Submitted:

31 July 2023

Posted:

01 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient population and medical chart review

2.2. HDMTX administration and monitoring

2.3. Population pharmacokinetics analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Campbell, M. ALL IC-BFM 2009 – A randomized trial of the I-BFM-SG for the management of childhood non-b acute lymphoblastic leukemia. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pillon, M.; Arico, M.; Mussolin, L.; Carraro, E.; Conter, V.; Sala, A.; Buffardi, S.; Garaventa, A.; D'Angelo, P.; Lo Nigro, L.; et al. Long-term results of the AIEOP LNH-97 protocol for childhood lymphoblastic lymphoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015, 62, 1388–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ALCL 99 International protocol for the treatment of childhood anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Available online: https://www.skion.nl/workspace/uploads/alcl-99.pdf. 2000. (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, L.; Chen, X.; Zhao, L.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Mei, S. A systematic review of population pharmacokinetic models of methotrexate. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 2022, 47, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, S.C.; McCormick, J.; Pui, C.H.; Buddington, R.K.; Harvey, R.D. Preventing and managing toxicities of high-dose methotrexate. The Oncologist 2016, 21, 1471–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treon, S.P.; Chabner, B.A. Concepts in use of high-dose methotrexate therapy. Clin Chem 1996, 42, 1322–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nader, A.; Zahran, N.; Alshammaa, A.; Altaweel, H.; Kassem, N.; Wilby, K.J. Population pharmacokinetics of intravenous methotrexate in patients with hematological malignancies: utilization of routine clinical monitoring parameters. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 2017, 42, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skoric, B.; Kuzmanovic, M.; Jovanovic, M.; Miljkovic, B.; Micic, D.; Jovic, M.; Jovanovic, A.; Vucicevic, K. Methotrexate concentrations and associated variability factors in high dose therapy of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mould, D.R.; Upton, R.N. Basic concepts in population modeling, simulation, and model-based drug development-part 2: introduction to pharmacokinetic modeling methods. CPT: PSP 2013, 2, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roganović, M.; Homšek, A.; Jovanović, M.; Topić Vučenović, V.; M., Ć.; Miljković, B.; Vučićević, K. Concept and utility of population pharmacokinetic and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic models in drug development and clinical practice Arh farm 2021, 71, 336–353. [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Li, X.; Jiang, X.; Yu, K.; Lin, S.; Zhao, Z. Population pharmacokinetics of high-dose methotrexate in patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. J Pharm Sci 2018, 107, 1454–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faltaos, D.W.; Hulot, J.S.; Urien, S.; Morel, V.; Kaloshi, G.; Fernandez, C.; Xuan k, H.; Leblond, V.; Lechat, P. Population pharmacokinetic study of methotrexate in patients with lymphoid malignancy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2006, 58, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.O.; Gu, H.Y.; Xu, X.Q.; Yan, C.; Yang, X.Y.; Yan, D. Population pharmacokinetics of high-dose methotrexate in Chinese pediatric patients with medulloblastoma. Biopharm Drug Dispos 2020, 41, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuhara, K.; Ikawa, K.; Morikawa, N.; Kumagai, K. Population pharmacokinetics of high-dose methotrexate in Japanese adult patients with malignancies: a concurrent analysis of the serum and urine concentration data. J Clin Pharm Ther 2008, 33, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panetta, J.C.; Roberts, J.K.; Huang, J.; Lin, T.; Daryani, V.M.; Harstead, K.E.; Patel, Y.T.; Onar-Thomas, A.; Campagne, O.; Ward, D.A.; et al. Pharmacokinetic basis for dosing high-dose methotrexate in infants and young children with malignant brain tumours. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2020, 86, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, M.P.; Debacker, K.C.; Derstine, B.; Sullivan, J.; Su, G.L.; Wang, S.C. Comparison of body size, morphomics, and kidney function as covariates of high-dose methotrexate clearance in obese adults with primary central nervous system lymphoma. Pharmacother 2020, 40, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, Z.L.; Mizuno, T.; Punt, N.C.; Baskaran, B.; Navarro Sainz, A.; Shuman, W.; Felicelli, N.; Vinks, A.A.; Heldrup, J.; Ramsey, L.B. MTXPK.org: a clinical decision support tool evaluating high-dose methotrexate pharmacokinetics to inform post-infusion care and use of glucarpidase. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2020, 108, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, A.M.; Hill, N.; Perisoglou, M.; Whelan, J.; Karlsson, M.O.; Standing, J.F. A population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model of methotrexate and mucositis scores in osteosarcoma. Ther Drug Monit 2011, 33, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakatsu, S.; Nikanjam, M.; Lin, M.; Le, S.; Saunders, I.; Kuo, D.J.; Capparelli, E.V. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of high-dose methotrexate in pediatric and adult oncology patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2019, 84, 1339–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, P.; Skarby, T.; Heldrup, J.; Schroder, H.; Hoglund, P. High dose methotrexate treatment in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia may be optimised by a weight-based dose calculation. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011, 57, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, K.H.; Chu, H.M.; Fong, P.S.; Cheng, W.T.F.; Lam, T.N. Population pharmacokinetic study and individual dose adjustments of high-dose methotrexate in Chinese pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia or osteosarcoma. J Clin Pharmacol 2019, 59, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.D.; Panetta, J.C.; Onar-Thomas, A.; Reddick, W.E.; Patay, Z.; Qaddoumi, I.; Broniscer, A.; Robinson, G.; Boop, F.A.; Klimo, P., Jr.; et al. Delayed methotrexate excretion in infants and young children with primary central nervous system tumors and postoperative fluid collections. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2015, 75, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotnik, B.F.; Grabnar, I.; Grabar, P.B.; Dolzan, V.; Jazbec, J. Association of genetic polymorphism in the folate metabolic pathway with methotrexate pharmacokinetics and toxicity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and malignant lymphoma. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2011, 67, 993–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leveque, D.; Santucci, R.; Gourieux, B.; Herbrecht, R. Pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions with methotrexate in oncology. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2011, 4, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupuis, C.; Mercier, C.; Yang, C.; Monjanel-Mouterde, S.; Ciccolini, J.; Fanciullino, R.; Pourroy, B.; Deville, J.L.; Duffaud, F.; Bagarry-Liegey, D.; et al. High-dose methotrexate in adults with osteosarcoma: a population pharmacokinetics study and validation of a new limited sampling strategy. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2008, 19, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeckmann, A.J.; Sheiner, L.B.; Beal, S.L. NONMEM Users Guides. Ellicott City, MD: Icon Development Solutions. 1989-2011.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria; Available online: http://www.R-project.org.

- Anderson, B.J.; Holford, N.H. Mechanism-based concepts of size and maturity in pharmacokinetics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2008, 48, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexi-Interact®. Lexicomp Online®. Wolters Kluwer Clinical Drug Information. Available online: https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/login. (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Hooker, A.C.; Staatz, C.E.; Karlsson, M.O. Conditional weighted residuals (CWRES): a model diagnostic for the FOCE method. Pharm Res 2007, 24, 2187–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, M.O.; Savic, R.M. Diagnosing model diagnostics. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007, 82, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parke, J.; Holford, N.H.; Charles, B.G. A procedure for generating bootstrap samples for the validation of nonlinear mixed-effects population models. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 1999, 59, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrand, M.; Hooker, A.C.; Wallin, J.E.; Karlsson, M.O. Prediction-corrected visual predictive checks for diagnosing nonlinear mixed-effects models. AAPS J 2011, 13, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beechinor, R.J.; Thompson, P.A.; Hwang, M.F.; Vargo, R.C.; Bomgaars, L.R.; Gerhart, J.G.; Dreyer, Z.E.; Gonzalez, D. The population pharmacokinetics of high-dose methotrexate in infants with acute lymphoblastic leukemia highlight the need for bedside individualized dose adjustment: a report from the children's oncology group. Clin Pharmacokinet 2019, 58, 899–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, M.; Vučićević, K. Pediatric pharmacokinetic considerations and implications for drug dosing. Arh farm 2020, 72, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhs, H.; Becker, A.; Drescher, A.; Panetta, J.C.; Pui, C.H.; Relling, M.V.; Jaehde, U. Population PK/PD model of homocysteine concentrations after high-dose methotrexate treatment in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. PloS One 2012, 7, e46015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Beaumais, T.A.; Jacqz-Aigrain, E. Intracellular disposition of methotrexate in acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. Curr Drug Metab 2012, 13, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, Y.; Qiang, F.; Peng, L.; Zhu, Z. High dose methotrexate population pharmacokinetics and Bayesian estimation in patients with lymphoid malignancy. Biopharm Drug Dispos 2009, 30, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic (units) | ALL (n=25) | NHL (n=25) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD (range) | ||

| Age (years) | 8.58 ± 5.27 (1 – 18) | 10.04 ± 3.74 (4 – 18) |

| BSA (m2) | 1.089 ± 0.41 (0.49 – 1.73) | 1.23 ± 0.41 (0.61 – 2.22) |

| Body weight (kg) | 33.03 ± 16.97 (10.3 – 60.1) | 39.27 ± 20.62 (13.9 – 91) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 17.33 ± 2.56 (12.83 – 23.09) | 17.89 ± 3.88 (11.72 – 27.93) |

| SECR (μmol/L) | 46.42 ± 16.62 (14 – 100) | 51.12 ± 13.44 (31 – 75) |

| ALT (U/L) | 37.48 ± 29.74 (10 – 119) | 51.31 ± 35.86 (11 – 129) |

| AST (U/L) | 33.35 ± 20.48 (11 – 114) | 38.37 ± 34.16 (10 – 158) |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 9.98 ± 7.12 (3.1 – 29.5) | 10.15 ± 4.72 (3 – 21) |

| Erythrocyte (1012/L) | 3.63 ± 0.44 (2.71 – 4.72) | 4.37 ± 0.68 (3.06 – 5.63) |

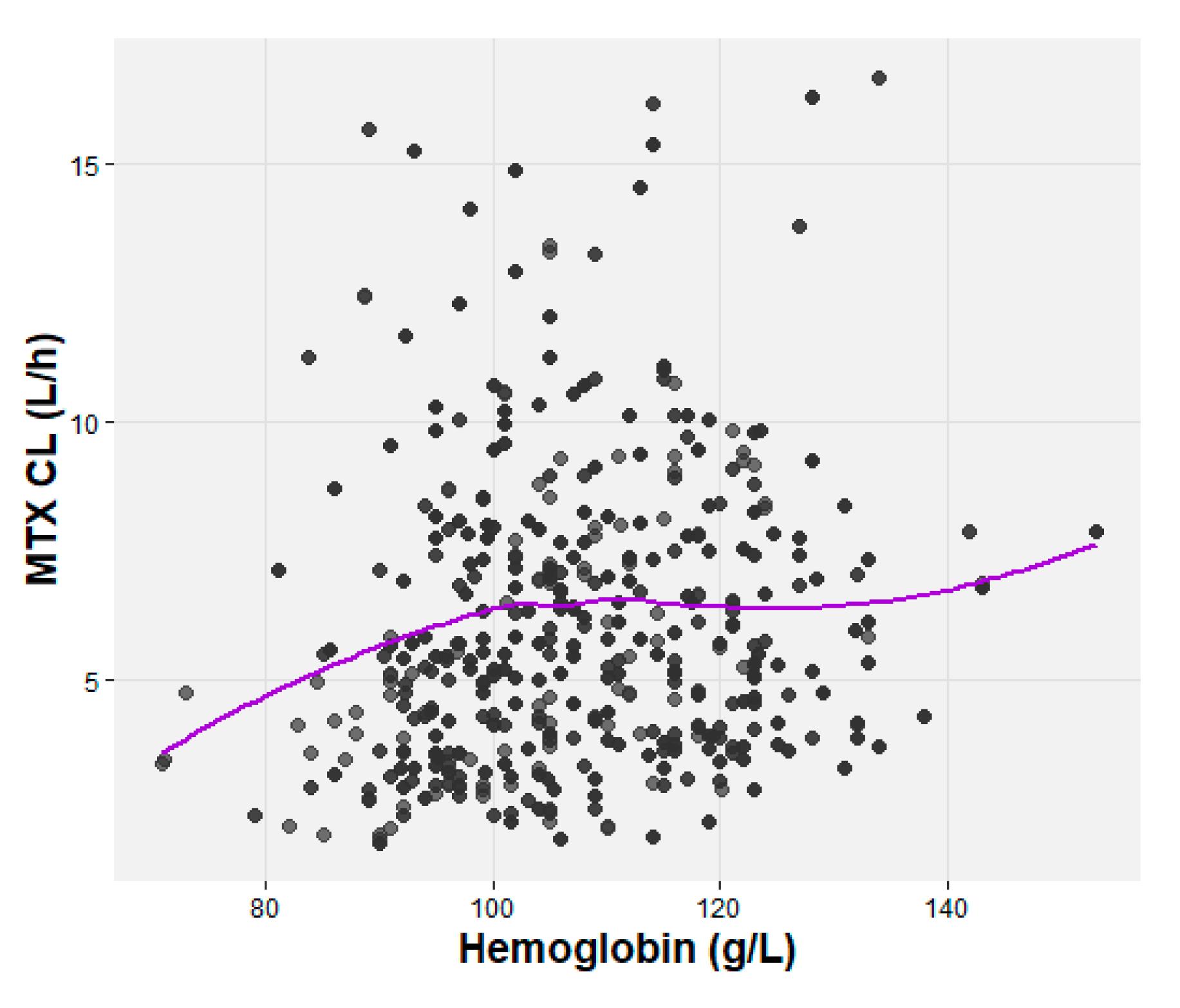

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 106.66 ± 12.90 (81 – 132) | 115.80 ± 16.26 (92 – 153) |

| Hematocrit, HCT (%) | 30.56 ± 3.98 (23.7 – 39.7) | 33.98 ± 5.00 (26.35 – 46.20) |

| Original dataset | Bootstrap datasets | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimated value | Median | 95% CI |

| θCL (L/h/70 kg) | 11 | 10.96 | 10.02 - 12.12 |

| θV1 (L/70 kg) | 46.5 | 46.00 | 39.00 - 52.94 |

| θV2 (L/70 kg) | 16.4 | 15.98 | 6.535 - 20.51 |

| θQ (L/h/70 kg) | 0.168 | 0.164 | 0.124 - 0.201 |

| θSECR | -0.0155 | -0.0156 | -0.0196 - 0.00872 |

| θHGB | 0.00404 | 0.00394 | 0.000461 - 0.00827 |

| IIVCL (CV%) | 27.6% | 26.3% | 18.1 - 35.3 |

| Proportional error | 0.527 | 0.521 | 0.455 - 0.592 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).