1. Introduction

The Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has forced students from numerous countries and regions to study at home and restricted their outdoor activities. In this situation, for young adolescents, more leisure time is spent alone, due to the lack of face-to-face social interaction with friends or classmates. Leisure time for adolescents can be defined as the time they choose to engage in structured or unstructured activities after school or on weekends [

1]. During the period of COVID-19 pandemic, undergraduate students have many other discretionary activities at home, in addition to day-to-day online courses. Theoretical perspectives from developmental psychology suggest that the components of individual self-consciousness in the middle and late adolescence, including self supervision and self-control, are highly developed and mature [

2]. That is to say, undergraduates should generally be better than middle school students under normal self-management ability. However, do undergraduates display better time-management behaviors than primary and secondary school students during COVID-19? Studies suggest that it is very common for undergraduates to have difficulties in utilizing their free time, which directly or indirectly leads to many problems such as procrastination, inattention, insufficient sleep and even internet addiction [

3,

4]. From a positive perspective, efficient utilization of leisure time to engage in healthy activities can promote self-directed learning, academic achievement, happiness, and quality of life of undergraduates [

5]. In this sense, exploring how undergraduates use their free time and motivation is valuable. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, this study examines undergraduates' home-based behaviors and their underlying mechanisms.

1.1. Time and self-management for undergraduates

Garrison argued that effective time management relies on self-management, indicating that the term "time management" truly means managing oneself [

6]. Carolina et al. [

7] defined self-management as one of the components of self-directed learning training, alongside learning planning, desire for learning, self-confidence, self-evaluation, and other elements . Self-management is a crucial topic for undergraduates [

8,

9,

10] and is the core factor that predicting their academic performance. The demand to manage time can cause stress for college students [

11]. When it comes to self-management, time management is often considered the primary factor. A questionnaire survey of 119 undergraduates revealed that self-management and self-monitoring significantly predicted academic achievement, with self-management being the strongest predictor [

12]. Additionally, undergraduates’ self-management programs should include healthy sleep hygiene, nutrition, stress management, time management, and social connections with family and friends [

13]. Thus, the connection between the level of self-management to self-directed learning is an area of research that has garnered much attention. A study that collected data from 383 nursing undergraduates indicated a correlation between time management and self-directed learning ability [

5]. It is therefore inferred that self-directed learning ability is linked to the level of self-management. Bolden et al [

3] even directly used the term "self-management of time" to explore the relationship among academic performance, procrastination, ADHD symptoms, and executive functions (EFs) over a two-year period. The five components that measure EFs are time management, organization/problem solving, restraint, motivation, and emotion regulation. Initial findings confirmed that EFs modulated the association between procrastination and ADHD symptoms. Subsequent analysis showed that self-management of time and organization/problem-solving played a role in the five components of EFs.

Furthermore, it has been suggested that effective time management is an important way to prevent and address procrastination and ADHD symptoms among undergraduates, further highlighting the significance of this topic [

14]. However, the majority of research on this topic has been conducted in typical everyday situations. A study on online learning of high school students suggested that emotion management could plays important role in time and self-management [

15]. With COVID-19 pandemic, there has been an increase in anxiety and stress levels among students [

16,

17,

18,

19]. In this context, particularly during lockdown periods, it is possible that undergraduate students’ self-management behavior could be influenced by more complex factors, which warrants further investigation.

1.2. Leisure time behavior and values

Leisure time management, also known as free-time management, is commonly considered a form of wisdom [

20]. Wang et al. found that undergraduates who excelled in managing their free time reported a higher quality of life [

4]. Subsequently, a survey of 500 undergraduate students found that five dimensions of free-time management, namely goal setting and evaluating, technique, values, immediate response, and scheduling, were significantly negatively correlated with leisure boredom [

21]. A recent study on the relationships among the free-time management, leisure boredom, and internet addiction among undergraduates indicated that free-time management reduced the sense of boredom in leisure time, which in turn the likelihood of internet addiction [

22]. Activities that adolescents engage in during their leisure time may have positive or negative effects on their socialization process [

23,

24,

25].

Factors influencing leisure time behavior have been the focus of research in recent years. Evidence suggests that daily behavior is actually a reflection of an individual's values [

26,

27,

28,

29]. In particular, when individuals have the freedom to choose their actions, such as leisure time, their behavior tends to be driven by values [

30]. Pavlović and Ilić [

28] examined the relationship between adolescent leisure time behavior and the 10 basic values identified by Schwartz [

31] in 1349 Serbian high school students. Their research suggested that values play an important role in motivating of leisure time activity. Different values are typically expressed through different activities, and the same values can inspire different activities. Given that research can only be conducted in a relatively unconstrained context To ensure that adolescents' behavior is driven by values, rather than external constraints, researchers have chosen to study leisure time activities, are relatively unconstrained [

28,

32].

The literature on leisure time behavior has primarily focused on adolescent students [

33,

34]. Research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic has specifically addressed the reduced physical activity and increased obesity among adolescents due to months of school closure [

35,

36], as well as the negative mood problems experienced by adolescents who excessively use electronic devices [

37]. However, the impacts of COVID-19 vary across different age groups. As undergraduate students have a broader perspective of the world and are in the process of making career choices [

2], they generally consider COVID-19 as a real threat to their health and life [

37]. Additionally, they believe that crisis event has affected their sense of security [

31], one component of the values, which lead some undergraduates to reconsider their career planns [

39]. While previous studies have focused on medical students as research samples [

40,

41,

42], there are fewer studies targeting undergraduates in general and even fewer linking behavior and values during lockdown. In view of the recognized role of values in driving free time activity, it is of great significance to investigate the relationship between values reflected in students’ perceptions of the COVID-19 crisis and free time behavior. Moreover, understanding how to guide undergraduates' values during the pandemic could help them live full, happy, and meaningful lives while in lockdown at home

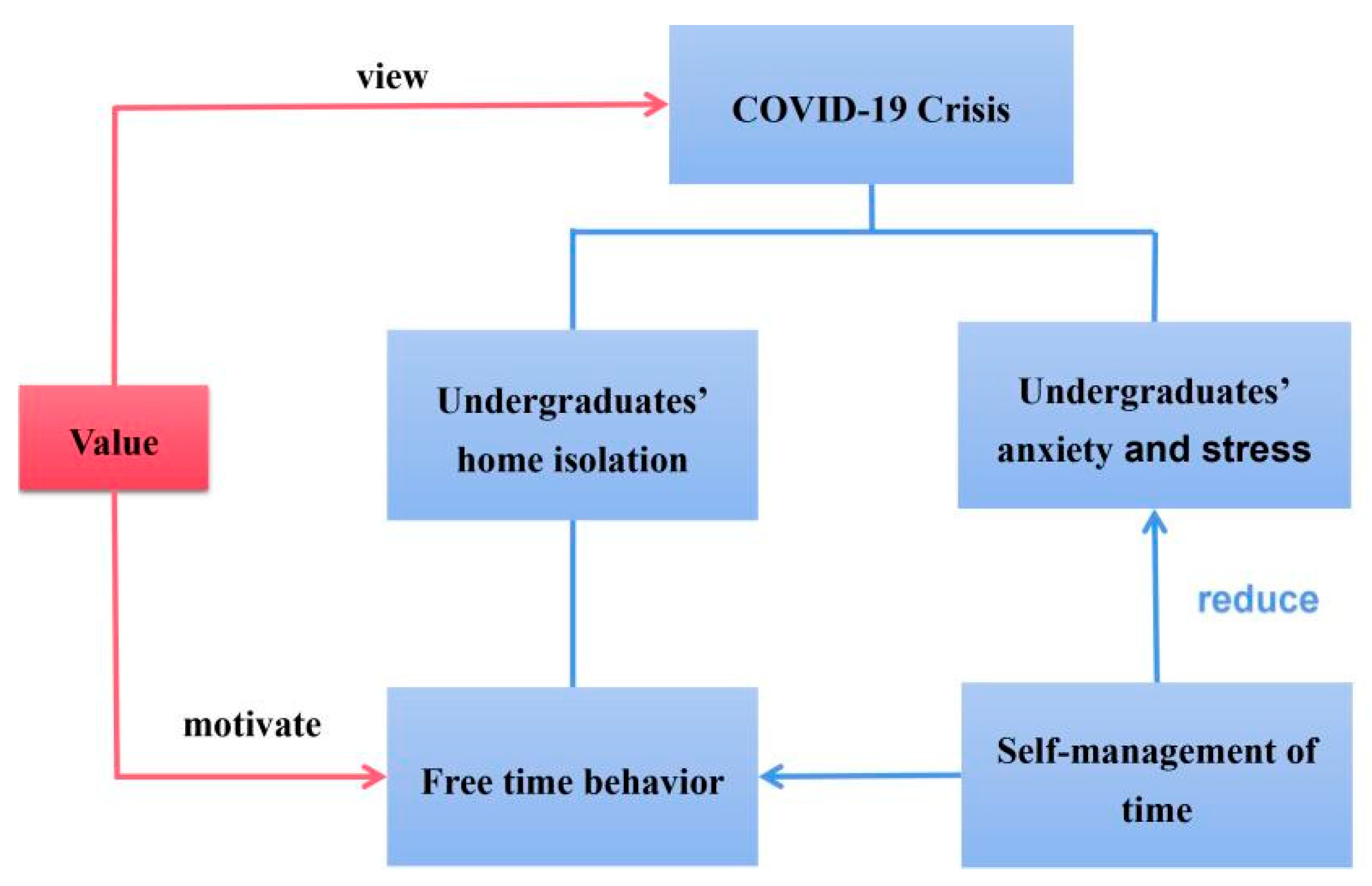

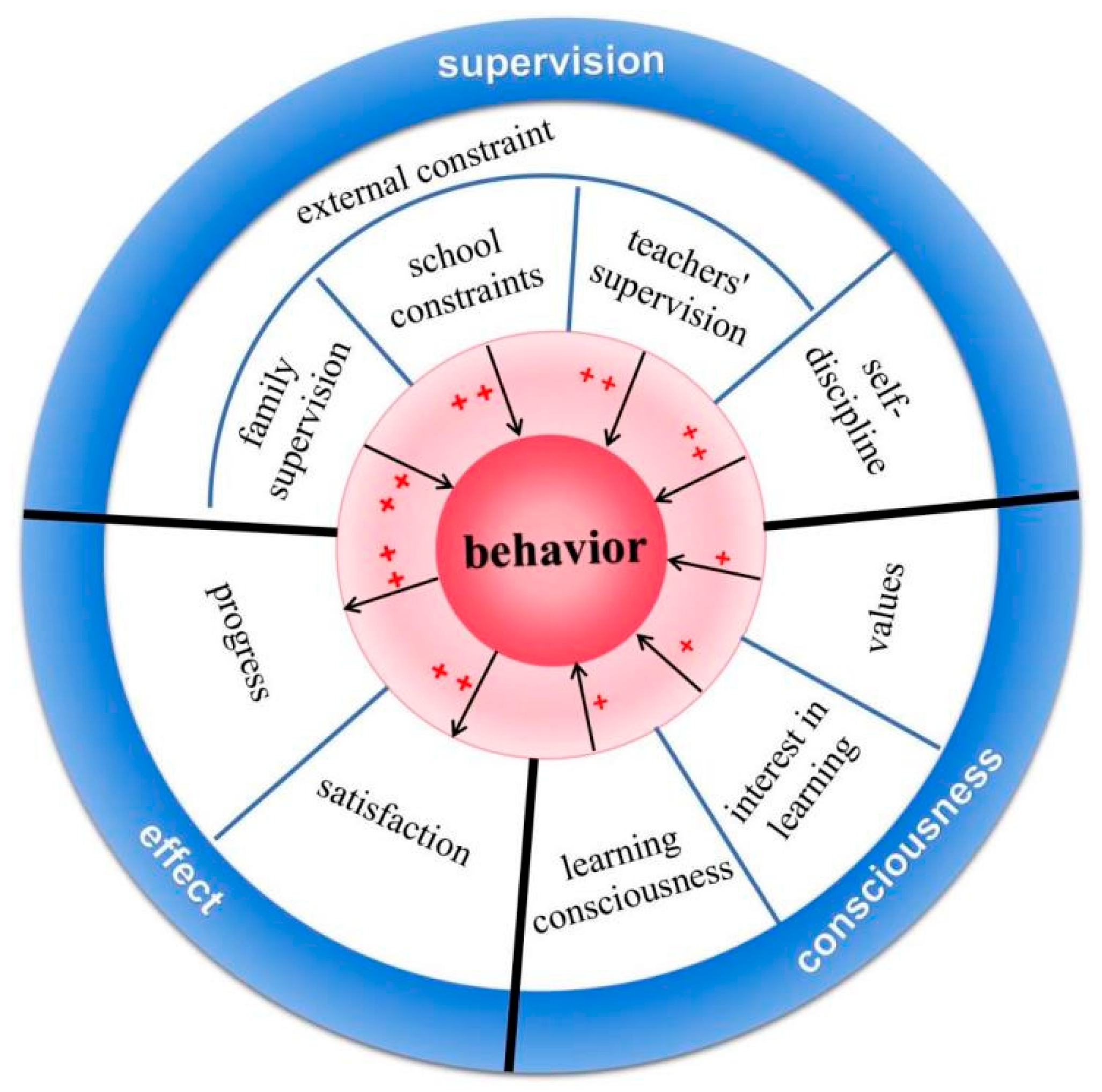

Figure 1 depicts the theoretical framework of this study based on the aforementioned literature. During the COVID-19 pandemic, undergraduate students have been quarantined at home, leading to an anxious and stressful emotional state. Self-management and time management have played a crucial role in regulating undergraduates' leisure time behavior and effectively alleviating negative emotions of tension and anxiety caused by the pandemic. However, in this relationship, values may play a unique dual role. On the one hand, values influence perception of the COVID-19 crisis; on the other hand, they drive behavior during isolated free time at home. The innovation of this study is to explore the regulatory mechanism of undergraduate values on behavior during the COVID-19 lockdown, to better help them manage themselves under the guidance of right values and make better use of their free time at home.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework of the study.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework of the study.

2. Methods

This research adopted a hybrid research paradigm; hybrid research is both a method and a methodology and is also known as the third research paradigm. Hybrid research has the characteristics of quantitative and qualitative research and uses the advantages of both in the same research. The first stage of the study mainly addressed the first question: Did undergraduates have the best self-management level during the COVID-19 lockdown period? A questionnaire survey was conducted over the whole study period to determine whether undergraduates' home behaviors and activities showed the most self-discipline through horizontal comparison. The second stage mainly addressed the second question: How did undergraduate students' attitudes towards the COVID-19 crisis affect their behavioral activities? Through semistructured interviews with undergraduates, the influence mechanism between them was analysed.

2.1 Participants

The students volunteered to participate in the research. A total of 388 students participated in the questionnaire research, and 380 provided valid responses, including 122 primary school students, 174 secondary school students, and 84 undergraduate students; among the undergraduate students, 39 students were from key universities and 45 were from ordinary universities (1:1.15). After the questionnaire survey, a total of 13 undergraduates participated in interviews, which were also voluntary. The interviewees ranged in age from 18 to 23, with a median age of 20. They were distributed in different majors and grades, including 6 students from key universities and 7 students from ordinary universities (1:1.28) and 7 male students and 6 female students.

2.2 Research design and procedure

This research was divided into two stages: questionnaire survey and interview research. The first stage mainly addressed question 1: During the COVID-19 lockdown, did undergraduates have better management skills than primary and secondary school students? A voluntary, web-based, and anonymous questionnaire was implemented via the Questionnaire Star app during COVID-19 prevalence in 2020, which was used to investigate students' home behaviors and activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. To ensure the validity of the survey data, the purpose and main content of the test were explained to the participants through the WeChat app before the test. The test could be completed in 6 min and each IP address was allowed to submit only one response to prevent “multiple participation” of participants. This research method emphasized that researchers should measure, calculate and analyse the observable parts and their relationships to grasp the overall behavior of students in each section and determine the outstanding characteristics and existing problems of undergraduates' behavior activities through horizontal comparison.

In view of the problems revealed by the questionnaire survey results, we entered the qualitative research stage, which mainly addressed question 2: How did attitudes towards the COVID-19 crisis affect behavior among undergraduates? The researchers used semistructured interviews and text analysis. The interviewees were recruited separately after the questionnaire survey, and the interviews were mainly conducted by telephone. All interviewees were anonymized, and only "No. + Major" was used to distinguish different interviewees. Each interview lasted approximately half an hour and focused on "the past holiday home experience", "current activities at home", and "understanding of COVID-19 crisis". These three themes, using open questions and undergraduate student interaction, combined with the questionnaire survey revealed undergraduate behavior characteristics during that time, and the analysis of undergraduates’ mechanism of influence of attitudes towards COVID-19 crisis on behavioral activities. The structure of this study is shown in the Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structure of the research.

Figure 2.

Structure of the research.

2.3 Instruments and Materials

Student Home behavior Activity Survey Questionnaire. The research tool used during this stage was the Student Home behavior Activity Survey Questionnaire compiled by the researcher. The core question of this questionnaire is "what has been done", that is, "behavior". Related issues include the consciousness behind the behavior, the internal and external constraints that contributed to the behavior, and the ultimate effect of the behavior. As a whole, the questionnaire includes four main dimensions: consciousness, behavior, monitoring and efficacy. For each dimension, a number of second-level indicators are decomposed, and then a number of third-level indicators are decomposed one by one. The corresponding questions are assessed on a Likert scale. The Cronbach's α coefficient on the scale was 0.871 and the Cronbach's α coefficient on all the subscales ranged from 0.723 to 0.851. The questionnaire was revised according to the results to ensure its validity and reliability.

2.3.1 Interview outline

In the semistructured interviews with the undergraduates, there were mainly five questions. In order to ensure the rationality and effectiveness of the interview questions, 17 experts were sent by email to seek opinions on each question. Mark the questions that experts think are appropriate with √ in the table at the end of the question, and write the suggestions for modification in the table at the end of the question. The consultation period is one week. A week later, we received email replies from 15 experts, including 6 front-line college teachers and 9 education researchers. Based on the opinions of 15 experts, the interview questions were partially modified, and the interview outline was finally included below. (1) Please describe your daily activities at home during this winter holiday. (2) Compared with your home life during the winter and summer holidays in secondary school, what changes do you think have taken place? (3) What is your ideal fulfilling life at home? (4) Have you done it thus far? Why is that? (5) Please talk about your feelings during the epidemic. The researcher transcribed the interview recordings, recorded the materials of each respondent, and labelled the materials with a number and the respondent’s major for subsequent coding analysis.

2.3.2 Materials

The questionnaire was distributed online, and the researchers statistically analysed the valid answers. The interviews were conducted by the first author in Chinese, each lasting 30-45 minutes. The main purpose of the interviews was to understand the home behavior activities of undergraduate students and compare the behavior activities during the pandemic with their home experience in secondary school. The students also expressed their views on the pandemic and the psychological changes it caused; all interviews were transcribed verbatim, and selected parts were translated into English.

3. Results

3.1. Data analysis

The questionnaire obtained data on the home activities of students in each period from four dimensions: consciousness, behavior, supervision and effect. All questionnaire data were input into SPSS 20.0, and internal consistency analysis was performed by using Cronbach’s coefficient. After analysis, the α coefficient reached 0.714, which was between 0.7 and 0.8, indicating considerable reliability. The researchers presented the characteristics of undergraduates one by one in four dimensions through descriptive statistics.

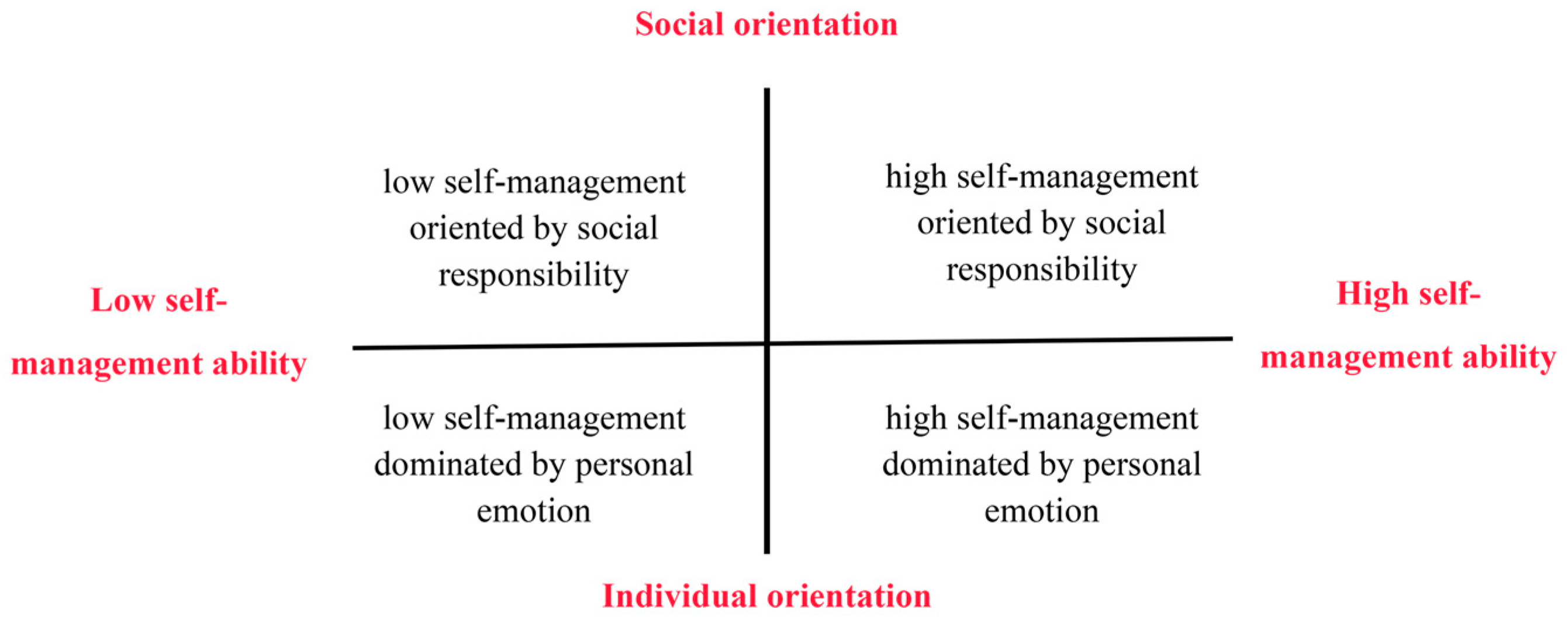

Undergraduates’ "behavioral activities under low self-management ability" and "behavioral activities under high self-management ability" were completely different. On the other hand, through a preliminary analysis of the interview data, students' understanding of the COVID-19 crisis could be divided into "social orientation" and "individual orientation". The above behavioral activities and basic understanding constitute two intersecting dimensions. The four quadrants can roughly divide undergraduates into four categories (Figure 3). This is the basic framework for the analysis of the interview results, and the influencing mechanism of undergraduate students' attitudes towards the COVID-19 crisis on their behavior activities will be discussed in the future by combining the interview documentary classification.

Figure 3.

Undergraduates’ free-time behavior activity and thought cognition quadrant diagram.

Figure 3.

Undergraduates’ free-time behavior activity and thought cognition quadrant diagram.

3.2. behavioral characteristics of undergraduates

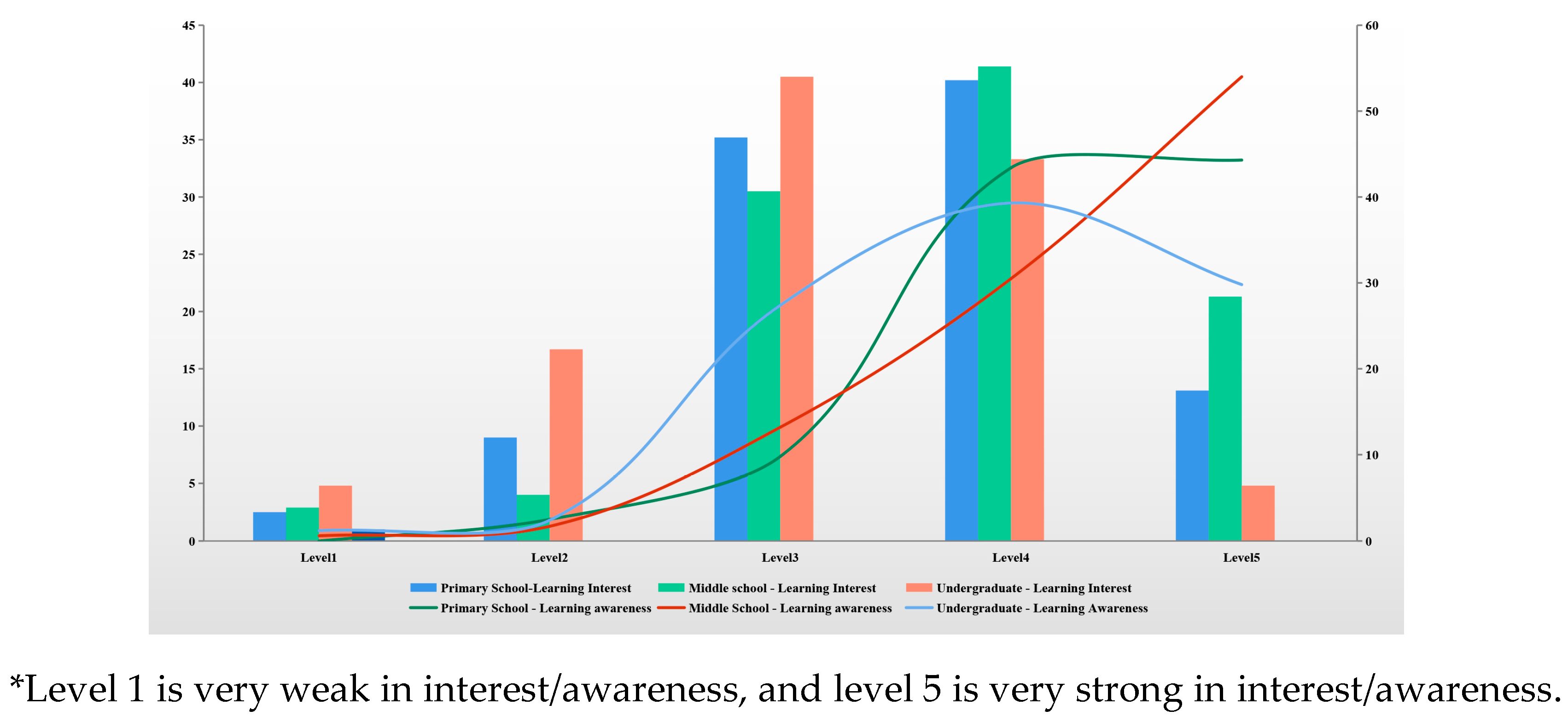

3.2.1. Awareness dimension

Undergraduates' interest in and awareness of learning decrease significantly. In terms of learning consciousness, researchers mainly focus on students' learning interest and awareness in their spare time. The author conducted a correlation test on the whole sample, and the results showed that students' interest in learning was significantly correlated with the importance of learning cognition at the 0.01 level. In other words, the more students enjoy studying, the more they think it necessary to study in their spare time. Figure 4 describes students' understanding of learning in different learning segments. The bar chart depicts learning interest, while the curve depicts learning awareness. We found that secondary school students are the strongest in both interest and awareness, with 62.7% of students holding a positive attitude towards learning and the proportion plummeting to 38.1% in the undergraduate stage. Regarding the awareness of learning, the highest proportion of secondary school students and the lowest proportion of undergraduates think it is "very important" to study in their spare time. On the whole, there is a great contrast between the two adjacent sections of secondary school and university. After students enter university from secondary school, their interest in and consciousness of learning decrease drastically.

Figure 4.

Statistical chart of students' learning interest and learning awareness.

Figure 4.

Statistical chart of students' learning interest and learning awareness.

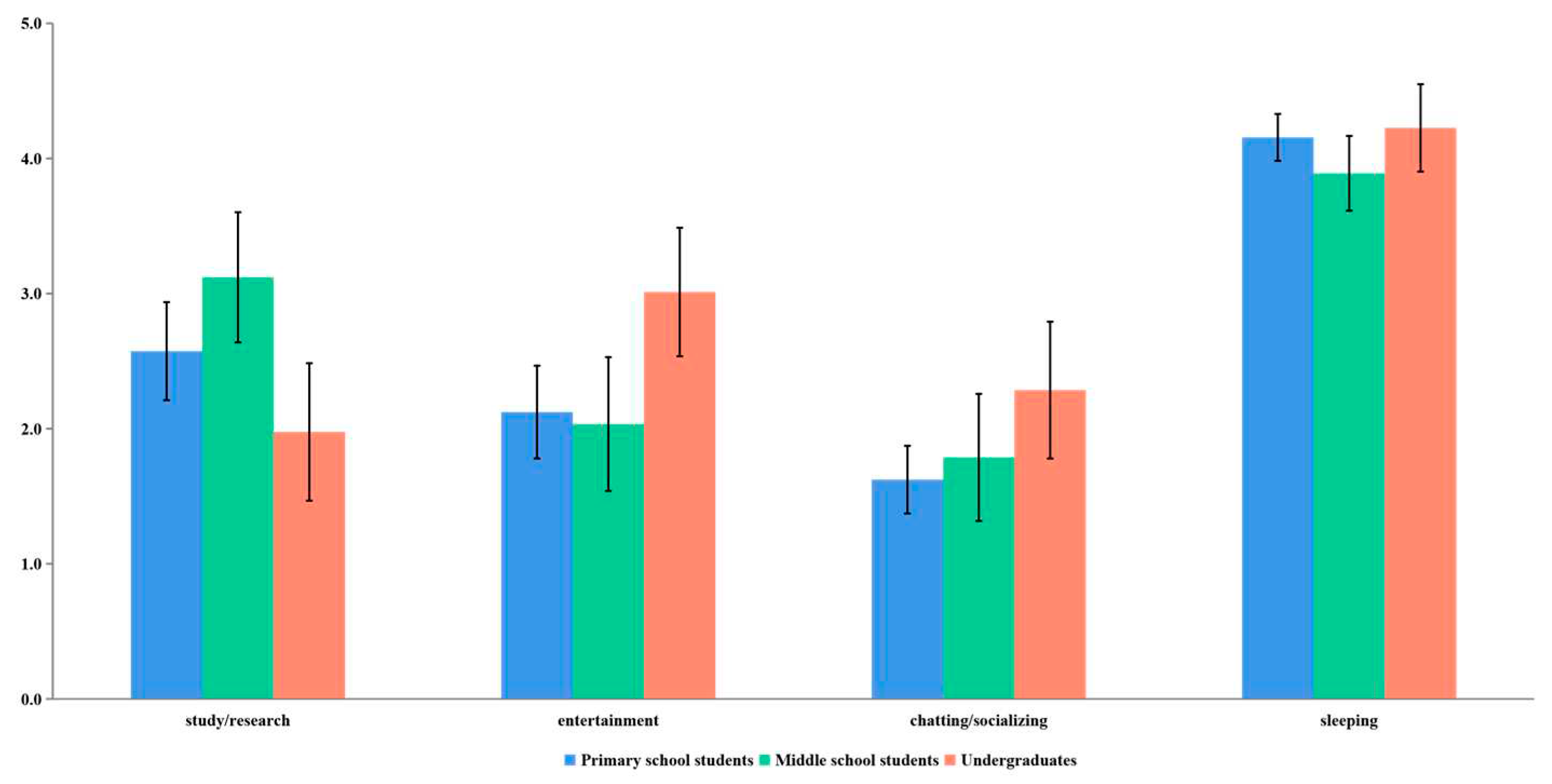

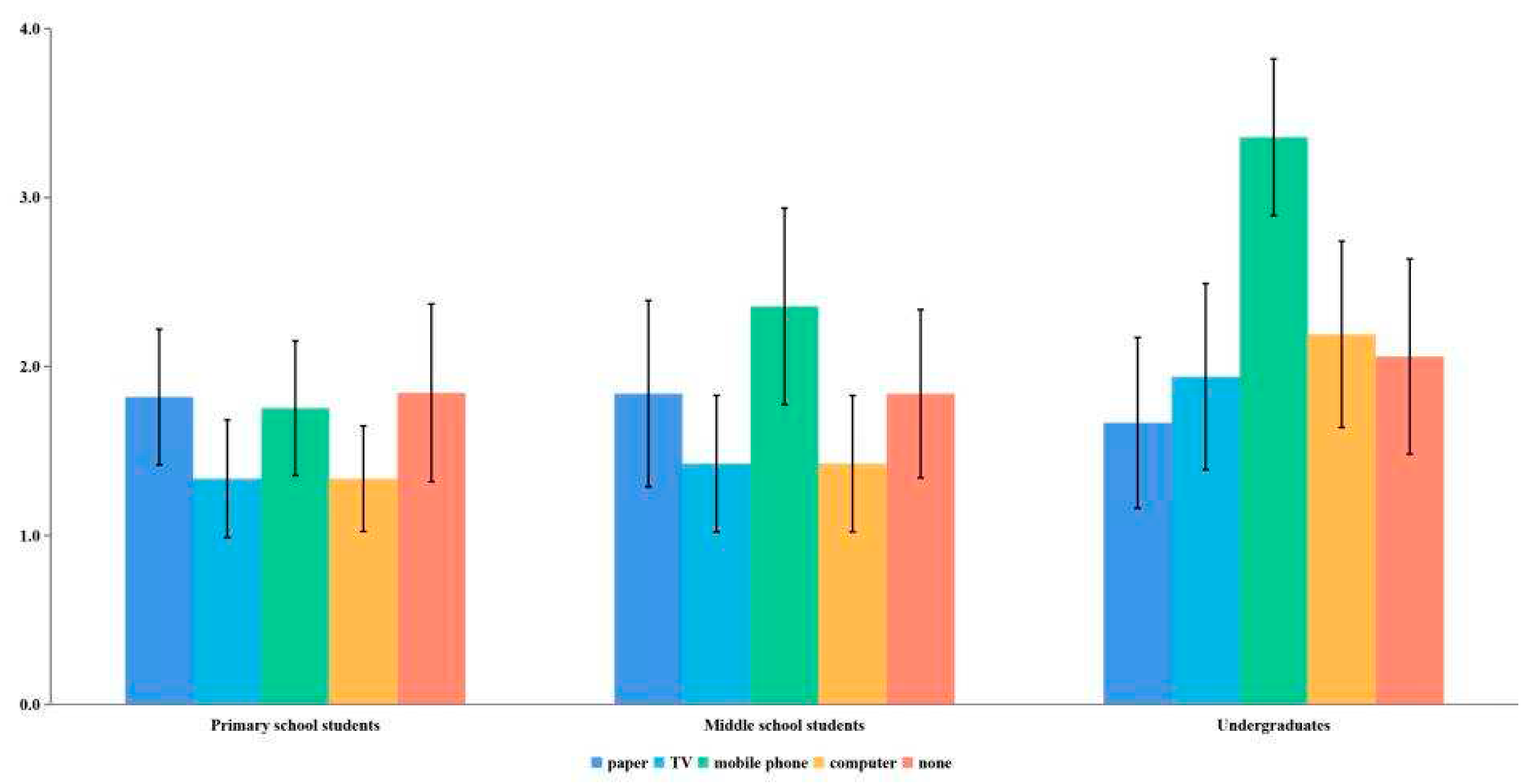

3.2.2. Behavioral dimension

Undergraduates spend the most time using electronic products in a day. Behavior is the core question of the questionnaire, which lists the four main activities of students at home: study/research, entertainment, chatting/socializing and sleeping. In Figure 5, the abscissa is the activity item, and the ordinate value is the average score. The higher the score is, the longer the average daily time of the project. According to the survey results, in addition to the shortest learning time, undergraduates spend the most time on nonlearning activities such as entertainment, socializing and sleeping. Among them, 30.6% of undergraduates sleep more than 10 hours a day, compared with 14.8% of secondary school students. On this basis, the researchers further asked students about their "activity media". Figure 6 shows that, on the whole, students spend more time using mobile phones, computers and other electronic products over the years. Among them, undergraduates spend the most time using mobile phones, far outpacing other media. Taking the midpoint of each range (e.g., three to five hours counted as four hours), the study found that undergraduates spend up to a third of their waking hours each day using their phones.

Figure 5.

Statistical chart of students' time expenditure on different items at home.

Figure 5.

Statistical chart of students' time expenditure on different items at home.

Figure 6.

Statistical chart of students' media use at home.

Figure 6.

Statistical chart of students' media use at home.

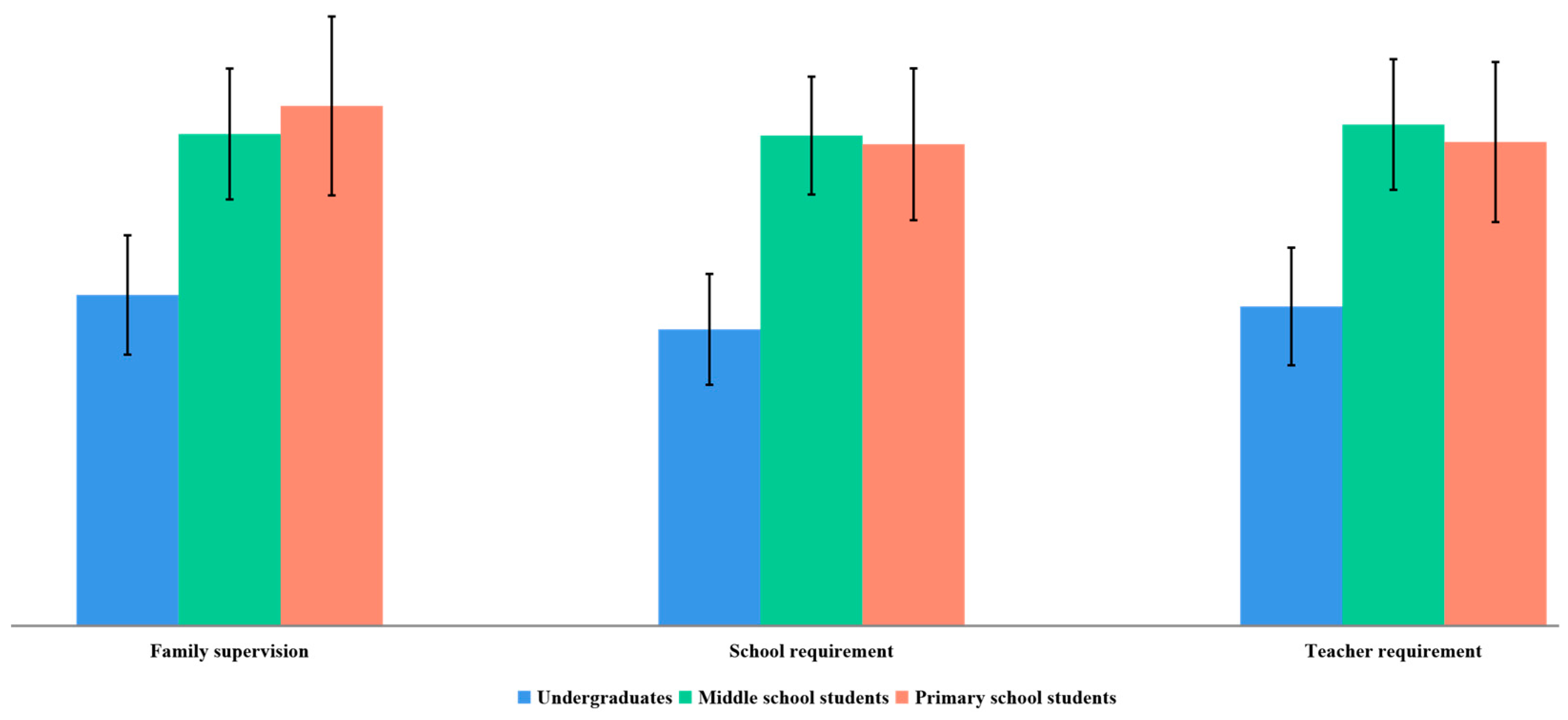

3.2.3 Supervision dimension: Undergraduates enter a "blind spot" regarding external supervision

This study divides the supervision dimension into "self-restraint" and "external restraint". The family, the school and the teacher constitute the external restraint system. Figure 7 shows the intensity of external constraints: with each increase in the learning period, the family's constraints on students are gradually relaxed; meanwhile, the supervision of schools and teachers is the weakest on undergraduates and the strongest on secondary students. The contrast between the two adjacent periods is striking.

In addition, we conducted a statistical test on the relationship between "self-restraint" and "external restraint" as well as the "learning interest, learning behavior and learning consciousness" of college students (Table 1). The study duration of college students is positively correlated with self-restraint, family supervision, school supervision and teacher supervision. At the same time, self-restraint is positively correlated with learning consciousness and learning preference, while external restraint is not correlated with learning consciousness or learning preference. This means that both internal and external constraints can significantly change the learning behavior of college students from the results, but external constraints cannot change the learning preference of college students and the recognition of the importance of free time learning from the consciousness level. The lack of supervision by schools, families and teachers led to the idleness of college students during the epidemic.

Figure 7.

Statistics of family, teacher and school constraints on students during the COVID-19 crisis.

Figure 7.

Statistics of family, teacher and school constraints on students during the COVID-19 crisis.

Table 1.

Correlation test of undergraduates' "supervision" dimension and "consciousness and behavior" dimension.

Table 1.

Correlation test of undergraduates' "supervision" dimension and "consciousness and behavior" dimension.

| |

Learning time |

Learning consciousness |

Learning interest |

| Family supervision |

.323**

|

.141 |

-.009 |

| Teacher requirement |

.294**

|

.146 |

.043 |

| School requirement |

.350**

|

.124 |

.034 |

| Self requirement |

.547**

|

.296**

|

.334**

|

3.2.4. Effect dimension: Undergraduates are the most "bored" group about home life.

At the end of the questionnaire, we investigated the emotional state of the students and asked them to self-rate their satisfaction with home life during the COVID-19 crisis. Undergraduates score highest on average on boredom. The study also finds that among all respondents, undergraduates have the lowest level of self-planning, with only 35.29% of undergraduates having detailed plans, while the level of self-planning is as high as 62.1% in primary school and 72.4% in secondary school. While 11.76% of undergraduates are unplanned during their stay at home, the proportion is 10.5% of primary school students and only 5.11% of secondary school students. In addition, according to the data above, undergraduates are also the ones who spend the most time using electronic products. The study of Wang et al. [

23] on the correlation among leisure boredom, free-time management and internet addiction largely supports and explains some of the findings of this study. Leisure boredom was revealed to play a role as a distinct mediator between free-time management and internet addiction. Finally, in the evaluation of satisfaction, the average score of undergraduates was lower than that of primary and secondary school students in the evaluation of the degree of home-based academic progress and home-based academic satisfaction. The statistical test shows that there is a significant positive correlation between the degree of academic progress of undergraduates at home and external supervision and personal planning, and the greater the progress is, the higher the satisfaction.

Comprehensive survey results showed that compared with other periods, during the COVID–19 lockdown, during which time students studied at home, undergraduates presented the following characteristics: they were far from the time management level of the best groups, they had the weakest learning consciousness, they had learning the shortest duration and lowest level of self-planning, they took the longest entertainment breaks, they relied on the most electronic products, and they reported the most boredom and emptiness. How do these behaviors come about? What is the relationship between these students’ attitudes and behaviors towards COVID-19? The next stage of the interview research will explain this.

3.3 Mechanism of behavior formation

According to the previously formed analysis framework, the interview results were categorized and sorted. The results show that there are respondents in all four quadrants. Based on the evidence presented in the interview content, the interaction mechanism between a student’s behavior and thought can be analysed. We marked the analytical themes in the excerpts: past holiday home experience (Theme 1), current home activities (Theme 2), and knowledge of COVID-19 crisis events (Theme 3).

3.3.1. High self-management oriented by social responsibility

The first quadrant is the most ideal. Students belonging to this quadrant can view the COVID-19 crisis in terms of social responsibility and can translate social responsibility into self-management efforts to plan their studies and life while at home.

Our high school was quite relaxed; teachers used to emphasize hard work and social practice after entering college and never gave us too much homework. In the rest time, I would find some more difficult tasks to do by myself, to make up for the subjects I am not good at (Theme 1). During the pandemic, I worked remotely from home. At other times, I’d take online classes. I also arranged to study English for about three hours a day, and I reserved one hour for exercise (Theme 2). The pandemic made me realize how little I was contributing to society by being in school all the time. My teacher did not rest during the lockdown but was doing research on infectious diseases. I hope I can also study issues such as telecommuting to address social needs (Theme 3).【2-Literature】

My plan detailed how much I would accomplish each day, each week, and where I would be at the end of the vacation. I go to bed almost every night at 12 o'clock and get up at 7:30. Read English first, then read books, then do English papers, practice professional courses in the afternoon. Study for at least five or six hours during the day and do something entertaining for up to two hours (Theme 2). When I was in secondary school, my family hardly pressured me. We didn't have much homework in school, and our teachers gave us a lot of time for self-study to arrange by ourselves. I have always been in the habit of making plans (Theme 1). I think the epidemic is related to everyone's responsibility. I have gained a better understanding of society and human nature. I myself must practice good hygiene, not eat game. I am very sympathetic to the patients and grateful to the doctors. When I think of the doctors and nurses infected, I feel very sad. (Theme 3).【13-Art】

Both of the above two undergraduates had detailed and substantial plans during the home lockdown during the COVID-19 epidemic, which were spontaneous, autonomous and completed through self-supervision. They also had past experiences in common. The relatively relaxed and autonomous learning environment in secondary school became fertile ground for the cultivation of autonomous learning ability. This study habit carried over into college, where their lockdown period was stable and fulfilling. At the same time, both respondents showed varying degrees of social responsibility for the COVID-19 crisis. It is worth noting that when interviewee 2 talked about high school teachers, the high school teachers' descriptions and attitudes towards the university fell into "further study" and "social practice", which may have had an impact on the student's behavior and social responsibility during his undergraduate period.

3.3.2. Low self-management oriented by social responsibility

The students belonging to the second quadrant also have strong social concepts, but their self-restraint, self-planning and self-management ability is insufficient. These students showed a good sense of social responsibility during the pandemic but were reluctant to engage in hard work and active self-management.

Secondary school teachers all over the country are the same, coaxing their current students, saying that if they do well on the college entrance examination, they will not have to study anymore. In the past, the teachers of each subject would assign a lot of papers, but I did not write them until the beginning of the semester (Theme 1). During the COVID-19 epidemic, I didn't have any homework. From the first day of the Chinese New Year to the seventh day of the Chinese New Year, I was playing with my mobile phone. Then, I thought I couldn't be lazy anymore, so I made the video of my volunteer teaching in Guizhou last year. Now, it seems that the progress during the holiday is still very small (Theme 2). At the beginning of the epidemic, I was quite calm. But lately, the epidemic is getting worse and worse, and whenever I see people dying on the news, I ask myself, "Is there really nothing I can do?" If I had one day left to live, I would regret that I haven't done a lot for my family, for my country. It makes me think that the most important thing at present is to do well what I should do, work harder to finish school, and then pursue a contribution to the country (Theme 3).【11-Engineering】

Based on this respondent's anxiety about social events, his thinking about his self-worth, and his volunteer teaching experience in Guizhou Province, China, we can basically see that he is a student with a strong sense of social responsibility. However, different from the previous two interviewees, although the student also considered the problem from the perspective of social needs, he spontaneously realized he should " do well what I should do" but could not implement it well. The reason goes back to high school. High school learning was passive, and he did not develop the habit of planning on his own. Therefore, in college, when faced with a large amount of free time, he seemed at a loss. In addition, the respondent was also asked about his future plans. "I knew it was time to make a life choice, but I never considered it," he replied. Therefore, there is an urgent need to implement ability education for such students.

3.3.3. Low self-management dominated by personal emotion

Students in the third quadrant tend to view the COVID-19 crisis more in terms of personal feelings and gains and losses. In terms of specific behaviors, they show obvious external dependence and lack of responsibility for their own life and social responsibilities. The following interviewee recounted her experience.

I never had any time to myself during the high school holidays. There is endless homework every day. Get up at eight or nine in the morning, wash and begin to do homework, and continue to write after lunch. I go to bed at one or two in the morning and get on with my work the next day. I worked hard in secondary school because exams and homework chased me like a dog, and I didn't dare stop. However, my heart was in agony. Secondary school teachers used to tell us, "As long as you get into a key university, you don't need to work so hard. All you have to do is pass the exam." (Theme 1) Now I want to be as indulgent as possible. I sleep about 12 hours a day, watch 12 hours of TV, and check my phone and Twitter when I'm bored (Theme 2). I'm glad the pandemic has extended the holiday. Because I didn't bring any books back, I just finished a teacher's paper. My only concern is that my experiment might be delayed by the pandemic (Theme 3).【1-Medicine】

The interviewee described her past and present learning experiences in detail, explaining she never had time to spare. Secondary school teachers always try to let students know that getting into a famous university means a lifetime of success. This respondent represents a group of students who have grown up under excessive academic burden and have maintained a utilitarian attitude towards life oriented towards tests and scores. In the face of global crises such as COVID-19, they are more focused on their learning and gains and losses. The students themselves are not entirely to blame for this phenomenon. It is not difficult to see from the interview that a results-oriented teaching model, an over-constrained management model and an inappropriate positioning of secondary school and university education all lead to a distance between secondary school and society and lead students to lack initiative and a plan for their life at the macro level. According to this approach, everything is based on tests, graduation, and GPA. This topic requires special vigilance.

3.3.4. High self-management dominated by personal emotion

Many undergraduates are concentrated in the fourth quadrant. Students in this quadrant are the opposite of those in the second quadrant. They are responsible for their behavior at home, but they do not think they can make any contribution to the COVID-19 crisis.

Ever since I was a child, during the holidays, I would mix my teacher's tasks with what I had to learn. Study at the local library during the day and come home at night to dig into physics. I think studying is my own business (Theme 1). I always had a study plan in college. During the pandemic, I took online algorithms courses from TOEFL and Stanford. I also worked from home as an intern at a consulting firm (Theme 2). Lockdown due to COVID-19 has left me in a bad mood and unable to find joy in life. It exacerbated my negative emotions and feelings of loss. When I feel powerless, I wonder why I am still alive and feel depressed, as if I am living for the fear of death (Theme 3).【8-Science】

This time every morning, I insist on getting up at eight o'clock, reading books until about ten o'clock, and then beginning to learn professional courses, memorizing words and writing articles. During my stay at home, I have a plan every day, combining work and rest, and constantly explore which arrangement is best for me (Theme 2). When I was in secondary school, I didn't study as hard as now. At that time, I didn't have much homework, but my mother would ask me to make plans for myself and supervise my execution (Theme 1). Now I have to stay at home for so long without peer communication, so I was a little nervous at first. Now I feel calmer. However, as for the COVID-19 crisis, some measures taken by society for the epidemic, I don't think it has a great impact on me, and I am mainly resigned to my fate and can do nothing (Theme 3).【12-Literature】

According to the description of the two interviewees, they not only formed the habit of planning for themselves on the micro level but also had clear goals for their life on the macro level. These undergraduates had strong self-control and made good use of their spare time to make progress. However, compared with first-quadrant students, they had a more relaxed environment in their secondary school experience. The habits in their independent studies were formed in the past. However, the difference lies in social responsibility. When asked about their views or feelings about the COVID-19 crisis, they only described subjective feelings and expressed a strong sense of powerlessness. However, during the pandemic, each individual has a responsibility to understand that one’s own decisions necessarily have an impact on other people. Young college students in particular should strengthen their sense of social responsibility (Pierluigi et al., 2021). Therefore, undergraduates in this category are not lacking in action but need to link personal efforts and professional learning with social responsibility.

4. Discussion

At the stage of the questionnaire survey, we found that first, the behavior of undergraduates is restricted by both self-restraint and external supervision, and effective planning or constraint has a direct and obvious effect on behavior. Second, consciousness also has an impact on behavior. The influence of various elements in the dimension of consciousness on behavior is complex and indirect. According to the analysis of the interview research, in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, the values of undergraduates should also be taken as one of the secondary indicators of consciousness combined with the empirical research results of the first two stages. In Figure 8, the connected arrows represent the association between elements, ++ represents the direct association, and + represents the indirect association. behavior is the core. Consciousness and supervision work together on behavior to produce effects, including subjective self-satisfaction and objective degree of progress.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of the formation of undergraduates' behavior during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of the formation of undergraduates' behavior during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Previous studies have confirmed that values have a driving effect on behavioral activities and that motivation plays a mediating role between self-management and self-monitoring [

12]. This study found that a large number of undergraduates lack a sense of social responsibility and have a weak motivation to learn after entering college, which leads to poor self-monitoring ability and difficulty in efficient self-management in their leisure time. Therefore, the self-management level is declining instead of rising. Although effective and direct time management training is an effective way to change behavior and habits [

43,

44], the interview results show that the root of the problem often dates back to secondary school. What kind of study pressure students experienced in secondary school, how teachers positioned the college entrance examination, and how college life was described to students, to a large extent, determine whether students are willing to work hard after entering college and for what purpose and then influence students' values in a subtle way. This study reflects the sense of responsibility during the COVID-19 crisis. Therefore, the root of the problem should be found in students' past experience and the process of cognition formation. Efforts should be made in adolescence, focusing on the formation of correct values while shaping behavior. As far as the cultivation of undergraduates is concerned, not only the education of professional knowledge and skills but also the recognition of professional value and personal value of undergraduates should be taken into account. In the dimension of consciousness, students' values will go through the first level of transformation; that is, "values" will be transformed into "awareness of professional learning". At this level, many undergraduates suffer from poor transformation. In the context of a major event such as an epidemic, the high daily rate of new cases and deaths and the information citizens release through the media can lead to psychological pressure [

45,

46]. In interviews, we also found that many students expressed feelings of powerlessness, anger at hearing negative news, and anxiety about their delayed graduation. Lockdown measures, while successful in slowing the spread of infection by maintaining distance between people [

47], can also increase the social isolation of students and affect their mental health [

48,

49], leaving them at the mercy of their emotions. However, the research found that the subjective emotions caused by the lockdown environment are not the sole reason for students' boredom, low productivity and lack of responsibility. In regard to their major, quite a few students first think about their credits, GPA, job prospects, etc. The failure to recognize the correlation between individual academic efforts and crisis events is the root cause of students' feelings of powerlessness, helplessness and boredom in the face of major social events.

It is not enough to have the right values and a high sense of responsibility. In this study, we found that students with low self-management (second quadrant) oriented by social responsibility have a mismatch between consciousness and behavior or a poor transformation of consciousness into behavior. This is because the transformation of the "second layer" between the dimensions of consciousness and behavior (

Figure 8) is recognized by many researchers as a difficulty. Wang et al. [

4] conducted an empirical study on undergraduate free time management, including four general dimensions: goal setting and evaluation, technique, free time attitudes, and scheduling. The analysis showed that undergraduates consciously recognize the value of free time and agree that it is of great significance to arrange spare time reasonably, but they do not know how to put it into action or how to deal with and use their spare time.

According to the interviews conducted in this study, students with high self-management ability (quadrants 1 and 4) have a common point in that they used to be in a relatively autonomous learning environment in secondary school. After entering university, they can not only adapt to a relatively free learning environment but also efficiently plan and use their free time. For a considerable number of undergraduates who lack self-management experience and ability, colleges and universities have the responsibility to make up lessons for freshmen, establish leisure education in the form of courses, and guide students step by step on how to manage their spare time and how to engage in self-planning from the perspective of behavior.

5. Conclusions

The research shows that compared with primary and secondary school students, undergraduates have many problems with self-time management. These problems mainly include weak learning consciousness and low interest; excessive recreation, especially with electronic products encroaching on learning time; relatively insufficient external supervision; and subjective feelings of boredom and dissatisfaction with their free time life. Through semistructured interviews, it was found that the education that undergraduates received in secondary school, including training in self-time management and the value education they received, greatly influences their behavior after entering the university-whether they slack off or engage in strict self-management. On the other hand, the perception of the value of their major affects their sense of social responsibility, which is reflected in their motivation to study hard in the face of global crisis events such as COVID-19. Therefore, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, undergraduates' behavior during lockdown is a complex problem that is the result of multiple factors, such as past experiences with professional identity behavior habits.

The study also found that undergraduates who spent secondary school in a relaxed learning environment, whose teachers placed more emphasis on sustained effort, and who entered college with a strong sense of the social value of their major worked harder and fulfilled more during the pandemic. In contrast, students who were chronically under high academic pressure and used to passive learning in secondary school, whose teachers only emphasized current efforts and predicted college to be an environment where they could indulge, and who did not recognize the social value of their undergraduate major were more likely to slack off and be passive during the pandemic.

Therefore, it is suggested that the learning pressure in secondary school should not be too great and that students should be given a relatively autonomous learning environment and self-time management guidance when necessary. Secondary school teachers and university teachers should also establish consistency in their understandings, including regarding the description of university life and the value of undergraduate study. A consistent understanding is conducive to a continuous effort in student education, while inconsistent understandings will cause students to become confused after entering the university.

In universities, undergraduate teaching should not one-sidedly emphasize professional knowledge and skills while ignoring students' recognition of professional identity and social value. Only when undergraduates realize the value of their major in social development will they experience not only subjective emotions but also global consciousness when facing a global crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. More importantly, this kind of value will be transformed into a recognition of one's own profession, an awareness of self-management and a motivation for learning. The discussion in this study on how to transform college students' values into self-management behavior is insufficient. The subsequent research focus on the formation mechanism of self-management behavior and explore the deeper correlation between values and self-management behavior. Another limitation of the research is that the research on the formation of students' values is not sufficient, which is mainly analyzed and discussed through the middle school experiences mentioned in the interview. However, besides the explicit perception and mentioned experiences of students themselves, whether there are other factors affecting the formation of values needs to be further discussed in the context of the growth environment of college students. On this basis, individualized intervention plans are developed according to students’ actual situations (e.g., according to the different categories represented by quadrants 2, 3, and 4).

Funding

This research was funded by The National Social Science Foundation[21CYY017].

Informed Consent Statement

Each participant or their parents signed an informed consent form approved by the Ethical Committee of Shanghai Normal University before taking part in this experiment, and then received payment for participation after completing the experiment.

Data Availability Statement

All data included in this study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Zeijl, E.; Bois-Reymond, M.D.; Poel, Y.T. Young adolescents' leisure patterns. Loisir Et Société, 2001; 24, 379–402. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.D. Developmental Psychology, 3rd ed.; People's Education Press: Beijing, China, 2003; pp. 474–512. [Google Scholar]

- Bolden, J.; Fillauer, J.P. "Tomorrow is the busiest day of the week": Executive functions mediate the relation between procrastination and attention problems. J Am Coll Health 2020, 68, 854–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.C.; Kao, C.H.; Huan, T.C.; Wu, C.C. Free time management contributes to better quality of life: a study of undergraduate students in Taiwan. Journal of Happiness Studies 2011, 12, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertuğ, N.; Faydali, S. Investigating the Relationship Between Self-Directed Learning Readiness and Time Management Skills in Turkish Undergraduate Nursing Students. Nursing education perspectives 2018, 39, E2–E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrison, D.R. Self-directed learning: Toward a comprehensive model. Adult Education Quarterly 1997, 48, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolina, R.-H.; Judit, F.N.; Concepció, F.P.; Angel, R.C.; Dalmau, V.V.; David, B.F. Measuring self-directed learning readiness in health science undergraduates: A cross-sectional study. Nurse education today 2019, 83, 104201. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, H.; Cook, A. Mind the gap: are students prepared for higher education? Journal of Further and Higher Education 2003, 27, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, S.; Evans, S.E.; Dyas, L. Approaches to learning: a study of first-year geography undergraduates. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 2001, 25, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, A.; Simpson, E. Effective student motivation commences with resolving ‘dissatisfiers’. Journal of Further and Higher Education 2004, 28, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, S.J.; Dollard, M.F.; De Jonge, J. Stress and Student Job Design: Satisfaction, Well-Being, and Performance in University Students. International Journal of Stress Management 2002, 9, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-El-Fattah, S.M. Garrison's model of self-directed learning: preliminary validation and relationship to academic achievement. The Spanish journal of psychology 2010, 13, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauknerova, D.; Jarosova, E.; Lhotanova, T. Self management skills and subjective well being among undergraduate university students. International Journal of Psychology 2016, 51, 511–511. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meer, J.; Jansen, E.; Torenbeek, M. It’s almost a mindset that teachers need to change: first year students’ need to be inducted into time management. Studies in Higher Education 2010, 35, 777–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marta, A. ; Thanasis, D; Fatos, Xhafa. Analyzing the effects of emotion management on time and self-management in computer-based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 2016; 63, 517–529. [Google Scholar]

- Dolu, G. Are Science Education Students Sufficiently Aware of "COVID-19"? International Online Journal of Educational Sciences 2021, 13, 824–837. [Google Scholar]

- Khatatbeh, M.; Khasawneh, A.; Hussein, H.; Altahat, O.; Alhalaiqa, F. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic Among the General Population in Jordan. Frontiers in psychiatry 2021, 12, 618993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turk, F.; Kul, A.; Kilinc, E. Depression-anxiety and coping strategies of adolescents during the Covid-19 pandemic. Turkish Journal of Education 2021, 10, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gębska, M.; Kołodziej, Ł.; Dalewski, B.; Pałka, Ł.; Sobolewska, E. The Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Stress Levels and Occurrence of Stomatoghnatic System Disorders (SSDs) among Physiotherapy Students in Poland. Journal of clinical medicine 2021, 10, 3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, J.C. A comprehensive plan for the wise use of leisure. In Leisure in America: Blessing or curse, 1st ed.; Charlesworth, J.C., Ed.; American Academy of Political Social Science: Philadelphia, American, 1964; pp. 30–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.C.; Wu, C.C.; Wu, C.Y.; Huan, T.C. Exploring the relationships between free-time management and boredom in leisure. Psychological reports 2012, 110, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.C. Exploring the Relationship Among Free-Time Management, Leisure Boredom, and Internet Addiction in Undergraduates in Taiwan. Psychological reports 2019, 122, 1651–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, J.L.; Cairns, B.D.; Farmer, T.W. Promoting interpersonal competence and educational success through extracurricular activity participation. Journal of Educational Psychology 2003, 95, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, K.M.; Werner-Wilson, R.J. The relationship between out-of-school activities and positive youth development: An investigation of the influences of communities and family. Adolescence 2005, 40, 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J.S.; Templeton, J. Chapter 4: Extracurricular and Other After-School Activities for Youth. Review of Research in Education 2002, 26, 113–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardi, A.; Schwartz, S.H. Values and behavior: strength and structure of relations. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2003, 29, 1207–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cieciuch, J.; Roccas, S.; Sagiv, L. Values and Behavior: Taking a Cross-Cultural Perspective, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlović, Z; Ilić, I.S. Basic values as predictors of leisure-time activities among adolescents. Primenjena Psihologija, 2022; 15, 85–117.

- Rechter, E.; Sverdlik, N. Adolescents' and teachers' outlook on leisure activities: personal values as a unifying framework. Personality & Individual Differences, 2016; 99, 358–367. [Google Scholar]

- Maio, G.R. The psychology of human values, 1st ed.; Psychology press: London, UK, 2017; pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 1992, 25, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Stepanović, I.; Videnović, M.; Plut, D. Obrasci ponašanja mladih tokom slobodnog vremena. Sociologija 2009, 51, 247–261. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, J.L.; Lynn, M.; Stiles, D.A. Cross-national gender differences in adolescents' preferences for free-time activities. Cross-Cultural Research, 1997; 31, 5–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sivan, A.; Tam, V.; Siu, G.; Stebbins, R. Adolescents’ Choice and Pursuit of Their Most Important and Interesting Leisure Activities. Leisure Studies 2019, 38, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaabane, S.; Doraiswamy, S.; Chaabna, K.; Mamtani, R.; Cheema, S. The Impact of COVID-19 School Closure on Child and Adolescent Health: A Rapid Systematic Review. Children (Basel) 2021, 8, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, D.C.; Ramage, K.; Moore, S.A.; Riazi, N.; Tremblay, M.S.; Faulkner, G. Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on the movement behaviors of children and youth: A scoping review of evidence after the first year. Journal of sport and health science 2021, 10, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.; Cosma, A.; Svacina, K.; Boniel-Nissim, M.; Badura, P. Czech adolescents' remote school and health experiences during the spring 2020 COVID-19 lockdown. Preventive medicine reports 2021, 22, 101386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, E. Undergraduate students’ attitudes to COVID-19 during the lockdown period: Hierarchy of psychological factors. European Psychiatry 2021, 64, S265–S265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakoc, K.; Karabulut, M.; Ozcan, E.K.; Mujdeci, B. Audiology students' opinions towards COVID-19 pandemic: occupational perspective and future expectations. Hearing Balance and Communication 2022, 20, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.P.; Joseph, A.O.; Conn, G.; Ahsan, E.; Jackson, R.; Kinnear, J. COVID-19 Pandemic-Medical Education Adaptations: the Power of Students, Staff and Technology. Medical science educator 2020, 30, 1355–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldridge, M.D.; McQuagge, E. "Finding My Own Way": The lived experience of undergraduate nursing students learning psychomotor skills during COVID-19. Teach Learn Nurs 2021, 16, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairney-Hill, J.; Edwards, A.E. ; Jaafar, N; Gunganah, K.; Macavei, V.M.; Khanji, M.Y. Challenges and opportunities for undergraduate clinical teaching during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. J R Soc Med, 2021; 114, 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, M.M.; Califf, M.E. An assessment of the impact of time management training on student success in a time-intensive course. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 2007; 18, 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Tabvuma, V.; Carterrogers, K.; Brophy, T.; Smith, S.M.; Sutherland, S. Transitioning from in person to online learning during a pandemic: an experimental study of the impact of time management training. Higher Education Research & Development, 2021; 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, L.; Zhu, G. Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Zheng, P.; Jia, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Fu, H.; Dai, J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PloS one 2020, 15, e0231924. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hou, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res, 2020; 287, 112934. [Google Scholar]

- Odriozola-González, P.; Planchuelo-Gómez, Á.; Irurtia, M.J.; de Luis-García, R. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatry research 2020, 290, 113108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.A. Novel Approach of Consultation on 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19)-Related Psychological and Mental Problems: Structured Letter Therapy. Psychiatry investigation 2020, 17, 175–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).