1. Introduction

Chitosan is a chitin derivative consisting of glucosamine (GlcN) and N-acetyl glucosamine (GlcNAc). In nature, there is more chitin than chitosan (found in the cell wall of the Zygomycetes). Some organisms of source chitin are bacteria and fungi, insects, microalgae, crustaceans, mollusks, and other aquatic commodities. The physicochemical characteristics of chitosan are a molecular weight of 10-1000 kDa, a degree of deacetylation is 50-95%, and it has acetamido and amino groups [

1]. Chitosan dissolves in acidic solutions such as acetic, lactic, formic, citric, and several other solvents. The solubility of chitosan can be increased in different solvents by modifying its chemical and molecular structure [

2]. This modification can be done through hydrolysis, producing chitosan oligosaccharides (COS) [

3].

COS is a homo or hetero-oligomer of GlcN and GlcNAc with glycosidic bonds [

3]. COS has a polymerization degree ≤ 20, molecular weight less than 3900 Da, high solubility, good water absorption and vital capacity, biocompatible, and others [

4,

5,

6]. COS production can be carried out chemically, enzymatically, physically, and electrochemically. Currently, the enzymatic method is most widely applied because the reaction proceeds under more gentle conditions, the COS molecular weight is more controlled, and it does not cause side products [

5,

6]. In addition, enzymatic production is the application of green technology that is environmentally friendly and sustainable.

Chitosan hydrolysis was carried out using the chitosanase enzyme, which belongs to the glycoside hydrolase group. Chitosanase can be produced from bacteria and fungi isolated from soil, marine sediments, and swamps. Chitosanase can also be extracted from fishery waste for application in COS production. Fishery waste contains protein in every part, but its utilization still needs to be improved and limited, such as fish meal, feed, fish oil, and others. Enzymes are proteins contained in fishery waste, for example, chitosanase, which is extracted directly or from microorganisms originating from fishery waste. However, applying chitosanase for COS production requires high costs, especially for the purification and hydrolysis of chitosan. The cost of producing COS can be reduced by using crude extracts. Chitosanase from

Bacillus mojavensis SY1 (CsnBm) is stable at pH 4-9 and temperature of 40-55⁰C. Its crude extract effectively produces COS with a DP of 1-6 at a concentration of 9 U/mL [

7]. Chitosanase crude extract from sea cucumber (

Stichopus japonicus) has an activity of 22.08 U (pH 6 and 45⁰C) capable of hydrolyzing chitosan into COS with a molecular weight of 1260 Da [

8]. These results indicate that the crude extract can be used to hydrolyze chitosan. However, a review of the production of crude chitosanase extract and its mechanisms for COS production is still limited. Based on this, the effectiveness of chitosanase crude extract needs to be discussed to develop the enzymatic production of COS.

In this review, we look at the production of chitosanase and COS. First, we will review the production of chitosanase crude extract starting from the source and the isolates produced—carbon and nitrogen (C/N) sources in production focusing on using fishery waste. Fishery waste is a good source of C/N, but different sources of waste will have different effects on the growth of microorganisms. Therefore, the optimization of C/N sources needs to be reviewed to find out the comparison. Characterizing the resulting chitosanase is very important to know for the needs of the hydrolysis process. We will also review COS production starting from the purity level, enzyme concentration, hydrolysis time, degree of deacetylation (DD) of chitosan, and the COS produced. This review is essential to know the effectiveness and mechanism of chitosanase crude extract. We will begin the review by discussing the sources of chitin, chitosan, and COS and their differences from chitin oligosaccharides. Then, our review will explain the isolation and production of chitosanase and the effectiveness and mechanism of the crude extract in hydrolyzing chitosan.

2. Methods

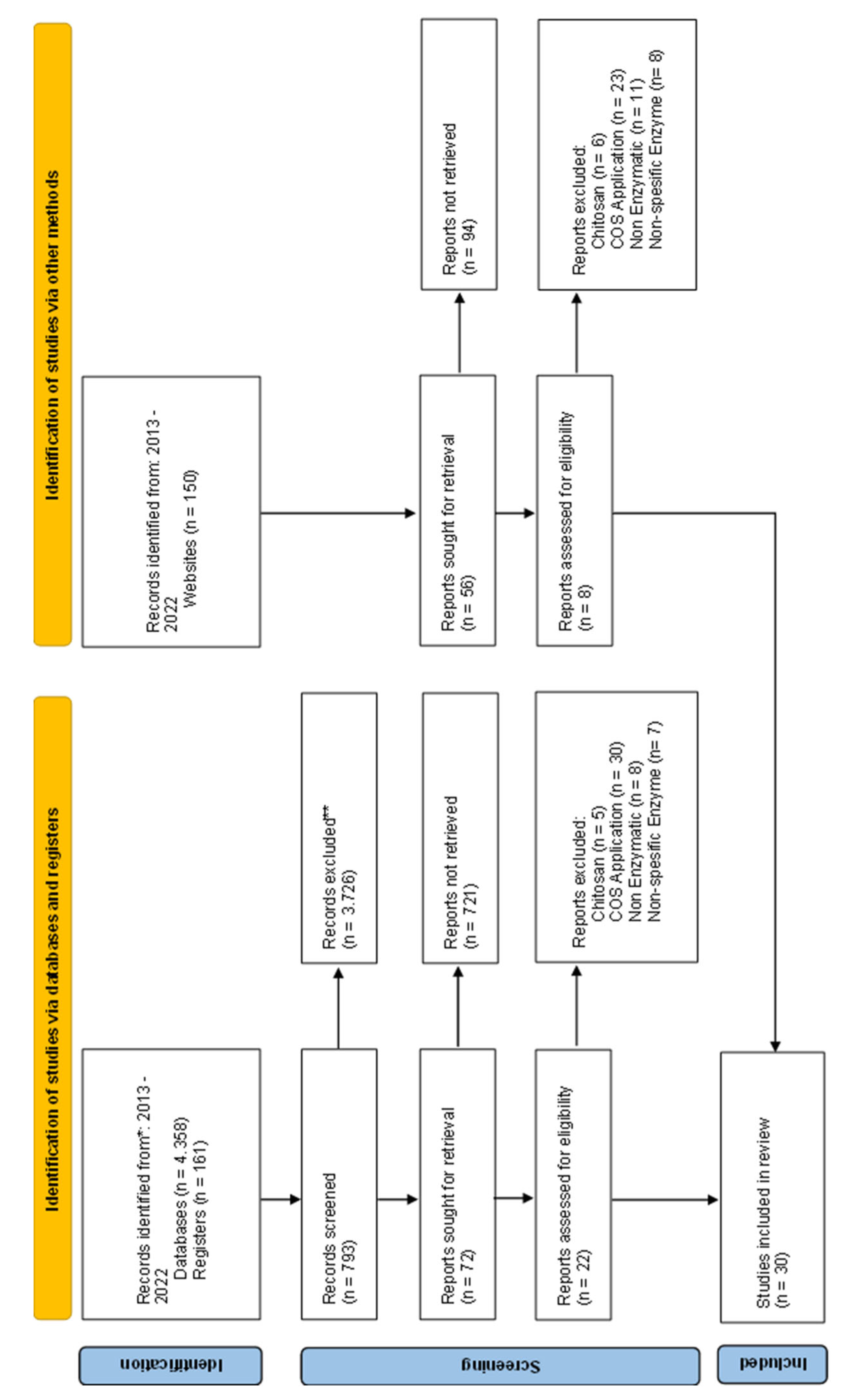

A literature search was performed on Science Direct, Pubmed, Springer, SAGE, and Nature databases. The search focused on four keywords, namely "chitoooligosaccharides," "chitosanase," "production," and "enzyme." Search techniques are also performed using the "AND," "OR," or "NOT" operators. The stage of the literature search begins with restrictions on the year of publication; the articles taken from our research were conducted in the last ten years in the 2013-2022 range. In the next stage, the articles obtained are limited to the scope of the topics to be studied and will produce several articles. The article will then be reviewed based on the title, abstract, and the article as a whole so that eligible articles are obtained. A literature search flow chart based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) is presented in

Figure 1.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chitosan and Chitosan Oligosaccharides

3.1.1. Chitosan

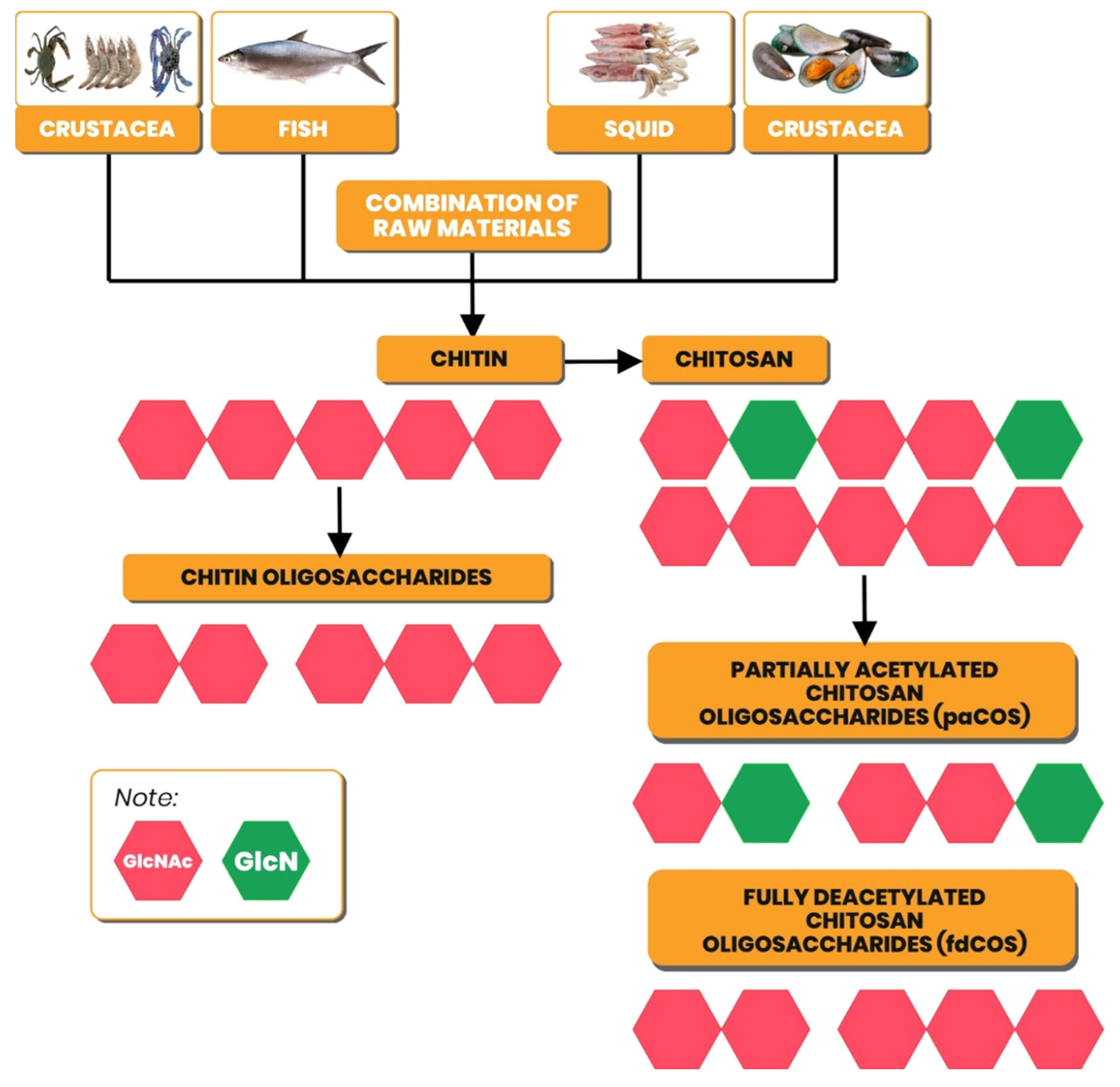

Currently, most of the sources of chitin used as raw material for chitosan production are fishery waste, such as shrimp, crabs and crabs, squid, clams, and fish (

Figure 2). The chitin content in shrimp reaches 30-40%, green mussels <3%, crabs and crabs 15-30%, and squid 20-40% [

9,

10]. It is the primary consideration for getting chitosan according to the grade and large amount. The availability of raw materials also needs to be reviewed if chitosan is to be produced on an industrial scale. Using fishery waste in chitosan is one of the solutions to overcome environmental problems, especially in the fishing industry.

The raw materials widely used to manufacture chitosan in the last ten years are squid pens and shrimp shells. Squid pen contains low minerals such as Ca, K, Na, Mg, and Cl, so the demineralization process is not carried out [

11,

12]. Chitosan from squid pen (

Loligo formosa) has a molecular weight of 150 kDa with a yield of 54% [

11]. Squid pen with low minerals produces chitosan according to standards, and the energy required in the manufacturing process is lower because there is no demineralization process. The squid pen's content allows chitosan production to be carried out enzymatically by breaking down the protein and acetyl groups in chitin.

Shrimp waste is different from squid pen in that waste there are organs other than shells. Shrimp commodity produces waste in the form of cephalothorax and shell; if cleaned, it will produce carapace. Shell waste produces 3.12 more chitosan than cephalothorax because other organs exist, such as antennae, pereopods, maxillipeds, and others [

13]. The shell part is better in quality and quantity in producing chitin and chitosan, for example, in

Penaeus kerathurus shell waste. The waste contains 19.5 ± 0.5% chitin and produces chitosan with a DD of 92.4 ± 0.5% [

14].

The content of fishery waste needs to be known to facilitate the chitosan production process. For example, green mussel shells contain CaCO

3, MgCO

3, (Al, Fe)

2O

3, SiO

2, Ca

3P

2O

8, CaSO

4, proteins, polysaccharides, and others. Crustacean shells also contain CaCO

3 and protein in smaller amounts but contain more chitin [

9,

15]. The production of chitosan from green mussels can be carried out, but the extraction process requires much energy, and the grade is lower than that of other raw materials. The grade of chitosan can be increased by combining it with other raw materials.

Figure 2 shows that the raw material for chitosan production can be obtained from fish waste, namely the scales. Fish scales consist of organic and inorganic components. Organic components (40-55%) include collagen, fat, vitamins, scleroprotein, lecithin, and others. Inorganic components (7-25%) include hydroxyapatite and calcium phosphate [

16]. Fish scales also contain chitin which is found in goblet cells (on the periphery) and club cells (distributed throughout) [

17]. Chitosan from

Labeo rohita fish scales has a molecular weight of 5,201 Da and DD 75%; the product has characteristics like chitosan from

Crangon crangon [

18]. Other research results show that chitosan from tilapia scales has a DD of 92.23%, a molecular weight of 11.58 kDa, and a solubility of up to 78.65% [

19]. Fish scales can be used as an alternative raw material for chitosan, but it is necessary to facilitate the production process, especially collagen associated with chitin [

20]. The breakdown of chitin from collagen can be done through hot water pre-treatment [

21].

3.1.2. Chitosan Oligosaccharide

Chitooligosaccharides are products of the degradation of chitin and chitosan consisting of GlcN and GlcNAc with β-(1-4) glycosidic bonds. These products have different acetylation fractions (FA) and GlcN/GlcNAc sequences. If the product consists only of GlcN or GlcNAc, then it is a homochitooligosaccharide, while the product consisting of GlcN and GlcNAc is called a heterochitooligosaccharide [

2]. Chitin hydrolysis produces oligosaccharide chitin, a homochitooligosaccharide, because it only consists of GlcNAc and is classified as a fully acetylated chitooligosaccharide (faCOS) group. The product of chitosan hydrolysis consists of only GlcN or GlcN and GlcNAc (homo/hetero-oligosaccharide), which are classified as fully deacetylated chitooligosaccharide (fdCOS) or partially acetylated chitooligosaccharide (paCOS) group.

The production of environmentally friendly COS with standard-compliant products is carried out enzymatically. Sources of enzymes that can be used are fishery waste and chitinase or chitosanase-producing microorganisms. Enzymes from

Alternaria alternata can hydrolyze chitosan into paCOS; this enzyme is active in moderate DD chitosan by cleaving GlcN-GlcNAc [

22]. Deacetylated chitin from

Saccharomyces cerevisiae (scCDA2) is also effective in producing paCOS with DP 4 [

23]. These results indicate that the enzymatic production of COS can be carried out using specific and non-specific enzymes (chitosanase and chitinase). COS production can also occur in two stages: chemical hydrolysis and chitosanase. The COS produced includes fdCOS (63%) and can inhibit

Escherichia coli and

Listeria monocytogenes [

24]. COS production is affected by DD chitosan; for example, fdCOS is produced from the hydrolysis of chitosan (DD > 90%) with the neutralize enzyme, while paCOS are obtained through the hydrolysis of chitosan (DD 81-90%) with chitinase enzymes [

25].

Chitin and chitosan oligosaccharides (COS) have different physical and chemical characteristics (

Table 1). COS consists of three active functional groups, namely amino/acetyl at position C-2, primary hydroxyl, and secondary hydroxyl (C-2, C-3, and C-6). The functional group of the chitin oligosaccharide at the C-2 position is acetyl; this group distinguishes it from COS [

26]. The content of acetyl groups in chitin oligosaccharides causes a high degree of acetylation (DA). The deacetylation stage in COS production causes an increase in amino groups so that DA decreases. The solubility of COS in water is affected by the chain length and amino groups on GlcN, which are identified from the degree of polymerization (DP) and DA [

2,

27]. In contrast to COS, which is easily soluble in water, chitin oligosaccharide is water soluble at low DP (2-6); if> 6, it is difficult to dissolve, and its application is limited [

26].

3.2. Chitosanase

3.2.1. Source of Chitosanase

Chitosanase belongs to the glycoside hydrolase family, divided into three classes, and chitosan is the substrate. Class I can hydrolyze GlcNAc-GlcN and GlcN-GlcN, class II can only hydrolyze GlcN-GlcN, while class III can hydrolyze GlcN-GlcNAc and GlcN-GlcN [

5]. Chitosanase can be obtained from bacteria and fungi successfully isolated from soil, sediment, and fishery waste (

Table 2). Soil microorganisms have chitinase and chitosanase activities, which act as biocontrol agents for plant diseases and defense against vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal infections in roots [

28,

29]. Ecological diversity contains different numbers and types of microorganisms, including chitosanase producers. For example, 46 isolates were reported to have chitosanase activity isolated from the soil around fish waste [

30].

Fishery waste in the form of shrimp shells can be used as a source of chitosanase-producing microorganism isolates.

Providencia stuartii was successfully isolated from the shell of

Penaeus monodon and had the highest chitosanolitic activity compared to 16 other isolates [

47].

Table 2 shows that chitosanase can be produced directly from fishery waste as offal, such as snakehead fish (

Channa striata) and blue swimming crab (

Portunus segnis). The part used for the isolation of chitosanase is the digestive tract, especially those that are carnivorous. The enzyme is synthesized in the glandular tissue of the digestive system [

48].

3.2.2. Production Chitosanase

Chitosanase production can be carried out directly at the source, such as the offal of snakehead fish (

Channa striata) and blue swimming crab (

Portunus segnis). Chitosanase can also be produced from microorganisms isolated from soil, sediment, and fishery waste. Bacteria and fungi are types of chitosanase-producing microorganisms that have been isolated from their sources, especially soil.

Table 2 shows that screening for bacteria is carried out in less than seven days, faster than fungi (7-14 days). The difference in screening time occurs due to different growth patterns. The isolates obtained were optimized to determine the best production time under optimum conditions in producing chitosanase. Chitosanase-producing bacteria (

Table 2) experience an exponential phase for three days on average; after the third day of growth, they enter a stationary phase. Thus, chitosanase production is carried out for three days or more. Soil samples from eastern Taiwan were used to isolate TKU031, which has the potential to produce chitosanase enzymes. The isolates included gram-positive bacteria in the form of bacilli and were identified as

Bacillus cereus TKU031. B.

cereus was produced for five days (37

oC), and the highest chitosanase activity was on the second day (exponential phase) [

32].

Aspergillus fumigatus 11T-004 is a fungus that is produced for seven days, but this fungus can be harvested from the third day, to be exact, from the logarithmic phase to the sixth day (stationary phase). The highest chitosanase activity was 6 U/mL on the third day, and the activity value was relatively stable until the end of production [

36].

Penicillium janthelium D4 had the highest chitosanase activity compared to 34 Dak Lak, Vietnam isolates. P.

janthelium D4 began to be harvested after nine days with a chitosanase activity of 2.2 mU/mg [

31]. Chitosanase from bacteria and fungi belongs to the extracellular type obtained from the supernatant, which is separated from the biomass.

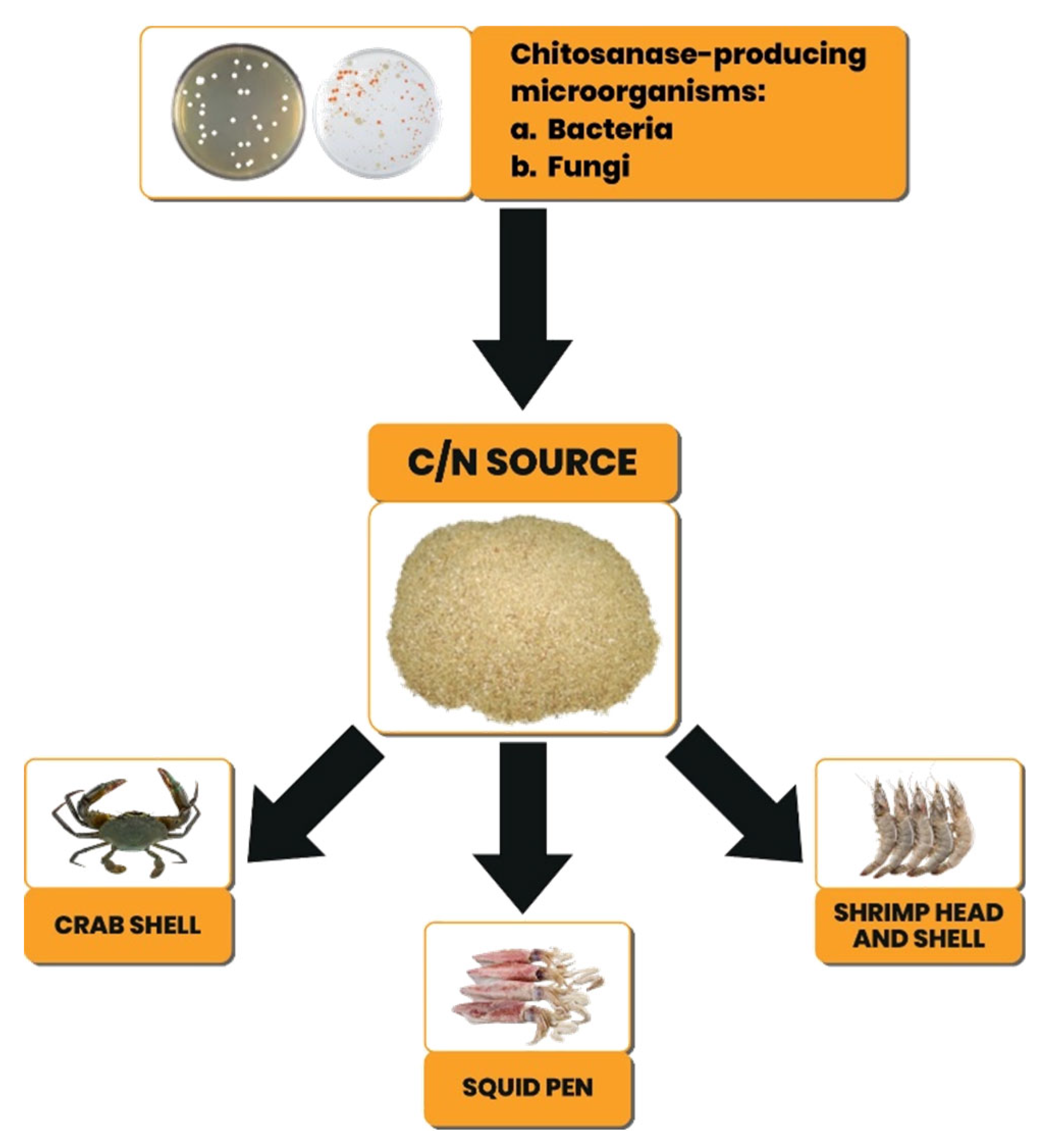

The production of chitosanase from microorganisms requires media, one of which is a source of carbon and nitrogen (C/N), which can be obtained from chitin. A practical source of C/N, unlimited availability, and low cost can be obtained from fishery waste such as shrimp heads and shells, crab shells, and squid pens (

Figure 3). Fishery waste contains proteins, lipids, minerals, enzymes, chitin, and other compounds according to the characteristics of the commodity. This content indicates that fishery waste can be used as a source of C/N for microorganism growth media.

Paenibacillus macerans TKU029 and

Paenibacillus sp. TKU047 has the highest activity in squid pen powder compared to other sources of chitin. Chitosanase activity of

Paenibacillus macerans TKU029 and

Paenibacillus sp. TKU047 in squid pen powder was 0.448 ± 0.022 U/mL and 0.35 ± 0.02 U/mL [

38,

41]. The chitin content in the culture media can encourage the synthesis of chitosanase by microorganisms. The ratio of chitin, protein, and minerals in the media also influences the synthesis and activity of chitosanase. Squid pen powder is a material from fisheries waste considered the best source of C/N [

39,

41]. It is due to the high chitin and low mineral content [

11].

The chitosanase activity of

Paenibacillus mucilaginosus TKU032 was highest in shrimp head meal with a value of 0.53 U/mL. These sources have high protein and minerals with low chitin [

39]. So, C/N sources must be tested, especially from fishery waste, to determine the best media. The combination of fishery waste can also be used as a medium, even as a source of chitosanase-producing microorganisms. The mold

Aspergillus fumigatus 11T-004 was successfully isolated from soil from trash cans at fish markets using a combination of shrimp and crab shell waste as the medium. The mold produces chitosanase with a specific activity of 13 U/mg, 64 kDa at 40

oC and pH 5.5 [

30,

36].

3.2.3. Characterization of Chitosanase

Chitosanase from bacteria, fungi, and fishery waste is characterized to be used optimally. Parameters observed included molecular weight, temperature, pH, and specific activity. The lowest molecular weight of chitosanase was 20.5 kDa, sourced from jelly fig sap, while the highest was obtained from

Aspergillus fumigatus 11T-004 of 64 kDa. Chitosanase has a medium molecular weight of 20-75 kDa [

34]. Chitosanase from the

Bacillus strain has an average molecular weight of 20 kDa or 40 kDa, while that of the

Paenibacillus strain is in the range of 30-70 kDa [

32,

41].

On average, the optimum temperature for chitosanase is 40-70⁰C, while the optimum pH is < 7 (acid). The stability of chitosanase against high temperatures occurs because the substrate can prevent the thermal inactivation of chitosanase activity. Based on

Table 2, chitosanase has optimum activity in acidic conditions, but the enzyme has stability over a wide pH range from acidic to primary conditions. However, under too acidic (< 4) or alkaline (> 9) conditions, chitosanase activity decreased due to protein instability. Chitosanase activity from microorganisms and fishery waste has various values; these data are essential for applying these enzymes, primarily to determine the concentration in the chitosan hydrolysis process. However, other factors such as pH, temperature, substrate, and enzyme inhibitors are also important.

3.3. Chitosan Hydrolisis

Enzymatic hydrolysis of chitosan uses chitosanase from microorganisms and fishery waste. The enzymatic method was chosen because it is environmentally friendly, and the final product can be controlled but requires high costs [

5]. The hydrolysis process can be minimized using the crude enzyme chitosanase so that COS production costs are also low. COS production using the crude enzyme chitosanase is presented in

Table 3.

Table 3 shows that the use of crude enzymes has often been applied, especially extracellular chitosanase from bacteria and molds. The purity of the enzymes used in the chitosan hydrolysis process affects the COS produced. Chitosanase can break the glycosidic bonds in GlcNAc-GlcN, GlcN-GlcNAc, and GlcN-GlcN, but crude enzyme hydrolysis is slow in the GlcN-GlcN bonds [

38,

49]. These conditions do not inhibit the crude enzymes from producing fdCOS products with DP similar to pure chitosanase. Applying crude enzymes can benefit the industry without going through a purification process, but the risks posed by contaminants must be considered [

50].

The concentration of crude enzyme used for hydrolysis of chitosan is based on the specific activity of chitosanase, mainly from bacteria and fungi. Hydrolysis is carried out based on the production time with the best activity value, usually in the logarithmic phase. Chitosanase from fishery waste needs to be optimized to get the best concentration through the sugar reduction process. Crude enzyme chitosanase from blue crab (

Portunus segnis) reduced the highest sugar at a concentration of 100 U/g with a hydrolysis time of 48 hours [

14].

Chitosan in COS production must have a high DD so that the hydrolysis process becomes optimal. Hydrolysis with a longer incubation time aims to maximize polymerization. Crude enzyme chitosanase from

Bacillus cereus TKU 034 and 038 cultures hydrolyzed chitosan for six days [

34,

35], while

Bacillus cereus TKU 027 and

Penicillium janthinellum D4 cultures took 72 and 48 hours [

31,

52]. The resulting COS products had DP and molecular weights that did not differ significantly with different polymer compositions. However, the chitosan used has a different DD of 60% and 90%, respectively. The acetyl group in the polymer is related to the degree of deacetylation of chitosan [

3].

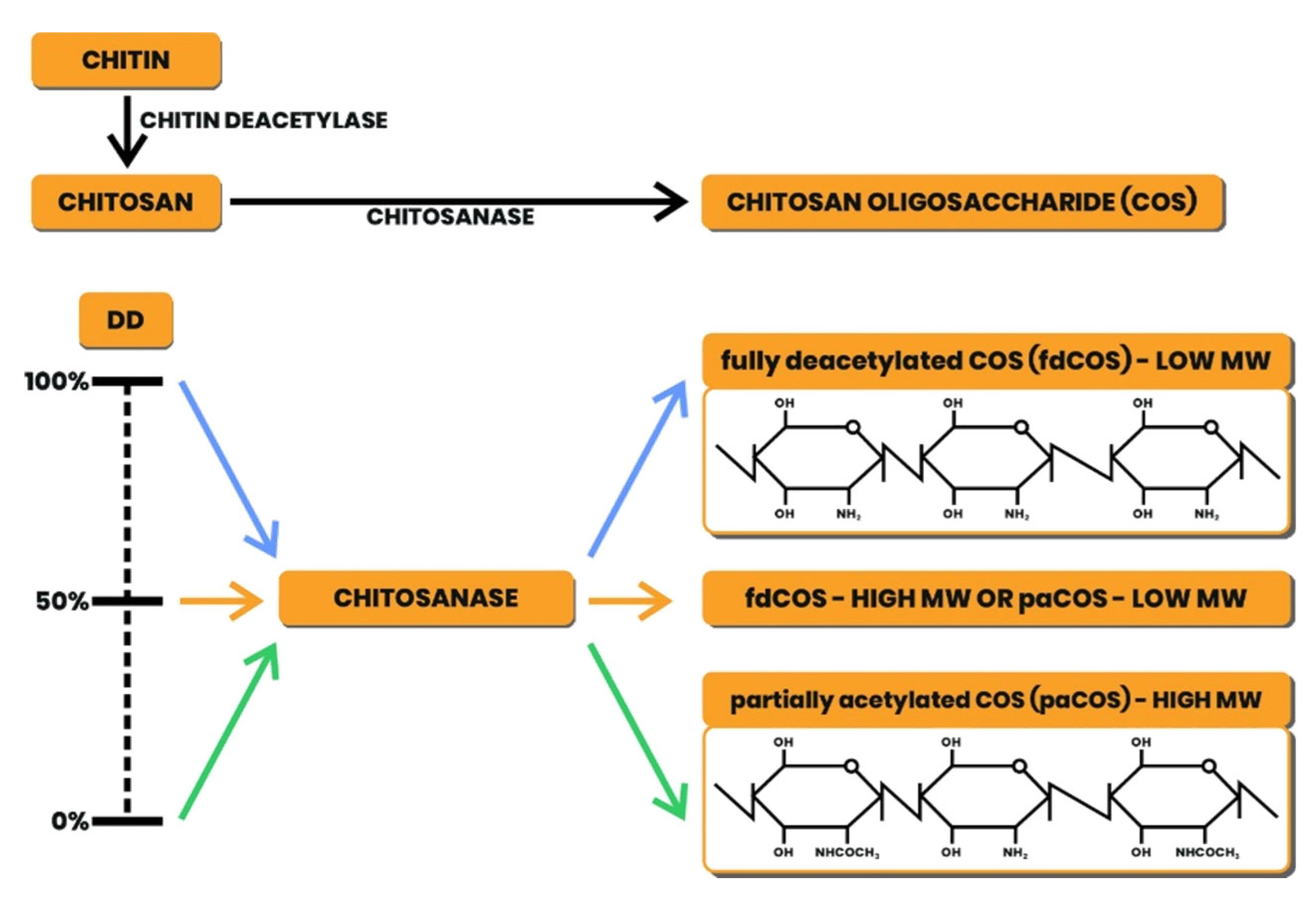

Based on

Figure 4, the strategy for COS production is carried out using chitosan with a high DD to produce fdCOS, which has a low BM; if the DD of chitosan is low, then the paCOS produced with a high BM. The paCOS type is often generated because there is still an acetyl group shown from DD chitosan. Chitosan with DD 90% is best as a substrate for COS production compared to DD 70-80%. The resulting COS still contains less number of acetyl groups (two or more) [

53]. Pacos have a heteropolymer; if the substrate has a DD > 85%, it can have a homopolymer containing only amine and no acetyl groups. The food and medical industries use chitosan with a DD >85%. In COS production, substrates with a DD of 98% produce fdCOS with a DP of 2-9, and the COS has a DD of 100%, which was analyzed using MALDI-TOF with a comparison of COS with food grade standards [

41].

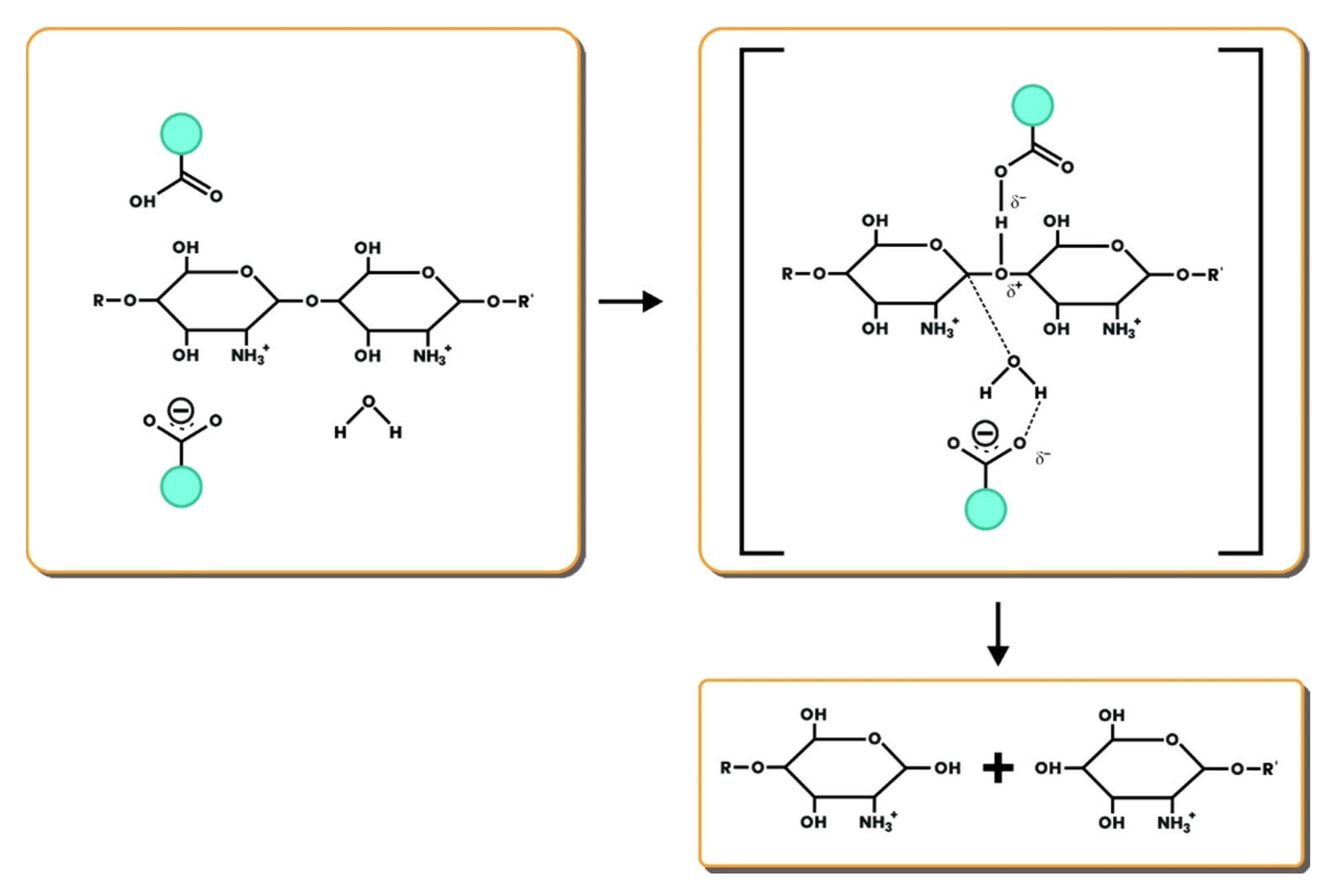

The type of chitosanase affects the enzyme's action mechanism on COS production—for example, the chitosanase family GH46 which is often found in groups of bacteria. Residues in the critical gap play an essential role in the interaction between the enzyme and the substrate, as well as the interaction between the pyranose ring and the binding of the substrate. Chitosanase from the GH46 family works with a reversal mechanism that changes the isomeric conformation of the chitosan unit (

Figure 5). In this mechanism, the enzyme's binding to the substrate is assisted by the carbohydrate-binding module (CBM), which can increase the concentration of the enzyme near the substrate [

54].

4. Conclusions

Hydrolysis of chitosan in COS production can be carried out with crude enzyme chitosanase. The sources of chitosanase used were bacteria, molds, and fishery waste. Bacteria and mold were isolated from fishery waste and soil, especially around chitin-containing land such as fishery waste, marine sediments, and swamps. Fishery waste can be a source of extracellular chitosanase, especially in the shells and viscera of fish and crustaceans.

Crude enzyme chitosanase can be applied to COS production to reduce costs, but the COS produced has characteristics according to standards. The chitosan hydrolysis process with crude enzyme chitosanase is more effective in glycosidic bonds with the same group. The resulting polymer belongs to the paCOS type, which still contains acetyl groups. The chitosan must have a high DD so that the hydrolysis is more optimal and can produce fdCOS-type polymers. Currently, research on COS production using the crude enzyme chitosanase is still limited to the preparation process. The biological activity of COS studied is still limited to its activity value, such as antibacterial, antioxidant, anticancer, and others. The mechanism for inhibiting COS produced using crude enzymes on microorganisms, free radicals, and others is still limited. In addition, the source of the chitosanase enzyme from fishery waste is still limited. If viewed based on its potential, fishery waste can be used as an alternative source of chitosanase, especially the use of crude enzymes in COS production. Based on this description, research directions regarding COS include:

Production and mechanism of crude enzyme chitosanase from fishery waste in COS production

b. Relationship between chitosan parameters and COS characteristics produced through hydrolysis process using crude enzyme chitosanase

c. Chitosan polymerization into COS by preparation of crude enzyme chitosanase

d. Biological activity and inhibition mechanism of COS produced with crude enzyme chitosanase

e. The application and effectiveness of COS resulted from crude enzyme chitosanase preparation in the food, medical, agricultural, fishery, and other industries.

Author Contributions

E.R.: conceptualization, design, edit and review, A.M.: design, writing, review and literature search, C.P.: design, editing, drafting review, R.O.K.: editing, drafting review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universitas Padjajaran

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are conveyed to Universitas Padjadjaran, which financed the publication of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pierre, G.; Dubessay, P.; Dols-lafargue, M. Applied Sciences Modification of Chitosan for the Generation of Functional Derivatives. [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, M.B.; Struszczyk-swita, K.; Li, X. Enzymatic Modifications of Chitin,. 2024, 7. 7. [CrossRef]

- Miguez, N.; Kidibule, P.; Santos-moriano, P.; Ballesteros, A.O.; Fernandez-lobato, M.; Plou, F.J. Applied Sciences Enzymatic Synthesis and Characterization of Different Families of Chitooligosaccharides and Their Bioactive Properties. 2021.

- Mourya, V.K.; Inamdar, N.N.; Choudhari, Y.M. Chitooligosaccharides : Synthesis, Characterization and Applications 1. 2011, 53, 583–612. [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.; Park, R. Bioproduction of Chitooligosaccharides: Present and Perspectives. 2014, 5328–5356. [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Sun, Y.; Dai, X. A Review of the Preparation, Analysis and Biological Functions of Chitooligosaccharide. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Lin, B.; Zhao, L. Heterologous Expression and Characterization of a High-Efficiency Chitosanase From Bacillus Mojavensis SY1 Suitable for Production of Chitosan Oligosaccharides. 2021, 12, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Zhou, M.; Wu, S.; Pan, S. Depolymerization of Chitosan by Enzymes from the Digestive Tract of Sea Cucumber Stichopus Japonicus. 2012, 11, 423–428. [CrossRef]

- Sangwaranatee, N.W.; Teanchai, K.; Kongsriprapan, S.; Siriprom, W. ScienceDirect Characterization and Analyzation of Chitosan Powder from Perna Viridis Shell. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 13922–13925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin-crini, N.; Lichtfouse, E.; Torri, G.; Crini, G.; Morin-crini, N.; Lichtfouse, E.; Torri, G.; Fundamentals, G.C.; Morin-crini, N.; Lichtfouse, E.; et al. Fundamentals and Applications of Chitosan To Cite This Version : HAL Id : Hal-02152878 Fundamentals and Applications of Chitosa; 2019; ISBN 9783030165383. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Benjakul, S.; Prodpran, T. Chitooligosaccharides from Squid Pen Prepared Using Different Enzymes : Characteristics and the Effect on Quality of Surimi Gel during Refrigerated Storage. 2019, 4, 1–10.

- Messerli, M.A.; Raihan, M.J.; Kobylkevich, B.M.; Benson, A.C.; Bruening, K.S.; Shribak, M.; Rosenthal, J.J.C.; Sohn, J.J. Construction and Composition of the Squid Pen from Doryteuthis Pealeii. 2019, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Wegner, L.; Kinoshita, A.; Friol, F.; Paiva, G. De; Negraes, P.; Soares, D.A. Only Carapace or the Entire Cephalothorax : Which Is Best to Obtain Chitosan from Shrimp Fishery Waste ? J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affes, S.; Aranaz, I.; Hamdi, M.; Acosta, N.; Ghorbel-bellaaj, O.; Heras, Á.; Nasri, M.; Maalej, H. CR. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Aklog, Y.F.; Egusa, M.; Kaminaka, H.; Izawa, H.; Morimoto, M.; Saimoto, H.; Ifuku, S. Protein / CaCO 3 / Chitin Nanofiber Complex Prepared from Crab Shells by Simple Mechanical Treatment and Its Effect on Plant Growth. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Suo-lian, W.; Huai-bin, K.; Dong-jiao, L. Technology for Extracting Effective Components from Fish Scale. 2017, 7, 351–358. [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.J.; Fernandez, J.G.; Sohn, J.J.; Amemiya, C.T. Chitin Is Endogenously Produced in Vertebrates Report Chitin Is Endogenously Produced in Vertebrates. Curr. Biol. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, S.; Hari, S.; Annamareddy, K.; Abanti, S.; Kumar, P. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules Physicochemical Properties and Characterization of Chitosan Synthesized from Fish Scales, Crab and Shrimp Shells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 1697–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, S. Characterization and Cytotoxicity of Low - Molecular - Weight Chitosan and Chito - Oligosaccharides Derived from Tilapia Fish Scales. 2021, 373–377. [CrossRef]

- Science, E. Characterization of Chitin Extracted from Fish Scales of Marine Fish Species Purchased from Local Markets in North Sulawesi, Indonesia Characterization of Chitin Extracted from Fish Scales of Marine Fish Species Purchased from Local Markets in North Sula. 9–13.

- Zhang, Y.; Tu, D.; Shen, Q.; Dai, Z. Fish Scale Valorization by Hydrothermal Pretreatment Followed by Enzymatic Hydrolysis For. 2019, 1–14.

- Kohlhoff, A.M.; Niehues, A.; Wattjes, J.; Julie, B.; Cord-landwehr, S.; El, N.E.; Bernard, F.; Rivera-rodriguez, G.R.; Moerschbacher, B.M. Chitinosanase: A Fungal Chitosan Hydrolyzing Enzyme with a New and Unusually Specific Cleavage Pattern. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.D.; Wang, W.X.; Cong, H.H.; Yin, H. Characterization of the Specific Mode of Action of a Chitin Deacetylase and Separation of the Partially Acetylated Chitosan Oligosaccharides. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Á.; Mengíbar, M.; Moerchbacher, B.; Acosta, N.; Heras, A. The Effect of Preparation Processes on the Physicochemical Characteristics and Antibacterial Activity of Chitooligosaccharides. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Activity, T.A. Tailored Enzymatic Synthesis Of. 2019.

- Yin, H.; Du, Y.; Dong, Z. Chitin Oligosaccharide and Chitosan Oligosaccharide : Two Similar but Different Plant Elicitors. 2016, 7, 2014–2017. [CrossRef]

- Zou, P.; Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G. Advances in Characterisation and Biological Activities of Chitosan and Chitosan Oligosaccharides. FOOD Chem. 2016, 190, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 28. No Title, 9503; ISBN 0127809503.

- Adesina, M.F.; Jansson, J.K.; Smalla, K.; Hjort, K.; Bergstr, M. Chitinase Genes Revealed and Compared in Bacterial Isolates, DNA Extracts and a Metagenomic Library from a Phytopathogen-Suppressive Soil ¨ 1,. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Chand, S.; Tripathi, P. Microbial Degradation of Chitin Waste for Production of Chitosanase and Food Related Bioactive Compounds 1. 2014, 50, 125–133. [CrossRef]

- Dzung, A.; Huang, C.; Liang, T.; Nguyen, V.B. Production and Purification of a Fungal Chitosanase and Chitooligomers from Penicillium Janthinellum D4 and Discovery of the Enzyme Activators. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 108, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.W.J.S.T. Production, Purification and Characterisation. 2014, 2237–2248. [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.W.; Huang, C.T.; Dzung, N.A.; Wang, S.L. Squid Pen Chitin Chitooligomers as Food Colorants Absorbers. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.W.; Lo, B.C.; Wang, S.L. Chitinolytic Bacteria-Assisted Conversion of Squid Pen and Its Effect on Dyes and Pigments Adsorption. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 4576–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, T.; Chen, W.; Lin, Z.; Kuo, Y.; Nguyen, A.D.; Pan, P.; Wang, S. An Amphiprotic Novel Chitosanase from Bacillus Mycoides and Its Application in the Production of Chitooligomers with Their Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Evaluation. 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Chand, S.; Tripathi, P. Enzymatic Production of Glucosamine and Chitooligosaccharides Using Newly Isolated Exo- b - D -Glucosaminidase Having Transglycosylation Activity. 3 Biotech 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Ji, L.; Du, X.; Sang, Q.; Che, F. Enzymatic Single-Step Preparation and Antioxidant Activity of Hetero-Chitooligosaccharides Using Non-Pretreated Housefly Larvae Powder. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doan, C.T.; Tran, T.N.; Nguyen, V.B.; Nguyen, A.D. Reclamation of Marine Chitinous Materials for Chitosanase Production via Microbial Conversion By. [CrossRef]

- Chitosan, B.; Doan, C.T.; Tran, T.N.; Nguyen, V.B.; Nguyen, A.D. Production of a Thermostable Chitosanase from Shrimp Heads via Paenibacillus Mucilaginosus TKU032 Conversion and Its Application in The. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.A. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology Microbial Valorization of Shrimp Byproducts via the Production of Thermostable Chitosanase and Antioxidant Chitooligosaccharides. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 20, 101269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, C.T.; Tran, T.N.; Nguyen, V.B.; Tran, T.D. Bioprocessing of Squid Pens Waste into Chitosanase by Paenibacillus Sp. TKU047 and Its Application In.

- Chitosanase, T.; Li, S. Purification and Characterization of A New Cold-Adapted and Thermo-Tolerant Chitosanase from Marine Bacterium Pseudoalteromonas Sp. SY39. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, J.; Dantas, D.M.; Sousa, N.; Eduardo, C.; Padilha, D.A.; Kelly, N.; Araújo, D.; Silvino, E. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology Enhancing Chitosan Hydrolysis Aiming Chitooligosaccharides Production by Using Immobilized Chitosanolytic Enzymes. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 28, 101759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanah, H.; Cahyaningtyas, A.; Suyotha, W.; Cheirsilp, B. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology Statistical Optimization of Halophilic Chitosanase and Protease Production by Bacillus Cereus HMRSC30 Isolated from Terasi Simultaneous with Chitin Extraction from Shrimp Shell Waste. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 101918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baehaki, A.; Lestari, S.D.; Gofar, N.; Wahidman, Y. Partial Characterization of Chitosanase from Digestive Tract of Channa Striata. 2016, 4–7.

- Chang, C.; Lin, Y.; Lu, S.; Huang, C.; Wang, Y. Characterization of a Chitosanase from Jelly Fig ( Ficus Awkeotsang Makino ) Latex and Its Application in the Production of Water- Soluble Low Molecular Weight Chitosans. 2016, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Josephine, C.; Handayani, R.; Halim, Y. Isolation, Identification and Chitinolytic Index of Bacteria from Rotten Tiger Shrimp ( Penaeus Monodon ) Shells. 2020, 13, 360–371.

- F, R.; Lundblad, G.; Lind, J.; Slettengren, K. Chitinolytic Enzymes in the Digestive System of Marine Fishes. 1979, 321, 317–321.

- Heras, A.; Acosta, N. Influence of Preparation Methods of Chitooligosaccharides on Their Physicochemical Properties and Their Anti-Inflammatory Effects in Mice and in RAW264. 7 Macrophages. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Tsai, C.; Liou, P.; Wang, C. Pilot-Scale Production of Chito-Oligosaccharides Using an Innovative Recombinant Chitosanase Preparation Approach. 2021.

- Affes, S.; Maalej, H.; Aranaz, I.; Acosta, N.; Heras, Á.; Nasri, M. Jo u Rn Al Pr F. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.W.; Liu, C.P.; Wu, C.; Wang, S.L. Applied Development of Crude Enzyme from Bacillus Cereus in Prebiotics and Microbial Community Changes in Soil. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 92, 2141–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, L.; Jiang, S.; Ma, L. Enzymatic Production of High Molecular Weight Chitooligosaccharides Using Recombinant Chitosanase from Bacillus Thuringiensis BMB171. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Lett. 2018, 46, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Zhou, S.; Tan, Y.; Feng, J.; Bai, Y.; He, J.; Cao, H.; Che, Q.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. Biodegradation and Prospect of Polysaccharide from Crustaceans. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).