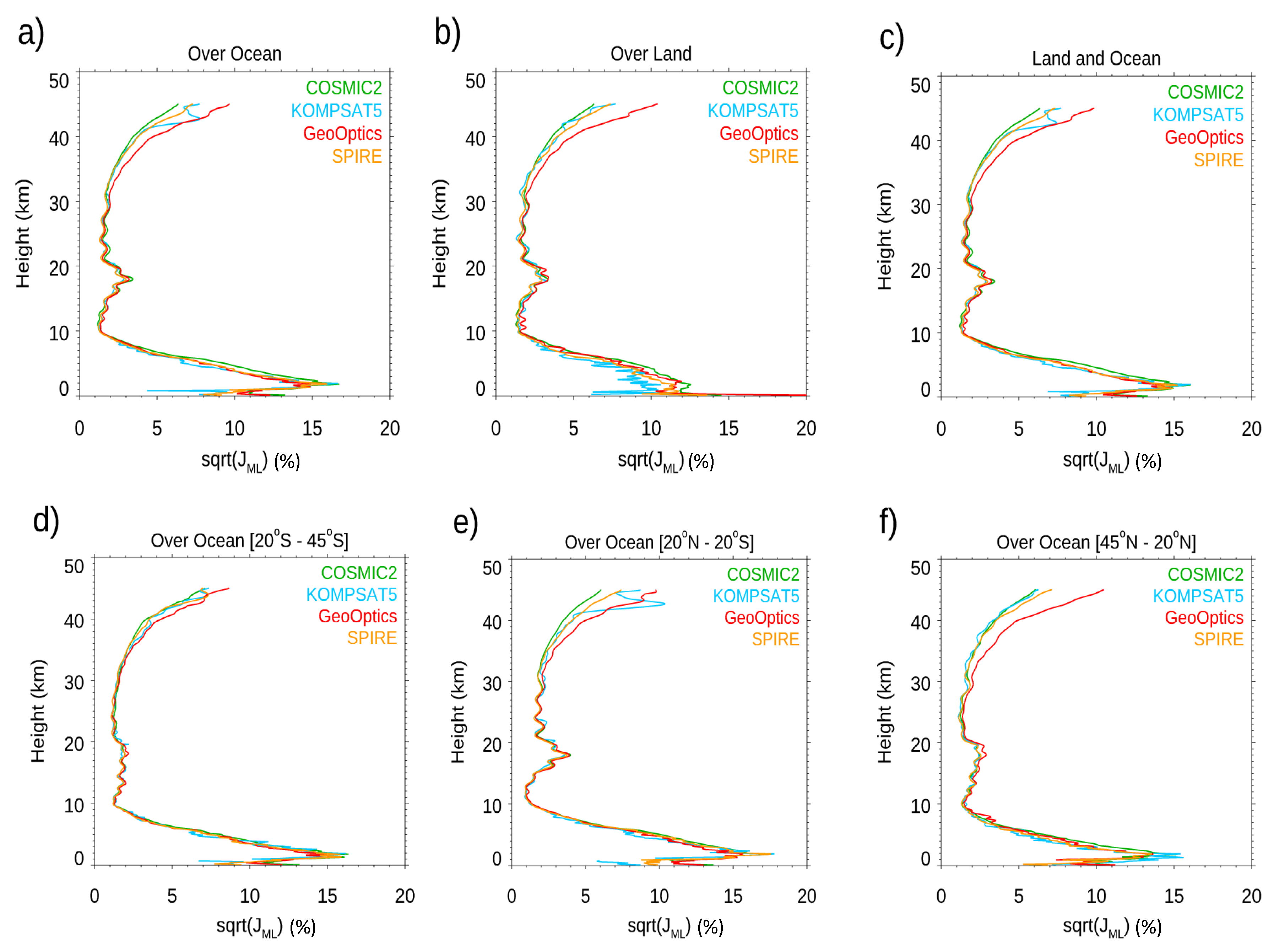

6. Estimates of the Error Covariance Matrix for NWP Data Assimilation

7. Conclusions, Discussions, and Future Work

- 1)

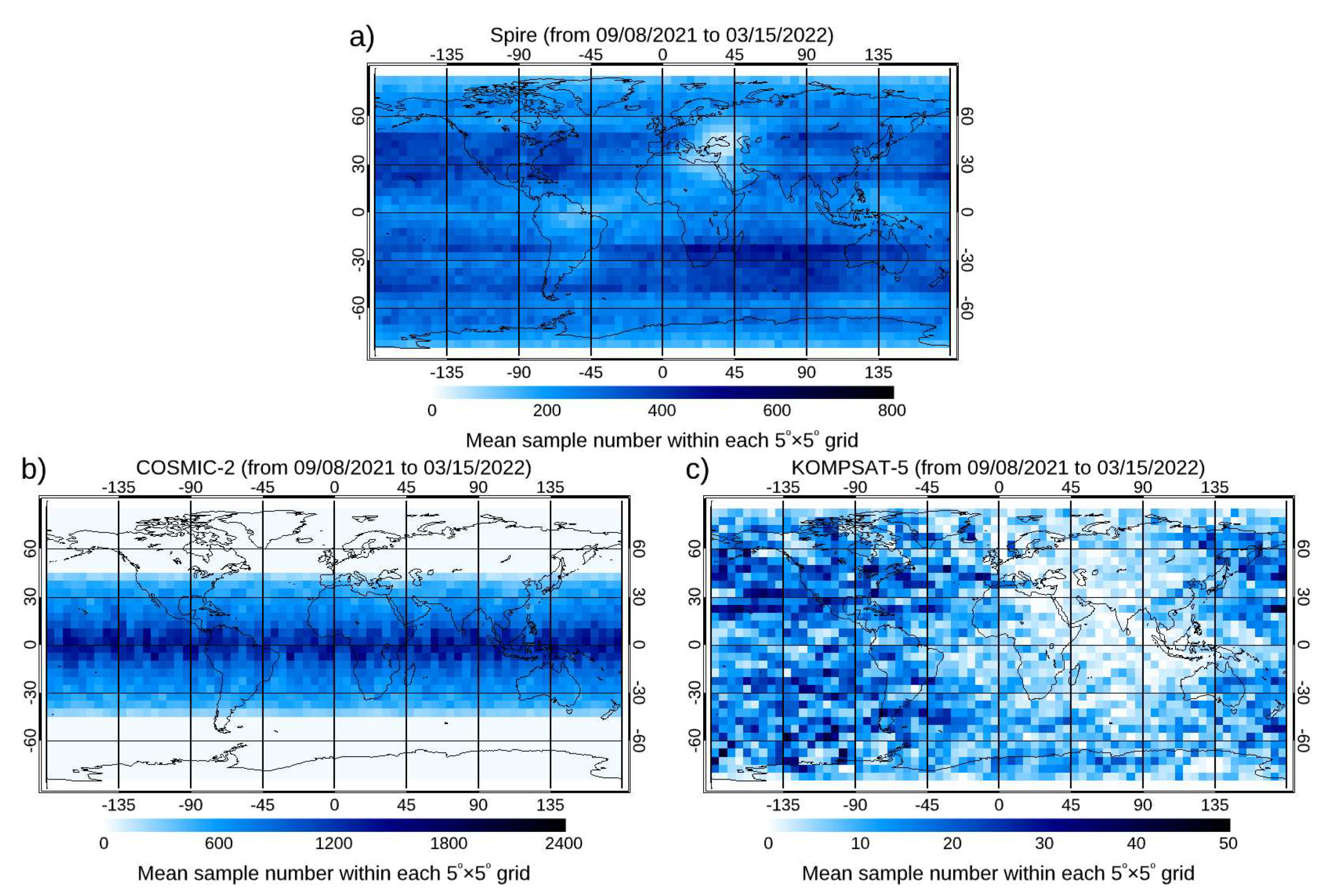

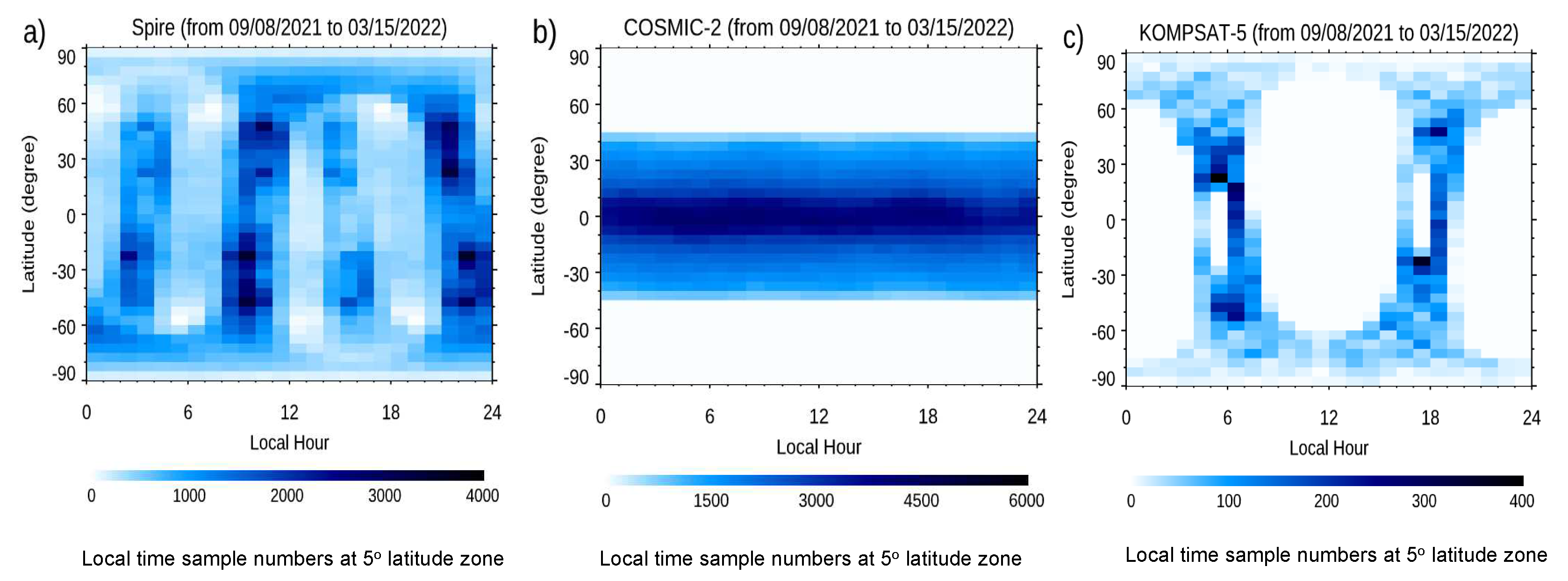

- The spatial and temporal coverage. Spire has close to 30 satellites at LEO orbits during the DO3 and DO4. Although the complete global Spire RO occultation is around 20K per day during the performance periods, CWDP purchased about 3000 Spire occultation profiles per day during the DO3 and 5500 Spire per day in DO4. While COSMIC-2 has an inclination angle of 24o, Spire is at the Sun-synchronized orbits. While Spire data cover the globe and are distributed relatively evenly across all latitudes, COSMIC-2 observation can cover all latitudes within [45oS, 45oN]. The Spire has observations peaking local time ranges in 2-3, 9-10, 14-15, and 21-22, while KOMPSAT5 observation peaking local time is located at 6 and 18, and COSMIC-2 observations are independent of the local time.

- 2)

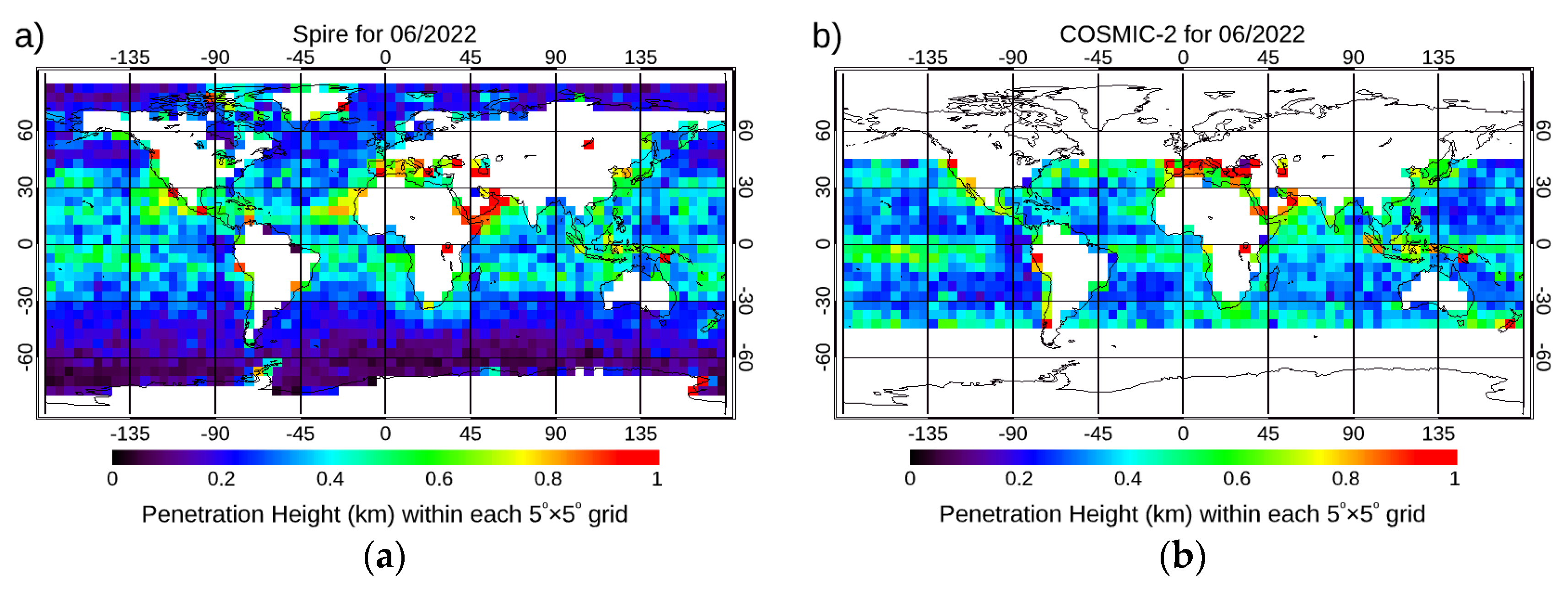

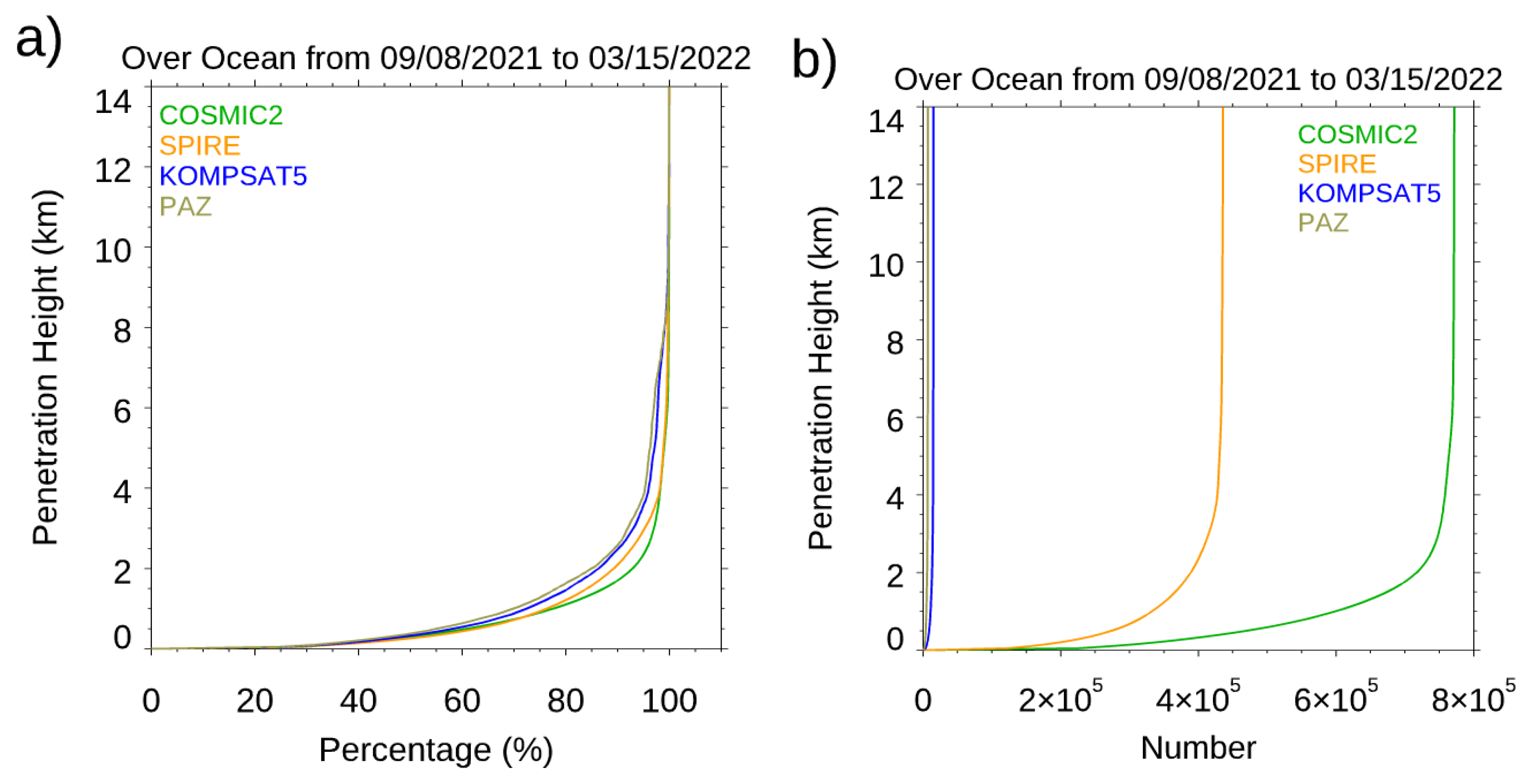

- The effect of SNR on Spire data penetration. The lowest penetration height is an essential indicator of RO data quality. The lowest penetration height of RO tracking is usually related to the data’s SNR and the atmosphere’s dryness. Although with lower SNR in general, the pattern of the lowest penetration height for Spire is similar to those for COSMIC-2. The Spire and COSMIC-2 penetrate heights are around 0.6 to 0.8 km altitude at the tropical oceans. We also compared the lowest penetration height of 80% of the total data for different RO missions at different latitudinal zones. GeoOptics and Spire have lower penetration heights (for 80% of the total data) than COSMIC-2 at latitudinal zones [45oS, 30oS] and [30oN, 45oN]. This may be owing to COSMIC-2 SNR being lower at latitudinal zones [45oS, 30oS] and [30oN, 45oN].

- 3)

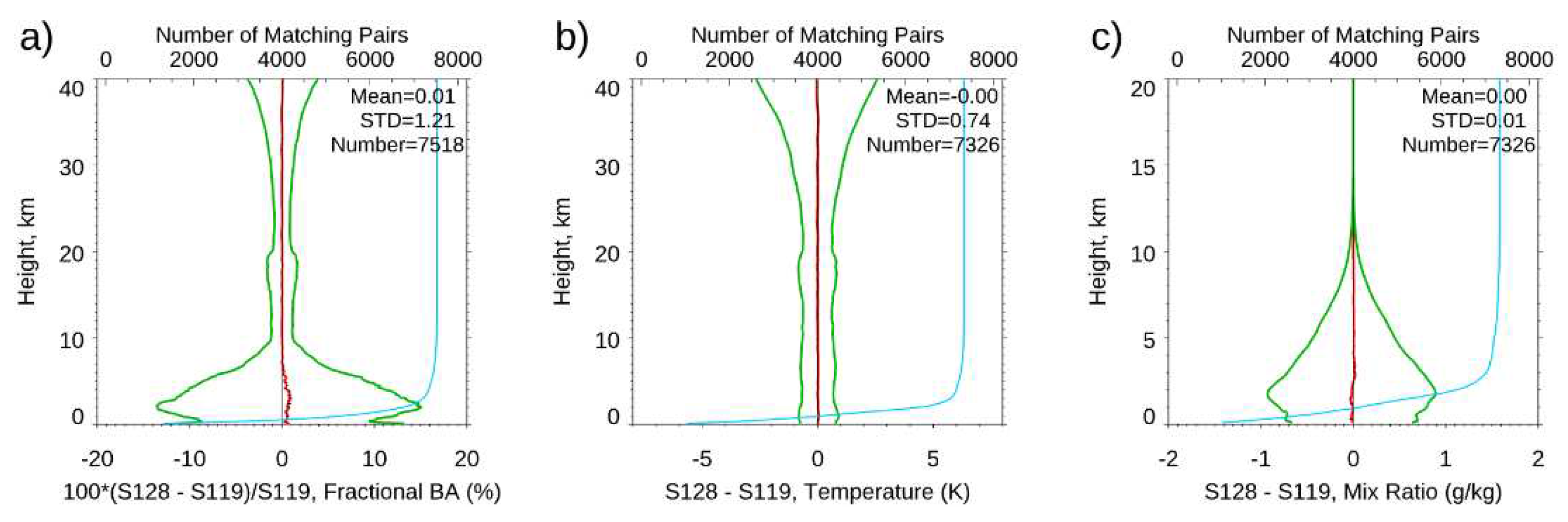

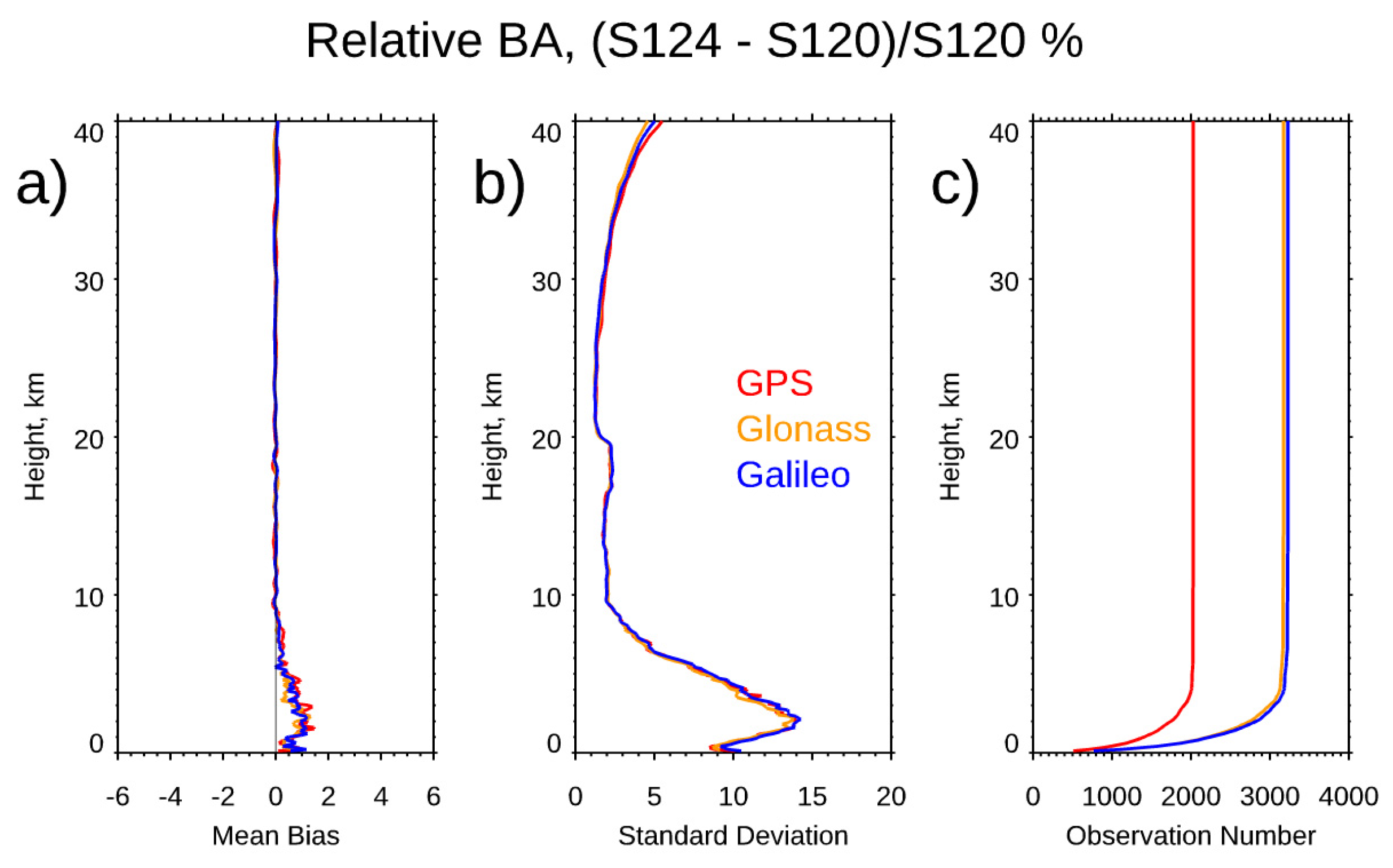

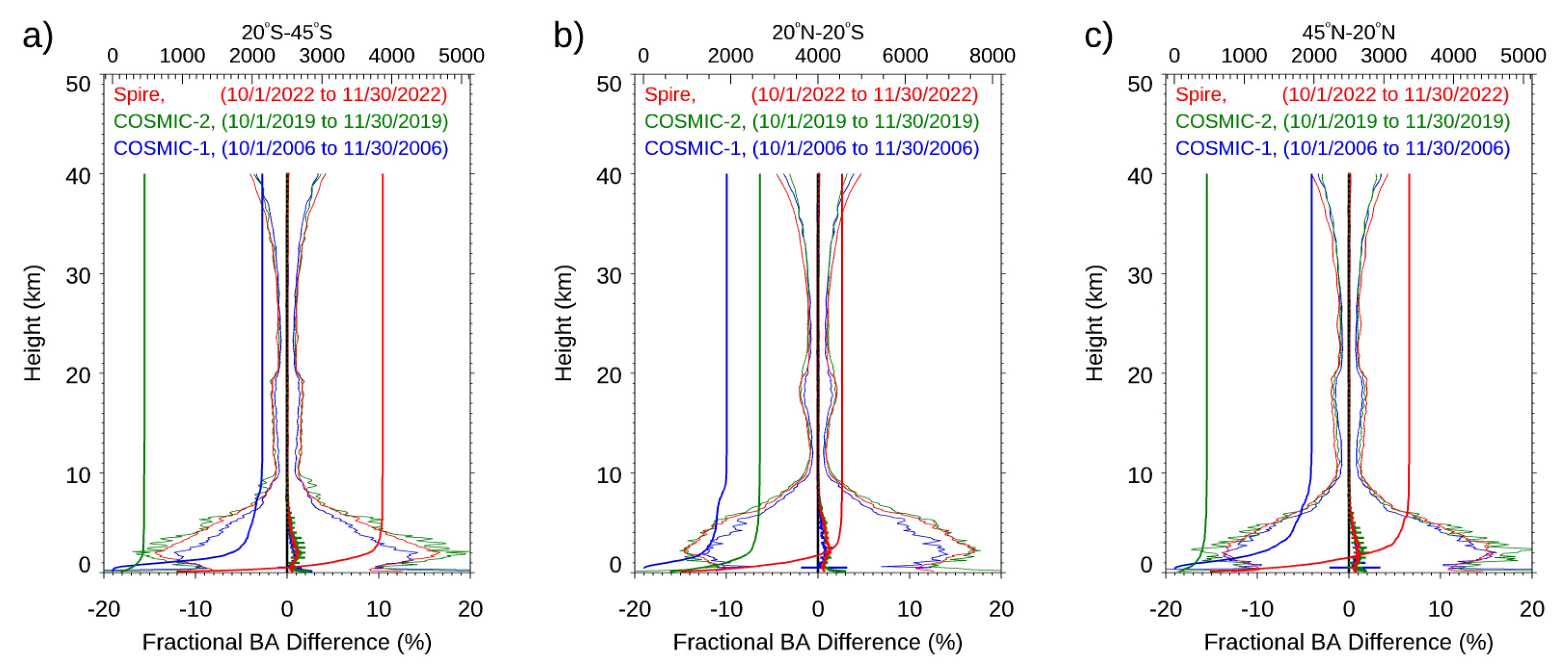

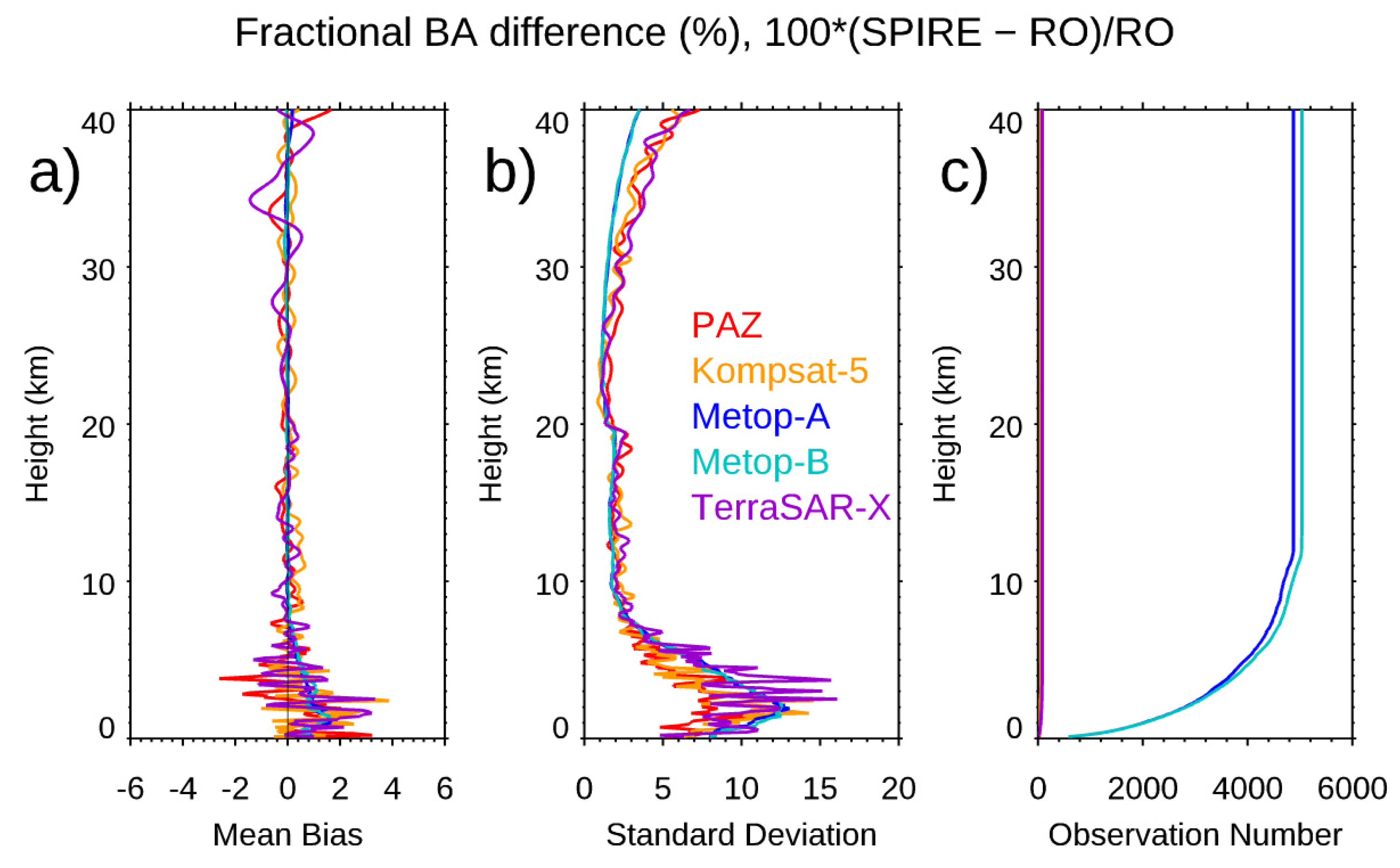

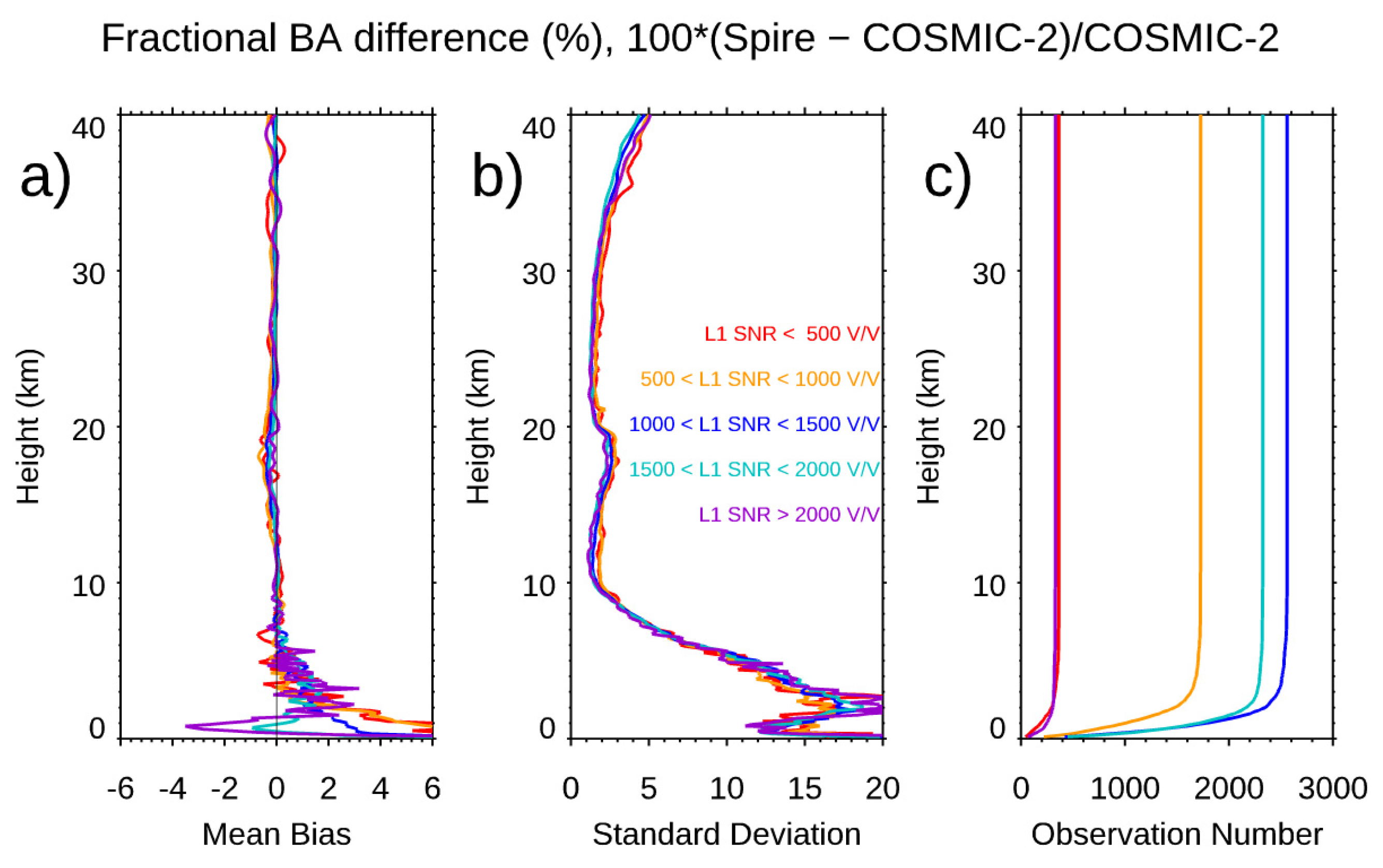

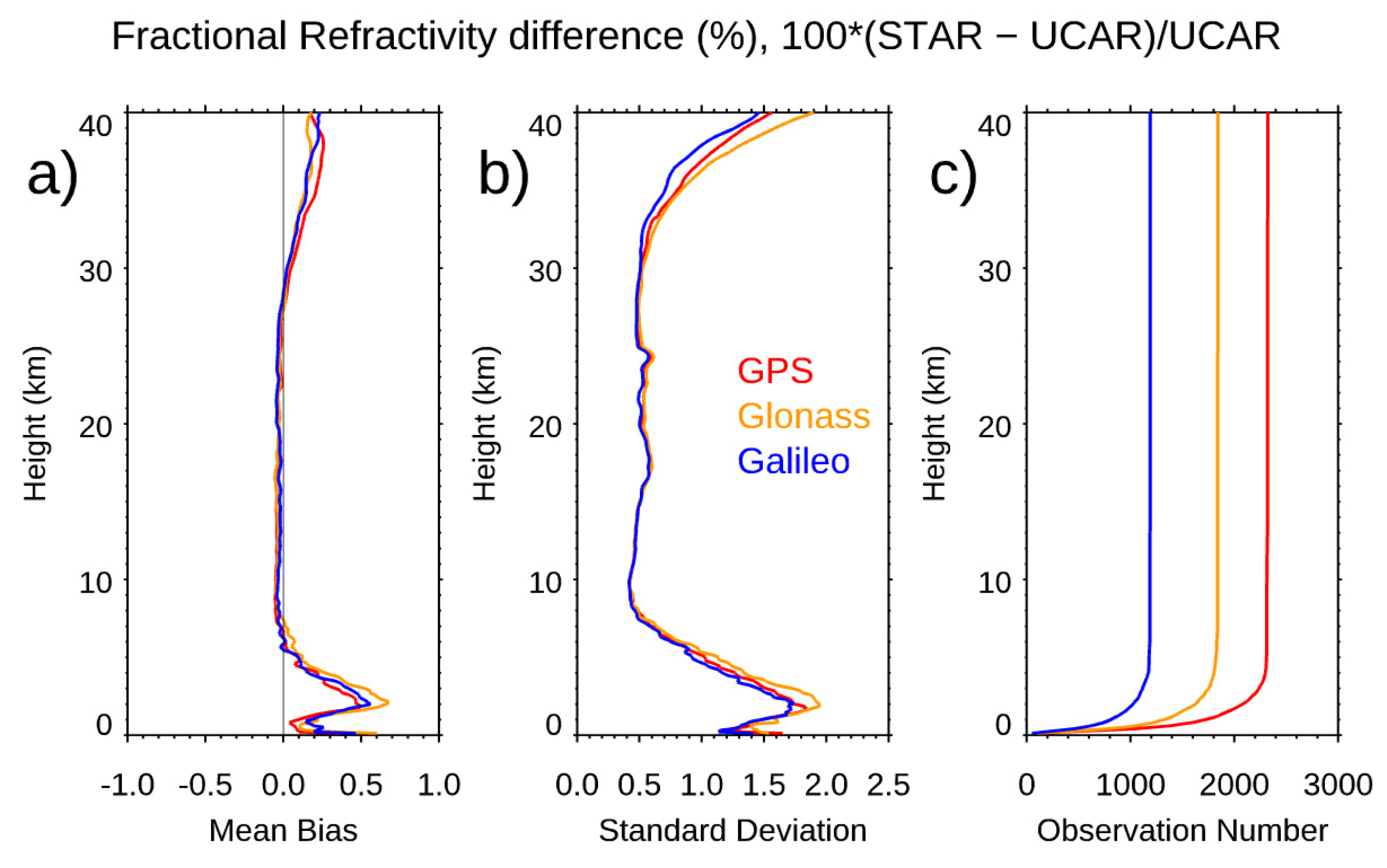

- The Spire data precision and stability. We used the Spire-Spire SRO pairs to quantify the Spire precision for bending angle, dry temperature, and water vapor mixing ratio. Results showed that the mean differences are very close to zero from the surface to 40 km altitude for all three physical quantities. The standard deviations from the bending angle, dry temperature, and water vapor mixing ratio are similar to those from other RO missions, such as COSMIC-2 and COSMIC-1. We also compare the fractional mean BA difference for Spire S124 and S120 from surface to 40 km altitudes but separated with GPS, GLONASS, and GALILEO, respectively. Although the SNRs from different emitters ranges are different, the mean difference for GPS, GLONASS, and GALILEO are all close to zero with the STD of 1.81, 1.78, and 1.78, respectively. We also compared the precision of COSMIC-1 (SRO pairs collected from 2006) and COSMIC-2 (SRO pairs collected from 2021) and compared with those from Spire (SRO pairs collected from 2022). All comparisons are within [45oN-45oS]. We found that COSMIC-2 STDs over mid-latitude are slightly more significant than those from Spire, which may be owing to their lower SNR over the same regions. Although it was not shown in this paper, the receiver quality for different flight modules is very close. Although using slightly different receivers, the precision of Spire STRASP receivers is of the same quality as those of COSMIC-2 TGRS receivers.

- 4)

- The effect of SNR on Spire retrieval accuracy. The UCAR Spire retrievals are consistent with those from STAR-independent derived BA retrievals. The independent statistical analysis and validation from ERA5 and direct bending angle profile comparison from these SRO cases above 35 km suggest: i) RO bending angle profiles retrieved from GPS satellites are, in general, better than those from GLONASS satellites; ii) Significant uncertainty exists for RO bending angle profiles from GLONASS, which may indicate potential RO phase issue related to the clock, residual ionospheric effects, receiver noise, and orbit determination errors for GLONASS. We validated Spire temperature and water vapor profiles by comparing them with collocated radiosonde in-situ data. Generally, over the height region between 8 km and 16.5 km, the RS41 RAOB matches Spire temperature profiles very well with temperature biases < 0.02 K. Over the height range from 17.8 to 26.4 km, the temperature biases are ~-0.034 K with RS41 RAOB being warmer.

- 5)

- Estimates of the error covariance matrix for NWP. Below 9 km, the RO observation errors increase with decreasing height and peak at around 2 km. For all Spire, COSMIC-2, KOMPSAT-5, and GeoOptics missions, the lower troposphere peak value over the ocean (~15%) is more significant than that over land (~12%). These significant errors in the lower troposphere may result from greater RO retrieval uncertainty relative to the middle and upper troposphere due to multipath propagation and a smaller SNR over the mid-latitudes for COSMIC-2. The COSMIC-2 retrieval uncertainty is slightly more significant over the oceans at the mid-latitudes (45oN-30oN and 30 oS-45oS), which may also be owing to COSMIC-2 SNR being lower at those latitudinal zones.

Acknowledgments

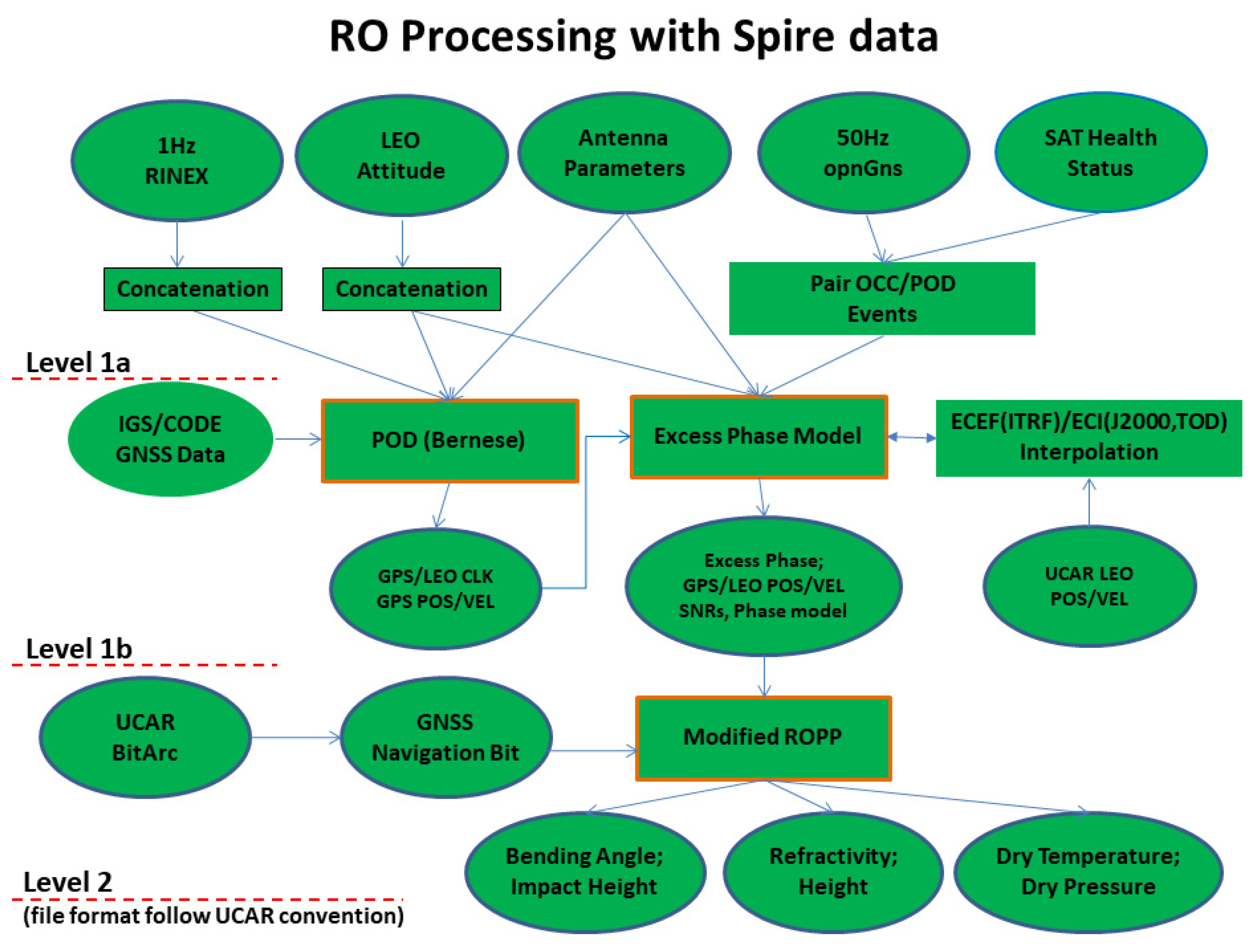

Appendix A. STAR Spire Data Products

References

- Anthes, R.A.; Bernhardt, P.A.; Chen, Y.; Cucurull, L.; Dymond, K.F.; Ector, D.; Healy, S.B.; Ho, S.-P.; Hunt, D.C.; Kuo, Y.; et al. The COSMIC/FORMOSAT-3 Mission: Early Results. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2008, 89, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-P.; Anthes, R.A.; Ao, C.O.; Healy, S.; Horanyi, A.; Hunt, D.; Mannucci, A.J.; Pedatella, N.; Randel, W.J.; Simmons, A. The COSMIC/FORMOSAT-3 Radio Occultation Mission after 12 Years: Accomplishments, Remaining Challenges, and Potential Impacts of COSMIC-2. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 2020, 101, E1107–E1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, B.R.; Dutton, E.J. Radio Meteorology. National Bureau of Standards Monogr., no. 92; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1966; p. 435. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, S.-P.; Goldberg, M.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Zou, C.-Z.; Shiau, W. Calibration of Temperature in the Lower Stratosphere from Microwave Measurements Using COSMIC Radio Occultation Data: Preliminary Results. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 2009, 20, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-P.; Zhou, X.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Hunt, D.; Wang, J.-H. Global Evaluation of Radiosonde Water Vapor Systematic Biases using GPS Radio Occultation from COSMIC and ECMWF Analysis. Remote Sens. 2010, 2, 1320–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Teng, W.; Ho, S.; Kuo, Y. Global variation of COSMIC precipitable water over land: Comparisons with ground-based GPS measurements and NCEP reanalyses. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 5327–5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, W.-H.; Huang, C.-Y.; Ho, S.-P.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Zhou, X.-J. Characteristics of global precipitable water in ENSO events revealed by COSMIC measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 8411–8425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, R.; Randel, W.J.; Ho, S.-P.; Neubert, T.; Syndergaard, S. Thermal structure of intense convective clouds derived from GPS radio occultations. Atmospheric Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 5309–5318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, R.; Ho, S.-P.; Randel, W.; Syndergaard, S.; Neubert, T. Tropical cyclone cloud-top height and vertical temperature structure detection using GPS radio occultation measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 5247–5259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.H.; Li, J.; Menzel, P.; Borbas, E.; Ho, S.-P.; Li, Z. Impact of Sampling Biases on the Global Trend of Total Precipitable Water Derived from the Latest 10-Year Data of COSMIC, SSMIS and HIRS Observations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018, 124, 6966–6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Ho, S.-P.; Sokolovskiy, S. The Structure and Evolution of Madden- Julian Oscillation from FORMOSAT-3/COSMIC Radio Occultation Data. J. Geophys. Res. 2012, 117, D22108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, M.; Lockhoff, M.; Shi, L.; August, T.; Bennartz, R.; Brogniez, H.; Calbet, X.; Fell, F.; Forsythe, J.; Gambacorta, A.; et al. The GEWEX water vapor assessment: Overview and introduction to results and recommendations. Remote Sens. 2018, 11, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mears, C.; Ho, S.P.; Wang, J.; Huelsing, H.; Peng, L. Total Column Water Vapor [In “States of the Climate in 2018“]. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 2019, 98, S24–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mears, C. ; J. Wang, J.; Ho, S.P.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, X. Total Column Water Vapor [In “States of the Climate in 2020”]. Bul. Amer. Meteor. Sci. 2021, in press.

- Rieckh, T.; Anthes, R.; Randel, W.; Ho, S.-P.; Foelsche, U. Tropospheric dry layers in the tropical western Pacific: comparisons of GPS radio occultation with multiple data sets. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2017, 10, 1093–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckh, T.; Anthes, R.; Randel, W.; Ho, S.-P.; Foelsche, U. Evaluating tropospheric humidity from GPS radio occultation, radiosonde, and AIRS from high-resolution time series. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2018, 11, 3091–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-Y.; Li, J.; Ho, S.-P.; Liu, G.-R.; Lin, T.-H.; Young, C.-C. Retrieval of Atmospheric Thermodynamic State From Synergistic Use of Radio Occultation and Hyperspectral Infrared Radiances Observations. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2016, 9, 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-P.; Peng, L.; Mears, C.; Anthes, R.A. Comparison of global observations and trends of total precipitable water derived from microwave radiometers and COSMIC radio occultation from 2006 to 2013. Atmospheric Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.P.; Kuo, Y.H.; Sokolovskiy, S. Improvement of the temperature and moisture retrievals in the lower troposphere using AIRS and GPS radio occultation measurements. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2007, 24, 1726–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-P.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Schreiner, W.; Zhou, X. Using SI-traceable global positioning system radio occultation measurements for climate monitoring In "State of the Climate in 2009". Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2010, 91, S36–S37. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, S.P.; Yue, X.; Zeng, Z.; Ao, C.O.; Huang, C.Y.; Kursinski, E.R.; Kuo, Y.H. Applications of COSMIC radio occultation data from the troposphere to ionosphere and potential impacts of COSMIC-2 data. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2014, 95, ES18–ES22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-P.; Peng, L.; Anthes, R.A.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Lin, H.-C. Marine Boundary Layer Heights and Their Longitudinal, Diurnal, and Interseasonal Variability in the Southeastern Pacific Using COSMIC, CALIOP, and Radiosonde Data. J. Clim. 2015, 28, 2856–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-P.; Kirchengast, G.; Leroy, S.; Wickert, J.; Mannucci, A.J.; Steiner, A.; Hunt, D.; Schreiner, W.; Sokolovskiy, S.; Ao, C.; et al. Estimating the uncertainty of using GPS radio occultation data for climate monitoring: Intercomparison of CHAMP refractivity climate records from 2002 to 2006 from different data centers. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2009, 114, D23107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-P.; Hunt, D.; Steiner, A.; Mannucci, A.J.; Kirchengast, G.; Gleisner, H.; Heise, S.; Von Engeln, A.; Marquardt, C.; Sokolovskiy, S.; et al. Reproducibility of GPS radio occultation data for climate monitoring: Profile-to-profile inter-comparison of CHAMP climate records 2002 to 2008 from six data centers. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2012, 117, D18111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, A.K.; Ladstädter, F.; Ao, C.O.; Gleisner, H.; Ho, S.-P.; Hunt, D.; Schmidt, T.; Foelsche, U.; Kirchengast, G.; Kuo, Y.-H.; et al. Consistency and structural uncertainty of multi-mission GPS radio occultation records. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2020, 13, 2547–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-P.; Peng, L.; Vömel, H. Characterization of the long-term radiosonde temperature biases in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere using COSMIC and Metop-A/GRAS data from 2006 to 2014. Atmospheric Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 4493–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-P.; Peng, L. Global water vapor estimates from measurements from active GPS RO sensors and passive infrared and microwave sounders. In Green Chemistry Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Yang, S.C.; Ho, S.P.; Pedatella, N.M. Exploring the terrestrial and space weather using an operational radio occultation satellite constellation—A FORMOSAT-7/COSMIC-2 Special Issue after 1-year on orbit. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 2022, 32, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucurull, L; Derber; J. C.; Purser, R. J.; A bending angle forward operator for global positioning system radio occultation measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013; 118, 14–28. [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-P.; Pedatella, N.; Foelsche, U.; Healy, S.; Weiss, J.P.; Ullman, R. Using Radio Occultation Data for Atmospheric Numerical Weather Prediction, Climate Sciences, and Ionospheric Studies and Initial Results from COSMIC-2, Commercial RO Data, and Recent RO Missions. Bul. Amer. Meteor. Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-P.; Zhou, X.; Shao, X.; Zhang, B.; Adhikari, L.; Kireev, S.; He, Y.; Yoe, J.; Xia-Serafino, W.; Lynch, E. Initial Assessment of the COSMIC-2/FORMOSAT-7 Neutral Atmosphere Data Quality in NESDIS/STAR Using In Situ and Satellite Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shao, X.; Cao, C.-Y.; Ho, S.-P. Simultaneous Radio Occultation Predictions for Inter-Satellite Comparison of Bending Angle Profiles from COSMIC-2 and GeoOptics. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Ho, S.-P.; Cao, C.; Shao, X.; Dong, D. ; Chen. Y. Verification and Validation of the COSMIC-2 Excess Phase and Bending Angle Algorithms for Data Quality Assurance at STAR. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3288.

- Chen, Y.; Han, Y.; Weng, F. Characterization of Long-Term Stability of Suomi NPP Cross-Track Infrared Sounder Spectral Calibration. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 1147–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, L.; Ho, S.-P.; Zhou, X. Inverting COSMIC-2 Phase Data to Bending Angle and Refractivity Profiles Using the Full Spectrum Inversion Method. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cao, C.; Shao, X.; Ho, S.-P. Assessment of the Consistency and Stability of CrIS Infrared Observations Using COSMIC-2 Radio Occultation Data over Ocean. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-p.; Kireev, S.; Shao, X.; Zhou, X.; Jing, X. Processing and Validation of the STAR COSMIC-2 Temperature and Water Vapor Profiles in the Neural Atmosphere. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Shao, X.; Liu, T.-C.; Zhang, B. Comparison of GRUAN RS92 and RS41 Radiosonde Temperature Biases. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W. J. , Y. Chen, S.-P. Ho, and X. Shao, Evaluating the impacts of COSMIC-2 GNSS RO bending angle assimilation on Atlantic hurricane forecasts using the HWRF model. Mon. Wea. Rev., under review, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, X. , Shu-Peng Ho, Bin Zhang, Changyong Cao, and Yong Chen, Consistency and Stability of SNPP ATMS Microwave Observations and COSMIC-2 Radio Occultation over Oceans, Remote Sens. 2021a, 13, 3754. [CrossRef]

- Shao, X. S.-P. Ho, B. Zhang, X. Zhou, S. Kireev, Y. Chen, and C. Cao, 2021b: Comparison of COSMIC-2 radio occultation retrievals with RS41 and RS92 radiosonde humidity and temperature measurements. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci., 2021b, 32, 1015-1032. [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Wang, W.; Lynch, E.; Bai, Y.; Ho, S.-P.; Zhang, B. Simultaneous Radio Occultation for intersatellite comparison of bending angle toward more accurate atmospheric sounding. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2020, 37, 2307–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallas Masters, Seizing Opportunity: Spire’s CubeSat Constellation of GNSS, AIS, and ADS-B Sensors, Stanford PNT Symposium, 2018-11-08. http://web.stanford.edu/group/scpnt/pnt/PNT18/presentation_files/I07-Masters-Spire_GNSS_AIS_ADS-B.pdf.

- Andrea, K.S.; et al. Consistency and structural uncertainty of multi-mission GPS radio occultation records. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2020, 13, 2547–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucurull, L.; Derber, J. C.; and Purser, R. J. A bending angle forward operator for global positioning system radio occultation measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 118, 2013,14–28. [CrossRef]

- Kursinski, E. R.; Gebhardt, T. A method to deconvolve errors in GPS RO- derived water vapor histograms. J. Atmos. Oceanic Technol., 31, 2014, 2606–2628. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.-H.; Wee, T.-K.; Sokolovskiy, S.; Rocken, C.; Schreiner, W.; Hunt, D.; Anthes, R. A. Inversion and error estimation of GPS radio occultation data. J. Meteor. Soc. Japan, 82, 2004, 507–531. [CrossRef]

- Parrish, D. F.; Derber J., C. The National Meteorological Center’s Spectral Statistical-Interpolation Analysis System, Monthly Weather Review, 120, 1992, 1747-1763. [CrossRef]

- Culverwell, I.D.; Lewis, H.W.; Offiler, D.; Marquardt, C.; Burrows, C.P. The Radio Occultation Processing Package, ROPP. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2015, 8, 1887–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, W.; Rocken, C.; Sokolovskiy, S.; Hunt, D. Quality assessment of COSMIC/FORMOSAT-3 GPS radio occultation data derived from single- and double-difference atmospheric excess phase processing. GPS Solut. 2009, 14, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthes, R.; Sjoberg, J.; Feng, X. L.; and Syndergaard, S. Comparison of COSMIC and COSMIC-2 Radio Occultation Refractivity and Bending Angle Uncertainties in August 2006 and 2021, Atmosphere 2022, 13(5), 790. [CrossRef]

| 10oN-10oS | 30oN-10oN | 10oS-30oS | 45oN-30oN | 30oS-45oS | 60oN-45oN | 45oN-60oS | 90oN-60oN | 60oS-90oS | |

| COSMIC-2 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.75 | 1.35 | 1.10 | ||||

| Spire | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.25 | 0.45 | 0.20 |

| KOMPSAT-5 | 1.85 | 1.50 | 1.15 | 0.40 | 0.95 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.25 | 0.20 |

| PAZ | 2.65 | 1.85 | 2.05 | 0.90 | 1.30 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| Mean Difference | standard deviation | Sample Number at 10 km altitude | |

| Spire -PAZ | 0.01% | 3.25% | 113 |

| Spire -KOMSAT-5 | 0.18% | 3.20% | 54 |

| Spire -Metop-A GRAS | 0.12% | 1.94% | 816 |

| Spire - Metop-B GRAS | 0.06% | 2.89% | 792 |

| Spire -TerraSAR-X | -0.13% | 3.35% | 42 |

| Mean | standard deviation | Sample Number at 10 km altitude | |

| 0–500 V/V | 0.12% | 4.15% | 364 |

| 500–1000 V/V | 0.10% | 4.14% | 1727 |

| 1000–1500 V/V | 0.24% | 3.97% | 2559 |

| 1500–2000 V/V | 0.16% | 3.87% | 2325 |

| > 2000 V/V | 0.19% | 4.07% | 332 |

| Mean | standard deviation | |

| GPS | 0.06% | 0.73% |

| GLONASS | 0.06% | 0.78% |

| GALILEO | 0.06% | 0.69% |

| Spire Retrieval |

µ(ΔT) (σ(ΔT))(K) (8-11 km) |

µ(ΔT) (σ(ΔT)) (K) (12.5-16.5 km) |

µ(ΔT) (σ(ΔT)) (K) (17.8-26.4 km) |

µ(ΔH) (σ(ΔH)) (g/kg) (below 4.2 km) |

µ(ΔH) (σ(ΔH)) (g/kg) (4.8-8.4 km) |

| UCAR wetPf2 | 0.02(1.13) | -0.00(1.22) | -0.01(1.40) | -0.19(1.02) | -0.04(0.45) |

| Height Range | Day | Night | Dusk/Dawn |

| 8-11 km | 0.06(1.10) | -0.04(1.15) | -0.01(1.21) |

| 12.5-16.5 km | 0.01(1.20) | -0.02(1.25) | -0.02(1.25) |

| 17.8-26.4 km | 0.02(1.38) | -0.05(1.46) | -0.06(1.35) |

| Height Range | Day | Night | Dusk/Dawn |

| Below 4.2 km | -0.17(1.03) | -0.23(1.07) | -0.15(0.89) |

| 4.8-8.4 km | -0.04(0.45) | -0.06(0.49) | -0.02(0.39) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).