1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are main cause of death worldwide and are responsible for about 32% of all global deaths [

1]. Thrombosis is a severe CVD complication characterized by the pathological formation of fibrin clots that cause obstruction of blood flow, leading to intense clinical manifestations such as acute ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, and venous thromboembolism [

2,

3].

In general, conventional thrombosis treatment are based on antiplatelet or anticoagulant agents, which can cause severe bleeding leading to hemorrhage [

4,

5]. Alternatively, fibrinolytic enzymes such as tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA), urokinase (u-PA), and streptokinase have been widely used for thrombosis therapy. However, these drugs have some limitations including short half-life, low specificity to fibrin, high cost, and excessive bleeding [

6]. Thus, finding more effective and safe fibrinolytic enzymes have become the key to thrombosis treatment.

In this sense, studies have reported the promising antithrombotic effects of fibrinolytic agents from photosynthetic microorganisms such as

Chlorella vulgaris and

Arthrospira platensis [

7,

8]. In addition, some bioactive such as lectin, linoleic acid, and flavonoids extracted from microalgae

Tetradesmus obliquus showed anticancer and antimicrobial activities [

9,

10,

11]; however, there is no report on the fibrinolytic potential of this genus.

The production of microalgae has tripled in the last 5 years and it has attracted interest in research and industrial fields worldwide due to some characteristics such as high photosynthetic efficiency, fast growth rate, resistance to various contaminants, capacity to grow on non-arable lands, and be cultured using different metabolic pathways (autotrophic, heterotrophic, and mixotrophic growth modes) [

12,

13,

14]. Specifically, previous studies have been shown that mixotrophic conditions using different organic carbon substrates provide higher production of enzymes and increase biomass yields from

T. obliquus [

15,

16].

Organic wastes and by-products are frequently used as substrates for mixotrophic growth and are advantageous for sustainable resource recycling and cost reduction of microalgal production [

17]. Corn steep liquor (CSL) is a by-product from the corn wet milling industries and has high amounts of carbohydrates, amino acids, vitamins, organic acids and minerals, being a nitrogen-rich source used for microalgal cultivation [

18]. By the way, this by-product has been successful to production of fibrinolytic enzymes from

C. vulgaris and

A. platensis [

7,

8]; but not yet on

T. obliquus cultivation. So, this study aims to evaluate and compare the biomass and fibrinolytic enzymes productions from

Tetradesmus obliquus cultivated under autotrophic and mixotrophic (using CSL) growth conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Culture media and growth conditions

Tetradesmus obliquus (SISGEN A5F5402) was isolated from Açude of Apipucos (Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil, coordinates 8°1′13.08″ S; 34°55′56.51″ W) and cultivated under autotrophic condition in 1000 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 400 mL of BG-11 medium [

19] with an initial concentration of 50 mg·L

−1, temperature of 30 ± 1 °C, continuous light intensity of 40 μmol photons m

-2·s

−1, under constant aeration [

20]. Mixotrophic condition was defined by the addition of different concentrations of corn steep liquor (0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1.00, 2.00, and 4.00% (v/v) into BG-11 medium. CSL (Corn Products Brazil, Cabo de Santo Agostinho, PE, Brazil) was previously treated according to Liggett and Koffler [

21].

Cell growth was measured daily until to reach the end of the exponential growth phase. Cell biomass was harvested by centrifugation (5,000 rpm for 5 min), washed three times with distilled water, freeze-dried and stored at 4 °C.

Biomass concentration was determined by measuring the optical density (OD) at λ665 nm by a UV/Visible spectrophotometer using an appropriate calibration curve correlating OD665 to biomass concentration (Equation 1, R

2 = 0.99).

2.2. Kinetic parameters

Biomass productivity (P

x) at the end of cultivation was calculated by Equation 2:

where

Xt is the final cell concentration (mg·L

−1),

X0 the initial cell concentration (mg·L

−1) and

tc time in culture final cell concentration (days).

Maximum specific growth rate (

μmax), expressed in day

−1, was calculated by the following equation:

where

Xj and

Xj−1 are cell concentrations at the end and the beginning of each time interval (Δ

t = 1 day).

2.3. Fibrinolytic enzyme extraction

Cell biomass (100 mg·mL−1) was resuspended in 0.02M Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.0 and submitted to two different extraction methods: (1) homogenization by constant stirring for 30 minutes in ice bath (MATSUBARA et al., 2000); (2) sonication using a sonicator (Bandelin Sonoplus HD 2070, Microtip MS 72, Germany) with 20 pulses for 1 minute with intervals of 1 min between each pulse on ice bath (ROMÁN et al., 2022). Both cell extract was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4 °C and the supernatant used to further analysis.

2.4. Precipitation methods

Cell extract was precipitated using two different solvents: (1) acetone (80%) was added to the cell extract slowly at 4 °C. The precipitated was collected by centrifugation (8,000 rpm for 10 min), after which the pellet was freeze-dried, and stored; (2) ammonium sulfate was added to the cell extract with gentle stirring at 4 °C until the solution was saturated at concentration of 0–40% and 40–70% (w/v). Then, the protein precipitated by centrifugation (8,000 rpm for 10 min) was dissolved in 0.02M Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.4 and dialyzed against the same buffer for 6 h at 25 °C. After dialysis, protease and fibrinolytic activities, and protein content were determined.

2.5. Protein purification

Fibrinolytic enzyme was purified through two-step chromatography using ion exchange and gel filtration. Protein redissolved was loaded on to ion-exchange chromatography using DEAE Sephadex column (1.6 × 50 cm) pre-equilibrated with 0.02M Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.4 at a flow rate of 1 mL·min−1, and the absorbance measured at λ280 nm. Fractions showing fibrinolytic activity were pooled and concentrated. Weight determination was achieved using Gel Filtration Markers Kit for protein molecular weights 6,500-66,000 Da from Sigma-Aldrich.

2.6. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was carried out using a 12% polyacrylamide gel as described by Laemmli [

22]. The molecular weight was calibrated using Gel Filtration Markers Kit (6,500-66,000 Da, Sigma-Aldrich). Protein bands were detected by staining with silver.

2.7. Protein concentration analysis

Protein concentration was obtained using the BCA Protein Assay Reagent Kit (BCATM Protein Assay Kit, Thermo SCIENTIFIC). Bovine serum albumin was used as standard.

2.8. Protease activity assay

Protease activity was assayed using azocasein as a substrate. The reaction mixture contained 30 µL of 0.08 mM azocasein, 140 µL of 0.02M Tris-HCl pH 7.4, and 30 µL of the cell-free extract. After 15 min, the reaction was stopped and the absorbance was measured at λ450 nm using a microplate reader. One unit of azocasein activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to increase the absorbance by 0.001 per minute, and the protease activity was expressed as activity units [

23].

2.9. Determination of fibrinolytic enzyme

2.9.1. Fibrinolytic plate assay

Fibrinolytic activity of the cell extracts was determined on a fibrin plate [

24] with adaptations. Typically, the fibrin plate was prepared by mixing 0.45 bovine fibrinogen and 0.02M Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.4 with 2% agarose dissolved in 0.02 M Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.4 and 200 μL of CaCl

2. The prepared solution was poured into a Petri plate (90 × 15 mm) containing 200 µL of a thrombin suspension. The fibrinolytic activity of the cell extracts was obtained by creating wells of 5 mm, which were impregnated with 20 µL of

T. obliquus extracts and incubated at 37 °C for 20 h. The zone of clearance was defined as the fibrinolytic activity of cell extracts.

2.9.2. Fibrinolytic assay using spectrophotometry

The fibrinolytic activity was evaluated according spectrophotometric method described by Wang [

25]. A solution of fibrinogen (0.72%) and 0.02 M Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.4 was placed in a test tube and incubated at 37 °C for 5 minutes. After addition of thrombin (20 U·mL

−1) solution, the resulting mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 10 minutes, enzyme solution was added, and incubation continued at 37 °C. The solution was mixed after 20 and 40 minutes. At 60 minutes, reaction was stopped by adding 0.2 M trichloroacetic acid (TCA). Finally, the solution was centrifugated (8,000 rpm for 10 minutes) and the supernatant was measured at λ275 nm. One unit (U) of fibrinolytic activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to increase 0.01 units of absorbance per minute.

2.10. Determination of fibrinolytic enzyme

All the experiments were in duplicates and data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The statistical analyses were performed using the t-test and all results are expressed as average error bars showing SD. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Cell growth profile and kinetic parameters of T. obliquus cultivation under different growth conditions

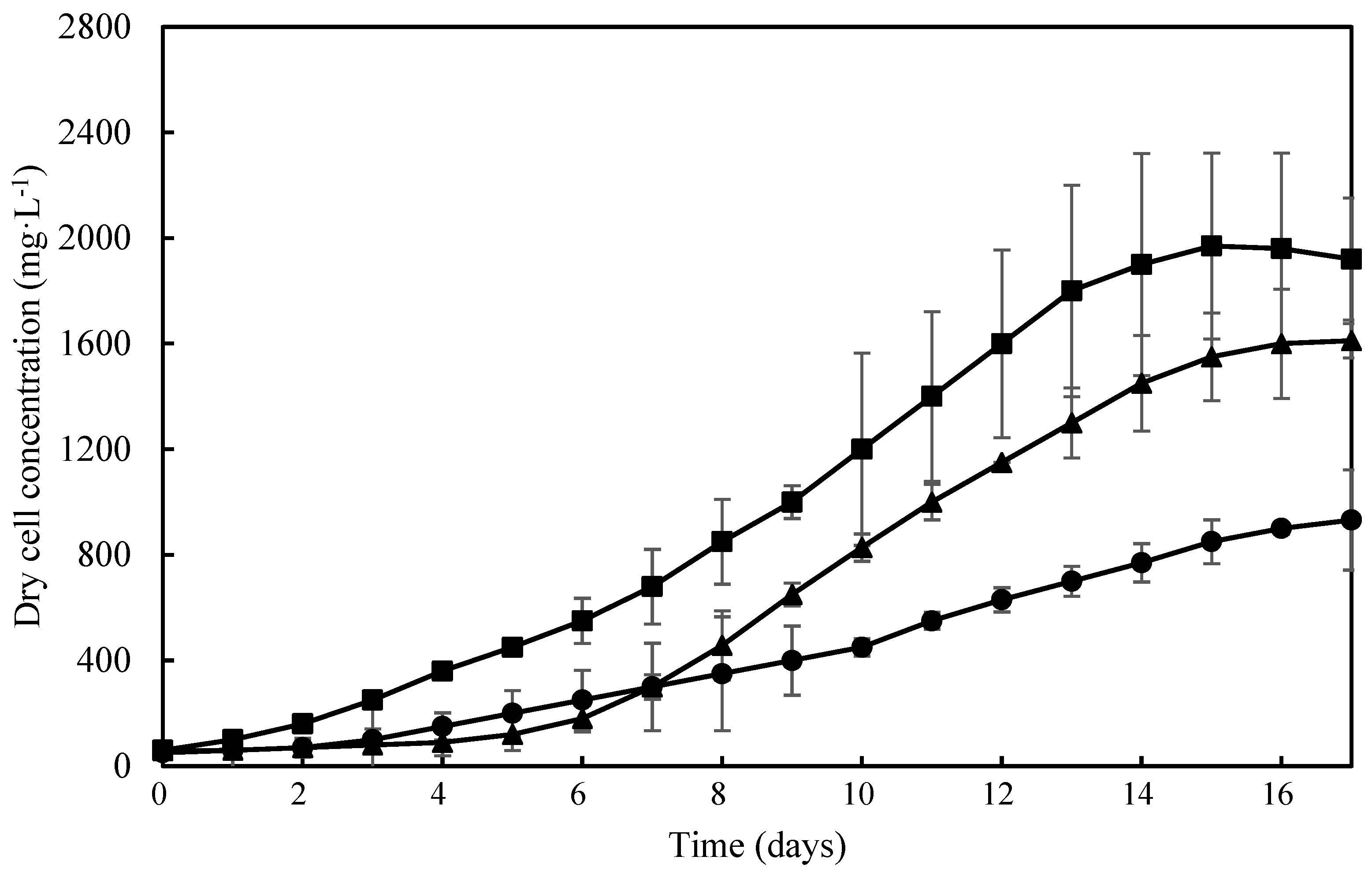

Cell growth profiles of

T. obliquus in autotrophic and mixotrophic growth conditions using different CSL concentrations are shown in

Figure 1. No lag phase and exponential phase of 16 days was observed in autotrophic growth (

Figure 1), showing the highest X

m values (1970 ± 231mg·L

−1), which can be explained by previously adaptation of

T. obliquus cells in medium culture constituted by inorganic nitrogen sources such as NaNO

3 and (NH

4)

5[Fe(C

6H

4O

7)

2]. On the other hand, in mixotrophic cultivation using 0.25% CSL, the exponential growth phase started after 8 days of cultivation obtaining a X

m of 1611 ± 206 mg·L

−1. Increasing CSL concentration to 0.50%,

T. obliquus showed a short two-days lag phase and started the exponential phase on the third day of cultivation (

Figure 1), reaching the lowest value of maximum cell concentration (X

m = of 932.68 ± 82.78 mg·L

−1) on the fifteenth day. This shows that concentrations of CSL higher than 0.50% inhibited

T. obliquus cells growth. This was also observed in the mixotrophic cultivation of

Arthrospira platensis using CSL concentration above 0.6% which inhibited cell growth [

8].

CSL concentration also influenced the cell growth kinetic parameters. As shown in

Table 1, the mixotrophic culture using 0.25% CSL showed significantly higher values of biomass productivity (P

x = 169.3 ± 44.36 mg·L

−1day

−1) and specific growth rate (µ

max = 0.17 ± 0.00 day

−1) than mixotrophic culture using 0.50% CSL (P

x = 95.72 ± 10.63 mg·L

−1day

−1; µ

max = 0.12 ± 0.00 day

−1). These results show that the high CSL concentration (>0.50%) in mixotrophic cultivation of

T. obliquus decrease P

x and µ

max values probably due to a stress provoked by the excess of nitrogen [

26,

27]. CSL is rich in protein content (420 mg·g

−1) and the mains amino acids available are arginine (44.30 mg·g

−1), alanine (35.70 mg·g

−1), and glutamic acid (42.00 mg·g

−1), showing that CSL is a potential organic N-source [

28,

29]. By the way, CSL has been considered as a low-cost material for the microbial production of enzymes [

17,

30,

31] and its effects on fibrinolytic enzymes production of

T. obliquus has not yet been studied. The highest biomass productivity (169.28 ± 44.36 mg·L

−1day

−1) was obtained in cultivation using 0.25% CSL which was selected for further steps.

3.2. Protease and fibrinolytic productions

The choice of growth condition has an important influence on the production of microbial enzymes. As shown in

Table 1,

T. obliquus produced a high amount of protease enzyme when cultivated on mixotrophic condition using 0.25% CSL (84.75 U·mg

−1), followed by autotrophic (12.48 U·mg

−1) and mixotrophic 0.50% CSL (5.85 U·mg

−1) conditions. Moreover, protease activity of

T. obliquus cultivated on 0.25% CSL is higher than those produced by different marine algae, such as

Ulva lactuca (6.55 – 7.33 U·mg

−1),

Ulva fasciata (8.00 U·mg

−1),

Enteromorpha sp. (6.74 – 9.60 U·mg

−1), and

Chaetomorpha antenna (9.40 U·mg

−1) [

32].

No significant difference in fibrinolytic activities was observed between autotrophic (430.46 ± 40.19 U·mg

−1) and 0.25% CSL (391.34 ± 40.03 U·mg

−1) cultivations, which were higher than 0.50% CSL (135.63 ± 6.98 U·mg

−1). In addition, fibrinolytic enzyme production from autotrophic and mixotrophic 0.25% CSL were higher than other photosynthetic microorganisms, including

Arthrospira platensis (268.14 ± 10.71 U·mg

−1) and

Chlorella vulgaris (302.29 ± 37.53 U·mg

−1) [

7,

8]. The results showed that protease and fibrinolytic enzymes productions were higher in cultures with lower CSL concentration. As well known, the biochemical composition of microalgae biomass, e.g., enzyme production, depends on the culture conditions such as the medium composition [

33]. Then, the highest enzymes activities were obtained using 0.25% CSL, which also enhanced enzyme production by

Arthrospira platensis [

8]. On the other hand, cultivation with higher CSL concentration (≥0.50%), decrease the enzymes productions, since high concentration of some nutrients, such as nitrogen, might affect the biomass composition [

34].

3.3. Effect of extraction methods on the enzymatic activities

Extraction methods influenced on enzyme activity. Homogenization and sonication extraction methods were evaluated to obtain protease and fibrinolytic extracts. Homogenization was the most efficient method to extract protease (12.48 ± 1.35 U·mg

−1) and fibrinolytic enzymes (430.46 ± 40.19 U·mg

−1) from autotrophic cultivation, while sonication methods decreased enzymes activities to 4.50 ± 0.42 and 149.44 ± 3.82 U·mg

−1, respectively (

Table 1). Similar results were observed in cell extracts from mixotrophic cultures using 0.25% CSL, which also showed higher protease (12.50 ± 2.94 U·mg

−1) and fibrinolytic (391.34 ± 40.03 U·mg

−1) activities using homogenization method when compared to sonication methods. This can be explained by possible enzyme denaturation caused by prolonged sonication time, high temperature, or elevated frequency as reported by Sukor et al., [

35] and Ranjha et al., [

36]. Then, these results showed that homogenization is more effective to extraction of protease and fibrinolytic enzyme from

T. obliquus.

3.4. Effect of precipitation methods on the enzymatic activities

T. obliquus extract rich protein was precipitated using acetone or ammonium sulfate in two fractions of saturation (0–40% and 40–70%). Both 0–40% and 40–70% ammonium sulfate fractions showed similar protease activity (614.06 ± 64.95 and 614.60 ± 13.65 U·mg

−1, respectively), which was higher compared to acetone precipitation (182.85 ± 7.03 U·mg

−1). Then, ammonium sulfate fractions are more advantageous for protease activity applications. However, although the 40–70% ammonium sulfate fraction exhibited the highest fibrinolytic activity (569.52 ± 23.20 U·mg

−1), the acetone fraction showed better performance due to its potential fibrinolytic activity (503.41 ± 22.35 U·mg

−1) and the highest enzyme yield of 32.98%. These results are similar to those reported by Barros et al., [

8], which precipitated a fibrinolytic enzyme from

Arthrospira platensis using acetone and showed fibrinolytic activity of 256.02 ± 23.45 U·mg

−1 and protein yield of 53.81%.

Taking into account that the fibrinolytic activity measures the enzyme capacity of degrading fibrin specifically, and the acetone fraction showed the highest recovery yield, this fraction was considered more advantageous to be studied for thrombosis therapy purposes. Acetone is listed among the Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) by Food and Drug Administration (FDA), since toxicological and medical studies show no adverse effects on human health [

37]. Additionally, use acetone for precipitation includes some advantages such as simple-step extraction, less cost, and less time-consuming [

38,

39]. Therefore, acetone was selected as the most advantageous precipitating agent to obtain fibrinolytic enzyme from

T. obliquus.

Table 2.

Comparation of different precipitating agents for precipitation of the homogenized cell extract from T. obliquus cultivated in 0.25% CSL.

Table 2.

Comparation of different precipitating agents for precipitation of the homogenized cell extract from T. obliquus cultivated in 0.25% CSL.

| Precipitating agents |

Total protease activity (U·mL−1) |

Yield (%) |

Specific protease activity (U·mg−1) |

P.F |

Total fibrinolytic activity (U·mL−1) |

Yield (%) |

Specific fibrinolytic activity (U·mg−1) |

P.F |

| Cell extract |

94.80 ± 20.78 |

100.00 |

175.74 ± 0.00 |

|

338.01 ± 34.78 |

100.00 |

391.34 ± 40.03 |

|

| Ammonium sulfate (0-40%) |

78.60 ± 8.31 a

|

82.91 |

614.06 ± 64.95 a

|

3.49 |

36.45 ± 2.96 a

|

10.78 |

569.52 ± 23.20 a

|

1.45 |

| Ammonium sulfate (40-70%) |

81.00 ± 1.80 a

|

85.44 |

614.60 ± 13.65 a

|

3.49 |

30.60 ± 0.06 b

|

9.05 |

464.37 ± 0.00 b

|

1.18 |

| Acetone |

81.00 ± 3.11 a

|

85.44 |

182.85 ± 7.03 b

|

1.04 |

111.50 ± 9.90 c

|

32.98 |

503.41 ± 22.35 b

|

1.28 |

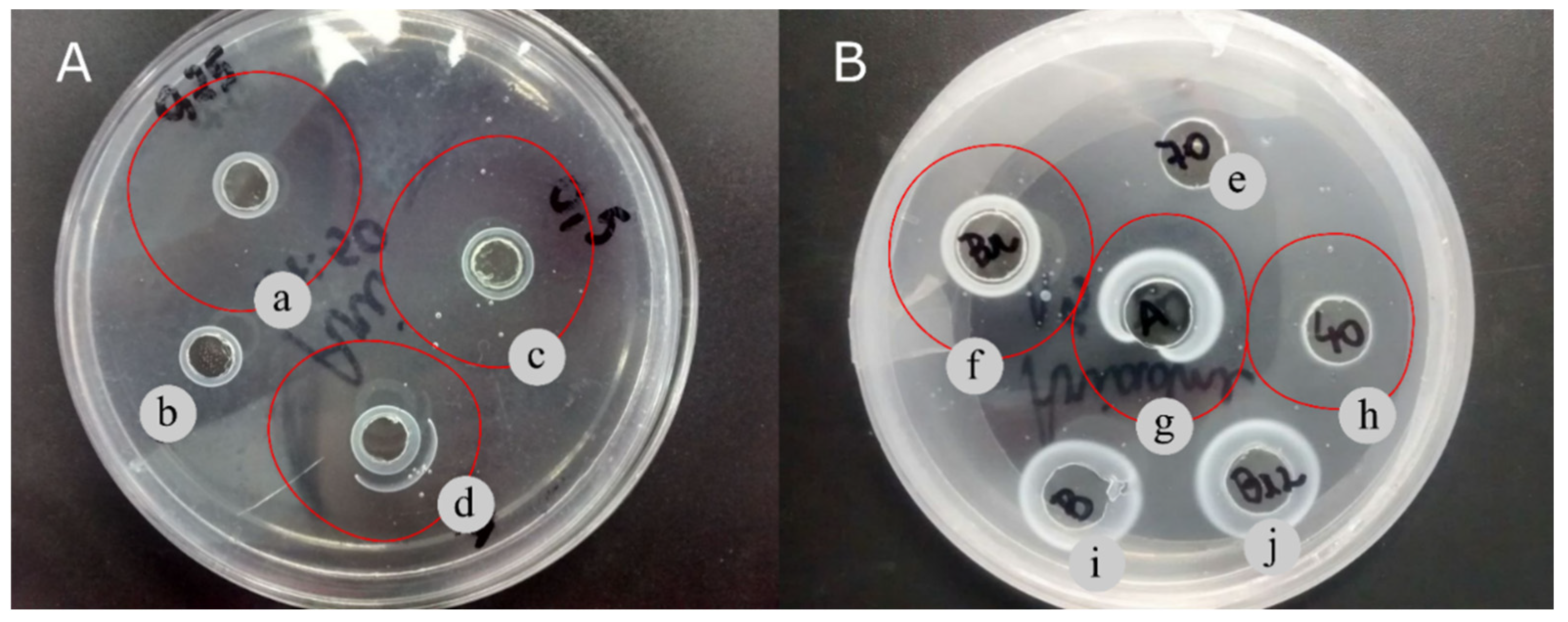

3.5. Fibrinolytic activity in fibrin plate

Figure 2 shows a qualitative assessment of the fibrinolytic activity from

T. obliquus by the fibrin plate method. The cell extract from

T. obliquus cultivated in 0.25% CSL showed a high clear zone (82 mm

2) when compared to cell extract obtained from cell cultivated autotrophically (69 mm

2) or mixotrophically with 0.50% CSL (69 mm

2) (

Table 3;

Figure 2A). These values are high than that of fibrinolytic enzymes from Bionectria sp. strains, which ranged from 21.9 to 66.7 mm

2 [

40].

Fibrinolytic activities of protein precipitated by different precipitating agents are shown in

Figure 2B. Both 0–40% ammonium sulfate and acetone fractions exhibited clear zone of fibrin degradation around the well after 48 h. On the other hand, 40–70% ammonium sulfate fraction did not show clear zone area of hydrolysis.

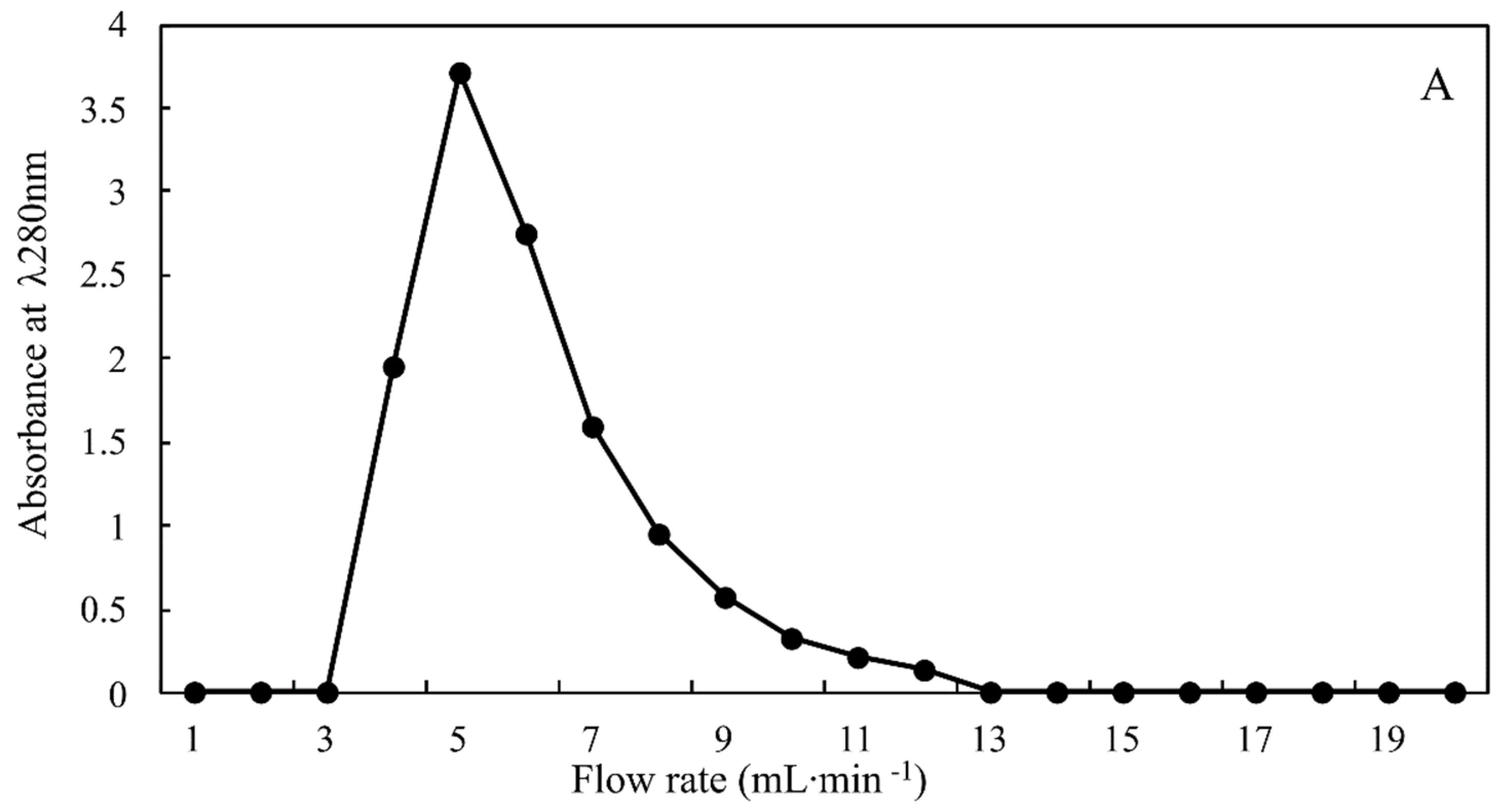

3.6. Enzyme purification

Fibrinolytic enzyme from

T. obliquus was purified using a combination of acetone precipitation and DEAE-sephadex ion exchange column. The chromatogram shown in

Figure 3 exhibit a single peak with fibrinolytic activity of 1176.90 ± 140.37 U·mg

−1, and after purification by DEAE-sephadex, the fibrinolytic enzyme was 3.00-fold purified with a yield of 67.45% relative to that of the cell extract (

Table 4). In general, the activity of the purified fibrinolytic enzyme from

T. obliquus was higher than those obtained from

Costaria costata (915.5 U·mg

−1),

Codium divaricatum (6.3 U·mg

−1),

Codium fragile (61.50 U·mg

−1), and

Ulva pertusa (295.18 U·mg

−1) algae and various bacterial species such as

Bacillus flexus (315.20 U·mg

−1),

Bacillus velezensis BS2 (131.15 U·mg

−1),

Bacillus subtilis HQS-3 (30.00 U·mg

−1), and

Bacillus subtilis ICTF-1 (280.00 U·mg

−1) [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

SDS-PAGE showed one protein band with the molecular mass of about 97 kDa (

Figure 4). This is higher than that exhibited by other

T. obliquus proteins reported by Silva et al., [

20] and Heide et al., [

46] that have a molecular weight of 78 and 12 kDa, respectively. Additionally, the molecular weight of fibrinolytic enzymes obtained from other microalgae species, including

Arthrospira platensis (72 kDa) and

Chlorella vulgaris (45 kDa) are also lower than the fibrinolytic enzyme from

T. obliquus [

7,

8]. These results show that this is a different protein from those reported previously.

5. Conclusions

In the present study was possible to produce and purify an enzyme from Tetradesmus obliquus microalgae with specific activity of 1176.90 ± 140.37 U·mg−1. Mixotrophic cultivation using an inexpensive and advantageous agro-industrial by-product (0.25% CSL) showed higher growth kinetic parameters and fibrinolytic production. Additionally, cell extraction by homogenization had highest fibrinolytic activity, while the protein precipitation with acetone exhibited the highest recovery yield. In general, these methods are considered as simple, efficient, less cost, less time-consuming, and recognized as safe for human health, which can facilitate this enzyme production as well as its purification. Therefore, these results can conclude that the fibrinolytic enzyme from T. obliquus has wide potential to industrial application besides its promising effects as an alternative for thrombolytic therapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T.V.S., P.E.C.S. and R.P.B.; methodology, A.T.V.S., P.E.C.S. and Y.A.S.M.; software, Y.A.S.M.; validation, R.P.B.; formal analysis, R.P.B., M.M.S., A.T.V.S. and Y.A.S.M.; investigation, A.T.V.S. and R.P.B.; resources, A.L.F.P.; data curation, Y.A.S.M., A.T.V.S. and R.P.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.A.S.M.; writing—review and editing, R.P.B.; visualization, Y.A.S.M., M.M.S. and R.P.B; supervision, R.P.B.; project administration, R.P.B. and A.L.F.P.; funding acquisition, A.L.F.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financed by Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - Brazil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001, by Foundation for Science and Technology of the State of Pernambuco (FACEPE, APQ-0252-5.07/14; APQ-1480-2.08/22) and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge to the Research Support Center (CENAPESQ, Recife, Brazil) and Laboratory of Technology of Bioactive (LABTECBIO, Recife, Brazil).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds).

- Zhao, L.; Lin, X.; Fu, J.; Zhang, J.; Tang, W.; He, Z. A Novel Bi-Functional Fibrinolytic Enzyme with Anticoagulant and Thrombolytic Activities from a Marine-Derived Fungus Aspergillus versicolor ZLH-1. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendelboe, A.M.; Raskob, G.E. Global Burden of Thrombosis. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metharom, P.; Berndt, M.C.; Baker, R.I.; Andrews, R.K. Current State and Novel Approaches of Antiplatelet Therapy. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015, 35, 1327–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, Q.; Singh, P.; Abid, M.; Jairajpuri, M.A. Limitations of conventional anticoagulant therapy and the promises of non-heparin based conformational activators of antithrombin. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2012, 34, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, H.; Yu, B.; Chen, G.; Liang, Z. Purification and Characterization of a Fibrinolytic Enzyme from Marine Bacillus velezensis Z01 and Assessment of Its Therapeutic Efficacy In Vivo. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- e Silva, P.E.D.C.; de Barros, R.C.; Albuquerque, W.W.C.; Brandão, R.M.P.; Bezerra, R.P.; Porto, A.L.F. In vitro thrombolytic activity of a purified fibrinolytic enzyme from Chlorella vulgaris. J. Chromatogr. B 2018, 1092, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barros, P.D.S.; e Silva, P.E.C.; Nascimento, T.P.; Costa, R.M.P.B.; Bezerra, R.P.; Porto, A.L.F. Fibrinolytic enzyme from Arthrospira platensis cultivated in medium culture supplemented with corn steep liquor. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 3446–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Júnior, J.N.; de Aguiar, E.M.; Mota, R.A.; Bezerra, R.P.; Porto, A.L.F.; Herculano, P.N.; Marques, D.D.A.V. Antimicrobial Activity of Photosynthetic Microorganisms Biomass Extract against Bacterial Isolates Causing Mastitis. J. Dairy Vet. Sci. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Marrez, D.A.; Naguib, M.M.; Sultan, Y.Y.; Higazy, A.M. Antimicrobial and anticancer activities of Scenedesmus obliquus metabolites. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, A.P.; Habibi, K.; Bijarpas, Z.K.; Tolami, H.F.; Alkinani, T.A.; Jameh, M.; Dehkaei, A.A.; Monhaser, S.K.; Daemi, H.B.; Mahmoudi, A.; et al. Cytotoxic Effect of a Novel GaFe2O4@Ag Nanocomposite Synthesized by Scenedesmus obliquus on Gastric Cancer Cell Line and Evaluation of BAX, Bcl-2 and CASP8 Genes Expression. J. Clust. Sci. 2023, 34, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.J.; Janssen, M.; Südfeld, C.; D’adamo, S.; Wijffels, R.H. Hypes, hopes, and the way forward for microalgal biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morillas-España, A.; Villaró, S.; Ciardi, M.; Acién, G.; Lafarga, T. Production of Scenedesmus almeriensis Using Pilot-Scale Raceway Reactors Located inside a Greenhouse. Phycology 2022, 2, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.; Cerqueira, K.; Rodrigues, J.; Silva, K.; Coelho, D.; Souza, R. Cultivation of Microalgae Chlorella vulgaris in Open Reactor for Bioethanol Production. Phycology 2023, 3, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentahar, J.; Doyen, A.; Beaulieu, L.; Deschênes, J.-S. Investigation of β-galactosidase production by microalga Tetradesmus obliquus in determined growth conditions. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasecka, A.; Nawrocka, A.; Wiącek, D.; Krzemińska, I. Agro-industrial by-product in photoheterotrophic and mixotrophic culture of Tetradesmus obliquus: Production of ω3 and ω6 essential fatty acids with biotechnological importance. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Lim, D.; Lee, D.; Yu, J.; Lee, T. Valorization of corn steep liquor for efficient paramylon production using Euglena gracilis: The impact of precultivation and light-dark cycle. Algal Res. 2022, 61, 102587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiani, M.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Farhangi, A.; Mehrabi, M.R. Production of Desferrioxamine B (Desferal) using Corn Steep Liquor in Streptomyces pilosus. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2010, 13, 1151–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.M.; Stanier, R.Y. Growth and division of some unicellular blue-greenalgae. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1968, 51, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.J.; Cavalcanti, V.L.R.; Porto, A.L.F.; Gama, W.A.; Brandão-Costa, R.M.P.; Bezerra, R.P. The green microalgae Tetradesmus obliquus (Scenedesmus acutus) as lectin source in the recognition of ABO blood type: purification and characterization. J. Appl. Phycol. 2020, 32, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liggett, R.W.; Koffler, H. Corn steep liquor in microbiology. Bacteriol. Rev. 1948, 12, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of Structural Proteins during the Assembly of the Head of Bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Alencar, R.B.; Biondi, M.M.; Paiva, P.M.G.; Vieira, V.L.A.; Carvalho, L.B.; Bezerra, R.S. Alkaline proteases from digestive tract of four tropical fishes. Environ. Sci. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Astrup, T.; Müllertz, S. The fibrin plate method for estimating fibrinolytic activity. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1952, 40, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.-L.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Liang, T.-W. Purification and biochemical characterization of a nattokinase by conversion of shrimp shell with Bacillus subtilis TKU007. New Biotechnol. 2011, 28, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad Mirzaie, M.A.; Kalbasi, M.; Mousavi, S.M.; Ghobadian, B. Statistical evaluation and modeling of cheap substrate-based cultivation medium of Chlorella vulgaris to enhance microalgae lipid as new potential feedstock for biolubricant. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2016, 46, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbib, Z.; Ruiz, J.; Álvarez-Díaz, P.; Garrido-Pérez, C.; Barragan, J.; Perales, J.A. PHOTOBIOTREATMENT: INFLUENCE OF NITROGEN AND PHOSPHORUS RATIO IN WASTEWATER ON GROWTH KINETICS OF SCENEDESMUS OBLIQUUS. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2013, 15, 774–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, A.; Hauer, S.; Kroll, P.; Fricke, J.; Herwig, C. In-depth characterization of the raw material corn steep liquor and its bioavailability in bioprocesses of Penicillium chrysogenum. Process. Biochem. 2018, 70, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi-Shotorkhoft, A.; Sharifi, A.; Mirmohammadi, D.; Baluch-Gharaei, H.; Rezaei, J. Effects of feeding different levels of corn steep liquor on the performance of fattening lambs. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2015, 100, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.-H.; Ko, D.-J.; Heo, S.-Y.; Lee, J.-J.; Kim, Y.-M.; Lee, B.-S.; Kim, M.-S.; Kim, C.-H.; Seo, J.-W.; Oh, B.-R. Regulation of lipid accumulation using nitrogen for microalgae lipid production in Schizochytrium sp. ABC101. Renew. Energy 2020, 153, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, D.; Lim, D.; Lim, S.; Park, S.; Kang, C.; Yu, J.; Lee, T. Paramylon production from heterotrophic cultivation of Euglena gracilis in two different industrial byproducts: Corn steep liquor and brewer’s spent grain. Algal Res. 2020, 47, 101826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.S.; Rebecca, L.J. Isolation and Characterization of Protease from Marine Algae. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2014, 27, 188–190. [Google Scholar]

- Niccolai, A.; Chini Zittelli, G.; Rodolfi, L.; Biondi, N.; Tredici, M.R. Microalgae of interest as food source: Biochemical composition and digestibility. Algal Res. 2019, 42, 101617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaakob, M.A.; Mohamed, R.M.S.R.; Al-Gheethi, A.; Aswathnarayana Gokare, R.; Ambati, R.R. Influence of Nitrogen and Phosphorus on Microalgal Growth, Biomass, Lipid, and Fatty Acid Production: An Overview. Cells 2021, 10, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukor, N.F.; Jusoh, R.; Kamarudin, N.S.; Abdul Halim, N.A.; Sulaiman, A.Z.; Abdullah, S.B. Synergistic effect of probe sonication and ionic liquid for extraction of phenolic acids from oak galls. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 62, 104876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjha, M.M.A.N.; Irfan, S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Shafique, B.; Kanwal, R.; Pateiro, M.; Arshad, R.N.; Wang, L.; Nayik, G.A.; Roobab, U.; et al. Sonication, a Potential Technique for Extraction of Phytoconstituents: A Systematic Review. Processes 2021, 9, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, A.; Rimauro, J.; Casella, P.; Cerbone, A.; Larocca, V.; Chianese, S.; Karatza, D.; Mehariya, S.; Ferraro, A.; Hristoforou, E.; et al. Extraction of astaxanthin from microalga Haematococcus pluvialis in red phase by using generally recognized as safe solvents and accelerated extraction. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 283, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickerson, J.L.; Doucette, A.A. Rapid and Quantitative Protein Precipitation for Proteome Analysis by Mass Spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 2035–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpia, A.; Mahatheeranont, S.; Lomthaisong, K.; Niamsup, H. Evaluation of Sample Preparation Methods from Rice Seeds and Seedlings Suitable for Two-Dimensional Gel Electrophoresis. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2015, 175, 1035–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa e Silva, P.E.; Bezerra, R.P.; Porto, A.L.F. An overview about fibrinolytic enzymes from microorganisms and algae: production and characterization. J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. 2016, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.-W.; Sapkota, K.; Choi, J.-H.; Kim, Y.-S.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.-J. Direct acting anti-thrombotic serine protease from brown seaweed Costaria costata. Process. Biochem. 2013, 48, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, K.; Hori, K.; Matsuura, Y.; Miyazawa, K. Purification and characterization of a fibrinolytic enzyme and identification of fibrinogen clotting enzyme in a marine green alga, Codium divaricatum. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B: Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2000, 125, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.-H.; Sapkota, K.; Park, S.-E.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.-J. Thrombolytic, anticoagulant and antiplatelet activities of codiase, a bi-functional fibrinolytic enzyme from Codium fragile. Biochimie 2013, 95, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.-R.; Choi, J.-H.; Kim, D.-W.; Park, S.-E.; Sapkota, K.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.-J. A bifunctional protease from green alga Ulva pertusa with anticoagulant properties: partial purification and characterization. J. Appl. Phycol. 2016, 28, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzkar, N.; Jahromi, S.T.; Vianello, F. Marine Microbial Fibrinolytic Enzymes: An Overview of Source, Production, Biochemical Properties and Thrombolytic Activity. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heide, H.; Kalisz, H.M.; Follmann, H. The oxygen evolving enhancer protein 1 (OEE) of photosystem II in green algae exhibits thioredoxin activity. J. Plant Physiol. 2004, 161, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).