1. Introduction

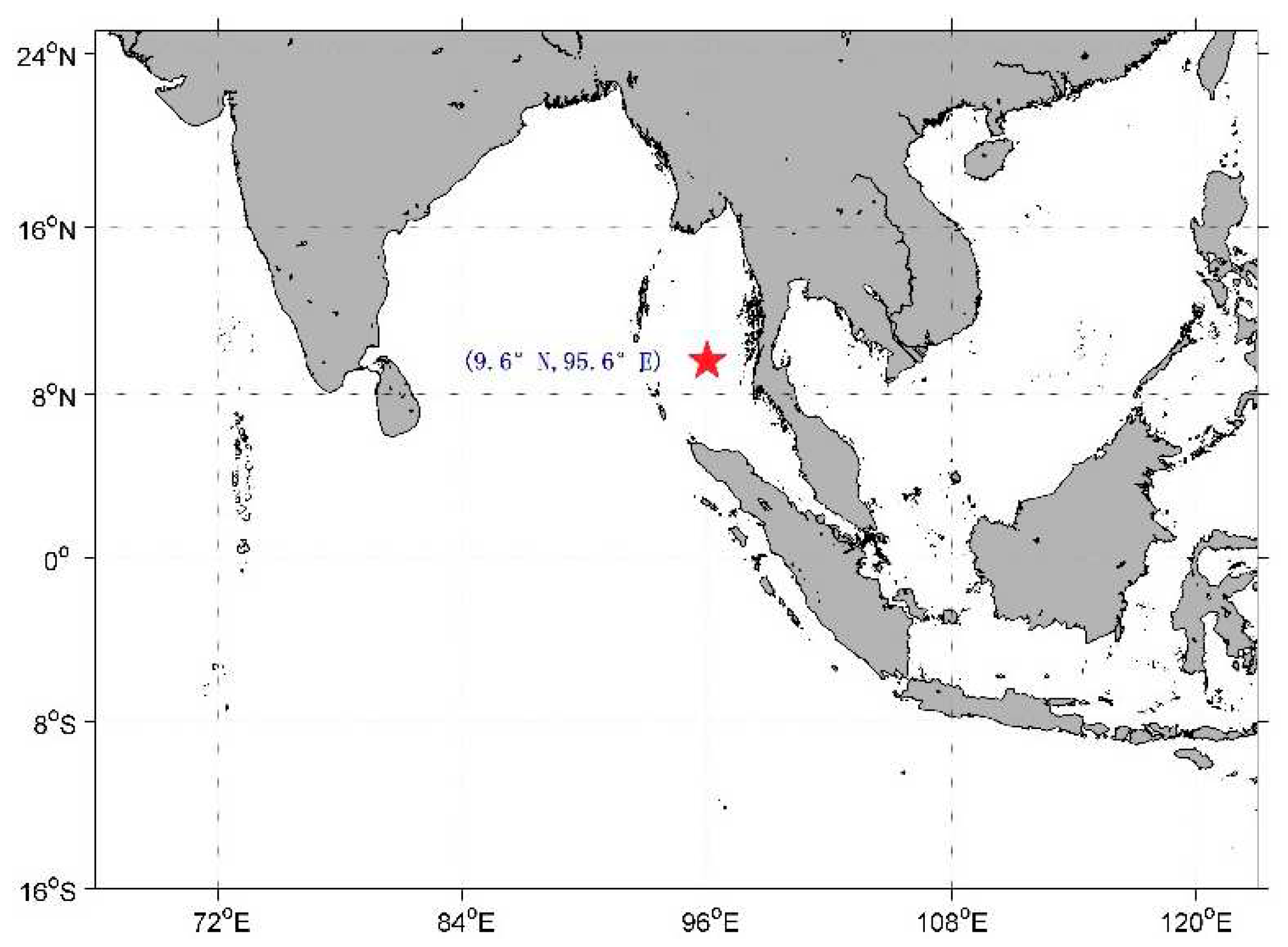

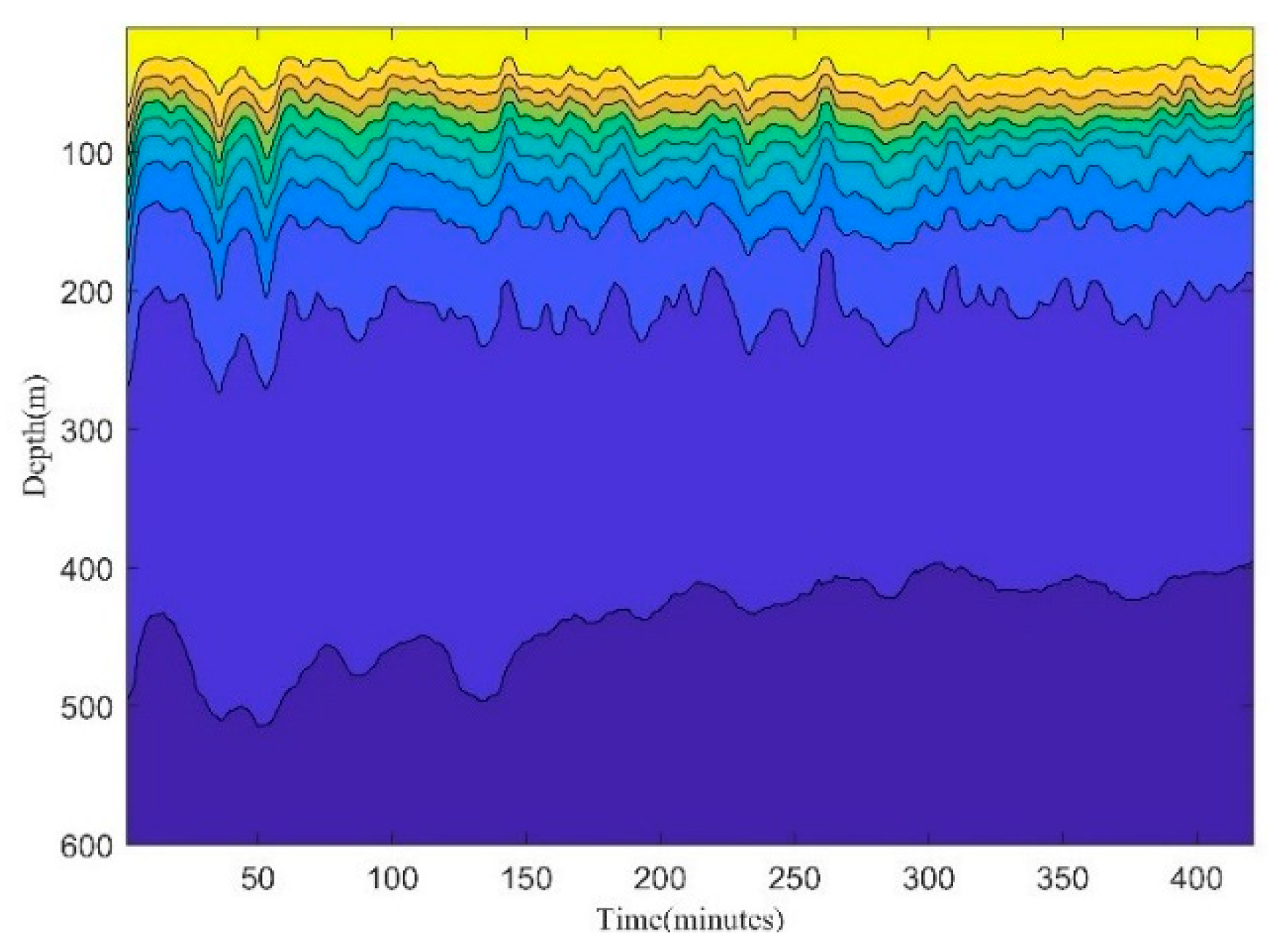

Internal waves are an ocean phenomenon with short periods and large amplitudes that can usually reach tens to hundreds of meters [

1]. Internal waves have been observed in many sea areas [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Internal waves usually occur in the deep ocean and can change the thermohaline structure of seawater by affecting the vertical mixing of seawater, which is an important link in the transfer of large-scale and mesoscale motion energy [

9,

10]. The impact of internal waves on marine ecosystems is also important. One important impact is that on the supply of nutrients in the upper ocean [

11], which is of great significance for ocean productivity and the construction of food chains. In addition, internal waves can also affect the suspension and reaccumulation of seabed sediments, as well as the distribution and transformation of biological and chemical substances in the seabed [

12]. Internal waves also affect the species composition, community structure and productivity of some marine ecosystems. Internal waves are also closely related to ocean utilization and maritime activities. Internal waves can affect the navigation of underwater vehicles and the operation of offshore drilling platforms [

13] and may also affect the dynamic response of offshore platforms. Therefore, understanding the characteristics and distribution of internal waves and studying their impact on the ocean and the environment are of great significance for understanding the ocean, protecting the environment and improving disaster prevention and reduction.

At present, internal wave recognition methods based on satellite remote sensing images [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] and ocean profile data are commonly used [

19,

20,

21]. The satellite remote sensing image method can be used to recognize internal waves by observing irregular light and dark fringes in images. With the rapid development of artificial intelligence, some scholars have carried out research on automatic internal wave recognition algorithms based on satellite remote sensing images. Celona S et al. [

16] used X-band radar to collect remote sensing images and a machine learning algorithm of a support vector machine (SVM) model to classify whether the images contained internal solitary waves or tidal internal waves, realizing the automatic detection and classification of internal waves. Bao S et al. [

17] used the target detection method to realize the internal wave automatic recognition method based on SAR remote sensing images. However, the observation range of satellite remote sensing images is usually large, and the satellite orbit is constantly changing, so it is impossible to observe specific areas for a long time. In addition, the observation of satellite remote sensing images is affected by natural factors such as weather and clouds [

18], which will also affect the identification and observation of internal waves. and the characteristics of internal waves are easily confused with other features in remote sensing images (vortex, ship wake, wind, waves, etc.) [

17].

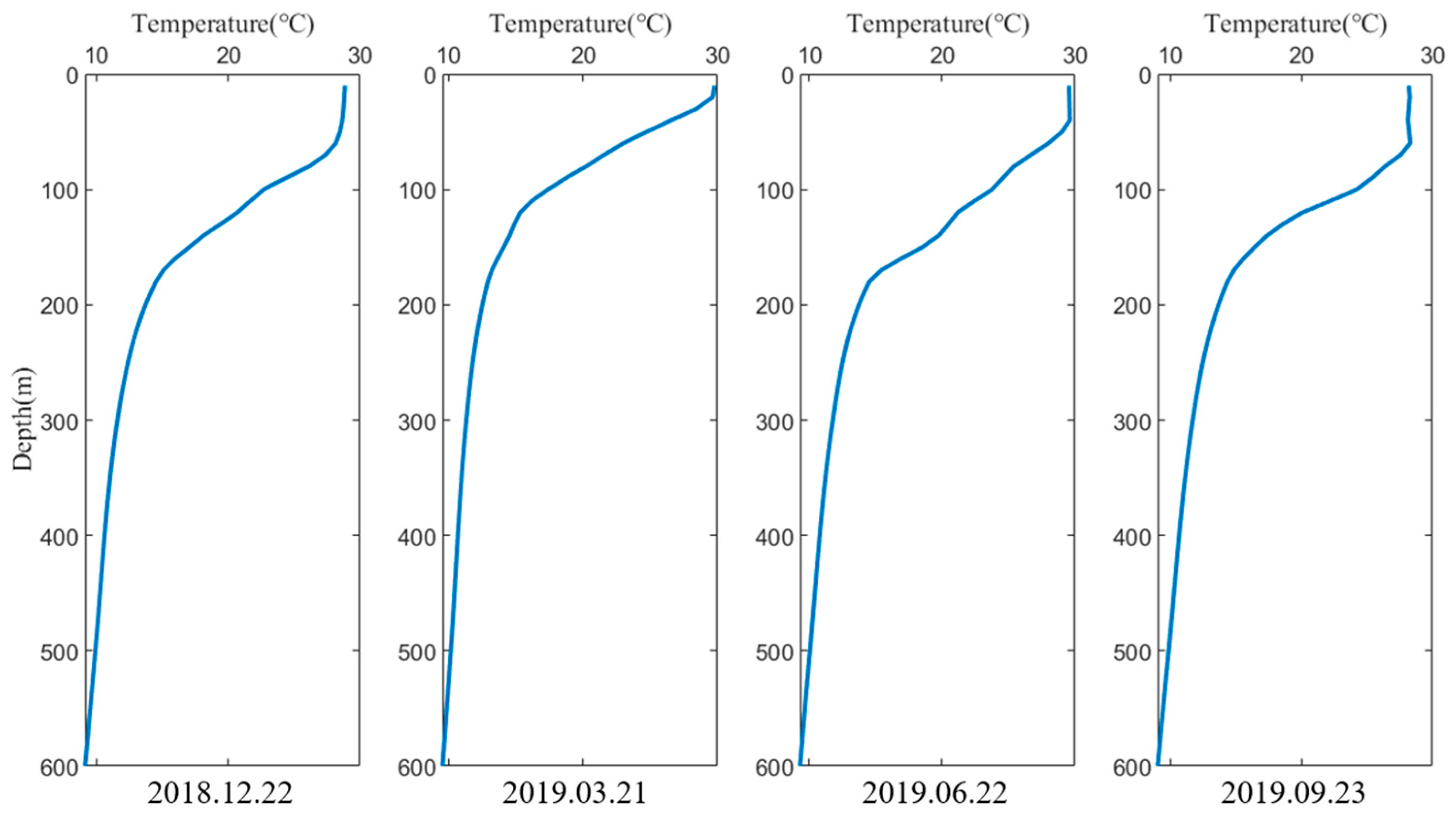

In recent years, some scholars have performed related research on internal wave recognition based on ocean profile data. Zhang B et al. [

19], using the physical process of internal waves driving water particles to fluctuate up and down, proposed a method for calculating the amplitude of internal waves. The feasibility of this method was verified using data collected by a temperature chain installed on a moored buoy. However, this algorithm cannot automatically locate the position of internal waves and cannot be directly applied to automatically identify internal waves at the end of the moored buoy. Suanda S H et al. [

20] used a buoy equipped with a thermistor to collect offshore ocean temperature profile data for a month, and the collected temperature data were filtered by differential filtering. Then, the filtered data were compared with threshold values, and values greater than the standard threshold value were judged to be internal waves. Liu B et al. [

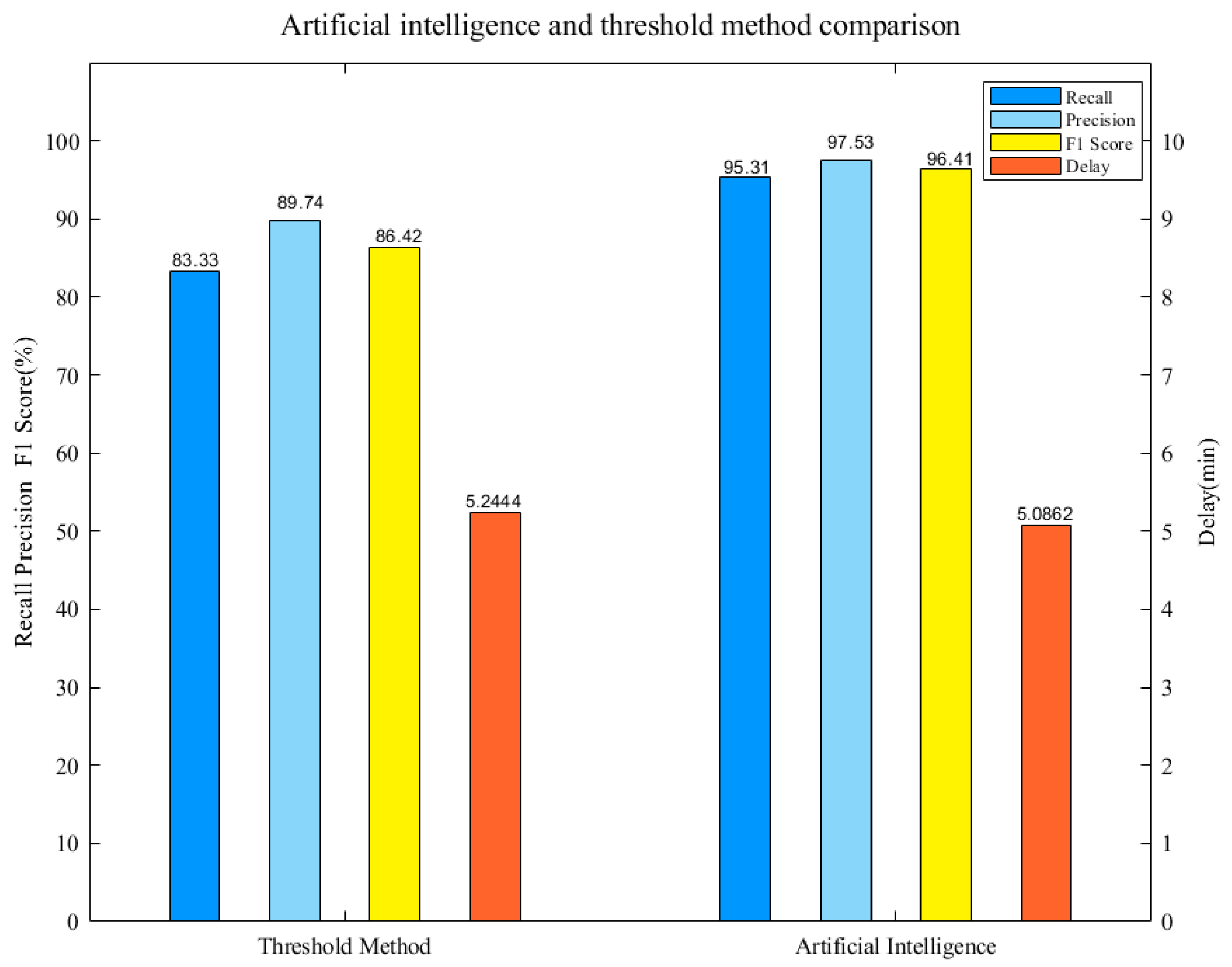

21] proposed a method of measuring internal waves based on a mobile temperature chain real-time monitoring system that was independently designed to perform the mobile real-time monitoring of internal waves, and the method was tested on a monitoring ship. However, through experimental verification, this study found that the recognition effect of the threshold method was not excellent: the recall was 83.33%, the precision was 89.74%, and the delay was 5.2444 minutes.

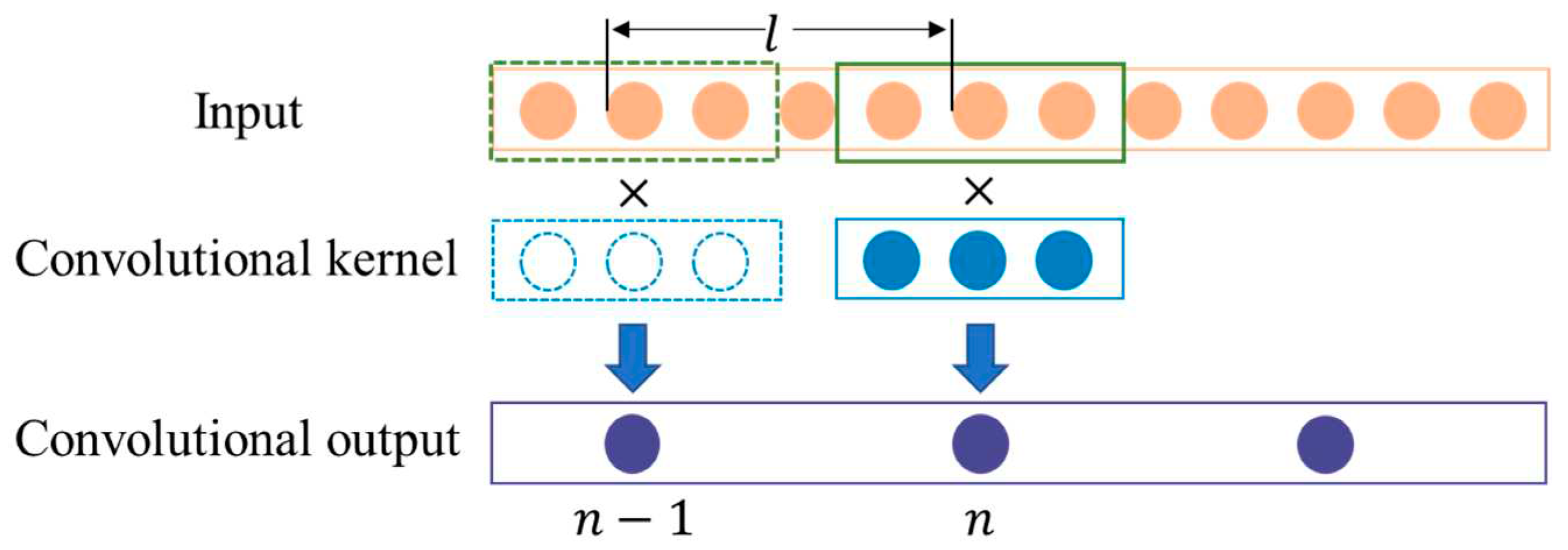

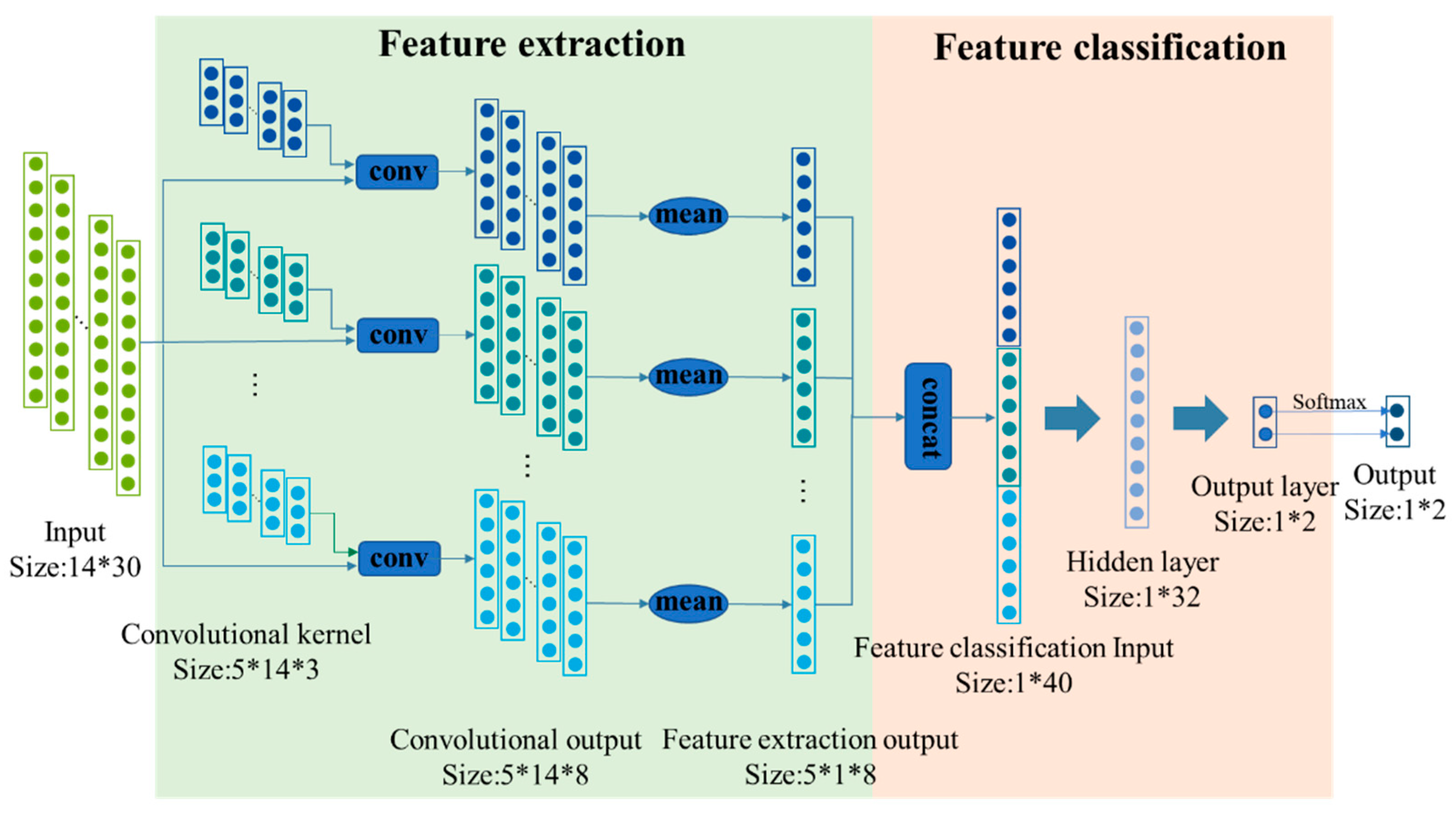

Deploying the internal wave recognition algorithm to the ocean data buoy system can allo researchers to improve the efficiency of data processing and analysis, reduce the cost of data transmission and processing, improve the real-time performance of observation data, and flexibly respond to different observation situations. However, none of the above methods [

19,

20,

21] can meet the needs of accurate and automatic identification of internal waves in ocean data buoy systems. To solve this problem, an automatic internal wave recognition algorithm for tight buoy ends is designed in this paper. The algorithm can be directly deployed to the end of the buoy. By processing and analyzing the ocean profile temperature data collected by the buoy, the internal wave sign is extracted, and internal wave recognition is carried out by combining the neural network. The algorithm has the characteristics of real-time performance, high reliability and automation and can meet the needs of internal wave recognition of intelligent buoys. In addition, considering the high energy consumption requirement of the buoy end, the algorithm can improve the feature extraction efficiency, reduce the number of parameters and calculation amount of the algorithm, and reduce the energy consumption of the buoy end by selecting a suitable number of convolution kernels and convolution interval.

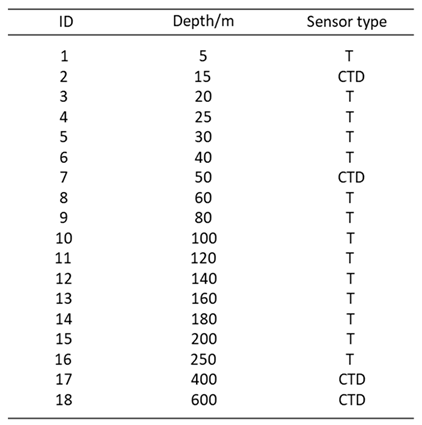

3. Experimental preparation

3.1. Experimental evaluation

In this paper, recall (formula 7), precision (formula 8), F1 Score (formula 9) and delay (formula 10) are used as metrics of the internal wave recognition algorithm. Recall is used to measure the model's ability to identify internal waves. Precision is used to measure the accuracy of model recognition of internal waves. Generally, recall and precision are expected to both be high, but in some cases, the two indicators are contradictory. Therefore, the F1 score is used to reconcile recall and precision. In addition, the difference between the time when internal waves are recognized and the start time when internal waves are marked is defined as the delay. As shown in

Table 2, the presence of internal waves is defined as a positive object, while the absence of internal waves is defined as a negative object.

In the formula, indicates the number of samples that are correctly classified as having internal waves, indicates the number of samples that are correctly classified as having no internal waves, and indicates the number of samples that are incorrectly classified as having internal waves. represents the number of samples incorrectly classified as nonexistent internal waves. represents the internal wave identified position, and represents the internal wave start position marked in the data set.

In addition, to explore the effectiveness of the feature extraction network, in addition to the above evaluation indicators of the algorithm, this paper also compares the data correlation and the number of features (N) before and after feature extraction. Finally, to study the practicability of the algorithm, we calculate the storage cost and computing cost using different model structures, in which the storage cost is measured by the model parameter number (Parameters) index, and the computing cost is measured by the floating-point number (FLOPs) index.

3.2. Experimental environment

In this study, all the experimental code source code is Python, using the PyTorch neural network architecture; the software installation version is Python 3.8.10, torch 1.11.1, cuda11.3. The computing unit uses an RTX2080Ti graphics card with 11 GB video memory and 40 GB RAM.

4. Verification algorithm

4.1. Reliability verification

To compare the artificial intelligence method with the threshold method [

19,

20], the threshold method used in this study uses the same test set as the artificial intelligence method to identify internal waves. The threshold method determines the range of temperature changes within 30 minutes by setting a threshold (θ) to determine whether there is an internal wave. The effects of different thresholds on the experiment are shown in

Table 3.

When the threshold recognition internal wave method is set at 2.5, the recall rate is close to 100%, but the precision is close to 45.49%. As increases, recall decreases sharply, precision increases sharply, and delay becomes longer. When , the precision is 97.65%, but the corresponding recall is only 65.87%, and the delay reaches 8.2759 minutes. Therefore, the threshold method cannot balance the relationship between recall and precision, and the reliability of the algorithm cannot be guaranteed in practical applications.

Compared with the threshold method, the recognition effect of the artificial intelligence method has been significantly improved, as shown in

Figure 8. The feature extraction network can extract and strengthen the internal wave signs and delete irrelevant features. The feature recognition network is trained to fit the internal wave sign through historical data, which takes more internal wave sign elements into consideration and has a better recognition effect than the threshold method neural network. From the experimental results, the recall reaches 95.31% precision, and the 97.53% Magi delay drops to 5.0862 minutes; therefore, while precision is improved, recall is kept at a high level, which greatly improves the reliability of the algorithm in practical applications.

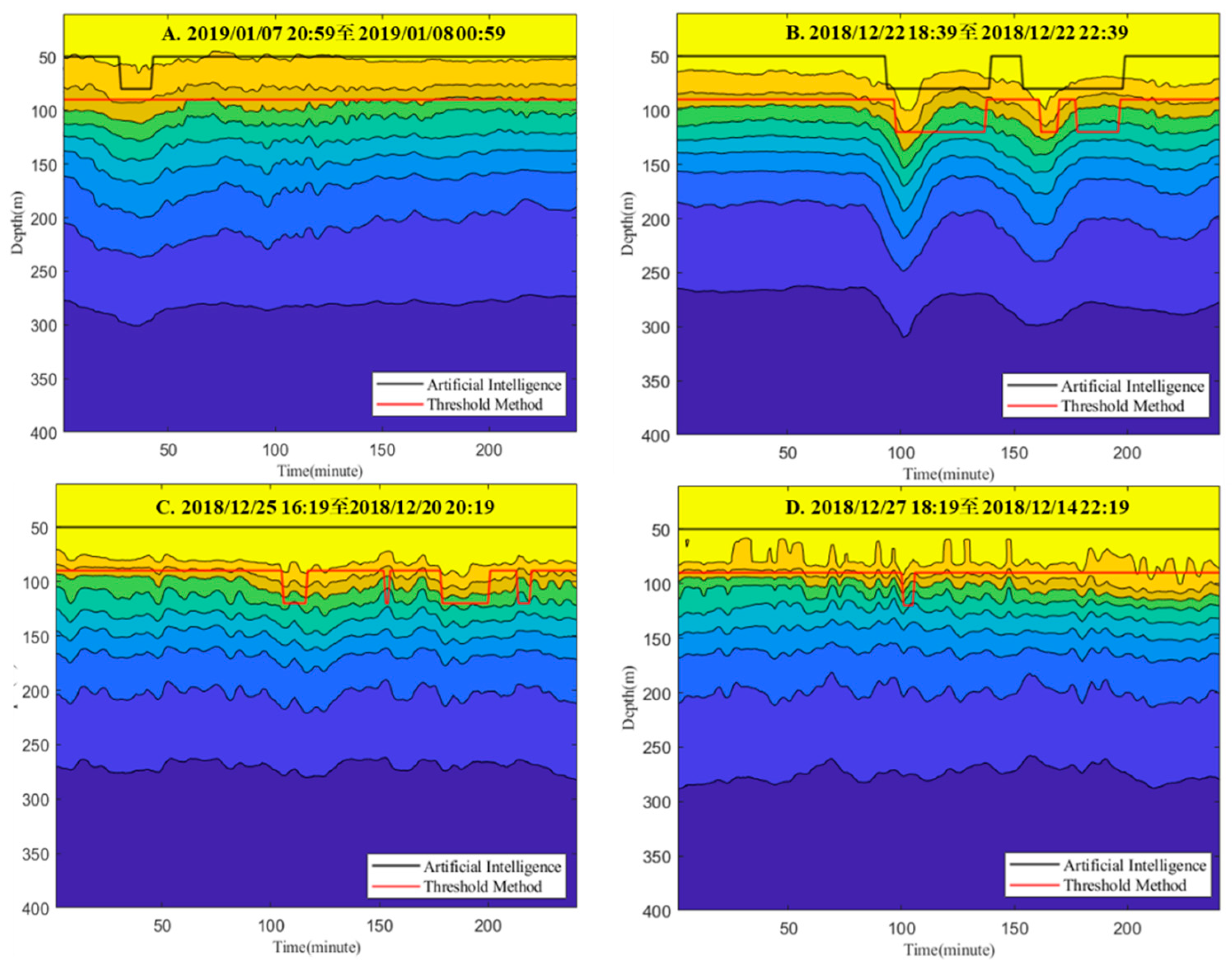

To further verify the reliability of the artificial intelligence algorithm used in this paper, the artificial intelligence algorithm and threshold method are compared with the actual internal wave temperature vertical structure observation data, in which it is specified that the period when internal waves are recognized is a low state, and the period when internal waves are not recognized is a high state. The comparison results are shown in

Figure 9. Compared with the threshold method, the artificial intelligence method can identify more internal waves, as shown in Fig. 9(A) and Fig. 9(B). Due to the slow temperature change rate, the threshold method cannot identify these internal waves. In addition, the artificial intelligence method has fewer misidentification phenomena, as shown in Fig. 9(C) and Fig. 9(D). The threshold method has misidentification phenomena, which is caused by the fact that although the temperature in the misidentification period tends to rise or fall, it is not enough to define this period as an internal wave period. Artificial intelligence algorithms can improve the accuracy and reliability of internal wave recognition by extracting and identifying internal wave signs.

4.2. Validity verification of the feature extraction network

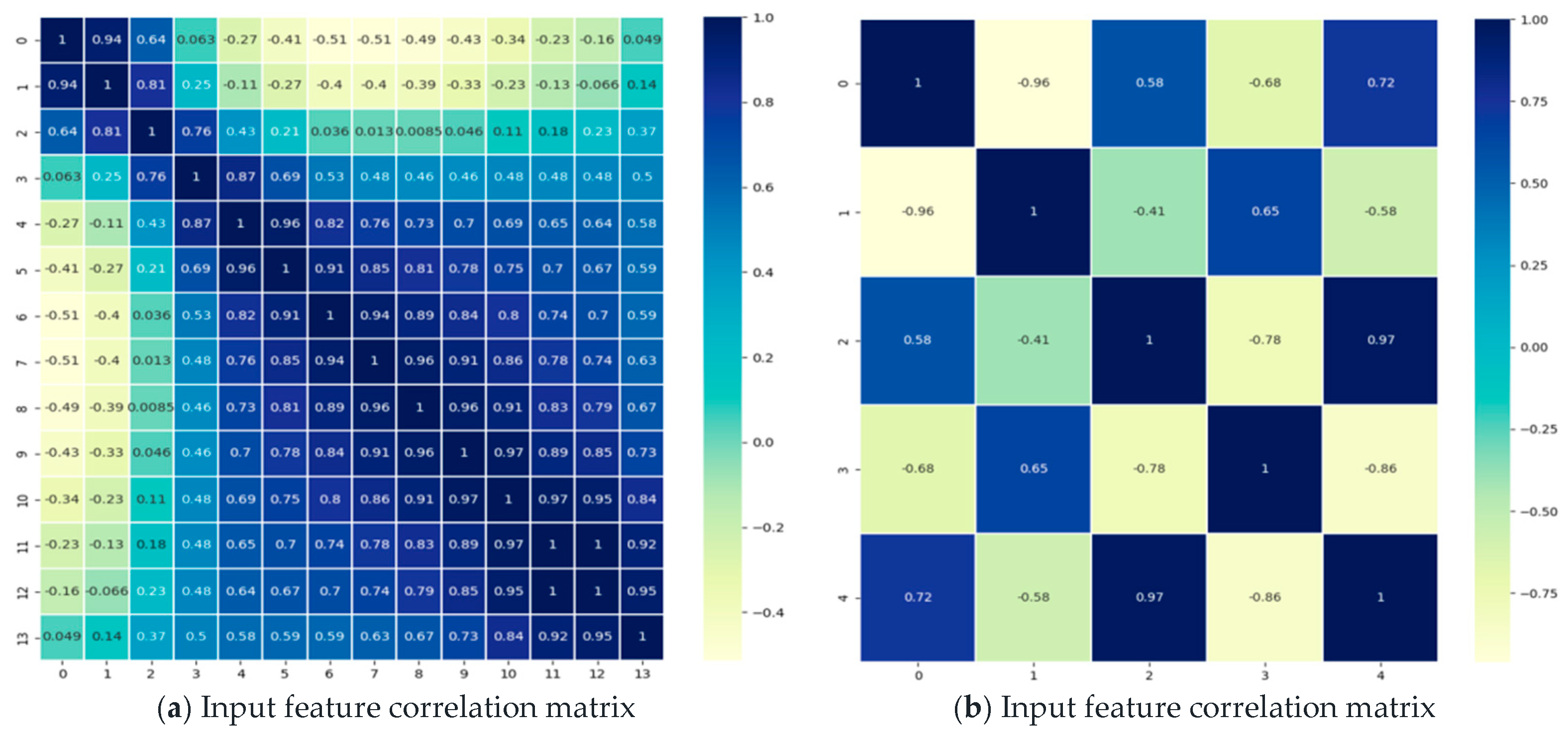

In this paper, by adjusting the convolution stride and the number of convolution kernels of the feature extraction network, the effectiveness of features is improved in the time dimension and space dimension, respectively. The internal wave recognition effect is the best when the convolution stride is 4 and the number of convolution kernels is 5. The feature extraction network has 420 input features and 40 output features, and the efficiency of feature extraction can reach 90.48%. The correlation matrix between the input and output data of the feature extraction network is shown in

Figure 10. The correlations between the original data can be reduced through the feature extraction network.

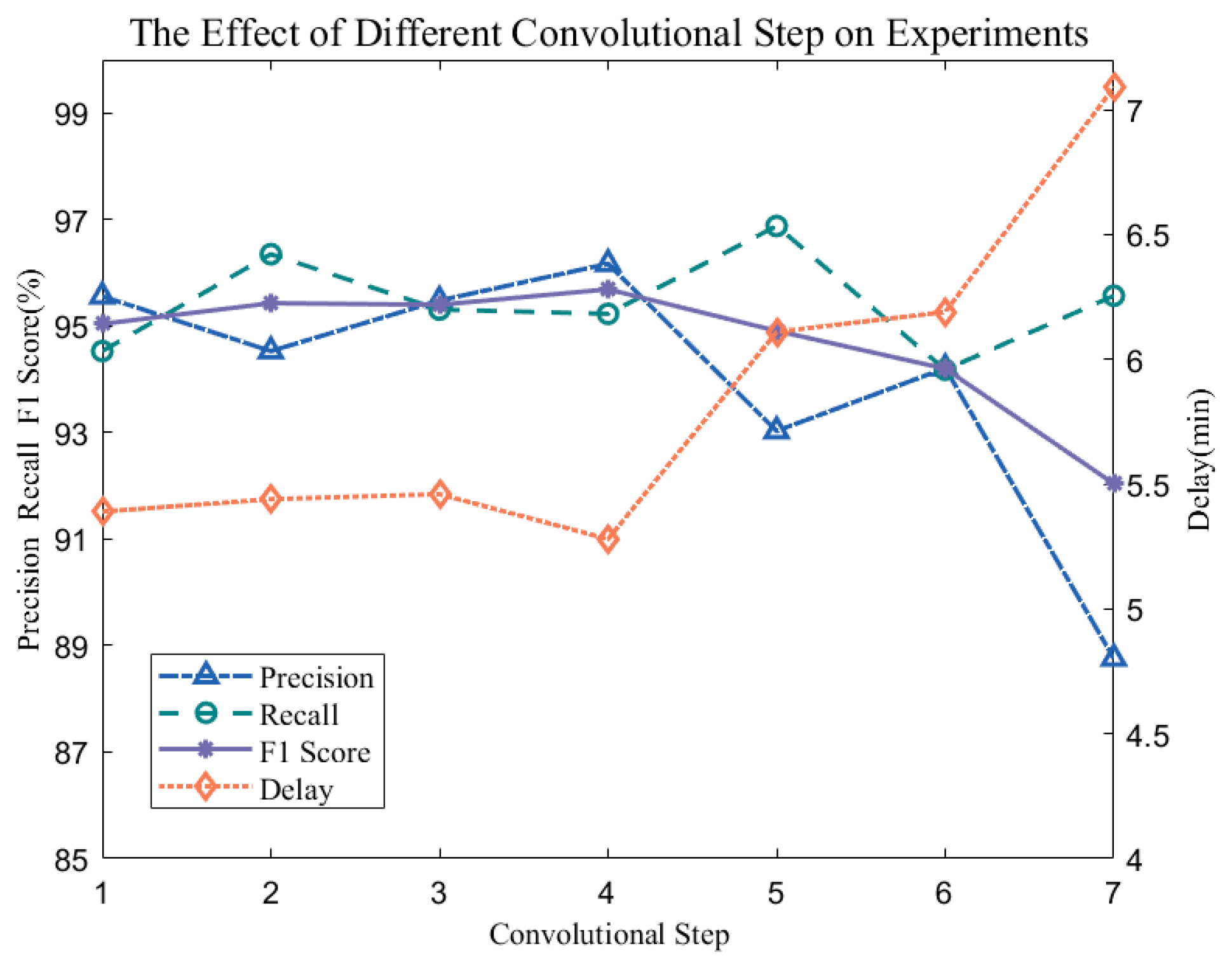

4.2.1. Sampling step selection of convolution operation

To compare the effects of sampling steps of different convolution operations on the experiment, this study compares the effects of convolution steps from 1 to 7 on the results of internal wave recognition.

Figure 11 shows that when the convolution step amplitude changes from 1 to 4, the changes in recall, precision, F1 Score and delay are not obvious, but when the stride continues to increase, F1 Score will have a significant downward trend, and delay will have an obvious prolongation trend because the collected underwater temperature profile series is a continuously collected time series, and increasing the sampling interval by properly increasing the convolution step has little effect on the final internal wave recognition results. However, when the convolution step is raised to 5, the internal wave recognition has an obvious downward trend, so this method selects a convolution step of 4 to sample the sequence, and when the number of convolution cores is 8, the output feature number is 64, as shown in

Table 4.

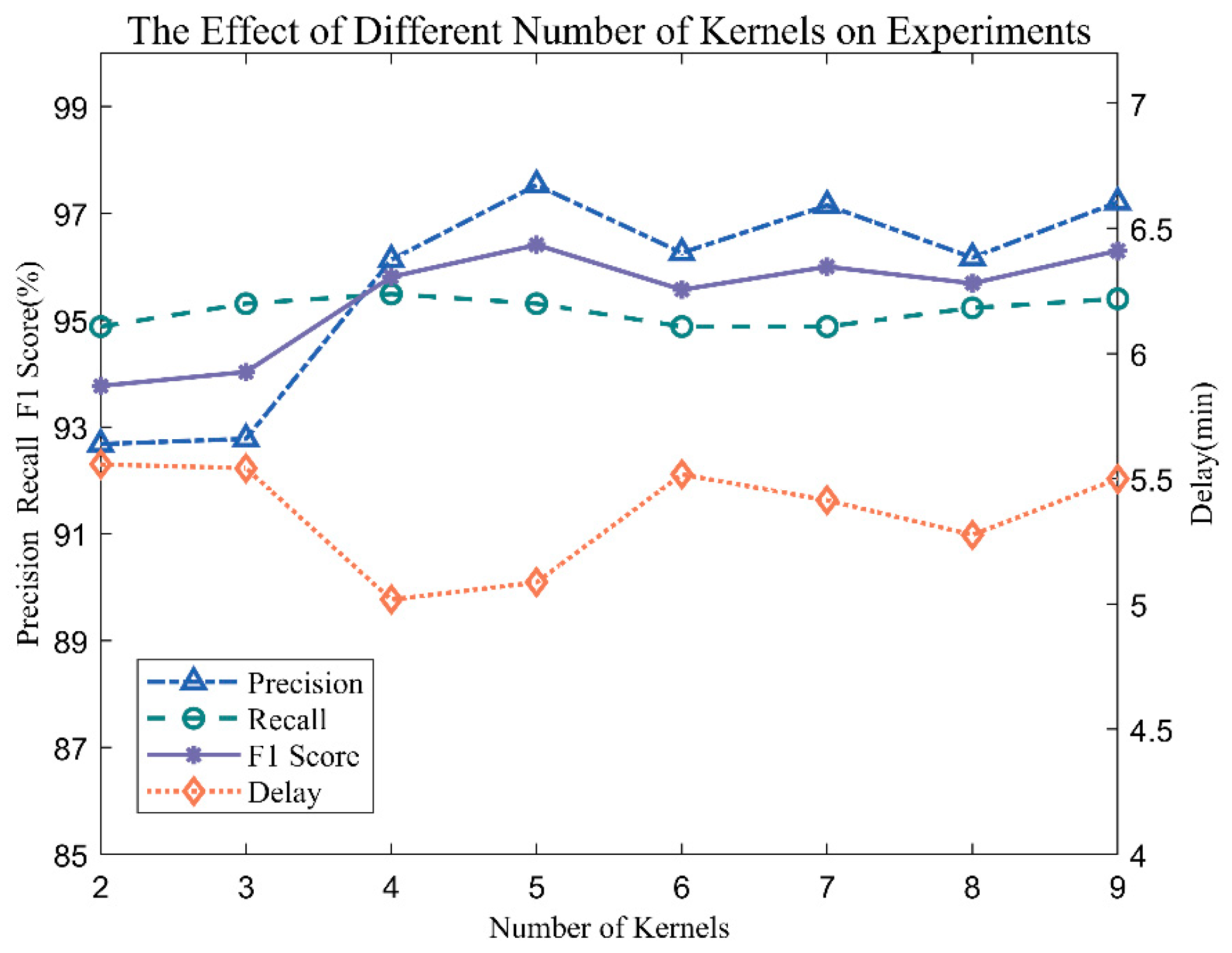

4.2.2. Selection of the number of convolution kernels

To reduce the spatial information redundancy of the input data, this paper selects the appropriate number of convolution kernels to obtain more effective spatial features for internal wave recognition. The number of convolution kernels selected in the experiment is 1-9. When the number of convolution kernels is 1, it is found that the algorithm does not converge, and when the convolution kernel is 2-9, the experimental results are shown in

Figure 12. When the number of convolution kernels increases from 2 to 3, the recognition effect of the algorithm is not obvious. When the number of convolution kernels is increased from 3 to 5, the recognition effect of the algorithm is significantly improved. When the number of convolution kernels is raised from 5 to 9, it is found that the internal wave recognition effect is not improved, so the final number of convolution kernels selected by this algorithm is 5, and the number of output features is 40 when the convolution step is 4, as shown in

Table 5.

4.3. Practical verification

By comparing the recognition results of different network structures, the one-layer convolutional neural network plus fully connected internal wave recognition network used in this paper has the best result.

Figure 13 shows the precision-recall curve of various methods, in which the precision-recall curve of this method is significantly higher than that of other network structures. As shown in

Table 6, the effect of internal wave recognition is significantly improved after adding the feature extraction network, and the effect of the feature extraction network using one-dimensional convolution is also better than that of other feature extraction networks. This method has an F1 score that is 3.4% higher than that of the F1 score without the feature extraction network structure. The delay has been shortened by 1.22 minutes, and compared with the two-layer CNN and three-layer CNN feature extraction network structure, the F1 score has been improved by 2.46% and 2.14%, respectively, and the delay is shorter by 0.53 min and 1.09 min, respectively,. The delay is shorter by 0.5 min compared with LSTM and the F1 Score is increased by 2.12%.

In terms of the calculation of the number of network parameters, because this method reduces the input features of the feature recognition network by selecting the appropriate convolution steps and the number of convolution kernels, the number of parameters and computation of the algorithm are greatly reduced. As shown in

Table 7, the number of parameters and the amount of calculation of this method are 1593 and 3024, respectively. Compared with the direct feature recognition method, the number of parameters is reduced by 88.2%, and the amount of calculation is reduced by 77.66%.

According to the analysis of the recognition effect of the algorithm, the number of parameters and the amount of calculation, the algorithm has a good recognition effect, fewer parameters and less calculation. The parameters and FLOPs of the algorithm are 1593 and 3024, respectively, so it requires very low storage capacity and computing power of the equipment. The algorithm can be directly deployed in the controller of the intelligent buoy to meet the needs of automatic recognition of internal waves at the buoy end.