Submitted:

08 August 2023

Posted:

09 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Desing

2.2. Item Bank Construction

2.3. Selection of Experts

2.4. Delphi Method

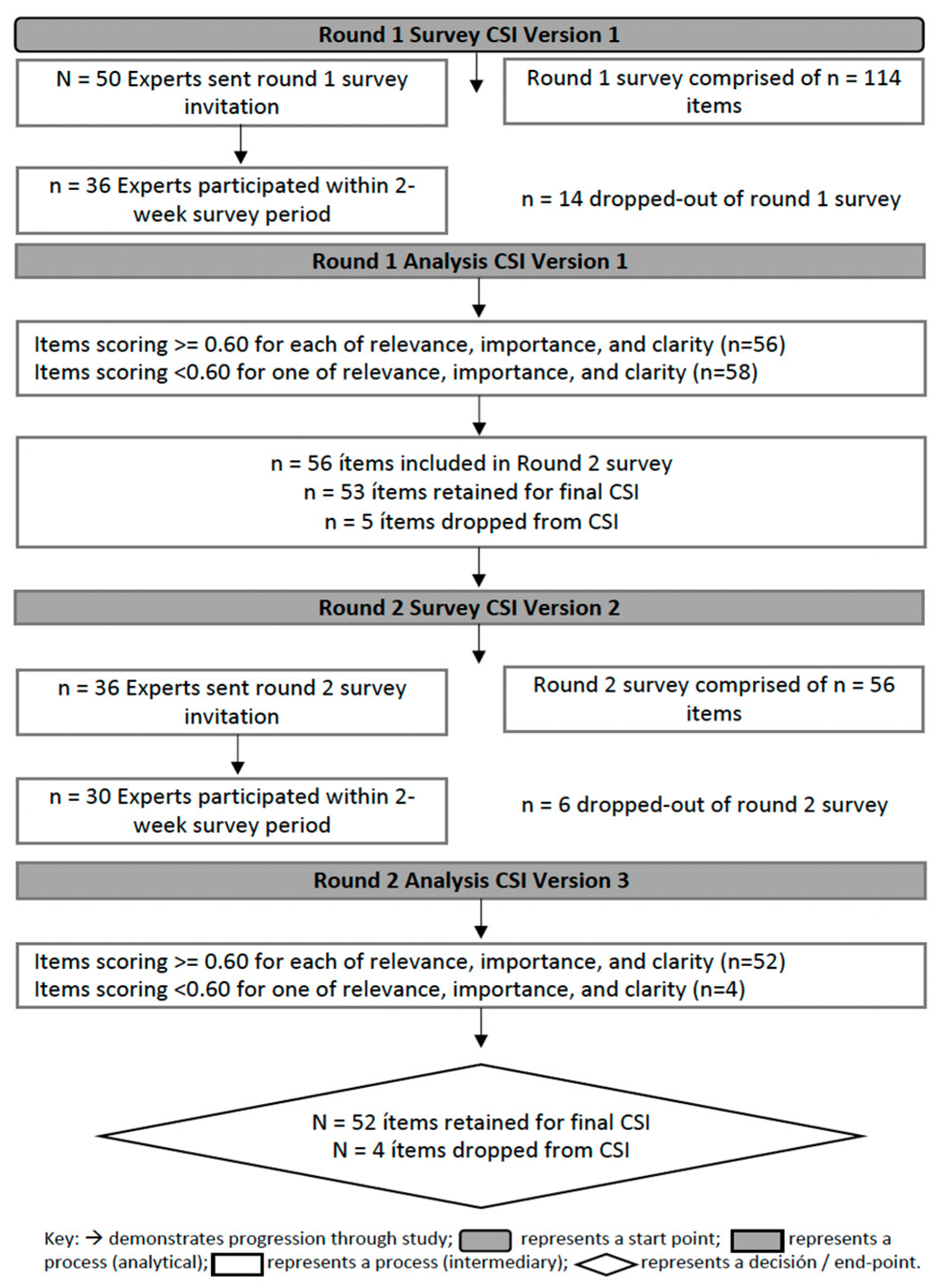

2.4.1. Round 1. Content Validity / Linguistic Validity and Loss of Experts are Evaluated.

2.4.2. Round 2. Content Validity Assessed.

2.5. Content Validity Analysis

2.6. Comprehensibility Analysis / Linguistic Validation

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Experts

3.2. Results of the Delphi Method

3.3. Content Validity Analysis

3.4. Comprehensibility or Linguistic Validation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Items | Relevant to the topic | Understanding for the topic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CVI | Aiken´s V | Average Score | |

| 1. Have you ever felt nervous, anxious or very upset? | 0,946 | 0,903 | 4,39 |

| 2. Have you not been able to stop worrying? | 0,676 | 0,736 | 3,39 |

| 3. Have you worried too much about different things? | 0,622 | 0,681 | 3,56 |

| 4. Have you had difficulty relaxing? | 0,919 | 0,840 | 4,64 |

| 5. Have you ever felt so restless that you could not sit still? | 0,568 | 0,667 | 3,50 |

| 6. Have you been easily annoyed or irritated? | 0,919 | 0,903 | 4,61 |

| 7. Have you been afraid as if something terrible was going to happen? | 0,811 | 0,792 | 4,22 |

| 8. Have you had little interest or pleasure in doing things? | 0,838 | 0,847 | 4,39 |

| 9. Have you ever felt discouraged, depressed or hopeless? | 0,865 | 0,861 | 4,53 |

| 10. Have you had difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or sleeping too much? | 0,865 | 0,903 | 4,47 |

| 11. Have you ever felt tired or low on energy? | 0,865 | 0,840 | 4,47 |

| 12. Have you ever felt lacking in appetite or, on the contrary, have you eaten too much? | 0,703 | 0,757 | 4,19 |

| 13. Have you ever felt bad about yourself or that you are a failure or failing yourself? | 0,865 | 0,826 | 3,44 |

| 14. Have you had difficulty concentrating on doing things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television? | 0,784 | 0,799 | 4,17 |

| 15. Have you ever moved or talked so slowly that other people around you have noticed or, conversely, when you are nervous or restless do you move more than usual? | 0,595 | 0,681 | 3,39 |

| 16. Have you ever had thoughts that you might be better off dead or hurting yourself? | 0,919 | 0,889 | 4,28 |

| 17. Do familiar environments sometimes seem strange, confusing, threatening or unreal to you? | 0,784 | 0,792 | 4,25 |

| 18. Have you ever heard unusual sounds such as popping, popping, hissing, clapping, or ringing in your ears? | 0,676 | 0,729 | 4,06 |

| 19. Do the things you see seem different from the way they normally are (brighter or duller, bigger or smaller, or changed in some other way? | 0,649 | 0,701 | 4,00 |

| 20. Have you had any experiences of telepathy, seer or fortune teller powers? | 0,405 | 0,597 | 3,64 |

| 21. Have you ever felt as if you were not in control of your own thoughts or ideas? | 0,838 | 0,826 | 4,33 |

| 22. Have you had difficulty following your own topic because you ramble or lose track when you speak? | 0,892 | 0,819 | 3,78 |

| 23. Have you ever had a strong feeling or belief that you possess any kind of unusual gifts or talents, for example telepathy? | 0,514 | 0,604 | 3,81 |

| 24. Have you ever had the feeling that other people are watching you or talking about you? | 0,892 | 0,875 | 4,67 |

| 25. Have you ever noticed any sensation on or under the skin, such as bugs? | 0,757 | 0,806 | 4,19 |

| 26. have you ever felt suddenly distracted by distant sounds that you were not normally aware of? | 0,568 | 0,701 | 3,89 |

| 27. Have you ever had the feeling that there was a person or force around you, even though you could not see anyone? | 0,676 | 0,694 | 4,06 |

| 28. Have you ever worried that something might go wrong in your mind? | 0,865 | 0,861 | 4,28 |

| 29. Have you ever felt that you did not exist, that the world did not exist or that you were dead? | 0,568 | 0,653 | 3,83 |

| 30. Have you ever felt confused about whether something that happened to you was real or imaginary? | 0,811 | 0,806 | 4,31 |

| 31. Have you ever held beliefs that other people would find difficult to believe? | 0,649 | 0,708 | 3,75 |

| 32. Have you felt that parts of your body have changed in any way, or that parts of your body were functioning in a different way? | 0,622 | 0,715 | 3,92 |

| 33. Have you felt that your thoughts are sometimes so intense that you can almost hear them? | 0,676 | 0,722 | 4,14 |

| 34. Have you ever had feelings of distrust towards other people? | 0,811 | 0,840 | 4,47 |

| 35. Have you ever seen unusual things such as flashes, flames, glaring lights, or geometric shapes? | 0,757 | 0,736 | 4,17 |

| 36. Have you ever seen things that other people cannot see? | 0,757 | 0,764 | 4,08 |

| 37. Do people sometimes have a hard time understanding what you were saying? | 0,757 | 0,771 | 4,08 |

| 38. Have you planned your tasks carefully? | 0,459 | 0,590 | 3,69 |

| 39. Have you ever done things without thinking about them? | 0,595 | 0,694 | 4,17 |

| 40. Have you hardly ever taken things to heart or are you not easily disturbed? | 0,378 | 0,549 | 2,50 |

| 41. Have you ever had thoughts that your mind is going faster than normal? | 0,811 | 0,819 | 4,14 |

| 42. Do you consider yourself a person who plans your trips in advance? | 0,270 | 0,438 | 4,08 |

| 43. Do you consider yourself a person with self-control? | 0,811 | 0,785 | 4,25 |

| 44. Are you a person who is able to concentrate easily? | 0,730 | 0,715 | 4,39 |

| 45. Are you a person who saves regularly? | 0,514 | 0,604 | 4,42 |

| 46. Do you find it difficult to sit still for long periods of time? | 0,784 | 0,764 | 4,39 |

| 47. Do you think things through carefully? | 0,568 | 0,653 | 4,08 |

| 48. Do you plan to have a steady job or do you strive to ensure that you will have money to pay your expenses? | 0,514 | 0,625 | 3,86 |

| 49. Do you ever say things without thinking them through? | 0,595 | 0,681 | 4,19 |

| 50. Do you like to think about complicated problems? | 0,459 | 0,576 | 3,94 |

| 51. Do you change jobs frequently? | 0,514 | 0,660 | 4,28 |

| 52. Do you act impulsively? | 0,865 | 0,840 | 4,28 |

| 53. Do you get bored easily trying to solve problems in your mind? | 0,514 | 0,653 | 3,94 |

| 54. Do you visit the doctor and dentist frequently? | 0,514 | 0,632 | 4,00 |

| 55. Do you do things as they occur to you? | 0,595 | 0,681 | 4,06 |

| 56. Do you consider yourself a person who thinks without being distracted, that is, can you focus your mind on one thing for a long time? | 0,622 | 0,694 | 4,08 |

| 57. Do you change housing frequently, i.e., do you move frequently or do you dislike living in the same place for a long time? | 0,378 | 0,542 | 4,00 |

| 58. Do you buy things on impulse? | 0,595 | 0,694 | 4,25 |

| 59. Do you complete all the activities you start? | 0,622 | 0,688 | 4,33 |

| 60. Do you walk and move quickly? | 0,324 | 0,576 | 4,11 |

| 61. Do you solve problems by experimenting, i.e., do you solve problems by trying a possible solution and seeing if it works? | 0,541 | 0,667 | 3,83 |

| 62. Do you spend more in cash or credit than you earn? | 0,622 | 0,715 | 3,92 |

| 63. Have you noticed that you talk faster than usual? | 0,649 | 0,708 | 3,81 |

| 64. Have you ever had strange thoughts when you were thinking? | 0,676 | 0,736 | 3,61 |

| 65. Are you more interested in the present than in the future? | 0,622 | 0,688 | 4,33 |

| 66. Do you feel restless in classes or lectures if you have to listen to someone talk for a long period of time? | 0,595 | 0,667 | 4,17 |

| 67. Do you plan for the future, i.e., are you more interested in the future than in the present? | 0,595 | 0,632 | 4,00 |

| 68. Have you ever had stomach pain? | 0,459 | 0,576 | 4,50 |

| 69. Have you ever had back pain? | 0,351 | 0,528 | 4,44 |

| 70. Have you ever had pain in your arms, legs or joints (knees, hips)? | 0,432 | 0,563 | 4,28 |

| 71. Have you had menstrual cramps or other problems with your periods? | 0,297 | 0,458 | 3,97 |

| 72. Have you ever had headaches? | 0,541 | 0,646 | 4,58 |

| 73. Have you ever had chest pains? | 0,676 | 0,688 | 4,47 |

| 74. Have you ever had dizziness? | 0,703 | 0,701 | 4,39 |

| 75. Have you had any episodes of fainting? | 0,649 | 0,694 | 4,39 |

| 76. Have you ever felt that your heart was beating faster and faster? | 0,811 | 0,806 | 4,44 |

| 77. Have you ever felt short of breath? | 0,865 | 0,799 | 4,44 |

| 78. At any time have you experienced pain or problems during sexual penetration? | 0,649 | 0,708 | 4,28 |

| 79. Have you had episodes of constipation or diarrhea? | 0,514 | 0,632 | 4,47 |

| 80. Have you ever had nausea? | 0,622 | 0,681 | 4,50 |

| 81. Have you ever felt tired or low on energy? | 0,865 | 0,847 | 4,58 |

| 82. Have you had difficulty sleeping? | 0,946 | 0,903 | 4,75 |

| 83. Have you ever felt that life was not worth living? | 0,919 | 0,875 | 4,67 |

| 84. Have you ever wished you were dead or could sleep and wake up? | 0,784 | 0,771 | 3,08 |

| 85. Have you ever really had the idea of committing suicide? | 0,865 | 0,861 | 4,22 |

| 86. Have you thought about how you would do it? | 0,811 | 0,806 | 4,36 |

| 87. Have you ever tried to take your own life? | 0,811 | 0,847 | 4,61 |

| 88. Have you ever felt that you have difficulty maintaining your attention, are easily distracted, unable to concentrate? | 0,838 | 0,833 | 4,42 |

| 89. Have you ever felt that you are Impulsive, impatient, poorly tolerate pain or frustration? | 0,757 | 0,785 | 3,78 |

| 90. Do you ever feel uncooperative, uncaring, and demanding of yourself? | 0,541 | 0,694 | 3,69 |

| 91. Do you consider that you are violent or threatening to people? | 0,649 | 0,750 | 4,28 |

| 92. Do you consider yourself an explosive person or a person with anger attacks that are difficult to predict? | 0,757 | 0,785 | 4,39 |

| 93. Do you consider yourself a restless person, rubbing, moaning or other self-stimulating behavior? | 0,432 | 0,611 | 2,86 |

| 94. Do you consider yourself a restless person, come and go, and move around excessively? | 0,649 | 0,729 | 3,72 |

| 95. Do you consider yourself a person who exhibits repetitive, motor or verbal behaviors? | 0,541 | 0,688 | 3,44 |

| 96. Do you consider yourself a fast or excessive talker? | 0,595 | 0,722 | 4,17 |

| 97. Do you consider yourself a person who changes mood frequently? | 0,892 | 0,840 | 4,50 |

| 98. Do you consider yourself a person who cries or laughs easily and excessively? | 0,757 | 0,750 | 4,08 |

| 99. Do you consider yourself a person who insults or hurts others? | 0,541 | 0,667 | 3,69 |

| 100. Have you ever felt as if people were dropping hints or making double entendres? | 0,757 | 0,757 | 4,00 |

| 101. Have you ever felt as if some people are not what they appear to be? | 0,649 | 0,708 | 3,83 |

| 102. Have you ever felt that you are being persecuted in any way? | 0,730 | 0,771 | 4,25 |

| 103. Have you ever felt as if there was a conspiracy against you? | 0,703 | 0,764 | 4,19 |

| 104. Have you ever felt that people look at you strangely because of your appearance? | 0,811 | 0,771 | 4,33 |

| 105. Have you felt that certain electronic devices, such as computers, phones or tablets, can influence your thinking? | 0,676 | 0,715 | 4,19 |

| 106. Have you felt as if your thoughts were being pulled out of your head? | 0,676 | 0,708 | 3,94 |

| 107. Have you ever felt as if your thoughts were not your own? | 0,811 | 0,771 | 4,36 |

| 108. Have you ever had thoughts that were so intense that you were worried that others might hear them? | 0,595 | 0,688 | 4,22 |

| 109. Have you ever felt as if your thoughts were constantly repeating in your mind? | 0,811 | 0,778 | 4,39 |

| 110. Have you ever felt as if you were under the control of any external force or power? | 0,649 | 0,694 | 4,11 |

| 111. Have you ever felt as if a look-alike had impersonated a family member, friend or acquaintance? | 0,459 | 0,597 | 3,94 |

| 112. Have you ever heard voices when you were alone? | 0,784 | 0,778 | 4,42 |

| 113. Have you ever heard voices talking to each other when you were alone? | 0,703 | 0,722 | 3,89 |

| 114. Have you ever seen objects, people or animals that other people could not see? | 0,622 | 0,688 | 4,17 |

References

- Curto, J.; Dolengevich, H.; Soriano, R.; Belza, M.J. Documento técnico: abordaje de la salud mental del usuario con prácticas de Chemsex. MSD 2020. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/ciudadanos/enfLesiones/enfTransmisibles/sida/chemSex/docs/Abordaje_salud_mental_chemsex.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Wang, H.; d'Abreu de Paulo, K.J.; Gültzow, T.; Zimmermann, H.M.; Jonas, K.J. Perceived Monkeypox Concern and Risk among Men Who Have Sex with Men: Evidence and Perspectives from The Netherlands. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolmont, M.; Tshikung, O.N.; Trellu, L.T. Chemsex, a Contemporary Challenge for Public Health. J Sex Med. 2022, 19, 1210–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maviglia, F.; Wickersham, J.A.; Azwa, I.; Copenhaver, N.; Kennedy, O.; Kern, M.; Khati, A.; Lim, S.H.; Gautam, K.; Shrestha, R. Engagement in Chemsex among Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) in Malaysia: Prevalence and Associated Factors from an Online National Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 24, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerras, J.M.; Hoyos, J.; Donat, M.; de la Fuente, L.; Palma Díaz, D.; Ayerdi, O.; García-Pérez, J.N.; García de Olalla, P.; Belza, M.J. Sexualized drug use among men who have sex with men in Madrid and Barcelona: The gateway to new drug use? Front Public Health. 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.S.; Tang, P.M.; Yan, E. Chemsex and its risk factors associated with human immunodeficiency virus among men who have sex with men in Hong Kong. World J Virol. 2022, 25, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madrid Salud. Plan de Adicciones de la Ciudad de Madrid. 2021/2022. 2022. Available online: https://madridsalud.es/pdf/PLAN%20DE%20ADICCIONES%2022-26.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Marqués-Sánchez, P.; Bermejo-Martínez, D.; Quiroga Sánchez, E.; Calvo-Ayuso, N.; Liébana-Presa, C.; Benítez-Andrades, J.A. Men who have sex with men: An approach to social network analysis. Public Health Nurs. 2023, 40, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundsen, E.; Haugstvedt, Å.; Skogen, V.; Berg, R.C. Health characteristics associated with chemsex among men who have sex with men: Results from a cross-sectional clinic survey in Norway. PLoS One. 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Íncera-Fernández, D.; Román, F.J.; Moreno-Guillén, S.; Gámez-Guadix, M. Understanding Sexualized Drug Use: Substances, Reasons, Consequences, and Self-Perceptions among Men Who Have Sex with Other Men in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Baeza, A.; Barrio-Fernández, P.; Curto-Ramos, J.; Ibarguchi, L.; Dolengevich-Segal, H.; Cano-Smith, J.; Rúa-Cebrián, G.; García-Carrillo de Albornoz, A.; Kessel, D. Understanding Attachment, Emotional Regulation, and Childhood Adversity and Their Link to Chemsex. Subst Use Misuse. 2023, 58, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, M.; Halms, T.; Rüther, T.; Hasan, A.; Gertzen, M. Lethal Lust: Suicidal Behavior and Chemsex—A Narrative Review of the Literature. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M. H.; Chen, G.J.; Sun, H.Y.; Chen, Y.T.; Su, L.H.; Ho, S.Y.; Chang, S.Y.; Huang, S.H.; Huang, Y.C.; Liu, W. D.; et al. Risky sexual practices and hepatitis C viremia among HIV-positive men who have sex with men in Taiwan. J microbiol Immunol Infectn. 2023, 56, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiq, M.; O'Flanagan, H.; Richardson, D.; Llewellyn, C.D. Factors associated with sexually transmitted shigella in men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Sex Transm Infect. 2023, 99, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devos, S.; Bonnet, F.; Hessamfar, M.; Neau, D.; Vareil, M.O.; Leleux, O.; Cazanave, C.; Rouanes, N.; Duffau, P.; Lazaro, E.; et al. Tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and illicit drug use and their association with CD4/CD8 cell count ratio in people with controlled HIV: a cross-sectional study (ANRS CO3 AQUIVIH-NA-QuAliV). BMC Infect Dis. 2023, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Gámez, L.; Hernández-Huerta, D.; Lahera, G. Chemsex and Psychosis: A Systematic Review. Behav Sci (Basel). 2022, 15, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugarte, A.; de la Mora, L.; García, D.; Martínez-Rebollar, M.; de-Lazzari, E.; Torres, B.; Inciarte, A.; Ambrosioni, J.; Chivite, I.; Solbes, E.; et al. Evolution of Risk Behaviors, Sexually Transmitted Infections and PrEP Care Continuum in a Hospital-Based PrEP Program in Barcelona, Spain: A Descriptive Study of the First 2 Years’ Experience. Infect Dis Ther 2023, 12, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.P.; Choi, K.W.; Wu, C.; Chau, P.H.; Kwok, J.Y.; Wong, W.C.; Chow, E.P. Web-Based Harm Reduction Intervention for Chemsex in Men Who Have Sex With Men: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2023, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platteau, T.; Herrijgers, C.; Kenyon, C.; Florence, E. Self-control for harm reduction in chemsex. Lancet HIV. 2023, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrijgers, C.; Platteau, T.; Vandebosch, H.; Poels, K.; Florence, E. Using Intervention Mapping to Develop an mHealth Intervention to Support Men Who Have Sex With Men Engaging in Chemsex (Budd): Development and Usability Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2022, 21, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmania, S. HERO-providing support for those engaged in chemsex. Lancet HIV. 2022, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galicia, P.; Chuvieco, S.; Santos Larrégola, L.; Cuadros, J.; Ramos-Rincón, J.M.; Linares, M. Awareness of chemsex, pre-exposure prophylaxis, and sexual behavior in primary health care in Spain. Semergen. 2023, 49, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Nagington, M.; King, S. Support, care and peer support for gay and bi men engaging in chemsex. Health Soc Care Community. 2022, 30, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoops, L.; van Amsterdam, J.; Albers, T.; Brunt, T.M.; van den Brink, W. Slamsex in The Netherlands among men who have sex with men (MSM): use patterns, motives, and adverse effects. Sex Health. 2022, 19, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahão, A.B.; Kortas, G.T.; Blaas, I.K.; Koch, G.; Leopoldo, K.; Malbergier, A.; Torales, J.; Ventriglio, A.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M. The impact of discrimination on substance use disorders among sexual minorities. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2022, 34, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Gooding, D.C.; Ortuño-Sierra, J.; Paino, M. Assessing self-reported clinical high risk symptoms in community-derived adolescents: A psychometric evaluation of the Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief. Compr Psychiatry. 2016, 66, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrote-Cámara, M.E.; Santolalla-Arnedo, I.; Ruiz de Viñaspre-Hernández, R.; Gea-Caballero, V.; Sufrate-Sorzano, T.; del Pozo-Herce, P.; Garrido-García, R.; Rubinat-Arnaldo, E.; Juárez Vela, R. Psychometric Characteristics and Sociodemographic Adaptation of the Corrigan Agitated Behavior Scale in Patients With Severe Mental Disorders. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, C.; Kavanagh, D.J.; Hides, L.; Scott, J.G. Current CAPE-15: a measure of recent psychotic-like experiences and associated distress. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2017, 11, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvo, L.; Castro, A. Confiabilidad y validez de la escala de impulsividad de Barratt (BIS-11) en adolescentes. Rev. chil. neuro-psiquiatr. 2013, 51, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros Montalbán, S.; Comas Vives, A.; Garcia-Garcia, M. Validation of the Spanish version of the PHQ-15 questionnaire for the evaluation of physical symptoms in patients with depression and/or anxiety disorders: DEPRE-SOMA study. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2010, 38, 345–57. [Google Scholar]

- Paykel, E.S.; Myers, J.K.; Lindenthal, J.J.; Tanner, J. Suicidal feelings in the general population: a prevalence study. Br J Psychiatry. 1974, 124, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, F.; Keeney, S.; McKenna, H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000, 32, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, V.; Linstone, H.A.; Turoff, M. The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. Journal of Marketing Research. 1976, 13, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The content validity index: are you sure you know what's being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2006, 29, 489–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orts-Cortés, M.I.; Moreno-Casbas, T.; Squires, A.; Fuentelsaz-Gallego, C.; Maciá-Soler, L.; González-María, E. Content validity of the Spanish version of the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index. Appl Nurs Res. 2013, 26, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, A.; Aiken, L.H.; van den Heede, K.; Sermeus, W.; Bruyneel, L.; Lindqvist, R.; Schoonhoven, L.; Stromseng, I.; Busse, R.; Brzostek, T.; et al. A systematic survey instrument translation process for multi-country, comparative health workforce studies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013, 50, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chover-Sierra, E.; Martínez-Sabater, A.; Lapeña-Moñux, Y.R. An instrument to measure nurses' knowledge in palliative care: Validation of the Spanish version of Palliative Care Quiz for Nurses. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0177000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, D.; Penfield & Peter, R.; Giacobbi, J.R. Applying a Score Confidence Interval to Aiken's Item Content-Relevance Index. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci. 2004, 8, 213–225. [CrossRef]

- Bull, C.; Crilly, J.; Latimer, S.; Gillespie, B.M. Establishing the content validity of a new emergency department patient-reported experience measure (ED PREM): a Delphi study. BMC Emerg Med. 2022, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, H.P. The Delphi technique: a worthwhile research approach for nursing? J Adv Nurs. 1994, 19, 1221–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela-Ruiz, M.; Díaz-Bravo, L.; García-Durán, R. Descripción y usos del método Delphi en investigaciones del área de la salud. Investigación educ. médica. 2012, 1, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, B.; Pascual-Ezama, D. La metodología Delphi como técnica de estudio de la validez de contenido. Annals of Psychology. 2012, 28, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, C.; Pawlowski, S.D. The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Information & Management. 2004, 42, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, N.; Brown, W.J.; Faulkner, G.; McKenna, J.; Murphy, M.; Pringle, A.; Proper, K.; Puig-Ribera, A.; Stathi, A. The International Universities Walking Project: development of a framework for workplace intervention using the Delphi technique. J Phys Act Health. 2009, 6, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeta, Jon. El método delphi: una técnica de previsión del futuro. Barcelona: Ariel, 2002. Print.

- Nyumba, Tobias.; Wilson, Kerrie.; Derrick, Christina.; Mukherjee, Nibedita. The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. 2018, 9, 20–32. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Rajinder, Mahal. Modified Delphi Technique: Content validity of the Pressure ulcer risk assessment tool. JoNSP. 2017, 7, 17.19.

- Keeney, S.; Hasson, F.; McKenna, H. Consulting the oracle: ten lessons from using the Delphi technique in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2006, 53, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skulmoski, G.; Hartman, F.; Krahn, J. The Delphi method for graduate research. J. Inf. Technol. 2007, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 21 | (70) |

| Female | 9 | (30) |

| Position | ||

| LGTBI+ Collective | 4 | (13.33) |

| Psychiatry Service | 8 | (26.66) |

| Primary Care | 6 | (20) |

| Urgent Care / Emergency Service | 5 | (16.66) |

| Infectious Diseases Service / STIs Clinic 1 | 7 | (23.33) |

| Autonomous Community | ||

| Aragon | 1 | (3.33) |

| Extremadura | 2 | (6.66) |

| Canary Islands | 2 | (6.66) |

| Catalonia | 5 | (16.66) |

| Valencian Community | 1 | (3.33) |

| La Rioja | 3 | (10) |

| Madrid | 16 | (53.33) |

| Profession | ||

| Psysician | 10 | (33.33) |

| Nurse | 17 | (56.66) |

| Psychologist | 2 | (6.66) |

| Occupational Therapist / Sexologist | 1 | (3.33) |

| Item number first round | Items | CVI | Aiken´s V |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1. Have you felt nervous, anxious or very upset? | 0,900 | 0,900 |

| 4 | 2. Have you ever had difficulty relaxing? | 0,900 | 0,850 |

| 6 | 3. Have you been easily annoyed or irritated? | 0,933 | 0,875 |

| 7 | 4. Have you been afraid as if something terrible was going to happen? | 0,733 | 0,767 |

| 8 | 5. Have you had little interest or pleasure in doing things? | 0,833 | 0,817 |

| 9 | 6. Have you ever felt discouraged, depressed or hopeless? | 0,867 | 0,867 |

| 11 | 7. Have you ever felt tired or low energy? | 0,733 | 0,783 |

| 12 | 8. Have you had no appetite or, on the contrary, have you eaten too much? | 0,667 | 0,725 |

| 13 | 9. Have you ever felt bad about yourself, felt that you are a failure or that you are failing yourself? | 0,800 | 0,817 |

| 14 | 10. Have you had difficulty concentrating on doing everyday things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television? | 0,867 | 0,800 |

| 16 | 11. Have you ever had thoughts that you would be better off dead or harming yourself? | 0,800 | 0,783 |

| 17 | 12. Do familiar environments sometimes seem strange, confusing, threatening or unreal to you? | 0,767 | 0,733 |

| 21 | 13. Have you ever felt as if you were not in control of your own thoughts or ideas? | 0,833 | 0,750 |

| 22 | 14. Have you ever had difficulty following your own conversation because you ramble or lose concentration too much when you talk? | 0,800 | 0,742 |

| 24 | 15. Have you ever had the feeling that other people are watching you or talking about you? | 0,800 | 0,767 |

| 25 | 16. Have you occasionally noticed any sensation on or under the skin, such as bugs? | 0,600 | 0,658 |

| 28 | 17.Have you ever worried that something might go wrong in your mind? | 0,667 | 0,717 |

| 30 | 18. Have you ever felt confused about whether something that happened to you was real or imaginary? | 0,733 | 0,725 |

| 34 | 19. Have you ever had feelings of distrust towards other people? | 0,800 | 0,758 |

| 35 | 20. Have you ever seen unusual things such as flashes, flames, glaring lights or geometric shapes? | 0,733 | 0,692 |

| 36 | 21. Have you ever seen things that other people cannot see? | 0,567 | 0,608 |

| 37 | 22. Do you have the feeling that people find it difficult to understand what you are saying? | 0,633 | 0,650 |

| 41 | 23. Have you ever had thoughts about your mind going faster than normal? | 0,700 | 0,733 |

| 52 | 26. In the last few days have you felt that you were acting impulsively? | 0,867 | 0,783 |

| 66 | 30. Do you feel restless in classes or lectures if you have to listen to someone talk for a long period of time? | 0,633 | 0,700 |

| 73 | 32. Have you ever had chest pains? | 0,700 | 0,708 |

| 76 | 34. Have you ever felt that your heart was beating faster than usual? | 0,800 | 0,800 |

| 77 | 35. Have you ever felt short of breath? | 0,767 | 0,775 |

| 82 | 36. Have you had difficulty sleeping? | 0,900 | 0,883 |

| 85 | 37. Have you ever really had the idea of committing suicide? | 0,833 | 0,792 |

| 86 | 38. Have you thought about how you would carry it out?. | 0,800 | 0,775 |

| 87 | 39. Have you ever tried to take your own life? | 0,700 | 0,700 |

| 88 | 40. Have you ever felt that you have difficulty maintaining your attention, that you are easily distracted, or that you are unable to concentrate? | 0,667 | 0,683 |

| 92 | 42. Do you consider yourself a person with anger attacks that are difficult to predict? | 0,867 | 0,783 |

| 97 | 43. At any time have you considered yourself to be a person who changes moods frequently? | 0,833 | 0,767 |

| 100 | 45. Have you ever felt as if people were dropping hints or saying things with a double meaning? | 0,667 | 0,675 |

| 104 | 46. Have you ever felt that people look at you strangely because of your appearance? | 0,633 | 0,650 |

| 106 | 47. Have you ever felt as if your thoughts were being pulled out of your head? | 0,600 | 0,617 |

| 107 | 48. Have you ever felt as if your thoughts were not your own? | 0,733 | 0,708 |

| 109 | 49. Have you ever felt as if your thoughts were constantly repeating in your mind? | 0,700 | 0,717 |

| 110 | 50. Have you ever felt as if you were under the control of any external force or power? | 0,600 | 0,592 |

| 112 | 51. Have you ever heard voices when you were alone? | 0,733 | 0,717 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).