Submitted:

03 August 2023

Posted:

04 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

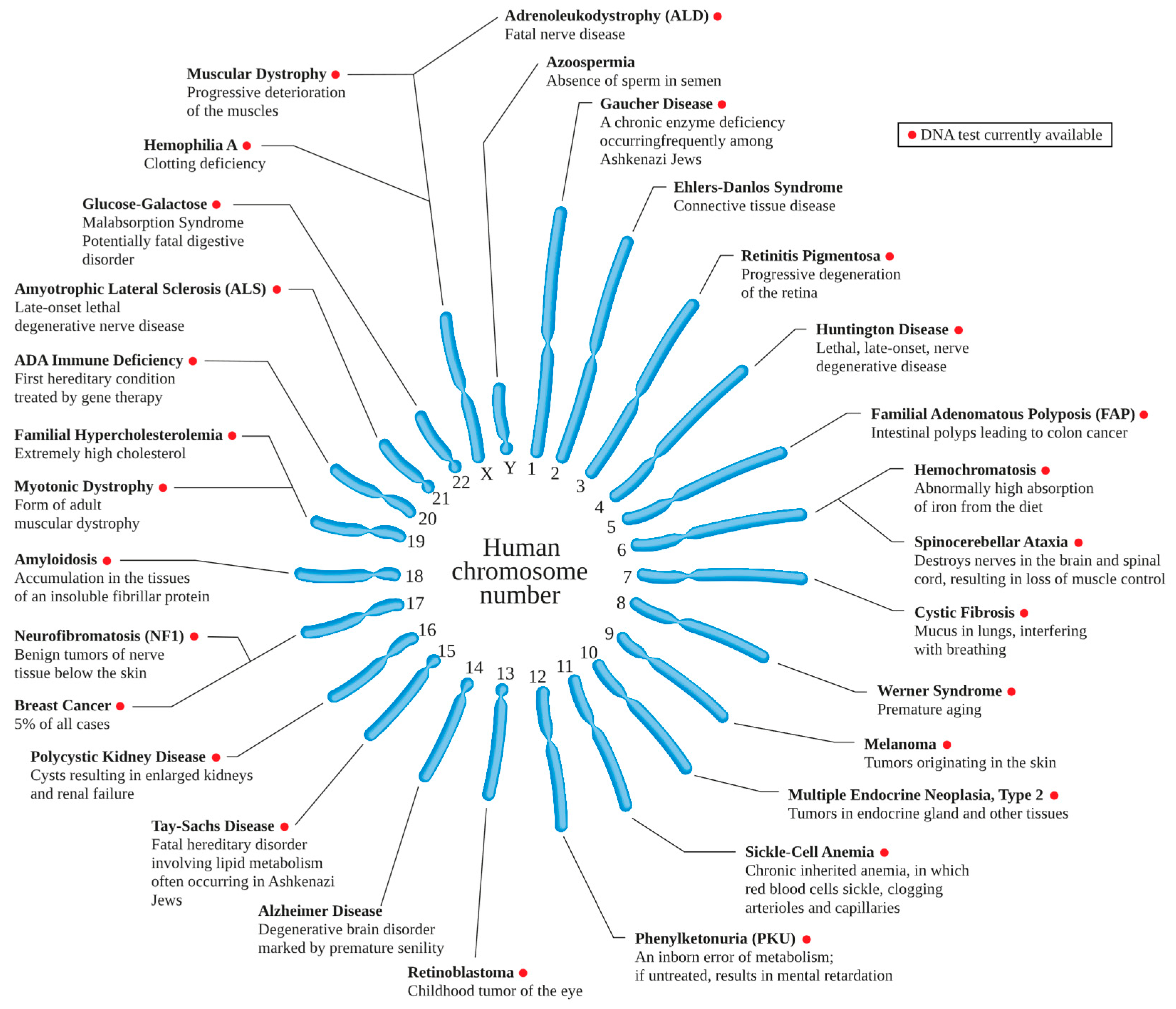

The Science of Gene Editing

Challenges and Concerns

Current Status

Current Status

Regulatory

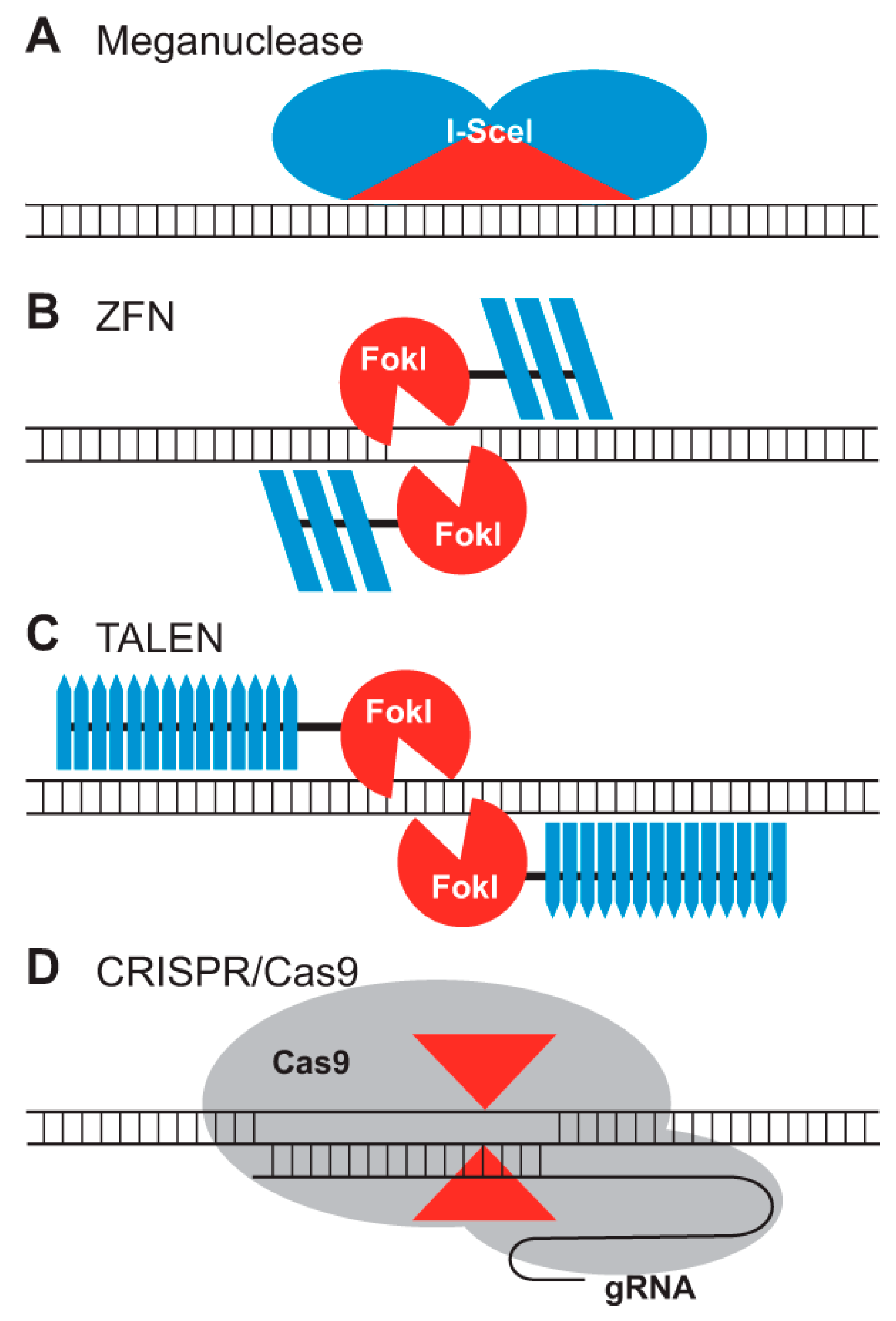

The GE Tools

Nuclease Mediated

| Attribute | Meganucleases | Zinc Finger Nucleases | TALENs | CRISPR/Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | Endonuclease | Fok1-nuclease | Fok1-nuclease | Cas9 nuclease |

| Target site | LAGLIDADG proteins | Zinc-finger binding sites | RVD tandem repeat region of TALE protein | PAM/spacer sequence |

| Recognition sequence size | 12–45 bp | 9–18 bp | 14–20 bp | 3–8 bp/20 bp |

| Targeting limitations | MN cleaving site | Difficult to target non-G-rich sites | 5ʹ targeted base must be a T for each TALEN monomer | The targeted site must precede a PAM sequence |

| Advantage | High specificity; Relatively easy to deliver in vivo | Small protein size; Relatively easy in vivo delivery | High specificity; Relatively easy to engineer; target; mitochondrial DNA more efficiently and cause fewer off-target effects than MNs and ZFNs. | Easy to engineer; Easy to multiplex |

| Disadvantage | Target locus must be put into the genome; complex to construct; difficult to multiplex; ineffectiveness and potential genotoxicity. The targeted locus must also contain the unique cleavage site for each endonuclease. | Expensive, time-consuming, labor-intensive, difficult to choose the target sequence, needing the coding gene to be custom-built for each target site, and highly off-target gene editing. All ZF domains must also be active. | Challenging to multiplex; not relevant in the case of DNA methylcytosine; a few in vivo deliveries; We should all be engaged; TALEs are nevertheless constrained by their repetitive sequences, which make it difficult to construct them using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and by the fact that they are unable to target methylated DNA due to the possibility that cytosine methylation will impede TALE binding and alter recognition by its typical RVD. | Lower specificity; Limited in vivo delivery |

| DNA-recognition mechanism | HR-introduced Protein-DNA interactions | DSB-introduced by Protein-DNA interactions | DSB-introduced by Protein-DNA interactions | DSB introduced by RNA-guided protein-DNA interactions |

| Target specificity | HighPositional mismatches are only occasionally accepted. Protein engineering is necessary for re-targeting. |

Highpreference for G-rich sequences Positional mismatches are only occasionally accepted. Protein engineering is necessary for re-targeting. |

HighRequires a T at each of its target’s five ends. Some positional inconsistencies are accepted. Retargeting necessitates intricate molecular cloning. |

ModerateThe two base pairs that PAM recognizes must come before the RNA-targeted sequence. Positional mismatches are only occasionally accepted. A new RNA guide is necessary for re-targeting. There is no need for protein engineering. |

| Multiplexing | + | + | + | ++++ |

| Delivery | accessible by transduction of viral vectors and electroporation |

accessible by viral vector transduction and electroporation | simple in vitro conception Due to TALEN DNA’s size and the recombination likelihood, it is challenging in vivo. |

simple in vitro The big Cas9’s inadequate packing by viral vectors is the cause of the mild difficulties of distribution in vivo. |

| Use as a gene activator | No | Yes endogenous gene activation minimal impacts off-target To target specific sequences, engineering work may be necessary |

Yes endogenous gene activation minimal impacts off-target There are no time restrictions. |

Yes endogenous gene activation minimal impacts off-target “NGG” PAM is necessary adjacent to the target sequence. |

| Use as gene inhibitor | No | Yes Works by repressing chromatin to prevent transcriptional elongation. minimal impacts off-target To target specific sequences, engineering work may be necessary. |

Yes Works by repressing chromatin to prevent transcriptional elongation. minimal impacts off-target There are no time restrictions. |

Yes Works by repressing chromatin to prevent transcriptional elongation. minimal impacts off-target “NGG” PAM is necessary adjacent to the target sequence. |

| Cost | High | High | High | Reasonable |

| Popularity | Low | Low | Moderate | High |

| Online resources | Database and Engineering for LAGLIDADG Homing Endonucleases (http://homingendonuclease.net/) | The Zinc Finger consortiums include software tools and protocols (http://www.zincfingers.org/) ZFNGenome – resources for locating ZFN target sites (https://bindr.gdcb.iastate.edu/ZFNGenome/) | Mojo Hand (http://www.talendesign.org/) or E-TALEN (http://www.e-talen.org/E-TALEN/) for TALEN designCHOPCHOP (https://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/) target site selection | Guide design: Zlab (https://zlab.bio/guide-design-resources CRISPOR: http://crispor.tefor.net/; Benchling: https://www.benchling.comAddGene: https://www.addgene.org/crispr;; https://crispr.bme.gatech.edu http://www.rgenome.net/cas-offinder/ |

Prime Editing

Base Editing (BE)

Nickase-based genome engineering technologies

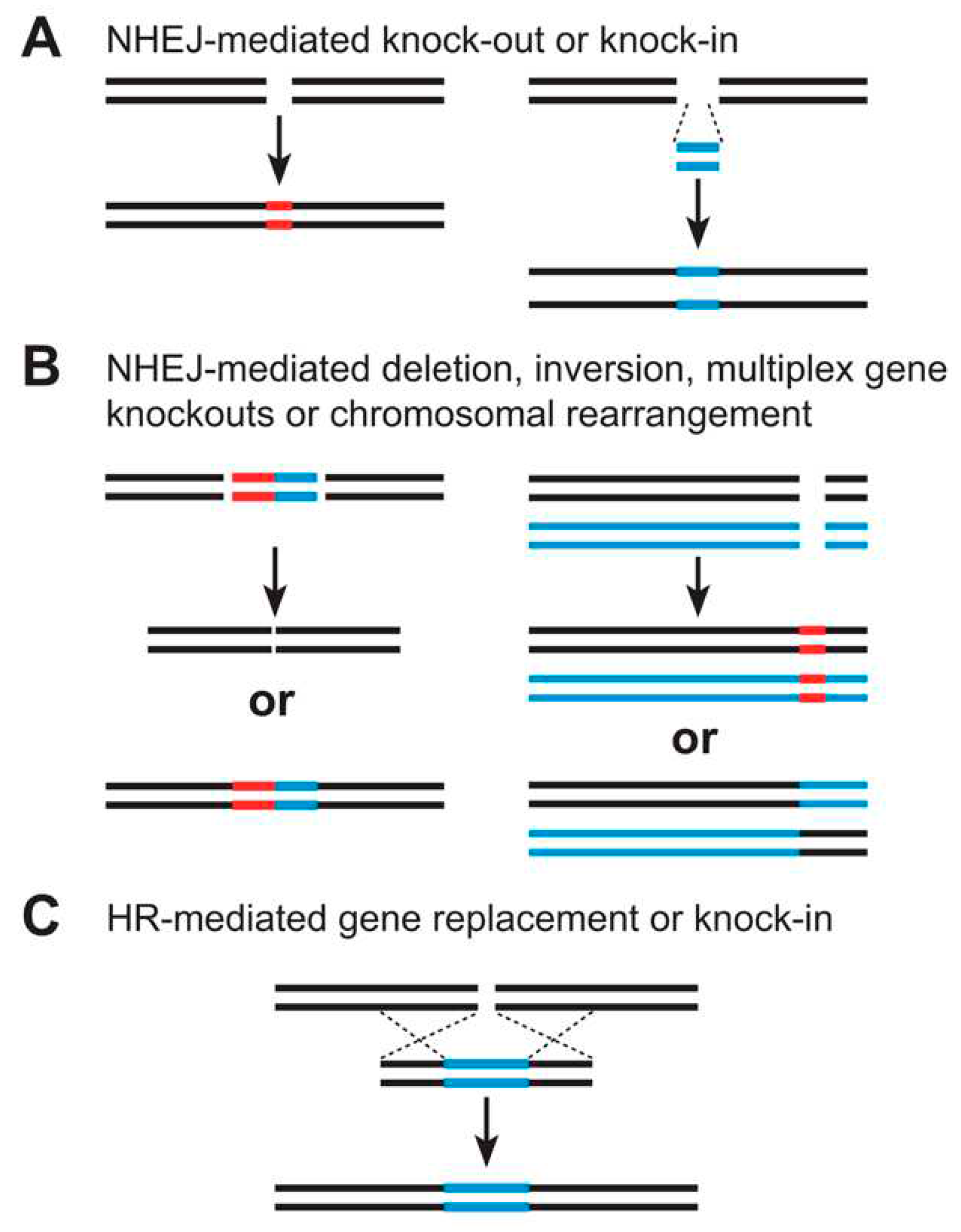

Homologous Recombination

AAV

ssODNS

Synthetic Genomics

TFD-ODN Techniques

Argonautes

Integrase

Recombinase

Delivery Tools

Vectors

Direct

LNPs

- Ex vivo GE can be done using delivery methods like Lipofectamine 2000 or unstable PEI in physiological settings. Other in vivo delivery systems, aside from exosomes, which are physiological environments naturally stable, are typically modified with a surface layer of PEG to prevent the adsorption of serum proteins.

- The tailored delivery systems are perfect for effectively enclosing and safeguarding CRISPR-Cas plasmid, RNA, RNP, or other combined forms based on their characteristics. After packaging, plasmid, RNA, and RNP must retain their biological activity and integrity. The delivery systems’ ability to protect CRISPR-Cas from immune cells, nucleases, and proteases are encouraging. For instance, earlier research has shown promise in encasing CRISPR-Cas inside delivery systems and altering a PEG layer on the exterior of delivery systems.

- For each type of CRISPR-Cas to perform as intended inside target intracellular sites, their delivery systems must be capable of moving and releasing them there. For instance, ribonucleoprotein (RNP) -based CRISPR-Cas delivery systems should enable endosomal escape and localize into nuclei for genome editing. The Cas mRNA should be released for translation into the cytoplasm by the RNA-based CRISPR-Cas delivery systems. Endosomes shouldn’t be able to stop plasmid-based CRISPR-Cas delivery systems from translocating into the nucleus for transcription. Cationic polypeptides, such as CPPs and NLS, can facilitate nuclear entry and endosomal escape.

- CRISPR components can be delivered to cells using LNPs in various ways. The three techniques that are most frequently utilized are (1) encasing plasmid DNA (pDNA) encoding both Cas9 protein and gRNA or pDNA encoding Cas9 protein in conjunction with gRNA oligos, (2) Cas9 mRNA and gRNA, and (3) Cas9/sgRNA (protein/RNA) RNP complex. Each technique must apply specific LNP-specific formulation requirements to provide maximal compatibility without compromising function. Each method has advantages and disadvantages.

- The safety of therapeutic GE would be significantly increased by site-specific CRISPR-Cas delivery. Creating delivery systems responsive to CRISPR-Cas stimuli based on plasmids, RNA, and RNPs is also possible. In addition, pCas9 is given tissue- or cell-specific promoters to allow for the site-specific production of gRNA and Cas nuclease.

Nano Particles

Plasmid

Ribonucleoproteins (RNP)

Conclusions

Funding

Conflict of Interest

References

- Berg, P.; Baltimore, D.; Brenner, S.; Roblin, R.O.; Singer, M.F. Studies of the chemical nature of the transforming principle of pneumococcus. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Nucleic Acids and Protein Synthesis 1972, 269, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.H.; Hands, P.; Spence, J.A.; Dyer, T.A. Plant cells contain functional chimeric genes after transformation. Nature 1983, 303, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Malzahn, A.A.; Sretenovic, S.; Qi, Y. The emerging and uncultivated potential of CRISPR technology in plant science. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 778–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Yan, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, L. Knockout of the allergenic 27 kDa γ-gliadins in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L. ) by CRISPR/Cas9. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2020, 18, 1424–1426. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Ramsay, J.A.; Ramsay, B.A. Acetone extraction of mcl-PHA from Pseudomonas putida KT2440. J. Microbiol. Methods 2016, 8, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esvelt, K.M.; Gemmell, N.J. Conservation demands safe gene drive. PLOS Biol. 2017, 15, e2003850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Alper, H.S. Draft genome sequence of the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica PO1f, a commonly used metabolic engineering host. Genome Announcements 2014, 2, e00528–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.A.; Silver, P.A.; Collins, J.J.; Yin, P. Toehold Switches: De-Novo-Designed Regulators of Gene Expression. Cell 2014, 159, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, R.F.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Delgado-Ramos, L.; Mellado, M. Gene editing for the efficient generation of biopolymers in Yarrowia lipolytica. Journal of Fungi 2019, 5, 69. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Rodriguez, J.; Moser, F.; Song, M.; Voigt, C.A. Engineering RGB color vision into Escherichia coli. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 706–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, N.; Min, M.K.; Choi, E.H.; Kim, N.; Moon, S.J.; Yoon, I.; Kwon, T.; Jung, K.H.; Kim, B.G. Overexpression of OsARD1 Improves Submergence, Drought, and Salt Tolerances of Seedling Through the Enhancement of Ethylene Synthesis in Rice. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11, 983. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, B. Mammoth 2. 0: Will genome engineering resurrect extinct species? Genome Biology 2015, 16, 228. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Kerkhof, L.J. Microbial response to acid and base stress. In Microbiome Convergence; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kyrou, K.; Hammond, A.M.; Galizi, R.; Kranjc, N.; Burt, A.; Beaghton, A.K.; Nolan, T.; Crisanti, A. A CRISPR–Cas9 gene drive targeting doublesex causes complete population suppression in caged Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 1062–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bess, M. Icarus 2.0: A Historian's Perspective on Human Biological Enhancement. Technol. Cult. 2015, 56, 461–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mans, R.; Van Rossum, H.M.; Wijsman, M.; Backx, A.; Kuijpers, N.G.; Broek, M.V.D.; Daran-Lapujade, P.; Pronk, J.T.; Van Maris, A.J.; Daran, J.-M.G. CRISPR/Cas9: a molecular Swiss army knife for simultaneous introduction of multiple genetic modifications in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2018, 18, foy012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Bortesi, L.; Baysal, C.; Twyman, R.M.; Fischer, R.; Capell, T.; Schillberg, S.; Christou, P. Characteristics of Genome Editing Mutations in Cereal Crops. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cheng, X.; Shan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Gao, C.; Qiu, J.-L. Simultaneous editing of three homoeoalleles in hexaploid bread wheat confers heritable resistance to powdery mildew. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 32, 947–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullard, A. Nature. Gene editing pipeline takes off. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41573-020-00096-y (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Alagoz, M.; Kherad, N. Advance genome editing technologies in the treatment of human diseases: CRISPR therapy (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 46, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMA. Expert meeting on GE technologies used in medicine development. 2017. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/events/expert-meeting-genome-editing-technologies-used-medicine-development (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Ho, B.X.; Loh, S.J.H.; Chan, W.K.; Soh, B.S. In Vivo GE as a Therapeutic Approach. Int J Mol Sci. 2018, 19, 2721. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6163904/ (accessed on 6 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Hong, W.; et al. Applications of GE technology in the targeted therapy of human diseases: mechanisms, advances and prospects. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2020, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Buhr, H.; Lebbink, R.J. Harnessing CRISPR to combat human viral infections. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2018, 54, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeder, M.L.; A Gersbach, C. Genome-editing Technologies for Gene and Cell Therapy. Mol. Ther. 2016, 24, 430–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadtmauer, E.A.; Fraietta, J.A.; Davis, M.M.; Cohen, A.D.; Weber, K.L.; Lancaster, E.; Mangan, P.A.; Kulikovskaya, I.; Gupta, M.; Chen, F.; et al. CRISPR-engineered T cells in patients with refractory cancer. Science 2020, 367, eaba7365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeder, M.L.; Stefanidakis, M.; Wilson, C.J.; Baral, R.; Barrera, L.A.; Bounoutas, G.S.; Bumcrot, D.; Chao, H.; Ciulla, D.M.; DaSilva, J.A.; et al. Development of a gene-editing approach to restore vision loss in Leber congenital amaurosis type 10. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naldini, L. Ex vivo gene transfer and correction for cell-based therapies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behr, M.; Zhou, J.; Xu, B.; Zhang, H. In vivo delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 therapeutics: Progress and challenges. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 2150–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, A. CRISPR in personalized medicine: Industry perspectives in gene editing. Semin. Perinatol. 2018, 42, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvakumar, S.C.; Preethi, K.A.; Ross, K.; Tusubira, D.; Khan, M.W.A.; Mani, P.; Rao, T.N.; Sekar, D. CRISPR/Cas9 and next generation sequencing in the personalized treatment of Cancer. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jin, Q.; Wang, L.; Xu, S.; Chen, K.; Li, L.; Zeng, T.; Fan, X.; et al. i-CRISPR: a personalized cancer therapy strategy through cutting cancer-specific mutations. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Available online: https://www.personalizedmedicinecoalition.org/Userfiles/PMC-Corporate/file/Personalized_Medicine_at_FDA_The_Scope_Significance_of_Progress_in_2021.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Hamosh, A.; Scott, A.F.; Amberger, J.; Valle, D.; McKusick, V.A. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM). Hum Mutat. 2000, 15, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganath, L.R.; Khedekar, P.; Iqbal, Z. Alkaptonuria, ochronosis, and ochronotic arthropathy. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 2020, 33, 280–291. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Y.; Gao, C.; Gong, H. Targeting DNAJC12 by CRISPR/Cas9 in the rat results in animal lethality and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Journal of genetics and genomics 2018, 45, 641–644. [Google Scholar]

- Kashtan, C.E.; Michael, A.F. Alport syndrome. Kidney International 2014, 66, 748–758. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.H.; Al-Chalabi, A. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2017, 377, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.J.; Childs, B.G.; Durik, M.; Wijers, M.E.; Sieben, C.J.; Zhong, J.; Saltness, R.A.; Jeganathan, K.B.; Verzosa, G.C.; Pezeshki, A.; et al. Naturally occurring p16Ink4a-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature 2016, 530, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citorik, R.J.; Mimee, M.; Lu, T.K. Sequence-specific antimicrobials using efficiently delivered RNA-guided nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 1141–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musunuru, K.; Pirruccello, J.P.; Do, R.; Peloso, G.M.; Guiducci, C.; Sougnez, C.; Garimella, K.V.; Fisher, S.; Abreu, J.; Barry, A.J.; et al. Exome Sequencing,ANGPTL3Mutations, and Familial Combined Hypolipidemia. New Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2220–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Kawai, T.; Akira, S. Pathogen Recognition by the Innate Immune System. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 30, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beales, P.L.; Elcioglu, N.; Woolf, A.S.; Parker, D.; A Flinter, F. New criteria for improved diagnosis of Bardet-Biedl syndrome: results of a population survey. J. Med Genet. 1999, 36, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.E.; Nixon, C.; Steward, C.G.; Gauvreau, K.; Maisenbacher, M.; Fletcher, M.; Geva, J.; Byrne, B.J.; Spencer, C.T. The Barth Syndrome Registry: Distinguishing disease characteristics and growth data from a longitudinal study. Am. J. Med Genet. Part A 2020, 182, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangoul, H.; Altshuler, D.; Cappellini, M.D.; Chen, Y.-S.; Domm, J.; Eustace, B.K.; Foell, J.; De La Fuente, J.; Grupp, S.; Handgretinger, R.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing for Sickle Cell Disease and β-Thalassemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swiech, L.; Heidenreich, M.; Banerjee, A.; Habib, N.; Li, Y.; Trombetta, J.; Sur, M.; Zhang, F. In vivo interrogation of gene function in the mammalian brain using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 384, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matalon, R.; Michals-Matalon, K. Spongy degeneration of the brain, Canavan disease: biochemical and molecular findings. Frontiers in Bioscience 2000, 5, D307–D311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rupp, L.J.; Schumann, K.; Roybal, K.T.; Gate, R.E.; Ye, C.J.; Lim, W.A.; Marson, A. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated PD-1 disruption enhances anti-tumor efficacy of human chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, R.; Grundmann, A.; Renz, P.; Hänseler, W.; James, W.S.; Cowley, S.A.; Moore, M.D. CRISPR-mediated genotypic and phenotypic correction of a chronic granulomatous disease mutation in human iPS cells. Exp. Hematol. 2017, 53, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, C.A.; Conlon, R.A. Delivering on the promise of gene editing for cystic fibrosis. Genes Dis. 2019, 6, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherqui, S.; Courtoy, P.J.; Specht, A.; Bukanov, N.; Gahl, W.A.; Igarashi, P. Autophagy induction can improve in vitro and in vivo cystinosis manifestations. Autophagy 2020, 16, 1268–1283. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.; Wang, J.; Tan, Y.; Beyer, A.I.; Xie, F.; Muench, M.O.; Kan, Y.W. Genome editing using CRISPR-Cas9 to create the HPFH genotype in HSPCs: An approach for treating sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 16, 1268–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Amoasii, L.; Mireault, A.A.; McAnally, J.R.; Li, H.; Sanchez-Ortiz, E.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Shelton, J.M.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Olson, E.N. Postnatal genome editing partially restores dystrophin expression in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy. Science 2016, 351, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A.; Bhatia, K.; Bressman, S.B.; DeLong, M.R.; Fahn, S.; Fung, V.S.; Hallett, M.; Jankovic, J.; Jinnah, H.A.; Klein, C.; et al. Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: A consensus update. Mov. Disord. 2019, 28, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonafont, J.; Mencía, Á.; García, M.; Torres, R.; Rodríguez, S.; Carretero, M.; Del Río, M. Clinically relevant correction of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa by dual sgRNA CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing. Molecular Therapy 2019, 27, 986–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toomes, C.; Bottomley, H.M.; Jackson, R.M.; Towns, K.V.; Scott, S.; Mackey, D.A.; Craig, J.E.; Jiang, L.; Yang, Z.; Trembath, R.; et al. Mutations in LRP5 or FZD4 Underlie the Common Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy Locus on Chromosome 11q. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 74, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rio, P.; Baños, R.; Lombardo, A.; Quintana-Bustamante, O.; Alvarez, L.; Garate, Z.; Genovese, P.; Almarza, E.; Valeri, A.; Díez, B.; et al. Targeted gene therapy and cell reprogramming in Fanconi anemia. EMBO Mol. Med. 2019, 6, 835–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Marti-Gutierrez, N.; Park, S.-W.; Wu, J.; Lee, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Koski, A.; Ji, D.; Hayama, T.; Ahmed, R.; et al. Correction of a pathogenic gene mutation in human embryos. Nature 2017, 548, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.Y.; Halevy, T.; Lee, D.R.; Sung, J.J.; Lee, J.S.; Yanuka, O.; Benvenisty, N. Reversion of FMR1 Methylation and Silencing by Editing the Triplet Repeats in Fragile X iPSC-Derived Neurons. Cell Reports 2015, 13, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, R.; Amaral, O.; Alves, S. Therapy of Gaucher disease: past, present and future perspectives. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 2017, 40, 853–867. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, L.; Frati, G.; Felix, T.; Hardouin, G.; Casini, A.; Wollenschlaeger, C.; Dubreil, L. Editing a α1-antitrypsin gene in the liver of newborn mice using zinc finger nucleases. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology 2020, 62, 114–120. [Google Scholar]

- Endo, M.; Fujii, K.; Sugita, K.; Saito, K.; Kohno, Y.; Miyashita, T. Nationwide survey of nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome in Japan revealing the low frequency of basal cell carcinoma. Am. J. Med Genet. Part A 2012, 158, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavani, G.; Laurent, M.; Fabiano, A.; Cantelli, E.; Sakkal, A.; Corre, G.; Monteilhet, V. Treatment of Hemophilia B: focus on gene therapy. Hematology and Medical Oncology 2020, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy, S.; et al. Systemic delivery of factor IX messenger RNA for protein replacement therapy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, E1941–E1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosman, A.E.; de Gussem, E.M.; Balemans, W.A.F.; Gauthier, A.; Westermann, C.J.J.; Snijder, R.J.; Post, M.C.; Mager, J.J. Screening children for pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: Evaluation of 18 years of experience. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2019, 54, 1572–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanin, G.; Azzedine, H.; Denora, P.; Boukhris, A.; Tazir, M.; Lossos, A.; Rosa, A.L.; Lerer, I.; Hamri, A.; Alegria, P.; et al. Mutations in SPG11 are frequent in autosomal recessive spastic paraplegia with thin corpus callosum, cognitive decline and lower motor neuron degeneration. Brain 2019, 131, 772–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.; Xue, W.; Chen, S.; Bogorad, R.L.; Benedetti, E.; Grompe, M.; Koteliansky, V.; A Sharp, P.; Jacks, T.; Anderson, D.G. Genome editing with Cas9 in adult mice corrects a disease mutation and phenotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 551–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebina, H.; Misawa, N.; Kanemura, Y.; Koyanagi, Y. Harnessing the CRISPR/Cas9 system to disrupt latent HIV-1 provirus. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, srep02510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bess, M. Icarus 2.0: A Historian's Perspective on Human Biological Enhancement. Technol. Cult. 2015, 56, 461–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing ameliorates neurotoxicity in mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2017, 127, 2719–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciak, J.; Płoski, R.; Pollak, A. Application of targeted gene panel sequencing and whole exome sequencing in neonates and infants with suspected genetic disorder. Journal of applied genetics 2020, 61, 341–349. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, M.P. Hypophosphatasia - aetiology, nosology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2017, 13, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, M.; Micalizzi, A.; Valente, E.M. Joubert syndrome: congenital cerebellar ataxia with the molar tooth. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 894–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuis, M.H.; Vasen, H.F.A. Correlations between mutation site in APC and phenotype of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): A review of the literature. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2007, 61, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Hollander, A.I.; et al. Leber congenital amaurosis: genes, proteins and disease mechanisms. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 2008, 27, 391–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhart, Z.; Pavlovic, Z.; Chandrashekhar, M.; Hart, T.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Robitaille, M.; Brown, K.R.; Jaksani, S.; Overmeer, R.; et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screens reveal a Wnt–FZD5 signaling circuit as a druggable vulnerability of RNF43-mutant pancreatic tumors. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, K.; Zelley, K.; Nichols, K.E.; Garber, J. Li-Fraumeni Syndrome. In GeneReviews(R); University of Washington, 2017; pp. 1993–2021. [Google Scholar]

- Giudicessi, J.R.; Ackerman, M.J. Genotype- and Phenotype-Guided Management of Congenital Long QT Syndrome. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2013, 38, 417–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, H.; Lynch, P.; Lanspa, S.; Snyder, C.; Lynch, J.; Boland, C. Review of the Lynch syndrome: history, molecular genetics, screening, differential diagnosis, and medicolegal ramifications. Clin. Genet. 2009, 76, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunger, J.M.; Murray, A.; O’Donnell, M.; Usprech, J.; Ding, Q.; Shoichet, M.S. Structural and behavioral interplay of myosin-II and actin in the Drosophila heart. Cell Reports 2017, 19, 507–520. [Google Scholar]

- Gammage, P.A.; Viscomi, C.; Simard, M.-L.; Costa, A.S.H.; Gaude, E.; Powell, C.A.; Van Haute, L.; McCann, B.J.; Rebelo-Guiomar, P.; Cerutti, R.; et al. Genome editing in mitochondria corrects a pathogenic mtDNA mutation in vivo. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1691–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valstar, M.J.; Ruijter, G.J.; van Diggelen, O.P.; Poorthuis, B.J.; Wijburg, F.A. Sanfilippo syndrome: a mini-review. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 2008, 31, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, S.; Wenning, G.; Low, P.A.; Brooks, D.; Mathias, C.J.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Wood, N.; Colosimo, C.; Durr, A.; Fowler, C.J.; et al. Second consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neurology 2008, 71, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Amoasii, L.; Mireault, A.A.; McAnally, J.R.; Li, H.; Sanchez-Ortiz, E.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Shelton, J.M.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Olson, E.N. Postnatal genome editing partially restores dystrophin expression in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy. Science 2016, 351, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, B.; Chandran, P.; Bhat, M.; Iarkov, A. Advances in CRISPR/Cas-mediated Gene Therapy in Alzheimer’s Disease. Current Gene Therapy 2020, 20, 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D.G.R.; E Baser, M.; McGaughran, J.; Sharif, S.; Howard, E.; Moran, A. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours in neurofibromatosis 1. J. Med Genet. 2005, 38, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.A.; Wang, Y.C.; Chuang, H.Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Lee, Y.S.; Chou, Y.H. Serum levels of bioactive lipids and Niemann-Pick disease severity. Journal of Lipid Research 2021, 62, 100037. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, P.D.; Lander, E.S.; Zhang, F. Development and Applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for Genome Engineering. Cell 2021, 157, 1262–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voit, R.A.; Hendel, A.; Pruett-Miller, S.M.; Porteus, M.H. Nuclease-mediated gene editing by homologous recombination of the human globin locus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 42, 1365–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Fattore, A.; Cappariello, A.; Teti, A. Genetics, pathogenesis and complications of osteopetrosis. Bone 2008, 42, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, B.; Klionsky, D.J. Autophagy wins the 2016 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine: Breakthroughs in baker's yeast fuel advances in biomedical research. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 114, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, H.P.; Young, W.F.; Eng, C. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. New England Journal of Medicine 2011, 365, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarrity, T.J.; Kulin, H.E.; Zaino, R.J. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 2000, 95, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, S.; Consugar, M.B.; Chapman, A.B.; Torres, V.E.; Guay-Woodford, L.M.; Grantham, J.J.; Bennett, W.M.; Meyers, C.M.; Walker, D.L.; Bae, K.; et al. Comprehensive Molecular Diagnostics in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 18, 2143–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordeaux, J.; Dubreil, L.; Deniaud, J.; Iacobelli, F.; Moreau, S.; Ledevin, M.; Cherel, Y. Efficient gene transfer into the CNS and peripheral tissues of newborn primates using AAV9 and a new synthetic AAV9 promoter. Molecular Therapy 2018, 26, 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Cheong, S.-A.; Lee, J.G.; Lee, S.-W.; Lee, M.S.; Baek, I.-J.; Sung, Y.H. Generation of knockout mice by Cpf1-mediated gene targeting. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 34, 808–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, T.; Firth, A.L.; Scripture-Adams, D.D.; Galic, Z.; Qualls, S.J.; Gilmore, W.B.; Ke, E.; Singer, O.; Anderson, L.S.; Bornzin, A.R.; et al. Lymphoid Regeneration from Gene-Corrected SCID-X1 Subject-Derived iPSCs. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 16, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago-Fernández, O.; Osorio, F.G.; Quesada, V.; Rodríguez, F.; Basso, S.; Maeso, D.; Rolas, L.; Barkaway, A.; Nourshargh, S.; Folgueras, A.R.; et al. Development of a CRISPR/Cas9-based therapy for Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.-H.; Tsai, Y.-T.; Justus, S.; Lee, T.-T.; Zhang, L.; Lin, C.-S.; Bassuk, A.G.; Mahajan, V.B.; Tsang, S.H. CRISPR Repair Reveals Causative Mutation in a Preclinical Model of Retinitis Pigmentosa. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartong, D.T.; Berson, E.L.; Dryja, T.P. Retinitis pigmentosa. The Lancet 2006, 368, 1795–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananiev, G.; Williams, E.C.; Li, H.; Chang, Q. Isogenic Pairs of Wild Type and Mutant Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC) Lines from Rett Syndrome Patients as In Vitro Disease Model. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e25255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, S.-H.; Aoyagi-Scharber, M.; Le, S.Q.; Vincelette, J.; Ohmi, K.; Bullens, S.; Wendt, D.J.; Christianson, T.M.; Tiger, P.M.N.; Brown, J.R.; et al. Delivery of an enzyme-IGFII fusion protein to the mouse brain is therapeutic for mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 14870–14875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeil, J.-A.; Hacein-Bey-Abina, S.; Payen, E.; Magnani, A.; Semeraro, M.; Magrin, E.; Caccavelli, L.; Neven, B.; Bourget, P.; El Nemer, W.; et al. Gene Therapy in a Patient with Sickle Cell Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piguet, F.; Alves, S.; Cartier, N. Clinical Gene Therapy for Neurodegenerative Diseases: Past, Present, and Future. Hum. Gene Ther. 2020, 31, 1264–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crino, P.B.; Nathanson, K.L.; Henske, E.P. The tuberous sclerosis complex. New England Journal of Medicine 2006, 355, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Farrer, L.; Arnos, K.S.; Asher, J.H.; Baldwin, C.T.; Diehl, S.R.; Friedman, T.B.; Greenberg, J.; Grundfast, K.M.; Hoth, C.; Lalwani, A.K. Locus heterogeneity for Waardenburg syndrome is predictive of clinical subtypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1994, 55, 728. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oshima, J.; Sidorova, J.M.; Monnat, R.J., Jr. Werner syndrome: clinical features, pathogenesis and potential therapeutic interventions. Ageing Research Reviews 2016, 33, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuris, J.A.; Thompson, D.B.; Shu, Y.; Guilinger, J.P.; Bessen, J.L.; Hu, J.H.; Maeder, M.L.; Joung, J.K.; Chen, Z.-Y.; Liu, D.R. Cationic lipid-mediated delivery of proteins enables efficient protein-based genome editing in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 33, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, T.G.; Bundey, S.E.; Macleod, A.F. Neurodegeneration and diabetes: UK nationwide study of Wolfram (DIDMOAD) syndrome. Lancet 1995, 346, 1458–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.Y.; Long, J.D.; Campo-Fernandez, B.; de Oliveira, S.; Cooper, A.R.; Romero, Z.; Kohn, D.B. Site-specific gene editing of human hematopoietic stem cells for X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome. Cell reports 2018, 23, 2606–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.; Wei, H.-J.; Lin, L.; George, H.; Wang, T.; Lee, I.-H.; Zhao, H.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Kan, Y.N.; Shrock, E.; et al. Inactivation of porcine endogenous retrovirus in pigs using CRISPR-Cas9. Science 2017, 357, 1303–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterham, H.R.; Ferdinandusse, S.; Wanders, R.J. Human disorders of peroxisome metabolism and biogenesis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research 2016, 1863, 922–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasimme, A. AMA Journal of Ethics. Why Include the Public in Gene Editing Governance Deliberation? 2019. Available online: https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/why-include-public-genome-editing-governance-deliberation/2019-12 (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Scheper, A. AMA Policies and Code of Medical Ethics’ Opinions Related to Human Genome Editing. AMA J. Ethic- 2019, 21, E1056–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew, P.; et al. Gene editing and CRISPR in the clinic: current and future perspectives. Biosci Rep 2020, 40, BSR20200127. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/strategy/support-policy-making/scientific-support-eu-policies/european-group-ethics_en (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Council of Europe. Ethics and Human Rights must guide any use of GE technologies in human beings. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/bioethics/-/ethics-and-human-rights-must-guide-any-use-of-genome-editing-technologies- in-human-beings (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Adashi, E.Y.; Cohen, I.G. Selective Regrets: The “Dickey Amendments” 20 Years Later. JAMA Forum Archive 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NExTRAC NIH. Available online: https://osp.od.nih.gov/policies/novel-and-exceptional-technology-and-research-advisory-committee-nextrac/ (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- NIH Guideline. Final Action Under the NIH Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules (NIH Guidelines). Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/04/26/2019-08462/final-action-under-the-nih-guidelines-for-research-involving-recombinant-or-synthetic-nucleic-acid (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Wang, D.C.; Wang, X. Off-target genome editing: A new discipline of gene science and a new class of medicine. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2019, 35, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendel, A.; Fine, E.J.; Bao, G.; Porteus, M.H. Quantifying on- and off-target genome editing. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Clinical Trials. Available online: https://www.cff.org/research-clinical-trials/types-cftr-mutations (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- FDA Approved Cell and Gene Therapy Products. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/approved-cellular-and-gene-therapy-products (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- EMA ATMP. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/advanced-therapy-medicinal-products-overview#advanced-therapies-in-the-product-lifecycle-section (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Alliance for Regenerative Medicine. Available online: https://www.mednous.com/gene-edited-therapies-produce-first-clinical-data (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Sharma, R.; Anguela, X.M.; Doyon, Y.; Wechsler, T.; DeKelver, R.C.; Sproul, S.; Paschon, D.E.; Miller, J.C.; Davidson, R.J.; Shivak, D.; et al. In vivo genome editing of the albumin locus as a platform for protein replacement therapy. Blood 2020, 136, 1447–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L.; Drugs. Cost of Gene Therapy Drugs. 2022. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/medical-answers/cost-kymriah-3331548/ (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Nadat, M. Researchers welcome $3.5-million haemophilia gene therapy — but questions remain. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-04327-7 (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Irvine, A. Paying for CRISPR Cures: The Economics of Genetic Therapies. Available online: https://innovativegenomics.org/news/paying-for-crispr-cures/ (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Komor, A.C.; Badran, A.H.; Liu, D.R. CRISPR-Based Technologies for the Manipulation of Eukaryotic Genomes. Cell 2017, 168, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platt, R.J.; Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yim, M.J.; Swiech, L.; Kempton, H.R.; Dahlman, J.E.; Parnas, O.; Eisenhaure, T.M.; Jovanovic, M.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9 Knockin Mice for Genome Editing and Cancer Modeling. Cell 2014, 159, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brokowski, C.; Adli, M. CRISPR Ethics: Moral Considerations for Applications of a Powerful Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoane-Vazquez, E.; Rodriguez-Monguio, R.; Szeinbach, S.L.; Visaria, J. Incentives for orphan drug research and development in the United States. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2007, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, O. Noncommunicable diseases: risk factors and regional strategies for prevention and care. East. Mediterr. Heal. J. 2004, 10, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.R.; Ochalek, J.; Wouters, O.J.; Birger, M.; Chakraborty, S.; Morton, A. Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage: Applying principles to difficult cases. Health Systems & Reform 2018, 4, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mostaghim, S.R.; Gagne, J.J.; Kesselheim, A.S. Safety related label changes for new drugs after approval in the US through expedited regulatory pathways: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2017, 358, j3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, A.; Giedion, U.; Smith, P.C. What’s in, what’s out: designing benefits for universal health coverage; The World Bank, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Claussnitzer, M.; Cho, J.H.; Collins, R.; Cox, N.J.; Dermitzakis, E.T.; Hurles, M.E.; Kathiresan, S.; Kenny, E.E.; Lindgren, C.M.; MacArthur, D.G.; et al. A brief history of human disease genetics. Nature 2020, 577, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Gene Editing Market Report (2021). Data Bridge Market Research.

- Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 2014, 346, 1258096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, L.; Ran, F.A.; Cox, D.; Lin, S.; Barretto, R.; Habib, N.; Hsu, P.D.; Wu, X.; Jiang, W.; Marraffini, L.A.; et al. Multiplex Genome Engineering Using CRISPR/Cas Systems. Science 2013, 339, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knott, G.J.; Doudna, J.A. CRISPR-Cas guides the future of genetic engineering. Science 2018, 361, 866–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juergens, R.A.; et al. The promise of molecularly targeted and immunotherapy against lung cancer. Seminars in radiation oncology 2018, 28, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Stadtmauer, E.A.; Fraietta, J.A.; Davis, M.M.; Cohen, A.D.; Weber, K.L.; Lancaster, E.; Mangan, P.A.; Kulikovskaya, I.; Gupta, M.; Chen, F.; et al. CRISPR-engineered T cells in patients with refractory cancer. Science 2020, 367, eaba7365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). Human Genome Editing: Science, Ethics, and Governance. National Academies Press.

- Cyranoski, D.; Ledford, H. Genome-edited baby claim provokes international outcry. Nature 2018, 563, 607–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ding, C.; Huang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Lv, J.; Xie, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in human tripronuclear zygotes. Protein Cell 2019, 10, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advisory committee on developing global standards for governance and oversight of Human Genome editing. (2019, December 18). World Health Organization.

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A Programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangoul, H.; Altshuler, D.; Cappellini, M.D.; Chen, Y.-S.; Domm, J.; Eustace, B.K.; Foell, J.; De La Fuente, J.; Grupp, S.; Handgretinger, R.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing for Sickle Cell Disease and β-Thalassemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esrick, E.B.; Lehmann, L.E.; Biffi, A.; Achebe, M.; Brendel, C.; Ciuculescu, M.F.; Daley, H.; MacKinnon, B.; Morris, E.; Federico, A.; et al. Post-Transcriptional Genetic Silencing ofBCL11Ato Treat Sickle Cell Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA approves CAR-T cell therapy to treat adults with certain types of large B-cell lymphoma. (2017, October 18). U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- Long, C.; Amoasii, L.; Mireault, A.A.; McAnally, J.R.; Li, H.; Sanchez-Ortiz, E.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Shelton, J.M.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Olson, E.N. Postnatal genome editing partially restores dystrophin expression in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy. Science 2016, 351, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, C.; Amoasii, L.; Mireault, A.A.; McAnally, J.R.; Li, H.; Sanchez-Ortiz, E.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Shelton, J.M.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Olson, E.N. Postnatal genome editing partially restores dystrophin expression in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy. Science 2016, 351, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frangoul, H.; Altshuler, D.; Cappellini, M.D.; Chen, Y.-S.; Domm, J.; Eustace, B.K.; Foell, J.; De La Fuente, J.; Grupp, S.; Handgretinger, R.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing for Sickle Cell Disease and β-Thalassemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; et al. Design and specificity of long ssDNA donors for CRISPR-based knock-in. BioRxiv 2019, 530824. [Google Scholar]

- Wianny, F.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Specific interference with gene function by double-stranded RNA in early mouse development. Nature 2000, 2, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyranoski, D. CRISPR gene-editing tested in a person for the first time. Nature 2016, 539, 479–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Kaminski, R.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Cosentino, L.; Li, F.; Luo, B.; Alvarez-Carbonell, D.; Garcia-Mesa, Y.; Karn, J.; et al. RNA-directed gene editing specifically eradicates latent and prevents new HIV-1 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 11461–11466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebas, P.; Stein, D.; Tang, W.W.; Frank, I.; Wang, S.Q.; Lee, G.; Spratt, S.K.; Surosky, R.T.; Giedlin, M.A.; Nichol, G.; et al. Gene Editing of CCR5 in Autologous CD4 T Cells of Persons Infected with HIV. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-H.; Tee, L.Y.; Wang, X.-G.; Huang, Q.-S.; Yang, S.-H. Off-target effects in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome engineering. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2015, 4, e264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosicki, M.; Tomberg, K.; Bradley, A. Repair of double-strand breaks induced by CRISPR–Cas9 leads to large deletions and complex rearrangements. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinstiver, B.P.; Pattanayak, V.; Prew, M.S.; Tsai, S.Q.; Nguyen, N.T.; Zheng, Z.; Joung, J.K. High-fidelity CRISPR–Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature 2016, 529, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlesworth, C.T.; Deshpande, P.S.; Dever, D.P.; Camarena, J.; Lemgart, V.T.; Cromer, M.K.; Vakulskas, C.A.; Collingwood, M.A.; Zhang, L.; Bode, N.M.; et al. Identification of preexisting adaptive immunity to Cas9 proteins in humans. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, D.L.; Amini, L.; Wendering, D.J.; Burkhardt, L.-M.; Akyüz, L.; Reinke, P.; Volk, H.-D.; Schmueck-Henneresse, M. High prevalence of Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9-reactive T cells within the adult human population. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.; Kauffman, K.J.; Anderson, D.G. Delivery technologies for genome editing. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-X.; Li, M.; Lee, C.M.; Chakraborty, S.; Kim, H.-W.; Bao, G.; Leong, K.W. CRISPR/Cas9-Based Genome Editing for Disease Modeling and Therapy: Challenges and Opportunities for Nonviral Delivery. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 9874–9906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, R.; Bojar, D.; Rizzi, G.; Hamri, G.C.-E.; El-Baba, M.D.; Saxena, P.; Ausländer, S.; Tan, K.R.; Fussenegger, M. Designer exosomes produced by implanted cells intracerebrally deliver therapeutic cargo for Parkinson’s disease treatment. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Conboy, M.; Park, H.M.; Jiang, F.; Kim, H.J.; Dewitt, M.A.; Mackley, V.A.; Chang, K.; Rao, A.; Skinner, C.; et al. Nanoparticle delivery of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein and donor DNA in vivo induces homology-directed DNA repair. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.; Kim, J.S. Therapeutic opportunities and challenges of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing: a review. Yonsei Medical Journal 2020, 61, 357–368. [Google Scholar]

- Komor, A.C.; Badran, A.H.; Liu, D.R. CRISPR-Based Technologies for the Manipulation of Eukaryotic Genomes. Cell 2017, 169, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Kauffman, K.J.; Anderson, D.G. Delivery technologies for genome editing. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brokowski, C.; Adli, M. CRISPR Ethics: Moral Considerations for Applications of a Powerful Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, T.; Parker, N.; Ylä-Herttuala, S. History of gene therapy. Gene 2013, 525, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylis, F.; McLeod, M. First-in-human phase 1 CRISPR gene editing cancer trials: Are we ready? Current Gene Therapy 2017, 17, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, H.A.; Liu, D.R. Base editing: precision chemistry on the genome and transcriptome of living cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 770–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, A.V.; Randolph, P.B.; Davis, J.R.; Sousa, A.A.; Koblan, L.W.; Levy, J.M.; Chen, P.J.; Wilson, C.; Newby, G.A.; Raguram, A.; et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature 2019, 576, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Kaminski, R.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Cosentino, L.; Li, F.; Luo, B.; Alvarez-Carbonell, D.; Garcia-Mesa, Y.; Karn, J.; et al. RNA-directed gene editing specifically eradicates latent and prevents new HIV-1 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 11461–11466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, H.; Gao, C. CRISPR/Cas Genome Editing and Precision Plant Breeding in Agriculture. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2019, 70, 667–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). Human genome editing: Science, ethics, and governance. National Academies Press.

- Brokowski, C.; Adli, M. CRISPR Ethics: Moral Considerations for Applications of a Powerful Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuffield Council on Bioethics. (2016). Genome editing: An ethical review. Nuffield Council on Bioethics.

- Parens, E.; Johnston, J. Does it make sense to speak of “genetic enhancements?”. The Hastings Center Report 2007, 37 (Suppl. S1), S41–S49. [Google Scholar]

- Borry, P.; Bentzen, H.B.; Budin-Ljøsne, I.; Cornel, M.C.; Howard, H.C.; Feeney, O.; Jackson, L.; Mascalzoni, D.; Mendes, Á.; Peterlin, B.; et al. The challenges of the expanded availability of genomic information: an agenda-setting paper. J. Community Genet. 2020, 11, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, M.; Ishii, T. International regulatory landscape and integration of corrective genome editing into in vitro fertilization. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2014, 12, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Food and Drug Administration. (2020). Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Control (CMC) Information for Human Gene Therapy Investigational New Drug Applications (INDs). FDA.

- European Medicines Agency. (2018). Guideline on the quality, non-clinical and clinical aspects of gene therapy medicinal products. EMA.

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, Z.Q.; Tian, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Chen, Y. Ethical norms and the international governance of genetic databases and biobanks: findings from an international study. The Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 2016, 18, 101–124. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Tatay, L.; Hernández-Andreu, J.M.; Aznar, J. Human germline editing: the need for ethical guidelines. The Linacre Quarterly 2017, 84, 275–282. [Google Scholar]

- Araki, M.; Ishii, T. International regulatory landscape and integration of corrective genome editing into in vitro fertilization. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2014, 12, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directive 2001/18/ EC on the deliberate release into the environment of GMOs; Directive 2009/41/EC on the contained use of genetically modified micro-organisms. Accessed 6 March 2023.

- FDA. Long Term Follow-Up After Administration of Human Gene Therapy Products; Guidance for Industry, January 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/113768/download (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- European Council. Advanced Therapies. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/human-use/advanced-therapies_en#1 (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Mourby, M.; Morrison, M. Gene therapy regulation: could in-body editing fall through the net? Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 28, 979–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfeir, A.; Symington, L.S. Microhomology-Mediated End Joining: A Back-up Survival Mechanism or Dedicated Pathway? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIH. First Restriction Enzyme Described. 1968. Available online: https://www.genome.gov/25520301/online-education-kit-1968-first-restriction-enzymes-described (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- https://www.labome.com/method/CRISPR-and-Genomic-Engineering.html.

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001877.g001. [CrossRef]

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001877.g002. [CrossRef]

- Kantor, A.; McClements, M.E.; MacLaren, R.E. CRISPR-Cas9 DNA Base-Editing and Prime-Editing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Xin, X.; Hu, M.; Price, M.A.; Rosser, S.J.; Bi, C.; Zhang, X. Glycosylase base editors enable C-to-A and C-to-G base changes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical Trias; Base Editors. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=&term=base+editor+&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=&Search=Search (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- CRISPR News Medicine. MegaNuclease Clinical Trials. Available online: https://crisprmedicinenews.com/clinical-trials/meganuclease-clinical-trials/ (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Hall, B.; Limaye, A.; Kulkarni, A.B. Overview: Generation of Gene Knockout Mice. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. 2009, 44, 19–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijlani, S.; Pang, K.M.; Sivanandam, V.; Singh, A.; Chatterjee, S. The Role of Recombinant AAV in Precise Genome Editing. Front. Genome Ed. 2022, 3, 799722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimi, K.; et al. ssODN-mediated knock-in with CRISPR-Cas for large genomic regions in zygotes. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 10431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montague, M.G.; Lartigue, C.; Vashee, S. Synthetic genomics: potential and limitations. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Deng, L.; Chen, G. Mechanisms and applications of peptide nucleic acids selectively binding to double-stranded RNA. Biopolymers 2022, 113, e23476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutvagner, G.; Simard, M.J. Argonaute proteins: key players in RNA silencing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, B.; Freudenreich, O.; Worth, J.L. Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. 2010, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, T. Non-Enzymatic Functions of Retroviral Integrase: The Next Target for Novel Anti-HIV Drug DLi, yevelopment. Frontiers in Microbiology 2011, 2, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.Y.; He, X.Y.; Zhuo, R.X.; Cheng, S.X. Reversal of tumor malignization and modulation of cell behaviors through GE mediated by a multi-functional nanovector. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 21209–21218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, K.; et al. The NIH Somatic Cell GE program. Nature 2021, 592, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotterman, M.A.; Schaffer, D.V. Engineering adeno-associated viruses for clinical gene therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis; Arvin, A., Campadelli-Fiume, G., Mocarski, E., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W. Nucleases: diversity of structure, function and mechanism. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2011, 44, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niazi, S.K. Making COVID-19 mRNA vaccines accessible: challenges resolved. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2022, 21, 1163–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.-S.; Gong, S.; Yu, H.-H.; Jung, K.; Johnson, K.A.; Taylor, D.W. Engineered CRISPR/Cas9 enzymes improve discrimination by slowing DNA cleavage to allow release of off-target DNA. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesqué, D.; Pujol, R.M.; Marcantonio, O.; Vidal-Navarro, A.; Ramada, J.M.; Arderiu-Formentí, A.; Albalat-Torres, A.; Serra, C.; Giménez-Arnau, A.M. Study of Excipients in Delayed Skin Reactions to mRNA Vaccines: Positive Delayed Intradermal Reactions to Polyethylene Glycol Provide New Insights for COVID-19 Arm. Vaccines 2022, 10, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinc, A. The Onpattro Story and the Clinical Translation of Nanomedicines Containing Nucleic Acid-Based Drugs. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 1084–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, A. Lipid-Based Nanoparticles as Pharmaceutical Drug Carriers: From Concepts to Clinic. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 2009, 26, 523–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemian, P.; Yu, S.-Y.; Thomson, S.B.; Birkenshaw, A.; Leavitt, B.R.; Ross, C.J.D. Lipid-Nanoparticle-Based Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 Genome-Editing Components. Mol. Pharm. 2022, 19, 1669–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili Mohanna, S.Z.; Djaksigulova, D.; Hill, A.M.; Wagner, P.K.; Simpson, E.M.; Leavitt, B.R. LNP-mediated delivery of CRISPR RNP for wide-spread in vivo GE in mouse cornea. J Control Release. 2022, 350, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.; Wu, J.; Li, H.; Ma, G. Recent research and development of PLGA/PLA microspheres/nanoparticles: A review in scientific and industrial aspects. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2018, 13, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Zapata, D.; Tang, Y.; Teng, Y.; Li, Y. In vivo delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 GE components for therapeutic applications. Biomaterials. 2022, 291, 121876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.J.; Billingsley, M.M.; Haley, R.M.; Wechsler, M.E.; Peppas, N.A.; Langer, R. Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jouannet, P. CRISPR-Cas9, germinal cells and human embryo. Biol. Aujourd’hui 2017, 211, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, J.D.; et al. A Single Administration of CRISPR/Cas9 Lipid Nanoparticles Achieves Robust and Persistent In Vivo Genome Editing. Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 2227–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Ji, W.; Hall, J.M.; Hu, Q.; Wang, C.; Beisel, C.L.; Gu, Z. Self-Assembled DNA Nanoclews for the Efficient Delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 for Genome Editing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 12029–12033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Conboy, M.; Park, H.M.; Jiang, F.; Kim, H.J.; Dewitt, M.A.; Mackley, V.A.; Chang, K.; Rao, A.; Skinner, C.; et al. Nanoparticle delivery of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein and donor DNA in vivo induces homology-directed DNA repair. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Ouyang, K.; Xu, X.; Xu, L.; Wen, C.; Zhou, X.; Qin, Z.; Xu, Z.; Sun, W.; Liang, Y. Nanoparticle Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 for Genome Editing. Front. Genet. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, K.; et al. The NIH Somatic Cell GE program. Nature 2021, 592, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, S. Clever CRISPR Advances. Wang H, Yet. al., (May 2013). “One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering”. Cell 2016, 153, 910–918. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Q.; Li, W.; Mao, L.; Wang, M. Nanoscale metal–organic frameworks for the intracellular delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing machinery. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 7024–7033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Agriculture and Livestock Breeding: Crop improvement and livestock breeding, with the potential to significantly enhance global food security.[3] |

| Allergy-Free Foods: To create versions of common foods that don’t trigger allergic reactions. For example, researchers have used gene editing to create a variety of wheat that does not produce the proteins that cause most wheat allergies.[4] |

| Biodegradable Plastics: Editing the genes of certain bacteria to make them produce biodegradable plastics, offering an environmentally friendly alternative to conventional plastics.[5] |

| Biodiversity Conservation: To bolster conservation efforts by creating white-footed mice immune to the bacteria causing Lyme disease.[6] |

| Biofuel Production: To engineer microbes or plants to produce biofuels more efficiently.[7] |

| Biological Computers: To build biological computers inside living cells to perform complex computations. [8] |

| Biomaterials: Create organisms that produce new kinds of biomaterials with unique properties, opening various industrial and scientific applications.[9] |

| Biosensors Development: Engineer cells to detect specific molecules or conditions, creating biosensors for various applications, from medical diagnostics to environmental monitoring.[10] |

| Climate Change Effects: To genetically engineer crops to withstand better the effects of climate change, such as increased drought or higher salinity.[11] |

| De-extinction of Extinct Species: To bring extinct species back to life, or “de-extinction.” This would involve using DNA from preserved specimens to edit the genes of a closely related existing species.[12] |

| Environmental Decontamination: Genetically edited bacteria could clean up ecological contaminants like oil spills or nuclear waste.[13] |

| Gene Drives: Gene drives using CRISPR/Cas9 systems have been proposed to control disease vectors such as mosquitoes that spread malaria.[14] |

| Human Augmentation: While controversial, gene editing technologies like CRISPR have raised the possibility of enhancing human abilities beyond normal levels, or “human enhancement.”[15] |

| Industrial Yeast Strains: Industrial yeasts produce biofuels and various chemicals. Gene editing can improve the efficiency and versatility of these yeasts.[16] |

| Nutritional Profile of Crops: Gene editing can enhance the nutritional content of food crops, potentially addressing malnutrition problems in areas of the world where specific nutrient deficiencies are common.[17] |

| Plant Disease Resistance: Gene editing can increase the resistance of crops to various diseases, potentially leading to higher yields and food security.[18] |

| Alkaptonuria: A metabolic disorder that leads to a buildup of homogentisic acid, causing various symptoms, including dark-colored urine. Gene editing could correct the HGD gene, which causes this condition.[35] |

| Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency: This genetic disorder can lead to lung and liver disease. Gene editing technologies can potentially correct the faulty SERPINA1 gene that causes it.[36] |

| Alport Syndrome: A genetic disorder characterized by kidney disease, hearing loss, and eye abnormalities. Gene editing could correct the COL4A3, COL4A4, or COL4A5 genes, which cause this condition.[37] |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): A group of neurological diseases mainly involving the nerve cells (neurons) responsible for controlling voluntary muscle movement. Gene editing might correct the SOD1, TARDBP, FUS, or C9orf72 genes, which can cause this condition.[38] |

| Anti-Aging Research: Genetic modification of senescent cells has been proposed to counteract aging. [39] |

| Antimicrobial Resistance: Gene editing can potentially counteract the growing problem of antibiotic resistance by directly targeting and killing antibiotic-resistant bacteria or by making the bacteria sensitive to antibiotics again.[40] |

| Atherosclerosis: Gene editing can potentially treat atherosclerosis, a disease where plaque builds up inside the arteries. Using gene editing techniques to modify the PCSK9 gene, which controls LDL cholesterol levels, could potentially lower the risk of atherosclerosis.[41] |

| Autoimmune Diseases: With autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, gene editing could modify immune cells and prevent them from attacking the body’s tissues.[42] |

| Bardet-Biedl Syndrome: A disorder that affects many parts of the body and can cause obesity, loss of vision, kidney abnormalities, and extra fingers or toes. Gene editing could correct any 21 genes that cause this condition, such as BBS1, BBS2, or BBS10.[43] |

| Barth Syndrome: A genetic disorder characterized by muscle weakness, delayed growth, and sometimes intellectual disability. Gene editing could correct the TAZ gene, which causes this condition.[44] |

| Beta Thalassemia: Gene editing techniques have been used in attempts to treat beta-thalassemia, a blood disorder that reduces the production of hemoglobin. Researchers have manipulated the BCL11A gene to enhance the production of fetal hemoglobin as a workaround.[45] |

| Brain Function: Gene editing has been used in neuroscience to understand the function of different genes in the brain, which could eventually help us treat or even cure neurological disorders.[46] |

| Canavan Disease: A progressive, fatal neurological disorder that begins in infancy. Gene editing could correct the ASPA gene, which causes this condition.[47] |

| Cancer Therapies: CRISPR has been used to develop novel cancer therapies, such as genetically modifying a patient’s immune cells to target and fight cancer cells. [48] |

| Chronic Granulomatous Disease: Gene editing has been used to correct the genetic mutations that cause chronic granulomatous disease, a disorder that affects the immune system.[49] |

| Cystic Fibrosis: Gene editing technologies could correct the CFTR gene mutation that leads to cystic fibrosis, a disease affecting the lungs and digestive system.[50] |

| Cystinosis: A genetic disorder characterized by an accumulation of the amino acid cystine within cells, leading to various symptoms and complications. Gene editing technologies are being explored to correct the CTNS gene, which causes this condition.[51] |

| Diabetes: In Type 1 diabetes, the immune system destroys insulin-producing cells. Researchers are exploring gene editing as a potential approach to protect these cells from the immune system or to create new insulin-producing cells.[52] |

| Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: A severe type of muscular dystrophy. Gene editing has shown promise in correcting the gene mutation that causes this condition.[53] |

| Dystonia: A movement disorder in which a person’s muscles contract uncontrollably. Gene editing could correct any of the 20+ known genes that can cause this condition, such as TOR1A, THAP1, or GNAL.[54] |

| Epidermolysis Bullosa: Gene editing technologies can potentially correct the genetic mutations that cause epidermolysis bullosa, a group of genetic conditions that cause the skin to be very fragile and to blister easily.[55] |

| Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy: A hereditary disorder that can cause progressive vision loss. Gene editing could correct the FZD4, LRP5, TSPAN12, NDP, or ZNF408 genes, which cause this condition.[56] |

| Fanconi Anemia: A rare genetic disease resulting in bone marrow failure. Gene editing could correct the FANCC gene, one of the known genes that causes this condition when mutated.[57] |

| Fertility Treatments: Gene editing technology may be utilized to treat certain genetic disorders that cause infertility, offering hope to many individuals and couples who wish to have children.[58] |

| Fragile X Syndrome: A genetic disorder causing intellectual disability, behavioral and learning challenges, and various physical characteristics. Gene editing has been proposed as a potential way to correct the FMR1 gene that causes this condition.[59] |

| Gaucher Disease: A genetic disorder that affects the body’s ability to break down fats. Gene editing technologies are being explored to correct the GBA gene mutations that cause this condition.[60] |

| Glycogen Storage Disease Type Ia: A metabolic disorder caused by the deficiency of glucose-6-phosphatase, the enzyme necessary for the final step of gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. Gene editing technologies are being explored to correct the G6PC gene mutations that cause this condition.[61] |

| Gorlin Syndrome (Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome): A genetic condition that affects many parts of the body and increases the risk of developing various cancerous and noncancerous tumors. Gene editing could correct the PTCH1 gene, which causes this condition.[62] |

| Hemophilia A and B: A rare bleeding disorder where a person lacks or has low levels of specific proteins called “clotting factors.” Gene editing might correct the F8 or F9 genes, which cause Hemophilia A and B, respectively.[63] |

| Hereditary Angioedema: A rare genetic disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of severe swelling. Gene editing might correct the SERPING1 gene, which causes this condition.[64] |

| Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia: A genetic disorder of blood vessel formation causing multiple direct connections between arteries and veins. Gene editing could correct the ENG, ACVRL1, or SMAD4 gene, which can cause this condition.[65] |

| Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia: A group of inherited disorders characterized by progressive weakness and stiffness of the legs. Gene editing could correct the SPG11 gene, which causes one of the more common types of this disease.[66] |

| Hereditary Tyrosinemia Type 1: A rare genetic disorder characterized by multistep disruptions that break down the amino acid tyrosine. Gene editing could correct the FAH gene mutations causing this condition.[67] |

| HIV/AIDS: Gene editing technology has been used to eradicate HIV from infected cells. This is achieved by targeting the viral DNA integrated into the host genome.[68] |

| Human Augmentation: While controversial, gene editing technologies like CRISPR have raised the possibility of enhancing human abilities beyond normal levels, or “human enhancement.”[69] |

| Huntington’s Disease: This inherited disease causes the progressive breakdown of nerve cells in the brain. Gene editing could potentially correct or deactivate the gene that causes Huntington’s disease.[70] |

| Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A disease in which the heart muscle becomes abnormally thick, making it harder for the heart to pump blood. Gene editing might correct the MYH7 gene, which causes this condition.[71] |

| Hypophosphatasia: A metabolic disease that disrupts mineralization, processes in which minerals such as calcium and phosphorus are deposited in developing bones and teeth. Gene editing could correct the ALPL gene, which causes this condition.[72] |

| Joubert Syndrome: A genetic disorder characterized by decreased muscle tone, difficulties with coordination, abnormal eye movements, and breathing problems. Gene editing could correct any of the 35 genes that cause this condition, such as AHI1, CEP290, or TMEM67.[73] |

| Juvenile Polyposis Syndrome: A genetic condition characterized by multiple polyps in the gastrointestinal tract. Gene editing could correct the BMPR1A or SMAD4 genes, which cause this condition.[74] |

| Leber Congenital Amaurosis: An eye disorder that primarily affects the retina. Gene editing could correct any of the 14 known genes that can cause this condition, such as GUCY2D, RPE65, or CEP290.[75] |

| Leukemia: Certain forms of leukemia are caused by specific genetic mutations. Gene editing could potentially correct these mutations, leading to improved treatment outcomes.[76] |

| Li-Fraumeni Syndrome: A rare, hereditary disorder that greatly increases the risk of developing several types of cancer, particularly in young adults and children. Gene editing could correct the TP53 gene, which causes this condition.[77] |

| Long QT Syndrome: A disorder of the heart’s electrical activity that can cause sudden, uncontrollable, and irregular heartbeats (arrhythmias), which may lead to premature death. Gene editing could correct any of the 17 known genes that can cause this condition, such as KCNQ1, KCNH2, or SCN5A.[78] |

| Lynch Syndrome: A genetic condition that increases the risk of many types of cancer, particularly colorectal cancers. Gene editing could correct the MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, or PMS2 genes, which cause this condition.[79] |

| Marfan Syndrome: A genetic disorder affecting the body’s connective tissue. Gene editing has been proposed to correct the faulty gene that causes this syndrome.[80] |

| Mitochondrial Diseases: Mitochondrial diseases often result from mutations in the mitochondrial DNA. Scientists have used gene editing techniques to eliminate mutated mitochondrial DNA and prevent these diseases selectively.[81] |

| Mucopolysaccharidosis: A group of metabolic disorders caused by the absence or malfunctioning of lysosomal enzymes needed to break down molecules called glycosaminoglycans. Gene editing could correct any of the 11 known genes that cause these conditions.[82] |

| Multiple System Atrophy: A rare neurodegenerative disorder characterized by autonomic dysfunction, parkinsonism, and ataxia. Gene editing could investigate and possibly correct the underlying genetic contributors to this condition, which are not yet fully understood.[83] |

| Muscular Dystrophy: Scientists have used gene editing to correct the mutation that causes Duchenne muscular dystrophy in animal models, and clinical trials are in the works.[84] |

| Neurodegenerative Disorders: Gene editing can be employed to study and potentially treat neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and Huntington’s disease by targeting the specific genes involved in these conditions.[85] |

| Neurofibromatosis: Genetic disorders that cause tumors to form on nerve tissue. Gene editing could correct the NF1 or NF2 genes that cause these conditions.[86] |

| Niemann-Pick Disease: A group of severe inherited metabolic disorders in which sphingomyelin accumulates in cell lysosomes. Gene editing could correct the SMPD1 gene, which causes type A and B of this disease.[87] |

| Oculocutaneous Albinism: A group of conditions that affect the coloring (pigmentation) of the skin, hair, and eyes. Gene editing could correct the OCA2 gene, causing some forms of this condition.[88] |

| Osteogenesis Imperfecta: This group of genetic disorders mainly affects the bones, resulting in bones that break easily. Gene editing could correct or compensate for the faulty genes causing these conditions.[89] |

| Osteopetrosis: A group of rare, genetic bone disorders that result in the bone being overly dense. Gene editing could correct the TCIRG1, CLCN7, or SNX10 genes, which cause this condition.[90] |

| Pantothenate Kinase-Associated Neurodegeneration (PKAN): A type of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Gene editing could correct the PANK2 gene, which causes this condition.[91] |

| Paraganglioma and Pheochromocytoma: Rare neuroendocrine tumors originating in the adrenal glands or near specific nerves and blood vessels. Gene editing could correct the SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD, SDHAF2, VHL, RET, NF1, TMEM127, or MAX genes, which can cause these conditions.[92] |

| Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome: A genetic condition characterized by the development of noncancerous growths called hamartomatous polyps in the gastrointestinal tract and a significantly increased risk of developing certain types of cancer. Gene editing could correct the STK11 gene, which causes this condition.[93] |

| Polycystic Kidney Disease: A genetic disorder characterized by the growth of numerous cysts in the kidneys. Gene editing might correct the PKD1 or PKD2 genes, which cause this condition.[94] |

| Pompe Disease: A metabolic disorder caused by the buildup of a complex sugar called glycogen within cells. Gene editing could correct the GAA gene, which causes this condition.[95] |

| Prader-Willi Syndrome: This is a complex genetic condition that affects many parts of the body, causing weak muscle tone, feeding difficulties, poor growth, and delayed development. Using gene editing to reactivate the silenced paternal copy of the genes could provide a cure.[96] |

| Primary Immunodeficiencies: Gene editing may provide treatments for primary immunodeficiencies, like severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), where gene alterations affect the immune system’s development and function.[97] |

| Progeria: Gene editing technology has shown promise in treating Progeria (also known as Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome), a rare, fatal genetic disorder characterized by an appearance of accelerated aging in children. Gene editing can potentially correct the mutation in the LMNA gene associated with this disease.[98] |

| Restoring Sight: Researchers have used gene editing to restore sight in blind mice, which could eventually lead to treatments for certain forms of inherited blindness in humans.[99] |

| Retinal Diseases: Gene editing holds promise in treating inherited retinal diseases. Scientists have successfully used gene editing techniques to correct a mutation causing Leber congenital amaurosis, inherited blindness—breakdown, and loss of cells in the retina. Gene editing might correct any of the 60+ known genes that can cause this condition, such as RHO, RPGR, or USH2A.[100] |

| Rett Syndrome: A rare genetic disorder causing severe cognitive and physical impairments. Gene editing could potentially reactivate the silenced MECP2 gene that causes Rett syndrome.[101] |

| Sanfilippo Syndrome: A type of Mucopolysaccharidosis, Sanfilippo syndrome is characterized by the body’s inability to break down certain sugars properly. Gene editing technologies are being developed to correct the SGSH gene, which causes this condition.[102] |

| Sickle Cell Disease: Gene editing has shown promise in correcting the genetic mutation responsible for sickle cell disease, which causes misshapen red blood cells.[103] |

| Spinocerebellar Ataxias: These are a group of genetic diseases characterized by degenerative changes in the part of the brain related to the control of movement. Gene editing techniques have been applied in experimental models to correct the associated genetic mutations.[104] |

| Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: A genetic disorder characterized by the growth of numerous noncancerous (benign) tumors in many body parts. Gene editing could correct the TSC1 or TSC2 genes that cause this condition.[105] |

| Waardenburg Syndrome: A group of genetic conditions that can cause hearing loss and changes in coloring (pigmentation) of the hair, skin, and eyes. Gene editing could correct the PAX3 or MITF genes, which cause this condition.[106] |

| Werner Syndrome: A disorder characterized by the premature appearance of features associated with normal aging. Gene editing could correct the WRN gene, which causes this condition.[107] |

| Wilson Disease: A condition in which copper builds up in the body, potentially leading to life-threatening organ damage. Gene editing might correct the ATP7B gene mutations causing Wilson’s disease.[108] |

| Wolfram Syndrome: A genetic disorder characterized by diabetes mellitus and progressive vision loss. Gene editing could correct the WFS1 or CISD2 genes, which cause this condition.[109] |

| X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia: Gene editing can potentially correct mutations in the BTK gene, which cause X-linked agammaglobulinemia, an immune system disorder that leaves the body prone to infections.[110] |

| Xenotransplantation: Researchers have used gene editing to remove retroviruses from pig genomes, bringing us one step closer to pig-to-human organ transplants.[111] |

| Zellweger Spectrum Disorder: A group of conditions that can affect many body parts. Gene editing could correct any 12 PEX genes known to cause these conditions.[112] |

| Product | Developer | Indication |

| ABECMA (idecabtagene vicleucel) | Celgene Corporation | Adult patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma after four or more prior lines of therapy, including an immunomodulatory agent, a proteasome inhibitor, and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody. |