Introduction

Within the development of new compounds for the treatment of diseases or conditions influenced by oxidative stress, synthetic antioxidants such as 2(3)-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyanizole (BHA), 2,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxytoluene (BHT) [

1,

2], Edaravone [

3] have been developed among others, which have been shown to have a good capacity as neutralizers of free radicals produced by oxidative stress. In addition to these compounds, a wide variety of compounds linked to metal groups have been developed, in which it has been shown that these compounds have greater biological activity as antioxidants [

4,

5]. For the synthesized series,

in vitro tests of the antioxidant activity against different substrates (DPPH, ABTS˙+, EDTA, FRAB) have been carried out, therefore with different methodologies, but not simulating the cellular environment. Therefore, the results have shown that the antioxidant activity varies according to the selected method. Studies on the mechanism by which radical neutralization is carried out for this type of compounds at an experimental and theoretical level are few [

3].

To know the mechanism by which the neutralization of free radicals is carried out and its effectiveness, the theory of the transition state [

6,

7,

8,

9] and the Marcus theory [

10] described by chemical kinetics are very useful. Within the reaction mechanisms that are studied in chemical kinetics are: the mechanism of electron transfer (ET), hydrogen transfer (HT) and the formation of adduct with the radical (FAR).

With the calculated values of the reaction energy for each reaction channel (radical-molecule interaction site) and using the Marcus theory, the activation energy for the electronic transfer mechanism is obtained. With the value of , the reaction rate constant is calculated using the transition state theory for the mechanism of electron transfer and hydrogen abstraction. Since the ˙OH, and ˙OOH radicals are transported in the cell medium by diffusion, the apparent rate constant for the electron transfer mechanism was calculated.

The objective of this work is to evaluate the antiradical capacity from the modifications in the substituent linked to the metal center to determine the influence of the presence of the metal in the reaction mechanism and its efficiency as a radical scavenger of reactive oxygen species (ROS) simulating the cellular environment.

The presence of Sn(IV) in the p-coumaric acid molecule seems to contribute to increasing the reactivity in reaction channel 4a, with the ET mechanism being the one with the highest efficiency in polar media and HT in nonpolar media.

Computational details

Khon-Sham approximation was used at Density Functional Theory [

11,

12] implemented in Gaussian 09 [

13]. Truhlar M05 functional were employed [

14]. 6-311+G (d, p) [

15] basis set for N, O, C and H atoms and LANL2DZ pseudo-potentials and basis set [

16,

17,

18] for Sn(IV) atom were also employed. The M05 functional has been recommended for kinetics calculation by its developers (14) for systems which commonly presents multireference character, and it has been successfully used by independent authors for that purpose [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

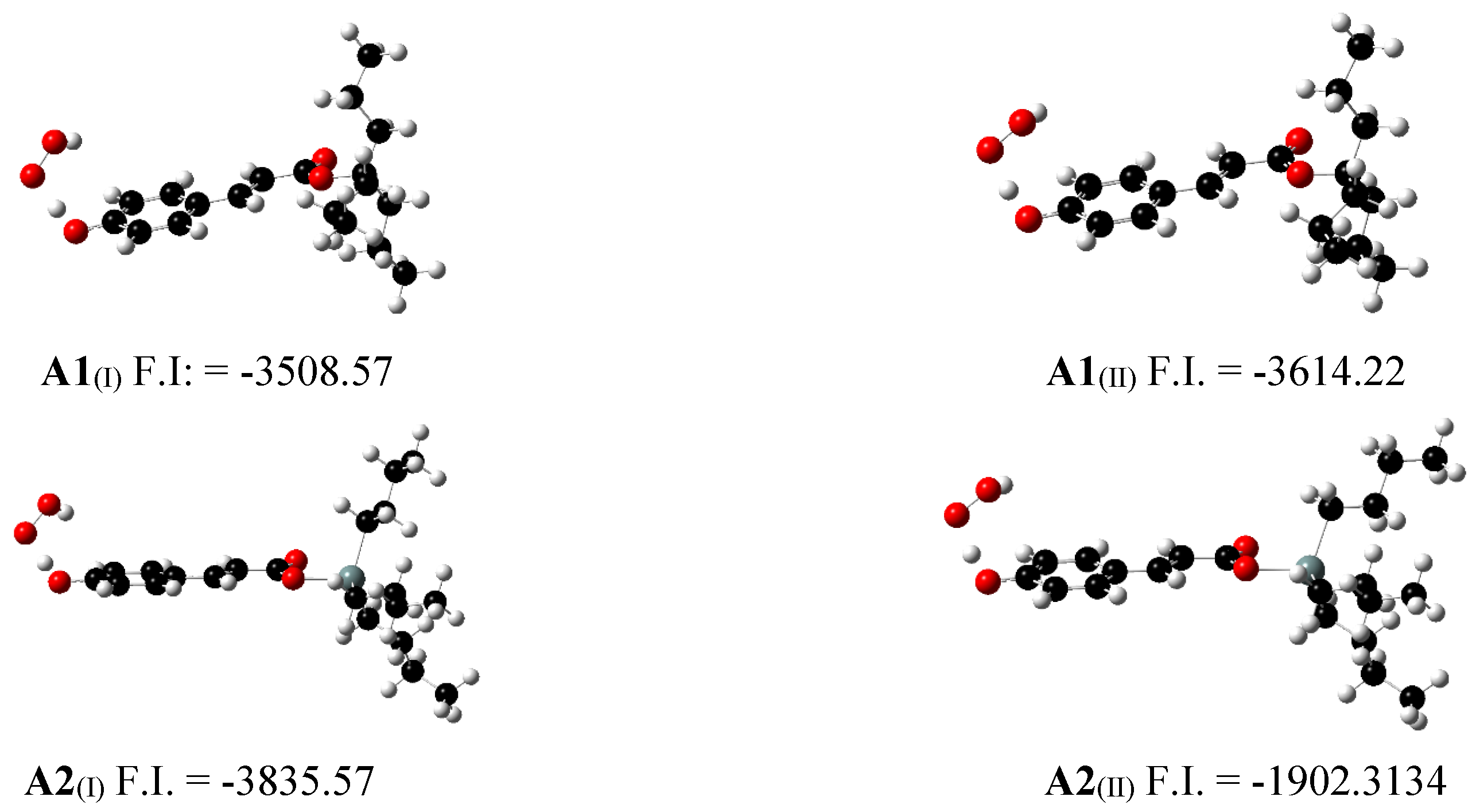

27]. Full geometry optimization for

p-cumaric esters (

Figure 1) were performed without symmetry constrains. Harmonic frequency analysis was made to verify optimized local minima and transitions states at the potential energy surface. Local minima have only real frequencies, while transition states have one negative frequency that corresponds to the expected motion along the reaction coordinate.

Relative energies are computed with respect to the sum of the separated reactants. Solvent effect is taken into account to describe the molecular and biological system and their properties, due to its important role in biochemical process. Solvent effects are considered employing the SDM continuum model [

28] using water and pentylethanoate as solvents, to mimic de cellular environment. The solvent cage effect has been considered according to the correction proposed by Okumo [

29], taking into account the free energy volume theory [

30]. Both corrections described above are in good agreement with those obtained by Ardura et al [

31] and successfully used by other authors [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. The expression used to correct Gibbs free energy is.

where n is the molecularity of the reaction. According to equation 1, the cage effect in solution causes

to decrease by 2.54 kcal/mol for bimolecular reactions, at 298.15 K.

The rate constant (

) was computed employing the conventional transition state theory (TST) [

39,

40,

41] and 1 M standard state as

where

and

are the Boltzmann and Plank constants, respectively, T is the temperature in K, R is the universal gas constant,

is the activation energy,

represents the reaction path degeneracy, accounting for the number of equivalent reaction path, and

accounts for the tunneling correction, defined as the Boltzmann average of the ratio of the quantum and the classical probabilities, they were computed using the zero-curvature tunneling correction (ZCT) [

42] (38). TST has been proven to be enough for properly describing chemical reactions between free radicals and antioxidants [

43].

For the mechanism involving single electron transfer (ET), the Marcus theory was employed [

44,

45] to calculate the energy barrier of activation

in terms of two thermodynamic parameters, the free energy of reaction

and the nuclear reorganization energy (

)

where

is calculated as:

where,

is the non-adiabatic energy difference between reactants and vertical products. Some of the calculated rate constants (

) values are close to diffusion-limit. Accordingly, the apparent rate constant cannot be directly obtained from TST calculations. In the present work the Collins-Kimball Theory [

46] is used to correct the rate constant, and

is calculated as:

where

is the thermal rate constant computed by TST calculation, and

is the steady-state Smoluchowski rate constant for an irreversible bimolecular diffusion-controlled reaction:

where

R denotes the reaction distance,

is the Avogadro number and

is the mutual diffusion coefficient of the reactants A (free radical) and B (

p-cumaric ester).

is computed from

y

according to reference [

47],

y

have been estimated from the Stokes-Einstein approach [

48].

where

is the temperature, η the viscosity of the solvent, in our case water (η = 8.91 x 10

-4 Pa s) and pentylethanoate (η = 8.62 x 10

-4 Pa s); and

is the radius of the solute.

Direct reaction branching ratios (Γ) are computed as:

We have chosen the average reported

for

p-cumaric acid (4.38) [

49], to obtain the pKa for

ter-butyl

p-cumarate and tri-butyl-tin

p-cumarate by using the method proposed by Ho [

50]

where

, is the anion free energy formation and

is the pKa of the most similar acid. Thus, in aqueous solution at pH = 7.4, the neutral form of

ter-butyl

p-cumarate (A1) and tri-butyl-tin

p-cumarate (A2) would predominate (97.7% and 97.6% respectively) over the deprotonated form (A

1ˉ 2.3 % and A

2ˉ 2.4 % respectively). In this work both, neutral and deprotonated, forms will be used to study their reactivity toward the considered free radicals in water, while in lipid media only the neutral form will be considered.

Results and discussion

Reaction mechanism and kinetics for

ter-butyl

p-cumarate ester and its counterpart

tri-butyl tin-

p-cumarate ester,

Figure 1, are shown. Once optimized ester geometries are obtained, multireference character is determined by a single point calculation employing CCSD method to compute the T1 parameter. T1 parameter is used to know multireference character of an organometallic complex [

51,

52] For neutral molecules, if the T1 value is higher than 0.023, they have mutireference and for transition state geometries, if T1 is higher than 0.044, they have multireference character. The T1 values for A1 and A2 was 0.032.

The theoretical calculations performed in this work address the following reaction pathways:

1.- Hydrogen transfer (HT)

A-H + R˙ → A˙ + R-H

2.- Radical adduct formation (RAF)

A-H + R˙ → [A-H-R]˙

3.- Single electron Transfer from neutral form (SET-1)

A-H + R˙ → A˙+ + Rˉ

4.- Single electron transfer from deprotonated form (SET-2)

Aˉ + R˙ → A˙ + Rˉ

In the HT mechanism we have considered the Hydrogen atom abstraction from the hydroxyl group at the position 4, and the abstraction of the hydrogen atoms bounded to carbons at the 7 and 8 positions. The object of the present work is to determinate how the presence of the Sn(IV) influences the different reaction mechanism and their rate constants in the reaction of A1 and A2 with the ˙OOH and ˙OH free radicals, in water and in lipid media. The thermochemical feasibility of the different mechanism and channels of reaction was investigated first, since it determinates the viability of chemical process.

For

A1 and

A2 molecules,

values, mol fraction in aqueous solution, bond dissociation energy (BDE) for hydrogen atoms on reaction channels 7 (C7), 8 (C8) and OH on C4 reaction channel for the HT

-1 mechanism, in water and pentylethanoate media, was computed and shown in

Table 1.

BDE for channel 4a showed the lowest value in comparison with reaction channel 7 and 8, whereby channel 4a is energetically the most viable for A1 and A2. BDE for the molecule A2 slightly increases with the presence of the Sn(IV) moiety.

Single electron transfer (SET) mechanism

Relative reaction Gibbs free energy values (

) for the

SET-1 and

SET-2 mechanisms, calculated at 298.15 K in water and pentylethanoate with radical ˙OOH and ˙OH, are shown in

Table 1.

Table 2.

Reaction Gibbs free energy (ΔG0), in kcal/mol, with the ˙OOH and ˙OH radical, in water and pentylethanoate at 298.15 K.

Table 2.

Reaction Gibbs free energy (ΔG0), in kcal/mol, with the ˙OOH and ˙OH radical, in water and pentylethanoate at 298.15 K.

| Channel |

A1(I)

|

A1(II)

|

A2(I)

|

A2(II)

|

| |

ΔG0

|

ΔG0

|

ΔG0

|

ΔG0

|

| |

˙OOH |

˙OH |

˙OOH |

˙OH |

˙OOH |

˙OH |

˙OOH |

˙OH |

| SET-1 |

26.04 |

0.62 |

64.88 |

41.35 |

26.54 |

0.82 |

68.21 |

44.67 |

| SET-2 |

2.62 |

-22.97 |

- |

- |

0.81 |

-24.91 |

- |

- |

For the SET-1 mechanism, where the radical cation is formed from neutral geometry, the reaction Gibbs free energy (), in aqueous solution, with the radical ˙OOH is highly endergonic for A1 and A2 and the reaction is not viable. With ˙OH radical, the reaction is slightly endergonic. Activation energy values for A2 reaction with ˙OH radicals decrease with respect to A1. The rate order of the apparent rate constant for reaction of A1 and A2 with ˙OH radical doesn´t change, 109 M−1 s−1, showing that the presence of the Sn(IV) in A2 contributes to decrease the height of the barrier but not to decrease the width, which is essential in the electron tunnel effect, but this contribution do not influence to improve the scavenger activity.

In pentylethanoate is highly endergonic with both ˙OOH and ˙OH radicals because the formation of the ionic specie is not viable. Comparing behavior of A1 and A2 in their neutral form, an increase in is shown with the ˙OOH and ˙OH radicals in aqueous and lipid media. This shows that the presence of the Sn(IV) in the organometallic moiety acts like an electro-acceptor group, withdrawing electron density to the ester.

For the SET-2 mechanism is endergonic with the radical ˙OOH and highly exergonic with the radical ˙OH. For A2, which has a Sn(IV), is less endergonic in the reaction with ˙OOH radical and more exergonic with ˙OH radical, in comparison to A1. It shown that the organometallic moiety acts like an electron-donor group, donating electron density to the ester in their deprotonated form favoring the charge transfer. Contrary to that shown for SET-1 mechanism.

Activation energy values on the reaction of A2 with ˙OOH radical, slightly decreases in comparison with A1. On the other hand, on the reaction of A2 with ˙OH radical, decreases considerably in comparison with A1.

Table 3.

Reaction Gibbs activation energy ΔG‡ in kcal/mol, apparent rate constant kapp in M−1 s−1.

Table 3.

Reaction Gibbs activation energy ΔG‡ in kcal/mol, apparent rate constant kapp in M−1 s−1.

| |

A1(I)

|

A2(I)

|

| SET-1 |

ΔG‡

|

kapp |

ΔG‡

|

kapp |

| ˙OOH |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| ˙OH |

1.28 |

8.55 × 109

|

0.34 |

8.78 × 109

|

| SET-2 |

ΔG‡

|

kapp |

ΔG‡

|

kapp |

| ˙OOH |

4.65 |

1.25 × 106

|

4.03 |

9.13 × 107

|

| ˙OH |

44.41 |

8.53 × 10-24

|

28.40 |

2.12 × 108

|

With respect to the apparent rate constant

for reaction of

A1 and

A2 with ˙OOH and ˙OH radicals, the order of

increases from 10

6 M

−1 s

−1 to 10

7 M

−1 s

−1 on the reaction with radical ˙OOH and, from 10

−24 M

−1 s

−1 to 10

8 M

−1 s

−1 for reaction with radical ˙OH. Therefore, the presence of Sn(IV) contributes to improve the reactivity of the ester increasing its efficiency like a scavenger. The order of

for

A2 with the radical ˙OOH, is comparable with that shown by glutation (2.7 × 10

7 M

−1 s

−1) [

53] and the propensulphonic acid (2.6 × 10

7 M

−1 s

−1) [

54].

Hydrogen Transfer (HT) Mechanism

Gibbs free energy values

in kcal/mol for

HT mechanism, regarding reaction channels 4a, 7 y 8 in aqueous media are shown in

Table 1. On reaction of

A1 y

A2 with radical ˙OOH,

for reaction channel 7 y 8 is endergonic, in both, aqueous and lipid media. In reaction channel 7,

increases in water and decreases in lipid media with the presence of Sn(IV), which shows that the presence of Sn(IV) favored the reaction in lipid media. For reaction channel 8, the presence Sn(IV) on

A2 contribute to increase

, even in water and lipid media. Therefore, reaction channel 8 is the less favored.

Table 4.

Reaction Gibbs free energy in kcal/mol for A1 and A2 esters with radical ˙OOH and ˙OH.

Table 4.

Reaction Gibbs free energy in kcal/mol for A1 and A2 esters with radical ˙OOH and ˙OH.

| |

A1(I)

|

A1(II)

|

A2(I)

|

A2(II)

|

| 4a |

|

|

|

|

| ˙OOH |

-6.65 |

1.75 |

-6.27 |

-4.27 |

| ˙OH |

-41.92 |

-33.94 |

-42.04 |

-39.97 |

| 7 |

|

|

|

|

| ˙OOH |

12.67 |

16.06 |

14.31 |

15.93 |

| ˙OH |

-23.09 |

-19.64 |

-21.46 |

-19.76 |

| 8 |

|

|

|

|

| ˙OOH |

23.16 |

23.85 |

87.47 |

24.79 |

| ˙OH |

-12.11 |

-11.86 |

51.71 |

-10.92 |

On the other hand, reaction with ˙OH radical, in reaction channels 7 y 8 is exergonic, except for A2 on water, where is highly endergonic. In aqueous and lipid media, an increase in for reaction channel 7 on A2 is show in presence of Sn(VI) in comparison with A1. For reaction channel 8, is exergonic on A1 in water and lipid media. For A2, the presence of the Sn(IV) increases considerably in water media. In lipid media the presence of Sn(IV) on A2 contributes to increase , showing that channel 7 is more viable than channel 8, and that the presence of the Sn(IV) contributes to increase of HT mechanism.

For reaction channel 4a, is exergonic for the reaction with radical ˙OOH on A1 (except in lipid media) and A2. On water, Gibbs free energy slightly increases with the presence of Sn(IV). In pentylethanoate, is endergonic for A1, and exergonic when Sn(IV) is present on A2, showing that the presence of Sn(IV) influences the transferring of light atoms like H.

For reaction with radical ˙OH, is exergonic, even higher than that shown on channel 7 y 8, therefore, reaction channel 4a is the most viable, in both, pentylethanoate and water media. When Sn(IV) is included in A2, is more exergonic than A1, which means, that the presence of the Sn(IV) contributes to increase the hydrogen transfer in both media.

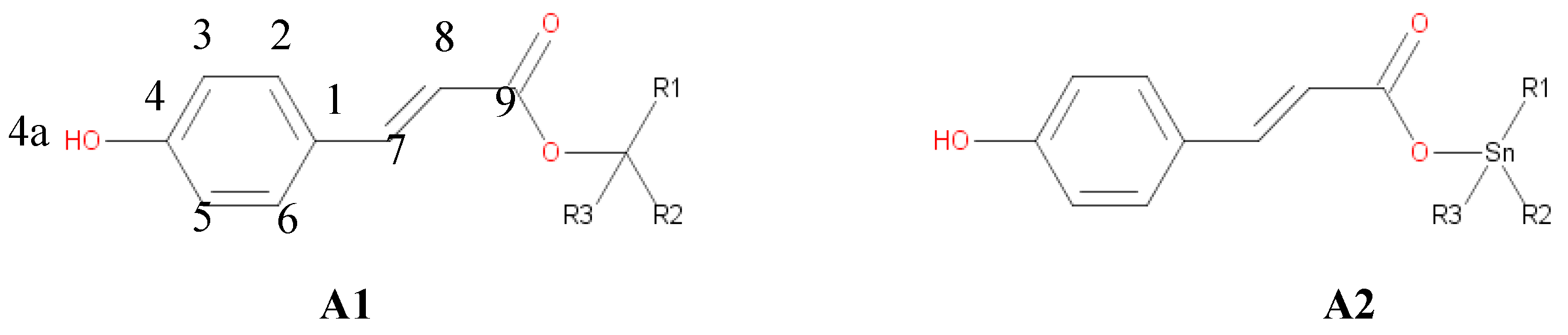

For hydrogen transfer mechanism, transition state geometries were optimized for A1 and A2 with ˙OOH radical, verifying that each transition state has a negative frequency corresponding to the reaction coordinate. Transition state geometries, for reaction with ˙OH radical, cannot be obtained. Even their are highly exergonic, and it is probably that the reaction is carried out by diffusion.

Figure 2.

Optimized transition state geometry of A1 and A2 with radical ˙OOH in water (I) and pentylethanoate (II) and their imaginary frequencies.

Figure 2.

Optimized transition state geometry of A1 and A2 with radical ˙OOH in water (I) and pentylethanoate (II) and their imaginary frequencies.

Activation energy

and rate constant

k were computed and show in

Table 6. For reaction of

A1 and

A2 with ˙OOH radical on water, computed values of

were 13.07 y 12.26 kcal/mol respectively. With respect to

k, computed values were 1.24 × 10

6 y 4.64 × 10

6 M

−1 s

−1, for

A1 and

A2 respectively. Even though, the presence of the Sn(IV) on

A2 contribute to decrease the

barrier, the rate order of

k remains without change. It can be due to the presence of the metal, which contribute to decrease the activation energy barrier, but do not contribute to modify the width of the barrier during the tunnel effect through the hydrogen transfer.

Table 5.

Activation energy barrier ΔG‡ in kcal/mol and rate constant k in M−1 s−1.

Table 5.

Activation energy barrier ΔG‡ in kcal/mol and rate constant k in M−1 s−1.

| |

A1(I)

|

A1(II)

|

A2(I)

|

A2(II)

|

| |

ΔG‡

|

k |

ΔG‡

|

k |

ΔG‡

|

k |

ΔG‡

|

k |

| ˙OOH |

13.07 |

1.24 × 106

|

18.47 |

4.12 × 103

|

12.26 |

4.64 × 106

|

12.56 |

1.25 × 105

|

In pentylethanoate, for reaction of A1 and A2 were 18.47 and 12.56 kcal/mol respectively, and computed k values were of 4.12 × 103 M−1 s−1 for A1 and 1.25 × 105 M−1 s−1 for A2. In non-polar face, it was shown that the influence of the Sn(IV) contributes to decrease the activation barrier improving the tunnel effect, and increasing the rate order on A2, which means that the presence of the metal contribute to improve its efficiency like scavenger, on this type of systems.

Conclusions

The present studio shows, how the presence of Sn(IV) in an ester derived from the p-cumaric acid can contribute increasing or decreasing its scavenger capability. Due to the great electronegativity of the OH radical, it reacts with the ester in their neutral form with and without the presence of the Sn(IV), as shown in mechanism SET-1. In presence of the metal, is observed that rate constant increases in SET-2 mechanism showing that Sn(IV) contributes to improve the scavenger capability of the anion (deprotonated specie), even the main contribution comes from SET-1 mechanism. Similar behavior can be seen on TH mechanism, where the presence of Sn(IV) does not contribute to improve the scavenger capability. All the above in water. On the other hand, in lipid media, the presence of the Sn(IV) has a great influence in the rate constant order, improving its scavenger capability. Therefore, the presence of Sn(IV) contributes to the ester mainly in lipid media than in polar media.

In the reaction with ˙OOH radical, which is a more selective radical, the presence of Sn(IV) contributes to significantly improve their scavenger capability. In could be due to the presence of the Sn(IV) in the deprotonated form, which could contribute to increase the angle formed between the plane of the aromatic ring and the lone pair of the oxygen [

55,

56], which have shown that increase the electron donor capability in the scavenger activity of an antioxidant. This studio contribute to the study of the development of new drugs focuses on the treatment of deceases where oxidative stress has great influence.