Submitted:

09 August 2023

Posted:

10 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wild Mallards Fecal Sample Collection

2.2. Domestic Mallards Fecal Sample Collection

2.3. Fecal DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

2.4. Mixing and Purification of PCR Products

2.5. Libraries Generated and IIIumina NovaSeq Sequencing

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

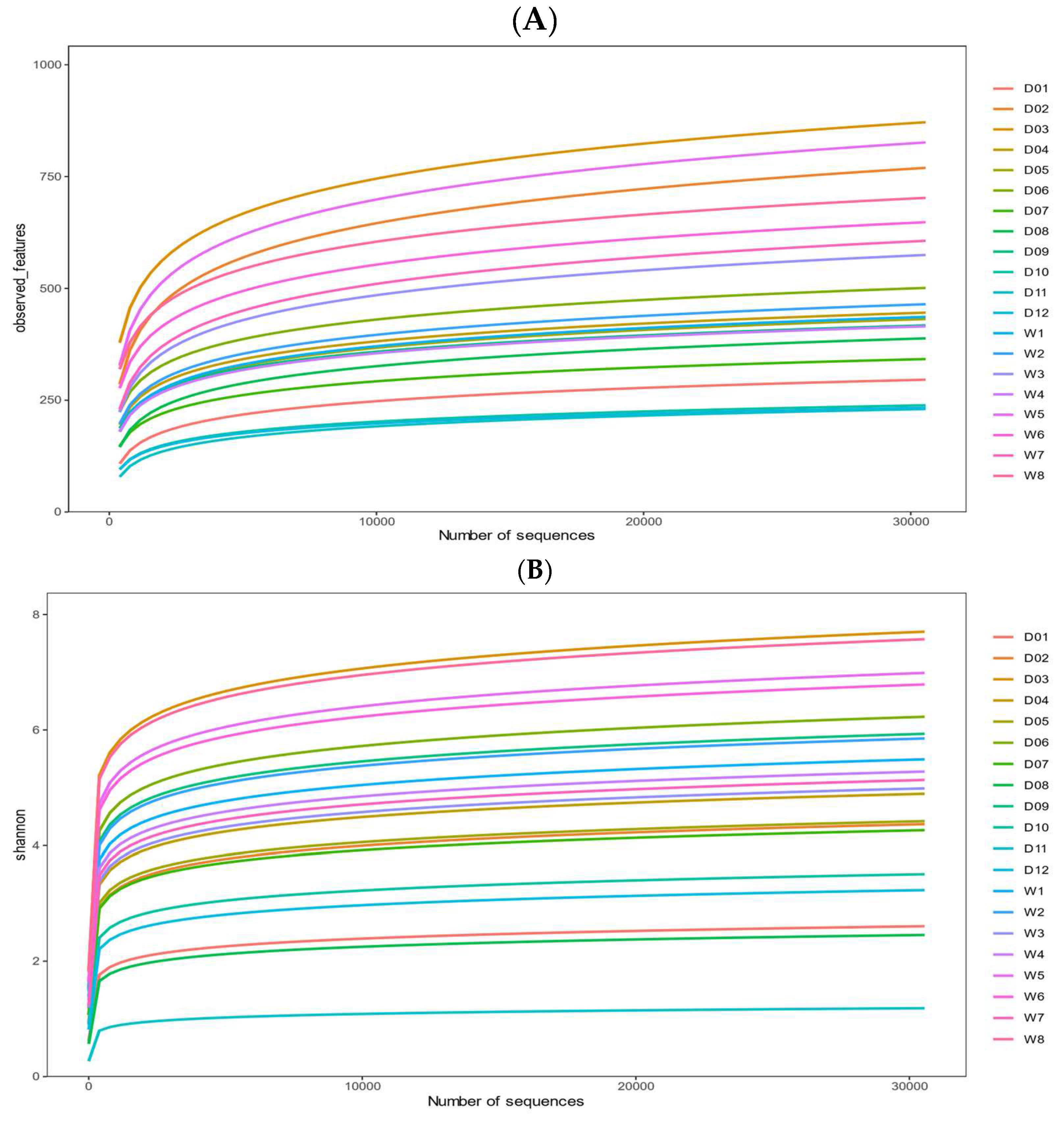

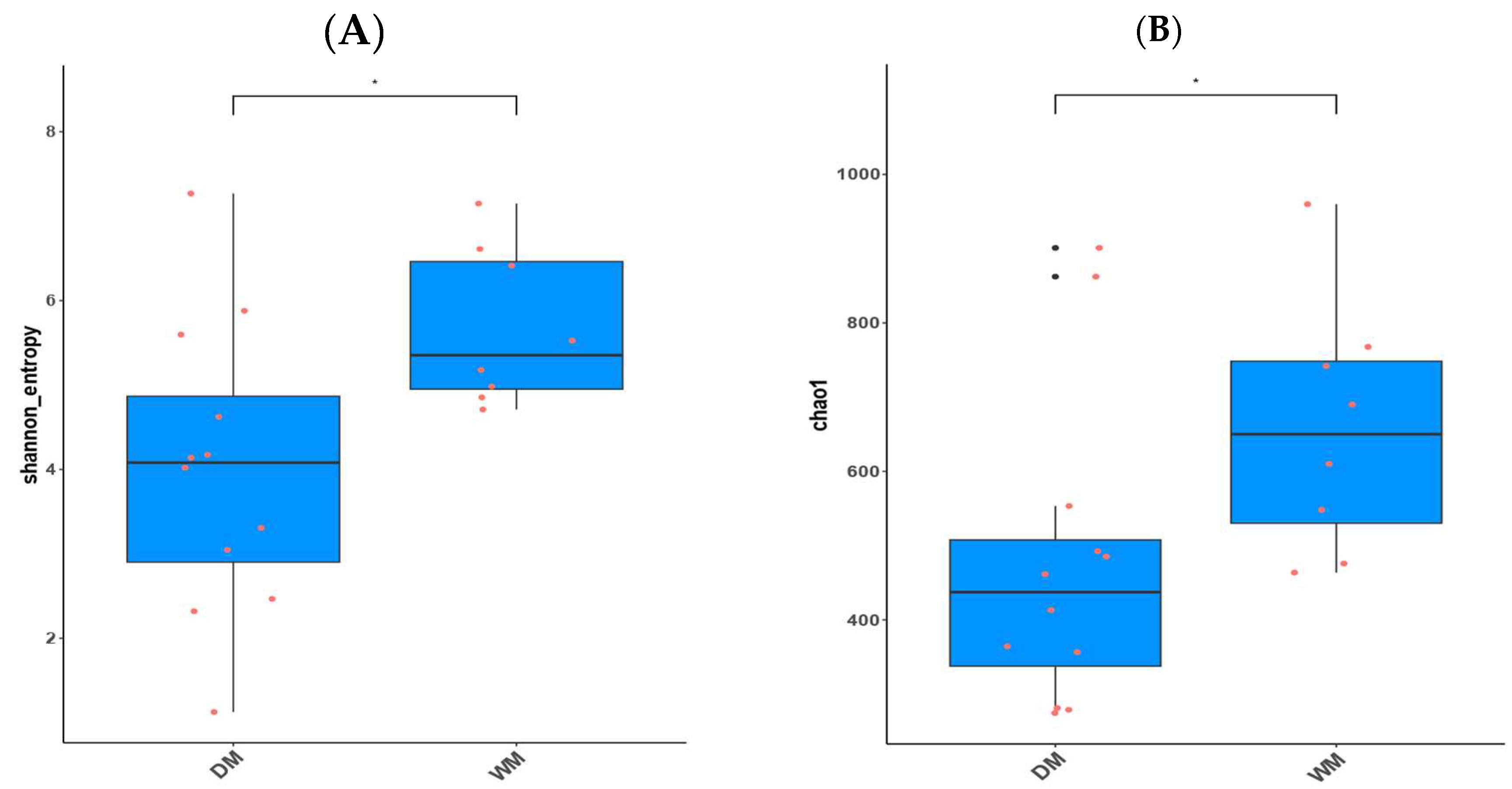

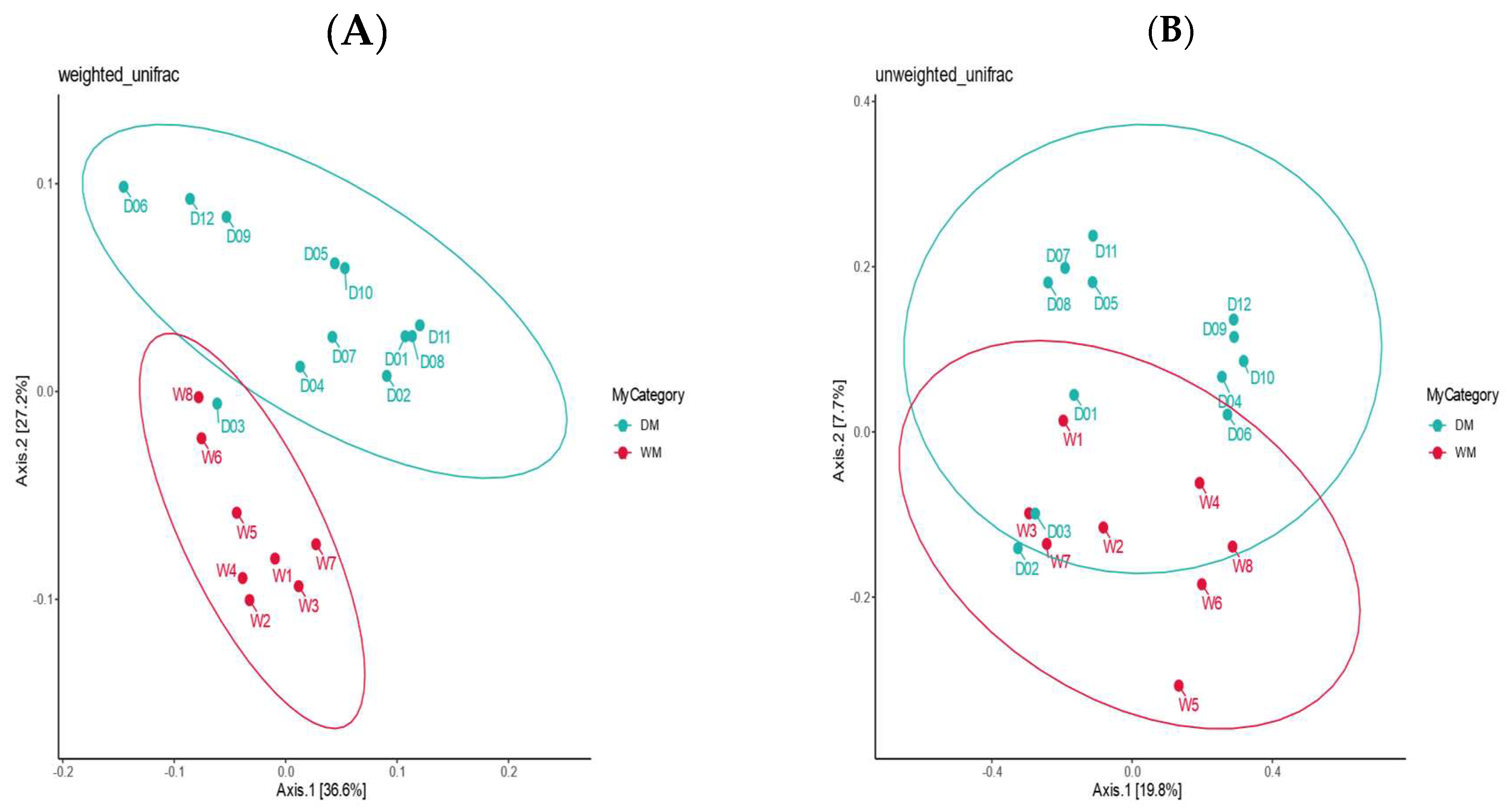

3.2. Alpha Diversity and Beta Diversity Analyses

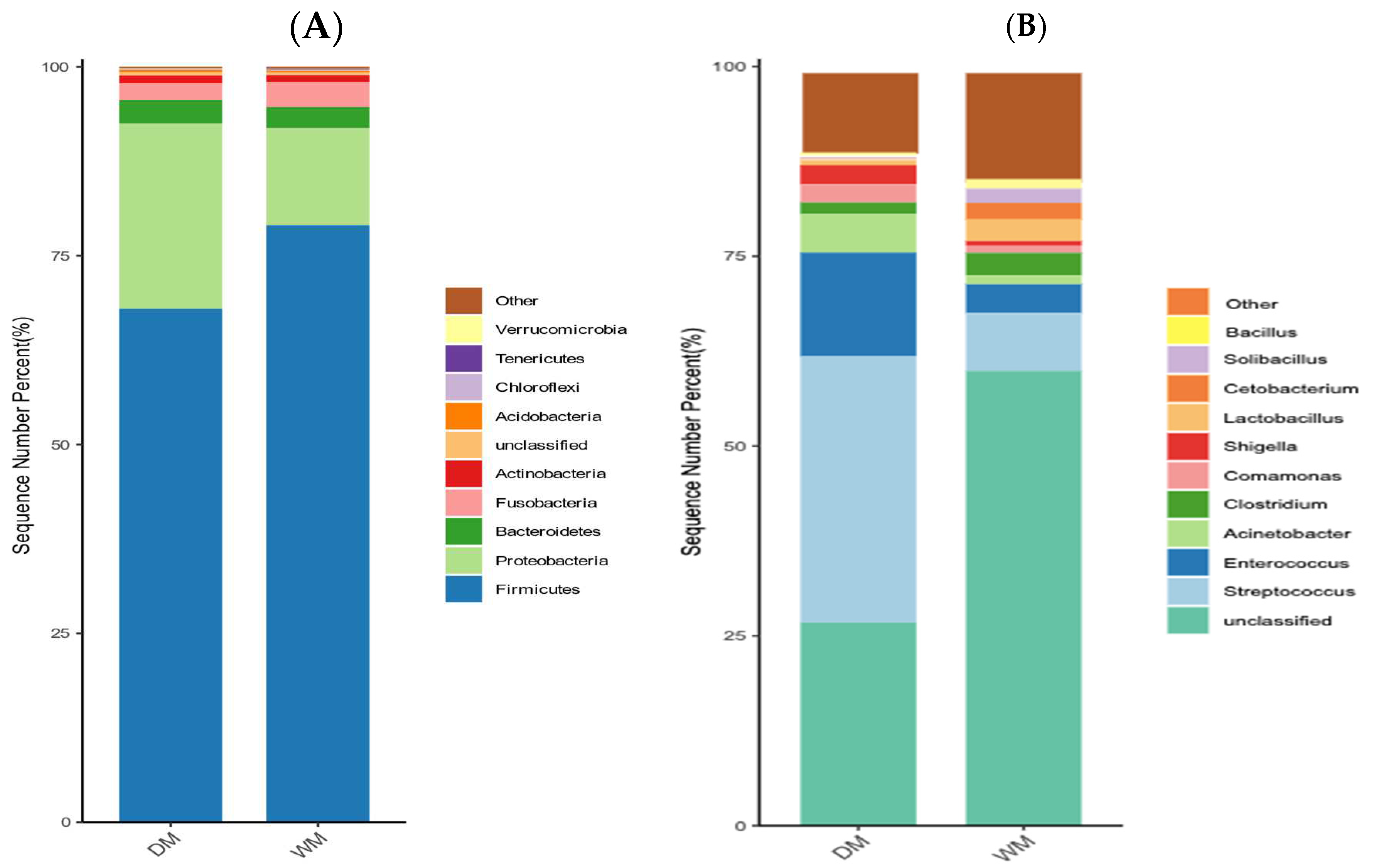

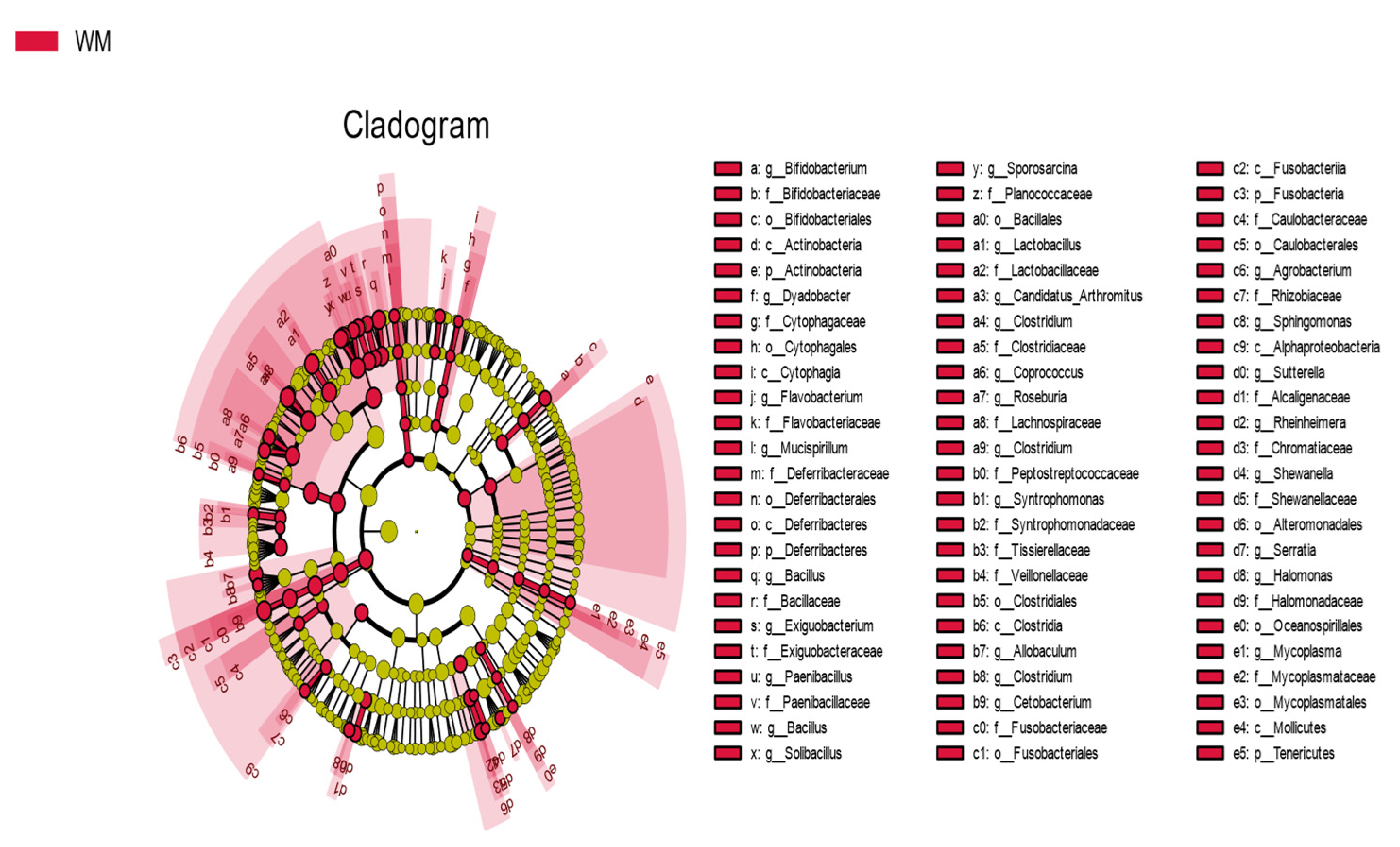

3.3. Comparison of The Intestinal Microflora of Two Groups of Mallards at The Phylum and Genus Levels

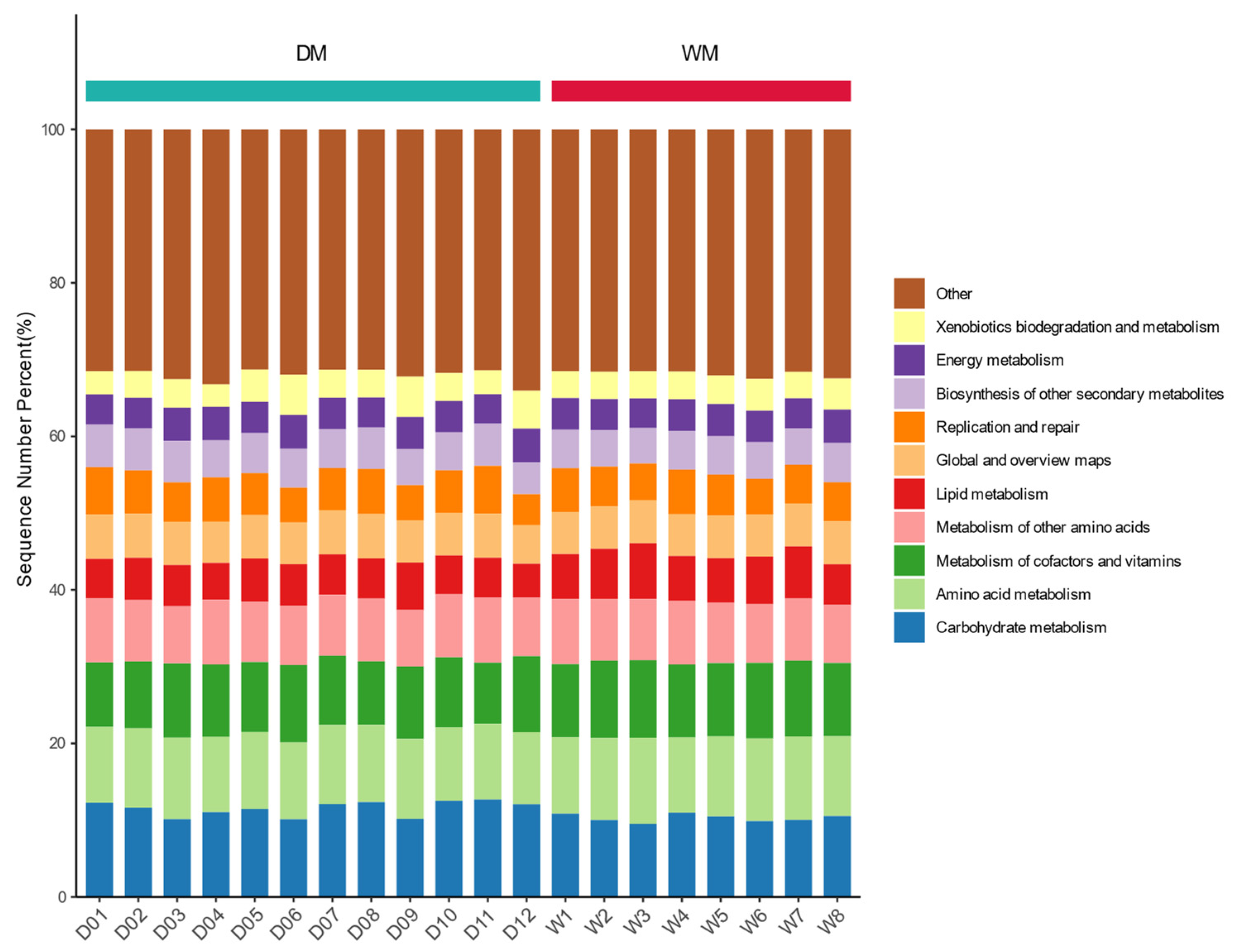

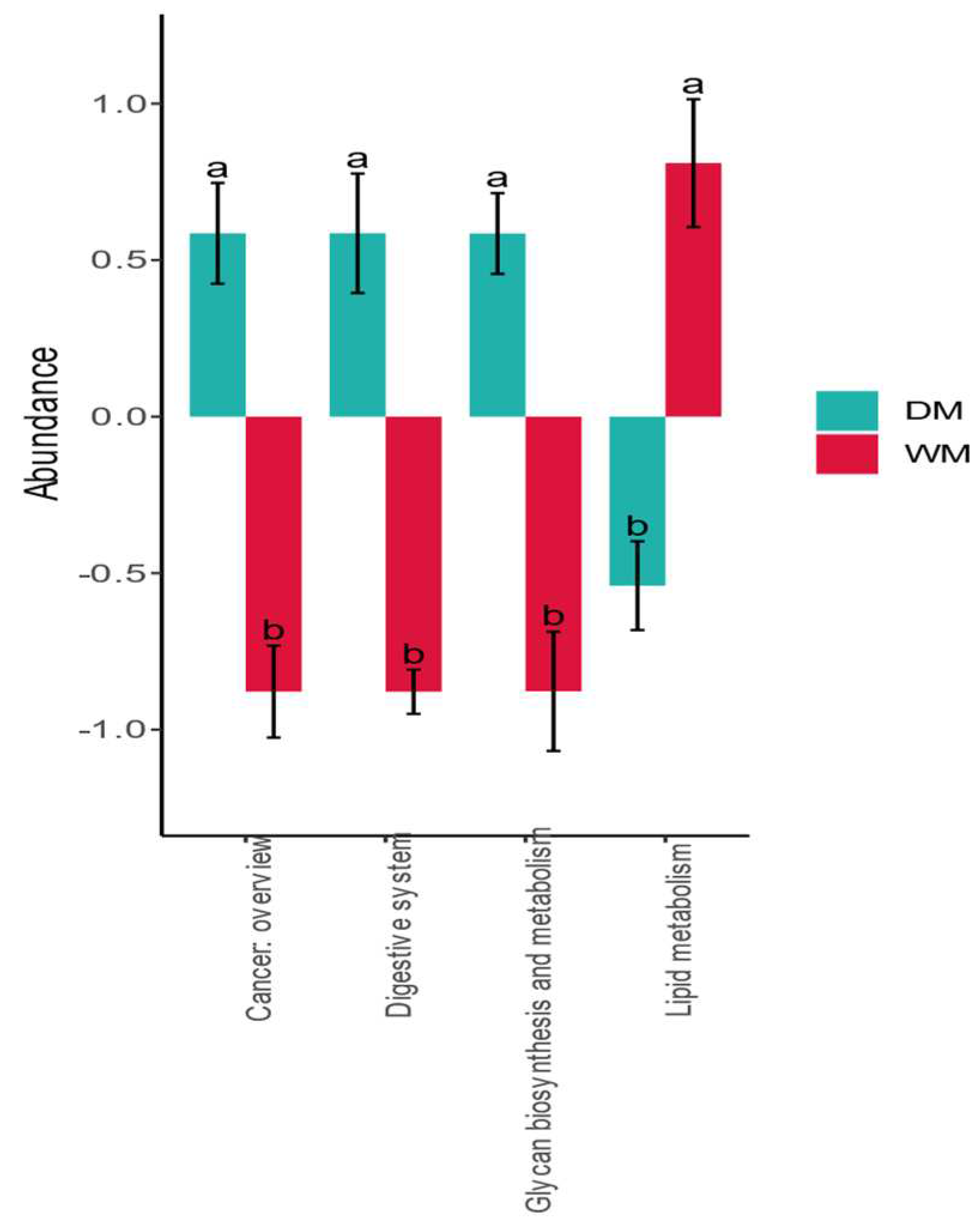

3.4. Prediction of Gut Microbiome Function

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grond, Kirsten.; Sandercock, Brett K.; Jumpponen, Ari.; Zeglin, Lydia H. The avian gut microbiota: community, physiology and function in wild birds. Journal of Avian Biology. 2018. 49(11). [CrossRef]

- Wu, Gary D.; Chen, Jun.; Hoffmann, Christian.; Bittinger, Kyle.; Chen, Ying-Yu.; Keilbaugh, Sue A.; Bewtra, Meenakshi.; Knights, Dan.; Walters, William A.; Knight, Rob.; et al. Linking Long-Term Dietary Patterns with Gut Microbial Enterotypes. Science. 2011. 334(6052): p. 105-108.

- 3. Turnbaugh, Peter J.; Gordon, Jeffrey I. The core gut microbiome, energy balance and obesity. Journal of Physiology-London. 2009. 587(17): p. 4153-4158.

- Margolis, Kara Gross.; Gershon, Michael David.; Bogunovic, Milena. Cellular Organization of Neuroimmune Interactions in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Trends in Immunology. 2016. 37(7): p. 487-501. [CrossRef]

- Ahern, Philip P.; Faith, Jeremiah J.; Gordon, Jeffrey I. Mining the Human Gut Microbiota for Effector Strains that Shape the Immune System. Immunity. 2014. 40(6): p. 815-823. [CrossRef]

- Sanmiguel, Claudia.; Gupta, Arpana.; Mayer, Emeran A. Gut Microbiome and Obesity: A Plausible Explanation for Obesity. Current obesity reports. 2015. 4(2): p. 250-61. [CrossRef]

- Pevsner-Fischer, Meirav.; Tuganbaev, Timur.; Meijer, Mariska.; Zhang, Sheng-Hong.; Zeng, Zhi-Rong.; Chen, Min-Hu.; Elinav, Eran. Role of the microbiome in non-gastrointestinal cancers. World journal of clinical oncology. 2016. 7(2): p. 200-13. [CrossRef]

- Forslund, Kristoffer.; Hildebrand, Falk.; Nielsen, Trine.; Falony, Gwen.; Le Chatelier, Emmanuelle.; Sunagawa, Shinichi.; Prifti, Edi.; Vieira-Silva, Sara.; Gudmundsdottir, Valborg.; Pedersen, Helle Krogh.; et al. Disentangling type 2 diabetes and metformin treatment signatures in the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2015. 528(7581): p. 262-+.

- Montiel-Castro, Augusto J.; Gonzalez-Cervantes, Rina M.; Bravo-Ruiseco, Gabriela.; Pacheco-Lopez, Gustavo. The microbiota-gut-brain axis: neurobehavioral correlates, health and sociality. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience. 2013. 7: p. 70-70. [CrossRef]

- Prum, Richard O.; Berv, Jacob S.; Dornburg, Alex.; Field, Daniel J.; Townsend, Jeffrey P.; Lemmon, Emily Moriarty.; Lemmon, Alan R. A comprehensive phylogeny of birds (Aves) using targeted next-generation DNA sequencing. Nature. 2015. 526(7574): p. 569-U247. [CrossRef]

- Alexandra Garcia-Amado, M.; Shin, Hakdong.; Sanz, Virginia.; Lentino, Miguel.; Margarita Martinez, L.; Contreras, Monica.; Michelangeli, Fabian.; Dominguez-Bello, Maria Gloria. Comparison of gizzard and intestinal microbiota of wild neotropical birds. Plos One. 2018. 13(3). [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rodriguez, Magdalena.; Martin-Vivaldi, Manuel.; Martinez-Bueno, Manuel.; Jose Soler, Juan. Gut Microbiota of Great Spotted Cuckoo Nestlings is a Mixture of Those of Their Foster Magpie Siblings and of Cuckoo Adults. Genes. 2018. 9(8).

- Eckburg, PB.; Bik, EM.; Bernstein, CN.; Purdom, E.; Dethlefsen, L.; Sargent, M.; Gill, SR.; Nelson, KE.; Relman, DA. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science. 2005. 308(5728): p. 1635-1638. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Yuzhan.; Deng, Ye.; Cao, Lei. Characterising the interspecific variations and convergence of gut microbiota in Anseriformes herbivores at wintering areas. Scientific Reports. 2016. 6. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Jiachao.; Guo, Zhuang.; Xue, Zhengsheng.; Sun, Zhihong.; Zhang, Menghui.; Wang, Lifeng.; Wang, Guoyang.; Wang, Fang.; Xu, Jie.; Cao, Hongfang.; et al. A phylo-functional core of gut microbiota in healthy young Chinese cohorts across lifestyles, geography and ethnicities. Isme Journal. 2015. 9(9): p. 1979-1990. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Darin C.; Tun, Hein Min; Kim, Ji Eun; Leung, Frederick C.; Cheng, Kimberly M. Characterization of cecal microbiota of the emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae). Veterinary Microbiology. 2013. 166(1-2): p. 304-310. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Wen.; Zheng, Sisi.; Sharshov, Kirill.; Cao, Jian.; Sun, Hao.; Yang, Fang.; Wang, Xuelian.; Li, Laixing. Distinctive gut microbial community structure in both the wild and farmed Swan goose (Anser cygnoides). Journal of Basic Microbiology. 2016. 56(11): p. 1299-1307. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Wen.; Cao, Jian.; Li, Ji-Rong.; Yang, Fang.; Li, Zhuo.; Li, Lai-Xing. Comparative analysis of the gastrointestinal microbial communities of bar-headed goose (Anser indicus) in different breeding patterns by high-throughput sequencing. Microbiological Research. 2016. 182: p. 59-67. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Dandan.; He, Xin.; Valitutto, Marc.; Chen, Li.; Xu, Qin.; Yao, Ying.; Hou, Rong. Wang, Hairui Gut microbiota composition and metabolomic profiles of wild and captive Chinese monals (Lophophorus lhuysii). Frontiers in Zoology. 2020. 17(1).

- Xie, Yuwei.; Xia, Pu.; Wang, Hui.; Yu, Hongxia.; Giesy, John P.; Zhang, Yimin.; Mora, Miguel A.; Zhang, Xiaowei. Effects of captivity and artificial breeding on microbiota in feces of the red-crowned crane (Grus japonensis). Scientific Reports. 2016. 6. [CrossRef]

- Li, Hui-Fang.; Zhu, Wen-Qi.; Song, Wei-Tao.; Shu, Jing-Ting.; Han, Wei.; Chen, Kuan-Wei. Origin and genetic diversity of Chinese domestic ducks. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2010. 57(2): p. 634-640. [CrossRef]

- Hale, Vanessa L.; Tan, Chia L.; Knight, Rob.; Amato, Katherine R. Effect of preservation method on spider monkey (Ateles geoffroyi) fecal microbiota over 8 weeks. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2015. 113: p. 16-26. [CrossRef]

- Caterino, MS.; Cho, S.; Sperling, FAH. The current state of insect molecular systematics: A thriving Tower of Babel. Annual Review of Entomology. 2000. 45: p. 1-54. [CrossRef]

- Grond, Kirsten.; Lanctot, Richard B.; Jumpponen, Ari.; Sandercock, Brett K. Recruitment and establishment of the gut microbiome in arctic shorebirds. Fems Microbiology Ecology. 2017. 93(12). [CrossRef]

- Hird, Sarah M.; Carstens, Bryan C.; Cardiff, StevenW.; Dittmann, Donna L.; Brumfield, Robb T. Sampling locality is more detectable than taxonomy or ecology in the gut microbiota of the brood-parasitic Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater). Peerj. 2014. 2. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Shixiong.; Xu, Shijun.; Zhang, Jian.; Hussain, Riaz.; Lu, Hong.; Ye, Yourong.; Mehmood, Khalid.; Zhang, Hui.; Shang, Peng. First Report of Fecal Microflora of Wild Bar-Headed Goose in Tibet Plateau. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 2022. 8. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Wenxia.; Huang, Songlin.; Yang, Liangliang.; Zhang, Guogang. Comparative Analysis of the Fecal Bacterial Microbiota of Wintering Whooper Swans (Cygnus Cygnus). Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 2021. 8. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Wen.; Wang, Fang.; Li, Laixing.; Wang, Aizhen.; Sharshov, Kirill.; Druzyaka, Alexey.; Lancuo, Zhuoma.; Wang, Shuoying.; Shi, Yuetong. Characterization of the gut microbiome of black-necked cranes (Grus nigricollis) in six wintering areas in China. Archives of Microbiology, 2020. 202(5): p. 983-993. [CrossRef]

- Godoy-Vitorino, Filipa.; Ley, Ruth E.; Gao, Zhan.; Pei, Zhiheng.; Ortiz-Zuazaga, Humberto.; Pericchi, Luis R.; Garcia-Amado, Maria A.; Michelangeli, Fabian.; Blaser, Martin J.; Gordon, Jeffrey I.; et al. Bacterial community in the crop of the hoatzin, a neotropical folivorous flying bird. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2008. 74(19): p. 5905-5912. [CrossRef]

- D'Andreano, Sara.; Bonastre, Armand Sanchez.; Francino, Olga.; Marti, Anna Cusco.; Lecchi, Cristina.; Grilli, Guido.; Giovanardi, Davide.; Ceciliani, Fabrizio. GENETICS AND GENOMICS Gastrointestinal microbial population of turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) affected by hemorrhagic enteritis virus. Poultry Science. 2017. 96(10): p. 3550-3558.

- Jumpertz, Reiner.; Duc Son Le.; Turnbaugh, Peter J.; Trinidad, Cathy.; Bogardus, Clifton.; Gordon, Jeffrey I.; Krakoff, Jonathan. Energy-balance studies reveal associations between gut microbes, caloric load, and nutrient absorption in humans. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2011. 94(1): p. 58-65. [CrossRef]

- Turnbaugh, Peter J.; Baeckhed, Fredrik.; Fulton, Lucinda.; Gordon, Jeffrey I. Diet-induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Cell Host & Microbe. 2008. 3(4): p. 213-223. [CrossRef]

- Liao, X. D.; Ma, G.; Cai, J.; Fu, Y.; Yan, X. Y.; Wei, X. B.; Zhang, R. J. Effects of Clostridium butyricum on growth performance, antioxidation, and immune function of broilers. Poultry Science. 2015. 94(4): p. 662-667.

- Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Yun, T. T.; Qi, W. T.; Liang, X. X.; Wang, Y. W.; Li, A. K. Effects of pre-encapsulated and pro-encapsulated Enterococcus faecalis on growth performance, blood characteristics, and cecal microflora in broiler chickens. Poultry Science. 2015. 94(11): p. 2821-2830. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Hsiao-Pei.; Wang, Yu-bin.; Huang, Shiao-Wei.; Lin, Chung-Yen.; Wu, Martin.; Hsieh, Chih-hao.; Yu, Hon-Tsen. Metagenomic analysis reveals a functional signature for biomass degradation by cecal microbiota in the leaf-eating flying squirrel (Petaurista alborufus lena). Bmc Genomics. 2012. 13. [CrossRef]

- Samanta, Ashis K.; Torok, Valeria A.; Percy, Nigel J. Abimosleh, Suzanne M.; Howarth, Gordon S., Microbial Fingerprinting Detects Unique Bacterial Communities in the Faecal Microbiota of Rats with Experimentally-Induced Colitis. Journal of Microbiology. 2012. 50(2): p. 218-225. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Lifeng.; Wu, Qi.; Dai, Jiayin.; Zhang, Shanning.; Wei, Fuwen. Evidence of cellulose metabolism by the giant panda gut microbiome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011. 108(43): p. 17714-17719.

- Liu, Ya-Jun.; Liu, Shuang-Jiang.; Drake, Harold L.; Horn, Marcus A. Alphaproteobacteria dominate active 2-methyl-4-chlorophenoxyacetic acid herbicide degraders in agricultural soil and drilosphere. Environmental Microbiology. 2011. 13(4): p. 991-1009. [CrossRef]

- Turnbaugh, Peter J.; Hamady, Micah.; Yatsunenko, Tanya.; Cantarel, Brandi L.; Duncan, Alexis.; Ley, Ruth E.; Sogin, Mitchell L.; Jones, William J.; Roe, Bruce A.; Affourtit, Jason P.; et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009. 457(7228): p. 480-U7.

- Dominianni, Christine.; Sinha, Rashmi.; Goedert, James J.; Pei, Zhiheng.; Yang, Liying.; Hayes, Richard B.; Ahn, Jiyoung.; Sex, Body Mass Index, and Dietary Fiber Intake Influence the Human Gut Microbiome. Plos One. 2015. 10(4). [CrossRef]

- Yu, Hongjie.; Jing, Huaiqi.; Chen, Zhihai.; Zheng, Han.; Zhu, Xiaoping.; Wang, Hua.; Wang, Shiwen.; Liu, Lunguang.; Zu, Rongqiang.; Luo, Longze.; et al., Human Streptococcus suis outbreak, Sichuan, China. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006. 12(6): p. 914-920.

- Torres, Carmen.; Alonso, Carla Andrea.; Ruiz-Ripa, Laura.; Leon-Sampedro, Ricardo.; Del Campo, Rosa.; Coque, Teresa M. Antimicrobial Resistance in Enterococcus spp. of animal origin. Microbiology spectrum. 2018. 6(4).

- Arias, Cesar A.; Murray, Barbara E. The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2012. 10(4): p. 266-278. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Katie.; Phillips, Carol. The ecology, epidemiology and virulence of Enterococcus. Microbiology-Sgm. 2009. 155: p. 1749-1757. [CrossRef]

- Lopinska, Andzelina.; Indykiewicz, Piotr.; Skiebe, Evelyn.; Pfeifer, Yvonne.; Trcek, Janja.; Jerzak, Leszek.; Minias, Piotr.; Nowakowski, Jacek.; Ledwon, Mateusz.; Betleja, Jacek.; et al., Low Occurrence of Acinetobacter baumannii in Gulls and Songbirds. Polish Journal of Microbiology. 2020. 69(1): p. 85-90. [CrossRef]

- Francey, T.; Gaschen, F.; Nicolet, J.; Burnens, AP., et al., The role of Acinetobacter baumannii as a nosocomial pathogen for dogs and cats in an intensive care unit. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2000. 14(2): p. 177-183. [CrossRef]

- Guardabassi, L.; Dalsgaard, A.; Olsen, JE. Phenotypic characterization and antibiotic resistance of Acinetobacter spp. isolated from aquatic sources. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 1999. 87(5): p. 659-667. [CrossRef]

- Doughari, Hamuel James.; Ndakidemi, Patrick Alois.; Human, Izanne Susan.; Benade, Spinney. The Ecology, Biology and Pathogenesis of Acinetobacter spp.: An Overview. Microbes and Environments. 2011. 26(2): p. 101-112. [CrossRef]

- Das, Taraprasad.; Jayasudha, Rajagopalaboopathi.; Chakravarthy, SamaKalyana.; Prashanthi, Gumpili Sai.; Bhargava, Archana.; Tyagi, Mudit.; Rani, Padmaja Kumari.; Pappuru, Rajeev Reddy.; Sharma, Savitri.; Shivaji, Sisinthy. Alterations in the gut bacterial microbiome in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus and diabetic retinopathy. Scientific Reports. 2021. 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Xu, Miao.; Han, Shining.; Lu, Ningning.; Zhang, Xin.; Liu, Junmei.; Liu, Dong.; Xiong, Guangming.; Guo, Liquan. Degradation of Oestrogen and an Oestrogen-like Compound in Chicken Faeces by Bacteria. Water Air and Soil Pollution. 2018. 229(10). [CrossRef]

- Opota, Onya.; Ney, Barbara.; Zanetti, Giorgio.; Jaton, Katia.; Greub, Gilbert.; Prod'hom, Guy. Bacteremia Caused by Comamonas kerstersii in a Patient with Diverticulosis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2014. 52(3): p. 1009-1012.

- Wan, Yi.; Ma, Ruiyu.; Chai, Lilong.; Du, Qiang.; Yang, Rongbin.; Qi, Renrong.; Liu, Wei.; Li, Junying.; Li, Yan.; Zhan, Kai. Determination of bacterial abundance and communities in the nipple drinking system of cascading cage layer houses. Scientific Reports. 2021. 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Bin, Peng.; Tang, Zhiyi.; Liu, Shaojuan.; Chen, Shuai.; Xia, Yaoyao.; Liu, Jiaqi.; Wu, Hucong.; Zhu, Guoqiang. Intestinal microbiota mediates Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli-induced diarrhea in piglets. Bmc Veterinary Research. 2018. 14. [CrossRef]

- Morales Fenero, Camila Ideli.; Colombo Flores, Alicia Angelina.; Camara, Niels Olsen Saraiva. Inflammatory diseases modelling in zebrafish. World journal of experimental medicine, 2016. 6(1): p. 9-20.

- Yu Xi.; Niu Shuling.; Tie Kunyuan.; Zhang Qiuyang.; Deng Hewen.; Gao ChenCheng.; Yu Tianhe.; Lei Liancheng.; Feng Xin. Characteristics of the intestinal flora of specific pathogen free chickens with age. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2019. 132: p. 325-334. [CrossRef]

- Rajoka, Muhammad Shahid Riaz.; Wu, Yiguang.; Mehwish, Hafiza Mahreen.; Bansal, Manisha.; Zhao, Liqing. Lactobacillus exopolysaccharides: New perspectives on engineering strategies, physiochemical functions, and immunomodulatory effects on host health. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2020. 103: p. 36-48. [CrossRef]

| Category | Firmicutes | Proteobacteria | Bacteroidetes | Fusobacteria | Actinobacteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WM | 79.02% | 12.85% | 2.79% | 3.37% | — |

| DM | 67.97% | 24.48% | 3.13% | 2.21% | 1.10% |

| Phylum | Genus | DM | WM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firmicutes | Streptococcus | 35.07% | 7.62% |

| Enterococcus | 13.67% | 3.80% | |

| Clostridium | 1.53% | 2.96% | |

| Lactobacillus | — | 2.83% | |

| Solibacillus | — | 1.87% | |

| Bacillus | — | 1.28% | |

| Proteobacteria | Acinetobacter | 5.09% | 1.16% |

| Comamonas | 2.37% | — | |

| Shigella | 2.50% | — | |

| Fusobacteria | Cetobacterium | — | 2.22% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).