1. Introduction

The life cycle management of drugs involves conduct of bioequivalence (BE) studies throughout various phases of drug development necessitated by unforeseen factors such as changes in formulation or manufacturing process. These BE studies offer the possibility of comparing clinical outcomes by ensuring the similarity of the essential data for products going through various phases of development. Since the initial publication of the bioequivalence regulation by FDA in 1977, bioequivalence standards have undergone substantial evolution, incorporating increasing levels of complexity in drug discovery. However, pharmacokinetic endpoint studies remain the most commonly employed approach due to their sensitivity and repeatability, in contrast to pharmacodynamics or clinical endpoint studies [

1]. The underlying assumption is that systemic exposure is directly linked to the therapeutic effect. When two pharmaceutically equivalent drug products (e.g., two formulations of the drug or two drug products) are demonstrated to be bioequivalent, it is inferred that their active ingredient(s) are absorbed at the same rate and extent, generating comparable safety and efficacy profiles when administered to patients under the specified conditions in the product labelling. Consequently, these two drug products are deemed

therapeutically equivalent and can be interchanged without restrictions [

2].

For locally acting gastrointestinal (GI) products, unlike other drugs, plasma concentration is downstream from the site of clinical effect, resulting in a disparity between the pharmacokinetic (PK) profile and effectiveness. After administration, the active drug ingredient would be released from the drug product, undergoes dissolution in the GI tract, and subsequently becomes available at the site of action for therapeutic purposes. The rate and extent of drug presentation at the site of action are governed by dissolution and the transit along GI tract rather than plasma concentration [

3]. In the case of such drugs, in vivo dissolution testing plays a critical role in identifying potential formulation difference between generic and reference products of GI locally acting drug products, assuming the formulation has no impact on the GIT itself. Whereas plasma concentration actually disconnects from the action site drug concentration. Any changes in intestinal microbiota, absorption rate and the expression level of intestinal transporters, intestinal metabolism, hepatic metabolism and plasma protein caused by inter-individual differences or patients’ disease state could bias the detected plasma concentration profiles and widen the gap between local GI concentration and in vivo PK profiles.

Considering the polarity between GI local concentration and systemic PK profile of GI products, developing physiologically relevant dissolution method and high cost of clinical end point BE studies pose significant challenges. In this context, physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models emerge as an ideal investigative tool for exploring the correlation between dissolution in GI tract and plasma concentration profiles. These in silico PBPK models can integrate existing knowledge of physiological parameters (and population distribution) and drug properties that influence oral drug absorption together, which allows theoretical investigation into the interplay between the system and the drug properties, shedding light on the main driving forces of drug absorption, transport and metabolism [

4]. Verified PBPK models are also capable of predicting potential pharmacokinetics difference between test and reference drugs in virtual populations and thus assess the BE risks by virtual bioequivalence simulations [

5].

In this study, the controlled-release (CR) formulation of budesonide, known as Entocort® EC, was utilized as an illustrative example to compare local and systemic PK profile in both healthy volunteers and CD patients. Oral budesonide serves as the first-line therapy for inducing remission in mild to moderate CD patients [

6]. It is a corticosteroid drug with high potency while experiencing limited systemic exposure due to extensive first-pass metabolism [

7]. The permeability of budesonide is high (BCS class II), and if the compound is dosed in the form of micronized solid, it could dissolve quickly and be absorbed mainly in the upper GI sections [

8]. The approved product Entocort

® EC is orange/white colored gelatin capsule containing 3 mg of budesonide in the form of small pellets. Each pellet consists of multiple layers, including an enteric coating on the exterior that initiates dissolution at a pH >5.5 after the budesonide pellets enter the duodenum, and under the coating an ethylcellulose polymer-budesonide layer which could control the rate of budesonide release. This multiple-unit formulation could combine the favorable pharmacological properties of budesonide (high potency and extensive first pass metabolism) with localized, time-dependent release targeting the ileum and ascending colon, the most common sites of inflammation in patients with Crohn’s disease.

Despite the extensive first-pass metabolism and low bioavailability of budesonide, it is feasible to accurately quantify its plasma concentration following the oral administration of Entocort® EC capsules. Abundant clinical data collected with different dosage of Entocort® EC capsule in healthy population and CD patients are available in papers. Besides, literature reports provided information on the dissolution profile of Entocort® EC at fed and fasted state biorelevant buffer for healthy volunteer and CD patients at different disease levels. These resources render Entocort® EC an ideal model drug/formulation for investigation in current study.

In this study, PBPK models were built for Entocort® EC in both healthy subjects and in Crohn’s disease populations. Local GI tract exposures in 8 segments from duodenum to colon and two layers (lumen and enterocyte) in each segment were simulated for virtual generic formulations and Entocort® EC. Local bioequivalence was calculated and compared with systemic bioequivalence. For each virtual simulation, correlation between f2 value, local bioequivalence and systematic bioequivalence was examined. Validity of f2 value to indicate local or systematic BE, or adequacy of systemic BE to demonstrate local BE was analysed for all virtual formulations. Suitability of incorporating healthy volunteers in BE studies for formulations used in treating GI tract diseases was investigated. Through current study, we simulated various scenarios representing actual BE studies, trying to formulate some guiding principles regarding the most appropriate methods for BE studies of drugs acting locally in GIT.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Workflow

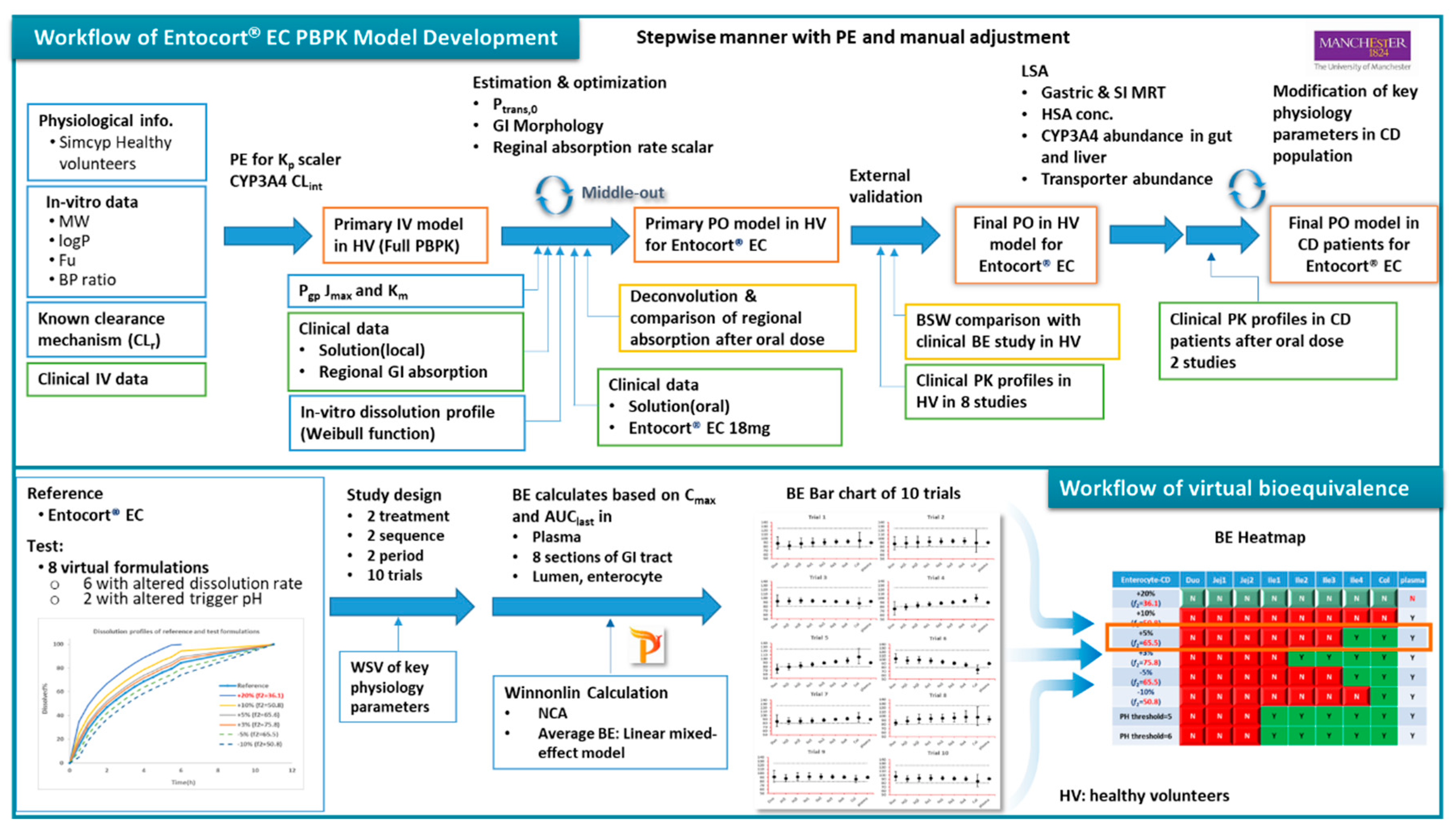

The workflow of the study is as depicted in

Figure 1. PPBK models for budesonide and Entocort

® EC were developed and validated against clinical PK data in HV and CD Patients. Then virtual bioequivalence studies were conducted with appropriate within subject variances so that the results are closer to actual situations. Based on BE results, bar charts for 10 trials were generated and analysed and BE heatmaps were depicted.

2.2. Software

The Simcyp PBPK Simulator (Version 22 Release 1; Certara UK Limited, Sheffield, UK) was used to build the model for Entocort® EC formulation in healthy subjects and Crohn's disease patients. VBE module embedded in the simulator was used in simulations of virtual bioequivalence between Entocort® EC and virtual generic formulations in eight sections of local GI tracts as well as plasma in both populations. Clinical plasma concentration-time data from the literature were digitized with Digit (version 1.0.4, Simulation Plus). Noncompartmental analysis and bioequivalence analysis were performed using Phoenix WinNonlin 8.3 (Certara L.P., Princeton, NJ, USA).

2.3. Data Package Used in Modelings

Physicochemical, in vitro ADME parameters and clinical PK data collected from health volunteers and CD patients are available from literature sources. Budesonide clinical PK profiles in 10 clinical trials conducted with injections, solutions (orally and GI locally dosed) and Entocort

® EC capsules in healthy subjects and in 2 studies conducted with Entocort

® EC in CD patients were collected and used in the model development and validation. The summary of basic subject demographics information of these clinical trials is presented in

Table 1. Since individual data were not provided in these papers, the mean concentrations from each trial were extracted instead. Clinical studies 1-4 were used in stepwise model building and parameter fitting. Others were used for external validation. For each simulation, the trial design was adapted to match the dose, age range, and proportion of females in the reported clinical study under pre-prandial state. The number of subjects in each trial was set as 100, following the default setting in Simcyp.

2.4. Model Development and Validation

2.4.1. Physicochemical data

Budesonide is a moderately lipophilic (logP

o/w 2.62) neutral small molecule compound. Physicochemical and binding data were collected from Effinger’s paper [

21]. The plasma protein binding was assigned to HSA and the K

D was calculated by Simcyp.

2.4.2. Distribution

Full PBPK model was selected as the PK model. The Rodgers and Rowland equations (Method 2) were used to calculate tissue specific Kp values and the volume of distribution. Kp scalar was adjusted manually to 1.065 so that predicted Kp values for all tissues could be scaled and the predicted Vss could resemble the reported volume of distribution in clinical PK study with IV dose, which is 2.69 L/kg [

9]. After incorporation of clearance, the fitted IV plasma concentration showed overestimation of exposure (underestimation of IV plasma concentration profile). Then the Kp scaler was adjusted to 0.8 to better fit the observed PK profiles.

2.4.3. Metabolism

Numerous studies have reported that budesonide undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism, primarily mediated by the enzyme CYP3A4. Besides, there is minor renal clearance involved in the elimination process. The renal clearance was calculated by the Equation 1, where fu was equal to 0.15, and the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of the population representative (a 24-year-old Caucasian male) 172.42 mL/min/1.73m

2, was used in the calculation. Consequently, the CL

R, typical renal clearance of budesonide for a 20–30-year-old healthy male was calculated to be 1.55 L/h. Biliary clearance and additional systemic clearance were set to be 0 since no biliary excretion or other elimination route was reported for budesonide.

Regarding to metabolic clearance, CYP3A4 was added to Enzyme Kinetics pane as the only metabolic pathway. Recombinant was selected as the source of kinetic data, and the intrinsic clearance (CLint) mediated by CYP3A4 was estimated by fitting the IV plasma concentration profile. A CLint of 4.1 μL/min/pmol of isoform was estimated by PE function.

2.4.4. Absorption

Multi-layer gut wall within ADAM (M-ADAM) model was used to simulate the absorption of Entocort® EC. The model parameters were adjusted to mimic the behavior of the time dependent release and absorption of the enteric-coated formulation along the intestinal tract.

Apical P

trans,0 was calculated by method 2 in Simcyp using Equation 2, where a = 2.36 × 10

-6 and b = 1.1. The estimated Apical P

trans,0 of budesonide was 1798.5 × 10

-6 cm/s.

Basolateral P

trans,0 was manually adjusted to 6000 × 10

-6 cm/s to cover first pass metabolism and AUC. P-gp CL

int,T (μL/min) was calculated by the software from J

max of 93 and K

m of 9.4, which were collected from literature [

22]. P

para was set as 0.05506 × 10

-6cm/s, which was the default value in the simulator.

In Simcyp, the gastrointestinal tract is divided into 8 sections, including one section for duodenum, two sections for jejunum, four sections for ileum and one section for colon. To better reflect reginal absorption along the GI tract, absorption rate scalars for colon, ileum and jejunum were adjusted in turn to recover PK profiles of locally dosed budesonide solutions. To simulate the administration to corresponding GI sections, ‘Fluid MRT’ and ‘Transit Time (Total%)’ were adjusted accordingly. In case of colon dosing, as the minimum transit time for small intestine in Simcyp is 0.5 hr, The 0.5 hr was added to the time axis of colon-dosed PK profile to compensate for the discrepancy in time course. The absorption scalar for duodenum was adjusted to recover the PK profile of orally dosed budesonide solution. As the formulation of locally dosed solution is ethanol/water (1:1), in which the ethanol could substantially increase the permeability [

23,

24], locally fitted absorption scalars across the whole GI tract were adjusted by a cofactor of 0.6 to offset the increase. The final set of absorption scalars used in the model for duodenum, jejunum, ileum and colon were 0.06, 0.12, 0.54 and 1.44, respectively.

- 2.

Formulation

Controlled/modified release-dispersible system was selected in Simcyp as the formulation type, which tracks the entity of fluid and dissolved drug and also the Pellets with activated Segregated transit time model (STTM) function. Stomach lag time and mean residence time (MRT) of pellet in stomach was set to 0hr and 0.8 h, respectively. MRT of pellet in SI was set to 3 hr based on previous clinical investigation on the movement of the particle [

12]. Retention time of fluid and dissolved drug was left as default values in the software.

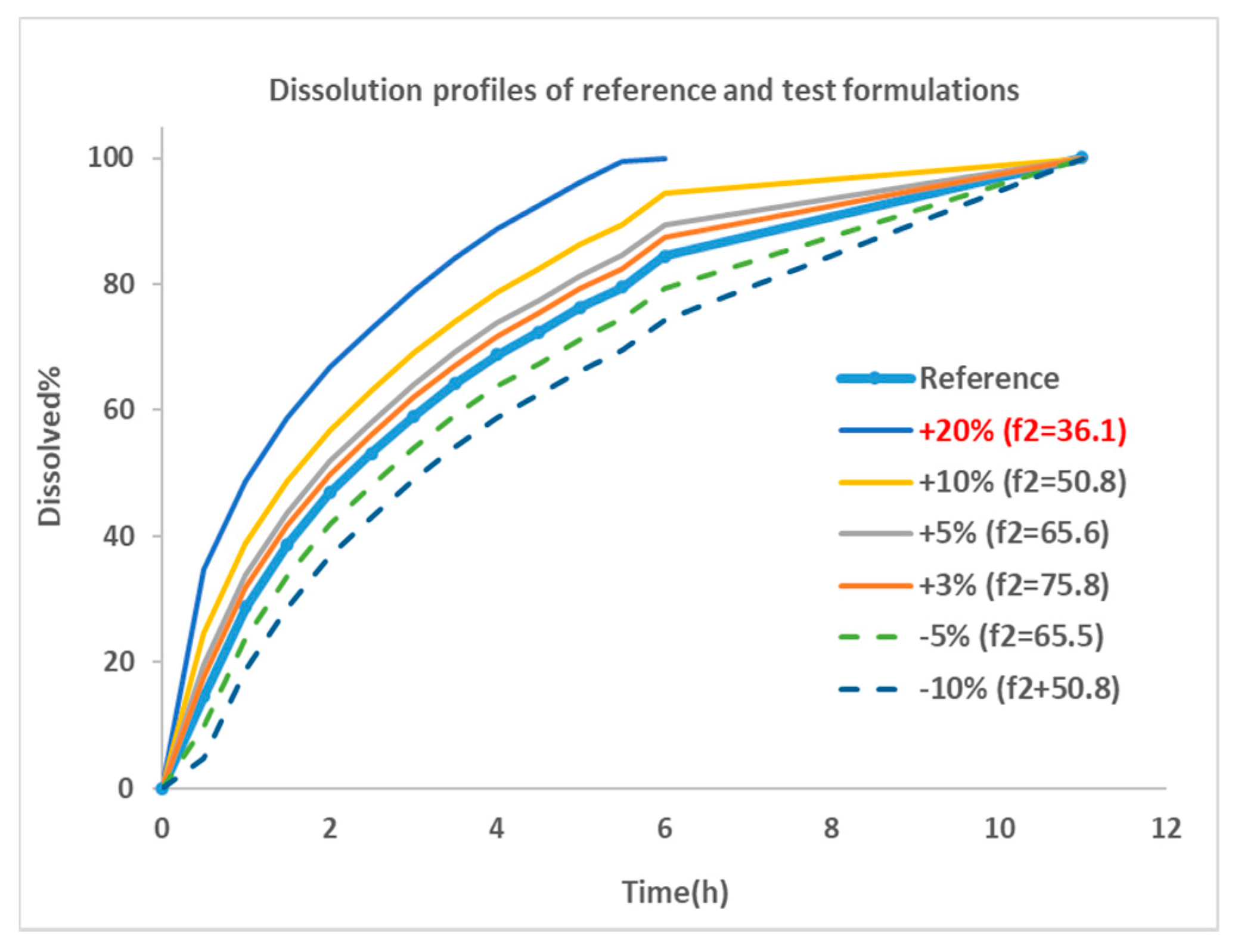

The dissolution profile for Entocort

® EC was collected from reference [

21] and utillized as the dissolution behavior of budesonide pellets. As the dissolution percentage in the experiment did not reach 100% at the last incubation time point, 100% dissolution was assumed at 12 hr. Then the dissolution profile of was modified manually by adjusting the % release or altering the trigger pH to generate dissolution profiles for 8 virtual formulations. These formulations were named by corresponding changes in dissolution profiles, i. e. ‘+5%’ is the formulations with trigger PH of 5.5 (the same as Entocort

® EC) and a 5% increase in the release% at every sampling time point; ‘PH threshold=5’ is the formulation with a modified trigger PH of 5 and an unchanged release profile compared with reference formulation Entocort

® EC. To facilitate subsequent

f2 calculation, the time for achieving 100% dissolution was standardized to 12 hr for all formulations except for the +20% formulation, of which 100% dissolution was reached at 7h. Dissolution profiles of reference and 6 virtual formulations modified by changing the %release are shown in

Figure 2.

Similarity factor (

f2) between the reference formulation and each virtual formulation were calculated using bootstrap method [

25]. The parameter is a logarithmic reciprocal square root transformation of the sum of squared error and is a measurement of the similarity in the percent (%) dissolution between the two curves as illustrated in Equation 3.

where n is the number of sampling time points, R

t is dissolution percentage of reference product at time point t, T

t is the dissolution of test product at time point t.

f2 values greater than 50 are indicative of the sameness or equivalence of the two dissolution curves and, thus, of the performance of the test and reference products [

26]. Based on the equation, a

f2 of 50 could be achieved by a formulation with 10% change at every time point of the dissolution profile compared with reference formulation. The smaller the change, the greater the

f2 value, until up to 100.

Then dissolution profiles for reference and 6 virtual formulations were fitted to Weibull function using Equation 3. Corresponding F

max, α and β for Entocort

® EC and virtual formulations were listed in

Table 2.

2.4.5. PBPK Model for Entocort® EC in Crohn’s Disease Patients

- 1.

Local sensitivity analysis (LSA)

As Crohn’s disease could lead to significant anatomical and physiological changes that might alter the pharmacokinetic property of drugs, LSA was conducted to assess the influence of changes in physiological parameters to PK profiles of Entocort

® EC, and to build CD patient population by modifying key parameters. The selection of parameters for sensitivity analysis was based on the property of budesonide and reported changes in CD patients, including mean retention time (MRT) in gut and small intestinal, CYP3A4 abundance in liver, small intestine (SI) and colon, HSA concentration, as well as transporter abundance. Ranges of these parameters were set to cover the range of both healthy subjects and CD patients. Details are listed in

Table 3. Oral C

max and AUC

last were selected as the analysis endpoints.

- 2.

Demographic parameters for healthy volunteers and Crohn’s disease patients

The default setting for healthy volunteers in Simcyp database was used in the PBPK model of Entocort

® EC in healthy subjects. CD population was built by changing key parameters identified in LSA. Values of these parameters in CD patients were collected from literature. The list of parameters and values are listed in

Table 4.

2.5. Virtual Bioequivalence (VBE)

The bioequivalence between Entocort

® EC and virtual formulations were simulated by VBE module of Simcyp software. The study design for all simulations was the typical design for BE study, i. e. two-sequence, two-treatment, two-period, crossover study. All simulations were performed with 10 trials with 12 subjects in each trial. Healthy subjects age from 20 to 50, with 50% of female. Virtual subjects were generated from demographic information by the simulator using Monte Carlo method. The default between-subject variability for HV population built in the software internal database was applied to each parameter. Within subject variances (WSV) for some parameters were included to better recover the actual variance as listed in

Table 5.

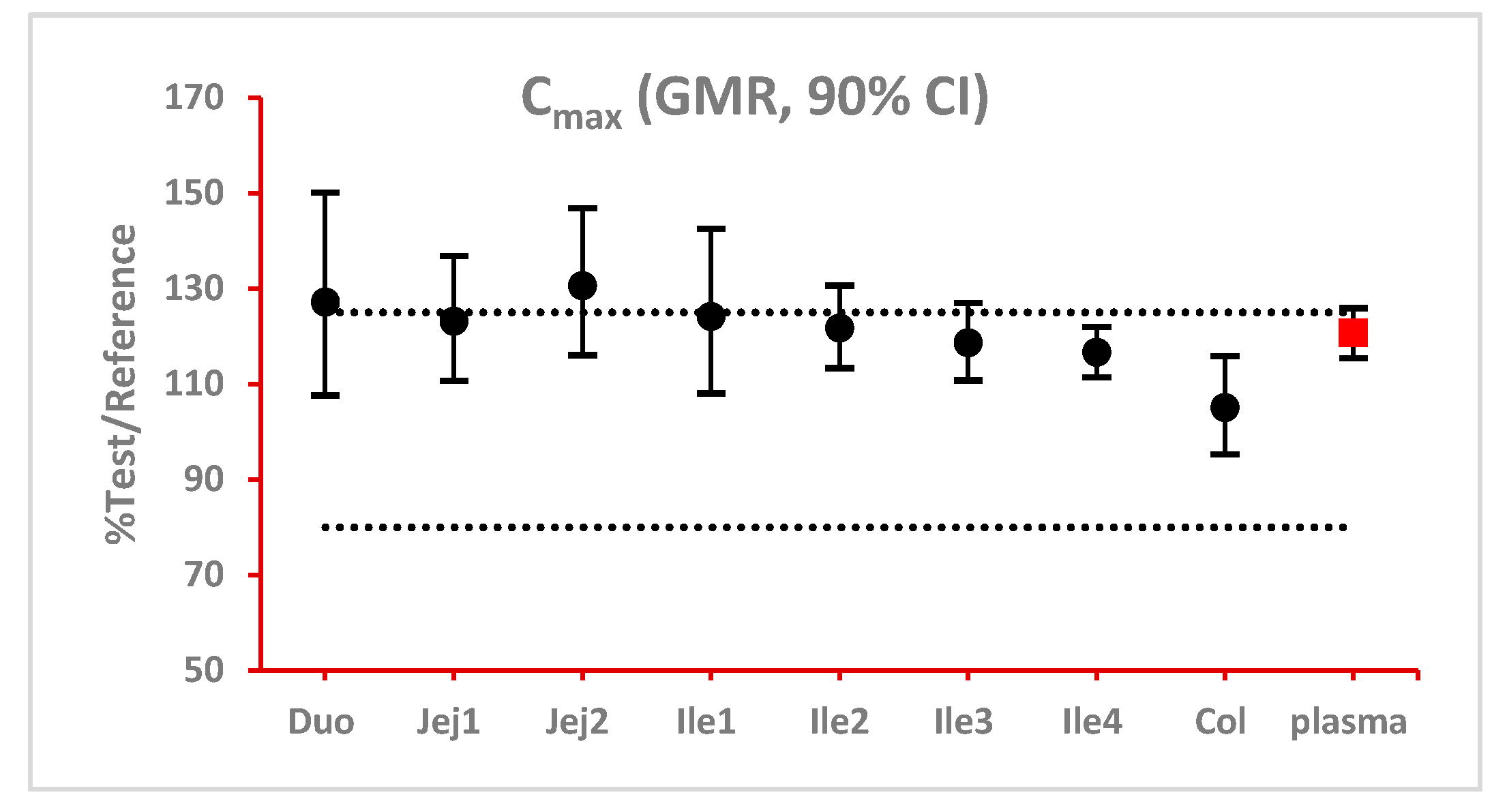

After simulation, concentration-time profiles in the system/plasma and two layers (lumen and enterocyte) of 8 sections of GI tract (duodenum, Jejunum 1 and 2, ileum 1-4, and colon) for each subject after each treatment were generated and exported to excel and then imported to WinNonlin for bioequivalence analysis. PK parameters (AUClast and Cmax) for each subject were calculated by noncompartmental analysis. Linear mixed-effect model was used to analyze the variance of log-transformed PK parameters between formulations. Sequence, treatment and period were selected as fixed effects, and subjects within sequence was regarded as random effect.

The 90% confidence interval (CI) of the ratio of geometric mean (test/reference) of PK parameters were calculated. Two formulations were considered bioequivalent if the 90% CI of the ratio of geometric means of C

max and AUC

last fall within the bioequivalence limits of 80% to 125%. BE bar charts were prepared based on BE results in enterocyte or lumen layer of 8 GI sections as well as plasma in one trial (

Figure 3).

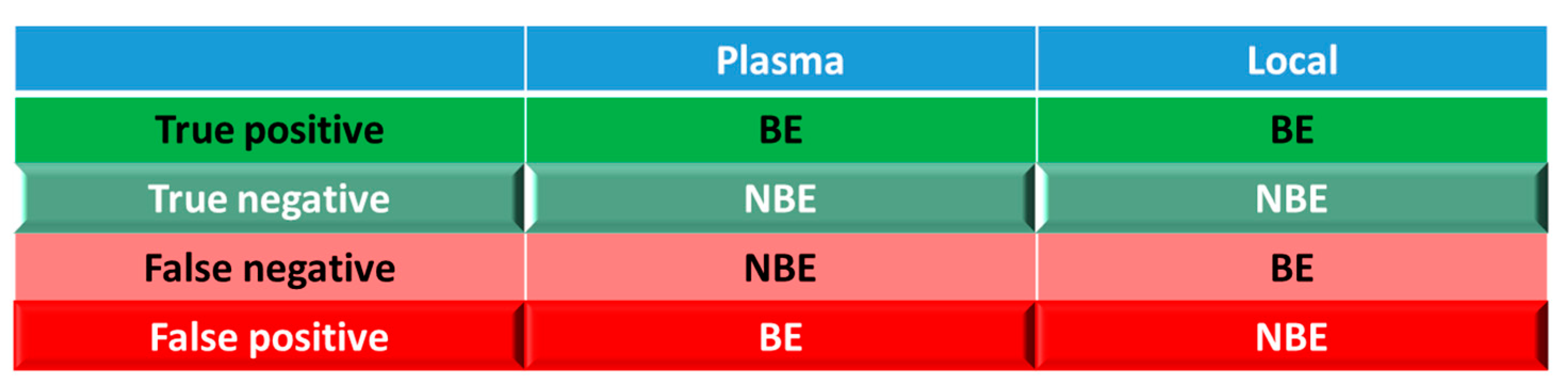

For simulations with 10 trials, if ≥ 8 trials show bioequivalence, the formulation was defined as bioequivalent to Entocort® EC. BE heatmaps were then generated based on bioequivalence or non-bioequivalence (NBE) results between 8 virtual formulations and Entocort® EC in plasma and local GI tract in 10 trials. If a formulation was BE with Entocort® EC in plasma, the result was defined as positive, or else, the result is negative. If the BE in certain GI segment was consistent with that in plasma, i.e. plasma BE could represent local BE result, then the result was defined as true and colored in green (true positive or true negative); or else, the result was considered false and colored in red and pink (false positive or false negative).

Figure 4.

Coloring and naming rule for the heatmap. Positive: bioequivalent; negative: not bioequivalent; true: local GI segment consistent with plasma, colored in green; negative: local GI in consistent with plasma, colored in red.

Figure 4.

Coloring and naming rule for the heatmap. Positive: bioequivalent; negative: not bioequivalent; true: local GI segment consistent with plasma, colored in green; negative: local GI in consistent with plasma, colored in red.

3. Results

3.1. PBPK models for Entocort® EC in healthy volunteers and CD patients

Detailed parameters for Entocort® EC PBPK model for healthy volunteers are summarized in

Table S1. Simulations for both healthy volunteers and CD patients met the criterion for internal (0.8- to 1.25-fold) and external validation (within 2-fold) (

Table 6), indicating the success of models in predicting the exposure of budesonide after administrations of solutions and the formulation. Regarding to the shape of the simulated concentration-time profile, as shown in

Figure S1, disposition and clearance of budesonide was successfully recovered by the PBPK model with IV bolus dose in healthy volunteers. Besides, the PK profiles of budesonide after local and oral administration of 2.6 mg (1 mL) solution, 3 mg (10 mL) solution and Entocort

® EC were well captured too (

Figures S2–S5, and S9). Details about local sensitivity analysis could be found in

Figures S7 and S8).

Regarding local absorption in the GI tract, ileo-colonic region accounts for approximately 70% of %absorption of budesonide and the simulated value (82.2%) has no significant difference from the reported value (76.1%) as shown in

Table S2. The fraction of absorption in each segment was simulated well except transverse and descending colon (reported: 6.9% vs simulated: 1.9%)

Simulated concentration-time profiles different sections and layers of GI tract were checked visually in

Figure S6 and simulated t

max and C

max were compared as listed in

Table 7. Plasma concentration reached C

max at 3 hr while upper small intestine reach C

max earlier, which is at 1-2 hr for duodenum and jejunum. The time for local GI tract to reach C

max is longer for distal intestinal sections. T

max for ileum and colon are 2-3 hr and 6 hr, respectively. The shape of the concentration-time profile (in semilog scale) in colon is quite similar to that in plasma. In contrast, the concentration profile of duodenum to ileum segments exhibited a completely different shape. It might be caused by the long retention time and thus prolonged absorption of the drug in colon. For the same section of gastrointestinal tract, concentrations in lumen and enterocyte showed a consistent trend of changes. Enterocyte concentrations are around 1% of the lumen concentrations in the same segment. In the meanwhile, concentrations in lumen and enterocytes are 2-5 orders of magnitude higher than the plasma concentration at the same sampling time point.

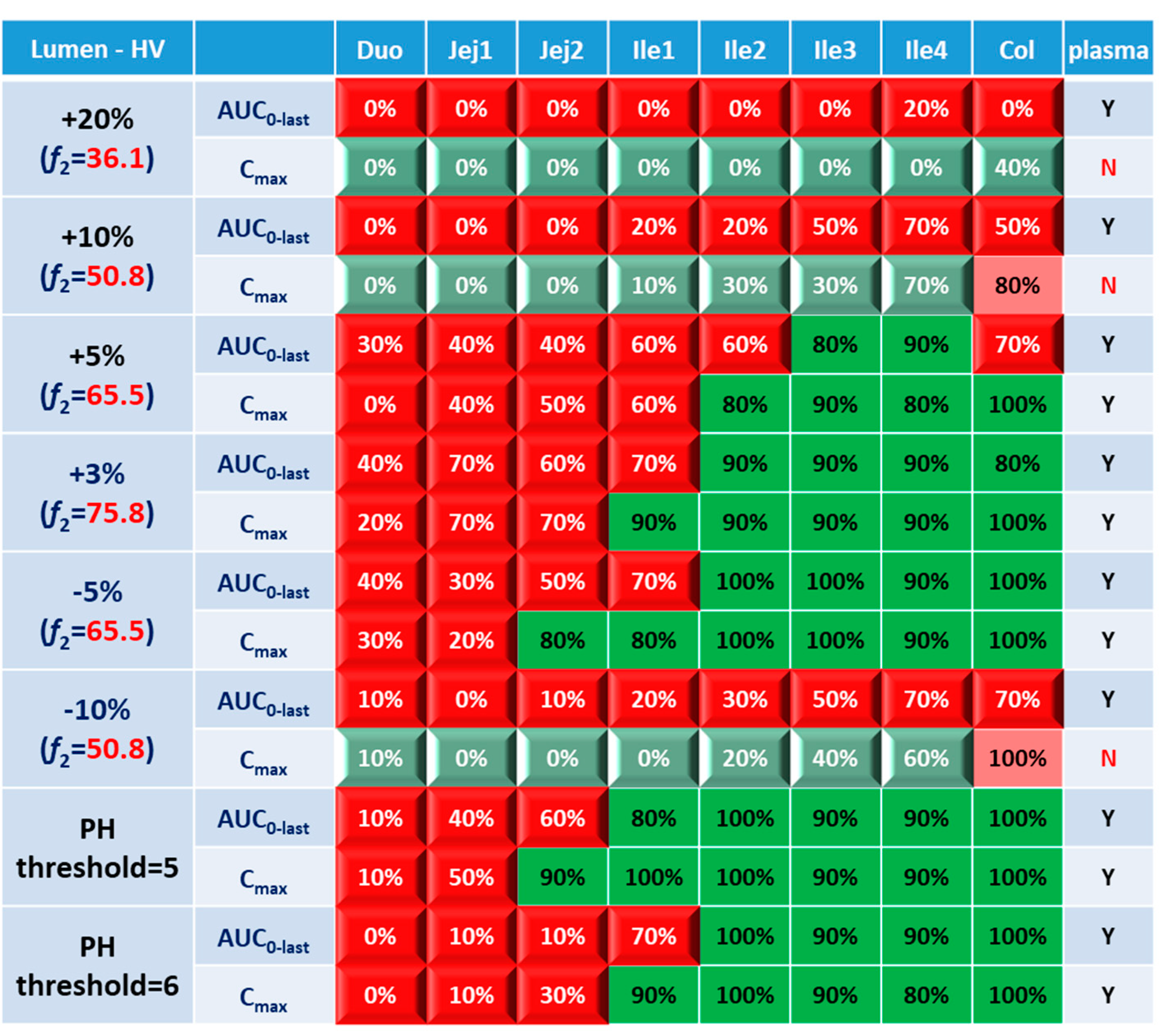

3.2. Virtual BE Heatmaps for Healthy Subjects

Systematic and local BE results were organized into heatmaps for further analysis. To facilitate classification and identification, heatmaps were modified based on local BE results. Local BE cells remained plat, while 3D bevel effects were added to local NBE cells. After modification, local BE could be identified by the 3D effects of cells. Flat green cells represent the most favorable scenario for drug discovery companies, i.e. BE in both plasma and local GI segments. Light green bevel cells depict situations that systemically and locally NBE. In both green cases, local BE could be expected through comparative PK studies. However, light green is less desirable since it may indicate the failure of the generic drug. Two red colors were used in the heatmap to represent unfavorable situations. Red bevel cells mean systematically BE, but locally NBE. In this case, substandard products could be released through PK based BE studies and that would be bad for patients. Flat pink cells represented the situation of systematic NBE while achieving BE in the corresponding GI segment, implying that one might lose generic drugs that could potentially work appropriately.

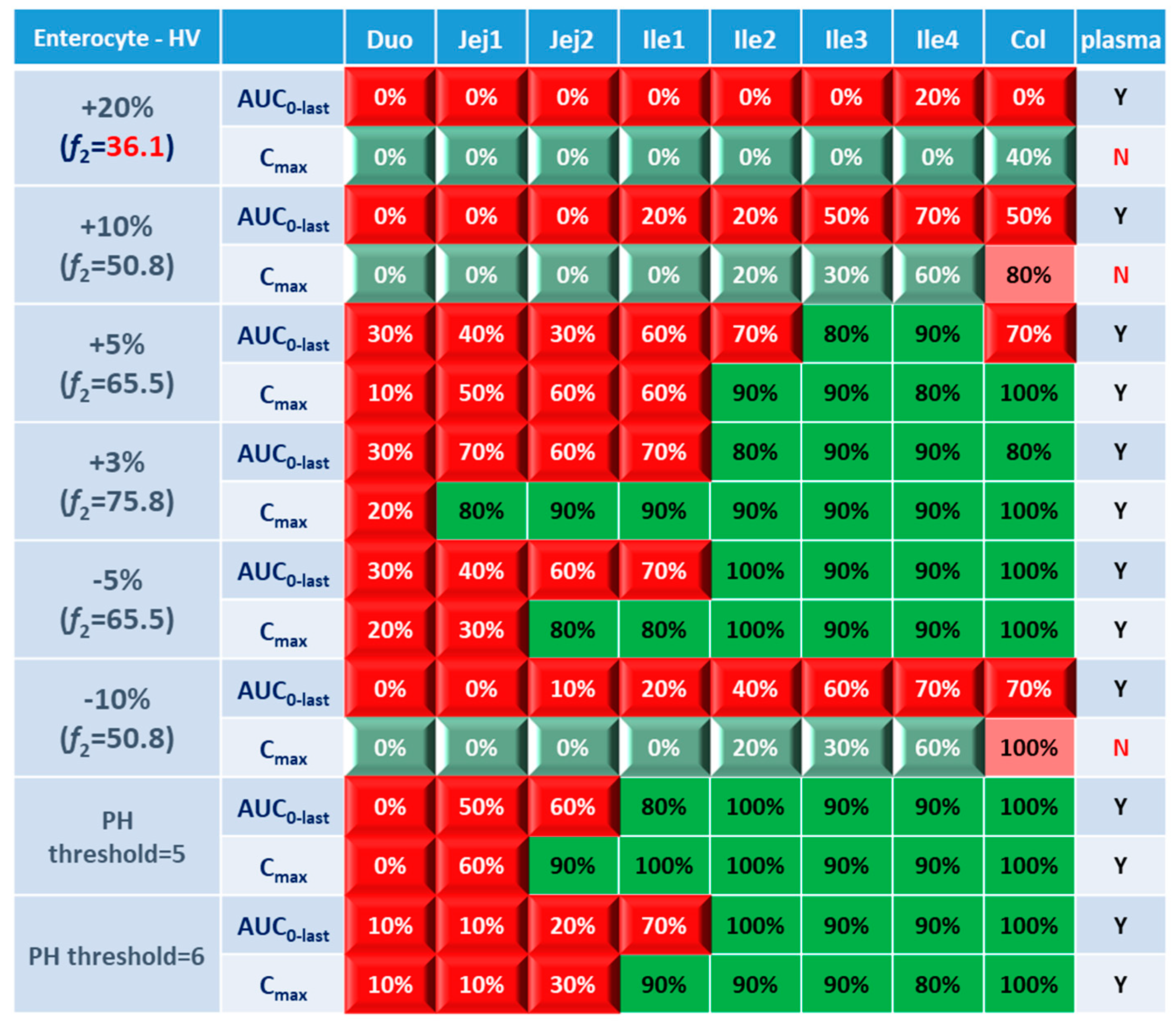

BE heatmap in enterocyte and plasma of healthy volunteer population is shown in

Figure 5. Regarding to the sensitivity of two parameters, i.e. AUC and C

max, the latter provided more negative results in plasma, whereas AUC identified more negative cases in local GI tracts. Regardless of the parameter used to identify NBE result, it is challenging to identify BE results in upper intestinal sections, including duodenum and jejunum. It suggests that these regions are sensitive to changes in the dissolution rate and trigger pH, which could be attributed to variations in the formulation manufacturing process.

In

Figure 5, BE results based on AUC

0-last and C

max were listed separately to compare the sensitivity of these two parameters. In plasma, all the test formulations were bioequivalent to reference formulation based on AUC

0-last while as 3 formulations (+20%, +10% and -10%) were identified to be not bioequivalent based on plasma C

max. It suggests that plasma AUC

0-last is less sensitive to formulation changes than plasma C

max. On the other hand, in the local GI tracts, AUC

0-last is more sensitive than C

max since the former identified more local NBE results. Due to the discrepancy in parameter sensitive, it is necessary to combine AUC

0-last and C

max together when checking about the discordance in local and systemic bioequivalence.

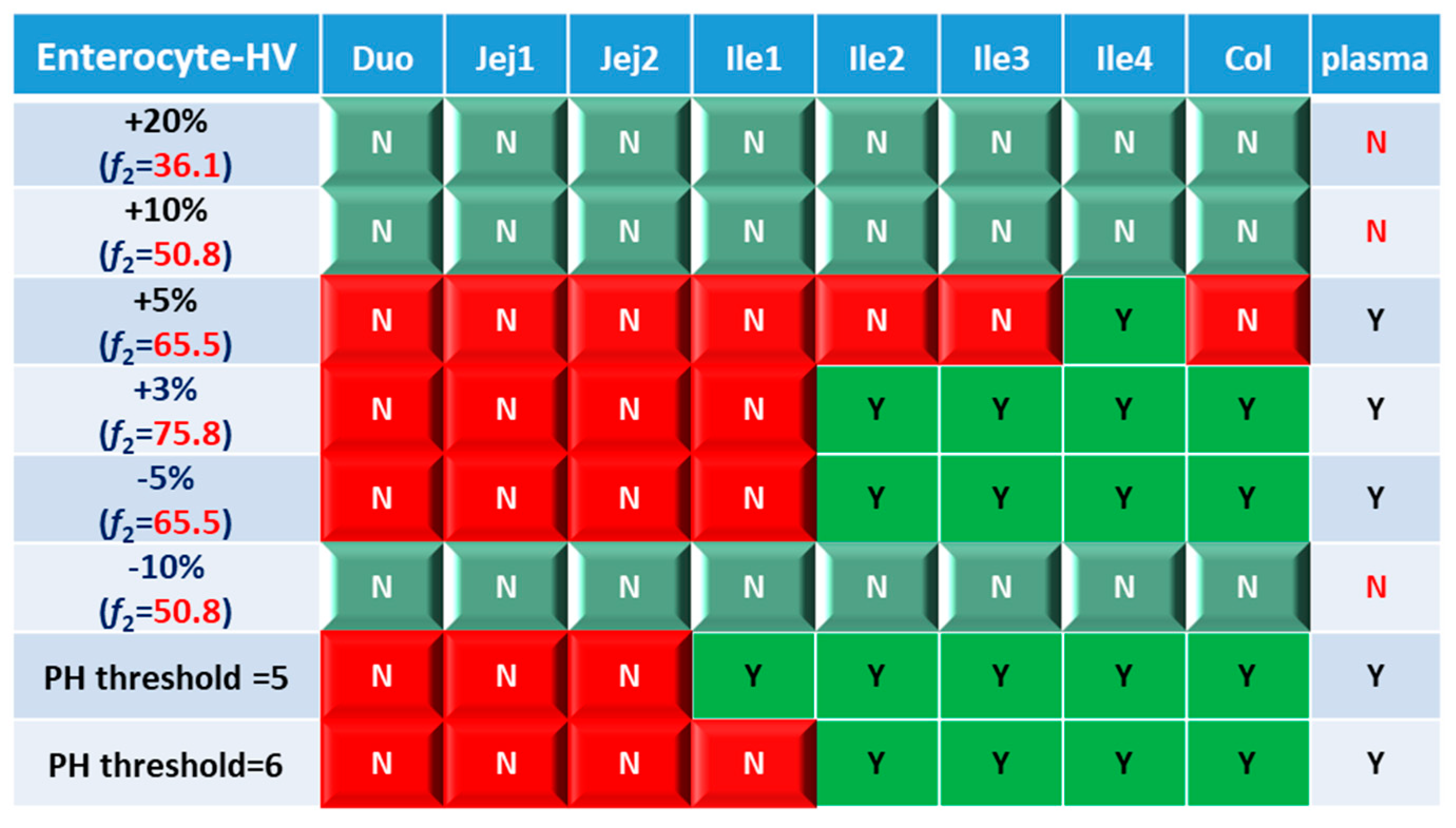

Based on combined BE results based on both AUC and C

max (

Figure 6), nearly all the formulations show NBE result based in upper intestines (duodenum and jejunum), which means upper intestine are very sensitive to formulation changes. Both ends of the GI tract (duodenum, jejunum, ileum 1 and colon) were observed to be sensitive to changes in the dissolution rate, and the ileum section tends to be conservative to formulation changes and showed more BE results than other sections. Based on simulation results of 8 formulations, in most cases plasma BE could represent the local GI BE in ileum 2-4 sections and colon, except for the +5% formulation, which was bioequivalent in plasma but not in ileum 2-3 and the colon.

Regarding the performance of similarity factor f2 in predicting plasma and local BE, the study suggested that the commonly used cutoff of 50 is insufficient to ensure either systemic BE or local GI BE. Bioequivalence of plasma BE could be achieved for formulations when f2 is increased to 65.5. Regarding bioequivalence in local GI sections, duodenum, jejunum and ileum 1 segments are so sensitive to formulation changes that all formulations in current study were found to be not bioequivalent in these sections. Regarding to the more conservative ileum 2-4 and colon sections, which are also the target sections for Entocort® EC, bioequivalence could be achieved when f2 reaches 65.5, i.e. the +3% formulation (f2=75.8) and -5% formulation (f2=65.5). But for another formulation with f2 of 65.5, i.e. the +5% formulation, local BE in ileum 2-3 and colon was not achieved. In summary, based on the BE heatmap, f2 of 50 is inadequate to ensure local or plasma bioequivalence in the case of the formulation Entercort® EC. Higher f2 values (>65.5) should be considered as quality control for GI locally acting products.

For two formulations with altered trigger pH, which could be achieved by altered coating material or thickness of coating, BE performance is generally comparable or even superior to that of formulations with high f2 values (65.5 or 73.8). NBE results were observed in upper sections (duodenum to ileum 1), whereas ileum 2-4 and colon were conservative to formulation changes. Increasing the trigger pH from 5.5 to 6.0 could potentially delay the release of the drug after administration, and thus lead to more significant change compared with the performance to formulation with trigger pH of 5.0.

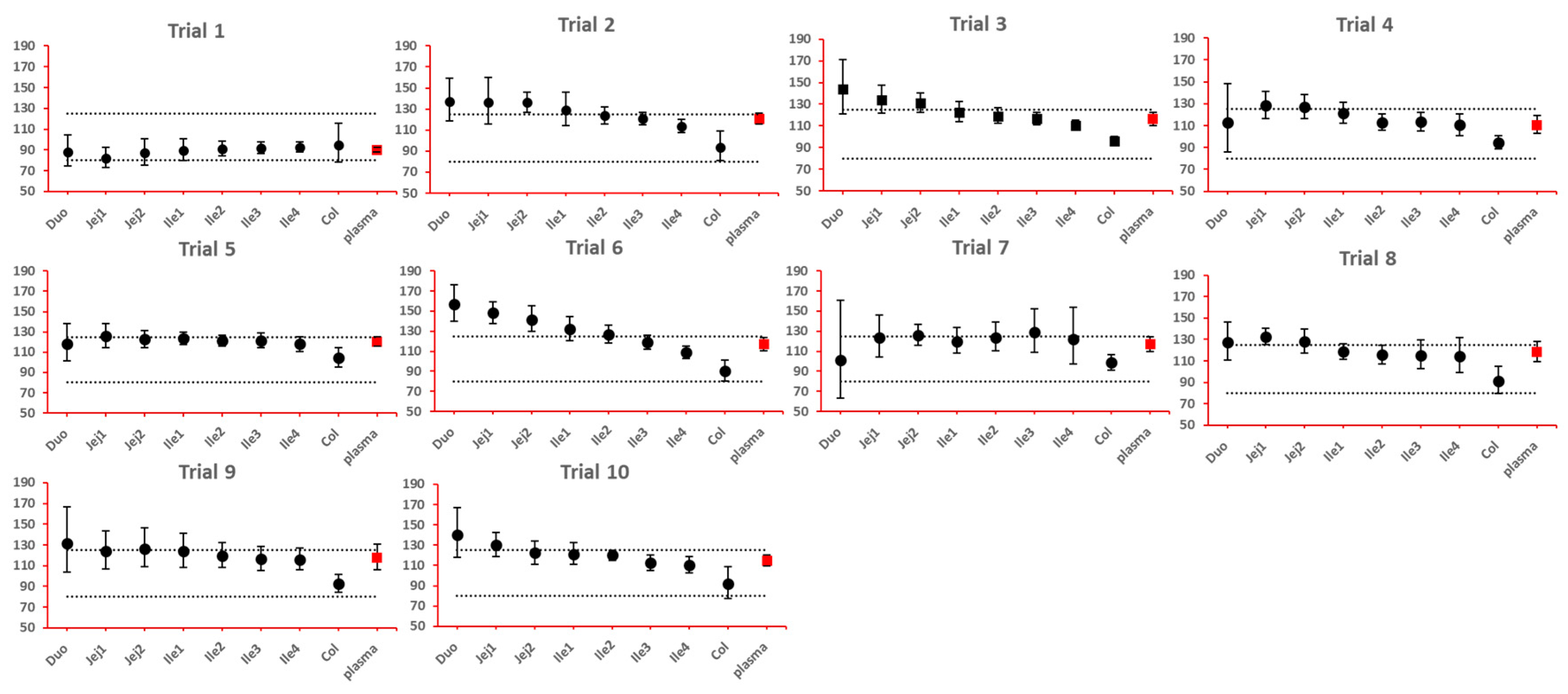

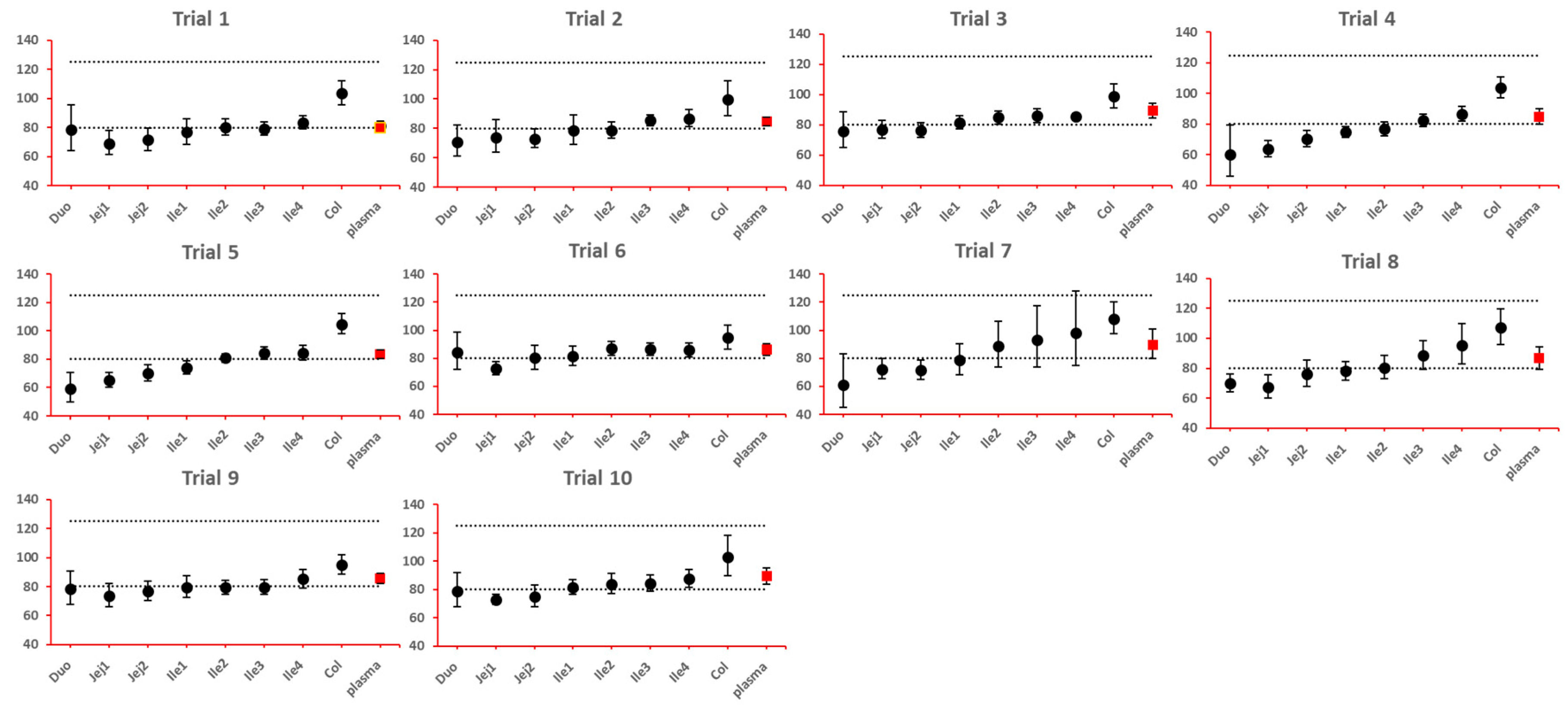

As NBE results could be attributed to the shift in the geometric mean, or wide confidence interval related to high interindividual variance, BE bar charts for two formulations with faster and slower dissolution rates were examined, respectively. As depicted in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, the range of 90% confidence interval in local GI tracts are wider than that in plasma, suggesting higher interindividual interval. However, the interval is not excessively wide to cause negative outcomes in bioequivalence analysis. Regarding the trend of concentration change, faster dissolution rate leads to higher concentration in the upper gastrointestinal tracts as well as in plasma in all trials; slower dissolution could lead to lower concentration in the upper gastrointestinal tract as well as in plasma. The concentration in colon tend to move in the opposite direction compared with plasma. The magnitude and direction of concentration change in ileum sections are generally the same as that in plasma, possibly accounting for synchronization between plasma BE and ileum local BE.

As lumen concentration is important to other GI locally action drugs treating Crohn's disease, like metronidazole and ciprofloxacin, etc, BE results based on lumen concentrations and PK parameters were also examined for 8 formulations and were compared with BE results simulated in plasma. As shown in

Figure 9, comparison between lumen heatmap and enterocyte heatmap didn’t uncover any significant difference, especially when one considers the sensitive parameter C

max. Similar phenomenon concerning discrepancy between local and systemic BE and the discrimination effect of

f2 could be observed. Although the concentrations in lumen layer is around 100 folds of the enterocyte concentration in same GI section (Table 8), they generally respond to the formulation modifications in the same manner and to the same extent.

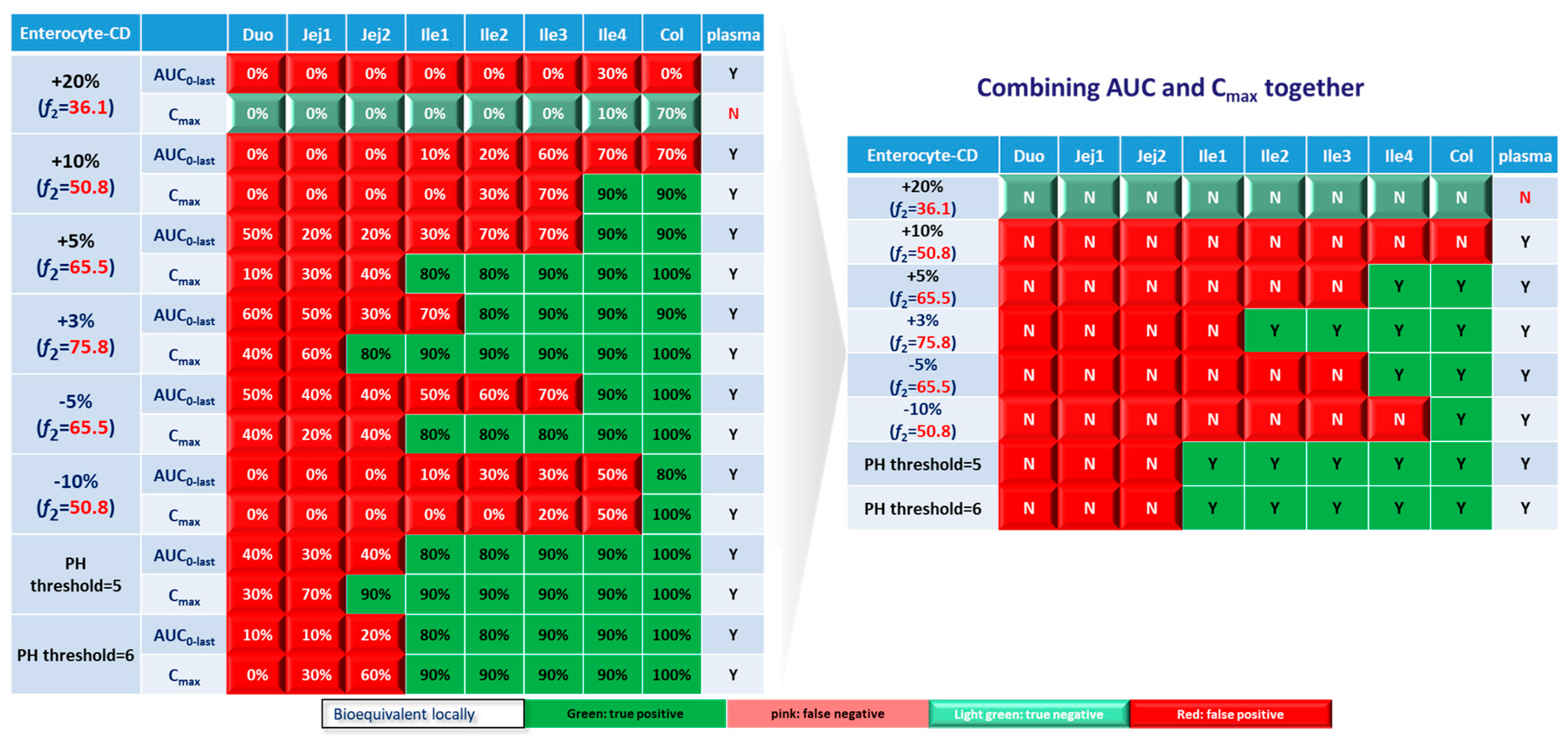

3.3. Virtual BE Heatmaps for CD Patients

The ultimate goal of bioequivalence study is to achieve the same local concentration profile and thus therapeutic effect in Crohn’s disease patients. Although investigating local and systemic BE in the CD patient population can be challenging, valuable insights can be obtained through the power of PBPK modeling. In this study, BE in local GI tracts and plasma simulated in CD patients based on lumen and enterocyte were examined. As with healthy volunteer, lumen layer tends to give similar BE results with enterocyte compartment, BE heatmap for enterocyte layer was prepared and depicted in

Figure 10.

Similar to the observations in healthy population, Cmax tend to yield more negative BE results in plasma, whereas AUC0-last is associated with higher negative rate in local GI tracts. However, for CD patients, almost all virtual formulations showed bioequivalence in plasma. In systemic BE point of view, f2 of 50 seems to be a reliable indicator of bioequivalence. Nevertheless, more simulations with formulations having f2 values lower than 50 need to be conducted to confirm the conclusion.

Regarding to sensitivity along the GI tract, as observed in healthy subjects, upper intestinal tract (duodenum, jejunum and ileum 1) in CD patients were observed to be more sensitive to changes in formulation, compared with plasma and colon. The observations in ileum sections of patients are significantly different from that in healthy populations. For CD patients, conservative area restricted to ileum 4, where 3 formulations with f2 > 65.5 showed local bioequivalence. The majority of ileum (ileum 1-3) are sensitive to the formulations. To achieve local bioequivalence in almost the entire ileum, a f2 of higher than 75.8 might be required, which mean only 3% increase at each sampling time point is tolerated in dissolution profile. As for another important target area, colon, it seems to be the most conservative GI segment in patients. All 3 formulations with f2 > 65.5 (+5%, +3% and -5%) and one formulation with f2 = 50.8 (-10%) showed bioequivalence in this area.

When it comes to formulations with altered trigger pH, it seems like such changes could be well tolerated in ileum and colon sections of CD patients, since all these segments showed bioequivalence results.

Based on above simulation results on altered dissolution rate and trigger pH, local concentrations in ileum and colon sections were very sensitive to changes in dissolution rate of formulations, which could not be reflected by clinical BE study based on PK profiles. To ensure qualified products being provided to patients, attentions should be paid to carefully characterize the dissolution profile, a product-specific higher f2 (75.8) might be needed for QC of Entocort® EC to ensure an appropriate BE in CD patients.

4. Discussion

The current work described the development and validation of PBPK models for Entocort® EC, a locally acting GI formulation with extensive gut wall and hepatic metabolism and mainly used to treat Crohn’s disease mostly happens in ileum and ascending colon. Model parameters were carefully adjusted to reflect the actual movement of budesonide pellets along the GI tract, as well as reginal absorption in local GI sections. The final model successfully recovered reginal absorption in colon, ileum and jejunum, as well as the systemic exposure after oral administration. After validation against clinical PK profiles in healthy subjects and CD patients, virtual bioequivalence between Entocort® EC and 8 virtual formulations was simulated, and BE heatmaps based on systematic and local exposure were prepared. Through the advanced modeling methods, bioequivalence at the site of action, and its correlation with the upstream dissolution and downstream system exposure under various scenarios were simulated and explored.

For GI locally action drugs with measurable systemic exposure (like Entocort® EC), quality of products or qualification of generic drugs are controlled by the in vitro dissolution profile as well as pharmacokinetic based clinical BE study. A minimum f2 of 50 is required for the dissolution of new batch or the generic drug under investigation. Our simulation results suggested that f2 of 50 is not sufficient to ensure the systemic BE in healthy volunteer, but it appears to be an appropriated cutoff value to ensure BE in the plasma of CD patients. For the correlation between f2 and local BE, due to the varied sensitivity of GI sections to formulation change, different f2 standards should be applied based on the target GI sections. For drugs targeting ileum and colon sections, a f2 of 65.5 is required to ensure BE in these two sections in healthy volunteers. As a contrast, the ileum of CD patients showed very high sensitivity to changes in dissolution rate, and a f2 of 75.8 should be met to achieve ileum BE. The colon section in CD patients showed better tolerance to formulation change compared with ileum, and a f2 of 50.8 could relate to a certain possibly of colon BE. Combining observations in ileum and colon together, a f2 of 75.8 might be a better cutoff to ensure local BE in ileum and colon sections.

With regard to clinical bioequivalence studies, it might be useful in identifying formulations that are NBE in the whole GI tract, i.e. formulations show NBE result in systemic circulation are probably NBE in all gastrointestinal segments. However, as there’s no tiered standard/parameter for pharmacokinetics-based BE, local BE could not be identified through systemic BE. Thus clinical BE study could only serve as the minimum standard.

The major pitfall for the current simulation is that based on the product specific guidance of Entocort EC, in vitro dissolution studies should cover a series of pH values including pH 4.5 in citric acid and pHs 6.0, 6.5, 6.8, 7.2 and 7.5 in PBS. On the other hand, dissolution profile of budesonide pellets used in the model were collected with FaSSIF medium. We believe the dissolution profile in FaSSIF could better mimic the actual dissolution behavior of budesonide pellets in gastrointestinal tract, the calculated f2 might be different for virtual formulations under investigation if the dissolution profiles were collected according to the product specific guidance.

Moreover, the BE in the case of drugs where metabolite contributes to pharmacological or safety aspects, requires further considerations beyond what we have demonstrated here. However, despite such shortcomings for generalization, , the current research project represents a proof-of- concept effort trying to gain more information about investigation to the BE in the case of locally acting drug/formulations in GIT, which currently remains a challenging area, requiring full-blown clinically studies with pharmacological endpoints in target patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Model Parameters and Simulation Results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.H. and C.H.; methodology, A.R.H., C.H., S.H., F.B. and T.S; software, A.R.H. and C.H.; validation, C.H and T.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.H., T.S. and M.X.; writing—review and editing, A.R.H. and C.H.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author sincerely acknowledge Dr. Daniel Scotcher (Centre for Applied Pharmacokinetic Research, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK) for valuable suggestions on the paper and for his kind help with setting the simulations and access to software and solving various problems. The author is also grateful to Dr. Kayode Ogungbenro (Centre for Applied Pharmacokinetic Research, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK) for the kind help with setting the simulations and access to software.

Heartfelt thanks to Certara UK Limited (Simcyp Division) that granted access to the Simcyp Simulators through a sponsored academic license (subject to conditions).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yu, L.X.; Li, B.V. FDA bioequivalence standards; 2014.

- CFR (Codes of Federal Regulations) 2021 Chapter 21, Part 314.

- Amidon, G.L. Bioequivalence testing for locally acting gastrointestinal drugs: Scientific principles; FDA meeting of the Advisory Committee for Pharmaceutical Science and Clinical Pharmacology: 2004.

- Olivares-Morales, A.; Kamiyama, Y.; Darwich, A.S.; Aarons, L.; Rostami-Hodjegan, A. Analysis of the impact of controlled release formulations on oral drug absorption, gut wall metabolism and relative bioavailability of CYP3A substrates using a physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 67, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loisios-Konstantinidis, I.; Cristofoletti, R.; Fotaki, N.; Turner, D.B.; Dressman, J. Establishing virtual bioequivalence and clinically relevant specifications using in vitro biorelevant dissolution testing and physiologically-based population pharmacokinetic modeling. case example: Naproxen. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 143, 105170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, T.; Acosta, M.B.; Marin-Jiménez, I.; Nos, P.; Sans, M. Oral locally active steroids in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohn's Colitis 2013, 7, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edsbäcker, S.; Andersson, T. Pharmacokinetics of budesonide (Entocort™ EC) capsules for Crohn's disease. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2004, 43, 803–821. [Google Scholar]

- Wikberg, M.; Ulmius, J.; Ragnarsson, G. Review article: Targeted drug delivery in treatment of intestinal diseases. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1997, 11, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorsson, L.; Edsbäcker, S.; Conradson, T.B. Lung deposition of budesonide from Turbuhaler is twice that from a pressurized metered-dose inhaler P-MDI. Eur. Respir. J. 1994, 7, 1839–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidegård, J.; Nyberg, L.; Borgå, O. Presystemic elimination of budesonide in man when administered locally at different levels in the gut, with and without local inhibition by ketoconazole. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 35, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilger, K.; Halter, J.R.; Bertz, H.; Lopez-Lazaro, L.; Gratwohl, A.; Finke, J.R. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic action of budesonide after buccal administration in healthy subjects and patients with oral chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009, 15, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edsbäcker, S.; Bengtsson, B.; Larsson, P.; Lundin, P.; Nilsson, Å.; Ulmius, J.; Wollmer, P. A pharmacoscintigraphic evaluation of oral budesonide given as controlled-release (Entocort) capsules. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 17, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA, New Drug Application Entocort (21-324): Clinical Pharmacology and Biopharmaceutics Review. 2000.

- Lundin, P.D.P.; Edsbäcker, S.; Bergstrand, M.; Ejderhamn, J.; Linander, H.; Högberg, L.; Persson, T.; Escher, J.C.; Lindquist, B. Pharmacokinetics of budesonide controlled ileal release capsules in children and adults with active Crohn's disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 17, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edsbäcker, S.; Larsson, P.; Bergstrand, M. Pharmacokinetics of budesonide controlled-release capsules when taken with omeprazole. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 17, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidegård, J. Reduction of the inhibitory effect of ketoconazole on budesonide pharmacokinetics by separation of their time of administration. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 68, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidegård, J.; Simonsson, M.; Edsbäcker, S. Effect of an oral contraceptive on the plasma levels of budesonide and prednisolone and the influence on plasma cortisol. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 67, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidegård, J.; Randvall, G.; Nyberg, L.; Borga, O. Grapefruit juice interaction with oral budesonide: Equal effect on immediate-release and delayed-release formulations. Pharmazie 2009, 64, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lundin, P.; Naber, T.; Nilsson, M.; Edsbäcker, S. Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of budesonide controlled ileal release capsules in patients with active Crohn's disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 15, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.; Tirona, R.G.; Kim, R.B. CYP3A4 activity is markedly lower in patients with Crohn's disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effinger, A.; O'Driscoll, C.M.; McAllister, M.; Fotaki, N. Predicting budesonide performance in healthy subjects and patients with Crohn's disease using biorelevant in vitro dissolution testing and PBPK modeling. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 157, 105617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrubia, S.; Mao, J.; Chen, Y.; Barber, J.; Rostami-Hodjegan, A. Altered bioavailability and pharmacokinetics in Crohn's disease: Capturing systems parameters for PBPK to assist with predicting the fate of orally administered drugs. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2022, 61, 1365–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerberg, J.H.; Sjögren, E.; Bergström, C.A.S. Concomitant intake of alcohol may increase the absorption of poorly soluble drugs. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 67, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, G.M.; Orrego, H.; Israel, Y.; Devenyi, P.; Kapur, B.M. Low-molecular-weight polyethylene glycol as a probe of gastrointestinal permeability after alcohol ingestion. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1981, 26, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huo, M.; Zhou, J.; Zou, A.; Li, W.; Yao, C.; Xie, S. DDSolver: An add-In program for modeling and comparison of drug dissolution profiles. AAPS J. 2010, 12, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA, SUPAC-IR: Immediate-Release Solid Oral Dosage Forms: Scale-Up and Post-Approval Changes: Chemistry, Manufacturing and Controls, In Vitro Dissolution Testing, and In Vivo Bioequivalence Documentation. 1995.

- Alrubia, S.; Al-Majdoub, Z.M.; Achour, B.; Rostami-Hodjegan, A.; Barber, J. Quantitative assessment of the impact of Crohn's disease on protein abundance of human intestinal drug-metabolising enzymes and transporters. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 111, 2917–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Workflow of PBPK model and virtual bioequivalence in this study. PE: parameter estimation; MW: molecular weight; fu: unbound fraction; BP: blood plasma; IV: intravenous; Pgp: P-glycoprotein; PO: by mouth; LSA: local sensitivity analysis; SI: small intestine; HSA: human serum albumin; BE: bioequivalence; NCA: non-compartmental analysis; HV: healthy volunteer; CD: Crohn’s disease; BP: blood plasma, PPB: plasma.

Figure 1.

Workflow of PBPK model and virtual bioequivalence in this study. PE: parameter estimation; MW: molecular weight; fu: unbound fraction; BP: blood plasma; IV: intravenous; Pgp: P-glycoprotein; PO: by mouth; LSA: local sensitivity analysis; SI: small intestine; HSA: human serum albumin; BE: bioequivalence; NCA: non-compartmental analysis; HV: healthy volunteer; CD: Crohn’s disease; BP: blood plasma, PPB: plasma.

Figure 2.

Dissolution profiles of reference and virtual test formulations. Blue thick line with dot: dissolution profile of reference formulation collected from paper [

21]; thin line: formulations showing faster dissolution rate compared with reference; dotted line: formulations with slower dissolution rate. +20%: formulation with 20% more dissolution than reference at everything sampling time point, and so on;

f2 similarity factor.

Figure 2.

Dissolution profiles of reference and virtual test formulations. Blue thick line with dot: dissolution profile of reference formulation collected from paper [

21]; thin line: formulations showing faster dissolution rate compared with reference; dotted line: formulations with slower dissolution rate. +20%: formulation with 20% more dissolution than reference at everything sampling time point, and so on;

f2 similarity factor.

Figure 3.

Example bioequivalence bar chart based on Cmax. Grey dotted line: 80% and 125%; black dots: geometric mean of test versus reference in GI segments; red square: geometric mean of test versus reference in plasma; bar: 90% confidence of the geometric mean of test over reference. GMR: geometric mean of test/reference; CI: confidence interval. Duo: duodenum; Jej1 and Jej2: jejunum sections 1 and 2; Ile1, Ile2, Ile3 and Ile4: ileum sections 1 to 4; Col: colon.

Figure 3.

Example bioequivalence bar chart based on Cmax. Grey dotted line: 80% and 125%; black dots: geometric mean of test versus reference in GI segments; red square: geometric mean of test versus reference in plasma; bar: 90% confidence of the geometric mean of test over reference. GMR: geometric mean of test/reference; CI: confidence interval. Duo: duodenum; Jej1 and Jej2: jejunum sections 1 and 2; Ile1, Ile2, Ile3 and Ile4: ileum sections 1 to 4; Col: colon.

Figure 5.

BE heatmap of 8 virtual formulations based on AUC and Cmax in enterocyte layer of GI sections and plasma in healthy population. Percentage in the box indicates the incidence of BE result in 10 trials. Y indicates BE in plasma. N means NBE in plasma. Green: local BE result consistent with that in plasma. Red: local BE result inconsistent with plasma. Cells with 3D bevel effect: not BE in local GI section. Flat cells: BE locally.

Figure 5.

BE heatmap of 8 virtual formulations based on AUC and Cmax in enterocyte layer of GI sections and plasma in healthy population. Percentage in the box indicates the incidence of BE result in 10 trials. Y indicates BE in plasma. N means NBE in plasma. Green: local BE result consistent with that in plasma. Red: local BE result inconsistent with plasma. Cells with 3D bevel effect: not BE in local GI section. Flat cells: BE locally.

Figure 6.

BE heatmap of 8 virtual formulations based on combined results of AUC and Cmax in enterocyte layer of GI sections and plasma in healthy population. Y indicates BE in GI segments and plasma. N means NBE in GI segments and plasma. Green: local BE result consistent with that in plasma. Red: local BE result inconsistent with plasma. Cells with 3D bevel effect: not BE in local GI section. Flat cells: BE locally.

Figure 6.

BE heatmap of 8 virtual formulations based on combined results of AUC and Cmax in enterocyte layer of GI sections and plasma in healthy population. Y indicates BE in GI segments and plasma. N means NBE in GI segments and plasma. Green: local BE result consistent with that in plasma. Red: local BE result inconsistent with plasma. Cells with 3D bevel effect: not BE in local GI section. Flat cells: BE locally.

Figure 7.

BE bar charts (based on Cmax) of the +10% formulation in 10 trials. Grey dotted line: 80% and 125%; black dots: geometric mean of test versus reference in GI segments; red square: geometric mean of test versus reference in plasma; bar: 90% confidence of the geometric mean of test over reference. GMR: geometric mean of test/reference; CI: confidence interval.

Figure 7.

BE bar charts (based on Cmax) of the +10% formulation in 10 trials. Grey dotted line: 80% and 125%; black dots: geometric mean of test versus reference in GI segments; red square: geometric mean of test versus reference in plasma; bar: 90% confidence of the geometric mean of test over reference. GMR: geometric mean of test/reference; CI: confidence interval.

Figure 8.

BE bar charts (based on Cmax) of the -10% formulation in 10 trials. Grey dotted line: 80% and 125%; black dots: geometric mean of test versus reference in GI sgements; red square: geometric mean of test versus reference in plasma; bar: 90% confidence of the geometric mean of test over reference. GMR: geometric mean of test/reference; CI: confidence interval.

Figure 8.

BE bar charts (based on Cmax) of the -10% formulation in 10 trials. Grey dotted line: 80% and 125%; black dots: geometric mean of test versus reference in GI sgements; red square: geometric mean of test versus reference in plasma; bar: 90% confidence of the geometric mean of test over reference. GMR: geometric mean of test/reference; CI: confidence interval.

Figure 9.

BE heatmap of 8 virtual formulations based on AUC and Cmax in lumen layer of GI sections and plasma in healthy population. Percentage in the box indicates the incidence of BE result in 10 trials. Y indicates BE in plasma. N means NBE in plasma. Green: local BE result consistent with that in plasma. Red: local BE result inconsistent with plasma. Cells with 3D bevel effect: not BE in local GI section. Flat cells: BE locally.

Figure 9.

BE heatmap of 8 virtual formulations based on AUC and Cmax in lumen layer of GI sections and plasma in healthy population. Percentage in the box indicates the incidence of BE result in 10 trials. Y indicates BE in plasma. N means NBE in plasma. Green: local BE result consistent with that in plasma. Red: local BE result inconsistent with plasma. Cells with 3D bevel effect: not BE in local GI section. Flat cells: BE locally.

Figure 10.

BE heatmap of 8 virtual formulations based on AUC and Cmax in enterocyte layer of GI sections and plasma in Crohn’s disease patients. Percentage in the box indicates the incidence of BE result in 10 trials. Y indicates BE in plasma. N means NBE in plasma. Green: local BE result consistent with that in plasma. Red: local BE result inconsistent with plasma. Cells with 3D bevel effect: not BE in local GI section. Flat cells: BE locally.

Figure 10.

BE heatmap of 8 virtual formulations based on AUC and Cmax in enterocyte layer of GI sections and plasma in Crohn’s disease patients. Percentage in the box indicates the incidence of BE result in 10 trials. Y indicates BE in plasma. N means NBE in plasma. Green: local BE result consistent with that in plasma. Red: local BE result inconsistent with plasma. Cells with 3D bevel effect: not BE in local GI section. Flat cells: BE locally.

Table 1.

Summary of clinical studies used for model development (1-4) and validation (5-10) in healthy subjects and validation (11, 12) in CD patients.

Table 1.

Summary of clinical studies used for model development (1-4) and validation (5-10) in healthy subjects and validation (11, 12) in CD patients.

| No. |

Formulation |

Dose |

No. of subjects (gender)a

|

Age |

Weight (Kg) |

Reference |

| 1 |

IV |

0.5mg |

12 (M); 12 (F) |

22-53 |

45-92 |

[9] |

| 2 |

Solution(local) |

2.6mg (1mL) |

8 (M) |

20-44 |

63-111 |

[10] |

| 3 |

Solution |

3mg (10ml) |

6 (M); 6 (F) |

43.7±7.1 |

71.5±10.3 |

[11] |

| 4 |

Entocort® EC |

18mg |

8 (M) |

40-53 |

77-94 |

[12] |

| 5 |

Entocort® EC |

3, 9, 15mg |

5 (M); 8 (F) |

NA |

NA |

[13] |

| 6 |

Entocort® EC |

4.5mg |

6 (M) |

43-56 |

NA |

[14] |

| 7 |

Entocort® EC |

9mg |

6 (M); 6 (F) |

21-42 |

NA |

[15] |

| 8 |

Entocort® EC |

3mg |

8 (M) |

22-40 |

85 (66-107) |

[16] |

| 9 |

Entocort® EC |

4.5mg |

40 (F) |

19-38 |

61.5 (46-86) |

[17] |

| 10 |

Entocort® EC |

3mg |

8 (M) |

20-42 |

75 (60-91) |

[18] |

| 11 |

Entocort® EC |

9mg |

4 (M); 4 (F) |

24-50 |

BMI 24.9 (18.5-29.7) |

[19] |

| 12 |

Entocort® EC |

1mg |

1 (M); 7 (F) |

25-70 |

57.4-104 |

[20] |

Table 2.

Similarity factor and Weibull function parameters of Entocort® EC and virtual formulations.

Table 2.

Similarity factor and Weibull function parameters of Entocort® EC and virtual formulations.

| Formulation |

f2

|

The similarity between R and T |

Fmax

|

α |

β |

Trigger pH |

| Entocort® EC |

- |

- |

100 |

3.12 |

0.94 |

5.5 |

| +20% |

36.1 |

N |

100 |

1.53 |

0.87 |

5.5 |

| +10% |

50.8 |

Y |

100 |

2.14 |

0.89 |

5.5 |

| +5% |

65.5 |

Y |

100 |

2.56 |

0.91 |

5.5 |

| +3% |

75.8 |

Y |

100 |

2.77 |

0.92 |

5.5 |

| -5% |

65.5 |

Y |

100 |

3.90 |

1.01 |

5.5 |

| -10% |

50.8 |

Y |

100 |

5.01 |

1.09 |

5.5 |

| PH threshold=5 |

- |

- |

100 |

3.12 |

0.94 |

5 |

| PH threshold=6 |

- |

- |

100 |

3.12 |

0.94 |

6 |

Table 3.

Parameters included in LSA and corresponding ranges.

Table 3.

Parameters included in LSA and corresponding ranges.

| Parameters |

Ranges covered by LSA |

Range in HV |

Reported ranges in CD patients |

| |

[21] |

[22] |

[27] |

| Gastric MRT (h) |

0.27-2.5 |

0.27 |

0-2.5 |

0.26(Active); 0.3(Inactive) |

|

| SI MRT (h) |

3.4-6 |

3.4 |

3-6 |

4.2(Active); 3.2(Inactive) |

|

Liver CYP3A4 abundance

(pmol/mg protein)

|

34.35-137 |

137 |

31.5 (M), 45.75(F) (low);

38.49 (M), 55.91(F) (high) |

55.4(M); 80.5(F) |

|

| SI CYP3A4 abundance (nmol/SI) |

8.6-65.4 |

65.4 |

60.53 (low);

98.53 (high) |

52.3 |

8.6(Inflamed);

15.6(Noninflamed) |

| HSA (g/L) |

30-50 |

50.34 (M);

49.38(F) |

31.72(M), 27.2(F) (low);

41 (high) |

Study one: 30.13(M);25.2(F)

Study two: 44.8(M);43.9(F) |

|

Colon CYP3A4 abundance

(nmol/colon)

|

0.2-1.99 |

1.99 |

|

2.4 |

0.2(Inflamed);

0.5(Noninflamed) |

Transporter abundance

(pmol/mg total membrane protein)

|

Jejunum I:

0.075-0.4 |

Jejunum I:

0.4 |

|

Ileum I-IV:1.2

Colon: 0.17(Active);

0.55(Inactive) |

Jejunum I:

0.12(Inflamed); 0.075(Noninflamed) |

Table 4.

Demographic parameters that were adjusted to build CD population.

Table 4.

Demographic parameters that were adjusted to build CD population.

| Parameter |

HV |

CD |

Reference |

| Liver CYP3A4 abundance (pmol/mg protein) |

137 |

55.4(M); 80.5(F) |

[22] |

| SI CYP3A4 abundance (nmol/SI) |

65.4 |

8.6 |

[27] |

| Colon CYP3A4 abundance |

1.99 |

0.2 |

[27] |

| HSA(g/L) |

50.34(M); 49.38(F) |

30.13(M); 25.2(F) |

[22] |

Table 5.

Within subject variability used in VBE studies of Entocort® EC.

Table 5.

Within subject variability used in VBE studies of Entocort® EC.

| Parameters |

Variation (CV%) |

Minimum Limit |

Parameter value |

Maximum Limit |

| Fasted MRT Stomach Fluid |

38.217 |

0.01 |

0.27 |

12 |

| Fasted MRT SI Fluid |

21.132 |

0.5 |

3.4 |

12 |

| Male WColon MRT Fluid |

44.962 |

0.1 |

37.5 |

240 |

| Male AColon MRT Fluid |

44.962 |

0.1 |

18.91 |

72 |

| Female WColon MRT Fluid |

44.962 |

0.1 |

55.75 |

240 |

| Female AColon MRT Fluid |

44.962 |

0.1 |

23.11 |

72 |

Table 6.

Overview of predicted and observed PK parameters and calculated fold error.

Table 6.

Overview of predicted and observed PK parameters and calculated fold error.

Clinical

study |

Subject |

Formulation |

Dose

(mg) |

Observed values |

Simulated values |

Ratio: sim/obs |

AUC0-t

(nM*h) |

Cmax

(nM) |

AUC0-t

(nM*h) |

Cmax

(nM) |

AUC0-t

|

Cmax

|

| 1 |

HV |

IV bolus |

0.5 |

15.27 |

11.1 |

12.66 |

9.12 |

0.83 |

0.82 |

| 2-1 |

HV |

Solution (Jejunum)* |

2.6(1ml) |

8.52 |

3.14 |

8.19 |

3.38 |

0.96 |

1.08 |

| 2-2 |

HV |

Solution (Ileum)* |

2.6(1ml) |

11.77 |

5.31 |

11.18 |

5.19 |

0.95 |

0.98 |

| 2-3 |

HV |

Solution (Colon)* |

2.6(1ml) |

8.56 |

2.36 |

10.05 |

2.44 |

1.17 |

1.03 |

| 3 |

HV |

Solution (Oral) |

3(10ml) |

6.58 |

2.15 |

8.30 |

1.84 |

1.26 |

0.86 |

| 4 |

HV |

Entocort® EC |

18 |

51.49 |

5.92 |

54.78 |

5.74 |

1.06 |

0.97 |

| 5-1 |

HV |

Entocort® EC |

3 |

12.98 |

1.77 |

9.17 |

0.96 |

0.71 |

0.54 |

| 5-2 |

HV |

Entocort® EC |

9 |

38.65 |

3.74 |

27.68 |

2.95 |

0.72 |

0.79 |

| 5-3 |

HV |

Entocort® EC |

15 |

59.37 |

7.08 |

45.83 |

4.81 |

0.77 |

0.68 |

| 6 |

HV |

Entocort® EC |

4.5 |

18.72 |

2.21 |

14.06 |

1.47 |

0.75 |

0.67 |

| 7 |

HV |

Entocort® EC |

9 |

26.41 |

4.18 |

21.47 |

2.80 |

0.81 |

0.67 |

| 8 |

HV |

Entocort® EC |

3 |

12.24 |

1.16 |

8.23 |

0.87 |

0.67 |

0.75 |

| 9 |

HV |

Entocort® EC |

4.5 |

13.15 |

1.39 |

14.03 |

1.45 |

1.07 |

1.04 |

| 10 |

HV |

Entocort® EC |

3 |

11.75 |

1.28 |

8.23 |

0.88 |

0.70 |

0.69 |

| 11 |

CD patients |

Entocort® EC |

9 |

27.27 |

4.32 |

45.35 |

5.39 |

1.66 |

1.25 |

| 12 |

CD patients |

Entocort® EC |

1 |

4.41 |

0.56 |

4.35 |

0.52 |

0.99 |

0.93 |

Table 7.

Simulated tmax and Cmax in plasma and different sections of GI tract.

Table 7.

Simulated tmax and Cmax in plasma and different sections of GI tract.

| Endpoint |

tmax (h)lumen/enterocyte |

Cmax, lumen (nM) |

Cmax, enterocyte (nM) |

| Plasma |

3 |

0.94 |

- |

| Duodenum |

1/0.5 |

459 |

2.67 |

| Jejunum I |

1/1 |

10,455 |

43.2 |

|

Jejunum II

|

2/2 |

16,745 |

31.3 |

| Ileum I |

2/2 |

20,767 |

102 |

|

Ileum II

|

3/2 |

17,769 |

91.1 |

|

Ileum III

|

3/3 |

17,825 |

83.3 |

|

Ileum IV

|

3/3 |

15,935 |

75.2 |

| Colon |

6/6 |

152,267 |

1,092 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).