1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) prompted an unprecedented search for diagnostic, prophylactic and therapeutic solutions to control this devastating worldwide pandemic. In response to this call and due to the success of antibodies in preventing and treating diverse infectious diseases [

1,

2] hundreds of small, medium, and large biotech companies as well as academic laboratories focused their efforts on isolating and characterizing anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. As a result, nine therapeutic and/or prophylactic antibodies specific for the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2 received Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and/or European Medicines Agency (EMA) in the first two years of the pandemic [

1].

The EUA antibodies initially demonstrated safety and efficacy in human clinical studies for the original variant of the virus known as Wuhan strain. However, as new immune scape SARS-CoV-2 mutants or Variants of Concern (VOCs) emerged, almost all EUA antibody-based drugs partially lost efficacy or become non-efficacious at all against the VOCs, in particular Omicron (B.1.1.529 lineage) and sub-variants [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This led to a race for quickly development of efficacious therapeutic antibodies of broad neutralization profile to mitigate further spread of SARS-CoV-2 by treating or preventing the infection with new and/or reemergent VOCs including the implementation of creative solutions for the discovery, efficacy studies, toxicology testing and COVID-19 clinical trials.

In a previous work [

5,

6], we reported the isolation of an antibody called IgG-A7 that neutralized Wuhan (WT), B.1.617.2 (Delta) and B.1.1.529 (Omicron) strains in plaque reduction neutralization tests (PRNTs) with authentic viruses. IgG-A7 also protected transgenic K18-hACE2 mice for the hACE-2 from SARS-CoV-2 WT infection at a dose of 5 mg/kg [

6]. In this work we expanded the efficacy studies of IgG-A7 in K18-hACE2 mice infected with Delta and Omicron at doses of 0.5 and 5 mg/kg. Further, we studied the Pharmacokinetic (PK) profile and Toxicity (Tox) of IgG-A7 in CD-1 mice at single doses of 100 and 200 mg/kg, which are 20- and 40-fold higher than the highest efficacious dose of 5 mg/kg. The PK profile of IgG-A7 was consistent with the PK parameters of human IgG1 antibodies when used mouse as a species for PK/Tox studies. Further, IgG-A7 was well tolerated and showed no signs of toxicity. Finally, a Tissue Cross-Reactivity (TCR) study of IgG-A7 with a panel of 13 and 34 relevant mouse and human tissues, respectively, showed no interaction of IgG-A7 with tissues of these species, supporting the PK/Tox results

in vivo and suggesting that this broadly neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 antibody could be well tolerated in humans. The lessons learned by using CD-1 mice as a Tox species in rapidly evolving viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 are discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Ethics

Efficacy studies were performed in groups of male and female K18-hACE2 transgenic mice for the hACE2; B6.CgTg (K18ACE2)2Prlmn/JHEMI strain number 034860, aged 6 to 8 weeks, purchased at Jackson Laboratories, USA. The PK and Tox studies were performed with male and female CD-1 (Crl: CD1 ICR) mice aged 6 to 10 weeks, purchased at the Unidad de Producción de Animales de Laboratorio (UPEAL) of the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana (UAM). All the mice were maintained in quarantine for 1 week before each study and showed no signs of disease or illness upon arrival and before administration of the treatments. During quarantine, efficacy and PK/Tox studies the temperature of the animal facility was maintained at 20–25 °C and humidity of 50-75%, with a minimum of eight air changes per hour. Animals were kept on a 12-h light/dark cycle and had free access to water and food (LabDiet, St. Louis, MO, USA, Cat. No.: 5010).

All the studies were approved by the following committees: (1) The Biosafety Comité del Instituto de Oftalmología Fundación de Asistencia Privada Conde de la Valenciana IAP; (2) Comité Interno para el Cuidado y Uso de Animales de Laboratorio (CICUAL) de la CPA del Servicio Nacional de Sanidad, Inocuidad y Calidad Agroalimentaria (SENASICA); and (3) Comité de Ética e Investigación de la ENCB (CEI-ENCB). The animals were treated, and the experiments performed according to the regulations outlined in the NOM-062-ZOO-1999 [

7].

2.2. Efficacy of IgG-A7 against SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron

SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron viruses were isolated and characterized as described in González-González [

6]. The whole genome sequences of these SARS-CoV-2 strains are deposited in the GenBank with accession numbers: OM060237 (Delta) and ON651664 (Omicron). SARS-CoV-2 was propagated in Vero E6 cells (ATCC, Cat. No.: CRL-1586) for 60 h and frozen for one day to lyse the cells. Supernatants were collected and titrated by plaque assay using Vero E6 cells [

8] to generate working stocks. SARS-CoV-2 stocks were diluted in EMEM to obtain 10

3 PFU/40 µL and 10

5 PFU/40 µL for Delta and Omicron variants, respectively.

The virus was intranasally administered, with mice previously anesthetized with 65 mg/kg of Ketamine and 13 mg/kg of Xylazine. IgG-A7 was given intraperitoneally (IP) in a single dose of 0.5 and 5 mg/kg 24 h post infection to a group of ten mice (five male and five female). Survival, body weight and clinical signs were monitored daily for 14 days for infection with Delta. Clinical signs and body weight were monitored for 7 days for infection with Omicron. Viral load in the lung was determined for RT-PCR to detect SARS-CoV-2 E gene copies on day 14 post-infection. Mice were euthanized when showed irreversible signs of disease. Active virus manipulations, as well as efficacy studies, were performed at BSL2+ facilities, with strict biosafety standards and risk assessment protocols according to the specifications of the WHO Laboratory Biosafety Manual, Four Edition and the Guidance for General Laboratory Safety Practices during the COVID-19 Pandemic of CDC [

9,

10,

11,

12].

2.3. PK Study at High Single Doses

Seventy-two CD-1 mice gender-balanced were divided in two groups and administered with IgGA7 intravenously (IV) at a single bolus dose of 100 or 200 mg/kg of IgGA7 antibody. Mice in the group of 100 mg/kg dose (body weight 22.54 g ± 2.48 g) received 2.25 ± 0.25 mg in 225 µL. For the group of 200 mg/kg (body weight 25.24 g ± 2.30 g), mice received 5.07 ± 0.46 mg in 243 µL. At 1, 2, 4, 8, 24, 48, 96, 144 and 336 hours after administration, four mice (two female and two male) at each of the nine time points were sacrificed and blood samples collected by cardiac puncture into BD Microtainer® Blood Collection Tubes (Cat. No. 365967 BD, USA). All blood samples were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C to obtain serum. Serum samples were stored at -80 °C until analysis.

The concentration of IgG-A7 in serum samples measured by an ELISA adapted from a previously reported assay developed by our group for detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in human serum samples [

13]. Briefly, Nunc Maxisorp 96-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific (MA, USA)) were coated with 1 µg/mL of SARS-CoV-2 RBD overnight at 4 °C. The plates were washed with PBS-0.1% Tween (PBST) and blocked with 3% skim milk in PBS-Tween 0.1% (MPBST) for 1 h at room temperature (RT) and washed with PBST. Serum samples, standard curve of IgG-A7 and negative control (D1.3 anti-lysozyme antibody) were prepared in 1% milk on PBS (MPBS) and 100 µL was added to the plates and incubated 1 h at room temperature (RT). The plates were washed with PBST and IgG-A7 bound was detected with an α-hIgG antibody HRP-conjugated (Abcam Cat. No. AB19312 Cambridge, UK). The assay was revealed with TMB substrate reagent (BD OptEIA, BD Biosciences, San Diego, Ca, USA, Cat. No.: 555214). The reaction was stopped with phosphoric acid 1 M (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA, Cat. No. AB19312) and plates were read at 450 nm with a correction at 570 nm using a SpectraMax M3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, LLC; San José, CA, USA). The method was validated, following the criteria established in M10 ICH Harmonized Guideline [

14] to ensure the reliability of the assay (See

Figure S1 and Table S1 in Supplementary Material).

PK parameters were determined using Phoenix WinNonlin® (version 7.0, Certara USA, Inc., Princeton, NJ) programing an i.v. bolus administration and a single-compartment model. The following PK parameters were calculated: area under the serum concentration-time curve to the last sampling time (AUC0-t), maximum observed serum concentration (Cmax), time of maximum observed serum concentration (Tmax), serum elimination half-life (t½), clearance (Cl), and volume of distribution (Vd).

2.4. Tox Studies

Three groups of 10 CD-1 mice (5 males and 5 females) each were used in the Tox studies. The first group received a 100 mg/kg single i.v. dose of IgG-A7. The second group received a single i.v. dose of 200 mg/kg of IgG-A7 antibody. The third group (control group) did not receive the antibody. The body weight of the animals was monitored daily for 14 days post-administration of IgG-A7. As reference, prior to administration of the antibody the body weight of the mice in the three groups was measured. Fourteen days post-administration, urine (micturition technique) and blood (cardiac puncture) samples were collected for urinalysis, blood chemistry and hematology. Immediately after euthanasia (by carbon dioxide aspiration), mice lung, liver, spleen, heart and kidney were collected and fixed in 10% formaldehyde for histopathological analyses.

All the analyses were performed by MAULAB Veterinary Clinical Pathology Laboratory (Benito Juárez, Mexico City,

https://maulab.com.mx/). For urinalysis, urine pools from three male or three female mice were analyzed. Physical appearance, color and urine density, plus chemical examination (pH, proteins, glucose, ketones, bilirubin, urobilinogen, Blood/Hb, erythrocytes, leukocytes, squamous epithelial cells, transitional epithelial cells and cylinders) and microscopic examination (crystals, bacteria, lipids and others) were determined. For hematology, impedance (EXIGO H400) and wright-stained blood smear were performed to determinate: hematocrit (HCT), hemoglobin (HGB), erythrocytes (RBC), Mean Corpuscular Volume (MVC), Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration (MCHC), platelet (PLK), White Blood Cells (WBC), neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes. Toxicological analysis included blood chemistry of the following parameters: glucose, urea, creatinine, cholesterol, triglycerides, total bilirubin, Alanine Transaminase (ALT), Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST), Alkaline Phosphatase (AP), Creatinine Kinase (CK), total proteins, albumin, globulins, A/G ratio, calcium and phosphorus. Finally, the organs (lung, heart, kidney, spleen and liver) were processed for microscopic examination with sections of the kerosene block in the microtome (5 mm) and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Slide analysis was carried out at magnifications of 10x and 40x.

2.5. TCR in Mouse and Humans

IgG-A7 was conjugated with Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) using the Fluoro Tag™ conjugation kit (Sigma-Aldrich Cat. FITC1-1KT; MO, USA) as described by the manufacturer. Conjugation was performed using 1:1 Antibody: FITC molar ratio and the non-conjugated fluorophore was removed using a 50 kDa centrifugal filter (Merck Mil-lipore; MA, USA) and PBS 1X (Sigma-Aldrich). The quality control of the conjugated IgG-A7-FITC consisted in determining the protein content by densitometry (> 1.8 mg/mL), monomeric content by SEC (> 99%), identity by MS (> 1 FITC molecule per antibody structure), and relative potency determined by the formula [EC50 IgG-A7-FITC / EC50 IgG-A7] *100% in an ELISA plate coated with RBD protein (94 - 96%).

TCR studies were performed by HistologiX Ltd (BioCity, Nottingham, UK). Mouse TCR study was performed on 13 frozen tissues listed in

Table S4 (Supplementary Material) obtained from Tissue Micro-Array (TMA) of FDA standard normal tissues (Amsbio, England, Cat. T6334701-2). On the other hand, the GLP human TCR assay was performed using 34 normal human tissues supplied by Tissue Solutions Ltd (Glaswog, UK) (

Table S5 in Supplementary Material). Human tissues were collected by surgical excision or during post-mortem examinations.

The Tissue Micro Array sections were air-dried and then fixed with Neutral Buffered Phormalin (NBF) for 15 s, whereas the human tissue sections were cut at 5-8 µm, picked up on SuperFrost Plus™ slides (Thermo Scientific; MA, USA) and air dried 60 min at room temperature and stored at -80 °C. The tissue sections were incubated with IgG-A7-FITC at optimal concentration (0.625 µg/mL) in mice study, and at optimal (0.625 µg/mL), supra-optimal (1.25 µg/mL) and sub-optimal (0.078 µg/mL) concentrations in human TCR assay. HEK293T SARS-CoV-2 spike protein stable cell line (GenScript Cat. M00804; NJ, USA) and HEK293T cell line (Takara Cat. 632180; CA, USA) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Visualization and semi-quantitative analysis of Immunohistochemistry (IHC) results were performed by Path Celerate Ltd. (Mill Lane, Goostrey, UK) using light microscopy. Binding of IgG1-A7-FITC to the tissues was detected using a rabbit anti-FITC HRP conjugated (Ancell Cat. 295-040; MN, USA). The isotype IgG1 control was run at a concentration of 0.625 µg/mL and a negative control (primary antibody omitted) was also included. A vimentin ICH assay was used for integrity testing in both assays. Blocking was performed using with normal horse serum and the vimentin antibody (Abcam Cat. Ab92547; MA, USA) was diluted 1:400 (concentration 0.68 μg/mL), followed by quenching of endogenous peroxidases with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol. The intensity of the staining was reported as negative (0), minimal (1), mild (2), moderate (3) and marked (4); whereas the staining distribution was reported as no cells staining (-), very rare cells staining (+), rare cells staining (++) and occasional staining (+++).

3. Results

3.1. IgG-A7 Efficacy against Delta and Omicron SARS-CoV-2 Variants

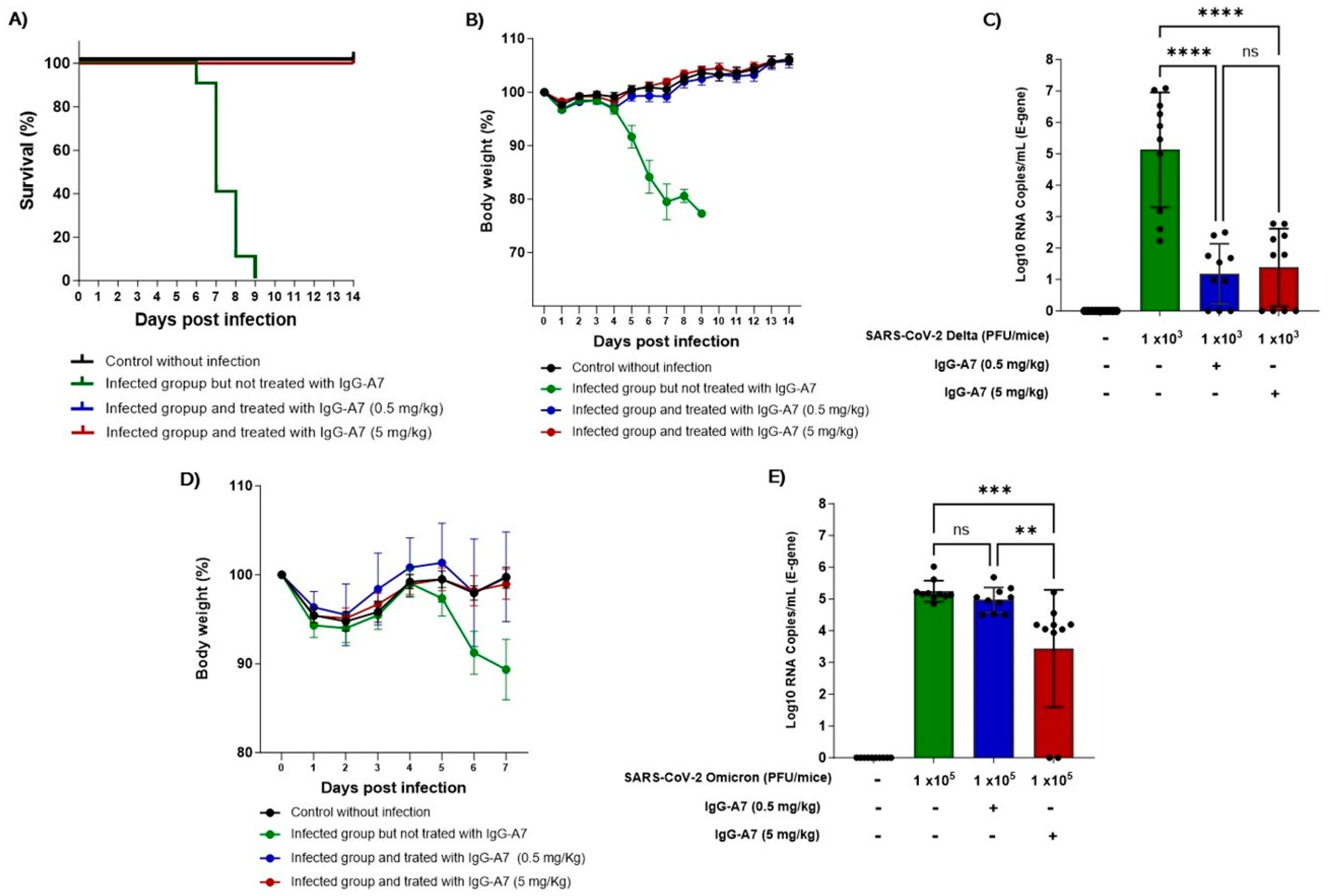

K18-ACE2 mice were infected with SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron and treated with 0.5 and 5 mg/kg of IgG-A7. All the mice infected with Delta and treated with IgG-A7 survived (

Figure 1A) in contrast to infected but untreated mice where all the mice died between day 6 and 9 post-infection. The body weight (

Figure 1B) of untreated animals decreased by 23 % compared to the group without infection, while the groups treated with IgG-A7 did not present weight loss, instead gained around 6% with respect to the weight at the beginning of the study, similarly to the uninfected control group. The viral load in lungs (

Figure 1C) of mice infected with Delta and treated with doses of 0.5 or 5 mg/kg showed a significant and similar decrease when compared with the untreated group (p < 0.0001).

Since Omicron is not lethal in K18-ACE2 mice [

15], the efficacy of IgG-A7 was carried out through the measurement of body weight and viral load in lungs. The body weight in the group infected with Omicron and treated with 0.5 or 5 mg/kg of IgG-A7 was similar to the uninfected control group (

Figure 1D), indicating protection at those doses. In contrast, the body weight of the infected group but without treatment decreased by approximately 1% on day 7 post-infection. The viral load (

Figure 1E) of the group infected with Omicron and treated with 0.5 mg/kg of IgG-A7 was similar to that of the untreated control. However, it decreases significantly in the group treated with 5 mg/kg (p = 0.001), indicating a protective effect at that higher dose. The efficacy of IgG-A7 at 0.5 mg/kg against Delta infection and a ten-fold higher dose (5 mg/kg) against Omicron correlates with the neutralization potency in PRNT results [

6] showing that this antibody has lower NC50 for Omicron (2.93 nM) than for Delta (0.06 nM).

3.2. PK Profiling

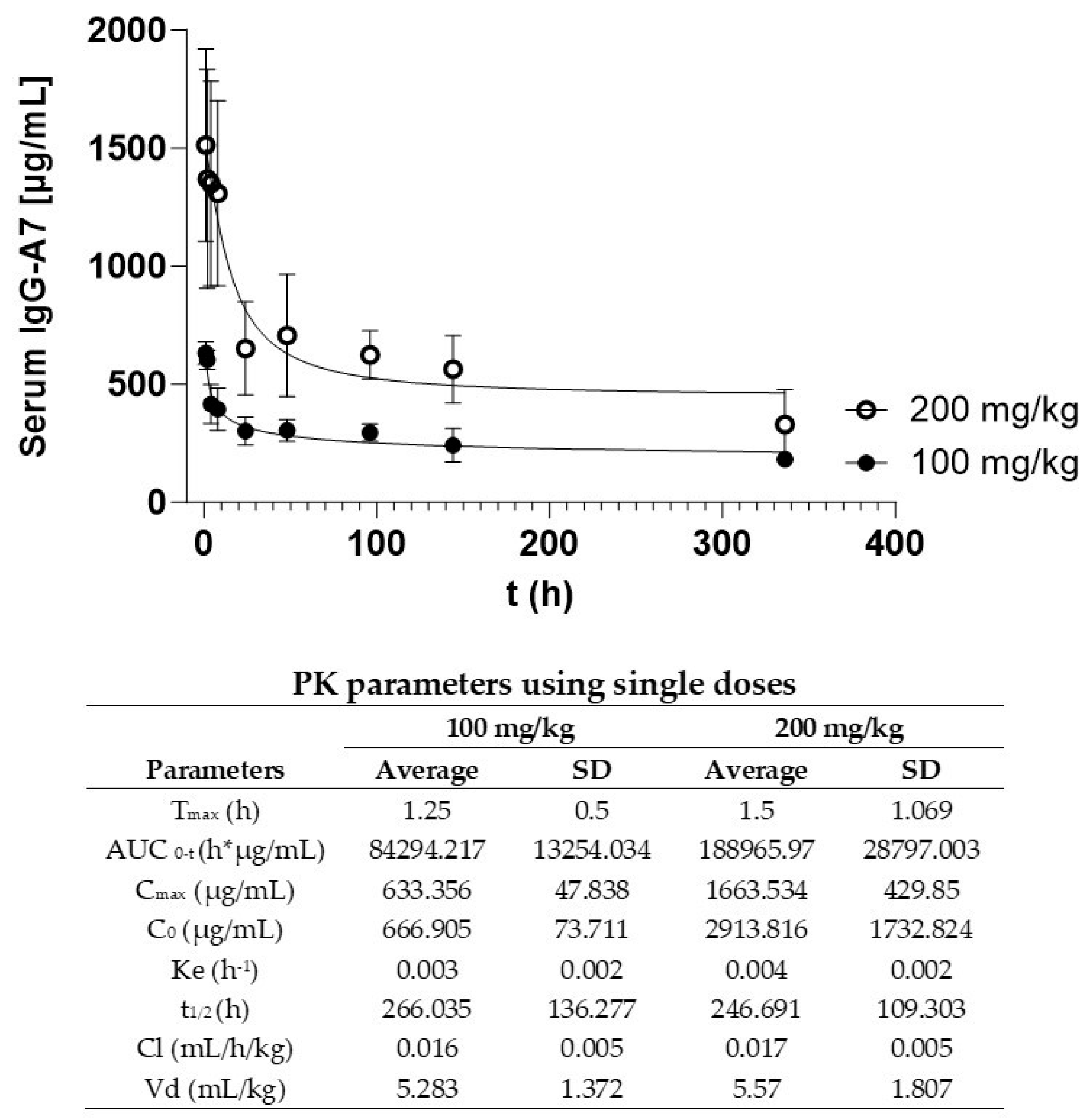

Figure 2 shows the PK curves at single doses of 100 and 200 mg/kg. IgG-A7 concentration in serum as a function of the time follows a typical curve of the decreasing concentration of an IgG1 after a i.v. bolus administration. IgG-A7 was distributed in the body and eliminated from blood following an exponential curve with a fast initial phase followed by a slow elimination. PK parameters are shown in the embedded Table in

Figure 2. The 100 mg/kg dose resulted in a C

max of 633.356 µg/mL and an AUC

0-t of 84,294.217 h*µg/mL, whereas for the 200 mg/kg dose C

max was 1,663.534 µg/mL and AUC

0-t of 188,965.970 h*µg/mL. This difference was consistent with the higher dose of IgG-A7 for the latter. All the other PK parameters were similar for the 100 and 200 mg/kg including half-life (t

1/2) of 266.035 and 246.691 h (11.08 and 10.28 days), k

e of 0.003 and 0.004 h

-1, Cl of 0.016 and 0.017 mL/h/kg and Vd of 5.283 mL/kg and 5.570 mL/kg, respectively. Together, these results indicated that IgG-A7 performed similarly even at 20- or 40-fold the highest efficacy dose of 5 mg/kg.

3.3. Tox Assessment

Potential toxic effects of IgG-A7 antibody administration were assessed via several biochemical and hematological markers listed and described below.

3.3.1. Body Weight

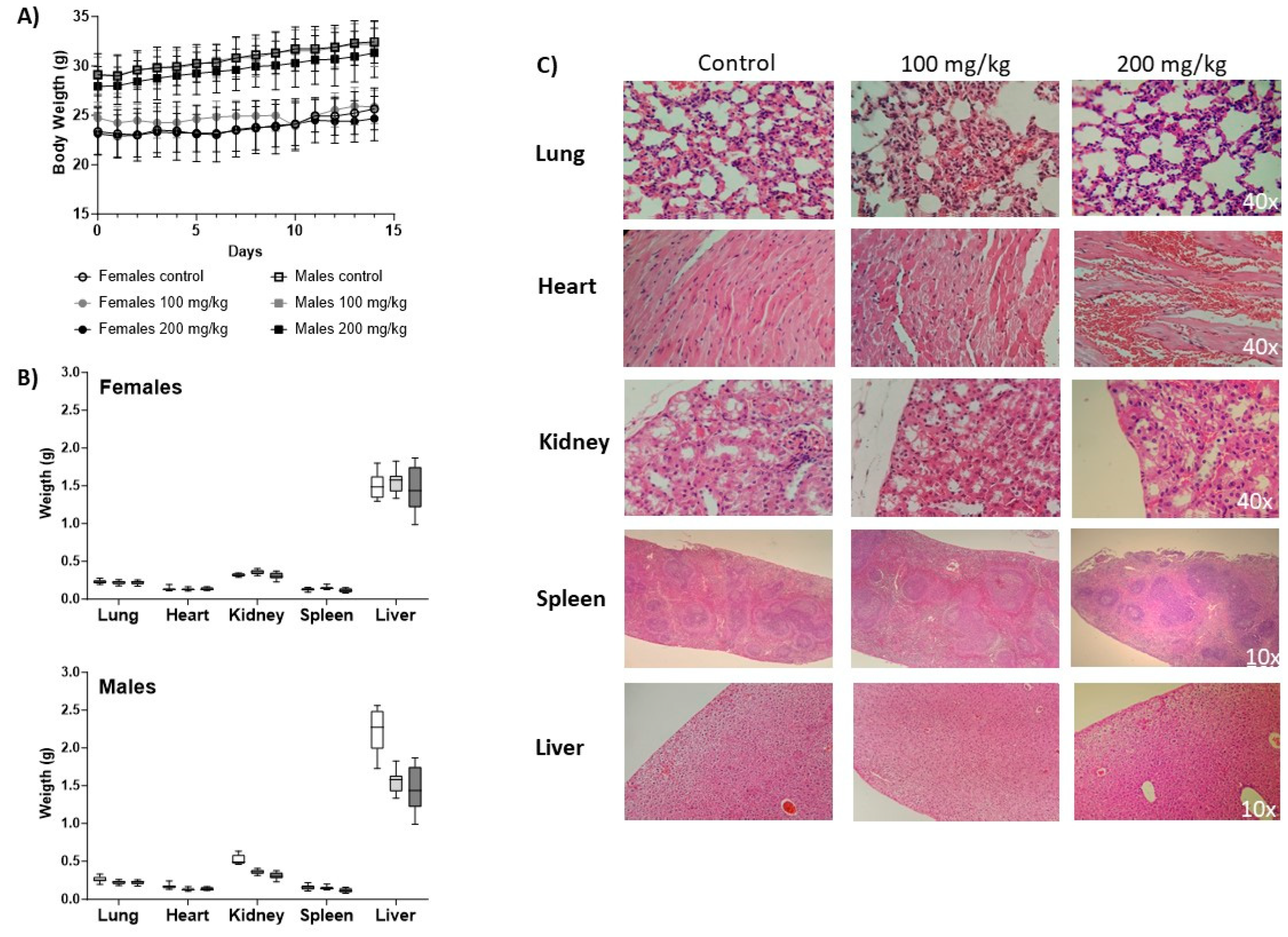

Body weight increased during the study as a sign of IgG-A7 tolerability and no toxicity (

Figure 3A). At time zero, male mice showed a greater body weight than females with an average of 24.72 ± 1.6 g and 29.05 ± 1.86 g, respectively at 100 mg/kg and 23.13 ± 2.11 and 27.93 ± 2.02 for 200 mg /kg. Body weights at the end of the study (day 14) were 25.65 ± 2.11 g for females and 32.20 ± 2.25 g for males (100 mg/kg) whereas for females was 24.66 ± 2.27 and 31.33 ± 2.5 for males at 200 mg /kg. During the time of the study, neither morbidity nor mortality was observed.

3.3.2. Urinalysis

Urine analysis results showed that both the control group and the 100 and 200 mg/kg groups had a cloudy urine appearance with a yellow color, a density greater than ~1.050 and pH of 6.5. males had ~1 g/L protein in all three groups and females had ~0.3 g/L, no glucose, no crystals, no bacterium, no ketones and no Hb blood in all urine determinations, all mice have normal bilirubin and normal urobilinogen levels.

3.3.3. Hematology

The results of the parameters measured for sera from untreated and IgG-A7 antibody-treated animals are shown in

Table S2 of Supplementary Material. No changes in the samples were found compared to reference values, control group and groups that were administered with 100 and 200 mg/kg of the antibody.

3.3.4. Blood chemistry

The parameters of the blood tests (

Table S3) showed significant changes in total proteins and globulins in females and higher levels of calcium and phosphorus in both sexes. Higher levels with respect to the reference value in males and females in both doses, however, did not vary between the control groups and those administered with the antibody. No changes were shown in the other parameters measured between control and IgG-A7 at two different doses.

3.3.5. Histopathology

After necropsy, the organ weight showed no statistically significant differences when compared to the control group (

Figure 3B).

Figure 3C shows representative micrographs of the histopathological analysis of tissue sections of lung, heart, kidney, spleen and liver collected from untreated mice and treated with IgG-A7 at 100 and 200 mg/kg. Lungs showed red coloration, without deformations in the alveoli. Hearts showed presence of cardiomyocytes with normal nuclei located in the center of the papillary muscle and in the interventricular septum. In kidneys, no alterations in the normal structures of the proximal and distal tubules were observed in tissues from mice treated with IgG-A7. In spleen tissue samples, no deformities are observed in its main structures white pulp, red pulp and stroma. Finally, livers had a normal brown coloration, presence of vacuolization (microvacuoles) with clear and round shapes.

3.4. TCR in Mouse and Human

Preclinical safety assays of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG1-A7 antibody were further investigated by evaluating its cross-reaction to mice and human tissues. To this end, 13 and 34 relevant mice and human tissues were evaluated as recommended by FDA and EMA [

16]. Both assays employed HEK293T cells as negative control and HEK293T cells that stably express SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein as negative controls. As shown in

Tables S4 and S5 of Supplementary Material the positive control exhibited moderate intensity (3 within a scale from 0 – 3) and a distribution of rare cells staining (++ within a scale from – to +++). No signals were detected in negative control. Vimentin test evinced that all the tissues employed in both assays matched the integrity criteria. In the mouse TCR assay the IgG1-A7 antibody (0.625 µg/mL) did not cross-reacted with none of the evaluated tissues. Likewise, the GLP human TCR assay showed that IgG1-A7 does not bind the 36 relevant human tissues at optimal (0.625 µg/mL) supra-optimal (1.25 µg/mL) or sub-optimal (0.078 µg/mL) concentrations.

4. Discussion

In the previous sections we reported that IgG-A7 protected K18hACE2 mice from SARS-CoV-2 against Delta and Omicron variants at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg. IgG-A7 protection against Delta correlated with decreased viral load in mice lugs suggesting that its protective effect was directly related to a decrease of SARS-CoV-2 infection. For Omicron, the 0.5 mg/kg did not show a significant decrease of the viral load in mice lungs, in contrast to the 5 mg/kg dose, which showed a significant difference with respect to the non-infected control group and the group treated with 0.5 mg/kg, suggesting that 5 mg/kg is more efficacious against Omicron than 0.5 mg/kg. Together with the previous work [

6], indicating that IgG-A7 protect at 5 mg/kg against the Wuhan, demonstrate that IgG-A7 is a broadly and highly effective antibody in preventing mortality in K18hACE2 transgenic mice at a dose as low as 5 mg/kg.

Having demonstrated the broad efficacy of IgG-A7 with diverse variants of SARS-CoV-2, we evaluated its PK profile in CD-1 mice. Mice, due to low costs, rapid reproductive cycle, and ease handling, have been used in several PK/Tox studies [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. At doses of IgG-A7 20 and 40 times higher than the protective dose of 5 mg/kg, IgG-A7 PK parameters were proportional to the dose, with similar serum elimination half-life of ~10.5 days at both high doses, consistent with PK studies in CD-1 mice of fully human or humanized IgG1 antibodies at diverse doses [

23]. For instance, a half-life of ~9.5 days has been reported for an anti-CEA IgG1 antibody and Fc fusion proteins in CD-1 mice [

24]. Another report using the humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody cantuzumab in CD-1 mice resulted in a half-life of ~6.5 days [

22]. Evaluation of an anti-CD30 antibody in other mice strains such as Balb/c, Nude mice and SCID, have also given half-life values in the range of IgG-A7, i.e., 7.1±5 days, 10±10 days of 16±8 days, respectively [

25]. On the other hand, a study of COVID-HIGIV [

23], a polyclonal purified human IgG product manufactured with the immunoglobulin fraction of plasma from SARS-CoV-2 convalescent patients, at a single dose of 400 mg/kg reported a similar half-life of 161 hours (6.7 days) in healthy wild-type C57Bl/6 mice and SARS-CoV-2 infected K18hACE2 transgenic mice. These results of t

½ besides the low values for Vd depicts a long-lasting behavior of the IgG-A7 into the central compartment (blood) with succinct distribution along other tissues.

We further evaluated the potential toxicity of IgG-A7 in the CD-1 mouse model in urine, blood, and tissue samples. At doses of 100 and 200 mg/kg no significant differences were observed in treated and untreated animals, indicating that IgG-A7 did not induce immune or inflammatory responses. Sera biochemical parameters, such as total proteins, globulins, calcium and phosphorus, showed differences in female and male mice with respect to reference values [

26,

27], which could be associated to possible renal damage [

28,

29]. However, when compared to the values in the control groups no statistically significant differences were found. Also, no alterations were found in urea and creatinine values.

All organs were also analyzed for alterations in their morphology or leukocyte infiltration. Although some tissues showed a low degree of degeneration and necrosis, this alteration is attributable to the previous cardiac puncture and total blood loss before necropsy. However, when analyzing the kidney, there are no changes in weight and no structural alterations in the tissue are observed. Therefore, the changes in total proteins, globulins, calcium and phosphorus seem to be related to the administration of high concentrations of a protein (IgG-A7) and its elimination via the kidney, but not to an evident toxic impact or histological damage in the kidney.

Finally, a mouse and human TCR study was conducted with tissues recommended by FDA and EMA [

30,

31,

32]. The mouse TCR study showed that the IgG1-A7 does not bind the tested tissues, supporting the PK profile in CD-1 mice where elimination of the antibody corresponds to a typical PK profile of a human IgG1 in mouse with no accumulation of the antibody in the mice organs nor apparent toxicity. The TCR study in human tissues, on the other hand, was performed under a GLP system and suggested that IgG-A7 is unlikely to have adverse effects in humans due to no cross-recognition with human proteins. The latter results provide support to subsequent studies in humans, serving as a bridge between the mouse studies and eventual testing of IgG-A7 in clinical phase 1 studies. Worth mentioning is that, within the panel of human tissues, uterus (cervix, endometrium) and placenta were evaluated, which further supports the administration of IgG1-A7 in pregnant women according to the provisions for obtaining an EUA of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

It should be emphasized that non-human primates (NHPs) have been the primary approach for PK/Tox studies as preamble to - and in support of - studies in humans. However, the urgency to develop efficacious antibodies to mitigate the devastating impact of COVID-19 pandemic led to a high demand and a shortage of NHPs [

5]. This, compounded with increasing ethical concerns [

33] on the use of NHPs in preclinical studies, has required relatively inexpensive preclinical models capable of providing meaningful information, as quickly as possible, to proceed with human clinical trials as alternative to NHPs. Mice, which are low-cost, have a fast-reproductive cycle, are easy-to-handle, and demand low amounts of proteins in efficacy and PK/Tox studies, have been providing useful information in numerous efficacy and PK/Tox studies [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. The information generated in this report using the CD-1 as a PK/Tox model, complemented with the TCR study in mouse and human tissues, could thus be of relevance to future emerging viral infections or even non-infectious diseases such as immunological disorders or cancer where a fast response is needed to effectively meet unmet medical needs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1. Calibration curve of ELISA; Table S1. ELISA performance validation parameters; Table S2. Hematology summary in CD1-Wt mice, 14 days after i.v. treatment with IgG-A7 antibody; Table S3. Blood chemistry summary in CD1-Wt mice, 14 days after i.v. treatment with IgG-A7 antibody; Table S4. Microscopic evaluation of the mice tissues and Table S5. Microscopic evaluation of the human tissues.

Author Contributions

S.G.P., E.G.-G. and G.C.-U. contributed to the planning and execution of most of the experimental strategies of this work, as well as analysis and discussion of the results, preparation of the figures, and manuscript writing. E.G.-G. and S.G.P. participated in validation method design and supervision. F.R.-V. and C.G.-G. participated in the method validation execution and in the quantitation of antibody in serum samples and data analysis. L.V.-C. contributed with analysis and discussion of TCR data, G.M.-J. and D.B. contributed with PK parameters analysis and all authors contributed to the results and discussion, and manuscript review. S.M.P.-T. and J.C.A. devised the concept of the manuscript and contributed to the overall direction of the work, discussion of the results and general writing, preparation of the figures, and manuscript review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a grant from AMEXID—Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores Fondo México-Chile (CH05-Anticuerpos neutralizantes para SARS-CoV-2 MEX-CHI). Part of the work was conducted with equipment from the “Laboratorios Nacional para Servicios Especializados de Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación (I + D + I) para Farmoquímicos y Biotecnológicos,” LANSEIDIFarBiotec-CONACyT.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the research ethics committee (CEI) of the ENCB (approval number ENCB/CICUAL/014/2023), The Biosafety Comité del Instituto de Oftalmología Fundación de Asistencia Privada Conde de la Valenciana IAP (approval number: CB-010-2022), Comité Interno para el Cuidado y Uso de Animales de Laboratorio (CICUAL) de la CPA del Servicio Nacional de Sanidad, Inocuidad y Calidad Agroalimentaria (SENASICA).

Data Availability Statement

All the data obtained during this study is included in the manuscript. Additional information could be provided by the authors upon a reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

First: we would like to thank to Juana Salinas-Trujano and Alexis G Suárez-Gómez for the maintenance and production of viral stocks for efficacy assays. To Luis Valencia-Flores, Omar Rojas-Gutiérrez, I Mendoza-Salazar for technical assistance in handling the mice during the efficacy test and Karina López-Olvera for her contribution in histopathology description from the reports generated by MAULAB. To Kuauhtémok Domínguez and Samantha Macias-Palacios for recompilation and organization of raw data. Also, we would like to thank Blanca J. Sánchez-Morales and the Quality Control Team for their support during the execution of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

J.C.A. is founder and CEO of GlobalBio, Inc. and has a commercial interest in the antibodies described in this work. The authenticity of the experimental results and objectivity of the discussion is not affected by this apparent conflict of interest.

References

- Almagro, J.C.; Mellado-Sanchez, G.; Pedraza-Escalona, M.; Perez-Tapia, S.M. Evolution of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Therapeutic Antibodies. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 9763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takashita, E.; Kinoshita, N.; Yamayoshi, S.; Sakai-Tagawa, Y.; Fujisaki, S.; Ito, M.; Iwatsuki-Horimoto, K.; Halfmann, P.; Watanabe, S.; Maeda, K.; et al. Efficacy of Antiviral Agents against the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Subvariant BA.2. New England Journal of Medicine 2022, 386, 1475–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanBlargan, L.A.; Errico, J.M.; Halfmann, P.J.; Zost, S.J.; Crowe, J.E.; Purcell, L.A.; Kawaoka, Y.; Corti, D.; Fremont, D.H.; Diamond, M.S. An infectious SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 Omicron virus escapes neutralization by therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Nat Med 2022, 28, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.D.; Sharma, A.; Lee, H.J.; Yadav, D.K. SARS-CoV-2: Recent Variants and Clinical Efficacy of Antibody-Based Therapy. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 839170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-Salazar, I.; Gómez-Castellano, K.M.; González-González, E.; Gamboa-Suasnavart, R.; Rodríguez-Luna, S.D.; Santiago-Casas, G.; Cortés-Paniagua, M.I.; Pérez-Tapia, S.M.; Almagro, J.C. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Antibodies Isolated from a SARS-CoV-2 Delta Semi-Immune Phage Display Library. Antibodies 2022, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Gonzalez, E.; Carballo-Uicab, G.; Salinas-Trujano, J.; Cortes-Paniagua, M.I.; Vazquez-Leyva, S.; Vallejo-Castillo, L.; Mendoza-Salazar, I.; Gomez-Castellano, K.; Perez-Tapia, S.M.; Almagro, J.C. In Vitro and In Vivo Characterization of a Broadly Neutralizing Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Isolated from a Semi-Immune Phage Display Library. Antibodies 2022, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norma Oficial Mexicana De La Federación-NOM-062-ZOO-1999, Especificaciones técnicas para la producción, cuidado y uso de los animales de laboratorio. D Of Fed. 2001;477.

- Bewley, K.R.; Coombes, N.S.; Gagnon, L.; McInroy, L.; Baker, N.; Shaik, I.; St-Jean, J.R.; St-Amant, N.; Buttigieg, K.R.; Humphries, H.E.; et al. Quantification of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody by wild-type plaque reduction neutralization, microneutralization and pseudotyped virus neutralization assays. Nat Protoc 2021, 16, 3114–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories—6th Edition. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/labs/pdf/SF__19_308133-A_BMBL6_00-BOOK-WEB-final-3.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- Laboratory biosafety manual, 4th edition. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240011311 (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- CDC. Labs. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published 11 February 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/lab-safety-practices.html (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Guidance for BSL2+ COVID laboratories. Available online: https://research.cuanschutz.edu/docs/librariesprovider148/ehs_documents/default-library/guidance-for-bsl2-covid-laboratories-anschutz.pdf?sfvrsn=79c7e4b9_0 (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Camacho-Sandoval, R.; Nieto-Patlán, A.; Carballo-Uicab, G.; Montes-Luna, A.; Jiménez-Martínez, M.C.; Vallejo-Castillo, L.; González-González, E.; Arrieta-Oliva, H.I.; Gómez-Castellano, K.; Guzmán-Bringas, O.U.; et al. Development and Evaluation of a Set of Spike and Receptor Binding Domain-Based Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays for SARS-CoV-2 Serological Testing. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICH Harmonised Guideline M10 Bioanalytical Method Validation and Study Sample Analysis to be implemented by PQT/MED. In WHO—Prequalification of Medical Products (IVDs, Medicines, Vaccines and Immunization Devices, Vector Control); 2023.

- Halfmann, P.J.; Iida, S.; Iwatsuki-Horimoto, K.; Maemura, T.; Kiso, M.; Scheaffer, S.M.; Darling, T.L.; Joshi, A.; Loeber, S.; Singh, G.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron virus causes attenuated disease in mice and hamsters. Nature 2022, 603, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.W.; Halpern, W.G.; Johnson, C.W.; Rojko, J.L.; MacLachlan, T.K.; Chan, C.M.; Galbreath, E.J.; Ndifor, A.M.; Blanset, D.L.; Polack, E.; et al. Use of tissue cross-reactivity studies in the development of antibody-based biopharmaceuticals: History, experience, methodology, and future directions. Toxicol Pathol 2010, 38, 1138–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.R.; Yang, Z.; Dong, H.; Camuso, A.; McGlinchey, K.; Fager, K.; Flefleh, C.; Kan, D.; Inigo, I.; Castaneda, S.; et al. Correlation of pharmacokinetics with the antitumor activity of Cetuximab in nude mice bearing the GEO human colon carcinoma xenograft. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2005, 56, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Kim, D.; Son, E.; Yoo, S.J.; Sa, J.K.; Shin, Y.J.; Yoon, Y.; Nam, D.H. Pharmacokinetics, Biodistribution, and Toxicity Evaluation of Anti-SEMA3A (F11) in In Vivo Models. Anticancer Res 2018, 38, 2803–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandker, G.G.W.; Adema, G.; Molkenboer-Kuenen, J.; Wierstra, P.; Bussink, J.; Heskamp, S.; Aarntzen, E. PD-L1 Antibody Pharmacokinetics and Tumor Targeting in Mouse Models for Infectious Diseases. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 837370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, R.; Bumbaca, D.; Pastuskovas, C.V.; Boswell, C.A.; West, D.; Cowan, K.J.; Chiu, H.; Mcbride, J.; Johnson, C.; Xin, Y.; et al. Preclinical pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, tissue distribution, and tumor penetration of anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody, an immune checkpoint inhibitor. mAbs 2016, 8, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntosh, D.P.; Cooke, R.J.; McLachlan, A.J.; Daley-Yates, P.T.; Rowland, M. Pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of cisplatin and conjugates of cisplatin with carboxymethyldextran and A5B7 monoclonal antibody in CD1 mice. J Pharm Sci 1997, 86, 1478–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Audette, C.; Hoffee, M.; Lambert, J.M.; Blättler, W.A. Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of the antitumor immunoconjugate, cantuzumab mertansine (huC242-DM1), and its two components in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2004, 308, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Doyle-Eisele, M.; Revelli, D.; Carnelley, T.; Barker, D.; Kodihalli, S. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Effects of Polyclonal Antibodies against SARS-CoV2 in Mice. Viruses 2022, 15, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unverdorben, F.; Richter, F.; Hutt, M.; Seifert, O.; Malinge, P.; Fischer, N.; Kontermann, R.E. Pharmacokinetic properties of IgG and various Fc fusion proteins in mice. mAbs 2016, 8, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ulrich, M.L.; Shih, V.F.; Cochran, J.H.; Hunter, J.H.; Westendorf, L.; Neale, J.; Benjamin, D.R. Mouse Strains Influence Clearance and Efficacy of Antibody and Antibody-Drug Conjugate Via Fc-FcγR Interaction. Mol Cancer Ther 2019, 18, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

The Clinical Chemistry of Laboratory Animals, 3rd ed.; Travlos, D.M.K.G.S., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2017; p. 1162. [Google Scholar]

- CD-1® IGS Mouse. Available online: https://www.criver.com/products-services/find-model/cd-1r-igs-mouse?region=3616 (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- DiBartola, S.P.; Willard, M.D. Chapter 7—Disorders of Phosphorus: Hypophosphatemia and Hyperphosphatemia. In Fluid, Electrolyte, and Acid-Base Disorders in Small Animal Practice (Third Edition); Dibartola, S.P., Ed.; W.B. Saunders: Saint Louis, 2006; pp. 195–209. [Google Scholar]

- Moe, S.M. Disorders Involving Calcium, Phosphorus, and Magnesium. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice 2008, 35, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Development of Monoclonal Antibody Products Targeting SARS-CoV-2, Including Addressing the Impact of Emerging Variants, During the COVID 19 Public Health Emergency; U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- EMA. Development, production, characterisation and specifications for monoclonal antibodies related products—Scientific guideline; European Medicines Agency; p. 2018.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Points to Consider in the Manufacture and Testing of Monoclonal Antibody Products for Human Use; U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, C.; Gaspar, A.; Knight, A.; Vicente, L. Ethical and Scientific Pitfalls Concerning Laboratory Research with Non-Human Primates, and Possible Solutions. Animals 2018, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).