Submitted:

16 August 2023

Posted:

17 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

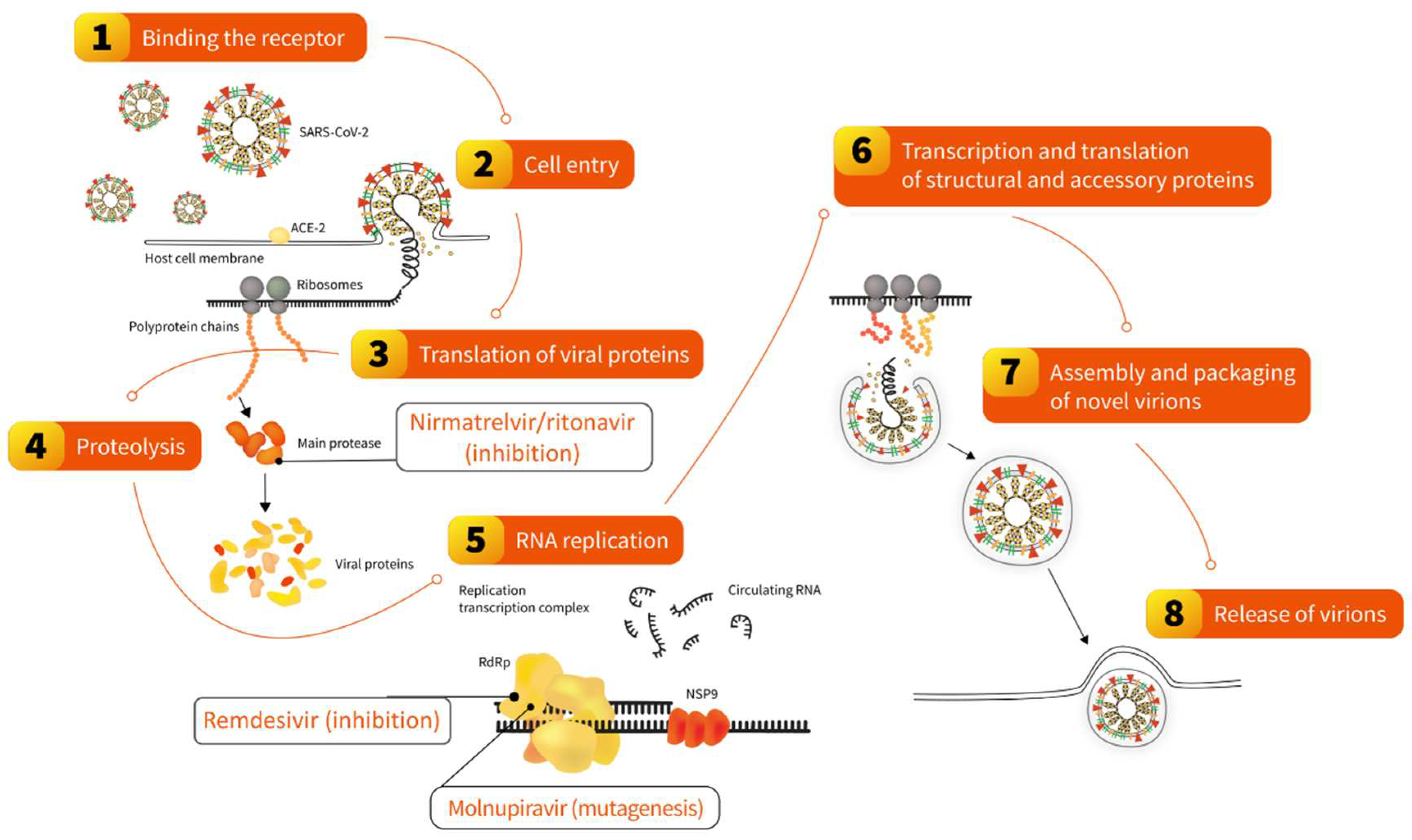

1. Introduction

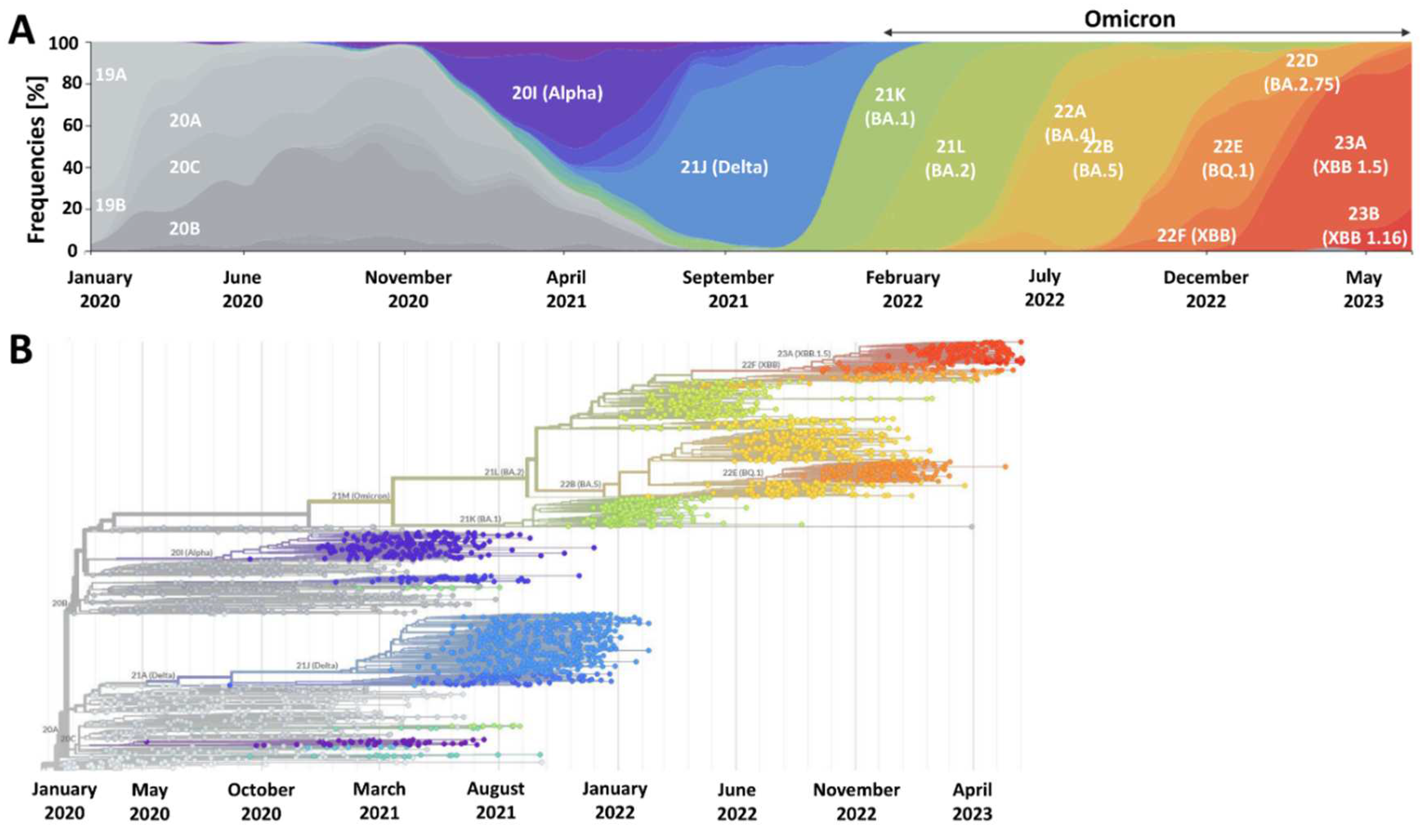

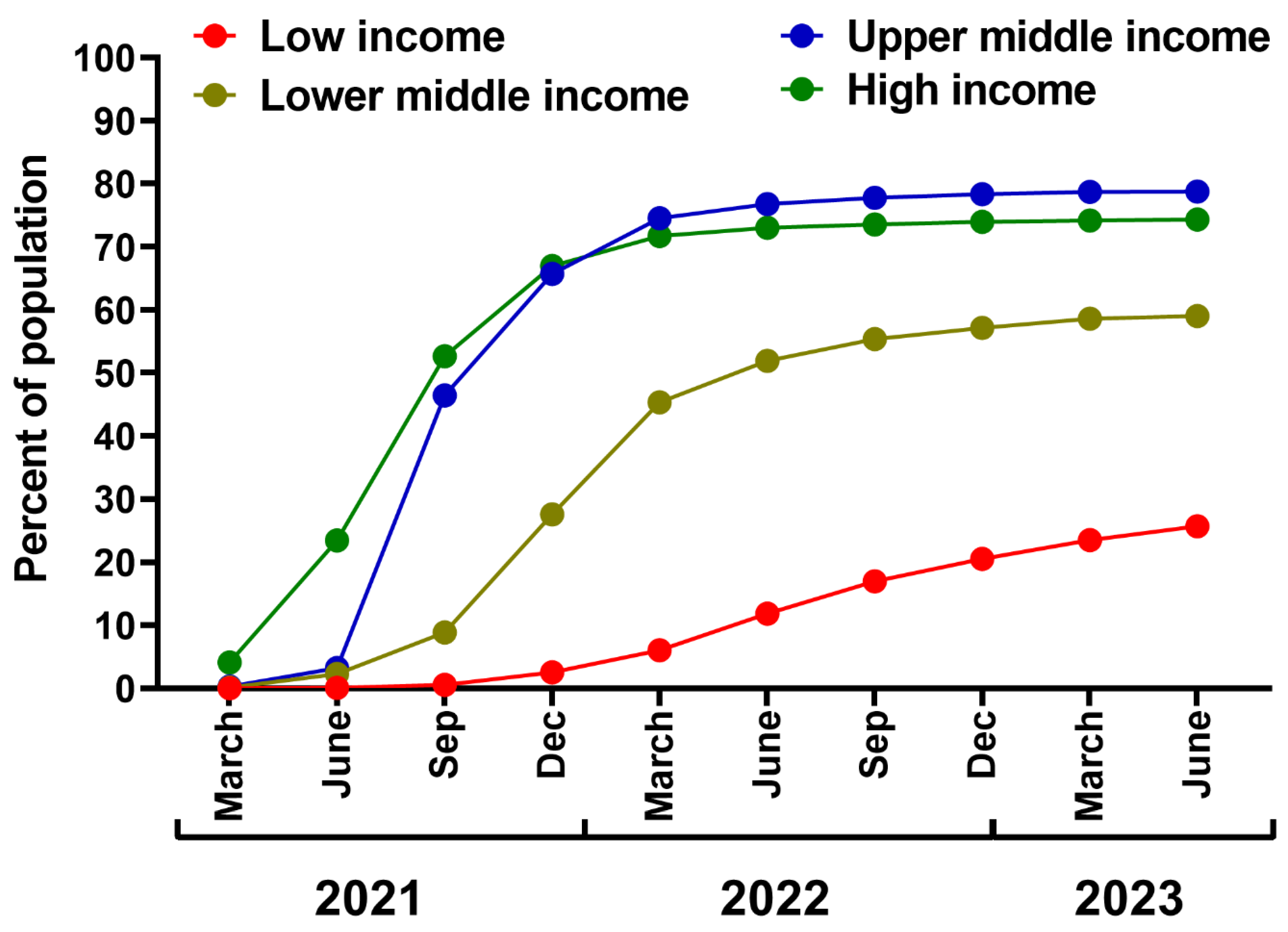

2. SARS-CoV-2 Is Here to Stay and Will Continue to Evolve

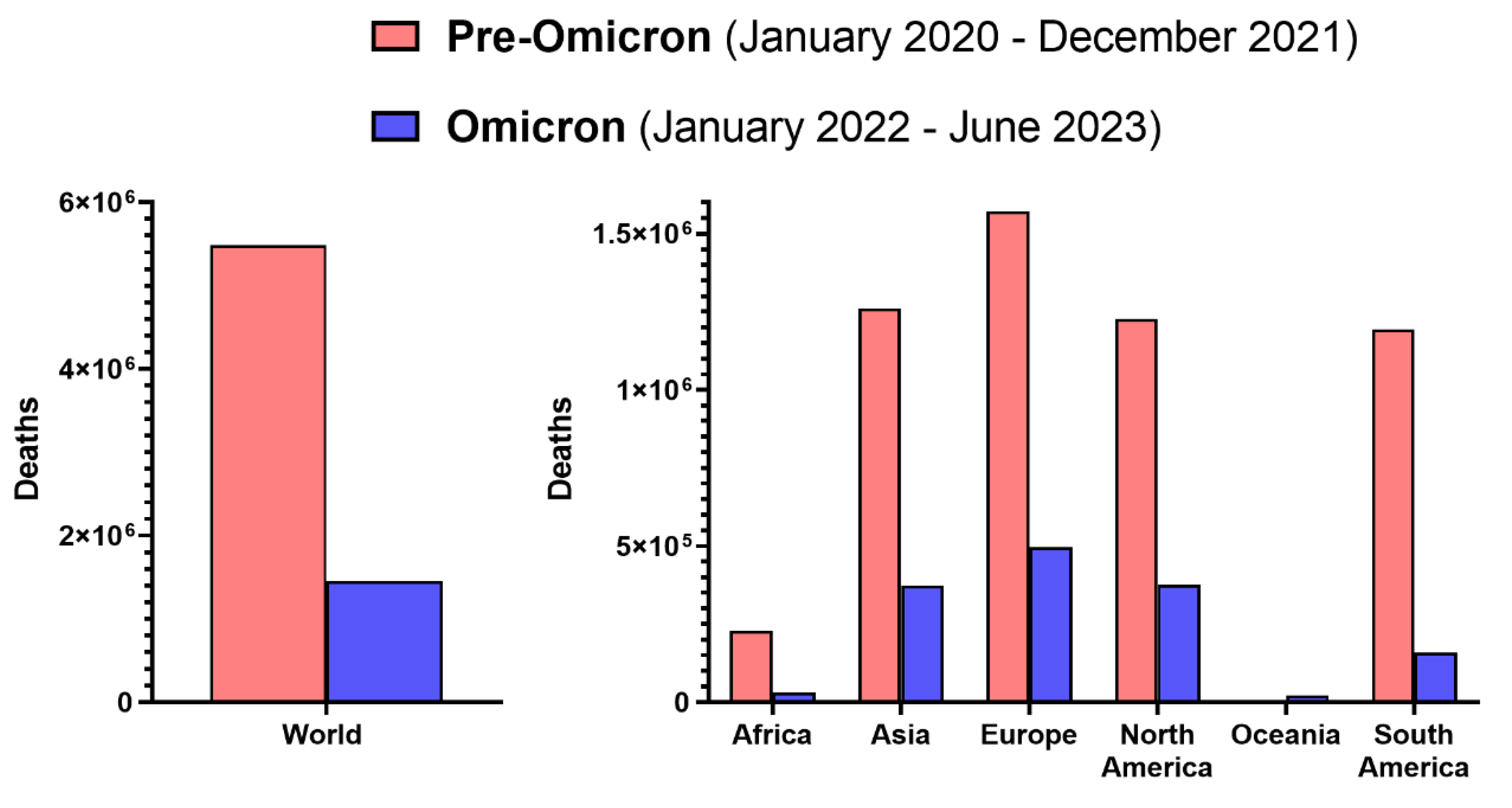

3. Omicron Lineage Is Milder But Not Negligible

4. Future Viral Variants May Not Necessarily Be Always Milder

5. Vaccines Remain a Key Component of Primary COVID-19 Prevention

6. Simplifying COVID-19 Booster Vaccination Will Improve Vaccine Acceptance and Intake

7. Antivirals Represent a Strategy to Adapt to Long-Term Co-existence with SARS-CoV-2

8. Leaving No Country Behind: Low-Income Regions Require Better Access to COVID-19 Vaccines and Antivirals

9. Healthcare Workers play a Crucial Role in Maintaining Public COVID-19 Awareness

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiang, S.; Xia, S.; Ying, T.; Lu, L. A novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) causing pneumonia-associated respiratory syndrome. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020, 17, 554–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohrabi, C.; Alsafi, Z.; O’Neill, N. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int J Surg. 2020, 76, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Statement on the fifteenth meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 pandemic. Published 2023. Accessed , 2023. https://www.who. 7 June 2023.

- Mathieu, E.; Ritchie, H.; Rodés-Guirao, L. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Our World in Data, /: Published online , 2020. Accessed December 14, 2022. https, 5 March 2020; 14. [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 Excess Mortality Collaborators. Estimating excess mortality due to the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic analysis of COVID-19-related mortality, 2020-21. Lancet. 2022, 399, 1513–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalbandian, A.; Sehgal, K.; Gupta, A. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021, 27, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Haupert, S.R.; Zimmermann, L.; Shi, X.; Fritsche, L.G.; Mukherjee, B. Global prevalence of post-Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) condition or long COVID: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J Infect Dis. 2022, 226, 1593–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Leon, S.; Wegman-Ostrosky, T.; Ayuzo Del Valle, N.C. Long-COVID in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 9950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzler, L.; Janssen, L.M.M.; Evers, S.M.A.A. The broader societal impacts of COVID-19 and the growing importance of capturing these in health economic analyses. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2021, 37, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, R. Effects of pandemic outbreak on economies: Evidence from business history context. Front Public Health. 2021, 9, 632043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, I.F.; Becker, A.D.; Grenfell, B.T.; Metcalf, C.J.E. Disease and healthcare burden of COVID-19 in the United States. Nat Med. 2020, 26, 1212–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen M, Li M, Malik A, et al. Global socio-economic losses and environmental gains from the Coronavirus pandemic. PLoS One. 2020, 15, e0235654. [Google Scholar]

- Sidor, A.; Rzymski, P. Dietary Choices and Habits during COVID-19 Lockdown: Experience from Poland. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onyeaka H, Anumudu CK, Al-Sharify ZT, Egele-Godswill E, Mbaegbu P. COVID-19 pandemic: A review of the global lockdown and its far-reaching effects. Sci Prog. 2021, 104, 368504211019854. [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowska J, Sobocińska J, Lewicki M, Lemańska Ż, Rzymski P. When science goes viral: The research response during three months of the COVID-19 outbreak. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020, 129, 110451. [Google Scholar]

- Ghebreyesus, T.A.; Swaminathan, S. Scientists are sprinting to outpace the novel coronavirus. Lancet. 2020, 395, 762–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusinato, J.; Cau, Y.; Calvani, A.M.; Mori, M. Repurposing drugs for the management of COVID-19. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2021, 31, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flisiak R, Zarębska-Michaluk D, Berkan-Kawińska A, et al. Remdesivir-based therapy improved the recovery of patients with COVID-19 in the multicenter, real-world SARSTer study. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2021, 131, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Zarębska-Michaluk D, Jaroszewicz J, Rogalska M, et al. Effectiveness of tocilizumab with and without dexamethasone in patients with severe COVID-19: A retrospective study. J Inflamm Res. 2021, 14, 3359–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flisiak, R.; Flisiak-Jackiewicz, M.; Rzymski, P.; Zarębska-Michaluk, D. Tocilizumab for the treatment of COVID-19. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther, 16 June 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniuszko-Malinowska A, Czupryna P, Zarębska-Michaluk D, et al. Convalescent plasma transfusion for the treatment of COVID-19-experience from Poland: A multicenter study. J Clin Med. 2020, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonovich VA, Burgos Pratx LD, Scibona P, et al. A randomized trial of convalescent plasma in Covid-19 severe pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021, 384, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Hillyer, C.; Du, L. Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and other human coronaviruses. Trends Immunol. 2020, 41, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 25. Brobst B, Borger J. Benefits and Risks of Administering Monoclonal Antibody Therapy for Coronavirus (COVID-19), 2023.

- 26. Rahmah L, Abarikwu SO, Arero AG, et al. Oral antiviral treatments for COVID-19: opportunities and challenges. Pharmacological Reports, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Thanh Le T, Andreadakis Z, Kumar A, et al. The COVID-19 vaccine development landscape. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 305–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzymski P, Borkowski L, Drąg M, et al. The strategies to support the COVID-19 vaccination with evidence-based communication and tackling misinformation. Vaccines (Basel). 2021, 9, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, O.J.; Barnsley, G.; Toor, J.; Hogan, A.B.; Winskill, P.; Ghani, A.C. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022, 22, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Shao, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, G.; Zhang, W. Real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines: a literature review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2022, 114, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 31. Rzymski P, Kasianchuk N, Sikora D, Poniedziałek B. COVID-19 vaccinations and rates of infections, hospitalizations, ICU admissions, and deaths in Europe during SARS-CoV-2 Omicron wave in the first quarter of 2022. J Med Virol, 6 September 2022. [CrossRef]

- Rzymski P, Camargo CA, Fal A, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Boosters: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Vaccines. 2021, 9, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 33. Woldemeskel BA, Garliss CC, Blankson JN. mRNA Vaccine-Elicited SARS-CoV-2-Specific T cells Persist at 6 Months and Recognize the Delta Variant. Clin Infect Dis, 25 October 2021. [CrossRef]

- Jordan SC, Shin BH, Gadsden TAM, et al. T cell immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern (Alpha and Delta) in infected and vaccinated individuals. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021, 18, 2554–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 35. Jergovic M, Coplen CP, Uhrlaub JL, et al. Resilient T cell responses to B.1.1.529 (Omicron) SARS-CoV-2 variant. bioRxiv, 2: , 2022, 16 January 2022. [CrossRef]

- Collier DA, Ferreira IATM, Kotagiri P, et al. Age-related immune response heterogeneity to SARS-CoV-2 vaccine BNT162b2. Nature. 2021, 596, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brosh-Nissimov T, Orenbuch-Harroch E, Chowers M, et al. BNT162b2 vaccine breakthrough: clinical characteristics of 152 fully vaccinated hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Israel. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021, 27, 1652–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallam, J.; Jones, T.; Alley, J.; Kohut, M.L. Exercise after influenza or COVID-19 vaccination increases serum antibody without an increase in side effects. Brain Behav Immun. 2022, 102, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzymski P, Pazgan-Simon M, Kamerys J, et al. Severe breakthrough COVID-19 cases during six months of delta variant (B.1.617.2) domination in Poland. Vaccines (Basel). 2022, 10, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO World malaria report 2022. Published 2023. https://apps.who. 1484.

- Markov PV, Ghafari M, Beer M, et al. The evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023, 21, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassburg, M.A. The global eradication of smallpox. Am J Infect Control. 1982, 10, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combe, M.; Sanjuán, R. Variation in RNA virus mutation rates across host cells. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1003855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amicone M, Borges V, Alves MJ, et al. Mutation rate of SARS-CoV-2 and emergence of mutators during experimental evolution. Evol Med Public Health. 2022, 10, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanares-Meza LD, Medina-Contreras O. SARS-CoV-2 and influenza: a comparative overview and treatment implications. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2020, 77, 262–273. [Google Scholar]

- Rawson JMO, Landman SR, Reilly CS, Mansky LM. HIV-1 and HIV-2 exhibit similar mutation frequencies and spectra in the absence of G-to-A hypermutation. Retrovirology. 2015, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura F, Takeda H, Ueda Y, et al. Mutational spectrum of hepatitis C virus in patients with chronic hepatitis C determined by single molecule real-time sequencing. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korber B, Fischer WM, Gnanakaran S, et al. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: Evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell. 2020, 182, 812–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson B, Boni MF, Bull MJ, et al. Generation and transmission of interlineage recombinants in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Cell. 2021, 184, 5179–5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, C.; Bhattacharya, M.; Chopra, H.; Islam, M.A.; Saikumar, G.; Dhama, K. The SARS-CoV-2 Omicron recombinant subvariants XBB, XBB.1, and XBB.1.5 are expanding rapidly with unique mutations, antibody evasion, and immune escape properties - an alarming global threat of a surge in COVID-19 cases again? Int J Surg. 2023, 109, 1041–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parums, D.V. Editorial: The XBB.1.5 ('Kraken’) subvariant of Omicron SARS-CoV-2 and its rapid global spread. Med Sci Monit. 2023, 29, e939580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Chen, J.; Wei, G.W. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 evolution revealing vaccine-resistant mutations in Europe and America. J Phys Chem Lett. 2021, 12, 11850–11857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadarangani, M.; Marchant, A.; Kollmann, T.R. Immunological mechanisms of vaccine-induced protection against COVID-19 in humans. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021, 21, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 54. Lasrado N, Collier ARY, Miller J, et al. Waning immunity against XBB.1.5 following bivalent mRNA boosters. bioRxivorg, 2: , 2023, 23 January 2023.

- 55. Muik A, Lui BG, Diao H, et al. Progressive loss of conserved spike protein neutralizing antibody sites in Omicron sublineages is balanced by preserved T-cell recognition epitopes. bioRxiv, 2: , 2022, 15 December 2022. [CrossRef]

- 56. Abbasian MH, Mahmanzar M, Rahimian K, et al. Global landscape of SARS-CoV-2 mutations and conserved regions. J Transl Med. [CrossRef]

- McCafferty S, Haque AKMA, Vandierendonck A, et al. A dual-antigen self-amplifying RNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine induces potent humoral and cellular immune responses and protects against SARS-CoV-2 variants through T cell-mediated immunity. Mol Ther. 2022, 30, 2968–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nextstrain. Genomic epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 with subsampling focused globally since pandemic start. Published 2023. Accessed , 2023. https://nextstrain. 14 June.

- Viana R, Moyo S, Amoako DG, et al. Rapid epidemic expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in southern Africa. Nature. 2022, 603, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora P, Zhang L, Rocha C, et al. Comparable neutralisation evasion of SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariants BA.1, BA.2, and BA.3. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022, 22, 766–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 61. Liu L, Iketani S, Guo Y, et al. Striking antibody evasion manifested by the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. Nature, 23 December 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hui KPY, Ho JCW, Cheung MC, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant replication in human bronchus and lung ex vivo. Nature. 2022, 603, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki R, Yamasoba D, Kimura I, et al. Attenuated fusogenicity and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Nature. 2022, 603, 700–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang XJ, Yao L, Zhang HY, et al. Neutralization sensitivity, fusogenicity, and infectivity of Omicron subvariants. Genome Med. 2022, 14, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfmann PJ, Iida S, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron virus causes attenuated disease in mice and hamsters. Nature. 2022, 603, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelnabi R, Foo CS, Zhang X, et al. The omicron (B.1.1.529) SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern does not readily infect Syrian hamsters. Antiviral Res. 2022, 198, 105253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahan K, Giffin V, Tostanoski LH, et al. Reduced pathogenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant in hamsters. Med (N Y). 2022, 3, 262–268. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, J.F.W.; Chu, H. Pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1.1 in hamsters. EBioMedicine. 2022, 80, 104035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu W, Wang J, Yang Y, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B.1.1.529) infection in rhesus macaques, hamsters, and BALB/c mice with severe lung histopathological damage. J Med Virol. 2023, 95, e28846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menni C, Valdes AM, Polidori L, et al. Symptom prevalence, duration, and risk of hospital admission in individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 during periods of omicron and delta variant dominance: a prospective observational study from the ZOE COVID Study. Lancet. 2022, 399, 1618–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flisiak R, Rzymski P, Zarębska-Michaluk D, et al. Variability in the clinical course of COVID-19 in a retrospective analysis of a large real-world database. Viruses. 2023, 15, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 72. Consolazio D, Murtas R, Tunesi S, et al. A comparison between Omicron and earlier COVID-19 variants’ disease severity in the Milan area, Italy. Front Epidemiol. [CrossRef]

- Nyberg T, Ferguson NM, Nash SG, et al. Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet. 2022, 399, 1303–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bager P, Wohlfahrt J, Bhatt S, et al. Risk of hospitalisation associated with infection with SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant versus delta variant in Denmark: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022, 22, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassat W, Abdool Karim SS, Ozougwu L, et al. Trends in cases, hospitalizations, and mortality related to the Omicron BA.4/BA.5 subvariants in South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2023, 76, 1468–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 76. Pung R, Kong XP, Cui L, et al. Severity of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron XBB subvariants in Singapore. medRxiv, 2: , 2023, 10 May 2023. [CrossRef]

- 77. Karyakarte RP, Das R, Rajmane MV, et al. Chasing SARS-CoV-2 XBB.1.16 recombinant lineage in India and the clinical profile of XBB.1.16 cases in Maharashtra, India. medRxiv, 2: , 2023, 26 April 2023. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Influenza. Published 2023. Accessed , 2023. https://www.who. 14 June.

- Portmann L, de Kraker MEA, Fröhlich G, et al. Hospital outcomes of community-acquired SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant infection compared with influenza infection in Switzerland. JAMA Netw Open. 2023, 6, e2255599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor CA, Whitaker M, Anglin O, et al. COVID-19-associated hospitalizations among adults during SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron variant predominance, by race/ethnicity and vaccination status - COVID-NET, 14 states, July 2021-January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022, 71, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonelli, M.; Pujol, J.C.; Spector, T.D.; Ourselin, S.; Steves, C.J. Risk of long COVID associated with delta versus omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2. Lancet. 2022, 399, 2263–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaweethai T, Jolley SE, Karlson EW, et al. Development of a definition of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA. 2023, 329, 1934–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Wan Po, A. Omicron variant as nature’s solution to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2022, 47, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 84. Pascall DJ, Vink E, Blacow R, et al. Directions of change in intrinsic case severity across successive SARS-CoV-2 variant waves have been inconsistent. J Infect, 1 June 2023. [CrossRef]

- Earnest R, Uddin R, Matluk N, et al. Comparative transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 variants Delta and Alpha in New England, USA. Cell Rep Med. 2022, 3, 100583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King KL, Wilson S, Napolitano JM, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern Alpha and Delta show increased viral load in saliva. PLoS One. 2022, 17, e0267750. [Google Scholar]

- Yuasa S, Nakajima J, Takatsuki Y, et al. Viral load of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron is not high despite its high infectivity. J Med Virol. 2022, 94, 5543–5546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitman, A.M.; Lieberman, J.A.; Hoffman, N.G.; Roychoudhury, P.; Mathias, P.C.; Greninger, A.L. The SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant does not have higher nasal viral loads compared to the delta variant in symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals. J Clin Microbiol. 2022, 60, e0013922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhach O, Adea K, Hulo N, et al. Infectious viral load in unvaccinated and vaccinated individuals infected with ancestral, Delta or Omicron SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med. 2022, 28, 1491–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu L, Zhou L, Mo M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron RBD shows weaker binding affinity than the currently dominant Delta variant to human ACE2. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng B, Abdullahi A, Ferreira IATM, et al. Altered TMPRSS2 usage by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron impacts infectivity and fusogenicity. Nature. 2022, 603, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He X, Lau EHY, Wu P, et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020, 26, 672–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fajnzylber J, Regan J, Coxen K, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load is associated with increased disease severity and mortality. Nat Commun. 2020, 11, 5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito A, Irie T, Suzuki R, et al. Enhanced fusogenicity and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Delta P681R mutation. Nature. 2022, 602, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura I, Yamasoba D, Tamura T, et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2 subvariants, including BA.4 and BA.5. Cell. 2022, 185, 3992–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia S, Wang L, Jiao F, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants exhibit distinct fusogenicity, but similar sensitivity, to pan-CoV fusion inhibitors. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2023, 12, 2178241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia S, Jiao F, Wang L, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron XBB subvariants exhibit enhanced fusogenicity and substantial immune evasion in elderly population, but high sensitivity to pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitors. J Med Virol. 2023, 95, e28641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan S, Ye ZW, Liang R, et al. Pathogenicity, transmissibility, and fitness of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron in Syrian hamsters. Science. 2022, 377, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter N, Jassat W, Walaza S, et al. Clinical severity of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 lineages compared to BA.1 and Delta in South Africa. Nat Commun. 2022, 13, 5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, C.; Kerr, S.; Sheikh, A. Severity of Omicron BA.5 variant and protective effect of vaccination: national cohort and matched analyses in Scotland. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2023, 28, 100638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuffreda L, Lorenzo-Salazar JM, García-Martínez de Artola D, et al. Reinfection rate and disease severity of the BA.5 Omicron SARS-CoV-2 lineage compared to previously circulating variants of concern in the Canary Islands (Spain). Emerg Microbes Infect. 2023, 12, 2202281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oude Munnink BB, Sikkema RS, Nieuwenhuijse DF, et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 on mink farms between humans and mink and back to humans. Science. 2021, 371, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann M, Zhang L, Krüger N, et al. SARS-CoV-2 mutations acquired in mink reduce antibody-mediated neutralization. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domańska-Blicharz K, Orłowska A, Smreczak M, et al. Mink SARS-CoV-2 infection in Poland - short communication. J Vet Res. 2021, 65, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 105. Palmer MV, Martins M, Falkenberg S, et al. Susceptibility of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) to SARS-CoV-2. J Virol. [CrossRef]

- Chandler JC, Bevins SN, Ellis JW, et al. SARS-CoV-2 exposure in wild white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021, 118, e2114828118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li L, Han P, Huang B, et al. Broader-species receptor binding and structural bases of Omicron SARS-CoV-2 to both mouse and palm-civet ACE2s. Cell Discov. 2022, 8, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, T. SARS-CoV-2 mutations among minks show reduced lethality and infectivity to humans. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0247626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaux, C.A.; Pinault, L.; Delerce, J.; Raoult, D.; Levasseur, A.; Frutos, R. Spread of mink SARS-CoV-2 variants in humans: A model of sarbecovirus interspecies evolution. Front Microbiol, 6: 12, 6755. [Google Scholar]

- Willgert K, Didelot X, Surendran-Nair M, et al. Transmission history of SARS-CoV-2 in humans and white-tailed deer. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 12094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchipudi SV, Surendran-Nair M, Ruden RM, et al. Multiple spillovers from humans and onward transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in white-tailed deer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022, 119, e2121644119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Cantor, J.; Simon, K.I.; Bento, A.I.; Wing, C.; Whaley, C.M. Vaccinations against COVID-19 May have averted up to 140,000 deaths in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021, 40, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayano T, Sasanami M, Kobayashi T, et al. Number of averted COVID-19 cases and deaths attributable to reduced risk in vaccinated individuals in Japan. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2022, 28, 100571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattiuzzi C, Henry BM, Lippi G. COVID-19 vaccination uptake strongly predicts averted deaths of older people across Europe. Biomed J. 2022, 45, 961–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikora D, Rzymski P. COVID-19 vaccination and rates of infections, hospitalizations, ICU admissions, and deaths in the European Economic Area during autumn 2021 wave of SARS-CoV-2. Vaccines (Basel). 2022, 10, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi S, Choe YJ, Lim DS, et al. Impact of national Covid-19 vaccination Campaign, South Korea. Vaccine. 2022, 40, 3670–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy CV, O’Mara O, van Leeuwen E, CMMID COVID-19 Working Group, Jit M, Sandmann F. The impact of COVID-19 vaccination in prisons in England and Wales: a metapopulation model. BMC Public Health. 2022, 22, 1003. [Google Scholar]

- Santos CVBD, Noronha TG de, Werneck GL, Struchiner CJ, Villela DAM. Estimated COVID-19 severe cases and deaths averted in the first year of the vaccination campaign in Brazil: A retrospective observational study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2023, 17, 100418. [Google Scholar]

- Haas EJ, McLaughlin JM, Khan F, et al. Infections, hospitalisations, and deaths averted via a nationwide vaccination campaign using the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in Israel: a retrospective surveillance study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022, 22, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 120. Sacco C, Mateo-Urdiales A, Petrone D, et al. Estimating averted COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, intensive care unit admissions and deaths by COVID-19 vaccination, Italy, January-September 2021. Euro Surveill, 20 September. [CrossRef]

- Brannock MD, Chew RF, Preiss AJ, et al. Long COVID risk and pre-COVID vaccination in an EHR-based cohort study from the RECOVER program. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.A.; Luginbuhl, R.D.; Parker, R. Reduced incidence of long-COVID symptoms related to administration of COVID-19 vaccines both before COVID-19 diagnosis and up to 12 weeks after. bioRxiv, 2: online , 2021, 18 November 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli M, Penfold RS, Merino J, et al. Risk factors and disease profile of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK users of the COVID Symptom Study app: a prospective, community-based, nested, case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022, 22, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 124. Senjam SS, Balhara YPS, Kumar P, et al. Assessment of Post COVID-19 Health Problems and its Determinants in North India: A descriptive cross section study. bioRxiv, 2: 2021, 7 October 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ayoubkhani D, Bosworth ML, King S, et al. Risk of long COVID in people infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 after 2 doses of a Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine: Community-based, matched cohort study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022, 9, ofac464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Aly, Z.; Bowe, B.; Xie, Y. Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2022, 28, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taquet, M.; Dercon, Q.; Harrison, P.J. Six-month sequelae of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection: A retrospective cohort study of 10,024 breakthrough infections. Brain Behav Immun. 2022, 103, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notarte KI, Catahay JA, Velasco JV, et al. Impact of COVID-19 vaccination on the risk of developing long-COVID and on existing long-COVID symptoms: A systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2022, 53, 101624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu X, Wei D, Xu W, et al. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant to antibody neutralization elicited by booster vaccination. Cell Discov. 2022, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu J, Collier ARY, Rowe M, et al. Neutralization of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron BA.1 and BA.2 variants. N Engl J Med. 2022, 386, 1579–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau JJ, Cheng SMS, Leung K, et al. Real-world COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against the Omicron BA.2 variant in a SARS-CoV-2 infection-naive population. Nat Med. 2023, 29, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed H, Pham-Tran DD, Yeoh ZYM, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against infection, symptomatic and severe COVID-19 disease caused by the Omicron variant (B.1.1.529). Vaccines (Basel). 2023, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarębska-Michaluk D, Hu C, Brzdęk M, Flisiak R, Rzymski P. COVID-19 vaccine booster strategies for Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: Effectiveness and future prospects. Vaccines (Basel). 2022, 10, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solante R, Alvarez-Moreno C, Burhan E, et al. Expert review of global real-world data on COVID-19 vaccine booster effectiveness and safety during the omicron-dominant phase of the pandemic. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2023, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu N, Joyal-Desmarais K, Ribeiro PAB, et al. Long-term effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against infections, hospitalisations, and mortality in adults: findings from a rapid living systematic evidence synthesis and meta-analysis up to December, 2022. Lancet Respir Med. 2023, 11, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liang, H.; Ding, X.; Cao, Y.; Yang, D.; Duan, Y. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccine in children and adolescents with the Omicron variant: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2023, 86, e64–e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 137. Mendes D, Chapman R, Aruffo E, et al. Public health impact of UK COVID-19 booster vaccination programs during Omicron predominance. Expert Rev Vaccines, 1: 2023, 3 January 2023.

- Link-Gelles R, Ciesla AA, Fleming-Dutra KE, et al. Effectiveness of bivalent mRNA vaccines in preventing symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection - Increasing Community Access to testing program, United States, September-November 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022, 71, 1526–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link-Gelles R, Ciesla AA, Roper LE, et al. Early estimates of bivalent mRNA booster dose vaccine effectiveness in preventing symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection attributable to Omicron BA.5- and XBB/XBB.1.5-related sublineages among immunocompetent adults - Increasing Community Access to testing program, United States, December 2022-January 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023, 72, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- 140. Arbel R, Peretz A, Sergienko R, et al. Effectiveness of a bivalent mRNA vaccine booster dose to prevent severe COVID-19 outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis, 13 April 2023. [CrossRef]

- Collier ARY, Miller J, Hachmann NP, et al. Immunogenicity of BA.5 bivalent mRNA vaccine boosters. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388, 565–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Offit, P.A. Bivalent covid-19 vaccines - A cautionary tale. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388, 481–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Q, Bowen A, Valdez R, et al. Antibody response to omicron BA.4-BA.5 bivalent booster. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388, 567–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 144. Carreño JM, Singh G, Simon V, Krammer F, PVI study group. Bivalent COVID-19 booster vaccines and the absence of BA.5-specific antibodies. Lancet Microbe, 1 May 2023. [CrossRef]

- WHO Statement on the antigen composition of COVID-19 vaccines. Published 2023. Accessed , 2023. https://www.who. 18 June 2023.

- Ballouz T, Menges D, Kaufmann M, et al. Post COVID-19 condition after Wildtype, Delta, and Omicron SARS-CoV-2 infection and prior vaccination: Pooled analysis of two population-based cohorts. PLoS One. 2023, 18, e0281429. [Google Scholar]

- 147. Rzymski P, Szuster-Ciesielska A, Dzieciątkowski T, Gwenzi W, Fal A. mRNA vaccines: The future of prevention of viral infections? J Med Virol, 10 February 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hajnik RL, Plante JA, Liang Y, et al. Dual spike and nucleocapsid mRNA vaccination confer protection against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron and Delta variants in preclinical models. Sci Transl Med. 2022, 14, eabq1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alu, A.; Chen, L.; Lei, H.; Wei, Y.; Tian, X.; Wei, X. Intranasal COVID-19 vaccines: From bench to bed. EBioMedicine. 2022, 76, 103841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramvikas, M.; Arumugam, M.; Chakrabarti, S.R.; Jaganathan, K.S. Nasal Vaccine Delivery. In: Micro and Nanotechnology in Vaccine Development. Elsevier; 2017:279-301.

- Sengupta A, Azharuddin M, Cardona ME, et al. Intranasal Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 immunization with lipid adjuvants provides systemic and mucosal immune response against SARS-CoV-2 S1 spike and nucleocapsid protein. Vaccines (Basel). 2022, 10, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim S, Soh SH, Im YB, et al. Induction of systemic immunity through nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) of mice intranasally immunized with Brucella abortus malate dehydrogenase-loaded chitosan nanoparticles. PLoS One. 2020, 15, e0228463. [Google Scholar]

- McLenon, J.; Rogers, M.A.M. The fear of needles: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2019, 75, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladoye, M.J. Intranasal vaccines: a panacea to vaccine hesitancy? Med Res J. 2022, 7, 274–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhama K, Dhawan M, Tiwari R, et al. COVID-19 intranasal vaccines: current progress, advantages, prospects, and challenges. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022, 18, 2045853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhavan M, Ritchie AJ, Aboagye J, et al. Tolerability and immunogenicity of an intranasally-administered adenovirus-vectored COVID-19 vaccine: An open-label partially-randomised ascending dose phase I trial. EBioMedicine. 2022, 85, 104298. [Google Scholar]

- van Doremalen N, Purushotham JN, Schulz JE, et al. Intranasal ChAdOx1 nCoV-19/AZD1222 vaccination reduces viral shedding after SARS-CoV-2 D614G challenge in preclinical models. Sci Transl Med. 2021, 13, eabh0755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndeupen, S.; Qin, Z.; Jacobsen, S.; Bouteau, A.; Estanbouli, H.; Igyártó, B.Z. The mRNA-LNP platform’s lipid nanoparticle component used in preclinical vaccine studies is highly inflammatory. iScience. 2021, 24, 103479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đaković Rode O, Bodulić K, Zember S, et al. Decline of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody levels 6 months after complete BNT162b2 vaccination in healthcare workers to levels observed following the first vaccine dose. Vaccines (Basel). 2022, 10, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinian S, de Assis R, Khalil G, et al. Analysis and comparison of SARS-CoV-2 variant antibodies and neutralizing activity for 6 months after a booster mRNA vaccine in a healthcare worker population. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1166261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.F.S.; Pinto, A.C.M.D.; de Oliveira F de, C.E.; Caetano, L.F.; Araújo FM de, C.; Fonseca, M.H.G. Antibody response 6 months after the booster dose of Pfizer in previous recipients of CoronaVac. J Med Virol. 2023, 95, e28169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, J.P.; Hassler, H.B.; Dornburg, A. Infection by SARS-CoV-2 with alternate frequencies of mRNA vaccine boosting. J Med Virol. 2023, 95, e28461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker. Published 2023. Accessed , 2022. https://vaccinetracker.ecdc.europa.eu/public/extensions/COVID-19/vaccine-tracker. 31 January.

- Fieselmann, J.; Annac, K.; Erdsiek, F.; Yilmaz-Aslan, Y.; Brzoska, P. What are the reasons for refusing a COVID-19 vaccine? A qualitative analysis of social media in Germany. BMC Public Health. 2022, 22, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzymski, P.; Poniedziałek, B.; Fal, A. Willingness to receive the booster COVID-19 vaccine dose in Poland. Vaccines (Basel). 2021, 9, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzymski P, Sikora D, Zeyland J, et al. Frequency and nuisance level of adverse events in individuals receiving homologous and heterologous COVID-19 booster vaccine. Vaccines (Basel). 2022, 10, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobierajski, T.; Rzymski, P.; Wanke-Rytt, M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on attitudes toward vaccination: Representative study of polish society. Vaccines (Basel). 2023, 11, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capurro, G.; Tustin, J.; Jardine, C.G.; Driedger, S.M. When good messages go wrong: Perspectives on COVID-19 vaccines and vaccine communication from generally vaccine accepting individuals in Canada. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022, 18, 2145822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, N.; Caetano-Anollés, G. Worldwide correlations support COVID-19 seasonal behavior and impact of global change. Evol Bioinform Online. 2023, 19, 11769343231169376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavenčiak T, Monrad JT, Leech G, et al. Seasonal variation in SARS-CoV-2 transmission in temperate climates: A Bayesian modelling study in 143 European regions. PLoS Comput Biol. 2022, 18, e1010435. [Google Scholar]

- Wiemken TL, Khan F, Puzniak L, et al. Seasonal trends in COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and mortality in the United States and Europe. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National emergency department visits for COVID-19, influenza, and respiratory syncytial virus. Published , 2023. Accessed June 14, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/ncird/surveillance/respiratory-illnesses/index. 17 January.

- Harris, E. FDA clears RSV vaccine for adults aged 60 years or older. JAMA. 2023, 329, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulfer EA, Geckin B, Taks EJM, et al. Timing and sequence of vaccination against COVID-19 and influenza (TACTIC): a single-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2023, 29, 100628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ECDC-EMA statement on updating COVID-19 vaccines composition for new SARS-CoV-2 virus variants. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Published , 2023. Accessed June 14, 2023. https://www.ecdc.europa. 7 June.

- Imai M, Ito M, Kiso M, et al. Efficacy of antiviral agents against omicron subvariants BQ.1.1 and XBB. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan EYF, Yan VKC, Mok AHY, et al. Effectiveness of molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir-ritonavir in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 : A target trial emulation study. Ann Intern Med. 2023, 176, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng C, Xie R, Han G, et al. Safety and efficacy of Paxlovid against omicron variants of Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients. Infect Dis Ther. 2023, 12, 649–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz KL, Wang J, Tadrous M, et al. Population-based evaluation of the effectiveness of nirmatrelvir-ritonavir for reducing hospital admissions and mortality from COVID-19. CMAJ. 2023, 195, E220–E226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Choi, T.; Al-Aly, Z. Association of treatment with nirmatrelvir and the risk of post-COVID-19 condition. JAMA Intern Med. 2023, 183, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran M, Kumar Arora M, Asdaq SMB, et al. Discovery, development, and patent trends on molnupiravir: A prospective oral treatment for COVID-19. Molecules. 2021, 26, 5795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 182. Agostini ML, Pruijssers AJ, Chappell JD, et al. Small-molecule antiviral β-d-N 4-hydroxycytidine inhibits a proofreading-intact Coronavirus with a high genetic barrier to resistance. J Virol. [CrossRef]

- Barnard DL, Hubbard VD, Burton J, et al. Inhibition of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARSCoV) by calpain inhibitors and beta-D-N4-hydroxycytidine. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2004, 15, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayk Bernal A, Gomes da Silva MM, Musungaie DB, et al. Molnupiravir for oral treatment of Covid-19 in nonhospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2022, 386, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 185. Arribas JR, Bhagani S, Lobo SM, et al. Randomized trial of molnupiravir or placebo in patients hospitalized with covid-19. NEJM Evid. [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.K.H.; Au, I.C.H.; Lau, K.T.K.; Lau, E.H.Y.; Cowling, B.J.; Leung, G.M. Real-world effectiveness of early molnupiravir or nirmatrelvir-ritonavir in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 without supplemental oxygen requirement on admission during Hong Kong’s omicron BA.2 wave: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022, 22, 1681–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flisiak R, Zarębska-Michaluk D, Rogalska M, et al. Real-world experience with molnupiravir during the period of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant dominance. Pharmacol Rep. 2022, 74, 1279–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Choi, T.; Al-Aly, Z. Molnupiravir and risk of post-acute sequelae of covid-19: cohort study. BMJ, e: 381, 0745. [Google Scholar]

- EMA Veklury. European Medicines Agency. Published , 2020. Accessed January 22, 2023. https://www.ema.europa. 23 June.

- Dobrowolska K, Zarębska-Michaluk D, Brzdęk M, et al. Retrospective analysis of the effectiveness of remdesivir in COVID-19 treatment during periods dominated by Delta and Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variants in clinical settings. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 191. Sandin R, Harrison C, Draica F, et al. Estimated impact of oral nirmatrelvir;Ritonavir on reductions in hospitalizations and associated costs within high-risk COVID-19 patients in the US. Research Square, 30 November 2022. [CrossRef]

- Savinkina, A.; Paltiel, A.D.; Ross, J.S.; Gonsalves, G. Population-level strategies for nirmatrelvir/ritonavir prescribing-A cost-effectiveness analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022, 9, ofac637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai AKC, Chan CY, Cheung AWL, et al. Association of Molnupiravir and Nirmatrelvir-Ritonavir with preventable mortality, hospital admissions and related avoidable healthcare system cost among high-risk patients with mild to moderate COVID-19. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2023, 30, 100602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 194. Marangoni D, Antonello RM, Coppi M, et al. Combination regimen of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir and molnupiravir for the treatment of persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection: A case report and a scoping review of the literature. Int J Infect Dis.

- Jeong JH, Chokkakula S, Min SC, et al. Combination therapy with nirmatrelvir and molnupiravir improves the survival of SARS-CoV-2 infected mice. Antiviral Res. 2022, 208, 105430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.A.; Cowen, L.E. Using combination therapy to thwart drug resistance. Future Microbiol. 2015, 10, 1719–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 197. Moreno S, Perno CF, Mallon PW, et al. Two-drug vs. three-drug combinations for HIV-1: Do we have enough data to make the switch? HIV Med.

- Sun, F.; Lin, Y.; Wang, X.; Gao, Y.; Ye, S. Paxlovid in patients who are immunocompromised and hospitalised with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022, 22, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helleberg M, Niemann CU, Moestrup KS, et al. Persistent COVID-19 in an immunocompromised patient temporarily responsive to two courses of remdesivir therapy. J Infect Dis. 2020, 222, 1103–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 200. Camprubí D, Gaya A, Marcos MA, et al. Persistent replication of SARS-CoV-2 in a severely immunocompromised patient treated with several courses of remdesivir. Int J Infect Dis.

- European Medicines Agency. Use of molnupiravir for the treatment of COVID-19. Published 2022. Accessed , 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/referral/lagevrio-also-known-molnupiravir-mk-4482-covid-19-article-53-procedure-assessment-report_en. 14 June.

- European Medicines Agency. Paxlovid. Assessment report. Published 2022. Accessed , 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/paxlovid-epar-public-assessment-report_en. 14 June.

- Stegemann, S.; Gosch, M.; Breitkreutz, J. Swallowing dysfunction and dysphagia is an unrecognized challenge for oral drug therapy. Int J Pharm. 2012, 430, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummler H, Stillhart C, Meilicke L, et al. Impact of tablet size and shape on the swallowability in older adults. Pharmaceutics. 2023, 15, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawal, Y. Africa’s low COVID-19 mortality rate: A paradox? Int J Infect Dis. 2021, 102, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osei, S.A.; Biney, R.P.; Anning, A.S.; Nortey, L.N.; Ghartey-Kwansah, G. Low incidence of COVID-19 case severity and mortality in Africa; Could malaria co-infection provide the missing link? BMC Infect Dis. 2022, 22, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth J, Mathie D, Scott F, et al. Peptide microarray IgM and IgG screening of pre-SARS-CoV-2 human serum samples from Zimbabwe for reactivity with peptides from all seven human coronaviruses: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Microbe. 2023, 4, e215–e227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diop, B.Z.; Ngom, M.; Pougué Biyong, C.; Pougué Biyong, J.N. The relatively young and rural population may limit the spread and severity of COVID-19 in Africa: a modelling study. BMJ Glob Health. 2020, 5, e002699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill CJ, Mwananyanda L, MacLeod WB, et al. What is the prevalence of COVID-19 detection by PCR among deceased individuals in Lusaka, Zambia? A postmortem surveillance study. BMJ Open. 2022, 12, e066763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin AT, Owusu-Boaitey N, Pugh S, et al. Assessing the burden of COVID-19 in developing countries: systematic review, meta-analysis and public policy implications. BMJ Glob Health. 2022, 7, e008477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunyenje CA, Chirwa GC, Mboma SM, et al. COVID-19 vaccine inequity in African low-income countries. Front Public Health. 2023, 11, 1087662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Member State Briefing. Update on Global COVID-19 vaccination. Accessed , 2023. https://apps.who.int/gb/COVID-19/pdf_files/2023/05_01/Item1. 18 June.

- US international COVID-19 vaccine donations tracker, K.F.F. Published , 2023. Accessed June 11, 2023. https://www.kff. 9 June.

- Hassan, F.; Yamey, G.; Abbasi, K. Profiteering from vaccine inequity: a crime against humanity? BMJ, n: 374, 2027. [Google Scholar]

- Rzymski, P.; Szuster-Ciesielska, A. The COVID-19 vaccination still matters: Omicron variant is a final wake-up call for the rich to help the poor. Vaccines (Basel). 2022, 10, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. COVAX Allocation. Published 2022. Accessed , 2022. https://www.who. 15 May.

- Savinkina A, Bilinski A, Fitzpatrick M, et al. Estimating deaths averted and cost per life saved by scaling up mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in low-income and lower-middle-income countries in the COVID-19 Omicron variant era: a modelling study. BMJ Open. 2022, 12, e061752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman SA, Costales C, Sahoo MK, et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralization resistance mutations in patient with HIV/AIDS, California, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021, 27, 2720–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cele S, Karim F, Lustig G, et al. SARS-CoV-2 prolonged infection during advanced HIV disease evolves extensive immune escape. Cell Host Microbe. 2022, 30, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Reiche, AS. SARS-CoV-2 in low-income countries: the need for sustained genomic surveillance. Lancet Glob Health. 2023, 11, e815–e816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 221. Le T, Sun C, Chang J, Zhang G, Yin X. MRNA vaccine development for emerging animal and zoonotic diseases. Viruses. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, R.P.; Dessie, Z.G.; Noreddin, A.; El Zowalaty, M.E. Systematic review of important viral diseases in Africa in light of the “One Health” concept. Pathogens. 2020, 9, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwenzi, W.; Skirmuntt, E.C.; Musvuugwa, T.; Teta, C.; Halabowski, D.; Rzymski, P. Grappling with (re)-emerging infectious zoonoses: Risk assessment, mitigation framework, and future directions. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 82, 103350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, G. Covid-19: “Grotesque inequity” that only a quarter of paxlovid courses go to poorer countries. BMJ, o: 379, 2795. [Google Scholar]

- 225. Price of COVID treatments from Pfizer, Merck, GSK align with patient benefits -report. Reuters, 3 February 2022; 26.

- Baker RE, Mahmud AS, Miller IF, et al. Infectious disease in an era of global change. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022, 20, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, M.S. Physicians as role models in society. West J Med. 1990, 152, 292. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt, J.A.; Rosenberg, M.A.; Zevallos, A.; Brown, J.R.; Mileski, M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Telemedicine Utilization Across Multiple Service Lines in the United States. Healthcare (Basel). [CrossRef]

- Bazan, D.; Nowicki, M.; Rzymski, P. Medical students as the volunteer workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: Polish experience. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 55, 102109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benfante, A.; Di Tella, M.; Romeo, A.; Castelli, L. Traumatic stress in healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: A review of the immediate impact. Front Psychol, 5: 11, 5699. [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg, E.; Goldsmith, J.V.; Chen, C.; Prince-Paul, M.; Johnson, R.R. Opportunities to improve COVID-19 provider communication resources: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2021, 104, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach KJ, Salas Reyes R, Pentz B, et al. News media coverage of COVID-19 public health and policy information. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2021, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fotiadis K, Dadouli K, Avakian I, et al. Factors associated with healthcare workers’ (HCWs) acceptance of COVID-19 vaccinations and indications of a role model towards population vaccinations from a cross-sectional survey in Greece, may 2021. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 10558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 234. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Evaluation Report for the Training Module “Communicating with Patients about COVID-19 Vaccination”: Greece, /: Regional Office for Europe; 2023. Accessed , 2023. https, 18 June 2023.

- Burson, R.C.; Buttenheim, A.M.; Armstrong, A.; Feemster, K.A. Community pharmacies as sites of adult vaccination: A systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016, 12, 3146–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobierajski, T.; Rzymski, P.; Wanke-Rytt, M. The influence of recommendation of medical and non-medical authorities on the decision to vaccinate against influenza from a social vaccinology perspective: Cross-sectional, representative study of polish society. Vaccines (Basel). 2023, 11, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paudyal V, Fialová D, Henman MC, et al. Pharmacists’ involvement in COVID-19 vaccination across Europe: a situational analysis of current practice and policy. Int J Clin Pharm. 2021, 43, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queeno, B.V. Evaluation of inpatient influenza and pneumococcal vaccination acceptance rates with pharmacist education. J Pharm Pract. 2017, 30, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullagura, G.R.; Waite, N.M.; Houle, S.K.D.; Violette, R.; Wong, W.W.L. Cost-utility analysis of offering a novel remunerated community pharmacist consultation service on influenza vaccination for seniors in Ontario, Canada. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2019, 59, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).