Submitted:

12 August 2023

Posted:

15 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Phase 1, Preparation

Stakeholder groups

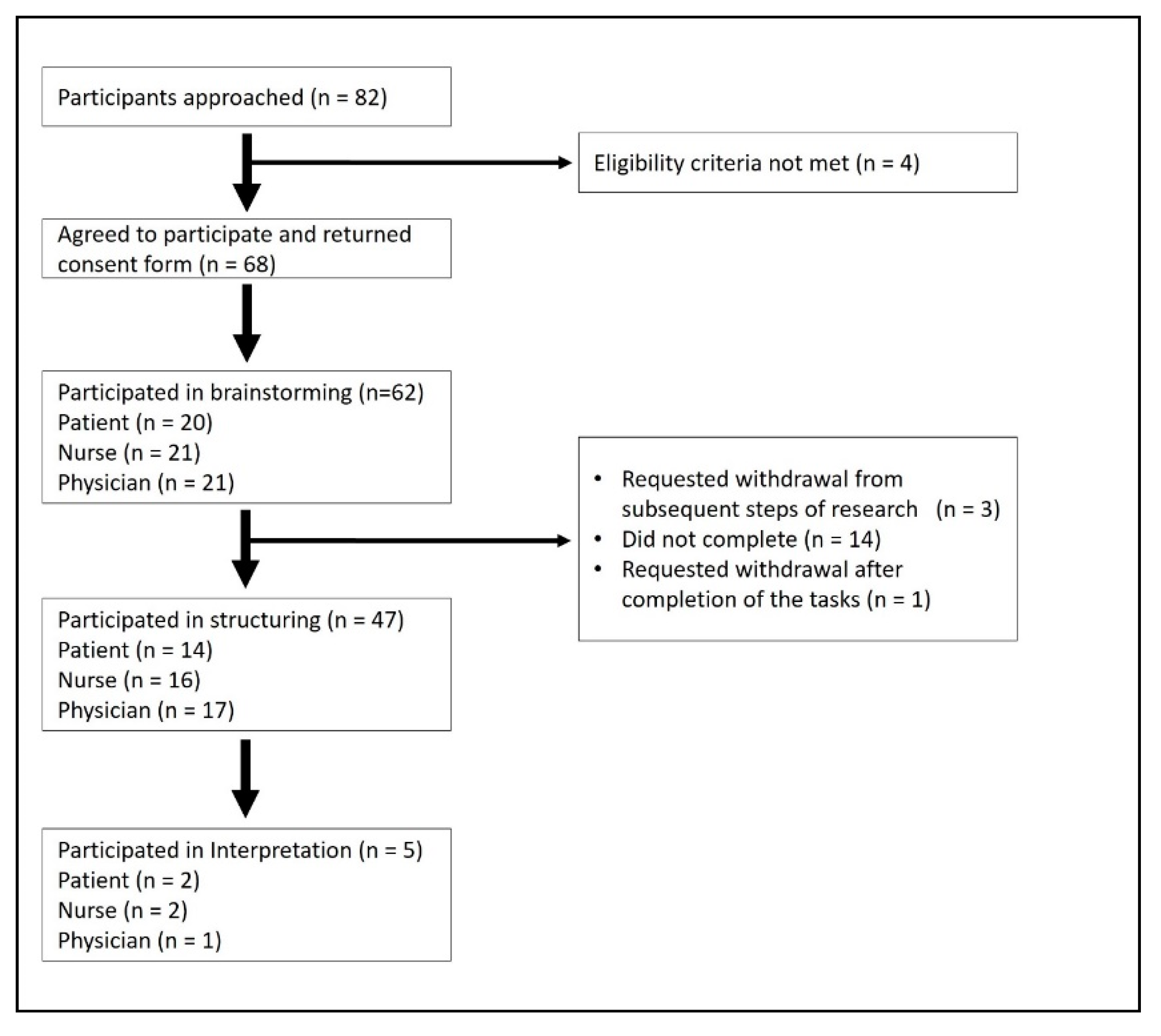

Recruitment and consent

Phase 2, Statement generation (Brainstorming)

Phase 3, Structuring of statements

Phase 4, Representation of the statements

Phase 5, Data Interpretation

Ethical Considerations

Results

Phase 2, Idea generation

Brainstorming

Statement reduction

Phase 3, Structuring of the statements

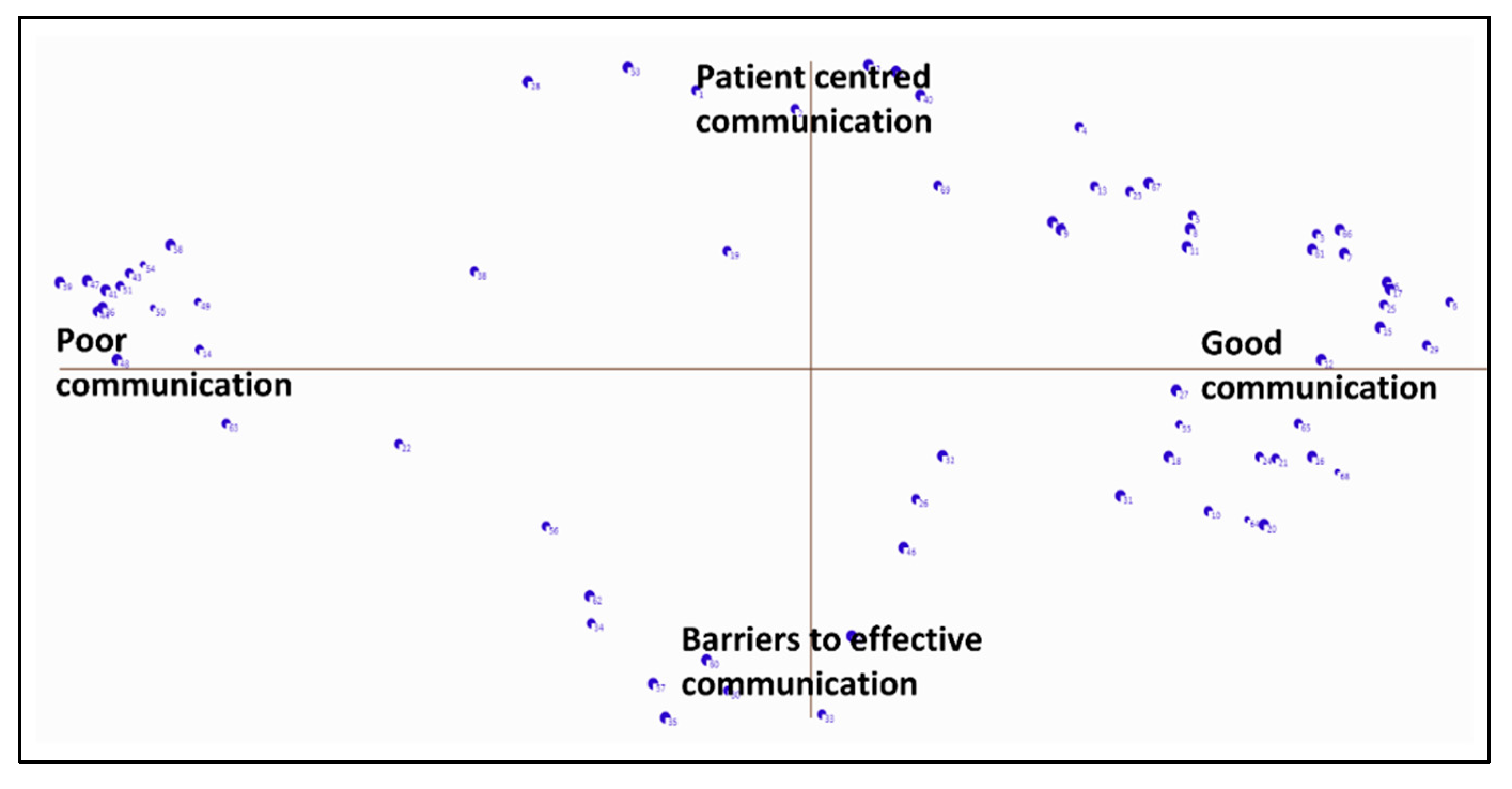

Phase 4, Representation of the statements

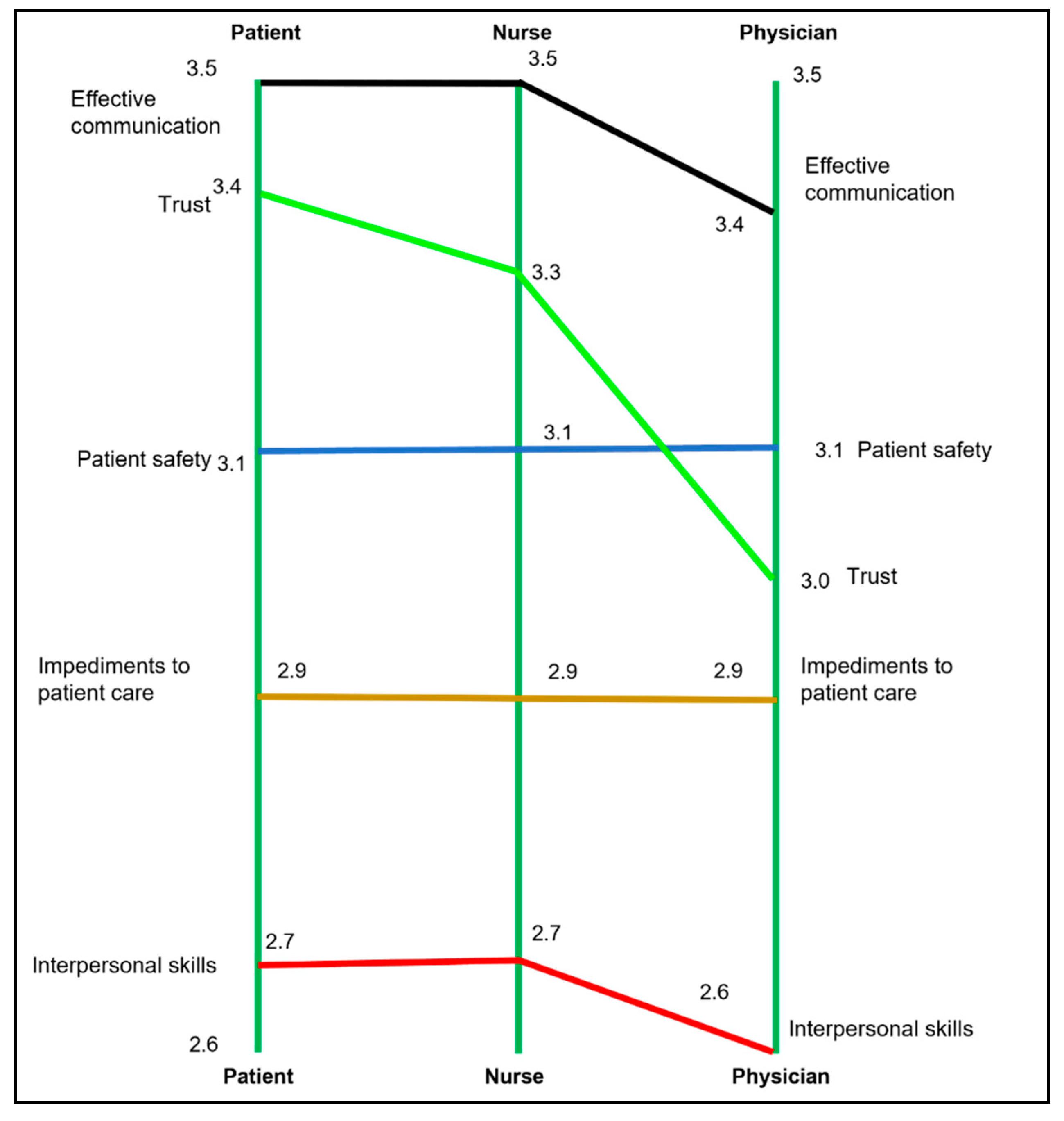

Phase 5, Data Interpretation

Description of the axis

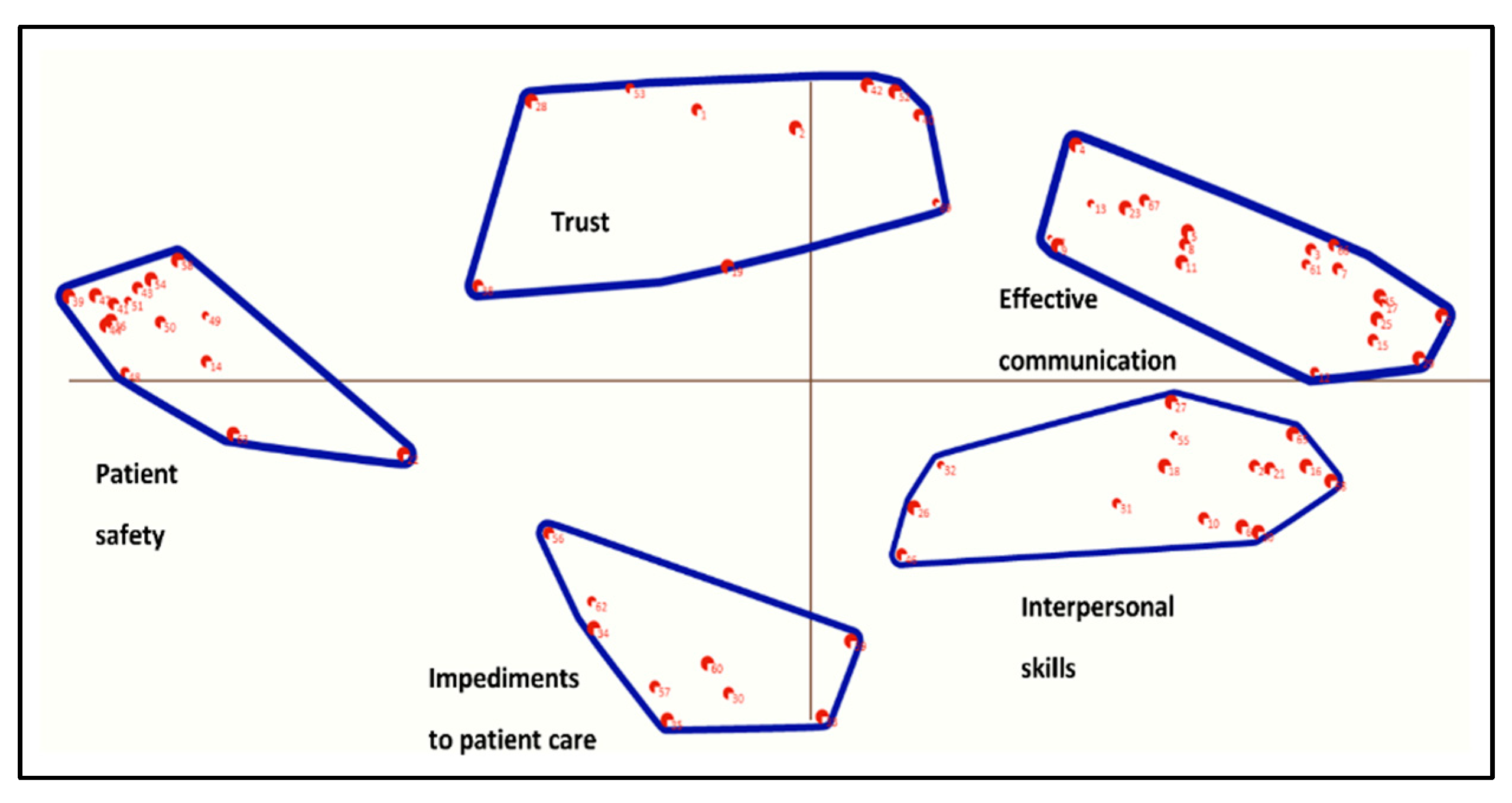

Description of the clusters

Cluster 1, Effective communication

Cluster 2, Trust

Cluster 3, Patient safety

Cluster 4, Impediments to patient care

Cluster 5, Interpersonal skills

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data availability statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Conflicts of interest

References

- Butler, R.; Monsalve, M.; Thomas, G.W.; Herman, T.; Segre, A.M.; Polgreen, P.M.; Suneja, M. Estimating Time Physicians and Other Health Care Workers Spend with Patients in an Intensive Care Unit Using a Sensor Network. The American Journal of Medicine 2018, 131, 972.e979–972.e915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-Y.; Wan, Q.-Q.; Lin, F.; Zhou, W.-J.; Shang, S.-M. Interventions to improve communication between nurses and physicians in the intensive care unit: An integrative literature review. International journal of nursing sciences 2018, 5, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Kim, J.H.; Despins, L. Time-motion study in an intensive care unit using the near field electromagnetic ranging system. In Proceedings of Proceedings of the 2017 industrial and systems engineering conference, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

- Wolff, J.; Auber, G.; Schober, T.; Schwär, F.; Hoffmann, K.; Metzger, M.; Heinzmann, A.; Krüger, M.; Normann, C.; Gitsch, G. , et al. Work time distribution of physicians at a German Hospital. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2017, 114, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, O.; Garcia Manjon, A.-J.; Pasquier, J.; Ortoleva Bucher, C. How do nurses spend their time? A time and motion analysis of nursing activities in an internal medicine unit. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2021, 77, 4459–4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, R.A.; Keohane, C.A. How Communication Among Members of the Health Care Team Affects Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2016, 45, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, O.; Coburn, N.G.; Nathens, A.B.; Hallet, J.; Ahmed, N.; Conn, L.G. Interprofessional communication between surgery trainees and nurses in the inpatient wards: Why time and space matter. J Interprof Care 2016, 30, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, L.L.; O’Brien, G.; O’Mahony, D.; Byrne, S. Interprofessional communication in the hospital setting: a systematic review of the qualitative literature. Journal of Interprofessional Care 2023, 37, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manojlovich, M.; DeCicco, B. Healthy Work Environments, Nurse-Physician Communication, and Patients’ Outcomes. American Journal of Critical Care 2007, 16, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; McHugh, M.D.; Aiken, L.H. Organization of hospital nursing and 30-day readmissions in Medicare patients undergoing surgery. Medical care 2015, 53, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Park, S.H.; Shang, J. Inter- and intra-disciplinary collaboration and patient safety outcomes in U.S. acute care hospital units: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2018, 85, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.L.; Brom, H.M.; Lasater, K.B.; McHugh, M.D. The association of nurse–physician teamwork and mortality in surgical patients. Western Journal of Nursing Research 2020, 42, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swiger, P.A.; Patrician, P.A.; Miltner, R.S.S.; Raju, D.; Breckenridge-Sproat, S.; Loan, L.A. The Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index: An updated review and recommendations for use. Int J Nurs Stud 2017, 74, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggs, J.G.; Ryan, S.A.; Phelps, C.E.; Richeson, J.F.; Johnson, J.E. The association between interdisciplinary collaboration and patient outcomes in a medical intensive care unit. Heart & lung: the journal of critical care 1992, 21, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Baggs, J.G.; Schmitt, M.H.; Mushlin, A.I.; Mitchell, P.H.; Eldredge, D.H.; Oakes, D.; Hutson, A.D. Association between nurse-physician collaboration and patient outcomes in three intensive care units. Critical care medicine 1999, 27, 1991–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, L.W. Nurses’ perceptions of collaborative nurse–physician transfer decision making as a predictor of patient outcomes in a medical intensive care unit. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1999, 29, 1434–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothberg, M.B.; Steele, J.R.; Wheeler, J.; Arora, A.; Priya, A.; Lindenauer, P.K. The Relationship Between Time Spent Communicating and Communication Outcomes on a Hospital Medicine Service. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2012, 27, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P. Trust and communication in a doctor-patient relationship: a literature review. Arch Med 2018, 3, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Trochim, W.; Kane, M. Concept mapping: An introduction to structured conceptualization in health care. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 2005, 17, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, S.R.; Kane, M. Quality and rigor of the concept mapping methodology: a pooled study analysis. Evaluation and program planning 2012, 35, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantha, S.; Jones, M.; Gray, R. Stakeholders’ perceptions of how nurse-physician communication may impact patient care: protocol for a concept mapping study. Journal of Interprofessional Care 2021, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardwell, R.; McKenna, L.; Davis, J.; Gray, R. How is clinical credibility defined in nursing? Protocol for a concept mapping study. J Clin Nurs 2019. [CrossRef]

- Severans, P. Manual Ariadne 3.0; 2015.

- Trochim, W.M.; McLinden, D. Introduction to a special issue on concept mapping. Evaluation and Program Planning 2017, 60, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdi, H.; Williams, L.J. Principal component analysis. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews: computational statistics 2010, 2, 433–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Payment of participants in research: Information for researchers, HRECs and other ethics review bodies; R41F; Australian Research Council and Universities Australia: Canberra, 2019; p 14.

- D’amour, D.; Ferrada-Videla, M.; San Martin Rodriguez, L.; Beaulieu, M.-D. The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: core concepts and theoretical frameworks. Journal of interprofessional care 2005, 19, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stutsky, B.J.; Laschinger, H.K.S. Development and Testing of a Conceptual Framework for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice. Health & Interprofessional Practice 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainbridge, L.; Nasmith, L.; Orchard, C.; Wood, V. Competencies for interprofessional collaboration. Journal of Physical Therapy Education 2010, 24, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bookey-Bassett, S.; Markle-Reid, M.; Mckey, C.A.; Akhtar-Danesh, N. Understanding interprofessional collaboration in the context of chronic disease management for older adults living in communities: a concept analysis. Journal of advanced nursing 2017, 73, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, L. Concept Analysis of Interdisciplinary Collaboration. Nursing Forum 2010, 45, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.C.; Zhou, H.; Kelly, M. Nurse-physician communication - An integrated review. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2017, 26, 3974–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, S.; Havens, D. Nurses’ and physicians’ perceptions of nurse-physician collaboration: a systematic review. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration 2017, 47, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cypress, B.S. Exploring the concept of nurse-physician communication within the context of health care outcomes using the evolutionary method of concept analysis. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing 2011, 30, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannick, S.; Davis, R.; Ashrafian, H.; Byrne, B.E.; Beveridge, I.; Athanasiou, T.; Wachter, R.M.; Sevdalis, N. Effects of Interdisciplinary Team Care Interventions on General Medical Wards: A Systematic Review. JAMA Intern Med 2015, 175, 1288–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, S.; Pelone, F.; Harrison, R.; Goldman, J.; Zwarenstein, M. Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Oh, S.K. Why People Don’t Use Facebook Anymore? An Investigation Into the Relationship Between the Big Five Personality Traits and the Motivation to Leave Facebook. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Participant groups | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Patient | Nurse | Doctor | ||||||

| Brainstorming | Clustering & prioritization | Brainstorming | Clustering & prioritization | Brainstorming | Clustering & prioritization | Brainstorming | Clustering & prioritization | ||

| (n=62) | (n = 47) | (n = 20) | (n = 13) | (n = 21) | (n = 16) | (n = 21) | (n = 18) | ||

| Gender (Female) | 47 (77%) | 38 (81%) | 14 (70%) | 10 (77 %) | 19 (90.5 %) | 14 (88%) | 14 (78%) | 14 (78%) | |

| Age in years (Mean, SD) | 35.9 (10.2) | 38.2 (12.3) | 45 (17) | 43.4 (14.7) | 41 (10.3) | 42.6 (11.1) | 30.3 (6.9) | 30.5 (7.1) | |

| Country of Birth | Australia | 34 (55%) | 28 (60 %) | 11 (55%) | 8 (62%) | 10 (48%) | 9 (56%) | 13 (62%) | 11 (62%) |

| Other | 28 (45%) | 19 (40 %) | 9 (45%) | 5 (38%) | 11 (52%) | 7 (44%) | 9 (38%) | 7 (38%) | |

| Highest educational qualification1 | Undergraduate | 2 (3%) | 2 (4%) | 2 (10%) | 2 (15%) | - | - | - | - |

| Graduate | 19 (31%) | 14 (30%) | 5 (25%) | 2 (15%) | 4 (19%) | 3 (19%) | 10 (48%) | 9 (50%) | |

| Postgraduate | 39 (63%) | 29 (62%) | 13 (65%) | 9 (70%) | 16 (76%) | 12 (75%) | 10 (48%) | 8 (44%) | |

| Country of clinical qualification | Australia | 32 (76%) | 27 (80%) | - | - | 15 (71%) | 12 (75%) | 17 (81%) | 15 (83%) |

| Other | 10 (24%) | 7 (20%) | - | - | 6 (29%) | 4 (25%) | 4 (19%) | 3 (17%) | |

| Years of clinical work (Mean, SD)2 | 9.3 (9.3) | 9.3 (9.9) | - | - | 13.5 (10.4) | 14.6 (11.2) | 4.8 (5.2) | 4.2 (4.6) | |

| Years at current workplace (Mean, SD)2 | 4.1 (5.2) | 4.3 (5.4) | - | - | 6.3 (6.3) | 7 (6.7) | 2 (1.7) | 1.8 (1.6) | |

| Clinical setting | Medical ward | - | - | 7 (35%) | 4 (30%) | - | - | - | - |

| Surgical ward | - | - | 12 (60%) | 8 (62%) | - | - | - | - | |

| Do not know | - | - | 1 (5%) | 1 (8%) | - | - | - | - | |

| Number1 | Statement | All stakeholders | Patient | Nurse | Doctor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean, SD | 95% CI | Mean, SD | 95% CI | Mean, SD | 95% CI | Mean, SD | 95% CI | ||

| Cluster 1, Effective communication | 3.4 (1.3) | 3.1,3.8 | 3.5 (1.2) | 2.8,4.2 | 3.5 (1.3) | 2.9,4.2 | 3.4 (1.2) | 2.8,3.9 | |

| 23 | Precise communication is required in emergency situations (e.g., cardiac arrest) | 4.6 (1.1) | 4.3,4.9 | 4.9 (0.4) | 4.7,5.1 | 4.2 (1.5) | 3.5,5.0 | 4.7 (0.9) | 4.3,5.1 |

| 61 | Clear and detailed clinical documentation is an important aspect of nurse-doctor communication | 4.2 (1.0) | 4.0,4.5 | 3.7 (1.3) | 3.0,4.5 | 4.5 (0.8) | 4.1,4.9 | 4.3 (0.9) | 3.9,4.7 |

| 4 | Effective nurse-doctor communication improves the quality of patient care | 4.1 (1.2) | 3.7,4.4 | 3.8 (1.4) | 3.0,4.6 | 4.1 (1.4) | 3.4,4.8 | 4.2 (1.0) | 3.7,4.7 |

| 13 | Effective nurse-doctor communication ensures timely patient care | 3.9 (1.2) | 3.6,4.3 | 4.1 (0.9) | 3.6,4.7 | 3.9 (1.0) | 3.4,4.4 | 3.8 (1.4) | 3.1,4.5 |

| 17 | Good communication is important across all shifts (including nights) | 3.9 (1.2) | 3.5,4.2 | 3.7 (1.3) | 3.0,4.5 | 3.7 (1.3) | 3.0,4.3 | 4.1 (1.1) | 3.6,4.6 |

| 8 | Nurses need ensure they are aware of change in patients care plans | 3.9 (1.1) | 3.7,4.2 | 4.0 (1.1) | 3.4,4.6 | 4.5 (0.6) | 4.2,4.8 | 3.4 (1.1) | 2.9,4.0 |

| 66 | Nurses and doctors need to have a good understand of current evidence-based practice guidelines | 3.7 (1.3) | 3.3,4.1 | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.1,4.4 | 3.8 (1.5) | 3.0,4.6 | 3.5 (1.3) | 2.9,4.2 |

| 3 | Nurses and doctors need to provide multidisciplinary patient care | 3.6 (1.4) | 3.2,4.0 | 3.4 (1.5) | 2.5,4.3 | 3.9 (1.2) | 3.3,4.5 | 3.4 (1.6) | 2.7,4.2 |

| 7 | Advice from nurses help doctors to plan patient care | 3.6 (1.2) | 3.2,3.9 | 3.3 (1.4) | 2.5,4.1 | 3.8 (1.1) | 3.2,4.4 | 3.5 (1.0) | 3.1,4.0 |

| 15 | Doctors need to make sure that the instructions they give to nurses is understood | 3.6 (1.1) | 3.4,3.9 | 3.9 (0.9) | 3.4,4.4 | 3.4 (1.3) | 2.8,4.1 | 3.7 (1.1) | 3.2,4.2 |

| 6 | Nurses and doctors need to trust each other’s capabilities | 3.5 (1.2) | 3.1,3.8 | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.0,4.5 | 3.4 (1.4) | 2.7,4.1 | 3.3 (1.1) | 2.8,3.8 |

| 29 | A structured handover between nurses and doctors is important | 3.4 (1.3) | 3.0,3.8 | 3.7 (1.0) | 3.1,4.3 | 3.1 (1.5) | 2.4,3.9 | 3.4 (1.3) | 2.8,4.1 |

| 11 | Nurses are a bridge between patient and the doctor | 3.3 (1.5) | 2.9,3.7 | 3.2 (1.6) | 2.3,4.1 | 3.9 (1.5) | 3.2,4.7 | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.2,3.5 |

| 37 | Nurses and doctors need to make sure that they do not discuss patient care where they can be overheard | 3.2 (1.4) | 2.8,3.6 | 3.0 (1.4) | 2.1,3.8 | 3.4 (1.5) | 2.6,4.2 | 3.0 (1.4) | 2.4,3.7 |

| 67 | Nurses need prioritise care that impacts patient recovery | 3.2 (1.3) | 2.9,3.6 | 3.4 (1.4) | 2.5,4.2 | 3.2 (1.3) | 2.5,3.8 | 3.2 (1.4) | 2.5,3.9 |

| 5 | Good nurse-doctor communication reminds clinicians what tasks need to be completed | 3.1 (1.4) | 2.7,3.5 | 2.6 (1.5) | 1.7,3.5 | 3.4 (1.1) | 2.8,3.9 | 3.2 (1.5) | 2.4,3.9 |

| 25 | Nurses and doctors should discuss care plan before seeing the patient | 3.0 (1.4) | 2.6,3.4 | 4.0 (0.9) | 3.5,4.5 | 3.3 (1.3) | 2.6,4.0 | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.4,2.5 |

| 45 | Clear allocation of tasks to nurses and doctors | 3.0 (1.1) | 2.7,3.3 | 3.1 (1.2) | 2.4,3.8 | 2.7 (1.0) | 2.2,3.2 | 3.2 (1.2) | 2.6,3.7 |

| 9 | Clinical problems can only be addressed through positive nurse-doctor communication | 2.9 (1.4) | 2.6,3.3 | 3.0 (1.4) | 2.2,3.8 | 3.1 (1.6) | 2.3,4.0 | 2.8 (1.2) | 2.2,3.4 |

| 12 | Communication is enhanced if nurses and doctors have consistent shifts (working hours) | 2.2 (1.3) | 1.8,2.6 | 2.4 (1.5) | 1.6,3.3 | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.2,2.4 | 2.4 (1.4) | 1.7,3.1 |

| Cluster 2, Trust | 3.2 (1.3) | 2.9,3.6 | 3.4 (1.2) | 2.7,4.1 | 3.3 (1.2) | 2.7,4.0 | 3.0 (1.2) | 2.6,3.6 | |

| 2 | Nurses and doctors need to be good at communicating with family members | 3.9 (1.1) | 3.6,4.2 | 4.2 (1.0) | 3.6,4.8 | 4.0 (1.2) | 3.4,4.6 | 3.5 (1.0) | 3.0,4.0 |

| 42 | Doctors and nurses need to be honest with patients | 3.9 (1.1) | 3.6,4.2 | 4.0 (1.3) | 3.3,4.8 | 3.5 (1.1) | 3.0,4.1 | 4.0 (1.0) | 3.5,4.5 |

| 28 | Patients need to fully understand their care and treatment | 3.6 (1.4) | 3.2,4.0 | 4.4 (0.8) | 3.9,4.8 | 3.7 (1.5) | 2.9,4.5 | 2.9 (1.4) | 2.2,3.6 |

| 52 | Good interdisciplinary communication will ensure that discharge plans are meaningful | 3.6 (1.2) | 3.3,3.9 | 2.9 (1.3) | 2.2,3.6 | 3.9 (1.1) | 3.3,4.5 | 3.7 (0.9) | 3.3,4.1 |

| 40 | Doctors and nurses need to use language that can be understood by the patient | 3.5 (1.4) | 3.1,3.9 | 4.1 (1.2) | 3.5,4.8 | 3.7 (1.4) | 2.9,4.4 | 3.0 (1.5) | 2.3,3.7 |

| 53 | Good communication between doctors and nurses can comfort patients | 3.3 (1.5) | 2.9,3.7 | 3.8 (1.4) | 3.0,4.6 | 3.4 (1.5) | 2.6,4.1 | 2.9 (1.4) | 2.2,3.6 |

| 19 | Direct (face-to-face) communication reduce delays in patient care | 3.2 (1.4) | 2.8,3.6 | 3.2 (1.4) | 2.4,4.0 | 3.0 (1.2) | 2.4,3.7 | 3.4 (1.7) | 2.6,4.2 |

| 1 | Good communication will improve people’s faith in medicine | 3.0 (1.3) | 2.7,3.4 | 3.1 (1.2) | 2.4,3.8 | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.1,3.5 | 3.1 (1.3) | 2.5,3.7 |

| 69 | Patients tend to share more information with nurses than doctors | 2.6 (1.4) | 2.2,3.0 | 2.2 (1.3) | 1.5,2.9 | 3.3 (1.6) | 2.5,4.1 | 2.2 (1.2) | 1.6,2.8 |

| 38 | Patients can influence communication between nurses and doctors | 2.0 (0.9) | 1.8,2.3 | 2.1 (1.2) | 1.5,2.8 | 2.0 (0.8) | 1.6,2.4 | 2.0 (0.9) | 1.6,2.5 |

| Cluster 3, Patient safety | 3.1 (1.3) | 2.8,3.5 | 3.1 (1.3) | 2.3,3.9 | 3.1 (1.3) | 2.4,3.9 | 3.1 (1.2) | 2.5,3.7 | |

| 49 | When vital information is not communicated, it can lead to an increased risk of mortality | 4.2 (1.1) | 3.9,4.5 | 4.0 (1.1) | 3.4,4.7 | 3.9 (1.3) | 3.2,4.5 | 4.6 (0.8) | 4.3,5.0 |

| 14 | Important information about patient care gets lost if communication is poor | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.3,4.0 | 3.2 (1.5) | 2.4,4.1 | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.1,4.4 | 3.9 (1.0) | 3.5,4.4 |

| 44 | Poor communication can lead to worse health care outcomes in the longer term | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.4,4.1 | 3.2 (1.3) | 2.4,4.0 | 3.6 (1.1) | 3.0,4.2 | 4.2 (1.1) | 3.6,4.7 |

| 43 | Bad communication between nurses and doctors may be traumatic for the patient | 3.4 (1.3) | 3.1,3.8 | 3.5 (1.3) | 2.8,4.3 | 3.5 (1.3) | 2.9,4.2 | 3.3 (1.3) | 2.6,3.9 |

| 48 | Patients can get wrong treatment | 3.2 (1.5) | 2.8,3.7 | 3.5 (1.5) | 2.6,4.4 | 3.2 (1.6) | 2.4,4.0 | 3.1 (1.6) | 2.4,3.9 |

| 41 | Poor communication may prolong a patient’s period of hospitalisation | 3.2 (1.4) | 2.8,3.5 | 3.3 (1.3) | 2.5,4.0 | 3.2 (1.4) | 2.5,4.0 | 3.0 (1.4) | 2.3,3.7 |

| 63 | Delayed communication can lead to frustration | 3.1 (1.3) | 2.8,3.5 | 3.4 (1.4) | 2.6,4.2 | 3.2 (1.5) | 2.4,4.0 | 2.9 (1.2) | 2.3,3.5 |

| 36 | Poor communication may mean that patients are sent to an inappropriate clinical setting | 3.1 (1.2) | 2.8,3.4 | 3.0 (1.1) | 2.4,3.7 | 3.0 (1.4) | 2.3,3.8 | 3.2 (1.2) | 2.6,3.7 |

| 47 | Poor communication may increase the chances of a patient needed to be readmitted | 3.0 (1.4) | 2.7,3.4 | 3.1 (1.5) | 2.3,4.0 | 2.9 (1.3) | 2.2,3.6 | 3.2 (1.4) | 2.5,3.8 |

| 39 | Poor communication may mean that patients are not clear about the self-care behaviours they need to change | 2.9 (1.4) | 2.5,3.2 | 3.2 (1.1) | 2.6,3.9 | 3.0 (1.6) | 2.2,3.8 | 2.5 (1.3) | 1.9,3.1 |

| 51 | Poor communication may mean that patients do not get the required interdepartmental consultation on time | 2.9 (1.3) | 2.5,3.3 | 2.6 (1.4) | 1.8,3.4 | 3.4 (1.2) | 2.8,4.0 | 2.7 (1.4) | 2.1,3.4 |

| 54 | Dissatisfied patients will disengage with healthcare services | 2.8 (1.5) | 2.4,3.2 | 2.8 (1.6) | 1.9,3.8 | 2.9 (1.5) | 2.1,3.7 | 2.7 (1.4) | 2.1,3.4 |

| 22 | The severity of a patient’s condition can impact communication | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.3,3.0 | 2.3 (1.1) | 1.7,2.9 | 2.6 (1.4) | 1.9,3.3 | 3.0 (1.2) | 2.5,3.6 |

| 50 | Patients can be discharged before they are ready | 2.5 (1.3) | 2.1,2.9 | 2.5 (1.3) | 1.8,3.3 | 2.5 (1.4) | 1.8,3.2 | 2.5 (1.3) | 1.9,3.1 |

| 58 | Patients are more likely to complain if they witness poor communication between nurses and doctors | 2.5 (1.2) | 2.2,2.8 | 2.8 (1.1) | 2.2,3.5 | 2.6 (1.4) | 1.9,3.4 | 2.2 (1.1) | 1.6,2.7 |

| Cluster 4, Impediments to patient care | 2.9 (1.2) | 2.6,3.2 | 2.9 (1.2) | 2.2,3.7 | 2.9 (1.2) | 2.2,3.5 | 2.9 (1.1) | 2.3,3.5 | |

| 60 | Unprofessional conduct (e.g., shouting) between nurses and doctors needs to be reported | 3.8 (1.2) | 3.4,4.1 | 3.7 (1.4) | 2.8,4.5 | 3.8 (1.3) | 3.1,4.5 | 3.8 (1.0) | 3.3,4.3 |

| 35 | Workplace bullying impacts communication | 3.7 (1.4) | 3.3,4.1 | 3.6 (1.4) | 2.7,4.4 | 3.9 (1.4) | 3.2,4.6 | 3.7 (1.3) | 3.0,4.3 |

| 57 | Conflict can negatively affect the clinician’s wellbeing | 3.3 (1.2) | 3.0,3.6 | 3.7 (1.0) | 3.2,4.3 | 2.7 (1.1) | 2.2,3.3 | 3.4 (1.2) | 2.9,4.0 |

| 59 | Having English as a second language may impact nurse-doctor communication | 2.8 (1.4) | 2.4,3.2 | 2.7 (1.6) | 1.8,3.6 | 3.2 (1.3) | 2.5,3.9 | 2.5 (1.3) | 1.9,3.1 |

| 33 | Clinicians with a heavy caseload can be less effective at communicating | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.5,3.2 | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.0,3.5 | 2.5 (1.3) | 1.8,3.2 | 3.2 (1.3) | 2.6,3.8 |

| 30 | Personal issues (e.g., family stress) can impact communication | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.4,3.1 | 3.3 (1.3) | 2.5,4.0 | 2.5 (1.2) | 1.9,3.1 | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.1,3.0 |

| 56 | Poor communication between nurses and doctors may lead to people taking time off work | 2.6 (1.3) | 2.3,3.0 | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.1,3.6 | 2.7 (1.4) | 2.0,3.5 | 2.3 (1.2) | 1.8,2.9 |

| 62 | Critical comments negatively impacts the quality of communication | 2.6 (1.3) | 2.2,2.9 | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.0,3.5 | 2.5 (1.5) | 1.8,3.3 | 2.4 (1.3) | 1.8,3.1 |

| 34 | Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is a barrier to effective communication | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.6,2.2 | 1.2 (0.6) | 0.9,1.5 | 2.1 (0.9) | 1.7,2.6 | 2.2 (1.2) | 1.6,2.8 |

| Cluster 5, Interpersonal skills | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.3,3.0 | 2.7 (1.3) | 1.9,3.5 | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.1,3.3 | 2.6 (1.2) | 2.0,3.1 | |

| 65 | Effective communication is a skill that needs to be taught when nurses and doctors are in training | 3.9 (1.2) | 3.5,4.2 | 4.0 (1.0) | 3.4,4.6 | 3.7 (1.3) | 3.0,4.3 | 4.0 (1.4) | 3.3,4.7 |

| 27 | Clinicians need to be approachable | 3.8 (1.2) | 3.4,4.1 | 3.7 (1.0) | 3.2,4.3 | 3.5 (1.5) | 2.8,4.3 | 3.9 (1.1) | 3.4,4.5 |

| 26 | The quality of communication between nurses and doctors can influence the ward atmosphere | 3.4 (1.3) | 3.0,3.8 | 3.4 (1.3) | 2.6,4.1 | 3.3 (1.4) | 2.6,4.0 | 3.5 (1.3) | 2.9,4.1 |

| 20 | Orientation of new staff improves effective nurse-doctor communication | 3.0 (1.3) | 2.7,3.4 | 2.9 (1.5) | 2.0,3.8 | 3.2 (1.4) | 2.5,4.0 | 3.0 (1.2) | 2.4,3.6 |

| 32 | The volume of information shared between nurses and doctors can impact understanding | 3.0 (1.2) | 2.6,3.3 | 3.4 (1.0) | 2.8,3.9 | 2.9 (1.2) | 2.3,3.5 | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.1,3.3 |

| 64 | Senior clinicians need to proactively help resolve conflicts between nurses and doctors | 2.8 (1.4) | 2.4,3.2 | 2.7 (1.5) | 1.8,3.5 | 3.2 (1.2) | 2.6,3.8 | 2.6 (1.4) | 1.9,3.3 |

| 24 | Finding time for informal discussions about how to improve patient care is important | 2.7 (1.4) | 2.3,3.1 | 2.7 (1.5) | 1.8,3.5 | 3.4 (1.4) | 2.6,4.1 | 2.0 (1.2) | 1.5,2.6 |

| 55 | Technology can be used to improve communication between nurses and doctors | 2.7 (1.4) | 2.3,3.1 | 2.8 (1.4) | 2.0,3.6 | 2.6 (1.6) | 1.8,3.4 | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.1,3.3 |

| 18 | Using the clinicians name in discussion improves communication | 2.5 (1.4) | 2.1,2.9 | 2.4 (1.6) | 1.4,3.3 | 2.9 (1.3) | 2.2,3.6 | 2.3 (1.2) | 1.7,2.9 |

| 21 | Communication is improved if nurse and doctors spend time getting to know each other | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.0,2.7 | 2.5 (1.2) | 1.8,3.2 | 2.4 (1.3) | 1.8,3.1 | 2.0 (1.2) | 1.5,2.6 |

| 10 | Clinicians have a different scope of practice | 2.2 (1.4) | 1.9,2.6 | 1.9 (1.3) | 1.1,2.7 | 2.2 (1.4) | 1.5,2.9 | 2.5 (1.4) | 1.9,3.2 |

| 46 | Doctors’ use of medical jargon impacts understanding by nurses | 2.1 (1.2) | 1.8,2.5 | 2.4 (1.5) | 1.5,3.2 | 2.0 (1.1) | 1.4,2.6 | 2.0 (1.2) | 1.5,2.6 |

| 68 | Doctors need to lead nurse-doctor communication | 2.0 (1.3) | 1.6,2.3 | 2.2 (1.6) | 1.3,3.1 | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.1,2.1 | 2.2 (1.3) | 1.6,2.8 |

| 31 | Clinicians with more clinical experience are better at communicating | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.6,2.2 | 2.1 (1.5) | 1.3,3.0 | 1.8 (1.0) | 1.3,2.3 | 1.9 (1.0) | 1.4,2.4 |

| 16 | Nurses need to lead nurse-doctor communication | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.5,2.0 | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.1,2.1 | 2.0 (0.9) | 1.5,2.4 | 1.6 (1.1) | 1.1,2.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).