1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the causative agent of the current COVID-19 global pandemic, proclaimed a public health emergency of global concern by the World Health Organization (WHO) between March 2020 and May 2023 [

1].

As of 5 July 2023, there have been 767,726,861 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 6,948,764 deaths caused by SARS-CoV-2 since the beginning of the pandemic [

2]. In addition, an estimated 20 million excess deaths linked to the pandemic have been reported, apart from the emerging long-term sequelae, referred to as Post-COVID-19 condition (PCC), Long COVID, or Post acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) [

3,

4,

5,

6].

As the COVID-19 pandemic emerged and it became clear that vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 would be essential in managing severe outcomes and alleviating pressure on healthcare systems [

7], public interest was raised on potential vaccine developments and technologies that would enable fast delivery of vaccines. This was accompanied by concerns in media and social media on the speed at which these vaccines would be developed and approved. Already at these early stages, there was speculation on potential opposition to vaccines developed at pandemic speed [

8,

9] and the challenge of achieving a high vaccination uptake was highlighted. This was particularly acute as many parts of the world, including Europe, were already reeling from effects of vaccine hesitancy, which had prompted the European Commission (EC) and European Union (EU) Member States to launch several initiatives in 2018 to improve confidence in vaccines for routine immunisations [

10]. Early in the pandemic, academics and public health experts alike raised the need for proactive communication to anticipate (‘prebunk’) potential misinformation or deliberate attempts to disinform the public [

11].

With the approval of the first vaccine in the EU against COVID-19, via the European Medicines Agency (EMA, also referred to as “The Agency”) [

12] and after the start of vaccination campaigns by EU national health regulatory authorities, a significant decrease in severe disease and deaths have been observed thanks to vaccination. In particular, a greater reduction was observed in the countries where vaccination reached high coverage rates, while in EU countries that lagged behind, hesitancy remained an obstacle to vaccine uptake and control of the pandemic [

13]. Despite vaccines’ protective effect against severe disease and death, concerns are regularly exploited by misinformation/disinformation sources on other aspects such as very rare and serious adverse events.

To date, several COVID-19 vaccines are authorized in the EU, four of them using new technologies for vaccine development [

14]. Worldwide, as of 4 July 2023, almost 13.5 billion doses of vaccine have been administered [

2]. As of 11 July 2023, 330,874,923 people in the EU/European Economic Area countries have received a primary vaccination course, which accounts for approximately 73% of the total population, and approximately 65% of adults (18+) has received at least one booster/additional dose [

15].

However, despite differences across EU Member States, a large part of the population remains unvaccinated, often due to concerns aggravated by disinformation about vaccines, including concerns about the safety of new vaccine platforms and the expedited vaccine development [

16,

17].

In the context of a reality characterized by uncertainty about how the COVID 19 situation will evolve in light of new variants, the emergence of waning immunity and a large unvaccinated population, mis/disinformation remains a challenge [

17,

18,

19]. The Agency, as regulatory authority in the EU responsible for evaluating COVID-19 vaccines and their safety monitoring, has communicated extensively on their development and approval in short timeframes to reassure the population that all regulatory standards are complied with, and patient safety is safeguarded [

19]. In the present study, the initial information materials prepared by the Agency have been user-tested to check whether they were informative and understood by EU patients and consumers organisations’ (PCOs) and healthcare professional organisations’ (HCPOs) during the initial introduction of COVID-19 vaccines. The work of national medicines regulatory bodies is critical for public outreach at national and local level. Therefore, to complement the study with the national context, similar stakeholder groups were surveyed in a local hospital setting at University Hospital of Palermo, Italy. The findings in this study highlight the need for evidence-based communication approaches during a public health crisis and in a preparedness setting.

3. Results

3.1. Web analytics of EMA COVID-19 materials reveals frequent visits and generally good reception

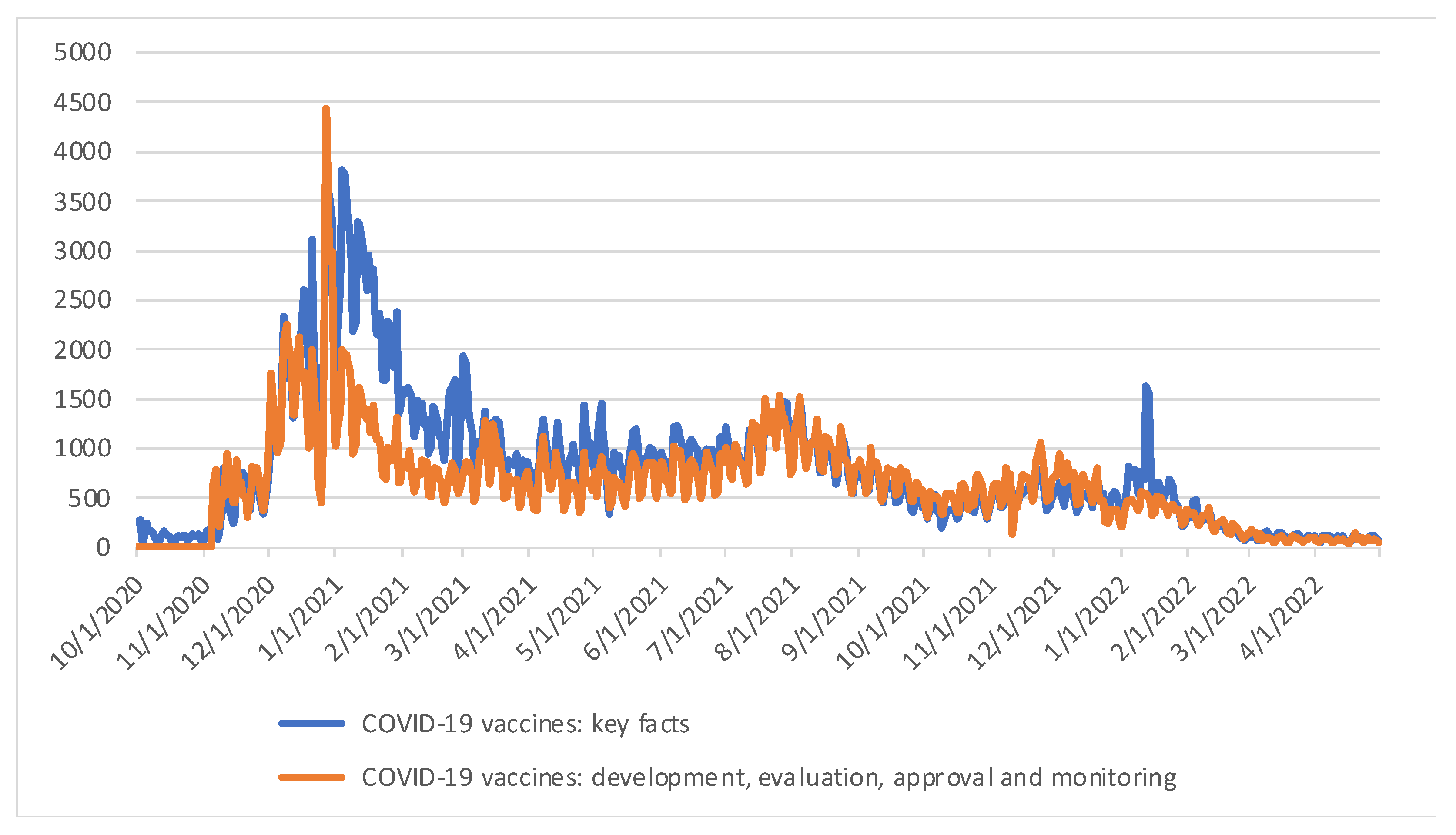

To determine whether EMA’s information on COVID-19 vaccines was being used by the public, a web usage analysis of EMA’s webpages displaying the core content of Tier 1 and Tier 2 materials was carried out. “COVID-19 vaccines: key facts” (Tier 1) was published on 1 October 2020 [

19] and the webpage “COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring” was published on 5 November 2020 (Tier 2) (19). Both webpages were published before the first COVID-19 vaccine was approved in the EU, to anticipate mis- and disinformation circulating on social media regarding accelerated approvals.

The “COVID-19 vaccines: key facts” webpage has received 463,714 visits since its publication until cut-off date of 30 April 2022 with a mean visit duration of 47 seconds. The “COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring” webpage has received 375,524 visits and a mean visit duration of 58 seconds. Visitors rated the “COVID-19 vaccines: key facts” webpage 1.6 stars out of 5 stars (n=647). The rating of the “COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring” webpage is 1.7 stars out of 5 stars, from 627 ratings (

Table 1).

Both webpages received most traffic in descending order from: search engines, direct entry from the EMA corporate website and redirection from other websites. 6 out of the top 10 websites that drive traffic to the “COVID-19 vaccines: key facts” webpage are websites developed by Member States of the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom. This is also the case for 7 out of the top 10 websites driving traffic to the “COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring” webpage. The other top 10 websites are EU websites (Supplementary

Table 1). The Member States directing their citizens most often to the “COVID-19 vaccines: key facts” and “COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring” webpages were Czech Republic, Ireland, Romania, UK, France, Spain, and Belgium.

The webpages are constantly visited, with a peak period from the end of December 2020 to the beginning of February 2021 (

Figure 1), which coincides with the period around the approval of the two first COVID-19 vaccines using novel mRNA technology. The content of these pages has been repurposed by EMA in other communication and outreach activities on COVID-19 vaccines. These webpages have been updated with relevant information as the pandemic and scientific knowledge progressed, however the core messages subject to the user-testing remained the same.

3.2. Survey participant profiling

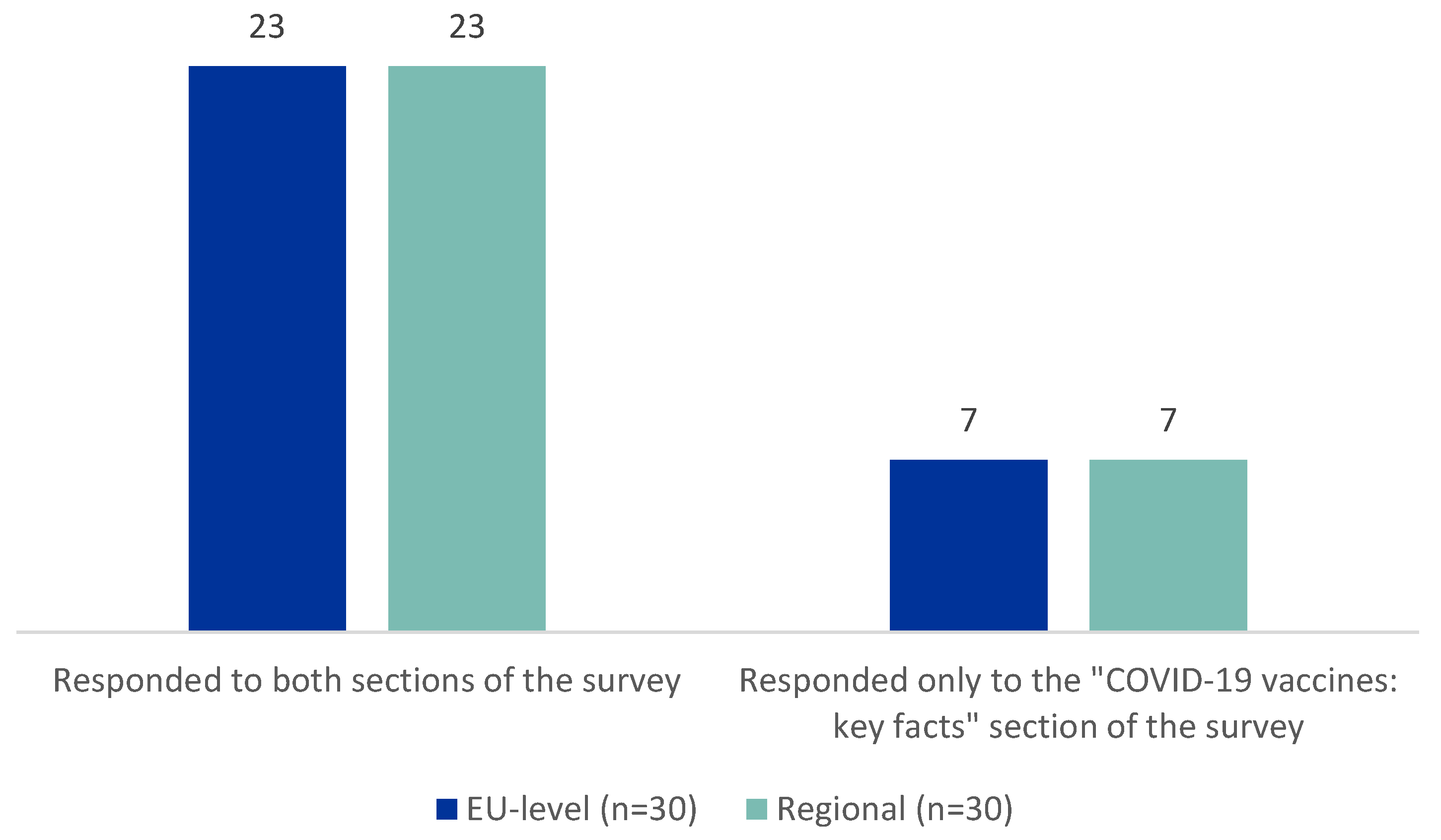

A survey was sent to EU stakeholders to determine if both Tier 1 and Tier 2 documents are informative and well understood, and to explore the public’s preferred communication channels. A total of 30 participants completed the EU survey, as shown in

Figure 2A. Thirteen participants from HCPO participated in the survey. The next stakeholder group with the most participation was the PCO, with 8 respondents. One of the respondents ticked the option “other” for the stakeholder groups questions (see survey questions on the

Supplementary Materials), specifying that they were part of an organisation mainly grouping researchers in a specific therapeutic area. Researchers categorised this respondent as a PCO because their organisation provides patient representation to EMA committees. The smallest stakeholder group was the individual HCPs with three respondents.

The survey for regional Italian stakeholders was also completed by 30 participants, as shown in

Figure 2B. From HCPO, 8 representatives participated in the survey, while 12 were individual HCPs. The next stakeholder group with the most participation was individual patients, with 7 respondents. Finally, 3 of the respondents were representatives of patient/consumers organizations.

In both settings, 23 out of 30 participants completed both sections of the survey, Tier 1 and Tier 2 (

Figure 3).

3.3. Preferred information sources for patients, consumers, healthcare professionals and organisations at EU and regional level

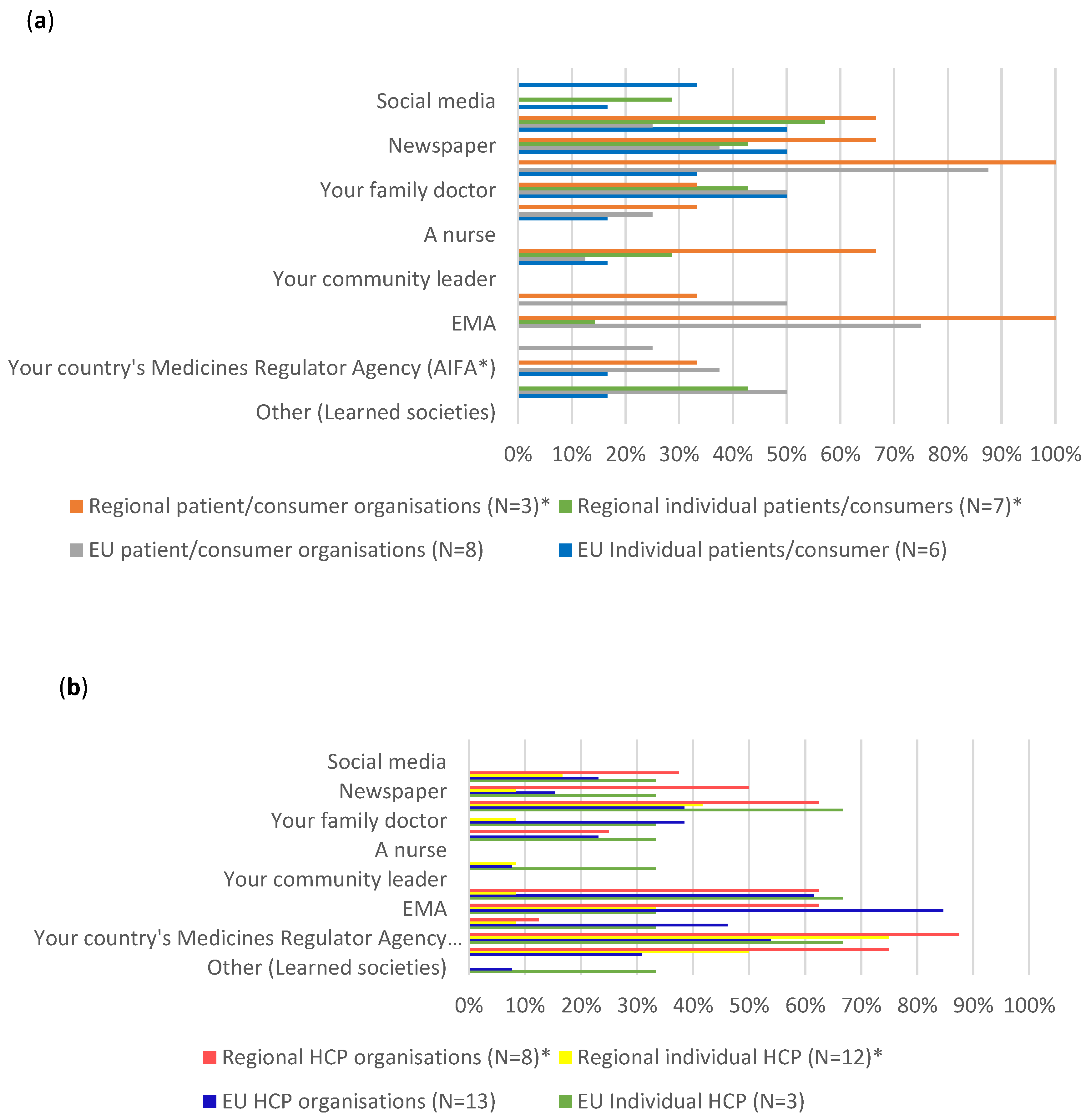

Participants in both the EU and Italian surveys where asked which sources they would consult to find information about COVID-19 vaccines and similar trends were observed in both settings (

Figure 4).

3.3.1. Individual patients/consumers and PCOs (Figure 4A)

In the case of both the EU level and the regional level individual patients and consumers, their most consulted sources were internet search engines (respectively 50% and around 57%), newspapers (respectively 50% and around 43%), and their family doctor (respectively 50% and around 43%), followed by scientific journals (around 33%), with another approximately 33% not knowing where to look for information.

EU level PCOs on the other hand, preferred to consult scientific journals (100%), followed by EMA sources (75%), their family doctor, their country’s Ministry of Health and WHO (50%). While regional PCO indicated a similar preference to consult scientific journals and EMA sources (100%), around 67% of them also use internet search engines, family/colleagues/friends and newspapers as sources of information.

3.3.2. Individual HCPs and HCPOs (Figure 4B)

The EU level individual HCPs main preferences included consulting scientific journals, WHO and their country’s Medicines Regulator Agency (around 67%). Only approximately 33% indicated that they consult EMA for information. The EU HCPO preferred to consult EMA (around 85%), WHO (around 62%), their country’s Medicines Regulator Agency (around 54%), ECDC (around 46%), followed by their family doctor and scientific journals (around 38%). Two participants, one from the individual HCPs and the other from healthcare professionals’ organisations, stated that they would consult learned societies, when specifying other sources of information they would consult.

Both individual HCPs and HCPO at regional level mainly consulted the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) (respectively 75% and around 87.5%), the Italian ministry of health (respectively 50% and 75%) and scientific journals (respectively approximately 42% and 63%). Similar to the EU context, only around 33% of regional individual HCPs said they use EMA as a source of information. On the other hand, around 63% of the HCPOs consult EMA for information.

In general, the preferred sources of information among stakeholder groups showed similar trends between EU-level participants and regional participants. The individual patients and consumers consulted more often mass media sources while the organisations and individual HCPs consulted multiple sources and professional audiences, especially health authorities. These trends are important when considering how to reach a particular stakeholder group.

3.4. Understanding of key messages by stakeholders at EU or regional level

As part of the survey, participants were asked to read several key messages in Tier 1 and 2 materials to determine if these were clear and understandable.

The messages chosen for user testing referred to key concepts that EMA identified as potentially being able to be misinterpreted or subject to misinformation. Three Tier 1 messages were presented. First of all, a safety message was included to address the misperception that the speedy development of COVID-19 vaccines entails that corners would be cut with safety testing. Secondly, a message on the approval process was included to address existing concerns that COVID-19 vaccines are not properly studied. This message reiterated that a scientific evaluation of the vaccines is performed by EMA. Furthermore, an explanation of all elements of the EMA response to ensure quality, safety, and efficacy of vaccines was provided.

The three messages of the Tier 2 material focused firstly on the timeline of the safety monitoring of COVID-19 vaccines, secondly on the explanation of a rolling review, a new regulatory process which enables the Agency to assess data as they arise and expedites the process, and lastly on factors that helped the development of COVID-19 vaccines.

For Tier 1, the results showed that the messages on the safety requirements for COVID-19 vaccines were well understood with around 92% of correct answers among the EU-level stakeholder groups and 100% correct answers among regional stakeholder groups (

Table 2). On the message on the approval process, 100% of EU-level and regional level stakeholders responded correctly. However, when asked a more complex question regarding how EMA ensures that COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective, the participants scored poorly in both contexts with only around 27% of EU level stakeholders and around 35% of regional stakeholders answering correctly. The complexity of the question and the fact that the information needed to provide an answer was spread across the Tier 1 document and therefore not easy to find might explain these results.

The three messages of Tier 2 were well understood. Around 95% of EU-level respondents gave the correct answer to the first question on safety monitoring, while around 80% of the regional stakeholders replied correctly as well. 100% of both the EU-level and regional level respondents gave a correct response to the question on the rolling review and the third question on the development of COVID-19 vaccines was correctly answered by 79% of EU-level and around 81% of regional level respondents.

The answer distribution among stakeholders and between EU-level and regional participants were uniform, suggesting that overall, the key messages were well understood among the participants.

3.5. Participants’ feedback on usefulness, language and level of detail

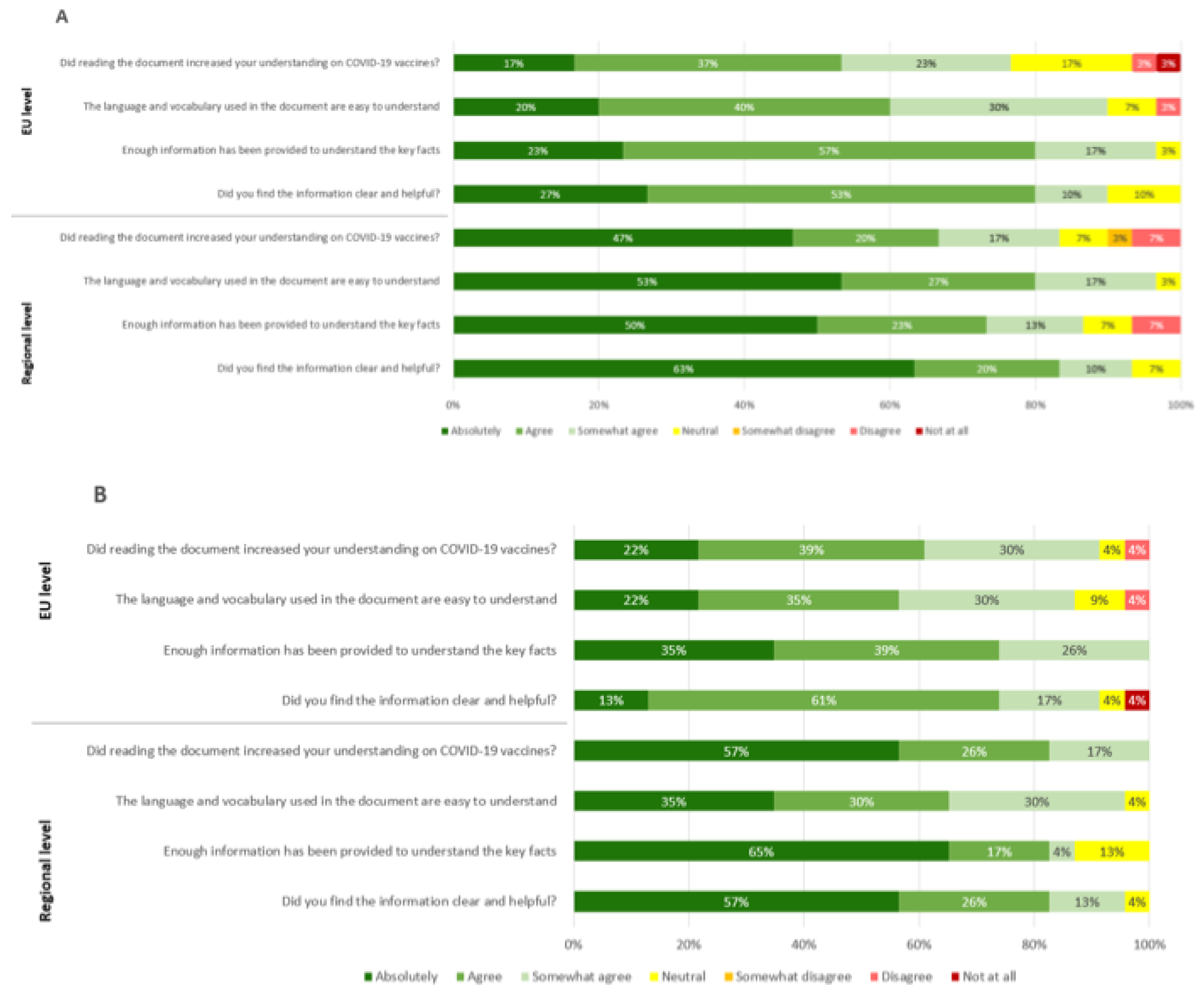

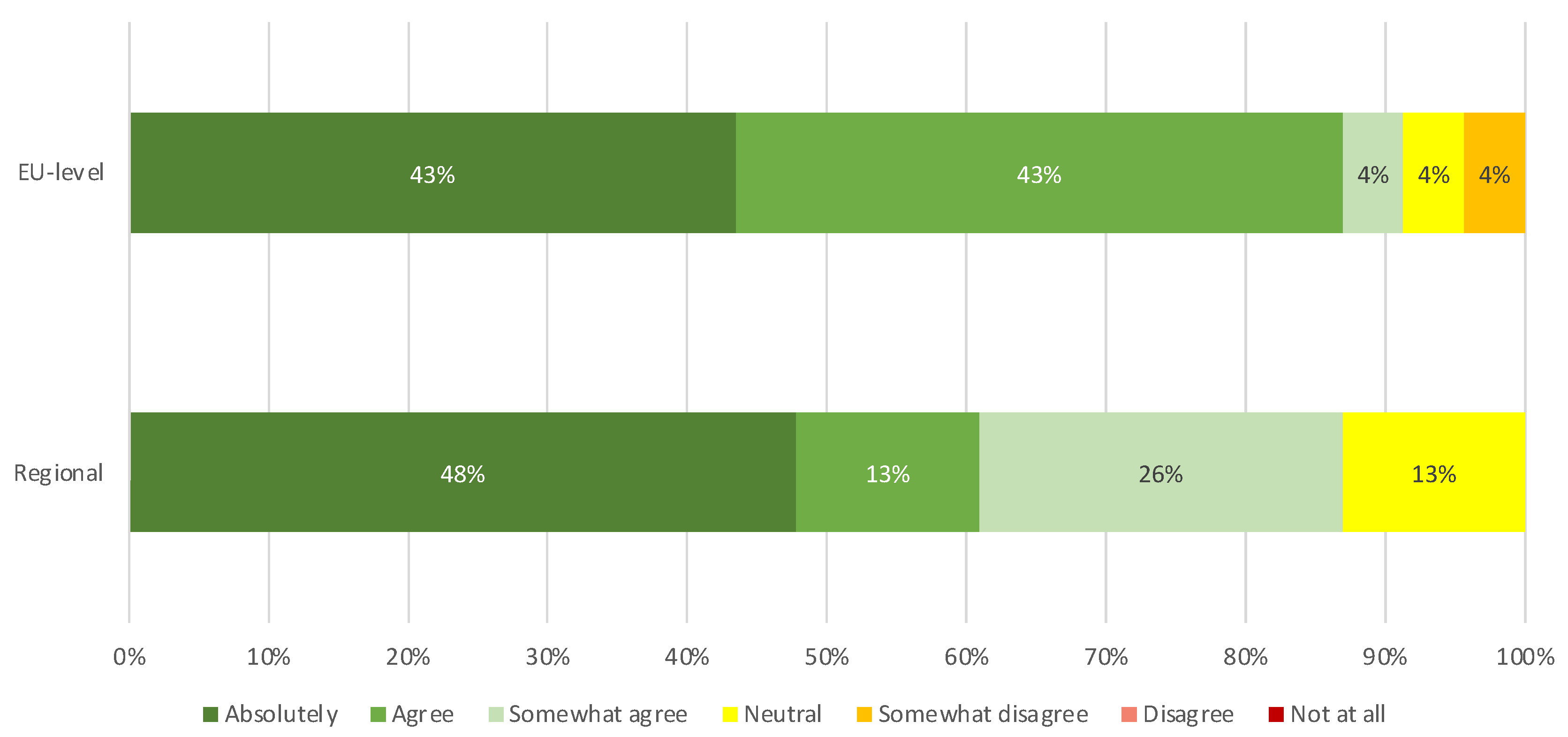

EU and regional level participants provided feedback on the understanding of the information, the language used, the level of detail provided and the usefulness and clarity of the information of both Tier 1 and Tier 2. The percentages of people that indicated “absolutely” and “agree” are summarised to obtain the following results. Not all participants responded to the questions related to Tier 2, explaining the difference in total amount of respondents between Tier 1 and Tier 2.

3.5.1. Feedback on Tier 1

Considering the feedback of participants of the EU survey on Tier 1, 54% of participants (16 out of 30) indicated an increase in their understanding on COVID-19 vaccines after reading the document and 60% (18 out of 30) thought the language and vocabulary was easy to understand. In addition, 80% (24 out of 30) were of the opinion that Tier 1 contained enough information to understand the key facts of the document, as shown in

Figure 5A. 80% (24 out of 30) also indicated that they found the information to be both clear and helpful.

Considering the participants of the regional survey on Tier 1, 67% (20 out of 30) of respondents indicated an increase in their understanding on COVID-19 vaccines after reading the document and 80% (24 out of 30) found the language and vocabulary easy to understand. Furthermore, 73% (22 out of 30) of respondents thought enough information was provided in Tier 1 to understand the key facts of the document and 83% (25 out of 30) found the information clear and helpful.

3.5.2. Feedback on Tier 2

For Tier 2, 61% (14 out of 23) of the participants to the EU survey declared that their understanding of the COVID-19 vaccines increased after reading the document and 57% (13 out of 23) found the language and vocabulary to be easy understandable. 74% of EU survey respondents (17 out of 23) are of the opinion that enough information was provided. The information was found clear and helpful by 74% of respondents (17 out of 23) (

Figure 5B).

In the Regional survey, 83% (19 out of 23) indicated an increase in their understanding on COVID-19 vaccines after reading the document and 65% (15 out of 23) considered language and vocabulary easy to understand. In addition, 82% (19 out of 23) thought that the document reported enough information to understand the key facts and 83% (14 out of 23) found that graphics were clear and helpful.

The results showed that in general the regional participants have a stronger positive opinion of both documents. For Tier 1, the regional “absolutely” response ranged between 47% to 63%, compared to EU-level “absolutely” response between 17% to 27%. For Tier 2 the regional “absolutely” response ranged from 35% to 65% while the EU-level response to “absolutely” ranged from 13% to 43%. Overall, the “absolutely/agree” combined results are similar between EU and regional level participants for both documents.

3.6. Participants feedback on visuals to convey regulatory principles or processes.

Stakeholders have often requested the use of visuals to explain regulatory concepts or processes and the Agency prepared some visual materials for its initial COVID-19 vaccines information. Tier 2 materials included a number of figures that the Agency has subsequently repurposed in a variety of materials on COVID-19 vaccines (see Supplementary Material 1_Tier 2). In

Figure 6, when asked about whether visuals and graphic representations were generally considered helpful, 86% (20 out of 23) EU-level and 61% (14 out of 23) regional participants found the graphics helpful to convey the key concepts.

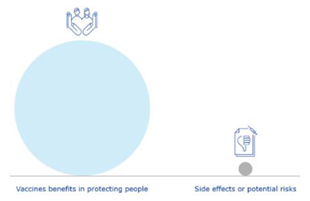

Participants were asked to review some alternatives for graphics included in Tier 2. Two visuals representing pooling of resources and the positive benefit-risk balance were user tested, as these were the visuals that generated the most discussion during their preparation. EU-level participants found both pooling of resources visuals clear and easy to understand (65%; 15 out of 23), while the regional participants did not (74% answered ‘no’ or ‘don’t know’; 17 out of 23) (

Table 3). When asked which of the two pooling of resources visuals they prefer, the second visual representing an organised pooling of resources was the preferred visuals for EU and regional level participants (69% and 100% respectively).

Three visuals representing the concept of a positive benefit-risk balance were user-tested, with 87% (20 out of 23) and 74% (17 out of 23) of EU and regional participants agreeing respectively that they are clear and easy to understand. Participants preferred the visual representing a scale weighting benefits versus risks, with 60% (12 out of 20) of EU and 83% (15 out of 18 of regional participants selecting this visual over the other two options.

3.7. Participants preferred statement about COVID-19 vaccines safety

The survey user-tested two key messages that EMA can use to explain COVID-19 vaccines’ safety when considering the benefits (

Table 4). Both statements explain the same message, but the wording differs. At the EU-level, the first safety statement [

Like any medicine, vaccines have benefits and risks, and although highly effective, no vaccine is 100% effective in preventing a disease or 100% safe in all vaccinated people] was preferred by individual patients and consumers (100%; 2 out of 2) and HCPOs (82%; 9 out of 11). The second safety statement [

Like any medicine, vaccines have benefits and risks, and the conditions of marketing authorisation aim at maximising benefits and minimising risks] was preferred by the individual HCPs (100%; 2 out of 2). PCOs preferred either statement (4 out of 8).

At regional level, the first safety statement was preferred by HCPOs (57%; 4 out of 7). The second safety statement was preferred by individual patients and consumers (60%; 3 out of 5) and individual HCPs (64%; 7 out of 11).

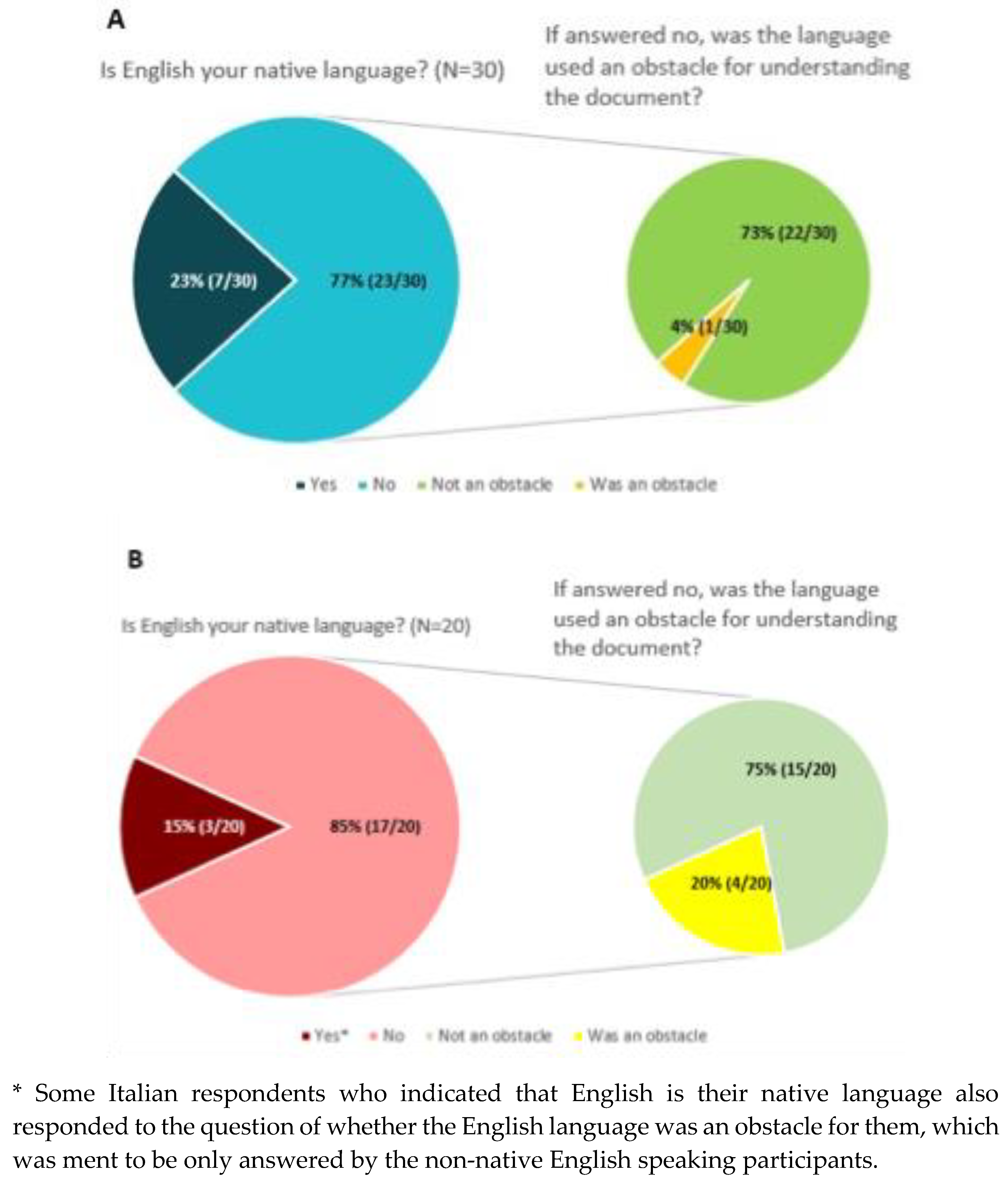

3.8. Feedback on shareable/audiovisual materials, translation into official EU languages and missing information

The survey further explored open feedback from stakeholders on ideas for other types of formats, translations into EU languages and whether any key information was missing.

To identify other possible formats that could be used to share COVID-19 vaccines information, the survey included a question to see if the participants would be interested in having “COVID-19 vaccines: key facts” in another shareable format, besides the webpage (Supplementary material 1). Around 63% of EU-level participants (19 out of 30) and around 67% of regional stakeholders (23 out of 30) responded positively to this. Two Italian respondents elaborated that an updated document should be simpler and with a more concise language. PDF documents, videos, and social media were suggested by participants as types of shareable formats they are interested in.

Although most of the participants (>70%) stated that they did not have an issue understanding the documents in English (

Figure 7), 4% of European level participants (1 out of 30) and 20% of Italian participants (4 out of 20) indicated that the English language of the materials was an obstacle for understanding the document.

The survey also asked participants to identify areas where more information is needed. More information on COVID-19 vaccines safety information was requested by two EU-level HCPOs, one EU-level individual HCP and two EU-level PCOs. Indeed, the materials subject to user-testing are non-product specific and were published before individual vaccines were approved and rolled out in vaccination campaigns. EMA has since published regular public safety updates on the approved vaccines on the corporate website [

25]. This is a specific tool that EMA developed to keep stakeholders informed on the safety aspects during the most acute phase of the pandemic and was published as an additional transparency measure to all the information that EMA routinely publishes on medicines approved via the Agency.

3.9. Exploring participants’ willingness to get vaccinated after reading the COVID-19 information materials

In order to explore whether reading COVID-19 materials impact people’s willingness to be vaccinated, participants were asked to rank their willingness to get vaccinated at different timepoints: before reading the materials, after reading Tier 1, and after reading Tier 2. The vaccination status of the respondents was unknown.

Most stakeholder groups at both EU and regional level did not change their willingness after reading Tier 1 and Tier 2 (

Table 5). Compared to the individuals, representatives of PCOs and HCPOs are more willing to get vaccinated and among all stakeholder groups and EU and regional level participants, reading the materials had only little impact on their willingness to get vaccinated.

3.9.1. After reading Tier 1

At EU level, 50% (3 out of 6) of individual patients/consumers, 67% (2 out of 3) of individual HCPs, 63% (5 out of 8) of PCO and 77% (10 out of 13) of HCPO did not change their willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccine after reading Tier 1. A decrease in willingness is observed in 33% (2 out of 6) of individual patients/consumers and 13% (1 out of 8) of PCO.

At regional level, the willingness to get vaccinated of the majority of respondents did not change after reading Tier 1. However, 14% (1 out of 7) of individual patients/consumers and 8% (1 out of 12) of individual HCPs indicated a decrease in their willingness to get vaccinated. 14% (1 out of 7) of individual patients/consumers had an increase in willingness.

3.9.1. After reading Tier 2

The participants’ willingness to get vaccinated after reading Tier 2 was also analysed. The fact that not all the participants of the study responded to this question needs to be taken into account.

At EU-level, 50% of individual patients/consumers (1 out of 2) and individual HCPs (1 out of 2) showed no change. 63% (5 out of 8) of the PCO and 73% (8 out of 11) of HCPO had the same response. While an increase in willingness is observed in 50% (1 out of 2) of individual patients/consumers and 25% (2 out of 8) of the PCO and 27% (3 out of 11) of the HCPO, a decrease is found in 50% (1 out of 2) of the individual HCPs and 13% (1 out of 8) of the PCO. Interestingly, one EU-level healthcare professional first increased its willingness after reading “Key facts on COVID-19 vaccines” and later decreased its willingness to get vaccinated after reading “COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring”.

At the regional level, 80% (4 out of 5) of individual patients and consumers, 91% (10 out of 11) of individual HCPs and 100% of PCO and HCPO did not change their willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccine after reading the documents.

One (20%) regional individual patient/consumers and 9% (1 out of 11) regional individual healthcare professional indicated a decrease in willingness to get vaccinated.

3.10. Recommendations from the user-testing analysis

The quantitative and qualitative results from the survey were used to draw recommendations for regulators to improve information materials according to areas of improvement or missing information identified by participants. The quantitative data shows an overall satisfaction of the participants with both documents. In

Table 6, a summary of the actions derived from the survey results is given and how EMA has implemented such recommendations. As most participants preferred benefit-risk visual A, the “COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring” webpage and document were updated, replacing figure C in

Table 3 (balance suggested by comparing sizes) by A (balance suggested using a scale). Some text and headings were updated to improve understandability, in response to the substantial incorrect answers to one comprehension question about “COVID-19 vaccines: fey facts” and to the participants’ calls to use as much lay language as possible. Due to the fact that these materials were created in the context of a public health emergency, it was not possible to conduct a user-testing study before publishing these materials. However, by introducing retrospective improvements, EMA has been able to address the public’s information needs and formatting preferences captured in this study.

4. Discussion

This research aimed to user-test EMA’s core information materials on COVID-19 vaccines that were repurposed through different channels and communication tools during the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, the EMA webpages containing the information subject to this study are regularly visited since their publication, with visit peaks coinciding with the start of the COVID-19 vaccination campaigns in Europe, announcements of COVID-19 vaccines approvals, start of rolling review, and evaluation of safety signals.

Subjecting EMA’s core content to user-testing is relevant not only for selecting messages and figures for webpages but also since this content is repurposed by regulators in response queries from patients and HCPs, media interviews and explaining vaccine development and regulatory oversight during public stakeholder meetings held by EMA. These messages were included in public webpages before the first COVID-19 vaccine was approved in the EU to anticipate mis- and disinformation, as well as to address legitimate stakeholders’ questions and concerns circulating on (social) media with regard to the fast-track development, evaluation and approval of COVID-19 vaccines (18,19). As described by Blastland et al., obtaining a better understanding of the target audience and their concerns is required to be able to prebunk misinformation [

11].

The web analytics of the two webpages show a low average rating of the materials. This contrasts with the generally positive reception of the materials by the stakeholders included in this study. Interesting to note is that web ratings became less favourable as time went on. The comments accompanying the low ratings did not only reflect vaccine sceptic narratives, but also often voiced genuine concerns about the COVID-19 pandemic and the vaccines. This again shows the importance of addressing misinformation and tackling disinformation. However, also many positive comments were given on the clarity and transparency of the information.

The EU-level participants were predominantly members of organisations, followed by the individual patients, consumers and HCPs. This proportion differs in the regional context, where the group with the most participants were individual HCPs, followed by HCPOs and individual patients and consumers. This broad profile of participants ensured a distributed overview of each stakeholder´s preferences and needs. In general, during the first phases of the European vaccination campaign against COVID-19, individual HCPs and HCPOs played a key role in promoting correct information and counselling on COVID-19 vaccines available [

26,

27]. Moreover, they represented, in all EU countries, the first target of vaccination and, consequently, they have become a model for specific subgroups of the general population that were subsequently vaccinated (elderly, fragile and high-risk groups, etc.) [

28,

29]. At the same time, the materials published on EMA’s website were, especially at regional level, more consulted by HCPs (individual or organizations) and PCOs.

The choice to compare the EU with the regional Italian context data is relevant in order to conduct an in-depth evaluation of the readability and the reproducibility of the user-testing material also in local context, where there could be participants with a limited knowledge of English, the working language of EMA [

30]. From the results obtained at local level, for both the individual stakeholders and the PCO, the language did not represent a considerable limit in the comprehension of the contents of the document. The extensive use of graphics to support the content of the user-tested materials may be a contributing factor to this. The Agency will however look longer term into increasing multilingual information materials.

In order to guarantee an appropriate data comparison, the authors tried to administer the survey to similar patterns of respondents at EU and Regional Level. Effectively, a similar distribution of representatives and individual HCPs and/or of consumers’ and patients’ organization was observed. Moreover, in both cases, 23 participants out of 30 completed Tier 1 and 2 of the survey. The possibility to translate Tiers 1 and 2 content into local EU languages could be considered for documents that are made available for the general public, in order to promote a wide dissemination of information, also among people with low English knowledge or low health literacy level. The current user-testing of materials was carried out on a population of HCPs (individual or representatives) and representatives of PCO that may have a better knowledge of English language and better capacity of understand scientific language and regulatory processes (as also reaffirmed by the results obtained).

Based on the participants who responded to this survey individual patients and consumers mainly consulted internet search engines, newspapers and their family doctor. It therefore seems crucial that regulators use these same channels that are easily accessible to the general population in order to effectively counteract the circulation of misinformation. As for the doctors themselves, it is also necessary for them to receive complete and clear information from authoritative and unbiased sources since they represent a point of reference for the population, as also shown by the results of the ADVANCE project [

31].

The role of HCPs in countering mis- and disinformation among their patients has also been emphasised by the Employment, Social Policy, Health and Consumer Affairs (EPSCO) Council on the 9th of December 2022, in which ministers responsible for policy on employment, social affairs, health and consumers from EU member states and relevant European Commissioners participate [

32,

33]. This Council concluded that in the context of vaccine hesitancy, the EU Member States and the European Commission should make efforts to boost HCPs’ ability to do this by providing training opportunities to HCPs. The EPSCO Council also proposed that the European Commission should set up a vaccine hesitancy expert forum with the aim to increase vaccination across the EU [

34].

Based on the participants’ feedback, findings show that, compared to individuals, representatives of PCOs and HCPOs are more willing to vaccinate. This observation can probably be attributed to an increased trust in the regulatory system of these representatives. Trust in scientific and medical institutions is one of the strongest motivators for vaccine acceptance and being part of such institutions increases vaccination numbers precisely because of a lower exposure to misinformation [

35]. The analysis also shows that the willingness of most stakeholders participating in the survey at European and regional level to vaccinate did not change after reading Tiers 1 and 2. However, while some increases in willingness were observed, for some other respondents a decrease in willingness to vaccinate was reported. This suggests that materials from regulators may contribute to changing the attitudes towards vaccination of a small subset of the population. Important to consider is that analysis numbers were low and the single intervention (EMA information) was not dissected from other information sources (media etc.). These results are consistent with the findings of a study by Kerr et al. that assessed a low impact of information explaining the risks and benefits of vaccines on people’s behavioural intentions. In this study, they included EMA’s website material corresponding to “Tier 2” as one of the researched information materials and did not detect a significant difference between the group that read Tier 2 (87.6% of respondents showed willingness) and the control group (86.9% of respondents showed willingness) [

36]. Despite these results, it seems necessary to promote transparent information provided by authorised bodies in order to undermine any kind of misinformation. During a public health emergency, characterised by considerable scientific uncertainty and political leaders acting as frontline crisis managers, it often becomes a challenge to ensure that evidence-based recommendations take precedence over political interests [

37]. The recent pandemic has shown how accurate communication from official sources, such as EMA or national medicines agencies, is essential for building confidence in vaccines. A study by Roozenbeek et al. emphasizes this as well by stating that scientific information might be trusted more if people perceive its communication as transparent and open and that it might result in a reduction of people’s reliance on misinformation [

38]. Fake news, especially when it relates to health, affects millions of citizens through social and digital tools. A hidden “pandemic of information”, a digital infodemic, which causes enormous damage and which, although digital, has a very high cost in terms of human lives in the real world [

39]. Like other infodemics, the COVID-19 vaccine rumour is highly contagious and can spread exponentially around the word and can impact overall vaccine acceptancy [

40]. For this reason, the fight against misinformation must become a priority of institutions at their highest level. Listening to and analysing its circulation through monitoring social and traditional media can be key to identifying trends in the EU and can provide a better understanding of why misinformation is spreading [

41]. In this regard, it is imperative that scientific knowledge is shared through official sources and through simple but effective communication. Also experiences at the local Italian level, which are easily extendable to the general level, show how important accurate, honest and transparent communication is [

42]. Keeping people in the dark makes them more susceptible to misinformation and conspiracy theories. People can handle the truth, even when it involves communication of uncertainty. Half-truths, expressed in the wrong way, can instead prove to be a dangerous boomerang.

As mentioned before and as described by Cavaleri et al. [

43], it is first and foremost essential to listen to the needs and concerns of the population, before undertaking communication activities. Only by doing this, the public’s trust in regulators can be safeguarded. In order to achieve public trust, considering the context of an increased interest in and scientific scrutiny of the Agency’s work, EMA’s communication and engagement activities needed to be adapted. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and with input of the surveys conducted as part of this study, EMA has stepped up its communication and stakeholder engagement activities in several ways. One of the initiatives was the organisation of public stakeholder meetings on COVID-19 vaccines between 2020 and 2021 precisely to attempt to reach that part of the population most at risk of misinformation. These meetings provided scientific experts a platform to address questions and concerns [

19,

43]. Four of these meetings have been organised during the first year of the European vaccination campaign. The Agency has also made the recordings and presentations from EMA’s public stakeholders meeting on COVID-19 vaccines publicly available on its website [

19,

44,

45]. These have been updated with new content as the pandemic progressed and as new vaccines have been approved, in line with new evidence emerging on safety and effectiveness. EMA also keeps the COVID-19 vaccines webpages updated as per participants’ suggestion [

46,

47]. Secondly, visuals to accompany text explanations were incorporated. These visuals aimed to provide an explanation of relevant regulatory concepts and outcomes [

19,

21,

48]. The majority of the participants of this study found visuals to be useful for conveying key concepts: a picture communicates better than a print and this makes it an excellent way of disseminating information. Because visuals have a ‘long half-life’, as they are repurposed by social media channels and other platforms, it is important to user test them as well to ensure effective communication and understanding by the target audience. According to a German study, visual content promotes better communication and increases confidence in vaccination [

49,

50]. Given participants’ requests for more audio-visual materials, EMA also contributed to developing infographics by other institutions such as the European Council, to explain in a simple and intuitive way how COVID-19 vaccines work [

51,

52,

53]. In addition, a scale up of EMA’s media engagement activities took place and pandemic safety updates were introduced and published on a regular basis [

19,

26,

54,

55].

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic provided EMA with the opportunity to improve its transparency. An example of such a measure is the introduction of shorter publishing timeframes for assessment reports and assessed clinical data [

19,

56]. In addition, EU PCOs and HCPOs representatives became part of the Emergency Task Force (ETF) which allowed them to provide input an actively participate in discussions concerning evaluation of individual vaccines and vaccination discussions [

19]. The participation of civil society representatives in ETF is now continued as part of EMA’s extended mandate. The extended mandate, introduced by the European Commission and applicable since 1 March 2022, aims to improve the EU’s preparedness and response to health threats and has a strong focus on transparency. Stakeholder engagement plays an important role in the various operations of the mandate and to ensure that stakeholders are given a platform to interact and discuss with EMA [

57].

While the regional survey revealed information in English was not a barrier to understanding the information, the above-mentioned reasons prompt consideration of the possibility to translate more EMA documents into local EU languages to promote wide dissemination of information to the public and to reach people with low health literacy and knowledge of English. EMA already publishes translations of key documents and information of great relevance and impact in all official EU languages. This includes information on medicines that EMA evaluates, such as overviews of authorised human medicines, medicines of which authorisation has been refused, withdrawn applications, product information for authorised medicines, and referrals of medicines. Furthermore, general information on activities and work of the Agency are translated.

In addition, citizens can send enquiries to EMA and receive a response in the same language [

58]. Another possible way forward could be to translate highlights of the content into all official EU languages.

This study needs to be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, a possible lack or representativeness due to the limited number of participants needs to be taken into account. In this regard, there were a good representation of members of PCOs and HCPOs in the EU survey, while there were more individual HCPs/patients recruited in local hospital at Italian regional level. Secondly, since the surveys were mainly conducted through online recruitment and participants were volunteers, selection bias should be considered as a possible limitation. Thirdly, even though analysis of the regional Italian context reveals similarities in the understanding of key messages, it is unknown how representative this is of other EU regions. This limits the generalizability of the results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G.-Q., and C.C.; methodology, J.G.B. and I.C.; software, M.V.T., N.B. and M.S.; validation, R.G.-Q., M.V.T. , C.C., M.S. and N.B..; formal analysis, I.C., C.C., M.S., N.B. and , M.V.T.; investigation, I.C., C.C., M.S., N.B. ; data curation, R.G.-Q., M.V.T. and, C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C., M.V.T., M.S. and N.B.; writing—review and editing, R.G.-Q and J.G.B.; visualization, M.V.T..; supervision, J.B.G.; project administration, J.B.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Timeline of visits to the webpages on “COVID-19 vaccines: key facts” and “COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring” from the day of publication up to 30 April 2022.

Figure 1.

Timeline of visits to the webpages on “COVID-19 vaccines: key facts” and “COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring” from the day of publication up to 30 April 2022.

Figure 2.

Profile of participants to EU-level survey (a) and Italian regional survey (b) by stakeholder group.

Figure 2.

Profile of participants to EU-level survey (a) and Italian regional survey (b) by stakeholder group.

Figure 3.

Number of participants who completed only the first section (Tier 1) or both sections (Tier 1 and Tier 2) of the survey.

Figure 3.

Number of participants who completed only the first section (Tier 1) or both sections (Tier 1 and Tier 2) of the survey.

Figure 4.

Comparison of preferred sources of COVID-19 vaccines information across stakeholder groups. (a). EU and regional individual patients and consumers and patients and consumers organisations. (b). EU and regional individual healthcare professionals and healthcare professionals organisations.

Figure 4.

Comparison of preferred sources of COVID-19 vaccines information across stakeholder groups. (a). EU and regional individual patients and consumers and patients and consumers organisations. (b). EU and regional individual healthcare professionals and healthcare professionals organisations.

Figure 5.

Participants feedback on usefulness, language and level of detail of COVID-19 vaccines materials. (a) Feedback on Tier 1 “COVID-19 vaccines: key facts” by EU-level (n=30) and regional (n=30) participants. (b) Feedback on Tier 2 “COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring” by EU-level (n=23) and regional (n=23) participants.

Figure 5.

Participants feedback on usefulness, language and level of detail of COVID-19 vaccines materials. (a) Feedback on Tier 1 “COVID-19 vaccines: key facts” by EU-level (n=30) and regional (n=30) participants. (b) Feedback on Tier 2 “COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring” by EU-level (n=23) and regional (n=23) participants.

Figure 6.

EU-level and regional participants’ feedback on whether the graphics help to convey key concepts (Tier 2).

Figure 6.

EU-level and regional participants’ feedback on whether the graphics help to convey key concepts (Tier 2).

Figure 7.

Native English language status and skills for EU-level (a) and Italian regional (b) participants.

Figure 7.

Native English language status and skills for EU-level (a) and Italian regional (b) participants.

Table 1.

EMA web analytics and sources of traffic from the webpages on “COVID-19 vaccines: key facts” and “COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring” from their date of publication on the EMA website until 30 April 2022.

Table 1.

EMA web analytics and sources of traffic from the webpages on “COVID-19 vaccines: key facts” and “COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring” from their date of publication on the EMA website until 30 April 2022.

| |

Title 2 COVID-19 vaccines:

key facts* |

COVID-19 vaccines:

development, evaluation, approval and monitoring** |

| Total unique visits |

463,714 |

375,524 |

| Mean visit duration |

47 seconds |

58 seconds |

| Average star rating |

1.6/5 |

1.7/5 |

Main Sources of traffic

(unique visits) |

1st: Search engines

(272,997) |

1st: Search engines

(134.607) |

| |

2nd: Direct entry from EMA corporate website (92,373) |

2nd: Direct entry from EMA corporate website (123.966) |

| |

3rd: Other Websites

(42,249) |

3rd: Other Websites

(63.778) |

Table 2.

Understanding of key messages of Tier 1 “COVID-19 vaccines: key facts” and Tier 2 “COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring” by stakeholder groups at EU and regional level.

Table 2.

Understanding of key messages of Tier 1 “COVID-19 vaccines: key facts” and Tier 2 “COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring” by stakeholder groups at EU and regional level.

| |

EU-level |

Regional level |

| Correct responses by individual patients |

Correct responses by individual HCP |

Correct responses by PCO |

Correct responses by HCP organisations |

Average percentage across all EU stakeholders |

Correct responses by individual patients |

Correct responses by individual HCP |

Correct responses by PCO |

Correct responses by HCP organisations |

Average percentage across all regional stakeholders |

| Tier 1 key messages on: |

|

| Safety requirements1

|

6 (100%) |

2 (67%) |

8 (100%) |

13 (100%) |

91.75% |

7 (100%) |

12 (100%) |

3 (100%) |

8 (100%) |

100% |

| Approval2

|

6 (100%) |

3 (100%) |

8 (100%) |

13 (100%) |

100% |

7 (100%) |

12 (100%) |

3 (100%) |

8 (100%) |

100% |

| Safe and effective vaccines3

|

1 (17%) |

0 (0%) |

3 (38%) |

7 (54%) |

27.3% |

0 (0%) |

3 (25%) |

2 (67%) |

4 (50%) |

35.5% |

| Tier 2 key messages on: |

|

| Safety monitoring4

|

2 (100%) |

2 (100%) |

7 (88%) |

10 (91%) |

94.8% |

4 (80%) |

8 (73%) |

N.A. |

6 (86%) |

79.7% |

| Rolling review5

|

2 (100%) |

2 (100%) |

8 (100%) |

11 (100%) |

100% |

5 (100%) |

11 (100%) |

N.A. |

7 (100%) |

100% |

| Development6

|

2 (100%) |

1 (50%) |

6 (75%) |

10 (91%) |

79% |

4 (80%) |

7 (64%) |

N.A. |

7 (100%) |

81.3% |

Table 3.

EU and regional level participants’ preferred visuals conveying pooling of resources to fast track medicines approval and a positive benefit-risk balance.

Table 4.

Preferred safety statement by EU and regional stakeholder groups.

Table 4.

Preferred safety statement by EU and regional stakeholder groups.

| |

EU-level (n=23) |

Regional level (n=23) |

| |

Individual patients and consumers’ preference |

Individual HCPs’ preference |

PCOs’ preference |

HCPs’ organisations preference |

Individual patients and consumers’ preference |

Individual HCPs’ preference |

PCOs’ preference |

HCPs’ organisations preference |

| First safety statement proposal1

|

2 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

4 (50%) |

9 (82%) |

2 (40%) |

4 (36%) |

N.A. |

4 (57%) |

| Second safety statement proposal2

|

0 (0%) |

2 (100%) |

4 (50%) |

2 (18%) |

3 (60%) |

7 (64%) |

N.A. |

3 (43%) |

Table 5.

Willingness to get vaccinated with COVID-19 vaccines (a) after reading Tier 1 “COVID-19 vaccines: key facts” and (b) after reading Tier 2 “COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring” by stakeholder groups at EU and regional level.

Table 5.

Willingness to get vaccinated with COVID-19 vaccines (a) after reading Tier 1 “COVID-19 vaccines: key facts” and (b) after reading Tier 2 “COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring” by stakeholder groups at EU and regional level.

| a |

Stakeholders group |

Willingness did not change |

Willingness increased |

Willingness increased |

| EU-level |

Individual patient/consumer (n=6) |

3 (50%) |

1 (17%) |

2 (33%) |

| Individual HCP (n=3) |

2 (67%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (33%) |

| PCO (n=8) |

5 (63%) |

2 (25%) |

1 (13%) |

| HCPO (n=13) |

10 (77%) |

0 (0%) |

3 (23%) |

| Regional level |

Individual patient/consumer (n=7) |

5 (71%) |

1 (14%) |

1 (14%) |

| Individual HCP (n=12) |

11 (92%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (8%) |

| PCO (n=3) |

3 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

| HCPO (n=8) |

8 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

| b |

Stakeholders group |

Willingness did not change |

Willingness increased |

Willingness increased |

| EU-level |

Individual patient/consumer (n=2) |

1 (50%) |

1 (50%) |

0 (0%) |

| Individual HCP (n=2) |

1 (50%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (50%) |

| PCO (n=8) |

5 (63%) |

2 (25%) |

1 (12%) |

| HCPO (n=11) |

8 (74%) |

3 (27%) |

0 (0%) |

| Regional level |

Individual patient/consumer (n=5) |

4 (80%) |

1 (20%) |

1 (20%) |

| Individual HCP (n=11) |

10 (91%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (9%) |

| PCO (n=0) |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| HCPO (n=7) |

7 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

Table 6.

Recommendatios for improvement of EMA materials after finalisation of EU-level survey.

Table 6.

Recommendatios for improvement of EMA materials after finalisation of EU-level survey.

| Improvement identified by stakeholder |

Recommendation for EMA |

| Replace visual on positive benefit-risk balance |

EMA replaced the visual in all its materials by the one preferred by stakeholders |

| Improve key messages and more friendly-language |

Update text and section headings |

| Prepare more succinct materials |

* Make available on EMA’s website the recordings and presentations of EMA’s public stakeholder meetings, which summarise all information on COVID-19 vaccines |

| Produce more information on vaccine safety |

Prepared a dedicated webpage on COVID-19 vaccine safety: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/public-health-threats/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/treatments-vaccines/vaccines-covid-19/safety-covid-19-vaccinesContinue to make available on EMA’s website dedicated safety updates for each approved COVID-19 vaccine, in addition to all information on safety routinely published for each vaccine (safety communications and summaries of scientific assessments) |

| Produce more friendly (audio)visual materials |

In addition to (*), produce infographics, social media campaigns |

| Keep information updated |

Keep EMA’s webpages on COVID-19 vaccines regularly updated |

| Translations into official EU languages |

Explore translating key information on COVID-19 vaccines into official EU languages |